Abstract

N-Methyl-d-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) are ionotropic ligand-gated glutamate receptors that mediate fast excitatory synaptic transmission in the central nervous system (CNS). Several neurological disorders may involve NMDAR hypofunction, which has driven therapeutic interest in positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) of NMDAR function. Here we describe modest changes to the tetrahydroisoquinoline scaffold of GluN2C/GluN2D-selective PAMs that expands activity to include GluN2A- and GluN2B-containing recombinant and synaptic NMDARs. These new analogues are distinct from GluN2C/GluN2D-selective compounds like (+)-(3-chlorophenyl)(6,7-dimethoxy-1-((4-methoxyphenoxy)methyl)-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-2(1H)-yl)methanone (CIQ) by virtue of their subunit selectivity, molecular determinants of action, and allosteric regulation of agonist potency. The (S)-enantiomers of two analogues (EU1180–55, EU1180–154) showed activity at NMDARs containing all subunits (GluN2A, GluN2B, GluN2C, GluN2D), whereas the (R)-enantiomers were primarily active at GluN2C- and GluN2D-containing NMDARs. Determination of the actions of enantiomers on triheteromeric receptors confirms their unique pharmacology, with greater activity of (S) enantiomers at GluN2A/GluN2D and GluN2B/GluN2D subunit combinations than (R) enantiomers. Evaluation of the (S)-EU1180–55 and EU1180–154 response of chimeric kainate/NMDA receptors revealed structural determinants of action within the pore-forming region and associated linkers. Scanning mutagenesis identified structural determinants within the GluN1 pre-M1 and M1 regions that alter the activity of (S)-EU1180–55 but not (R)-EU1180–55. By contrast, mutations in pre-M1 and M1 regions of GluN2D perturb the actions of only the (R)-EU1180–55 but not the (S) enantiomer. Molecular modeling supports the idea that the (S) and (R) enantiomers interact distinctly with GluN1 and GluN2 pre-M1 regions, suggesting that two distinct sites exist for these NMDAR PAMs, each of which has different functional effects.

Keywords: Electrophysiology, molecular dynamics, EPSC, positive allosteric modulator

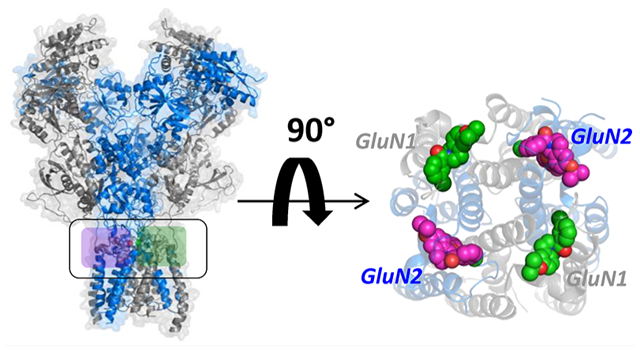

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

NMDA (N-methyl-d-aspartate) receptors, together with AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid) and kainate receptors, comprise a family of ligand-gated ionotropic glutamate receptors.1 NMDA receptors (NMDARs) mediate a slow, Ca2+-permeable component of the fast excitatory postsynaptic current2 and play an important role in nervous system development, learning and memory,3,4 and overall synaptic plasticity.5,6 The activation of NMDARs requires simultaneous binding of coagonists glutamate and glycine,1,7 triggering the opening of a cation-selective pore. Block of the channel pore by external Mg2+ can be relieved by membrane depolarization, providing a voltage dependence to NMDAR-mediated currents that enables these receptors to act as detectors of coincident depolarization and glutamate release.7–9 The general structural organization of each NMDAR subunit is similar to four distinct semiautonomous domains: an amino-terminal domain (NTD), an agonist binding domain (ABD), a transmembrane domain (TMD), and a carboxy-terminal domain (CTD).10,11

Whereas all ionotropic glutamate receptors share a similar structural framework, NMDARs are distinct in that they are heterotetrameric assemblies of two glycine-binding GluN1 subunits and two glutamate-binding GluN2 subunits.10,11 Separate genes (GRIN2A, GRIN2B, GRIN2C, and GRIN2D in humans) encode the GluN2A, GluN2B, GluN2C, and GluN2D subunits,1 each of which confers distinctive pharmacological and functional properties onto the NMDAR, including different agonist potency,12 open probability,13–16 and deactivation time course following rapid removal of glutamate.17 The four genes are differentially expressed throughout the CNS and show distinct developmental profiles.18–21 The heteromeric structure creates unique regions of 2- and 4-fold symmetry within the receptor complex, as well as similar but distinct domain interfaces and potential modulator binding sites in homologous (but nonidentical) regions.

NMDARs have been hypothesized to contribute to a number of neurological disorders, including schizophrenia,22,23 Alzheimer’s disease,24 Parkinson’s disease,25 depression,26 and the consequences of brain ischemia.27,28 Furthermore, normal NMDAR function plays an important role in general cognition. Thus, there has been interest in the development of subunit-selective NMDAR allosteric modulators for therapeutic use.29–31 A number of subunit-selective inhibitors have been discovered, including GluN2A-selective TCN-20132–34 and GluN2B-selective ifenprodil,35,36 as well as several GluN2C/GluN2D-selective series,37–39 the most potent and selective of which are N-aryl benzamides (e.g., NAB-14).38 Several classes of subunit-selective positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) of NMDARs have recently been described, including pyrrolidinone (PYD)-containing compounds that show strong selectivity only for NMDARs that contain two GluN2C subunits.40–42 In addition, a class of tetrahydroisoquinolines, including (+)-(3-chlorophenyl)(6,7-dimethoxy-1-((4-methoxyphenoxy)methyl)-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-2(1H)-yl)-methanone (CIQ) as the prototypical analog, are selective positive allosteric modulators at GluN2C and GluN2D subunits.43,44 PAMs that are selective for GluN2A-containing receptors or are pan-potentiators of all subunits have been described,45–48 and naphthalene analogues have been reported with varying degrees of potency and subunit selectivity.49

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that enhancement of NMDAR function could improve memory formation, which may be of therapeutic interest. For example, GluN2B receptor overexpression in the forebrain of mice enhances NMDAR responses,3 improves learning,50 long-term memory,50,51 spatial performance,52 and cued and contextual fear conditioning,52,53 and produces faster fear extinction.54,55 Additional studies have suggested that age-dependent cognitive decline could be linked to decreased levels of synaptic plasticity and GluN2B expression.5,56–58 While polyamines,59 aminoglycoside antibiotics,60 and neurosteroids61 potentiate NMDARs, there still remains a need for more potent modulators that can serve as tools to explore the effects of NMDAR potentiation on circuit function. Moreover, many NMDARs in the CNS contain two different GluN2 subunits,62–64 raising the possibility of identifying small molecules that are sensitive to subunit stoichiometry.41,65–67 Here, we have evaluated the site and mechanism of action of several pan NMDAR potentiators that are derivatives of the prototypical GluN2C/D-selective PAM CIQ. We provide data arguing that four binding sites exist for these PAMs in NMDARs. This is consistent with the TMD-linker sites of action, which exhibit pseudo-4-fold symmetry, with activity of (S) and (R) enantiomers governed by two distinct binding sites, each with different contributions from the GluN1 and GluN2 subunits.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Isopropoxy-Containing Tetrahydroisoquinolines Are Positive Allosteric Modulators of NMDARs.

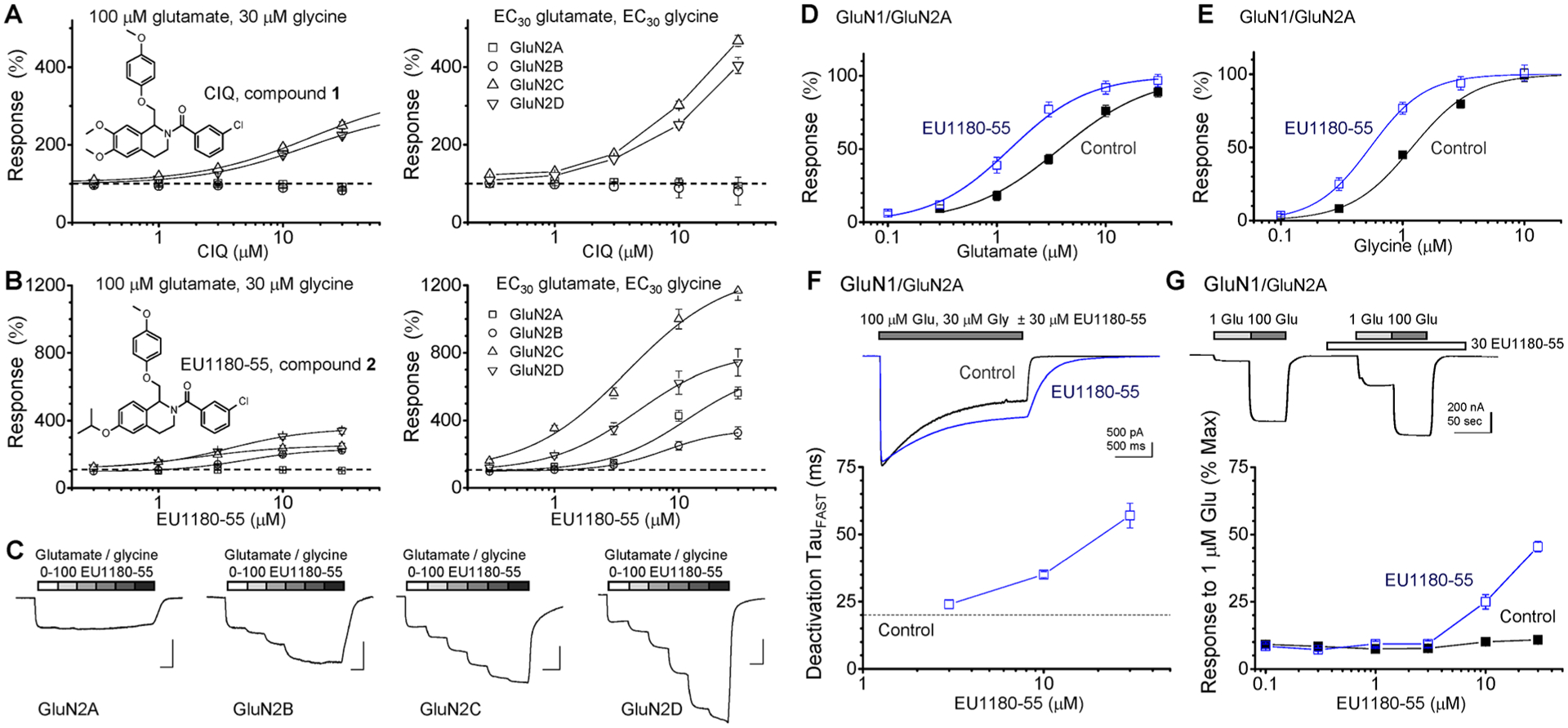

We have previously described a class of positive allosteric modulators built around a tetrahydroisoqinoline core. The prototypical active enantiomer, referred to as (+)-CIQ44,68 (predicted to be (R)), is highly selective for GluN2C- and GluN2D-containing NMDARs over GluN2A- and GluN2B-containing receptors, AMPA receptors, and kainate receptors.43,44 We used two electrode voltage clamp recordings to assess the concentration–response relationship for NMDAR PAMs. CIQ (compound 1 in Figure 1A) enhanced the response to maximally effective concentrations of glutamate and glycine by 2-fold and increased agonist efficacy at low agonist concentrations,44 enhancing responses by as much as 5-fold when receptors are activated by EC30 concentrations of glutamate and glycine (Figure 1A). Even at low agonist concentrations, CIQ remains highly selective for GluN1/GluN2C and GluN1/GluN2D, showing no effect on GluN1/ GluN2A or GluN1/GluN2B receptors.43 We recently discovered that replacement of the dimethoxy substitutient with an isopropoxy moiety on the CIQ core (compound 2 in ref 69 and in Figure 1B, hereafter EU1180–55) potentiates the maximal response to 100 μM glutamate and 30 μM glycine of GluN1/GluN2B by 2.3-fold, GluN1/GluN2C by 2.6-fold, and GluN1/GluN2D by 3.7-fold (Figure 1B,C), with EC50 values ranging between 2 and 5 μM. EU1180–55 produces a 3–10-fold potentiation of the response of GluN2A-, GluN2B-, GluN2C-, and GluN2D-containing NMDARs at low concentrations of agonist (Figure 1B; Supplemental Table S1), bringing the current response amplitude close to those observed for EU1180–55 coapplication with saturating concentrations of agonists. EU1180–55 has no effect on AMPA receptors,69 kainate receptors,69 or GluN1/GluN3 glycine-activated receptors (Supplemental Table S1).

Figure 1.

EU1180–55 potentiates the response of NMDARs. (A) CIQ (compound 1) selectively potentiates the maximal response of only GluN2C- and GluN2D-containing NMDARs following activation with saturating concentrations of glutamate and glycine (left panel) or EC30 agonist concentrations (right panel), which were (for glutamate and glycine) 1.5 and 0.8 μM for GluN1/GluN2A, 1.5 and 0.45 μM for GluN1/GluN2B, 0.85 and 0.2 μM for GluN1/GluN2C, and 0.3 and 0.07 μM for GluN1/GluN2D. The fitted EC50 value for CIQ potentiation of GluN1/GluN2C responses (in saturating agonist) to 340% ± 27% of control was 17 μM (12–18 μM 95% CI); the fitted EC50 value was 15 μM (14–17 μM) for potentiation of GluN1/GluN2D to 281% ± 10% of control. The EC50 value for CIQ potentiation of NMDAR activation by EC30 concentrations of glutamate and glycine (right panel) could not be determined. (B) EU1180–55 (compound 2) potentiates NMDARs during activation by saturating concentrations of agonists (left panel) to 226% ± 10% of control with an EC50 of 4.6 μM (4.0–5.1 μM) for GluN1/GluN2B, to 259% ± 27% of control with an EC50 of 1.9 μM (1.4–2.2 μM) for GluN1/GluN2C, to 366% ± 27% of control with an EC50 of 4.1 μM (2.5–4.6 μM) for GluN1/GluN2D. The EC50 values for EU1180–55 potentiation of current responses activated by EC30 concentrations of agonists ranged between 4.3 and 7.9 μM (right panel; Supplemental Table S1). For all experiments, data are from 5 to 22 oocytes from 2 to 3 batches of oocytes. (C) Representative example of two electrode voltage clamp recording showing that 1, 3, 10, 30, and 100 μM EU1180–55 potentiates the response of GluN2B-, GluN2C-, and GluN2D-containing NMDARs expressed in Xenopus oocytes activated by 100 μM glutamate and 30 μM glycine. (D, E) EU1180–55 (30 μM) increases the potency for glutamate and glycine at GluN1/GluN2A NMDA receptors; fitted EC50 values are given in Table 1. (F) GluN1/GluN2A NMDAR response time courses are superimposed in the absence or presence of 30 μM EU1180–55; for EU1180–55 experiments, the compound was included in both the wash and the glutamate solution; 30 μM glycine was present in all solutions. The fitted time constants describing the deactivation time course are in Table 2. Plot of TauFAST vs concentration for 3, 10, and 30 μM EU1180–55 (n = 3 cells). (G) EU1180–55 enhances glutamate potency for GluN1/GluN2A at concentrations above 3 μM, as assessed by the concentration–response curve for EU1180–55 enhancement of the fractional current response to a submaximal concentration of glutamate (1 μM) in the presence of saturating glycine (30 μM), expressed as a percent of the response to 100 μM glutamate and 30 μM glycine (n = 5–6 oocytes for each point).

CIQ has virtually no detectable effect on glutamate potency at GluN1/GluN2A, GluN1/GluN2B, or GluN1/GluN2D, but modestly increases glutamate potency at GluN1/GluN2C (Table 1). By contrast, 30 μM EU1180–55 produced detectable increases in glutamate potency (i.e., reduced EC50) at all subunits, the largest effect being a 2.8-fold enhancement of glutamate potency for GluN1/GluN2A (Table 1, Figure 1D,E). EU1180–55 (30 μM) decreased the mean glycine EC50 with nonoverlapping 95% confidence intervals (in parentheses) from 1.2 (1.1–1.3) to 0.58 (0.46–0.66) μM for GluN1/GluN2A (n = 10–11) and from 0.46 (0.42–0.49) to 0.31 (0.20–0.35) μM for GluN1/GluN2B (n = 13–21). EU1180–55 had no detectable effect on glycine EC50 for GluN1/GluN2C, which was 0.29 (0.26–0.31) μM in the absence and 0.24 (0.19–0.27) μM in the presence of EU1180–55 (n = 13–14), or on GluN1/GluN2D glycine EC50, which was 0.17 (0.13–2.0) μM in the absence and 0.15 (0.12–0.18) μM in the presence of 30 μM EU1180–55 (n = 9–13). Thus, EU1180–55 appears to show subunit selectivity, allosterically modulating agonist potency at GluN2A- and GluN2B-containing NMDARs, a property that is distinct from GluN2C/GluN2D-selective PAMs such as CIQ, which do not detectably alter EC50 values.

Table 1.

Effect of Positive Allosteric Modulators CIQ, EU1180–55, and EU1180–154 on Glutamate EC50a

| mean EC50, μM (95% CI) | EC50/EC50+DRUG | mean EC50, μM (95% CI) | EC50/EC50+DRUG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | 20 μM racemic CIQ | 30 μM racemic EU1180–55 | |||

| GluN1/GluN2A | 4.2 (3.7–4.5, N = 23) | 4.5 (3.5–5.3, N = 11) | 0.93 | 1.5b (1.0–1.7, N = 15) | 2.8 |

| GluN1/GluN2B | 1.5 (1.3–1.6, N = 37) | 1.6 (1.4–1.7, N = 17) | 0.94 | 1.1b (1.0–1.2, N = 28) | 1.4 |

| GluN1/GluN2C | 1.0 (0.82–1.1, N = 32) | 0.51b (0.41–0.58, N = 11) | 2.0 | 0.28b (0.21–0.30, N = 26) | 3.6 |

| GluN1/GluN2D | 0.33 (0.28–0.35, N = 35) | 0.33 (0.28–0.36, N = 14) | 1.0 | 0.19b (0.15–0.20, N = 29) | 1.7 |

| mean EC50, μM (95% CI) | EC50/EC50+DRUG | mean EC50, μM (95% CI) | EC50/EC50+DRUG | ||

| control | 10 μM (S)-EU1180–55 | 10 μM (R)-EU1180–55 | |||

| GluN1/GluN2A | 3.8 (3.4–4.0, N = 18) | 1.0b (0.78–1.2, N = 16) | 3.8 | 4.2 (3.6–4.7, N = 13) | 0.90 |

| GluN1/GluN2B | 1.3 (1.1–1.4, N = 11) | 0.83b (0.71–0.92, N = 10) | 1.6 | 1.2 (1.1–1.3, N = 13) | 1.1 |

| GluN1/GluN2C | 0.88 (0.66–0.99, N = 14) | 0.43b (0.36–0.48, N = 9) | 2.0 | 0.37b (0.32–0.41, N = 14) | 2.4 |

| GluN1/GluN2D | 0.30 (0.28–0.32, N = 21) | 0.31 (0.28–0.34, N = 13) | 1.0 | 0.22b (0.19–0.24, N = 16) | 1.4 |

| mean EC50, μM (95% CI) | EC50/EC50+DRUG | mean EC50, μM (95% CI) | EC50/EC50+DRUG | ||

| control | 10 μM (S)-EU1180–154 | 10 μM (R)-EU1180–154 | |||

| GluN1/GluN2A | 4.6 (3.7–5.0, N = 24) | 2.0b (1.4–2.2, N = 18) | 2.3 | 4.2 (3.8–4.5, N = 21) | 1.1 |

| GluN1/GluN2B | 1.4 (1.2–1.5, N = 21) | 1.0b (0.84–1.1, N = 15) | 1.4 | 1.3 (1.1–1.4, N = 17) | 1.1 |

| GluN1/GluN2C | 1.1 (0.80–1.2, N = 21) | 0.77 (0.63–0.85, N = 17) | 1.4 | 0.80 (0.58–0.90, N = 19) | 1.4 |

| GluN1/GluN2D | 0.35 (0.30–0.39, N = 19) | 0.38 (0.30–0.42, N = 22) | 0.92 | 0.41 (0.38–0.44, N = 15) | 0.85 |

Mean fitted EC50 values are shown to two significant figures. The 95% confidence interval determined from log EC50 is given in parentheses; N is the number of oocytes. Control recordings were performed on the same day as the recordings in the presence of modulator. One way ANOVA was performed on the log(EC50) values.

p < 0.05, Bonferroni post hoc test. Power to detect an effect size of 0.5 was 0.88–0.97 for CIQ and EU1180–55, 0.73–0.87 for (S)- and (R)-EU1180–55, and 0.90–0.94 for (S)- and (R)-EU1180–154.

We evaluated the actions of EU1180–55 on current responses of NMDARs with and without 21 residues in the NTD encoded by the alternatively spliced GluN1 exon5, which controls key features of the NMDA receptor such as agonist potency, response time course, and sensitivity to endogenous modulators.16,59,70,71 For diheteromeric receptors that contained GluN1 plus either GluN2B, GluN2C, or GluN2D, EU1180–55 increased the NMDAR response to saturating concentrations of glutamate and glycine for both exon5-lacking and exon5-containing GluN1 subunits, although there was reduced maximal potentiation at saturating concentrations of EU1180–55 at the exon5-containing GluN1 NMDARs (Supplemental Figure S1). The presence of GluN1 exon5 did not diminish the ability of 30 μM EU1180–55 to enhance glutamate potency; EU1180–55 decreased glutamate EC50 at exon5-containing GluN1–1b/GluN2A NMDARs from 14 μM (95% CI 11–16 μM, n = 6) to 3.1 μM (2.2–4.0 μM, n = 7). By contrast, we could not detect an effect of exon5 on the maximal response of NMDARs to GluN2C/GluN2D-selective tetrahydroisoquinolines such as CIQ,43 providing another distinguishing feature for the EU1180–55 series.

EU1180–55 Modulators Prolong the Deactivation Time Course of NMDARs.

Racemic EU1180–55 significantly potentiated the peak response of GluN1/GluN2A (1.6-fold), GluN1/GluN2B (1.5-fold), GluN1/GluN2C (2.9-fold), and GuN1/GluN2D (3.4-fold) NMDARs expressed in HEK cells to maximally effective concentrations of glutamate and glycine applied rapidly for 2 s (Supplemental Table S2). In addition, EU1180–55 slowed the weighted mean time constant describing deactivation following rapid removal of glutamate in HEK cells for GluN1/GluN2A (3.5-fold), GluN1/GluN2B (1.4-fold), GluN1/GluN2C (1.7-fold), and GuN1/GluN2D (1.5-fold) NMDARs (Supplemental Figure S2, Table S2), consistent with the predicted slower dissociation of agonist from its binding pocket following an EU1180–55-induced increase in glutamate potency.72 The concentration-dependence of EU1180–55 on the prolongation of GluN1/GluN2A deactivation was similar to that for the EU1180–55-induced shift in glutamate potency (Figure 1F,G). By contrast, CIQ had no detectable effect on the deactivation time course following glutamate removal at GluN1/GluN2A, GluN1/GluN2B, or GluN1/GluN2D, although modest effects of CIQ were reported for the glutamate deactivation of GluN1/GluN2C (see Table 2 in ref 43). These data further show that EU1180–55 produces allosteric modulation of agonist potency that is distinct from GluN2C/D-selective PAMs such as CIQ, raising the possibility that EU1180–55 and CIQ do not share the same mechanism of action.

Table 2.

Effect of EU1180–55 and EU1180–154 Enantiomers on the Glutamate Response Time Course

| amplitude (pA)a | deactivation τW (ms)b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | (S)-EU1180–55 | foldc | N | control | (S)-EU1180–55 | foldc | N | |

| GluN1/GluN2A | 768 ± 141 | 1604 ± 297 | 2.1d | 11 | 80 ± 9.7 | 250 ± 24 | 3.1d | 9 |

| GluN1/GluN2B | 454 ± 172 | 1290 ± 436 | 2.8d | 7 | 569 ± 45 | 934 ± 47 | 1.6d | 10 |

| GluN1/GluN2C | 152 ± 42 | 879 ± 213 | 5.8d | 7 | 513 ± 25 | 716 ± 40 | 1.4d | 16 |

| GluN1/GluN2D | 204 ± 51 | 856 ± 215 | 4.2d | 7 | 5510 ± 329 | 6500 ± 357 | 1.2d | 12 |

| amplitude (pA)a | deactivation τW (ms)b | |||||||

| control | (R)-EU1180–55 | foldc | N | control | (R)-EU1180–55 | foldc | N | |

| GluN1/GluN2A | 1020 ± 241 | 1560 ± 364 | 1.5d | 12 | 55 ± 4.5 | 89 ± 6.3 | 1.6d | 8 |

| GluN1/GluN2B | 452 ± 143 | 561 ± 179 | 1.2d | 8 | 628 ± 39 | 822 ± 73 | 1.3d | 15 |

| GluN1/GluN2C | 158 ± 34 | 811 ± 145 | 5.1d | 7 | 576 ± 28 | 827 ± 42 | 1.4d | 10 |

| GluN1/GluN2D | 291 ± 102 | 1120 ± 264 | 3.8d | 6 | 6830 ± 279 | 8010 ± 318 | 1.2d | 13 |

| amplitude (pA)a | deactivation τW (ms)b | |||||||

| control | (S)-EU1180–154 | foldc | N | control | (S)-EU1180–154 | foldc | N | |

| GluN1/GluN2A | 754 ± 196 | 1080 ± 337 | 1.4d | 7 | 79 ± 9.2 | 148 ± 22 | 2.0d | 8 |

| GluN1/GluN2B | 600 ± 301 | 1040 ± 418 | 1.7d | 8 | 670 ± 31 | 1001 ± 71 | 1.5d | 10 |

| GluN1/GluN2C | 206 ± 58 | 589 ± 170 | 2.9d | 6 | 433 ± 30 | 609 ± 65 | 1.4d | 6 |

| GluN1/GluN2D | 201 ± 34 | 580 ± 101 | 2.9d | 7 | 5540 ± 156 | 6660 ± 395 | 1.2d | 9 |

| amplitude (pA)a | deactivation τW (ms)b | |||||||

| control | (R)-EU1180–154 | foldc | N | control | (R)-EU1180–154 | foldc | N | |

| GluN1/GluN2A | 841 ± 146 | 1130 ± 219 | 1.3d | 10 | 56 ± 5.5 | 66 ± 5.9 | 1.3 | 15 |

| GluN1/GluN2B | 422 ± 221 | 442 ± 228 | 1.0 | 6 | 616 ± 36 | 720 ± 44 | 1.2d | 12 |

| GluN1/GluN2C | 185 ± 48 | 296 ± 77 | 1.6d | 13 | 411 ± 14 | 522 ± 23 | 1.3d | 8 |

| GluN1/GluN2D | 227 ± 25 | 313 ± 38 | 1.4d | 15 | 5980 ± 384 | 6360 ± 192 | 1.1 | 7 |

Steady-state current response to 100 μM glutamate plus vehicle and the response amplitude following a direct switch to glutamate plus 15 μM (S)- or (R)-EU1180–55 or 5 μM (S)- or (R)-EU1180–154 were measured using whole cell current recordings from transfected HEK cells. Data shown are mean ± SEM; 30 μM glycine was present in all solutions and recordings were made at −70 mV.

Agonist-evoked currents were recorded in response to rapid application of 100 μM glutamate plus 30 μM glycine for 1.5 s. (S)- or (R)-EU1180–55 (15 μM) or (S)- or (R)-EU1180–154 (5 μM) was added to the glycine-containing wash, and the glutamate/glycine-containing solution and recordings were repeated in the same cell. Recordings were made at −70 mV.

Fold is the ratio of parameter in drug to control.

p < 0.05 by paired t test of amplitude and weighted tau (τW). Power to detect an effect size of 1.5 was 0.8–0.99 for steady-state amplitude and for weighted tau.

Agonist-dependent actions of a drug occur when the affinity of the modulator for its site is different for a channel that has opened (use-dependent) or has bound agonist (agonist-dependent) than for closed channels or channels without agonist bound. For agonist-dependence, a subsaturating concentration of PAM will occupy a different fraction of its binding sites in the absence of agonist compared to in the presence of agonist. This can appear as a rapidly rising response in the presence of modulator to the same amplitude as a control response, followed by a slower enhancement of the response amplitude if the positive allosteric modulator slowly binds after agonist has bound due to increased affinity for modulator of agonist-bound receptor.46 In this case, the rising phase of a response will show a biphasic trajectory, with a slow component that is dependent on modulator concentration and the overall rise time will appear to be slowed. In order to determine whether EU1180–55 might show agonist-dependence, we evaluated the 10–90% rise time of the current response for receptors pre-equilibrated with 30 μM EU1180–55 prior to and during 1 mM glutamate rapid application for 1.5 s with 30 μM glycine present in all solutions. EU1180–55 slowed the 10–90% rise time of the response to glutamate for all NMDARs. Rise time in the absence and presence of EU1180–55 was 9.6 ± 1.7 and 16 ± 3.6 ms for GluN1/GluN2A (n = 7, p = 0.021), 17 ± 1.7 and 44 ± 7.1 ms for GluN1/GluN2B (n = 6, p = 0.0089), 13 ± 2.1 and 19 ± 2.0 ms for GluN1/GluN2C (n = 6, p = 0.0025), and 12 ± 1.4 and 18 ± 1.7 ms for GluN1/GluN2D (n = 6, p = 0.031, paired t test for all; see Supplemental Figure S3). The slower rise time of the response suggests that EU1180–55 may bind to the receptor and potentiate the response after agonist binding, perhaps in an agonist-dependent fashion. However, any agonist dependence is not as strong as has been observed for other pan-NMDA positive allosteric modulators.45,46

There was no detectable difference between the ratio of the steady state current to the peak current and the time constant describing the onset of desensitization in the absence or presence of 30 μM EU1180–55 (Supplemental Table S2, Supplemental Figure S2). The peak-to-steady state ratio was 0.65 ± 0.053 for control vs 0.72 ± 0.050 in 30 μM EU1180–55 (n = 10, p < 0.11) for GluN1/GluN2A and was 0.70 ± 0.033 for control vs 0.65 ± 0.045 in 30 μM EU1180–55 (n = 11, p < 0.09) for GluN1/GluN2B following prolonged 1 s responses to 100 μM glutamate and 30 μM glycine. We also observed no effect of EU1180–55 on the time constant describing the onset of desensitization for these same responses, which in the absence and presence of EU1180–55 were 1400 ± 284 vs 1560 ± 373 ms for GluN1/GluN2A (n = 9) and 660 ± 93 vs 818 ± 161 ms for GluN1/GluN2B (n = 10), respectively. Thus, EU1180–55 does not appear to influence desensitization.

Activity of Amide and Thioamide-Containing EU1180–55 Analogues.

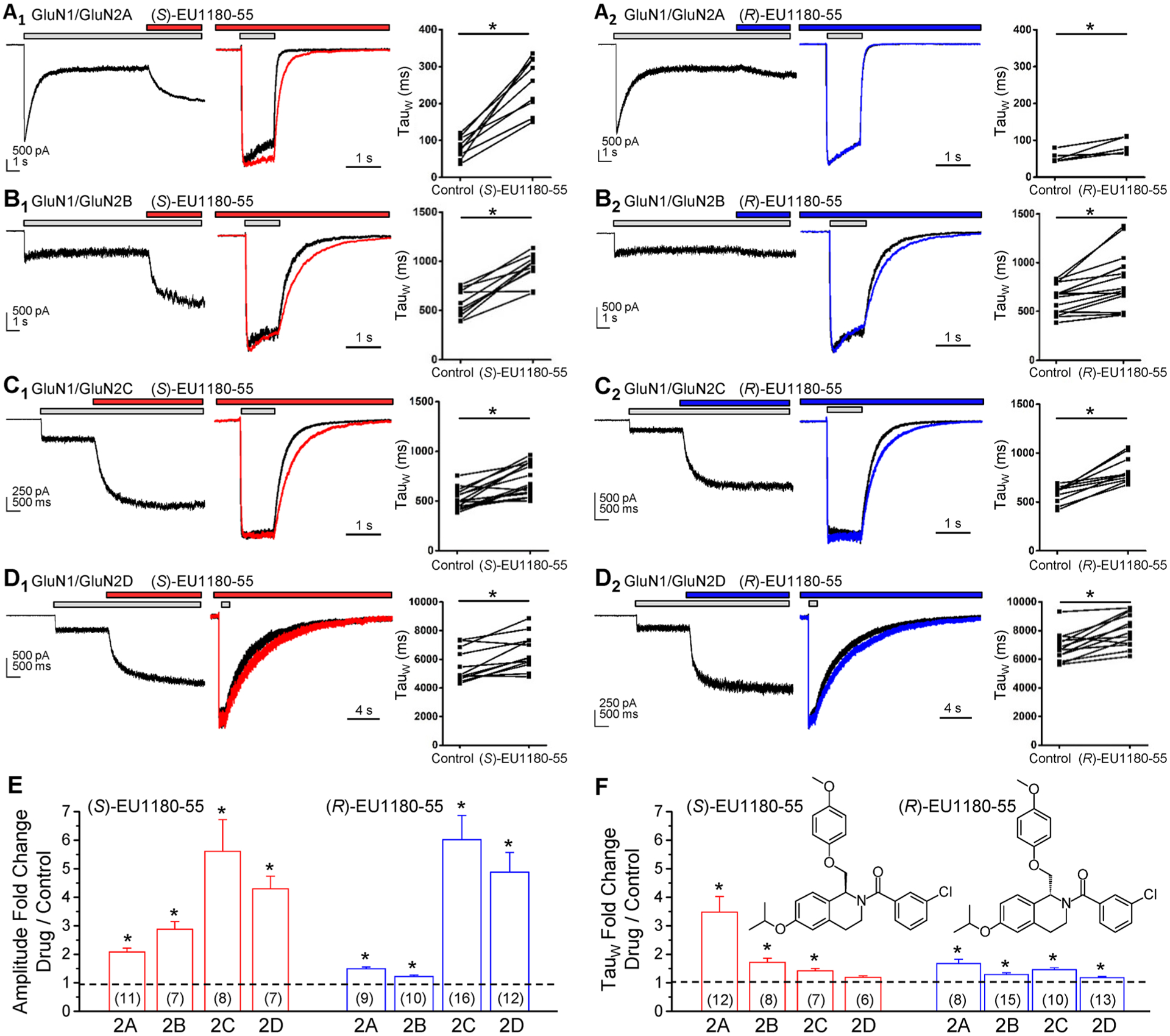

The tetrahydroisoquinoline core of both CIQ and EU1180–55 contains a chiral carbon. The (+) enantiomer of CIQ carries strong activity,68 and similarly, (R)-(+)-EU1180–55 is a potent potentiator of GluN2C- and GluN2D-containing NMDARs, with EC50 values of 0.7 and 1.0 μM, respectively.69 We therefore evaluated the actions of the enantiomers of EU1180–55 on the glutamate EC50 determined in oocytes and the response time course determined in HEK cells to assess the enantiomeric selectivity. Table 1 summarizes the effects of (S)- and (R)-EU1180–55 on glutamate EC50. The data suggest stereoselective subunit dependence, with the (S) enantiomer producing significant shifts in glutamate EC50 (increased potency) for GluN2A-, GluN2B-, and GluN2C-containing NMDARs, whereas the (R) enantiomer produced significant shifts in EC50 only for GluN2C- and GluN2D-containing NMDARs. Similar to results from oocytes, (S)-EU1180–55 increased the steady-state current response to maximally effective concentrations of agonists of all NMDARs expressed in HEK cells by 2–6-fold (Figure 2, Table 2). Consistent with its actions on the glutamate EC50, (S)-EU1180–55 prolonged the weighted time constant describing deactivation of GluN2A-, GluN2B-, and GluN2C-containing NMDARs following rapid glutamate removal after both prolonged glutamate application (Table 2, Figure 2, Supplemental Table S3) and brief glutamate application (Supplemental Table S4, Supplemental Figure S4). (R)-EU1180–55 enhanced the maximal steady state response for GluN2C- and GluN2D-containing NMDARs by 4–5-fold, and modestly slowed the weighted time constant describing deactivation of GluN2C- and GluN2D-containing NMDARs. Like (+)-CIQ, (R)-EU1180–55 had only weak effects on the steady-state amplitude and deactivation time course for GluN2A- and GluN2B-containing receptors (Table 2, Supplemental Tables S3 and S4). These results suggest that the two enantiomers have different subunit selectivity, raising the possibility that they act at different binding pockets.

Figure 2.

Subunit-selective actions of EU1180–55 enantiomers. (A1,2) Left panel, representative whole cell current response from a HEK cell expressing GluN1/GluN2A to 100 μM glutamate and 30 μM glycine (plus vehicle, 0.075% DMSO), followed by an immediate switch to glutamate/glycine plus 15 μM (S)-EU1180–55 (A1) or (R)-EU1180–55 (A2). Middle panel, normalized mean whole cell current time course recorded in response to 1.5 s application of 100 μM glutamate and 30 μM glycine in the absence (black) and presence of 15 μM (S)-EU1180–55 (red) or (R)-EU1180–55 (blue); EU1180–55 and glycine were in the wash solution prior to application of glutamate. Right panel, Plot of weighted mean tau in vehicle or test compound. The same experiment is shown for GluN1/GluN2B (B1,2), GluN1/GluN2C (C1,2), and GluN1/GluN2D (D1,2). (E, F) Fold change in steady-state amplitude (E) or weighted tau (F) for (S)-EU1180–55 or (R)-EU1180–55. Fitted time constants for all experiments are given in Table 2 (weighted tau) and Supplemental Table S2 (tauFAST, tauSLOW, relative contribution for tauFAST). * p < 0.05, paired t test.

Conversion of the amide linker to a thioamide, together with substitution of F for Cl and p-ethoxy for p-methoxy yielded the (S) enantiomer of compound 3 (compound (S)-(−)-142 in Strong et al.,69 hereafter (S)-EU1180–154, Supplemental Figure S5), which potentiated GluN2B-, GluN2C-, and GluN2D-containing NMDARs with EC50 values of 380–580 nM.69 By contrast, (R)-EU1180–154 was largely without activity at recombinant NMDARs in oocytes.69 We evaluated the effects of (S)-EU1180–154 and (R)-EU1180–154 on glutamate potency as well as the glutamate response time course in recombinant NMDARs expressed in HEK cells. These experiments confirmed that (S)-EU1180–154 can reduce the glutamate EC50 for GluN2A- and GluN2B-containing receptors (Table 1), and can enhance the peak current as well as slow the deactivation following glutamate removal for all NMDARs (Table 2). By contrast, (R)-EU1180–154 had minimal activity on amplitude, EC50, and glutamate deactivation time course (Tables 1 and 2; see also Supplemental Table S3 and Supplemental Figure S5). These data further suggest distinct actions of (S)- and (R)-EU1180–154 derivatives.

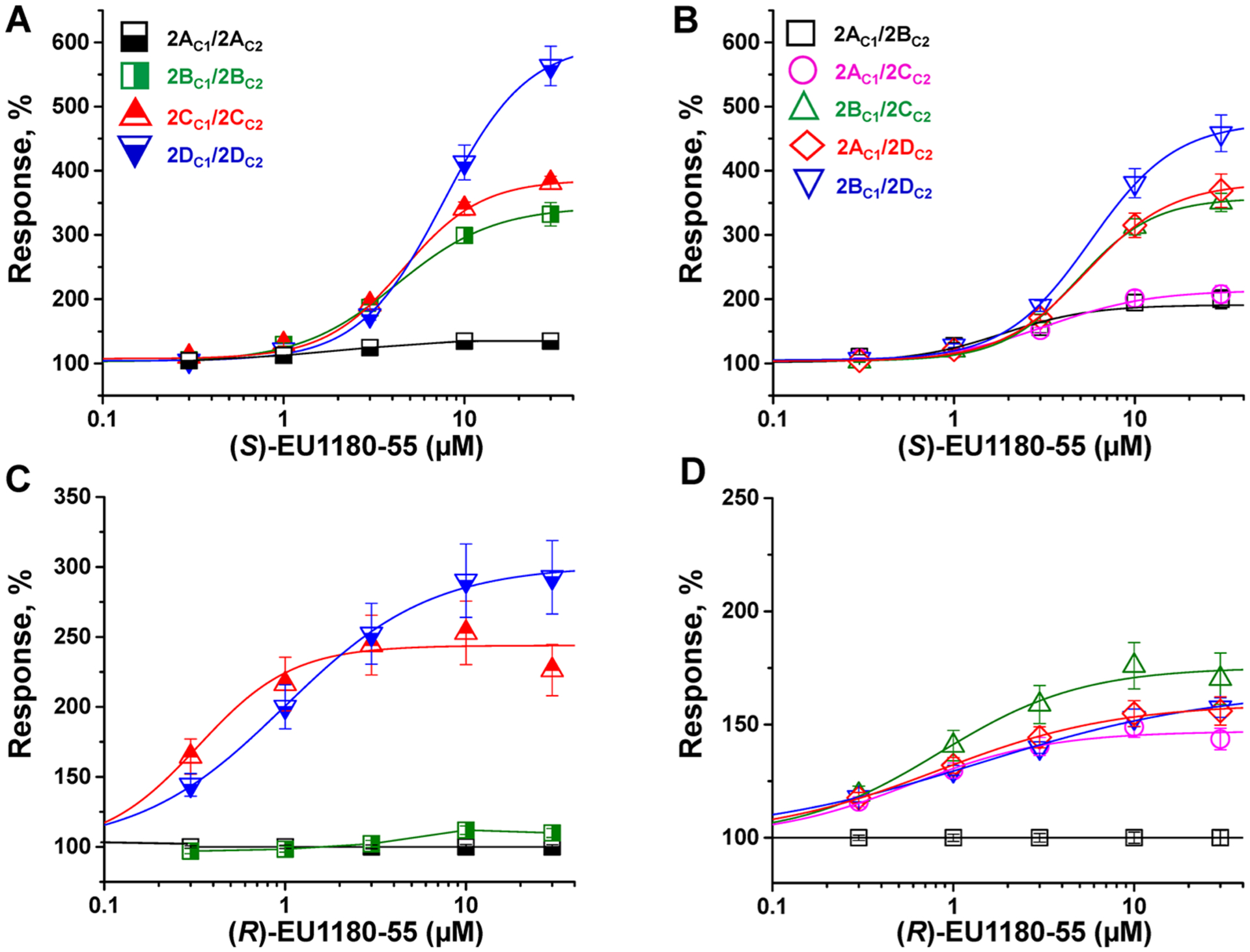

EU1180–55 Enantiomers Show Distinct Activity at Triheteromeric NMDARs.

Many NMDARs in the adult brain contain GluN1 together with two different GluN2 subunits, which are often referred to as triheteromeric receptors.64,67,73–75 To evaluate the activity of EU1180–55 analogues at triheteromeric NMDARs, we used a series of chimeric fusion proteins in which the GluN2A C-terminus replaced the GluN2B, GluN2C, or GluN2D C-termini. A synthetic linker followed by a coiled-coil domain and endoplasmic reticulum retention sequence was fused in-frame to each modified GluN2A C-terminus, allowing the control of GluN2 stoichiometry at the cell surface (see Methods).62 We evaluated the concentration–response relationship for both (S)-EU1180–55 and (R)-EU1180–55 on nine of the ten possible subunit combinations in oocytes, including GluN2AC1/GluN2AC2, GluN2BC1/GluN2BC2, GluN2CC1/GluN2CC2, GluN2DC1/GluN2DC2, GluN2AC1/GluN2BC2, GluN2AC1/GluN2CC2, GluN2AC1/GluN2DC2, GluN2BC1/GluN2CC2, and GluN2BC1/GluN2DC2.. We estimated the percent of the observed current response mediated by the desired subunit combination by measuring the escape current for receptors that contained two copies of either the GluN2C1 or GluN2C2 (see Methods).62 Figure 3 and Table 3 summarize the results of these experiments and show that (S)-EU1180–55 has the strongest effects at saturating glutamate and glycine concentrations on triheteromeric receptors that contain the GluN2D subunit. (S)-EU1180–55 is also able to potentiate GluN2B- and GluN2C-containing receptors to a significant extent. The EC50 value for (S)-EU1180–55 potentiation was similar for all triheteromeric receptors (3–8 μM). (R)-EU1180–55 also could potentiate GluN2C- and GluN2D-containing receptors, but had no effect on GluN1/GluN2A, GluN1/GluN2B, and GluN1/GluN2A/GluN2B NMDARs (Table 3). (R)-EU1180–55 was most potent at diheteromeric GluN1/GluN2C receptors and showed the strongest potentiation at GluN1/GluN2D NMDARs. These data suggest triheteromeric receptors will have unique sensitivity to allosteric modulators that is governed by their specific combination of GluN2 subunits.

Figure 3.

Potentiation of triheteromeric NMDARs in response to (S)-EU1180–55 or (R)-EU1180–55 in the presence of 100 μM glutamate and 30 μM glycine in Xenopus oocytes: concentration–response relationships for potentiation of diheteromeric NMDARs (A, C) and triheteromeric NMDARs (B, D) by (S)-EU1180–55 or (R)-EU1180–55. Experiments were performed 2–3 times from different batches of oocytes. Each data point is represented as mean ± SEM (see Table 3 for EC50 values; n ≥ 8 oocytes for all data points).

Table 3.

EC50 Values for EU1180–55 Modulation of Triheteromeric NMDARsa

| Triheteromeric receptor | (S)-EU1180–55 | (R)-EU1180–55 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50, μM (95% CI) | I(S)-EU180–55/ICONTROL, % | N | EC50, μM (95% CI) | I(R)-EU180–55/ICONTROL, % | N | |

| GluN1/GluN2A/GluN2A | b | b | 47 | b | b | 42 |

| GluN1/GluN2B/GluN2B | 4.3 (3.6–4.5) | 332 ± 18 | 37 | b | b | 37 |

| GluN1/GluN2C/GluN2C | 5.2 (4.2–6.3) | 384 ± 11 | 15 | 0.45 (0.38–0.54) | 230 ± 16 | 19 |

| GluN1/GluN2D/GluN2D | 8.0 (7.0–8.9) | 563 ± 31 | 8 | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 293 ± 26 | 11 |

| GluN1/GluN2A/GluN2B | 3.1 (2.7–3.5) | 200 ± 15 | 10 | b | b | 15 |

| GluN1/GluN2A/GluN2C | 3.0 (2.6–3.5) | 202 ± 13 | 13 | 1.3 (1.0–1.5) | 145 ± 4.8 | 16 |

| GluN1/GluN2A/GluN2D | 5.3 (4.8–5.9) | 369 ± 26 | 13 | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | 156 ± 6.3 | 12 |

| GluN1/GluN2B/GluN2C | 4.9 (4.4–5.3) | 351 ± 14 | 10 | 1.5 (0.95–2.3) | 170 ± 11 | 8 |

| GluN1/GluN2B/GluN2D | 5.5 (5.0–6.2) | 458 ± 29 | 16 | 2.3 (2.0–2.6) | 158 ± 4.3 | 9 |

All chimeric GluN2 subunits contained the GluN2A C-terminal region plus C1 or C2 and an ER retention signal, as described in the Methods. All NMDAR currents were recorded in response to 100 μM glutamate and 30 μM glycine. The mean fitted EC50 value to 2 significant figures is given with the 95% confidence interval (CI) determined from the log (EC50 values). The mean ± SEM of the response to 30 μM test compound is given as a percent of the response in the absence of test drug to 3 significant figures. Non-overlapping confidence intervals were considered statistically significant. Hill slopes ranged from 0.6–2.6. N is the number of oocytes. For comparison, EC50 values from ref 69 for potentiation of wild-type diheteromeric NMDARs by (S)-EU1180–55 (compound S-(−)-2) were GluN1/GluN2A (no effect), GluN1/GluN2B (3.0 μM, maximum 276%), GluN1/GluN2C (3.1 μM, maximum 277%), GluN1/GluN2D (3.8 μM, maximum 267%). EC50 values from ref 69 for potentiation of wild-type diheteromeric NMDARs by (R)-EU1180–55 (compound R-(+)-2) were GluN1/GluN2A (no effect), GluN1/GluN2B (no effect), GluN1/GluN2C (0.71 μM, maximum 252%), GluN1/GluN2D (1.0 μM, maximum 297%).

No detectable effect.

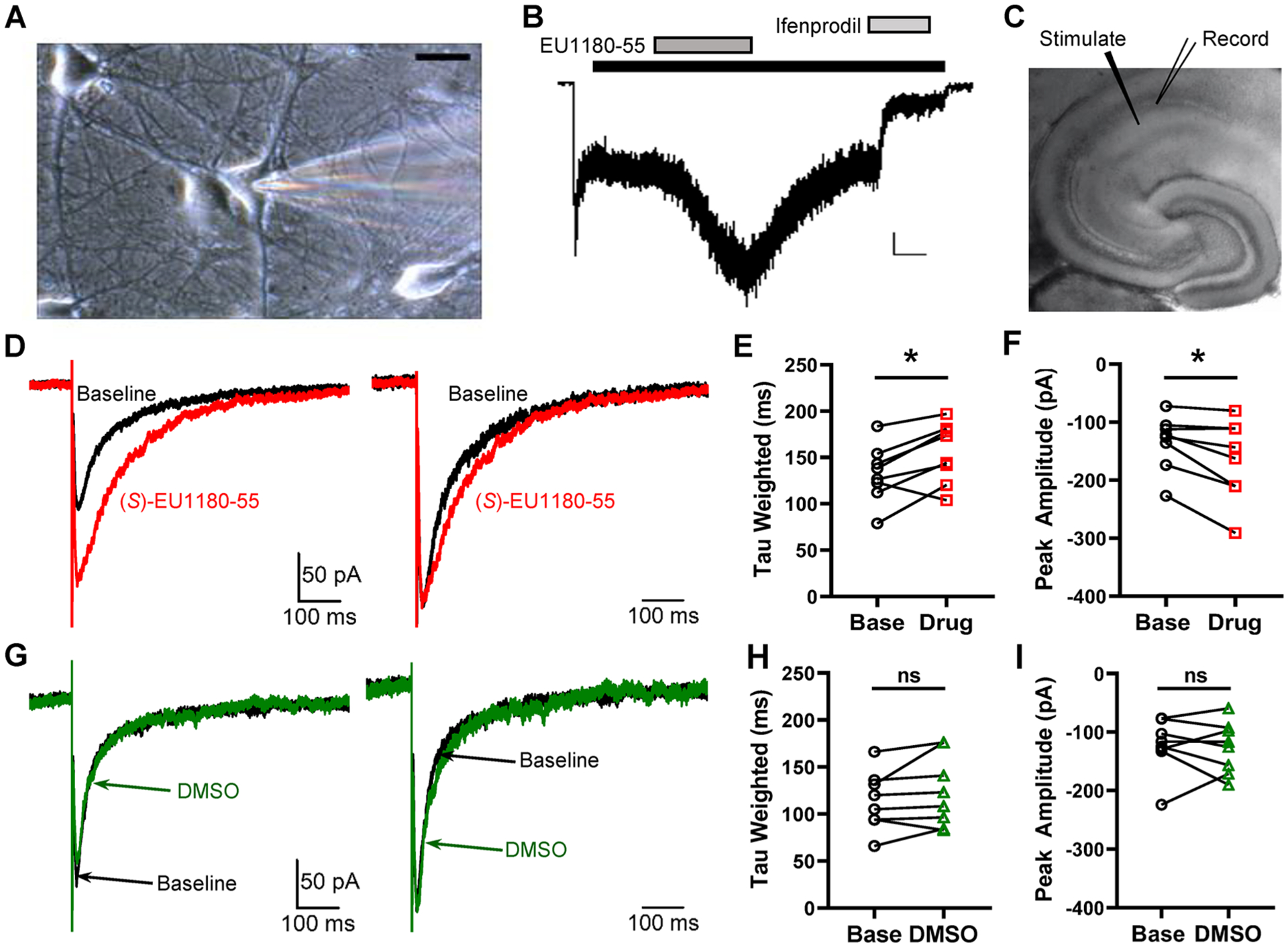

(S)-EU1180–55 Prolongs the Synaptic NMDAR-Mediated Excitatory Postsynaptic Current (EPSC) Time Course in Hippocampal Neurons.

The active enantiomer of tetrahydroisoquinoline, (+)-CIQ, can potentiate native GluN2D-containing NMDARs.68 However, the novel selectivity we discovered for the isopropoxy containing (S) enantiomer in the tetrahydroisoquinoline series has not been tested on native NMDARs. To determine whether (S)-EU1180–55 can potentiate NMDARs in neurons, we performed patch clamp recordings from cultured hippocampal neurons, which predominantly express GluN1/GluN2B receptors. We found that racemic EU1180–55 strongly potentiated ifenprodil-sensitive currents, suggesting the (S) enantiomer also enhances responses to native GluN2B-containing neurons. We subsequently evaluated the effects of (S)-EU1180–55 on the NMDAR-mediated component of the evoked EPSC at the Schaffer collateral-CA1 pyramidal cell synapse, given that CA1 pyramidal cells express GluN2A and GluN2B.18 The NMDAR-mediated EPSC was pharmacologically isolated and measured before (baseline) and after 20 μM (S)-EU1180–55 or DMSO vehicle were washed onto the slice. The weighted mean time constant describing the EPSC time course and the amplitude of the NMDAR-mediated EPSC showed a statistically significant increase for (S)-EU1180–55; DMSO alone had no effect on amplitude or response time course (Figure 4). Values for other parameters such as rise time and charge transfer are given in Supplemental Table S5. These data are consistent with both the prolongation by (S)-EU1180–55 of the deactivation time course for GluN2A- and GluN2B-containing receptors and potentiation of GluN1/GluN2B and GluN1/GluN2A/GluN2B NMDAR-mediated current responses (Figures 2 and 3, Tables 2 and 3, Supplemental Tables S3 and S4, Supplemental Figure S4). These data confirm that (S)-EU1180–55 is active at synaptic GluN2A- and GluN2B-containing NMDARs.

Figure 4.

Effect of EU1180–55 on NMDARs in hippocampal neurons. (A) Representative photomicrograph of a neuron maintained 12 days in culture (calibration 20 μm). The patch electrode can be seen on the right side. (B) Typical current response to 100 μM NMDA and 3 μM glycine (black bar). After the current relaxed to a steady-state level, EU1180–55 (10 μM, dark gray bar) was coapplied with NMDA and glycine, which increased the current response to NMDA in the presence of bicuculline (10 μM), CNQX (10 μM), and TTX (0.5 μM) to 200% ± 10% of control (p = 0.001, paired t test, n = 5). After wash out of EU1180–55, 3 μM ifenprodil, the GluN2B-selective inhibitor (light gray bar), was applied. Ifenprodil inhibited the current to 30% ± 10% of control (p = 0.005, paired t test, n = 5). The calibration bar is 50 pA, 20 s. (C) NMDAR-mediated component of evoked EPSCs recorded at −30 mV in the presence of 0.2 mM Mg2+ from 300 μm hippocampal slices from P7–14 mice. (D) Left panel, representative evoked NMDAR-mediated EPSC before (black) and after (red) the addition of 20 μM (S)-EU1180–55. Right panel, normalized evoked NMDAR-mediated EPSC before (black) and after (red) the addition of 20 μM (S)-EU1180–55. (E, F) Effect of (S)-EU1180–55 on weighted tau and response amplitude (n = 8, red). (G–I) Similar data as in panels D–F but with DMSO vehicle (n = 8, green). See Supplemental Table S5 for summary of fitted parameters. *p < 0.025, paired t test.

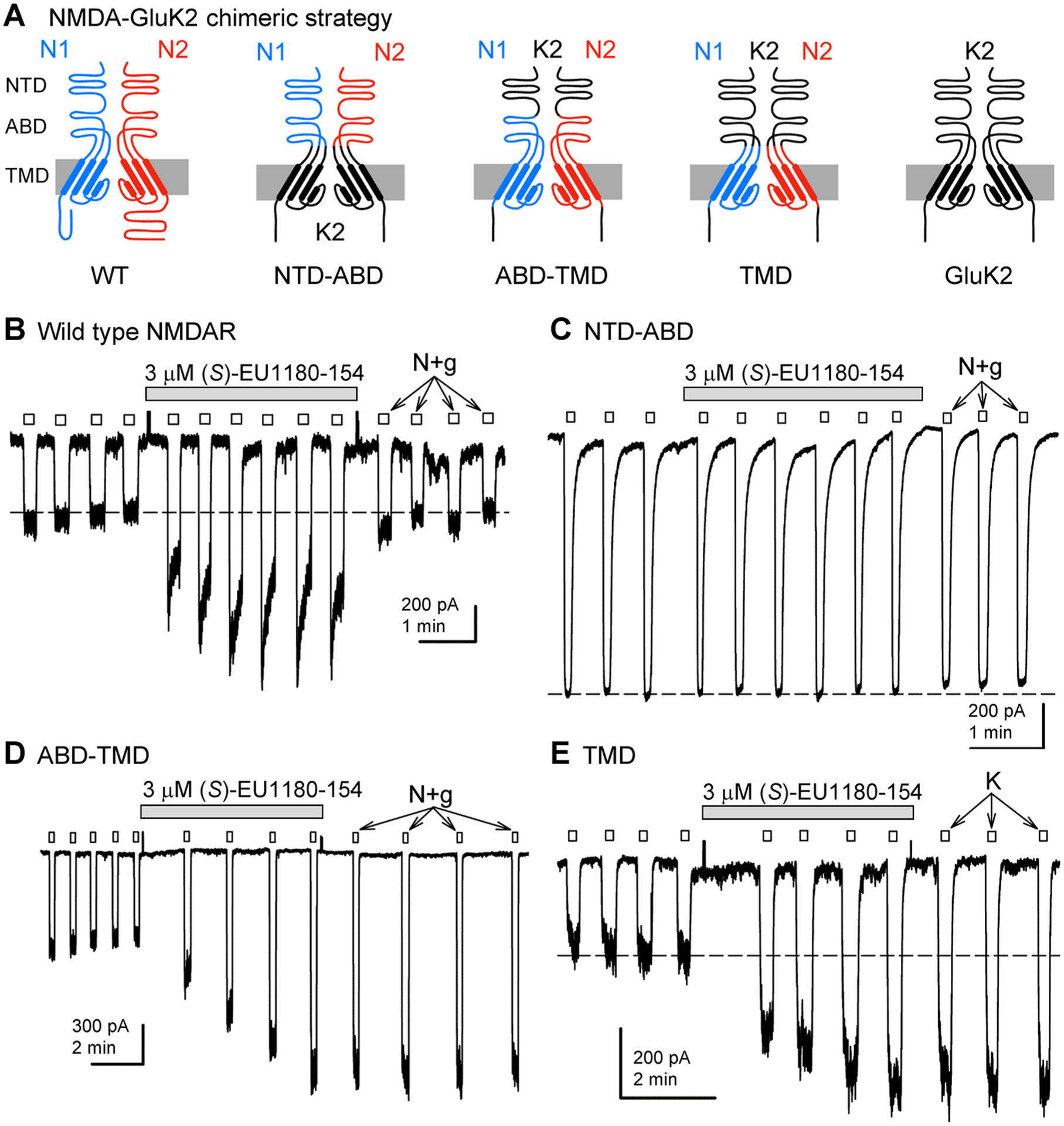

Activity of EU1180–55 Analogues is Dependent on the Transmembrane Domain.

We previously elucidated the structural determinants of action of CIQ using functional studies of GluN2A–GluN2D chimeric subunits,43 a strategy that exploited the lack of detectable effects of CIQ on GluN2A-containing NMDARs. However, the isopropoxy-based tetrahydroisoquinoline analogues show allosteric regulation of GluN1/GluN2A agonist potency, suggesting GluN1/GluN2A receptors harbor a binding site for these PAMs. The potential existence of a GluN1 or GluN2A binding site confounded the use of GluN2A/GluN2D chimeric receptors, prompting us to develop a different chimeric-based strategy to identify structural determinants of action for these compounds. We evaluated the effect of both racemic EU1180–55 and the potent and selective enantiomer (S)-EU1180–154 on current responses to homomeric GluK2 receptors, which can form functional chimeric subunits with GluN1 and GluN2 subunits.76 We found that both EU1180–55 and (S)-EU1180–154 potentiated GluN1/GluN2B receptor responses to 10 μM NMDA plus 10 μM glycine 1.5-fold in HEK cells (Figure 5, Table S6) but had no detectable effect on kainate-activated concanavalin-A-treated GluK2 receptors expressed in HEK cells (Supplemental Table S6, Supplemental Figure S6). To confirm we did not miss a subtle regulation of agonist potency at GluK2, we tested whether 10 μM (S)-EU1180–154 altered the response of GluK2(Q) to a submaximal concentrations of 3 μM glutamate. The submaximal response to 3 μM glutamate in (S)-EU1180–154 was 98% ± 1.4% of that observed in control (n = 8), confirming that this compound did not alter agonist potency or efficacy at GluK2 homomeric kainate receptors.

Figure 5.

(S)-EU1180–154 potentiation requires the NMDA receptor TMD. (A) Cartoon representations showing construction of chimeric subunits from GluK2/GluN1 and GluK2/GluN2B. (B–E) Whole-cell currents evoked by 10 μM NMDA and 10 μM glycine (N+g) or 10 μM kainate (K) to transfected HEK cells expressing chimeric receptors. (S)-EU1180–154 was applied as indicated by the gray bars. The effects of 3 μM (S)-EU1180–154 (mean, SEM, N) are summarized in Supplemental Table S6. The holding potential was −80 mV.

We subsequently utilized a series of chimeric NMDA–kainate receptors where various semiautonomous domains of GluN1 and GluN2B subunits were replaced with homologous segments from GluK2 (Figure 5A). These NMDA–kainate receptor chimeras have been previously used to identify structural determinants for allosteric modulators of NMDAR function. To evaluate the molecular determinants of action for isopropoxy-containing analogues at GluN2B, we evaluated the potentiation by both EU1180–55 and (S)-EU1180–154 of the response of GluN1-GluK2/GluN2B-GluK2 chimeric receptors. We tested systematic replacement of the GluN1 and GluN2B NTD, ABD, and transmembrane domain (TMD) with the corresponding region from GluK2 (Figure 5). For all experiments, potentiation by both EU1180–55 and (S)-EU1180–154 of GluK2-NMDA chimeric receptors tracked with the NMDA receptor transmembrane domain (Supplemental Table S6). For example, (S)-EU1180–154 potentiated chimeric NMDAR–kainate receptors that contained the NMDA receptor TMD and ABD (Figure 5D), as well as chimeric receptors that contained only NMDA subunit TMD regions (Figure 5E). Chimeric receptors composed of the NMDAR NTD and ABD regions but kainate receptor TMD regions for all four subunits77 were not potentiated by (S)-EU1180–154 (Figure 5), suggesting that the NMDAR TMD region is essential for potentiation of GluN1/GluN2B by the isopropoxy-containing tetrahydroisoquinoline compounds EU1180–55 and (S)-EU1180–154 (Supplemental Table S6).

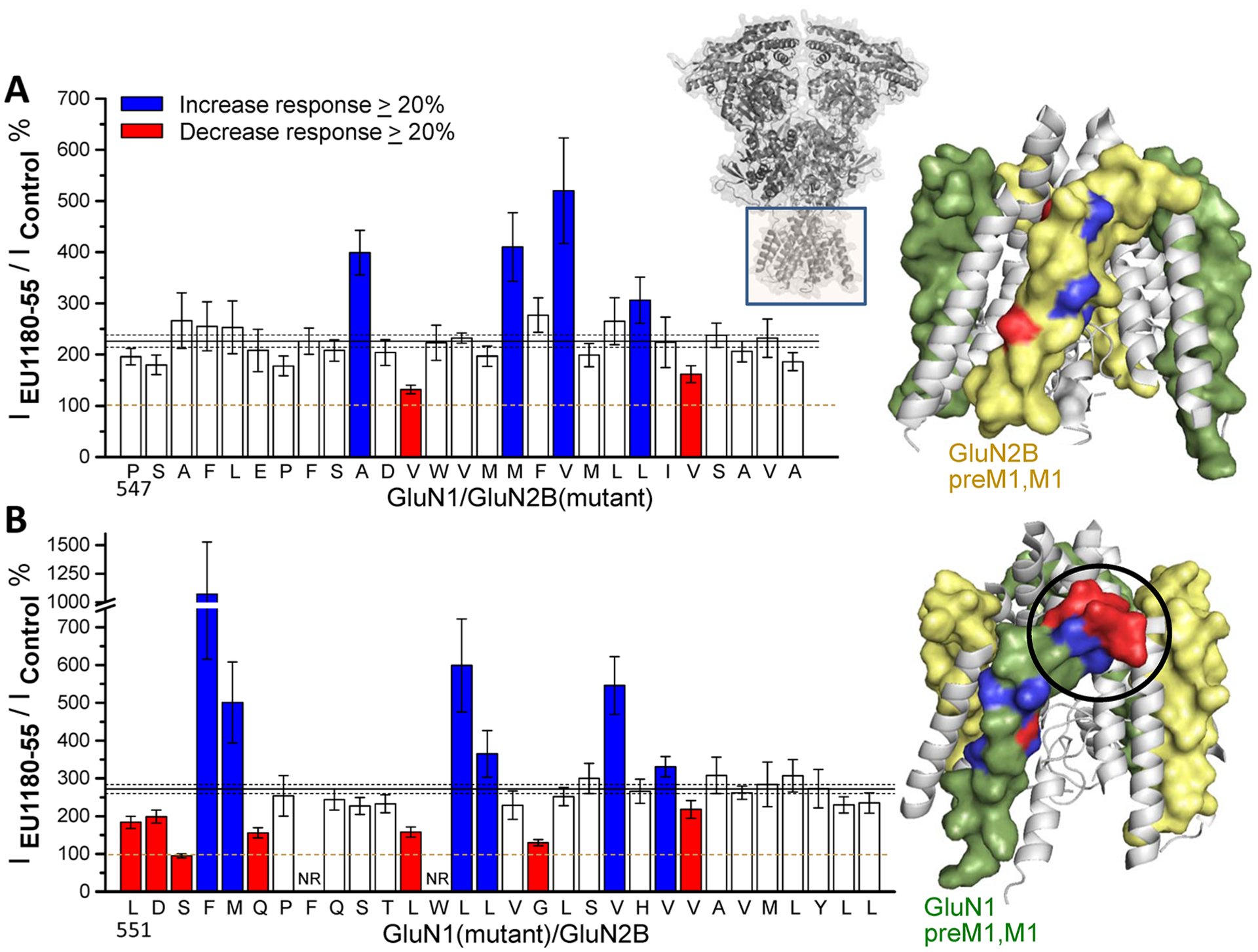

Molecular Determinants of (S)-EU1180–55 Analogues Reside in GluN1 Pre-M1 and M1 Helices.

The key molecular determinants of the actions of CIQ, determined through evaluation of GluN2A/GluN2D chimeric receptors, included the GluN2D M1 transmembrane domain and the linker region that harbors the short pre-M1 helix.43,78 Scanning mutagenesis identified residues that control the actions of CIQ within the GluN2D pre-M1 helix in addition to residues proximal to the extracellular end of the M1 transmembrane helix, largely along one side of the transmembrane helix. The experiments with chimeric GluK2-GluN1/GluN2B subunits are consistent with EU1180–55 acting at a site near pre-M1. Although CIQ and EU1180–55 are structurally similar, (S)-EU1180–55 shows distinct mechanisms and subunit selectivity compared to both CIQ and (R)-EU1180–55, raising the possibility that the two EU1180–55 enantiomers may have distinct structural determinants of action. To explore the potential site of action of (S)-EU1180–55, we used an alanine screen of the pre-M1 helix and the M1 transmembrane domain for GluN2B to look for mutations that disrupt the actions of racemic EU1180–55, which should identify structural determinants of action of (S)-EU1180–55 since only this enantiomer acts on GluN2B. We similarly tested whether (S)-EU1180–55 might interact with structural determinants in the GluN1 pre-M1 and M1 helices, given the conservation between these regions in GluN1 and GluN2.

Figure 6 summarizes the activity of racemic EU1180–55 on mutations within the GluN1 and GluN2 pre-M1 helix and the M1 transmembrane helices. Mutations at 6 of 27 residues scattered across the GluN2B pre-M1/M1 regions (A556C, V558A, M562A, V564A, L567A, V569A) shifted EU1180–55 activity by more than 20% from wild-type receptors recorded on the same day (Figure 6A), suggesting that no particular sites or regions of the GluN2B pre-M1 and M1 helices are primary structural determinants for the activity of EU1180–55. In contrast to results with GluN2B, 13 of 28 mutations that were clustered closely together in the GluN1 pre-M1/M1 region diminished or increased EU1180–55-mediated potentiation by more than 20% compared to same day wild-type controls. These GluN1 mutations were L551A, D552A, S553A, F554A, M555A, and Q556A in the pre-M1 helix and L562A, L564A, L565A, G567A, V572A, V573A, and V574A in the transmembrane M1 helix (Figure 6B). These data suggest that the pre-M1 and M1 regions within the GluN1 subunit harbor structural determinants of action for (S)-EU1180–55 on GluN1/GluN2B receptors, and that these residues may comprise a novel modulatory site within the GluN1 subunit. The potential presence of a modulatory site within the GluN1 subunit is consistent with several features of the EU1180–55 series of modulators. For example, the nonselective potentiation of GluN2B, GluN2C, and GluN2D by (S)-EU1180–55 together with allosteric regulation of glutamate potency at GluN2A, GluN2B, and GluN2C could be explained by structural determinants residing in GluN1, since all subtypes of NMDARs contain two GluN1 subunits. Furthermore, the sensitivity of EU1180–55 to alternative exon splicing in the GluN1 NTD might reflect GluN1 structural determinants of modulator activity.

Figure 6.

Structural determinants of EU1180–55 actions on GluN1/GluN2B reside in the preM1-M1 region of GluN1. (A) Response in the presence of modulator for GluN1 coexpressed with mutant GluN2B receptors in oocytes relative to the control response in the absence of modulator. (B) Response in the presence of modulator of mutant GluN1 coexpressed with GluN2B relative to the control response in the absence of modulator. Responses were activated by maximally effective concentrations of glutamate and glycine (100/30 μM). For all panels, solid and dashed lines show the mean ratio for WT receptors ±99% confidence intervals. Bars are colored when they diverged more than 20% from the mean response and had nonoverlapping confidence intervals. An alanine was substituted for each residue starting with GluN1 Leu551 and GluN2 Pro547, except when alanine was the original amino acid, in which case it was changed to a cysteine. Data are from 4 to 33 oocytes from 1 to 4 batches of oocytes. Error bars are 99% confidence intervals. Positions at which mutations altered the response to EU1180–55 are mapped onto a spacefill model of the pore forming region (GluN1 green, GluN2 yellow).

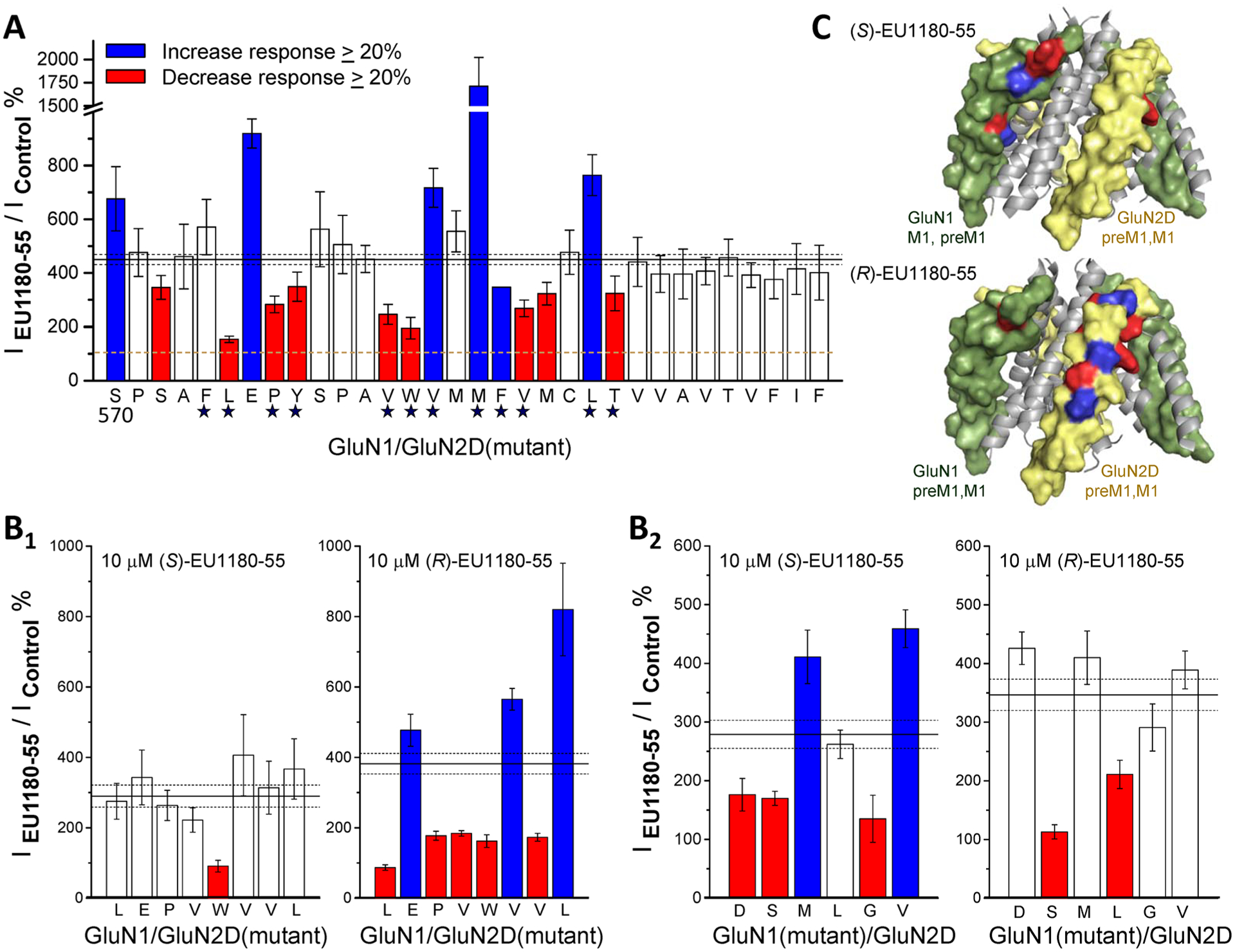

Given similar subunit selectivity to (+)-CIQ (predicted to be (R)44,79), the GluN2C/GluN2D-selective (R)-(+)-EU1180–55 seems likely to have structural determinants of action in GluN2C/GluN2D subunits, which is where (+)-CIQ has been proposed to act.78 We performed complementary experiments on GluN1/GluN2D receptors to determine whether the structural determinants of action of (S)-EU1180–55 and (R)-EU1180–55 resided within GluN1 or GluN2D subunit, respectively. We first evaluated the effects of mutations at all positions in GluN2D pre-M1 and M1 helix on the effects of racemic EU1180–55 and identified 15 residues at which substitution of an alanine reduced or enhanced the effect of racemic EU1180–55 by more than 20% with nonoverlapping 99% confidence intervals for wild-type receptors recorded on the same day (Figure 7A). We selected eight of these mutations within GluN2D to test the effects of (S)-EU1180–55 and (R)-EU1180–55 (Leu575, Glu576, Pro577, Val582, Trp583, Val584, Val588, and Leu591). The effects of (S)-EU1180–55 were altered in only 1 of 8 of these GluN2D mutations, whereas all 8 mutations altered (R)-EU1180–55 activity (Figure 7B1). Figure 7C shows the location of residues at which mutations altered response by more than 20% with nonoverlapping confidence intervals. These data suggest that GluN2D does not harbor structural determinants of (S)-EU1180–55 activity for GluN1/GluN2D receptors. By contrast, (R)-EU1180–55 appears to have structural determinants localized within GluN2D.

Figure 7.

Structural determinants of action for (S)-EU1180–55 and (R)-EU1180–55 on GluN1/GluN2D receptors. (A) Results of scanning mutagenesis on racemic 30 μM EU1180–55 modulation of the response to maximally effective glutamate and glycine (100/30 μM) for pre-M1 and M1 residues in GluN2D, starting at Ser570. Alanine was substituted at all residues, except when alanine was the original amino acid, in which case it was changed to a cysteine. Data are from 3 to 24 oocytes from 1 to 5 batches of oocytes for each mutation. The star below indicates residues in GluN2D at which mutations alter the actions of the positive allosteric modulator CIQ. (B) Quantitative evaluation was performed on the effects of 8 GluN2D mutations (B1, L575A, E576A, P577A, V582A, W583A, V584A, V588A, L591A) and 6 GluN1 mutations (B2, D552A, S553A, M555A, L562A, G567A, V570A) on 10 μM (S)-EU1180–55 or (R)-EU1180–55 potentiation. For all panels, the solid line shows the mean potentiation of WT GluN1/GluN2D recorded on the same day; dashed lines and error bars are the 99% confidence intervals. Bars are filled red when EU1180–55 reduced current by more than 20% and confidence intervals were nonoverlapping or blue when EU1180–55 enhanced the response by 20% and confidence intervals were nonoverlapping. Data are from 4 to 21 oocytes from 1 to 2 batches of oocytes for each mutation. (C) A model of the transmembrane domain of GluN1/GluN2D with pre-M1 and M1 helices represented as spacefill (GluN1 is green, GluN2 is yellow). Residues are colored to illustrate the actions of the two enantiomers tested at GluN1 and GluN2 mutations shown in panel B.

We subsequently assessed the sensitivity to allosteric modulation by the two EU1180–55 enantiomers for GluN1 mutations coexpressed with GluN2D. We selected six GluN1 residues at which mutagenesis altered the responses to racemic EU1180–55 (Asp552, Ser553, Met555, Leu562, Gly567, and Val570). We coexpressed these mutant GluN1 subunits with GluN2D and screened for differential effects of (S)- and (R)-EU1180–55. Five of these GluN1 residues altered (S)-EU1180– 55 actions on GluN1/GluN2D (Figure 6B2,C), whereas mutation at only two residues altered effects of (R)-EU1180–55. Taken together, these data are consistent with the idea that residues in GluN1 control the actions of (S)-EU1180–55 and residues in GluN2D determine the actions of (R)-EU1180–55 at GluN1/GluN2D receptors.

Modeling of (S)- and (R)-EU1180–55 Binding to GluN1/GluN2D Receptors.

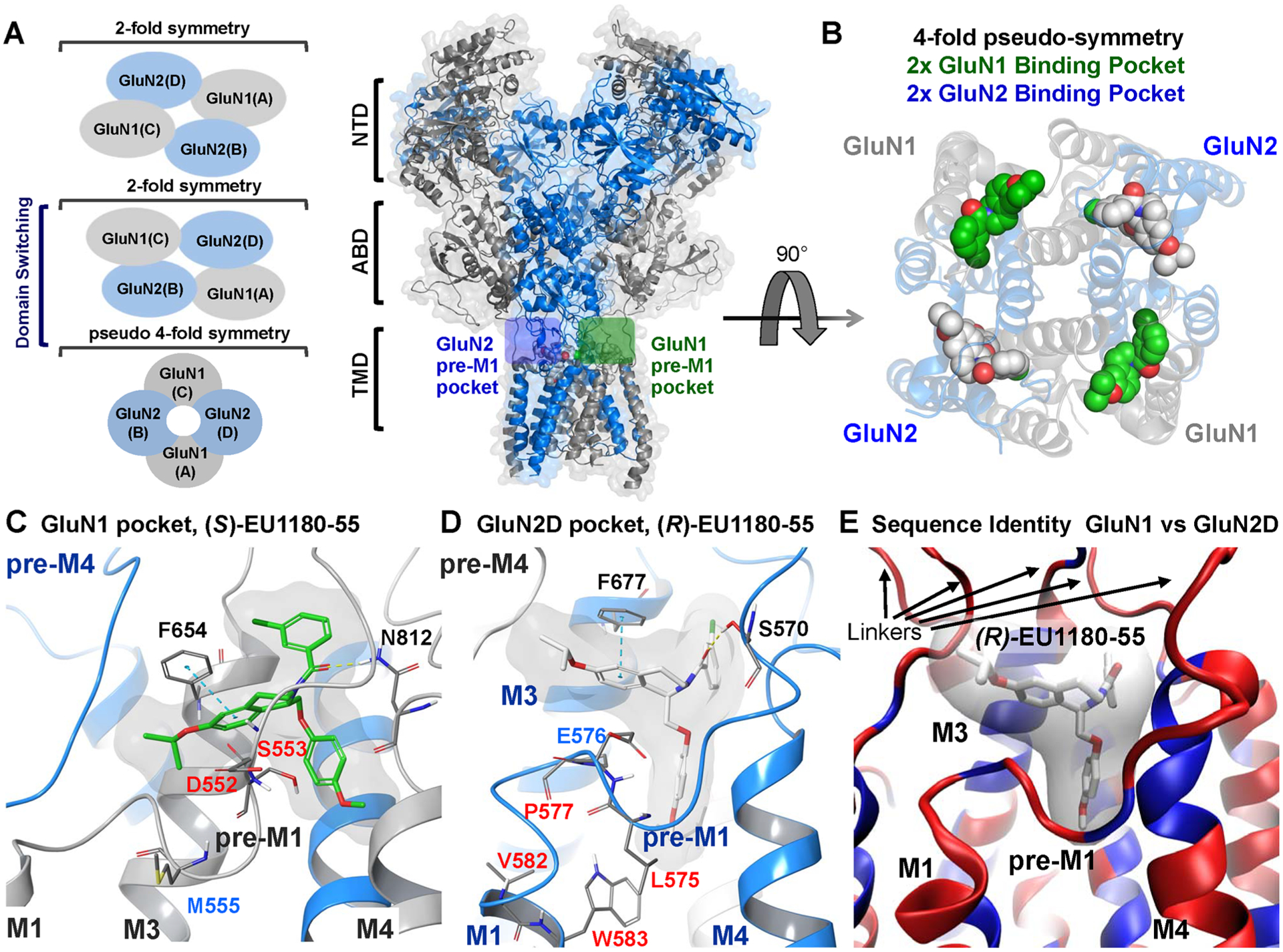

To evaluate the two pockets involving the GluN1 pre-M1 and GluN2 pre-M1 domains, we built models of both the GluN1/GluN2B and GluN1/GluN2D from published crystal structures, modeling all missing residues and side chains (models are provided in Supporting Information80). Figure 8 illustrates the 2-fold symmetry in both the NTD and ABD domains and the pseudo-4-fold symmetry in the transmembrane region10 (Figure 8A). The pseudo-4-fold symmetry of the transmembrane region is a result of the NMDAR subunit composition of 2 subunits (GluN1/GluN2), in contrast to the homomeric GluA2 AMPA receptor comprising 4 identical subunits, which demonstrates a true 4-fold symmetry. Therefore, whereas the NMDARs can form 4 binding pockets in the transmembrane region, two distinct pairs of binding pockets will exist due to sequence differences between GluN1 and GluN2, and these different sites could be occupied by different ligands or their enantiomers (Figure 8B). The NMDAR transmembrane region has been poorly resolved, with only one structure having resolution of the linker region.80 We used an apo-state (containing no ligands) NMDAR structure80 to generate homology models followed by molecular docking; however we were unable to obtain binding poses that are consistent with the structure–activity relationship of our compound series. The poorly resolved binding pockets in the apo-state introduce a high degree of uncertainty when attempting to elucidate ligand–receptor complexes.42 To mitigate this uncertainty, we used the transmembrane region of an AMPA receptor (PDB 5L1G) to generate homology models that contained GYKI 53655 (a noncompetitive AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist), which helped to shape the pre-M1 pocket of interest to better accommodate ligands. Not only does GYKI 53655 share structural features with EU1180–55, but site-directed mutagenesis puts the structural determinants of EU1180–55 (Figures 6 and 7) within an equivalent pre-M1 region of the AMPAR (Figure 8 and Supplemental Figure S781).

Figure 8.

(A) Cartoon representation of a GluN1/GluN2D NMDAR homology model bound with EU1180–55 enantiomers in the GluN1 (green box) and GluN2 (blue box) pre-M1 pockets. Blue represents the GluN2 subunits and gray the GluN1 subunits. (left) Representation of the fold symmetry in the NMDAR of the NTD, ABD, and TMD. (B) Rotation (90°) and removal of the ABD and NTD reveals the pseudo-4-fold symmetry of the transmembrane region with the (S) and (R) enantiomers of EU1180–55 bound. Green shows the (S)-EU1180–55 enantiomer, which mutagenesis suggests binds to a pocket on GluN1. White shows (R)-EU1180–55 bound to the analogous pocket on GluN2. (C, D) Expanded view of (S)-EU1180–55 (green) within the GluN1 binding pocket and (R)-EU1180–55 (white) bound within a pocket on GluN2D. If residues were tested in either Figure 6 or 7, the residues numbers are colored using the color scheme in Figures 6 and 7. (E) Overlay of the GluN1 and GluN2D binding pockets with blue showing identical residues and red showing nonidentical residues; only a single ribbon is shown. The binding pocket is conserved with most of the variation within pre-M1 and the linker region between the TMD and the ABD. See Supplemental Figure S8 for more information.

We tested 100 μM GYKI 53655 for activity against the recombinant NMDARs and found no detectable effect on GluN1/GluN2A (104% ± 1.2% of control, n = 6) or GluN1/GluN2B (107% ± 8.6% of control, n = 6) activated by 100 μM glutamate and 30 μM glycine. GYKI 53655 inhibited GluN1/GluN2C (IC50 143 μM, n = 8) and GluN1/GluN2D (IC50 133 μM, n = 8), suggesting that GYKI 53655 has some GluN2C/D-selective actions, and thus, the structure of GYKI 53655 bound to GluA2 is a reasonable starting point for modeling a shared binding pocket. Assuming a similar binding pocket and mode between GYKI 53655 and EU1180–55, we performed a molecular overlay of these compounds. The (S)-EU1180–55 enantiomer was overlaid with GYKI 53655 within the GluN1 pre-M1 pocket. Similarly, the (R)-EU1180–55 enantiomer was overlaid with GYKI 53655 within the GluN2D pre-M1 pocket (Supplemental Figure S7). The GYKI 53655 compounds were replaced by the EU1180–55 enantiomers within the NMDAR followed by energy minimization to relieve unfavorable interactions (Supplemental Figure S7). To decrease computational time, the NTD of each model was removed prior to MD simulations.82 The resulting protein–ligand complex was placed in a membrane and solvated followed by a 2 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. From this simulation, we selected the last frame to propose the potential binding poses of EU1180–55 in the NMDAR and its interactions (Figure 8C,D; the pdb structure is provided in the Supporting Information).

Both the GluN1 and GluN2 pre-M1 pockets showed a hydrophobic character, with residues being contributed from 2 different subunits highlighted by the different color ribbons. The GluN1 pocket is formed by GluN1 pre-M1 and GluN1 M3 (gray) plus GluN2 pre-M4 (blue); the GluN2 pocket is formed by GluN2 pre-M1 and GluN2 M3 (blue) plus GluN1 pre-M4 (gray, Figure 8C,D).83 The tetrahydroisoquinoline of both enantiomers forms a π–π stacking interaction with equivalent phenylalanine residues in both the GluN1 (Phe654) and GluN2D (Phe677) pockets. Hydrogen bonds were observed between the carbonyl group of the EU1180–55 enantiomers and residues Asn812 (GluN1; Figure 7C) and Ser570 (GluN2D; Figure 7D) in the GluN1 and GluN2D pockets, respectively. The mutation GluN1-F654A reduced the potentiation of GluN1/GluN2B responses by (S)-(−)-EU1180–55 from 198% ± 12.9% (n = 10) of control for wild-type to 137% ± 7.0% of control (n = 9, p < 0.001). Mutations at other residues forming the GluN1 pocket (Asp552, Ser553; Figures 6B and 8C) also perturbed the potentiation by (S)-(−)-EU1180–55. Similarly, mutation of residues lining the GluN2D pocket (Glu576, Pro577, Leu 575, Ser570; Figures 7 and 8D) perturbed the actions of (R)-(+)-EU1180–55. These data are consistent with the poses obtained from modeling. From the molecular dynamics simulations, we observed that the EU1180–55 enantiomers adopt slightly different orientations and conformations within the respective binding pockets, with the tetrahydroisoquinoline tilting upward (Figure 8C,D), which might contribute to the subunit selectivity. We hypothesize that the elimination of the 6-methoxy (which faces NMDAR pore or M3 helix) on the tetrahydroisoquinoline allows for the tilting of the ring system and the accommodation within in the pre-M1 GluN2D pocket. Moreover, the replacement of the 7-methoxy (which faces away from the NMDAR pore) with an isopropoxy provides some additional interactions to stabilize the (R)-EU1180–55 enantiomer within the pocket.

We subsequently evaluated the similarity between the GluN1 and GluN2D pre-M1 pockets by overlaying them in Cartesian space and coloring the ribbon by sequence identity (Figure 8E; only one pocket is displayed). The core of the binding pocket is nearly identical, whereas the surrounding linker regions that connect the transmembrane region and ABD are variable, suggesting that enantiomeric selectivity may reside within these regions (Figure 8E, see Supplemental Figure S8 for further detail). Moreover, we observed different orientations in the linkers connecting the M3 helixes and the ABD for the GluN1 and GluN2 pockets. However, we cannot draw conclusions from this observation since no data exists describing the changes the linkers undergo upon agonist binding. Given the pseudo-4-fold symmetry and conserved nature of the residues forming the GluN1 and GluN2 pre-M1 binding pockets (Figure 8E), it is possible that subunit selectivity reflects the subtle changes between the binding pockets that drive the accommodation of the different enantiomers. Finally, we acknowledge the limitations of these techniques and template structure resolution and therefore caution readers not to extract detailed interactions, which can only be resolved with high-resolution structural data. With these caveats in mind, the proposed binding poses suggest future experiments to explore the mode of action of the EU1180–55 scaffolds and are consistent with mutagenesis data suggesting subunit selectivity arises from enantiomeric selectivity for separate GluN1 and GluN2 pockets.

CONCLUSIONS

The most important finding of this study is that there are two separate but structurally similar modulatory sites on homologous linker regions of the GluN1 or GluN2 subunits of the NMDAR. These sites likely involve the pre-M1 helix, a portion of the M1 helix, the highly conserved M3 domain, and possibly the pre-M4 linker of the adjacent subunit. These regions have been implicated as a site of action for multiple other PAMs, making this finding of broad interest.45–47 These modulatory sites show unique selectivity for positive allosteric modulators, and agents acting at these two sites show unique mechanisms of action. Furthermore, while the two sites can recognize similar molecules (e.g., enantiomers in this study), they could be exploited for development of new modulators with different subunit selectivity. The existence of these similar modulatory sites could confound drug discovery efforts if assays are not designed to adequately distinguish between the actions of compounds at each site. This would occur if each site had a unique SAR, but series under investigation (like the tetrahydroisoquinolines studied here) had differential activity at both sites. The existence of these two sites further suggests that the GluN1 and GluN2 subunits near the pre-M1 and M3 gating-control regions have a distinct structure and contribute differently to opening of the pore. The GluN1 pre-M1 site appears active in neurons and can influence the agonist potency, the maximal response, and the deactivation time course following removal of glutamate at GluN2A and GluN2B receptors expressed in principal cells. The GluN1 site also seems capable of potentiating NMDARs that contain GluN2C or GluN2D. By contrast, the GluN2 site shows strong actions on GluN2C- or GluN2D-containing NMDARs, with modest effects on GluN2A- and GluN2B-containing NMDARs. The actions of GluN2 modulators have minimal effects on agonist potency or response time course, although this may not be the case for more efficacious analogues.

METHODS

All work involving the use of animals was conducted according to the guidelines of Emory University, and all procedures were approved by the Emory University IACUC and were performed in accordance with state and federal Animal Welfare Acts and the policies of the Public Health Service. All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), with the exception of the EU1180–55 derivatives, which were synthesized and separated into enantiomers as described by Strong and colleagues.69

Molecular Biology.

The cDNAs encoding rat GluN1–1a (lacking exon5, hereafter GluN1) and GluN1–1b (including exon5, GenBank accession numbers U11418, U08261), GluN2A (D13211), GluN2B (U11419), GluN2C (M91563), and GluN2D (L31611) were provided by Drs. S. Heinemann (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA), S. Nakanishi (Osaka Bioscience Institute, Osaka, Japan), and P. Seeburg (Max Planck Institute for Medical Research, Heidelberg, Germany). Site-directed mutagenesis was accomplished using the QuikChange strategy (Agilent Technologies). The amino acids are numbered according to the full-length protein, including the signal peptide (the initiating methionine is 1). For synthesis of cRNA in vitro, cDNA constructs were linearized with restriction enzymes, purified using QIAquick purification kit (Qiagen, Germantown MD), and used for in vitro transcription according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (mMessage mMachine, Ambion, Austin, TX).

The cDNA constructs that enable control of subunit stoichiometry were generated using rat GluN2A with modified C-terminal peptide tags encoding coiled-coil domains and an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention signal, as previously described.62 Briefly, two peptides comprising a synthetic helix, the leucine zipper motifs from GABAB1 (referred to as C1) or GABAB2 (referred to as C2), and a di-lysine KKTN ER retention signal were inserted in frame in place of the stop codon of GluN2A to yield GluN2AC1 and GluN2AC2.62,84–86 Only receptors with one copy of a C1 tag and one copy of a C2 tag will mask the ER retention signal and reach the cell surface, allowing control of the expression of triheteromeric receptors that contained two different GluN2 subunits.62 The C-terminal domain of the GluN2B, GluN2C, and GluN2D subunit (residues following position 838 for GluN2B, position 837 for GluN2C, and 862 for GluN2D) were replaced by the modified C-terminal domain of GluN2AC1 or GluN2AC2 (residues following position 837 in GluN2A). We introduced two mutations into the glutamate binding site (referred to as RK/TI) of each GluN2 subunit (GluN2A-R518K,T690I; GluN2B-R519K,T691I; GluN2C-R529K,T701I; GluN2D-R543K,T715I) to allow a determination of the magnitude of the escape current, which is a measure of the ability of the ER retention signal to prevent trafficking to the plasma membrane of receptors that contain either two C1-tagged GluN2 subunits or two C2-tagged GluN2 subunits. C1–C1- or C2–C2-containing receptors will give rise to the current response when the other subunit harbors the RK/TI mutations.87 Chimeric subunits were generated from rat cDNAs by restriction enzyme-free PCR cloning37 or by ligation of PCR products with novel restriction sites inserted by silent mutations.76,77 All constructs were verified by sequencing. Wild-type and modified GluN2 cDNAs were subcloned into pCI-neo (Promega, Madison, WI) and used for in vitro cRNA for expression in Xenopus oocytes. GluN1 was subcloned into pGEM-HE.

Two Electrode Voltage Clamp Recording from Xenopus Oocytes.

Defolliculated Xenopus laevis oocytes (stage V–VI) were obtained from Ecocyte BioScience (Austin, TX) and injected with cRNAs encoding wild-type GluN1 and GluN2 at a 1:2 ratio in 50 nL (0.2–10 ng of total cRNA). The cRNA was diluted with RNase-free water to give responses with amplitudes ranging between 200 and 2000 nA. Following cRNA injection, the oocytes were stored at 15 °C in Barth’s solution that contained (in mM) 88 NaCl, 2.4 NaHCO3, 1 KCl, 0.33 Ca(NO3)2, 0.41 CaCl2, 0.82 MgSO4, 5 HEPES, pH 7.4 with NaOH, supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 100 μg/mL gentamicin (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). For all triheteromeric receptors, oocytes were incubated at 19 °C, except GluN1/GluN2BC1/GluN2DC2 and GluN1/GluN2AC1/GluN2DC2, which were first incubated at 15 °C for 1–2 h and then at 19 °C until recording.

Recordings were performed 2–5 days following cRNA micro-injection at room temperature (23 °C) using a two-electrode voltage-clamp amplifier (OC725, Warner Instrument, Hamilton, CT) to measure current responses to 100 μM glutamate and 30 μM glycine, unless otherwise stated. The signal was low-pass filtered at 10–20 Hz (4-pole, −3 dB Bessel; Frequency Devices, Haverhill, MD) and digitized at the Nyquist rate using PCI-6025E or USB-6212 BNC data acquisition boards (National Instruments, Austin, TX). Oocytes were placed in a custom-made chamber and continuously perfused (~2.5 mL/min) with oocyte recording solution containing (in mM) 90 NaCl, 1 KCl, 10 HEPES, 0.5 BaCl2, 0.01 EDTA (pH 7.4 with NaOH). Solutions were applied by gravity, and solution exchange was controlled through a digital 8-modular valve positioner (Hamilton, Reno, NV). Recording electrodes were filled with 0.3–3.0 M KCl, and current responses were recorded at a holding potential of −40 mV. Data acquisition, voltage control, and solution exchange were controlled by custom software.

Triheteromeric NMDAR expression was achieved by injecting into oocytes varying amounts of cRNA in 50 nL of water. Injections for GluN1/GluN2AC1/GluN2CC2 were performed as described by Bhattacharya et al.67 Injections for GluN1/GluN2AC1/GluN2BC2 were performed as described by Hansen et al.62 Injections for GluN1/GluN2BC1/GluN2CC2 were performed as described by Bhattacharya et al.67 and Kaiser et al.42 Injections for GluN1/GluN2BC1/GluN2DC2 were performed as described by Yi et al.88 GluN1/GluN2AC1/GluN2DC2 cRNAs were co-injected at ratio of 1:1:4 (total cRNA was 1.5 ng in 50 nL of RNase free water). For all triheteromeric experiments, the cRNA ratios for injection for the RK+TI mutations and diheteromeric controls matched that of the triheteromeric construct. Recordings from oocytes expressing triheteromeric receptors were performed in the presence of 5 mM 2-hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin (BCD) in oocyte recording solution. On average, coexpression of GluN1/GluN2AC1/GluN2BC2 showed a summed escape current less than 7%, coexpression of GluN1/GluN2AC1/GluN2CC2 showed a summed escape current of less than 10%, coexpression of GluN1/GluN2AC1/GluN2DC2 showed a summed escape current of less than 9%, coexpression of GluN1/GluN2BC1/GluN2CC2 showed a summed escape current of less than 8%, and coexpression of GluN1/GluN2BC1/GluN2DC2 showed a summed escape current of less than 10%.

Whole Cell Patch Clamp Recordings from HEK293 Cells.

HEK293 cells (CRL 1573, ATCC, Rockville, MD) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with GlutaMax-I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum, 10 U/mL penicillin, and 10 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 95% O2/5% CO2. HEK cells were plated in 24-well plates on 5 mm glass coverslips (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) coated with 10–100 μg/mL poly(d-lysine). Cells were transfected with GluN1, GluN2, and GFP in plasmids at a ratio of 1:1:1 using the calcium phosphate method.89 Briefly, 10 μL of plasmid DNA in water (0.2 μg/μL; total 2 μg of DNA) was mixed with 65 μL of H2O and 25 μL of 1 M CaCl2, and this mixture added to 100 μL of 2× BES solution composed of (in mM) 50 N,N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid, 280 NaCl, and 1.5 Na2HPO4 (adjusted to pH 6.95 with NaOH). After 3–5 min, 50 μL of the resulting solution was added dropwise to each of four wells of a 24-well plate containing HEK cells and 0.5 mL of DMEM. The culture medium containing the transfection mixture was replaced after 6 h with DMEM supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, and the NMDAR antagonists d,l-2-amino-5-phosphonovalerate (200 μM) and 7-chlorokynurenate (200 μM). Experiments were performed 12–24 h post-transfection.

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were made at a holding potential of −60 mV at room temperature (23 °C) using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA). The signal was low-pass filtered at 4–8 kHz (−3 dB, 8-pole Bessel; Frequency Devices, Haverhill, MD) and digitized using Digidata 1322A or 1440A (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA) at 40 kHz with Clampex software (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA). Recording electrodes (3–4 MΩ) were fabricated from filament-containing thin-walled glass micropipettes (TW150F-4; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) pulled by a horizontal puller (P-1000, Sutter Instrument Company, Novato, CA). The electrodes were filled with internal solution that contained (in mM) 110 d-gluconic acid, 110 CsOH, 30 CsCl, 5 HEPES, 4 NaCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 5 BAPTA, 2 NaATP, and 0.3 NaGTP (pH 7.35 with CsOH). The extracellular recording solution contained (in mM) 150 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 3 KCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 0.01 EDTA, 20 d-mannitol (adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH). Rapid solution exchange was accomplished through a two-barrel theta-glass capillary controlled by a piezoelectric translator (Burleigh Instruments, Fishers, NY). Open tip junction currents between undiluted and diluted (1:2 in water) extracellular recording solution were used to estimate speed of solution exchange at the tip, which had 10–90% rise times of 0.4–0.8 ms. The whole cell current was typically recorded in response to the addition of 100–1000 μM glutamate plus 30 μM glycine, with 30 μM glycine present in the wash solution. EU1180–55-containing solutions were made from 20 mM DMSO stock solution (final DMSO 0.05–0.15%), which was added to both bath and glutamate/glycine solution with rapid stirring.

Whole Cell Patch Clamp Recordings from Hippocampal Neurons.

Hippocampal cultures were prepared and maintained as previously described.45 Horizontal hippocampal brain slices (300 μm) were made from C57Bl/6 mice (postnatal day 7–14) of both sexes using a vibratome (TPI, St. Louis, MO). During preparation, the slices were bathed in an ice-cold (0–2 °C) partial sucrose-based artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF) that contained (in mM) 75 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 10 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 20 glucose, and 70 sucrose and bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. After preparation, slices were transferred to a NaCl-based aCSF that contained (in mM) 130 NaCl, 24 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 5 MgCl2, and 0.5 CaCl2 saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2. Slices were incubated at 34 °C for 30 min before returning them to room temperature, where they were left to recover for at least 1 h prior to use.

Evoked CA1 pyramidal cell EPSC recordings were made in the same NaCl-based aCSF mentioned previously, but with 0.2 mM MgCl2 and 1.5 mM CaCl2. Bath temperature was maintained at 30–32 °C throughout the experiment using an in-line solution heater and a bath chamber heating element (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). Thin-walled borosilicate glass (1.5 mm outer, 1.12 mm inner diameter; WPI Inc., Sarasota, FL) was used to fabricate recording electrodes (4–6 MΩ), which were filled with (in mM) 100 cesium gluconate, 5 CsCl, 0.6 EGTA, 5 BAPTA, 5 MgCl2, 8 NaCl, 2 Na-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP, 40 HEPES, 5 sodium phosphocreatine, and 3 QX-314. Monosynaptic release of glutamate was evoked using a monopolar tungsten-stimulating electrode by injecting 50–150 μA of current for 0.1 ms along the Schaffer collateral pathway. After whole-cell recording was achieved, CA1 pyramidal cells were held at −30 mV to minimize Mg2+ block of NMDARs. The Schaffer collaterals were stimulated every 20 s, and the NMDAR-mediated component of the EPSC was isolated via bath application of 10 μM 2,3-dioxo-6-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo[f]quinoxaline-7-sulfonamide (NBQX; AMPAR antagonist) and 10 μM gabazine (GABAAR antagonist). Cells were held at −30 mV in the presence of 10 μM NBQX and 10 μM gabazine for 10 min before baseline current responses were recorded. (S)-EU1180–55 (20 μM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) was washed onto the slice for 10 min before current responses were obtained. All recordings were finished in 200 μM DL-APV to ensure responses were mediated via NMDARs. The experimenter was blinded to whether compound or vehicle was being applied during all experiments and analysis. Recordings were made using an Axopatch 1D amplifier (Molecular Devices), filtered at 5 kHz using an eight-pole Bessel filter (−3 dB; Frequency Devices), and digitized at 20 kHz using a Digidata 1440a controlled by Axon pClamp10 software. Series resistance was monitored throughout the experiment and was typically 8–20 MΩ. If the series resistance changed >20% during the experiment, then the cell was excluded.

Data Analysis.

The macroscopic response time course of NMDAR responses was analyzed using Clampex (Molecular Devices) or custom software. When current responses were large (e.g., >500 pA), we corrected off line for series resistance filtering.90 The rise time of the response was assessed as the time it takes the current to rise from 10% to 90% of the peak response. The desensitization and deactivation time course was fitted (least-squares criteria) by the sum of two exponential components according to

| (1) |

where amplitudeFAST and amplitudeSLOW are amplitudes of the fast and slow components and tauFAST and tauSLOW are the time constants describing the fast and slow components, respectively. For some responses, amplitudeSLOW was 0. The weighted tau (τW) was calculated by

| (2) |

Concentration–response data for agonist activation of individual oocytes were fitted (least-squares criteria) by

| (3) |

where Imax is the maximum current in response to the agonist, nH is the Hill slope, [A] is the agonist concentration, and EC50 is the agonist concentration that produces a half-maximal response. Concentration–response data for EU1180–55 potentiation of individual oocytes were fitted (least-squares criteria) by

| (4) |

where maximum is the response in a saturating concentration of modulator, nH is the Hill slope, and EC50 is the agonist concentration that produces half-maximal potentiation. For graphical presentation, data points from individual oocytes were normalized to the current response to saturating glutamate plus glycine or modulator in the same recording and averaged.

Molecular Modeling.

A homology model of human GluN1/GluN2B diheterotetrameric model was generated with all side chains built from a nonactive conformation GluN1/GluN2B crystal structure (PDB ID 6WHS, 3.6 Å80). A human GluN1/GluN2D diheterotetrameric model was generated with all side chains built from a nonactive conformation GluN1/GluN2B cryo-EM structure (PDB ID 6WHS, 3.6 Å80) and the TMD of the GluA2 crystal structure (residues 506–544, 573–588, 595–634, 779–816) containing GYKI 53655 (PDB ID 5L1G, 4.52 Å resolution81). We then performed sequence alignments between the GluN2A–D and template sequences using Multiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation.81,91 The Uniprot numbers for the human sequences used are Q05586, Q12879, Q13224, Q14957, and Q17399. Ten homology models were generated for each of the two target models (GluN1/GluN2B and GluN1/GluN2D with GYKI 53655) using Modeller v9.24,92 from which the lowest energy model was selected and subjected to quality analysis using the PDBsum generator.93 The Ramachandran plots for all models are provided in Supplemental Figure S9. The Ramachandran plot statistics for all models were similar to the template structures, indicative good quality models. The selected model structures are provided as Supporting Information. Protein assessment and optimization was done by adding hydrogens followed by optimization and visual inspection. All titratable residues were assigned their dominant protonation state at pH 7.0 (Schrödinger Release 2020–1; Protein Preparation Wizard; Epik version 3.7; Impact version 7.2; Prime version 4.5, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2020). Energy minimization was performed to relieve unfavorable interactions. The minimization process first involved minimizing only hydrogen atoms followed by a restrained minimization using imperf with a convergence of the RMSD of heavy atoms set to 0.3 Å. The EU1180–55 enantiomers were aligned to GYKI 53655 using the Ligand Alignment module with the common scaffold set to Largest common Bemis-Murcko Scaffold within the Schrödinger 2020–1 release (Supplemental Figure S7). The (S)- and (R)-EU1180–55 enantiomers were aligned with the respective GYKI 53655 compounds resolved in equivalent GluN1 and GluN2D pockets. The GYKI 53655 molecules were replaced by the EU1180–55 molecules and subjected to minimization using imperf with a convergence of the RMSD of heavy atoms set to 0.3 Å. For clarity, numbering shown for all mutations, models, and figures is for rat GluN1, GluN2B, and GluN2D. The human amino acid sequence throughout the extracellular and membrane spanning domains is identical for GluN1 and GluN2B; however the human GluN2D pdb models (Supporting Information) include three additional residues that are present in human GluN2D (Gly39, Gly40, Pro41) but absent in rat GluN2D.

Molecular Dynamics.

To decrease computational time of the molecular dynamics simulations, we truncated the NTDs by removing residues up to residue 393 for the GluN1 and up to residue 427 for the GluN2D, as previously done.82 The truncated receptor was inserted into an equilibrated palmitoyl oleoylphosphatidyl choline (POPC) bilayer using the OPM model as visual guide.94 The system was solvated with a simple point charge (SPC) water model with a 150 mM NaCl concentration resulting in a total of 253 826 atoms with 1711 amino acids. The solvation box included a 10 Å buffer between the protein and periodic boundary. The system was then minimized for 100 ps using the Desmond Minimization protocol (for details, see Desmond manual; Desmond Molecular Dynamics System, D. E. Shaw Research, New York, NY, 2020). The MD simulation was performed using the OPLS 2005 force field (Desmond Molecular Dynamics System, D. E. Shaw Research, New York, NY, 2020) at a constant temperature of 300 K and pressure of 1.013 bar with particle mesh Ewald electrostatics using a 9 Å cutoff for each system for 2 ns. Time-step calculations were performed every 2 fs, and frames were captured every 4.8 ps. Analysis of the molecular dynamics trajectory was performed in Desmond, and the backbone RMSD is plotted in Supplemental Figure S10. The end structure of the MD simulation was selected and subjected to a 100 ps minimization from which the binding modes of the EU1180–55 enantiomers residing within their respective binding pockets in the diheterotetrametric GluN1/GluN2D NMDAR were proposed. We provide the structure of the protein and ligands as the Supporting Information.

Statistics.

Data were statistically compared by ANOVA with appropriate post hoc test and paired or unpaired t test, as appropriate. When multiple parameters were obtained from the same current responses (e.g., desensitization tau, response amplitude), we performed the Holm–Bonferroni correction to control for the family wise error rate. The log EC50 values were compared using t test or ANOVA and are reported ± the 95% confidence interval. Error bars are SEM or confidence intervals, as indicated. The power to detect a given effect size was determined using G-power 3.1.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sukhan Kim for excellent technical assistance. We also thank the Emory University Chemical Biology Discover Center for their assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by the NINDS (NS NS065371, NS111619 to S.F.T.; NS30888 to J.E.H.; GM103546, NS097536 to K.B.H.) and a research grant from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (S.F.T.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00561.

Model structures used in this study (ZIP)