Significance

Biological metalloclusters catalyze many of the global-scale redox interconversions of the elements, such as the nitrogenase-mediated reduction of N2 to bioavailable NH3. Understanding the mechanisms of these transformations requires knowledge of how the clusters’ individual metal ions contribute to their physical properties and chemical reactivity. This has been an ongoing challenge for the Fe–S clusters of nitrogenases, which feature many Fe sites that are difficult to distinguish spectroscopically. Using the L-cluster (a key biosynthetic precursor to the Mo nitrogenase catalytic cofactor) as a case study, we show that chemical modification of nitrogenase cofactors is a promising strategy for simplifying their spectroscopic analysis and relating their electronic structures to their geometric structures.

Keywords: nitrogenase, metallocofactors, biosynthesis, iron-sulfur clusters

Abstract

Nitrogenases utilize Fe–S clusters to reduce N2 to NH3. The large number of Fe sites in their catalytic cofactors has hampered spectroscopic investigations into their electronic structures, mechanisms, and biosyntheses. To facilitate their spectroscopic analysis, we are developing methods for incorporating 57Fe into specific sites of nitrogenase cofactors, and we report herein site-selective 57Fe labeling of the L-cluster—a carbide-containing, [Fe8S9C] precursor to the Mo nitrogenase catalytic cofactor. Treatment of the isolated L-cluster with the chelator ethylenediaminetetraacetate followed by reconstitution with 57Fe2+ results in 57Fe labeling of the terminal Fe sites in high yield and with high selectivity. This protocol enables the generation of L-cluster samples in which either the two terminal or the six belt Fe sites are selectively labeled with 57Fe. Mössbauer spectroscopic analysis of these samples bound to the nitrogenase maturase Azotobacter vinelandii NifX reveals differences in the primary coordination sphere of the terminal Fe sites and that one of the terminal sites of the L-cluster binds to H35 of Av NifX. This work provides molecular-level insights into the electronic structure and biosynthesis of the L-cluster and introduces postbiosynthetic modification as a promising strategy for studies of nitrogenase cofactors.

Metalloenzymes catalyze global-scale redox reactions that shape the molecular composition of the biosphere. Many such reactions, including H2O oxidation, O2 reduction, CO/CO2 interconversion, N2O reduction, and N2 reduction, are carried out at high-nuclearity metalloclusters (1–7). In these and other examples, the high cluster nuclearity is thought to facilitate efficient catalysis, but it also introduces practical challenges for mechanistic and spectroscopic studies. In particular, techniques that directly probe the metal centers (e.g., Mössbauer spectroscopy, which is exceptionally useful for mononuclear Fe enzymes) are often less insightful for high-nuclearity metalloclusters; with increasing cluster nuclearity it can be difficult or impossible to resolve the spectroscopic responses arising from many metal sites, and it is further challenging to correlate these spectroscopic features to specific sites in the three-dimensional structure (8–16). Thus, the polynuclear nature of complex metalloclusters both underpins their unique functions and, in many cases, precludes a molecular-level understanding of their electronic structures and reactivity.

The nitrogenase catalytic cofactors (FeMoco, FeVco, and FeFeco) as well as their biosynthetic precursors (notably an [Fe8S9C] cluster called “NifB-co” or the “L-cluster”) are prime examples. They are composed of eight metal ions, of which at least seven are Fe (Fig. 1) (7, 17, 18). Their electronic-structure descriptions have undergone multiple revisions, and uncertainties remain about their individual site valences, electronic coupling schemes, and overall charges (19–27). This is in contrast to lower-nuclearity Fe–S clusters (e.g., [Fe2S2], [Fe3S4], and [Fe4S4] clusters) for which relatively robust electronic-structure models have been developed that account for the ample spectroscopic data that have been acquired on these systems (28–31); the slower development of such models for nitrogenase cofactors can be ascribed in large part to their higher number of metal centers and the resulting difficulty associated with analyzing their spectroscopic features.

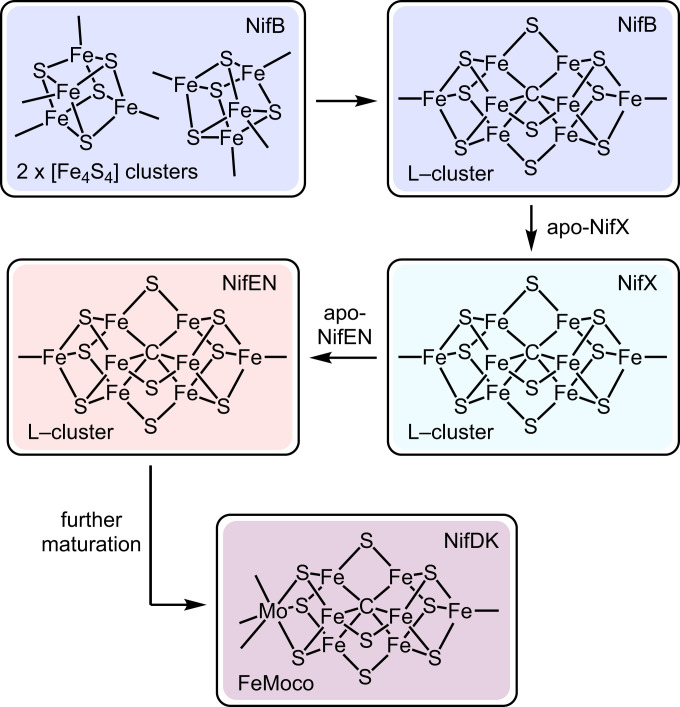

Fig. 1.

Simplified representation of FeMoco biosynthesis highlighting the intermediacy of the L-cluster and the proposed role of NifX in cofactor transport. Additional ligands to the cofactors have been omitted for clarity.

A significant challenge in interpreting the spectroscopic data of these and other high-nuclearity metalloclusters is achieving both spectral resolution and spatial resolution: having the ability to assign spectroscopic features to specific metal sites in a cluster. For nitrogenase cofactors, efforts in this regard have typically relied on coupling X-ray diffraction measurements with other spectroscopic techniques. For example, Einsle and coworkers applied spatially resolved anomalous dispersion refinement to single crystals of the MoFe protein (NifDK), which revealed semiquantitative information about the relative oxidation states of individual metal sites (14). In addition, DeBeer, Rees, and coworkers used X-ray spectroscopic measurements on Se-labeled samples to obtain insights into the oxidation states of the Se-bound Fe sites (32).

In principle, having site-selective control over the incorporation of 57Fe would be exceptionally useful. Samples in which the cofactor contains 57Fe in only specific sites would be functionally indistinguishable from natural-abundance samples, but spectra acquired using 57Fe-specific techniques (e.g., Mössbauer spectroscopy, electron-nuclear double resonance spectroscopy, and nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy) would exhibit features only from the labeled Fe sites. Access to such samples would give spatially resolved information about the chemical bonding, Fe oxidation states, spin density, electron–electron spin coupling, electron–nuclear spin coupling, and vibrational dynamics within the cluster. The power of this approach is illustrated by studies of site-selectively labeled [Fe4S4] proteins, which have provided critical insights into the mechanisms of aconitase and radical SAM enzymes as well as the electronic structures of Fe–S clusters more generally (33–35).

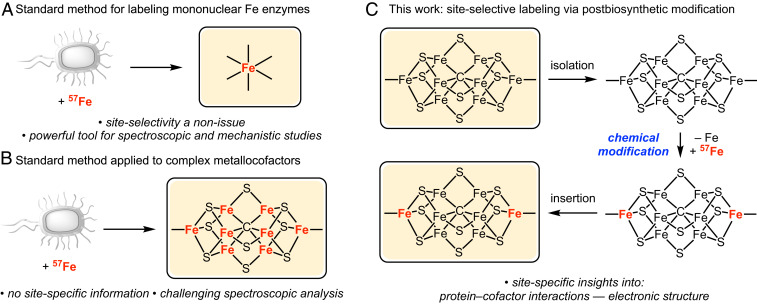

A common method for labeling metalloenzyme active sites with 57Fe involves supplementing the growth medium with 57Fe during protein expression (Fig. 2A). When applied to labeling nitrogenase cofactors such as FeMoco or the L-cluster, this procedure results in complete labeling of all Fe sites (Fig. 2B). Our approach to achieving site-selective 57Fe labeling of nitrogenase cofactors utilizes the cellular machinery for cofactor biosynthesis and a postbiosynthetic, chemical step for incorporating 57Fe in a site-selective manner (Fig. 2C). As a proof of concept, we herein report a method for the high-yielding, highly selective 57Fe labeling of the carbide-containing precursor to FeMoco, the L-cluster. We further demonstrate the utility of this method in studying FeMoco biosynthesis, in particular how the L-cluster binds the nitrogenase maturase, NifX.

Fig. 2.

Methods for 57Fe labeling of metalloproteins. (A) Labeling of mononuclear Fe enzymes for which site selectivity is not an issue. (B) Unselective labeling of complex metallocofactors such as the L-cluster. (C) Postbiosynthetic chemical modification as a strategy for site-selective labeling of the L-cluster. The yellow protein represents a generic metalloenzyme.

Before describing the results, we provide a brief introduction to the L-cluster. The L-cluster is a central intermediate in FeMoco biosynthesis that serves as the structural link between FeMoco and its [Fe4S4]-cluster precursors (Fig. 1). Referred to as both “NifB-co” and the “L-cluster” (17, 36), it is thought to be the product of the radical SAM enzyme NifB and the substrate of the maturase complex NifEN on which it is transformed into FeMoco. The L-cluster was crystallographically characterized on NifEN, and although the data quality precluded an atomic-resolution structure, it was modeled as a D3h-symmetric cluster that resembles FeMoco except with an Fe atom replacing the Mo(homocitrate) moiety (37). Extended X-ray absorption fine structure and Mössbauer spectroscopic experiments further support this structure (23, 38, 39). The L-cluster also has D3h electronic symmetry; the Mössbauer spectrum of fully 57Fe-labeled L-cluster bound to NifX features two partially resolved doublets in a ∼3:1 ratio that were proposed to correspond to the six belt (FeB) and two terminal (FeT) centers, respectively (23). It is because of these features—its critical role in nitrogenase biosynthesis and its simpler Mössbauer spectrum compared to that of FeMoco—that we chose to initiate our studies with site-selective 57Fe labeling of the L-cluster.

Results and Discussion

Our strategy for site-selective isotopic labeling of the L-cluster consists of three steps (Fig. 2C): 1) extraction of the L-cluster into N-methylformamide (NMF), 2) incorporation of 57Fe into the extracted L-cluster, and 3) binding the isotopically labeled L-cluster to a protein for purification and spectroscopic analysis. Protocols for step 1 have been reported using both NifEN–L and NifB/X–L (38, 40); in this work, we extract the L-cluster from Azotobacter vinelandii (Av) NifEN–L. For the 57Fe incorporation step 2, we reasoned that the FeT sites would be more labile than the FeB sites, and that if this is the case the FeT sites could be selectively substituted by exogenous 57Fe. This strategy was inspired in part by the reversible interconversion of site-differentiated [Fe4S4] and [Fe3S4] clusters (33, 35, 41–46) and studies of compositional lability of the P-cluster in nitrogenase mutants (47). Finally, for step 3, we employ the nitrogenase maturase NifX. NifX is proposed to shuttle the L-cluster from NifB to NifEN (Fig. 1) and has been previously shown to bind the L-cluster (23, 48–51). The benefits of performing Mössbauer spectroscopic analysis of the L-cluster on NifX are twofold: 1) NifX features no additional metal-binding sites, and therefore pure samples have no contributing background signals from Fe that is not associated with the L-cluster, and 2) it allows for comparison with the reported Mössbauer spectra of the fully 57Fe-labeled NifX–NifB-co samples (23).

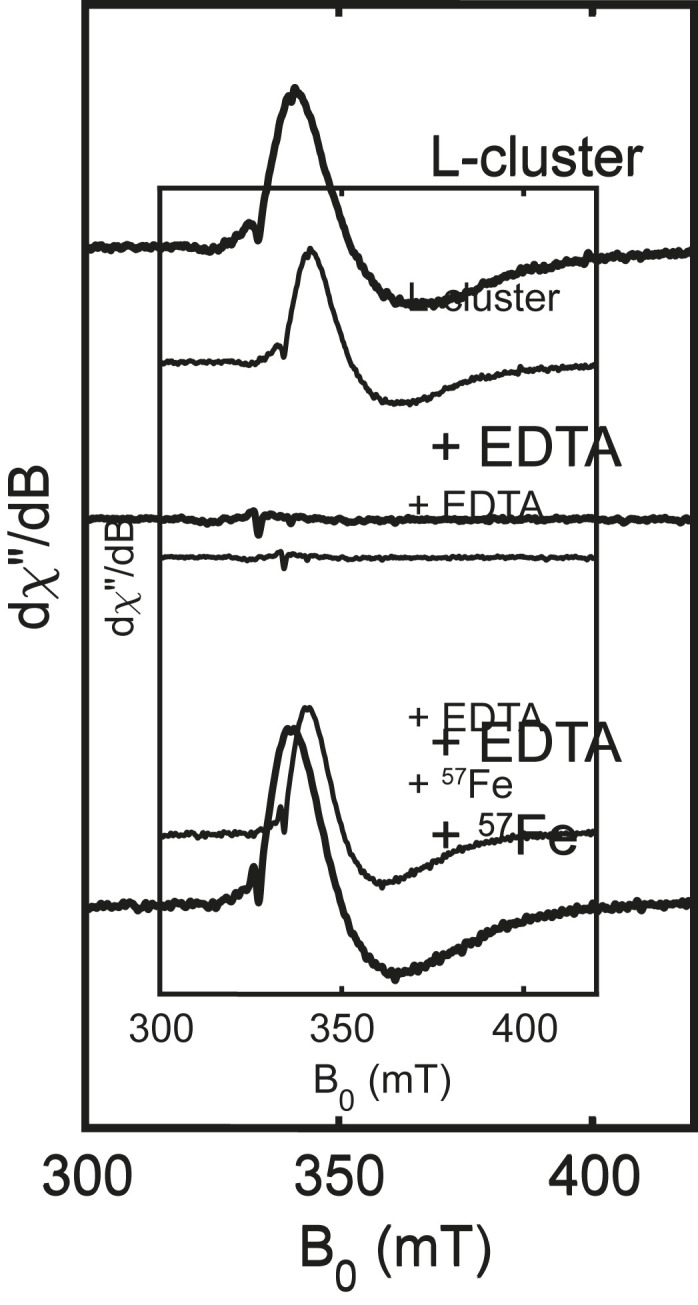

We first used electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy to examine conditions for Fe removal and reconstitution. As previously reported (38), samples of extracted L-cluster in NMF that are oxidized with indigodisulfonate display an EPR signal with giso = 1.94, consistent with its S = 1/2 ground state (Fig. 3, Top). We found that treatment of extracted L-cluster with the chelator ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA) results in quantitative loss of the EPR signal (Fig. 3, Middle) and a slightly lighter brown solution (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Subsequent addition of excess 57Fe2+ as a solution in NMF quantitatively regenerates the original color and EPR signal (Fig. 3, Bottom). These promising initial results are consistent with Fe removal and reconstitution and prompted us to pursue Mössbauer spectroscopic studies.

Fig. 3.

X-band (9.37 GHz) EPR spectra of isolated L-cluster (Top), after addition of EDTA (Middle), and after subsequent addition of 57FeCl2 (Bottom). Spectra were recorded at 15 K with 1 mW power.

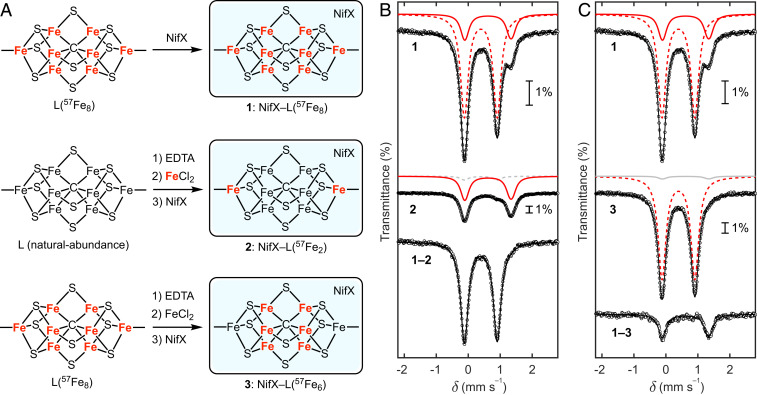

Mössbauer spectroscopic samples were prepared by binding the L-cluster to Av NifX. A reference sample composed of the fully 57Fe-labeled L-cluster [(L(57Fe8)] bound to NifX [NifX–L(57Fe8)] was prepared by extracting L(57Fe8) from 57Fe-labeled NifEN and incubating with NifX (Fig. 4A, sample 1). The 80 K Mössbauer spectrum (Fig. 4 B, Top) shows the expected signals corresponding to the FeB and FeT sites, in agreement with previously reported spectra of NifX–NifB-co(57Fe8) (see Table 1 and SI Appendix for further discussion).*

Fig. 4.

Preparation and Mössbauer spectroscopic analysis of 57Fe-enriched L-cluster samples. (A) Preparation of NifX–L(57Fe8) (sample 1), NifX–L(57Fe2) (sample 2), and NifX–L(57Fe6) (sample 3). (B) Mössbauer spectroscopic comparison of NifX–L(57Fe8) (sample 1) and NifX–L(57Fe2) (sample 2). (C) Mössbauer spectroscopic comparison of NifX–L(57Fe8) (sample 1) and NifX–L(57Fe6) (sample 3). All spectra were recorded at 80 K. Black circles: experimental data. Black lines: total simulations. Red lines: 57Fe-labeled sites. Gray lines: natural abundance 57Fe. Dashed red and gray lines: FeB sites. Solid red and gray lines: sum of the two FeT doublets.

Table 1.

Mössbauer parameters for NifX–L derived from global fitting of the NifX–L(57Fe8), NifX–L(57Fe2), and NifX–L(57Fe6) spectra

| NifX–L(57Fe8) at 80 K | |||

| FeB | FeT (I) | FeT (II) | |

| δ, mm⋅s−1 | 0.39 | 0.61 | 0.62 |

| ΔEQ, mm⋅s−1 | 1.03 | 1.36 | 1.54 |

| Γ, mm⋅s−1 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| Area, %* | 79 | 21 | |

Only one of the two possible sets of parameters for the FeT sites is shown (SI Appendix).

The relative areas of the FeB vs. FeT sites are not 3:1 at 80 K due to differences in their Lamb–Mössbauer factors.

The site-selectively labeled sample NifX–L(57Fe2) was prepared by treating unlabeled, extracted L-cluster initially with EDTA and subsequently with 57Fe2+, followed by incubation with NifX (Fig. 4A, sample 2). The Mössbauer spectrum of the NifX–L(57Fe2) sample is strikingly different from that of the NifX–L(57Fe8) sample (Fig. 4 B, Middle). As for the spectrum of the NifX–L(57Fe8) sample, the strong quadrupole doublet arising from the FeT sites is still present; in contrast, the quadrupole doublet corresponding to the FeB sites is nearly absent. Subtraction of the NifX–L(57Fe2) spectrum from the NifX–L(57Fe8) spectrum cleanly yields a single quadrupole doublet that corresponds to the FeB sites (Fig. 4 B, Bottom). These observations demonstrate that the 57Fe labeling protocol is indeed selective for the FeT sites and that the labeling occurs with high efficiency (discussed below). The very small contribution from the FeB sites to the Mössbauer spectrum of NifX–L(57Fe2) arises from natural-abundance 57Fe, and, potentially, a small degree of 57Fe incorporation into the FeB sites (though we think the latter is negligible; see SI Appendix). Omitting the EDTA treatment step from our protocol also results in 57Fe labeling of the FeT sites, albeit in lower yield (SI Appendix), which highlights the intrinsic lability of the FeT sites.

Interestingly, the quadrupole doublet corresponding to the FeT sites is slightly asymmetric; the high-energy peak is broader than the low-energy peak, and together they are well-simulated by two quadrupole doublets with equal area and slightly different parameters (Table 1 and Fig. 5 A, Top). Because the areas and linewidths of these two doublets are identical, there are two sets of parameters that correspond to the same total simulation and thus cannot be distinguished based on their quality of fit (see SI Appendix for further discussion). Nevertheless, that the quadrupole doublets for the two FeT sites are distinct can be ascribed to differences in their coordination environments; below, we prove this hypothesis using site-selectively labeled samples.

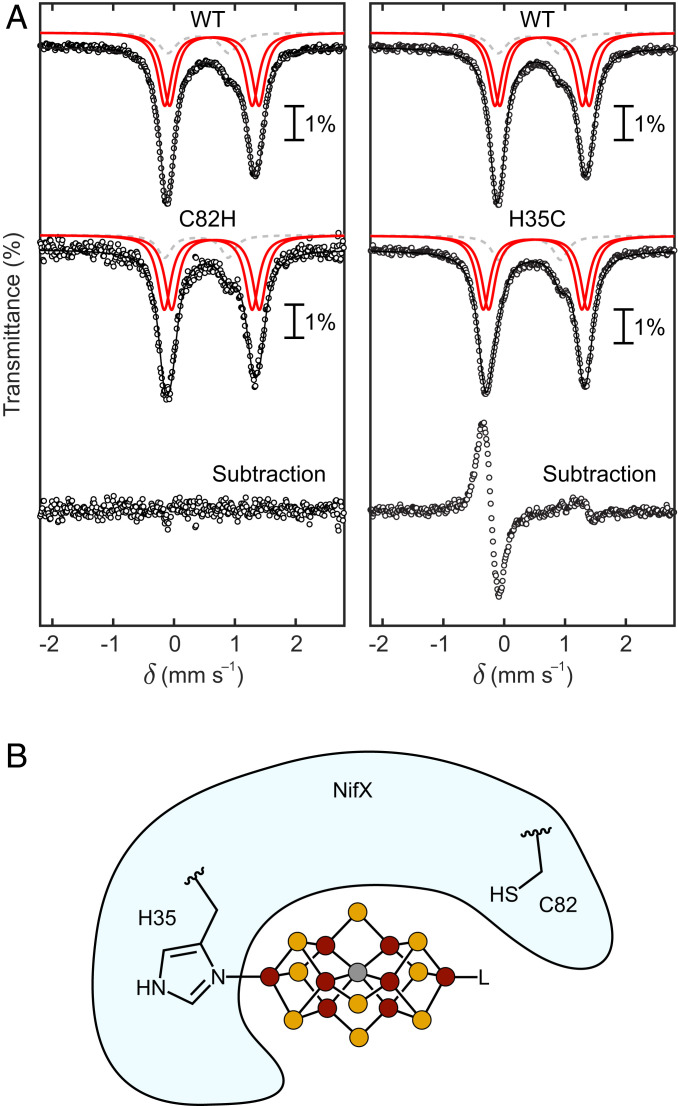

Fig. 5.

Interaction of the L-cluster with Av NifX. (A) Mössbauer spectra of NifX–L(57Fe2) samples. (Left) Comparison of WT–NifX–L(57Fe2) and C82H–NifX–L(57Fe2), showing that the primary coordination sphere of the FeT sites is identical for the two samples. (Right) Comparison of WT–NifX–L(57Fe2) and H35C–NifX–L(57Fe2), showing a change in the primary coordination sphere of one of the FeT sites. All spectra were recorded at 80 K. Black circles: experimental data. Black lines: total simulations. Red lines: 57Fe-labeled FeT sites. Dashed gray lines: natural abundance 57Fe in the FeB sites. See SI Appendix for further discussion of the fitting. (B) Depiction of L-cluster binding to H35 and not C82 of Av NifX.

As a complement to the NifX–L(57Fe2) sample, a sample with an inverted isotope pattern [NifX–L(57Fe6)] was prepared by subjecting isolated L(57Fe8) to the above procedure except adding unlabeled Fe2+ (Fig. 4A, sample 3). This sequence removes 57Fe from the FeT sites, leaving only the FeB sites labeled with 57Fe. As expected, the resulting Mössbauer spectrum shows a major doublet arising from the six FeB sites with only a minor contribution from the FeT sites (Fig. 4 C, Middle). The low intensity of the FeT doublet in the NifX–L(57Fe6) spectrum and the FeB doublet in the NifX–L(57Fe2) spectrum qualitatively indicate very high labeling efficiency and selectivity. Global fitting of these spectra utilizing Lamb–Mössbauer factors derived from the NifX–L(57Fe8) spectrum indicate ∼90% 57Fe incorporation into the FeT sites (SI Appendix). This labeling efficiency was corroborated by measuring the 56Fe and 57Fe content using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), which gave 57Fe/56Fe ratios of the NifX–L(57Fe2) and NifX–L(57Fe6) samples corresponding to 98(±6)% and 88(±10)% exchange of the terminal Fe sites, respectfully. Taken together, the ICP-MS and Mössbauer analyses indicate effectively quantitative exchange of the FeT sites. A complete discussion of the labeling efficiency is provided in SI Appendix.

As an initial demonstration of the utility of this methodology, we now show how site-selectively labeled samples of the L-cluster can provide molecular-level insights into the nature of L-cluster binding to NifX. NifX is thought to be involved in cofactor transport and/or storage during FeMoco biosynthesis (Fig. 1) (17, 50). Although cofactor binding to NifX has been previously demonstrated, NifX has not been structurally characterized, and it is not well understood how NifX binds the L-cluster. To identify which (if any) amino acid side chains function as ligands to the L-cluster, we utilized our site-selective labeling protocol in conjunction with site-directed mutagenesis as described below.

NifX contains two highly conserved residues that could function as ligands to an Fe site of the L-cluster: H35 and C82. Previous mutation studies on the NifX homolog, NafY, suggested that H121 (analogous to H35 of NifX) is involved in FeMoco binding, while the data for C166 (analogous to C82 of NifX) were inconclusive (52). We therefore expected that H35 and possibly C82 of NifX could coordinate the L-cluster. To assess this hypothesis, we acquired Mössbauer spectra of wild-type (WT), C82H, and H35C NifX–L(57Fe2) samples, expecting a significant difference between WT and mutant sample(s) in which the mutated residue binds one of the FeT sites.

The Mössbauer spectrum of the C82H-NifX–L(57Fe2) sample is indistinguishable from that of WT-NifX–L(57Fe2) (Fig. 5 A, Left); subtraction of the two spectra yields a horizontal line with no features that rise above the noise. Based on this result we conclude that C82 does not bind the L-cluster. In contrast, the Mössbauer spectrum of the H35C-NifX–L(57Fe2) sample is clearly perturbed (Fig. 5 A, Right). The average isomer shift decreases from 0.61 mm/s in the WT sample to 0.51 mm/s in the H35C sample, as is particularly evident in the difference spectrum (Fig. 5 A, Right). Such a decrease in isomer shift is consistent with swapping a His imidazole ligand for a Cys thiolate ligand because of the increased covalency of the Fe–S(Cys) bond vs. the Fe–N(His) bond (see SI Appendix for further discussion and relevant comparisons) (53, 54). As for the WT-NifX–L(57Fe2) sample, the H35C-NifX–L(57Fe2) is equally well-simulated by two sets of simulation parameters (SI Appendix); nevertheless, based on the change in average isomer shift, we can conclude that the H35C mutation results in a change in primary-sphere ligation from His to Cys for one of the FeT sites. Taken together, these results demonstrate that H35—but not C82—binds to an FeT site of the L-cluster (Fig. 5B).

In this study, we showed that the two classes of Fe sites in the L-cluster exhibit differential lability, and we exploited this finding to site-selectively incorporate 57Fe into the L-cluster. We now briefly discuss the implications for FeMoco biosynthesis and cofactor dynamics during nitrogenase catalysis.

The final steps of FeMoco biosynthesis involve substitution of one of the FeT sites of the L-cluster with an Mo(homocitrate) fragment to give FeMoco. The mechanism of this transformation is poorly understood, but it must at some point entail breaking all Fe–S bonds between an FeT site and its three μ3-S ligands. In this study, we found that the FeT sites of the L-cluster are inherently labile and that, even under relatively forcing conditions (i.e., with the addition of EDTA), the remainder of the cluster stays intact; this both demonstrates the chemical feasibility of selective Fe loss from the L-cluster during FeMoco biosynthesis and the remarkably robust nature of the [Fe6C] core. The stability of the [Fe6C] core is notable in the context of recent crystallographic studies of nitrogenases that demonstrate cleavage of belt Fe–S bonds during turnover (32, 55–58). That the nitrogenase catalytic cofactors can undergo such dramatic structural changes without falling apart suggests a role for the interstitial C atom in stabilizing the cofactor even as its Fe–S bonds are dynamically broken and reformed. Our findings, along with other biochemical, spectroscopic, and computational work (59–62), support such a proposal.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have reported a protocol for site-selective 57Fe enrichment of the L-cluster, a key intermediate in FeMoco biosynthesis. EPR and Mössbauer spectroscopic analysis indicates that the FeT sites can be reversibly removed and reconstituted in near-quantitative yield and selectivity, allowing for preparation of samples with 57Fe in only the FeT or FeB sites. We illustrated the utility of this methodology by probing the binding of the L-cluster to the maturase NifX. Additional studies, including extensions of this strategy to other nitrogenase cofactors, are currently underway.

Materials and Methods

Av Cell Growth, NifEN Purification, and L-Cluster Isolation.

Protocols were adapted from literature procedures (38, 63); a detailed description is provided in SI Appendix. In short, Av strain DJ1041 (which produces His-tagged, L-cluster loaded NifEN) was grown in nitrogen-replete medium then derepressed in nitrogen-deplete medium. The cells were harvested, flash-frozen in liquid N2, and stored at –80 °C. All subsequent steps were performed in an anaerobic atmosphere (<5 ppm O2). After cell lysis, NifEN was purified from the lysate by immobilized metal affinity chromatography and anion-exchange chromatography. NifEN concentration was estimated by the bicinchoninic acid method using bovine serum albumin as the standard (64). The L-cluster was isolated by acidic denaturation of NifEN, protein precipitation, washing the protein pellet with DMF, and extracting into NMF supplemented with 5 mM sodium dithionite (DTH) and 1 mM thiophenol. The L-cluster concentration was approximated using visible spectroscopy (40).

NifX Overexpression and Purification.

The Strep-tagged apo-NifX encoded plasmid (pDB2109) was first transformed into Escherichia coli BL21-gold(DE3). Cell growth was performed in lysogeny broth media, and NifX overexpression was induced with isopropyl β-ᴅ-1-thiogalactopyranoside. Cells were harvested, flash-frozen in liquid N2, and stored at –80 °C. Strep-tagged apo-NifX was purified aerobically using the published procedure (65). Purified apo-NifX was applied to a Sephadex G-25 column and subsequently eluted with anaerobic buffer containing 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTH. The concentration of apo-NifX was estimated using the calculated absorbance at 280 nm (ε280 = 20,110 M−1⋅cm−1), which was derived from the NifX primary sequence using the ProtParam tool from the ExPASy Proteomics Resource Portal (66). Site-directed mutations in apo-NifX were introduced using the plasmid pDB2109 as a template and the standard PCR protocol used for the PfuUltra High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase. The primers are tabulated in SI Appendix, Table S1. The presence of the point mutation was confirmed by sequencing. The generated plasmids were transformed using BL21-gold(DE3) E. coli competent cells. The growth, overproduction, and purification of apo-NifX variants were conducted as described for the WT apo-NifX.

Site-Selective Labeling of the L-Cluster.

Isolated L-cluster was treated with 15 equiv. EDTA (added as a 100 mM aqueous stock solution) and stirred at room temperature for 5 min. The solution was subsequently treated with 22.5 equiv. FeCl2 added as a 100 mM aqueous stock solution (either natural abundance FeCl2 or 57FeCl2) and incubated for 5 min.

Insertion of the L-Cluster into apo-NifX.

As-isolated or postbiosynthetically modified L-cluster was added dropwise to a stirred solution of apo-NifX (3 equiv. relative to L-cluster) diluted in buffer containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTH at room temperature to a final NMF concentration of 1% (vol/vol). The solution was incubated for 30 min, and NifX–L was subsequently concentrated using an Amicon stirred cell equipped with a 5-kDa filter. To ensure that excess metal ions and unbound L-cluster were removed, holo-NifX was further purified by five, fourfold dilution–concentration cycles through a 3-kDa Amicon centrifugal filter.

Spectroscopy.

Routine methods for Mössbauer, EPR, ICP-MS, and analytical size-exclusion chromatographic experiments were utilized and are described in SI Appendix. The yield and selectivity of 57Fe labeling of the L-cluster were determined using two complementary techniques: Mössbauer spectroscopy and ICP-MS. Detailed analysis and supplementary discussion are provided in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Dennis Dean and Valerie Cash (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University) for providing Av strain DJ1041, the E. coli strain that overproduces Strep-tagged NifX, and advice on overproducing and purifying nitrogenase proteins. We also thank Prof. Lance Seedfeldt (Utah State University) for advice on isolating nitrogenase cofactors and Prof. Catherine Drennan and Francesca Vaccaro (Massachusetts Institute of Technology [MIT]) for assistance with analytical size-exclusion chromatography. We are grateful to the MIT Research Support Committee for providing seed funds for this research. Support for the ICP-MS instrument was provided by a core center grant P30-ES002109 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*Note that in addition to displaying very similar Mössbauer spectroscopic properties, both the L-cluster and NifB-co are EPR-silent in the NMF-isolated and NifX-bound states when reduced by sodium dithionite (DTH). This observation further supports proposals that NifB-co and the L-cluster are identical metalloclusters.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2015361118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Change History

March 16, 2021: Fig. 3 has been updated.

References

- 1.Gray H. B., Stiefel E. I., Valentine J. S., Bertini I., Biological Inorganic Chemistry: Structure and Reactivity (University Science Books, Sausalito, CA, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rees D. C., Great metalloclusters in enzymology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 221–246 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yano J., Yachandra V., Mn4Ca cluster in photosynthesis: Where and how water is oxidized to dioxygen. Chem. Rev. 114, 4175–4205 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon E. I., Augustine A. J., Yoon J., O2 reduction to H2O by the multicopper oxidases. Dalton Trans. 30, 3921–3932 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Can M., Armstrong F. A., Ragsdale S. W., Structure, function, and mechanism of the nickel metalloenzymes, CO dehydrogenase, and acetyl-CoA synthase. Chem. Rev. 114, 4149–4174 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pauleta S. R., Dell’Acqua S., Moura I., Nitrous oxide reductase. Coord. Chem. Rev. 257, 332–349 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Einsle O., Rees D. C., Structural enzymology of nitrogenase enzymes. Chem. Rev. 120, 4969–5004 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindahl P. A., Ragsdale S. W., Münck E., Mössbauer study of CO dehydrogenase from Clostridium thermoaceticum. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 3880–3888 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoo S. J., Angove H. C., Papaefthymiou V., Burgess B. K., Münck E., Mössbauer study of the MoFe protein of nitrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii using selective 57Fe enrichment of the M-centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 4926–4936 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen P., et al., Electronic structure description of the μ(4)-sulfide bridged tetranuclear Cu(Z) center in N(2)O reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 744–745 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Einsle O., Andrade S. L. A., Dobbek H., Meyer J., Rees D. C., Assignment of individual metal redox states in a metalloprotein by crystallographic refinement at multiple X-ray wavelengths. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 2210–2211 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon J., Solomon E. I., Electronic structures of exchange coupled trigonal trimeric Cu(II) complexes: Spin frustration, antisymmetric exchange, pseudo-A terms, and their relation to O2 activation in the multicopper oxidases. Coord. Chem. Rev. 251, 379–400 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krewald V., et al., Metal oxidation states in biological water splitting. Chem. Sci. (Camb.) 6, 1676–1695 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spatzal T., et al., Nitrogenase FeMoco investigated by spatially resolved anomalous dispersion refinement. Nat. Commun. 7, 10902 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartholomew A. K., et al., Exposing the inadequacy of redox formalisms by resolving redox inequivalence within isovalent clusters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 15836–15841 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Stappen C., et al., The spectroscopy of nitrogenases. Chem. Rev. 120, 5005–5081 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burén S., Jiménez-Vicente E., Echavarri-Erasun C., Rubio L. M., Biosynthesis of nitrogenase cofactors. Chem. Rev. 120, 4921–4968 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jasniewski A. J., Lee C. C., Ribbe M. W., Hu Y., Reactivity, mechanism, and assembly of the alternative nitrogenases. Chem. Rev. 120, 5107–5157 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lovell T., Li J., Liu T., Case D. A., Noodleman L., FeMo cofactor of nitrogenase: A density functional study of states M(N), M(OX), M(R), and M(I). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 12392–12410 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lovell T., et al., Metal substitution in the active site of nitrogenase MFe(7)S(9) (M = Mo(4+), V(3+), Fe(3+)). Inorg. Chem. 41, 5744–5753 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukoyanov D., et al., Testing if the interstitial atom, X, of the nitrogenase molybdenum-iron cofactor is N or C: ENDOR, ESEEM, and DFT studies of the S = 3/2 resting state in multiple environments. Inorg. Chem. 46, 11437–11449 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris T. V., Szilagyi R. K., Comparative assessment of the composition and charge state of nitrogenase FeMo-cofactor. Inorg. Chem. 50, 4811–4824 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo Y., et al., The nitrogenase FeMo-cofactor precursor formed by NifB protein: A diamagnetic cluster containing eight iron atoms. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 12764–12767 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegbahn P. E., Model calculations suggest that the central carbon in the FeMo-cofactor of nitrogenase becomes protonated in the process of nitrogen fixation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 10485–10495 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benediktsson B., Bjornsson R., QM/MM study of the nitrogenase MoFe protein resting state: Broken-symmetry states, protonation states, and QM region convergence in the FeMoco active site. Inorg. Chem. 56, 13417–13429 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bjornsson R., Neese F., DeBeer S., Revisiting the Mössbauer isomer shifts of the FeMoco cluster of nitrogenase and the cofactor charge. Inorg. Chem. 56, 1470–1477 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raugei S., Seefeldt L. C., Hoffman B. M., Critical computational analysis illuminates the reductive-elimination mechanism that activates nitrogenase for N2 reduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E10521–E10530 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Girerd J.-J., Papaefthymiou V., Surerus K. K., Münck E., Double exchange in iron-sulfur clusters and a proposed spin-dependent transfer mechanism. Pure Appl. Chem. 61, 805–816 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blondin G., Girerd J. J., Interplay of electron exchange and electron transfer in metal polynuclear complexes in proteins or chemical models. Chem. Rev. 90, 1359–1376 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noodleman L., Peng C. Y., Case D. A., Mouesca J. M., Orbital interactions, electron delocalization and spin coupling in iron-sulfur clusters. Coord. Chem. Rev. 144, 199–244 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noodleman L., Lovell T., Liu T., Himo F., Torres R. A., Insights into properties and energetics of iron-sulfur proteins from simple clusters to nitrogenase. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 6, 259–273 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henthorn J. T., et al., Localized electronic structure of nitrogenase FeMoco revealed by selenium K-edge high resolution X-ray absorption spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 13676–13688 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emptage M. H., Kent T. A., Kennedy M. C., Beinert H., Münck E., Mössbauer and EPR studies of activated aconitase: Development of a localized valence state at a subsite of the [4Fe-4S] cluster on binding of citrate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 80, 4674–4678 (1983). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kent T. A., et al., Mössbauer studies of aconitase. Substrate and inhibitor binding, reaction intermediates, and hyperfine interactions of reduced 3Fe and 4Fe clusters. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 6871–6881 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krebs C., Broderick W. E., Henshaw T. F., Broderick J. B., Huynh B. H., Coordination of adenosylmethionine to a unique iron site of the [4Fe-4S] of pyruvate formate-lyase activating enzyme: A Mössbauer spectroscopic study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 912–913 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hiller C. J., Rettberg L. A., Lee C. C., Stiebritz M. T., Hu Y., “Current understanding of the biosynthesis of the unique nitrogenase cofactor core” in Metallocofactors that Activate Small Molecules: With Focus on Bioinorganic Chemistry, Ribbe M. W., Ed. (Springer, 2018), pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaiser J. T., Hu Y., Wiig J. A., Rees D. C., Ribbe M. W., Structure of precursor-bound NifEN: A nitrogenase FeMo cofactor maturase/insertase. Science 331, 91–94 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fay A. W., et al., Spectroscopic characterization of the isolated iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMoco) precursor from the protein NifEN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50, 7787–7790 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corbett M. C., et al., Structural insights into a protein-bound iron-molybdenum cofactor precursor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 1238–1243 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah V. K., Allen J. R., Spangler N. J., Ludden P. W., In vitro synthesis of the iron-molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase. Purification and characterization of NifB cofactor, the product of NIFB protein. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 1154–1158 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kent T. A., et al., Mössbauer studies of beef heart aconitase: Evidence for facile interconversions of iron-sulfur clusters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79, 1096–1100 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moura J. J., et al., Interconversions of [3Fe-3S] and [4Fe-4S] clusters. Mössbauer and electron paramagnetic resonance studies of Desulfovibrio gigas ferredoxin II. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 6259–6267 (1982). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beinert H., Kennedy M. C., 19th Sir Hans Krebs lecture. Engineering of protein bound iron-sulfur clusters. A tool for the study of protein and cluster chemistry and mechanism of iron-sulfur enzymes. Eur. J. Biochem. 186, 5–15 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou J., Holm R. H., Synthesis and metal ion incorporation reactions of the cuboidal Fe3S4 cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 11353–11354 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou J., Hu Z., Münck E., Holm R. H., Synthesis, stability, and geometric and electronic structures in a non-protein environment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 1966–1980 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Telser J., et al., Investigation by EPR and ENDOR spectroscopy of the novel 4Fe ferredoxin from Pyrococcus furiosus. Appl. Magn. Reson. 14, 305–321 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rutledge H. L., et al., Redox-dependent metastability of the nitrogenase P-cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 10091–10098 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rangaraj P., Ruttimann-Johnson C., Shah V. K., Ludden P. W., Accumulation of 55Fe-labeled precursors of the iron-molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase on NifH and NifX of Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 15968–15974 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rubio L. M., Rangaraj P., Homer M. J., Roberts G. P., Ludden P. W., Cloning and mutational analysis of the gamma gene from Azotobacter vinelandii defines a new family of proteins capable of metallocluster binding and protein stabilization. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 14299–14305 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hernandez J. A., et al., NifX and NifEN exchange NifB cofactor and the VK-cluster, a newly isolated intermediate of the iron-molybdenum cofactor biosynthetic pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 63, 177–192 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.George S. J., et al., Extended X-ray absorption fine structure and nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy reveal that NifB-co, a FeMo-co precursor, comprises a 6Fe core with an interstitial light atom. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 5673–5680 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rubio L. M., Singer S. W., Ludden P. W., Purification and characterization of NafY (apodinitrogenase gamma subunit) from Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19739–19746 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leggate E. J., Bill E., Essigke T., Ullmann G. M., Hirst J., Formation and characterization of an all-ferrous Rieske cluster and stabilization of the [2Fe-2S]0 core by protonation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 10913–10918 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoo S. J., Meye J., Münck E., Mössbauer evidence for a diferrous [2Fe-2S] cluster in a ferredoxin from Aquifex aeolicus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 10450–10451 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spatzal T., Perez K. A., Einsle O., Howard J. B., Rees D. C., Ligand binding to the FeMo-cofactor: Structures of CO-bound and reactivated nitrogenase. Science 345, 1620–1623 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spatzal T., Perez K. A., Howard J. B., Rees D. C., Catalysis-dependent selenium incorporation and migration in the nitrogenase active site iron-molybdenum cofactor. eLife 4, e11620 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sippel D., et al., A bound reaction intermediate sheds light on the mechanism of nitrogenase. Science 359, 1484–1489 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kang W., Lee C. C., Jasniewski A. J., Ribbe M. W., Hu Y., Structural evidence for a dynamic metallocofactor during N2 reduction by Mo-nitrogenase. Science 368, 1381–1385 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wiig J. A., Lee C. C., Hu Y., Ribbe M. W., Tracing the interstitial carbide of the nitrogenase cofactor during substrate turnover. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 4982–4983 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dance I., Mechanisms of the S/CO/Se interchange reactions at FeMo-co, the active site cluster of nitrogenase. Dalton Trans. 45, 14285–14300 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grunenberg J., The interstitial carbon of the nitrogenase FeMo cofactor is far better stabilized than previously assumed. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56, 7288–7291 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rees J. A., et al., Comparative electronic structures of nitrogenase FeMoco and FeVco. Dalton Trans. 46, 2445–2455 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shah V. K., Brill W. J., Isolation of an iron-molybdenum cofactor from nitrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74, 3249–3253 (1977). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith P. K., et al., Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 150, 76–85 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jiménez-Vicente E., et al., Application of affinity purification methods for analysis of the nitrogenase system from Azotobacter vinelandii. Methods Enzymol. 613, 231–255 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gasteiger E., et al., ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3784–3788 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.