Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has necessitated adoption of telerehabilitation in services where face-to-face consultations were previously standard. We aimed to understand barriers to implementing a telerehabilitation clinical service and design a behavior support strategy for clinicians to implement telerehabilitation. A hybrid implementation study design included pre- and post-intervention questionnaires, identification of key barriers to implementation using the theoretical domains framework, and development of a targeted intervention. Thirty-one clinicians completed baseline questionnaires identifying key barriers to the implementation of telerehabilitation. Barriers were associated with behavior domains of knowledge, environment, social influences, and beliefs. A 6-week brief intervention focused on remote clinician support, and education was well received but achieved little change in perceived barriers to implementation. The brief intervention to support implementation of telerehabilitation during COVID-19 achieved clinical practice change, but barriers remain. Longer follow-up may determine the sustainability of a brief implementation strategy, but needs to consider pandemic-related stressors.

Keywords: Implementation science, Occupational therapy, Physical therapists, Rehabilitation, Telehealth

List of abbreviations: COM-B, behavior change—capability, opportunity and motivation; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; TDF, theoretical domains framework

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has necessitated the transition of traditional face-to-face health care delivery to models that limit contact between patients and health care professionals.1 This has accelerated the shift to the use of telehealth services—the provision of health care at a distance using telecommunication or virtual technology2—on a global scale.3

Telerehabilitation has demonstrated efficacy for a variety of chronic health conditions.4 Yet, despite trial evidence for the benefit of telerehabilitation in chronic illness, clinical uptake remains limited. By understanding why clinicians experience challenges to using telerehabilitation, we may then be able to support its implementation.

The theoretical domains framework (TDF) explores the barriers to and facilitators of behaviors that may influence implementation of evidence into practice.5 The TDF comprises 14 behavioral domains that can be mapped to 3 key components relating to capacity for behavior change—capability, opportunity and motivation (COM-B).6 Applying the TDF alongside the COM-B has been used to design behavioral interventions,6 including in the rehabilitation therapy setting.7 Using the TDF with the COM-B, we aimed to (1) understand barriers and enablers to implementing telerehabilitation with community outpatients during COVID-19 and (2) design and pilot a behavior support program to aid clinician implementation of telerehabilitation.

Methods

A hybrid implementation design to determine the utility of a brief implementation intervention was employed. Hybrid implementation models use a dual focus, in this case testing of an implementation strategy while simultaneously observing the clinical intervention.8 Such hybrid implementation designs are useful where the governing health policy requires implementation of an intervention even when effectiveness may not be clearly established.8 Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at Monash University (2020-24068-43168) and participants provided informed consent.

Clinicians within a group of private practices across 3 Australian cities (Sydney, Melbourne, Perth) were invited to participate. Rehabilitation services provided through the practices included group and individual rehabilitation for children and adults with neurologic, ageing, or musculoskeletal disability provided by physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

To understand capacity for behavior change, a questionnaire based on the TDF (table 1 ) was made available to clinicians online for completion in the first week of April 2020, being within week 1 of the Australian government declaration of social isolation restrictions to combat the spread of COVID-19. An online survey was chosen to ensure anonymity of responses. Survey questions were designed to gain information relative to each domain of the TDF with a minimum of 2 and maximum of 4 questions for each domain.9 Participants rated their responses using a 7-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, disagree, strongly disagree). Survey responses were reviewed in relation to the TDF and core components of capacity for behavior change—capability, opportunity, and motivation.6 In addition, key stakeholders (management and frontline clinicians) were engaged in order to develop the implementation strategies to be piloted. The researchers used the behavior change wheel to select the implementation strategies linked to the identified barriers and enablers from the survey10 with the goal of selecting strategies most likely to address key barriers identified by stakeholders.

Table 1.

Survey responses mapped to the 14 domains of the theoretical domains framework

| TDF Domain (Total No. of Questions) | Example Questions | Baseline Mean ± SD (Range) N=31 |

Postintervention Mean ± SD (Range) n=26 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge (5)∗ | I am aware of the content of effective telerehabilitation programs. | I am aware of the objectives of a telerehabilitation program. | I know what my responsibilities are, with regard to delivering a therapy session using telerehabilitation. | I know how to use telerehabilitation. | 3±1 (1-7) | 3±1 (1-7) |

| Skills (3) | I have received training regarding how to deliver telerehabilitation. | I have the skills needed to deliver telerehabilitation. | I have been able to practice using telerehabilitation. | 4±2 (1-7) | 3±1 (1-6) | |

| Social/professional role and identity (3)∗ | Delivering therapy sessions using telerehabilitation is part of my role. | It is my responsibility to deliver therapy sessions according to telerehabilitation protocols. | Delivering therapy sessions using telerehabilitation is consistent with other aspects of my job. | 3±2 (1-7) | 3±1 (1-7) | |

| Beliefs about capabilities (6) | I am confident that I can plan and deliver therapy sessions with my clients using telerehabilitation protocols. | I am capable of planning and delivering telerehabilitation, even when little time is available. | I have the confidence to plan and delivery therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols even when other professionals I work with are not doing this. | I have the confidence to plan and deliver therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols even when the clients who attend the service are not receptive. | 4±1 (1-7) | 3±1 (1-7) |

| Optimism (3) | In uncertain times, when I plan and deliver therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols, I usually expect that things will work out okay. | When I plan and deliver therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols, I feel optimistic about my job in the future. | I do not expect anything will prevent me from using telerehabilitation to deliver therapy to my clients. | 4±1 (2-7) | 3±1 (1-6) | |

| Beliefs about consequences (4)∗ | I believe applying telerehabilitation protocols to each of my clients’ sessions will lead to benefits for the clients who attend the service. | I believe applying telerehabilitation protocols to each of my clients’ sessions will benefit public health (ie, health of the whole population). | In my view, applying telerehabilitation protocols to each of my clients’ sessions is useful. | In my view, applying telerehabilitation protocols to each of my clients’ sessions is worthwhile. | 3±1 (1-6) | 3±1 (1-6) |

| Reinforcement (3) | I get recognition from management at the organisation where I work, when I use telerehabilitation to deliver my clients’ sessions. | When I use telerehabilitation to deliver my clients’ sessions, I get recognition from my colleagues. | When I use telerehabilitation to deliver my clients’ sessions, I get recognition from those who it impacts. | 4±1 (1-6) | 3±1 (1-6) | |

| Intentions (3) | I intend to apply telerehabilitation protocols to each/every one of my clients’ sessions. | I will definitely apply telerehabilitation protocols to each/every one of my clients’ sessions. | I have a strong intention to apply telerehabilitation protocols to each/every one of my clients’ sessions. | 4±1 (1-7) | 4±2 (1-6) | |

| Goals (3) | Compared to my other tasks, planning how and delivering my therapy using telerehabilitation is a higher priority on my agenda. | Compared to my other tasks, planning how and delivering my therapy using telerehabilitation is an urgent item on my agenda. | I have clear long-term goals related to applying telerehabilitation protocols to each of my clients’ sessions. | 4±1 (1-7) | 4±1 (1-7) | |

| Memory, attention and decision processes (1) | Applying the telerehabilitation protocols to each of my clients’ sessions is something I do automatically. | 5±1 (2-7) | 4±2 (1-7) | |||

| Environmental context and resources (5)∗ | In the organisation I work, all necessary resources are available to allow me to deliver my planned therapy using telerehabilitation protocols. | I have support from the management of the organisation to deliver my planned therapy using telerehabilitation protocols. | The management of the organisation I work for are willing to listen to any problems I have when delivering my planned therapy using telerehabilitation protocols. | The organisation I work for provides the opportunity for training to deliver my planned therapy using telerehabilitation protocols. | 3±1 (1-6) | 3±1 (1-6) |

| Social influences (4)∗ | People who are important to me think that I should deliver therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols. | People whose opinion I value would approve of me delivering therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols. | I can count on support from colleagues whom I work with when things get tough with delivering therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols at each therapy session. | Colleagues whom I work with are willing to listen to my problems I have when delivering therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols at each therapy session. | 3±1 (1-6) | 3±1 (1-6) |

| Emotion (3)∗ | I am able to deliver therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols, without feeling anxious. | I am able to deliver therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols, without feeling distressed or upset. | I am able to deliver therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols, even when I feel stressed. | 3±1 (1-7) | 3±1 (1-5) | |

| Behavioral regulation (5) | I have a detailed plan of how I will deliver therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols. | I have a detailed plan of how I will deliver therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols when patients who usually attend the service are not receptive. | I have a detailed plan of how I will deliver therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols when there is little time. | It is possible to adapt how I will deliver therapy according to telerehabilitation protocols to meet my needs as a rehabilitation therapist. | 4±2 (1-7) | 3±1 (1-7) |

Behavior domains identified as potential targets to support an implementation strategy.

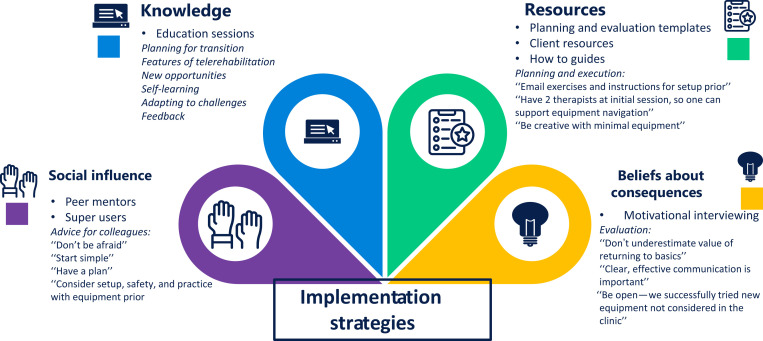

Our brief intervention comprised group education delivered over videoconferencinga once weekly for 6 weeks. Training sessions were recorded and stored for point-of-care access and accompanied by a repository of resources to assist planning and delivery of telerehabilitation. Training was delivered by clinician researchers with experience in telerehabilitation and implementation science. As well clinician superusers who had real-world experience of implementing telerehabilitation within their clinical practice provided accounts of their experience, learnings, and recommended resources (fig 1 ).

Fig 1.

Implementation strategies employed according to barriers identified by clinicians.

Clinicians were resurveyed at the conclusion of the 6-week implementation support program. Survey data were downloaded from Survey Monkey and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics.b Data are reported as number and/or proportion. Likert-scale survey responses are reported as mean ± SD. Open-ended survey responses are reported narratively.

Results

Thirty-one clinicians completed the questionnaire at baseline and 26 at post-intervention. Most of the clinicians were physiotherapists (n=27, 87%) and 4 were occupational therapists (13%). Nearly two-thirds of surveyed clinicians (65%) saw clients on at least 4 days in the week, with the frequency of daily client consultations ranging from 1 to 20. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, most client consultations took place in the outpatient clinic (72%). Previous telerehabilitation experience was limited with only 10% having used telerehabilitation for assessment of clients and monitoring of therapy sessions, 7% having used telerehabilitation to deliver therapy sessions, and 3% using telerehabilitation for group therapy programs.

Baseline questionnaire responses identified 6 behavior domains (see table 1) to support so as to maximize implementation of telerehabilitation. Four domains—knowledge, environmental context and resources, social influence, and beliefs about consequences—were addressed in our strategy (fig 1). The domains of social/professional role and identity and emotion relate to how an individual views themselves and their own emotional reaction to experiences and circumstances, and are beyond the scope of a brief intervention.11 Topics covered key requirements for telerehabilitation implementation (knowledge), preparing to deliver therapy via telerehabilitation (environmental context and resources), delivering a telerehabilitation training session (knowledge, skills, environmental context and resources), motivational interviewing (beliefs about consequences), and real-world experiences (social influence). Each online education session lasted mean ± SD 46±12 minutes with 10±5 participants.

At the conclusion of the 6-week brief intervention, more than half of all client consultations (58%) were taking place via telerehabilitation. The proportion of participants who reported using telerehabilitation for assessment and monitoring rose to 54%, for delivery of therapy sessions to 27%, and for 12% of group therapy programs. Despite good engagement from clinicians with online training sessions, and access to recorded training sessions and resources by 30% of clinicians, there was no change in questionnaire responses by TDF domain (see table 1) at the end of the intervention.

Discussion

This study reports a brief intervention to support implementation of telerehabilitation in community rehabilitation. The implementation strategy covered key behaviors identified as barriers to telerehabilitation—knowledge, resources, social support, and beliefs about consequences. The intervention was well received, resulted in some practice change, but had limited effect on perceived barriers and enablers to telerehabilitation implementation.

Global circumstances associated with COVID-19 necessitated a rapid transition of rehabilitation services to remote delivery models, creating new challenges for patients, clinicians, and careers. Previously identified barriers to using telerehabilitation in clinical practice include changes to workload, access to equipment and technology support, and time constraints.12 Clinician training is also key to the success of telehealth implementation.13 Our brief implementation strategy was focused on remote clinician support and education. It is possible our findings, while addressing knowledge, environmental context and resources, and social support as a part of training, failed to adequately prepare or support clinicians to incorporate telerehabilitation within their perceived workload demands, or to address technology resources clinicians perceive necessary. Lack of change in survey (Likert scale) ratings associated with key behavioral domains on the TDF may reflect the brief nature of the intervention, limited ability of the questionnaire to detect change, that clinicians were recruited from only a single rehabilitation provider, or ultimately the reduced the effect on clinical service delivery due to low numbers of COVID-related cases in Australia.

Implementation of telerehabilitation does not occur in a vacuum. In some chronically ill populations, more than one-third of individuals have never accessed the internet,14 and 30%-40% have no interest in accessing rehabilitation services via telehealth.14 Patient skill or experience of telerehabilitation was not under consideration here, but may have had a direct effect on clinician perceptions regarding knowledge and beliefs about the appropriateness of telerehabilitation. Likewise, concerns regarding individual patient’s ability and safety to undertake telerehabilitation may remain, despite training and resource support for clinician implementation of telerehabilitation. Accessibility and safety to perform physical training tasks in a remote setting is an acknowledged challenge of telehealth services in comparison to traditional face-to-face interventions.15 Although our brief intervention incorporated strategies for assessing patient and environment suitability and safety for telerehabilitation, specific competence and confidence in this was not assessed and may represent an area of future need so as to support changes in both clinician behavior and perception. That this study was undertaken in rapidly changing landscape of the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia may also have affected the effectiveness of this brief intervention. In health care professionals in particular, the COVID-19 pandemic has created feelings of wariness and uncertainty, as well as workplace, personal, and societal stress.16 It is possible that at another time, in another setting, a similar brief intervention to support the implementation of telerehabilitation may demonstrate greater effectiveness; conversely, the wider effects of the COVID-19 pandemic need to be taken into account when devising implementation strategies to be employed at this time.

A brief intervention, delivered remotely to support community-based therapists to implement telerehabilitation during the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic was well received by clinicians, achieved modest changes to clinical practice, but resulted in limited change in perceived barriers and enablers to telerehabilitation implementation. Greater time may be required to ascertain the sustainability of a brief implementation strategy, along with consideration of pandemic-related stressors.

Suppliers

-

a.

Videoconferencing software; Zoom Video Communications.

-

b.

IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26.0; IBM Corp.

Footnotes

Narelle S. Cox is the holder of a National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship (GNT1119970). Natasha A. Lannin received a Future Leader fellowship from the National Heart Foundation of Australia (GNT102055).

References

- 1.Humphreys J., Schoenherr L., Elia G., et al. Rapid implementation of inpatient telepalliative medicine consultations during COVID-19 pandemic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e54–e59. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2016. Global diffusion of eHealth: making universal health coverage achievable: report of the third global survey on eHealth. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reeves J.J., Hollandsworth H.M., Torriani F.J., et al. Rapid response to COVID-19: health informatics support for outbreak management in an academic health system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27:853–859. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peretti A., Amenta F., Tayebati S.K., Nittari G., Mahdi S.S. Telerehabilitation: review of the state-of-the-art and areas of application. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017;4:e7. doi: 10.2196/rehab.7511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michie S., Johnston M., Abraham C., Lawton R., Parker D., Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Safety Health Care. 2005;14:26–33. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atkins L., Francis J., Islam R., et al. A guide to using the theoretical domains framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017;12:77. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas S., Mackintosh S. Use of the theoretical domains framework to develop an intervention to improve physical therapist management of the risk of falls after discharge. Phys Ther. 2014;94:1660–1675. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curran G., Bauer M., Mittman B., Pyne J., Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50:217–226. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seward K., Wolfenden L., Wiggers J., et al. Measuring implementation behaviour of menu guidelines in the childcare setting: confirmatory factor analysis of a theoretical domains framework questionnaire (TDFQ) Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14:45. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0499-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michie S., Johnston M., Francis J., Hardeman W., Eccles M. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol. 2008;57:660–680. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cane J., O'Connor D., Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inskip J.A., Lauscher H.N., Li L.C., et al. Patient and health care professional perspectives on using telehealth to deliver pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis. 2017;15:71–80. doi: 10.1177/1479972317709643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varsi C., Solberg Nes L., Kristjansdottir O.B., et al. Implementation strategies to enhance the implementation of ehealth programs for patients with chronic illnesses: realist systematic. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e14255. doi: 10.2196/14255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polgar O., Aljishi M., Barker R.E., et al. Digital habits of PR service-users: implications for home-based interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chron Respir Dis. 2020;17 doi: 10.1177/1479973120936685. 1479973120936685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holland A.E., Malaguti C., Hoffman M., et al. Home-based or remote exercise testing in chronic respiratory disease, during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: a rapid review. Chron Respir Dis. 2020;17 doi: 10.1177/1479973120952418. 1479973120952418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Hage W., Hingray C., Lemogne C., et al. [Health professionals facing the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: what are the mental health risks?] [French] Encephale. 2020;46:S73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]