Abstract

Background:

Exposure to phthalates is ubiquitous across the United States. While phthalates have antiandrogenic effects in men, there is little research on their potential impacts on sex hormone concentrations in women and that also take into account menopausal status.

Methods:

Cross-sectional data on urinary phthalate metabolites, serum sex hormones, and relevant covariates were obtained from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013–14 and 2015–16. Women over the age of 20 who were not pregnant or breastfeeding and had not undergone oophorectomy were included (n=698 premenopausal, n=557 postmenopausal). Weighted multivariable linear and Tobit regression models stratified by menopausal status were fit with natural log-transformed phthalate concentrations and sex hormone outcomes adjusting for relevant covariates.

Results:

Phthalate metabolites were associated with differences in sex hormone concentrations among postmenopausal women only. Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) was associated with lower serum estradiol and bioavailable testosterone concentrations. Specifically, a doubling of DEHP concentrations was associated with 5.9% (95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.2%, 11.3%) lower estradiol and 6.2% (95% CI: 0.0%, 12.1%) lower bioavailable testosterone concentrations. In contrast, 1,2-cyclohexane dicarboxylic acid di-isononyl ester (DINCH) was associated with higher free testosterone, bioavailable testosterone, and free androgen index. Finally, di-2-ethylhexyl terephthalate (DEHTP) was associated with a higher testosterone-to-estradiol ratio. None of these results retained statistical significance when adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Conclusions:

DEHP, DINCH, and DEHTP were associated with differences in serum sex hormone concentrations among postmenopausal women, highlighting the need for further research into the safety of these chemicals.

Keywords: plasticizer, menopause, reproductive health, endocrine disrupting chemical

1. Introduction

Phthalates are a group of chemicals used as plasticizers and fragrance enhancers in the manufacturing of products ranging from food packaging to cosmetics (National Research Council, 2008). Due to the multitude of applications of these chemicals, exposure to phthalates is now ubiquitous among Americans (Chiang et al., 2017). One approach to classifying phthalates is by molecular weight that corresponds to product use, with low molecular weight (LMW) phthalates utilized in cosmetics, personal care products, and fragrances and high molecular weight (HMW) phthalates employed in the production of food containers and packaging, building materials, soft plastic tubing, and vinyl flooring (National Research Council, 2008).

Phthalates have been shown to interfere with the normal functioning of hormones in both animals and humans, thus classifying them as endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) (Gore et al., 2015). In particular, the commonly used di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) has exhibited antiandrogenic properties both in vivo and in vitro (Botelho et al., 2009; Czernych et al., 2017), and has been found to be associated with decreased testosterone in male animals (Botelho et al., 2009) and humans (Meeker and Ferguson, 2014; Radke et al., 2018; Woodward et al., 2020). Phthalates have also been linked to reproductive disorders in both men and women (Radke et al., 2018; Radke et al., 2019). In men, phthalate exposure is associated with reduced semen volume and quality (Chiang et al., 2017; Radke et al., 2018), anogenital distance (Radke et al., 2018), and fertility (Chiang et al., 2017). In women, phthalate exposure has been linked to infertility (Gore et al., 2015), thyroid dysfunction (Gore et al., 2015), endometriosis (Gore et al., 2015), preterm birth (Radke et al., 2019), uterine fibroids (Gore et al., 2015), and breast tumors (Ahern et al., 2019). In addition, some studies have suggested that phthalates may also interfere with serum sex hormone concentrations (Cathey et al., 2019; Meeker and Ferguson, 2014; Sathyanarayana et al., 2014). For example, Meeker et al. found that DEHP was associated with lower total testosterone in a cross-sectional study among women age 40–60 years (Meeker and Ferguson, 2014). However, this study did not take into account menopausal status, which affects the distribution of circulating sex steroid hormone levels and may affect susceptibility to EDCs such as phthalates. Disruption of sex hormone concentrations, mainly in postmenopausal women, can lead to increased risk of various cancers (Key et al., 2002; Murphy et al., 2015), Alzheimer’s disease (Pike et al., 2009), type 2 diabetes (Andersson et al., 1994; Ding et al., 2009), heart failure, and cardiovascular and coronary heart disease (Zhao et al., 2018).

As evidence has accumulated of the adverse effects of older generation phthalates such as DEHP, these chemicals have been increasingly phased out and replaced by newer derivative phthalates including diisononyl phthalate (DINP), di-isodecyl phthalate (DIDP), di-2-ethylhexyl terephthalate (DEHTP), and 1,2-cyclohexane dicarboxylic acid di-isononyl ester (DINCH) (Bui et al., 2016; Trasande and Attina, 2015). However, early research indicates these newer replacements may have similar effects to their older counterparts (Kambia et al., 2019; Woodward et al., 2020). A study using data from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found DINCH to be significantly associated with lower testosterone levels among men age 40 years and older (Woodward et al., 2020). Currently, however, there is a dearth of research on the impact of these replacement chemicals on women’s health and particularly on sex hormone levels.

The purpose of this study is to examine the associations of exposure to older and newer generation phthalates with sex hormone levels in pre- and postmenopausal women participating in NHANES between 2013 and 2016. It is hypothesized that these newer replacements will have similar associations with hormone levels as the older generation phthalates.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Data Source

This study used data from the 2013–14 and 2015–16 cycles of NHANES collected by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ((CDC) and (NCHS); (CDC) and (NCHS)). NHANES is a nationally representative survey consisting of an interview and a physical examination that includes the collection of biospecimens later used for various laboratory measurements. Survey weights accompanied the data to approximate the non-institutionalized U.S. population and to account for nonresponse and complex survey design.

2.2. Study Population

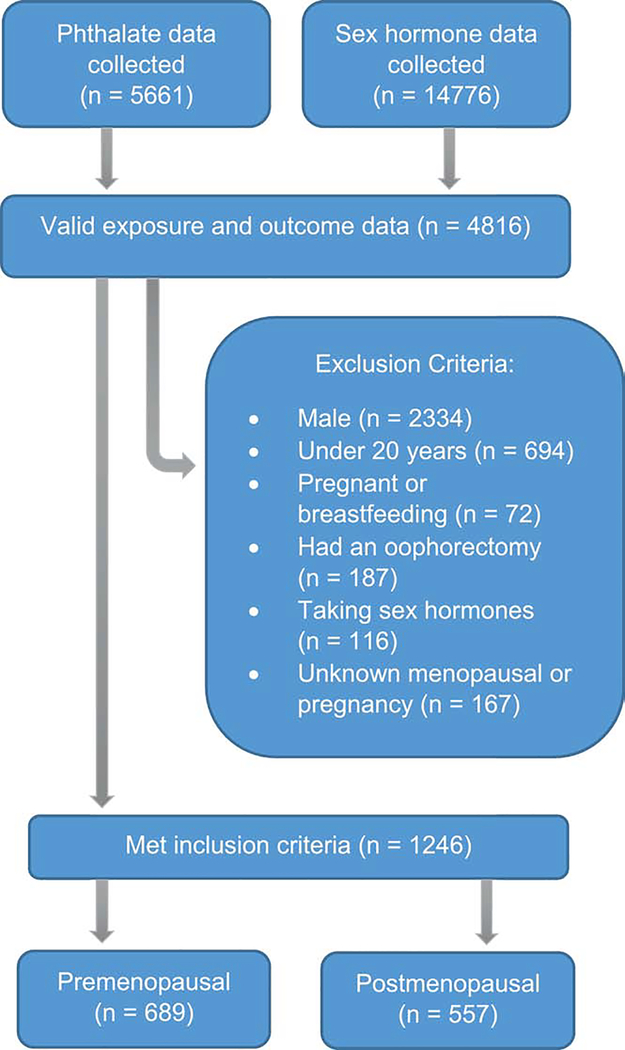

Of those who participated in NHANES between 2013–2016, 2482 women had data on serum sex hormones and urinary phthalate metabolites (Figure 1). Women who were under the age of 20 years (n=694), pregnant or breastfeeding (n=72), who had undergone oophorectomy (n=187), or were taking sex hormone-containing medication (i.e., hormonal contraceptives, hormone therapy, etc., n=116) were excluded from the study due to the differences in endogenous hormone levels in these groups. Because data on pubertal timing was not collected by NHANES, a conservative age cut point of 20 years old was used to remove those who had yet to undergo or were undergoing puberty. Women who had not had a period in 12 months due to pregnancy or breastfeeding or who had an unknown pregnancy or menopausal status were also excluded (n=167). Women who attributed not having a period in the last 12 months to menopause or who were 55 or older were considered postmenopausal (Phipps et al., 2010). The final analytic sample contained 689 premenopausal women and 557 postmenopausal women.

Figure 1.

Flow chart describing study exclusion criteria, NHANES 2013–16

2.3. Phthalate and Phthalate Alternative Compounds

The metabolites listed in Table 1 were measured by NHANES in 2013–14 and/or 2015–16. Urinary metabolite concentrations were measured using high performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Specifically, enzymatic deconjugation of the glucuronidated metabolites followed by on-line solid phase extraction in conjunction with a Thermo Scientific Accela liquid chromatograph and a Thermo Scientific TSQ Vantage triple quadruple mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization interface were used to process the samples (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2018c). Analytic details of the exposure assessment have been previously described (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2016; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2018c). Phthalate concentrations that were below the level of detection (LOD) were substituted with the lower limit of detection divided by the square root of two (Hornung and Reed, 1990). Individual phthalate metabolites were combined as molar sums corresponding to parent compounds (i.e., DEHP, DINP, DIDP, DEHTP, and DINCH), as well as their use in product categories (i.e., HMW and LMW phthalate groups, Table 1 and Equations S1). LMW and HMW phthalate and DEHP summations included metabolite measures from both NHANES cycles (i.e., 2013–14 and 2015–16), whereas DINP, DEHTP, and DINCH summations were restricted to the measures from the 2015–2016 cycle as most of the corresponding metabolites were only collected during those years.

Table 1.

Weighted percent of analytic sample with detectable urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations by parent chemical and molecular weight grouping stratified by menopausal status, NHANES 2013–2016.

| % Detected | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Groupinga | Parent Chemical | Metabolite | LLODb (ng/mL) | Pre-Menopausal women (N=689) | Post-Menopausal women (N=557) | P-value |

| Mono-ethyl phthalate (MEP) | 1.2 | 99.91 | 99.84 | 0.63 | ||

| Mono-isobutyl phthalate (MiBP) | 0.9 | 97.11 | 96.09 | 0.55 | ||

| LMW | Mono-2-methyl-2-hydroxypropyl phthalate (MHIBP) * | 0.4 | 94.99 | 90.12 | 0.32 | |

| Mono-n-butyl phthalate (MBP) | 0.4 | 97.37 | 99.01 | 0.05 | ||

| Mono-3-hydroxybutyl phthalate (MHBP) * | 0.4 | 71.84 | 75.57 | 0.44 | ||

| Monobenzyl phthalate (MBzP) | 0.3 | 97.35 | 96.34 | 0.67 | ||

| Mono(3-carboxypropyl) phthalate (MCPP) | 0.4 | 75.84 | 75.88 | 0.99 | ||

| Mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) | 0.8 | 60.68 | 46.09 | 0.00 | ||

| Mono(2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl) phthalate (MECPP) | 0.4 | 99.94 | 99.38 | 0.04 | ||

| DEHP | Mono(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate (MEHHP) | 0.4 | 99.86 | 99.67 | 0.17 | |

| Mono(2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl) phthalate (MEOHP) | 0.2 | 99.57 | 99.74 | 0.48 | ||

| Mono-isononyl phthalate (MNP) | 0.9 | 35.54 | 18.75 | 0.00 | ||

| HMW | DINP | Monocarboxyoctyl phthalate (MCOP) | 0.3 | 99.81 | 99.72 | 0.69 |

| Mono-oxo-isononyl phthalate (MONP) * | 0.4 | 91.48 | 90.59 | 0.81 | ||

| DIDP | Monocarboxy-isononyl phthalate (MCNP) | 0.2 | 97.35 | 99.27 | 0.00 | |

| DINCH | Cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylic acid mono(hydroxy-isononyl) ester (MHINCH) | 0.4 | 42.63 | 29.14 | 0.00 | |

| Cyclohexane- 1,2-dicarboxylic acid mono(carboxyoctyl) ester (MCOCH) * | 0.5 | 59.32 | 50.17 | 0.07 | ||

| DEHTP | Mono(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) terephthalate (MEHHTP) * | 0.4 | 95.17 | 93.85 | 0.61 | |

| Mono(2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl) terephthalate (MECPTP) * | 0.2 | 100 | 99.88 | 0.27 | ||

Phthalates > 250 Dalton are considered HMW, phthalates < 250 Dalton are considered LMW

Only measured in 2015–2016

LLOD, lower limit of detection

2.4. Serum Sex Hormones

Serum estradiol and total testosterone concentrations were quantified using isotope dilution liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, following the methods of the National Institute for Standards and Technology (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2018b). Chemo-luminescence measurements of the reaction between sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and immune-antibodies was used to quantify SHBG concentrations (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2018a). Testosterone-to-estradiol ratio was calculated by dividing the picomolar concentration of testosterone by that of estradiol. Free testosterone, bioavailable testosterone, and free androgen index were calculated based on the formulas below created by Vermeulen et al. and described by Ho et al. utilizing serum sex hormone and urinary albumin concentrations (Ho et al., 2006; Vermeulen et al., 1999).

Free testosterone is testosterone not bound to either albumin or SHBG, while bioavailable testosterone refers to all testosterone not bound to SHBG and therefore readily available to the body (Vermeulen et al., 1999).

2.5. Covariates

Covariates were identified by literature review and included in final models if their inclusion changed the unadjusted beta for the association between any of the phthalate metabolites and sex hormone outcomes by >10%. Smoking status was determined using serum cotinine concentrations and a 3 ng/L cutoff was used to classify active smokers (Benowitz et al., 2009). Education was categorized into three groups; high school degree or less, some college, and college graduate or higher. Other key covariates were age, race/ethnicity (i.e., non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic other), body mass index (BMI), time of day of serum collection (i.e. morning, afternoon, evening), and urinary creatinine.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Due to NHANES complex sampling design (Chen et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2014), weighted descriptive statistics stratified by menopausal status were conducted on all covariates, exposures, and outcomes using Stata survey commands and weights produced by NHANES. Extended Mood’s median test for continuous not normally distributed variables and Chi-squared tests for categorical variables were used to determine statistical differences between premenopausal and postmenopausal phthalate, sex hormone, and covariate distributions (Pan et al., 2014). For regression analysis, all measured and derived serum sex hormone concentrations were natural log-transformed to approximate a normal distribution. All phthalate concentrations were natural log-transformed due to their right skew and in order to reduce the influence of extreme outliers. Survey-weighted multivariable linear regression models stratified by menopausal status were fit for each phthalate exposure and sex steroid hormone combination. The regression models controlled for age, education, continuous BMI, race/ethnicity, serum cotinine, urinary creatinine, and time of day of blood draw for sex hormone measurement. Urinary creatinine concentrations were controlled for to account for differing urine dilutions and time of blood draw was controlled for to account for diurnal changes in sex hormone concentrations. When a negligible proportion of women had sex hormone concentrations below the LOD, observations below the LOD were replaced with the lower LOD divided by the square root of two (Hornung and Reed, 1990). However, for postmenopausal women who had a significant proportion of estradiol concentrations below the LOD (26%), Tobit regression was used to account for left truncation.

To account for multiple testing, the p-value was adjusted by dividing the significance level, α=0.05, by the effective number of tests (Meff) calculated using the formula below from a 2005 paper by Li et al (Li and Ji, 2005). The eigenvalues (λi) were determined using the correlation coefficient matrix between all seven exposures (i.e., phthalate groupings) (Li and Ji, 2005). A more detailed description of the calculations is outlined elsewhere (Li and Ji, 2005). The adjusted p-values for premenopausal and postmenopausal women were 0.0125 and 0.01, respectively.

Finally, a variety of sensitivity analyses were conducted. First, regression models were fit that excluded potential sex hormone outliers to observe whether these values made a significant impact on the results of the study. Values higher than the reference ranges cited in the NHANES Laboratory Procedure Manuals were considered outliers (n=6 for testosterone, n=9 for estradiol, and n=32 for SHBG for premenopausal women; n=12 for testosterone, n=36 for estradiol, and n=26 for SHBG for postmenopausal women) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2018a; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2018b). Second, due to the low detection of DINCH in both pre- and postmenopausal women, regression models were fit excluding those with exposure concentrations below the LOD as well as fit with DINCH exposure categorized into to tertiles (i.e. below LOD, below median of detected levels, and at or above median among detected DINCH observations). Thirdly, to explore if certain metabolites had a stronger association with outcomes than others, we fit regression models with individual metabolites for those phthalate groupings and alternatives that had significant results among postmenopausal women (Table S5) and explored correlations among them (Tables S6–S8). All analyses were conducted using Stata version 16.0 and SAS ™ software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., 2016; StataCorp, 2019).

3. Results

Of the 19 phthalate metabolites measured, 13 were detected in over 90% of the study population and 15 were detected in over 70% (Table 1). Detection frequencies of most phthalate metabolites were similar across pre- and postmenopausal women. Exceptions to this were mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, the major metabolite of DEHP; mono-isononyl phthalate, the major metabolite of DINP; and cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylic acid mono(hydroxy-isononyl) ester and cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylic acid mono(carboxyoctyl) ester, the two measured metabolites of DINCH, which were more often detected among premenopausal women.

The study population included 689 premenopausal women (median (25th, 75th percentile) age=37 (29, 45) years) and 557 postmenopausal women (median (25th, 75th percentile) age=64 (58, 71) years) (Table 2). The majority of both groups were non-Hispanic White, although postmenopausal women were slightly more likely to be White and premenopausal women were more likely to be Hispanic. There was a diversity of education levels and poverty-to-income ratios among both groups, although postmenopausal women tended to have less education than premenopausal women. Lastly, 46.3% of postmenopausal women were obese and 17.0% were smokers compared with 40.2% of premenopausal women who were obese and 25.6% of whom were smokers.

Table 2.

Weighted study population characteristics stratified by menopausal status, NHANES 2013–2016 (n=1246).

| Characteristics | Pre-Menopause (n=689) | Post-Menopause (n=557) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 37 (29, 45) | 64 (58, 71) | 0.04 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 215 (57.1%) | 199 (69.1%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 178 (14.3%) | 120 (11.3%) | |

| Hispanic | 185 (19.0%) | 179 (11.8%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Other/Multi | 111 (9.7%) | 59 (7.8%) | <0.01 |

| Educationa, n (%) | |||

| High School Degree or Less | 261 (32.4%) | 303 (41.7%) | |

| Associates Degree/Some | |||

| College | 252 (36.9%) | 159 (35.2%) | |

| College Degree or More | 176 (30.7%) | 94 (23.0%) | 0.02 |

| Poverty Income Ratiobc, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 2.7 (1.3, 4.7) | 2.9 (1.6, 5.0) | <0.01 |

| BMI (categorical)de, n (%) | |||

| Underweight & Normal | 213 (36.1%) | 139 (28.9%) | |

| Overweight | 173 (23.7%) | 145 (24.8%) | |

| Obese | 299 (40.2%) | 269 (46.3%) | 0.21 |

| Smokersf, n (%) | 164 (25.6%) | 101 (17.0%) | <0.01 |

| Time of Blood Draw, n (%) | |||

| Morning | 312 (44.6%) | 283 (51.5%) | |

| Afternoon | 244 (33.9%) | 215 (37.7%) | |

| Evening | 133 (21.5%) | 59 (10.9%) | <0.01 |

| Urinary Creatinine (mg/dL), median (25th, 75th percentile) | 109 (61, 166) | 82 (49, 122) | <0.01 |

Postmenopausal - 1 missing

Poverty-Income Ratio (PIR) was calculated by dividing family income by the poverty guidelines created by the Department of Health and Human Services, which are specific to the cycle years, geographic location, and family size ((CDC) and (NCHS), 2015; (CDC) and (NCHS), 2017; Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2015). Due to privacy concerns, ratios above 5.0 were imputed as 5.0.

Premenopausal - 55 missing, Postmenopausal - 72 missing

Premenopausal - 4 missing, Postmenopausal - 4 missing

BMI categories were based on CDC guidelines.

Smoking status was determined using serum cotinine concentrations and a 3 ng/L cut-off signifying active smokers (Benowitz et al., 2009).

Several differences were observed in the distribution of sex hormone levels and phthalate concentrations by menopausal status (Table 3). Postmenopausal women had lower median serum sex hormone concentrations than premenopausal women for all hormones except SHBG. Differences were most evident for estradiol (median (25th, 75th percentile)=5.5 (2.1, 10.0) pg/dL vs. 74.1 (37.5, 131.0) pg/dL, respectively). Differences in total, free, and bioavailable testosterone were much smaller; the median total testosterone concentration in postmenopausal women was 18.10 ng/dL (25th, 75th percentile=12.19, 24.80 ng/dL) compared with 21.90 ng/dL (25th, 75th percentile=15.80, 29.40 ng/dL) in premenopausal women. With regard to phthalate concentrations, premenopausal women had higher HMW phthalate, DINCH, DIDP, and DEHTP concentrations than postmenopausal women and postmenopausal women had higher LMW phthalate concentrations than premenopausal women. Distributions of DEHP and DINP varied only slightly between the two groups.

Table 3.

Weighted medians of urinary phthalate metabolite concentration and serum sex hormone concentrations stratified by menopausal status, NHANES 2013–2016.

| All | Pre-Menopause | Post-Menopause | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormones | Median | 25th, 75th percentile | Median | 25th, 75th percentile | Median | 25th, 75th percentile | |

| Total Testosterone (ng/dL) | 20.27 | 14.10, 28.10 | 21.90 | 15.80, 29.40 | 18.10 | 12.19, 24.80 | <0.01 |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 28.30 | 6.29, 90.10 | 74.10 | 37.50, 131.00 | 5.54 | 2.12, 10.00 | <0.01 |

| Free Testosterone (ng/dL) | 0.23 | 0.15, 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.17, 0.39 | 0.21 | 0.13, 0.30 | <0.01 |

| Bioavailable Testosterone (ng/dL) | 5.41 | 3.58, 8.27 | 5.71 | 3.91, 8.97 | 4.83 | 3.01, 7.00 | <0.01 |

| Free Androgen Index | 1.11 | 0.70, 1.82 | 1.21 | 0.78, 2.00 | 1.03 | 0.59, 1.55 | <0.01 |

| Testosterone-to-Estradiol Ratio | 7.67 | 2.30, 27.82 | 2.79 | 1.59, 5.67 | 30.28 | 18.32, 47.35 | <0.01 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 62.16 | 41.78, 88.91 | 61.22 | 40.60, 86.63 | 63.36 | 44.11, 90.83 | <0.01 |

|

Phthalates (μmol/L) | |||||||

| LMW | 0.32 | 0.15, 0.70 | 0.29 | 0.13, 0.67 | 0.35 | 0.16, 0.71 | <0.01 |

| HMW | 0.17 | 0.08, 0.34 | 0.20 | 0.09, 0.39 | 0.14 | 0.07, 0.28 | <0.01 |

| DEHP | 0.06 | 0.03, 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.03, 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.03, 0.11 | <0.01 |

| DINP | 0.03 | 0.01, 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02, 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.01, 0.05 | <0.01 |

| DINCH | 0.003 | <LOD, 0.006 | 0.004 | <LOD, 0.007 | 0.002 | <LOD, 0.005 | <0.01 |

| DEHTP | 0.06 | 0.02, 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.03, 0.33 | 0.04 | 0.02, 0.12 | <0.01 |

| DIDP | 0.006 | 0.003, 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.003, 0.012 | 0.004 | 0.003, 0.010 | <0.01 |

Among premenopausal women, phthalate concentrations were not statistically significantly associated with any of the seven hormone outcomes (Table 4). However, the associations of DINP with estradiol (−9.30%, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): −18.23%, 0.60%) and SHBG (−3.42%, 95% CI: −7.50%, 0.84%) were suggestive.

Table 4.

Percent change in serum sex hormone concentrations in response to the doubling of urinary phthalate concentrations among premenopausal women, NHANES 2013–2016 (n=689).

| Hormonal Outcomes |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposures | Total testosterone | Estradiol | SHBG | Free testosterone | Bioavailable testosterone | Testosterone/estradiol ratio | Free Androgen Index | ||||||||||||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | ||||||||

| LMW | 1.21 | −2.53 | 5.10 | −1.98 | −7.53 | 3.90 | 1.23 | −1.64 | 4.18 | 0.26 | −3.57 | 4.24 | 0.20 | −3.75 | 4.31 | 3.19 | −3.09 | 9.87 | 0.03 | −4.03 | 4.25 |

| HMW | −1.82 | −5.57 | 2.07 | 0.00 | −7.30 | 7.86 | −2.61 | −7.75 | 2.82 | 0.65 | −3.86 | 5.37 | −0.18 | −5.01 | 4.91 | −2.07 | −9.17 | 5.59 | 1.36 | −4.25 | 7.30 |

| DEHP | 0.80 | −3.65 | 5.46 | 1.65 | −5.73 | 9.60 | 2.93 | −1.97 | 8.08 | −0.19 | −4.54 | 4.36 | −0.99 | −5.60 | 3.85 | −1.04 | −7.16 | 5.48 | −1.11 | −6.06 | 4.10 |

| DINPa | −2.32 | −6.74 | 2.30 | −9.30 | −18.23 | 0.60 | −3.42 | −7.50 | 0.84 | −0.37 | −5.09 | 4.59 | −1.04 | −5.88 | 4.05 | 7.68 | −2.82 | 19.31 | 0.34 | −5.05 | 6.03 |

| DINCHa | −0.38 | −4.67 | 4.11 | 2.73 | −8.77 | 15.68 | −4.99 | −10.75 | 1.15 | 2.24 | −1.70 | 6.33 | 2.83 | −1.18 | 7.00 | −3.03 | −15.24 | 10.95 | 4.25 | −0.79 | 9.54 |

| DEHTPa | 0.72 | −3.43 | 5.06 | 1.35 | −6.78 | 10.18 | −0.13 | −3.97 | 3.86 | 0.28 | −3.95 | 4.69 | 0.30 | −4.18 | 5.00 | −0.62 | −8.39 | 7.82 | 0.47 | −4.26 | 5.43 |

| DIDP | −1.04 | −3.91 | 1.93 | −2.43 | −8.35 | 3.87 | −1.88 | −5.58 | 1.97 | 0.57 | −2.72 | 3.98 | −0.08 | −3.56 | 3.54 | 1.39 | −4.65 | 7.81 | 0.89 | −3.15 | 5.11 |

All regressions were survey-weighted and adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, BMI (continuous), smoking status, time of blood draw, and urinary creatinine concentration

P-value<0.05

P-value<0.0125

Analyses restricted to premenopausal women who completed 2015–2016 cycle (n=335)

Among postmenopausal women, lower testosterone concentrations (total, free, and bioavailable) were observed in relation to LMW, HMW, DEHP, and DINP (Table 5). However, estimates were strongest for DEHP and bioavailable testosterone. A doubling of DEHP concentration was associated with 6.2% lower bioavailable testosterone (95% CI: 0.0%, 12.1%). In addition, DEHP was associated with lower estradiol, with a doubling predicting 9.1% lower levels (95% CI: 1.3%, 16.3%). In contrast, DINCH concentrations were associated with higher free testosterone, bioavailable testosterone, and free androgen index, with estimates of >5% in relation to a doubling of exposure. DEHTP showed a similar trend to DINCH, although estimates were slightly lower and not statistically significant. However, DEHTP was associated with a higher testosterone-to-estradiol ratio: a doubling of DEHTP predicted a difference of 4.3% (95% CI: 0.7%, 7.9%). When adjusted for multiple comparisons, none of the regression results met the more stringent p-value thresholds.

Table 5.

Percent change in serum sex hormone concentrations in response to the doubling of urinary phthalate concentrations among postmenopausal women, NHANES 2013–2016 (n=557).

| Hormonal Outcomes |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposures | Total testosterone | Estradiol | SHBG | Free testosterone | Bioavailable testosterone | Testosterone/estradiol ratio | Free Androgen Index | ||||||||||||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | ||||||||

| LMW | −2.02 | −5.94 | 2.07 | −1.31 | −6.55 | 4.22 | 0.42 | −3.52 | 4.53 | −2.56 | −7.17 | 2.28 | −2.50 | −7.16 | 2.40 | −0.61 | −3.63 | 2.50 | −2.55 | −7.64 | 2.81 |

| HMW | −4.56 | −9.94 | 1.14 | −4.12 | −11.20 | 3.53 | −1.71 | −4.69 | 1.36 | −3.43 | −8.58 | 2.02 | −3.68 | −8.42 | 1.30 | −1.33 | −6.29 | 3.89 | −2.79 | −7.59 | 2.26 |

| DEHP | −5.00 | −10.67 | 1.02 | −9.09 | −16.27 | −1.30* | 1.71 | −2.52 | 6.11 | −5.82 | −11.71 | 0.45 | −6.24 | −12.07 | −0.03* | 1.65 | −3.79 | 7.41 | −6.30 | −12.41 | 0.24 |

| DINPa | −0.23 | −4.73 | 4.48 | 1.99 | −6.76 | 11.55 | 0.58 | −2.11 | 3.34 | −0.16 | −4.88 | 4.79 | −0.43 | −5.13 | 4.51 | −2.53 | −8.59 | 3.92 | −0.29 | −5.38 | 5.08 |

| DINCHa | 4.75 | −0.22 | 9.97 | 5.46 | −6.31 | 18.70 | −0.40 | −4.44 | 3.82 | 5.62 | 0.43 | 11.08* | 5.89 | 0.63 | 11.42* | 0.75 | −7.40 | 9.62 | 5.53 | 0.11 | 11.24* |

| DEHTPa | 4.25 | −1.42 | 10.25 | 0.03 | −6.82 | 7.40 | 0.28 | −3.18 | 3.87 | 4.66 | −1.80 | 11.55 | 4.68 | −1.94 | 11.75 | 4.25 | 0.69 | 7.94* | 4.30 | −2.66 | 11.76 |

| DIDP | 0.30 | −4.32 | 5.15 | 0.87 | −6.34 | 8.64 | −1.83 | −5.31 | 5.81 | 1.31 | −3.09 | 5.90 | 1.30 | −2.90 | 5.69 | 0.37 | −4.80 | 5.81 | 2.05 | −2.37 | 6.68 |

All regressions were survey-weighted and adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, BMI (continuous), smoking status, time of blood draw, and urinary creatinine concentration

P-value<0.05

P-value<0.01

Analyses restricted to postmenopausal women who completed 2015–2016 cycle (n=274)

Results were consistent directionally with the main analysis after the removal of outliers (Table S1 and S2). Additionally, when regression analysis were performed with the measures below the LOD for DINCH removed, the association with free androgen index maintained directionality but was less precise (Table S3). The regressions fit with DINCH categorized into tertiles found results with similar directionality in the third quartile but not the second quartile among postmenopausal women (Table S4).

In analyses with individual metabolites, MEHP tended to have the strongest associations with total, free, and bioavailable testosterone and free androgen index among the DEHP metabolites and MECPP tended to have the smallest associations (Table S5). Among DINCH metabolites, MCOCH tended to have larger associations with all sex hormones except SHBG and testosterone-to-estradiol ratio than MHINCH. Metabolites of DEHTP had similar effect sizes across all sex hormones. Metabolites of the same parent compound were highly correlated (ρ=0.6–0.9; Table S6–S8).

4. Discussion

This study found differences in sex hormone levels associated with phthalates and phthalate replacements among postmenopausal women but not premenopausal women prior to adjustment for multiple comparisons. The older generation phthalate, DEHP, was associated with lower estradiol and bioavailable testosterone concentrations while DINCH, a newer generation alternative to DEHP, was associated with higher bioavailable and free testosterone and higher free androgen index in postmenopausal women. DEHTP, another replacement of DEHP, was not statistically significantly associated with altered testosterone or estradiol levels, but was associated with a higher testosterone-to-estradiol ratio among postmenopausal women. Overall, these results provide preliminary evidence that newer alternatives to DEHP may also be hormonally active, similar to the older generation plasticizers. Furthermore, although DEHP is increasingly being phased out of production and use in the U.S., we still detected differences in bioavailable testosterone and estradiol among postmenopausal women, which suggests that even at lower exposure levels, impacts may remain.

In relation to DEHP, both increases and decreases in estradiol have been documented in male humans and in male and female animals (Barakat et al., 2017; Brehm et al., 2018; Høyer et al., 2018; Lovekamp-Swan and Davis, 2003). However, the inverse association between DEHP and estradiol found in this study has largely not been replicated in female human studies, although one study of pregnant women did find a non-significant inverse trend between DEHP metabolites and estradiol concentrations (Sathyanarayana et al., 2014). In contrast, reduced testosterone in relation to DEHP has been repeatedly documented in animals and humans of both sexes (Botelho et al., 2009; Brehm et al., 2018; Meeker and Ferguson, 2014; Radke et al., 2018; Sathyanarayana et al., 2014). For example, previous research reported lower testosterone levels with higher DEHP exposure in women age 40 to 60 years, but not in younger women (Meeker and Ferguson, 2014). These results are consistent with the results of this study, although we formally accounted for reproductive life stage by stratifying by menopausal status.

In contrast, our findings with regard to DINCH have not been recorded in the literature in either animal or human studies. While there is minimal research on the potential impacts of DINCH on human health, animal research has shown a lack of impacts on the reproductive system, suggesting an improved safety profile compared with DEHP (Bhat et al., 2014). However, many of these studies have not measured sex hormone concentrations as outcomes (Bhat et al., 2014). One in vitro study reported that steroidogenesis of estradiol and testosterone was not impacted by DINCH or its metabolites (Engel et al., 2018). However, this same study by Engel et al. found that DINCH metabolites increased the effects of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) on androgen receptors, indicating possible androgenic properties (Engel et al., 2018).

Similar to DINCH, there is a dearth of research on the impact of DEHTP on sex hormones. One study by Kambia et al. found DEHTP metabolites to be more influential on steroidogenesis than DEHP metabolites (Kambia et al., 2019). They also found that DEHTP increased estrogen synthesis up to 16-fold and only slightly decreased testosterone levels (Kambia et al., 2019). In contrast, we found that DEHTP was associated with higher testosterone-to-estradiol ratio by disproportionately increasing testosterone levels compared to estrogen levels. Systematic reviews have found no evidence of antiandrogenic or reproductive effects caused by DEHTP, although interestingly, like DINCH, a synergistic relationship with DHT was observed by Kambia et al. (Kambia et al., 2019).

The effects of phthalates and their alternatives on sex hormones were observed only in postmenopausal women. While these results have not been reported before in the literature, it does raise the question why postmenopausal women appear to be more susceptible to the effects of the plasticizers studied. In this study, postmenopausal women had lower exposure levels to DEHP DINCH, and DEHTP compared to premenopausal women. Therefore, it is possible that these chemicals may be more influential at lower levels, which has been observed with other EDCs (Vandenberg et al., 2012). In addition, menopause changes the endogenous hormone environment in a way that may increase the susceptibility of these women. This is consistent with the observation that DEHP has been found to be associated with reduced testosterone among older women and men (Meeker and Ferguson, 2014; Woodward et al., 2020). Additionally, one study found bisphenol A, a known EDC, to have a stronger association with obesity among postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women (Lim et al., 2020). Early research indicates that women who have undergone menopause could be at higher risk of the effects of EDCs, including phthalates, however more research is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

While the clinical implications of these finding are unclear, subtle changes in sex hormone levels among postmenopausal women have been linked with cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, heart failure, vascular function, Alzheimer’s disease, and Type 2 Diabetes (Mathews et al., 2019; Muka et al., 2017; Pike et al., 2009; Thurston et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018). Many of these diseases have a spectrum of severity as well as a subclinical stage, a period in which clinically observable symptoms are not present but from which overt disease could develop over time. In addition, it is important to note that the impacts of common EDCs on health endpoints are hypothesized to be cumulative, underscoring the notion that even if phthalates are only associated with subclinical disease, they may work in conjunction with other EDCs over a lifetime to produce a stronger effect (Ribeiro et al., 2017).

The lack of current research on these alternative plasticizers, particularly DINCH and DEHTP, is of concern. We found metabolites of DEHTP and DEHP to be present in over 99% of samples and a metabolite of DINCH, a newer replacement, to be present in over half of the samples. DINCH is used in children’s toys, cosmetics, exercise equipment, food packaging, printer ink, flooring, and even medical devices (Bui et al., 2016). DEHTP is also utilized in the production of children’s products, textiles, and flooring, but is additionally used in films and beverage caps (Bui et al., 2016). As DEHP concentrations decline, due in part to increasing regulation and public awareness, and industries transition to alternatives, DINCH and DEHTP concentrations will likely rise, highlighting the need for further investigation into the impacts of these chemicals (Zota et al., 2014).

The strengths of this study include its utilization of nationally representative data, focus on the impact of plasticizers on adult women, formal consideration of differences by reproductive life stage, and exploration of the emerging but understudied DEHP replacements including DINCH, DEHTP, DIDP, and DINP. The use of nationally representative data allows the results to be generalizable to non-institutionalized adult U.S. women. This research is one of the few studies in the literature conducted on adult women who are not pregnant. Uniquely, this study took into account women’s menopausal status, which has not been done in prior research on this particular topic. It is also rare for studies in this area to explore the impacts of these chemicals on free and bioavailable testosterone as well as free androgen index in women, which were derived from available measures. Finally, this paper helps to address the scant research available on the effects of phthalates on sex hormones in women and especially the potential effects of newer generation plasticizers such as DINCH and DEHTP.

Some limitations of this study include its cross-sectional design, lack of significant results after adjustment for multiple comparisons, and small sample size, further reduced in the case of DINCH by a low detection rate. While only a small sample of women had detectable levels of DINCH, we detected associated differences in free testosterone, bioavailable testosterone, and free androgen index. Even with the challenge of low detection, a signal robust to sensitivity analysis was observed. Due to the data being cross-sectional, we were unable to determine the temporal relationship between the exposure and outcome as well as whether the associations with DEHP and its replacements were due to acute or long-term exposure. Lastly, although the results were not statistically significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons, we provide the first report on associations of sex hormones with replacement phthalate chemicals. Given the detected patterns, this preliminary data warrants future studies with larger sample sizes.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that phthalate replacements may not be safer than their previous counterpart and may still be hormonally active. This research highlights the need for further scrutiny of the effects of phthalate alternatives, in particular, DINCH and DEHTP, on human health. Studies with both larger samples and longitudinal data are needed to better understand the impact of increased exposure to phthalates and their alternatives on sex hormone levels and any downstream health sequelae. There is an overall lack of research on how these new and old plasticizers impact sex hormone concentrations in both men and women, which is vital to understand in order to protect the population’s reproductive and overall health.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Phthalate metabolites were detected in over 99% of pre- and postmenopausal women

Only the sex hormone levels of postmenopausal women were affected by phthalates

Higher DEHP was associated with lower estradiol and bioavailable testosterone

Higher free and bioavailable testosterone and free androgen index linked with DINCH

DEHTP was associated with increased testosterone-to-estradiol ratio

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [grant numbers R01ES022972, R01ES029779, P30ES000260, and K99ES030403] The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Role of the funding source: The funding sources had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish. The authors had complete access to the data and are responsible for the decision to publish.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- About Adult BMI. Healthy Weight. 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- (CDC) CfDCaP, (NCHS) NCfHS. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data 2013–2014. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- (CDC) CfDCaP, (NCHS) NCfHS. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data 2015–2016. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- (CDC) CfDCaP, (NCHS) NCfHS. 2015–2016 Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies. Demographic Variables and Sample Weights (DEMO_I). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern TP, Broe A, Lash TL, Cronin-Fenton DP, Ulrichsen SP, Christiansen PM, et al. Phthalate Exposure and Breast Cancer Incidence: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 1800–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson B, Mårin P, Lissner L, Vermeulen A, Björntorp P. Testosterone concentrations in women and men with NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1994; 17: 405–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat R, Lin P-CP, Rattan S, Brehm E, Canisso IF, Abosalum ME, et al. Prenatal Exposure to DEHP Induces Premature Reproductive Senescence in Male Mice. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology 2017; 156: 96–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Bernert JT, Caraballo RS, Holiday DB, Wang J. Optimal serum cotinine levels for distinguishing cigarette smokers and nonsmokers within different racial/ethnic groups in the United States between 1999 and 2004. Am J Epidemiol 2009; 169: 236–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat VS, Durham JL, Ball GL, English JC. Derivation of an Oral Reference Dose (RfD) for the Nonphthalate Alternative Plasticizer 1,2-Cyclohexane Dicarboxylic Acid, Di-Isononyl Ester (DINCH). Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B 2014; 17: 63–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botelho GGK, Golin M, Bufalo AC, Morais RN, Dalsenter PR, Martino-Andrade AJ. Reproductive Effects of Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate in Immature Male Rats and Its Relation to Cholesterol, Testosterone, and Thyroxin Levels. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2009; 57: 777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm E, Rattan S, Gao L, Flaws JA. Prenatal Exposure to Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Causes Long-Term Transgenerational Effects on Female Reproduction in Mice. Endocrinology 2018; 159: 795–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui TT, Giovanoulis G, Cousins AP, Magnér J, Cousins IT, de Wit CA. Human exposure, hazard and risk of alternative plasticizers to phthalate esters. Science of The Total Environment 2016; 541: 451–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cathey AL, Watkins D, Rosario ZY, Vélez C, Alshawabkeh AN, Cordero JF, et al. Associations of Phthalates and Phthalate Replacements With CRH and Other Hormones Among Pregnant Women in Puerto Rico. Journal of the Endocrine Society 2019; 3: 1127–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Health and Nutrition Examination Laboratory Procedure Manual. Phthalates and Phthalate Alternative Metabolites. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyatttsville, MD, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Health and Nutrition Examination Laboratory Procedure Manual. Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyatttsville, MD, 2018a. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Health and Nutrition Examination Laboratory Procedure Manual. Total Estradiol and Total Testosterone. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyatttsville, MD, 2018b. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Health and Nutrition Examination Laboratory Procedure Manual. Metabolites of phthalates and phthalate alternatives. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyatttsville, MD, 2018c. [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Clark J, Riddles M, Mohadjer L, Fakhouri T. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2015−2018: Sample Design and Estimation Procedures. Vital and Health Statistics. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Maryland, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C, Mahalingam S, Flaws JA. Environmental Contaminants Affecting Fertility and Somatic Health. Seminars in reproductive medicine 2017; 35: 241–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czernych R, Chraniuk M, Zagożdżon P, Wolska L. Characterization of estrogenic and androgenic activity of phthalates by the XenoScreen YES/YAS in vitro assay. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2017; 53: 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding EL, Song Y, Manson JE, Hunter DJ, Lee CC, Rifai N, et al. Sex hormone-binding globulin and risk of type 2 diabetes in women and men. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 1152–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel A, Buhrke T, Kasper S, Behr AC, Braeuning A, Jessel S, et al. The urinary metabolites of DINCH(®) have an impact on the activities of the human nuclear receptors ERα, ERβ, AR, PPARα and PPARγ. Toxicol Lett 2018; 287: 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore AC, Chappell VA, Fenton SE, Flaws JA, Nadal A, Prins GS, et al. EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocrine reviews 2015; 36: E1–E150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CK, Stoddart M, Walton M, Anderson RA, Beckett GJ. Calculated free testosterone in men: comparison of four equations and with free androgen index. Ann Clin Biochem 2006; 43: 389–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung RW, Reed LD. Estimation of Average Concentration in the Presence of Nondetectable Values. Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 1990; 5: 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Høyer BB, Lenters V, Giwercman A, Jönsson BAG, Toft G, Hougaard KS, et al. Impact of Di-2-Ethylhexyl Phthalate Metabolites on Male Reproductive Function: a Systematic Review of Human Evidence. Curr Environ Health Rep 2018; 5: 20–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C, Dohrmann S, Burt V, Mohadjer L. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Sample Design, 2011–2014. Vital and Health Statistics. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Maryland, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambia NK, Séverin I, Farce A, Moreau E, Dahbi L, Duval C, et al. In vitro and in silico hormonal activity studies of di-(2-ethylhexyl)terephthalate, a di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate substitute used in medical devices, and its metabolites. 2019; 39: 1043–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key T, Appleby P, Barnes I, Reeves G. Endogenous sex hormones and breast cancer in postmenopausal women: reanalysis of nine prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94: 606–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ji L. Adjusting multiple testing in multilocus analyses using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix. Heredity 2005; 95: 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JE, Choi B, Jee SH. Urinary bisphenol A, phthalate metabolites, and obesity: do gender and menopausal status matter? Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2020; 27: 34300–34310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovekamp-Swan T, Davis BJ. Mechanisms of phthalate ester toxicity in the female reproductive system. Environ Health Perspect 2003; 111: 139–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews L, Subramanya V, Zhao D, Ouyang P, Vaidya D, Guallar E, et al. Endogenous Sex Hormones and Endothelial Function in Postmenopausal Women and Men: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2019; 28: 900–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker JD, Ferguson KK. Urinary Phthalate Metabolites Are Associated With Decreased Serum Testosterone in Men, Women, and Children From NHANES 2011–2012. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2014; 99: 4346–4352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muka T, Nano J, Jaspers L, Meun C, Bramer WM, Hofman A, et al. Associations of Steroid Sex Hormones and Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin With the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in Women: A Population-Based Cohort Study and Meta-analysis. Diabetes 2017; 66: 577–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy N, Strickler HD, Stanczyk FZ, Xue X, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Rohan TE, et al. A Prospective Evaluation of Endogenous Sex Hormone Levels and Colorectal Cancer Risk in Postmenopausal Women. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015; 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Phthalates and Cumulative Risk Assessment: The Tasks Ahead: National Academies Press, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Prior HHS Poverty Guidelines and Federal Register References 2020. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Caudill SP, Li R, Caldwell KL. Median and quantile tests under complex survey design using SAS and R. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2014; 117: 292–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps AI, Ichikawa L, Bowles EJA, Carney PA, Kerlikowske K, Miglioretti DL, et al. Defining menopausal status in epidemiologic studies: A comparison of multiple approaches and their effects on breast cancer rates. Maturitas 2010; 67: 60–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike CJ, Carroll JC, Rosario ER, Barron AM. Protective actions of sex steroid hormones in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neuroendocrinol 2009; 30: 239–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke EG, Braun JM, Meeker JD, Cooper GS. Phthalate exposure and male reproductive outcomes: A systematic review of the human epidemiological evidence. Environ Int 2018; 121: 764–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke EG, Glenn BS, Braun JM, Cooper GS. Phthalate exposure and female reproductive and developmental outcomes: a systematic review of the human epidemiological evidence. Environ Int 2019; 130: 104580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro E, Ladeira C, Viegas S. EDCs Mixtures: A Stealthy Hazard for Human Health? Toxics 2017; 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS Software, Version 9.4. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sathyanarayana S, Barrett E, Butts S, Wang C, Swan SH. Phthalate exposure and reproductive hormone concentrations in pregnancy. Reproduction (Cambridge, England) 2014; 147: 401–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thurston RC, Bhasin S, Chang Y, Barinas-Mitchell E, Matthews KA, Jasuja R, et al. Reproductive Hormones and Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease in Midlife Women. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 2018; 103: 3070–3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trasande L, Attina TM. Association of exposure to di-2-ethylhexylphthalate replacements with increased blood pressure in children and adolescents. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex. : 1979) 2015; 66: 301–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg LN, Colborn T, Hayes TB, Heindel JJ, Jacobs DR Jr., Lee D-H, et al. Hormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals: low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responses. Endocrine reviews 2012; 33: 378–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen A, Verdonck L, Kaufman JM. A Critical Evaluation of Simple Methods for the Estimation of Free Testosterone in Serum. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 1999; 84: 3666–3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward MJ, Obsekov V, Jacobson MH, Kahn LG, Trasande L. Phthalates and Sex Steroid Hormones Among Men From NHANES, 2013–2016. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2020; 105: e1225–e1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D, Guallar E, Ouyang P, Subramanya V, Vaidya D, Ndumele CE, et al. Endogenous Sex Hormones and Incident Cardiovascular Disease in Post-Menopausal Women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71: 2555–2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zota AR, Calafat AM, Woodruff TJ. Temporal trends in phthalate exposures: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2010. Environmental health perspectives 2014; 122: 235–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.