Summary

Background

Tralokinumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that specifically neutralizes interleukin‐13, a key driver of atopic dermatitis (AD).

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of tralokinumab in combination with topical corticosteroids (TCS) in patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD who were candidates for systemic therapy.

Methods

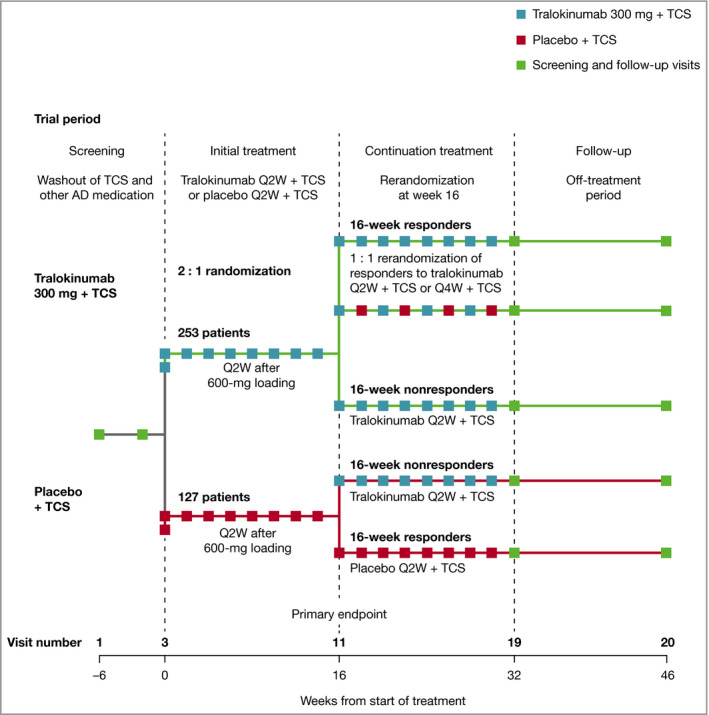

This was a double‐blind, placebo plus TCS controlled phase III trial. Patients were randomized 2 : 1 to subcutaneous tralokinumab 300 mg or placebo every 2 weeks (Q2W) with TCS as needed over 16 weeks. Patients who achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0/1 and/or 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI 75) at week 16 with tralokinumab were rerandomized 1 : 1 to tralokinumab Q2W or every 4 weeks (Q4W), with TCS as needed, for another 16 weeks.

Results

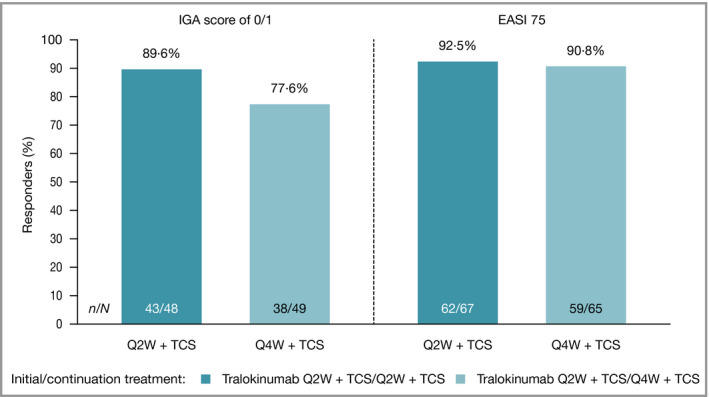

At week 16, more patients treated with tralokinumab than with placebo achieved IGA 0/1: 38·9% vs. 26·2% [difference (95% confidence interval): 12·4% (2·9–21·9); P = 0·015] and EASI 75: 56·0% vs. 35·7% [20·2% (9·8–30·6); P < 0·001]. Of the patients who were tralokinumab responders at week 16, 89·6% and 92·5% of those treated with tralokinumab Q2W and 77·6% and 90·8% treated with tralokinumab Q4W maintained an IGA 0/1 and EASI 75 response at week 32, respectively. Among patients who did not achieve IGA 0/1 and EASI 75 with tralokinumab Q2W at 16 weeks, 30·5% and 55·8% achieved these endpoints, respectively, at week 32. The overall incidence of adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Conclusions

Tralokinumab 300 mg in combination with TCS as needed was effective and well tolerated in patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD.

Short abstract

What is already known about this topic?

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic interleukin (IL)‐13‐mediated disease.

In clinical practice, biologics are commonly initiated as add‐on therapy to topical corticosteroids (TCS).

Tralokinumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that binds specifically to the IL‐13 cytokine with high affinity, thereby preventing receptor interaction and subsequent downstream signalling.

Tralokinumab combined with TCS showed early and sustained efficacy and safety in a 12‐week, phase IIb trial in moderate‐to‐severe AD.

What does this study add?

This is the first phase III trial evaluating a targeted anti‐IL‐13 biologic in combination with TCS.

These data demonstrate that tralokinumab plus TCS can achieve significant improvements in AD signs and symptoms and quality of life, as well as exert a steroid‐sparing effect.

Response with tralokinumab in combination with TCS was maintained over 32 weeks.

Tralokinumab may be considered a targeted biological treatment option for patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD.

Linked Comment: Morra and Drucker. Br J Dermatol 2021; 184:386–387.

Plain language summary available online

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disease 1 , 2 characterized by intense itch and recurrent eczematous skin lesions and associated with sleep disturbance, anxiety, depression and work absenteeism. 1 , 2

Depending on severity, treatment guidelines recommend topical corticosteroids (TCS) as first‐line pharmacological intervention combined with general skin care and trigger avoidance. 3 However, topical anti‐inflammatory treatment is often insufficient to achieve disease control in patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD, 4 and systemic therapy is needed. 5

Interleukin (IL)‐13 is a key driver of underlying inflammation in AD, leading to skin barrier dysfunction, immune dysregulation and, ultimately, chronic type 2 inflammation. 6 , 7 IL‐13 is overexpressed in lesional and nonlesional AD skin, 8 , 9 with expression increasing with progression from the acute to the chronic disease stage. 10 Furthermore, increased expression of IL‐13 in the skin correlates with AD severity. 9 , 11

Currently, the anti‐IL‐4 receptor α antibody dupilumab, which blocks both IL‐4 and IL‐13 signalling, is the only biologic approved for patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD inadequately controlled by TCS 12 , 13 and is recommended as an alternative to systemic immunosuppressive treatment, where available. 4 , 14 Unlike IL‐13, IL‐4 is found at low concentration levels in AD skin. 15 Due to limited alternative therapies for AD, there remains a significant unmet need for additional long‐term targeted systemic or biological therapies with durable efficacy and improved safety profiles.

Tralokinumab is a fully human immunoglobulin G4 monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to the IL‐13 cytokine with high affinity, preventing interaction with the IL‐13 receptor and subsequent downstream IL‐13 signalling, thus inhibiting its proinflammatory activity. 15 , 16 , 17 Real‐world data in AD suggest that systemic therapies such as immunosuppressants or biologics are most commonly initiated as an add‐on to TCS. 18 , 19 Tralokinumab in combination with TCS improved AD severity, symptoms and health‐related quality of life in adult patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD in a recent phase IIb trial. 20 ECZTRA 3 (NCT03363854) provides the results of the first phase III trial of an IL‐13 inhibitor in combination with TCS for moderate‐to‐severe AD (see https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03363854 for the full trial protocol); the phase III ECZTRA 1 (NCT03131648) and ECZTRA 2 (NCT03160885) studies assessed tralokinumab as monotherapy.

The objective of the pivotal ECZTRA 3 trial was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of tralokinumab in comparison with placebo at week 16, both in combination with TCS as needed. Maintenance of tralokinumab efficacy in two different dosing regimens was evaluated up to week 32 in adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD.

Patients and methods

Study design and oversight

This was a double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled 32‐week trial conducted across 63 sites in Europe and North America (listed in Study Investigators S1; see Supporting Information).

Following a 2–6‐week screening period [length of washout required was based on prior medications (Methods S1; see Supporting Information)], patients were randomized 2 : 1 to subcutaneous tralokinumab 300 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W) in combination with TCS as needed, herein referred to as tralokinumab, or placebo Q2W in combination with TCS as needed, herein referred to as placebo, and received 600 mg of tralokinumab or placebo (loading dose) on day 0 (Figure 1). Randomization was performed using a computer‐generated randomization schedule stratified by region (Europe and North America) and baseline disease severity [Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 3/4]. Treatment allocation was blinded to patients and investigators (Methods S1; see Supporting Information). Patients who achieved the clinical response criteria with tralokinumab [IGA score of 0/1 or 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI 75) at week 16], were rerandomized 1 : 1 to tralokinumab Q2W or every 4 weeks (Q4W). Patients who achieved the clinical response criteria with placebo continued to receive placebo (Q2W) to maintain blinding of the study. Patients not achieving the clinical response criteria (from the tralokinumab and placebo groups) received tralokinumab Q2W plus TCS as needed from week 16. All patients had a final safety follow‐up 16 weeks after the last dose of study medication, unless transferred to the long‐term ECZTEND trial (NCT03587805).

Figure 1.

Trial design. Clinical response is defined as patients achieving Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0/1 or at least 75% reduction in the Eczema Area and Severity Index. AD, atopic dermatitis; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

All patients were instructed to apply a thin layer of the supplied TCS as needed, once daily to areas with active lesions [mometasone furoate 0·1% cream; Europe class 3 (potent); US class 4 (mid‐strength), provided free of charge in kit sizes of 180–200 g Q2W]. TCS use was monitored continually for safety and appropriateness and discontinued gradually when control was achieved. Patients were instructed to return used and unused tubes at each trial visit to allow measurement of the amount of TCS used. Patients were instructed to apply an emollient twice daily (or more as needed) for at least 14 days before randomization and throughout the trial (including safety follow‐up). Emollient was to be applied to lesional skin only when the TCS was not applied. Rescue treatment (topical and systemic medications) was permitted to control intolerable AD symptoms at the discretion of the investigator.

This trial was sponsored by LEO Pharma and was conducted in accordance with ethical principles derived from the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and approved by the local institutional review board or independent ethics committee of each institution. All patients provided signed written informed consent. Patients were enrolled from 19 March 2018 to 14 November 2018.

Study population

Patients were ≥ 18 years of age, with a diagnosis of AD (as defined by Hanifin and Rajka criteria) 21 for ≥ 1 year and an inadequate response to topical medications or documented systemic treatment for AD in the past year. Patients were required to have an EASI score ≥ 12 at screening and ≥ 16 at baseline, an IGA score of ≥ 3 and AD involvement of ≥ 10% of body surface area (BSA) at screening and baseline, and worst daily pruritus Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) average score of ≥ 4 during the week prior to baseline.

Efficacy outcomes

Primary endpoints were IGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) and EASI 75 at week 16. Key secondary endpoints included in the testing hierarchy were SCORing AD (SCORAD), weekly average of worst daily pruritus NRS ≥ 4 and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores, all measuring change from baseline to week 16 (Figure S1; see Supporting Information). Additional secondary endpoints included the proportion of patients achieving 50% or 90% improvement in EASI (EASI 50 and EASI 90) or improvement of DLQI ≥ 4 points and change in EASI, Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure, worst daily pruritus and TCS use (assuming no TCS used from nonreturned tubes). Maintenance endpoints (for tralokinumab plus TCS Q2W and tralokinumab plus TCS Q4W at week 32) were IGA score of 0/1 among patients with IGA score of 0/1 at week 16 and EASI 75 among patients with EASI 75 at week 16.

Safety assessments

Clinical laboratory tests, vital signs and other safety assessments were performed at baseline and assessed at each visit. The incidence and description of all adverse events (AEs) were recorded.

Statistical analyses

A sample size of 369 patients randomized 2 : 1 was estimated to provide 90% power to detect a difference between tralokinumab and placebo Q2W with a two‐sided 5% significance level, assuming response rates of 30% and 15%, respectively, for an IGA score of 0/1 at week 16 and a nominal power > 99·9% to detect a difference, assuming response rates of 40% and 15%, respectively, for EASI 75 at week 16. The combined power for demonstrating a statistically significant difference for both endpoints was effectively also 90%, with a sample size of 369 patients, even when assuming no correlation between the primary endpoints.

To control the overall type 1 error rate at a 5% significance level, a prespecified testing hierarchy was used for the primary and key secondary endpoints for the initial treatment period (Methods S1 and Figure S1; see Supporting Information).

A range of statistical analyses were prespecified within the estimand framework as per the ICH (International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use) E9(R1) guidelines, incorporating two main types of intercurrent events that could influence the effect attributable to the treatments (initiation of rescue medication and permanent discontinuation of treatment).

For binary endpoints, a ‘composite’ estimand was specified as the primary approach, assessing the treatment difference in response rates achieved after 16 weeks without rescue medication, regardless of treatment discontinuation. Patients who received rescue medication were considered to be nonresponders and missing data were imputed as nonresponse. The difference in response rates between treatment groups was analysed using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by region (Europe and North America) and baseline IGA (IGA score of 3/4).

For the continuous endpoints, a ‘hypothetical’ estimand was applied, assessing the treatment difference in change from baseline to week 16 as if all patients adhered to the treatment regimen and no rescue medication was made available. Data collected after permanent discontinuation or initiation of rescue medication were excluded from the analysis and endpoints were analysed using a linear mixed model for repeated measurements (MMRM). Details on model, sensitivity and secondary and tertiary estimand analyses for binary and continuous endpoints are provided in Methods S1 (see Supporting Information).

IGA scores of 0/1 at week 32 among patients with IGA scores of 0/1 at week 16 and EASI 75 at week 32 among patients with EASI 75 at week 16 were summarized descriptively by treatment group.

For patients initially randomized to tralokinumab, the percentage change in EASI and change in DLQI over 32 weeks and by treatment groups defined by the continuation treatment period were analysed in the exploratory analyses using a linear MMRM model.

Safety analyses were performed using the safety analysis set, with initial treatment and continuation treatment reported separately.

Results

Patients

In total, 380 patients were randomized in the initial treatment period: 253 to tralokinumab and 127 to placebo (Figure S2a; see Supporting Information).

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were balanced across treatment groups, with approximately half of the patients having severe disease (IGA score of 4) at baseline; median duration of AD was 26·0 years, median EASI score was 25·5 and median BSA involvement was 41% (Table 1). All patients had received prior therapy, with almost all receiving TCS (98·2%) and 61·6% having used systemic steroids (Table S1; see Supporting Information).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of randomized patients at baseline

| All randomized (N = 380) |

Placebo Q2W + TCS (N = 127) |

Tralokinumab Q2W + TCS (N = 253) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (IQR) | 36·0 (27·0–51·0) | 34·0 (24·0–50·0) | 37·0 (28·0–52·0) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 209 (55·0) | 84 (66·1) | 125 (49·4) |

| Female | 171 (45·0) | 43 (33·9) | 128 (50·6) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 288 (75·8) | 85 (66·9) | 203 (80·2) |

| Black or African American | 35 (9·2) | 12 (9·4) | 23 (9·1) |

| Asian | 41 (10·8) | 24 (18·9) | 17 (6·7) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 2 (0·5) | 1 (0·8) | 1 (0·4) |

| Other | 14 (3·7) | 5 (3·9) | 9 (3·6) |

| Median duration of AD, years (IQR) |

N = 379 26·0 (17·0–39·0) |

N = 126 26·0 (18·0–39·0) |

N = 253 27·0 (17·0–39·0) |

| Median BSA involvement, % (IQR) | 41·0 (28·0–69·5) | 40·0 (26·0–74·0) | 41·0 (30·0–63·0) |

| IGA, n (%) | |||

| Moderate (IGA score of 3) | 202 (53·2) | 66 (52·0) | 136 (53·8) |

| Severe (IGA score of 4) | 176 (46·3) | 60 (47·2) | 116 (45·8) |

| Missinga | 2 (0·5) | 1 (0·8) | 1 (0·4) |

| Median EASI score (IQR) |

N = 378 25·5 (19·2–37·1) |

N = 126 26·5 (19·9–39·3) |

N = 252 24·7 (18·4–35·9) |

| Median SCORAD total score (IQR) |

N = 378 66·5 (57·9–77·6) |

N = 126 67·9 (59·4–79·0) |

N = 252 66·2 (57·6–76·3) |

| Median DLQI score (IQR) |

N = 375 18·0 (12·0–23·0) |

N = 125 18·0 (12·0–23·0) |

N = 250 18·0 (12·0–23·0) |

| Median weekly average of worst daily pruritus NRS score (IQR) |

N = 377 8·0 (6·6–8·9) |

N = 126 8·0 (7·0–9·0) |

N = 251 8·0 (6·6–8·7) |

| Median POEM score (IQR) |

N = 374 23·0 (20·0–27·0) |

N = 124 24·0 (20·0–27·0) |

N = 250 23·0 (20·0–26·0) |

| History of allergic conjunctivitis (atopy form), n (%) | |||

| Current | 84 (22·1) | 26 (20·5) | 58 (22·9) |

| Past | 45 (11·8) | 11 (8·7) | 34 (13·4) |

| History of asthma (atopy form), n (%) | |||

| Current | 177 (46·6) | 58 (45·7) | 119 (47·0) |

| Past | 47 (12·4) | 19 (15·0) | 28 (11·1) |

| History of atopic keratoconjunctivitis (atopy form), n (%) | |||

| Current | 13 (3·4) | 5 (3·9) | 8 (3·2) |

| Past | 6 (1·6) | 4 (3·1) | 2 (0·8) |

| History of food allergy (atopy form), n (%) | |||

| Current | 138 (36·3) | 48 (37·8) | 90 (35·6) |

| Past | 12 (3·2) | 3 (2·4) | 9 (3·6) |

| History of hay fever (atopy form), n (%) | |||

| Current | 210 (55·3) | 69 (54·3) | 141 (55·7) |

| Past | 20 (5·3) | 3 (2·4) | 17 (6·7) |

AD, atopic dermatitis; BSA, body surface area involvement; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA, Investigator’s Global Assessment; IQR, interquartile range; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; POEM, Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure; Q2W, every 2 weeks; SCORAD, SCORing AD; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

aPatients did not receive a treatment dose and were not included in the full analysis set.

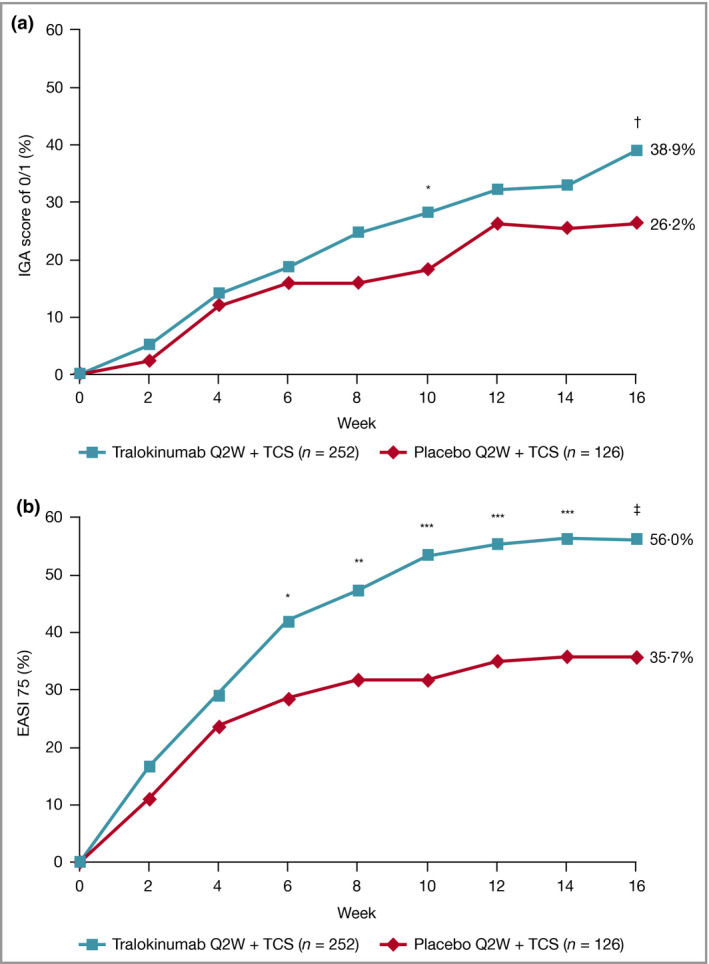

Primary outcomes

At week 16, significantly more patients receiving tralokinumab achieved the primary endpoints. An IGA score of 0/1 was achieved by 38·9% vs. 26·2% [difference (95% confidence interval, CI) 12·4% (2·9–21·9); P = 0·015] and EASI 75 by 56·0% vs. 35·7% [20·2% (9·8–30·6); P < 0·001] for tralokinumab and placebo, respectively (Figure 2 and Table 2; Tables S2 and S3; see Supporting Information). The proportion of IGA 0/1 and EASI 75 responders was higher with tralokinumab at each timepoint than placebo, increasing from treatment initiation to week 16 (Figure 2). Rescue medication use was higher in the placebo group than in the tralokinumab‐treated group (Table S4; see Supporting Information). The sensitivity, secondary and tertiary analyses supported the results of the primary analysis (Table S5; see Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

(a) IGA score of 0/1 and (b) EASI 75 response by visit in the initial treatment period, full analysis set. Patients who received rescue medication were considered nonresponders. Patients with missing data were imputed as nonresponders. The number of patients assessed at each visit can be found in Tables S2 and S3; see Supporting Information.

*P < 0·05 vs. placebo + TCS; **P < 0·01 vs. placebo + TCS; ***P < 0·001 vs. placebo + TCS. Model‐based treatment difference: † P < 0·05 vs. placebo + TCS; ‡ P < 0·001 vs. placebo + TCS. EASI 75, at least 75% reduction in Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA, Investigator’s Global Assessment; Q2W, every 2 weeks; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

Table 2.

Efficacy outcomes for initial treatment period: full analysis set

| Outcome | Placebo Q2W + TCS (N = 126) | Tralokinumab Q2W + TCS (N = 252) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoints | ||

| IGA score of 0/1 at week 16, n (%)a | 33/126 (26·2) | 98/252 (38·9) |

| Difference vs. placebo Q2W + TCS (95% CI)b |

12·4 (2·9–21·9) P = 0·015 |

|

| EASI 75 at week 16, n (%)a | 45/126 (35·7) | 141/252 (56·0) |

| Difference vs. placebo Q2W + TCS (95% CI)b |

20·2 (9·8–30·6) P < 0·001 |

|

| Key secondary endpoints | ||

| Adjusted mean change from baseline in SCORAD score at week 16 ± SEc | –26·8 ± 1·80 | –37·7 ± 1·25 |

| Difference vs. placebo Q2W + TCS (95% CI) |

–10·9 (–15·2 to –6·6) P < 0·001 |

|

| Weekly average of worst daily pruritus NRS reduction ≥ 4 at week 16, n/N (%)a | 43/126 (34·1) | 113/249d (45·4) |

| Difference vs. placebo Q2W + TCS (95% CI)b |

11·3 (0·9–21·6) P = 0·037 |

|

| Adjusted mean change from baseline in DLQI score at week 16 ± SEc | –8·8 ± 0·56 | –11·7 ± 0·39 |

| Difference vs. placebo Q2W + TCS (95% CI) |

–2·9 (–4·3 to –1·6) P < 0·001 |

|

| Additional secondary endpoints | ||

| Adjusted mean change from baseline in weekly average of worst daily pruritus NRS at week 16 ± SEd,e |

N = 100 –2·9 ± 0·21 |

N = 221 –4·1 ± 0·15 |

| Difference vs. placebo Q2W + TCS (95% CI) |

–1·2 (–1·7 to –0·7) P < 0·001 |

|

| DLQI reduction ≥ 4 at week 16, n/N (%)a | 81/123f (65·9) | 207/248f (83·5) |

| Difference vs. placebo Q2W + TCS (95% CI)b |

17·6 (8·0–27·1) P < 0·001 |

|

| Adjusted mean change from baseline in EASI score at week 16 ± SEc |

N = 108 –15·6 ± 0·96 |

N = 229 –21·0 ± 0·67 |

| Difference vs. placebo Q2W + TCS (95% CI) |

–5·4 (–7·7 to –3·1) P < 0·001 |

|

| EASI 50 at week 16, n (%)a | 73/126 (57·9) | 200/252 (79·4) |

| Difference vs. placebo Q2W + TCS (95% CI)b |

21·3 (11·3–31·3) P < 0·001 |

|

| EASI 90 at week 16, n (%)a | 27/126 (21·4) | 83/252 (32·9) |

| Difference vs. placebo Q2W + TCS (95% CI)b |

11·4 (2·1–20·7) P = 0·022 |

|

| Cumulative amount of TCS used at weeks 15–16, adjusted mean ± SEg |

N = 108 193·5 ± 16·7 |

N = 229 134·9 ± 11·7 |

| Difference vs. placebo (95% CI) |

–58·6 (–98·7 to –18·5) P = 0·004 |

|

| Other endpoints | ||

| Adjusted mean change from baseline in SCORAD score at week 2 ± SEc | –16·4 ± 1·33 | –20·6 ± 0·93 |

| Difference vs. placebo Q2W + TCS (95% CI) |

–4·2 (–7·4 to –1·0) P = 0·010 |

|

| Adjusted mean change from baseline in DLQI score at week 2 ± SEc | –7·3 ± 0·53 | –8·9 ± 0·37 |

| Difference vs. Q2W + TCS (95% CI) |

–1·7 (–2·9 to –0·4) P = 0·011 |

|

| Adjusted mean change from baseline in weekly average of worst daily pruritus NRS at week 1 ± SEe |

N = 125 –1·3 ± 0·13 |

N = 248 –1·5 ± 0·09 |

| Difference vs. placebo (95% CI) |

–0·2 (–0·6 to –0·1) P = 0·14 |

|

| Adjusted mean change from baseline in POEM score at week 16 ± SEc | N = 103; –7·8 ± 0·66 | N = 226; –11·8 ± 0·46 |

| Difference vs. placebo Q2W + TCS (95% CI) |

–0·4 (–5·6 to –2·4) P < 0·001 |

CI, confidence interval; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; EASI 50, at least 50% reduction in EASI; EASI 75, at least 75% reduction in EASI; EASI 90, at least 90% reduction in EASI; IGA, Investigator’s Global Assessment; IMP, investigational medicinal product; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; POEM, Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure; Q2W, every 2 weeks; SCORAD, SCORing Atopic Dermatitis; SE, standard error; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

aPatients who received rescue medication were considered nonresponders. Patients with missing data at week 16 were imputed as nonresponders. bMantel–Haenszel risk difference, stratified by region and baseline IGA. cData collected after permanent discontinuation of IMP or initiation of rescue medication not included. Repeated‐measurements model on post‐baseline data: Change = Treatment × Week + Baseline × Week + Region + Baseline IGA. In case of no postbaseline assessments before initiation of rescue medication, the week 2 change is imputed as 0. dBased on patients in full analysis set with a baseline pruritus NRS weekly average of at least 4. eData collected after permanent discontinuation of IMP or initiation of rescue medication not included. Repeated‐measurements model: Change = Treatment × Week + Baseline × Week + Region + Baseline IGA. In the case of no postbaseline assessments before initiation of rescue medication, the week 1 change is imputed as 0. fAnalysis includes only patients with baseline DLQI ≥ 4. gAssuming no TCS was used from the nonreturned tubes. Data collected after permanent discontinuation of IMP or initiation of rescue medication not included. The response variable was the cumulative amount of TCS. Repeated‐measurements model: cumulative TCS amount (g) = Treatment × Week + Region + Baseline IGA.

Key secondary outcomes

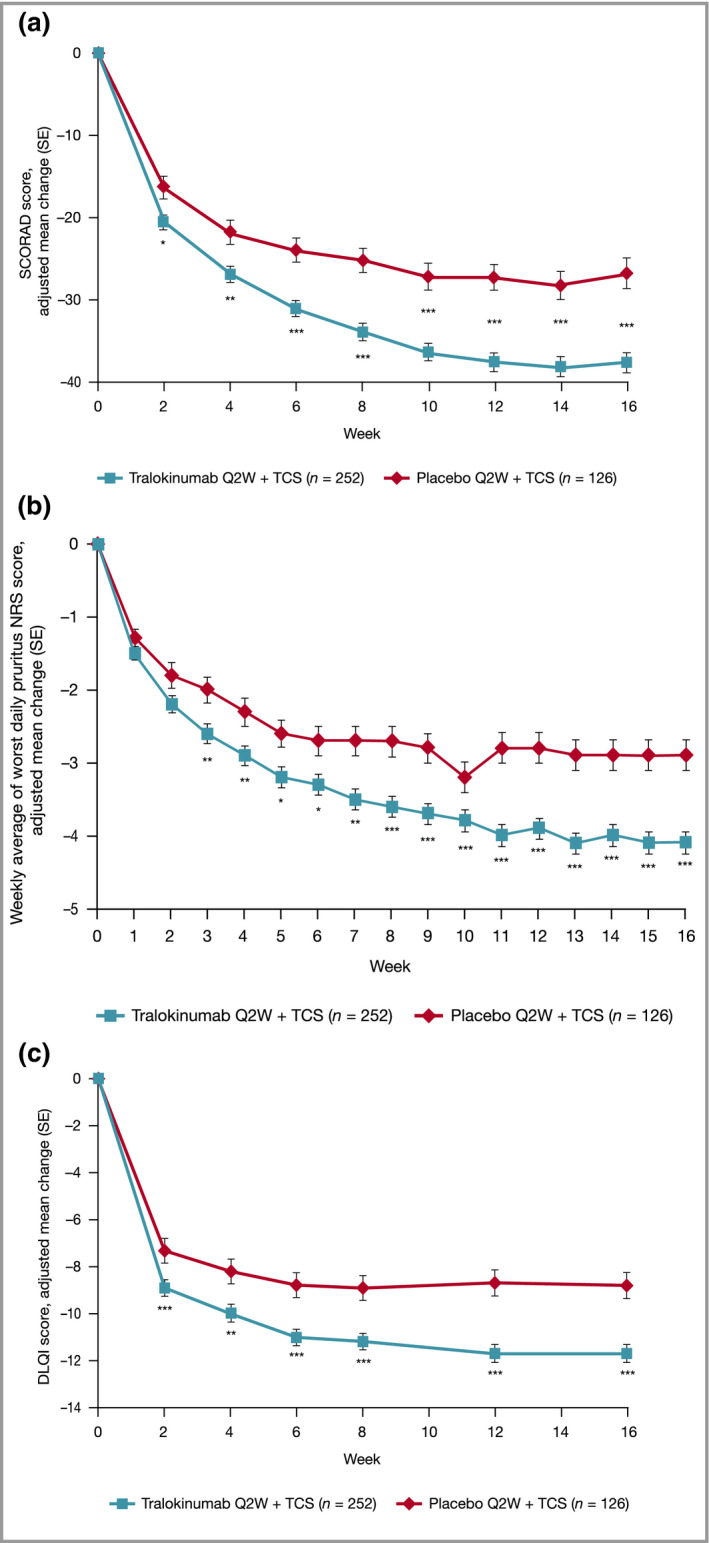

Tralokinumab significantly improved all key secondary endpoints vs. placebo. At week 16, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with tralokinumab vs. those treated with placebo achieved a ≥ 4‐point reduction in weekly average of worst daily pruritus NRS score: 45·4% vs. 34·1% [11·3% (0·9–21·6); P = 0·037] and significant improvements in SCORAD score: –37·7 vs. –26·8 [–10·9 (–15·2 to –6·6); P < 0·001] and total DLQI score: –11·7 vs. –8·8 [–2·9 (–4·3 to –1·6); P < 0·001] (Figure 3 and Table 2; Tables S6–S9; see Supporting Information) The sensitivity, secondary and tertiary analyses supported the results of the primary analyses for all key secondary endpoints (Table S10; see Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

Effect of tralokinumab and placebo treatment on secondary endpoint: (a) change from baseline in SCORAD score by visit; (b) change from baseline in weekly average of worst daily pruritus NRS score; and (c) change from baseline in DLQI score by visit, repeated‐measurements analysis, initial treatment period, full analysis set. Data are adjusted mean change (SE) from repeated‐measurements model. Data collected after permanent discontinuation of investigational medicinal product or initiation of rescue medication not included. The number of patients assessed at each visit can be found in Tables S6–S9; see Supporting Information. In case of no postbaseline assessments before indication of rescue medication, the week 2 (week 1 for NRS) change will be imputed as 0. Repeated‐measurements model: Change = Treatment × Week + Baseline × Week + Region + Baseline Investigator’s Global Assessment. *P < 0·05 vs. placebo + TCS; **P < 0·01 vs. placebo + TCS; ***P < 0·001 vs. placebo + TCS. DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; Q2W, every 2 weeks; SCORAD, SCORing Atopic Dermatitis; SE, standard error; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

Additional secondary outcomes

Differences between tralokinumab and placebo for all other secondary endpoints were also seen (Table 2). At week 16, more patients treated with tralokinumab achieved EASI 50 and EASI 90 (Figure S3; see Supporting Information). A greater reduction in EASI and weekly average of worst daily pruritus NRS was observed in the tralokinumab arm (Table 2). Separation between treatment arms was observed from week 2 for SCORAD, EASI and DLQI (all P < 0·05) (Figure 3 and Table 2).

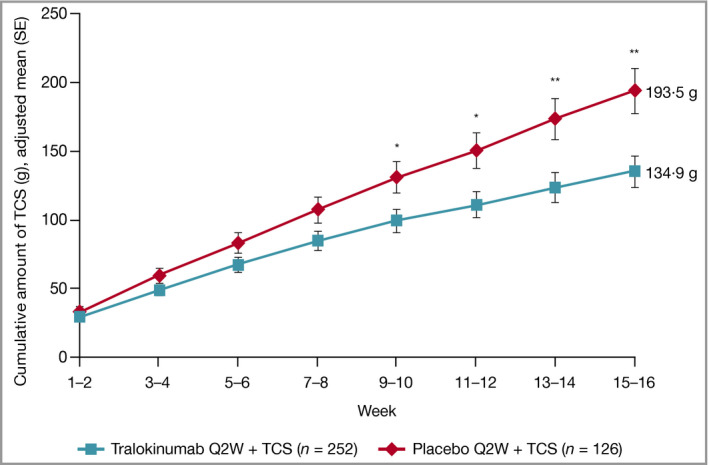

Cumulative TCS use was lower at weeks 15–16 with tralokinumab (P = 0·004) (Figure 4 and Table 2). At weeks 15–16, patients treated with tralokinumab used approximately 50% less of the supplied TCS compared with those treated with placebo (P = 0·002) (Figure S4; see Supporting Information) and 55·3% used no or very limited amounts (0–5 g) of TCS (Figure S5; see Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

Cumulative amount of TCS use by visit and treatment group, assuming no TCS used from the nonreturned tubes, initial treatment period, full analysis set. Data are adjusted mean (SE) from repeated‐measurements model. Data collected after permanent discontinuation of investigational medicinal product or initiation of rescue medication not included. Repeated‐measurements model: TCS cumulative amount (g) = Treatment × Week + Region + Baseline Investigator’s Global Assessment. *P < 0·05 vs. placebo + TCS; **P < 0·01 vs. placebo + TCS. Q2W, every 2 weeks; SE, standard error; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

Maintenance outcomes

At week 16, 141 patients achieved IGA scores of 0/1 and/or EASI 75 with tralokinumab Q2W and 134 were rerandomized to tralokinumab Q2W or Q4W in combination with TCS as needed (Figure S2b; see Supporting Information). At week 32, IGA 0/1 response was maintained without any rescue therapy use in 89·6% (95% CI 77·8–95·5) and 77·6% (64·1–87·0) and EASI 75 in 92·5% (83·7–96·8) and 90·8% (81·3–95·7) with tralokinumab Q2W and Q4W, respectively (Figure 5). The high level of maintained response with tralokinumab Q2W or Q4W was not associated with an increased use of TCS (Figure S6; see Supporting Information).

Figure 5.

IGA score of 0/1 and EASI 75 response at week 32, patients in the continuation treatment analysis set with IGA score of 0/1 (left) and EASI 75 (right) at week 16 achieved without rescue medication after initial randomization to tralokinumab. A responder was defined as having an IGA score of 0/1 or EASI 75. N = number of individuals being IGA 0/1 (left) and EASI 75 (right) responders at week 16 and initially treated with tralokinumab. n = number of responders at week 32. Patients who received rescue medication were considered nonresponders. Patients with missing data at week 32 were imputed as nonresponders. EASI 75, at least 75% reduction in Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA, Investigator’s Global Assessment; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

Changes from baseline in EASI and DLQI for patients treated with tralokinumab over the 32‐week treatment period are shown in Figure S7 (see Supporting Information). Of the patients who achieved EASI 75 and/or IGA 0/1 responses at week 16 on tralokinumab Q2W, approximately 60% were also EASI 90 responders, increasing with continued treatment to 72·5% and 63·8% for Q2W and Q4W dosing at week 32, respectively (Table S11; see Supporting Information). Patients who did not achieve EASI 75 and IGA 0/1 response at week 16 continued to improve with tralokinumab Q2W, with 30·5% (22·2–40·4) and 55·8% (45·8–65·4) achieving an IGA score of 0/1 and EASI 75 at week 32, respectively. Improvements in DLQI achieved at week 16 were maintained at week 32.

Safety

In the initial treatment period, the overall frequency and severity of AEs were comparable between tralokinumab and placebo (Table 3). Overall, 180 (71·4%) and 84 (66·7%) patients in the tralokinumab and placebo groups experienced AEs. The majority of AEs were nonserious and mild or moderate in severity, with most resolved or resolving by the end of the initial treatment period. Of the most frequently reported AEs (≥ 5% in any treatment group), viral upper respiratory tract infection, conjunctivitis, headache, upper respiratory tract infection and injection‐site reaction were reported more frequently with tralokinumab vs. placebo (Table 3). Six patients permanently discontinued treatment with tralokinumab due to eight AEs, none of which was serious (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of adverse events (AEs) and AEs of special interest (AESIs) in the 16‐week initial treatment period for the safety analysis seta

|

Placebo Q2W + TCS (N = 126; PYE = 37·94) |

Tralokinumab Q2W + TCS (N = 252; PYE = 75·03) |

|

|---|---|---|

| AE or SAE, n (%), R | ||

| At least one AE | 84 (66·7), 485·0 | 180 (71·4), 671·7 |

| At least one SAE | 4 (3·2), 10·54 | 2 (0·8), 2·67 |

| Severity | ||

| Mild | 69 (54·8), 347·9 | 157 (62·3), 511·8 |

| Moderate | 30 (23·8), 110·7 | 66 (26·2), 150·6 |

| Severe | 7 (5·6), 26·36 | 7 (2·8), 9·33 |

| Leading to discontinuation of IMP | 1 (0·8), 2·64 | 6 (2·4), 10·66 |

| Outcome | ||

| Not recovered/not resolved | 13 (10·3), 47·4 | 48 (19·0), 80·0 |

| Recovering/resolving | 7 (5·6), 23·7 | 13 (5·2), 20·0 |

| Recovered/resolved | 78 (61·9), 413·8 | 167 (66·3), 563·7 |

| Recovered/resolved with sequelae | 0 | 3 (1·2), 4·0 |

| Frequent AEs (≥ 5% in any treatment group)b | ||

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection | 14 (11·1), 47·44 | 49 (19·4), 85·29 |

| Conjunctivitis | 4 (3·2), 10·54 | 28 (11·1), 42·65 |

| Headache | 6 (4·8), 23·72 | 22 (8·7), 34·65 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 6 (4·8), 18·45 | 19 (7·5), 27·99 |

| Injection‐site reaction | 0 | 17 (6·7), 39·98 |

| Dermatitis atopic | 10 (7·9), 31·63 | 6 (2·4), 10·66 |

| AESI: eye disorders | 7 (5·6), 18·45 | 34 (13·5), 51·98 |

| AESI Conjunctivitisc | 7 (5·6), 18·45 | 33 (13·1), 50·64 |

| AESI Keratoconjunctivitis | 0 | 1 (0·4), 1·33 |

| AESI Keratitis | 0 | 0 |

| AESI: skin infections requiring systemic treatment | 7 (5·6), 23·72 | 4 (1·6), 5·33 |

| AESI: eczema herpeticum | 1 (0·8), 2·64 | 1 (0·4), 1·33 |

| AESI: malignancies diagnosed after randomization | 0 | 0 |

IMP, investigational medicinal product; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; n, number of patients in analysis set; N, number of patients with one or more events; PYE, patient‐years of exposure; Q2W, every 2 weeks; R, rate (number of AEs divided by PYE multiplied by 100); SAE, serious AE; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

aAEs collected during the exposure time in the initial treatment period are shown. bPreferred term according to MedDRA 20·0. cIncludes the preferred terms conjunctivitis, conjunctivitis allergic and conjunctivitis viral.

Conjunctivitis as an AE of special interest (AESI) was reported more frequently with tralokinumab than placebo in the initial treatment period (Table 3); all were mild or moderate in severity and most recovered by the end of the initial treatment period, with one patient discontinuing tralokinumab due to conjunctivitis. Skin infections requiring systemic treatment occurred less frequently in patients treated with tralokinumab Q2W vs. placebo Q2W (Table 3). There was no difference in the frequency of events of eczema herpeticum (Table 3).

In the continuation treatment period, no increase in the frequency of AEs among patients treated with tralokinumab plus TCS was observed (Table 4). The pattern of events was comparable to tralokinumab Q2W from the initial treatment period. AEs were more frequently reported in the tralokinumab Q2W group vs. the tralokinumab Q4W group (Table 4). Two AESIs related to malignancies diagnosed after randomization were reported, both in the continuation treatment period (one nonserious prostate cancer in one patient treated with tralokinumab and one serious invasive ductal breast carcinoma in one patient treated with placebo Q2W). Four patients permanently discontinued treatment with tralokinumab (Table 4); AD led to two discontinuations; both incidences were nonserious and moderate to severe in severity. Two patients discontinued due to prostate cancer and eczema herpeticum.

Table 4.

Summary of adverse events (AEs) and AEs of special interest (AESIs) during the continuation treatment period for the safety analysis set

| From week 16 | Placebo treated | Tralokinumab treated | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responders | Nonresponders | Responders | Nonresponders | ||

| Continuation treatment period (at week 32)a |

Placebo Q2W + TCS (N = 41; PYE = 12·25) |

Tralokinumab Q2W + TCS (N = 79; PYE = 22·99) |

Tralokinumab Q2W + TCS (N = 69; PYE = 21·46) |

Tralokinumab Q4W + TCS (N = 69; PYE = 20·7) |

Tralokinumab Q2W + TCS (N = 95; PYE = 28·28) |

| AE or SAE, n (%), R | |||||

| At least one AE | 26 (63·4), 359·3 | 55 (69·6), 552·5 | 48 (69·6), 540·5 | 41 (59·4), 439·6 | 62 (65·3), 654·2 |

| At least one SAE | 1 (2·4), 8·17 | 0 | 3 (4·3), 18·64 | 0 | 2 (2·1), 7·07 |

| Severity | |||||

| Mild | 17 (41·5), 236·8 | 41 (51·9), 348·0 | 41 (59·4), 419·3 | 35 (50·7), 347·8 | 51 (53·7), 477·4 |

| Moderate | 12 (29·3), 122·5 | 25 (31·6), 195·8 | 16 (23·2), 111·8 | 12 (17·4), 91·78 | 30 (31·6), 173·3 |

| Severe | 0 | 2 (2·5), 8·70 | 2 (2·9), 9·32 | 0 | 1 (1·1), 3·54 |

| Leading to discontinuation of IMP | 1 (2·4), 8·17 | 2 (2·5), 8·70 | 0 | 1 (1·4), 4·83 | 1 (1·1), 3·54 |

| Outcome | |||||

| Not recovered/not resolved | 5 (12·2), 40·8 | 15 (19·0), 104·4 | 9 (13·0), 60·6 | 13 (18·8), 96·6 | 19 (20·0), 102·6 |

| Recovering/resolving | 2 (4·9), 16·3 | 7 (8·9), 30·5 | 5 (7·2), 23·3 | 1 (1·4), 4·8 | 5 (5·3), 21·2 |

| Recovered/resolved | 22 (53·7), 302·1 | 46 (58·2), 400·2 | 43 (62·3), 451·9 | 35 (50·7), 328·5 | 56 (58·9), 509·2 |

| Recovered/resolved with sequelae | 0 | 1 (1·3), 4·35 | 0 | 1 (1·4), 4·8 | 2 (2·1), 7·1 |

| Frequent AEs (≥ 5% in any treatment group)b | |||||

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection | 7 (17·1), 65·32 | 15 (19·0), 65·25 | 12 (17·4), 60·57 | 9 (13·0), 48·30 | 20 (21·1), 99·01 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 2 (4·9), 16·33 | 3 (3·8), 13·05 | 7 (10·1), 37·27 | 3 (4·3), 14·49 | 6 (6·3), 24·75 |

| Oral herpes | 1 (2·4), 8·17 | 2 (2·5), 8·70 | 3 (4·3), 13·98 | 4 (5·8), 19·32 | 4 (4·2), 17·68 |

| Injection‐site reaction | 0 | 2 (2·5), 8·70 | 5 (7·2), 65·23 | 4 (5·8), 43·47 | 5 (5·3), 17·68 |

| Dermatitis atopic | 2 (4·9), 16·33 | 6 (7·6), 26·10 | 1 (1·4), 4·66 | 1 (1·4), 4·83 | 8 (8·4), 28·29 |

| Headache | 1 (2·4), 8·17 | 2 (2·5), 8·70 | 2 (2·9), 9·32 | 5 (7·2), 24·15 | 7 (7·4), 24·75 |

| Nausea | 0 | 1 (1·3), 4·35 | 3 (4·3), 13·98 | 4 (5·8), 19·32 | 3 (3·2), 14·14 |

| AESIs | |||||

| Eye disorders | 2 (4·9), 16·33 | 6 (7·6), 34·80 | 3 (4·3), 13·98 | 1 (1·4), 4·83 | 4 (4·2), 14·14 |

| Conjunctivitisc | 1 (2·4), 8·17 | 6 (7·6), 30·45 | 3 (4·3), 13·98 | 1 (1·4), 4·83 | 4 (4·2), 14·14 |

| Keratoconjunctivitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Keratitis | 1 (2·4), 8·17 | 1 (1·3), 4·35 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin infections requiring systemic treatment | 0 | 2 (2·5), 8·70 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1·1), 3·54 |

| Eczema herpeticum | 0 | 1 (1·3), 8·70 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1·1), 3·54 |

| Malignancies diagnosed after randomization | 1 (2·4), 8·17 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1·4), 4·83 | 0 |

IMP, investigational medicinal product; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; n, number of patients in analysis set; N, number of patients with one or more events; PYE, patient‐years of exposure; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks; R, rate (number of AEs divided by PYE multiplied by 100); SAE, serious AE; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

aAEs collected during the exposure time in the continuation treatment period are shown. Responders and nonresponders are presented as treated. A responder was defined as having an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0/1 or at least 75% reduction in Eczema Area and Severity Index at week 16. bPreferred term according to MedDRA 20·0. cincludes the preferred terms conjunctivitis, conjunctivitis allergic and conjunctivitis viral.

Thirteen serious AEs (SAEs) were reported during the entire treatment period, six in the initial and seven in the continuation treatment periods (data not shown), with no marked differences between the treatment groups of each treatment period and between treatment periods and no clustering with respect to specific system organ class or event types. Two SAEs were reported during follow‐up, with one nontreatment‐emergent SAE and one SAE reported after database lock. There were no noteworthy differences between treatment groups in laboratory values, vital signs and electrocardiographic assessments. More patients treated with tralokinumab experienced increased eosinophil levels (mean count 0·69 × 109 L–1) during the initial treatment period, which was maintained during the continuation treatment period. The safety profile of patients with increased eosinophil counts was comparable with the overall trial population.

Discussion

Tralokinumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody developed to specifically target IL‐13, a key driver of inflammation in AD. 7 Here we report the first phase III results with an anti‐IL‐13 biologic used in combination with TCS as needed in patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD. The objective of the initial 16‐week period was to demonstrate the efficacy of tralokinumab vs. placebo. At week 16, tralokinumab 300 mg Q2W plus TCS was more effective than placebo Q2W plus TCS at all primary and secondary endpoints. Over one‐third of patients receiving tralokinumab achieved clear or almost clear skin at week 16, with over half achieving EASI 75. The proportion of IGA 0/1 and EASI 75 responders was higher with tralokinumab Q2W vs. placebo, irrespective of disease severity, history of atopic disease, sex and age, with a higher placebo response observed in patients with moderate disease.

The objective of the 16‐week maintenance period was to demonstrate maintained response with two different dosing options, tralokinumab Q2W or Q4W plus TCS as needed. Both dosing options demonstrated a high level of maintained response at week 32. Notably, there was no increase in TCS use with tralokinumab dosing Q4W. In the 52‐week ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2 monotherapy trials, 22 less frequent Q4W dosing was also shown to maintain long‐term response (over 36 weeks without any TCS use) in 39–45% of patients who had achieved clear or almost clear skin on initial tralokinumab Q2W dosing. The proportion of patients who maintained their response was higher in ECZTRA 3, a study that more closely resembles the ‘real‐world’ clinical setting, compared with ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2; however, the trials are not readily comparable due to differences in their study design. The use of TCS in this study may have contributed to the higher maintained response; however, the overall use of TCS was low. Taken together, these results suggest that tralokinumab may offer the possibility of dosing Q4W in some patients who have achieved clear or almost clear skin with initial Q2W dosing.

In patients who did not achieve IGA scores of 0/1 or EASI 75 at week 16, improvements continued over time with tralokinumab treatment, indicating that patients may benefit from continued treatment beyond week 16.

The majority of patients used no or very limited amounts of TCS at week 16 with tralokinumab vs. placebo, and used lower amounts of rescue medication, further demonstrating the effectiveness of tralokinumab. The higher use of TCS with placebo vs. tralokinumab suggests that the high placebo response could be attributed to increased TCS use. The reduction in TCS usage with tralokinumab is important as this trial is representative of how biological treatments are likely to be used in the ‘real‐world’ clinical setting, i.e. used in combination with TCS on lesional skin as needed. 18 , 19

Overall, tralokinumab in combination with TCS as needed was well tolerated, with an overall frequency and severity of AEs comparable with placebo over 32 weeks. The incidence of SAEs was low, with most events not being related to treatment. The incidence of eye disorders was collected as AESIs and an increased incidence of mild‐to‐moderate conjunctivitis (11·1%) was seen in the patients treated with tralokinumab plus TCS compared with the phase IIb trial (2·6%). 20 This could be attributed partly to an increased focus on conjunctivitis. Further studies are required to gain a better understanding of this AE. Notably, fewer skin infections requiring systemic treatment occurred with tralokinumab vs. placebo Q2W, which could be related to a rebalanced skin microbiome. In the phase IIb combination study, as well as in the ECZTRA 1 monotherapy trial, 22 tralokinumab treatment was associated with a reduction in Staphylococcus aureus colonization. 23

Limitations of this trial included the lack of a comparable placebo group in the continuation treatment period, preventing the ability to estimate the effects of tralokinumab as maintenance therapy compared with placebo. For ethical reasons, it was recommended that the double‐blind placebo design was limited to the initial treatment period. In addition, this study did not address the comparative efficacy of tralokinumab vs. oral immunosuppressants or other biologics in moderate‐to‐severe AD. However, the provision and continued use of topical treatments on active lesions as needed is part of standard care and allows a better understanding of the investigational product in a real‐world setting.

In conclusion, tralokinumab used concomitantly with TCS was effective and well tolerated in patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD with a favourable benefit–risk profile. Findings from this study support those from a smaller dose‐ranging phase IIb trial, 20 provide further evidence that IL‐13 is a key cytokine in the pathogenesis of AD and corroborate results from the ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2 tralokinumab monotherapy trials, suggesting that tralokinumab may be considered a targeted biological treatment option for patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD whose disease is not controlled by topical therapies.

Author Contribution

Jonathan I Silverberg: Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Darryl Toth: Data curation (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). T. Bieber: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Methodology (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Andrew F. Alexis: Data curation (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Boni Elewski: Data curation (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Andrew Pink: Data curation (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). DirkJan Hijnen: Data curation (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Thomas Nedergaard Jensen: Conceptualization (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Methodology (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Bo Bang: Conceptualization (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Methodology (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Christina Olsen: Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Azra Kurbasic: Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Stephan Weidinger: Data curation (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal).

Supporting information

Study investigators S1 List of investigators and institutions.

Methods S1 Additional study methods: Assessments; Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria; Masking; Detailed statistical methods; Estimand framework; Analysis sets.

Table S1 Previous atopic dermatitis treatments, randomized patients.

Table S2 Investigator’s Global Assessment 0/1 by visit, initial treatment period, observed cases: full analysis set.

Table S3 Percentage change from baseline in Eczema Area and Severity Index by visit, initial treatment period, observed cases: full analysis set.

Table S4 Rescue medication use by type during the initial treatment period, randomized patients.

Table S5 Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0/1 and 50% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI 50) response at week 16 in the initial treatment period, all analyses, full analysis set.

Table S6 SCORing Atopic Dermatitis by visit, initial treatment period, observed cases: full analysis set.

Table S7 Change from baseline in SCORing Atopic Dermatitis by visit, repeated‐measurements analysis, initial treatment period: full analysis set.

Table S8 Dermatology Life Quality Index by visit, initial treatment period, observed cases: full analysis set.

Table S9 Change from baseline in Dermatology Life Quality Index by visit, repeated‐measurements analysis, initial treatment period: full analysis set.

Table S10 Reduction in weekly average of worst daily pruritus NRS ≥ 4, SCORing Atopic Dermatitis and Dermatology Life Quality Index response at week 16 in the initial treatment period, all analyses, full analysis set.

Table S11 Proportion of 50% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI 50), EASI 75 and EASI 90 responders. ECZTRA 3 responders, tralokinumab continuation treatment analysis set.

Figure S1 Testing hierarchy.

Figure S2 Patient disposition (CONSORT‐style figure). (a) Initial treatment period, randomized patients and (b) continuation treatment period, patients randomized to tralokinumab in the initial treatment period.

Figure S3 (a) 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI 75) response rate by visit and (b) EASI 90 response rate by visit in the initial treatment period, full analysis set.

Figure S4 Topical corticosteroid (TCS) use by visit during the initial treatment period (weeks 1–16), assuming no TCS used from the nonreturned tubes.

Figure S5 Distribution of amount of topical corticosteroid (TCS) used by visit and treatment group, assuming no TCS used from the nonreturned tubes, initial treatment period, full analysis set.

Figure S6 Topical corticosteroid use during the continuation treatment period (weeks 16–32) in patients in the continuation treatment analysis set with 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI 75) at week 16 achieved without rescue medication after initial randomization to tralokinumab.

Figure S7 Change from baseline by week over the entire treatment period (weeks 0–32) in patients in the continuation treatment analysis set initially randomized to tralokinumab: (a) percentage change in Eczema Area and Severity Index score and (b) change in Dermatology Life Quality Index score.

Powerpoint S1 Journal Club Slide Set.

Acknowledgments

We thank the ECZTRA 3 investigators and the patients who participated in the studies.

Conflicts of Interest statement

J.I.S. reports personal fees from AbbVie, AnaptysBio, Arena, Asana, Bluefin, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Dermavant, Dermira, DS Biopharma Kiniksa, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Luna, Menlo, Novartis, Pfizer, Realm, Regeneron and Sanofi‐Genzyme and grants and personal fees from Galderma and GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. D.T. reports being an investigator for AbbVie, Amgen, Arcutis, Avillion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Galderma, Genentech, Incyte, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Medimmune, Merck, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche and UCB and personal fees from Lilly outside the submitted work and being a principal investigator for LEO Pharma. T.B. reports personal fees from LEO Pharma during the conduct of the study and personal fees from AbbVie, Almirall, AnaptysBio, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Galapagos, Galderma, Glenmark, Kymab, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi and UCB outside the submitted work. A.F.A. reports nonfinancial support and grants from LEO Pharma during the conduct of the study, personal fees from Beirsdorf, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermavant, Foamix, Galderma, LEO Pharma, L’Oreal, Menlo, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi‐Regeneron, Scientis, UCB, Unilever and Valeant (Bausch Health) and grants from Almirall, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cara, Celgene, Galderma, Menlo, Novartis and Valeant (Bausch Health) outside the submitted work. B.E.E. has received honoraria as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun, Valeant (Ortho Dermatologics) and Verrica and has received research funding from AbbVie, AnaptysBio, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Menlo Therapeutics, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sun, Valeant (Ortho Dermatologics) and Vanda. A.E.P. reports personal fees and nonfinancial support from LEO Pharma, Novartis and UCB and personal fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Janssen, La Roche Posay Lilly and Sanofi outside the submitted work. D.H. reports grants from LEO Pharma during the conduct of the study, personal fees from AbbVie, Incyte, Lilly, Pfizer and Sanofi/Genzyme and grants from Thermo Fisher outside the submitted work. T.N.J., B.B., C.K.O. and A.K. are employees of LEO Pharma A/S. S.W. reports personal fees from AbbVie, Kymab, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer and Regeneron and grants and personal fees from La Roche Posay, LEO Pharma and Sanofi‐Genzyme outside the submitted work.

Funding sources The tralokinumab ECZTRA 3 trial was sponsored by LEO Pharma A/S (Ballerup, Denmark). Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Stephanie Rippon MBio, Amy Graham PhD and Jane Beck MA, from Complete HealthVizion, funded by LEO Pharma A/S.

Conflicts of interest See Appendix for the full statement of the authors’ conflicts of interest.

Plain language summary available online

References

- 1. Nutten S. Atopic dermatitis: global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann Nutr Metab 2015; 66 (Suppl. 1):8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2016; 387:1109–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 71:116–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boguniewicz M, Alexis AF, Beck LA et al. Expert perspectives on management of moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis: a multidisciplinary consensus addressing current and emerging therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017; 5:1519–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Simpson EL, Bruin‐Weller M, Flohr C et al. When does atopic dermatitis warrant systemic therapy? Recommendations from an expert panel of the International Eczema Council. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 77:623–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T et al. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018; 4:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bieber T. Interleukin‐13: targeting an underestimated cytokine in atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2020; 75:54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tazawa T, Sugiura H, Sugiura Y et al. Relative importance of IL‐4 and IL‐13 in lesional skin of atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res 2004; 295:459–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tsoi LC, Rodriguez E, Degenhardt F et al. Atopic dermatitis is an IL‐13 dominant disease with greater molecular heterogeneity compared to psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 2019; 139:1480–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tsoi LC, Rodriguez E, Stölzl D et al. Progression of acute‐to‐chronic atopic dermatitis is associated with quantitative rather than qualitative changes in cytokine responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020; 145:1406–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Szegedi K, Lutter R, Res PC et al. Cytokine profiles in interstitial fluid from chronic atopic dermatitis skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29:2136–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sanofi‐Aventis Groupe . Dupixent (dupilumab) Summary of Product Characteristics. 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product‐information/dupixent‐epar‐product‐information_en.pdf [accessed 11 February 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals . Dupixent (dupilumab) Label. 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761055s014lbl.pdf [accessed 11 February 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T et al. Consensus‐based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32:850–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Popovic B, Breed J, Rees DG et al. Structural characterisation reveals mechanism of IL‐13‐neutralising monoclonal antibody tralokinumab as inhibition of binding to IL‐13Rα1 and IL‐13Rα2. J Mol Biol 2017; 429:208–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. May RD, Monk PD, Cohen ES et al. Preclinical development of CAT‐354, an IL‐13 neutralizing antibody, for the treatment of severe uncontrolled asthma. Br J Pharmacol 2012; 166:177–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weidinger S, Tollenaere MA, Drerup K et al. Atopic dermatitis disease biomarkers strongly correlate with IL‐13 levels, are regulated by IL‐13, and are modulated by tralokinumab in vitro . SKIN J Cutan Med 2019; 3 (Suppl.):S42. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang C, Kraus CN, Patel KG et al. Real‐world experience of dupilumab treatment for atopic dermatitis in adults: a retrospective analysis of patients’ records. Int J Dermatol 2020; 59:253–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abraham S, Haufe E, Harder I et al.; TREATgermany study group . Implementation of dupilumab in routine care of atopic eczema: results from the German national registry TREATgermany. Br J Dermatol 2020; 183:382–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wollenberg A, Howell MD, Guttman‐Yassky E et al. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with tralokinumab, an anti‐IL‐13 mAb. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019; 143:135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatovener (Stockholm) 1980; 60 (Suppl. 92):44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wollenberg A, Blauvelt A, Guttman‐Yassky E et al. Tralokinumab for moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis: results from two 52‐week, randomized, double‐blind, multicentre, placebo‐controlled phase III trials (ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2). Br J Dermatol 2021; 10.1111/bjd.19574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guttman‐Yassky E, Silverberg JI, Fensholdt J et al. Tralokinumab significantly reduces Staphylococcus aureus colonization in adult patients with moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis (AD): results from a phase 2b, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study (NCT02347176). Presented at the 3rd Inflammatory Skin Disease Summit, Vienna, Austria, 12–15 December 2018. Exp Dermatol 2018; 27 (Suppl. 2):A96. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Study investigators S1 List of investigators and institutions.

Methods S1 Additional study methods: Assessments; Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria; Masking; Detailed statistical methods; Estimand framework; Analysis sets.

Table S1 Previous atopic dermatitis treatments, randomized patients.

Table S2 Investigator’s Global Assessment 0/1 by visit, initial treatment period, observed cases: full analysis set.

Table S3 Percentage change from baseline in Eczema Area and Severity Index by visit, initial treatment period, observed cases: full analysis set.

Table S4 Rescue medication use by type during the initial treatment period, randomized patients.

Table S5 Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0/1 and 50% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI 50) response at week 16 in the initial treatment period, all analyses, full analysis set.

Table S6 SCORing Atopic Dermatitis by visit, initial treatment period, observed cases: full analysis set.

Table S7 Change from baseline in SCORing Atopic Dermatitis by visit, repeated‐measurements analysis, initial treatment period: full analysis set.

Table S8 Dermatology Life Quality Index by visit, initial treatment period, observed cases: full analysis set.

Table S9 Change from baseline in Dermatology Life Quality Index by visit, repeated‐measurements analysis, initial treatment period: full analysis set.

Table S10 Reduction in weekly average of worst daily pruritus NRS ≥ 4, SCORing Atopic Dermatitis and Dermatology Life Quality Index response at week 16 in the initial treatment period, all analyses, full analysis set.

Table S11 Proportion of 50% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI 50), EASI 75 and EASI 90 responders. ECZTRA 3 responders, tralokinumab continuation treatment analysis set.

Figure S1 Testing hierarchy.

Figure S2 Patient disposition (CONSORT‐style figure). (a) Initial treatment period, randomized patients and (b) continuation treatment period, patients randomized to tralokinumab in the initial treatment period.

Figure S3 (a) 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI 75) response rate by visit and (b) EASI 90 response rate by visit in the initial treatment period, full analysis set.

Figure S4 Topical corticosteroid (TCS) use by visit during the initial treatment period (weeks 1–16), assuming no TCS used from the nonreturned tubes.

Figure S5 Distribution of amount of topical corticosteroid (TCS) used by visit and treatment group, assuming no TCS used from the nonreturned tubes, initial treatment period, full analysis set.

Figure S6 Topical corticosteroid use during the continuation treatment period (weeks 16–32) in patients in the continuation treatment analysis set with 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI 75) at week 16 achieved without rescue medication after initial randomization to tralokinumab.

Figure S7 Change from baseline by week over the entire treatment period (weeks 0–32) in patients in the continuation treatment analysis set initially randomized to tralokinumab: (a) percentage change in Eczema Area and Severity Index score and (b) change in Dermatology Life Quality Index score.

Powerpoint S1 Journal Club Slide Set.