Abstract

ICAM-1 is a cell surface glycoprotein and an adhesion receptor that is best known for regulating leukocyte recruitment from circulation to sites of inflammation. However, in addition to vascular endothelial cells, ICAM-1 expression is also robustly induced on epithelial and immune cells in response to inflammatory stimulation. Importantly, ICAM-1 serves as a biosensor to transduce outside-in-signaling via association of its cytoplasmic domain with the actin cytoskeleton following ligand engagement of the extracellular domain. Thus, ICAM-1 has emerged as a master regulator of many essential cellular functions both at the onset and at the resolution of pathologic conditions. Because the role of ICAM-1 in driving inflammatory responses is well recognized, this review will mainly focus on newly emerging roles of ICAM-1 in epithelial injury-resolution responses, as well as immune cell effector function in inflammation and tumorigenesis. ICAM-1 has been of clinical and therapeutic interest for some time now; however, several attempts at inhibiting its function to improve injury resolution have failed. Perhaps, better understanding of its beneficial roles in resolution of inflammation or its emerging function in tumorigenesis will spark new interest in revisiting the clinical value of ICAM-1 as a potential therapeutic target.

Keywords: adhesion molecules, immune cells, Inflammation, metastasis, migration, tumorigenesis, wound healing

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Adhesion molecules are critical regulators of cellular function, tissue integrity, and homeostasis. These adhesive receptors not only mediate cell-to-cell interactions, but through association with the cell cytoskeleton and various adaptor proteins trigger intracellular signaling events in response to specific and local cues.1,2 As such, adhesion molecules help form endothelial and epithelial barriers via signal transduction and homotypic interactions at cellular junctions, while providing structural support and binding scaffold for extracellular matrix (ECM), glycocalix, and many resident or recruited cell types via heterotypic interactions at the basal and apical membranes.2

ICAM-1 is a cell surface glycoprotein expressed at a low basal level in immune, endothelial (EC) and epithelial cells, but is up-regulated in response to inflammatory stimulation.3 The function of ICAM-1 has been best studied in leukocyte transendothelial migration (TEM), where ICAM-1 regulates leukocyte rolling and adhesive interactions with the vessel wall, and guides leukocyte crossing of the endothelial layer.4,5 More recently, functional studies identified several new roles of ICAM-1 in epithelial injury-resolution responses, innate and adaptive immune responses in inflammation, and tumorigenesis.6

Thus, ICAM-1 has emerged as a master regulator of many essential tissue functions both at the onset and the resolution of pathologic conditions. ICAM-1 has been of clinical and therapeutic interest for some time now; however, inhibition of ICAM-1 function has not yielded significant clinical impact in improving injury resolution.7–9 Perhaps, with a better understanding of its various roles in health and disease and new mechanistic insights into its function, the clinical value of ICAM-1 could be revisited for improvement of therapeutic strategies. This review will summarize the emerging aspects of ICAM-1 biology, its diverse functions in disease, and the potential diagnostic and therapeutic implications associated with this adhesion receptor.

2 |. ICAM-1 STRUCTURE AND FUNCTIONAL IMPLICATIONS DURING HOMEOSTASIS AND PATHOGENESIS

2.1 |. ICAM-1 structure, splice variants, and glycosylation

ICAM-1 belongs to the Ig superfamily and consists of five extracellular Ig domains, a transmembrane domain, and a short cytoplasmic domain.10 The molecular weight of ICAM-1 varies between 60 and 114 kDa, depending on the extent of glycosylation on the Ig domains.11 These glycosylated Ig domains mediate ICAM-1 interactions with its ligands. Upon ligation, ICAM-1 undergoes dimerization and clustering through homotypic binding between Ig domains 3 and 4,12 which significantly increases ICAM-1 binding affinity to its cognate ligands β2-integrins lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1; CD11a/CD18) and macrophage antigen 1 (Mac-1; CD11b/CD18).13,14 LFA-1 and Mac-1 are known to bind Ig domains 1 and 3, respectively.15

As with other Ig superfamily members, ICAM-1 is post-transcriptionally regulated by alternative splicing, which generates six membrane-bound variants and a secretable soluble protein (sICAM-1).16,17 Structural studies of ICAM-1 reported that all ICAM-1 isoforms consist of at least Ig domains 1 and 5, and the variable domains 2, 3, and 4, which define ICAM-1 binding specificity to its ligands.16 Thus, alternative splicing can dictate ICAM-1 function in various pathologic conditions.18 Supporting this idea, disrupting different Ig domains of ICAM-1 to generate knockout (KO) mouse models can differentially impact disease outcomes. For example, Icam1tm1Jcgr mice with truncated Ig domain 3 showed impaired neutrophil (polymorphonuclear neutrophils [PMN]) recruitment and exhibited resistance to endotoxic shock.18,19 In contrast, Icam1tm1Bay mice lacking isoforms with Ig domain 4 were highly susceptible to endotoxemia with undisturbed or even enhanced neutrophil infiltration.18,20

Intriguingly in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), whereas ICAM-1 is up-regulated by EC and many other cell types, disease symptoms were reduced in ICAM-1 null mice (Icam1tm1Alb) but were unexpectedly exacerbated in Icam1tm1Bay, possibly due to T-cell dysfunction.18,21,22 As with endotoxemia, Icam1tm1Jcgr were resistant to EAE with less immune cell infiltration.18,21,23 The findings underscore the potentially distinct roles of ICAM-1 splice variants in immune disorders.

Glycosylation is another factor that can significantly affect ICAM-1 function.24 ICAM-1 is heavily glycosylated, and variations in glycosylation were shown to result in distinct biologic functions.25 It has been shown that N-glycans on the Ig domains of ICAM-1 are required for retention of the receptor on the cell surface.24,26 In the context of leukocyte trafficking, high-mannose form of ICAM-1 was found to be more efficient at regulating monocyte rolling and adhesion, whereas the complex N-glycan form of ICAM-1 was required for cytoskeletal changes in ECs and thus in the regulation of vascular permeability.27 Furthermore, changes in protein glycosylation can alter cleavage by proteinases, thus impacting the release and the structure of sICAM-1.28 This will in turn impact ICAM-1 function, as will be discussed in following sections.

3 |. ICAM-1 EXPRESSION AND FUNCTION IN INFLAMMATION

ICAM-1 is expressed at low levels by EC, epithelial, and immune cells. ICAM-1 expression is highly induced by a variety of inflammatory cytokines; however, a degree of specificity among different cell types has been observed.3,29 For example, in ECs, ICAM-1 expression was induced by NFκB in response to TNFα or IL-1β stimulation,30 whereas in intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), ICAM-1 expression was induced by IFNγ, but not by TNFα or LPS treatment.31 In macrophages, IFNγ and LPS stimulation induced a robust up-regulation of ICAM-1 compared to relatively small effect of TNFα or IL-1β.32 ICAM-1 expression was also shown to be regulated by microRNA activity. MiR-141 in ECs was found to down-regulate ICAM-1, thus decreasing leukocyte adhesion and attenuating myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury.33 Because ICAM-1 is induced in many cell types during inflammatory responses, it is not surprising that ICAM-1 has been implicated in many physiologic processes, including leukocyte trafficking, immune cell effector functions, pathogen and dead cell clearance, and T-cell activation. Figure 1 demonstrates the expression of ICAM-1 on epithelial, EC, and immune cells in response to inflammation.

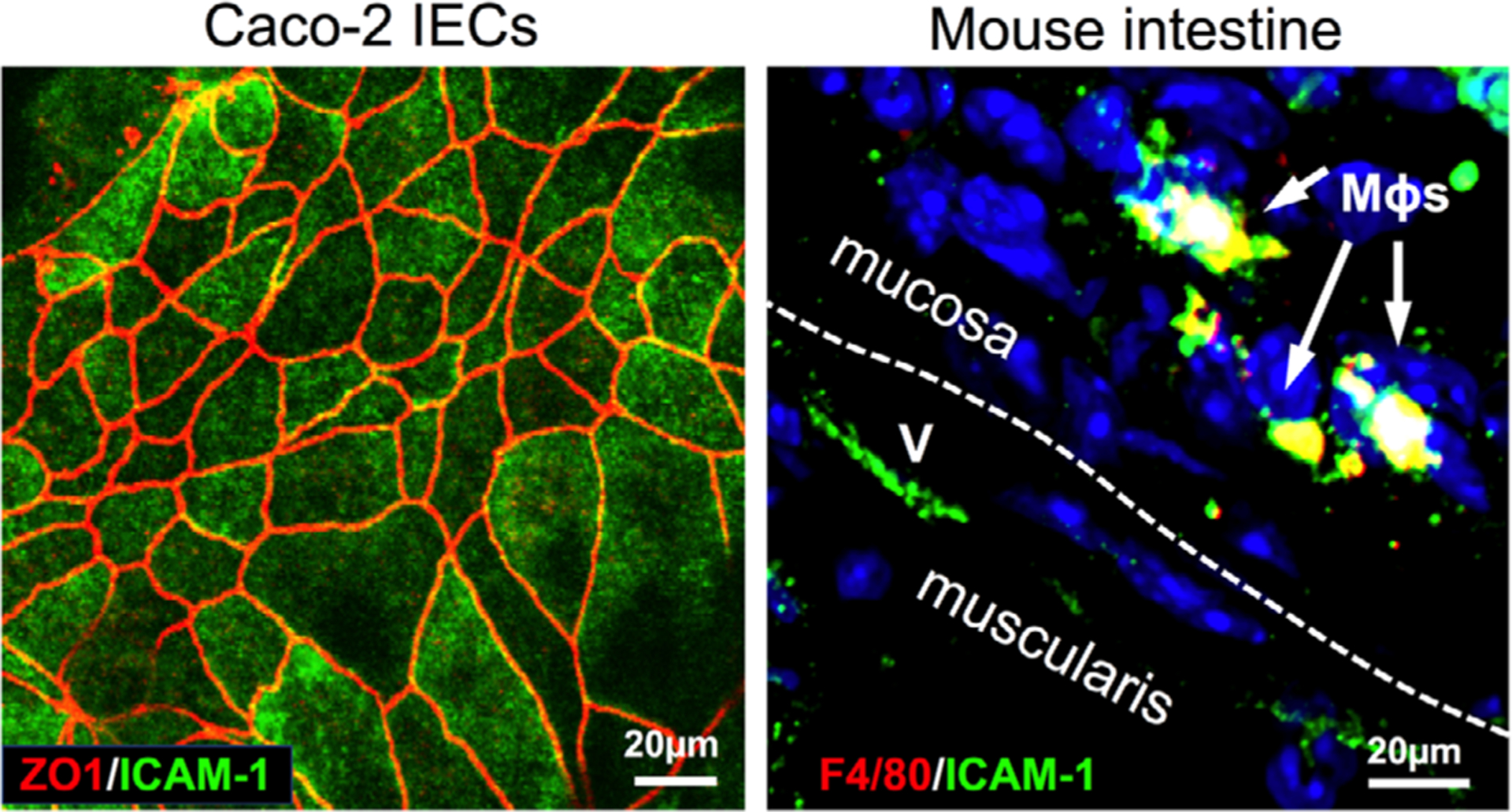

FIGURE 1. ICAM-1 expression on endothelial, epithelial, and immune cells.

Representative immunofluorescence images show ICAM-1 expression on the surface of intestinal epithelial cells, Caco2 (left, co-stained with the junctional molecule ZO-1), and on macrophages and endothelial cells in inflamed mouse colon tissue (right). Colon inflammation was induced by dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) treatment (3% weight/volume). Following 4 d of treatment colon tissue was extracted, sectioned, and stained using standard protocols. ICAM-1 expressing, F4/80 positive tissue MΦs shown by white arrows, (v) depicts blood vessels, the white dashed line separates the muscularis and mucosa layers. Scale bars represent 20μm

3.1 |. ICAM-1 regulates leukocyte trafficking and effector function

ICAM-1 is best known for its role in regulating leukocyte trafficking and TEM.34,35 The role of ICAM-1 in leukocyte-EC interactions has been well studied and elegantly summarized in several recent reviews36–38 and will not be discussed in detail. However, it is worth noting that in addition to its well-established role in mediating leukocyte firm adhesion to ECs, ICAM-1 has been shown to also mediate slow PMN rolling and luminal crawling.39–41

Intriguingly, in post-capillary venules, whereas expression of ICAM-1 was increased with inflammatory stimulus, high and low ICAM-1 expression regions along the vessel wall were observed.42 Not surprisingly, leukocyte interactions in these respective regions were increased or decreased accordingly.40 Moreover, ICAM-1 expression patterns varied among individual ECs and were also shown to actively redistribute and cluster around migrating leukocytes.43,44 ICAM-1 enrichment at the tricellular EC junction was also noted, marking these regions as preferred locations or “portals” of entry for PMN TEM.45

ICAM-1 contributions to immune cell effector function are also being increasingly recognized. For example, ICAM-1 expressed by dendritic or natural killer cells is important for T lymphocyte binding and formation of immune synapses.46–48 ICAM-1 expressed by T lymphocytes can deliver a co-stimulatory signal, which is required for T-cell activation,49,50 as well as contribute to programming of memory CD8 T cells in response to secondary stimuli.51 We recently demonstrated that ICAM-1 expression was highly induced in inflammatory macrophages, where it served as a phagocytic receptor and mediated binding of macrophages and apoptotic cells, facilitating apoptotic clearance.32 Finally, ICAM-1 expression was also induced on activated murine and human PMNs. In murine PMNs, LPS-driven induction of ICAM-1 expression was associated with enhanced reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and improved phagocytoses.52,53 Consistently, ICAM-1 expression was also detected on PMNs from patients with bacterial peritonitis and in septic patients with elevated levels of endotoxin.53,54 ICAM-1 expression significantly improved PMN effector function in both murine models and human disease.

3.2 |. ICAM-1 regulates endothelial and epithelial barrier function

In addition to mediating leukocyte adhesion, ICAM-1 also serves as a signaling receptor to transduce outside-in signaling, linking leukocyte adhesive interactions with epithelial and endothelial function.37,55 Specifically, ICAM-1 signals through the association of its cytoplasmic domain with the actin cytoskeleton. These interactions are facilitated via adaptor proteins, including ezrin, radixin, and moesin (ERM),56 actinin,57 b-tubulin,58 glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase,59 cortactin,60 Grb2,61 SOS, and Shc.62 ICAM-1 ligation by leukocytes or by crosslinking Abs, which effectively simulates leukocyte binding, has elucidated many signaling events that are induced downstream of ICAM-1. These include activation of Rho-GTPases,61 Src kinase and endothelial nitric synthase,63 MAP kinases,64 and protein kinase C (PKC)δ.65 By signaling through these effector molecules, ICAM-1 contributes to the regulation of critical barrier properties in ECs and epithelial cells. The various signaling pathways regulated by ICAM-1 are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

ICAM-1 signaling and function: a summary of ICAM-1 expression, signaling, and regulation of various cellular processes in health and disease as has been discussed in this review

| Cell type | Function | Interactions/signaling | Mechanism of action | Disease model | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endothelial cells | Leukocyte adhesion | Adhesive binding | Recruitment and retention of immune cells, Initiation of inflammatory responses | Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), colitis, Endotoxemia | 19–23, 42, 154 |

| Cell migration | Src kinase, PKCδ | Reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and cell shape, VEGF production and new vessel formation | Acute lung injury, ischemic injury, sterile inflammation | 46, 65, 144, 67 | |

| Barrier function | Ca2+ signaling | Myosin contractility, vascular permeability and immune cell trafficking | Brain injury/sterile inflammation | 69, 70, 68 | |

| Proliferation | Nitric synthase | Proliferation; new vessel formation | Lung inflammation | 69, 103 | |

| EC activation | MAPK-ERK1/2 | Reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton | Kidney injury | 152 | |

| Epithelial cells | Cell migration | Rac/Rho/Cdc42 | Reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and cell shape, Cell migration, Oncogenic transformation | Lung inflammation | 153 |

| Barrier function | JNK/p38, MLCK | Dissolution of adherens junctions, Loss of the apical F-actin, Cytoskeletal rearrangement | Lung injury, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) | 71, 73, 31, 80 | |

| Proliferation | Akt/β-catenin | Cell cycle progression and cell growth | Colon injury | 115 | |

| PMNs | ROS release | Not defined | PMN phagocytosis and cytotoxicity | Peritonitis | 52–54 |

| Macrophages | Efferocytosis | Adhesive binding | Phenotypic polarization, macrophage binding to apoptotic/necrotic cells | Intestinal injury | 113, 132, 32 |

| T cells | T-cell activation | PI3K | Co-stimulatory receptor for T-cell activation | Inflammation, cell cultures | 49–51 |

| Dendritic cells | T-cell activation | Not defined | Chemokines release for T-cell activation | Inflammation, cell cultures | 47–48 |

| Cancer cells | Cellular adhesion | Adhesive binding | TLS formation and increase tumor immunogenicity, CTCs retention at the vessel walls at metastatic sites | Breast cancer, melanoma, liver metastasis | 133, 139–141, 143, 144, 174–178 |

| Cell migration | MAPK-ERK1/2 (?) | Reorganization of cytoskeleton, cancer cell invasion | |||

| Transformation | Src kinase (?) | Oncogenic transformation |

In ECs, ICAM-1 has been shown to regulate intracellular Ca2+ levels and lead to activation of myosin contractility, both of which are critical for maintaining a functional barrier.66–68 Moreover, ICAM-1 has been shown to regulate EC permeability in healthy and inflamed tissue.44,69,70 Intriguingly, whereas in healthy tissue, ICAM-1 signaled through PKC activation to control barrier function, following inflammatory stimulation, ICAM-1 engagement by circulating leukocytes led to Src kinase activation to increase solute permeability.44 ICAM-1 was also shown to activate JNK and lead to internalization of VE-cadherin,70 causing disruption of the EC junction and impairment of EC barrier function.64 ICAM-1 could also modulate EC permeability by regulating cytokine production. ICAM-1 antibody-crosslink in HUVECs increased production of IL-8 and CCL5,64,71,72 where both molecules have been shown to impair EC permeability.73–75

ICAM-1 is similarly up-regulated in epithelial cells under inflammatory conditions where it primarily localizes to the apical surface.31,76–78 In gut epithelium, ICAM-1 expression has been shown to be markedly increased in active inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and in epithelial cells following inflammatory stimulation.31,79 Given its apical (luminal) localization, ICAM-1 has no direct role in mediating PMN migration across IECs as it does in endothelium; however, ICAM-1 promotes retention of transmigrated PMNs at the luminal epithelial surface.31 PMN ligation of ICAM-1 at the apical epithelial surface also triggered myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK)-dependent down-regulation of perijunctional F-actin, which increased intestinal epithelial permeability.31 In bronchial epithelial cells, ICAM-1 activation by clustering induced local activation of ERK1/2 to modulate permeability.80

ICAM-1 can further impact IEC permeability by facilitating ligation of other apically localized proteins by retained PMNs. One such protein is CD44, which similarly to ICAM-1, can associate with ERM proteins to regulate the actin cytoskeleton.81,82 In addition, CD44 via recruitment of metalloproteinases (MMP7 and 9) impairs junction assembly and thus compromises epithelial barrier function.83

3.3 |. Soluble ICAM-1 as an inflammatory biomarker

ICAM-1 can be also found as an sICAM-1 in numerous inflammatory disorders.84–87 sICAM-1 is produced as a spliced isoform or as a result of proteolytic cleavage.18,88 The splice variant of sICAM-1 is truncated at the transmembrane domain whereas it retains all five extracellular Ig domains similarly to full-length ICAM-1 molecule. In contrast, enzymatically cleaved forms of sICAM-1 may differ in the composition of their Ig domains depending on proteases that catalyzed the cleavage. It has been suggested that common proteases including elastase, cathepsins, and metalloproteases can mediate cleavage of ICAM-1, generating potentially structurally different forms of the protein.17,18 However, whether this also results in different biologic functions of sICAM-1 during inflammation is not yet determined.

sICAM-1 levels are elevated in animal disease models89–91 and in serum of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),92 asthma,93 sepsis,94 atherosclerosis,95 coronary heart disease,96 or cancer.97–99 Increases in sICAM levels were correlated with inflammation and several clinical studies used sICAM-1 as a surrogate marker to monitor response to therapy (particularly in clinical studies of cancer patients, will be discussed in the following text) or for classifying patients with infectious versus noninfectious systemic inflammatory response syndrome,87 as well as a variety of inflammatory disorders.89–91

sICAM-1 has been shown to promote both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses. Low levels of sICAM-1 have been shown to trigger activation of NFκB and ERK, leading to the release of inflammatory cytokines macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1a, MIP-2, TNFα, IFNγ, and IL-6 (summarized in37). In contrast, high levels of sICAM-1 enhanced EC migration and angiogenesis,100,101 competitively inhibited leukocyte-EC interactions,102 and promoted the pro-repair activity of immune cells.103 Several emerging roles of sICAM-1 in resolution of inflammation will be discussed in the following section.

4 |. ICAM-1 CONTRIBUTES TO RESOLUTION OF INFLAMMATION AND WOUND HEALING

Restoration of tissue homeostasis following pathogenic insult or injury initiates with inflammatory resolution, which involves clearance of inflammatory immune cells and reprogramming of tissue resident cells to pro-resolution phenotype.104,105 The subsequent tissue remodeling phase involves re-epithelization (restitution and regeneration of injured tissue), vascularization, and formation of new capillary networks.106 ICAM-1 function is typically associated with progressing inflammation; however, emerging evidence increasingly implicates ICAM-1 activity in resolution of inflammation and wound healing.

4.1 |. ICAM-1 and immune cell effector function in resolution of inflammation

Macrophages are professional phagocytes in charge of wound debridement and clearance of apoptotic/dead cells by efferocytosis.107,108 As such, macrophages play an important role in timely resolution of inflammation and successful wound healing.109,110 We found that ICAM-1 expressed by inflammatory macrophages played an important role in efferocytosis (clearance of apoptotic/dead cells) of immune and epithelial cells.32 Efferocytosis also leads to cellular reprogramming in newly recruited inflammatory macrophages, which in turn suppress inflammatory response and increase production of pro-resolution cytokines, including IL-10, TGF-β, and PGE2.111,112 Furthermore, ICAM-1 was found to directly impact macrophage polarization and promote the pro-repair phenotype by positively modulating miR-124 expression.113 Thus, by enhancing macrophage efferocytosis and the pro-repair reprograming, ICAM-1 can contribute to inflammatory resolution and tissue healing. ICAM-1 expressed by T cells was found to function as a co-stimulatory molecule to promote T-cell activation,50 where activated regulatory T cells promote the pro-repair function of macrophage by increasing efferocytosis and production of IL-10.114 Finally, ICAM-1 improved PMN effector function (ROS generation and phagocytoses) in murine endotoxemia model and septic patients to facilitate inflammatory resolution.52–54

4.2 |. ICAM-1 in epithelial and endothelial wound healing

ICAM-1 in epithelial cells has been implicated in regulating wound healing.115–117 In IECs, engagement of ICAM-1 by apically adherent PMNs induced Akt phosphorylation and Akt-dependent transcriptional activation of β-catenin, leading to increased IEC proliferation and wound re-epithelialization.115 Whereas colon wound healing was impaired in ICAM-1 KO mice, an induction of epithelial ICAM-1 signaling at the wound bed by ICAM-1-targeted immune complexes significantly improved colon wound healing, supporting the role of ICAM-1 in this process.115 Similarly, ICAM-1 has been shown to promote skin wound healing, where the loss of ICAM-1 has been linked to impaired keratinocyte migration, granulation tissue formation, and overall inhibition of wound healing. However, in this setting, impaired wound repair was associated with ICAM-1-dependent reduction in infiltrating neutrophils and macrophages.116 ICAM-1 in corneal epithelium has been shown to promote corneal wound repair by facilitating the recruitment and retention of γ/δ T cells, which are important mediators of resolution of inflammation and wound healing. With the loss of corneal epithelial ICAM-1, T-cell recruitment was impaired, as was epithelial cell division and subsequent re-epithelialization.118

Finally, ICAM-1 has also been implicated in EC migration and repair,101 which is critical for neovascularization of resealing wounds and restoration of tissue homeostasis.109,110 ICAM-1 has been shown to regulate EC migration by activating Akt and endothelial nitric synthase.101 Besides, EC ICAM-1 has been also shown to mediate recruitment of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) in ischemic hearts to promote angiogenesis following injury.119 Similarly, sICAM-1 has been shown to stimulate EC migration and tube formation.100 Because de novo production or generation of sICAM-1 by cleavage is elevated in inflammation,17,120–122 sICAM-1 may facilitate resolution of inflammation and enhance wound healing by promoting neovascularization.

5 |. ICAM-1 ACTIVITY IMPACTS TUMOR DEVELOPMENT AND METASTASIS

Cellular constituents of tumor microenvironment (TME) include tumor and stromal cells, blood and lymph vessels, as well as infiltrating and resident immune cells.123,124 Expression of ICAM-1 has been documented in most, if not all, cell types in the TME.125,126 As such, in lung adenocarcinoma, ICAM-1 was shown to be induced in transformed alveolar epithelial cells, ECs, pulmonary lymphocytes, and fibroblast.127–129 In melanoma, thin pre-cancerous lesions expressed a negligent amount of ICAM-1; however, analyses of multilayered melanoma lesions revealed heightened ICAM-1 expression at the basal layer.130,131 ICAM-1 expression has been similarly induced in tumor-associated macrophages, and was involved in their polarization.113,132 As with the primary tumor site, ICAM-1 up-regulation was also documented during metastasis.133,134 Studies in experimental liver metastasis model revealed elevated ICAM-1 levels on liver sinusoid ECs, hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and interstitial fibroblasts.125,135 An induction of ICAM-1 expression by tumor resident and infiltrating cells both at the primary and secondary sites indicates an important role of this receptor during tumorigenesis.

5.1 |. ICAM-1 confers aggressive phenotype to cancer cells of the primary tumor niche

ICAM-1 expression has been correlated with aggressive and invasive tumor phenotypes. For example, transcriptional profiling of several triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell lines identified ICAM-1 as one of the top differentially expressed genes compared to other breast cancer cells.136 ICAM-1 was constitutively expressed in basal-like, TNBC cancer cells (most aggressive breast cancer subtype associated with poor prognosis) whereas only inducible in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and luminal B cancer subtypes, and was completely absent in luminal A (less aggressive) subtype of breast cancer. As with breast cancer, ICAM-1 expression is significantly induced in nonsmall cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), which is an aggressive and highly metastatic type of lung cancer, whereas was found to be constitutively expressed at relatively low levels by small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) cells.137,138

Given its putative properties, ICAM-1 expressed by tumor cells can impact tumor development either by promoting tumor-immune cell adhesive interactions or by relaying outside-in signaling to regulate tumor cell function. Supporting the idea of ICAM-1-dependent retention of immune cells, histologic analyses of breast cancer tissue correlated high ICAM-1 expression in TNBC with the presence of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS).139 These T-cell-rich regions are closely associated with invasive and highly immunogenic tumors. Similarly, ICAM-1 expressed by tumor and stromal cells in a melanoma xenograft model was found to promote T-cell aggregation and retention at the tumor niche through binding to β2 -integrin LFA-1.140 Although T-cell recruitment and retention due to ICAM-1 on one hand may improve the immunosurveillance and potentially restrict tumor development, T-cell aggregation within the tumor tissues has been shown to impair the effector function of infiltrating T cells, allowing tumor cells to evade immune recognition and killing.

Interestingly, analyses of tumor sections from patients with TNBC revealed that ICAM-1-expressing tumor cells were localized to tumor invasive front, a region that was also heavily infiltrated by immune cells, particularly T lymphocytes.136,139 Similarly, in squamous cell oral carcinoma ICAM-1 was enriched at the invading basal layer, where accumulating T cells were observed and where immunogenic responses were driven by T-cell-dependent IFN-γ signaling.141 This suggests that tumor infiltrating immune cells via cytokine release may drive expression of ICAM-1 in tumor cells, and as such promote tumor-immune cell interactions and enhance directional cancer cell migration. Indeed, IFN-γ has been shown to induce ICAM-1 expression in cancer cells,142 and in turn, ICAM-1 has been implicated in promoting cancer cell migration.143,144

Although specific ICAM-1 signaling in tumor cells that may enhance migration has not been well defined, evidence from other biologic systems indicates several potential signaling pathways. For example, ICAM-1 through binding interactions with mucin 1 (MUC1), which is overexpressed in breast, ovarian, prostate, and gastric cancers, can activate the pro-migratory MAPK/ERK signaling cascade in neighboring tumor cells.145–148 ICAM-1 can also interact with the ECM components such as fibrinogen to stimulate pro-migratory signaling.149,150 In ECs, engagement of ICAM-1 by immune cells triggered intracellular Ca2+ increases66 and activation of Src kinase63 and Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate (Rac)/Cdc42 GTPases,151–153 all of which can promote cell migration. ICAM-1 may similarly act in transformed epithelial and tumor cells to promote migratory and invasive pheno-types, yet this remains to be determined.

Finally, ICAM-1 up-regulation was also noted in hypoxic tissue,154 where HIF-1 and NFκB signaling axes are substantially activated. Interestingly, in HUVEC cultured under severe hypoxic condition, the induction of ICAM-1 expression was regulated in prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) and NFκB-dependent manner, and was independent of HIF-1 signaling.154 Because oxygen depletion and hypoxia are prominent features of many solid tumors, hypoxic activation of ICAM-1 is likely to govern ICAM-1 signaling and impact tumor viability and transformation.

5.2 |. ICAM-1 roles in the initiation and progression of tumor metastasis

Metastasis is a leading cause for cancer-associated mortality.155 Cancer cells spread to secondary organs by detaching from the primary tumor and subsequently entering the circulation. Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) then traverse to distal sites to form metastatic lesions.156,157 Although the number of CTCs compared to other blood cells is negligent, recent advances in CTC detection methods established CTCs at the forefront of cancer diagnosis, characterization, and therapeutics.158,159 Importantly, the strict correlation between the number of CTCs and increased risk of metastasis and poor patient survival has been demonstrated.160–162

Survival of CTCs in the bloodstream and homing to secondary organs is essential for metastases formation.163–166 Intriguingly, emerging evidence indicates a potential role of ICAM-1 in the regulation of both processes. Analyses of CTCs from breast cancer patients and mouse xenograft models revealed that in circulation, tumor cells tend to attached to each other, forming CTC clusters.164,167,168 Within these clusters, CTCs are protected from the harsh environment in the circulation and display increased proliferative capacity and metastatic potential.167 However, the mechanisms that drive CTC clustering are not yet defined. This raises intriguing questions of whether these clusters formed early upon cancer cells leaving the primary tumors, or assembled later in circulation due to hemodynamic factors. CTC clusters were further found to associate with immune cells, particularly with PMNs, and these associations were surprisingly diminished upon CTC cluster disassembly.167 These exciting observations underscore a potential role of PMNs and likely other circulating immune cells in regulating CTC survival and motility, and as a result, metastatic properties. This of course merits extensive investigation in the future. Because many tumor cell subtypes and immune cells co-express ICAM-1 and various ICAM-1 ligands, including β2-integrins, MUC1, and CD44, it is possible that ICAM-1 plays an important role in the heterotypic clustering of CTCs and PMNs observed in these studies. Based on the above discussion, potential mechanisms by which ICAM-1 may facilitate tumor metastasis are illustrated in Fig. 2.

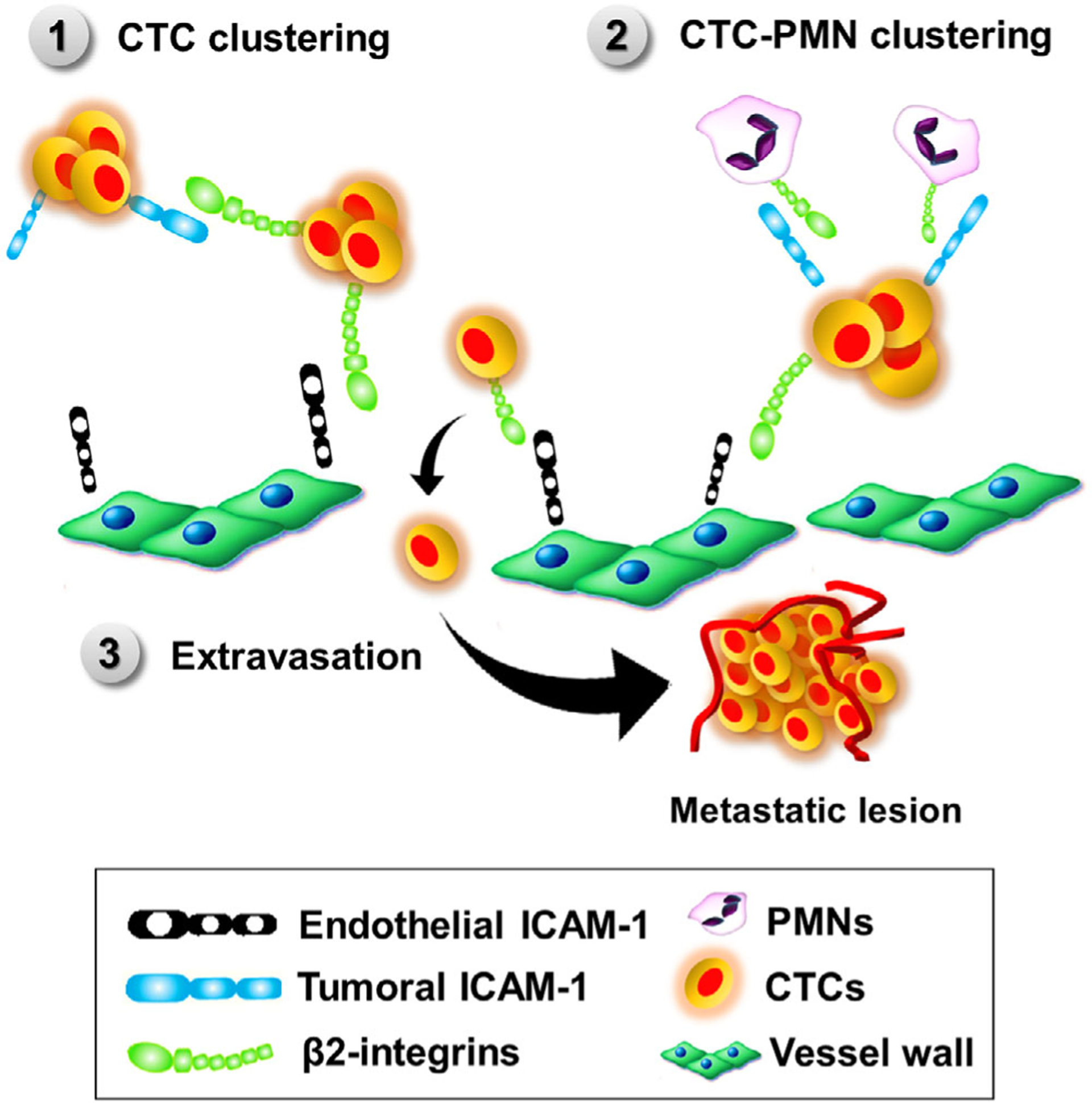

FIGURE 2. Potential mechanisms of action by which ICAM-1 may promote tumor metastasis.

(1) Via binding to β2-integrins expressing tumor cells, ICAM-1 may support homotypic clustering of circulating tumor cells (CTCs). CTC clusters showed increased survival and metastatic potential. (2) Via β2-integrins expressed by immune cells, ICAM-1 can promote CTC-leukocyte clustering β2-integrin. Association of CTC clusters with polymorphonuclear neutrophils increased survival and proliferation of tumor cells. (3) ICAM-1 expressed by endothelial cells can facilitate capture and extravasation of β2-integrin-expressing tumor hijacking transendothelial migration mechanisms used by migrating leukocytes

The process of CTC homing to secondary organs is also a topic of continued investigation. CTCs (likely in the case of CTC clusters) may become trapped in the post-capillary venules in the lung, spleen, or liver,169 and upon intraluminal proliferation can give rise to secondary tumors.170–172 CTCs may also hijack mechanisms governing leukocyte recruitment to extravasate from the circulation into the surrounding tissue. In this process, ICAM-1 expressed by ECs will be a key regulatory player. Indeed, inhibition or KO of EC ICAM-1 or CD18 subunit on melanoma, bladder, and breast cancer cells in vitro, significantly attenuated cancer cell adhesion to ECs and subsequent TEM.131,173 As a result of ICAM-1 inhibition, tumor cell invasion and metastasis was similarly attenuated in vivo in several metastatic cancer models.174–178

In addition to capturing CTCs from the circulation, EC ICAM-1 may promote CTC diapedesis by modulating immune cell behavior. ICAM-1 mediates PMN adhesion to ECs, which leads to PMN degranulation179 and release of various proteinases, including elastase, MMPs, and cathepsins.180,181 Disruption of EC junctions by circulating proteinases may create optimal sites for CTC TEM to occur. Additionally, ligation of EC ICAM-1 by interacting PMNs has been shown to induce MLCK-dependent cytoskeletal rearrangment and increase vascular permeability,80 creating endothelial barrier conditions advantageous for tumor cell TEM. Consistent with this idea, ICAM-1 is constitutively expressed on the sinusoid microvessels of lung and liver,135,182,183 both of which by far represent the most frequent organs of metastasis.

5.3 |. ICAM-1 as a prognostic cancer marker

Although it is clear that ICAM-1 expression is highly induced in the TME, the prognostic value of ICAM-1 on clinical outcomes of cancer patient is still somewhat controversial. Most of the evidence (as discussed earlier) suggests the pro-tumorigenic function of ICAM-1. In many cancers, including oral squamous cell carcinoma, lung carcinoma, gastric, and breast cancers, ICAM-1 has been implicated in promoting cancer,136,141,184–186 whereas in colorectal and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, high levels of tumoral ICAM-1 was predictive of favorable clinical outcomes.187,188

In lung NSCLC (high ICAM-1 levels and highly invasive tumors), high serum level of sICAM-1 strongly correlated with poor response to chemotherapy and decreased patient survival, whereas this correlation was insignificant in SCLC.189–191 In addition, a phase III study for the approval of VEGF-A inhibitor bevacizumab (Avastin), where 878 lung cancer patients were randomized into paclitaxel/carboplatin (standard of care) with or without the addition of bevacizumab, has reported a strict correlation between low levels of sICAM-1 and better response to chemotherapy.192 Specifically, the subgroup with low sICAM-1 had a response rate of 32% to bevacizumab + standard, whereas subgroup with high sICAM-1 had a diminished response rate of 14%. These clinical observations indicate the prognostic value of sICAM-1 in therapeutic response in distinct cancer subtypes.

ICAM-1 levels were also shown to be indicative of tumor grade and as such may have prognostic value in metastatic diseases. A prognostic study comparing 332 patients with benign lung diseases to 387 patients with lung cancer found that patients with advanced tumor stage (stage IV, high metastatic risk) had higher sICAM-1 levels than those with a lower stage.193 Specifically within stage IV subgroup, patients with detectable metastasis had significantly higher sICAM-1 levels compared to those with localized diseases. These observations support ICAM-1 contributions to metastatic progression, as has been observed in pre-clinical studies using animal models.

Finally, there have been efforts to utilize ICAM-1 as a tumor-targeted molecule for therapeutic delivery and diagnostic purpose. As such, ICAM-1 was used to specifically target iron oxide nanoparticles to TNBC, which is currently lacking specific biomarkers and is challenging to diagnose.136 The deposition of these iron particles significantly enhanced signals of magnetic resonance imaging, and helped screening of TNBC in a timely and accurate manner. In another setting, ICAM-1 was engineered as a target moiety to deliver doxorubicin-conjugated liposomes to metastatic melanoma and enhanced drug uptake by these cancer cells.194

6 |. CONCLUDING REMARKS

In summary, ICAM-1 serves as an adhesion molecule and as a signaling receptor in many cells types to mount inflammatory responses, initiate resolution of inflammation and healing, and regulate tumor cell survival and dissemination. These concepts are summarized in Fig. 3. As such, although well studied, ICAM-1 remains the focus of continued investigations and may serve as a promising prognostic biomarker, and a potential target for emerging therapies.

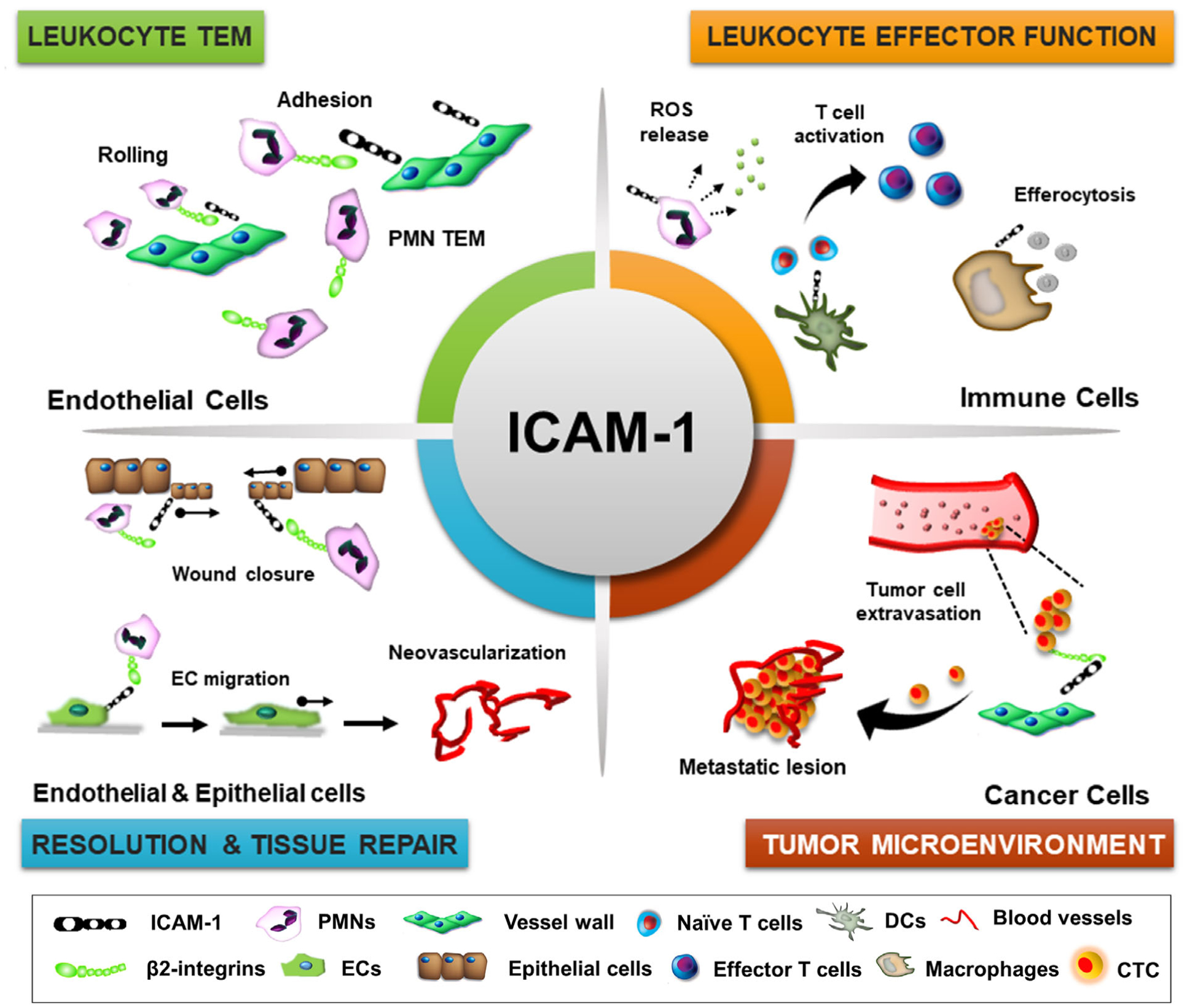

FIGURE 3. ICAM-1 function in tissue homeostasis and disease.

Schematic representation of key physiologic processes regulated by ICAM-1. These include leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions and TEM, regulation of leukocyte effector function in inflammation (ROS release by PMNs, T-cell priming and activation by dendritic cells, macrophage efferocytosis and polarization), tissue repair by promoting neovascularization and reepithelialization, and carcinogenesis by facilitating circulating tumor cell extravasation and survival

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Latin American Association of Immunology (ALAI) and the Mexican Society of Immunology (SMI) for an exciting meeting in Mexico City (2018) and an opportunity to write this review. We also acknowledge support from U.S. National Institutes of Health Grant DK116663, Digestive Health Foundation, American Cancer Society Research Scholar Award, and Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation Senior Research Award.

Abbreviations:

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CTCs

Circulating tumor cells

- DCs

Dendritic cells

- EAE

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- ECs

Endothelial cells

- EPCs

Endothelial progenitor cells

- ERM

Ezrin, radixin, and moesin

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IECs

Intestinal epithelial cells

- LFA-1

Lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1

- Mac-1

Macrophage antigen 1

- MIP-2

Macrophage inflammatory protein 2

- MLCK

Myosin light-chain kinase

- MUC1

Mucin 1

- NSCLC

Nonsmall cell lung carcinoma

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- PMNs

Polymorphonuclear neutrophils

- Rac

Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SCLC

Small cell lung carcinoma

- sICAM-1

soluble ICAM-1

- TEM

Transendothelial migration

- TLS

Tertiary lymphoid structures

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- TNBC

Triple-negative breast cancer

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harjunpaa H, Llort Asens M, Guenther C, Fagerholm SC. Cell adhesion molecules and their roles and regulation in the immune and tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavallaro U, Dejana E. Adhesion molecule signalling: not always a sticky business. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hubbard AK, Rothlein R. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression and cell signaling cascades. Free Radical Biol Med. 2000;28:1379–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wee H, Oh HM, Jo JH, Jun CD. ICAM-1/LFA-1 interaction contributes to the induction of endothelial cell-cell separation: implication for enhanced leukocyte diapedesis. Exp Mol Med. 2009;41: 341–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorina R, Lyck R, Vestweber D, Engelhardt B. beta2 integrin-mediated crawling on endothelial ICAM-1 and ICAM-2 is a prerequisite for transcellular neutrophil diapedesis across the inflamed blood-brain barrier. J Immunol. 2014;192:324–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kong DH, Kim YK, Kim MR, Jang JH, Lee S. Emerging roles of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in immunological disorders and cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wichert S, Juliusson G, Johansson A, et al. A single-arm, open-label, phase 2 clinical trial evaluating disease response following treatment with BI-505, a human anti-intercellular adhesion molecule-1 monoclonal antibody, in patients with smoldering multiple myeloma. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Philpott JR. Antisense inhibition of ICAM-1 expression as therapy provides insight into basic inflammatory pathways through early experiences in IBD. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:1627–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yacyshyn B, Chey WY, Wedel MK, et al. A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled study of alicaforsen, an antisense inhibitor of intercellular adhesion molecule 1, for the treatment of subjects with active Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staunton DE, Marlin SD, Stratowa C, Dustin ML, Springer TA. Primary structure of ICAM-1 demonstrates interaction between members of the immunoglobulin and integrin supergene families. Cell. 1988;52:925–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staunton DE, Dustin ML, Erickson HP, Springer TA. The arrangement of the immunoglobulin-like domains of ICAM-1 and the binding sites for LFA-1 and rhinovirus. Cell. 1990;61:243–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen X, Kim TD, Carman CV, Mi LZ, Song G, Springer TA. Structural plasticity in Ig superfamily domain 4 of ICAM-1 mediates cell surface dimerization. PNAS. 2007;104:15358–15363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller J, Knorr R, Ferrone M, Houdei R, Carron CP, Dustin ML. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 dimerization and its consequences for adhesion mediated by lymphocyte function associated-1. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1231–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frick C, Odermatt A, Zen K, et al. Interaction of ICAM-1 with beta 2-integrin CD11c/CD18: characterization of a peptide ligand that mimics a putative binding site on domain D4 of ICAM-1. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:3610–3621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamond MS, Staunton DE, Marlin SD, Springer TA. Binding of the integrin Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) to the third immunoglobulin-like domain of ICAM-1 (CD54) and its regulation by glycosylation. Cell. 1991;65:961–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King PD, Sandberg ET, Selvakumar A, Fang P, Beaudet AL, Dupont B. Novel isoforms of murine intercellular adhesion molecule-1 generated by alternative RNA splicing. J Immunol. 1995;154:6080–6093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robledo O, Papaioannou A, Ochietti B, et al. ICAM-1 isoforms: specific activity and sensitivity to cleavage by leukocyte elastase and cathepsin G. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1351–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramos TN, Bullard DC, Barnum SR. ICAM-1: isoforms and pheno-types. J Immunol. 2014;192:4469–4474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu H, Gonzalo JA, St Pierre Y, et al. Leukocytosis and resistance to septic shock in intercellular adhesion molecule 1-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:95–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sligh JE Jr, Ballantyne CM, Rich SS, et al. Inflammatory and immune responses are impaired in mice deficient in intercellular adhesion molecule 1. PNAS. 1993;90:8529–8533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bullard DC, Hu X, Crawford D, McDonald K, Ramos TN, Barnum SR. Expression of a single ICAM-1 isoform on T cells is sufficient for development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:1194–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu X, Barnum SR, Wohler JE, Schoeb TR, Bullard DC. Differential ICAM-1 isoform expression regulates the development and progression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Mol Immunol. 2010;47:1692–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samoilova EB, Horton JL, Chen Y. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in intercellular adhesion molecule-1-deficient mice. Cell Immunol. 1998;190:83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott DW, Patel RP. Endothelial heterogeneity and adhesion molecules N-glycosylation: implications in leukocyte trafficking in inflammation. Glycobiology. 2013;23:622–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott DW, Vallejo MO, Patel RP. Heterogenic endothelial responses to inflammation: role for differential N-glycosylation and vascular bed of origin. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He P, Srikrishna G, Freeze HH. N-glycosylation deficiency reduces ICAM-1 induction and impairs inflammatory response. Glycobiology. 2014;24:392–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott DW, Dunn TS, Ballestas ME, Litovsky SH, Patel RP. Identification of a high-mannose ICAM-1 glycoform: effects of ICAM-1 hypoglycosylation on monocyte adhesion and outside in signaling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;305:C228–C237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott DW, Tolbert CE, Graham DM, Wittchen E, Bear JE, Bur-ridge K. N-glycosylation controls the function of junctional adhesion molecule-A. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:3205–3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roebuck KA, Finnegan A. Regulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (CD54) gene expression. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:876–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakurada S, Kato T, Okamoto T. Induction of cytokines and ICAM-1 by proinflammatory cytokines in primary rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts and inhibition by N-acetyl-L-cysteine and aspirin. Int Immunol. 1996;8:1483–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sumagin R, Robin AZ, Nusrat A, Parkos CA. Transmigrated neutrophils in the intestinal lumen engage ICAM-1 to regulate the epithelial barrier and neutrophil recruitment. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:905–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiesolek HL, Bui TM, Lee JJ, et al. ICAM-1 functions as an efferocytosis receptor in inflammatory macrophages. Am J Pathol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu RR, Li J, Gong JY, et al. MicroRNA-141 regulates the expression level of ICAM-1 on endothelium to decrease myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309: H1303–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oppenheimer-Marks N, Davis LS, Bogue DT, et al. Differential utilization of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 during the adhesion and transendothelial migration of human T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1991;147: 2913–2921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanters E, van Rijssel J, Hensbergen PJ, et al. Filamin B mediates ICAM-1-driven leukocyte transendothelial migration. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31830–31839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lyck R, Enzmann G. The physiological roles of ICAM-1 and ICAM-2 in neutrophil migration into tissues. Curr Opin Hematol. 2015;22:53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lawson C, Wolf S. ICAM-1 signaling in endothelial cells. Pharmacol Rep: PR 61. 2009:22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahman A, Fazal F. Hug tightly and say goodbye: role of endothelial ICAM-1 in leukocyte transmigration. Antioxid Redox Signaling. 2009;11:823–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li N, Yang H, Wang M, Lu S, Zhang Y, Long M. Ligand-specific binding forces of LFA-1 and Mac-1 in neutrophil adhesion and crawling. Mol Biol Cell. 2018;29:408–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sumagin R, Sarelius IH. A role for ICAM-1 in maintenance of leukocyte-endothelial cell rolling interactions in inflamed arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2786–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sumagin R, Prizant H, Lomakina E, Waugh RE, Sarelius IH. LFA-1 and Mac-1 define characteristically different intralumenal crawling and emigration patterns for monocytes and neutrophils in situ. J Immunol. 2010;185:7057–7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sumagin R, Lamkin-Kennard KA, Sarelius IH. A separate role for ICAM-1 and fluid shear in regulating leukocyte interactions with straight regions of venular wall and venular convergences. Microcirculation. 2009;16:508–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sumagin R, Sarelius IH. TNF-alpha activation of arterioles and venules alters distribution and levels of ICAM-1 and affects leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2116–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sumagin R, Lomakina E, Sarelius IH. Leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions are linked to vascular permeability via ICAM-1-mediated signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H969–H977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sumagin R, Sarelius IH. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 enrichment near tricellular endothelial junctions is preferentially associated with leukocyte transmigration and signals for reorganization of these junctions to accommodate leukocyte passage. J Immunol. 2010;184:5242–5252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bromley SK, Dustin ML. Stimulation of naive T-cell adhesion and immunological synapse formation by chemokine-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Immunology. 2002;106:289–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldstein JS, Chen T, Gubina E, Pastor RW, Kozlowski S. ICAM-1 enhances MHC-peptide activation of CD8(+) T cells without an organized immunological synapse. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:3266–3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Real E, Kaiser A, Raposo G, et al. Immature dendritic cells (DCs) use chemokines and intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, but not DC-specific ICAM-3-grabbing nonintegrin, to stimulate CD4+ T cells in the absence of exogenous antigen. J Immunol. 2004;173:50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kohlmeier JE, Rumsey LM, Chan MA, Benedict SH. The outcome of T-cell costimulation through intercellular adhesion molecule-1 differs from costimulation through leucocyte function-associated antigen-1. Immunology. 2003;108:152–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chirathaworn C, Kohlmeier JE, Tibbetts SA, Rumsey LM, Chan MA, Benedict SH. Stimulation through intercellular adhesion molecule-1 provides a second signal for T cell activation. J Immunol. 2002;168:5530–5537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cox MA, Barnum SR, Bullard DC, Zajac AJ. ICAM-1-dependent tuning of memory CD8 T-cell responses following acute infection. PNAS. 2013;110:1416–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elsner J, Sach M, Knopf HP, et al. Synthesis and surface expression of ICAM-1 in polymorphonuclear neutrophilic leukocytes in normal subjects and during inflammatory disease. Immunobiology. 1995;193:456–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woodfin A, Beyrau M, Voisin MB, et al. ICAM-1-expressing neutrophils exhibit enhanced effector functions in murine models of endotoxemia. Blood. 2016;127:898–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang SZ, Smith PK, Lovejoy M, Bowden JJ, Alpers JH, Forsyth KD. Shedding of L-selectin and PECAM-1 and upregulation of Mac-1 and ICAM-1 on neutrophils in RSV bronchiolitis. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L983–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lefort CT, Hyun YM, Schultz JB, et al. Outside-in signal transmission by conformational changes in integrin Mac-1. J Immunol. 2009;183:6460–6468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barreiro O, Yanez-Mo M, Serrador JM, et al. Dynamic interaction of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 with moesin and ezrin in a novel endothelial docking structure for adherent leukocytes. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:1233–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carpen O, Pallai P, Staunton DE, Springer TA. Association of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) with actin-containing cytoskeleton and alpha-actinin. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:1223–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Couty JP, Rampon C, Leveque M, et al. PECAM-1 engagement counteracts ICAM-1-induced signaling in brain vascular endothelial cells. J Neurochem. 2007;103:793–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Federici C, Camoin L, Hattab M, Strosberg AD, Couraud PO. Association of the cytoplasmic domain of intercellular-adhesion molecule-1 with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and beta-tubulin. FEBS. 1996;238:173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang L, Kowalski JR, Yacono P, et al. Endothelial cell cortactin coordinates intercellular adhesion molecule-1 clustering and actin cytoskeleton remodeling during polymorphonuclear leukocyte adhesion and transmigration. J Immunol. 2006;177:6440–6449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Etienne S, Adamson P, Greenwood J, Strosberg AD, Cazaubon S, Couraud PO. ICAM-1 signaling pathways associated with Rho activation in microvascular brain endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:5755–5761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gardiner EE, D’Souza SE. Sequences within fibrinogen and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) modulate signals required for mitogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11930–11936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu G, Place AT, Chen Z, et al. ICAM-1-activated Src and eNOS signaling increase endothelial cell surface PECAM-1 adhesivity and neutrophil transmigration. Blood. 2012;120:1942–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dragoni S, Hudson N, Kenny BA, et al. Endothelial MAPKs direct ICAM-1 signaling to divergent inflammatory functions. J Immunol. 2017;198:4074–4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rahman A, Anwar KN, Uddin S, et al. Protein kinase C-delta regulates thrombin-induced ICAM-1 gene expression in endothelial cells via activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5554–5565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Etienne-Manneville S, Manneville JB, Adamson P, Wilbourn B, Greenwood J, Couraud PO. ICAM-1-coupled cytoskeletal rearrangements and transendothelial lymphocyte migration involve intracellular calcium signaling in brain endothelial cell lines. J Immunol. 2000;165:3375–3383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Renkonen R, Mennander A, Ustinov J, Mattila P. Activation of protein kinase C is crucial in the regulation of ICAM-1 expression on endothelial cells by interferon-gamma. Int Immunol. 1990;2:719–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bonan S, Albrengues J, Grasset E, et al. Membrane-bound ICAM-1 contributes to the onset of proinvasive tumor stroma by controlling acto-myosin contractility in carcinoma-associated fibroblasts. Onco-target. 2017;8:1304–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Frank PG, Lisanti MP. ICAM-1: role in inflammation and in the regulation of vascular permeability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H926–H927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sarelius IH, Glading AJ. Control of vascular permeability by adhesion molecules. Tissue Barriers. 2015;3:e985954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lawson C, Ainsworth M, Yacoub M, Rose M. Ligation of ICAM-1 on endothelial cells leads to expression of VCAM-1 via a nuclear factor-kappaB-independent mechanism. J Immunol. 1999;162:2990–2996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lomakina EB, Waugh RE. Signaling and dynamics of activation of LFA-1 and Mac-1 by immobilized IL-8. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2010;3:106–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Talavera D, Castillo AM, Dominguez MC, Gutierrez AE, Meza I. IL8 release, tight junction and cytoskeleton dynamic reorganization conducive to permeability increase are induced by dengue virus infection of microvascular endothelial monolayers. J Gen Virol. 2004;85: 1801–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Terao S, Yilmaz G, Stokes KY, et al. Blood cell-derived RANTES mediates cerebral microvascular dysfunction, inflammation, and tissue injury after focal ischemia-reperfusion. Stroke. 2008;39: 2560–2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu H, Huang X, Ma Y, et al. Interleukin-8 regulates endothelial permeability by down-regulation of tight junction but not dependent on integrins induced focal adhesions. Int J Biol Sci. 2013;9:966–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tosi MF, Stark JM, Smith CW, Hamedani A, Gruenert DC, Infeld MD. Induction of ICAM-1 expression on human airway epithelial cells by inflammatory cytokines: effects on neutrophil-epithelial cell adhesion. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;7:214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dippold W, Wittig B, Schwaeble W, Mayet W, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH. Expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1, CD54) in colonic epithelial cells. Gut. 1993;34:1593–1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chan SC, Shum DK, Tipoe GL, Mak JC, Leung ET, Ip MS. Upregulation of ICAM-1 expression in bronchial epithelial cells by airway secretions in bronchiectasis. Respir Med. 2008;102:287–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jones SC, Banks RE, Haidar A, et al. Adhesion molecules in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1995;36:724–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Choi H, Fleming NW, Serikov VB. Contact activation via ICAM-1 induces changes in airway epithelial permeability in vitro. Immunol Invest. 2007;36:59–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yonemura S, Hirao M, Doi Y, et al. Ezrin/radixin/moesin (ERM) proteins bind to a positively charged amino acid cluster in the juxta-membrane cytoplasmic domain of CD44, CD43, and ICAM-2. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:885–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tsukita S, Oishi K, Sato N, Sagara J, Kawai A, Tsukita S. ERM family members as molecular linkers between the cell surface glycoprotein CD44 and actin-based cytoskeletons. J Cell Biol. 1994;126: 391–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kirschner N, Haftek M, Niessen CM, et al. CD44 regulates tight-junction assembly and barrier function. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:932–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Capra F, De Maria E, Lunardi C, et al. Serum level of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1 in patients with chronic liver disease related to hepatitis C virus: a prognostic marker for responses to interferon treatment. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Magro F, Araujo F, Pereira P, Meireles E, Diniz-Ribeiro M, Velosom FT. Soluble selectins, sICAM, sVCAM, and angiogenic proteins in different activity groups of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1265–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nielsen OH, Brynskov J, Vainer B. Increased mucosal concentrations of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1), sE-selectin, and interleukin-8 in active ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:1780–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.de Pablo R, Monserrat J, Reyes E, et al. Circulating sICAM-1 and sE-Selectin as biomarker of infection and prognosis in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Eur J Intern Med. 2013;24:132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wakatsuki T, Kimura K, Kimura F, et al. A distinct mRNA encoding a soluble form of ICAM-1 molecule expressed in human tissues. Cell Adhes Commun. 1995;3:283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang HW, Babic AM, Mitchell HA, Liu K, Wagner DD. Elevated soluble ICAM-1 levels induce immune deficiency and increase adiposity in mice. FASEB J. 2005;19:1018–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Roescher N, Vosters JL, Yin H, Illei GG, Tak PP, Chiorini JA. Effect of soluble ICAM-1 on a Sjogren’s syndrome-like phenotype in NOD mice is disease stage dependent. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Laudes IJ, Guo RF, Riedemann NC, et al. Disturbed homeostasis of lung intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 during sepsis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1435–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lopez-Campos JL, Calero C, Arellano-Orden E, et al. Increased levels of soluble ICAM-1 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and resistant smokers are related to active smoking. Biomark Med. 2012;6:805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shiota Y, Sato T, Ono T. [Serum levels of soluble ICAM-1 in asthmatic patients]. Arerugi. 1993;42:1782–1787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zonneveld R, Martinelli R, Shapiro NI, et al. Soluble adhesion molecules as markers for sepsis and the potential pathophysio-logical discrepancy in neonates, children and adults. Critical Care. 2014;18:204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gross MD, Bielinski SJ, Suarez-Lopez JR, et al. Circulating soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and subclinical atherosclerosis: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Clin Chem. 2012;58:411–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Luc G, Arveiler D, Evans A, et al. Circulating soluble adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 and incident coronary heart disease: the PRIME Study. Atherosclerosis. 2003;170:169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kostler WJ, Tomek S, Brodowicz T, et al. Soluble ICAM-1 in breast cancer: clinical significance and biological implications. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2001;50:483–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gu X, Ma C, Yuan D, Song Y. Circulating soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in lung cancer: a systematic review. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2012;1:36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Giannoulis K, Angouridaki C, Fountzilas G, Papapolychroniadis C, Giannoulis E, Gamvros O. Serum concentrations of soluble ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in patients with colorectal cancer. Clinical implications. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8(Suppl 1):s65–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gho YS, Kleinman HK, Sosne G. Angiogenic activity of human soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5128–5132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kevil CG, Orr AW, Langston W, et al. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) regulates endothelial cell motility through a nitric oxide-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19230–19238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rieckmann P, Michel U, Albrecht M, Bruck W, Wockel L, Felgenhauer K. Soluble forms of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) block lymphocyte attachment to cerebral endothelial cells. J Neuroimmunol. 1995;60:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kim JY, Kim DH, Kim JH, et al. Soluble intracellular adhesion molecule-1 secreted by human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cell reduces amyloid-beta plaques. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:680–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Eming SA, Martin P, Tomic-Canic M. Wound repair and regeneration: mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:265sr6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gonzalez AC, Costa TF, Andrade ZA, Medrado AR. Wound healing - A literature review. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:614–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Koh TJ, DiPietro LA. Inflammation and wound healing: the role of the macrophage. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mantovani A, Biswas SK, Galdiero MR, Sica A, Locati M. Macrophage plasticity and polarization in tissue repair and remodelling. J Pathol. 2013;229:176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tang PM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY. Macrophages: versatile players in renal inflammation and fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15: 144–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wynn TA, Vannella KM. Macrophages in tissue repair, regeneration, and fibrosis. Immunity. 2016;44:450–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Elliott MR, Koster KM, Murphy PS. Efferocytosis signaling in the regulation of macrophage inflammatory responses. J Immunol. 2017;198:1387–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Korns D, Frasch SC, Fernandez-Boyanapalli R, Henson PM, Bratton DL. Modulation of macrophage efferocytosis in inflammation. Front Immunol. 2011;2:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gu W, Yao L, Li L, et al. ICAM-1 regulates macrophage polarization by suppressing MCP-1 expression via miR-124 upregulation. Onco-target. 2017;8:111882–111901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Proto JD, Doran AC, Gusarova G, et al. Regulatory T cells promote macrophage efferocytosis during inflammation resolution. Immunity. 2018;49:666–677 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sumagin R, Brazil JC, Nava P, et al. Neutrophil interactions with epithelial-expressed ICAM-1 enhances intestinal mucosal wound healing. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:1151–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nagaoka T, Kaburagi Y, Hamaguchi Y, et al. Delayed wound healing in the absence of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 or L-selectin expression. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gay AN, Mushin OP, Lazar DA, et al. Wound healing characteristics of ICAM-1 null mice devoid of all isoforms of ICAM-1. J Surg Res. 2011;171:e1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Jameson J, Ugarte K, Chen N, et al. A role for skin gammadelta T cells in wound repair. Science. 2002;296:747–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wu Y, Ip JE, Huang J, et al. Essential role of ICAM-1/CD18 in mediating EPC recruitment, angiogenesis, and repair to the infarcted myocardium. Circ Res. 2006;99:315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Melotti P, Nicolis E, Tamanini A, Rolfini R, Pavirani A, Cabrini G. Activation of NF-kB mediates ICAM-1 induction in respiratory cells exposed to an adenovirus-derived vector. Gene Ther. 2001;8: 1436–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tong S, Neboori HJ, Tran ED, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Constitutive expression and enzymatic cleavage of ICAM-1 in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. J Vasc Res. 2011;48:386–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Champagne B, Tremblay P, Cantin A, St Pierre Y. Proteolytic cleavage of ICAM-1 by human neutrophil elastase. J Immunol. 1998;161: 6398–6405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ansell SM, Vonderheide RH. Cellular composition of the tumor microenvironment. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Balkwill FR, Capasso M, Hagemann T. The tumor microenvironment at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:5591–5596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Benedicto A, Romayor I, Arteta B. Role of liver ICAM-1 in metastasis. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:3883–3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Reina M, Espel E. Role of LFA-1 and ICAM-1 in cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2017;9(11):153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Jiang Z, Woda BA, Savas L, Fraire AE. Expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and LFA-1 in adenocarcinoma of the lung with observations on the expression of these adhesion molecules in non-neoplastic lung tissue. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:1189–1192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Passlick B, Izbicki JR, Simmel S, et al. Expression of major histocompatibility class I and class II antigens and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 on operable non-small cell lung carcinomas: frequency and prognostic significance. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A: 376–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Passlick B, Pantel K, Kubuschok B, et al. Expression of MHC molecules and ICAM-1 on non-small cell lung carcinomas: association with early lymphatic spread of tumour cells. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Natali P, Nicotra MR, Cavaliere R, et al. Differential expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 in primary and metastatic melanoma lesions. Cancer Res. 1990;50:1271–1278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zhang P, Goodrich C, Fu C, Dong C. Melanoma upregulates ICAM-1 expression on endothelial cells through engagement of tumor CD44 with endothelial E-selectin and activation of a PKCalpha-p38-SP-1 pathway. FASEB J. 2014;28:4591–4609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Yang M, Liu J, Piao C, Shao J, Du J. ICAM-1 suppresses tumor metastasis by inhibiting macrophage M2 polarization through blockade of efferocytosis. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Rosette C, Roth RB, Oeth P, et al. Role of ICAM1 in invasion of human breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:943–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sokeland G, Schumacher U. The functional role of integrins during intra- and extravasation within the metastatic cascade. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Benedicto A, Herrero A, Romayor I, et al. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cell ICAM-1 mediated tumor/endothelial crosstalk drives the development of liver metastasis by initiating inflammatory and angiogenic responses. Sci Rep. 2019;9:13111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Guo P, Huang J, Wang L, et al. ICAM-1 as a molecular target for triple negative breast cancer. PNAS. 2014;111:14710–14715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Melis M, Spatafora M, Melodia A, et al. ICAM-1 expression by lung cancer cell lines: effects of upregulation by cytokines on the interaction with LAK cells. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:1831–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Schardt C, Heymanns J, Schardt C, Rotsch M, Havemann K. Differential expression of the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in lung cancer cell lines of various histological types. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A:2250–2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Figenschau SL, Knutsen E, Urbarova I, et al. ICAM1 expression is induced by proinflammatory cytokines and associated with TLS formation in aggressive breast cancer subtypes. Sci Rep. 2018; 8:11720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Yanguas A, Garasa S, Teijeira A, Auba C, Melero I, Rouzaut A. ICAM-1-LFA-1 dependent CD8+ T-lymphocyte aggregation in tumor tissue prevents recirculation to draining lymph nodes. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Usami Y, Ishida K, Sato S, et al. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression correlates with oral cancer progression and induces macrophage/cancer cell adhesion. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:568–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Chang YJ, Holtzman MJ, Chen CC. Interferon-gamma-induced epithelial ICAM-1 expression and monocyte adhesion. Involvement of protein kinase C-dependent c-Src tyrosine kinase activation pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7118–7126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Lin YC, Shun CT, Wu MS, Chen CC. A novel anticancer effect of thalidomide: inhibition of intercellular adhesion molecule-1-mediated cell invasion and metastasis through suppression of nuclear factor-kappaB. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:7165–7173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kesanakurti D, Chetty C, Rajasekhar Maddirela D, Gujrati M, Rao JS. Essential role of cooperative NF-kappaB and Stat3 recruitment to ICAM-1 intronic consensus elements in the regulation of radiation-induced invasion and migration in glioma. Oncogene. 2013;32: 5144–5155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Hayashi T, Takahashi T, Motoya S, et al. MUC1 mucin core protein binds to the domain 1 of ICAM-1. Digestion. 2001;63(Suppl 1):87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Hattrup CL, Gendler SJ. MUC1 alters oncogenic events and transcription in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:R37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Yuan Z, Wong S, Borrelli A, Chung MA. Down-regulation of MUC1 in cancer cells inhibits cell migration by promoting E-cadherin/catenin complex formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362: 740–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Ihermann-Hella A, Lume M, Miinalainen IJ, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway regulates branching by remodeling epithelial cell adhesion. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Roche Y, Pasquier D, Rambeaud JJ, Seigneurin D, Duperray A. Fibrinogen mediates bladder cancer cell migration in an ICAM-1-dependent pathway. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89:1089–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Tsakadze NL, Zhao Z, D’Souza SE. Interactions of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 with fibrinogen. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2002; 12:101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Nurmi SM, Autero M, Raunio AK, Gahmberg CG, Fagerholm SC. Phosphorylation of the LFA-1 integrin beta2-chain on Thr-758 leads to adhesion, Rac-1/Cdc42 activation, and stimulation of CD69 expression in human T cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:968–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Li CH, Liao PL, Shyu MK, et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles-induced intercellular adhesion molecule 1 expression requires Rac1/Cdc42, mixed lineage kinase 3, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation in endothelial cells. Toxicol Sci. 2012;126:162–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Kim H, Hwang JS, Woo CH, et al. TNF-alpha-induced up-regulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 is regulated by a Rac-ROS-dependent cascade in human airway epithelial cells. Exp Mol Med. 2008;40:167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Winning S, Splettstoesser F, Fandrey J, Frede S. Acute hypoxia induces HIF-independent monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells through increased intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression: the role of hypoxic inhibition of prolyl hydroxylase activity for the induction of NF-kappa B. J Immunol. 2010;185:1786–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Guan X Cancer metastases: challenges and opportunities. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5:402–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Seyfried TN, Huysentruyt LC. On the origin of cancer metastasis. Crit Rev Oncog. 2013;18:43–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Pantel K, Brakenhoff RH. Dissecting the metastatic cascade. Nature Rev Cancer. 2004;4:448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Keller L, Pantel K. Unravelling tumour heterogeneity by single-cell profiling of circulating tumour cells. Nature Rev Cancer. 2019;19: 553–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Tellez-Gabriel M, Brown HK, Young R, Heymann MF, Heymann D. The challenges of detecting circulating tumor cells in sarcoma. Front Oncol. 2016;6:202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Micalizzi DS, Maheswaran S, Haber DA. A conduit to metastasis: circulating tumor cell biology. Genes Dev. 2017;31:1827–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Shishido SN, Carlsson A, Nieva J, et al. Circulating tumor cells as a response monitor in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. J Transl Med. 2019;17:294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Wang X, Ma K, Yang Z, et al. Systematic correlation analyses of circulating tumor cells with clinical variables and tumor markers in lung cancer patients. J Cancer. 2017;8:3099–3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Kim YR, Yoo JK, Jeong CW, Choi JW. Selective killing of circulating tumor cells prevents metastasis and extends survival. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Gkountela S, Castro-Giner F, Szczerba BM, et al. Circulating tumor cell clustering shapes DNA methylation to enable metastasis seeding. Cell. 2019;176:98–112 e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Wang WC, Zhang XF, Peng J, et al. Survival mechanisms and influence factors of circulating tumor cells. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:6304701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Strilic B, Offermanns S. Intravascular survival and extravasation of tumor cells. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:282–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Szczerba BM, Castro-Giner F, Vetter M, et al. Neutrophils escort circulating tumour cells to enable cell cycle progression. Nature. 2019;566:553–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Saini M, Szczerba BM, Aceto N. Circulating tumor cell-neutrophil tango along the metastatic process. Cancer Res. 2019;79:6067–6073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Labelle M, Hynes RO. The initial hours of metastasis: the importance of cooperative host-tumor cell interactions during hematogenous dissemination. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:1091–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Mekata E, Shimizu T, Endo Y, Tani T. The rapid growth of intraluminal tumor metastases at the intestinal wall sites damaged by obstructive colitis due to sigmoid colon cancer: report of a case. Surg Today. 2008;38:862–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Bhatti N, Gilson RJ, Beecham M, et al. Failure to deliver hepatitis B vaccine: confessions from a genitourinary medicine clinic. BMJ. 1991;303:97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Takayoshi K, Ariyama H, Tamura S, et al. Intraluminal superior vena cava metastasis from adenosquamous carcinoma of the duodenum: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:605–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Ghislin S, Obino D, Middendorp S, Boggetto N, Alcaide-Loridan C, Deshayes F. LFA-1 and ICAM-1 expression induced during melanoma-endothelial cell co-culture favors the transendothelial migration of melanoma cell lines in vitro. BMC Cancer. 2012; 12:455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]