Abstract

The ideal treatment for patients who suffer from pilonidal sinus disease should lead to a cure with a rapid recovery period allowing a return to normal daily activities, with a low level of associated morbidity. A variety of different surgical techniques have been described for the primary treatment of pilonidal sinus disease and current practice remains variable and contentious. Whilst some management options have improved outcomes for some patients, the complications of surgery, particularly related to wound healing, often remain worse than the primary disease. This clinical review aims to provide an update on the management options to guide clinicians involved in the care of patients who suffer from sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease.

Keywords: pilonidal abscess, pilonidal sinus, pilonidal sinus excision, pilonidal sinus surgery, wound healing

1. INTRODUCTION

Pilonidal (pilus = hair, nidus = nest) sinus disease is common, affecting roughly 26 per 100 000 population.1 It is rarely seen before puberty or in later life and predominantly affects young males. It can cause pain, sepsis, and reduced quality of life and has an impact on the individual's ability to attend work or education. Risk factors for the condition include male gender, young age, obesity, Mediterranean ethnicity, hairiness, deep natal cleft, and poor hygiene.2, 3

The exact aetiology of pilonidal sinus disease is unclear; however, it is thought to be related to hormone changes leading to enlargement of hair follicles with resultant blockage in the pilosebaceous glands in the sacrococcygeal area. The movement of the buttock and the shape of the natal cleft facilitate the burial of the barbed shaped hairs into these sinuses, which in turn exacerbates the infection acting as a foreign body.

Pilonidal sinus disease can initially present as either an acute abscess or a discharging sinus. Regardless of the disease presentation, the ideal treatment for patients who suffer from pilonidal sinus disease should allow a cure with a rapid recovery period allowing return to normal daily activities, with a low level of associated morbidity. A variety of different surgical techniques have been described for the primary treatment of pilonidal sinus disease, and current practice remains variable and contentious. While some management options have improved for some patients, the complications of surgery may be worse than the primary disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Unhealed wound following midline primary closure

When assessing the outcomes of various pilonidal treatment, there are many factors to be considered:

Time to complete healing and frequency of unhealed wounds in clinical trials

Disease recurrence

Number of operations needed to achieve healing

Postoperative wound complications

Time to return to work/education

Few clinical studies, however, record all these parameters. Inadequate follow‐up duration for patients recruited into studies may also underreport the associated complications or recurrence.

This clinical review aims to provide an update on the management options to guide clinicians involved in the care of patients who suffer from sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease.

2. METHODS

As a result of the large scope of this non‐systematic review, the literature identified was intentionally specific. The following sources were searched, Ovid, Embase, and Medline using PubMed, using search terms “pilonidal sinus”, “pilonidal abscess”, and “wound healing”. We supplemented these sources with a hand search of selected articles. All articles reviewed were in English and peer‐reviewed with no limitation on date of publication. Outcomes recorded were wound‐healing rates/time to complete healing, recurrence rates, rate of postoperative wound complications, return to work/education, and postoperative pain scores as applicable.

3. ASYMPTOMATIC PITS TREATMENT

For patients with asymptomatic pits, a conservative approach may be reasonable. Low subsequent surgery rates have been reported in over 170 asymptomatic patients who were treated conservatively.4, 5, 6

4. ACUTE ABSCESS TREATMENT

Traditionally wide en‐bloc excision was advocated by some surgeons even for those patients who presented acutely with an abscess. However, disease recurrence rates following a first episode of incision and drainage are as low as 20% at 20 years follow‐up.7 Matter et al., found similar recurrence rates in patients with acute pilonidal abscess treated with simple incision and drainage vs wide excision, but the average time to return to work for the latter group was double (7 vs 14 days).8 Therefore, there is little justification for the performance of wide en‐bloc excision for acute abscess presentations as it would result in overtreatment for 80% of patients, with the associated morbidity and time off work, and therefore should be abandoned. Incision and drainage is recognised as the treatment of choice for acute pilonidal abscesses, and it can be performed safely under either local or general anaesthetic. Webb and Wysocki (2011) reviewed 243 patients who underwent incision and drainage for acute pilonidal abscess and compared outcomes between 134 patients who had off‐midline longitudinal incision with 74 patients who had a midline longitudinal incision, majority under general anaesthetic.9 There was a shorter time to healing in off‐midline drainage incision compared with midline drainage incision, of approximately 3 weeks (P = 0.02) However, this study did not capture those patients who had an abscess that drained spontaneously or who were drained outside of the surgical department.

5. CHRONIC DISEASE TREATMENTS

5.1. Laying open and curettage

Laying open of all the involved sinus tracts with curettage may be adequate to achieve cure of the disease. A meta‐analysis performed in 2015 included all studies (Randomised controlled trial (RCT), retrospective or prospective studies; n = 13) describing laying open (not excision) of sinus with curettage of the tract to treat pilonidal disease.10 A total of 13 studies with 1445 patients reported a pooled rate of 4.47% for disease recurrence (95% CI 0.029‐0.063), 1.44% for complications (95% CI 0.005‐0.028), 8.4 days to return to work (95% CI 5.23‐11.72), and time to healing of 21 to 72 days. The procedure was performed under local anaesthetic in 7 out of the 13 studies. When compared with wide en‐bloc excision, a further meta‐analysis found no significant differences in the rate of disease recurrence (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.17‐2.38; P = 0.856).11 There was no significant difference seen between the two groups; however, data were not able to be pooled for meta‐analysis. There was a significantly earlier return to work and lower postoperative pain scores with the laying open approach.

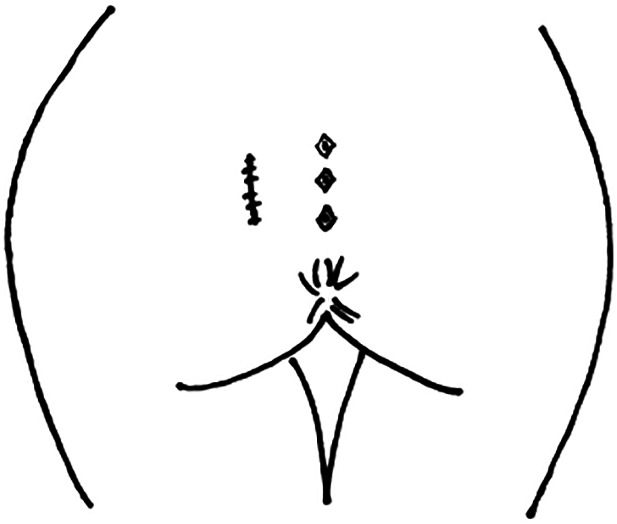

5.2. Pit picking techniques

Lord and Miller first described tiny “pit picking” excisions and cleaning of the sinuses in 1965, working on the theory that if the hair is removed and free drainage allowed then the sinus will heal.12 Bascom later described this procedure but with incorporation of a lateral abscess drainage incision (Figure 2).13 This technique can be performed in the day case setting often under the use of local anaesthetic. Senpati et al. (2000) reported that 99% of lateral Bascom wounds healed by 3 months in their case series of 218 patients.14 Overall, a 12% recurrence rate has been demonstrated in a systematic review of “pit‐picking procedures”.15 The mean time to wound healing was 4‐8 weeks with a low rate of wound complications (2‐8%). The reduced postoperative morbidity and ambulatory nature of the operation has made the Bascom's procedure favourable as a first line treatment with the accepted risk of a slightly higher disease recurrence rate.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of Bascom procedure. Pit‐picking excisions combined with a lateral abscess drainage incision

5.3. Wide en‐bloc excision with either primary midline closure or healing with secondary intention

The main stay of traditional chronic disease treatment involves the complete excision of midline skin pits and the associated sinus tracts via a wide en‐bloc excision. Debate still exists on the method of skin closure following this approach; primary midline closure vs closure via secondary intention healing. A meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials was published in 2008.16 The study included 7 trials that compared wound healing rates in open healing with primary midline closure. Results demonstrated a significant quicker time to wound healing in the primary midline closure compared with open healing in 4 of these 7 trials. The other 3 trials showed quicker healing in the primary closure group but did not report formal statistical tests. Because of inconsistencies in the reporting, data were unable to be pooled for meta‐analysis. Five trials assessed the rate of surgical site infection (SSI) when comparing open healing (n = 208) and primary midline closure (n = 207), overall rates were found to be low with no difference being found between the two groups (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.20‐3.09; P = 0.72). Disease recurrence rates at greater than 1‐year follow‐up was reported in 8 trials. Majority of these trials reported high rates of follow‐up (>80%). Open healing (n = 320) was found to have a lower risk of recurrence than primary closure (n = 353) (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.23‐0.66; P < 0.001). Patient who underwent open healing took longer to return to work compared with primary midline closure (mean difference of 8.56 days (range 2.97‐14.15) and did not have a significant difference in wound complication rates. In summary, wounds healed quicker when primary midline closure was performed but this came at the expense of higher rates of disease recurrence.

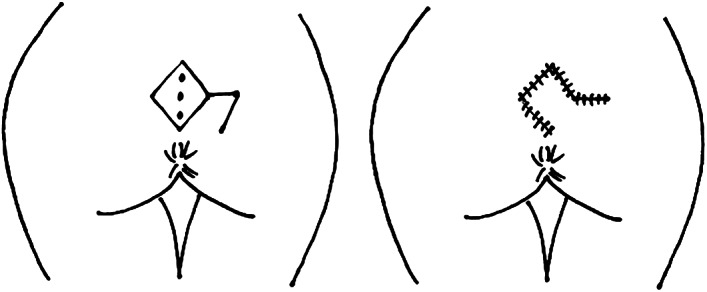

5.4. Off‐midline closure techniques: Rotational vs advancement flaps

The rhomboid transposition rotational flap involves a full‐thickness (extending down to presacral fascia) rhomboid‐shaped flap that is rotated into the defect. Limberg modified this approach by lateralising the distal portion of the suture line to prevent suture line breakdown17 (Figures 3 and 4). A meta‐analysis analysed the effect of primary closure vs rhomboid excision and Limberg flap.18 The study included 6 RCTs with a total of 641 patients. Limberg flap was found to be superior to primary closure for wound dehiscence; 0.9% in the Limberg flap group (3/331) vs 6.5% in the primary closure group (21/320) (RR 0.041, 95% CI −0.083‐0; P = 0.05). There was no difference seen in terms of disease recurrence; 0.79% in the Limberg flap group (2/254) vs 8.4% in the primary repair group (28/331) (P = 0.073). Five of the six studies reported on the incidence of SSIs, with a significantly lower incidence of SSI found in the Limberg flap group (4.5%, 14/307) compared with primary closure group (14.2%, 41/288) (P = 0.01).

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of rotational flap. A full‐thickness (extending down to presacral fascia) rhomboid‐shaped flap that is rotated into the remaining defect

Figure 4.

Healed rotational flap for chronic pilonidal sinus disease

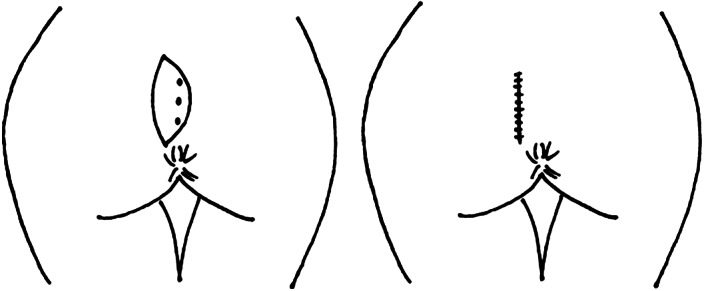

Karydakis first described the “advancement” flap in 1973; an elliptical asymmetrical wide excision of the skin, abscess, and sinus, then mobilisation of the skin edge closest to the midline to create a flap, which is secured deep at the underlying sacrococcygeal fascia and superficially at the other skin edge, thus flattening the natal cleft and avoidance of midline incisions (Figure 5).3 Karydakis reported on a total of 7471 patients, of whom 95% were followed up for 2 to 20 years.19 The majority of these patients healed with a mean time of return to work of 9 days and only 1% recurrence rate. A systematic review of publications of Karydakis operations showed a reported recurrence rate of 3.9% with complete wound healing occurring within 1 week in 60 to 70% of patients.15

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of advancement flap. An elliptical asymmetrical wide excision of the skin, abscess, and sinus, then mobilisation of the skin edge closest to the midline to create a flap, which is secured deep at the underlying sacrococcygeal fascia and superficially at the other skin edge, thus flattening the natal cleft and avoidance of midline incisions

A meta‐analysis compared midline primary closure with off‐midline primary closure or flap techniques in 10 RCTs (4 tension‐free midline/6 conventional midline vs 7 Limberg flap/2 Karydakis flap/1 V‐Y flap).11 Pooled data in relation to recurrence rate found a significantly higher recurrence rate after midline closure compared with off‐midline closure (RR 2.32, 95% CI 0.98‐5.45; P = 0.023). However, when analysed using only the tension‐free midline closure there was no significant difference seen (RR 3.30, 95% CI 0.34‐4.88; P = 0.162). SSI rates were found to be lower in the off‐midline group compared with both overall and tension‐free midline closure groups (RR 1.63, 95% CI 1.13‐2.36 and RR 2.08, 95% CI 0.95‐4.54). Significantly higher wound dehiscence rates were seen in the midline closure group (RR 1.63, 95% CI 1.13‐2.36), this effect remained when only analysing the tension‐free midline group.

The same meta‐analysis also compared off‐midline primary closure techniques; advancement flaps vs rotational flaps.11 There was a total of 951 patients across six RCTs (five of which included Karydakis flaps and one using a Bascom cleft lip flap in comparison to Limberg/modified Limberg flaps). No significant difference was seen between either group in terms of disease recurrence, SSI, or wound dehiscence rates. However, there was a shorter time to return to work seen with the Karydakis flap (Standardised mean difference −0.18, 95% CI −0.035 to −0.008). Karydakis and Limberg flaps again appeared to be comparable in a more recent meta‐analysis of 8 RCTs (6 single‐centre and 2 multi‐centre trials) that directly compared the two types of flap, including a total of 1121 patients (Karydakis n = 554 and Limberg n = 567).20 There was no significant difference between the two flaps in the primary outcome of the recurrence rate (OR 1.07, 95% CI 0.59‐1.92; P = 0.83), although follow‐up duration varied from 15.5 to 33.3 months. Secondary outcomes including wound dehiscence and SSI were similar in the two groups. Six trials included time off work, with two studies noting a significantly faster return to work in the Limberg flap group, although these data could not be pooled for meta‐analysis because of heterogeneity. Moreover, the authors highlighted a lower risk of seroma formation associated with the Limberg flap compared with Karydakis (OR 2.03, 95% CI 1.15‐3.59; P = 0.01), but evidence of better cosmesis and higher patient satisfaction rates with the advancement flap when compared with the rotational flap technique in two of the included studies. Although this meta‐analysis suggests the superiority of the Limberg flap in certain aspects (eg, risk of seroma formation), long‐term follow‐up data indicate lower recurrence rates with the Karydakis flap (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of recurrence rates (%) at 12, 24, and 60 months of follow‐up for different surgical and non‐surgical procedures from meta‐analysis by Stauffer et al. (2018)35

| Procedure | Number of patients | 12 months | 24 months | 60 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 89 583 | 2.0 | 4.4 | 10.8 |

| Excision with secondary intention healing | 10 166 | 1.5 | 4.2 | 13.1 |

| Excision with primary midline closure | 21 583 | 3.4 | 7 | 16.8 |

| Karydakis/Bascom cleft lift (advancement flaps) | 16 349 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.9 |

| Limberg flap (rotational flaps) | 12 384 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 5.2 |

| Pit picking | 6272 | 2.7 | 6.5 | 15.6 |

| Incision and drainage | 360 | 10.4 | 25.9 | 40.2 |

| Phenolisation | 1947 | 1.9 | 14.1 | 40.4 |

5.5. Minimally invasive surgical techniques

In the last 5 years, several groups have developed and evaluated endoscopic pilonidal sinus treatment (EPSiT). This technique, which was first presented by Minero et al. in a case series of 11 patients, involves the introduction of a fistuloscope into an enlarged pit (0.5 cm) to directly visualise all sinus tracts, remove hairs and debris, and ablate the cavity using monopolar electrocautery under direct vision, with or without the injection of a sclerosant.21 This minimally invasive technique, which can be performed under local anaesthetic, has been advocated, quoting, in common with other minimally invasive procedures, reduced pain and hospital stay, faster healing, and earlier return to work as clear advantages. In addition, EPSiT purportedly offers more accurate identification of all sinus cavities and lateral tracts via direct visualisation allowing removal of all hairs and infected debris, with the hypothetical advantage of reduced SSI and recurrence rates.22

A systematic review and meta‐analysis of nine studies investigating the outcomes of EPSiT was recently published.23 Nine studies were included in this review (2 retrospective studies, 6 prospective studies, and 1 RCT), representing a total of 497 patients (mean age 24.8, range 23‐27.6), all of whom underwent a daycase procedure. The mean time to complete healing was 32.9 days (range 16‐75 days) and time to return to work was 2.9 days (range 1.6‐6 days). Recurrence was observed in 20 patients (4.02%) after complete healing, with a median follow‐up of 12 months (range 2.5‐25 months). Complications of this procedure include SSI, haematoma, persistent discharge, and failure of healing and were reported in 8 (1.6%) patients, with a mean‐weighted complication rate of 1.1% across the nine studies. The weighted failure rate (recurrence/non‐healing) across the nine studies was 6.3%, which compares favourably with the recurrence rate after excision with primary closure (8%). However, flap procedures, off‐midline closure techniques, and excision and curettage have all been associated with lower recurrence rates in the published literature, albeit with an associated higher complication rates than EPSiT. Interestingly, one study reported that the use of this technique in acute pilonidal abscess was associated with less pain, faster healing and return to work, compared with conventional incision and drainage, with a comparable rate for the need of further definitive surgery.24

In summary, in the era of minimally invasive surgery, EPSiT appears to be a safe and promising technique for the treatment of pilonidal sinus disease, with multiple authors emphasising its particular role in the paediatric population.25, 26 However, this technique has yet to be standardised and its cost‐effectiveness, long‐term outcomes, and applicability to recurrent disease, as well as its comparative efficacy and safety against current surgical options need further evaluation.

5.6. Phenolisation of pit tracts

Phenol has sclerosant properties destroying epithelium and debris within the sinus and promoting sinus healing and was first described in 1964 in an ambulatory setting under local anaesthetic.27, 28 A systematic review of observational studies reported a mean recurrence rate of 12.6% at 2‐years follow‐up, a SSI rate of 8.7%, and a mean return to work of 2.3 days.29 A Dutch single‐centre randomised controlled trial investigating the role of surgical pit excision and phenolisation of the sinus tract vs radical surgical excision, is currently ongoing.30 The primary endpoint is loss of days of normal activity/working days. Secondary endpoints are the anatomic recurrence rate, symptomatic recurrence rate, quality of life, SSI, time to wound closure, symptoms related to treatment, pain, usage of pain medication, and total treatment time. Phenol injection under local anaesthetic was compared with excision with healing by secondary intention under a spinal anaesthetic in a recent RCT of 140 patients.31 Complete wound healing was significantly improved in the phenol group (16.2 vs 40.1 days, P < 0.001), and phenol treatment offered significantly shorter times to pain‐free mobilisation (0.8 vs 9.3 hours) and defaecation (16.2 vs 22.5 hours). The risk of recurrence was not significantly different (P = 0.92) between the phenol group (18.6%) and the excision group (12.9%) after an average follow‐up period of 39.2 months, although 11.4% of the patients in the phenol group required a second application. A similar randomised controlled trial compared excision and primary closure under spinal anaesthetic to non‐operative therapy in the outpatient setting with a mixture of sclerosant (tetracycline) and a herbal product with antimicrobial properties (Lawsonia inermis, better known as henna) for the treatment of chronic pilonidal sinus disease in 400 patients, with an average follow‐up of 2 years (range, 6 months‐5 years).32 Patients in the non‐operative group did not require time off work/education had a reduced risk of wound infection (0.5% vs 4%; P = 0.01) and reduced use of antibiotics, and the cost of treatment was significantly cheaper (30$ vs 500$; P < 0.001), which may be a particularly relevant factor for developing countries. However, the risk of recurrence in the non‐operative group was significantly higher after one application when compared with surgical excision (11% vs 6%; P = 0.051), but this was reduced to 1% after a second application, making this a potentially viable cost‐effective strategy. It should be noted that phenol should be avoided in patients with nut allergy or with previous known reactions to phenol usage.

5.7. Fibrin glue

Fibrin glue as a treatment for pilonidal sinus disease has been reported as an alternative to conventional surgery. In a clinical service evaluation, 75% of patients (45/57) were satisfied with their treatment and 45% (31/57) had returned to normal activities within a week.33 74% required no further treatment; of those that did have further treatment, 3 out of 15 had repeat glue treatment that resulted in complete healing. A Cochrane review performed in 2017 included 4 RCTs with the intervention of fibrin glue as monotherapy or as a surgical adjunct in a total of 253 patients.34 When fibrin glue was used as a monotherapy compared with Bascom's procedure there was low‐quality evidence to support less pain on day one after the procedure and shorter time to return to normal activities, no data were available on time to healing or adverse events. Fibrin glue as an adjunct to the Limberg flap may reduce healing time, postoperative pain, and time to return to normal activities but with a possible incidence of postoperative seroma. Fibrin glue as an adjunct to Karydakis flap did not report on time to healing but may reduce the length of stay. The authors concluded that the evidence is uncertain and the 4 RCTs identified had small numbers and were at risk of bias resulting in low‐quality evidence for outcomes of time to healing and adverse events. Future well‐conducted studies may be warranted to further assess the role of fibrin glue. It should be noted that fibrin glue should be avoided in patients with known adverse reaction to bovine albumin.

5.8. Long‐term follow‐up and recurrence rates

A comprehensive study on recurrence rates following various surgical treatments of pilonidal sinus disease was recently published, including over 80 000 patients studied over the past 180 years.35 This extensive report not only offers evidence to inform current surgical practice, but also provide remarkable insight for the design of future studies emphasising the importance of adequate follow‐up if accurate conclusions about recurrence rates following specific procedures are to be drawn.

Firstly, regarding current practice, the advancement flap procedures were associated with the lowest recurrence rates at any follow‐up time (0.2% at 12 months to 1.9% at 60 months), followed by rotational flaps (Table 1). Moreover, 40% of patients who underwent incision and drainage for acute abscess had a recurrence within 5 years, highlighting the need for further drainage and/or definitive therapy in a significant proportion of patients. Excision with primary midline closure carried the highest long‐term recurrence rates in this study (67.9% at 240 months), which motivated the authors to recommend abandoning this technique in favour of off‐midline closure or flap techniques.

Secondly, regarding future research, the authors emphasised the importance of studying recurrence rates as a function of follow‐up times. The mean recurrence at 1‐ and 5‐year follow‐up differed by a factor of 5 when all procedures were included in the analysis. For individual procedures (eg, excision and primary closure, rotational flap), the 1 and 5‐year recurrence rates varied by a factor of 3 to 20. This means that previous studies with inadequate follow‐up times may have reported grossly underestimated recurrence rates, and any future study should take this limitation into account. In other words, quoting recurrence rate in the absence of comparable follow‐up durations may bias recurrence figures by a factor of 20. Therefore, the authors recommended long‐term follow‐up (ie, 5–10 years), if reliable conclusions about recurrence rates are to be drawn from future studies.

It is worth noting that despite its comprehensive nature with regard to long‐term recurrence rates, this study did not take into account other factors such as time to complete healing, time off work, length of hospital stay, complications, and cost.

6. ADJUNCTS TO SURGERY

6.1. Antimicrobials

It has long been recognised that problems with delayed wound healing postexcisional pilonidal surgery may be because of infection, particularly by anaerobic bacteria.36 It is often necessary to reshape the wound to allow adequate drainage and to treat with antimicrobials. However, the use and regimens of antimicrobials after pilonidal disease surgery remain contentious. A systematic review examined the use of antimicrobials with pilonidal surgery.37 Seven studies examined the use of antimicrobial perioperatively and postoperatively in 690 patients undergoing excision and primary closure. Three of these studies compared the administration of antimicrobial prophylaxis vs no prophylaxis, and found no difference in the development of SSI, primary healing, or recurrence rates. Single dose vs a 4 to 5‐day course of prophylaxis was compared in 2 RCTs, they found no difference in the primary healing or recurrence rate but there was a decreased rate of SSI at both 2 and 4 weeks with the long course of antimicrobials seen in the one RCT and with no difference seen in the other. Two further cohort studies included showed no difference in SSI rates observed. Clinical heterogeneity precluded a formal meta‐analysis of the data, and a variety of different antimicrobial regimens were used. Although antimicrobial prophylaxis was not associated with improved rates of SSI and wound healing in excision with primary closure in the aforementioned systematic review, this lack of benefit may not apply to flap reconstruction. In a randomised parallel‐arm double‐blinded trial comparing antimicrobial prophylaxis vs no prophylaxis in patients undergoing Karydakis flap reconstruction, the no prophylaxis arm was terminated prematurely because of a significantly higher rate of infectious complications.38 In addition, this trial demonstrated no significant benefit from the use of triclosan‐coated sutures. To date, there has been little level 1 evidence to recommend antimicrobial prophylaxis for pilonidal excision with primary closure, although this may not be applicable to flap reconstruction techniques. There is certainly a need for well‐designed trials to be conducted in this area to determine optimum antimicrobial prophylaxis and the need and duration of any postoperative antimicrobial treatment course.

6.2. Dressings

Topical application of antimicrobials has been advocated for pilonidal sinus disease as local administration can lead to prolonged and higher therapeutic concentrations when compared with systemic antimicrobials. A systemic review evaluated the usage of gentamicin‐impregnated collagen sponge and included five RCTs and 1 retrospective case–control study.39 Four of these studies compared primary closure with gentamicin collagen sponge vs primary closure without gentamicin collagen sponge, and found no difference between wound healing and recurrence rate, but with a trend towards significance in a reduction in SSI rates with the gentamicin sponge (absolute risk reduction 20%, 95% CI 1%–41%; P = 0.06). Two further included studies compared primary closure with gentamicin collagen sponge vs secondary wound healing without gentamicin collagen sponge, they reported a shorter healing time with the gentamicin sponge group. However, it was unclear how much of the effect was because of the gentamicin sponge or simply because of primary vs open healing techniques.

Hydrocolloid dressings have been documented to have advantages for wound healing, with the creation of a humid environment that promotes angiogenesis and fibrinolysis, which is thought to contribute to healing, prevention of infection, and reduction of pain.40 The use of hydrocolloid dressings has also been examined in an RCT in patients undergoing pilonidal sinus excision and secondary intention healing.41 The study compared the use of conventional gauze dressings (n = 15), with Comfeel (Coloplast, Humlebaek, Denmark) (n = 12) and Varihesive (Convatec Group PLC, Reading, Berkshire, UK) (n = 11). No difference was demonstrated between either the conventional gauze group or either hydrocolloid dressing groups in terms of wound healing rates or recurrence rates at 74 months' follow‐up. The hydrocolloid dressing was associated with less pain in the first four postoperative weeks compared with the control group (P = 0.05). There was also a decrease in the number of postoperative cultures that grew pathogens in the hydrocolloid group (1 vs 5; P = 0.03), with all wound having no cultured pathogens at the time of operation. However, the study had a small sample size and the results should be taken with caution.

6.3. Negative pressure wound therapy

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) consists of an open cell foam dressing covered in adhesive dressing and attached to a vacuum pump to create a sub atmospheric pressure, therefore draining away wound exudate and thus promoting wound healing. A randomised controlled trial compared the use of NPWT (applied intraoperatively till 2 weeks postoperatively) with standard wound care after excisional midline surgery in a total of 49 patients.42 There was no difference demonstrated in time to complete wound healing, recurrence of the disease or wound infection rates. However, it should be noted that the sample size was small and that the duration of NPWT application of only 2 weeks might be too short to see an adequate effect. In clinical practice, however, because of the pilonidal wound location it can often be difficult to achieve an adequate seal for NPWT.

6.4. Platelet‐rich plasma

Platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) is a product described to attempt to accelerate wound healing because of the release of several angiogenic factors upon degradation (vascular endothelial growth factor, insulin‐like growth factor, platelet‐derived angiogenesis factor, and platelet‐derived growth factor). Its use as an adjunct in the treatment of pilonidal sinus disease has been evaluated in a meta‐analysis in 2017, which included 4 RCTs in surgery with secondary intention healing comparing PRP with the control group (classic dressings).43 The healing time was found to be significantly shorter in the intervention group (Pooled effect size 0.642, 95% CI 0.485‐0.798; P < 0.001), with a mean time to healing of 27.1 days in the PRP group compared with 43.0 days in the control group. The pooled effect size for time to return to work was 0.703 (95% CI 0.539‐0.867), with a difference of 9.83 days shorter in the PRP group. The study did not examine disease recurrence or SSI rates and the cost effectiveness of PRP has not been analysed to date in the setting of pilonidal disease. It should be noted that PRP should not be offered to patients with cancer, active infection, thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction syndromes, and pregnancy or breastfeeding.

6.5. Hair removal

The removal of body hair has been suggested to prevent recurrence after surgery for pilonidal sinus disease.44 A recent systematic review included studies that compared patients who had laser hair removal (n = 378), patients who had razor shaving/ cream depilation (n = 154), and those patients without hair removal (n = 431). The disease recurrence rate was reported to be 9.3% (34/366) in patients who had laser hair removal, 23.4% (36/154) in those patients who had razor shaving/cream depilation and 19.7% (85/431) in those without hair removal. Whilst this systematic review showed a lower rate of recurrence with laser hair removal, compared with razor shaving/cream depilation or no hair removal, these results should be taken with caution as a variety of surgical techniques were used or often not described, and, therefore, other factors may be responsible for the differences seen. It should also be noted that the recurrence rates are far higher than those noted in other studies where hair removal is not specified and the studies included were noted to have small sample sizes and limited methodological quality.

7. CONCLUSIONS

A conservative approach may be suitable for those patients with asymptomatic pits. Incision and drainage should be the treatment of choice for acute pilonidal abscess, using an off‐midline incision. Non‐surgical treatments such as phenolisation or fibrin glue may be of value for chronic sinus disease, but as of yet, there are still some concern about the long‐term outcomes. Minimally invasive approaches such as laying open of tracts and curettage or “pit‐picking” approaches may be beneficial in the first line treatment of chronic pilonidal sinus weighing the risk of recurrence (in the region of 12%) against the benefit of minimal access surgery, as well as being more acceptable in terms of cosmetic outcome. There is compelling evidence to move away from midline closure to benefit patients undergoing excisional surgery to improve wound‐healing rates and recurrence. Surgical adjuncts such as antimicrobials, dressings, NPWT, PRP, and hair removal have yet to demonstrate improvements in outcomes. However, many of the studies related to various management options for pilonidal sinus disease are found to be underpowered and of limited methodological robustness. There is a need for well‐conducted RCTs to further assess many of these treatments suggested for pilonidal sinus disease.

What is apparent in the treatment of pilonidal disease is the huge variation in the range of both treatment options and outcomes for patients. Management of these patients should, therefore, be from dedicated surgeons with interest in pilonidal disease to reduce variation in outcomes and prevent misery for otherwise fit healthy people.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Harries RL, Alqallaf A, Torkington J, Harding KG. Management of sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease. Int Wound J. 2019;16:370–378. 10.1111/iwj.13042

REFERENCES

- 1. Brown HW, Wexner SD, Segall MM, Brezoczky KL, Lukacz ES. Accidental bowel leakage in the mature women's health study: prevalence and predictors. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:1101‐1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clothier PR, Haywood IR. The natural history of the post anal (pilonidal) sinus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1984;66(3):201‐203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Karydakis GE. New approach to the problem of pilonidal sinus. Lancet. 1973;2(7843):1414‐1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Armstrong JH, Barcia PJ. Pilonidal sinus disease. The conservative approach. Arch Surg. 1994;129:914‐918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Raffman RA. A re‐evaluation of the pathogenesis of pilonidal sinus. Ann Surg. 1959;150:895‐903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hardaway RM. Pilonidal cyst, neither pilonidal nor cyst. AMA Arch Surg. 1958;76:143‐147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Doll D, Matevossian E, Hoenemann C, Hoffmann S. Incision and drainage preceding definite surgery achieves lower 20‐year long‐term recurrence rate in 583 primary pilonidal sinus surgery patients. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11(1):60‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matter I, Kunin J, Schein M, Eldar S. Total excision versus non‐resectional methods in the treatment of acute and chronic pilonidal disease. Br J Surg. 1995;82(6):752‐753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Webb PM, Wysocki AP. Does pilonidal abscess heal quicker with off‐midline incision and drainage? Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15:179‐183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garg P, Menon GR, Gupta V. Laying open (deroofing) and curettage of sinus as treatment of pilonidal disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. ANZ J Surg. 2016;86:27‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Enriquez‐Navascues MJ, Emparanza JI, Alkorta M, Placer C. Meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing different techniques with primary closure for chronic pilonidal sinus. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:863‐872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lord PH, Millar DM. Pilonidal sinus: a simple treatment. Br J Surg. 1965;52:298‐300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bascom J. Pilonidal disease: origin from follicles of hairs and results of follicle removal as treatment. Surgery. 1980;87:567‐572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Senapati A, Cripps NP, Thompson MR. Bascom's operation in the day‐surgical management of symptomatic pilonidal sinus. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1067‐1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thompson MR, Senapati A, Kitchen P. Simple day‐case surgery for pilonidal sinus disease. Br J Surg. 2011;98:198‐209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McCallum IJ, King PM, Bruce J. Healing by primary closure versus open healing after surgery for pilonidal sinus: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br Med J. 2008;336(7649):868‐871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee PJ, Raniga S, Biyani DK, Watson AJ, Faragher IG, Frizelle FA. Sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10(7):639‐650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Horwood J, Hanratty D, Chandran P, Billings P. Primary closure or rhomboid excision and Limberg flap for the management of primary sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. A meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(2):143‐151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Karydakis GE. Easy and successful treatment of pilonidal sinus after explanation of its causative process. Aust N Z J Surg. 1992;62:385‐389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Prassas D, Rolfs TM, Schumacher FJ, Krieg A. Karydakis flap reconstruction versus Limberg flap transposition for pilonidal sinus disease: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Langerbecks Arch Surg. 2018;403:547‐554. 10.1007/s00423-018-1697-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Meinero P, Mori L, Gasloli G. Endoscopic pilonidal sinus treatment (E.P.Si.T.). Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18(4):389‐392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Milone M, Fernandez LM, Musella M, Milone F. Safety and efficacy of minimally invasive video‐assisted ablation of pilonidal sinus: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(6):547‐553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Emile SH, Elfeki H, Shalaby M, et al. Endoscopic pilonidal sinus treatment: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(9):3754‐3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gecim IE, Goktug UU, Celasin H. Endoscopic pilonidal sinus treatment combined with crystalized phenol application may prevent recurrence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(4):405‐407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pini Prato A, Mazzola C, Mattioli G, et al. Preliminary report on endoscopic pilonidal sinus treatment in children: results of a multicentric series. Pediatr Surg Int. 2018;34(6):687‐692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Esposito C, Izzo S, Turrà F, et al. Pediatric endoscopic pilonidal sinus treatment, a revolutionary technique to adopt in children with pilonidal sinus fistulas: our preliminary experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2018;28(3):359‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dag A, Colak T, Turkmenoglu O, Sozutek A, Gundogdu R. Phenol procedure for pilonidal sinus disease and risk factors for treatment failure. Surgery. 2012;151:113‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maurice BA, Greenwood RK. A conservative treatment of pilonidal sinus. Br J Surg. 1964;51:510‐512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kayaalp C, Aydin C. Review of phenol treatment in sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:189‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Furnée EJB, Davids PHP, Pronk A, Smakman N. Pit excision with phenolisation of the sinus tract versus radical excision in sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease: study protocol for a single Centre randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Calikoglu I, Gulpinar K, Oztuna D, et al. Phenol injection versus excision with open healing in pilonidal disease: a prospective randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(2):161‐169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Salih RQ, et al. Nonoperative management of pilonidal sinus disease: one more step toward the ideal management therapy—a randomized controlled trial. Surgery. 2018;S0039‐6060(17):30886‐30883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Elsey E, Lund JN. Fibrin glue in the treatment for pilonidal sinus: high patient satisfaction and rapid return to normal activities. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17(1):101‐104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lund J, Tou S, Doleman B, Williams JP. Fibrin glue for pilonidal sinus disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1:CD011923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stauffer VK, Luedi MM, Kauf P, et al. Common surgical procedures in pilonidal sinus disease: a meta‐analysis, merged data analysis, and comprehensive study on recurrence. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marks J, Harding KG, Hughes LE, Ribeiro CD. Pilonidal sinus excision‐‐healing by open granulation. Br J Surg. 1985;72(8):637‐640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mavros MN, Mitsikostas PK, Alexiou VG, Peppas G, Falagas ME. Antimicrobials as an adjunct to pilonidal disease surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32(7):851‐858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Karip AB, Çelik K, Aydın T, et al. Effect of triclosan‐coated suture and antibiotic prophylaxis on infection and recurrence after Karydakis flap repair for pilonidal disease: a randomized parallel‐arm double‐blinded clinical trial. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2016;17(5):583‐588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nguyen AL, Pronk AA, Furnée EJ, Pronk A, Davids PH, Smakman N. Local administration of gentamicin collagen sponge in surgical excision of sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of the literature. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(2):91‐100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Field CK, Kerstein MD. Overview of wound healing in a moist environment. Am J Surg. 1994;167(1A):2S‐6S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Viciano V, Castera JE, Medrano J, et al. Effect of hydrocolloid dressings on healing by second intention after excision of pilonidal sinus. Eur J Surg. 2000;166(3):229‐232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Biter LU, Beck GM, Mannaerts GH, Stok MM, van der Ham AC, Grotenhuis BA. The use of negative‐pressure wound therapy in pilonidal sinus disease: a randomized controlled trial comparing negative‐pressure wound therapy versus standard open wound care after surgical excision. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(12):1406‐1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mostafaei S, Norooznezhad F, Mohammadi S, Norooznezhad AH. Effectiveness of platelet‐rich plasma therapy in wound healing of pilonidal sinus surgery: a comprehensive systematic review and meta‐analysis. Wound Rep Regen. 2017;25(6):1002‐1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pronk AA, Eppink L, Smakman N, Furnee EJB. The effect of hair removal after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease: a systematic review of the literature. Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22(1):7‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]