Abstract

Rationale and Objectives:

Periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) in the elderly have been reported with distinctive roles in the progression of cognitive decline and dementia. However, the definition of these two subregions of WMHs is arbitrary and varies across studies. Here, we evaluate three partition methods for WMH subregions, including two widely used conventional methods (CV & D10) and one novel method based on bilateral distance (BD).

Materials and Methods:

The three partition methods were assessed on the MRI scans of 60 subjects, with 20 normal control, 20 mild cognitive impairment, and 20 Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Resulting WMH subregional volumes were (1) compared among different partition methods and subject groups, and (2) tested for clinical associations with cognition and dementia. Inter-rater, intrarater, and interscan reproducibility of WMHs volumes were tested on 12 randomly selected subjects from the 60.

Results:

For all three partition methods, increased periventricular WMHs were found for AD subjects over normal control. For BD and D10, but not CV method, increased Periventricular WMHs were found for AD subjects over mild cognitive impairment. Significant correlations were found between PVWMHs and Mini-Mental State Examination, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, and Clinical Dementia Rating scores. Furthermore, PVWMHs under BD partition showed higher correlations than D10 and CV. High intrarater and interscan reproducibility (ICCA = 0.998 and 0.992 correspondingly) and substantial inter-rater reproducibility (ICCA = 0.886) were detected.

Conclusion:

Different WMH partition methods showed comparable diagnostic abilities. The proposed BD method showed advantages in quantifying PVWMH over conventional CV and D10 methods, in terms of higher consistency, larger contrast, and higher diagnosis accuracy. Furthermore, the PVWMH under BD partition showed stronger clinical correlations than conventional methods.

Keywords: Image segmentation, White matter hyperintensities, Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, Alzheimer’s disease, Mild cognitive impairment

INTRODUCTION

White matter hyperintensities (WMHs), also known as leukoaraiosis (1), are readily visualized as areas of high signal intensity on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI scans. The origin and pathophysiology of WMHs are not fully understood. Prior studies proposed that WMHs reflect increased tissue water content, demyelination, and axonal damage due to small vessel disease or ischemic changes (2-4). WMHs can be partitioned into periventricular (PVWMH) and deep (DWMH) subregions, based on their localization with respect to lateral ventricles (5). There is clinical justification of this division, rooted in a number of studies that demonstrated PVWMH and DWMH have different functional, histopathological, and etiological features (3,6). Pathologically, PVWMH is characterized by its unique location and by its histopathological features such as gliosis, loosening of the WM fibers, and myelin loss around tortuous vessels in perivascular spaces (7-9). PVWMHs appear to be linked to the disrupted ependymal cell membrane that lines the ventricles. Ependymal cells along the ventricle walls play an important role as an immunological barrier and in the production and regulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (10). Their inner surfaces are covered in a layer of cilia that help CSF circulation. Ependyma is covered with microvilli, which absorb CSF. The lesions arising from the ependymal membrane (ie, PVWMHs) are often seen on FLAIR MRI in the elderly. These chronic PVWMH pathologies, which are most likely due to small vessel disease, may result in increased blood-brain barrier, blood products leakage, as well as disturbance in interstitial fluid circulation or drainage of fluid (11). While DWMHs shared PVWMHs’ association with demyelination and gliosis, they tend to be away from ventricle surface and linked to vacuolation and tissue loss due to ischemic changes (8). The emerging pathological differences of PVWMH and DWMH suggest differential clinical associations for normal aging, cognitive decline, and dementia. PVWMHs (but not DWMHs) were reported to associate with decline or impairment in cognitive function (3,12,13), mental processing speed (14) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score (15). Increased volume or higher severity of PWMHs were found in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia (16-18), AD with hypertension (19), increased risk of progression from amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to AD (20,21); while DWMHs were common in depressed patients (16) and had only weak association with dementia (17,21). It is worth mentioning that localization of WMHs in parietal lobe (rather than ventricular adjacency), was reported to strongly associate with cognitive impairment (22) and AD (23,24).

Despite of the distinctive clinical associations of PVWMH and DWMH, their partition methods vary a great deal across studies. There is yet no universally accepted definition of PVWMH and DWMH (1,25,26). One common quantitative definition specifies that PVWMH voxels lie within a distance d (Dmin < d < Dmax) to lateral ventricle (5,27,28). Values of Dmin = 0, Dmax =10 mm (25) or 3-13 mm (3) are most widely used (29). Another common definition is the “continuity to ventricle,” which requires PVWMH voxels to be mutually connected structure that is adjacent to the wall of lateral ventricles (5,14). These two commonly used WMH partition methods have several limitations. First, the distance to ventricle is usually measured on 2D slices instead of in 3D volumes. Second, the output scores of empirical rating are discrete, making it less sensitive to small changes of WMHs. Finally, these methods only consider continuity or distance to ventricles (unilateral).

In this study, we propose a novel partition method that accounts for 3D distances to both ventricles and cerebral cortical cortex (ie, bilateral distances). For each image, the method provides at least two quantitative values of WMHs: the volume of PVWMH and of DWMH. This scheme can then be refined using lobar (frontal, temporal, parietal, occipital) brain partitioning. We evaluated the PVWMH and DWMH extracted from FLAIR MRI under different partition methods, including the proposed bilateral distance method. The outcome measure was the ability of each method to distinguish between three groups of elderly: healthy aging, mild impairment, and Alzheimer’s dementia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and MRI Data Acquisition

MRI data of 60 subjects were downloaded from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative database (ADNI). We first randomly selected 20 subjects from AD group, as this group has least available subjects on ADNI. We then selected 20 subjects from normal control (NC) group, and 20 from MCI, so that the three groups are age- and gender-matched (Table 1). Our selection was otherwise random, but constrained to assure that there is no significant difference of age or gender among the groups. The ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial MRI, PET, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD. Multisite ADNI imaging study was approved by participating institutional review boards. All subjects signed an informed consent form. For up-to-date information, see www.adni-info.org.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Subjects

| Group | NC | MCI | AD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Age | 74.25 ± 7.13 | 74.75 ± 7.89 | 75.75 ± 7.21 |

| Female % | 50% | 50% | 50% |

MRI Protocol

All subjects underwent whole-brain 3T MRI scans, including anatomical 3D T1-weighted (T1W) MPRAGE (30) and 2D axial FLAIR (spin echo inversion recovery sequence designed for optimal WML detection, 5 mm slice thickness, 256 × 256 matrix, TR = 11,000 ms, TE = 147 ms). One exam was retrieved for each of 60 subjects. For reproducibility test (see Statistical Analysis section), 12 additional FLAIR scans were retrieved for 12 randomly selected subjects from the 60 (each additional scan each).

Image Processing

WMHs were segmented on FLAIR images with FireVoxel (build 301, https://wp.nyu.edu/firevoxel). In short, the algorithm starts with uniformity correction (N3 (31)), followed by the estimation of the signal intensity within an image-dependent whole-brain mask W. The WHMs were then segmented by thresholding from W all voxels v such as M’ = {v∣s(v)>μ+kσ}, where μ is the mean value and σ the standard deviation (STD) of intensity distribution in W, and k was set at 2.5 (32). The aim of the final step is to delete from M’ the septum and chorid plexus. These structures were identified as connected components of M’ having >50% surface boundary adjacent to CSF. The resulting WMHs masks M were quality-controlled by trained observers blind to the group membership of subjects. Independently, binary masks of WM, lateral ventricles and cerebral cortex were segmented on T1W scans with Freesurfer (v6.0 https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). T1W image was co-registered to FLAIR using the rigid-body module and mutual information measure in FSL (v6.0 https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk). Distance maps for lateral ventricles and for cerebral cortex were generated on FLAIR space with FSL. Finally, the masks M were partitioned as PVWMHs and DWMHs using three methods (Fig. 1) separately:

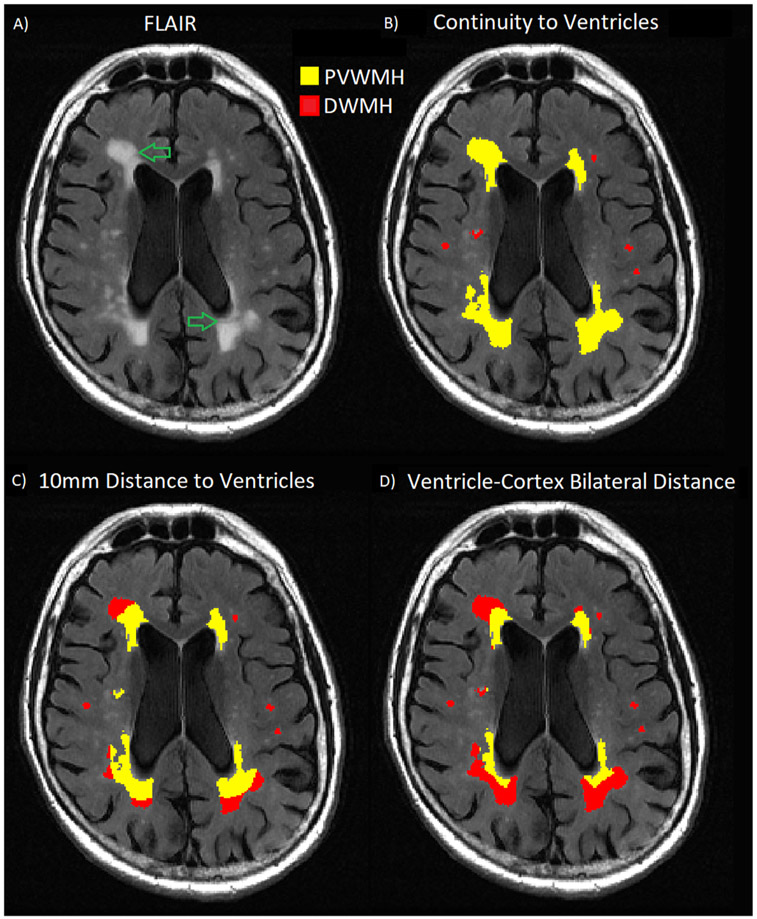

Fig. 1.

Illustration of three definitions of PVWMH (yellow) and DWMH (red). A) is one slice from a typical FLAIR image. B), C), and D) are classifications obtained using CV, D10 and BD methods correspondingly. Note the large difference in PVWMH and DWMH defined by the three methods. The green arrows in A) point out the subtle gaps within WMH cluster. The gaps are best matched by the PVWMH/DWMH boundary under BD partition.

Continuity of ventricle (CV) method partitions WMH mask into connected components (blobs), then labels entire blob as PVWMH if it contains voxels adjacent to ventricle walls (5,33).

10 mm distance to ventricle (D10) method classifies individual WMH voxels located within 10 mm to ventricle walls as PVWMHs. Voxels that are farther than 10 mm form DWMHs (25).

Bilateral distance (BD) method computes for each WMH voxel the distance to ventricle and to cortex, and classifies the voxel as PVWMH if it is closer to ventricle than to cortex, otherwise as DWMH.

Our Matlab implementation of CV, D10, and BD partition methods is available online (https://github.com/jingyunc/wmhs).

To plot the spatial distribution of WMHs within disease group, the T1 images were warped to MNI152 template with SPM normalization module. The computed transformations were applied to the binary WMHs masks that were already co-registered to the corresponding T1. Nearest-neighbor interpolation was used to avoid producing nonbinary masks. Finally, the normalized WMHs masks were averaged within NC, MCI, and AD groups. Each voxel of the group-averaged masks has the intensity (floating point/decimal) value between 0.00 and 1.0, representing the percentage of subjects with (ie, probability of) WMHs showing that particular voxel.

Clinical Data

The following clinical data were downloaded from ADNI database: Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR), MMSE, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). The clinical data were then matched to the image data using subject ID. When multiple clinical exams were found for the same subject, the data with closest exam date to the imaging date were selected.

Statistical Analyses

The automated WMHs segmentation was quality-controlled and (if necessary) manually corrected by two different human raters (HY & MG). We conducted reproducibility tests for resulting WMH volumes: A) between the two raters, and B) within the same rater. For A), the two raters worked on the same 12 subjects (randomly picked from the 60-subject pool). For B), one rater (HY) processed twice on the same 12 FLAIR scans (randomly picked from the 60-subject pool). To minimize memory recall bias, the second processing session took place more than two weeks after the first time. Furthermore, to examine the robustness of partition methods, we conducted reproducibility test C) between two scans of same subject with little WMHs change. For C), one rater (HY) processed 12 subjects (randomly picked from the 60-subject pool), each with two FLAIR scans less than 10 months from each other. Partition of WMH into PVWMH and DWMH is fully automatic, thus there is no observer-induced change in C). For all pairs of total or subregional WMH volumes collected from tests A), B), and C), the intraclass correlation coefficient (absolute difference version of agreement, ICCA) (34) was computed.

To examine the diagnostic ability of WMH subregions under different partition methods, we compared the subregional WMH volumes among different subject groups (NC, MCI, and AD) by their mean, STD, and coefficient of variance (defined as CoV = STD/mean). To remove confounding factors from brain size and atrophy, PVWMH and DWMH volumes were normalized by dividing over the WM volumes of the same subject. We conducted independent-samples Mann-Whitney U tests on the WMH subregions for NC vs MCI, MCI vs AD, and NC vs AD. Between-group effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were also computed. We then generated the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the classification of above three group pairs with WMH subregions, and the corresponding area under curve (AUC).

To validate the differential clinical associations of PVWMH and DWMH with cognition and dementia, we computed the Pearson correlation coefficients and p values between WMH subregions (both raw and normalized) and the MMSE, MoCA, and CDR (total and subscores). We also tested the correlation between regional WMHs and cortical atrophy as an indicator of neurodegeneration. We collected the mean cortical thickness and cortical volume data from the same Freesurfer processing described in Section 2.3. All volumes were controlled for head size by dividing over the estimated total intracranial volume (eTIV). Since the tested correlations are hypothesized by previous studies (refer to Introduction) rather than blind search, no correction for multiple comparisons was necessary. To assure statistical power, correlations were computed for the entire cohort.

Finally, we performed pairwise t tests on WMH subregions between different partition methods. The subregional volumes were log-transformed to meet the normality requirement. Bonferroni correction was applied to account for multiple comparisons.

The mean, STD, CoV, ICCA, and correlation tests were computed in Matlab (R2018a). The Mann-Whitney U tests, ROC curves, and AUC values were carried out with IBM SPSS Statistics (v25).

RESULTS

Group Differences and Diagnostic Power

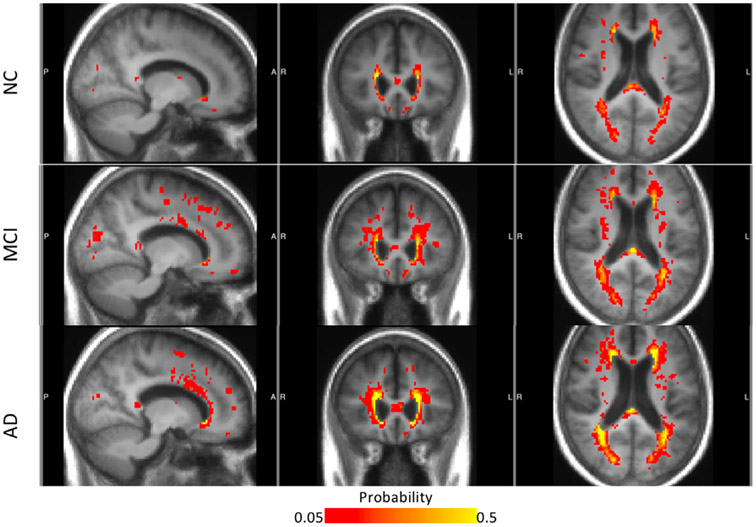

Figure 2 illustrates the spatial distribution of total WMHs (probability map) for each disease group. Increased territory of WMHs was observed as disease progresses from NC to MCI, and to AD. Furthermore, the spatial patterns radiate concentrically from the ventricular walls into the surrounding WM (red and yellow in Fig 2). In contrast, there was no consistent accumulation of probabilities of DWMHs, suggesting scatter and heterogeneity across subjects.

Fig. 2.

Probability maps of WMHs for NC, MCI, and AD groups, with the background of averaged MRI from each group. The color map presents the percentage of subjects with (ie, probability of) WMHs at a particular location. WMH probability less than 0.05 is not shown, whereas probability higher than 0.5 are all colored in yellow.

The PVWMH and DWMH volumes are shown in Table 2. Under all partition methods, AD group has the largest mean PVWMH and DWMH volumes, followed by MCI group and lastly NC group. The only exception is DWMH volumes under CV partition. The group difference results of PVWMHs are shown in Table 3. The NC-AD group differences were found statistically significant for all partition methods, while the NC-MCI difference were found nonsignificant, also for all partition methods. Interestingly, the MCI-AD difference were statistically significant under BD and D10 methods, but not under CV. This suggests the superior sensitivity of BD and D10 methods in discriminating MCI and AD over CV method (Table 3). No significant group difference was found on DWMH under any partition methods.

TABLE 2.

Normalized WMH Subregional Volumes in Three Subject Groups (Mean ± Standard Deviation)

| Group | PVWMH |

DWMH |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV | D10 | BD | CV | D10 | BD | |

| NC | 0.018 ± 0.036 | 0.014 ± 0.022 | 0.010 ± 0.013 | 0.003 ± 0.003 | 0.007 ± 0.015 | 0.011 ± 0.024 |

| MCI | 0.020 ± 0.022 | 0.016 ± 0.015 | 0.012 ± 0.010 | 0.004 ± 0.005 | 0.008 ± 0.009 | 0.013 ± 0.014 |

| AD | 0.032 ± 0.024 | 0.027 ± 0.018 | 0.020 ± 0.012 | 0.003 ± 0.002 | 0.008 ± 0.007 | 0.016 ± 0.013 |

TABLE 3.

p Values of Group Difference Tests on PVWMH

| CV | D10 | BD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NC vs MCI | - | - | - |

| MCI vs AD | - | 0.042 | 0.014 |

| NC vs AD | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Only significant p values (p < 0.05) were displayed.

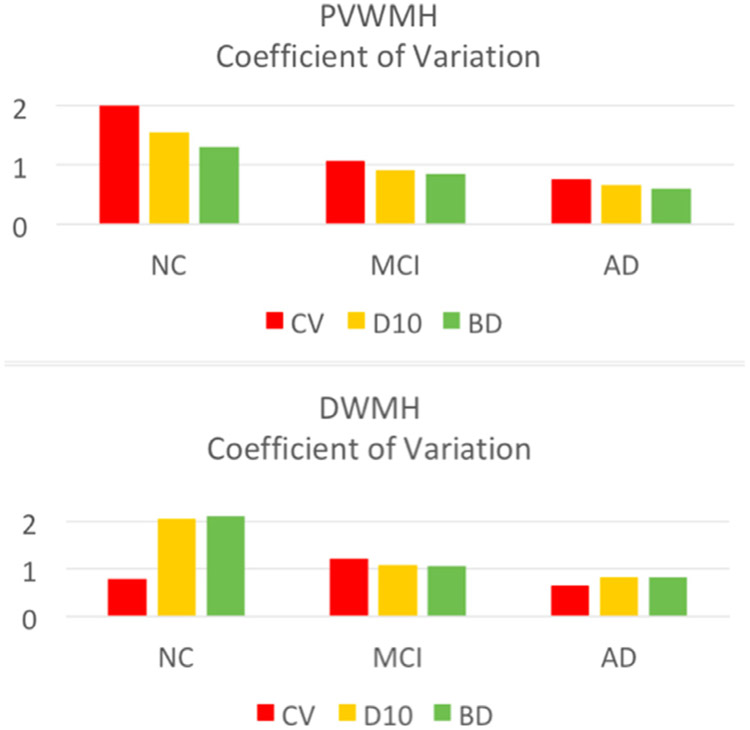

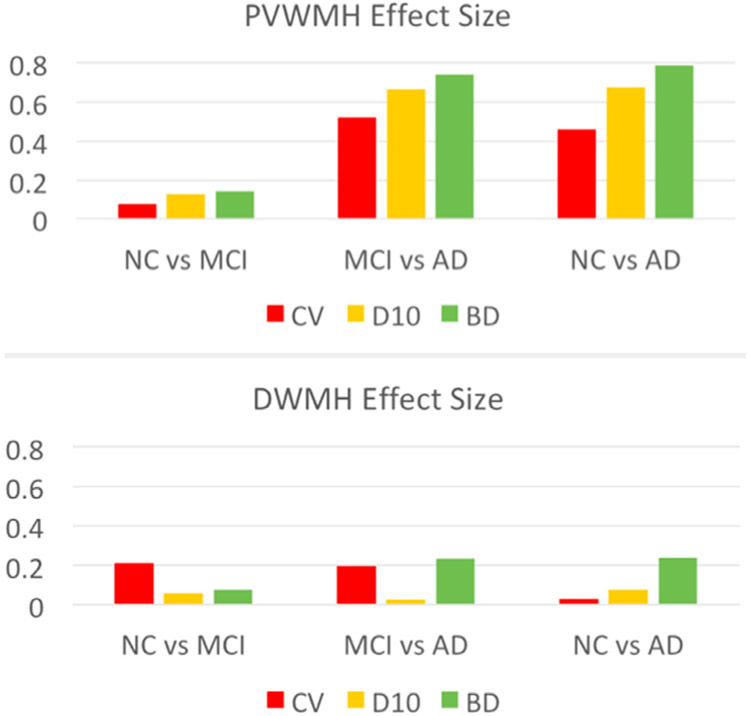

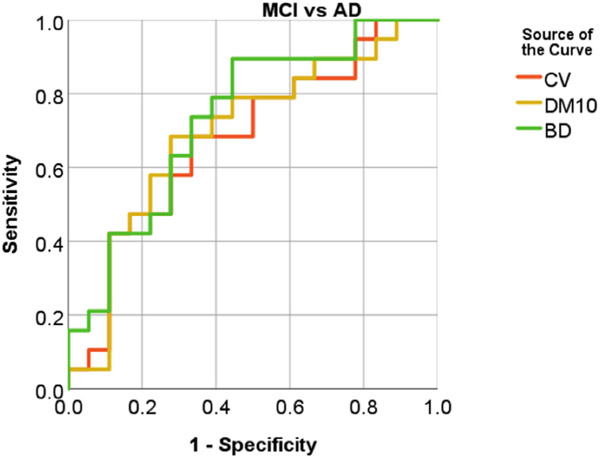

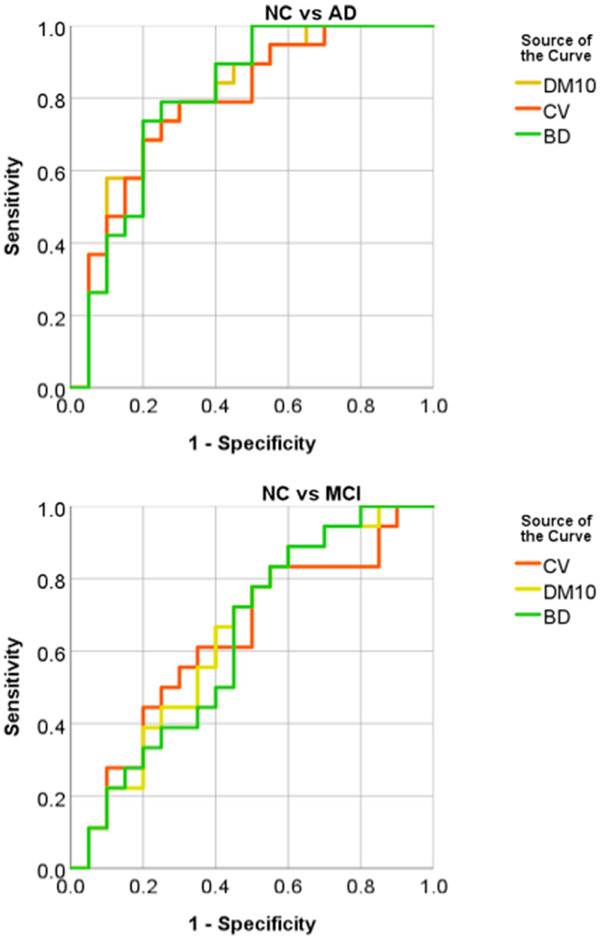

The within-group CoV of PVWMH and DWMH volumes are shown in Figure 3, and the between-group effect sizes (Cohen’s d) in Figure 4. From Figure 3, the NC group showed largest CoV (>1), followed by the MCI group. The AD group had smallest CoV (<1) in three groups. Among the three partition methods, PVWMH under BD partition consistently had smaller CoV than D10 and CV, indicating lower within-group variation. From Figure 4, the effect sizes of NC-AD and MCI-AD are larger than NC-MCI, which is consistent with the group difference test results (Table 3). Again, PVWMH under BD partition consistently shows larger effect sizes than D10 and CV, indicating larger diagnostic power. Finally, the ROC curve of MCI-AD classification with PVWMH (Fig 5) demonstrates that BD partition yields higher classification accuracy (AUC = 0.734) than both D10 (AUC = 0.696) and CV (AUC = 0.678). Similar advantage for BD method for NC-AD and NC-MCI classification are shown in supplemental results (Fig A1, Table A3).

Fig. 3.

Coefficients of variation (defined as standard deviation over mean) for DWMH and PVWMH under different partition methods: CV (orange), D10 (yellow), and BD (green). The variability under BD partition is smallest, indicating higher intragroup consistency for BD method.

Fig. 4.

Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) of PVWMH and DWMH under different partition methods: CV (orange), D10 (yellow), and BD (green). Across all group pairs (NC vs MCI, MCI vs AD, and NC vs AD), BD partition shows less variation than the other two methods, indicating higher intergroup contrast for BD method.

Fig. 5.

ROC curves of MCI vs AD classification with PVWMH. The PVWMH from BD partition (green) shows higher area under curve (AUC) than CV (red) and D10 (yellow) partition methods, indicating higher diagnosis power.

Clinical Correlation Tests

The significant correlations are showed in Table 4. Correlations were computed for the entire cohort (three outliers were excluded from correlation tests due to missing data, resulting in N = 57). PVWMH, but not DWMH, was found significantly correlated with subscores of MoCa, MMSE, and CDR, and with total scores of MMSE and CDR. In all detected associations, the PVWMH under novel BD partition consistently showed stronger correlations than D10 and CV methods. For example, PVWMH showed significant correlation with global CDR scores only under BD partition, but not under D10 or CV.

TABLE 4.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients Between PVWMH and Clinical Assessments

| CV |

D10 |

BD |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVWMH Volume | PVWMH Ratio | PVWMH Volume | PVWMH Ratio | PVWMH Volume | PVWMH Ratio | ||

| MoCA | CUBE | −0.266 | −0.271 | −0.296 | |||

| ABSTRAN | −0.274 | −0.267 | −0.326 | −0.316 | −0.337 | −0.329 | |

| MMSE | MMBALLDL | 0.284 | 0.283 | 0.345 | 0.340 | 0.384 | 0.379 |

| MMFLAGDL | 0.274 | 0.274 | |||||

| MMTREEDL | 0.348 | 0.339 | 0.400 | 0.389 | |||

| MMDRAW | 0.271 | ||||||

| MMSCORE | −0.295 | −0.317 | −0.426 | −0.454 | |||

| CDR | CDMEMORY | 0.277 | 0.335 | 0.360 | 0.356 | 0.386 | |

| CDORIENT | 0.330 | 0.354 | |||||

| CDCOMMUN | 0.267 | ||||||

| CDHOME | 0.283 | ||||||

| CDCARE | 0.275 | ||||||

| CDGLOBAL | 0.293 | 0.321 | |||||

MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; CUBE, Copy Cube. ABSTRAN, Abstraction Train-bicycle. MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MMBALLDL, Ball/Apple; MMFLAFDL, Flag/Penny; MMTREEDL, Tree/Table; MMDRAW, Present the participant with Construction Stimulus page and say “Copy this design.” MMSCORE, Total Score. CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale; CDNEMORY, Memory Score; CDORIENT, Orientation Score; CDCOMMUN, Community Affaires Score; CDHOME, Home and Hobbies Score; CDCARE, Personal Care Score; CDGLOBAL, Global Score.

Only significant correlations (p < 0.05) are shown. Note BD revealed 22 clinical correlations compared to only 7 for CV and 9 for D10.

The Pearson correlation coefficients between regional WMHs and cortical atrophy are showed in Appendix Table A4. PVWMHs were found significantly correlated with cortical atrophy, that is, negatively correlated with cortical thickness and volumes. In comparison, DWMHs were found less correlated with cortical atrophy. Significant correlations were only found under BD partition, with cortical volumes. These results suggested PVWMHs are more correlated with AD-like neurodegeneration than DWMHs, which is consistent with previous findings from both crosssectional (35) and longitudinal studies (36).

Reproducibility Tests

For the total WMH volumes, the raters showed high agreement with self (intrarater ICCA = 0.998), and substantial agreement with each other (inter-rater ICCA = 0.886); high interscan agreement (ICCA = 0.992) was also observed, consistent with the previous report on FLAIR (37).

The PVWMH and DWMH volumes under different partition methods generally showed high interscan robustness (ICCA ≥ 0.990), except for DWMH under CV method (ICCA = 0.778). This suggests the D10 and BD methods are robust on measuring PVWMH and DWMH volumes, while CV method showed robustness only on PVWMH, but not DWMH. Full data of interscan ICCA are shown in Appendices (Table A1).

PVWMH and DWMH Volumes Are Affected by Different Partition Methods

The p values of pairwise t test between partition methods are showed in supplemental Table A2. A p value threshold 0.028 was applied with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. In all three groups (NC, MCI, and AD), significant or trending differences in mean PVWMH and DWMH volumes for BD method and other two partition methods, while no significant difference was found between D10 and CV methods. Note the nonsignificant difference between D10 and CV results does not suggest equivalency between the two methods (as showed otherwise in Fig 1), but rather only suggests that the volumes from one method are not consistently larger (or smaller) than the other.

DISCUSSION

There has been some controversy concerning the medical rationale of distinguishing periventricular from deep white lesions. Although certain studies argued that periventricular and deep WMHs are different stages of continuous pathology and should be regarded as one tissue type (38,39), there is a strong clinical and imaging evidence for different origin. The pathological differences of PVWMH and DWMH suggest differential clinical associations, which have been confirmed by numerous studies (Table 4). On FLAIR scans, gaps between PVWMHs and DWMHs can often be observed (see green arrows in Fig 1). The separate quantification of PVWMHs and DWMHs is also consistent with the conventional Fazekas grading system, which independently rates the severity of these two WMH subregions (5).

In this paper, we evaluated three partition methods for white matter lesions representative of age- and gender-matched NC, MCI, and AD groups. Compared to conventional partition methods CV and D10, the novel BD method appeared to better delineate the spatial extent of hyperintensity clusters on FLAIR (see green arrows in Fig 1). BD method also showed several advantages in terms of diagnostic performance (Fig 4), within-group consistency (CoV), between-group contrast (effect size), and classification accuracy (AUC of ROC).

The partition methods are based on binary mask of total WMHs, and therefore are not sensitive to the subtle change of FLAIR signal within the masks. The WMH masks were obtained through semiautomatic computer program after manual correction. Substantial agreement was observed for the manual correction work of human raters. However, occasional disagreement could still be observed between raters. Fully automated WMHs segmentation can help reduce the variation in manual correction. To our knowledge, no existing WMHs automatic segmentation method can achieve clinically acceptable accuracy without at least a minimal manual supervision (1). However, with the advance of big data and machine learning technology, future segmentation systems may eliminate the need for manual correction.

The automated partition of WMHs also depends on the accurate segmentation of lateral ventricles (for CV, D10, and BD methods) and cerebral cortex (for BD method only). While this segmentation can be robustly conducted by several open-source software (eg, the Freesurfer used in this paper), it is not a routine practice of clinical neuroimaging. Therefore, the automated partition methods are not easily translated into clinical practice.

The significant clinical correlations we found for PVWMH (Table 4) is consistent with converging previous studies on the PVWMHs associations with cognitive decline (3,12-15), and with dementia (16-21). However, the DWMHs associations with depression (16) were not reproduced from our correlation test. A possible explanation is the heterogeneity of DMWHs distribution among the subjects, which can be observed from Figure 2.

CONCLUSION

Robust quantification of PVWMHs can potentially improve the early diagnosis of MCI and AD. The proposed BD method showed advantages in quantifying PVWMH over conventional CV and D10 methods: higher consistency, larger contrast, and better accuracy. Furthermore, the PVWMH under BD partition showed stronger correlations with subjects’ cognition and dementia status (assessed by MoCA, MMSE, and CDR scores). These results suggest that the automatically computed BD partition is the method of choice in classifying WMHs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by National Institute of Health (RF1 NS110041, U24 EB028980, R56 AG060822, R01 EB025133, and R01 EB025133-S2). This study is also partially supported by Alzheimer’s Disease Association (grant numbers AARG-17-533484, P30 AG008051). This work was performed under the rubric of the Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research (CAI2R, www.cai2r.net) and NIBIB Biomedical Technology Resource Center (P41 EB017183).

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer's Association; Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer's Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

APPENDICES

TABLE A1.

Interscan ICCA for WMH Subregions Under Different Partition Methods

| D10 | CV | BD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DWMH | 0.991 | 0.778 | 0.994 |

| PVWMH | 0.990 | 0.990 | 0.995 |

TABLE A2.

p Values of Pair-Wise Difference Tests Between WMH Partition Methods

| Group | NC | MCI | AD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVWMH | BD vs D10 | 0.000 | 0.004* | 0.000 |

| BD vs CV | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| D10 vs CV | - | - | - | |

| DWMH | BD vs D10 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| BD vs CV | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| D10 vs CV | - | - | - |

Only significant or trending p values were displayed.

Trending.

TABLE A3.

AUC of ROC Curves for PVWMHs

| CV | D10 | BD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NC vs MCI | 0.636 | 0.650 | 0.653 |

| MCI vs AD | 0.678 | 0.696 | 0.734 |

| NC vs AD | 0.797 | 0.787 | 0.803 |

TABLE A4.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients Between Regional WMHs and Cortical Atrophy

| CV |

D10 |

BD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVWMH Volume | PVWMH Ratio | PVWMH Volume | PVWMH Ratio | PVWMH Volume | PVWMH Ratio | |

| Cortical Thickness | −0.269 | −0.290 | −0.306 | −0.329 | ||

| Cortical Volume | −0.371 | −0.391 | −0.452 | −0.469 | −0.482 | −0.500 |

| CV |

D10 |

BD |

||||

| DWMH Volume | DWMH Ratio | DWMH Volume | DWMH Ratio | DWMH Volume | DWMH Ratio | |

| Cortical Thickness | ||||||

| Cortical Volume | −0.249 | −0.272 | ||||

Only significant correlations (p < 0.05) are shown. PVWMHs under different partition methods consistently showed significant correlations with cortical atrophy (expect for CV partition with cortical thickness). In comparison, DWMHs were found less correlated with cortical atrophy.

Fig. A1.

ROC curves for NC vs AD (upper), and NC vs MCI (bottom) classification with PVWMHs from three difference partition methods CV (red), DM10 (yellow), and BD (green).

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: None.

Contributor Information

Jingyun Chen, Department of Neurology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, 145 E 32 St Rm 514, New York, NY 10016; Department of Radiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY.

Artem V. Mikheev, Department of Radiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY.

Han Yu, Department of Neurology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, 145 E 32 St Rm 514, New York, NY 10016; Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY.

Matthew D. Gruen, Department of Physics, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

Henry Rusinek, Department of Radiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY.

Yulin Ge, Department of Radiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wardlaw JM, Valdes Hernandez MC, et al. What are white matter hyperintensities made of? Relevance to vascular cognitive impairment. J Am Heart Assoc 2015; 4:001140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alber J, Alladi S, Bae HJ, et al. White matter hyperintensities in vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID): knowledge gaps and opportunities. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2019; 5:107–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim KW, MacFall JR, Payne ME. Classification of white matter lesions on magnetic resonance imaging in elderly persons. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 64:273–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fazekas F, Schmidt R, Scheltens P. Pathophysiologic mechanisms in the development of age-related white matter changes of the brain. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1998(9 Suppl 1):2–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, et al. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer's dementia and normal aging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1987; 149:351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010; 341:c3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black S, Gao F, Bilbao J. Understanding white matter disease: imaging-pathological correlations in vascular cognitive impairment. Stroke 2009; 40(3 Suppl):S48–S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gouw AA, Seewann A, van der Flier WM, et al. Heterogeneity of small vessel disease: a systematic review of MRI and histopathology correlations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011; 82:126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moody DM, Brown WR, Challa VR, et al. Periventricular venous collagenosis: association with leukoaraiosis. Radiology 1995; 194:469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiménez AJ, Domínguez-Pinos M, Guerra MM, et al. Structure and function of the ependymal barrier and diseases associated with ependyma disruption. Tissue barriers 2014; 2. e28426–e28426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weller RO, Djuanda E, Yow H, et al. Lymphatic drainage of the brain and the pathophysiology of neurological disease. Acta Neuropathol 2009; 117:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prins ND, Scheltens P. White matter hyperintensities, cognitive impairment and dementia: an update. Nat Rev Neurol 2015; 11:157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Groot JC, De Leeuw FE, Oudkerk M, et al. Cerebral white matter lesions and cognitive function: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Ann Neurol 2000; 47:145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Heuvel DM, ten Dam VH, de Craen AJ, et al. Increase in periventricular white matter hyperintensities parallels decline in mental processing speed in a non-demented elderly population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006; 77:149–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Dijk EJ, Prins ND, Vrooman HA, et al. Progression of cerebral small vessel disease in relation to risk factors and cognitive consequences. Stroke 2008; 39:2712–2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Brien J, Desmond P, Ames D, et al. A magnetic resonance imaging study of white matter lesions in depression and Alzheimer's disease. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waldemar G, Christiansen P, Larsson HB, et al. White matter magnetic resonance hyperintensities in dementia of the Alzheimer type: morphological and regional cerebral blood flow correlates. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994; 57:1458–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshita M, Fletcher E, Harvey D, et al. Extent and distribution of white matter hyperintensities in normal aging, MCI, and AD. Neurology 2006; 67:2192–2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sundar U, Manwatkar AA, Joshi AR, et al. The effect of hypertension and diabetes mellitus on white matter changes in MRI brain: a comparative study between patients with Alzheimer’s disease and an age-matched control group. J Assoc Physicians India 2019; 67:14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Straaten EC, Harvey D, Scheltens P, et al. Periventricular white matter hyperintensities increase the likelihood of progression from amnestic mild cognitive impairment to dementia. J Neurol 2008; 255:1302–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prins ND, van Dijk EJ, den Heijer T, et al. Cerebral white matter lesions and the risk of dementia. Arch Neurol 2004; 61:1531–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bangen KJ, Thomas KR, Weigand AJ, et al. Pattern of regional white matter hyperintensity volume in mild cognitive impairment subtypes and associations with decline in daily functioning. Neurobiol Aging 2020; 66:134–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brickman AM, Zahodne LB, Guzman VA, et al. Reconsidering harbingers of dementia: progression of parietal lobe white matter hyperintensities predicts Alzheimer's disease incidence. Neurobiol Aging 2015; 36:27–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brickman AM, Provenzano FA, Muraskin J, et al. Regional white matter hyperintensity volume, not hippocampal atrophy, predicts incident Alzheimer disease in the community. Arch Neurol 2012; 69:1621–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeCarli C, Fletcher E, Ramey V, et al. Anatomical mapping of white matter hyperintensities (WMH): exploring the relationships between periventricular WMH, deep WMH, and total WMH burden. Stroke 2005; 36:50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sachdev P, Wen W. Should we distinguish between periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensities? Stroke 2005; 36:2342–2343. author reply 2343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wen W, Sachdev P. The topography of white matter hyperintensities on brain MRI in healthy 60- to 64-year-old individuals. Neuroimage 2004; 22:144–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erkinjuntti T, Gao F, Lee DH, et al. Lack of difference in brain hyperintensities between patients with early Alzheimer's disease and control subjects. JAMA Neurol 1994; 51:260–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffanti L, Jenkinson M, Suri S, et al. Classification and characterization of periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensities on MRI: a study in older adults. Neuroimage 2018; 170:174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nir TM, Jahanshad N, Villalon-Reina JE, et al. Effectiveness of regional DTI measures in distinguishing Alzheimer’s disease, MCI, and normal aging. Neuroimage Clin 2013; 3:180–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sled JG, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 1998; 17:87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rusinek H, Glodzik L, Mikheev A, et al. Fully automatic segmentation of white matter lesions: error analysis and validation of a new tool. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg 2013; 8:281–291. [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Heuvel DM, ten Dam VH, de Craen AJ, et al. Fully automatic segmentation of white matter lesions: error analysis and validation of a new tool. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006; 77:149–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shrout PE. Measurement reliability and agreement in psychiatry. Stat Methods Med Res 1998; 7:301–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bombois S, Debette S, Delbeuck X, et al. Prevalence of subcortical vascular lesions and association with executive function in mild cognitive impairment subtypes. Stroke 2007; 38:2595–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Leeuw FE, Korf E, Barkhof F, et al. White matter lesions are associated with progression of medial temporal lobe atrophy in Alzheimer disease. Stroke 2006; 37:2248–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo C, Niu K, Luo Y, et al. Intra-scanner and inter-scanner reproducibility of automatic white matter hyperintensities quantification. Front Neurosci 2019; 13:679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryu WS, Woo S, Schellingerhout D, et al. Grading and interpretation of white matter hyperintensities using statistical maps. Stroke 2014; 45:3567–3575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernández MCV, Piper RJ, Bastin ME, et al. Morphologic, distributional, volumetric, and intensity characterization of periventricular hyperintensities. Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35:55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]