Abstract

This paper presents the results of a qualitative study designed to explore and identify the resources that probation officers need to implement specialized mental health probation caseloads, a promising practice that enhances mental health treatment engagement and reduces recidivism among people with mental illnesses. Our research team conducted a directed content analysis guided by the Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM) to analyze qualitative interviews with 16 specialty mental health probation officers and their supervising chiefs. Results indicated five components and resources related to multiple PRISM constructs: (1) meaningfully reduced caseload sizes (intervention design), (2) officers’ ability to build rapport and individualize probation (organizational staff characteristics), (3) specialized training that is offered regularly (implementation and sustainability infrastructure), (4) regular case staffing and consultation (implementation and sustainability infrastructure), and (5) communication and collaboration with community-based providers (external environment). Agencies implementing specialized mental health probation approaches should pay particular attention to selecting officers and chiefs and establishing the infrastructure to implement and sustain specialty mental health probation.

Keywords: Mental illness, Probation, Implementation science, Criminal justice, Substance use

Introduction

Specialized probation approaches for supervising adults with mental illnesses are widespread, with more than 130 agencies reporting implementation of mental health probation caseloads (Skeem et al. 2006). The proliferation of these specialized approaches has been driven by: (1) the high prevalence of mental illnesses among those under community supervision (Ditton 1999; Crilly et al. 2009; Van Deinse et al. 2018); (2) a national call for specialized approaches to supervise individuals with mental illnesses (Council of State Governments 2002); and (3) emergent research on the effectiveness of specialized mental health probation (SMHP) on improving mental health and criminal justice outcomes (Manchak et al. 2014; Skeem et al. 2017; Wolff et al. 2014). Despite this increased attention, little is known about the real-world implementation of specialized mental health supervision approaches or the resources officers need to deliver them.

High rates of mental illnesses among individuals supervised on probation (Ditton 1999; Crilly et al. 2009; Van Deinse et al. 2018) create significant challenges for criminal justice authorities and individuals supervised on probation who have mental illnesses often experience difficulties meeting supervision requirements (CSG 2002; Eno Louden and Skeem 2011; Porporino and Motiuk 1995; Van Deinse et al. 2017; Skeem and Eno Louden 2006). To address the needs of individuals with mental illnesses within the criminal justice system, the Council of State Governments (CSG) outlined a series of actionable policy statements to guide interventions at the interface of the mental health and criminal justice systems. Recommendations for improving community supervision of individuals with mental illnesses include modified supervision conditions (e.g. treatment requirements, frequency of supervision visits), greater attention to psychosocial needs, continuity in federal and state benefits, assigning individuals to specially trained officers with reduced caseload sizes, and establishing guidelines for managing compliance and violation issues (CSG 2002). While emphasizing flexibility in tailoring supervision approaches to individual and local community needs, CSG’s report acknowledged the heterogeneity of existing specialized mental health probation models across the United States (CSG 2002).

Shortly after CSG’s call to improve community supervision approaches for adults with mental illnesses, Skeem et al. (2006) published results from a nationwide survey that described the variation in specialized mental health probation (SMHP) approaches and delineated a prototypical SMHP model comprised of five common elements: (1) caseloads composed exclusively of adults with mental illnesses; (2) small caseloads (i.e., less than 50 individuals); (3) sustained mental health training for officers; (4) a problem-solving supervision orientation; and (5) collaboration with internal and external resources to link individuals with supports. Although a number of studies assessing specialty supervision approaches have examined practices similar to SMHP core elements—such as dual role relationships, problem-solving approaches, and boundary spanning roles (Eno Louden et al. 2008, 2012; Kennealy et al. 2012; Skeem et al. 2007a, b; Skeem and Petrila 2004; Steadman 1992)—the prototypical model advanced by Skeem and colleagues specified a core set of practices, thereby reducing model heterogeneity and promoting replicability. Prior research has demonstrated SMHP is an evidence-informed practice for achieving improvements in supervised individuals’ mental health outcomes (e.g., feelings of loneliness, quality of life, treatment engagement) and a reduction in the number of jail days experienced while on probation (Manchak et al. 2014; Skeem et al. 2017; Wolff et al. 2014).

Although a number of studies have examined SMHP’s effectiveness (Manchak et al. 2014; Skeem et al. 2017; Wolff et al. 2014), there is a dearth of research examining real-world implementation, namely the factors necessary to promote uptake of prototypical SMHP components associated with improved supervision outcomes. This failure to simultaneously focus on implementation and effectiveness is a significant gap in the SMHP research. Specifically, greater attention is needed to understand how probation officers operationalize the core components of SMHP and what kinds of resources are required for SMHP implementation success (Manchak et al. 2014). This gap in the literature is particularly problematic because interventions such as SMHP are often transdisciplinary and complex and are impacted by internal, external, and cross-agency factors, which can inhibit practice implementation and their overall effectiveness.

The lack of focus on SMHP implementation has led to two key challenges. First, core components of the SMHP model are not sufficiently specified. Although some components of the model, such as caseload size (i.e., fewer than 50 individuals) and designated mental health caseloads, are specific and easily measured, community supervision agencies’ interpretation and operationalization of other model components is less clear. Second, the lack of focus on how to implement core model components may result in variation in stakeholders’ understanding about which components are essential to officers’ ability and capacity for implementing SMHP. Failure to understand the resources needed for officers to competently supervise a mental health caseload using SMHP practices can result in poor implementation, overall practice dilution due to model variation, and challenges sustaining SMHP. To address these gaps, the present study used qualitative methods to explore and describe the real-world implementation of SMHP, explicate core SMHP components, and identify resources needed to effectively implement the SMHP model.

Method

Study Context

In 2015, a research team from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill partnered with a Department of Public Safety in a southeastern state to implement specialty mental health probation in six counties. The research team used a type I implementation-effectiveness hybrid design (Curran et al. 2012) to simultaneously examine both effectiveness outcomes and implementation outcomes associated with the uptake and delivery of SMHP. The implementation arm of the hybrid study had two objectives: (1) to pilot implementation strategies to enhance uptake of SMHP and (2) to further explicate the core components of SMHP and critical resources needed for its implementation. In this manuscript, we report on results from the second objective of the implementation study.

All study activities were reviewed and approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. To promote rigor and transparency in reporting qualitative methods and results, the researchers cross-walked their data collection, analysis and reporting processes to those outlined in the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) checklist (O’Brien et al. 2014). SRQR is endorsed by the Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research (EQUATOR) network as a tool to ensure qualitative methods are clearly defined and promote reproducibility.

Data Collection and Sample

All SMHP officers (n = 9) and their corresponding chief probation officers (i.e., supervisors; n = 9) from the six counties in the study were recruited to participate in hour-long semi-structured interviews. Individual interviews were conducted in a confidential space of the participants’ choosing, such as a private space within the community corrections office, or they were conducted over the phone. All interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed to promote accuracy.

Of the 18 stakeholders recruited, 16 (9 SMHP officers, 7 chief probation officers) participated in the qualitative interviews. Two individuals were unable to participate due to schedule conflicts. Of the 16 participants, 56% (n = 9) were White, 44% (n = 7) were Black or African American, 56% (n = 9) were male and 44% (n = 7) were female. On average, participants had been working on the SMHP initiative for two years (SD = 1.22), had served in their current position for 6.4 years (SD = 4.57), and had worked in corrections in general for 13.5 years (SD = 8.26).

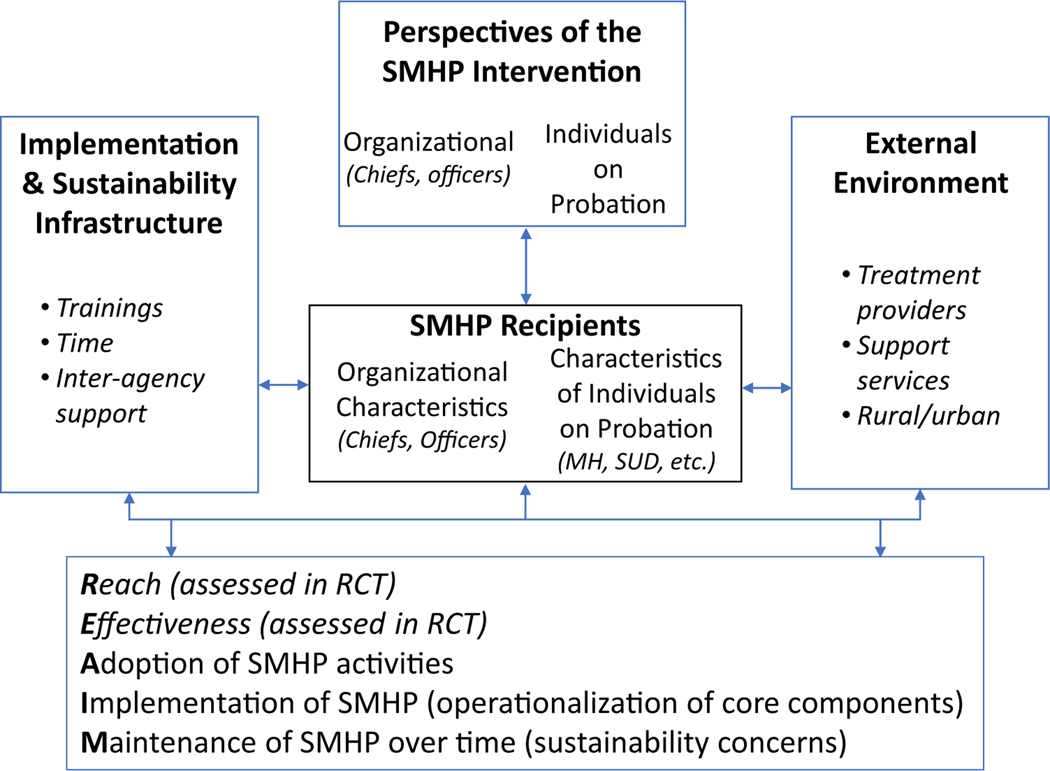

The Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM) informed our discussion guide and analytic approach (Fig. 1; Feldstein and Glasgow 2008). PRISM is a seminal implementation science theoretical model that describes how an intervention is viewed by stakeholders who may act as target recipients of the intervention or who may be tapped to deliver the new practice. Both external environmental factors and internal implementation and sustainability infrastructure influence stakeholders’ perception of and interaction with the intervention. Together these interactions are hypothesized to impact the overall reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance of the intervention (Feldstein and Glasgow 2008). In our study, PRISM posits that officers and chiefs are the core stakeholders for whom the delivery of SMHP is impacted by multiple influences, including their interpretation of the SMHP core components, the availability of Department of Public Safety implementation and sustainability infrastructure and/or resources to support SMHP delivery, and any external environmental factors, including other community resources or needs that might influence provision of SMHP.

Fig. 1.

Modified Practical, Robust Implementation & Sustainability Model (PRISM). This figure depicts the application of PRISM to specialty mental health probation

The semi-structured interview guide was designed to inquire about the aforementioned PRISM constructs, namely perspectives of the intervention, recipient characteristics, implementation and sustainability infrastructure, and external environment. SMHP officers and chiefs were asked to describe: (1) their perspectives on the core components of SMHP, including ideal caseload size and number of people with mental illnesses they supervised (perspectives of the intervention), and whether they supervised an exclusively mental health or mixed caseload; (2) officers’ and chiefs’ personal characteristics, background, and examples of how they and their colleagues identify and supervise people with mental illnesses (recipients construct); (3) the type and frequency of specialized trainings and other professional resources officers and chiefs have participated in or need to implement the SMHP model (implementation and sustainability infrastructure construct); and (4) the influence of external environmental factors on SMHP delivery and adaptations, such as relationships with and the availability of community behavioral health treatment providers, which are examples of supervision challenges or facilitators related to working in a rural or urban setting (external environment construct). Finally, participants were asked to share any additional topics or stories they felt were important to their SMHP experiences. The research team did not inquire directly about the interventions’ reach or effectiveness given those measures were addressed by the effectiveness arm of the study. The interview also included questions about supports or other factors that would help sustain specialty mental health probation.

Data Analysis

We conducted a directed content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon 2005) guided by PRISM to identify qualitative themes. The research team included two graduate-level researchers trained in qualitative content analysis and NVivo software, as well as two senior qualitative researchers with implementation science expertise who provided initial and ongoing directed content analysis training specific to the conceptual framework. Members of the research team independently reviewed interview transcripts to generate initial codes related to PRISM constructs (i.e., intervention perspectives and recipients, external environment, implementation and sustainability infrastructure), as they were operationalized through the lens of the SMHP intervention For example, interviewee comments about the core SMHP components or mission were coded to intervention perspectives.

Codes were defined with inclusion and exclusion criteria in an initial codebook that was developed based on team consensus of operational definitions derived from the theoretical model and analysts’ qualitative memos. All interviews were double-coded to promote rigor and establish coding consensus. Each coder independently coded two transcripts before meeting with their paired coder to compare coding and identify discrepancies. Coding disagreements were discussed with the larger research team and resolved through consensus decision-making so that final code applications represented complete agreement across coders. A senior qualitative researcher experienced in applying PRISM constructs served as a tiebreaker for any decisions that could not be resolved with consensus. The process of double coding and group discussion was repeated until all transcripts were coded. The research team kept a log of coding discrepancies, resolutions, and updated the codebook as needed.

To identify relevant themes, researchers reviewed and wrote descriptive summaries of data coded to each of the codebook codes. These summaries were useful for understanding common experiences regarding each model construct (e.g. how participants perceived the SMHP intervention). The research team discussed construct summaries to identify and reach consensus on final themes. All coding and analysis were conducted in NVivo version 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd. 2018).

Results

Qualitative analysis suggested five components and resources related to multiple PRISM constructs: (1) meaningfully reduced caseload sizes (perspectives of the intervention), (2) officer ability to build rapport and individualize probation (organizational staff characteristics), (3) specialized training that is offered regularly (implementation and sustainability infrastructure), (4) regular case staffing and consultation (implementation and sustainability infrastructure), and (5) communication and collaboration with community-based providers (external environment).

Theme 1: Meaningfully Reduced Caseload Size is Critical to Delivering Quality SMHP

Data coded to perspectives of the intervention revealed that officers and chiefs identified reduced caseload size as a critical component for delivering and sustaining SMHP. First, stakeholders stressed the importance of lower caseload sizes to maintain the quality of SMHP, implement the key ingredients of the model, and to complete other supervision duties. For example, one officer explained:

I think anything over 40, I don’t know if you’ll get the quality of work that is expected from having this specialty caseload… So if it increased with some of the other things as far as trainings, meetings, court, that we have outside of just office visits, it wouldn’t be possible to still have the quality with the quantity.—Officer 11

In addition, participants reported that the larger caseload sizes decreased the amount of time spent with individuals on their caseload and consequently hindered specialty officers’ ability to identify and respond to individual needs or address supervision challenges. This concern was expressed by both chiefs and officers:

Any time they can get the caseload numbers down lower, it will allow the officer to be more involved in the individual. So lower numbers always mean, to me, better productivity in terms of what are you giving your offender, whether they are mental health or just a traditional offender.—Chief 15

The difficulty of addressing individuals’ needs when supervising large caseloads was further illustrated by this SMHP officer’s response:

I went to someone’s house last week and I spent about an hour… He was another one who he’s picked up new charges and because he uses [drugs] he goes out and gets new charges. And then his housing was unstable. Because of the new charges he got evicted. And so trying to figure out where he’s going to live, and then make sure he’s coming to court… But if I had more people, like I probably … I’ll be so focused on trying to get to the next house and the next house instead of just being able to take that time to sit with that person and really finding some good information that’s going to help me, because I have to go out to this person’s house.—Officer 6

Theme 2: Officers’ Ability to Empathize, Problem-Solve and Individualize Supervision is Critical to SMHP Delivery

Within PRISM, characteristics of recipients influence intervention implementation processes and outcomes. Study participants described a number of officer characteristics that were essential for implementing SMHP, namely officers’ ability to build rapport, tailor supervision approaches, empathize, and problem-solve with an individual on their caseload. All officers indicated that individuals with mental illnesses on their caseloads had unique needs and a one-size-fits-all approach to supervision was not appropriate. Consequently, officers reported that tailoring probation approaches within the boundaries of the terms of probation was necessary. Officers indicated that in order to tailor supervision approaches, they needed to first build rapport with the people they supervised. Building rapport helped officers utilize the personal knowledge they learned about individuals to develop creative problem-solving approaches when individuals violated their probation terms. For instance, one chief officer described the role of officer compassion in building rapport as follows:

The human side of it is always a win–win with this. Just being human. Because we can be rigid and we can be law enforcement side, but just the human, compassionate side of understanding their illness. Understanding their challenges. Understanding what they face day-to-day in the task on hand. I love the fact that the officers don’t jump at somebody, they don’t accuse them and they don’t blame them. They sit down and have a very reasonable conversation in terms of problem solving to figure out what the issue is before they react, respond or release them. And so the communication part of it has been phenomenal, and that compassion part of problem solving skills.—Chief 13

Further, officers and chiefs believed that engaging in initial supervision meetings with empathy was critical to understanding individuals’ behavioral health and supervision needs and understanding their past experiences with supervision. Showing empathy and understanding helped officers build rapport from the outset, employ creative problem-solving approaches (e.g. role playing, motivational interviewing), and develop client-specific supervision requirements or alternative penalties when probation terms were violated. Officers and chiefs attributed officers’ ability to build rapport, engage in creative problem-solving, and individualize supervision to officers’ personality and personal values. As one officer stated:

I think I come off as a kind of caring person, but at the same time I don’t want my offenders to take my caring or my niceness for their advantage. But overall, I think I have the skills to do it, to cope, for them to talk to me, to open rapport and things like that.—Officer 12

Chiefs also linked SMHP officers’ personalities to their skills in supervising individuals with mental illnesses, as illustrated by the following quote:

He’s truly the kind of officer that needs to be over that type of population because he doesn’t make them feel like they’re a burden. It’s not that he won’t complain about them once they’re gone, but I’ve never seen him huffy or [ask] ‘Why are you here? Why are you calling me again? Why are you showing up again?’ And that was some of the stuff that I would see before. You could just hear it in the officer’s voice that, ‘oh, why are you here again?’ You know the offender can … if I can read it, they can read it. And I don’t see that with him. I mean he is definitely a breath of fresh air dealing with the mental health population.—Chief 1

Theme 3: Specialized Trainings Need to be Offered Regularly to Officers and Their Chiefs

With respect to implementation and sustainability infrastructure, SMHP officers and chiefs indicated that the trainings offered as part of this initiative were critical supports in implementing the model. Trainings helped officers assess the diverse behavioral health experiences they encountered and enabled them to simultaneously consider individuals’ behavioral health needs while promoting compliance with the terms of supervision. Officers participated in specialized trainings that covered a range of mental health and substance use disorder-related topics, including Mental Health First Aid (Kitchener and Jorm 2002, 2006), suicide prevention, and Dual Disorder Motivational Interviewing (Martino et al. 2002). Some trainings were conducted as online learning modules or two-day, in-person training sessions that included all specialty probation officers and their chiefs across the state. In addition, specialty officers participated in traditional crisis intervention team (CIT; Compton et al. 2008) training, which entailed a 40-hour program that required a week of protected time from supervision duties. Officers frequently described training as a way to augment their SMHP supervision skills, including recognizing the signs of mental health crisis. For example, one officer commented on the value of CIT training as follows:

Crisis intervention training. That’s an awesome training. That’s a training that helps us to recognize and respond to folks having mental health crisis. And that’s a 40-hour training and it was very, it was pretty good. We also did the mental health first aid training. That was very good as well. Looking at mental health from a DSM perspective, what type of behaviors to look for. Does that person have Downs syndrome? Does that person have some developmental issues why they behave like that? … It’s almost like doing CPR first aid, assessing the scene, making a decision to go in, stuff like that. So I’m more cognizant of my surroundings when it comes to mental health that way. And this training was essential.—Officer 14

Officers frequently described a willingness and desire to participate in additional ongoing trainings, especially sessions focused on medication management and how to manage individuals who are in crisis while waiting for professional mental health providers to arrive. For example, one officer stated the following:

As an officer you’re always continuing to get better and you want to get better. And of course your motivational interviewing, those things are extremely important. And I think that there’s always room to improve; and it’s definitely helped me.[The training] has definitely helped me with motivational interviewing and asking more open-ended questions.—Officer 4

Ongoing trainings were also valued because they provided officers with regular opportunities to meet with diverse mental health providers, social service agency representatives, and other treatment support services, as illustrated by the following quote:

They put on like a workshop where you have a whole bunch of providers in the same place. But even though you have mirroring, several mirroring providers, each provider was unique in the way they provided service. So that was good… That gives us a plethora of resources to deal with. So those things are good. Those resource services are pretty good. It keeps the resource book refreshed to see what’s there, what works, because if it doesn’t work they’re going to fade away anyway. So we just need those to be refreshed quite often.—Officer 14

In addition to training for officers, chiefs reported needing specialized training in order to provide feedback and guidance to the officers. However, chiefs reported barriers (e.g., the lack of protected time in their schedules) that inhibited their participation in regular trainings. Inability to participate in specialized trainings left chiefs feeling unable to adequately support their officers who were developing additional mental health or substance use-related expertise. As one chief officer explained:

I haven’t gone to any of the special trainings that the officers have gone to… I would love to go so that I would understand kind of how they’re doing their job. I mean I really rely on [my SMHP officer] and trust what he tells me because he’s been to those trainings that I haven’t been to. So I don’t feel like I can tell him he’s wrong when I don’t really know. I mean I would go to them. I think any chief over a specialty should go to the trainings their officer goes to. Otherwise, the officers are smarter than the person who’s supposed to be supervising them, which doesn’t make sense to me.—Chief 1

Theme 4: Regular Case Staffing and Collaborative Consultations Facilitate SMHP Delivery

Another theme related to the PRISM construct implementation and sustainability infrastructure is case staffing. Case staffing and other collaborative consultations provide an opportunity for SMHP officers to seek guidance about challenging cases. Although not technically a core component of the SMHP model, case staffing and consultations were additional resources available to officers and chiefs to help them problem-solve and manage challenging supervision cases. Officers and supervisors reported conducting regularly scheduled (e.g., monthly) and ad hoc meetings to “staff cases” either between the officer and chief or with a licensed clinical social worker who was a member of the research team (Ghezzi et al. 2020). During these consultations, officers and chiefs discussed the wellbeing of individuals on their caseloads, including their behavioral health medication adherence and overall supervision compliance. For example, one officer responded:

Me and my chief will discuss the case, depending on if they’re compliant, versus noncompliant, or generally how the case is progressing… Having that resource and that level experience to help, I mean is invaluable too. That way you’re not second guessing yourself. You know what I’m saying? ‘Man, what if I made this next step?’, or ‘I should’ve went back and did that that way’. We have to come together as a team.—Officer 4

In addition, officers sought consultation from chiefs to reaffirm decisions about how to respond to instances of non-compliance, including the use of sanctions (e.g., jail time and other punitive sanctions), increased contacts, and other strategies. Officers were particularly concerned about how jail time or other punitive sanctions would affect individuals with mental illnesses, as illustrated by the following quote:

Chief is very supportive. She understands that it’s a different approach than with other probation cases. And she does a good job letting me know when to go from like the treatment side of things to the probation side of things, like when it becomes a public safety risk. She’s good at like, like sometimes I think the mental health officers get so focused on making sure they go to treatment that they may not realize that it’s time to take them back to court, it’s time to arrest them, something like that. So that can be really helpful.—Officer 2

Chiefs also reported that it was their responsibility to stay up-to-date on the status of individuals on the caseload and that the case staffing and consultation process helped them stay informed and made them better equipped to support the SMHP officers, particularly in regards to balancing a treatment orientation within a public safety approach. This is evidenced by the following quote from one of the chiefs in the program:

I think it’s really, really important for the supervisor to know every offender, just like if it was their offender they’re supervising, and what’s going on. Not only for officer safety, if there is a concern, but just to know what’s going on with the person, and if there’s something going on and the officer’s having a hard time. Well sometimes having to supervisor come in it helps a little bit. Because like I said, it’s a stressful caseload and there were times when [the officer] was just like, ‘I give up’…It definitely needs to be a supervisor who’s going to back their staff and back the decisions, but also know who the offenders are that they’re working with.—Chief 8

Another chief explained:

I think it helps me sometimes when if [my officer is] having a difficult decision on if we need to arrest this person, if they’re totally being not compliant, then I go ahead and make that decision for him, yes, we need to. This is a public safety issue, let’s go ahead and arrest. Or let’s go ahead and issue a violation and cite them in the court. So I’m the one that kind of makes sometimes that difficult decision to go ahead and proceed with something.—Chief 3

Theme 5: Open Communication and Collaboration with Community-Based Partners is Essential to Delivering SMHP

Lastly, in terms of elements related to the external environment in the PRISM model, officers and chiefs agreed that cultivating strong relationships with community-based treatment and social service agencies was essential to effectively deliver SMHP. Community treatment providers and resource organizations provided essential supports that individuals needed to be successful on probation. Officers described their need for open communication and collaboration with community-based partners as an essential interaction between resources in the external environment and the probation officer. Additionally, officers reported having productive relationships with community-based social workers, temporary employment agencies, the local residential housing authority, shelter, food banks, and the local Department of Child Services, and that these relationships helped individuals they supervised navigate challenges beyond probation, such as securing employment or addressing housing or child custody issues. For example, one officer stated:

Social services, child support, local law enforcement, private providers, whether it’s the Urban League, United Way, food banks, shelters. All of those community resources, every officer would contact, but they may contact it more because they’re trying to set up the holistic component with that particular person.—Chief 13

Open communication between the probation officer and community-based treatment or support agencies enabled officers to understand how individuals were progressing in treatment, and whether additional supports were needed. Officers and chiefs said they aimed to communicate with community partners daily or, at a minimum, weekly, to maintain productive, information-sharing relationships, as illustrated by the following:

I’m probably on the phone, if not every other day with somebody, pretty frequently… Mainly it’s mostly talking about, like I said, housing, medication, and making sure that person has that next appointment set up. If they missed the last one, even if they didn’t miss the last one, just making sure that person knows where to go, knows what time to go and how they’re going to get there. Last night I was working with a peer support specialist, and making sure that the person was able to get to her next appointment.—Officer 2

To build diverse, cross-agency relationships, officers reported investing a significant amount of time and effort to reach out to agencies and stay up-to-date on changes in service availability. One officer described the community engaged approach as a lot of “face-to-face, shaking hands, talking to them. Show them that I care and that I’m in the community, I’m part of the team” (Officer 9). Officers said their community-based partners were receptive to their frequent outreach because it was a mutually beneficial, “symbiotic relationship in that probation needs the information and [providers] need probation for the compliance” (Officer 14). Chiefs also described providers as willing partners to SMHP officers, as evidenced by the following:

So [treatment providers] were very much engaged. They were wanting to see this happen… I think they were wanting to see probation involved because they had so many offenders who are on probation. So they were definitely wanting to see this.—Chief 5

Officers reported employing a variety of approaches to building rapport and developing new relationships with community-based providers, including internet searches, cold calls and in-person visits, and relying on other officers’ networks. Occasionally new relationships were forged when providers or social support agencies attended probation staff meetings. The following quote from a chief probation officer illustrates how officers took initiative to reach out to agencies and establish connections:

[Officers are] constantly beating the bushes, going through weeds, just finding out, okay, ‘what new treatment providers are out here? What new service providers are out here? What this service provider does and what they don’t.’ So they have become masters in terms of trying to find the right … as I’ll say, the right outfit for an offender to wear… Our officers do a great job of networking, talking among themselves to try to find the best outfit to put on the offender.—Chief 4

Discussion

We qualitatively investigated the experiences of 16 SMHP officers and chiefs to describe the real-world experiences of operationalizing and delivering SMHP. Five key components emerged from the analysis: (1) meaningfully reduced caseload sizes; (2) officer ability to build rapport and individualize probation; (3) specialized training that is offered regularly; (4) regular case staffing and consultation; and (5) communication and collaboration with community-based providers.

These findings provide support for the elements of the SMHP model advanced by Skeem et al. (2006). In particular, our study results suggest that a reduced caseload is an important feature of the SMHP model. Participants described a common fear that the quality of their supervision and client compliance would deteriorate with each case added to their current caseload and suggested a cap of no more than 40 cases. In addition, an important element posited by Skeem et al. (2006) regarding exclusive mental health caseloads was not commented on by officers or chiefs who participated in the study. It is important to note that this was not asked about explicitly during our interviews and that most, if not all, of the officers who participated in the study had mixed caseloads. That is, the goal was to ensure the officers supervised caseloads comprised exclusively of individuals with mental illnesses but the officers were still in the process of building these caseloads during their participation in the study. Consequently, more research about mixed vs. exclusive mental health caseloads is needed to make a determination about caseload composition.

Our results also highlight the importance of ongoing mental health training that moves beyond basic knowledge of the signs and symptoms of mental illness and includes de-escalation and crisis intervention (e.g., CIT). In addition, results indicate that mental health case consultations may enhance the ability of officers to apply the skills learned and may serve as a critical resource for addressing complex challenges and balancing responses to mental illness while addressing public safety.

Participants also described the value of the collaborative relationships formed with treatment and social service providers in connecting individuals on their caseloads to necessary resources, which highlights the need for probation agencies to focus on building officer-service provider networks. Finally, our findings indicate the importance of selecting officers who demonstrate understanding and empathy, the ability to problem-solve and individualize supervision, and the capacity for balancing a mental health and public safety approach to supervision.

Limitations

Given state-by-state variation in probation, as well as differences in local service networks, results from this study pertaining to the external environment may not be applicable in other jurisdictions. In addition, this study represents a single model of SMHP and mental health approaches are known to vary by location. Consequently, results related to implementation infrastructure may not be generalizable. The most significant limitation of the study is the lack of perspectives of individuals on probation. Although individual level data are integrated into the effectiveness arm of this study, individuals on probation were not interviewed regarding SMHP implementation. Including the perspectives of those on probation would provide additional information about how the SMHP model was implemented. Despite these limitations, the findings from this study address a critical gap in the research by explicating core components of the model and describing the implementation infrastructure necessary for SMHP.

Implications

Ensure Infrastructure and Resources are in Place for Training and Consultation

Participants in the study noted the importance of establishing an infrastructure for supporting SMHP and providing ongoing training for officers and chiefs. In addition to the challenges related to supervising people with mental illnesses, officers and chiefs face multiple competing demands (e.g., additional training, paperwork, court, etc.). These demands create workload challenges that officers must balance and finding the time to schedule additional mental health trainings is challenging (Van Deinse et al. 2019). Consequently, officers and chiefs need protected time to fully engage in capacity building opportunities (e.g., training, networking with provider agencies) and to be able to spend more time in supervision to address the complex challenges of individuals with serious mental illnesses. Chief probation officers are essential to protecting SMHP officers’ time and implementing the model at the local level (including enforcing caseload limits, allowing for alternative sanctions, etc.). In their role as middle managers, chief probation officers who are welltrained and proactive will enhance model implementation (Birken et al. 2012).

Foster Collaboration with External Resources

Officer and chiefs described a high level of communication and collaboration with local resource providers in addressing the needs of individuals on their caseloads. Collaboration with local providers suggests that officers should have a diverse and responsive network of service providers. Agencies should consider developing implementation strategies to enhance officer networks and their knowledge about existing resources. For instance, during early implementation of the model, agencies could conduct a brief scan of the local resources and invite representatives from key agencies and organizations to a kickoff event. Such an event could provide opportunities for SMHP officers and chiefs to meet representatives, learn about their services, and exchange contact information.

In addition, some agencies could consider soliciting a key contact person from essential behavioral health organizations with which individuals on their caseloads are connected. This strategy may help to streamline contact with larger agencies. Agencies should consider the particular characteristics and composition of the local resource community as provider outreach and engagement may manifest differently in rural versus urban jurisdictions.

Further qualitative research on the relationship dynamics between probation officers and community-based treatment providers is needed to define drivers of successful collaborations. Prior research suggests treatment providers welcome open communication about client needs but are resistant to probation officers becoming too engaged in direct treatment provision. For example, a national survey of community-based providers’ overseeing treatment for sex offenders found that providers were comfortable having probation officers attend group meetings but did not want them involved in co-leading any treatment discussions (McGrath et al. 2002).

The Salience of Officer and Chief Characteristics

Officers and chiefs noted that SMHP officers’ ability to empathize, problem-solve, and individualize supervision approaches was essential to effectively implement SMHP. This finding indicates the need for a SMHP officer recruitment and selection process that identifies officers who are empathetic to the needs and challenges of individuals living with serious mental illnesses or substance use disorders. Successful SMHP officers may be those who can use professional judgment to effectively balance their compassion while enforcing the terms of supervision to address their primary aim of public safety.

Further, given the high importance officers and chiefs placed on developing collaborative relationships with community-based partners, like mental health or social service providers, SMHP officers must be good communicators who are able to develop and sustain new relationships with diverse community organizations. These ‘soft skills’ required for SMHP may have utility across justice-related efforts such as the Stepping Up Initiative (https://stepuptogether.org/) that calls on local leadership to reduce the number of people with mental illnesses in jail by identifying their individual needs and developing meaningful, collaborative relationships across systems.

To aid in the officer selection process, agencies may consider implementing a standardized instrument such as the Dual-Role Relationship Inventory Revised (DRI-R; Skeem et al. 2007a, b). The DRI-R is a 30-item instrument measuring officer relationships with probationers in three domains—trust, caring-fairness, and toughness. Scores on these scales—which can be obtained from self-assessment, probationer assessment of the officer, and chief assessment of the officer—could be used alongside other relevant factors in determining whether an officer is appropriate for SMHP.

Probation agencies should also consider how the chiefs that supervise the SMHP officers are selected. Officers and chiefs in this study indicated that chiefs helped officers discern when higher-level sanctions were needed, gave feedback about balancing public safety with behavioral health considerations, protected officers’ reduced caseload size, and provided general support. Consequently, agencies should consider recruiting chiefs with extensive probation experience and who are willing to attend additional training and to serve in this capacity.

Concerns for Sustainability

Future research is needed to examine how officers’ and chiefs’ needs for reduced caseloads and ongoing training are met by community corrections offices. Both of these factors were identified as critical to maintaining the quality of SMHP supervision. However, limited resources and a high volume of individuals requiring supervision may hinder community corrections’ ability to reduce caseload sizes and regularly guarantee protected time for staff to participate in ongoing trainings. Applied research methods should be used to determine how the interorganizational networks between community corrections offers and treatment providers may be used to sustain officers’ and chiefs’ ongoing training needs (e.g., motivational interviewing, crisis intervention) or even develop new case consultation models that support linkage between community corrections and community treatment providers. Hybrid effectiveness-implementation studies should evaluate agencies’ medium-term ability to maintain SMHP, as well as the long-term sustainability of this intervention in concert with important effectiveness outcomes such as recidivism and engagement in mental health treatment.

Implications for Implementation Research

Our study contributes to the emerging research literature that integrates implementation science frameworks and methods into behavioral health interventions in the juvenile and adult criminal justice systems. Notably, the Juvenile Justice Translational Research on Interventions for Adolescents in the Legal System (i.e., JJ-TRIALS; Becan et al. 2020; Belenko et al. 2017; Bowser et al. 2018; Knight et al. 2016) and the Criminal Justice Drug Abuse Treatment Studies (i.e., CJDATS; Friedmann et al. 2015; Monico et al. 2016; Welsh et al. 2016a, b) have integrated implementation science frameworks (e.g., Exploration, Preparation, Implementation and Sustainment [EPIS]; Aarons et al. 2011) and focused on service linkages between substance use service providers and juvenile and criminal justice entities. Our study expands on the implementation science research in criminal justice settings by examining the uptake of a specialized mental health approach within community corrections. In addition, to our knowledge, this is the first study to apply the PRISM model in a criminal justice context and our study demonstrates the model’s flexibility and responsiveness in this setting.

Better understanding the critical supports for effective implementation of interventions such as SMHP can guide the development and specification of implementation strategies that promote network connections between service sectors (e.g., criminal justice entities and community-based treatment providers). Additionally, these findings add to the implementation research on key infrastructure elements (e.g., ongoing training, network connections) necessary for adopting and sustaining cross-sectoral interventions. The findings presented here, particularly those indicating the salience of specific core components (e.g., reduced caseloads), can inform dissemination and expansion as well as future research and cost effectiveness studies.

Conclusion

SMHP is a transdisciplinary and complex intervention that spans the behavioral health and criminal justice systems. Our study suggests that previously identified core components, specifically reduced caseload sizes, participation in ongoing trainings and collaborative relationships with external partners are critical to delivering SMHP. Additionally, our results operationalized further aspects of SMHP delivery, including the need for SMHP officers to empathize and individualize supervision and engage in creative problem-solving, chiefs’ participation in trainings, case staffing and collaborative consultations. To enhance the implementation of SMHP, agencies should pay particular attention to their selection of SMHP officers and chiefs, establish internal infrastructure, and implement regular case staffing meetings and reviews of available external resources.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Stacey Burgin, Alex Lombardi, Alina Mason, and Reah Siegel for assistance with data collection and analysis.

Funding This qualitative study was funded by the Fahs Beck Fund for Research and Experimentation. The parent study was funded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance (2015-SM-BX-0004). In addition, the first and second authors are supported by the Lifespan/Brown Criminal Justice Research Training Program.

Footnotes

Data Availability The qualitative data generated and analyzed in this study are not publicly available because study participants voluntarily participated under the agreement that their data would be anonymized. Full interview transcripts, though de-identified, may still permit individuals to be identified due to the provision of other details including work place, years of service, and participation in specific training. Excerpts of qualitative data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, & Horwitz SM (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becan JE, Fisher JH, Johnson ID, Bartkowski JP, Seaver R, Gardner SK, et al. (2020). Improving substance use services for juvenile justice-involved youth: Complexity of process improvement plans in a large scale multi-site study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 10.1007/s10488-019-01007-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S, Knight D, Wasserman GA, Dennis ML, Wiley T, Taxman FS, et al. (2017). The juvenile justice behavioral health services cascade: A new framework for measuring unmet substance use treatment services needs among adolescent offenders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 74, 80–91. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birken SA, Lee SD, Weiner BJ, Chin MH, & Schaefer CT (2012). Improving the effectiveness of health care innovation implementation. Medical Care Research and Review, 70(1), 29–45. 10.1177/1077558712457427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowser D, Henry BF, Wasserman GA, Knight D, Gardner S, Krupka K, et al. (2018). Comparison of the overlap between juvenile justice processing and behavioral health screening, assessment and referral. Journal of Applied Juvenile Justice Services, 2018, 97–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton MT, Bahora M, Watson AC, & Oliva JR (2008). A comprehensive review of extant research on crisis intervention team (CIT) programs. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, 36(1), 47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council of State Governments. (2002). Criminal justice/mental health consensus project. New York: Council of State Governments. [Google Scholar]

- Crilly JF, Caine ED, Lamberti JS, Brown T, & Friedman B. (2009). Mental health services use and symptom prevalence in a cohort of adults on probation. Psychiatric Services, 60(4), 542–544. 10.1176/appi.ps.60.4.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pynt J, & Stetler C. (2012). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical Care, 50(3), 217–226. 10.1097/mlr.0b013e3182408812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditton P. (1999). Mental health and the treatment of inmates and probationers. U.S: Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Eno Louden J, & Skeem J. (2011). Parolees with mental disorder: Toward evidence-based practice. Bulletin of the Center for Evidence-Based Corrections, 7(1), 1–9. 10.1007/s10979-010-9223-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eno Louden J, Skeem JL, Camp J, & Christensen E. (2008). Supervising probationers with mental disorder: How do agencies respond to violations? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35(7), 832–847. [Google Scholar]

- Eno Louden J, Skeem JL, Camp J, Vidal S, & Peterson J. (2012). Supervision practices in specialty mental health probation: What happens in officer-probationer meetings? Law and Human Behavior, 36, 109–119. 10.1037/h0093961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein AC, & Glasgow RE (2008). A Practical, Robust, Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety., 34(4), 228–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Wilson D, Knudsen H, Ducharme L, Welsh W, Frisman L, et al. (2015). Effect of an organizational linkage intervention on staff perceptions of medication-assisted treatment and referral intentions in community corrections. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 50, 50–58. 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi M, Van Deinse TB, Crable EL, Cuddeback GS, Buck K, Brewer M, et al. (2020). Adapting a clinical case consultation model to enhance capacity of specialty mental health probation officers. Perspectives, 44(2), 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennealy PJ, Skeem JL, Manchak SM, & Eno Louden J. (2012). Firm, fair, and caring officer–offender relationships protect against supervision failure. Law and Human Behavior, 36, 496–505. 10.1037/h0093935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchener BA, & Jorm AF (2002). Mental health first aid training for the public: Evaluation of effects on knowledge, attitudes and helping behavior. BMC Psychiatry, 2(1), 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchener BA, & Jorm AF (2006). Mental health first aid training: review of evaluation studies. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(1), 6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight DK, Belenko S, Wiley T, Robertson AA, Arrigona N, Dennis M, et al. (2016). Juvenile Justice—Translational research on interventions for adolescents in the legal system (JJ-TRIALS): A cluster randomized trial targeting system-wide improvement in substance use services. Implementation Science, 11, 57. 10.1186/s13012-016-0423-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchak SM, Skeem JL, Kennealy PJ, & Eno Louden J. (2014). High-fidelity specialty mental health probation improves officer practices, treatment access, and rule compliance. Law and Human Behavior, 38(5), 450. 10.1037/lhb0000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Carroll K, Kostas D, Perkins J, & Rounsaville B. (2002). Dual diagnosis motivational interviewing: A modification of motivational interviewing for substance-abusing patients with psychotic disorders. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 23(4), 297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath RJ, Cumming G, & Holt J. (2002). Collaboration among sex offender treatment providers and probation and parole officers: The beliefs and behaviors of treatment providers. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 14(1), 49–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monico LB, Mitchell SG, Welsh W, Link N, Hamilton L, Redden SM, et al. (2016). Developing effective interorganizational relationships between community corrections and community treatment providers. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 55(7), 484–501. 10.1080/10509674.2016.1218401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, & Cook DA (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porporino FJ, & Motiuk LL (1995). The prison careers of mentally disordered offenders. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 18(1), 29–44. 10.1016/0160-2527(94)00025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018). NVivo qualitative data analysis software, Version 12. [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, Emke-Francis P, & Eno Louden J. (2006). Probation, mental health, and mandated treatment a national survey. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 33(2), 158–184. 10.1177/0093854805284420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, & Eno Louden J. (2006). Toward evidence-based practice for probationers and parolees mandated to mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services, 57(3), 333–342. 10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, Manchak S, & Montoya L. (2017). Comparing public safety outcomes for traditional probation vs specialty mental health probation. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(9), 942–948. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, Eno Louden J, Polaschek D, & Camp J. (2007a). Assessing relationship quality in mandated community treatment: Blending care with control. Psychological Assessment, 19, 397–410. 10.1037/1040-3590.19.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem J, Eno Louden J, Polasheck D, & Camp J. (2007b). Assessing relationship quality in mandated community treatment: Blending care with control. Psychological Assessment, 19(4), 397–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, & Petrila J. (2004). Problem-solving supervision: Specialty probation for individuals with mental illness. Court Review, 40, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman HJ (1992). Boundary spanners: A key component for the effective interactions of the justice and mental health systems. Law and Human Behavior, 16, 75–87. 10.1007/BF02351050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deinse TB, Bunger A, Burgin S, Wilson AB, & Cuddeback GS (2019). Using the consolidated framework for implementation research to examine implementation determinants of specialty mental health probation. Health and Justice, 7(1), 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deinse TB, Cuddeback GS, Wilson AB, & Burgin SE (2017). Probation officers’ perceptions of supervising probationers with mental illness in rural and urban settings. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 43(2), 267–277. 10.1007/s12103-017-9392-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deinse TB, Cuddeback GS, Wilson AB, Lambert M, & Edwards D. (2018). Using statewide administrative data and brief mental health screening to estimate the prevalence of mental illness among probationers. Probation Journal, 66(2), 236–247. 10.1177/0264550518808369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh WN, Knudsen HK, Knight K, Ducharme L, Pankow J, Urbine T, et al. (2016a). Effects of an organizational linkage intervention on inter-organizational service coordination between probation/parole agencies and community treatment providers. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43, 105–121. 10.1007/s10488-014-0623-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh WN, Prendergast M, Knight K, Knudsen H, Monico L, Gray J, et al. (2016b). Correlates of interorganizational service coordination in community corrections. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(4), 483–505. 10.1177/0093854815607306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff N, Epperson M, Shi J, Huening J, Schumann BE, & Sullivan IR (2014). Mental health specialized probation caseloads: Are they effective? International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 37, 464–472. 10.1016/j.ijlp.2014.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]