Abstract

Objectives

Changes in reported lifetime prevalence of psychological abuse, controlling behaviours and economic abuse between 2003 and 2019, and past 12-month prevalence of psychological abuse by an intimate partner were examined.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis.

Setting and participants

Data came from two surveys of family violence in New Zealand, conducted in 2003 and 2019. Respondents were ever partnered women aged 18–64 years old (2003 n=2673; 2019 n=935).

Main outcome measures

Prevalence rates for psychological abuse, controlling behaviours and economic abuse were compared between the two study years using logistic regression. Sociodemographic and economic correlates of each abuse subtype were investigated. Interactions were examined between sociodemographic factors and the study year for reported prevalence rates.

Results

There was a reduction in reported past 12-month experience of two or more acts of psychological intimate partner violence (IPV) from 8.4% (95% CI 7.3 to 9.6) in 2003 to 4.7% (95% CI 3.2 to 6.2) in 2019. The reported lifetime prevalence of two or more acts of controlling behaviours increased from 8.2% in 2003 (95% CI 7.0 to 9.5) to 13.4% in 2019 (95% CI 11.0 to 15.7). Lifetime prevalence of economic IPV also increased from 4.5% in 2003 (95% CI 3.5 to 5.5) to 8.9% in 2019 (95% CI 6.7 to 11.1). Those who were divorced/separated or cohabiting, and those living in the most deprived areas were more likely to report past year psychological IPV, lifetime controlling behaviours and economic abuse. A higher proportion of women who were married or cohabiting reported controlling behaviours in 2019 compared with 2003.

Conclusion

While the reduction in reported past year psychological IPV is encouraging, the increase in the lifetime prevalence of controlling behaviours and economic abuse from 2003 to 2019 is worth critical evaluation. Results highlight potential gaps in current IPV prevention programmes, the need to identify and address underlying drivers of abusive behaviour and the importance of measuring multiple forms of IPV independently.

Keywords: public health, epidemiology, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The reported study used data collected from large, representative samples of women in 2003 and 2019.

Measures of lifetime exposure provide information on overall experience of seldom explored forms of intimate partner violence (IPV), including psychological abuse, controlling behaviours and economic abuse.

Observed changes may reflect societal changes or environmental factors not considered in this investigation.

Self-report of violence exposure, while the gold standard for data collection, may underestimate the true prevalence.

Regular surveys of violence exposure can provide an understanding of the effectiveness of population-based policies and programmes and changes in the overall experience of different types of IPV.

Introduction

Psychological abuse (also known as emotional abuse), economic abuse and controlling behaviours are tacit but prevalent types of intimate partner violence (IPV), which can result in serious health outcomes.1–10 However, historically these types of violence have been neglected in research and practice2 4 11 because of the focus on gaining recognition of physical and sexual IPV, and the challenges associated with the measurement of these behaviours. More recently, population-based studies have assessed the prevalence of recent (past 12 months) and lifetime experiences of psychological, economic abuse and controlling behaviours against women in high-income countries1 12–14 and low-income and middle-income countries.5 15–18

At present, there is a lack of consensus on how to measure these forms of abuse. For example, some previous research has classified controlling behaviours and economic abuse under the larger umbrella of psychological/emotional abuse2 6 7 19 20 while others report these as separate forms of abuse.13 21 22 Similarly, there is a lack of consensus on the measurement of economic abuse, with economic control, employment sabotage and economic exploitation three commonly identified tactics but which are not always measured.23

Previous research has found a strong correlation between the experience of physical and sexual violence and psychological and economic abuse14 24 25 with some suggesting that psychological abuse may precede physical IPV.26 27 Looking at patterns of change for these types of abuse at different time points can help us understand if they are distinct phenomena. Additionally, comparing results of prevalence rates and risk factors for psychological abuse, controlling behaviours and economic abuse in repeated cross-sectional studies can help to identify trends, gaps and sociodemographic associates for these types of abuse, independent of physical and sexual IPV, which may in turn inform the development of better prevention strategies.

New Zealand is one of a small number of countries6 28–31 that has conducted repeated population-based surveys that have included measures of psychological abuse, controlling behaviours and economic abuse. The first survey was conducted in 2003,32 and the repeat survey was conducted in 2019. Between the two surveys, a series of actions were taken to address family violence including; legislation (eg, amendments to family violence law and protection for victims act)33 and prevention campaigns (eg, the Family Violence: It’s Not Ok Campaign, and the ACC-funded Mates and Dates high school programme on healthy relationships).34 35 However, efforts have primarily focused on the recognition of and response to physical and sexual abuse.

In the current investigation, we sought to explore if there have been changes in the prevalence of women’s experience of psychological abuse, controlling behaviours and economic abuse by intimate partners. In addition, we were interested in testing if any observed prevalence changes were influenced by changes in women’s sociodemographic characteristics. Finally, to understand if different groups of women reported an increase or reduction between the two survey waves, we explored interactions between participants’ sociodemographic characteristics and study year.

Methods

Study design, location and participants

The present study used data from two national cross-sectional studies on family violence conducted in New Zealand in 2003 and 2019. The sampling framework was similar in both studies. Details on methods for these studies are published elsewhere.32 36 In brief, in the 2003 study women were recruited from Auckland and North Waikato regions, and in the 2019 study women were recruited from Auckland, Waikato and Northland. Cluster randomisation was used for both studies. Meshblock boundaries, provided by Stats NZ, were used as the starting point for recruitment. Meshblocks are smallest statistical units that are used for the census surveys. Non-residential and short-term residential properties, rest homes and retirement villages were excluded from both surveys. Interviewer training and support procedures were comparable across survey waves. The participants recruited for both surveys were broadly representative of women in the New Zealand population.32 36

Patients and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct or reporting or dissemination plans of the research.

Eligibility

Potential participants were household members who had been living in that address for at least 1 month, aged 18–64 years (for the 2003 study), or 16 years and above (for the 2019 study), and able to speak conversational English. In 2003, 2674 ever-partnered women aged 18–64 were recruited, and in 2019, 2888 (n=1464 women, n=1423 men, n=1 other) were recruited. To ensure comparability of the sample populations, only women aged between 18 and 64 years were included in this investigation.

Data collection

The questionnaire developed for the WHO Multi-Country Study on Domestic Violence and Women’s Health was used to measure violence against women in both studies.37

For selection of individuals within a household, interviewers identified all women aged over 16 years residing in the household. These were listed on the random selection form in order of oldest to youngest, and interviewers only interviewed one randomly selected woman per household, for safety reasons. Participants provided informed consent. No one over the age of 2 years was present during the interview. All respondents were provided with a list of approved support agencies regardless of disclosure status at the conclusion of the face-to-face interview.

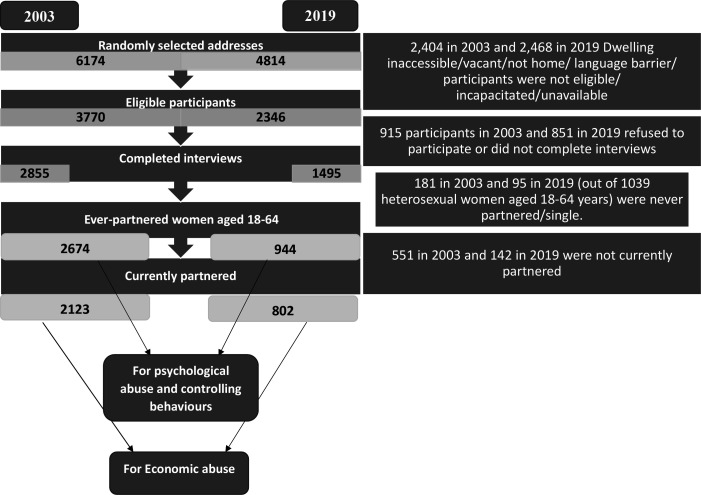

The number of people invited and those who were interviewed and included in each of the analyses are presented in figure 1. The response rate relative to total eligible women was 66.9% in 2003 and 63.7% in 2019. The number of ever-partnered women aged 18–64 years was 2674 in 2003 and 944 in 2019. For economic abuse, in 2003 questions were asked for currently partnered participants only. To ensure consistency, we used the currently partnered sample for this outcome in 2019. This reduced the total sample size for economic abuse to 2123 in 2003 and 802 in 2019. Weighting variables were not available for one woman from 2003 and nine from 2019 which reduced the total analytic sample to 2673 in 2003 and 935 in 2019 for psychological and controlling behaviours outcomes, and 2123 in 2003 and 794 in 2019 for economic abuse outcome.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of female participants in the 2003 and 2019 population-based studies of family violence in New Zealand.

Outcome measures

Outcome variables are defined in online supplemental table 1. Questions used to assess IPV experience were identical in the two survey waves. We initially report on the prevalence of one or two or more acts for lifetime and past year psychological abuse, as well as controlling behaviours. Further analyses considered only two or more acts of psychological abuse and controlling behaviours as a proxy for distinguishing a pattern of abuse rather than counting one-off incidents. We measured two acts of ‘economic control’ in both surveys. Women who reported having experienced either or both acts were classified as having experienced economic abuse.

bmjopen-2020-044910supp001.pdf (39KB, pdf)

For psychological abuse, past 12 months and lifetime experience were measured at both study years. For controlling behaviours and economic abuse, only lifetime experience of the abuse was measured in both study years.

Independent variables

Sociodemographic variables such as age, education, relationship status, access to independent source of income and family support were self-reported by respondents. We used the index of multiple deprivation to determine area level deprivation.38 See online supplemental table 2 for a description of independent variables.

bmjopen-2020-044910supp002.pdf (84.1KB, pdf)

Statistical analyses

SAS statistical package (V.9.4) was used for data analyses (SAS Institute). Missing data were excluded from all analyses. These included: do not know or do not remember, and no responses.

Using the merged database, first, the study years were compared in terms of sociodemographic variables, independent source of income, area deprivation level and family support using χ2 tests.

Then, the prevalence rates for each outcome were compared between the study years. For each of the three abuse types, results are presented as percentages (95% CIs). Then, to determine if there had been a change in estimated prevalence over time, OR and 95% CIs for reported experience of each outcome were determined using univariate logistic regression models in the merged database, with the study year as a predictor.

Then, the following steps were taken to address further research questions:

The association between each independent variable and each outcome (psychological abuse, controlling behaviour and economic abuse) was explored using univariate logistic regression models with pooled data from 2003 and 2019.

To determine if the relationship between independent and outcome variables remained significant across data collection periods, those variables for which a significant association was identified at the univariate level were included in the multivariate analyses, including the study year. This also allowed us to assess if any changes in independent variables over time influenced prevalence changes between the study years. Potential confounders (eg, age, education, relationship status, independent income and area deprivation level) were also included in multivariate analyses.

To determine if the noted changes in the reported prevalence rates were consistent across population subgroups, interaction terms between each of the independent variables that reached significance and the study year were added to the multivariate regression models.

All analyses were conducted with survey procedures to allow for stratification by sample location (three regions), clustering by primary sampling units and weighting of data to account for the number of eligible participants in each household.

Results

Sociodemographic differences between study samples are described in table 1. There was a smaller proportion of people aged 55 years and older in the 2003 sample (14.7%) compared with the 2019 sample (23.3%), and a smaller proportion of participants with tertiary education in the 2003 sample (44.8%) compared with the 2019 sample (65.2%). In the 2003 sample, a higher proportion of participants had an independent income (80.0%) compared with the 2019 sample (73.0%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of ever-partnered women aged 18–64 years in the New Zealand family violence studies conducted in 2003 and 2019

| 2003 | 2019 | P value | |

| Total sample | n=2673 | n=935 | |

| Age (years) | n (%)* | n (%) | <0.001 |

| 18–<30 | 401 (17.1) | 113 (14.9) | |

| 30–<45 | 1219 (43.5) | 316 (31.0) | |

| 45–<55 | 637 (24.6) | 264 (30.8) | |

| ≥55 | 416 (14.7) | 242 (23.3) | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||

| Primary/secondary | 1477 (55.2) | 310 (34.8) | |

| Tertiary | 1187 (44.8) | 621 (65.2) | |

| Relationship status | 0.41 | ||

| Married | 1685 (61.5) | 598 (63.3) | |

| Cohabiting | 574 (22.1) | 196 (21.2) | |

| Divorced/separated/broken up | 352 (14.3) | 116 (12.6) | |

| Widowed/partner died | 60 (2.1) | 25 (2.9) | |

| Independent income | <0.0006 | ||

| Yes | 2121 (79.6) | 688 (73.0) | |

| No | 551 (20.4) | 247 (27.0) | |

| Deprivation | 0.13 | ||

| Least deprived | 914 (33.6) | 269 (26.8) | |

| Moderately deprived | 1045 (38.8) | 387 (39.8) | |

| Most deprived | 707 (27.5) | 279 (33.4) | |

| Family support | 0.07 | ||

| Yes | 2401 (90.1) | 850 (92.2) | |

| No | 265 (9.8) | 78 (7.8) | |

*Weighted % are presented.

Table 2 shows the reported prevalence of experiencing past 12 months and lifetime psychological abuse by women in 2003 and 2019. There was no significant difference in reported lifetime prevalence estimates for psychological abuse between 2003 and 2019, however, a significant difference was found in reported past 12-month prevalence of experiencing at least one act of psychological abuse between 2003 and 2019 (OR=0.77; 95% CI 0.61 to 0.98) or two acts of psychological abuse, from 8.4% in 2003 to 4.7% in 2019 (OR=0.54; 95% CI 0.37 to 0.77).

Table 2.

Prevalence of recent (last 12 months) and lifetime psychological violence, lifetime economic abuse and lifetime controlling behaviour against women aged 18–64 years in two cross-sectional studies in New Zealand and their changes

| Violence type | Lifetime n% (95% CI)* | OR 95% CI | Past 12 months n% (95% CI) | OR 95% CI | ||

| 2003 | 2019 | 2003 | 2019 | |||

| Psychological abuse (n) | (n=2673) | (n=935) | (n=2673) | (n=935) | ||

| Insulted | 1216 45.8 (43.77 to 47.90) |

420 42.5 (38.72 to 46.34) |

0.87 (0.73 to 1.04) | 368 14.8 (13.27 to 1.41) |

104 11.2 (8.90 to 13.47) |

0.72 (0.56 to 0.93) |

| Humiliated | 805 30.1 (28.22 to 32.00) |

303 30.5 (27.13 to 33.94) |

1.02 (0.85 to 1.22) | 187 7.6 (6.47 to 8.68) |

54 5.6 (4.03 to 7.09) |

0.72 (0.51 to 1.00) |

| Intimidated | 705 26.4 (24.56 to 28.33) |

245 24.8 (21.75 to 27.91) |

0.92 (0.76 to 1.11) | 151 6.3 (5.18 to 7.34) |

24 2.6 (1.52 to 3.79) |

0.41 (0.25 to 0.66) |

| Threatened | 501 18.6 (16.96 to 20.20) |

155 15.5 (13.08 to 18.00) |

0.81 (0.65 to 1.00) | 78 3.2 (2.43 to 3.99) |

10 1.2 (0.42 to 1.97) |

0.36 (0.18 to 0.69) |

| At least one act of abuse | 1367 51.4 (49.37 to 53.47) |

489 49.3 (45.20 to 53.43) |

0.92 (0.76 to 1.10) | 430 17.4 (15.67 to 19.06) |

131 14.0 (11.58 to 16.40) |

0.77 (0.61 to 0.98) |

| Two or more acts of abuse | 922 34.3 (32.39 to 36.32) |

327 33.2 (29.83 to 36.60) |

0.95 (0.80 to 1.13) | 207 8.4 (7.25 to 9.57) |

45 4.7 (3.24 to 6.15) |

0.54 (0.37 to 0.77) |

| Economic abuse (n) | 2123 | 802 | ||||

| Taken her money | 53 2.7 (1.85 to 3.48) |

45 5.6 (3.70 to 7.43) |

2.15 (1.34 to 3.46) | |||

| Refused to give money for household expenses | 60 2.8 (2.10 to 3.58) |

58 6.6 (4.89 to 8.40) |

2.44 (1.65 to 3.60) | |||

| At least one act of abuse | 93 4.5 (3.47 to 5.49) |

75 8.9 (6.72 to 11.07) |

2.08 (1.45 to 2.97) | |||

| Controlling behaviour | ||||||

| Stopped her from seeing friends | 226 9.2 (7.89 to 10.50) |

153 15.5 (13.09 to 18.00) |

1.82 (1.42 to 2.32) | |||

| Restricted contact with her family | 132 5.3 (4.27 to 6.35) |

84 8.5 (6.61 to 10.46) |

1.67 (1.21 to 2.30) | |||

| Insisted to know where she is in ways that made her feel controlled or frightened | 458 18.1 (16.36 to 19.84) |

185 18.9 (16.23 to 21.68) |

1.06 (0.85 to 1.31) | |||

| At least one act of controlling behaviour | 531 20.8 (18.96 to 22.57) |

223 22.6 (19.69 to 25.53) |

1.11 (0.92 to 1.36) | |||

| Two or more acts of controlling behaviour | 199 8.2 (6.98 to 9.51) |

132 13.4 (11.05 to 15.74) |

1.72 (1.32 to 2.34) | |||

*Weighted % and 95% CIs are presented.

There was a significant increase in the reported lifetime prevalence rate of at least two acts of controlling behaviour, from 8.2% in 2003 to 13.4% in 2019 (OR=1.72; 95% CI 1.32 to 2.34). Similarly, there was an increase in the reported lifetime prevalence rate of one act of economic abuse, from 4.5% in 2003 to 8.9% in 2019 (OR=2.08; 95% CI 1.45 to 2.97) (table 2).

Table 3 shows the characteristics of women who reported experiencing two or more acts of lifetime and 12-month psychological abuse.

Table 3.

Characteristics of women with past 12 month and lifetime psychological intimate partner abuse in pooled database from two cross-sectional studies in New Zealand

| Abuse type | Last 12 month psychological abuse | Lifetime psychological abuse | ||||||

| Year | 2003 | 2019 | *Univariate model OR (95% CI) |

†Multivariate model AOR (95% CI) |

2003 | 2019 | *Univariate model OR (95% CI) |

†Multivariate model AOR (95% CI) |

| Act of abuse | Two/more n (%) |

Two/more n (%) |

Two/more n (%) |

Two/more n (%) |

||||

| Year (ref=2003) | 207 (8.4) | 45 (4.7) | 0.54 (0.37 to 0.77) | 0.57 (0.40 to 0.82) | 922 (34.3) | 327 (33.2) | 0.95 (0.80 to 1.13) | 0.97 (0.81 to 1.16) |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| 18–<30 | 50 (14.1) | 7 (6.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 134 (33.0) | 32 (23.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 30–<45 | 104 (8.8) | 19 (6.1) | 0.68 (0.45 to 0.93) | 0.79 (0.54 to 1.16) | 435 (35.8) | 107 (33.1) | 1.23 (0.98 to 1.55) | 1.97 (1.52 to 2.56) |

| 45–<55 | 34 (5.8) | 12 (4.2) | 0.40 (0.26 to 0.62) | 0.55 (0.34 to 0.86) | 223 (34.5) | 97 (35.5) | 1.21 (0.93 to 1.56) | 2.10 (1.58 to 2.80) |

| ≥55 | 19 (4.8) | 7 (2.6) | 0.30 (0.18 to 0.49) | 0.44 (0.25 to 0.75) | 130 (31.6) | 91 (36.8) | 1.14 (0.88 to 1.47) | 2.05 (1.54 to 2.73) |

| Education | ||||||||

| Primary/secondary | 131 (9.5) | 10 (3.7) | 1.00 | – | 540 (35.9) | 113 (33.8) | 1.00 | – |

| Tertiary | 76 (7.2) | 35 (5.3) | 0.76 (0.57 to 1.01) | – | 380 (32.5) | 212 (32.8) | 0.88 (0.75 to 1.02) | |

| Relationship status | ||||||||

| Married | 87 (5.6) | 24 (3.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 392 (23.1) | 157 (24.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Cohabiting | 66 (12.7) | 12 (6.0) | 2.28 (1.64 to 3.18) | 1.80 (1.26 to 2.58) | 287 (49.2) | 88 (42.3) | 2.91 (2.42 to 3.50) | 3.74 (3.06 to 4.57) |

| Divorced/separated/broken up | 54 (15.2) | 8 (6.8) | 2.79 (1.97 to 3.95) | 2.52 (1.79 to 3.54) | 223 (60.2) | 74 (61.5) | 4.96 (3.95 to 6.22) | 5.10 (4.04 to 6.43) |

| Widowed/partner died | 0 | 1 (2.9) | 0.19 (0.02 to 1.38) | 0.23 (0.03 to 1.70) | 19 (30.8) | 8 (26.5) | 1.34 (0.82 to 2.19) | 1.27 (0.77 to 2.08) |

| Independent income | ||||||||

| Yes | 163 (8.2) | 33 (4.6) | 0.98 (0.64 to 1.28) | – | 773 (36.0) | 248 (34.7) | 1.41 (1.17 to 1.70) | 1.20 (0.98 to 1.47) |

| No | 44 (9.3) | 12 (5.1) | 1.00 | 148 (27.7) | 79 (29.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Deprivation level | ||||||||

| Least deprived | 51 (6.4) | 9 (3.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 281 (31.6) | 80 (29.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderately deprived | 83 (8.3) | 22 (5.8) | 1.37 (0.97 to 1.94) | 1.28 (0.91 to 1.81) | 367 (34.6) | 141 (36.5) | 1.20 (1.01 to 1.43) | 1.10 (0.91 to 1.32) |

| Most deprived | 73 (11.3) | 14 (4.6) | 1.68 (1.16 to 2.44) | 1.45 (1.02 to 2.08) | 271 (37.5) | 106 (32.6) | 1.25 (1.02 to 1.53) | 1.06 (0.85 to 1.31) |

| Having family support | ||||||||

| Yes | 187 (8.4) | 41 (4.7) | 1.01 (0.63 to 1.61) | – | 811 (33.8) | 285 (31.7) | 0.72 (0.56 to 0.92) | 0.73 (0.56 to 1.47) |

| No | 20 (8.6) | 3 (3.3) | 1.00 | – | 109 (39.5) | 36 (46.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

*ORs from logistic regression are calculated from the pooled database.

†Model II ORs are adjusted for age, relationship status, deprivation status and the year of the study for past 12-month psychological abuse while independent income and family support were additionally controlled for lifetime psychological abuse.

AOR, adjusted OR.

For 12 month psychological abuse

The adjusted OR (AOR) in the multivariate model shows that after controlling for sociodemographic factors, and area deprivation level, there was still a significant decrease in the reported experience of past 12-month psychological abuse from 2003 to 2019 (AOR=0.57; 95% CI 0.40 to 0.82).

Age, relationship status and area deprivation level were significantly associated with reporting of two or more experiences of past 12-month psychological abuse at the multivariate level. A lower proportion of women aged ≥45 years reported experience of past 12-month psychological abuse compared with those aged 30 years and younger. A higher proportion of those who were cohabiting, or divorced compared with married reported this experience. As well, a higher proportion of women who lived in the most deprived areas reported experience of this abuse type compared with women who lived in the least deprived areas.

For lifetime psychological abuse

No significant differences were found in reported prevalence rates of lifetime psychological abuse between the two study years, after controlling for sociodemographic factors, area deprivation level and family support. Women aged 30 years and above were more likely to report having experienced two or more acts of lifetime psychological abuse. As well, those who were cohabiting and those who were divorced/separated were also more likely to report having experienced two/more acts of lifetime psychological abuse.

Lifetime controlling behaviours

The AOR shows that after controlling for sociodemographic variables, deprivation index and family support, the increase in prevalence rates of reporting two or more acts of controlling behaviours experienced remained significant (from 2003 to 2019; AOR=1.72; 95% CI 1.32 to 2.24). Those who were cohabiting, divorced or separated and widowed were more likely to report having experienced controlling behaviours compared with those who were married. Those who lived in the most deprived areas were more likely to report experiencing this abuse type, compared with those who lived in the least deprived areas (table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of women reporting lifetime experience of controlling behaviours and economic abuse by their intimate partner, in two cross-sectional New Zealand studies

| Abuse type | Controlling behaviour % (95% CI) | *Univariate model | †Multivariate model | Economic abuse % (95% CI) | *Univariate model I | †Multivariate model II | ||

| Year | 2003 | 2019 | 2003 | 2019 | ||||

| Acts of abuse | Two/more | Two/more | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | One/more | One/more | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) |

| n (row%) | n (row%) | n (row%) | n (row%) | |||||

| Year (ref=2003) | 199 (8.2) | 132 (18.4) | 1.72 (1.32 to 2.24) | 1.98 (1.47 to 2.64) | 93 (4.5) | 75 (8.9) | 2.08 (1.45 to 2.97) | 1.84 (1.30 to 2.62) |

| Age group | ||||||||

| 18–<30 | 36 (10.0) | 18 (13.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 16 (5.9) | 7 (8.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 30–<45 | 91 (7.9) | 42 (13.2) | 0.83 (0.57 to 1.19) | 1.06 (0.71 to 1.57) | 51 (5.3) | 24 (7.5) | 0.85 (0.49 to 1.47) | 1.60 (1.30 to 2.62) |

| 45–<55 | 43 (8.0) | 41 (14.7) | 0.94 (0.63 to 1.39) | 1.18 (0.76 to 1.84) | 17 (3.1) | 25 (10.2) | 0.82 (0.45 to 1.46) | 1.62 (0.85 to 3.08) |

| ≥55 | 30 (7.4) | 31 (12.1) | 0.84 (0.55 to 1.28) | 0.84 (0.50 to 1.40) | 9 (3.3) | 19 (9.5) | 0.83 (0.45 to 1.55) | 1.75 (0.89 to 3.45) |

| Education | ||||||||

| Primary/secondary | 134 (9.7) | 54 (15.3) | 1.00 | – | 57 (5.2) | 28 (10.3) | 1.00 | – |

| Tertiary | 65 (6.5) | 78 (12.5) | 0.78 (0.61 to 1.00) | – | 35 (3.6) | 46 (8.1) | 0.84 (0.59 to 1.18) | – |

| Relationship status | ||||||||

| Married | 45 (3.1) | 53 (8.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 55 (3.4) | 42 (6.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Cohabiting | 37 (7.0) | 39 (18.9) | 2.31 (1.64 to 3.24) | 2.30 (1.59 to 3.33) | 38 (8.8) | 33 (17.3) | 3.07 (2.16 to 4.34) | 3.22 (2.21 to 4.70) |

| Divorced/separated/broken up | 107 (31.2) | 36 (27.7) | 8.84 (6.50 to 12.01) | 8.88 (6.42 to 12.28) | – | – | – | |

| Widowed/partner died | 10 (15.2) | 4 (11.8) | 3.30 (1.79 to 6.11) | 3.28 (1.65 to 6.52) | – | – | – | |

| Independent income | ||||||||

| Yes | 168 (7.0) | 101 (14.0) | 1.18 (0.85 to 1.65) | – | 67 (4.2) | 55 (8.6) | 0.79 (0.53 to 1.16) | – |

| No | 30 (7.0) | 31 (11.7) | 1.00 | – | 26 (5.5) | 20 (9.6) | 1.00 | – |

| Deprivation level | ||||||||

| Least deprived | 36 (4.9) | 29 (9.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 19 (2.5) | 20 (7.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderately deprived | 76 (7.7) | 40 (10.1) | 1.41 (0.97 to 2.04) | 1.11 (0.76 to 1.63) | 31 (3.8) | 25 (7.6) | 1.37 (0.88 to 2.13) | 1.29 (0.83 to 1.99) |

| Most deprived | 86 (12.9) | 63 (20.1) | 2.77 (1.92 to 4.00) | 2.30 (1.59 to 2.84) | 43 (8.5) | 30 (11.8) | 2.83 (1.81 to 4.42) | 2.22 (2.21 to 4.70) |

| Having family support | ||||||||

| Yes | 164 (7.6) | 112 (12.6) | 0.55 (0.39 to 0.79) | 0.64 (0.42 to 0.96) | 84 (4.4) | 64 (8.1) | 0.70 (0.41 to 1.19) | – |

| No | 35 (13.8) | 16 (19.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 8 (4.8) | 10 (18.2) | 1.00 | – |

*OR from logistic regression were calculated using the pooled database.

†ORs were adjusted for age, relationship status and deprivation status. For controlling behaviour abuse, education status and having family support were also included in the multivariate model.

AOR, adjusted OR.

Lifetime economic abuse

The AOR shows that after controlling for sociodemographic variables and area deprivation level, the reported increase in prevalence rate of one act of economic abuse experience was still significant (AOR=1.84; 95% CI 1.30 to 2.62). Those aged 30 years and above, and those who were cohabiting were more likely to report experiencing economic abuse compared with those who were aged below 30 years, and those who were married, respectively. Similar to the previous abuse types, those who lived in the most deprived areas were more likely to report an experience of economic abuse compared with those who lived in the least deprived areas (table 4).

There was a significant interaction between relationship status and study year for reports of two or more acts of controlling behaviour. A higher proportion of women who were married reported lifetime experience of controlling behaviours in 2019 (8.8%) compared with 2003 (3.1%), as did women who were cohabiting (18.9% in 2019 and 7.0% in 2003). Although the highest prevalence rates for controlling behaviours were reported by women who were divorced, broken up or separated, the rates were not significantly different between the two survey years (table 5; p value for interaction=0.0002).

Table 5.

Interaction effects of relationship status on lifetime controlling behaviours, by the study year

| Variable | Level | Lifetime controlling behaviours (≥2 acts) | *Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value for interaction test | |

| Year 1 N (%) |

Year 2 N (%) |

||||

| Relationship status | Married | 45 (3.1) | 53 (8.8) | 3.54 (2.90 to 5.47) | 0.0002 |

| Cohabiting | 37 (7.0) | 39 (18.9) | 4.67 (2.74 to 7.95) | ||

| Divorced/separated/broken up | 107 (31.2) | 36 (27.7) | 0.94 (0.56 to 1.58) | ||

| Widowed/ partner died | 10 (15.2) | 4 (11.8) | 1.33 (0.34 to 5.13) | ||

*Controlling for age, education, independent income and deprivation level.

No other interactions were significant for reports of past 12 months and lifetime psychological abuse, or lifetime economic abuse.

Discussion

This study compared women’s reports of prevalence rates of past 12 months and lifetime experience of psychological abuse, and the lifetime experience of economic abuse, and controlling behaviours by an intimate partner, as assessed through population-based studies conducted in 2003 and 2019. There was no difference in reported lifetime psychological abuse between the 2 years, with a third of women (33%–34%) in both surveys reporting having experienced at least two acts of psychological IPV in their lifetime. However, the proportion of women who reported past 12-month psychological abuse decreased significantly. In contrast, the reported lifetime prevalence of controlling behaviours doubled from 8.2% in 2003 to 18.4% in 2019, as did the reported lifetime prevalence of economic abuse (4.5% in 2003 to 8.9% in 2019).

There are three possible explanations for study findings, including: actual changes in perpetrator behaviour over time; changes in women’s reporting of experience of violent behaviour due to changes in awareness of and willingness to report, and changes due to differences in methods, measurement or samples. These are discussed in turn.

There is some evidence that changes in perpetrator behaviour may have occurred, as the reduction in the 12-month prevalence of psychological abuse between 2003 and 2019 is consistent with a reduction in 12-month prevalence of physical IPV noted in the same sample. However, if the differences are based on actual changes in perpetrator behaviour, then it also appears that there may have been a shift in the use of abusive tactics within intimate relationships, as indicated by the increase in the reported experience of controlling behaviours and economic abuse.39 Similar patterns have been observed in intervention studies with men who perpetrate intimate partner violence, with reductions in physical, sexual and verbal (psychological abuse) violence showing early change,40 while changes in use of controlling and coercive tactics may be more uneven, contradictory and may take more time.41 As controlling behaviours and economic abuse are seldom prosecuted or indeed recognised, the shift in tactics could be advantageous to those who use violence as they carry less risk of penalty.23 42 It may also be that controlling behaviours and economic abuse have different drivers, and function differently in relationships than other forms of intimate partner violence.18

If the observed changes reflect actual differences in use of these forms of intimate partner violence, then further exploration of the causes of such behaviour change are warranted. There have been a series of strategies and campaigns implemented between the two study years, with a focus on sexual and physical IPV, which may have also contributed to a decline in the past 12-month psychological abuse.41 National efforts such as the Family Violence: It’s Not Ok Campaign may have contributed to this decrease, as there is some evidence that it had wide population reach.40 Of note, however, controlling behaviours and economic abuse were not widely discussed in this prevention campaign. Further work is needed on identifying and addressing the underlying drivers of abusive behaviour, such as issues of gender inequality, harmful conceptualisations of masculinity and femininity,42 and unpacking issues of power, control and entitlement.43 44

While the increased prevalence of controlling behaviours and economic abuse could have resulted from changes in women’s reporting of these experiences (as a function of increased recognition of and/or increased willingness to report such behaviours between 2003 and 2019), this interpretation seems less likely, as changes based solely on women’s reporting would likely also have contributed to increased reports of psychological abuse. The increased reports of lifetime economic abuse, particularly among women aged 30 years and older, could also be reflective of other factors, including: greater exposure time (ie, the women are older, so there is more time in which they may have experienced abuse); a greater likelihood of them having joint bank accounts or shared property, business or other combined finances with their partners compared with their younger peers; or increased likelihood of being employed, which could yield more finances to be controlled.13

Comparability of methods across the two surveys, including use of identical questions, lends strength to the interpretation that the prevalence changes observed are real. Additionally, while there some differences in the characteristics of the two samples, the AOR showed that after controlling for all sociodemographic factors, the observed differences in prevalence still remained significant.

Additional survey waves would also facilitate confirmation or clarification of the within-population differences observed in the present study. Examples include the substantive increase in controlling behaviour from 2003 to 2019 that mainly occurred among those who were married or cohabiting. While consistent with data from previous research45 further research is needed to determine why this difference may exist. One possibility is that it is an example of ‘constraint through commitment’ related to being constrained by one’s partner to uphold cultural conventions of heterosexual marriage46

Other findings from the present study are both consistent with previous research, and theoretically plausible enough to warrant current policy and programmatic action. These include the finding that having family support available in an emergency was associated with decreased risk of experiencing lifetime controlling behaviours, a finding consistent with other research that has noted the importance of social support as a protective factor against abuse.28 45 Additionally, the finding that those living in the most deprived areas had increased odds of reporting lifetime controlling behaviour and economic abuse is consistent with previous research28 and highlights the continued importance of implementing strategies to increase equity.

Limitations

The results are based on population samples from 2003 and 2019 with response rates of about 64%. Given that women who experience severe forms of violence are unlikely to participate in surveys such as that conducted, it is likely that the reported rates are an underestimate of the true prevalence. In addition, it is possible that changes between the two study years could be due to other societal, environmental factors that were not included in these analyses.

Measurement limitations also exist. These include the fact that measurement of forms of abuse for this study were based on a small number of questions for each IPV type. There was also no assessment of experience of economic abuse in the past 12 months, and the overall sample for those reporting economic abuse in 2019 was small. Measurement non-invariance may also limit our ability to accurately assess changes with different groups over time.

Strengths and future study directions

This study included a large sample of women from two cross-sectional studies on intimate partner violence conducted in 2003 and 2019. It is the first time that two survey samples with matching methods have compared three seldomly reported forms of IPV. Future qualitative and quantitative research is warranted to determine if the considerable increase reported in economic abuse and controlling behaviour represents a true change or is the result of increased awareness. Future studies could be strengthened by inclusion of a greater number of questions to assess different abuse types.

Conclusion

In summary, the decrease in the reported prevalence of past 12-month psychological abuse is positive and consistent with the decrease in reported 12-month prevalence of physical IPV.47 The increase in reported prevalence of economic abuse and controlling behaviours shows that these experiences should be measured separately and not conflated under the umbrella of psychological abuse.

This also has relevance from a policy and practice perspective, as it indicates that controlling behaviours and economic abuse need their own recognition and response. Currently, in New Zealand law, they are considered as forms of psychological abuse.48 It has been suggested that a legislative amendment to the Family Violence Act is needed to recognise economic abuse separately from psychological abuse,49 however, any legislative change would need enhanced understandings of these forms of violence and to be supported by procedural changes that enables prosecution of this form of abuse.49 Further consideration is required to understand how to effectively prevent violence experience, including impacting on masculine norms.

Given the limited research available on the prevalence and consequences of controlling behaviour and economic abuse, the sharp increases in these behaviours noted in the present study suggest that further work is needed to understand the consequences of these behaviours and to develop appropriate prevention and mitigation strategies. Further survey waves would strengthen understanding of changes of the prevalence of violence that may be occurring in the population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge participants, the interviewers, and the study project team, led by Patricia Meagher-Lundberg. We also acknowledge the representatives from the Ministry of Justice, the Accident Compensation Corporation, the New Zealand Police and the Ministry of Education, who were part of the Governance Group for Family and Sexual Violence at the inception of the study. The two cross-sectional studies from which this study used data are based on the WHO Violence Against Women Instrument as developed for use in the WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence and has been adapted from the version used in Asia and the Pacific by kNOwVAWdata V.12.03). It adheres to the WHO ethical guidelines for the conduct of violence against women research.

Footnotes

Contributors: JF and PG contributed to the conception and design of the study. TM contributed to the application for funding of 2019 study. LH managed the data cleaning. LH and ZM conducted the analyses. ZM and JF interpreted the data, drafted the article and revised it. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the Health Research Council of New Zealand (Grant 02/207) for the 2003 study and the New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, Contract number CONT-42799-HASTR-UOA for the 2019 study. We declare that there is no conflict of interest. The funding organisations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; and in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: Competing interests hereby we confirm that all authors read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare that we received: no support from any organisation for the submitted work (or describe if any); no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was granted by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee in 2003 (Ref number: 2002/199) and 2019 (Reference number 2015/ 018244).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available. Data are unavailable due to the confidentiality and sensitivity of the data and Māori data sovereignty.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1. Gibbs A, Dunkle K, Jewkes R. Emotional and economic intimate partner violence as key drivers of depression and suicidal ideation: a cross-sectional study among young women in informal settlements in South Africa. PLoS One 2018;13:e0194885. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med 2002;23:260–8. 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00514-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HAFM, Ellsberg M, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the who multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet 2006;368:1260–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adams AE, Sullivan CM, Bybee D, et al. Development of the scale of economic abuse. Violence Against Women 2008;14:563–88. 10.1177/1077801208315529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krantz G, Vung ND. 2The role of controlling behaviour in intimate partner violence and its health effects: a population based study from rural Vietnam. BMC Public Health 2009;9:1–10. 10.1186/1471-2458-9-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smith K, Zhang X, Basile KC, et al. The National intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2015 data brief — updated release. Atlanta, Gorgia, 2018. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf

- 7. European Union agency for fundamental rights (EUAFR) . Violence against women: an EU-wide survey: main results. Vienna, Austria: FRA, European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fanslow JL, Robinson EM, Sticks REM. Sticks, stones, or words? counting the prevalence of different types of intimate partner violence reported by new Zealand women. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma 2011;20:741–59. 10.1080/10926771.2011.608221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Family domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the National story 2019, 2019. Available: www.aihw.gov.au

- 10. Family Violence Death Review Committee . Sixth report | Te Pūrongo tuaono: men who use violence | Ngā tāne KA whakamahi I te whakarekereke. Wellington: Health Quality & Safety Commission, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jewkes R. Emotional abuse: a neglected dimension of partner violence. Lancet 2010;376:851–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61079-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith PH, Thornton GE, Devellis R, et al. A population-based study of the prevalence and distinctiveness of battering, physical assault, and sexual assault in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women 2002;8:1208–32. 10.1177/107780120200801004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kutin J, Russell R, Reid M. Economic abuse between intimate partners in Australia: prevalence, health status, disability and financial stress. Aust N Z J Public Health 2017;41:269–74. 10.1111/1753-6405.12651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karakurt G, Silver KE. Emotional abuse in intimate relationships: the role of gender and age. Violence Vict 2013;28:804–21. 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kapiga S, Harvey S, Muhammad AK, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence and abuse and associated factors among women enrolled into a cluster randomised trial in northwestern Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2017;17:190. 10.1186/s12889-017-4119-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kwaramba T, Ye JJ, Elahi C, et al. Lifetime prevalence of intimate partner violence against women in an urban Brazilian City: a cross-sectional survey. PLoS One 2019;14:e0224204. 10.1371/journal.pone.0224204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mendonça MFSde, Ludermir AB. Intimate partner violence and incidence of common mental disorder. Rev Saude Publica 2017;51:32. 10.1590/S1518-8787.2017051006912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yount KM, Krause KH, VanderEnde KE. Economic coercion and partner violence against wives in Vietnam: a unified framework? J Interpers Violence 2016;31:3307–31. 10.1177/0886260515584350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, et al. The world report on violence and health. Lancet 2002;360:1083–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ansara DL, Hindin MJ. Exploring gender differences in the patterns of intimate partner violence in Canada: a latent class approach. J Epidemiol Community Health 2010;64:849–54. 10.1136/jech.2009.095208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lövestad S, Löve J, Vaez M, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence and its association with symptoms of depression; a cross-sectional study based on a female population sample in Sweden. BMC Public Health 2017;17:1–11. 10.1186/s12889-017-4222-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beck JG, McNiff J, Clapp JD, et al. Exploring negative emotion in women experiencing intimate partner violence: shame, guilt, and PTSD. Behav Ther 2011;42:740–50. 10.1016/j.beth.2011.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stylianou AM. Economic abuse within intimate partner violence: a review of the literature. Violence Vict 2018;33:3–22. 10.1891/0886-6708.33.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gondolf EW, Heckert DA, Kimmel CM. Nonphysical abuse among batterer program participants. J Fam Violence 2002;17:293–314. 10.1023/A:1020304715511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Graham-Kevan N, Archer J. Does controlling behavior predict physical aggression and violence to partners? J Fam Violence 2008;23:539–48. 10.1007/s10896-008-9162-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. O'Leary KD. Psychological abuse: a variable deserving critical attention in domestic violence. Violence Vict 1999;14:3–23. 10.1891/0886-6708.14.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schumacher JA, Leonard KE. Husbands' and wives' marital adjustment, verbal aggression, and physical aggression as longitudinal predictors of physical aggression in early marriage. J Consult Clin Psychol 2005;73:28–37. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lövestad S, Krantz G. Men's and women's exposure and perpetration of partner violence: an epidemiological study from Sweden. BMC Public Health 2012;12:945. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang C-C, Postmus JL, Vikse JH, et al. Economic abuse, physical violence, and Union formation. Child Youth Serv Rev 2013;35:780–6. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.01.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stickley A, Carlson P. Factors associated with non-lethal violent victimization in Sweden in 2004-2007. Scand J Public Health 2010;38:404–10. 10.1177/1403494810364560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018. Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fanslow J, Robinson E. Violence against women in New Zealand: prevalence and health consequences. N Z Med J 2004;117:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clearinghouse NZFV . Timeline | New Zealand family violence Clearinghouse, 2020. Available: https://nzfvc.org.nz/?q=timeline/2010/2100

- 34. Fenrich J, Contesse J. ’It’s not OK’ :New Zealand’s efforts to eliminate violence against women. New York: Leitner Center for International Law and Justice, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Appleton-Dyer S, Soupen A, Edirisuriya N. Report on the 2016 mates and dates survey: report for the violence prevention portfolio at ACC. Auckland: Synergia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fanslow J, Gulliver P, Hashemi L. Methods for the 2019 New Zealand family violence study -A study on the association between violence exposure, health and wellbeing. Kōtuitui New Zeal J Soc Sci 2020;22:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HAFM, Ellsberg M, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. The Lancet 2006;368:1260–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Exeter DJ, Zhao J, Crengle S, et al. The New Zealand indices of multiple deprivation (IMD): a new suite of indicators for social and health research in Aotearoa, New Zealand. PLoS One 2017;12:e0181260. 10.1371/journal.pone.0181260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rothman EF, Butchart A, Cerdá M. Intervening with perpetrators of intimate partner violence: a global perspective. Geneva, 2003. Available: www.inis.ie

- 40. Westmarland N, Kelly L. Domestic violence perpetrator programmes: steps towards change. project Mirabal final report. project report. London and Durham: London Metropolitan University and Durham University; 2015. http://www.respect.uk.net/data/files/respect_research_briefing_note_1_what_counts_as_success.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 41. Downes J, Kelly L, Westmarland N. ‘It’s a work in progress’: men’s accounts of gender and change in their use of coercive control. Journal of Gender-Based Violence 2019;3:267–82. 10.1332/239868019X15627570242850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. UN Women . A framework to underpin action to prevent violence against women. United nations, 2015. Available: https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2015/prevention_framework_unwomen_nov2015.pdf?la=en&vs=5223

- 43. Pence E, Paymar M. Education Groups for Men Who Batter: The Duluth Model: 9780826179906: Medicine & Health Science Books @ Amazon.com. 1st editio, 1993. Available: https://www.amazon.com/Education-Groups-Men-Who-Batter/dp/0826179908

- 44. Anderson KL. Gendering coercive control. Violence Against Women 2009;15:1444–57. 10.1177/1077801209346837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nybergh L, Taft C, Enander V, et al. Self-Reported exposure to intimate partner violence among women and men in Sweden: results from a population-based survey. BMC Public Health 2013;13:845. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Crossman KA, Hardesty JL. Placing coercive control at the center: what are the processes of coercive control and what makes control coercive? Psychol Violence 2017;8:196–206. 10.1037/vio0000094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fanslow JL, Hashemi L, Malihi Z. Change in prevalence rates of physical and sexual intimate partner violence against women: data from two cross-sectional studies in New Zealand, 2003 and 2019. BMJ Open 2021. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. New Zealand Legislation . Domestic violence Amendment act 2013 no 77 (as at 01 July 2019), public act – New Zealand legislation, 2019. Available: http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2013/0077/latest/whole.html#DLM5615634

- 49. Milne S, Maury S, Gulliver P. Economic abuse in New Zealand: towards an understanding and response. Christchurch: Good Shepherd Australia New Zealand, 2018. www.goodshep.org.au [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-044910supp001.pdf (39KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-044910supp002.pdf (84.1KB, pdf)