Abstract

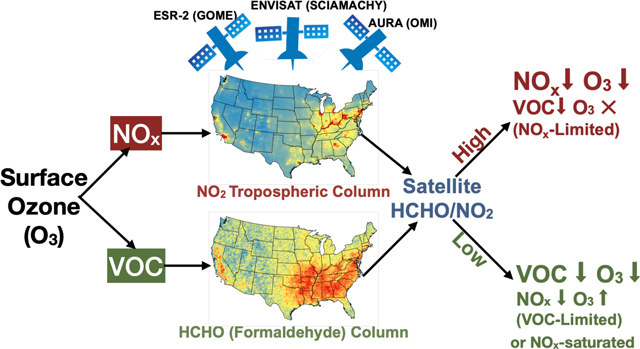

Urban ozone (O3) formation can be limited by NOx, VOCs, or both, complicating the design of effective O3 abatement plans. A satellite-retrieved ratio of formaldehyde to NO2 (HCHO/NO2), developed from theory and modeling, has previously been used to indicate O3 formation chemistry. Here, we connect this space-based indicator to spatiotemporal variations in O3 recorded by on-the-ground monitors over major U.S. cities. High-O3 events vary non-linearly with OMI HCHO and NO2, and the transition from VOC-limited to NOx-limited O3 formation regimes occurs at higher HCHO/NO2 value (3 to 4) than previously determined from models, with slight inter-city variations. To extend satellite record back to 1996, we develop an approach to harmonizing observations from GOME and SCIAMACHY that accounts for differences in spatial resolution and overpass time. Two-decade (1996 – 2016) multi-satellite HCHO/NO2 captures the timing and locations of the transition from VOC-limited to NOx-limited O3 production regime in major U.S. cities, which aligns with the observed long-term changes in urban-rural gradient of O3 and the reversal of O3 weekend effect. Our findings suggest promise for applying space-based HCHO/NO2 to interpret local O3 chemistry, particularly with the new-generation satellite instruments that allow evaluations at finer spatial and temporal resolution.

Keywords: satellite remote sensing, formaldehyde, nitrogen dioxide, ozone production regime, O3 trend, O3 weekend effect

INTRODUCTION

Human exposure to ground-level ozone (O3) is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, and has been linked to 250,000 O3-related premature deaths in 2015 globally,1 and 11,700 deaths over the United States (U.S.).2 In the troposphere, O3 is produced from photochemical reactions involving its precursors: nitrogen oxides (NOx: NO + NO2) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). It is well established that O3 formation throughout much of the troposphere is largely controlled by the availability of NOx, but in regions with high NOx emissions, such as metropolitan areas, O3 formation can be VOC-limited or in transition between these regimes.3,4 Identifying the most effective emissions control strategy to lower the O3 exposure of a densely populated metropolitan area requires knowledge of the local O3 formation chemistry.

While current satellite-based spectrometers do not retrieve ground-level O3 abundances, they have provided continuous global observations for two species indicative of O3 precursors, namely nitrogen dioxide (NO2) for NOx,5–7 and formaldehyde (HCHO) for VOC,8–13 for over two decades. In theory, the ratio of HCHO to NO2 (HCHO/NO2) reflects the relative availability of NOx and total organic reactivity to hydroxyl radicals.14,15 We build here upon earlier work proposing this satellite-based HCHO/NO2 serves as an indicator of O3 sensitivity to its NOx versus VOC precursors.16–19 All of these prior studies use theory as represented in models to link column-based HCHO/NO2 with surface O3 sensitivity.16–19 Models, however, can be biased,20 and airborne measurements suggest large uncertainty in the HCHO/NO2 threshold values between O3 production regimes.21 Also, modeled and satellite retrieved HCHO and NO2 often disagree,19,22,23 and the difference varies by satellite retrievals.19,24 To overcome these limitations, we derive the threshold values marking transitions in O3 formation regimes entirely from observations by directly connecting space-based HCHO/NO2 with ground-based measurements of O3.

Over the U.S., nationwide anthropogenic NOx emissions are estimated to have declined by 31% from 1997 to 2016.25 Correspondingly, satellite-retrieved NO2 tropospheric columns are declining,7,26,27 although relating NO2 columns directly to NOx emissions requires accounting for lifetime changes,28 and accurate partitioning between anthropogenic versus background sources of NO2.22,29 Despite the widespread decrease of NOx emissions, observed O3 trends are heterogeneous in space and time: decreasing in summer over less urbanized areas, and increasing in winter, night and urban cores, due to the non-linear relationship between O3 production and NOx.30–33As NOx emissions continue to decline, O3 formation over VOC-limited urban areas is transitioning towards the NOx-limited regime,19,34–36 but the observed long-term O3 trends may also reflect changes in VOC reactivity,37 as well as meteorology.38 U.S. anthropogenic VOC emissions from vehicles and industry are estimated to have declined by 22% from 1997 to 2016,25 while volatile chemical product emissions may be growing.39 Regionally, summertime U.S. VOC emissions are dominated by biogenic sources, particularly highly reactive isoprene, that vary with meteorology and vegetation density.40

A key policy-relevant metric is the turning point between VOC-limited and NOx-limited O3 formation regimes. It remains uncertain as to which (and whether) U.S. cities have reached this turning point, and how closely long-term changes in O3 follow transitions in O3 production regimes, particularly in light of the strong sensitivity of O3 to meteorological variability.41,42 Previous studies used observations of HCHO/NO2 from single satellite instrument, such as Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI), which dates back to 200518,19,26 The newly developed, consistently retrieved multi-satellite HCHO and NO2 products, available from the EU FP7-project Quality Assurance for Essential Climate Variables (QA4ECV),43–49 offers a new opportunity to extend the record back by a decade to 1996. We first assess if space-based HCHO/NO2 captures the non-linearity of O3 chemistry by matching daily OMI observation with ground-based O3 measurements over polluted areas. We find a robust relationship between space-based HCHO/NO2 and the O3 response patterns that is qualitatively similar but quantitatively distinct across cities. Next, we link the long-term changes in the harmonized multi-satellite HCHO/NO2 to changes in urban-rural O3 gradients and the O3 weekend effect from 1996 to 2016. We show that this multi-satellite HCHO/NO2 complements ground-based networks by providing insights into spatial heterogeneity and long-term evolution of O3 formation regimes, which could be valuable for future applications over regions lacking dense ground-based monitors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Multi-satellite Observations of O3 Precursors.

We use 21-year (1996 – 2016) multi-satellite products of tropospheric NO2 (ΩNO2) and HCHO (ΩHCHO) vertical columns developed under the QA4ECV project that retrieves products consistently from three satellite instruments: Global Ozone Monitoring Experiment (GOME), SCanning Imaging Absorption spectroMeter for Atmospheric CHartographY (SCIAMACHY) and OMI.43–49 The nadir resolution is 24 × 13 km2 for OMI, 60 × 30 km2 for SCIAMACHY and 320 × 40 km2 for GOME. The overpass time is around 1:30 PM local time for OMI, 10:00 AM for SCIAMACHY and 10:30 AM for GOME. The a priori vertical profiles used for QA4ECV products are obtained from the same chemical transport model (TM5-MP),50 which are better suited for analyzing space-based HCHO/NO2 than products developed with different prior profiles. The retrieval algorithms are briefly described in the Supplement (S1). We select daily Level-2 observations with: (1) no processing error; (2) less than 10% snow or ice coverage; (3) solar zenith angle less than 80˚ for NO2, and 70˚ for HCHO; (4) cloud radiance fractions < 0.5. For OMI, we exclude the first and last five rows, which contain large pixels retrieved on the swath edges, and select the rows 5 to 23, which are unaffected by row anomalies throughout the study period.51 We grid Level-2 swaths by calculating area weighted averages (S2).

Seasonal Harmonization of GOME, SCIAMACHY and OMI.

To study the long-term changes in HCHO, NO2 and HCHO/NO2 (Figures 2 to 4), we construct seasonal average ΩHCHO and ΩNO2 from the three satellites by calculating the area-weighted averages from 1996 to 2016. The long-term satellite records are based on OMI observations for the years after 2005, the harmonized SCIAMACHY observations for 2002 – 2004, and harmonized GOME observations before 2002. Even with the consistent algorithms for retrieving NO2 and HCHO under the QA4ECV project, multi-satellite retrievals still need to be harmonized to account for differences in horizontal resolution, overpass time, and any instrumental offsets. We adjust SCIAMACHY and GOME HCHO and NO2 data with reference to OMI, because OMI has the finest spatial resolution, and the satellites are best able to capture chemical conditions controlling O3 production during the OMI afternoon overpass, when mixing depths and O3 production rates are closest to their daily maxima. We first adjust SCIAMACHY ΩNO2 by decomposing the instrumental differences between SCIAMACHY and OMI into two factors: 1) those associated with different overpass timing or instrumental offsets, which we estimate as the difference in OMI ΩNO2 and SCIAMACHY ΩNO2 during the overlap period (2005 – 2011) at a coarse resolution at which we assume the difference is independent of the instrumental resolution (, Figure S1); 2) those caused by resolution (RCNO2, Figure S2), which we estimate as the relative change in OMI ΩNO2 at a fine-resolution (0.125˚× 0.125˚ ) versus a coarse-resolution (2˚ × 0.5˚) grid that is close to the nadir resolution of GOME (RCNO2_OMI, S3). While previous studies assumed constant resolution correction factors,27,52 we find that RCNO2 varies with time, especially over urban areas, and the spatial gradients in ΩNO2 are larger earlier in the record when ΩNO2 is higher earlier in the record (Figure S3). Assuming a time-invariant RCNO2 may thus underestimate the steepness of spatial gradients at high ΩNO2. We apply the relative temporal variability estimated from RCNO2_SCIA to the long-term summertime average RCNO2_OMI . RCNO2_OMI and RCNO2_SCIA correlate well in time (Figure S4), though their absolute values differ. Combining these factors, the adjusted SCIAMACHY ΩNO2 (ΩNO2_adj) at year yr season m (we focus on summer, June-July-August) and grid cell x is estimated as follows:

| (1) |

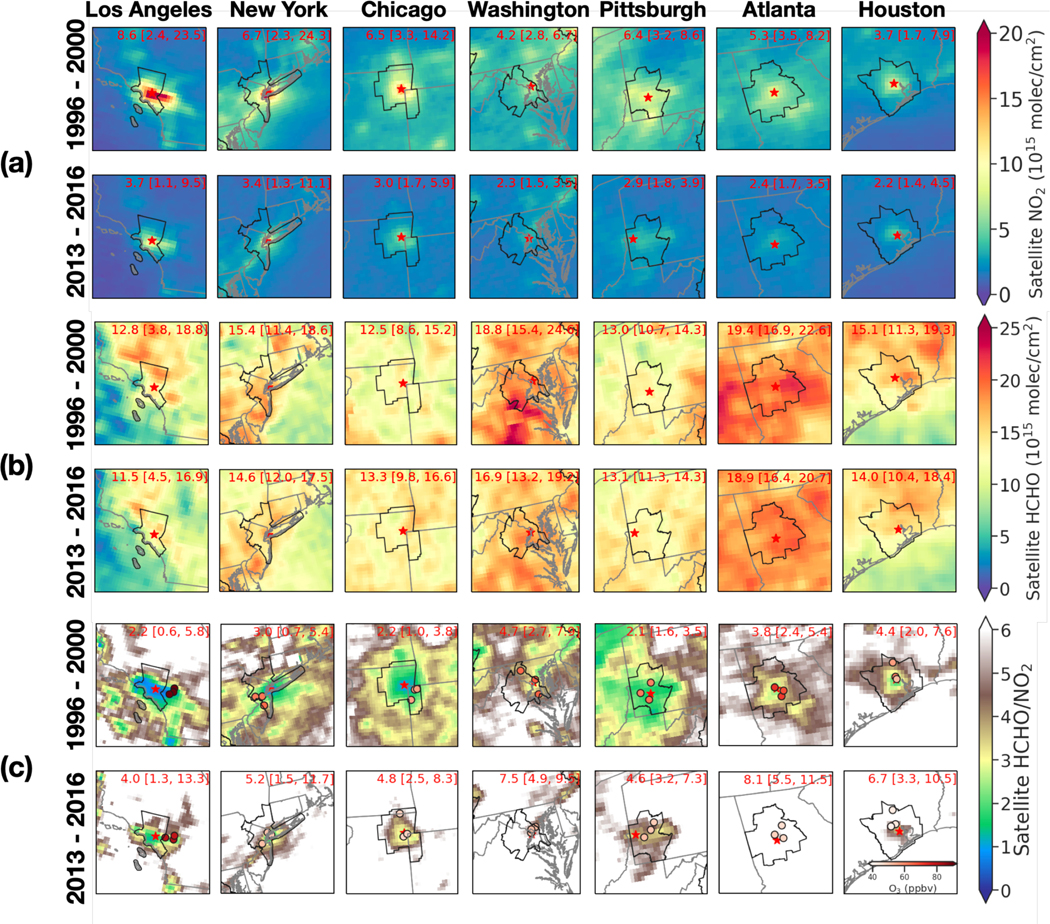

Figure 2.

Maps of summertime average: (a) satellite-based ΩNO2, (b) ΩHCHO and (c) HCHO/NO2 for seven cities (New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Washington DC, Pittsburgh, Atlanta and Houston) in 1996 – 2000 and 2013 – 2016. The white area in (c) indicates HCHO/NO2 above 6. The numbers show the mean and the range of ΩNO2, ΩHCHO, and HCHO/NO2 for each core-based statistical area (CBSA, outlined in black). The red star shows the location with highest ΩNO2 in the CBSA. The red circles in the bottom two rows label the locations of three AQS sites where the highest O3 occurred in the region, and the color represents the summertime mean O3 (color bar inset in bottom right panel). Maps for 2001 – 2004, 2005 – 2008, and 2009 – 2012 are shown in Figure S11.

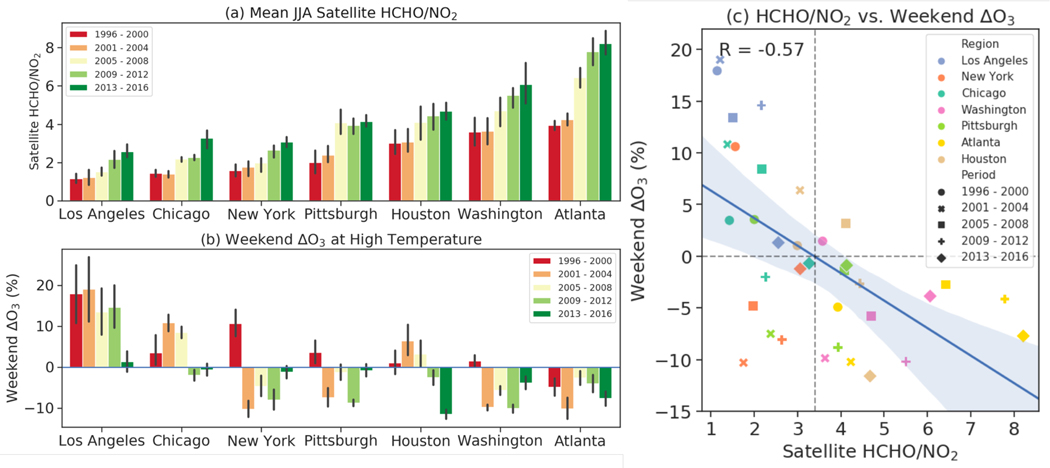

Figure 4.

(a) Satellite-based summertime average HCHO/NO2 in seven cities during five periods. (b)Weekday-to-weekend difference in average 1–2 pm summertime O3 (weekend ΔO3, mean O3 Saturday-Sunday minus mean O3 Tuesday-Friday) within each city at: (b) high temperature (> median summer average temperature 1–2 pm) observed at AQS sites during five periods. Satellite-based HCHO/NO2 is sampled over ground-based AQS O3 sites. The error bars represent year-to-year variability in a given period. (c) Scatter plot between summertime average satellite-based HCHO/NO2 and the weekend ΔO3 with colors representing different cities and symbols representing different periods. The blue line is the fitted linear regression line with the 95% confidence interval shaded.

where is the difference between OMI ΩNO2 and SCIAMACHY ΩNO2 at coarse resolution averaged during the overlap period (n years):

| (2) |

; is the resolution correction factor where xf is the grid cell at fine resolution, and xc is the coarse grid cell where xf falls.

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

To harmonize GOME ΩNO2, we apply the same correction factors that we applied to SCIAMACHY except that the temporal variability in RCNO2 is driven by the variability in RCNO2 of GOME. We do not adjust for any systematic differences between GOME and SCIAMACHY at coarse resolution, because the overpass time is close, and the overlap period (August 2002 to June 2003) does not cover an entire summer.

We similarly decompose the instrumental differences in ΩHCHO to differences caused by resolution (RCHCHO_OMI) versus overpass time (ΔΩHCHO_Coarse). We find that RCHCHO_OMI is much smaller than ΔΩHCHO_Coarse, and the spatial pattern of RCHCHO_OMI tends to be noisy (Figure S5). We find little resolution dependence of the difference between OMI ΩHCHO and SCIAMACHY ΩHCHO, likely due to widespread summertime isoprene emissions, the dominant summertime precursor to HCHO over the U.S., as well as HCHO produced during oxidation of longer-lived VOCs.51 Therefore, we do not apply a resolution correction to SCIAMACHY ΩHCHO or GOME ΩHCHO. We calculate the climatology of the systematic difference between OMI ΩHCHO and SCIAMACHY ΩHCHO at 0.25˚× 0.25˚ resolution, and adjust ΩHCHO (ΩHCHO_adj) by applying these differences to the original SCIAMACHY and GOME ΩHCHO (ΩHCHO_Ori) for the years without OMI observations:

| (7) |

| (8) |

The systematic difference is mainly attributed to the diel cycle in HCHO.54 As we adjust the morning retrieval of HCHO with respect to the afternoon retrieval, upward adjustment is expected due to the diel cycle in temperature, which controls biogenic VOC emissions, and in OH, which controls HCHO production from its parent VOCs (Figure S5).40,55

Connecting Satellite HCHO/NO2 with Ground-based O3 observations.

We use observations of hourly O3 from the U.S. Air Quality System (AQS) from 1996 to 2016. We first aggregate daily OMI data (used in Figure 1) by sampling the gridded daily OMI ΩHCHO and ΩNO2 coincident with ground-based observations of O3 at 0.125˚×0.125˚ resolution. Retrievals from SCIAMACHY and GOME are not used for daily analysis because harmonization at the daily time scale is unrealistic. We average hourly O3 measurements at 1 PM and 2 PM local time to match the OMI overpass time. We first select 1,221 O3 monitors located in polluted regions, defined as summertime 2005–2016 average OMI ΩNO2 > 1.5×1015 molecules/cm2. OMI retrieved ΩNO2 and ΩHCHO are sampled daily over AQS O3 sites for the warm season (May to October) from 2005 to 2016, yielding over 700,000 paired observations, and we calculate the probability of O3 exceeding 70 ppb from this dataset. Next, we focus on seven metropolitan areas to evaluate the satellite-based HCHO/NO2 and study the long-term evolution of O3 production regimes from 1996 to 2016, as the resolution of the harmonized satellite products (~ 10 km) is more suitable for studying cities spanning larger areas. We first select Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, the three most populous cities in the U.S.A. We then include four additional cities: Washington DC, Pittsburgh, Atlanta and Houston, where long-term ground-based observations of O3 and NOx are available, and which also cover different U.S. climate regions. To assess if satellite HCHO/NO2 captures the long-term changes in O3 production regimes, we include ground-based measurements of O3 from 1996 to 2016 in each of the seven cities and their surrounding rural areas, from which we analyze the changes in urban-rural O3 gradient, and the weekday-to-weekend differences defined as weekend (Saturday-Sunday) O3 - weekday (Tuesday-Friday) O3.

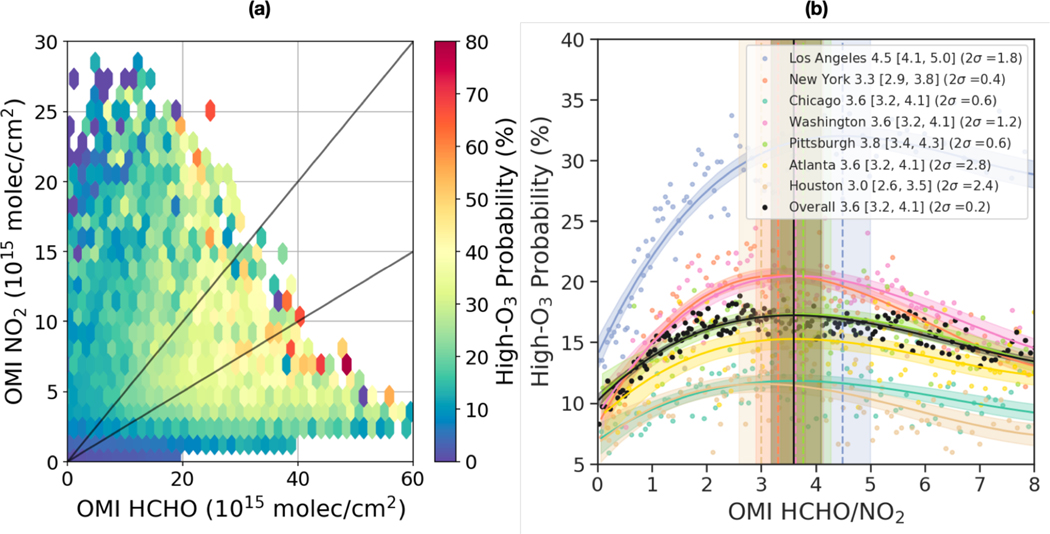

Figure 1.

(a) Probability of O3 exceeding 70 ppbv (high-O3 probability) as a function of OMI ΩNO2 and ΩHCHO. All ground-based hourly O3 observations (averaged at 1 PM and 2 PM local time) in the warm season (May to October) from 2005 to 2016 are first aggregated based on corresponding daily OMI ΩNO2 and ΩHCHO (interval: 0.5 ´ 1015 molecules/cm2). We only include sites over polluted regions (defined as long-term average OMI ΩNO2 > 1.5×1015 molecules/cm2). The probability is the number of observations with O3 higher than 70 ppbv divided by the total number of observations at given OMI ΩNO2 and ΩHCHO. The black lines delineate OMI HCHO/NO2 values of 2 and 4. (b) Probability of O3 exceeding 70 ppbv as a function of OMI HCHO/NO2 for all selected sites (black) and seven cities individually. High-O3 probability is calculated by first matching hourly O3 observations with daily OMI HCHO/NO2, dividing these paired observations to 100 (200 for black dots) bins based on OMI HCHO/NO2, and then calculating the high-O3 probability (y axis) for each OMI HCHO/NO2 bin (x axis, labeled as a dot). The solid lines are fitted third order polynomial curves, and the shading indicates 95% confidence intervals. The vertical lines indicate the maximum of the fitted curve (labeled in the legend), and the vertical shading represents the range over the top 10% of the fitted curve (regime transition). The uncertainty is two standard deviation (2σ or 95% confidence interval) of the derived peaks using statistical bootstrapping by iteratively running the model on 50 randomly selected subsets of 30 data pairs.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Nonlinear O3 Chemistry Captured by Satellite-based HCHO/NO2.

We first evaluate if satellite-based HCHO/NO2 can capture the well-established non-linearities in O3 chemistry. Pusede et al.56 proposed a conceptual framework that uses the observed O3 exceedance probability to interpret the non-linear dependence of O3 production on precursor emissions. This framework assumes stagnant meteorology so that measured O3 is sensitive to its local chemical production, and the local changes in chemical or depositional loss are insignificant on average. We follow this approach by calculating the probability that surface O3 exceeds 70 ppbv (high-O3 probability) at OMI overpass, given the OMI ΩNO2 and ΩHCHO (Figure 1a). Figure 1a, derived solely from observations, resembles O3 isopleths that are typically generated with analytical models.4,57 Consistent with O3 isopleths, three regimes can be roughly identified from Figure 1a: (1) high ΩNO2 and low ΩHCHO, where high O3 events become more likely at lower NOx, indicating NOx-saturated (or VOC-limited) chemistry; (2) low ΩNO2 and relatively high ΩHCHO, where the probability of high O3 events increases with ΩNO2, indicating NOx-limited chemistry; (3) high ΩNO2 and high ΩHCHO, where the probability of high-O3 events peaks, and increases with both ΩNO2 and ΩHCHO. While Figure 1a resembles this overall O3-NOx-VOC chemistry, the high O3 probabilities span a broad range, with an uncertain, blurry transition between NOx-limited and VOC-limited regimes. The lack of sharp transitions between O3 production regimes in Figure 1a likely reflects the influence from other factors such as varying meteorology, chemical and depositional loss of O3, noisy satellite retrievals, the spatial mismatch between the area satellite observations and the point measurements of surface O3, and in some cases, small sample size that lacks statistical power to calculate high-O3 probability. Despite these uncertainties, Figure 1a qualitatively illustrates the non-linear relationship between the occurrence probability of high-O3 events and the HCHO and NO2 proxies for precursor VOC and NOx, respectively.

Having established this qualitative approach, we next derive quantitative relationships by calculating high-O3 probabilities at given OMI HCHO/NO2 and examining their statistical relationship across different U.S. cities. We investigate three possible empirical relationships by applying moving average, second-order polynomial and third-order polynomial models to observations over seven U.S. cities (Figure S6). The third-order polynomial model is used to derive the maximum high-O3 probability (the peak of the curve in Figure 1b), because it best fits data, with the smallest uncertainty (estimated with statistical bootstrapping, Figure S6) and higher correlation coefficient (R) than second-order model. Assuming that the peak of the curve marks the transition from VOC-limited to NOx-limited regime,56 we define the transitional regime as the range of HCHO/NO2 spanning the top 10% of the high-O3 probability distribution.

Aggregating over all available observations used in Figure 1a, we find that the high-O3 probability peaks at HCHO/NO2 = 3.6, with the transitional regime ranging from 3.2 to 4.1, hereafter as [3.2, 4.1]. Evaluating the relationship for the seven cities individually, we find robust non-linear relationships between the high-O3 probability and OMI HCHO/NO2, despite differences in the overall high-O3 probability, which reflect other factors such as emissions, meteorology, and transport. The HCHO/NO2 marking the regime transition varies slightly among these cities, which is highest for LA (4.5 [4.1, 5.0]), and lowest for Houston (3.0 [2.6, 3.5]). We evaluate the uncertainty in the derived peaks using statistical bootstrapping by iteratively applying the model to 50 randomly selected subsets of the data. We define the uncertainty as two standard deviation (2σ or 95% confidence interval) the derived maxima. The uncertainty is generally within 2 except for Atlanta (2σ = 2.8) and Houston (2σ = 2.4), where the fitted curve is relatively flat. Separating the observations into two periods (before and after 2009), the derived thresholds are slightly higher in the later period, which may reflect more high HCHO/NO2 values in the recent period, which drive the curve to move towards a higher turning point, but the uncertainty also increases as we halve the number of observations (Figure S7).

The HCHO/NO2 thresholds derived in Figure 1b are higher than previously reported model-based values,16,17,19 implying that at the same HCHO/NO2, our observation-based approach suggests O3 production is more VOC-limited. The difference originates from the distinct approaches used to link HCHO/NO2 with O3 production regimes. Previous modeling studies derive the threshold by simulating the response of surface O3 to an overall reduction in NOx or NMVOC emissions with coarse resolution models, which best capture regional as opposed to local O3-NOx-VOC sensitivity.16,19 Our thresholds derived with in situ observations should be more indicative of the local O3 chemistry, including the effect of NOx titration over urban areas. Schroeder et al.21 also found VOC-limited chemistry occurring at high HCHO/NO2 (1.3 ~ 5.0) in their analysis of column HCHO/NO2 from aircraft measurements.

Declining NO2 Over Time.

Figure 2a shows summertime average ΩNO2 over seven metropolitan areas in 1996 – 2000 versus 2013 – 2016 produced from the harmonized multi-satellite data. NO2 is concentrated over urban areas and near combustion sources. Applying the resolution corrections to GOME NO2 reveals spatial gradients not detected directly with the coarse resolution of GOME (Figure S8). We find the largest urban-rural gradients in NYC and LA, where ΩNO2 varies by a factor of ten within their core-based statistical areas (CBSA, outlined in Figure 2). Satellite observations show large decreases in ΩNO2 over the past two decades, consistent with previous studies (Figure 2a).7,52,58 The mean ΩNO2 in each CBSA has decreased by 40% (Atlanta) to 56% (LA) in 2013 – 2016 relative to 1996 – 2000. We use ground-based measurements of NOx to evaluate the long-term changes of satellite-based ΩNO2, since our approach assumes ΩNO2 is a good indicator of ground-level NOx. Satellite-based ΩNO2 captures the decrease of ground-level NOx over LA, Chicago, and Washington to within 5%, but underestimates the decrease over NYC, Pittsburgh, and Houston, while overestimates the decreases in Atlanta (Figure S9). Both satellite-based ΩNO2 and ground-level NOx show the largest decline before 2004 over Pittsburgh, associated with emission controls on coal-fired power plants.59,60 Satellite-based ΩNO2 does not show decreases over NYC and Houston before 2000, but ground-based NOx suggests large decreases (Figure S10). This discrepancy is likely due to the coarse resolution of GOME; while we have corrected the spatial patterns of GOME ΩNO2, the total ΩNO2 may still be biased low, due to the contributions from the nearby ocean where NO2 is low. Satellite-based ΩNO2 does capture the large decreases between 2005 and 2012 in NYC and Houston (Figure S10). Over LA, Chicago, Washington and Atlanta, both satellite and ground-based observations suggest the largest reductions occurred between 2005 to 2012 (Figure S10), when emission controls on power plants and stricter vehicle emission standards were implemented.26,61 The substantial decrease in 2008 – 2010 may also reflect the economic recession.7,61 In the most recent period (2013 – 2016), satellite data show flattening trends in ΩNO2 in all seven cities (Figure S10), possibly related to a slowdown of NOx emission reductions,29 changes in NOx lifetime,28 and the relatively larger influence of upper tropospheric NO2 as anthropogenic contributions declines.22

Heterogeneous Trends of HCHO.

Figure 2b compares summertime multi-satellite ΩHCHO in 1996 – 2000 versus 2013 – 2016. The spatial patterns of HCHO over the U.S. are largely driven by variations in biogenic VOCs, especially isoprene, which is mainly emitted from broadleaf trees, and is most abundant in the southeastern USA.53 As expected, the mean ΩHCHO is highest over the southeastern city of Atlanta, followed by Washington and NYC. ΩHCHO shows strong inter-annual variability (Figure S12), driven by inter-annual variability of meteorology, temperature in particular.55,62 Over urban areas, satellite-based ΩHCHO decreased by 7% in LA, 4% in NYC, 3% in Pittsburgh, 4% in Atlanta and 3% in Houston in 2013 – 2016 relative to 1996 – 2000 (Figure S9), consistent with the widespread reduction of anthropogenic VOC emissions.25 Over surrounding rural areas, satellite-based ΩHCHO decreased near LA, Washington, Atlanta, and Houston, but increased near New York, Chicago, and Pittsburgh. These changes in ΩHCHO correspond to estimated long-term changes in isoprene emissions (Figure S13), which have previously been shown to be related to changes in vegetation coverage.63 In addition, NOx reductions could lead to lower the HCHO yield from isoprene oxidation,64,65 but the available observations are insufficient to conclusively determine the changes in HCHO yield. Overall, long-term changes in HCHO are driven by several factors,66 such as anthropogenic and biogenic emissions, OH abundance, and HCHO yield dependence on NOx, which warrant further investigation as more measurements become more available.67 Most relevant to our study is that the overall changes in HCHO are much smaller than the NO2 changes over the last two decades (Figure 2).

Spatial Expansion of NOx-limited Regime Over Time.

As ΩNO2 decreased over time, while changes in ΩHCHO were relatively small, satellite-based HCHO/NO2 increased from 1996 – 2000 to 2013 – 2016, indicating a shrinking extent of NOx-saturated O3 formation in urban areas (Figure 2c). Using the thresholds derived from Figure 1b to identify the O3 production regimes, NOx-saturated chemistry existed during summer in all cities during 1996 – 2000, with the largest areal extent in Pittsburgh. By 2013 – 2016, NOx-saturated chemistry only occurred in the center of LA, Chicago and NYC. The spatial expansion of the NOx-limited regime suggests that NOx emission reductions are more effective today at reducing O3 pollution, as confirmed from prior modeling35,36,68 and ground-based observational studies.34,56 In recent years, as ΩNO2 remains at low levels, ΩHCHO plays a more important role in determining the spatial and temporal variability in HCHO/NO2. For example, the mean ΩHCHO over LA is 8.2 × 1015 molecules/cm2 in 2010, but increases to 15.2 × 1015 molecules/cm2 in 2011, leading to the mean O3 formation regime to shift from NOx-saturated to NOx-limited (Figure S14). Also, Atlanta and Pittsburgh show similar ΩNO2 in 2013 – 2016, but ΩHCHO is 50% higher in Atlanta, leading to 76% higher HCHO/NO2 and thus more NOx-limited chemistry in Atlanta, consistent with the well-understood regional differences in summertime O3 sensitivity.69,70

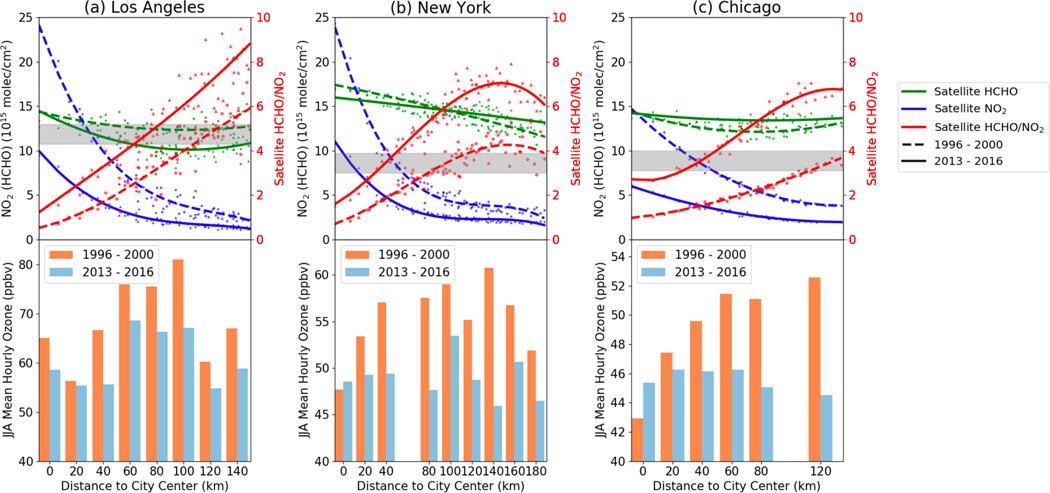

LA, NYC and Chicago are the three cities where we find strong urban-rural gradients in HCHO/NO2, where O3 production transitions from NOx-saturated at city centers towards a NOx-limited regime over rural areas in both periods. Figure 3 shows summertime average satellite-based NO2, HCHO and HCHO/NO2 as a function of the distance to the city center during 1996 – 2000 and 2013 – 2016 over these three cities. Satellite observations detect large urban-rural gradients of NO2 in LA and NYC with 20 × 1013 molecules/cm2/km in 1996 – 2000, which decrease to 8 × 1013 molecules/cm2/km in 2013 to 2016. The urban-rural gradient has decreased from 11 × 1013 molecules/cm2/km to 3 × 1013 molecules/cm2/km in Chicago. We find a small enhancement of ΩHCHO in urban areas over NYC and LA of 2 to 3 × 1013 molecules/cm2/km, and negligible urban-rural difference of ΩHCHO in Chicago. The urban-rural gradient of OMI HCHO/NO2 is therefore mainly driven by the variations in NO2. Using the regime thresholds we estimated, we infer the regime transition occurred at 110 to 130 km away from the city center in LA, 80 to 120 km in NYC, and 120 to 130 km in Chicago in 1996 – 2000. By 2013 – 2016, the locations of regime transition have moved closer to the city centers: 50 to 70 km for LA, 40 to 60 km for NYC and 30 to 60 km for Chicago (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Satellite-based summertime ΩNO2 (blue dots), ΩHCHO (green dots), HCHO/NO2 (red dots) and summertime average O3 (bars) as a function of distance to the city center during 1996 – 2000 and 2013 – 2016 for three cities: (a) Los Angeles, (b) New York, and (c) Chicago. City center is defined as the grid cell with highest summertime ΩNO2 within this region (labeled as red stars in Figure 2), which we find do not change over time in these cities (Figures 2 and S11). The curves shown in the top row are a polynomial fit (third order for ΩNO2 and HCHO/NO2, second order for ΩHCHO) curves. The gray area indicates the regime transitions for HCHO/NO2, which is derived for each city individually as shown in Figure 1b. Summertime average O3 is calculated from hourly AQS observations at OMI overpass time (averaged at 1 PM and 2 PM local time). AQS O3 sites are grouped by distance to the city center at 20 km intervals.

Observed Response of Ground-level O3 to Regime Transitions.

Theoretically, O3 production regime transitions should correspond to the conditions at which O3 formation is most efficient.57 As the regime transition moves closer to populated city centers, peak O3 production efficiency is expected to move towards the city center. We hypothesize that we should observe the highest O3 concentration where the transitional regime occurs, assuming that local changes in meteorology, chemical and depositional loss do not contribute strongly to the observed summertime mean urban-to-rural O3 gradients. We find that the ground-based sites measuring the highest summertime mean O3 in each region move towards the city centers over time, except for Atlanta and Houston, where the highest O3 is found near the city center in both periods (Figure 2c). We aggregate ground-based O3 sites based on their distance to the city center for LA, NYC and Chicago (Figure 3), where the VOC-limited regime still existed in 2013 – 2016. As expected, peak O3 has moved towards the city center from 1996 – 2000 to 2013 – 2016 in LA and Chicago: from ~100 km to ~60 km in LA, from 120 km to 20 km in Chicago. The locations of peak O3 are largely consistent with the locations of the regime transition identified by the satellite-based HCHO/NO2. In NYC, we find that O3 peaks ~140 km away in 1996 – 2000, which is consistent with the regime transition inferred from satellite-based HCHO/NO2. In 2013 – 2016, O3 shows peaks at 100 and 160 km, however, which may be due to the non-circular nature of city shape and possibly confounding role of nearby ocean. If we only consider the small region within 100 km, O3 peaks at 40 km away from the city center, more consistent with the regime transition inferred from satellite-based HCHO/NO2.

Regionally, surface O3 in summer has decreased over the past two decades over the USA, especially over the eastern USA.30,33,71,72 As expected, summertime mean O3 is smaller in 2013 – 2016 than 1996 – 2000 over the three megacities, but the reduction is larger over rural areas where O3 formation falls in the NOx-limited regime (Figure 3). The faster decline in O3 over rural areas than urban areas has previously been demonstrated.33 In NYC and Chicago, we find an increase in O3 at the city center where O3 formation is NOx-saturated. In the NOx-saturated regime, NOx emission reductions decrease NOx titration, which increases O3 directly, and also increases OH available for VOC oxidation and subsequent O3 production. The spatial difference between maximum and minimum O3 narrows from 13 ppbv in 1996 – 2000 to 7 ppbv in 2013 – 2016 in NYC, and 10 ppbv to 2 ppbv in Chicago. In LA, O3 decreases in urban areas, which we attribute to decrease in anthropogenic VOC emissions.73 The largest O3 decreases occur in the transitional regimes in LA, where reductions in both anthropogenic VOCs and NOx lower O3.

Reversal of the O3 Weekend Effect.

The decrease of urban NOx emissions associated with road traffic on weekends provides an observation-based natural test for investigating O3 sensitivity to NOx emissions;74,75 over urban areas where O3 formation is NOx-saturated, reduction of NOx emissions on weekends increases in O3 (referred to as the O3 weekend effect). Figure 4 shows the mean satellite-based HCHO/NO2 sampled over long-term O3 sites for the seven selected cities in five periods, and the corresponding in situ observed weekday-to-weekend difference in average summertime O3 (weekend ΔO3) within each metropolitan area. Here we only select days with high temperature (> median summertime average), as they are generally associated with high pressure, clearer skies and slower winds, conditions suitable for efficient O3 production.37,57 As O3 production becomes more sensitive to NOx, the weekend ΔO3 lessens and even reverses in some cities. The extent of the NOx-saturated regime is largest in LA, as suggested by the lowest average satellite HCHO/NO2 (Figure 4a). The O3 weekend effect in LA persists from 1996 to 2016, but is smallest in the most recent period. During 1996 – 2000, we find a positive weekend ΔO3 in 18 (11 with p < 0.1) out of 20 sites along southern California (Figure S15), but only 11 out of 18 sites (5 with p < 0.1) during 2013 – 2016. The shrinking O3 weekend effect after 2000 in LA is reported in previous studies.76,77 Chicago has the second lowest HCHO/NO2, and the weekend ΔO3 changes from positive to negative in 2009 – 2012. Over Chicago, the O3 weekend effect is strongest during 2001 – 2004, when 32 out of 34 sites show positive weekend ΔO3, and diminishes to 10 out of 23 sites during 2013 – 2016 (Figure S15). The reversal of O3 weekend effect occurs earlier in 2001 – 2004 over NYC, Pittsburgh, and Washington, though satellite HCHO/NO2 does not change much compared with 1996 – 2000. In Houston, we find the reversal of weekend ΔO3 occurs around 2009 – 2012. In Houston, 17 out of 24 sites show positive weekend ΔO3 on weekends during 2001 – 2004, but they all changed sign during 2013 – 2016 (Figure S15). In Atlanta, where O3 formation is most NOx-limited based on our metric, O3 concentration remains lower on weekends than weekdays at high temperature, but a reversal of the O3 weekend effect does occur at moderate temperature during 2005 – 2008 (Figure S16).

The observed long-term changes in the O3 weekend effect are overall consistent with the increasing sensitivity to NOx, as suggested by the increasing satellite-based HCHO/NO2 (Figure 4a). We find that satellite-based HCHO/NO2 and weekend ΔO3 is moderately correlated (R = −0.57, p < 0.001, Figure 4c). The regression line intercepts 0 at HCHO/NO2 = 3.4, which is close to the regime transition derived in Figure 1b. Using this satellite-based indicator to quantitatively predict the occurrence of O3 weekend effect in any particular city for a given time period, however, is subject to uncertainties. The definition of the O3 weekend effect we invoke here assumes that the only difference in O3 is directly attributable to changes in NOx emission. The observed O3 differences, however, may also be influenced by variability in meteorology.42,78 The early reversal of the O3 weekend effect in 2001 – 2004 over northeastern cities (NYC, Washington and Pittsburgh) is better explained by the overall colder temperature on weekends than weekdays over these three cities (Figure S17). Pierce et al.42 suggest the long-term trend in the O3 weekend effect over the northeast USA is strongly influenced by the inter-annual variability in meteorology. We find larger fluctuations of the weekend ΔO3 at moderate temperatures in most cities except for LA (Figure S16), which may be related to meteorological conditions that act to weaken urban-to-rural gradients through regional-scale O3 transport that dilutes the signal of local urban O3 production.

Limitations and Future Directions.

Our study is the first attempt to directly connect satellite-based HCHO/NO2 with ground-based O3 observations. We show that space-based HCHO/NO2 captures the nonlinearities of O3-NOx-VOC chemistry, and the detected spatial expansion of the NOx-limited regime is supported by ground-based observations. However, using satellite HCHO/NO2 to quantitatively diagnose the effectiveness of emission controls is subject to following uncertainties that warrant further investigation. First, theoretical studies that relate indicator ratio to O3-NOx-VOC sensitivity show variations among different locations, which are subject to uncertainties of deposition and interactions with aerosol.14,79 Second, satellite instruments measure the vertically integrated column density, and inhomogeneities in vertical distributions degrade the ability of satellite-based column HCHO/NO2 to identify the near-surface O3 sensitivity.19,21 Third, we use an empirical observation-based approach to derive the thresholds making the transitions between chemical regimes, which are likely to be affected by not only biases in the satellite retrieval algorithms,19 but also by sampling size and biases of both ground-based and space-based observations. Fourth, the extent to which satellite-based ΩHCHO relates to local surface organic reactivity is unclear. Satellite-based ΩHCHO shows small decreasing trends over urban areas, and are mostly insensitive to observed decreases in anthropogenic VOCs,56,73 partially due to relatively small HCHO yields from some classes of anthropogenic VOCs (e.g. alkanes).80 As HCHO is a weaker UV-Visible absorber than NO2, satellite retrieval of HCHO is more prone to errors,46 which may limit its ability to detect HCHO from local sources of anthropogenic VOCs. We find small enhancements of satellite ΩHCHO over urban areas, but the magnitudes of the enhancement are insensitive to resolution, suggesting satellite ΩHCHO is more indicative of the regional VOC reactivity, which is mainly influenced by biogenic isoprene emissions across much of the U.S.A. in summer.81 Finally, although the retrieval uncertainty associated with different instruments has largely been reduced in the QA4ECV products,49 our applications of satellite-based HCHO/NO2 are nonetheless limited to long-term averages or data aggregations sufficiently large sample sizes to reduce retrieval noise. It is challenging to use current satellite retrievals to observe short-term variability and detailed spatial patterns within urban cores. The new generation of satellites, including the newly launched TROPOMI aboard Sentinel-5P, and the upcoming geostationary satellite instruments such as TEMPO will offer an unprecedented view to characterize the near-surface O3 chemistry at finer spatial and temporal scales.82,83

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Support for this project was provided by the NASA Earth and Space Science Fellowship (NESSF, Grant 80NSSC18K1399), and NASA Atmospheric Composition Modeling and Analysis Program (ACMAP, Grant NNX17AG40G). We acknowledge useful discussions with Bryan Duncan (NASA GSFC), Lok Lamsal (NASA GSFC) and Melanie Follette-Cook (Morgan State University).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Details on satellite retrieval of NO2 and HCHO (S1); gridding of satellite products (S2); discussion on the choice of resolution (S3); difference between OMI and SCIAMACHY ΩNO2 (Figure S1); resolution correction factor for ΩNO2 (Figure S2); year-to-year variability in RCNO2_OMI (Figure S3); temporal correlation between RCNO2_OMI and RCNO2_SCIA (Figure S4); resolution correction of OMI ΩHCHO and systematic difference between OMI and SCIAMACHY ΩHCHO (Figure S5); Figure 1b for comparison of multiple models (Figure S6); Figure 1b for comparison of two periods (Figure S7); resolution corrected versus original GOME ΩNO2 (Figure S8); Relative changes in summertime average satellite-based ΩNO2 and ground-based measurements of NOx, ΩHCHO over urban and rural areas (Figure S9); time series of satellite-based ΩNO2 and ground-based NOx (Figure S10); Figure 2 for the other three periods (Figure S11); time series of satellite-based ΩHCHO (Figure S12); long-term changes in biogenic isoprene emissions (Figure S13); time series of satellite-based HCHO/NO2 (Figure S14); maps of O3 weekend effect (Figure S15); Figure 4(b) for moderate temperature (Figure S16); weekday-to-weekend difference in temperature (Figure S17).

Notes

The views, opinions, and findings contained in this report are those of the author(s) and should not be construed as an official U.S. Environmental Protection Agency position, policy, or decision.

REFERENCES

- (1).Jerrett M; Burnett RT; Pope CAI; Ito K; Thurston G; Krewski D; Shi Y; Calle E; Thun M. Long-Term Ozone Exposure and Mortality. N Engl J Med 2009, 360 (11), 1085–1095. 10.1056/nejmoa0803894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Cohen AJ; Brauer M; Burnett R; Anderson HR; Frostad J; Estep K; Balakrishnan K; Brunekreef B; Dandona L; Dandona R; Feigin V; Freedman G; Hubbell B; Jobling A; Kan H; Knibbs L; Liu Y; Martin R; Morawska L; III CAP; Shin H; Straif K; Shaddick G; Thomas M; Dingenen RV; Donkelaar A. van; Vos T; Murray CJL; Forouzanfar MH Estimates and 25-Year Trends of the Global Burden of Disease Attributable to Ambient Air Pollution: An Analysis of Data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. The Lancet 2017, 389 (10082), 1907–1918. 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30505-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kleinman LI Low and High Nox Tropospheric Photochemistry. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 1994, 99 (D8), 16831–16838. 10.1029/94jd01028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Sillman S; Logan JA; Wofsy SC The Sensitivity of Ozone to Nitrogen Oxides and Hydrocarbons in Regional Ozone Episodes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres (1984–2012) 1990, 95 (D2), 1837–1851. 10.1029/jd095id02p01837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Martin RV; Jacob DJ; Chance K; Kurosu T; Palmer PI; Evans MJ Global Inventory of Nitrogen Oxide Emissions Constrained by Space-Based Observations of NO2 Columns. Journal of Geophysical Research 2003, 108 (D17), 955. 10.1029/2003jd003453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Lamsal LN; Krotkov NA; Celarier EA; Swartz WH; Pickering KE; Bucsela EJ; Gleason JF; Martin RV; Philip S; Irie H; Cede A; Herman J; Weinheimer A; Szykman JJ; Knepp TN Evaluation of OMI Operational Standard NO2 Column Retrievals Using in Situ and Surface-Based NO2 Observations. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2014, 14 (21), 11587–11609. 10.5194/acp-14-11587-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Lamsal LN; Duncan BN; Yoshida Y; Krotkov NA; Pickering KE; Streets DG; Lu ZUS NO2 Trends (2005–2013): EPA Air Quality System (AQS) Data versus Improved Observations from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI). Atmospheric Environment 2015, 110 (C), 130–143. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.03.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Palmer PI; Jacob DJ; Fiore AM; Martin RV; Chance KV; Kurosu TP Mapping isoprene emissions over North America using formaldehyde column observations from space. J. Geophys. Res. 2003, 108 (D6), 155. 10.1029/2002jd002153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Fu T-M; Jacob DJ; Palmer PI; Chance K; Wang YX; Barletta B; Blake DR; Stanton JC; Pilling MJ Space-Based Formaldehyde Measurements as Constraints on Volatile Organic Compound Emissions in East and South Asia and Implications for Ozone. Journal of Geophysical Research 2007, 112 (D6), D06312. 10.1029/2006jd007853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Millet DB; Jacob DJ; Boersma KF; Fu T-M; Kurosu TP; Chance K; Heald CL; Guenther A. Spatial Distribution of Isoprene Emissions from North America Derived from Formaldehyde Column Measurements by the OMI Satellite Sensor. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres (1984–2012) 2008, 113 (D2), D02307. 10.1029/2007jd008950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Marais EA; Jacob DJ; Kurosu TP; Chance K; Murphy JG; Reeves C; Mills G; Casadio S; Millet DB; Barkley MP; Paulot F; Mao J. Isoprene Emissions in Africa Inferred from OMI Observations of Formaldehyde Columns. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2012, 12 (14), 6219–6235. 10.5194/acp-12-6219-2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zhu L; Jacob DJ; Mickley LJ; Marais EA; Cohan DS; Yoshida Y; Duncan BN; Abad GG; Chance KV Anthropogenic Emissions of Highly Reactive Volatile Organic Compounds in Eastern Texas Inferred from Oversampling of Satellite (OMI) Measurements of HCHO Columns. Environmental Research Letters 2014, 9 (11), 114004–114008. 10.1088/1748-9326/9/11/114004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Shen L; Jacob DJ; Zhu L; Zhang Q; Zheng B; Sulprizio MP; Li K; Smedt ID; Abad GG; Cao H; Fu T-M; Liao H. The 2005–2016 Trends of Formaldehyde Columns Over China Observed by Satellites: Increasing Anthropogenic Emissions of Volatile Organic Compounds and Decreasing Agricultural Fire Emissions. Geophysical Research Letters 2019, 46 (8), 4468–4475. 10.1029/2019gl082172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Sillman S. The Use of NOy, H2O2, and HNO3 as Indicators for Ozone‐NOx ‐hydrocarbon Sensitivity in Urban Locations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres (1984–2012) 1995, 100 (D7), 14175–14188. 10.1029/94jd02953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Tonnesen GS; Dennis RL Analysis of Radical Propagation Efficiency to Assess Ozone Sensitivity to Hydrocarbons and NOx: 2. Long‐lived Species as Indicators of Ozone Concentration Sensitivity. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres (1984–2012) 2000, 105 (D7), 9227–9241. 10.1029/1999jd900372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Martin RV; Fiore AM; Donkelaar A. van. Space-Based Diagnosis of Surface Ozone Sensitivity to Anthropogenic Emissions. Geophysical Research Letters 2004, 31 (6), L06120. 10.1029/2004gl019416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Duncan BN; Yoshida Y; Olson JR; Sillman S; Martin RV; Lamsal L; Hu Y; Pickering KE; Allen DJ; Retscher C; Crawford JH Application of OMI Observations to a Space-Based Indicator of NOx and VOC Controls on Surface Ozone Formation. Atmospheric Environment 2010, 44 (18), 2213–2223. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Jin X; Holloway T. Spatial and Temporal Variability of Ozone Sensitivity over China Observed from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2015, 120 (14), 7229–7246. 10.1002/2015jd023250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Jin X; Fiore AM; Murray LT; Valin LC; Lamsal LN; Duncan B; Boersma KF; Smedt ID; Abad GG; Chance K; Tonnesen GS Evaluating a Space-Based Indicator of Surface Ozone-NOx-VOC Sensitivity Over Midlatitude Source Regions and Application to Decadal Trends. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2017, 110 (9), D11303–23. 10.1002/2017jd026720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Brown-Steiner B; Hess PG; Lin MY On the Capabilities and Limitations of GCCM Simulations of Summertime Regional Air Quality: A Diagnostic Analysis of Ozone and Temperature Simulations in the US Using CESM CAM-Chem. Atmospheric Environment 2015, 101 (C), 134–148. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Schroeder JR; Crawford JH; Fried A; Walega J; Weinheimer A; Wisthaler A; Müller M; Mikoviny T; Chen G; Shook M; Blake DR; Tonnesen GS New Insights into the Column CH2O/NO2 Ratio as an Indicator of near-Surface Ozone Sensitivity. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2017, 122 (16), 8885–8907. 10.1002/2017jd026781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Silvern RF; Jacob DJ; Mickley LJ; Sulprizio MP; Travis KR; Marais EA; Cohen RC; Laughner JL; Choi S; Joiner J; Lamsal LN Using Satellite Observations of Tropospheric NO2 Columns to Infer Long-Term Trends in US NOx Emissions: The Importance of Accounting for the Free Tropospheric NO2 Background. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2019, 19 (13), 8863–8878. 10.5194/acp-19-8863-2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wang K; Yahya K; Zhang Y; Hogrefe C; Pouliot G; Knote C; Hodzic A; Jose RS; Perez JL; Jiménez-Guerrero P; Baro R; Makar P; Bennartz R. A Multi-Model Assessment for the 2006 and 2010 Simulations under the Air Quality Model Evaluation International Initiative (AQMEII) Phase 2 over North America: Part II. Evaluation of Column Variable Predictions Using Satellite Data. Atmospheric Environment 2014, 115, 1–17. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.07.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Zhu L; Jacob DJ; Kim PS; Fisher JA; Yu K; Travis KR; Mickley LJ; Yantosca RM; Sulprizio MP; Smedt ID; Abad GG; Chance K; Li C; Ferrare R; Fried A; Hair JW; Hanisco TF; Richter D; Scarino AJ; Walega J; Weibring P; Wolfe GM Observing Atmospheric Formaldehyde (HCHO) from Space: Validation and Intercomparison of Six Retrievals from Four Satellites (OMI, GOME2A, GOME2B, OMPS) with SEAC4RS Aircraft Observations over the Southeast US. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2016, 16 (21), 13477–13490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).EPA OU Air Pollutant Emissions Trends Data. 2018. https://www.epa.gov/air-emissions-inventories/air-pollutant-emissions-trends-data

- (26).Duncan BN; Lamsal LN; Thompson AM; Yoshida Y; Lu Z; Streets DG; Hurwitz MM; Pickering KE A Space-Based, High-Resolution View of Notable Changes in Urban NOx Pollution around the World (2005–2014). Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2016, 121 (2), 976–996. 10.1002/2015jd024121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Georgoulias AK; A, an der RJ; Stammes P; Boersma KF; Eskes HJ Trends and Trend Reversal Detection in 2 Decades of Tropospheric NO2 Satellite Observations. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2019, 19 (9), 6269–6294. 10.5194/acp-19-6269-2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Laughner JL; Cohen RC Direct Observation of Changing NOx Lifetime in North American Cities. science 2019, 366 (6466), 723–727. 10.1126/science.aax6832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Jiang Z; McDonald BC; Worden H; Worden JR; Miyazaki K; Qu Z; Henze DK; Jones DBA; Arellano AF; Fischer EV; Zhu L; Boersma KF Unexpected Slowdown of US Pollutant Emission Reduction in the Past Decade. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115 (20), 5099–5104. 10.1073/pnas.1801191115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Chang K-L; Petropavlovskikh I; Cooper OR; Schultz MG; Wang T. Regional Trend Analysis of Surface Ozone Observations from Monitoring Networks in Eastern North America, Europe and East Asia. Elem Sci Anth 2017, 5 (0), 1–22. 10.1525/elementa.243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Yan Y; Lin J; He C. Ozone Trends over the United States at Different Times of Day. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2018, 18 (2), 1185–1202. 10.5194/acp-18-1185-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Blanchard CL; Shaw SL; Edgerton ES; Schwab JJ Emission Influences on Air Pollutant Concentrations in New York State_ I. Ozone. Atmospheric Environment: X 2019, 3, 100033. 10.1016/j.aeaoa.2019.100033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Simon H; Reff A; Wells B; Xing J; Frank N Ozone Trends Across the United States over a Period of Decreasing NOx and VOC Emissions. Environmental Science & Technology 2015, 49 (1), 186–195. 10.1021/es504514z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Blanchard CL; Hidy GM Ozone Response to Emission Reductions in the Southeastern United States. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2018, 18 (11), 8183–8202. 10.5194/acp-18-8183-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Henneman LRF; Shen H; Liu C; Hu Y; Mulholland JA; Russell AG Responses in Ozone and Its Production Efficiency Attributable to Recent and Future Emissions Changes in the Eastern United States. Environmental Science & Technology 2017, 51 (23), 13797–13805. 10.1021/acs.est.7b04109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).He H; Liang X-Z; Sun C; Tao Z; Tong DQ The Long-Term Trend and Production Sensitivity Change in the US Ozone Pollution from Observations and Model Simulations. Atmos Chem Phys 2020, 20 (5), 3191–3208. 10.5194/acp-20-3191-2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Pusede SE; Gentner DR; Wooldridge PJ; Browne EC; Rollins AW; Min KE; Russell AR; Thomas J; Zhang L; Brune WH; Henry SB; DiGangi JP; Keutsch FN; Harrold SA; Thornton JA; Beaver MR; Clair JMS; Wennberg PO; Sanders J; Ren X; VandenBoer TC; Markovic MZ; Guha A; Weber R; Goldstein AH; Cohen RC On the Temperature Dependence of Organic Reactivity, Nitrogen Oxides, Ozone Production, and the Impact of Emission Controls in San Joaquin Valley, California. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2014, 14 (7), 3373–3395. 10.5194/acp-14-3373-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Rasmussen DJ; Hu J; Mahmud A; Kleeman MJ The Ozone–Climate Penalty: Past, Present, and Future. Environmental Science & Technology 2013, 47 (24), 14258–14266. 10.1021/es403446m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).McDonald BC; Gentner DR; Goldstein AH; Harley RA Long-Term Trends in Motor Vehicle Emissions in U.S. Urban Areas. Environmental Science & Technology 2013, 47 (17), 10022–10031. 10.1021/es401034z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Guenther AB; Jiang X; Heald CL; Sakulyanontvittaya T; Duhl T; Emmons LK; Wang X The Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature Version 2.1 (MEGAN2.1): An Extended and Updated Framework for Modeling Biogenic Emissions. Geoscientific Model Development 2012, 5 (6), 1471–1492. 10.5194/gmd-5-1471-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Vukovich FM Regional-Scale Boundary Layer Ozone Variations in the Eastern United States and Their Association with Meteorological Variations. Atmospheric Environment 1995, 29 (17), 2259–2273. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Pierce T; Hogrefe C; Rao ST; Porter PS; Ku J-Y Dynamic Evaluation of a Regional Air Quality Model: Assessing the Emissions-Induced Weekly Ozone Cycle. Atmospheric Environment 2010, 44 (29), 3583–3596. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.05.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Boersma F; Eskes H; Richter A; Smedt ID; Lorente A; Beirle S; Geffen J. van; Peters E; Roozendael MV; Wagner T QA4ECV NO2 Tropospheric and Stratospheric Column Data from OMI. Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Smedt ID; Yu H; Richter A; Beirle S; Eskes H; Boersma F; Roozendael MV; Geffen J. van; Lorente A; Peters E QA4ECV HCHO Tropospheric Column Data from OMI. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Boersma F; Eskes H; Richter A; Smedt ID; Lorente A; Beirle S; Geffen J. van; Peters E; Roozendael MV; Wagner T QA4ECV NO2 Tropospheric and Stratospheric Column Data from GOME. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Boersma F; Eskes H; Richter A; Smedt ID; Lorente A; Beirle S; Geffen J. van; Peters E; Roozendael MV; Wagner T QA4ECV NO2 Tropospheric and Stratospheric Column Data from SCIAMACHY. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Lorente A; Boersma KF; Yu H; Dörner S; Hilboll A; Richter A; Liu M; Lamsal LN; Barkley M; Smedt ID; Roozendael MV; Wang Y; Wagner T; Beirle S; Lin JT; Krotkov N; Stammes P; Wang P; Eskes HJ; Krol M Structural Uncertainty in Air Mass Factor Calculation for NO2 and HCHO Satellite Retrievals. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2017, 10 (3), 759–782. 10.5194/amt-10-759-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (48).De Smedt I; Theys N; Yu H; Danckaert T; Lerot C; Compernolle S; Roozendael MV; Richter A; Hilboll A; Peters E; Pedergnana M; Loyola D; Beirle S; Wagner T; Eskes H; Geffen J.van ; Boersma KF; Veefkind P Algorithm Theoretical Baseline for Formaldehyde Retrievals from S5P TROPOMI and from the QA4ECV Project. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques Discussions 2018, 11 (4), 2395–2426. 10.5194/amt-11-2395-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Zara M; Boersma KF; Smedt ID; Richter A; Peters E; Geffen J. H. G. M. van; Beirle S; Wagner T; Roozendael MV; Marchenko S; Lamsal LN; Eskes HJ Improved Slant Column Density Retrieval of Nitrogen Dioxide and Formaldehyde for OMI and GOME-2A from QA4ECV: Intercomparison, Uncertainty Characterisation, and Trends. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2018, 11 (7), 4033–4058. 10.5194/amt-11-4033-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Williams JE; Boersma KF; Sager PL; Verstraeten WW The High-Resolution Version of TM5-MP for Optimized Satellite Retrievals: Description and Validation. Geoscientific Model Development 2017, 10 (2), 721–750. 10.5194/gmd-10-7212017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Background information about the Row Anomaly in OMI. http://projects.knmi.nl/omi/research/product/rowanomaly-background.php.

- (52).Geddes JA; Martin RV; Boys BL; Donkelaar A van. Long-Term Trends Worldwide in Ambient NO2 Concentrations Inferred from Satellite Observations. Environmental Health Perspectives 2016, 124 (3), 1–9. 10.1289/ehp.1409567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Palmer PI; Abbot DS; Fu T-M; Jacob DJ; Chance K; Kurosu TP; Guenther A; Wiedinmyer C; Stanton JC; Pilling MJ; Pressley SN; Lamb B; Sumner AL Quantifying the Seasonal and Interannual Variability of North American Isoprene Emissions Using Satellite Observations of the Formaldehyde Column. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres (1984–2012) 2006, 111 (D12), D12315. 10.1029/2005jd006689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Zhu L; Jacob DJ; Keutsch FN; Mickley LJ; Scheffe R; Strum M; Abad GG; Chance K; Yang K; Rappenglück B; Millet DB; Baasandorj M; Jaeglé L; Shah V Formaldehyde (HCHO) As a Hazardous Air Pollutant: Mapping Surface Air Concentrations from Satellite and Inferring Cancer Risks in the United States. Environmental Science & Technology 2017, 51 (10), 5650–5657. 10.1021/acs.est.7b01356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Duncan BN; Yoshida Y; Damon MR; Douglass AR; Witte JC Temperature Dependence of Factors Controlling Isoprene Emissions. Geophysical Research Letters 2009, 36 (5), 1886–5. 10.1029/2008gl037090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Pusede SE; Cohen RC On the Observed Response of Ozone to NOx and VOC Reactivity Reductions in San Joaquin Valley California 1995–Present. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2012, 12 (18), 8323–8339. 10.5194/acp-12-8323-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Pusede SE; Steiner AL; Cohen RC Temperature and Recent Trends in the Chemistry of Continental Surface Ozone. Chemical Reviews 2015, 115 (10), 3898–3918. 10.1021/cr5006815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Foy B de; Lu Z; Streets DG Impacts of Control Strategies, the Great Recession and Weekday Variations on NO2 Columns above North American Cities. Atmospheric Environment 2016, 138 (C), 74–86. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.04.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Kim SW; Heckel A; McKeen SA; Frost GJ; Hsie EY; Trainer MK; Richter A; Burrows JP; Peckham SE; Grell GA Satellite-Observed U.S. Power Plant NOx emission Reductions and Their Impact on Air Quality. Geophysical Research Letters 2006, 33 (22), L22812–5. 10.1029/2006gl027749. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Frost GJ; McKeen SA; Trainer M; Ryerson TB; Neuman JA; ROBERTS JM; Swanson A; Holloway JS; Sueper DT; Fortin T; Parrish DD; Fehsenfeld FC; Flocke F; Peckham SE; Grell GA; Kowal D; Cartwright J; Auerbach N; Habermann T Effects of Changing Power Plant NOx emissions on Ozone in the Eastern United States: Proof of Concept. Journal of Geophysical Research 2006, 111 (D12), D12306–19. 10.1029/2005jd006354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Russell AR; Valin LC; Cohen RC Trends in OMI NO2 Observations over the United States: Effects of Emission Control Technology and the Economic Recession. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2012, 12 (24), 12197–12209. 10.5194/acp-12-12197-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Abbot DS Seasonal and Interannual Variability of North American Isoprene Emissions as Determined by Formaldehyde Column Measurements from Space. Geophysical Research Letters 2003, 30 (17), 1886. 10.1029/2003gl017336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Chen WH; Guenther AB; Wang XM; Chen YH; Gu DS; Chang M; Zhou SZ; Wu LL; Zhang YQ Regional to Global Biogenic Isoprene Emission Responses to Changes in Vegetation From 2000 to 2015. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2018, 123 (7), 3757–3771. 10.1002/2017jd027934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Wolfe GM; Kaiser J; Hanisco TF; Keutsch FN; Gouw JA de; Gilman JB; Graus M; Hatch CD; Holloway J; Horowitz LW; Lee BH; Lerner BM; Lopez-Hilifiker F; Mao J; Marvin MR; Peischl J; Pollack IB; ROBERTS JM; Ryerson TB; Thornton JA; Veres PR; Warneke C Formaldehyde Production from Isoprene Oxidation across NOx Regimes. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2016, 16 (4), 2597–2610. 10.5194/acp-16-2597-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Souri AH; Nowlan CR; Wolfe GM; Lamsal LN; Miller CEC; Abad GG; Janz SJ; Fried A; Blake DR; Weinheimer AJ; Diskin GS; Liu X; Chance K Revisiting the Effectiveness of HCHO/NO2 Ratios for Inferring Ozone Sensitivity to Its Precursors Using High Resolution Airborne Remote Sensing Observations in a High Ozone Episode during the KORUS-AQ Campaign. Atmospheric Environment 2020, 224, 117341–12. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Zhu L; Mickley LJ; Jacob DJ; Marais EA; Sheng J; Hu L; Abad GG; Chance K Long-Term (2005–2014) Trends in Formaldehyde (HCHO) Columns across North America as Seen by the OMI Satellite Instrument: Evidence of Changing Emissions of Volatile Organic Compounds. Geophysical Research Letters 2017, 44 (13), 7079–7086. 10.1002/2017gl073859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Spinei E; Whitehill A; Fried A; Tiefengraber M; Knepp TN; Herndon S; Herman JR; Müller M; Abuhassan N; Cede A; Richter D; Walega J; Crawford J; Szykman J; Valin L; Williams DJ; Long R; Swap RJ; Lee Y; Nowak N; Poche B The First Evaluation of Formaldehyde Column Observations by Improved Pandora Spectrometers during the KORUS-AQ Field Study. Atmos Meas Tech 2018, 11 (9), 4943–4961. 10.5194/amt-11-4943-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Li J; Wang Y; Qu H Dependence of Summertime Surface Ozone on NO Xand VOC Emissions Over the United States: Peak Time and Value. Geophysical Research Letters 2019, 46 (6), 3540–3550. 10.1029/2018gl081823. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Lindsay RW; Richardson JL; Chameides WL Ozone Trends in Atlanta, Georgia: Have Emission Controls Been Effective? Japca 1989, 39 (1), 40–43. 10.1080/08940630.1989.10466505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Chameides W; Lindsay R; Richardson J; Kiang C The Role of Biogenic Hydrocarbons in Urban Photochemical Smog: Atlanta as a Case Study. Science 1988, 241 (4872), 1473. 10.1126/science.3420404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Parrish DD; Singh HB; Molina L; Madronich S Air Quality Progress in North American Megacities: A Review. Atmospheric Environment 2011, 45 (39), 7015–7025. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.09.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Lin M; Horowitz LW; Payton R; Fiore AM; Tonnesen G US Surface Ozone Trends and Extremes from 1980 to 2014: Quantifying the Roles of Rising Asian Emissions, Domestic Controls, Wildfires, and Climate. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2017, 17 (4), 2943–2970. 10.5194/acp-17-2943-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Pollack IB; Ryerson TB; Trainer M; Neuman JA; Roberts JM; Parrish DD Trends in Ozone, Its Precursors, and Related Secondary Oxidation Products in Los Angeles, California: A Synthesis of Measurements from 1960 to 2010. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2013, 118 (11), 5893–5911. 10.1002/jgrd.50472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Murphy JG; Day DA; Cleary PA; Wooldridge PJ; Millet DB; Goldstein AH; Cohen RC The Weekend Effect within and Downwind of Sacramento - Part 1: Observations of Ozone, Nitrogen Oxides, and VOC Reactivity. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2007, 7 (20), 5327–5339. [Google Scholar]

- (75).Marr LC; Harley RA Modeling the Effect of Weekday−Weekend Differences in Motor Vehicle Emissions on Photochemical Air Pollution in Central California. Environ Sci Technol 2002, 36 (19), 4099–4106. 10.1021/es020629x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Baidar S; Hardesty RM; Kim SW; Langford AO; Oetjen H; Senff CJ; Trainer M; Volkamer R Weakening of the Weekend Ozone Effect over California’s South Coast Air Basin. Geophysical Research Letters 2015, 42 (21), 9457–9464. 10.1002/2015gl066419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Wolff GT; Kahlbaum DF; Heuss JM The Vanishing Ozone Weekday/Weekend Effect. J Air Waste Manage 2013, 63 (3), 292–299. 10.1080/10962247.2012.749312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Forster P; Solomon S Observations of a “Weekend Effect” in Diurnal Temperature Range. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2003, 100 (20), 11225–11230. 10.1073/pnas.2034034100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Sillman S; He D Some Theoretical Results Concerning O3-NOx-VOC Chemistry and NOx-VOC Indicators. Journal of Geophysical Research 2002, 107 (D22), 4659–15. 10.1029/2001jd001123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Chan Miller C; Jacob DJ; Marais EA; Yu K; Travis KR; Kim PS; Fisher JA; Zhu L; Wolfe GM; Keutsch FN; Kaiser J; Min K-E; Brown SS; Washenfelder RA; Abad GG; Chance K Glyoxal Yield from Isoprene Oxidation and Relation to Formaldehyde: Chemical Mechanism, Constraints from SENEX Aircraft Observations, and Interpretation of OMI Satellite Data. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2016, 16 (7), 4631–4639. 10.5194/acp-16-4631-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Chen X; Millet DB; Singh HB; Wisthaler A; Apel EC; Atlas EL; Blake DR; Bourgeois I; Brown SS; Crounse JD; Gouw J. A. de; Flocke FM; Fried A; Heikes BG; Hornbrook RS; Mikoviny T; Min K-E; Müller M; Neuman JA; Sullivan DWOamp apos; Peischl J; Pfister G; Richter D; Roberts JM; Ryerson TB; Shertz SR; Thompson CR; Treadaway V; Veres PR; Walega J; Warneke C; Washenfelder RA; Weibring P; Yuan B On the Sources and Sinks of Atmospheric VOCs: An Integrated Analysis of Recent Aircraft Campaigns over North America. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2019, 19 (14), 9097–9123. 10.5194/acp-19-9097-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Veefkind JP; Aben I; McMullan K; Förster H; Vries J. de; Otter G; Claas J; Eskes HJ; Haan J. F. de; Kleipool Q; Weele M. van; Hasekamp O; Hoogeveen R; Landgraf J; Snel R; Tol P; Ingmann P; Voors R; Kruizinga B; Vink R; Visser H; Levelt PF TROPOMI on the ESA Sentinel-5 Precursor: A GMES Mission for Global Observations of the Atmospheric Composition for Climate, Air Quality and Ozone Layer Applications. Remote Sensing of Environment 2012, 120 (C), 70–83. 10.1016/j.rse.2011.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Zoogman P; Liu X; Suleiman RM; Pennington WF; Flittner DE; Al-Saadi JA; Hilton BB; Nicks DK; Newchurch MJ; Carr JL; Janz SJ; Andraschko MR; Arola A; Baker BD; Canova BP; Miller CC; Cohen RC; Davis JE; Dussault ME; Edwards DP; Fishman J; Ghulam A; Abad GG; Grutter M; Herman JR; Houck J; Jacob DJ; Joiner J; Kerridge BJ; Kim J; Krotkov NA; Lamsal L; Li C; Lindfors A; Martin RV; McElroy CT; McLinden C; Natraj V; Neil DO; Nowlan CR; Sullivan EJO; Palmer PI; Pierce RB; Pippin MR; Saiz-Lopez A; Spurr RJD; Szykman JJ; Torres O; Veefkind JP; Veihelmann B; Wang H; Wang J; Chance K Tropospheric Emissions: Monitoring of Pollution (TEMPO). Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer 2017, 186, 17–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.