Abstract

Objective

To investigate the diffusion trajectory of a cationic contrast medium (CA4+) into equine articular cartilage, and to assess normal and degenerative equine articular cartilage using cationic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT).

Design

In the first experiment (Exp1), equine osteochondral specimens were serially imaged with cationic CECT to establish the diffusion time constant and time to reach equilibrium in healthy articular cartilage. In a separate experiment (Exp2), articular cartilage defects were created on the femoral trochlea (defect joint) in a juvenile horse, while the opposite joint was a sham-operated control. After 7 weeks, osteochondral biopsies were collected throughout the articular surfaces of both joints. Biopsies were analyzed for cationic CECT attenuation, glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content, mechanical stiffness (Eeq), and histology. Imaging, biochemical and mechanical data were compared between defect and control joints.

Results

Exp1: The mean diffusion time constant was longer for medial condyle cartilage (3.05 ± 0.1 hours) than lateral condyle cartilage (1.54 ± 0.3 hours, P = 0.04). Exp2: Cationic CECT attenuation was lower in the defect joint than the control joint (P = 0.005) and also varied by anatomic location (P = 0.045). Mean cationic CECT attenuation from the lateral trochlear ridge was lower in the defect joint than in the control joint (2223 ± 329 HU and 2667 ± 540 HU, respectively; P = 0.02). Cationic CECT attenuation was strongly correlated with both GAG (ρ = 0.79, P < 0.0001) and Eeq (ρ = 0.61, P < 0.0001).

Conclusions

The equilibration time of CA4+ into equine articular cartilage is affected by tissue volume. Quantitative cationic CECT imaging reflects the biochemical, biomechanical and histological state of normal and degenerative equine articular cartilage.

Keywords: horse, osteoarthritis, contrast agent, computed tomography arthrography (CTa), imaging

Introduction

Detection of early articular cartilage injury is a substantial problem in humans and horses. Early cartilage degeneration begins with changes in the extracellular matrix, particularly the loss of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs).1 In normal (healthy) articular cartilage, the negative charges on GAGs attract water, maintaining tissue hydration and affording compressive stiffness.2 Conversely, the depletion of GAGs reduces water retention and weakens the tissue, promoting articular cartilage deterioration. Despite its status as a gold standard method of articular cartilage evaluation, routine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques only capture morphologic changes and are incapable of characterizing the early biochemical alterations in GAGs that precede morphologic change.3,4 This limitation has led to the development of quantitative MRI techniques to identify early degenerative changes in articular cartilage.5-7 Delayed gadolinium-enhanced MRI of cartilage (dGEMRIC) is one example of a quantitative method where administered gadolinium (negatively charged) contrast media distributes in articular cartilage in inverse proportion to GAG and the measured signal reflects the biochemical content of cartilage.8 Despite its utility, the persistence of gadolinium in tissues years after administration as well as potentially fatal complications has led to a decline in its use in humans.9,10

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) is a promising imaging technique that is widely available and offers shorter acquisition times and higher spatial resolution compared with MRI.11,12 Commercially available iodinated contrast media are either negatively charged or uncharged and have limited penetration into articular cartilage.13 Exploiting the high negative charges in the extracellular matrix, a cationic contrast agent (CA4+) was developed for its electrostatic attraction to GAGs with a similar chemical structure to ioxaglate.14,15 The CECT attenuation obtained with CA4+ is 2.9 times higher than with anionic contrast media.14 The CA4+ (cationic) CECT attenuation correlates with GAG (R2 = 0.63-0.87)15-19 and the R2 values are greater than that obtained with anionic contrast media (R2 = 0.2-0.62), especially when anionic contrast media concentrations are <80 mg I (iodine)/mL.15-17,20,21 Additionally, CA4+ attenuation significantly correlates to mechanical properties (equilibrium compressive modulus and coefficient of friction) of articular cartilage.17-19

Previous studies have reported the diffusion course and time for CA4+ to reach equilibrium within articular cartilage and the ability of cationic CECT imaging to characterize bovine tissues.15,22,23 While bovine articular cartilage is easily acquired and commonly used in orthopedic studies, there are notable differences between bovine and equine cartilage (e.g., thickness, chondrocyte density, and collagen and proteoglycan concentration).24-26 Additionally, horses are an important and established translational research species for preclinical human studies because of similarities in articular cartilage properties and athletic performance of both species.25,27,28 Despite the promising results shown in bovine cartilage, the time needed for CA4+ to reach equilibrium and the ability of cationic CECT to characterize normal and degenerative cartilage in equine cartilage is unknown.

Thus, the objectives of this study are to characterize the diffusion profile of CA4+ into equine articular cartilage, to determine the capability of cationic CECT to highlight differences in degenerative and normal cartilage and to establish the quantitative relationship between CECT attenuation and GAG content and mechanical stiffness (equilibrium modulus, E). We hypothesize, first, that articular cartilage volume influences CA4+ diffusion and, second, that cationic CECT attenuation is significantly correlated with GAG content and Eeq across a range of articular cartilage degradation.

Methods

Trajectory of Cationic Contrast Media Diffusion into Equine Articular Cartilage

Osteochondral plug specimens were collected from the femoral condyles of a 3-year-old horse that was euthanized for reasons unrelated to this experiment. The soft tissues were dissected away from the femur and a stationary band saw was used to separate the femoral condyles from the remaining portions of the femur. The articular surfaces were macroscopically evaluated to ensure there was no evidence of joint disease or articular cartilage defects. Using a 7-mm (internal diameter) diamond-tipped cylindrical coring drill bit (Starlite Industries, Bryn Mawr, PA) attached to a drill press (Delta Power Equipment Company, Anderson, SC), 6 osteochondral plugs were removed under constant water irrigation to reduce tissue heating. The coring drill bit was orientated perpendicular to the site of harvest. Once complete, the osteochondral plugs were immediately irrigated with 400 mOsmol/kg saline to prevent hypotonic desiccation from the water lavage. Three osteochondral plugs were acquired from the medial and lateral femoral condyles (n = 6, Fig. 1 ). Each osteochondral plug was stored at 4°C in 400 mOsmol/kg saline with a preservative solution containing a protease inhibitor, antibiotic and antimycotic (5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; 5 mM benzamidine HCl, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; 1× Gibco Antibiotic-Antimycotic, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The plugs were secured in a custom fixture and imaged with microCT (microCT40, Scanco Medical, Brütisellen, Switzerland) in air at 70 kVp, 113 µA, 300 ms integration time and with isotropic 36 µm3 voxel dimensions.

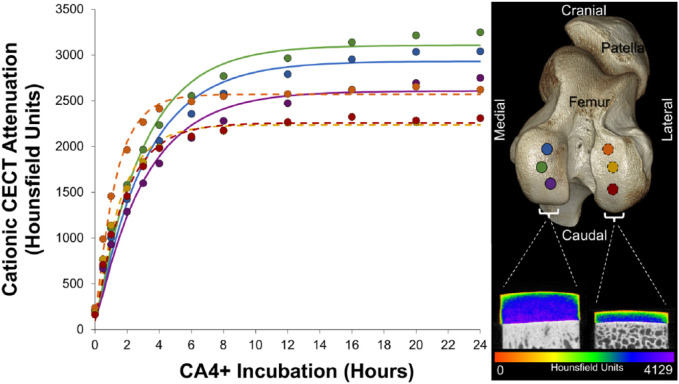

Figure 1.

Trajectory of CA4+ diffusion into equine articular cartilage as measured by cationic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) attenuation. The mean cationic CECT attenuation of each cartilage plug is plotted against the duration of CA4+ incubation (medial condyle, solid lines; lateral condyle, dotted lines). Locations on the femoral condyles where the plugs were harvested are shown in the right image along with representative sample microCT images from each femoral condyle after reaching equilibrium.

The CA4+ contrast media (8 mg I/mL) was prepared in purified water (Barnstead NanoPure, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) as per established protocols,14,29 and adjusted to a pH of 7.4 and 400 mOsmol/kg—replicating the pH and osmolality of normal synovial fluid.30 After the baseline scan, the plugs were submerged in 90 mL of CA4+ and rescanned at sequential time points to monitor the uptake of CA4+ diffusion over time into articular cartilage. At each successive time point after baseline, the fixture was removed from the CA4+ solution and the cartilage lightly blotted with gauze to remove excess CA4+. The plugs were then scanned at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 hours of submersion at the same acquisition settings used above. The duration of microCT scans (~40 minutes per scan acquisition) was excluded from the total time of CA4+ submersion.

The cationic CECT images were converted to digital imaging and communications in medicine (DICOM) format and imported to commercial processing software (Analyze, version 12.0, Biomedical Imaging Resource, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). The articular cartilage from each plug at each time point was digitally segmented from the subchondral bone and air using a semi-automatic threshold-based algorithm with manual verification to ensure accuracy. Articular cartilage volume and thickness were calculated for each plug. The mean cationic CECT attenuation values were converted to linear attenuation coefficients and then to Hounsfield units (HU) using the deionized water scanned in each respective acquisition.31 The diffusion of CA4+ into cartilage was quantified by plotting the mean cationic CECT attenuation of each plug against the duration of CA4+ incubation. Diffusion data of each plug were then fit to a curve using a nonlinear least-square regression equation [CTdiff = CTmax (1 – e–t/τ)] in MATLAB (R2017a, Mathworks, Natick, MA).32 The diffusion equation coefficients included CTdiff, the cationic CECT attenuation at 63.2% of equilibrium; CTmax, the maximum cationic CECT attenuation (at equilibrium); t, diffusion time; and τ, the time to reach 63.2% of maximum cationic CECT attenuation (diffusion time constant).32 Diffusion equilibrium was defined at 5 × τ.32 The goodness-of-fit of the curve for each plug was determined by the coefficient of determination.

The segmented volume of the articular cartilage from each osteochondral plug was measured at each time point to determine tissue volume and thickness. Object maps of each volume were created using a semiautomatic threshold-based algorithm (AnalyzeDirect, Overland Park, KS). Using the line profile tool, automated sampling of tissue thickness using 400 locations perpendicular to the articular surface was performed across the entire plug volume. The mean cartilage thickness was generated from an average of all sampled regions for each plug.

Cationic CECT Characteristics of Normal and Degenerative Equine Articular Cartilage

All in vivo experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the animal care and use committee at Colorado State University (Protocol: 13-4363A). In a separate experiment, initiation of degenerative articular cartilage in vivo was performed by creating full thickness chondral defects on the femoral trochlea to disrupt normal joint congruity and promote degradation of surrounding tissue.33 In a juvenile, skeletally mature horse aged 4 years, critically sized circular chondral defects were created in the left (defect) femoropatellar joint while the contralateral (right, control) femoropatellar joint was sham-operated to confirm normal articular cartilage.28,34 Under arthroscopic guidance, 1 chondral defect (15 mm diameter) was made on the medial trochlear ridge of the femur and 2 chondral defects (1 proximal and 1 distal—each 10 mm in diameter; 10 mm apart) were made on the lateral trochlear ridge of the femur using chondral biopsy punches (DePuy Mitek, Raynham, MA). The calcified cartilage layer in the medial and distal lateral trochlear ridge defects was removed to promote healing, while it was retained in the proximal lateral trochlear ridge defect to impede healing.34 The arthroscopic portals were then closed and the horse recovered from general anesthesia. The horse remained on stall confinement for 12 days until the incisions healed and was then permitted free paddock exercise to promote the degeneration of articular cartilage adjacent to the created defects.28 At 47 days after surgery, the horse was euthanized and osteochondral plugs (n = 72) were harvested from the femoral trochlea—38 from the defect joint (3 within defects) and 34 from the control joint surfaces. Attempts were made to place the coring bit perpendicular to each site to create a flat, cylindrical articular cartilage geometry important for accurate mechanical testing. This optimized positioning used at individual coring sites led to variation in spacing between biopsies causing a disparity in sample numbers between the defect and control joints. After removal, each osteochondral plug was assigned an Outerbridge (OB) score,35 and frozen at −20°C in the preservative solution until further mechanical, imaging and biochemical evaluations. A single freeze-thaw cycle does not diminish the biochemical and mechanical properties of articular cartilage.36,37

Prior to mechanical testing, each plug was thawed at room temperature for 2 hours and a microCT scan (same acquisition settings as above) was performed to determine the mean articular cartilage thickness as described above to calculate displacement values for each plug. Plugs with insufficient surface geometry were excluded from mechanical testing to ensure measurement accuracy, permitting 47 plugs for mechanical evaluation (29 from the defect joint and 18 from the control joint). Each plug with sufficient surface geometry was rigidly fixed in a mechanical testing system (Enduratec3230, BOSE, Eden Prairie, MN) and immersed in 400 mOsm/kg saline. An unconfined compressive pre-load was applied to the cartilage surface using a nonporous ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene platen. A sequence of four incremental 5% compressive strain steps (0.333% per second) was performed with 45 minutes stress-relaxation intervening between strain steps. A collection rate of 10 Hz was used to record the force and displacement data and a linear fit to stress versus strain was used to calculate the equilibrium compressive modulus (E) for each cartilage specimen.

Following mechanical testing, a solution of CA4+ at 8 mgI/mL was prepared as described above for plug incubation. Each cartilage plug was submerged in 2 mL of CA4+ solution (approximately 20 times cartilage volume) for 24 hours. After incubation, all specimens were imaged using microCT at the acquisition settings described above. After microCT imaging, each cartilage plug was rinsed in a large volume of saline with preservative solution for 24 hours at room temperature to remove residual CA4+. Then, half of each cartilage specimen was sharply dissected from the subchondral bone, weighed, lyophilized and digested in papain (1 mg/mL in 50 mM sodium phosphate, 5 mM EDTA, and 2 mM dithiothreitol, with a pH of 6.8) at 65°C overnight. The sample of papain digested cartilage from each plug was analyzed with the 1,9-dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) assay to determine mean GAG content (as a % of wet weight) using standards of chondroitin sulfate to generate a standard curve.38

The remaining portion of articular cartilage and bone from each plug not analyzed with the DMMB assay was decalcified and underwent routine histologic processing.39,40 Afterward, each sample was embedded in paraffin and 5 μm sections were placed on microscope slides. The slides were stained with safranin-O fast green (SOFG) to highlight proteoglycan content in articular cartilage and were examined under light microscopy.39,40 The quantity and distribution of proteoglycan staining was descriptively evaluated throughout the articular cartilage zones in each sample.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data were reported as mean ± standard deviation. Scored data were reported as median (range). As the diffusion data were not normally distributed (established by Shapiro-Wilk testing), a Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to determine differences in τ values between medial and lateral condyle samples. A repeated-measures analysis of variance was performed to determine sequential alterations in articular cartilage volume within the medial and lateral condyle samples over time.

For the disease characterization experiment, cationic CECT attenuation was compared with GAG and Eeq using a Spearman rank correlation.41 Osteochondral samples within the chondral defects (n = 3) were not included in the statistical comparisons. A mixed effects model was used to determine differences in cationic CECT attenuation between anatomic locations where the plugs were harvested (medial vs. lateral trochlea) and between the defect and control joints. Osteochondral plugs were denoted as random factors while the remaining effects were fixed. All statistical analyses were performed using commercial software (SAS Studio, University Edition, v.9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Trajectory of Cationic Contrast Media Diffusion into Equine Articular Cartilage

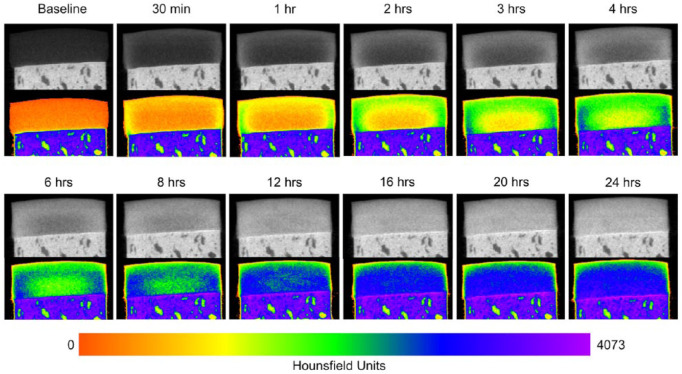

The amount of CA4+ that diffused into each articular cartilage explant progressively increased over the 24-hour experimental period ( Fig. 1 ). The diffusion course of CA4+ started radially from the peripheral edges and surface of the plug extending further into the central and deep articular cartilage layers over time ( Fig. 2 ). All diffusion curve equations had a strong fit to the data (all plugs: R2 > 0.97). The mean diffusion time constant of the medial condyle samples was significantly higher than the lateral condyle samples (3.05 ± 0.1 and 1.54 ± 0.3 hours, respectively; P = 0.04). Diffusion equilibrium was reached in the medial condyle samples at 15.2 ± 0.51 hours and in the lateral condyle samples at 7.68 ± 1.36 hours. At diffusion equilibrium, there was higher cationic CECT attenuation in the middle and deep zones compared with the superficial zone in all plugs.

Figure 2.

Serial microCT images showing the diffusion course of CA4+ into equine articular cartilage. All images are taken from the same osteochondral plug (medial femoral condyle) shown in Figure 1. The top image under each time point is shown in standard gray scale while the image beneath is after a color map was applied reflecting the distribution of CA4+ throughout the tissue over time. For all images, window width and leveling were kept consistent.

The mean articular cartilage volume and thickness were significantly larger in the medial (111.13 ± 7.3 mm3 and 2.84 ± 0.21 mm, respectively) than in the lateral (49.37 ± 5.57 mm3 and 1.25 ± 0.11 mm, respectively) femoral condyle samples (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.046, respectively) ( Fig. 1 ). There were no significant differences in articular cartilage volume over time (P = 0.98).

Cationic CECT Characterization of Degenerative Equine Articular Cartilage

Macroscopic examination of the defect joint revealed that the medial and distal lateral trochlear ridge defects were completely devoid of cartilaginous tissue (OB score 4), while the proximal lateral defect had a small portion of repair tissue overlying the subchondral bone (OB score 3). Approximately 18 mm from the periphery of the medial trochlear ridge defect, there was fissuring and bruising (OB score: 1.5 [1-2]), while the articular cartilage adjacent to the lateral defects was minimally altered (OB score: 0.5 [0-1]). The remainder of sites in the defect joint and all sites in the control joint had a congruous articular surface with no observable surface defects (OB score: 0 [0-0]).

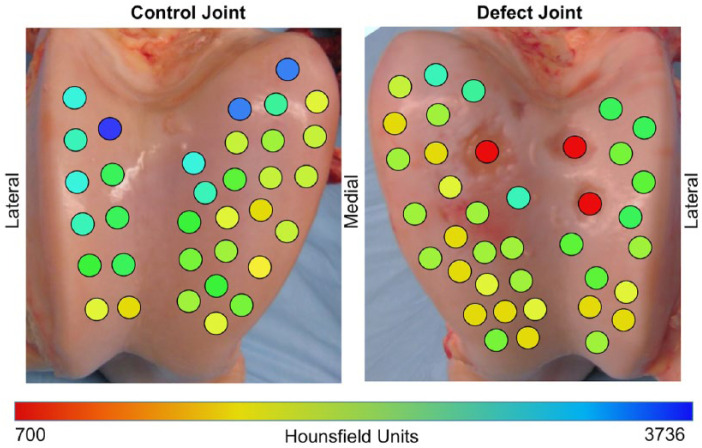

Distributions of mean cationic CECT attenuation from the osteochondral plugs varied between the defect and control joint surfaces ( Fig. 3 ). Cationic CECT attenuation in the defect joint was significantly lower than the control joint (P = 0.005) and varied by anatomic location (P = 0.045). Mean cationic CECT attenuation from the lateral trochlear ridge was significantly lower in the defect joint than in the control joint (2223 ± 329 and 2667 ± 540 HU, respectively; P = 0.02). Mean cationic CECT attenuation of the medial trochlear ridge was lower, but not significantly different between the defect and control joints (2034 ± 349 and 2257 ± 512 HU, respectively; P = 0.073).

Figure 3.

Topographical relationship between the mean cationic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT; microCT) attenuation of each osteochondral plug at equilibrium and the locations of their harvest on the femoral trochlear surfaces in a 4-year-old horse 7 weeks after surgical defects were created. Three critically sized chondral defects were created in the left femoropatellar (defect) joint, while the right (control) joint was sham-operated. The samples shown in red reflect the locations of the chondral defects.

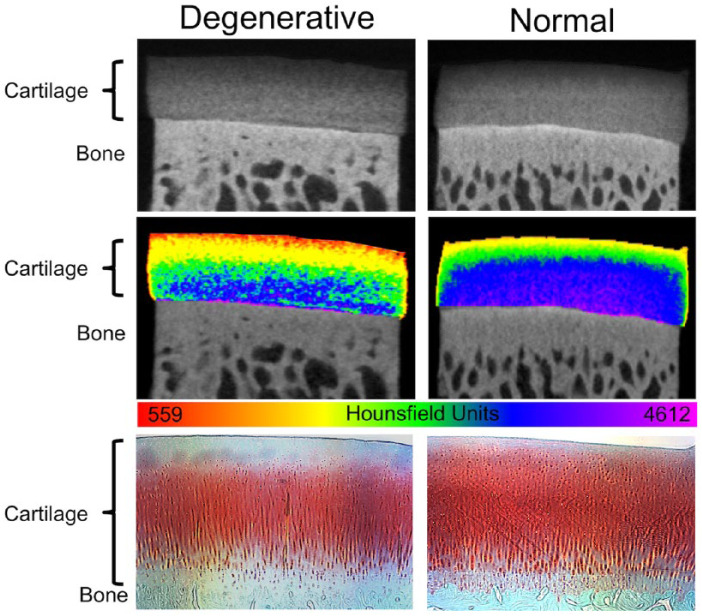

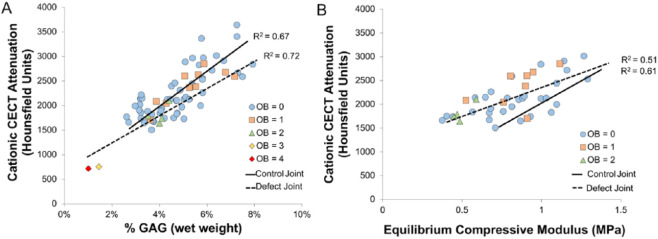

Depth-dependent assessments of individual plugs showed lower cationic CECT attenuation within each articular cartilage zone (i.e., superficial, middle, deep) in samples adjacent to full thickness defects compared to those same zones in the control joint plugs ( Fig. 3 ). Histological evaluation of both degenerative and normal samples revealed that low cationic CECT attenuation locations corresponded to areas of low safranin-O stain uptake ( Fig. 4 ). Cationic CECT attenuation was strongly correlated with both GAG (ρ = 0.79, P < 0.0001) and Eeq (ρ = 0.61, P < 0.0001) ( Fig. 5 ).

Figure 4.

Cationic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) imaging of degenerative and normal (healthy) equine cartilage with comparative histology. The top row of images shows cationic CECT of osteochondral plugs collected from equine femoropatellar joint surfaces. The degenerative plug was collected from a location adjacent to a full-thickness articular cartilage defect. The normal cartilage sample was collected from a joint with no macroscopic cartilage damage. The middle row images show the same microCT scans with an applied color map to highlight the ranges of cationic CECT attenuation throughout each tissue. Note the lower cationic CECT attenuation in all zones in the degenerative versus normal samples despite similar tissue thickness. The bottom row shows comparative histology (safranin-O fast green stain) of the plugs after microCT imaging. High amounts of safranin-O (red) uptake indicate high levels of proteoglycans / glycosaminoglycans in the tissue.

Figure 5.

Comparison of cationic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) attenuation to glycosaminoglycan (GAG) concentration (image A) and equilibrium compressive modulus (Eeq, image B) in equine trochlear cartilage samples. Each plug is also identified by its macroscopic characteristics (Outerbridge [OB] scores). Regression lines with coefficients of determination are shown from the samples collected from a joint 7 weeks after full-thickness chondral defects were created (defect joint, dotted lines) and in the contralateral sham-operated joint (control, solid lines).

Discussion

The results of the diffusion trajectory experiment supported our first hypothesis that articular cartilage volume influences the properties of CA4+ diffusion into the tissue. The CA4+ contrast medium reached equilibrium in equine cartilage, though the time to reach steady state was dependent on the differences in tissue volume that varied by anatomic location. Diffusion of solutes and contrast media into articular cartilage is governed by Gibbs-Donnan equilibrium.42 Tissue thickness also influences diffusion rates,43-47 and our results with CA4+ diffusion into equine cartilage were consistent with this observation. Minor variations in GAG and collagen content minimally affect diffusion rates unless those constituents are depleted enough to alter water mobility.42,43 The articular cartilage samples used in this experiment all had OB scores of 0, characteristic of morphologically normal tissue. Further experiments are required to determine potential differences in equilibration time between normal and early and late stage degenerative cartilage. A study investigating CA4+ diffusion into healthy bovine articular cartilage showed a diffusion constant of 1.74 hours,22 whereas this equine study revealed 3.05 and 1.54 hours for medial and lateral condyles, respectively. Articular cartilage thickness differs between these species at these anatomic locations. Studies have shown that bovine cartilage thickness is similar between medial and lateral femoral condyles (0.89-1 mm),48,49 whereas equine articular cartilage is thicker on the medial condyle (2.2-2.3 mm) than on the lateral condyle (1.2-1.84 mm)—a common disparity observed in many other mammalian species.24,25,50,51 Considering sites with similar tissue thickness and variability around the diffusion constant, the results obtained from this experiment were similar to Stewart et al.22 Nonetheless, there are notable differences in chondrocyte density and collagen and proteoglycan concentrations between equine and bovine tissue that could influence diffusion rates.24-26

While measuring the mean cationic CECT attenuation of the entire plug for the CA4+ diffusion trajectory gives diffusion rates, articular cartilage possesses a heterogeneous distribution of constituents (e.g., GAG, collagen, water) based on tissue depth. Concentrations of these constituents also differ across joint surfaces and between species to accommodate specific functional (load-bearing) demands.24,52-54 The quantity of GAGs and therefore negative fixed charge density gradients increase with tissue depth influencing the electrostatic attraction of cationic solutes and compounds into cartilage.55 Thus, a single mean cationic CECT attenuation measurement would not reflect the zonal variations in the tissue. However, qualitative assessments of the plugs showed lower cationic CECT attenuation in the superficial zone, relative to the middle and deep zones, and these observations were consistent with proteoglycan distributions revealed in SOFG histologic stains and GAG concentrations measured through biochemical assays.38,40,56 Despite the heterogeneity and variable tissue volumes between medial and lateral condyle cartilage, the GAG, chondrocyte DNA, and collagen concentrations are not different at similar tissue depths.51

In intact joints, diffusion occurs through the articular surface (superficial zone); however, in this experiment, the transected (peripheral) edges of the explanted osteochondral plugs permitted radial diffusion. As such, the distance and rates of diffusion and therefore time to reach equilibrium with CA4+ would be longer in intact ex vivo joints.57 The diffusion results of this in vitro study must not be directly extrapolated to ex vivo (intact joint) studies because of the lack of radial diffusion, or to in vivo situations because of active joint metabolism and the lack of mechanically induced convection facilitating agent diffusion into the tissue.57 To address radial diffusion and better replicate in vivo diffusion trajectory, the plug edges could have been sealed or a central region-of-interest could have been measured. However, these efforts would have introduced variation in methods complicating how these results could be compared with previous work in bovine cartilage or with other contrast agents.22,58-61 Nonetheless, subsequent in vivo experiments in rabbits and horses have demonstrated full-thickness articular cartilage imaging within hours of injection, suggesting that the 24-hour diffusion period used in vitro is unnecessary.22,62 Despite the limited number of cartilage samples from a single horse used in the diffusion trajectory experiment, this methodology revealed a significant difference between medial and lateral femoral condyles, imparting the need to recognize these differences in tissue volume when evaluating properties of CA4+ diffusion into articular cartilage.

The results from the second experiment supported our hypothesis that cationic (CA4+) CECT attenuation of degenerative and healthy equine articular cartilage has a strong and significant relationship with GAG concentration and Eeq ( Fig. 5 ). Similar observations have been documented in normal and chondroitinase-degraded bovine articular cartilage.13,16,18 Cationic CECT attenuation, GAG and Eeq varied across the defect and control joint surfaces. With declining GAG and Eeq values, a corresponding decrease in cationic CECT attenuation was observed in both joints. In healthy equine articular cartilage, the GAG and Eeq of the femoral trochlea are both higher at the proximal aspect and decline distally.24 This same distribution was observed in this study—higher cationic CECT attenuation proximally than distally along the trochlear surface.

Cationic CECT imaging showed differences between the defect and control joint cartilage. Compared with the control joint, the average cationic CECT attenuation of all the defect joint samples was reduced. In the regions adjacent to the chondral defects, cationic CECT attenuations were lower than at comparable locations in the control joint, indicating less CA4+ uptake due to decreased GAG in the tissue. Degeneration in articular cartilage adjacent to the created defects was confirmed by lower GAG and Eeq compared with the controls and depletion of these factors have been found in this chondral defect model previously.33 Histological evaluation similarly confirmed a decline in proteoglycan staining throughout all zones of the degenerative samples ( Fig. 4 ). By-site analysis further highlighted differences between the defect and control joints. Significantly lower cationic CECT attenuations were present at the lateral trochlear ridge in the defect joint compared to the control, while at the medial trochlear ridge the differences approached significance. The reasons for the observed disparity between the medial and lateral sites were likely due to the differences in biopsy numbers, limited sample size and variability of GAG in normal articular cartilage. Compared with the medial trochlear ridge, fewer biopsies were collected from the lateral trochlear ridge because of the smaller surface area available for sample harvest. The fewer biopsies collected on the lateral ridge coupled with a higher number of defects provided a wider magnitude of change between the degenerated (defect joint) and normal (control joint) cartilage than was observed on the medial trochlear ridge. Despite a large number of biopsied locations, all samples in this experiment were from a single horse and normal biochemical variability exists across articular surfaces in horses of different ages and athletic status.52,53,63,64 Thus, the variability between animals and its effect on cationic CECT imaging requires further investigation.

The osteochondral biopsy size was selected because it is smaller than a critically sized defect (i.e., capable of spontaneous healing without intervention).28,34 Thus, capturing differences with this sampling size was relevant and supports clinical translation of this methodology. Despite the observed differences between the defect and control joints in this study, there was substantial biochemical variability in normal articular cartilage, complicating the ability of a single observation measurement to indicate degeneration. While these results demonstrated cationic CECT is effectively implemented in vitro, application of these methods in vivo using clinical scanners requires additional consideration. Clinical CT scanners have lower spatial and contrast resolution and signal-to-noise ratios than microCT scanners. Additionally, the microCT scans were acquired in air, which provides higher contrast resolution with cartilage than in vivo situations where synovial fluid and joint soft tissues are less discernable from cartilage. Nonetheless, a preliminary investigation of CA4+ in intact equine joints (ex vivo) showed that clinical scanners are capable of discriminating cartilage from surrounding joint tissues.65 Further work into the applicability of this method to determine thresholds for distinguishing degenerative and normal cartilage, to generate articular surface maps, and to establish its reliable and practical use in clinical scanners requires investigation.

In conclusion, equine articular cartilage volume and anatomic location affect the diffusion profile and time to reach equilibrium for CA4+ cationic contrast media. Also, cationic CECT imaging reflects the biochemical, biomechanical, and histological state of normal and degenerative articular cartilage. Importantly, strong statistically significant correlations are present between CECT attenuation and GAG and Eeq in normal and degenerative cartilage. The next steps in the translation of this technology to the clinic include additional studies examining variability between animal species, efficacy and pharmacokinetic/biodistribution studies in vivo and comparisons of this cationic CECT imaging method to other currently available quantitative MRI techniques such as dGEMRIC and T1ρ. The potential research, preclinical, and clinical benefits of rapid articular cartilage imaging with a quantitative assessment of tissue volume, GAGs and Eeq warrants continued development of new contrast agents and imaging modalities, and their performance evaluation in ex vivo and in vivo models.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments and Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors gratefully acknowledge support in part from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM098361; MWG and BDS), the T32 Pharmacology Training grant (T32GM008541; JDF), the Cooperative Veterinary Scientist Research Training Fellowship at Colorado State University (BBN) the Grayson-Jockey Club Research Foundation, Boston University, and the Gail Holmes Equine Orthopedic Research Center at Colorado State University.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: All in vivo experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the animal care and use committee at Colorado State University (Protocol: 13-4363A).

Animal Welfare: The present study followed international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for humane animal treatment and complied with relevant legislation.

ORCID iD: Brad B. Nelson  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0205-418X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0205-418X

References

- 1. Maldonado M, Nam J. The role of changes in extracellular matrix of cartilage in the presence of inflammation on the pathology of osteoarthritis. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:284873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Han EH, Chen SS, Klisch SM, Sah RL. Contribution of proteoglycan osmotic swelling pressure to the compressive properties of articular cartilage. Biophys J. 2011;101(4):916-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Strickland CD, Kijowski R. Morphologic imaging of articular cartilage. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2011;19:229-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nelson BB, Kawcak CE, Barrett MF, McIlwraith CW, Grinstaff MW, Goodrich LR. Recent advances in articular cartilage evaluation using computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Equine Vet J. 2018;50(5):564-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guermazi A, Alizai H, Crema MD, Trattnig S, Regatte RR, Roemer FW. Compositional MRI techniques for evaluation of cartilage degeneration in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(10):1639-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pease A. Biochemical evaluation of equine articular cartilage through imaging. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2012;28:637-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Potter HG, Black BR, Le RC. New techniques in articular cartilage imaging. Clin Sports Med. 2009;28(1):77-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams A, Gillis A, McKenzie C, Po B, Sharma L, Micheli L. et al. Glycosaminoglycan distribution in cartilage as determined by delayed gasdolinium-enhanced MRI of cartilage (dGEMRIC): potential clinical applications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(1):167-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abraham JL, Thakral C, Skov L, Rossen K, Marckmann P. Dermal inorganic gadolinium concentrations: evidence for in vivo transmetallation and long-term persistence in nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158(2):273-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grobner T. Gadolinium—a specific trigger for the development of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2006;21(4):1104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lusic H, Grinstaff MW. X-ray computed tomography contrast agents. Chem Rev. 2013;113(3):1641-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nelson BB, Goodrich LR, Barrett MF, Grinstaff MW, Kawcak CE. Use of contrast media in computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in horses: techniques, adverse events and opportunities. Equine Vet J. 2017;49(4):410-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bansal PN, Joshi NS, Entezari V, Grinstaff MW, Snyder BD. Contrast enhanced computed tomography can predict the glycosaminoglycan content and biomechanical properties of articular cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:184-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Joshi NS, Bansal PN, Stewart RC, Snyder BD, Grinstaff MW. Effect of contrast agent charge on visualization of articular cartilage using computed tomography: exploiting electrostatic interactions for improved sensitivity. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(37):13234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bansal PN, Joshi NS, Entezari V, Malone BC, Stewart RC, Snyder BD. et al. Cationic contrast agents improve quantification of glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content by contrast enhanced CT imaging of cartilage. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:704-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bansal PN, Stewart RC, Entezari V, Snyder BD, Grinstaff MW. Contrast agent electrostatic attraction rather than repulsion to glycosaminoglycans affords a greater contrast uptake ratio and improved quantitative CT imaging in cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(8):970-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lakin BA, Ellis DJ, Shelofsky JS, Freedman JD, Grinstaff MW, Snyder BD. Contrast-enhanced CT facilitates rapid, non-destructive assessment of cartilage and bone properties of the human metacarpal. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(12):2158-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lakin BA, Grasso DJ, Shah SS, Stewart RC, Bansal PN, Freedman JD. et al. Cationic agent contrast-enhanced computed tomography imaging of cartilage correlates with the compressive modulus and coefficient of friction. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(1):60-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lakin BA, Patel H, Holland C, Freedman JD, Shelofsky JS, Snyder BD. et al. Contrast-enhanced CT using a cationic contrast agent enables non-destructive assessment of the biochemical and biomechanical properties of mouse tibial plateau cartilage. J Orthop Res. 2016;34(7):1130-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kallioniemi AS, Jurvelin JS, Nieminen MT, Lammi MJ, Töyräs J. Contrast agent enhanced pQCT of articular cartilage. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52(4):1209-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kulmala KA, Karjalainen HM, Kokkonen HT, Tiitu V, Kovanen V, Lammi MJ. et al. Diffusion of ionic and non-ionic contrast agents in articular cartilage with increased cross-linking—contribution of steric and electrostatic effects. Med Eng Phys. 2013;35(10):1415-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stewart RC, Bansal PN, Entezari V, Lusic H, Nazarian RM, Snyder BD. et al. Contrast-enhanced CT with a high-affinity cationic contrast agent for imaging ex vivo bovine, intact ex vivo rabbit and in vivo rabbit cartilage. Radiology. 2013;266(1):141-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lakin BA, Grasso DJ, Stewart RC, Freedman JD, Snyder BD, Grinstaff MW. Contrast enhanced CT attenuation correlates with the GAG content of bovine meniscus. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(11):1765-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Changoor A, Hurtig MB, Runciman RJ, Quesnel AJ, Dickey JP, Lowerison M. Mapping of donor and recipient site properties for osteochondral graft reconstruction of subchondral cystic lesions in the equine stifle joint. Equine Vet J. 2006;38(4):330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Frisbie DD, Cross MW, McIlwraith CW. A comparative study of articular cartilage thickness in the stifle of animal species used in human pre-clinical studies compared to articular cartilage thickness in the human knee. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2006;19:142-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hoemann CD. Molecular and biochemical assays of cartilage components. In: De Ceuninck F, Sabatini M, Pastoureau P. editors. Cartilage and osteoarthritis: structure and in vivo analysis. Vol 2. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2004. p. 127-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kol A, Arzi B, Athanasiou KA, Farmer DL, Nolta JA, Rebhun RB. et al. Companion animals: translational scientist’s new best friends. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(308):308ps21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McIlwraith CW, Fortier LA, Frisbie DD, Nixon AJ. Equine models of articular cartilage repair. Cartilage. 2011;2:317-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stewart RC, Patwa AN, Lusic H, Freedman JD, Wathier M, Snyder BD. et al. Synthesis and preclinical characterization of a cationic iodinated imaging contrast agent (CA4+) and its use for quantitative computed tomography of ex vivo human hip cartilage. J Med Chem. 2017;60(13):5543-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shanfield S, Campbell P, Baumgarten M, Bloebaum R, Sarmiento A. Synovial fluid osmolality in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(235):289-95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Watanabe Y. Derivation of linear attenuation coefficients from CT numbers for low-energy photons. Phys Med Biol. 1999;44(9):2201-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bursac PM, Freed LE, Biron RJ, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Mass transfer studies of tissue engineered cartilage. Tissue Eng. 1996;2(2):141-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Strauss EJ, Goodrich LR, Chen CT, Hidaka C, Nixon AJ. Biochemical and biomechanical properties of lesion and adjacent articular cartilage after chondral defect repair in an equine model. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(11):1647-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hurtig MB, Fretz PB, Doige CE, Schnurr DL. Effects of lesion size and location on equine articular cartilage repair. Can J Vet Res. 1988;52:137-46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Outerbridge RE. The etiology of chondromalacia patellae. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43-B:752-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Changoor A, Fereydoonzad L, Yaroshinsky A, Buschmann MD. Effects of refrigeration and freezing on the electromechanical and biomechanical properties of articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng. 2010;132(6):064502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rozen B, Brosh T, Salai M, Herman A, Dudkiewicz I. The effects of prolonged deep freezing on the biomechanical properties of osteochondral allografts. Cell Tissue Bank. 2009;10(1):27-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Farndale RW, Buttle DJ, Barrett AJ. Improved quantitation and discrimination of sulphated glycosaminoglycans by use of dimethylmethylene blue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;883(2):173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. An YH, Gruber HE. Introduction to experimental bone and cartilage histology. In: An YH, Martin KL. editors. Handbook of histology methods for bone and cartilage. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2003. p. 3-31. [Google Scholar]

- 40. McIlwraith CW, Frisbie DD, Kawcak CE, Fuller CJ, Hurtig M, Cruz A. The OARSI histopathology initiative—recommendations for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the horse. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(suppl 3):S93-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159-74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Maroudas AI. Balance between swelling pressure and collagen tension in normal and degenerate cartilage. Nature. 1976;260:808-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Maroudas A. Distribution and diffusion of solutes in articular cartilage. Biophys J. 1970;10(5):365-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Silvast TS, Kokkonen HT, Jurvelin JS, Quinn TM, Nieminen MT, Töyräs J. Diffusion and near-equilibrium distribution of MRI and CT contrast agents in articular cartilage. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:6823-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Torzilli PA, Askari E, Jenkins JT. Water content and solute diffusion properties in articular cartilage. In: Ratcliffe A, Woo SL, Mow VC. editors. Biomechanics of diarthrodial joints. New York, NY: Springer; 1990. p. 363-390. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bajpayee AG, Scheu M, Grodzinsky AJ, Porter RM. A rabbit model demonstrates the influence of cartilage thickness on intra-articular drug delivery and retention within cartilage. J Orthop Res. 2015;33(5):660-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Maroudas A, Evans H. A study of ionic equilibria in cartilage. Conn Tissue Res. 1972;1(1):69-77. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Espino DM, Shepherd DE, Hukins DW. Viscoelastic properties of bovine knee joint articular cartilage: dependency on thickness and loading frequency. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Williamson AK, Chen AC, Sah RL. Compressive properties and function-composition relationships of developing bovine articular cartilage. J Orthop Res. 2001;19(6):1113-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Malda J, de Grauw JC, Benders KE, Kik MJ, van de, Lest CH, Creemers LB. et al. Of mice, men and elephants: the relation between articular cartilage thickness and body mass. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Malda J, Benders KE, Klein TJ, de Grauw JC, Kik MJ, Hutmacher DW. et al. Comparative study of depth-dependent characteristics of equine and human osteochondral tissue from the medial and lateral femoral condyles. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(10):1147-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Brama PA, TeKoppele JM, Bank RA, Barneveld A, van Weeren PR. Development of biochemical heterogeneity of articular cartilage: influences of age and exercise. Equine Vet J. 2002;34(3):265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Garcia-Seco E, Wilson DA, Cook JL, Kuroki K, Kreeger JM, Keegan KG. Measurement of articular cartilage stiffness of the femoropatellar, tarsocrural, and metatarsophalangeal joints in horses and comparison with biochemical data. Vet Surg. 2005;34(6):571-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Treppo S, Koepp H, Quan EC, Cole AA, Kuettner KE, Grodzinsky AJ. Comparison of biomechanical and biochemical properties of cartilage from human knee and ankle pairs. J Orthop Res. 2000;18(5):739-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nimer E, Schneiderman R, Maroudas A. Diffusion and partition of solutes in cartilage under static load. Biophys Chem. 2003;106(2):125-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fox AJS, Bedi A, Rodeo SA. The basic science of articular cartilage: structure, composition, and function. Sports Health. 2009;1(6):461-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Entezari V, Bansal PN, Stewart RC, Lakin BA, Grinstaff MW, Snyder BD. Effect of mechanical convection on the partitioning of an anionic iodinated contrast agent in intact patellar cartilage. J Orthop Res. 2014;32:1333-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Silvast TS, Jurvelin JS, Lammi MJ, Töyräs J. pQCT study on diffusion and equilibrium distribution of iodinated anionic contrast agent in human articular cartilage—associations to matrix composition and integrity. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:26-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Silvast TS, Jurvelin JS, Tiitu V, Quinn TM, Töyräs J. Bath concentration of anionic contrast agents does not affect their diffusion and distribution in articular cartilage in vitro. Cartilage. 2013;4(1):42-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stubendorff JJ, Lammentausta E, Struglics A, Lindberg L, Heinegård D, Dahlberg LE. Is cartilage sGAG content related to early changes in cartilage disease? Implications for interpretation of dGEMRIC. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(5):396-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gillis A, Gray M, Burstein D. Relaxivity and diffusion of gadolinium agents in cartilage. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48(6):1068-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nelson BB. Investigation of cationic contrast-enhanced computed tomography for the evaluation of equine articular cartilage [dissertation]. Fort Collins, CO: Clinical Sciences, Colorado State University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Brama PA, Tekoppele JM, Bank RA, Barneveld A, van Weeren PR. Functional adaptation of equine articular cartilage: the formation of regional biochemical characteristics up to age one year. Equine Vet J. 2000;32(3):217-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Brama PA, Tekoppele JM, Bank RA, Karssenberg D, Barneveld A, van Weeren PR. Topographical mapping of biochemical properties of articular cartilage in the equine fetlock joint. Equine Vet J. 2000;32(1):19-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nelson BB, Stewart RC, Kawcak CE, Freedman JD, Snyder BD, Goodrich LR. et al. Development of an osteoarthritis grading system based on clinical contrast-enhanced computed tomography for the assessment of cartilage integrity. Paper presented at: The 62nd Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Research Society; March 5-8, 2016; Orlando, FL. [Google Scholar]