Abstract

There is a growing evidence that Fyn kinase is upregulated in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), where it plays a key role in tumor proliferation and invasion. In the present study, the antitumor effects of rosmarinic acid (RA), a Fyn inhibitor, were explored in human-derived U251 and U343 glioma cell lines. These cells were treated with various concentrations of RA to determine its effects on proliferation, migration, invasion, apoptosis, and gene and protein expression levels. The CCK-8 assay revealed that RA significantly suppressed cell viability of U251 and U343 cells. Furthermore, RA significantly reduced proliferation rates, inhibited migration and invasion, and decreased the expression levels of invasion-related factors, such as matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9. TUNEL staining revealed that RA resulted in a dose-dependent increase of U251 and U343 cell apoptosis. In line with this finding, the expression of apoptosis suppressor protein Bcl-2 was downregulated and that of the pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and cleaved caspase-3 was increased. In addition, it was revealed that the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway was involved in RA-induced cytotoxicity in U251 and U343 cells. Collectively, the present study suggested RA as a drug candidate for the treatment of GBM.

Keywords: apoptosis, Fyn, glioma, invasion, PI3K/Akt, proliferation, rosmarinic acid

Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most malignant primary brain tumor in humans and the most lethal cancer of the central nervous system, with an annual incidence of 3.19 cases per 100,000 persons (1-3). Despite significant advances in tumor resection, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, the prognosis of GBM remains poor. Treatment failure and continued disease progression results in a median overall survival of approximately 12-15 months, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 10% (4). Studies have revealed that the rapid proliferation and high invasiveness of GBM cells lead to treatment failure and tumor recurrence (5,6). Therefore, it is urgent to develop an effective treatment for GBM.

Src-family kinases (SFKs) are non-receptor tyrosine kinases. The family of proteins contains nine members (Fyn, c-Src, Yes, Lyn, Lck, Blk, Hck, Fgr and Yrk), five of which (Fyn, c-Src, Yes, Lyn and Lck) are expressed in human gliomas (7-10). SFKs are frequently overexpressed and/or activated in numerous human cancers (11-13), where they play a role in tumor invasion, proliferation, metastasis, survival, and angiogenesis (14). By knocking down individual SFKs in cultured cells (LN229, SF767, and GBM8), Lewis-Tuffin et al (7) determined that reduced c-Src, Fyn, and Yes expression also reduced growth and migration and altered motility-related protein phosphorylation patterns, while reduced Lyn expression had little effect on growth and migration. Other in vitro studies have revealed that Fyn knockdown is associated with decreased glioma cell proliferation and migration (15,16). Fyn tyrosine kinase, a downstream target of the oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinase pathway, is rarely mutated, yet significantly overexpressed, in human GBM (17,18). The mechanisms of Fyn tyrosine kinase overexpression in human glioma cells are poorly known yet they are important since small-molecule inhibitors of Fyn may be therapeutic options for glioma.

Rosmarinic acid (RA) is a natural phenolic compound that acts as a Fyn inhibitor by homology modeling of the human Fyn structure (19). RA can be found in species of the Boraginaceae and Lamiaceae families, mainly in the leaves of Rosmarinus officinalis, from which it can be easily isolated; it can also be found in peppermint, lemon balm, oregano, sage, and thyme (20,21). The molecular structure of RA (chemical formula: C18H16O8) contains two benzene rings located at the extremities of the molecule and a pair of ortho-hydroxyl groups in each benzene ring (Fig. 1). It has been reported that RA exerts a variety of beneficial biological properties, mainly antioxidant (22), anti-inflammatory (23), pro-apoptotic (24), and neuroprotective (25) effects. Furthermore, recent studies have revealed that RA has antineoplastic activity in leukemia, hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and small-cell carcinoma of the lung (26-29). However, the effects of RA on tumor biological characteristics, such as proliferation, migration, and invasion of human glioma cells and their mechanisms, have not been clearly reported.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of rosmarinic acid.

The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway is an important pathway in the regulation of tumorigenesis, and is significantly activated in glioma (30). The activation of PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling cascades is inhibited by Fyn knockdown in primary astrocytes (31). Therefore, it was hypothesized that RA may have an anti-glioma effect by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway.

In the present study, the effects of RA on glioma growth, migration, invasion, and apoptosis in vitro were explored, and the findings suggest that RA may be a potential therapeutic agent for glioma.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

RA was purchased from Aladdin (cat. no. R109804). LY294002 and 740 Y-P were purchased from MedChemExpress (cat. nos. HY-10108 and HY-P0175, respectively). The following primary antibodies were used: Fyn (product code ab125016; 1:2,000) was purchased from Abcam, PI3K (product no. 4249S; 1:1,000), MMP-2 (product no. 87809S; 1:1,000), MMP-9 (product no. 13667S; 1:1,000), Bcl-2 (product no. 3498S; 1:1,000), Bax (product no. 2772S; 1:1,000), cleaved caspase-3 (product no. 9661S; 1:1,000), fibrillarin (product no. 2639S; 1:1,000), and caspase-3 (product no. 9662S; 1:1,000), were all from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., and phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt) (cat. no. sc-514032; 1:500), Akt (cat. no. sc-81434; 1:1,000), NF-κB p65 (cat. no. sc-8008; 1:1,000), β-actin (cat. no. sc-47778; 1:2,000), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (cat. no. sc-47724; 1:2,000) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.

Cell culture

Human-derived glioma cell lines (U251 and U343) and the normal human astrocyte (NHA) cell line were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). All cells were maintained under 5% CO2 at 37°C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (cat. no. 11995040) containing 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin (cat. no. 15070063), and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (cat. no. 10100147; all from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in water-jacketed humidity-controlled incubators.

Cell viability

Cell proliferation was calculated using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc.) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well microplates at 2×103 cells/well and medium containing various concentrations of RA (0, 100, 200 and 400 µM) were added to the wells. After incubation for 24 or 48 h, the medium was replaced with 10 µl CCK-8 solution. After further incubation for 1 h at 37°C, the absorbance of each well was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Multiskan Go 1510; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). In addition, cell viability assessed by CCK-8 assay, was also performed on cells that were treated with or without RA (200 µM) for 24 h after PI3K agonist (740 Y-P, 25 µg/ml) or inhibitor (LY294002, 30 µM) pretreatment for 2 h.

Immunofluorescence

U251 and U343 cells were seeded on a cover slide in a 24-well plate at a density of 5×104 cells/well and maintained in a CO2 incubator for overnight growth. Then, the cells were treated with RA (0, 100, 200 and 400 µM) or vehicle for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were washed three times with PBS and blocked for 1 h in PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 and 10% skimmed milk powder at 37°C. Immunodetection was performed by incubation with a Fyn-specific antibody at 37°C for 1 h, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C. After washing three times in PBS, the cover slides were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with an anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cells were then washed three times with PBS and mounted using ProLong™ Gold antifade reagent (P36930; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Stained cells were analyzed at a magnification of ×200 using a confocal microscope (LSM 800; Zeiss AG).

Wound healing assay

Cell migration was evaluated using the wound healing assay as previously described (32). Briefly, U251 and U343 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 5×104 cells/well and allowed to adhere. Then, a wound/scratch was produced using a 200-µl pipette tip. After washing off the separated cells with phosphate-buffered solution (PBS), serum-free medium containing various concentrations of RA (0, 100, 200, and 400 µM) was added to the wells. The wound was observed at regular intervals between 0 and 48 h. Randomly selected areas were photographed at a magnification of ×100 using a phase-contrast microscope (CKX41; Olympus Corporation) and the wound area was calculated by ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National Institutes of Health).

Invasion assay

The invasion assay was conducted using Corning® BioCoat™ Matrigel® Invasion Chambers (product no. 354480; Corning, Inc.) with 8-µm pore chambers inserted into 24-well plates. U251 and U343 cells (5×104 cells) were cultured in 500 µl of serum-free DMEM with RA in the inserts and 500 µl of DMEM containing 15% FBS in the bottom of the wells. After 24 h of incubation, the inserts were washed three times with PBS and the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min. After washing with PBS, the cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet at room temperature for 15 min. Following another wash with PBS, the inner sides of the chamber were wiped with a cotton swab and images of the cells that invaded through the Matrigel® were obtained using a phase-contrast microscope (magnification, ×200). Finally, the number of invading cells was counted.

TUNEL and DAPI staining

U251 and U343 cells were seeded on a cover slide in a 24-well plate at a density of 3×104 cells/well and maintained in a CO2 incubator for overnight growth. Cells were treated with various concentrations of RA (0, 100, 200, and 400 µM) or vehicle for 24 h. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (product no. C1086; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Briefly, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min, incubated for 5 min with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS, and then incubated with a reaction mixture containing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and fluorescent labeling solution for 60 min at 37°C according to the manufacturer's protocol. The cells were then stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 5 min at 37°C and mounted using ProLong™ Gold antifade reagent. Stained cells were analyzed using a confocal microscope (magnification, ×200).

Flow cytometry

Cell apoptosis was detected using an Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit (product no. C1062L; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, cells were treated with RA (0, 100, 200 and 400 µM) for 24 h and then resuspended in binding buffer containing Annexin V and PI. After incubation at 25°C in the dark for 15 min, apoptotic cells were evaluated immediately using a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo v10.0.7 software (Tree Star, Inc.).

Western blot analysis

The cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (cat. no. 89901; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with complete protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics). Lysate protein concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). For some experiments, Nuclear Protein Extraction kit (product no. P0027; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was used to isolate the nuclear proteins in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Proteins (20 µg) from each sample was separated by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (EMD Millipore). After blocking with 5% w/v non-fat milk in TBST for 1 h at room temperature, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies. Then, the membranes were washed with TBST and horseradish peroxidase-linked IgG secondary antibodies (anti-mouse; product no. 7076; 1:4,000; and anti-rabbit; product no. 7074; 1:4,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) were added for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were visualized with Western Bright™ reagent (cat. no. K-12043-D10; Advansta, Inc.). The band signals were captured by The ChemiDoc MP system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National Institutes of Health) was used for densitometric analysis. The experiments were repeated at least three times independently.

Statistical analyses

The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three independent experiments, and statistical differences of cell viability were determined using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test; other comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett's multiple comparison test. All statistical analyses were computed by SPSS statistical analysis software version 22.0 (IBM Corp.). Values of P<0.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant differences.

Results

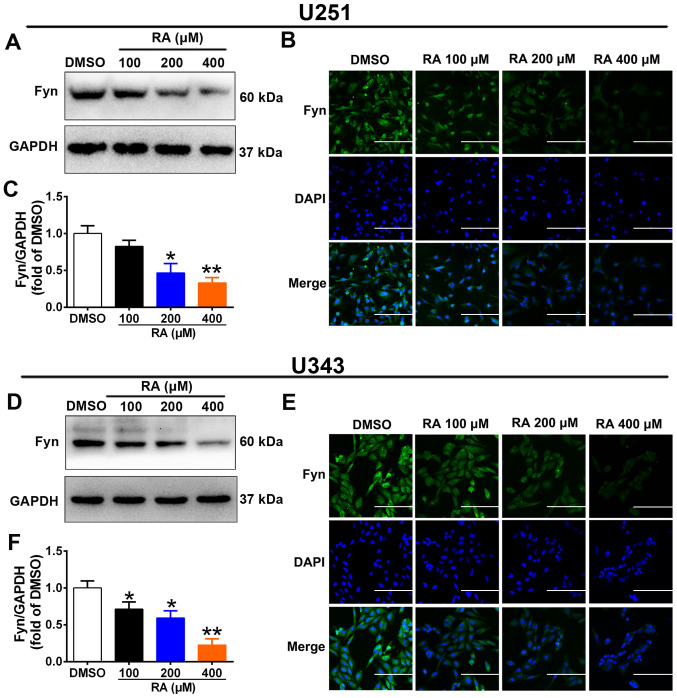

RA inhibits Fyn expression in vitro

First, the effect of RA on the expression of Fyn was examined in glioma cell lines (Fig. 2). RA treatment reduced Fyn expression in U251 and U343 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A, C, D and F). Immunofluorescence staining confirmed that RA inhibited Fyn expression in U251 and U343 cells (Fig. 2B and E).

Figure 2.

RA inhibits Fyn expression in glioma cells. (A and D) Western botting revealed that RA treatment suppressed the expression level of Fyn in a dose-dependent manner in U251 and U343 cells. (B and E) Representative areas of Fyn-positive immunofluorescent staining in U251 and U343 cells. Scale bar, 100 µm. (C and F) Densitometric quantification of the bands in A and D. GAPDH was used as a loading control. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. the DMSO group. RA, rosmarinic acid.

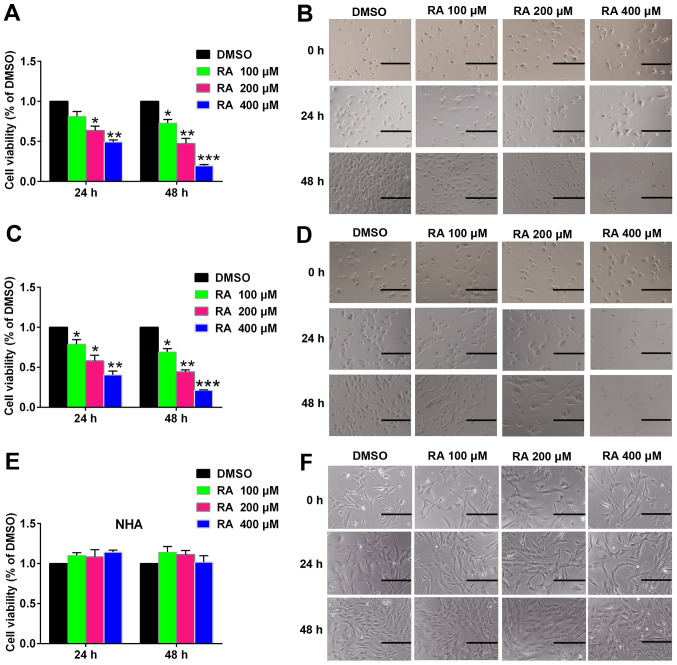

RA inhibits glioma cell proliferation

Next, the effect of RA on glioma cell proliferation was examined using the CCK-8 assay (Fig. 3). RA treatment inhibited cell proliferation in a time- and dose-dependent manner in U251 and U343 cells (Fig. 3A and C). RA-induced cytotoxicity was also observed under a microscope (Fig. 3B and D). The images revealed that as the concentration of RA increased, the density of glioma cells decreased, and more cells shrank and died. These observations were in line with the results of the CCK-8 assay.

Figure 3.

RA inhibits glioma cell growth. (A and C) U251 and U343 cells were treated with the indicated doses of RA for 24 and 48 h, viability was determined using the CCK-8 assay, and data in control cells were normalized to 100%. Data are presented as the means ± SD of three experiments. (B and D) The morphological changes of U251 and U343 cells. U251 and U343 cells were treated with various doses of RA for 24 and 48 h and observed using inverted phase-contrast microscopy. Scale bar, 100 µm. (E) The viability of NHA was determined after treatment with the indicated doses of RA for 24 and 48 h. (F) Cell morphology of NHA after treatment with the indicated doses of RA for 24 and 48 h. Scale bar, 100 µm. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. the DMSO group. RA, rosmarinic acid.

As a control, the effect of RA on NHA was also examined. RA treatment for 24 h or 48 h did not significantly affect NHA cell viability and morphology (Fig. 3E and F). These results indicated that RA specifically inhibited the proliferation of glioma cells, with no significant effect on the proliferation of NHA cells.

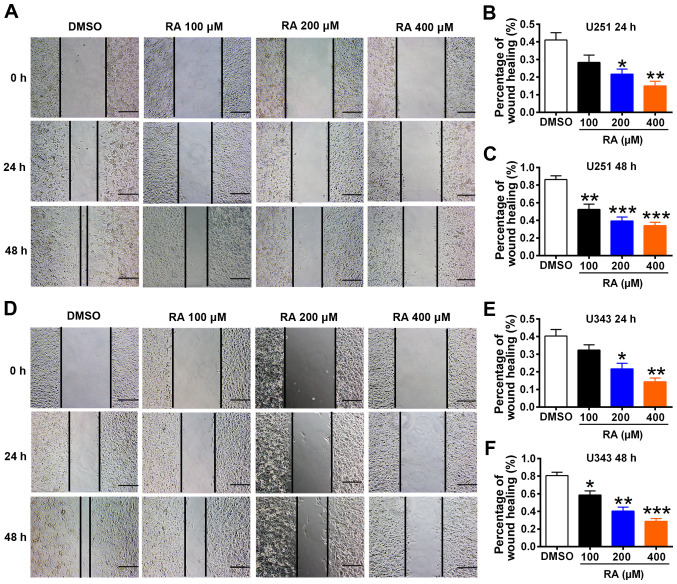

RA inhibits glioma cell migration

Metastasis of rapidly migrating tumor cells is the main cause of mortality for most patients with cancer (33). Therefore, inhibiting migration could be an important strategy to prevent tumor metastasis. the effect of RA on glioma cell migration was examined (Fig. 4). Both U251 and U343 cells exhibited reduced migration after treatment with RA for 24 or 48 h at different concentrations (Fig. 4A and D). Specifically, in the control group of the U251 cell line, wound healing reached 41.0% after 24 h, while it only reached 28.3, 21.6, and 15.0% after treatment with 100, 200, and 400 µM RA, respectively (Fig. 4B). In the control group of the U343 cell line, wound healing reached 40.3% after 24 h, while it only reached 32.3, 21.7, and 14.3% after treatment with 100, 200, and 400 µM RA, respectively (Fig. 4E). At 48 h, wound healing of control U251 and U343 cells reached 86.3% and 80.6%, respectively; and 52.3, 39.3, and 34.0% (U251 cells; Fig. 4C) and 58.7, 40.3, and 28.7% (U343 cells; Fig. 4F) after treatment with 100, 200, and 400 µM RA, respectively.

Figure 4.

RA reduces glioma cell migration. (A) Images of U251 cells immediately after, and at 24 and 48 h post-scratch with the indicated RA concentrations. Scale bar, 200 µm. (B and C) Quantification the wound healing of A. (D) Images of U343 cells immediately after, and at 24 and 48 h post-scratch with the indicated RA concentrations. Scale bar, 200 µm. (E and F) Quantification the wound healing of D. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. the DMSO group. RA, rosmarinic acid.

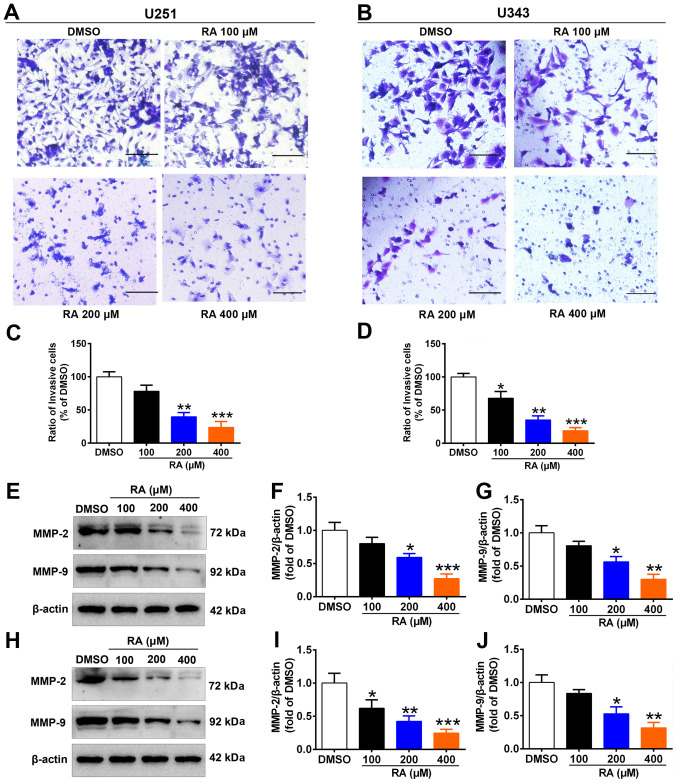

RA inhibits glioma cell invasion

The high invasion capability of glioma cells is the main reason for the high refractory and recurrence rates of glioma (34). Therefore, the effect of RA on glioma cell invasion was assessed using a Matrigel® invasion assay (Fig. 5). RA significantly inhibited invasion through the Matrigel® (Fig. 5A and B). Compared with the control group, the percentage of invading U251 cells was decreased by 21.7, 60.3, and 76.4% after treatment with 100, 200, and 400 µM RA for 24 h, respectively (Fig. 5C); similarly, the percentage of invading U343 cells was decreased by 32, 64.7, and 81%, respectively (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

RA reduces glioma cell invasion and inhibits the expression of related factors. (A) Images of U251 cells after treatment with the indicated concentrations of RA for 24 h. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B) Images of U343 cells after treatment with indicated concentrations of RA for 24 h. Scale bar, 50 µm. (C) Percentage of invasive U251 cells. (D) Percentage of invasive U343 cells. (E) The expression levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were detected by western blotting in U251 cells after treatment with the indicated concentrations of RA for 24 h. (F and G) Densitometric quantification of the bands in E. (H) The expression levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were detected by western blotting in U343 cells after treatment with the indicated concentrations of RA for 24 h. (I and J) Densitometric quantification of the bands in H. The histogram indicates the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. the DMSO group. RA, rosmarinic acid.

Previous studies have reported the role of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and MMP-9 in cancer development, including tumor cell growth, migration, invasion, and metastasis, and particularly so in glioma (35-37). The expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were detected by western blotting. RA dose-dependently inhibited the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in U251 and U343 cells (Fig. 5E-J). Compared with the control group, the expression of MMP-2 in U251 cells was decreased by 20.0, 40.7, and 62.7% (Fig. 5F), and that of MMP-9 was decreased by 19.9, 43.7, and 70% (Fig. 5G), after treatment with 100, 200, and 400 µM for 24 h, respectively. Similarly, the expression of MMP-2 in U343 cells decreased by 38.0, 57.7, and 75.3% (Fig. 5I), and that of MMP-9 was decreased by 16.3, 47.0, and 68.3% (Fig. 5J), after treatment with 100, 200, and 400 µM for 24 h, respectively. These results indicated that RA inhibited glioma cell invasion and migration by reducing the expression of MMPs, thereby providing pathways for the invasion and metastasis of glioma cells.

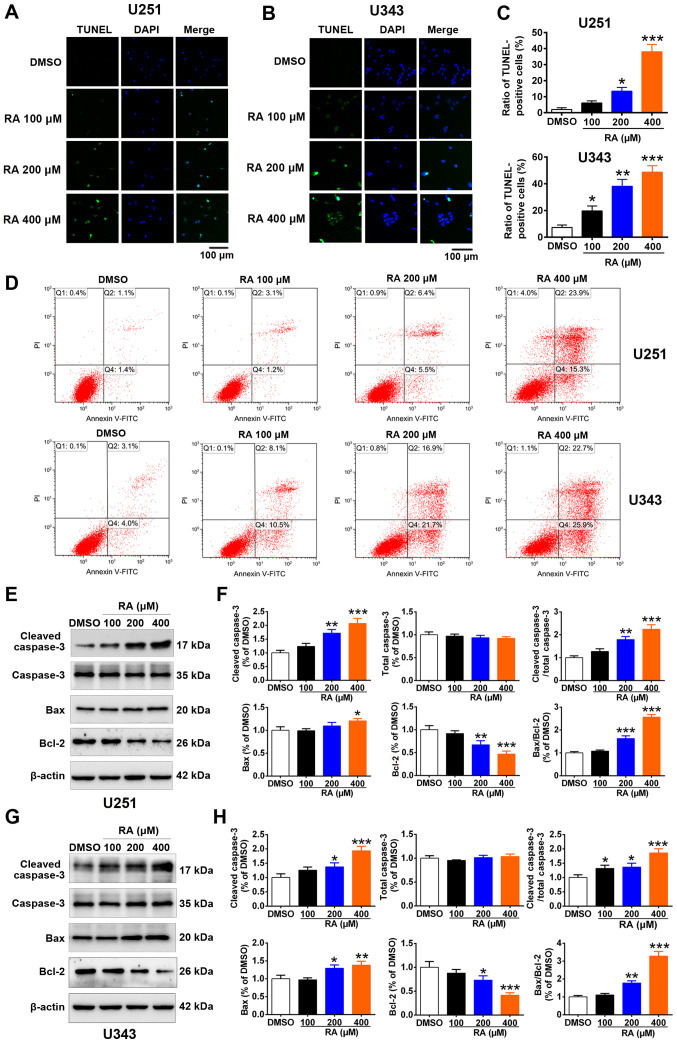

RA increases glioma cell apoptosis

Apoptosis plays a crucial role in cancer treatment (38). Therefore, whether RA could induce apoptosis was investigated. A TUNEL assay revealed that RA significantly induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner in both U251 and U343 cells (Fig. 6A-C). Annexin V/PI dual-staining assays by flow cytometry were also conducted to detect apoptosis after treatment with RA. As revealed in Fig. 6D, compared with the control group, the apoptotic rates of the U251 and U343 cells treated with RA were increased. The apoptosis suppressor protein Bcl-2 and the pro-apoptotic proteins Bax, cleaved caspase-3, and caspase-3 are key in the process of apoptosis in glioma cells (39,40). Caspase-3 is the effector caspase that initiates cell degradation during the final stage of apoptosis, and cleaved caspase3 is the active form of caspase3; Bcl-2, a survival-promoting protein, and Bax, a pro-apoptotic protein, both are members of the Bcl family that play important roles in the regulation of intrinsic apoptotic signaling (39,41). It was determined that RA treatment increased the expression of cleaved caspase-3 and Bax and reduced the expression of Bcl-2 in both U251 and U343 cells (Fig. 6E and G). In addition, RA treatment increased the relative ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 as well as cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3, indicating RA-induced apoptosis in glioma cells. Compared with the control group, the relative ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 in U251 cells was increased by 7.6, 63.0, and 156.3%, and that in U343 cells was increased by 10.7, 77.7, 228.6%, after treatment with 100, 200, and 400 µM RA for 24 h, respectively (Fig. 6F and H). In addition, the relative ratio of cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3 in U251 cells was increased by 27.3, 79.6, and 124.3%, and that in U343 cells was increased by 29.3, 36.3, and 86%, after treatment with 100, 200, and 400 µM RA for 24 h (Fig. 6F and H).

Figure 6.

RA induces glioma cell apoptosis. (A and B) U251 and U343 cells were treated with the indicated doses of RA for 24 h, and then collected for TUNEL staining. Scale bar, 100 µm. (C) Statistical analysis of apoptotic U251 and U343 cells. (D) U251 and U343 cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of RA for 24 h and then analyzed for apoptosis by flow cytometry using the Annexin V/PI dual-staining assay. (E and G) U251 and U343 cells were treated with RA for 24 h. Then, western blotting was conducted to detect the expression of cleaved caspase-3, caspase-3, Bax, and Bcl-2. (F and H) Densitometric quantification of the bands in E and G. The expression of GAPDH was used as an endogenous control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. the DMSO group. RA, rosmarinic acid; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling.

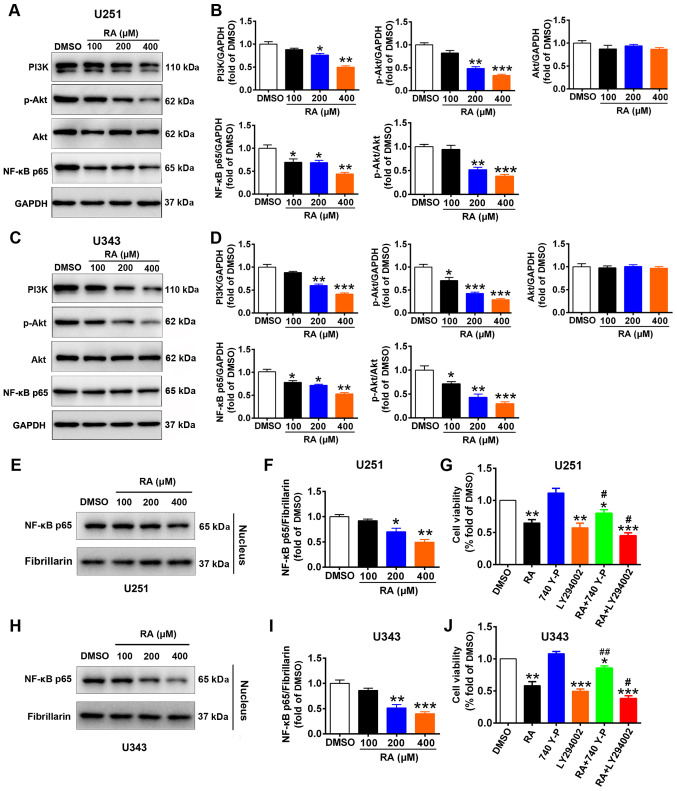

RA inhibits the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway in glioma cells

PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling plays a vital role in cell proliferation, survival, and metabolism, and is constitutively activated in most tumors, including glioma (42-44). Therefore, the effect of RA on the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway was examined. It was revealed that treatment with 100, 200, and 400 µM RA for 24 h significantly decreased the protein expression of PI3K, p-Akt, and NF-κB in U251 and U343 cells compared to control cells (Fig. 7A-D). Specifically, the expression of PI3K was decreased by 11.7, 24, and 50.3% in U251 cells and by 12.0, 40, and 59% in U343 cells, respectively. In U251 cells, the expression of p-Akt was decreased by 18.0, 51.7, and 66.7% and that of NF-κB p65 by 30.7, 31.4, and 56%, respectively. Similarly, in U343 cells, the expression of p-Akt was decreased by 29.4, 57.7, and 71.3% and that of NF-κB p65 by 22.0, 28.4, and 47.0%, respectively. Considering that NF-κB p65 serves as a transcription factor and oncogene (45), the effect of RA on nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 was also investigated. The results revealed that the expression level of NF-κB p65 in the nucleus was significantly inhibited following treatment with RA in U251 and U343 glioma cells (Fig. 7E, F, H and I). To further investigate the mechanisms underlying RA-mediated inhibition of U251 and U343 cells, cell viability was performed. The results revealed that RA significantly inhibited the cell viability of U251 and U343 cells. Moreover, treatment with RA combined with 740 Y-P reversed the RA-induced deccrease in cell viability, and treatment with RA combined with LY294002 enhanced the effects of RA on cell viability (Fig. 7G and J). Collectively, these results indicated that RA may inhibit proliferation of glioma cells via the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway.

Figure 7.

The PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway is involved in RA-induced cytotoxicity in glioma cells. (A) The protein expression of PI3K, p-Akt, Akt, and NF-κB p65 in U251 was assessed by western blotting. (B) Densitometric quantification of the bands in A. (C) The protein expression of PI3K, p-Akt, Akt, and NF-κB p65 in U343 was assessed by western blotting. (D) Densitometric quantification of the bands in C. (E and H) Expression levels of NF-κB p65 in the nucleus were detected by western blotting. (F and I) Densitometric quantification of the bands in E and H. (G and J) Viability of U251 and U343 cells as measured by CCK-8 assay. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD. GAPDH was used as a loading control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. the DMSO group; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 vs. the RA treatment group. RA, rosmarinic acid.

Discussion

In the present study, the effects of RA were explored on the biological characteristics of two glioma cell lines, U251 and U343. It was revealed that RA inhibited proliferation, migration, and invasion and induced apoptosis in both U251 and U343 cells. In general, the effects were dose-dependent. It was also determined that RA significantly reduced the protein levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9, which promote migration and induce invasion, and of the apoptosis suppressor protein Bcl-2; and increased the levels of pro-apoptotic proteins, such as cleaved caspase-3 and Bax in both U251 and U343 cells. Previous research has reported that the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway plays an important role in the growth, proliferation, migration, and invasion of glioma (46). The present study further recognized the importance of PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling in glioma.

Glioma, one of the most common intracranial tumors, is characterized by rapid growth and high aggressiveness (47). To date, neurosurgery is the optimal and most direct treatment for gliomas. However, neurosurgery often fails to completely remove the tumor tissue due to the highly invasive nature of the glioma, and subsequent treatment requires a combination of drug chemotherapy and radiotherapy (48). Radiotherapy of brain tissue often has great side effects, and chemotherapy plays a crucial role in the treatment and prognosis of patients with this cancer (49). However, the efficacy of current chemotherapy options is not often satisfactory due to side effects and the development of drug resistance. Therefore, the identification and development of more efficient and less toxic drugs for the prevention and treatment of glioma is essential.

In recent years, the use of traditional Chinese medicine to treat tumors has attracted increasing attention from researchers owing to the significant curative efficacy and relatively fewer side effects (37,50,51). RA is a medicinal herb that not only is easy to isolate, but can also be ingested from food or tea (52). RA has been reported to have antioxidant, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory effects and has been used in an Egyptian herbal tea for the prevention of cancer (53). Furthermore, RA was revealed to significantly improve the efficiency of radiotherapy by exerting a radiosensitizing effect on tumor cells (54). In addition, it enhanced chemosensitivity of resistant gastric carcinoma cells to 5-Fu by downregulating miR-642a-3p and miR-6785-5p and increasing FOXO4 expression (28). Various studies have revealed that RA has antineoplastic activity in leukemia, hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and small-cell carcinoma of the lung (26-29). However, the effects of RA on the biological characteristics of glioma is limited.

The present study revealed that RA inhibited the expression of Fyn in a dose-dependent manner in U251 and U343 cells. This provides a theoretical basis for its antitumor effects in glioma. High invasion and rapid proliferation are the main reasons for refractory glioma and poor prognosis of glioma (34). Cell viability assay and morphological observation revealed that RA inhibited the growth of glioma in a time- and dose-dependent manner. Concurrently, it had little effect on NHA cell proliferation and morphology. This suggested that RA may be a promising antitumor drug based on its weak toxicity. The present study also demonstrated that RA inhibited glioma cell invasion. Since MMP-2 and MMP-9 are important regulators of invasion, the effect of RA on their expression levels was also examined. Western blotting revealed that treatment with RA decreased MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression in glioma cells. The main feature of tumor metastasis is the migration of cancer cells from the initial tumor site to the circulatory system or lymphatic system (55). Therefore, inhibiting tumor cell migration could reduce metastasis. In the present study, RA inhibited migration of U251 and U343 cells. Considering that apoptosis is a crucial antitumor mechanism (56), it was investigated whether RA could induce apoptosis in glioma cells. The percentage of apoptotic U251 and U343 cells was significantly increased after treatment with RA. As Bcl-family proteins are main regulators of apoptosis (57), the effect of RA on the expression of Bax and Bcl-2 was also examined. RA increased Bax expression and decreased Bcl-2 expression in glioma cells. Correspondingly, the expression of cleaved (activated) caspase-3, but not that of total caspase-3, was increased by RA. In addition, the Bax/Bcl-2 and cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3 ratios were increased by RA, thus providing a mechanistic basis for the induction of apoptosis by RA in glioma cells. These results are similar to the reported role of RA in colorectal cancer (37). Numerous studies have revealed that the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB pathway is closely related to glioma progression (46,58,59). In line with these studies, the present results revealed that the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway was involved in the antitumor effects of RA in glioma.

Collectively, these findings indicated that the antitumor effects of RA in glioma may be mediated by Fyn inhibition. The detailed mechanisms warrant further investigation in vitro and in vivo.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The present research was funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no. 2019M663104) and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (grant no. 2017A020215089).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

BH and GH conceived and designed the study. YL, XX, HT and YP performed the experiments. YL, XX and HT analyzed the data. YL, BH and GH wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lapointe S, Perry A, Butowski NA. Primary brain tumours in adults. Lancet. 2018;392:432–446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30990-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senders JT, Harary M, Stopa BM, Staples P, Broekman MLD, Smith TR, Gormley WB, Arnaout O. Information-based medicine in glioma patients: A clinical perspective. Comput Math Methods Med. 2018;2018:8572058. doi: 10.1155/2018/8572058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batash R, Asna N, Schaffer P, Francis N, Schaffer M. Glioblastoma multiforme, diagnosis and treatment; recent literature review. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24:3002–3009. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170516123206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang S, Liao K, Miao Z, Wang Q, Miao Y, Guo Z, Qiu Y, Chen B, Ren L, Wei Z, et al. CircFOXO3 promotes glioblastoma progression by acting as a competing endogenous RNA for NFAT5. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21:1284–1296. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noz128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Sehemy A, Selvadurai H, Ortin-Martinez A, Pokrajac N, Mamatjan Y, Tachibana N, Rowland K, Lee L, Park N, Aldape K, et al. Norrin mediates tumor-promoting and -suppressive effects in glioblastoma via Notch and Wnt. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:3069–3086. doi: 10.1172/JCI128994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis-Tuffin LJ, Feathers R, Hari P, Durand N, Li Z, Rodriguez FJ, Bakken K, Carlson B, Schroeder M, Sarkaria JN, Anastasiadis PZ. Src family kinases differentially influence glioma growth and motility. Mol Oncol. 2015;9:1783–1798. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irby RB, Yeatman TJ. Role of Src expression and activation in human cancer. Oncogene. 2000;19:5636–5642. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Summy JM, Gallick GE. Src family kinases in tumor progression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:337–358. doi: 10.1023/A:1023772912750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frame MC. Src in cancer: Deregulation and consequences for cell behaviour. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1602:114–130. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(02)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tornillo G, Knowlson C, Kendrick H, Cooke J, Mirza H, Aurrekoetxea-Rodríguez I, Vivanco MDM, Buckley NE, Grigoriadis A, Smalley MJ. Dual mechanisms of LYN kinase dysregulation drive aggressive behavior in breast cancer cells. Cell Rep. 2018;25:3674–3692.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emaduddin M, Bicknell DC, Bodmer WF, Feller SM. Cell growth, global phosphotyrosine elevation, and c-Met phosphorylation through Src family kinases in colorectal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2358–2362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712176105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masaki T, Okada M, Tokuda M, Shiratori Y, Hatase O, Shirai M, Nishioka M, Omata M. Reduced C-terminal Src kinase (Csk) activities in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1999;29:379–384. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yadav V, Denning MF. Fyn is induced by Ras/PI3K/Akt signaling and is required for enhanced invasion/migration. Mol Carcinog. 2011;50:346–352. doi: 10.1002/mc.20716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu KV, Zhu S, Cvrljevic A, Huang TT, Sarkaria S, Ahkavan D, Dang J, Dinca EB, Plaisier SB, Oderberg I, et al. Fyn and SRC are effectors of oncogenic epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in glioblastoma patients. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6889–6898. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han X, Zhang W, Yang X, Wheeler CG, Langford CP, Wu L, Filippova N, Friedman GK, Ding Q, Fathallah-Shaykh HM, et al. The role of Src family kinases in growth and migration of glioma stem cells. Int J Oncol. 2014;45:302–310. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Comba A, Dunn PJ, Argento AE, Kadiyala P, Ventosa M, Patel P, Zamler DB, Núñez FJ, Zhao L, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Fyn tyrosine kinase, a downstream target of receptor tyrosine kinases, modulates antiglioma immune responses. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22:806–818. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noaa006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowman RL, Wang Q, Carro A, Verhaak RG, Squatrito M. GlioVis data portal for visualization and analysis of brain tumor expression datasets. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19:139–141. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jelić D, Mildner B, Kostrun S, Nujić K, Verbanac D, Culić O, Antolović R, Brandt W. Homology modeling of human Fyn kinase structure: Discovery of rosmarinic acid as a new Fyn kinase inhibitor and in silico study of its possible binding modes. J Med Chem. 2007;50:1090–1100. doi: 10.1021/jm0607202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Şengelen A, Önay-Uçar E. Rosmarinic acid and siRNA combined therapy represses Hsp27 (HSPB1) expression and induces apoptosis in human glioma cells. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2018;23:885–896. doi: 10.1007/s12192-018-0896-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juskowiak B, Bogacz A, Wolek M, Kamiński A, Uzar I, Seremak-Mrozikiewicz A, Czerny B. Expression profiling of genes modulated by rosmarinic acid (RA) in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Ginekol Pol. 2018;89:541–545. doi: 10.5603/GP.a2018.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang SY, Hong CO, Lee GP, Kim CT, Lee KW. The hepatoprotection of caffeic acid and rosmarinic acid, major compounds of Perilla frutescens, against t-BHP-induced oxidative liver damage. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;55:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu X, Ci X, He J, Jiang L, Wei M, Cao Q, Guan M, Xie X, Deng X, He J. Effects of a natural prolyl oligopeptidase inhibitor, rosmarinic acid, on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Molecules. 2012;17:3586–3598. doi: 10.3390/molecules17033586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin CS, Kuo CL, Wang JP, Cheng JS, Huang ZW, Chen CF. Growth inhibitory and apoptosis inducing effect of Perilla frutescens extract on human hepatoma HepG2 cells. J Ethnopharmaco. 2007;112:557–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelsey NA, Wilkins HM, Linseman DA. Nutraceutical antioxidants as novel neuroprotective agents. Molecules. 2010;15:7792–7814. doi: 10.3390/molecules15117792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu CF, Hong C, Klauck SM, Lin YL, Efferth T. Molecular mechanisms of rosmarinic acid from Salvia miltiorrhiza in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. J Ethnopharmaco. 2015;176:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xavier CP, Lima CF, Fernandes-Ferreira M, Pereira-Wilson C. Salvia fruticosa, Salvia officinalis, and rosmarinic acid induce apoptosis and inhibit proliferation of human colorectal cell lines: The role in MAPK/ERK pathway. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61:564–571. doi: 10.1080/01635580802710733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu C, Chen DQ, Liu HX, Li WB, Lu JW, Feng JF. Rosmarinic acid reduces the resistance of gastric carcinoma cells to 5-fluorouracil by downregulating FOXO4-targeting miR-6785-5p. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:2327–2334. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yesil-Celiktas O, Sevimli C, Bedir E, Vardar-Sukan F. Inhibitory effects of rosemary extracts, carnosic acid and rosmarinic acid on the growth of various human cancer cell lines. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2010;65:158–163. doi: 10.1007/s11130-010-0166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li W, Du Q, Li X, Zheng X, Lv F, Xi X, Huang G, Yang J, Liu S. Eriodictyol Inhibits Proliferation, Metastasis and induces apoptosis of glioma cells via PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:114. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ko HM, Lee SH, Kim KC, Joo SH, Choi WS, Shin CY. The role of TLR4 and fyn interaction on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated PAI-1 expression in astrocytes. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;52:8–25. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8837-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang T, Ji D, Wang P, Liang D, Jin L, Shi H, Liu X, Meng Q, Yu R, Gao S. The atypical protein kinase RIOK3 contributes to glioma cell proliferation/survival, migration/invasion and the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2018;415:151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yachida S, Jones S, Bozic I, Antal T, Leary R, Fu B, Kamiyama M, Hruban RH, Eshleman JR, Nowak MA, et al. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467:1114–1117. doi: 10.1038/nature09515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marín-Ramos NI, Thein TZ, Cho HY, Swenson SD, Wang W, Schönthal AH, Chen TC, Hofman FM. NEO212 inhibits migration and invasion of glioma stem cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17:625–637. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan H, Xue W, Zhao W, Schachner M. Expression and function of chondroitin 4-sulfate and chondroitin 6-sulfate in human glioma. FASEB J. 2020;34:2853–2868. doi: 10.1096/fj.201901621RRR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szabo E, Schneider H, Seystahl K, Rushing EJ, Herting F, Weidner KM, Weller M. Autocrine VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 signaling promotes survival in human glioblastoma models in vitro and in vivo. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18:1242–1252. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han YH, Kee JY, Hong SH. Rosmarinic Acid Activates AMPK to inhibit metastasis of colorectal cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:68. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niknejad H, Yazdanpanah G, Ahmadiani A. Induction of apoptosis, stimulation of cell-cycle arrest and inhibition of angiogenesis make human amnion-derived cells promising sources for cell therapy of cancer. Cell Tissue Res. 2016;363:599–608. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2364-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Tang H, Zhang Y, Li J, Li B, Gao Z, Wang X, Cheng G, Fei Z. Saponin B, a novel cytostatic compound purified from Anemone taipaiensis, induces apoptosis in a human glioblastoma cell line. Int J Mol Med. 2013;32:1077–1084. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su CC, Wang MJ, Chiu TL. The anti-cancer efficacy of curcumin scrutinized through core signaling pathways in glioblastoma. Int J Mol Med. 2010;26:217–224. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang WF, Yang Y, Li X, Xu DY, Yan YL, Gao Q, Jia AL, Duan MH. Angelica polysaccharides inhibit the growth and promote the apoptosis of U251 glioma cells in vitro and in vivo. Phytomedicine. 2017;33:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang SX, Polley E, Lipkowitz S. New insights on PI3K/AKT pathway alterations and clinical outcomes in breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;45:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arlt A, Gehrz A, Müerköster S, Vorndamm J, Kruse ML, Fölsch UR, Schäfer H. Role of NF-kappaB and Akt/PI3K in the resistance of pancreatic carcinoma cell lines against gemcitabine-induced cell death. Oncogene. 2003;22:3243–3251. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomar VS, Patil V, Somasundaram K. Temozolomide induces activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in glioma cells via PI3K/Akt pathway: Implications in glioma therapy. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2020;36:273–278. doi: 10.1007/s10565-019-09502-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song L, Chen X, Mi L, Liu C, Zhu S, Yang T, Luo X, Zhang Q, Lu H, Liang X. Icariin-induced inhibition of SIRT6/NF-κB triggers redox mediated apoptosis and enhances anti-tumor immunity in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:4242–4256. doi: 10.1111/cas.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fahey JM, Korytowski W, Girotti AW. Upstream signaling events leading to elevated production of pro-survival nitric oxide in photodynamically-challenged glioblastoma cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;137:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Furnari FB, Fenton T, Bachoo RM, Mukasa A, Stommel JM, Stegh A, Hahn WC, Ligon KL, Louis DN, Brennan C, et al. Malignant astrocytic glioma: Genetics, biology, and paths to treatment. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2683–2710. doi: 10.1101/gad.1596707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karachi A, Dastmalchi F, Mitchell DA, Rahman M. Temozolomide for immunomodulation in the treatment of glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20:1566–1572. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patil SA, Hosni-Ahmed A, Jones TS, Patil R, Pfeffer LM, Miller DD. Novel approaches to glioma drug design and drug screening. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2013;8:1135–1151. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2013.807248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie JH, Lai ZQ, Zheng XH, Xian YF, Li Q, Ip SP, Xie YL, Chen JN, Su ZR, Lin ZX, Yang XB. Apoptosis induced by bruceine D in human non-small-cell lung cancer cells involves mitochondrial ROS-mediated death signaling. Int J Mol Med. 2019;44:2015–2026. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2019.4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ong SKL, Shanmugam MK, Fan L, Fraser SE, Arfuso F, Ahn KS, Sethi G, Bishayee A. Focus on formononetin: Anticancer potential and molecular targets. Cancers. 2019;11:611. doi: 10.3390/cancers11050611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Petersen M, Simmonds MS. Rosmarinic acid. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:121–125. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00513-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elansary HO, Mahmoud EA. Egyptian herbal tea infusions' antioxidants and their antiproliferative and cytotoxic activities against cancer cells. Nat Prod Res. 2015;29:474–479. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2014.951354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alcaraz M, Alcaraz-Saura M, Achel DG, Olivares A, López- Morata JA, Castillo J. Radiosensitizing effect of rosmarinic acid in metastatic melanoma B16F10 cells. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:1913–1921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCall B, McPartland CK, Moore R, Frank-Kamenetskii A, Booth BW. Effects of astaxanthin on the proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells in vitro. Antioxidants (Basel) 2018;7:135. doi: 10.3390/antiox7100135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shin J, Song MH, Oh JW, Keum YS, Saini RK. Pro-oxidant actions of carotenoids in triggering apoptosis of cancer cells: A review of emerging evidence. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020;9:532. doi: 10.3390/antiox9060532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chowdhury I, Thompson WE, Welch C, Thomas K, Matthews R. Prohibitin (PHB) inhibits apoptosis in rat granulosa cells (GCs) through the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and the Bcl family of proteins. Apoptosis. 2013;18:1513–1525. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0901-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yan J, Xu C, Li Y, Tang B, Xie S, Hong T, Zeng E. Long non-coding RNA LINC00526 represses glioma progression via forming a double negative feedback loop with AXL. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:5518–5531. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nakabayashi H, Shimizu K. Involvement of Akt/NF-κB pathway in antitumor effects of parthenolide on glioblastoma cells in vitro and in vivo. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:453. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.