Abstract

The intestinal microbiome changes dynamically in early infancy. Colonisation by Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides and development of intestinal immunity is interconnected. We performed a prospective observational cohort study to determine the influence of antibiotics taken by the mother immediately before delivery on the intestinal microbiome of 130 healthy Japanese infants. Faecal samples (383) were collected at 1, 3, and 6 months and analysed using next-generation sequencing. Cefazolin was administered before caesarean sections, whereas ampicillin was administered in cases with premature rupture of the membranes and in Group B Streptococcus-positive cases. Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides were dominant (60–70% mean combined occupancy) at all ages. A low abundance of Bifidobacterium was observed in infants exposed to antibiotics at delivery and at 1 and 3 months, with no difference between delivery methods. A lower abundance of Bacteroides was observed after caesarean section than vaginal delivery, irrespective of antibiotic exposure. Additionally, occupancy by Bifidobacterium at 1 and 3 months and by Bacteroides at 3 months differed between infants with and without siblings. All these differences disappeared at 6 months. Infants exposed to intrapartum antibiotics displayed altered Bifidobacterium abundance, whereas abundance of Bacteroides was largely associated with the delivery method. Existence of siblings also significantly influenced the microbiota composition of infants.

Subject terms: Microbiome, Antibiotics, Microbiota

Introduction

The human body is inhabited by 100–1000 trillion bacteria in the oral cavity, skin, and intestine, influencing the biological health of the host1, 2. There are large differences in the composition of the human intestinal microbiome depending on race, country, and lifestyle3–5. Although the predominance of Bifidobacterium in the intestinal microbiome has been identified in Japanese children, there are very few studies on the intestinal microbiome specifically in Japanese infants5–10.

Many studies have indicated an association between the intestinal microbiome and disease11–13. Colonisation by intestinal bacteria in early infancy is known to have a major effect on intestinal immunity14–16. In particular, colonisation by the dominant bacteria such as Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides17–23, resulting from the start of food ingestion at 6 months after birth has been implied to be linked with the onset of diseases such as allergies24–26. Various factors are known to influence bacterial colonisation, including maternal exposure to antibiotics administered as intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis (IAP) in Group B Streptococcus (GBS)-positive mothers27–29 and antibiotic administration in the late perinatal period30. These studies, however, have reported differences in the administration and screening period, and offer inconclusive results. The influence of the delivery method on the Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides populations in infants has also been extensively studied16, 31–33. It is a widely accepted hypothesis that as infants delivered by caesarean section do not pass through the birth canal, they do not come in contact with the maternal bacterial microbiome, thus influencing the microbiome of the infant34, 35. However, the actual influence of caesarean sections on infant intestinal microbiome differs among studies and is, therefore, uncertain. Moreover, the prophylactic administration of antibiotics immediately before surgery in caesarean sections, while the foetus and umbilical cord are connected, has not been considered in most studies36, 37. A recent study38 investigated the effect of exposure to cefloxime prior to caesarean section on the intestinal microbiome of infants at 10 days and 9 months of age. No distinct difference in gut microbiota composition was observed at 10 days postnatal. The nutrition method35, 39, presence or absence of siblings19, 40, 41, and gestational age33, 42, 43 may also influence the intestinal microbiome.

We previously examined the influence of antibiotics administered immediately before delivery on intestinal colonisation of Bifidobacteria in a pilot study of 1-month-old healthy Japanese infants44. This study showed that antibiotic administration to the mother at the time of delivery has a strong influence on the Bifidobacteria population and that this influence may even be more substantial than that of caesarean section.

Unlike previous studies of IAP, this pilot study was unique in a sense that the antibiotics were used for GBS and IAP in cases of premature rupture of the membranes (PROM) and routinely before caesarean section. i.e., antibiotics were used in the mother immediately before delivery, while the umbilical cord was still intact. Interestingly, the results revealed a significantly higher bifidobacterial occupancy in infants with siblings. In contrast, Bacteroides occupancy was substantially influenced by delivery mode compared to antibiotic exposure at delivery. As the pilot study43 had a cross-sectional design and was limited to 33 1-month-old infants, a continuous study comprising a larger group of infants was needed to confirm the results.

Based on the above background, the present study defined antibiotic exposure of infants through antibiotics administered to their mothers immediately before delivery as antimicrobial exposure at delivery (AED). Based on the hypothesis that AED may have a strong influence on the intestinal microbiome of healthy Japanese children in early infancy, especially on the dominant bacterial genera Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides, samples were collected from infants until 6 months after birth, and the influence of AED and other factors in the infant population were investigated.

Results

Subject data

A total of 142 mother and infant pairs were registered in the study, and 424 samples were obtained. Among these, 130, 127, and 126 samples collected at 1, 3, and 6 months, respectively, adhered to the inclusion criteria of the study. Subjects were excluded due to the following reasons: three premature babies dropped out by 1 month of age, one infant received antibiotic administration for fever in the neonatal period, and there were eight cases at 1 month with samples that could not be analysed. While dropouts from 1 to 3 months were due to antibiotic administration in eight cases, no samples were received in one case, and a non-analysable sample was received at 3 months in one case, dropouts from 3 to 6 months were due to antibiotic administration in one case and a non-analysable sample at 6 months in one case.

The background information of the mothers and infants at 1 month, which were influencing factors, are shown in Table 1. As the dropout cases resulted in no major change in the mean value of the background factors, the data at 3 and 6 months are shown in Supplementary Table S1 online. Antibiotics were used immediately before delivery in about 55% of cases at each age. caesarean section, GBS-positive, and PROM cases accounted for about 20%, 15%, and 15% of all cases at each age, respectively. The PROM cases included one emergency and 6 GBS-positive caesarean sections. These seven cases were included in the caesarean section group because cefazolin (CEZ) was administered as an antibiotic. In 5 PROM cases, delivery progressed rapidly, and no antibiotic was used. Of the infants born by caesarean section, the Apgar score at birth was low in two cases, oxygen was administered after birth for mild neonatal respiratory disorder in one case, phototherapy was performed for neonatal jaundice in one case, the mothers had diabetes in two cases, the mothers had hyperthyroidism in two cases, and one infant was admitted for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection during the observation period and discharged after symptomatic treatment. Regarding the nutritional method, the infants enrolled in this study were those that were solely breastfed and those that were mix-fed, and none were fed milk only. All infants were confirmed to be healthy via a health examination at each age by physicians of the paediatrics and neonatology department.

Table 1.

Background factors of 1-month-old infants and their mothers.

| Background factors | Data |

|---|---|

| Number of infants | 130 |

| Number of females | 70 (54.0%) |

| Gestational age at birtha | 275.1 ± 9.3 |

| Birth weighta | 3038.9 ± 339.7 |

| Maternal antimicrobial use at delivery | 74 (56.9%) |

| Caesarean section | 31 (23.8%) |

| Premature rupture of membrane | 22 (16.9%) |

| Group B Streptococcus-positive status | 33 (25.4%) |

| Infants with older siblings | 67 (51.5%) |

| Exclusive Breast feeding | 80 (61.5%) |

| Age of Mothersa | 31.6 ± 5.1 |

| Maternal history of allergy | 55 (42.3%) |

| Neonatal respiratory disorder | 2 (1.5%) |

| Neonatal jaundice | 4 (3.1%) |

| RSV infection | 3 (2.3%) |

| Maternal history of smoking | 9 (6.9%) |

| Maternal history of Hyperthyroidism | 2 (1.5%) |

| Maternal history of Diabetes Mellitus | 2 (1.5%) |

RSV respiratory syncytial virus.

aGestational age at birth, birth weight, and maternal age are shown as the mean ± standard deviation. Other factors are given as the number of subjects and a percentage.

As for the sequencing data, input numeric totaled 15,957,768 reads, an average of 41,665 reads, a maximum of 261,246 reads, and a minimum of 17,884 reads. In addition, non-chimeric numeric reads totaled 11,055,110, an average of 28,864, a maximum of 180,762, and a minimum of 12,828.

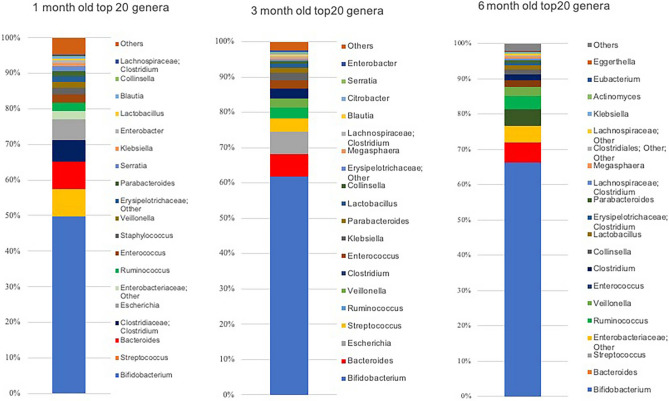

The top 20 bacterial genera constituting the intestinal microbiome at each age are shown in Fig. 1. At 1 month, based on the occupancy, the Bifidobacteria population was found to be overwhelmingly dominant (49.7% ± 34.1%), whereas the Bacteroides population was found to be the third most dominant (7.7% ± 12.6%), but its occupancy was almost equivalent to the second most dominant bacteria, Streptococcus (7.8% ± 12.6%). The Bifidobacteria population was also the most dominant at 3 months (61.7% ± 28.0%), whereas the Bacteroides population was the second most dominant (6.5% ± 10.9%). The Bifidobacteria population continued to be the most dominant at 6 months (66.2% ± 21.6%), followed by the Bacteroides population (5.7% ± 9.2%).

Figure 1.

Mean occupancies of the top 20 bacterial genera constituting the intestinal microbiome at 1, 3, and 6 months after birth. At each age, the occupancies of the top 20 genera (others are indicated as ‘Others’) are shown as 100% stacked columns. The genera are shown in the order of higher occupancy from the bottom to the top. This figure was generated using Microsoft Excel for Mac 2016 (https://www.microsoft.com).

Analysis at 1 month

The effects of background factors on the five most dominant bacterial genera of the intestinal microbiome of 1-month-old infants are shown in Table 2. Bifidobacteria occupancy was significantly dependent on the exposure to AED (non-AED: Odds Ratio (OR), 0.11; 95% Confidence Interval (CI), 0.03–0.39) and the existence of siblings (no sibling: OR 3.03; 95% CI 1.09–8.4), whereas that of Bacteroides significantly depended on the delivery method (vaginal delivery: OR 0.03; 95% CI 0.003–0.23), but not on the exposure to AED or the existence of siblings. The fourth dominant genera, Clostridium (6.2% ± 15.5%), showed significant effects of the exposure to AED (non-AED: OR 4.98; 95% CI 1.69–14.7), delivery method (vaginal delivery: OR 4.94; 95% CI 1.1–22.2), the existence of siblings (no sibling: OR 0.22; 95% CI 0.07–0.66), and feeding methods (exclusive breastfeeding: OR 5.88; 95% CI 2.24–15.4).

Table 2.

Influence of background factors of the mother and child at 1 month on occupancies of the five most dominant bacterial genera in the intestinal microbiome of the infant.

| Variances | Bifidobacterium | Streptococcus | Bacteroides | Clostridium | Escherichia | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | ||||||||||

| Gestational daysa | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 0.99 | 1.11 | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.98 | * | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.14 | ** | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.98 | ** | |

| 2 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 1.09 | 1.03 | 0.98 | 1.09 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.94 | ** | 1.06 | 1.002 | 1.13 | * | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.99 | * | |

| 3 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 1.07 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 1.10 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 1.02 | ||||

| Birth weighta | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 1.00 | 1.001 | 0.99 | 1.002 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 1.00 | 1.002 | 1.00 | 1.003 | 0.998 | 0.996 | 0.999 | ** | |||

| 2 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 1.00 | 1.001 | 0.99 | 1.002 | 0.998 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.001 | 1.00 | 1.003 | 0.998 | 0.99 | 1.00 | ||||

| 3 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 1.00 | 0.999 | 0.99 | 1.001 | 0.999 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.001 | 1.00 | 1.003 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 1.001 | ||||

| Age of mothersa | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.11 | 1.02 | 0.93 | 1.13 | 1.09 | 0.94 | 1.14 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.99 | * | 1.07 | 0.97 | 1.18 | |||

| 2 | 0.96 | 0.87 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.11 | 1.03 | 0.94 | 1.14 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 1.04 | 1.13 | 1.02 | 1.25 | ||||

| 3 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 0.94 | 1.14 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 1.21 | 0.96 | 0.86 | 1.07 | 1.05 | 0.96 | 1.16 | ||||

| Male | 1.47 | 0.57 | 3.75 | 1.20 | 0.57 | 2.53 | 1.35 | 0.56 | 3.23 | 0.85 | 0.33 | 2.18 | 1.45 | 0.67 | 3.14 | ||||

| Vaginal delivery | 1.84 | 0.49 | 6.92 | 1.06 | 0.32 | 3.54 | 0.026 | 0.003 | 0.23 | ** | 4.94 | 1.10 | 22.23 | * | 0.48 | 0.14 | 1.68 | ||

| Infants without siblings | 3.03 | 1.09 | 8.43 | * | 1.19 | 0.56 | 2.57 | 0.96 | 0.40 | 2.33 | 0.22 | 0.072 | 0.66 | ** | 0.84 | 0.38 | 1.87 | ||

| Non-AED | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.39 | *** | 1.22 | 0.53 | 2.82 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 1.56 | 4.98 | 1.69 | 14.69 | ** | 0.75 | 0.32 | 1.77 | ||

| Mothers without allergy | 1.33 | 0.51 | 3.50 | 1.27 | 0.60 | 2.72 | 1.14 | 0.46 | 2.78 | 0.85 | 0.33 | 2.23 | 1.62 | 0.73 | 3.58 | ||||

| Exclusively breast-fed | 1.06 | 0.41 | 2.73 | 2.06 | 0.96 | 4.41 | 1.61 | 0.66 | 3.94 | 5.88 | 2.24 | 15.43 | *** | 0.97 | 0.44 | 2.13 | |||

The bacterial genera are shown from left to right in the order of higher occupancy (mean). For the continuous variables (a gestational age at birth, birth weight, and maternal age), occupancy was classified from 1 to 4 in ascending order from low occupancy with the occupancy of each bacterial species rounded to four decimal places. For the high occupancy group (group 4), a multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed as the category standard and the occupancy was classified into two groups based on the median for each genus for the logistic regression analysis for categorical variables. The odds ratio and 95% confidence interval were calculated using the logistic regression analysis and the multinomial regression analysis. The significance level was set at 5%. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Analysis at 3 months

The effects of background factors on the five most dominant bacterial genera and other high-ranking genera of the intestinal microbiome of 3-month-old infants are shown in Supplementary Table S2 online. Bifidobacteria occupancy was significantly dependent on the exposure to AED (non-AED: OR 0.3; 95% CI 0.09–0.9) and the existence of siblings (no sibling: OR 3.73; 95% CI 1.1–12.6), similar to that seen at 1 month (p < 0.05), whereas that of Bacteroides was significantly dependent on the delivery method (vaginal delivery: OR 0.14; 95% CI 0.03–0.63), also similar to that at 1 month (p < 0.05). The fifth dominant genus, Ruminococcus (2.9% ± 8.5%), showed a significant dependence on feeding methods (exclusive breastfeeding: OR 2.5; 95% CI 1.13–5.62).

Analysis at 6 months

The effects of background factors on the five most dominant bacterial genera and on other high-ranking genera of the intestinal microbiome in 6-month-old infants are shown in Supplementary Table S2 online. Bifidobacteria occupancy showed no significant dependence on any factor, and Bacteroides only showed a significant dependence on exclusive breastfeeding (p < 0.05). There were significant effects of the delivery method (vaginal delivery: OR 0.26; 95% CI 0.07–0.91) and the existence of siblings (no sibling: OR 0.26; 95% CI 0.07–0.91) on the third most dominant genus, Streptococcus (4.8% ± 6.9%). The mothers’ allergy history (with history of allergy: OR 2.67; 95% CI 1.20–5.94) significantly affected the fourth most dominant genus, Enterobacteriaceae; and feeding methods (exclusive breastfeeding: OR 0.29; 95% CI 0.12–0.66) significantly affected the fifth most dominant genus, Ruminococcus.

Effects of AED

Infants at each age were divided based on the AED status and delivery method, and background factors of the mother and child were compared. The results are shown in Supplementary Table S3 online. In infants born via caesarean section, the existence of siblings and age of the mother were significantly higher due to the influence of the previous caesarean section, and the gestational age and birth weight were significantly lower because the date of caesarean delivery was decided beforehand unless performed as an emergency. This tendency also existed between the two types of delivery methods in the AED group, but a sub-group analysis of the vaginal delivery group, excluding the influence of caesarean section, showed no difference in background factors between the AED and non-AED groups. The effect of background factors that influenced the dominant bacterial genera at each age (AED, delivery method, siblings) and the occupancies by Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides were then analysed.

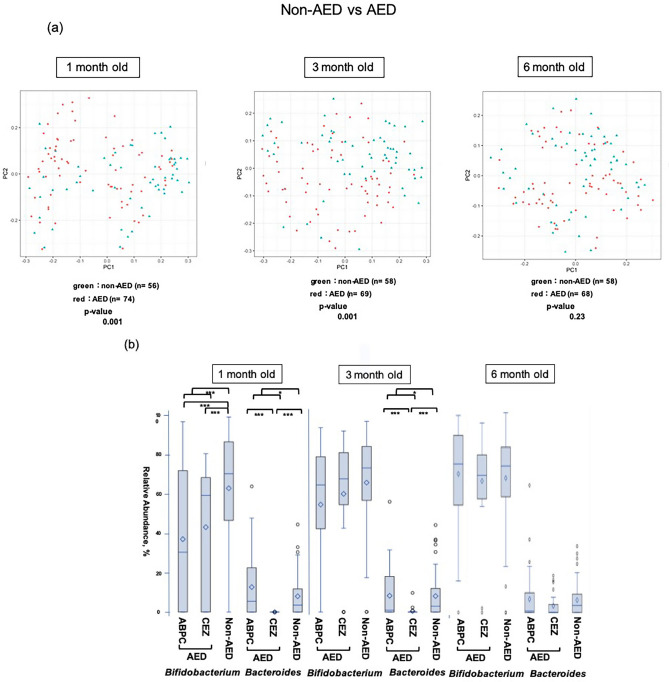

AED had a significant effect on the overall diversity of the intestinal microbiome at 1 and 3 months (Fig. 2a). Bifidobacteria occupancy was significantly lower in AED cases than in non-AED cases in 1-month-old infants, regardless of the use of ampicillin (ABPC) or CEZ (p < 0.001). In contrast, in 3-month-old infants, occupancy was not affected by AED. The Bacteroides population was markedly lower in the CEZ group at both 1 and 3 months than in the non-AED group (p < 0.001) and this tendency was also noted in the ABPC group. A significant difference was also found between AED and the non-AED groups (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the β diversity and occupancy of the top two bacteria species in the AED and non-AED groups. (a) Comparison of β diversity of the intestinal microbiome between infants at each age with (AED) and without (non-AED) antibiotic exposure at delivery. (b) Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides occupancies in infants in the AED and non-AED groups, shown as box-whisker plots at each age. The AED group was also divided into ampicillin-treated (ABPC) and cefazolin-treated (CEZ) groups. Comparison of occupancy among these groups and the non-AED group was performed using Bonferroni multiple comparison test. Comparison between the AED and non-AED groups was performed using Mann–Whitney U-test. The ABPC, CEZ, and non-AED groups included 43, 31, and 56 infants at 1 month (130 in total); 42, 27, and 58 infants at 3 months (127 in total); and 40, 28, and 58 infants at 6 months (126 in total). The significance level was set at 5%. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 This figure was generated using SAS version 9.4 (https://www.sas.com).

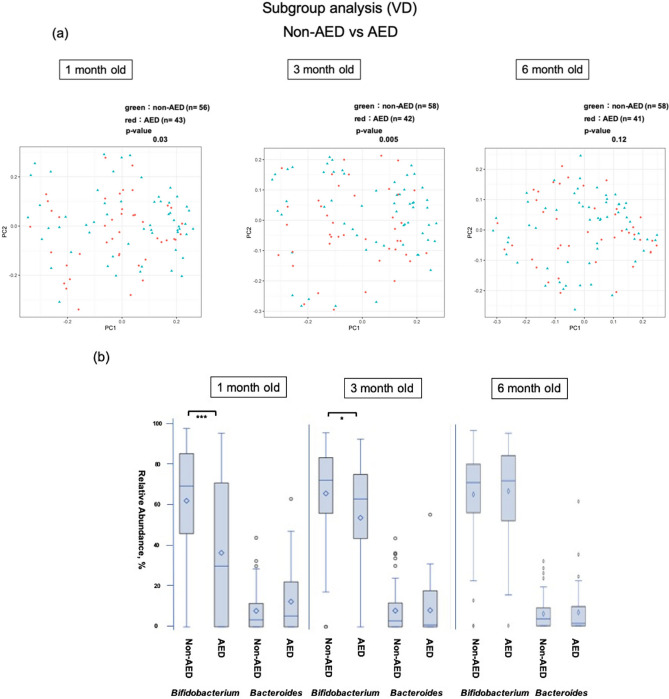

In a sub-group analysis of AED in vaginal delivery cases without CEZ administration (i.e., excluding infants born by caesarean section), there was a significant difference in diversity (p = 0.03) (Fig. 3a). Bifidobacteria occupancy in 1-month-old infants was significantly lower in the AED group (all were included in the ABPC group) (p < 0.001), and a significant difference was also noted at 3 months (p < 0.05). In contrast, occupancy of Bacteroides did not differ between these two groups (Fig. 3b). In the AED group, the exposure to antibiotics did not affect the Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides populations in the PROM and GBS-positive groups (Supplementary Fig. S1 online).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the β diversity and occupancy of the top two bacteria species in the AED and non-AED groups of the vaginal delivery group. (a) Comparison of β diversity of the intestinal microbiome between infants at each age with (AED) and without (non-AED) antibiotic exposure at vaginal delivery. (b) Comparison of Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides occupancies in infants in the AED and non-AED groups with vaginal delivery, shown as box-whisker plots at each age. The AED and non-AED groups included 43 and 56 infants at 1 month (99 in total), 42 and 58 infants at 3 months (100 in total), and 41 and 58 infants at 6 months (99 in total). The significance level was set at 5%. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 using Mann–Whitney U-test. This figure was generated using SAS version 9.4 (https://www.sas.com).

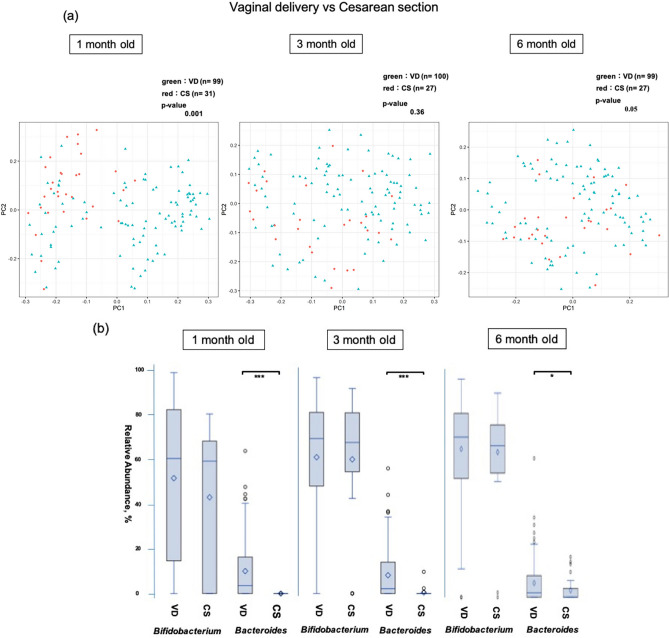

Effects of the delivery method

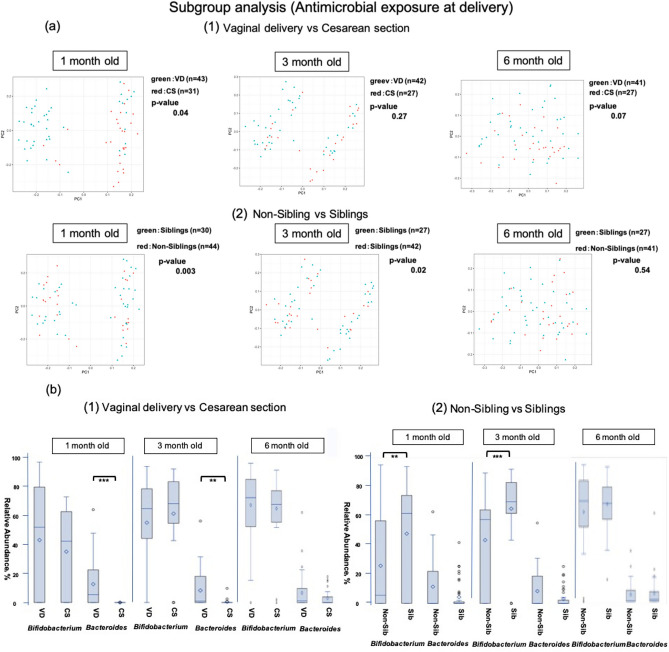

The delivery method significantly influenced the diversity of the intestinal microbiome at 1 month (Fig. 4a). The occupancy of Bifidobacteria did not differ with age, whereas that of Bacteroides was significantly lower in 1- and 3-month-old infants born via caesarean section (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4b). A comparison of delivery methods within the AED group gave similar findings (Fig. 5a,b).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the β diversity and occupancy of the top two bacteria species in the vaginal delivery (VD) and caesarean section (CS) groups. (a) Comparison of β diversity of the intestinal microbiome at each age between vaginal delivery (VD) and caesarean section (CS) (b) Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides occupancies between delivery methods, shown as box-whisker plots at each age. The VD and CS groups included 99 and 31 infants at 1 month (130 in total), 100 and 27 infants at 3 months (127 in total), and 99 and 27 infants at 6 months (126 in total). The significance level was set at 5%. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 using Mann–Whitney U-test. This figure was generated using SAS version 9.4 (https://www.sas.com).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the β diversity and occupancy of the top two bacteria species in the vaginal delivery (VD) and caesarean section (CS) groups of the AED group. (a) Comparison of β diversity of the intestinal microbiome at each age between delivery methods (1) and with and without siblings (2) in the AED group. VD: vaginal delivery, CS: caesarean section, Non-Siblings: infants without a sibling, Siblings: infants with older siblings. (b) Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides occupancies in the AED group compared between delivery methods (1) and presence of absence of siblings (2), shown as box-whisker plots at each age. (1) The vaginal delivery (VD) and caesarean section (CS) groups included 43 and 31 infants at 1 month (74 in total); 42 and 27 infants at 3 months (69 in total), and 42 and 27 infants at 6 months (68 in total). (2) The Sib and non-Sib groups included 44 and 30 infants at 1 month (74 in total), 42 and 27 infants at 3 months (69 in total), and 41 and 27 infants at 6 months (68 in total). The significance level was set at 5%. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 using Mann–Whitney U-test. This figure was generated using SAS version 9.4 (https://www.sas.com).

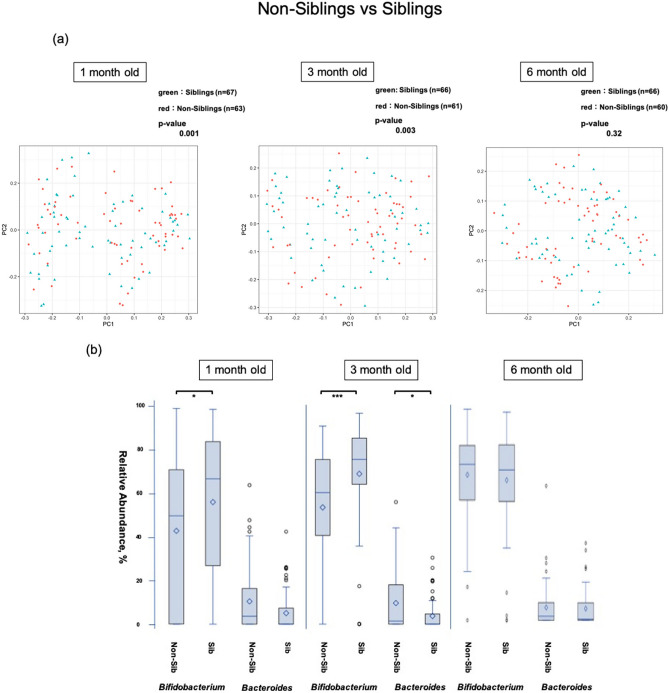

Effects of siblings

The presence of siblings significantly changed the diversity of the intestinal microbiome at 1 and 3 months (Fig. 6a). Bifidobacteria occupancy was significantly higher in 1-month-old (p = 0.001) and 3-month-old (p < 0.001) infants with siblings. Occupancy of Bacteroides did not differ at 1 month but was significantly lower in infants with siblings at 3 months (p < 0.05). At 6 months, there was no significant difference in occupancy for either genus (Fig. 6b). Sub-group analysis within the AED group also showed a significant change in the diversity of the intestinal microbiome at 1 and 3 months (Fig. 5a), and bifidobacterial occupancy was significantly higher in 1- and 3-month-old infants with siblings (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 5b).

Figure 6.

Comparison of the β diversity and occupancy of the top two bacteria species between the infants with siblings and those without siblings (a) Comparison of β diversity of the intestinal microbiome between infants with and without siblings. (b) Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides occupancies between infants with siblings (Sib) and without siblings (Non-Sib), shown as box-whisker plots at each age. The Sib and non-Sib groups included 67 and 63 infants at 1 month (130 in total), 61 and 66 infants at 3 months (127 in total), and 66 and 60 infants at 6 months (126 in total). The significance level was set at 5%. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 using Mann–Whitney U-test. This figure was generated using SAS version 9.4 (https://www.sas.com).

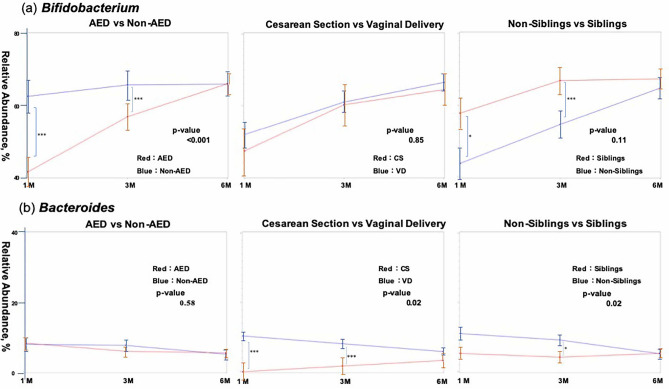

Time-course changes in Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides (linear mixed-effect model)

Comparison of bifidobacterial occupancy in AED and non-AED infants using a linear mixed-effects model (Fig. 7a) showed a significant difference over 6 months after birth, with lower occupancy in the AED group, but the difference in occupancy decreased with time. There was, however, no difference seen due to the delivery method. Occupancy appeared to be higher in infants with siblings, but there was no significant difference by the sixth month. Occupancy of Bacteroides did not differ significantly between the AED and non-AED groups (Fig. 7b), but the occupancy was lower in the caesarean section group and in infants with siblings.

Figure 7.

Time-course changes in bifidobacterial (a) and Bacteroides (b) occupancies (from 1 to 6 months after birth) based on AED or non-AED, delivery method, and the presence or absence of siblings, using a linear mixed-effect model. The analysis set at 1 month included 130 infants. Dropouts at 3 and 6 months were handled as missing values. The standard deviation by age in months is shown in bar form in each figure. Significant differences in occupancies between the two groups at each time point are also indicated in each comparison. The significance level was set at 5%. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 using the Mann–Whitney U-test. This figure was generated using SAS version 9.4 (https://www.sas.com).

Discussion

The results of this study indicated that the diversity of the intestinal microbiome was influenced by AED, delivery method, and siblings, with significant effects on Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides populations, which remained dominant at a combined occupancy of 60–70% in infants aged up to 6 months. These findings confirm the results of an earlier pilot study44 in 1-month-old infants.

AED to β-lactamase antibiotics has a major influence on Bifidobacteria population in early infants regardless of the use of ABPC or CEZ, with the influence being especially marked in 1-month-old infants. The influence of ABPC persisted until 3 months, but then gradually weakened and mostly disappeared by the sixth month. These results also conform with those of the pilot study44. Several previous studies have suggested a minor effect of IAP on the Bifidobacteria occupancy. However, these studies were limited to use of antibiotics for specific reasons, such as for GBS-positive mothers45, 46 or in the late stage of delivery30, and the study design and screening timeline of the intestinal microbiome were inconsistent. Although there has been a previous study38 on the effect of cefuroxime administration to mothers on the gut composition of infants immediately after delivery (10 days) and after weaning (9 months), the present study is the first, to the best of our knowledge, to evaluate the effects of antibiotic administration to mothers immediately before delivery on 1-, 3-, and 6-month-old infants, including the cases of caesarean section. The study comprised a statistically appropriate number of samples, thereby allowing sub-group analyses. The effects were evaluated until 6 months after birth using a 16S rRNA-targeting next-generation sequencer.

The delivery method (vaginal vs caesarean section) did not affect the Bifidobacteria occupancy in 1-month old infants, but there was a significant difference in the CEZ and non-AED groups. The delivery method did affect the Bifidobacteria population between the ABPC and CEZ groups. Thus, Bifidobacteria occupancy was significantly influenced in the caesarean section and CEZ groups compared to non-AED infants, but this effect did not change due to AED in the vaginal delivery group (i.e., the ABPC group). These results suggest that β-lactam antibiotics may directly influence bifidobacterial occupancy. Influence of the delivery method on Bifidobacteria population from immediately after birth to early infancy has been shown previously40, 47–50, but the influence of antibiotics administered before caesarean section36, 37, 51 was not considered in these studies, and this effect may have been simultaneously observed. The present study is not capable of judging whether the observed effect is due to the infant not passing through the birth canal in caesarean section or CEZ. Further studies with the use of the same antibiotics for vaginal delivery and caesarean section are therefore warranted.

Bifidobacteria colonisation was also influenced by the presence or absence of siblings. Bifidobacteria occupancy in AED infants was significantly higher in those with siblings. The results suggested that at least until 3 months after birth, the presence of an elder sibling promoted the colonisation of Bifidobacteria, even in infants exposed to antibiotics at delivery, i.e., there may be mutual interference of the microbiome between siblings. This may explain the maintenance of high Bifidobacteria occupancy in infants, even in the AED group. In a previous pilot study44, the presence of siblings was suggested to influence IAP, and the present study confirmed this effect. Previous studies on the effects of siblings have reported that Bifidobacteria colonisation occurs more easily in infants with siblings19, 40, 41. However, this effect has been scarcely studied as compared to studies on factors such as AED and the delivery method, particularly in Japanese infants. Thus, the present study is significant in showing the effect of siblings in a large cohort study. This effect was confirmed using a sub-group analysis within the AED group to allow interpretation in the context of AED. The association of this effect with the intestinal microbiome of siblings requires a continuous study, including siblings living together.

The influence of the caesarean section was more substantial than that of AED in Bacteroides. This effect was firmly maintained at 3 months and persisted at least until 6 months after birth. The same tendency was observed in the sub-analysis of the AED group. This confirmed that birth via caesarean section is an important factor in the occupancy of Bacteroides, compared to AED. A similar persistence of the influence of the caesarean section on Bacteroides until the weaning period and thereafter has been previously reported34, 40, 50, 52, 53. However, as described above, all caesarean section cases received preoperative CEZ. Thus, although the Bacteroides population was not influenced by ABPC, it may have been markedly influenced by CEZ. This possibility should be examined in future studies.

The Bacteroides population was not affected by siblings at 1 month, but a significant effect was seen at 3 months, with no influence at 6 months. In contrast to Bifidobacteria, siblings negatively influenced the occupancy of Bacteroides. The influence of siblings on the Bacteroides population has been shown before40, with the occupancy by Bacteroides at 18 months after birth being higher in infants with siblings, in contrast to the findings of this study until 6 months of age54. Similar to the effect seen on Bifidobacteria, the effect on Bacteroides until 3 months may reflect mutual interference among siblings.

Many studies have examined the clinical significance of colonisation of the intestinal microbiome with Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides in early infancy17–22. The present study evaluated the influence of AED on early infants in terms of the effects on their subsequent health. The samples from this study were also used to assess the relation of allergies with changes in the intestinal microbiome. This study was performed as a part of a cohort study evaluating the clinical significance of changes in the intestinal microbiome during early infancy in healthy Japanese infants and their effect on the intestinal microbiome later in life. Data at 1, 3, and 6 months after birth were used in this study, but data related to longer-term time-course changes in the same individuals are needed for a complete and comprehensive investigation. The composition of the intestinal microbiome shows substantial similarities at different time-points in the same individual55, but external factors influencing the intestinal microbiome increase with growth, such as the increase in baby food intake, interaction with siblings and other infants in group nursing, and further use of antibiotics for various diseases. However, this study is significant as a cohort study with a statistically significant large number of samples of the intestinal microbiome of infants in the first 6 months of life, which is a crucial period for the development of the immune system as this is a time at which external factors have the least influence in the entire lifetime24–26.

Despite its importance, the present study is not without limitations. With regard to the possibility of the AED and differences in delivery modes in this study affecting Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides, a strong “relationship” was observed. However, this study is a prospective cohort follow-up observation study, and comparative experimental studies are needed to confirm more robust causal relationship, together with follow-up observations. This study was conducted in a single hospital, which does not allow for extrapolation of the obtained results to the population from other regions within Japan and beyond, with differences in ethnicity or geography. Although the protocol for the use of antimicrobial agents before the delivery was similar to that in previous studies on IAP27, 29, multi-centre studies are needed for validation of such extrapolations. Additionally, while this study focused on several factors that could have a significant impact on the gut microbiota of infants, it did not account for some factors such as feeding methods as infants fed solely on milk were not included; thus, comparison of the feeding methods is not adequate. These points will likely cause a selection bias, which could affect colonisation characteristics of certain bacteria in the intestinal microbiota of infants. Inclusion of another group of infants that were milk-fed for the most part along with top feed is imperative to understand the factors influencing gut microbiota in infants. Moreover, occupancy was used in the comparison of bacteria in this study. A qualitative assessment based on qPCR is required to accurately assess the effect of factors such as AED and delivery method, rather than a relative assessment based on occupancy as was done in this study56, 57.

Conclusions

This prospective cohort study confirmed the findings from a previous pilot study indicating that β-lactam antibiotics administered to mothers immediately before delivery significantly influence the intestinal microbiome of healthy Japanese infants at 1 and 3 months after birth. This effect is more substantial than the effect of the delivery method on the dominant bacterial genus Bifidobacterium. The evaluation of the influence of AED requires the inclusion of all antibiotics used immediately before delivery, including before the caesarean section. The presence of siblings also affects Bifidobacteria colonisation, and this effect persists until 3 months and increases with time. In contrast, for Bacteroides, the influence of the delivery method is greater than that of AED. However, it is unclear whether this is an influence of delivery via caesarean section or CEZ administration. These results provide a new perspective on essential factors influencing the intestinal microbiome in early infancy, which is vital for the development of intestinal immunity. The clinical significance of the results in the later life of the infants requires further long-term studies.

Methods

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experimental procedures used in the study complied with the ethical standards of national guidelines of the Japanese government on human experimentation and the Declaration of Helsinki 1975, as revised in 2008. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Iwate Prefectural Iwai Hospital (No. 1234) and Juntendo University (No. 2017127). Written informed consent for participation and publication was obtained from all mothers.

Subjects

This prospective cohort study was performed as a part of a study investigating the association of allergic diseases with time-course changes observed in the microbiome in infants. The subjects included 142 infants and their mothers, who gave consent to registration before delivery or 2 weeks after delivery at Iwate Prefectural Iwai Hospital between February 2018 and March 2019. This hospital is in the Tohoku (Northeast) region of Japan and handles about 800 deliveries each year as a core perinatal medical care centre in the southern Iwate prefecture.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: infants born at full-term with natural delivery or caesarean section, whose mothers had not been exposed to antibiotics for 1 month before delivery, except for the antimicrobial used just before the delivery. Faecal samples were collected at 1, 3, and 6 months after birth by the parents.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: premature babies born before 37 weeks of gestation; if the babies received any antibiotics during first 6 months from their birth, the samples collected were handled as dropouts. If the sample collection was missed, the infant was considered as a dropout at that age and after that. If a sample was inappropriate for MiSeq analysis and could not be analysed, data for this infant were excluded from the analysis only at this time-point, whereas the analytical results for the infant at all other ages were used.

During IAP at delivery, a single dose of CEZ (1 g) was given systemically to mothers for all caesarean sections just before the surgery. ABPC (2 g) was given at least 4 h before delivery, followed by intermittent administration every 6 h until delivery in GBS-positive and PROM cases. Antibiotics were administered to all subjects at the dose and time defined in the clinical protocol determined by the hospital board.

Containers for collection of faecal samples at 1 month after birth were handed to mothers during hospitalisation for delivery or at the infant health examination 2 weeks after delivery. The container for the collection of faecal samples at 3 months was sent by mail to the address of each registered infant from Core Technology Laboratories, Asahi Group Holdings, and the container for 6 months was sent by mail from the Department of Microbiome Research, Juntendo University. Each faecal sample collected by the infants' parents was transferred to a test tube (Techno Suruga Laboratory, Shizuoka, Japan) containing 0.001% bromothymol and 100 mM Tris–HCl (pH 9), 40 mM EDTA, 4 M guanidine thiocyanate, and was mixed well as described in a previous study58. Mixed faecal samples were delivered to a laboratory of Asahi Group Holdings (Sagamihara, Kanagawa, Japan) within one or two days from Ichinoseki city, Iwate prefecture, where most of the enrolled infants resided (the distance between the two locations is approximately 480 km), and were stored at − 80 °C until processing for DNA extraction. The test tubes containing the samples were dissolved in a solution (provided in the kit mentioned above), which ensured that the composition of the intestinal microbiome present within the body was stable even at room temperature58.

DNA extraction

The processed samples were subjected to DNA extraction, as described previously44. Briefly, the samples (2 mL) were transferred to plastic tubes, centrifuged at 14,000× g for 3 min, washed in 1.0 mL of phosphate-buffered saline, and centrifuged at 14,000× g. Pellets were re-suspended in 500 μL of extraction buffer (166 mM Tris/HCl, 66 mM EDTA, 8.3% sodium dodecyl sulphate, pH 9.0) and 500 μL of TE buffer-saturated phenol. Next, 300 mg of zirconium beads (0.1 mm diameter) was added to the suspension, and the mixture was vortexed vigorously for 60 s × 3 times using a Multi-Beads Shocker (Yasui Kikai Corp., Osaka, Japan). After centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 5 min, 400 μL of the supernatant was purified using a Maxwell Instrument (Promega KK, Tokyo, Japan).

Sequencing and data processing

16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed using a MiSeq V3 kit as per the manufacturer's protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Briefly, the V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rDNA was amplified using PCR with forward and reverse primers (5′-TCG GCA GCG TCA GAT GTG TAT AAG AGA CAG CCT ACG GGA GGC WGC AG-3′ and 5′-GTC TCG TGG GCT CGG AGA TGT GTA TAA GAG ACA GGA CTA CHV GGG TAT CTA ATC C-3′) with the TaKaRa Ex Taq HS Kit (TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan) from 5 ng of DNA from faecal samples. After the PCR products were purified with Agencourt AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and amplified using a Nextera XT Index Kit v2 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). After the second round of PCR, the products were again purified using Agencourt AMPure XP. The library was quantified, normalised, and pooled in equimolar amounts. Sequencing was conducted using a paired-end 2 × 300-bp cycle run on an Illumina MiSeq system with a MiSeq Reagent Kit v.3 (600 cycles).

16S rRNA-based taxonomic and diversity analysis

QIIME2 (Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology, http://qiime2.org/) v.2019.4.0. was used for sequence analysis59. The sequence quality control, removing chimeric sequences and feature table construction were performed with the DADA2 plugin60. The primers sequence were trimmed and the remaining forward and reverse sequences were truncated to a final length of 280 bp. Phylogenetic diversity analyses were carried out with q2-phylogeny and q2-diversity, and beta diversity was visualised using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). The feature classifiers were performed with q2-feature-classifier plugin using “gg-13-8-99-nb-classifier.qza.” from the greengenes database as reference sequences.

Data collection

The following data were collected from medical records at Iwate Prefectural Iwai Hospital: delivery method, gender, body weight at birth, perinatal history, records of hospital visits, and treatments received by the infant up to 6 months after birth including the use of antibiotics after birth. Additional information related to age (days) at sample collection, feeding method (breastfeed exclusively or added top feed), and siblings were obtained from a questionnaire completed by the mothers. The following data about the mothers were also collected from medical records and a questionnaire: age, delivery method, history of allergies (food allergy, bronchial asthma, atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis), abnormal findings at delivery (including PROM and GBS-positive status), antimicrobial use during late pregnancy, and systemic antibiotics (including types) given at delivery.

Statistical analysis

The significance of the difference between the two groups was analysed using a non-parametric ANOSIM (analysis of similarities) test based on unweighted UniFrac distances within QIIME2 (https://qiime2.org/). Acquired 16S rRNA gene data for bacteria were analysed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Background factors of the mother and child were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables and the Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables. The influence of each background factor on occupancies by higher-rank dominant bacterial genera in the intestinal microbiome at each age was examined using logistic regression analysis and multinomial logistic regression for categorical variables and continuous variables, respectively. The dependence of occupancy of each bacterial genus on factors, for which a significant association was found in diversity analysis and logistic regression analysis, was examined using a Mann–Whitney U-test for between-group comparison and using a Kruskal–Wallis test with a Bonferroni correction for multiple group comparison. Continuous comparative changes of dominant bacterial genera due to different factors were analysed using a linear mixed-effect model (random intercept and first-order autoregression model). The significance level was set at p < 0.05 in all analyses.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

N.I., Y.A., H.M., and F.A. designed the study. S.W., N.H., and H.M. evaluated, corrected, and reviewed the study. N.I., Y.A., C.K., F.A., and H.M. implemented the study (explanation to parents, distributing sample containers, and collecting questionnaires). Y.A., C.K., and H.M. performed storage, processing, and analysis using MiSeq of samples. N.I., Y.A., and C.K. performed data management and statistical analysis. N.I. drafted the manuscript. S.W., N.H., F.A., and H.M. corrected and reviewed the manuscript. S.N. supervised the statistical methods and examined the validity of the analysis. All authors read and approved the content of the manuscript, including the accuracy of the data, ethical legitimacy, and validity of the results.

Data availability

The data generated during the current study are available in the Figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12000255), and the sequencing data is deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ; accession number: DRA010467).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-85670-z.

References

- 1.Kundu P, Blacher E, Elinav E, Pettersson S. Our gut microbiome: the evolving inner self. Cell. 2017;171:1481–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turroni F, et al. Diversity of bifidobacteria within the infant gut microbiota. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumbhare SV, et al. A cross-sectional comparative study of gut bacterial community of Indian and Finnish children. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:10555. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11215-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurokawa K, et al. Comparative metagenomics revealed commonly enriched gene sets in human gut microbiomes. DNA Res. 2007;14:169–181. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsm018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakayama J, et al. Diversity in gut bacterial community of school-age children in Asia. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8397. doi: 10.1038/srep08397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishijima S, et al. The gut microbiome of healthy Japanese and its microbial and functional uniqueness. DNA Res. 2016;23:125–133. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsw002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagpal R, et al. Evolution of gut Bifidobacterium population in healthy Japanese infants over the first three years of life: a quantitative assessment. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:10097. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10711-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benno Y, Sawada K, Mitsuoka T. The intestinal microflora of infants: composition of fecal flora in breast-fed and bottle-fed infants. Microbiol. Immunol. 1984;28:975–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1984.tb00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mikami K, et al. Influence of maternal bifidobacteria on the establishment of bifidobacteria colonizing the gut in infants. Pediatr. Res. 2009;65:669–674. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819ed7a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vernocchi P, Del Chierico F, Putignani L. Gut microbiota profiling: Metabolomics based approach to unravel compounds affecting human health. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1144. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen L, Duffy A. Factors influencing the gut microbiota, inflammation, and type 2 diabetes. J. Nutr. 2017;147:1468s–1475s. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.240754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bien J, Palagani V, Bozko P. The intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and Clostridium difficile infection: is there a relationship with inflammatory bowel disease? Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2013;6:53–68. doi: 10.1177/1756283X12454590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houghteling PD, Walker WA. Why is initial bacterial colonization of the intestine important to infants' and children's health? J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015;60:294–307. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamburini S, Shen N, Wu HC, Clemente JC. The microbiome in early life: implications for health outcomes. Nat. Med. 2016;22:713–722. doi: 10.1038/nm.4142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fanaro S, Chierici R, Guerrini P, Vigi V. Intestinal microflora in early infancy: composition and development. Acta Paediatr. Suppl. 2003;91:48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2003.tb00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gore C, et al. Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum is associated with atopic eczema: a nested case-control study investigating the fecal microbiota of infants. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008;121:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abrahamsson TR, et al. Low diversity of the gut microbiota in infants with atopic eczema. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012;129:434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penders J, et al. Establishment of the intestinal microbiota and its role for atopic dermatitis in early childhood. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;132:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong P-Y, et al. Comparative analysis of fecal microbiota in infants with and without eczema. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Zwol A, et al. Intestinal microbiota in allergic and nonallergic 1-year-old very low birth weight infants after neonatal glutamine supplementation. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:1868–1874. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouwehand AC, et al. Differences in Bifidobacterium flora composition in allergic and healthy infants. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001;108:144–145. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.115754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki S, Shimojo N, Tajiri Y, Kumemura M, Kohno Y. Differences in the composition of intestinal Bifidobacterium species and the development of allergic diseases in infants in rural Japan. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2007;37:506–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vangay P, Ward T, Gerber JS, Knights D. Antibiotics, pediatric dysbiosis, and disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rasmussen SH, et al. Antibiotic exposure in early life and childhood overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018;20:1508–1514. doi: 10.1111/dom.13230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson CC, Ownby DR. Allergies and asthma: Do atopic disorders result from inadequate immune homeostasis arising from infant gut dysbiosis? Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2016;12:379–388. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2016.1139452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzola G, et al. Early gut microbiota perturbations following intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent group B Streptococcal disease. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0157527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hussey S, et al. Parenteral antibiotics reduce bifidobacteria colonization and diversity in neonates. Int. J. Microbiol. 2011;2011:130574. doi: 10.1155/2011/130574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aloisio I, et al. Evaluation of the effects of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis on newborn intestinal microbiota using a sequencing approach targeted to multi hypervariable 16S rDNA regions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016;100:5537–5546. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Penders J, et al. Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. Pediatrics. 2006;118:511–521. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adlerberth I. Factors influencing the establishment of the intestinal microbiota in infancy. Nestle Nutr. Workshop Ser. Pediatr. Prog. 2008;62:13–33. doi: 10.1159/000146245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adlerberth I, Wold AE. Establishment of the gut microbiota in Western infants. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:229–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hill CJ, et al. Evolution of gut microbiota composition from birth to 24 weeks in the INFANTMET Cohort. Microbiome. 2017;5:4. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0213-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jakobsson HE, et al. Decreased gut microbiota diversity, delayed Bacteroidetes colonisation and reduced Th1 responses in infants delivered by caesarean section. Gut. 2014;63:559–566. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bäckhed F, et al. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:690–703. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costantine MM, et al. Timing of perioperative antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a metaanalysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;199(301):e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smaill FM, Grivell RM. Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for preventing infection after cesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014;10:CD007482. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007482.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamal SS, et al. Impact of early exposure to cefuroxime on the composition of the gut microbiota in infants following cesarean delivery. J. Pediatr. 2019;210:99–105.e102. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tannock GW, et al. Comparison of the compositions of the stool microbiotas of infants fed goat milk formula, cow milk-based formula, or breast milk. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:3040–3048. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03910-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin R, et al. Early-life events, including mode of delivery and type of feeding, siblings and gender, shape the developing gut microbiota. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0158498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yap GC, et al. Evaluation of stool microbiota signatures in two cohorts of Asian (Singapore and Indonesia) newborns at risk of atopy. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:193–193. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Itani T, et al. Establishment and development of the intestinal microbiota of preterm infants in a Lebanese tertiary hospital. Anaerobe. 2017;43:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poroyko V, et al. Diet creates metabolic niches in the "immature gut" that shape microbial communities. Nutr. Hosp. 2011;26:1283–1295. doi: 10.1590/S0212-16112011000600015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Imoto N, et al. Maternal antimicrobial use at delivery has a stronger impact than mode of delivery on bifidobacterial colonization in infants: a pilot study. J. Perinatol. 2018;38:1174–1181. doi: 10.1038/s41372-018-0172-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nogacka A, et al. Impact of intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis upon the intestinal microbiota and the prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes in vaginally delivered full-term neonates. Microbiome. 2017;5:93–93. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0313-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tapiainen T, et al. Impact of intrapartum and postnatal antibiotics on the gut microbiome and emergence of antimicrobial resistance in infants. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:10635. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46964-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huurre A, et al. Mode of delivery - effects on gut microbiota and humoral immunity. Neonatology. 2008;93:236–240. doi: 10.1159/000111102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Biasucci G, et al. Mode of delivery affects the bacterial community in the newborn gut. Early Hum. Dev. 2010;86(Suppl 1):13–15. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee E, et al. Dynamics of gut microbiota according to the delivery mode in healthy Korean infants. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2016;8:471–477. doi: 10.4168/aair.2016.8.5.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Azad MB, et al. Gut microbiota of healthy Canadian infants: profiles by mode of delivery and infant diet at 4 months. CMAJ. 2013;185:385–394. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan GJ, et al. The effect of intrapartum antibiotics on early-onset neonatal sepsis in Dhaka, Bangladesh: a propensity score matched analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fallani M, et al. Determinants of the human infant intestinal microbiota after the introduction of first complementary foods in infant samples from five European centres. Microbiology. 2011;157:1385–1392. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.042143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fallani M, et al. Intestinal microbiota of 6-week-old infants across Europe: geographic influence beyond delivery mode, breast-feeding, and antibiotics. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2010;51:77–84. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d1b11e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laursen MF, et al. Having older siblings is associated with gut microbiota development during early childhood. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:154–154. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0477-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turnbaugh PJ, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dierikx TH, et al. The influence of prenatal and intrapartum antibiotics on intestinal microbiota colonisation in infants: a systematic review. J. Infect. 2020;81:190–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shao Y, et al. Stunted microbiota and opportunistic pathogen colonization in caesarean-section birth. Nature. 2019;574:117–121. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1560-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nishimoto Y, et al. High stability of faecal microbiome composition in guanidine thiocyanate solution at room temperature and robustness during colonoscopy. Gut. 2016;65:1574–1575. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bolyen E, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:852–857. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Callahan BJ, et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated during the current study are available in the Figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12000255), and the sequencing data is deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ; accession number: DRA010467).