Lysosomes have fundamental physiological roles and have previously been implicated in Parkinson’s disease1–5. However, how extracellular growth factors communicate with intracellular organelles to control lysosomal function is not well understood. Here we report a lysosomal K+ channel complex that is activated by growth factors and gated by protein kinase B (AKT) that we term lysoKGF. LysoKGF consists of a pore-forming protein TMEM175 and AKT: TMEM175 is opened by conformational changes in, but not the catalytic activity of, AKT. The minor allele at rs34311866, a common variant in TMEM175, is associated with an increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease and reduces channel currents. Reduction in lysoKGF function predisposes neurons to stress-induced damage and accelerates the accumulation of pathological α-synuclein. By contrast, the minor allele at rs3488217—another common variant of TMEM175, which is associated with a decreased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease—produces a gain-of-function in lysoKGF during cell starvation, and enables neuronal resistance to damage. Deficiency in TMEM175 leads to a loss of dopaminergic neurons and impairment in motor function in mice, and a TMEM175 loss-of-function variant is nominally associated with accelerated rates of cognitive and motor decline in humans with Parkinson’s disease. Together, our studies uncover a pathway by which extracellular growth factors regulate intracellular organelle function, and establish a targetable mechanism by which common variants of TMEM175 confer risk for Parkinson’s disease.

Several hundred plasma-membrane ion channels are gated by cellular factors, such as voltage and lipids6,7. Protein kinases regulate channels by phosphorylation. Whether they also gate channels independent of catalysis has not been established. Recent studies have revealed several endolysosomal channels8,9. Extracellular amino acids inhibit the Na+- and Ca2+-permeable channels10, but whether growth factors also communicate with the intracellular channels remains to be determined.

Growth factors activate a lysosomal K+ channel

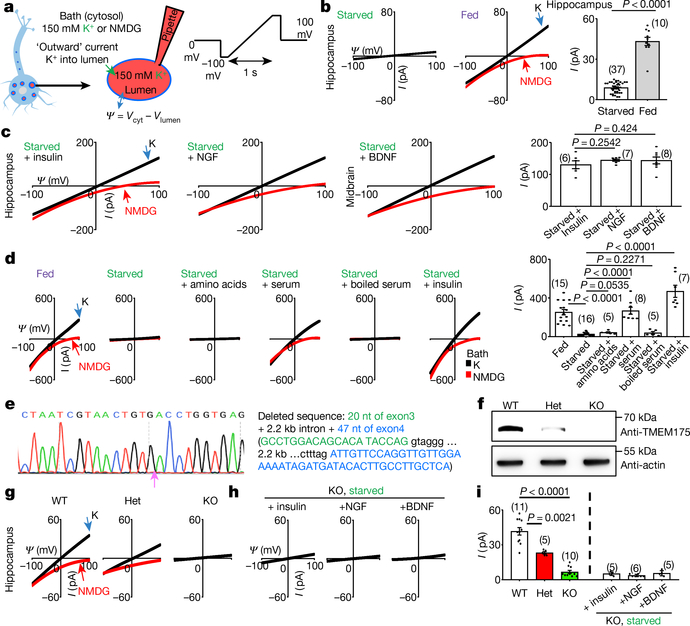

In lysosomes dissected from neurons starved in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), there was little K+ current (IK). Notably, adding a B27 supplement to the medium activated a large IK. As a control, removing B27 did not reduce Na+ current (Fig. 1a, b, Extended Data Fig. 1a, b). A major component in B27 is insulin11. The application of insulin, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) or nerve growth factor (NGF) to starved neurons reactivated IK (Fig. 1c); thus, neuronal lysosomes have a growth-factor-activated K+ channel (that is, lysoKGF).

Fig. 1 |. A growth-factor-activated lysosomal K+ channel, lysoKGF.

a, Schematic of the recording of neuronal lysosomes. b, Currents (I) recorded at varying voltages (Ψ) from mouse hippocampal neurons with (starved) or without (fed) overnight starvation in DMEM containing no B27 nutrient. c, Currents from neurons with starvation followed by refeeding (in DMEM medium) with insulin (100 nM for 4 h), NGF (100 ng ml−1, 3 h) or BDNF (10 ng ml−1, 3 h). d, Reconstituting lysoKGF by TMEM175 transfection in HEK293T cells. Currents were recorded before, 2 h after starvation or after a 2-h starvation followed by refeeding with amino acids (10× for 10 min), with serum (10%, 4 h), with serum inactivated by boiling for 10 min or with insulin (100 nM, 4 h). e–i, Comparison between lysoKGF from wild-type and TMEM175-knockout neurons. e, Sequencing of the knock out, showing deletion of parts of exons 3 and 4. f, Total brain proteins (100 μg) from wild type (WT), heterozygous (het) and homozygous TMEM175-knockout (KO) mice were immunoblotted with anti-TMEM175 and—as a loading control—reblotted with anti-actin. For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1. g, Currents from B27-replete hippocampal neurons. h, Currents from B27-starved (overnight in DMEM) knockout neurons refed with insulin (hippocampal neurons), NGF (hippocampal) or BDNF (midbrain). Black (K) and red (N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG)) traces are currents recorded with bath solutions containing K+ or NMDG, respectively. Averaged IK sizes (at 100 mV, with K+-containing bath) are in bar graphs (b–d, i). Data are mean ± s.e.m. Numbers of recordings are in parentheses. P values shown are from unpaired two-tailed t-tests.

TMEM175 forms the lysoKGF pore

The linear current–voltage relationship of lysoKGF is similar to that of the K+ channel formed by the pore-forming protein TMEM175 (which is localized to the lysosome)12,13, but distinct from that of the large-conductance Ca2+-activated BK potassium channels14. Nontransfected HEK293T cell lysosomes had little IK (28.0 ± 4.7 pA, at 100 mV, n = 20). Transfecting human TMEM175 generated large K+ currents (ITMEM175) under serum-replete conditions. ITMEM175 was abolished by starvation, and was reactivated by refeeding with insulin or serum containing growth factors but not with amino acids or boiled serum (Fig. 1d).

In homozygous Tmem175-knockout mice (Fig. 1e, f), lysosomes in neurons from B27-replete medium and starved neurons refed with growth factors lacked substantial IK (about 5 pA, which is close to the detection limit); this suggests that TMEM175 is the only major K+ channel under our conditions. In neurons from heterozygote mice, IK was reduced by around 50%, which suggests strict gene dosage dependency (Fig. 1g–i, Extended Data Fig. 1d).

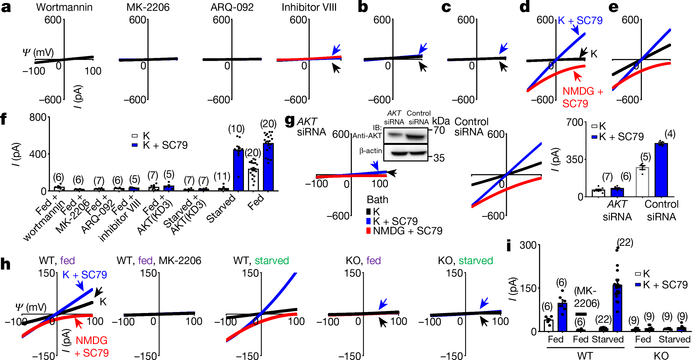

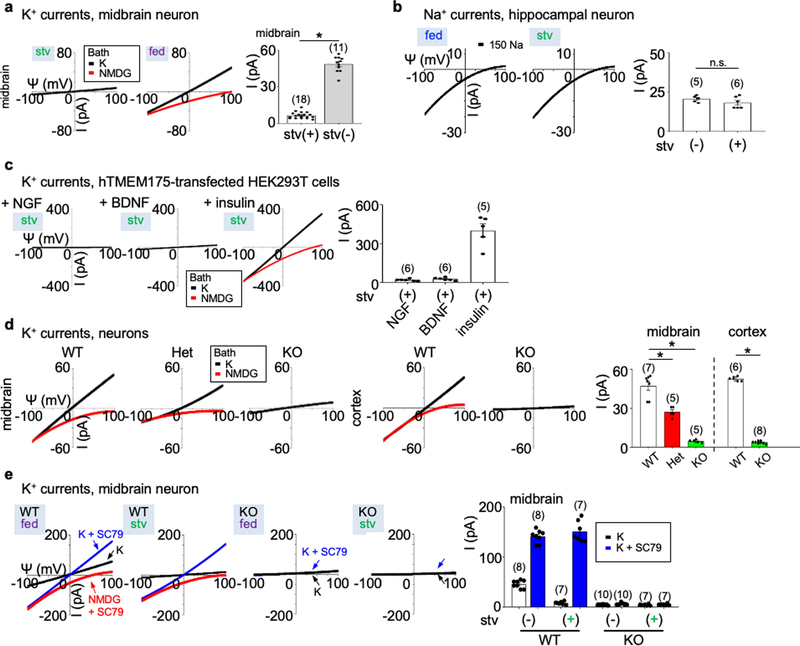

AKT is necessary for lysoKGF

In HEK293T cells (which, unlike neurons, do not express NGF or BDNF receptors15–17), only insulin activated TMEM175 (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Fig. 1c), which suggests that growth factors activate TMEM175 indirectly through receptors. A major target of growth factor receptors is the ubiquitously expressed AKT18. Incubating cells transfected with human TMEM175 with nonspecific (wortmannin) or specific allosteric AKT inhibitors, cotransfecting a dominant-negative AKT or knocking down AKT all markedly reduced ITMEM175 (Fig. 2a, b, f, g), which suggests that AKT is necessary to activate TMEM175.

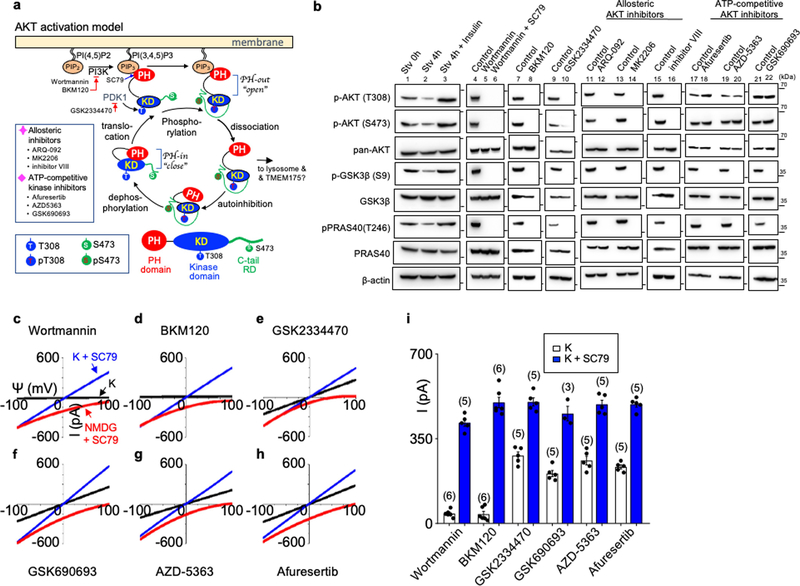

Fig. 2 |. AKT is necessary and sufficient to activate TMEM175.

a–f, Currents from TMEM175-transfected HEK293T cells. In b, c, a dominant-negative AKT (triple-mutant AKT(K179M/T308A/S473A); AKT(KD3)) was cotransfected. In a, cells were pretreated with wortmannin (20 μM, 2 h), an allosteric AKT inhibitor (MK-2206 (20 μM, 3 h) or ARQ-092 (20 μM, 3 h)) or AKT inhibitor VIII (10 μM, 3 h) before lysosomal dissection for recording. In a, b, e, cells were not starved; in c, d, cells were starved in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) medium for 2 h. g, Currents from TMEM175-transfected cells without starvation pretreated with small interfering (si)RNAs against AKT1, AKT2 and AKT3 or with a control siRNA. Inset, western blot showing the efficient knockdown of AKT. For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1. IB, immunoblot. h, i, Currents from wild-type and TMEM175-knockout mouse hippocampal neurons before or after starvation (overnight in DMEM). The AKT activator SC79 (10 μM) was applied to the bath during some of the recordings (blue and red traces). Bar graphs in f, g, i show averaged current sizes (at 100 mV). Data are mean ± s.e.m. Numbers of recordings are in parentheses. Arrows are used to indicate curves that overlap and are not easily distinguished. Colours denote conditions for recording: from a bath containing K+ (black), K+ and SC79 (blue) or NMDG and SC79 (red).

To test whether AKT is also sufficient for TMEM175 activation, we applied the AKT activator SC79 to patch-clamped lysosomes19. In both HEK293T cells transfected with TMEM175 (Fig. 2c–f) and mouse neurons (Fig. 2h, i, Extended Data Fig. 1e), SC79 fully restored ITMEM175 from starved cells and activated additional current in nutrient-replete cells. In mouse neurons, MK-2206 inhibited native IK. SC79 activated no IK in TMEM175-knockout cells, which suggests that TMEM175 is the only direct lysosomal K+ channel that is targeted by AKT.

In Drosophila S2 cells (which do not have endogenous TMEM175), coexpression of Akt or the application of recombinant AKT protein was required for human TMEM175 to generate robust currents (Extended Data Fig. 2). Together, our data suggest that AKT is obligatory for a functional mammalian TMEM175 channel.

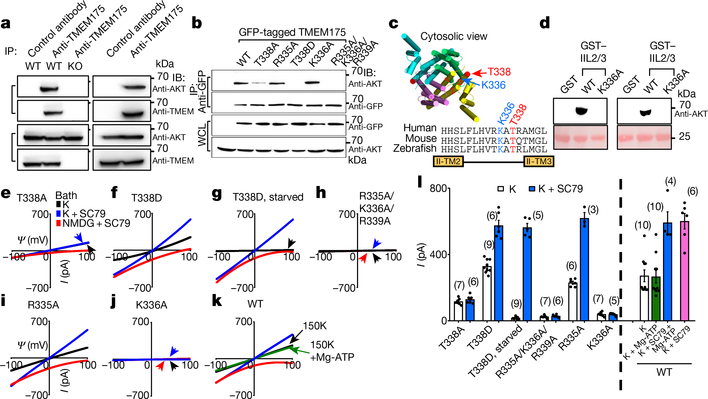

AKT forms a complex with TMEM175

The channel-activating AKT must be bound to a lysosome. Lysosomal AKT interacts with the mTOR–TSC pathway20,21. However, SC79 activated TMEM175 even when mTOR was knocked down or inhibited (Extended Data Fig. 3). In mouse brains, human SH-SY5Y cells and transfected HEK293T cells, TMEM175 immunoprecipitated with AKT: this suggests that TMEM175 and AKT form a complex (Fig. 3a, b, Extended Data Fig. 4a).

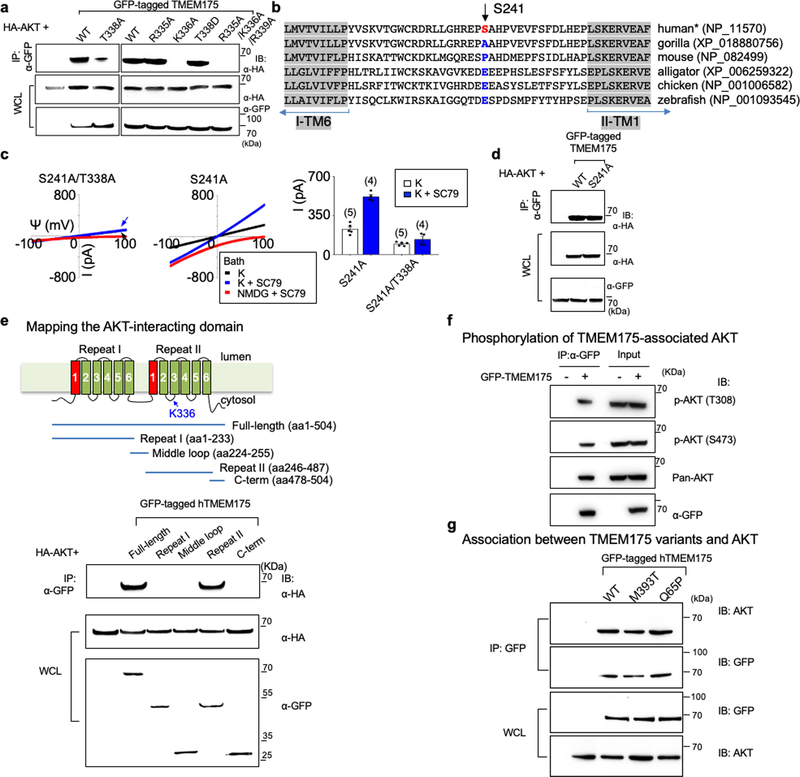

Fig. 3 |. AKT activates TMEM175 via catalysis-independent and interaction-dependent mechanisms.

a, Association between native TMEM175 and AKT. Top two panels, total proteins prepared from wild-type and TMEM175-knockout mouse brains (lanes 1–3) or SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells (lanes 4 and 5) were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-TMEM175 or with a control antibody (anti-UNC79) and blotted with anti-AKT and anti-TMEM175. Bottom two panels, total protein blotted for input control. b, Lysates from HEK293T cells transfected with GFP-tagged wild-type or mutant TMEM175 were immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP and blotted with anti-GFP or with anti-AKT. Whole-cell lysates (WCL) were also blotted for input control. c, Sequence alignment of the T338 region. The locations of T338 and K336 are indicated on the human TMEM175 structure (Protein Data Bank code (PDB) 6WCA). d, Pull down of AKT with human TMEM175–glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion protein. Cell lysates from human AKT1-transfected HEK293T (lanes 1–3) or S2 (lanes 4–6) cells were incubated with glutathione-agarose-bound GST (as a negative control), GST fusion protein of the 19 amino acids of human TMEM175 containing the wild-type TM2–TM3 linker of domain II (GST–IIL2/3; sequence: HHSLFLHVRKATRAMGLLN) or that with the K336A substitution. Top, bound proteins were probed with anti-AKT (top). Bottom, GST fusion proteins were visualized with Ponceau-S staining of the membrane after immunoblotting. e–j, Currents recorded from HEK293T cells transfected with TMEM175 mutants as indicated with (g) or without starvation (wild type shown in Fig. 2d–f). k, Currents recorded with or without Mg-ATP (2 mM) in the bath. l, Averaged IK sizes (at 100 mV) recorded under conditions as indicated. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Numbers of recordings are in parentheses. In e–k, arrows are used to indicate curves that overlap and are not easily distinguished. For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1.

AKT binds close to the channel pore

TMEM175 has one (in mouse) or two (in human) cytosol-facing relaxed AKT-substrate consensus sites around S241 and T338. The conserved T338 is located in the TM2–TM3 linker of repeat II, in close proximity to the cytosolic end of the pore-forming TM1 helix22. Mutating both T338 and S241 or T338 alone—but not the nonconserved S241 alone—to alanine led to markedly reduced IK, with the channel no longer being potentiated by SC79 (Fig. 3b, c, e, l, Extended Data Fig. 4b–d).

Neutralizing the three charged residues around T338 at the same time, or neutralizing K336 alone, disrupted the AKT–TMEM175 association and eliminated ITMEM175 (Fig. 3b, h–j, l). Supporting the idea that AKT binds to the TM2–TM3 linker, the second repeat of TMEM175 associated with AKT (Extended Data Fig. 4e), and a fusion protein containing the 19 amino acids in the linker region—but not the TMEM175(K336A) mutant—pulled down AKT (Fig. 3d).

AKT gates TMEM175 without kinase activity

One way that SC79 might activate TMEM175 is by phosphorylating T338. A T338D substitution had no effect on ITMEM175 (Fig. 3b, f, g, l). In addition, our recording bath contained no ATP or Mg2+ (which are components that are essential for kinase catalysis) but SC79 activated TMEM175 (Fig. 2d–i). Furthermore, adding Mg-ATP to the bath did not increase ITMEM175 (Fig. 3k, l), which suggests that the kinase activity of AKT is unnecessary for activating TMEM175.

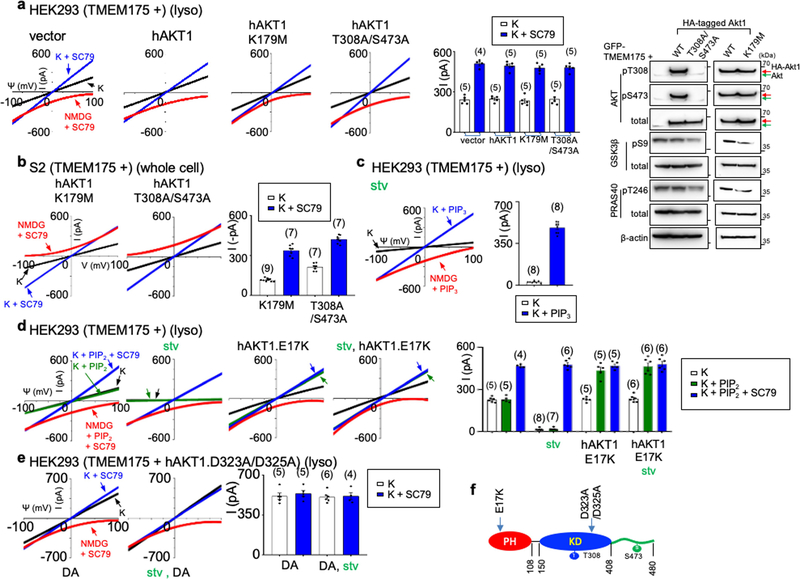

In its canonical activation, AKT changes from closed to an open state (in which the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain is released from the catalytic domain) to subsequently phosphorylate its targets18,23. Allosteric inhibitors that inhibit this conformational change also blocked ITMEM175. By contrast, ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors—which inhibit AKT kinase activity but not the conformational change—had little effect (Fig. 2f, Extended Data Fig. 5). Furthermore, AKT with K179M or T308A/S473A substitutions in the kinase domain that eliminate the kinase activity was as functional as wild-type AKT in supporting ITMEM175 (Extended Data Fig. 6a, b).

A bath application of phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3), which leads AKT to an open state, was sufficient to activate ITMEM175 even in starved lysosomes. Similarly, several mutations in the PH domain that alter the lipid specificity of AKT and/or keep AKT in a constitutively open state also change the lipid sensitivity of ITMEM175 and/or lead to a constitutively activated ITMEM175 that is resistant to starvation. These findings suggest that conformational changes in AKT alone are sufficient to activate TMEM175 (Extended Data Fig. 6c–e).

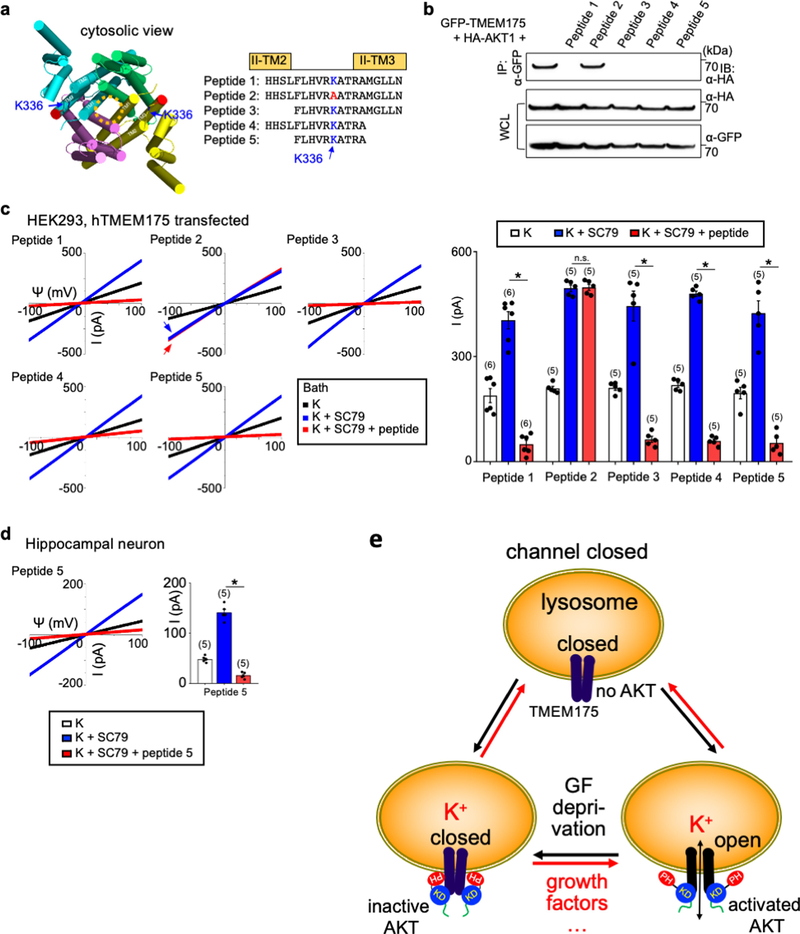

TMEM175 requires AKT to stay open

To test whether the association of TMEM175 with AKT is required for the channel to stay open after activation, we developed inhibitors that dissociate AKT from preassembled TMEM175–AKT complex. After the channel was maximally activated by SC79, a bath application of the inhibitors diminished both heterologously expressed and native ITMEM175 (Extended Data Fig. 7).

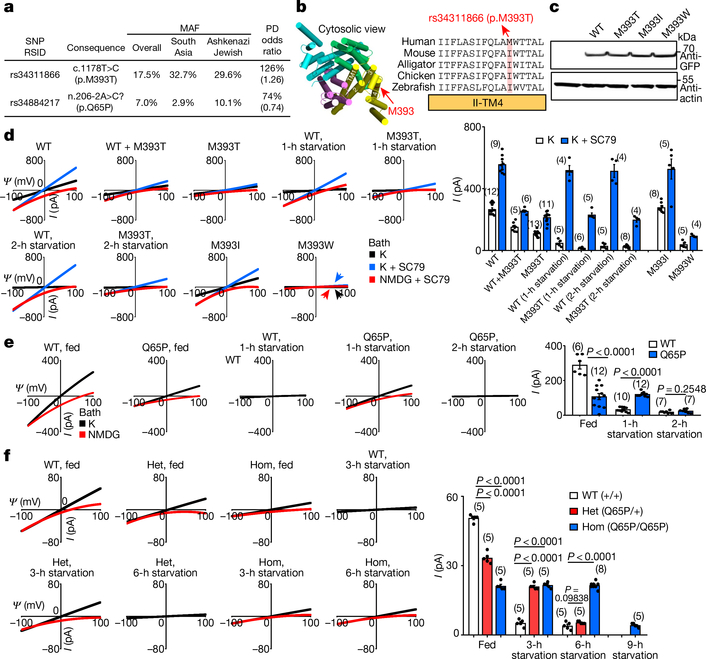

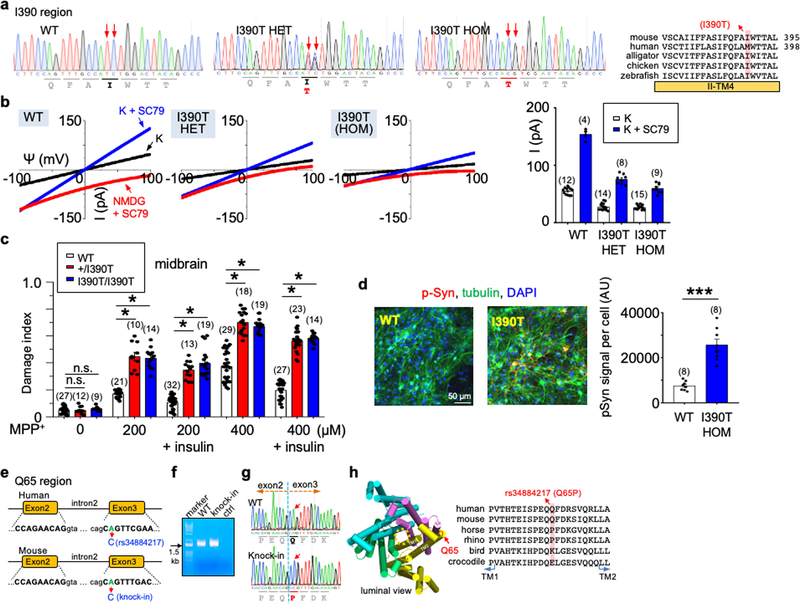

p.M393T causes lysoKGF loss-of-function

Two missense variants in human TMEM175 have minor allele frequencies of over 5% in the general population: rs34311866 (a 17.5% minor allele frequency) (hereafter referred to as p.M393T) and rs34884217 (7% minor allele frequency). Both of these variants have also previously been associated with the risk, onset and/or progression of Parkinson’s disease24–29, with the minor alleles at rs34311866 and rs34884217 conferring an odd ratio of 1.25 and 0.74, respectively, for developing Parkinson’s disease (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4 |. Common TMEM175 variants associated with susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease bidirectionally regulate function of the lysoKGF channel.

a, Variants in human TMEM175 with minor allele frequency (MAF) > 5% (from https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/). The two single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are associated with increased (rs34311866, meta-analysis odds ratio 1.26, 95% confidence interval [1.22, 1.31], P = 6.00 × 10−41) or decreased (rs34884217, odds ratio 0.74, 95% confidence interval [0.69, 0.81], P = 1.56 × 10−12) susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease (PD)25 (data from http://www.pdgene.org/). b–d, Characterization of p.M393T. b, Sequence alignments of M393 region (indicated on structure PDB 6WCA). c, Protein expression levels of wild type and human TMEM175 mutants. Total protein from nontransfected HEK293T cells (lane 1) and cells transfected with GFP-tagged wild-type or mutant human TMEM175 (lanes 2–5) was probed with anti-GFP or anti-actin (for input control). For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1. d, Currents from HEK293T cells transfected with wild-type and/or mutant TMEM175 with or without starvation in HBSS medium for 1 or 2 h, as indicated. e, f, Characterization of the TMEM175(Q65P) variant in HEK293T cells (e) and knock-in mouse neurons (f). e, Currents from wild-type and TMEM175(Q65P) cDNA-transfected HEK293T cells before (0 h, fed) or after (1 or 2 h) starvation. f, Currents from wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (Q65/+, het) and homozygous (Q65P/Q65P, hom) knock-in mouse midbrain neurons before (0 h, fed) or after (3, 6 or 9 h) starvation in DMEM. In d–f, averaged IK sizes (at 100 mV) are shown in the bar graphs. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Numbers of recordings are in parentheses. P values shown are for unpaired two-tailed t-tests.

Compared to the most common form of TMEM175 (with methionine at amino acid position 373; hereater referred to simply as TMEM175), TMEM175(M393T) expressed at a similar level in HEK293T cells (Fig. 4b, c) and also associated with AKT (Extended Data Fig. 4g), but generated smaller (about 40%, P < 0.0001) ITMEM175 with or without SC79 (Fig. 4d). As with TMEM175, starvation for 1 h eliminated these currents (Fig. 4d). Previous studies have also shown that TMEM175(M393T) is not as efficient as TMEM175 when it is used to restore cellular function in cells in which TMEM175 is knocked down30.

Most carriers of p.M393T are heterozygous. We recorded lysosomes cotransfected with TMEM175 and TMEM175(M393T) at 1:1 ratio to model the heterozygous state. Compared to that of TMEM175 alone, the ITMEM175 generated by the mixture was reduced (by 43% for basal and by 54% for SC79-activated) (Fig. 4d). The simplest explanation is that the mutant has a dominant-negative effect and heterodimeric channels22,31,32 that contain a wild type and a mutant copy of TMEM175 behave similarly to a homodimeric mutant. Therefore, ITMEM175 in heterozygous individuals and in individuals who are homozygous for p.M393T are close to each other, and are similar to a situation in which there is only one copy of functional TMEM175 (heterozygous knockout).

Substituting the M393 of TMEM175 with a bulky residue (M393W) markedly reduced ITMEM175. By contrast, replacing M393 with a more-conserved residue (isoleucine)—as found in mouse TMEM175 (I390)—had little effect (Fig. 4b–d).

We also tested the variation in TMEM175(I390T) knock-in mice. IK values in heterozygous and homozygous neurons were reduced to a similar extent as compared to those in wild-type mice, which again suggests a dominant-negative effect (Extended Data Fig. 8a, b).

rs34884217 is a coding variant

In the gnomAD database, rs34884217 is annotated (with uncertainty) as a loss-of-function variant of TMEM175 with disruption in a splice acceptor (n.206–2A>C) (Fig. 4a). We introduced an equivalent A-to-C substitution in Tmem175 in mouse and amplified the whole open-reading-frame cDNAs from the wild-type and knock-in brains. There was a single PCR band and only one transcript species, which suggests no aberrant splicing. Instead, the substitution led to a p.Q65P change in TMEM175 (Extended Data Fig. 8e–g). Thus, rs34884217 (hereafter, p.Q65P) is a coding variant.

p.Q65P causes gain-of-function under stress

The Q65 of TMEM175 is conserved between mice and about 93% of humans, but some mammals (including about 7% of humans) have proline at this position (Extended Data Fig. 8h). As with TMEM175 protein, TMEM175(Q65P) associated with AKT (Extended Data Fig. 4g). In transfected cells, TMEM175(Q65P) led to a reduced ITMEM175 compared to TMEM175 under serum-replete conditions. However, TMEM175(Q65P) was more resistant to starvation: starving cells for one hour almost completely eliminated the wild-type currents, but had little effect on TMEM175(Q65P) (Fig. 4e).

In wild-type neurons, IK was eliminated after a 3-h starvation. However, IK in neurons from homozygous Tmem175Q65P/Q65P knock-in mice was intact even after 6 h, and required 9 h to be eliminated (Fig. 4f). The IK in neurons from heterozygous mice was about 30% smaller than that of wild type under the B27-replete condition but was larger than that of wild type after a 3-h starvation, and required 6 h to be eliminated (Fig. 4f). Thus, p.Q65P is a gain-of-function variant during stress.

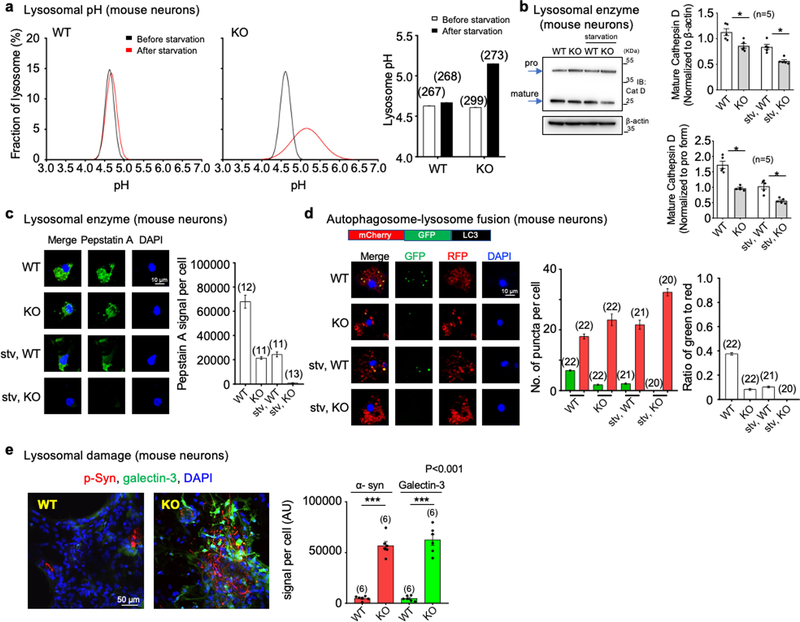

LysoKGF regulates lysosomal function

A potential lysosomal function of TMEM175 is to provide counter ions to achieve acidic pH33. In TMEM175-knockout neurons, lysosomal pH was about 0.5 units more alkaline upon starvation—in contrast with that of wild type, which remained stable (Extended Data Fig. 9a).

Many lysosomal enzymes (such as cathepsin D (CatD)) work optimally at acidic pH. The amount of mature CatD cleaved from the precursor was lower in TMEM175-knockout neurons than in wild type (Extended Data Fig. 9b, c).

We also used LC3 (an autophagosome marker) labelled with green fluorescent protein (GFP) and red fluorescent protein (RFP) to assay autophagosome–lysosome fusion. Compared to wild-type neurons, TMEM175-knockout neurons showed accelerated fusion and an accumulation of undigested autophagosomes (Extended Data Fig. 9d). Similar differences in lysosomal function between wild-type and TMEM175-deficient cells have previously been observed using knockout cell lines and knockdown rat neurons12,34.

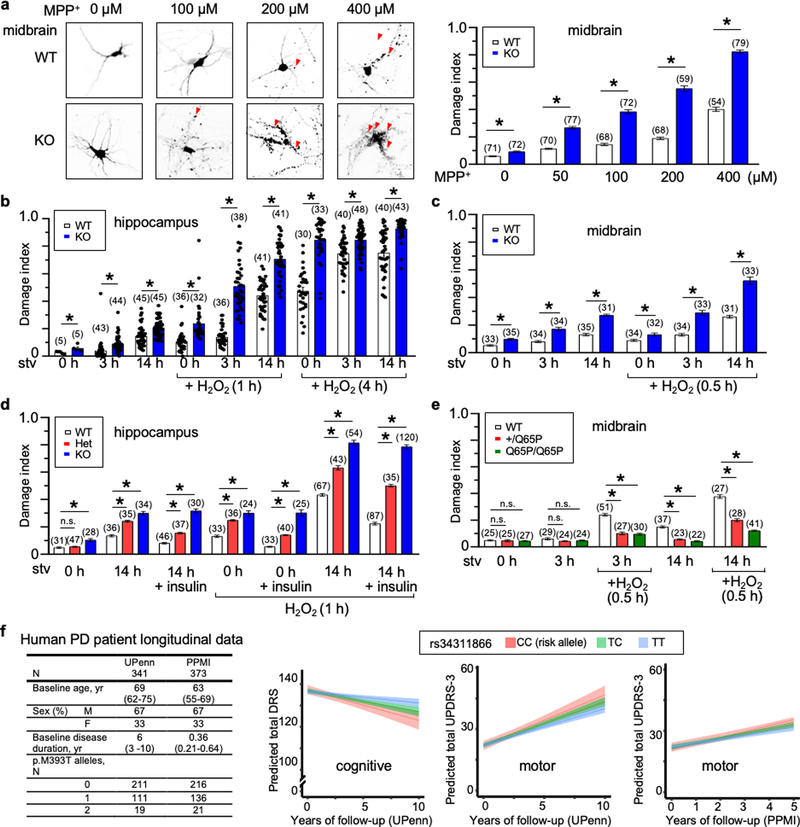

LysoKGF protects neurons

As variants of TMEM175 are associated with neurodegenerative diseases and AKT is known to protect neurons against stress-induced damage25,35,36, we tested whether lysoKGF protects neurons using a culture model in which damage can be quantified well37–39. Compared to wild type, both homozygous and heterozygous TMEM175-knockout neurons showed much more damage in response to insults, such as the neurotoxin MPTP, reactive oxygen species (H2O2) and/or nutrient removal. However, TMEM175(Q65P) neurons had less damage, which suggests that p.Q65P provides additional protection (Extended Data Fig. 10).

α-Synuclein accumulation in mutant neurons

Intraneuronal inclusions (Lewy pathology) comprising misfolded α-synuclein (α-syn) hyperphosphorylated at S129 are a hallmark of Parkinson’s disease40,41. Upon entering neurons, pathogenic α-syn recruits endogenous α-syn to form Parkinson’s-disease-like inclusions42,43. The internalization of extracellular α-syn occurs via the endolysosomal pathway, and lysosomal clearance may slow down the prion-like propagation of α-syn44–46. In an in vitro transmission model in which α-syn preformed fibrils were used to seed endogenous α-syn into Lewy-like inclusions, neurons from the homozygous and heterozygous TMEM175-knockout and TMEM175(I390T) knock-in mice all accumulated markedly increased α-syn phosphorylated at S129 two weeks after exposure, compared to wild type (Fig. 5a, Extended Data Fig. 8d)—consistent with previous findings in cultured rat neurons upon TMEM175 knockdown34. The accumulation of α-syn also led to increased damage to the integrity of lysosomal membranes in the TMEM175-knockout neurons, as assayed using recruitment of galectin 347 (Extended Data Fig. 9e). Although mouse and neuronal models do not fully phenocopy the pathologies of Parkinson’s disease, the findings do suggest that even a partial reduction in TMEM175 (by about 50%) exacerbates the formation of pathogenic α-syn.

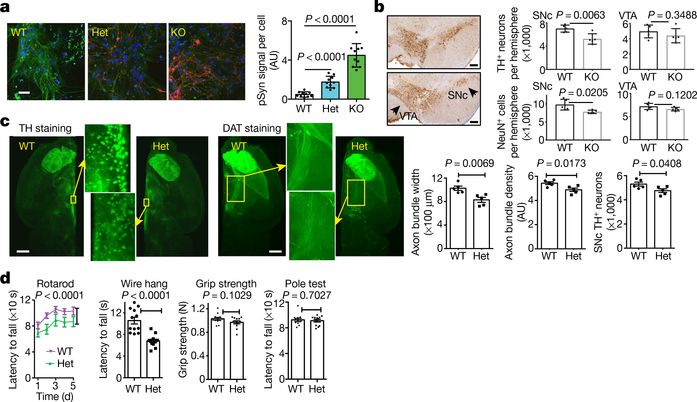

Fig. 5 |. LysoKGF deficiency leads to accelerated spreading of pathogenic α-syn, loss of dopaminergic neurons and impaired motor function in mice.

a, α-Syn spread assay. Cultured mouse hippocampal neurons were seeded with α-syn preformed fibrils and immunostained two weeks later with anti-pSer129 α-syn (pSyn, red), α-tubulin (green) and DAPI (blue). Bar graph shows pSyn signals normalized to the number of cells (n = 10 coverslips). Scale bar, 50 μm. AU, arbitrary units. b, Loss of dopaminergic neurons in TMEM175-knockout mice. Left, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunostaining at the level of ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) from wild-type (top) and homozygous TMEM175-knockout (bottom) littermates (18–22 months old). n = 5 mice for each genotype. Right, quantification of TH-positive neurons and total NeuN-positive cells. Scale bars, 200 μm. c, Brains from wild-type and heterozygous littermates (about 12 months old; n = 5 mice for each genotype) were whole-tissue immunolabelled with anti-TH or anti-dopamine transporter (DAT) and imaged with light-sheet microscopy. Bar graphs show the numbers of dopaminergic neurons and width of axonal bundles. Scale bars, 1 mm. d, Behavioural tests using wild-type and heterozygous littermates (about 12 months old). n = 12 mice for each test. In a–d, P values given are from two-tailed t-tests, except for rotarod in d (two-way analysis of variance).

Dopaminergic neuron loss in TMEM175-knockout mice

We examined whether loss of TMEM175 leads to a reduced survival of midbrain dopaminergic neurons, which represent a vulnerable subpopulation in Parkinson’s disease. Whereas the numbers of tyrosine-hydroxylase-positive neurons between aged wild-type and TMEM175-knockout mice were comparable in the ventral tegmental area, TMEM175-knockout mice showed a decrease of these neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (Fig. 5b).

Using a more sensitive assay with optically cleared tissue and whole-brain image reconstruction, we tested whether a milder reduction (of about 50%) in TMEM175 affects dopaminergic neurons. Compared to wild type, heterozygote mice had a small (about 10%) but significant reduction in the number of dopaminergic neurons and a reduction in the size (around 20%) and the axon density (around 10%) of dopaminergic nerve bundles projecting from the substantia nigra pars compacta to the striatum (Fig. 5c).

Impaired motor skills in mutant mice

In behavioural assays, heterozygote TMEM175-knockout mice performed significantly more poorly than their wild-type littermates in rotarod and wire-hang tests, but showed no obvious deficiency in grip strength and pole tests (Fig. 5d). These findings suggest that mice with haploinsufficiency retain basic muscle function, but are impaired in tasks that require more coordination.

Effects of p.M393T in Parkinson’s disease

We examined a cohort of 341 longitudinally followed (median of 4.08 years, up to a maximum of 12) patients with Parkinson’s disease at the University of Pennsylvania48 (genotypes in panel 1, Extended Data Fig. 10f). In patients with longitudinal cognitive data who did not have dementia at baseline (n = 313 out of 341), p.M393T was associated with the rate of cognitive decline in an additive genetic model (β = 0.453, two-tailed nominal P = 0.003), with p.M393T carriers declining more rapidly than individuals without this variant (panel 2 in Extended Data Fig. 10f). In minor allele dominant models in which carriers of one or two p.M393T variants are considered to be equivalent, we obtained virtually indistinguishable results (β = 0.527, two-tailed nominal P = 0.005)—echoing our cellular findings that having one copy of this variant may be near equivalent to having two. Controlling for GBA-variant carrier status (identified in 14 participants; p.E365K, n = 4; p.N409S, n = 4; p.L483P, n = 4; p.R496H, n = 1; and p.R202*, n = 1) had no effect on these results (β = 0.451, two-tailed nominal P = 0.004).

In patients with longitudinal motor data (n = 336 out of 341), p.M393T was also associated significantly with the rate of motor decline in an additive genetic model (β = −0.345, two-tailed nominal P = 0.032): p.M393T carriers declined more rapidly than those without this variant (panel 3 in Extended Data Fig. 10f). Controlling for GBA-variant carrier status had no effect on these results (β = −0.341, two-tailed nominal P = 0.038).

Finally, we assessed the international Parkinson’s Progression Marker Initiative (PPMI) cohort, which enrolled 423 participants with newly diagnosed Parkinson’s disease from 33 clinical sites in 13 countries, for replication of our results. As the cohort is enrolled at diagnosis, cognitive change (usually a later symptom) is minimal; however, over a median follow-up time of five years, PPMI participants with Parkinson’s disease do show worsening motor function. In 373 participants who have available clinical and genetic data, p.M393T genotypes trended towards association with the rate of motor decline in an additive model (β = −0.322, two-tailed P = 0.066), with p.M393T carriers again declining more rapidly than those without the variant (panel 4 in Extended Data Fig. 10f).

Discussion

We have discovered a growth-factor-activated, kinase-gated lysosomal ion channel, identified the subunits of this channel, elucidated a catalysis-independent channel-gating mechanism by a kinase (Extended Data Fig. 7e), revealed a function in neuronal protection in mice and susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease pathology in humans, and delineated the molecular consequences of two high-frequency genetic variants that are associated with susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease. AKT protects neurons against a wide spectrum of cellular insults18,49,50. AKT receives inputs from numerous growth factors and other stimuli, providing a mechanism by which environmental cues are coupled to lysosomal function. As TMEM175 variants associated with Parkinson’s disease risk are commonly present in the general population (with minor allele frequencies of p.M393T as high as 30% in some ethnic groups), our findings shed light on a considerable proportion of Parkinson’s disease risk in the human population. In addition, enhanced lysoKGF function—as in p.Q65P-carrying neurons—provides added protection against stress-induced damage and is associated with a decreased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. As such, the channel complex may be an attractive target for the development of drugs to alleviate neurodegenerative diseases.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03185-z.

Methods

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized, and—in some experiments (see Reporting Summary)—investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Mice

Mouse use was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. TMEM175-knockout, TMEM175(Q65P) knock-in and TMEM175(I390T) knock-in mouse lines were generated using CRISPR–Cas9 methods, as previously described51. The knockout line was generated with two single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) with target sequences of ttctaatcgtaactgtggcc tgg (exon 3) and tacacttgccttgctcaacc tgg (exon 4) (protospacer adjacent motif sequences in bold). The mutation deletes part of exons 3 and 4 (starting at the codon that encodes A88 in the second transmembrane domain), resulting in an out-of-frame truncation (Fig. 1e). For the generation of TMEM175(Q65P) knock-in line, the sgRNA target was complementary of (cct agcaactaggatcgctgtct) and the single-strand (ss)DNA donor had the sequence of complementary of (gtgctatagggtgagtcttgccattgaaatgaccactgttggatcgtgtgttactttgttctaatagcagtgttcttttcatacagccgtttgacaaaagtatacagaaactgctagcaactaggatcgctgtctacctcatgacatttctaatcgtaactgtggcctggacagcacataccaggtagggaattagacct). For the generation of the TMEM175(I390T) knock-in line, the sgRNA was gcatcttcca gtttgccatc tgg and the ssDNA donor had the sequence of cttgagcgtgtgcgtgtcagctgtgccatcatcttctttgccagcatcttccagtttgccacgtggactacagccctgctgcatcagacagaaacactgcagccagctgtgcaatttggtggg. Cas9 RNA and sgRNAs were synthesized using in vitro transcription with MEGAshortscript T7 kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. AM1354, for sgRNAs) or mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 ULTRA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. AM1345, for Cas9 RNA) and purified using the MEGAclear kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. AM1908). Cas9 RNA, sgRNA and, for knock-in, donor DNA were co-injected into embryos (done by the Transgenic and Chimeric Mouse Core of the University of Pennsylvania). Embryos used for injection were collected from B6SJLF1/J mice for the TMEM175-knockout and C57BL6/J (JAX) mice for the TMEM175(Q65P) and TMEM175(I390T) knock-in lines. F0 founders were crossed to C57BL6/J (JAX) mice to obtain germline transmission. Three independent sublines were used for each line. The TMEM175-knockout and knock-in mice are viable, fertile and do not have obvious gross abnormalities. Mice used for neuronal culture studies had been backcrossed to C57BL6/J mice for more than 5 generations for TMEM175(Q65P) and the TMEM175-knockout, and 1–2 generations for TMEM175(I390T). Knockout mice used for behavioural studies were made from mice backcrossed to C57BL6/J mice for more 10 generations. Littermates were used as controls. The sample sizes were not predetermined. All the mouse uses in Fig. 5 were blinded. The mouse numbers in the behavioural studies in Fig. 5c were randomized before studies.

Cell culture

Mammalian cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Drosophila S2 cells were maintained at room temperature. HEK293T (from ATCC), SH-SY5Y (from ATCC) and S2 (from Gibco) cells were authenticated by the providers and were not further authenticated. Cells were cultured in DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 11965084, for HEK293T), DMEM and F12 (1:1 for SH-SY5Y cells (DMEM from Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 11965084; F12 from Lonza, no. 12–615F), or Schneider’s Drosophila medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 21720024 for S2 cells), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (R&D Systems, no. S11150) and 1× penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 15140122). For neuronal culture, hippocampal, midbrain and cortical neurons were dissociated from mouse brains at postnatal day 0 and digested with filtered papain (Worthington, no. LS003119) as previously described52,53. Neurons were plated on poly-L-lysine-coated 12-mm coverslips in 80% DMEM (Lonza, no. 12–709F), 10% Ham’s F12 (Lonza, no. 12–615F), 10% bovine calf serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. SH30073.03) and 0.5× penicillin–streptomycin. Medium was changed the next day (day in vitro 1) to neurobasal-A medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 10888022) supplemented with 1× B27 supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 17504044), l-glutamate (25 μM), 0.5 mM GlutaMAX Supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 35050061) and 1× penicillin–streptomycin, and—on day in vitro 2—to neurobasal A medium supplemented with 1× B27 supplement, 0.5 mM GlutaMAX supplement and 1× penicillin–streptomycin. The HBSS medium used for HEK293T cell starvation contained (in mM) 110 NaCl, 45 NaHCO3, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2 and 1 MgCl2 (pH 7.4). Starvation for patch-clamp recording was about 2 h unless otherwise stated. Longer starvation times (4 h or overnight) tested also eliminated ITMEM175.

Plasmid DNA constructs

For HEK293T cell expression, the human TMEM175 used for transfection has previously been described12. Yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) or GFP was attached at the N-terminal of human TMEM175 for the identification of transfected lysosomes for patch-clamp recording. The anti-GFP antibody used in the studies also recognizes YFP. Human AKT1 (Flag and haemagglutinin (HA)-tagged, Addgene no. 9021) and the dominant-negative form of AKT (triple mutant K179M/T308A/S473A, Addgene no. 9031) were from Addgene and were cloned in pcDNA3-based vector. Point mutations were introduced using the Gibson Assembly Cloning Kit (New England Biolabs, no. E5510S) and were confirmed with Sanger sequencing.

For expression in Drosophila S2 cells, human AKT1 was cloned into the BamHI (blunted with Klenow polymerase-mediated filling) and EcoRI sites of the pIZT/V5-based vector. The GFP-fused human TMEM175 was cloned into the KpnI (blunted with Klenow) and EcoRI sites of the pIZT/V5-based vector.

For the production of GST fusion proteins used in the GST pull-down assays in Fig. 3d, cDNA encoding wild-type human TMEM175 peptide (amino acids 327–345) (HHSLFLHVRKATRAMGLLN, DNA insert sequenceGGATCCCACCACTCACTCTTCCTGCATGTGCGCAAGGCCACGCGGGCCATGGGGCTGCTGAACTAGGAATTC) or the corresponding K336A mutant (HHSLFLHVRAATRAMGLLN, DNA insert sequence GGATCCCACCACTCACTCTTCCTGCATGTGCGCGCGGCCACGCGGGCCATGGGGCTGCTGAACTAGGAATTC) was cloned into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of the pGEX-6P-2 vector.

Transfection

HEK293T cells were transfected using PolyJet (Signa Gen, no. SL100688) transfection reagent. Drosophila S2 cells were transfected using X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent (Roche, no. 6366244001). Transfected cells were replated on 12-mm poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips about 48 h after transfection. Neurons were transfected between day in vitro 5 and 7 using Lipofectamine LTX reagent with PLUS reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 15338100).

Electrophysiology

Whole-organelle patch-clamp recordings from lysosomes enlarged to about 3 μm with vacuolin 1 treatment were performed at room temperature, as previously described10,12. Each lysosome selected for recording was dissected out using a sharp glass pipette (illustrated in Fig. 1a). For neurons, lysosomes in soma were selected. All recordings were carried out using a ramp protocol (−100 mV to 100 mV in 1 s, Ψhold = 0 mV, as illustrated in the right subpanel of Fig. 1a). Ψ is the voltage across lysosomal membrane, with lumen as the reference54. Outward K+ current (positive) denotes the movement of K+ out of the cytosol (bath) into the lumen. For transfected cells, recordings were done 48–60 h after transfection. To record IK, pipette solution contained (in mM) 145 K-methanesulfonate, 5 KCl and 10 MES (pH 5.5). Unless otherwise stated, bath solutions contained (in mM) 145 K-methanesulfonate, 5 KCl and 10 HEPES (pH 7.2). In the NMDG+ bath, K+ was replaced with NMDG+ (a large ion that is impermeable to the channel). For TPC Na+ current recordings in Extended Data Fig. 3e–h, bath solutions contained (in mM) 140 K-gluconate, 4 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.39 CaCl2, 1 EGTA, 10 HEPES (pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH) and 0.001 PI(3,5)P(2) (water soluble diC8 form, from Echelon Biosciences, no. P-3508). The pipette solution contained (in mM) 145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 MES and 10 glucose (pH adjusted to 4.6 with NaOH). Some of the currents recorded, especially small ones around the reversal potential, may have partial contribution from endogenous lysosomal H+ and Cl− currents.

For whole-cell recording from S2 cells, the pipette solution contained (in mM) 150 KOH, 2.5 MgCl2 and 10 HEPES (pH 7.2). Pipette solution in some recordings in Extended Data Fig. 2h, as indicated, also contained recombinant human AKT1 protein (from Sino Biological, no. 10763-H08B). The bath solution contained (mM) 150 KOH, 10 TEA, 3 HCl, 1 MgCl2 and 10 HEPES (pH 7.2). In the NMDG-containing bath, K+ was substituted with NMDG-methanesulfonate. Recordings were carried out using a ramp protocol (−100 mV to 100 mV in 1 s, Vhold = 0 mV).

Recordings were performed with a MultiClamp 700B Microelectrode Amplifier controlled with pClamp and Clampfit (version 10.4, Molecular Devices), used for data collection and processing. All electrophysiological recordings were repeated in at least two preparations.

Immunoprecipitation, GST pull down and western blotting

Primary antibodies used were anti-β-actin (rabbit monoclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, no. 4970, for Figs. 1f, 2g, 4c, Extended Data Figs. 5b, 6a, 9b, used at 1:3,000 dilution for western blot), anti-GFP (mouse monoclonal, Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. A11120, for Figs. 3b, 4c, Extended Data Figs. 4a, d, f, g, 7b, used at 1:1,000 dilution for western blot; mouse monoclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, no. sc-9996, for Extended Data Fig. 4e, used at 1:2,000 dilution for western blot), anti-TMEM175 (rabbit polyclonal, Proteintech, no. 19925–1-AP, for Figs. 1f, 3a, used at 1:1,000 for western blot), anti-TMEM175 (rabbit polyclonal, Origene, no. TA335429, for Fig. 3a, used at 2 μg ml−1 for immunoprecipitation), anti-Akt (rabbit polyclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, no. 9272, for Fig. 3d, Extended Data Fig. 2d, used at 1:1,000 dilution for western blot), anti-Pan AKT (mouse monoclonal, R&D Systems, no. MAB2055, for Figs. 2g, 3a, b, Extended Data Figs. 4f, g, 5b, 6a, used at 0.2 μg ml−1 for western blot), anti-HA (mouse monoclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, no. sc-7392, for Extended Data Figs. 4a, d, e, 7b, used at 1:1,000 dilution for western blot), anti-phospho-AKT (Ser473) (rabbit polyclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, no. 9271, for Extended Data Figs. 4f, 5b, a, used at 1:2,000 dilution for western blot), anti-phospho-AKT (Thr308) (rabbit monoclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, no. 4056, for Extended Data Figs. 4f, 5b, 6a, used at 1:1,000 dilution for western blot), anti-phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) (rabbit monoclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, no. 9323, for Extended Data Figs. 5b, 6a, used at 1:1,000 dilution for western blot), anti-GSK3β (rabbit monoclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, no. 9315, for Extended Data Figs. 5b, 6a, used at 1:1,000 dilution for western blot), anti-phospho-PRAS40(T246) (rabbit monoclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, no. 2691, for Extended Data Figs. 5b, 6a used at 1:1,000 dilution for western blot), anti-PRAS40 (rabbit monoclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, no. 2997, for Extended Data Figs. 5b, 6a used at 1:1,000 dilution for western blot), anti-CatD (rabbit polyclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, no. 2284, for Extended Data Fig. 9b, used at 1:200 dilution for western blot). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies used for western blot were anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, no. 7074, for Figs. 1f, 3d, 4c, Extended Data Figs. 2d, 5b, 6a, 9b, used at 1:4,000 dilution), and anti-mouse IgG for immunoprecipitation (Abcam, no. ab131368, used at 1:1,000 dilution for Fig. 3a, b, Extended Data Figs. 4a, d–g, 7b; Cell Signaling Technology, no. 7076, used at 1:4,000 dilution for Figs. 3b, 4c, Extended Data Figs. 4d, e, 7b), VeritBlot for immunoprecipitation detection reagent (HRP) (Abcam, no. ab131366, used at 1:4,000 dilution for Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 4f). Protein A agarose used for immunoprecipitation was from Thermo Fisher Scientific (no. 15918).

For HEK293T, SH-SY5Y and Drosophila S2 cells used in Figs. 2g, 3a, b, d, 4c, Extended Data Figs. 2d, 4a, d–g, 5b, 6a, 7b, cells from a 35-mm dish were lysed for 30 min with 400 μl immunoprecipitation buffer containing (in mM) 50 Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 NaCl, 0.1% NP-40 and 1 EDTA, supplemented with EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (PIC, Roche, no. 11873580001). In Extended Data Figs. 4f, 5b, 6a, lysis buffer was also supplemented with phosphatase inhibitor (PhosStop, Roche, no. 4906837001). Lysate was centrifuged at 20,000g for 30 min at 4 °C. Sixty μl of the supernatant was taken out as input. The rest was mixed with 1 μg antibody and incubated at 4 °C for 2 h. Samples were mixed with buffer-equilibrated protein A–agarose at 4 °C for 2 h, spun down (2,000g, 3 min), and washed with immunoprecipitation buffer (3 times, 5 min each). Proteins were eluted for 15 min at 70 °C with 30 μl 1× lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) sample buffer (diluted from 4× with immunoprecipitation buffer) supplemented with 100 mM DTT.

For mouse brain protein used in Figs. 1f, 3a, each brain was homogenized in 1 ml homogenization buffer (5 mM Tris pH7.4 and 250 mM sucrose) with PIC, mixed for 1 h and spun at 1,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. Protein concentration was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 23227). For the immunoprecipitation experiment in Fig. 3a, 1 mg total protein was solubilized in a final volume of 500 μl immunoprecipitation buffer (diluted from 2× immunoprecipitation buffer) at 4 °C for 1 h, followed by spinning at 20,000g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and incubated with 1 μg antibody at 4 °C for 2 h, followed by mixing with buffer-equilibrated protein A–agarose overnight at 4 °C. Proteins were spun down (2,000g, 3 min), washed with immunoprecipitation buffer (3× 5 min), and were eluted for 15 min at 70 °C with 30 μl 1× LDS sample buffer supplemented with 100 mM DTT. Thirty μg of each total protein was loaded as input.

For western blotting in Fig. 1f, an equal amount (50 μg) of protein from each brain was loaded. For immunoprecipitation in Extended Data Fig. 7b, aliquots of total lysate from HEK293T cells was mixed with 10 μM peptide for 2 h at 4 °C before immunoprecipitation.

For the development of peptide inhibitors, the peptides were synthesized at 4-mg scale with >90% purity (Genscript). They were dissolved at 10 mM in ddH2O (for peptides 4 and 5) or DMSO (for peptides 1, 2 and 3).

For the production of GST fusion proteins used for the GST pull-down assay (Fig. 3d), protein expression in 50 ml of BL21(DE3) bacteria transformed with the corresponding DNA was induced with 0.1 mM IPTG for about 3 h at 30 °C. Cells were lysed with B-Per buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 78248), and the protein was purified using glutathione-conjugated sepharose (GE Healthcare, no. 17–0756-01). An aliquot of the glutathione-sepharose-bound GST fusion protein was eluted with glutathione and used to estimate the protein concentration. The remaining sepharose-bound protein was used for the pull-down assays.

Cell lysates containing AKT proteins used in the pull-down assays were prepared from transfected HEK293T and S2 cells. HEK293T cells were transformed with HA-tagged human AKT1 (Addgene plasmid no. 9021). For expression in Drosophila S2 cells, cells were transfected with the HA-tagged human AKT1 subcloned into the pIZT-based vector. Transfected cells were spun down at 1,000g for 5 min. HEK293T cells were washed once with cold PBS. Cells from each 35-mm dish were lysed with 400 μl immunoprecipitation buffer for 30 min. Lysate was centrifuged at 20,000g for 30 min at 4 °C. Sixty μl supernatant was saved as input and 340 μl was transferred to a new tube. Ten μg of agarose-conjugated GST fusion protein was mixed with the 340 μl cell lysate for 2 h at 4 °C and washed with immunoprecipitation buffer 3 times (5 min each). Proteins were eluted with 30 μl 1× LDS sample buffer with 100 mM DTT and used for western blot analysis.

For western blot, proteins were separated using NuPage 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. NP0335) with MOPS SDS running buffer (Novex, no. NP0001), and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes for 1.5 h at 100 V using the Bio-Rad Mini Trans-Blot system. Membranes were preblocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) and incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Following 2× washes (5 min each) with PBST, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature, followed by 5× washes (5 min each) and additional incubation with detection reagents (Hi/Lo Digital-ECL western blot detection kit from Kindle Biosciences, no. R1004). Signals were detected with a camera (Fujifilm corporation digital camera (X-A2)). At least three independent repeats were performed for all biochemical experiments.

RNA isolation and reverse-transcription PCR

Total RNA from mouse brains and S2 cells were isolated using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, no. 74104). First strand cDNA synthesis was performed with 500 ng of total RNA using the SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 18080093) with poly-T primers following the manufacturer’s instruction.

For reverse-transcription PCR (RT–PCR) of mouse TMEM175 used in Extended Data Fig. 8f, nested PCR was performed using two pairs of specific primers. The primer pair used for the first PCR had sequences of 5′ATGTCCAGGCTCCAGACTGAGGA3′ (forward primer) and TTAGCAGGGGTCAGGCAAGAGC (reverse). The sequences for the primer pair used in the nested PCR were GCAGGCAGTGGATTCCGAG (forward) and CACTGAAATCTGCATGAGGTGG (reverse). For the first round of PCR, 25-μl reactions were carried out using Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, no. M0530), dNTP mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. N8080260, 2.5 mM each) and Phusion HF buffer (New England Biolabs, no. B0518) for 20 cycles (30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 60 °C, and 1 min 40 s at 72 °C). One μl of the first PCR product was used as input for the second round of PCR (50 μl, 30 cycles, performed under the same cycling condition as in the first PCR). The PCR products of about 1.3 kb were gel-purified using SpinSmart columns (Denville Scientific, no. CM-500–50) and used for Sanger sequencing.

S2 cell Akt knockdown with double-strand RNA

Double-strand (ds)RNA against Drosophila Akt (also known as Akt1) was produced using in vitro RNA synthesis. To generated the DNA template for RNA synthesis, Drosophila Akt DNA was amplified using nested PCR with S2 cell first-strand cDNA as template. The primers used for the first PCR had sequences of TCAATAAACACAACTTTCGACCTCA (forward) and CGATGCGAGACTTGTGGAA (reverse). The primers used for the nested PCR had T7 sequence attached at the 5′ end and had sequences of TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGCGTTACATCGGGTCATGC (forward, T7 sequence underlined) and TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATACTAATGTGCGACGAGGTG (reverse). For the first round of nested PCR, a 25-μl reaction was carried out using Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, no. M0530), dNTP mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. N8080260, 2.5 mM each) and Phusion HF buffer (New England Biolabs, no. B0518) for 20 cycles (30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 1 min 50 s at 72 °C). One μl of the first PCR product was used as template for second PCR (50 μl, 35 cycles of (30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 64 °C and 1 min 50 s at 72 °C)). The nested PCR product of about 1.6 kb was gel-purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, no. 28704). Sanger sequencing and restriction digestion (with BspEI) were performed to ensure the specificity of the DNA.

The Drosophila Akt dsRNA was synthesized using the MEGAscript T7 Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. AM1334) with the purified PCR product as template as previously described55,56. The dsRNA product was ethanol-precipitated and resuspended in nuclease-free water. For Drosophila Akt knockdown, 15 μg of dsRNA was added to each 35-mm dish on day 1. For cDNA (human TMEM175 and AKT1) transfection with Drosophila Akt knockdown, cells were transfected using X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent 24 h after the addition of dsRNA (on day 2). Cells were collected after 72 h (on day 4) of dsRNA treatment for biochemistry experiments and patch clamping.

AKT knockdown in HEK293T cells with siRNAs

AKT siRNAs and control RNA were from Dharmacon (AKT1: L-003000–00-0005, AKT2: L-003001–00-0005, AKT3: L-003003–00-0005, control: D-001810–10-05). Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher). AKT1, AKT2 and AKT3 siRNA or control siRNA (25 nM each, final concentration) was added to each well of a 24-well plate or a 35-mm dish for 24 h.

Neuronal damage, α-syn pathology seeding and galectin 3 assays

For the neuronal damage assay used in Extended Data Fig. 8c, Extended Data Fig. 10, hippocampal and midbrain neurons cultured on 12-mm poly-lysine coated coverslips were transfected with GFP for 48 h for the visualization of neuronal processes. Transfected neurons were treated with stimuli for the duration as indicated. Treated cells were washed 3 times with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (in PBS) for 20 min at room temperature, followed by 5× washes with PBS. Samples were mounted with ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. P36965). Images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope-based spinning disc confocal microscope with a 20× lens and a 488-nm laser with an emission filter of 525-nm/50-nm bandwidth (for GFP). Damaged neuronal areas were calculated using ImageJ. Blebs and fragmentation were counted as neuronal damage. The damage index was calculated as the ratio of damaged area to the total neuronal area57–59.

For α-syn seeding assay and galectin 3 assay (Fig. 5a, Extended Data Fig. 8d), mouse α-syn preformed fibrils (PFFs) were prepared as previously described60,61, and stored at −80 °C. Before use, PFFs were diluted in PBS (33 ng ml−1) and sonicated for 10 cycles (30-s on and 30-s off) at high power using a Bioruptor Plus (Diagenode). Fifteen μl of PFF solution was added per well in cultures maintained in 24-well plates. After 14 days of treatment, medium was removed and coverslips were washed with PBS. Cells were fixed and permeabilized for 15 min with a mixture of 1% Triton X-100, 4% paraformaldehyde and 4% sucrose at room temperature, followed by 5× washes with PBS. Permeabilized cells were blocked with 3% BSA in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min and incubated with antibody against pSer129 α-syn (mouse monoclonal antibody clone 81A62; 1:8,000 in 3% BSA) and, in the galectin assay, with anti-galectin 3 (rat monoclonal, 1:100 diluted, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, no. sc-8172863,64) in blocking buffer (3% BSA in PBS) for 2 h at room temperature, followed by 5× washes with PBS. Cells were then incubated with Alexa-Fluor-594-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. A-11032, diluted to 2 μg ml−1 final in blocking buffer) and Alexa-Fluor-488-conjugated rabbit anti-α-tubulin antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, no. 5063S, 1:200 diluted), or, for the galectin 3 assay, Alexa-Fluor-488-conjugated rabbit anti-rat secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. A-21210, diluted to 2 μg ml−1 final in blocking buffer) for 2 h, and washed with PBS (5 times). Coverslips were mounted onto glass slides with ProLong Gold antifade mounting reagent with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. P36935). Images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope-based spinning disc confocal microscope with a 20× lens using a 543-nm laser (emission 645/75, for RFP), a 488-nm laser (emission 525/50, for GFP) and a 405-nm laser (emission 460/50, for DAPI).

Autophagosome–lysosome fusion assay

Autophagosome–lysosome fusion assay was carried out in cultured hippocampal cells transfected with the mCherry- and GFP-tagged LC312. Cells were in DMEM, with or without starvation (B-27 removal overnight). Images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope-based spinning disc confocal microscope using a 543-nm laser (for RFP) and a 488-nm laser (for GFP). The numbers of mCherryand/or GFP-positive punta in each cell were counted using ImageJ.

Lysosome pH imaging

Cells plated on glass cover slips, with or without starvation (in DMEM overnight), were loaded with LysoSensor Yellow/Blue DND-160 (Thermo Fisher, no. L7545) for 5 min (1 μM). Cells were washed with imaging buffer containing (in mM) 140 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 K2HPO4, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgSO4 and 5 HEPES (pH 7.4). For the nonstarved group, washing buffer was supplemented with 1× amino acid (Thermo Fisher no. 11130051). Images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope-based spinning disc confocal microscope with a 60× objective, with excitation 405 nm and emission at 460 nm (50-nm bandwidth) and 525 nm (50-nm bandwidth). Calibrations were performed for each cover slip at the end of imaging. Isotonic K+ solutions containing (in mM) 5 NaCl, 155 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 10 glucose, and 25 HEPES supplemented with 10 μM of nigericin and monensin with pH ranging from 4.0 to 7.0 were used as pH-standard solutions. The fluorescence intensity ratios (460 nm/525 nm) obtained with pH-standard solutions were fitted to a Boltzmann sigmoid curve to obtain the pH-standard curve. The pH of each lysosome was calculated by fitting to the standard curve.

Pepstatin A assay

Cells plated on glass cover slips were loaded 1 μM BODIPY FL pepstatin A (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. P12271) for 1 h at 37 °C and DAPI (Millipore Sigma, no. D9542) for 5 min, followed by washes with PBS (5 times). Cover slips were mounted onto glass slides with ProLong Gold antifade mounting reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. P36961). Images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope-based spinning disc confocal microscope with a 488-nm laser (emission 525/50 for pepstatin) and a 405-nm laser (emission 460/50 for DAPI). Neuronal areas were calculated using ImageJ (as in the α-syn seeding assays).

Whole-tissue immunolabelling, optical clearing and light-sheet 3D imaging

Mouse brains were fixed with trans-cardiac perfusion. In brief, each mouse was deeply anaesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (70 mg per kg body weight via intraperitoneal injection) was perfused with 25 ml PBS containing 50 μg ml−1 heparin, followed by another 25 ml PBS containing 50 μg ml−1 heparin, 1% PFA and 10% sucrose. The brain was dissected out, post-fixed in PBS containing 1% PFA at 4 °C for 24 h with gentle shaking, followed by 3× washes (30 min each) with PBS with gentle shaking. Fixed brains were stored in PBS containing 0.02% NaN3 at 4 °C before immunolabelling and optical clearing.

Whole-tissue immunolabelling and optical clearing was performed following the iDISCO method65. All the incubation steps were performed with gentle rotating. Unsectioned fixed brain hemispheres were incubated at room temperature with 20% methanol (diluted in ddH2O) for 2 h, 40% methanol for 2 h, 60% methanol for 2 h, 80% methanol for 2 h and 100% methanol for 2 h. The tissues were decolorized at 4 °C with a mixture of 30% H2O2 and 100% methanol (1:10, v-v) for 48 h, followed by incubation at room temperature with 80% methanol for 2 h, 60% methanol for 2 h, 40% methanol for 2 h, 20% methanol for 2 h and PBS for 2 h.

The tissues were permeabilized at 37 °C with PBS, 0.2% TritonX-100, 0.1% deoxycholate, 10% DMSO and 10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) overnight, followed by blocking overnight at 37 °C with PBSTE (PBS, 0.2% Triton X-100 and 10 mM EDTA-Na (pH 8.0)] supplemented with 5% normal donkey serum and 10% DMSO. Blocked tissues were immunolabelled at 37 °C for 72 h with the intended primary antibody (1:500 diluted, rat anti-DAT, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, no. sc-32258; rabbit anti-TH, Millipore Sigma, no. AB-152) in PBSTE supplemented with 10 μg ml−1 heparin and 5% normal donkey serum, washed at 37 °C with PBSTE supplemented with 10 μg ml−1 heparin for 12 h, with buffer changed every 2 h, followed by immunolabelling at 37 °C for 72 h with corresponding Alexa-Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500 diluted, goat anti-rat IgG, Alexa 647, Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. A21247; goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa 647, Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. A21245) in PBSTE supplemented with 10 μg ml−1 heparin and 5% normal donkey serum. The tissues were further washed at 37 °C for 48 h with PBSTE supplemented with 10 μg ml−1 heparin, with buffer changed every 8 h.

The immunolabelled tissues were incubated at room temperature with 20% methanol (diluted in ddH2O) for 1 h twice, 40% methanol for 2 h, 60% methanol for 2 h, 80% methanol for 2 h, and 100% methanol for 2 h twice. The tissues were then incubated at room temperature with a mixture of dichloromethane and methanol (2:1, v:v) for 2 h twice and 100% dichloromethane for 1 h three times. The tissues were finally incubated at room temperature with 100% dibenzyl-ether for 12 h three times to become optically cleared.

The optically cleared tissues were imaged on a LaVision Biotec Ultra-microscope II equipped with an sCMOS camera (Andor Neo) and a 2×/NA0.5 objective (MVPLAPO) covered with a 10-mm working-distance dipping-cap. The ImSpector Microscope Controller (Version 144) software was supported by LaVision Biotec. The tissues were immersed in the imaging chamber filled with 100% dibenzyl-ether. For imaging at 1.26× (0.63× zoom) magnification, each tissue was scanned by three combined light sheets from the right side with a step size of 4 μm. The image stacks were acquired using the continuous light sheet scanning method without the contrast-blending algorithm.

Imaris (https://imaris.oxinst.com/packages) was used to reconstruct the image stacks obtained from the light-sheet imaging. For the display purpose, a gamma correction of 1.5 was applied to the raw data. Orthogonal projections of the image stacks were generated for the representative 3D images in the figures. Because single DAT-positive axons within the medial forebrain bundle could not be accurately counted at the resolution of light-sheet imaging, we used the width and fluorescence density of axonal bundles to estimate the loss of dopaminergic projections. The width of the axonal bundle at 1 mm anterior to the substantia nigra was manually measured in the reconstructed 3D image of each brain in Imaris. The fluorescence of the axonal bundle at 1 mm anterior to the substantia nigra was quantified in the orthogonal 3D projection image of each brain, with the background signal taken from the area immediately outside the bundle and subtracted by ImageJ. For the quantification of dopaminergic neurons, the TH-positive neurons located in the substantia nigra were manually counted in the reconstructed 3D image of each brain in Imaris.

Immunohistochemistry for midbrain dopamine neurons

For immunohistochemistry used in Fig. 5b, mouse brains were fixed in 4% PFA overnight following trans-cardiac perfusion and then transferred to PBS for sectioning. Forty-μm-thick floating sections in the coronal plane were prepared using a Compresstome (VF-310; Precisionary Instruments). A series containing every fifth section through the rostrocaudal extent of the substantia nigra and VTA were incubated in PBS containing 0.3% H2O2 and 50% methanol for 30 min, and then washed 3× in PBS (with 0.1% Tween 20). Blocking was achieved by a 1.5-h incubation in PBS containing 30% fetal bovine serum and 0.3% Triton-X100. After overnight incubation with primary antibody against either TH (Millipore Sigma, no. TH-16; 1:5,000 in blocking buffer) or NeuN (Millipore Sigma, no. A60; 1:1,000 in blocking buffer), sections were washed 3× in PBS/Tween 20 and transferred to biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (1:1,000; Vector Laboratories, no. BA2000), sections were washed 3× in PBS/Tween 20 and transferred to biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (1:1,000; Vector Laboratories, no. BA2000). Signal was developed using the Vectastain Elite ABC HRP kit (Vector Laboratories, no. PK-6100) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin and mounted onto Superfrost Plus slides and coverslipped in Cytoseal (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Mounted sections were digitized at 20× (Lamina scanner, PerkinElmer) and the number of TH-positive neurons or NeuN-positive nuclei within the substantia nigra and VTA quantified from each section.

Mouse behavioural tests

Mice were group-housed (up to 5 adult mice per cage) in individually vented cages with a 12-h light/dark cycle. Littermates were used as controls. Experiments were carried out following the guidelines published by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. The Animal Care and Use Committee of the School of Medicine at Fudan University approved the protocols used in mouse experiments. All the behavioural experiments were performed during the light phase. A test sequence was established for mice using a computer-generated pseudo-random number. The experimentalists were blinded to the mouse genotype and original label until after the measurements. Both males and female mice were used. All the mice were kept in the behavioural test room, which was under dim red light, for one hour before the start of the experiments. The test protocols were modified based on previously described methods: open field, rotarod and novel object recognition tests66,67, grip strength test67–69, wire hang test70, tail suspension test71 and pole test72. All the tests were performed under red light, except that for open field instrument, which its own white light.

Rotarod test.

Mice were pretrained for 3 consecutive days before the test on a rotarod rotating at 4 rpm for 2 min. They were then tested for 5 days at an accelerating speed (4 to 40 rpm in 2 min), followed by a constant speed of 40 rpm, with a maximum test time of 5 min. Each performance was recorded as the time (in seconds) spent on the rotating rod until the mouse fell off or until the end of the test task. Each test included three repetitions, with an intertrial interval of 60 min to reduce stress and fatigue. The means from the three runs were analysed for each mouse.

Wire hang test.

The wire hang test was designed to assess motor function. Each mouse was placed on the metal wire cage top. The cage top was then inverted and placed about 50 cm above the surface of the soft bedding in the home cage, and was manually shaken at a constant speed (4 times per second) in the air. The latency to when the mouse fell from the cage top to which it hung was recorded. Each test was performed with three trials with 3-h intertrial intervals. The performance is presented as the average of the three trials.

Pole test.

A climbing frame was placed in a basin filled with about 20-cm depth of water (15 °C). Each mouse was placed about 30 cm above the water on a plexiglass rod (0.8-cm diameter, 80-cm long with 20 cm submerged in H2O and 60 cm above the water surface). The time when the mouse fell from the plexiglass rod was recorded. Each test included three repetitions, with an intertrial interval of 60 min to reduce stress and fatigue. The means from the three trials were analysed for each mouse.

Grip strength test.

Before testing, grip training was performed for each mouse to stimulate the grip reflection and to train it to grasp the force measurement crossbar of the instrument to ensure that it could achieve a stable grip for the measurement of forearm grip strength. The mouse was lifted by the tail and, when the two forelimbs were close to the crossbar, it was induced to actively grasp the crossbar with the claws. The acceptable grip standard was that the mouse could actively stretch the claws, hold the rod smoothly, and did not have dodge, limb distortion or resistance. Grip training was run daily for approximately 5–10 min for 3–5 days until it was able to readily perform a double forelimb grip. After the mouse was able to perform a satisfactory grip, the baseline grip strength when the mouse was at a horizontal position with claws grasping the cross bar was measured by gently lifting the mouse by tail close to the crossbar to induce it to actively grasp the claws to the crossbar. The mouse was then pulled back in the horizontal direction until it was pulled off the crossbar, at which the grip force at the crossbar was measured to reflect the largest double forelimb grip strength of the mouse in resisting pulling. The measurement was recorded three times, with one hour between each measurement to avoid mouse fatigue. The mean values were used for each test.

Human clinical studies

The clinical studies were approved by the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained at study enrolment. Subjects were enrolled at the UPenn Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Clinic with a clinical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease as previously reported73. At enrolment and at each subsequent visit, clinical information was obtained and Mattis Dementia Rating Scale-2 (DRS, n = 313)74 to assess cognition and the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III (UPDRS-3, n = 336) to assess motor function were administered at least at yearly intervals. Subjects with a diagnosis of dementia at enrolment, based on a consensus cognitive diagnosis assigned by pairs of experienced physician raters as previously described75, were excluded from DRS analysis, as their advanced cognitive impairment at enrolment makes further cognitive testing unreliable. Clinical assessments and neuropsychiatric testing were performed by trained research staff. At enrolment, blood was obtained from all participants, genomic DNA was extracted and genotype at the TMEM175 index SNP rs34311866 was determined using real-time allelic discrimination with applied Biosystems TaqMan probes, as previously described76. Variants in GBA were identified by a number of methods, depending on time period, all previously described. These included sequencing the entire coding region (n = 213)77, using a custom targeted next-generation sequencing panel for neurodegenerative diseases (MIND-seq, n = 19)73, or genotyping the SNPs rs76763715 (p.N409S), rs2230288 (p.E365K), rs421016 (p.L483P) or rs80356771 (p.R520C). Four participants only had genotyping data available for rs76763715, and genetic data were missing for two participants.

Statistical analysis of clinical data.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for baseline demographics and cognitive testing using available data. Linear mixed-effects78 were used to test for associations between TMEM175 genotype and DRS or UPDRS-3 over time (in years), with covariates of age, sex, and disease duration in various genetic models. The mixed effects model controls for variable follow-up time and variable intervals between follow-up visits. A random intercept was included in each mixed-effects model to account for correlations among repeated measures. Statistical tests were two-sided, and alpha was set at 0.05. All statistical analysis was performed in R (http://www.r-project.org). Data and R-scripts are available from the corresponding authors [upon request.

Other statistical information and reproducibility

Origin 8.0 software was used for all electrophysiology data analyses. Data were compared using unpaired two-tailed t-test, or one-way analysis of variance test between two or more groups, unless otherwise stated. P values with various tests are also given in the Source Data associated with each figure. Numeric data were represented as mean ± s.e.m. Electrophysiological recordings were repeated in at least two independent preparations. Protein chemistry was repeated at least three times.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data availability

Gel pictures used to generate the immunoblot data and PCR results are available in Supplementary Fig. 1. Raw electrophysiological recording data used to generate the current-voltage relationship curves and all other data are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Websites with related data are as follows: PPMI database, www.ppmi-info.org/data; Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD), https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/; PD Gene database, http://www.pdgene.org/; and PDB 6WCA, https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6WCA. Source data are provided with this paper.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Lysosomal currents activated by growth factors.

Lysosomal currents were recorded using a ramp protocol (−100 mV to 100 mV ramp in 1 s with holding voltage of 0 mV) as illustrated in Fig. 1. a, Sizes of K+ currents (IK) recorded at varying voltages (Ψ, −100 mV to 100 mV) from midbrain neurons with (stv) or without (fed) overnight starvation in DMEM containing no B27 nutrient supplement. Averaged IK sizes (at 100 mV, recorded with 150 mM K+-containing bath) are in the right bar graph. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Numbers of recordings are in parentheses. *P < 0.0001, unpaired two-tailed t-test. b, Na+ currents recorded from hippocampal neurons with and without starvation demonstrating that B27 does not activate Na+ currents. The averaged current sizes (at −100 mV) are in the right bar graph (P = 0.226, unpaired two-tailed t-test). Solutions used in the recordings were the same as those used to record the IK in Fig. 1a, b, except that K+ in the bath was replaced with Na+ and 1 μM PI(3,5)P2 was added in the bath (lysosomal Na+ channel requires PI(3,5)P2 for maximum activation). c, IK recorded from TMEM175-transfected HEK293T cells starved in HBSS followed by refeeding with NGF (100 ng ml−1 for 3 h) or BDNF (10 ng ml−1 for 3 h), demonstrating that BDNF and NGF do not activate TMEM175 in HEK293T cells. Activation by insulin (right) was used as a positive control for receptor activation (see Fig. 1f for insulin). Averaged IK sizes (recorded with K+-containing bath, at 100 mV) are in the right bar graph. d, IK recorded from B27-replete midbrain and cortical neurons cultured from wild-type, heterozygous or TMEM175-knockout mice. Averaged IK sizes (at 100 mV, recorded with 150 mM K+-containing bath) are in the right bar graph. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Numbers of recordings are in parentheses. *P < 0.001, unpaired two-tailed t-test. P values (compared to wild type) are as follows: midbrain, P = 0.0007 for heterozygous, P < 0.0001 for knockout; cortex, P < 0.0001 for knockout. e, IK recorded from wild-type and TMEM175-knockout midbrain neurons before (fed) or after (stv) starvation (overnight in DMEM). An AKT activator SC79 (10 μM) was applied to the recording bath during some of the recordings (blue and red traces). Bar graphs in the right show averaged IK sizes (at 100 mV). Data are mean ± s.e.m. Numbers of recordings are in parentheses. Arrows are used to indicate curves that overlap and are not easily distinguished.

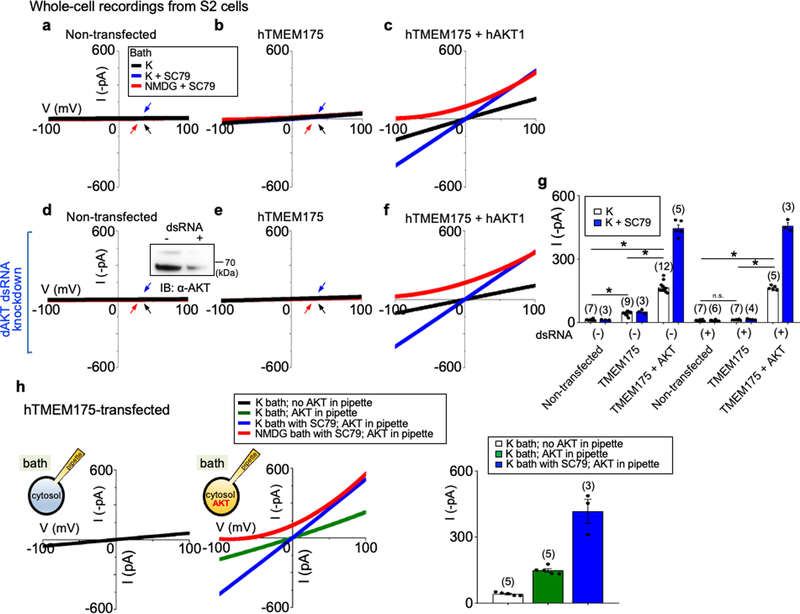

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. AKT is required for the reconstitution of human TMEM175 as a functional ion channel.

a–f, Whole-cell currents were recorded from Drosophila S2 cells without (a–c, h) or with (d–f) endogenous Akt (‘dAKT’) knocked down using dsRNA treatment. a, d, Nontransfected S2 cells. b, e, h, S2 cells transfected with human TMEM175 alone. c, f, S2 cells cotransfected with human TMEM175 and human AKT1. A western blot showing the reduction of Drosophila Akt protein by dsRNA treatment is shown in the inset in d. For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1. g, Summary of current amplitudes (at −100 mV, recorded in K+-containing bath with or without SC79). Recordings were done using a ramp protocol (−100 mV to 100 mV in 1 s, Vh = 0 mV). Bath solution contained 150 mM K+, 150 mM K+ with SC79 (an activator of human AKT) or 150 mM NMDG with SC79, as indicated. In a, b, d, e, arrows are used to indicate curves that overlap and are not easily distinguished. Black, recorded from bath containing K+; blue, recorded from bath containing K+ and SC79; red, recorded from bath containing NMDG and SC79. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Numbers of recordings are in parentheses. In g, *P ≤ 0.05 (compared with those from cells cotransfected with human TMEM175 and human AKT). P values (unpaired two-tailed t-tests) are as follows: without dsRNA treatment, P < 0.0001 for TMEM175 vs nontransfected, TMEM175+AKT vs nontransfected and TMEM175+AKT vs TMEM175; with dsRNA treatment, P = 0.1253 for TMEM175 vs nontransfected, P < 0.0001 for TMEM175+AKT vs TMEM175 and TMEM175+AKT vs nontransfected. h, Whole-cell currents recorded from S2 cells transfected with human TMEM175 alone, with (middle) or without (left) recombinant human AKT1 protein (1 μg ml−1) included in the pipette solution. Right, summary of current amplitudes (at −100 mV; b and g show an additional control without AKT protein in pipette. We further tested the necessary and sufficient role for AKT in ITMEM175 by reconstituting TMEM175 in the Drosophila S2 cell line, which does not have endogenous TMEM175. In HEK293T cells, cotransfection of AKT1 did not further increase ITMEM175 (Extended Data Fig. 6a), consistent with the idea that the three mammalian AKTs are already abundantly expressed in the cells79. S2 cells do not have TMEM175 (which is absent in insects), and have only one Akt gene, making it easier to knock down. In addition, the Drosophila Akt (dAKT) protein is not well-conserved with the mammalian AKTs (61% identity to human AKT1) and is less likely to support human TMEM175 function. For technical reasons, we were unable to enlarge S2 cell lysosomes suitable for patch-clamp recording. We therefore recorded whole-cell currents as an assay for functional channels. Transfecting human TMEM175 alone into S2 cells generated little current (about −20 pA at −100 mV) above the level of endogenous K+ currents (a, b, g). In addition, knocking down Drosophila Akt with dsRNA55 completely eliminated the small ITMEM175 (d, e, g). Cotransfecting human TMEM175 with a human AKT1 (hAKT1), however, led to robust ITMEM175, either with or without the endogenous Drosophila Akt knocked down (c, f, g). The currents were potentiated by SC79 in human AKT cotransfected cells but not in those transfected with TMEM175 alone, supporting the notion that SC79 acts on mammalian AKTs to open the channel. We finally tested whether purified recombinant AKT protein is sufficient to activate TMEM175. In S2 cells transfected with human TMEM175 alone (which had minimal current), application of SC79 into the bath increased the currents to −417.0 ± 53.9 pA (h) (n = 3, −100 mV) when human AKT1 protein was introduced into cytosol via pipette solution dialysis. Together, our data suggest that AKT is obligatory for a functional mammalian TMEM175 channel.

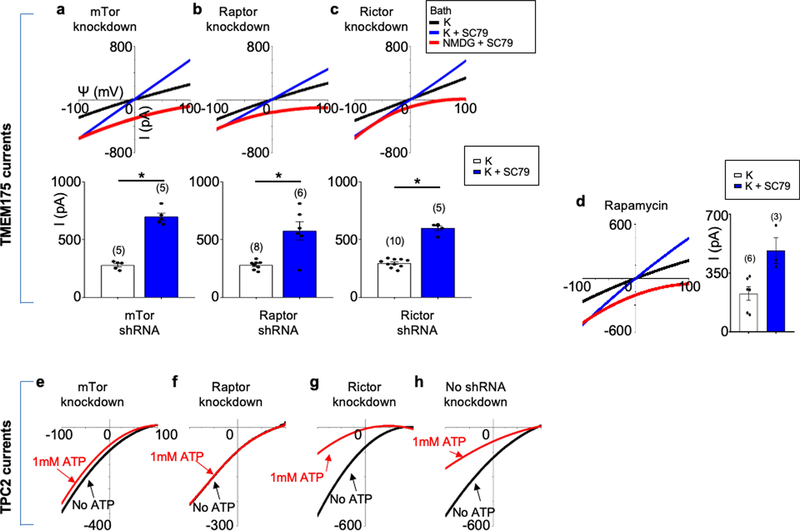

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. mTOR is not required for the activation of TMEM175 by AKT.

a–c, Lysosomal IK currents were recorded from TMEM175-tranfected HEK293T cells with mTOR (a component of both mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes) (a), Raptor (an mTORC1 component) (b) or Rictor (an mTORC2 component) (c) knocked down with short hairpin (sh)RNA lentivirus10. d, Lysosomal IK recorded from TMEM175-tranfected HEK293T cells treated with rapamycin (2 μM, 1 h). Figure 1f provides comparisons with those with no knockdown or rapamycin treatment. *P ≤ 0.05. P values (unpaired two-tailed t-tests; K vs K+SC79 groups) are: P < 0.0001 (mTor shRNA), P = 0.0013 (Raptor shRNA), P < 0.0001 (Rictor shRNA). e–h, Control for mTOR knockdown. Lysosomal Na+ currents were recorded from HEK293T cells transfected with TPC2 as positive controls for mTOR knockdown. TPC2 is a lysosomal Na+ channel that is inhibited by ATP. The ATP sensitivity requires mTORC1 but not mTORC2; knocking down mTOR or Raptor—but not Rictor—reduces the ATP sensitivity10. In f, arrows are used to indicate traces that overlap and are not easily distinguished. Black, recorded before 1 mM ATP was added to the bath; red, recorded after 1 mM ATP was added to the bath. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Numbers of recordings are in parentheses.

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Characterization of TMEM175–AKT interaction and its role in TMEM175 activation.