Abstract

The impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been starkly unequal across race and ethnicity. We examined the geographic variation in excess all-cause mortality by race to better understand the impact of the pandemic. We used individual-level administrative data on the US population between January 2011 and April 2020 to estimate the geographic variation in excess all-cause mortality by race. All-cause mortality allows a better understanding of the overall impact of the pandemic than mortality attributable to COVID-19 directly. Nationwide, adjusted excess all-cause mortality was 6.8 per 10,000 for Black people, 4.3 for Hispanic people, 2.7 for Asian people, and 1.5 for White people. Nationwide averages mask substantial geographic variation. For example, despite similar excess White mortality, Michigan and Louisiana had markedly different excess Black mortality, as did Pennsylvania compared with Rhode Island. Wisconsin experienced no significant White excess mortality but had significant Black excess mortality. Further work understanding the causes of geographic variation in racial disparities, the relevant roles of social and environmental factors relative to comorbidities, and the direct and indirect health effects of the pandemic is crucial for effective policy making.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in the United States has led to a sharp rise in all-cause mortality nationwide, starting in March 2020 and continuing in the subsequent months. Excess deaths stem from a combination of the direct effects of viral infections with the SARS-CoV-2 novel coronavirus and the indirect effects of wide-reaching societal changes associated with the pandemic.1–5

Many observers have emphasized the large differences in the impact of the pandemic across demographic and socioeconomic groups.6–9 Although some differences such as the age gradient have clear explanations based on biological pathways, the reasons for other gaps warrant further examination. This is particularly true of racial disparities in the pandemic’s impact. Nationwide, there are stark differences in excess all-cause mortality by race, as well as in case fatality rates for COVID-19 infections.10–14

The reasons for these racial disparities are poorly delineated, making it hard to formulate evidence-based mitigation policies. One crucial question that policy makers face in this context is whether racial disparities in all-cause mortality stem predominantly from disparities in the direct effects of novel coronavirus infections, such as higher infection rates or higher case fatality rates, or alternatively, whether racial disparities in all-cause mortality are driven by the indirect effects of the pandemic, such as disparities in the effect of the pandemic on livelihoods and associated excess morbidity and mortality.

An important first input into this discussion is a measurement of the overall effect of the pandemic on different demographic groups, both nationally as well as across different geographies. Although national and geographic variation in mortality associated with COVID-19 directly has been widely reported,1–11,13 less evidence has been available on the pandemic’s differential impact on all-cause mortality across both demographic groups and geographies.

To fill this gap, we drew on individual-level administrative data covering the near universe of the US population from January 2011 through April 2020. This provided demographic information on age, race, sex, state of residence, and date of death (if any). We used these data to estimate excess all-cause mortality (hereafter “excess mortality”) separately for seven race groups during the first full month of the COVID-19 pandemic (April 2020). We report estimates both for the whole nation and separately by state. We report unadjusted estimates as well as estimates adjusted to a standardized population by demographics.

Study Data And Methods

Data

We used the Census Bureau’s version of the Social Security Administration’s Numerical Identification (Census Numident) database covering the US population and deaths from January 2011 to April 2020 (inclusive) to measure the all-cause monthly mortality rate. To our knowledge, this represents one of the first studies to use the Census Numident reference file to assess the ongoing mortality effects of the pandemic. The Census Numident file covers all people with a Social Security number regardless of their geographic location. The data set is cumulative, adding people as they receive Social Security numbers on birth or arrival to the US. Deceased people are not removed from the data. For each person we observed a date of birth. For deceased people, we observed a date of death. The date of death is recorded regardless of whether the person died inside or outside the United States. The version of the Census Numident available to us was released on August 27, 2020, and included deaths through May 2020. The last month of death records in each release of the Census Numident data tend to be incomplete because of the delays in the reporting of deaths. Our analysis thus included deaths only through April 2020. Sections 1.1 and 1.2 of the online appendix describe our data sources in more detail.15

Death counts in the Social Security Administration’s Numident, the main source for the Census Numident, differ from another major source of US vital statistics—those released by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—but provided three distinct advantages for our purposes. First, the Social Security Administration’s Numident data provided an internally consistent numerator and denominator for measuring mortality, as it records not only deceased but also living people at any given moment in time; this denominator is not available in the CDC vital statistics measure. Second, we were able to link mortality records at the individual level to other demographic information about people, allowing us to estimate excess mortality by race and to adjust these estimates to a standardized distribution of demographics by race, both nationally and by state, as discussed here. Third, we were able to use a self-reported record of race, potentially improving on CDC vital statistics office data that use proxy race reports from funeral directors.16

As has previously been documented in the literature, estimates of death counts and characteristics of the deceased, such as race, differ between the Social Security Administration’s Numident and the CDC because of different underlying reporting mechanisms.17 In addition, the CDC counts all deaths that occurred on US territory regardless of nationality or immigration status, but does not cover deaths of US persons outside of the US. Section 1.3 of the appendix discusses the April 2020 difference in death counts by race and state between our baseline analytic data set and CDC vital statistics.15

We measured people’s sexes and ages (based on date of birth) in the Census Numident data. The Census Bureau’s annual address database, the Master Address File Auxiliary Reference File, was used to attach a county and state of residence to each individual-month observation when available. The online appendix discusses the use of Master Address File Auxiliary Reference file and when the address records were available in more detail.15

Self-reported race information was drawn primarily from the 2010 Decennial Census. When no record of race was available from the 2010 Decennial Census, we used the race variable recorded in the Census Bureau’s 2010 Modeled Race File. We analyzed the following seven race categories: Hispanic, non-Hispanic White (White), non-Hispanic Black (Black), non-Hispanic Asian (Asian), non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native (American Indian and Alaska Native), non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander), and non-Hispanic people of some other race or two or more races.

The monthly mortality rate for each demographic group of interest was defined as the ratio of the count of people whose death date fell within that month divided by the count of people who were alive at the beginning of the month.

Institutional Review Board determination was obtained through Stanford University; this research was determined to not involve human subjects as defined in 45 CFR 46. The analysis used preexisting deidentified data.

Statistical Analysis

Data were collapsed into counts of alive and deceased people by sex, age, race, county, month, and year. Monthly mortality rates from January 2011 through April 2020 were computed for each sex, age, race, county, and month-year combination.

Predicted and excess unadjusted all-cause mortality were computed on the basis of a linear regression model. The outcome variable was the monthly mortality rate by demographic group. The right-hand side variables were a linear annual time trend to capture secular trends, indicator variables for each calendar month to nonparametrically capture seasonal variation, and indicator variables for January, February, March, and April 2020 to capture deviations from historical trend, if any, during the first four months of 2020. All slopes and intercepts were allowed to be race-specific. Section 2 of the appendix shows the regression equation and provides more information about our specifications.15

Regression coefficients on the interaction between race indicators and the indicator for April 2020 directly measured the difference in excess mortality between racial groups. The level of excess mortality for each race (relative to a race-specific historical trend) was obtained from combining these regression coefficients with the other race-specific parameters of the regression model.

To adjust our estimates of excess mortality across races to a standardized distribution of demographics, we first estimated an augmented version of our baseline regression model that included differential intercepts and differential deviations from historical trends in January, February, March, and April 2020 for specific demographics: sex, individual state, or five-year age group. We also estimated the demographically augmented model separately by state. The coefficients on the demographic variables were then used to obtain national estimates of adjusted excess mortality for each race for a standardized population that had the same distribution of sex, age (in five-year age groups), and states of residence as the full baseline analytic data set in April 2020. In other words, each race-specific estimate was adjusted to match the national distribution of age, sex, and state in April 2020. State-specific adjusted estimates of excess mortality were obtained for the same standardized distribution of sex and age.

All regressions were estimated using Stata, version 16.1, software on data collapsed by sex, age, race, county, month, and year and were weighted by the number of people who were alive at the beginning of the month in each data cell. The 95% confidence intervals for the levels and gaps in excess all-cause mortality by race were computed using heteroskedasticity robust standard errors and the delta method.

Limitations

The main limitation of our analysis was that information on the date of birth, date of death, race, sex, and geographic location were not available for some people residing in the US.

Race information was not available for any people born after 2010; our analysis therefore excluded children ages ten and younger. As mortality rate is very low in this population, omitting children is unlikely to substantially affect our main results.

Race data from a combination of administrative records, survey, and census data were used in our baseline analysis. As we show in the online appendix, our results were similar when limiting our analysis only to people for whom we observed a race recorded in the 2010 Decennial Census.15

Our baseline analysis was limited to people for whom a state record was observed and who resided in the fifty US states or Washington, D.C. As we show in the online appendix, our unadjusted estimates of excess mortality were unaffected when including people who resided outside of the fifty states or Washington, D.C., or for whom no geographic record was observed.15 As the Census Numident database is based on the records of the Social Security Administration, mortality for people living in the US but not captured in the Social Security Administration records (for example, people without Social Security numbers) was not measured.

Finally, some people were missed in our analysis because of a lack of valid linkage keys. A unique individual-level anonymous identifier common across all data sources was used to link the Census Numident to other data sources. The linkage keys were created using personally identifiable information and probabilistic record linkage. Prior literature shows that linkage key assignment may be nonrandom, as immigrants, young people, and minorities are less likely to receive these keys.18 Our analysis required people to have valid linkage keys.

Study Results

Baseline Analytic Data set

The data set included 27 billion person-month observations and 22.4 million deaths for people ages 11–99 years (inclusive) between January 1, 2011, and April 30, 2020. The mean age in the full data set was forty-four years, and 51 percent of the people were female. The data set was 67 percent White, 14 percent Hispanic, 12 percent Black, 5 percent Asian, 0.9 percent American Indian or Alaska Native, 0.2 percent Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 0.4 percent reporting two or more races or other race. The April 2020 data included 241.5 million people ages 11–99 and 276,000 deaths. The distribution of age, sex, and geographic location in April 2020 was similar to that for the complete time range (exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1:

Summary statistics

| Variable | April 2020 | January 2011–April 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Counts (n) | ||

| Individual-months | 241,500,000 | 26,680,000,000 |

| Deaths | 276,000 | 22,400,000 |

| Summary statistics | ||

| Average age (years) | 45.14 | 44.28 |

| Female (%) | 51.17 | 51.23 |

| Geography (%) | ||

| Northeast | 17.43 | 17.72 |

| Midwest | 21.99 | 22.29 |

| South | 37.67 | 37.34 |

| West | 22.91 | 22.66 |

| Race (%) | ||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 65.96 | 67.36 |

| Hispanic | 14.70 | 13.67 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 12.57 | 12.32 |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 5.27 | 5.18 |

| American Indian and Alaskan, non-Hispanic | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic | 0.40 | 0.38 |

SOURCE Authors’ calculations from Census Numident 2011–2020, 2010 Decennial Census, 2010 Census Modeled Race File, and 2010–19 Master Address File Auxiliary Reference File. NOTES Table shows summary statistics for the baseline analytic data set constructed from the US Census Bureau version of the Social Security Administration’s Numerical Identification System database covering population and deaths from January 2011 to April 2020. The first column shows summary statistics for people who were alive at the start of April 2020. The second column shows summary statistics for all people in our baseline analytic data set who were alive as of January 1, 2011, and who were tracked until April 2020 (inclusively). All results were approved for release by the US Census Bureau, authorization number CBDRB-FY21-ERD002-003.

National All-Cause Excess Mortality By Race

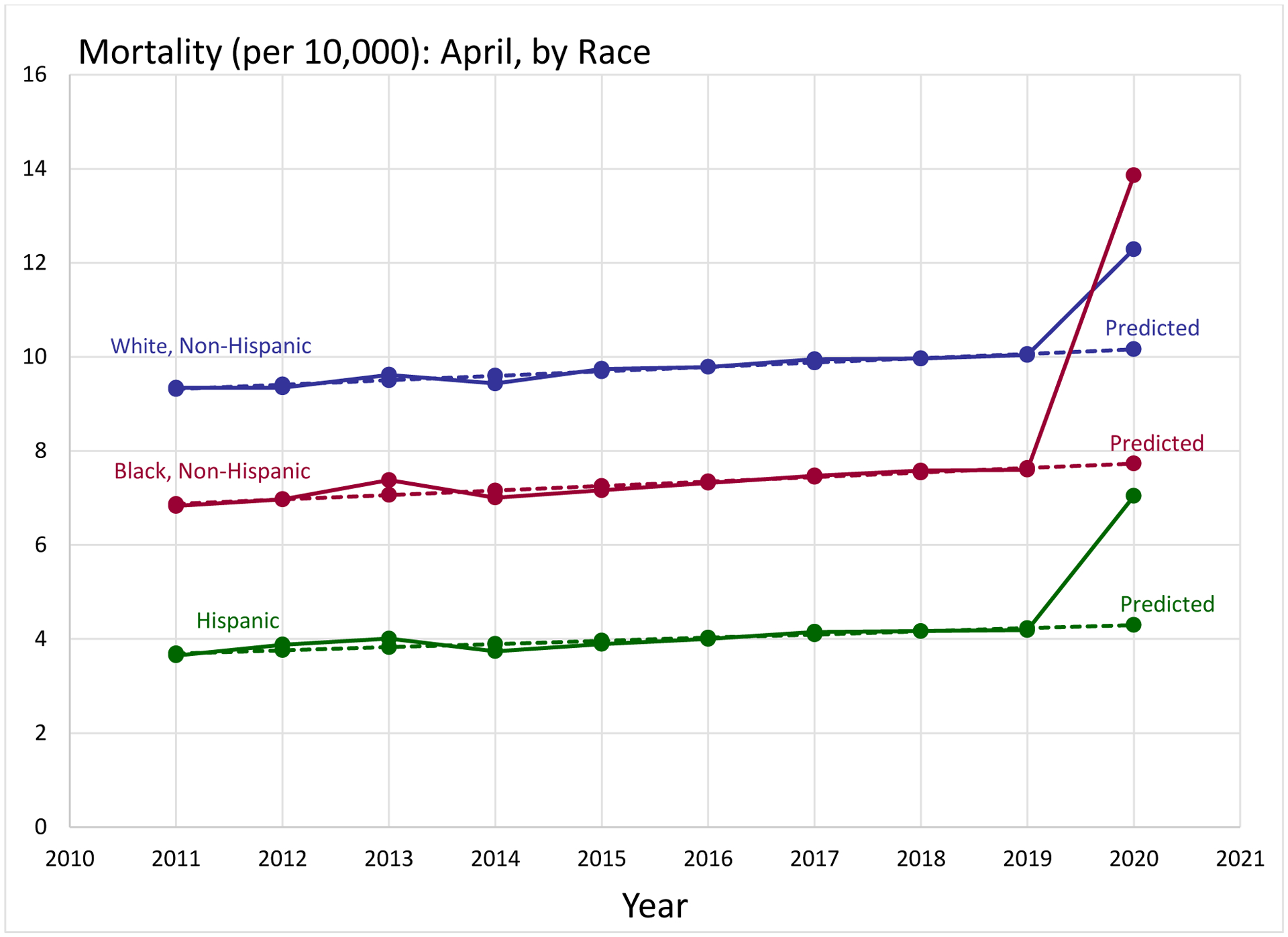

Exhibit 2 shows raw monthly all-cause mortality for April of each year separately for three race categories (results for Hawaiian and Pacific Islander people, American Indian and Alaskan people, Asian people, and people who reported having “Other and two or more races” can be found in appendix Section 3.1).15 It also superimposes the regression fit from the historical April mortality trend for each race. Two clear facts emerge. First, for all races, historical April mortality has followed a stable, close to linear, slightly upward trend during the last decade. Second, for all races, there is a pronounced upward deviation from this trend in April 2020. The difference between the observed and predicted values in April 2020 measures national race-specific excess all-cause mortality in April 2020.

Exhibit 2:

Observed and predicted April mortality by race, 2011–2020

Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ calculations from Census Numident 2011–2020, 2010 Decennial Census, 2010 Census Modeled Race File, and 2010–19 Master Address File Auxiliary Reference File. NOTES Figures show observed and predicted all-cause mortality separately by race in the month of April, 2011–20. The race-specific trends are estimated as discussed in the statistical analysis on the full data set of 26,680,000,000 individual-months from January 2011 through April 2020. All results were approved for release by the US Census Bureau, authorization number CBDRB-FY21-ERD002-003.

These estimates are reported in exhibit 3, which shows excess mortality per 10,000 people by race; all racial groups exhibited excess mortality (p < 0.05 for two-sided null hypothesis of zero excess mortality). Hawaiian and Pacific Islander unadjusted excess mortality was the lowest observed of any group, at 1.3 excess deaths per 10,000 people, which is a 22 percent increase relative to the predicted rate for April 2020 of 5.9 deaths. Black unadjusted excess mortality was the highest observed, at 6.1 excess deaths per 10,000, which is a 79 percent increase relative to the predicted rate of 7.7 deaths. Unadjusted excess mortality was 2.1 among White people (a 21 percent increase from the predicted rate of 10.2 deaths), 2.7 among Hispanic people (a 64 percent increase), 2.9 among Asian people (a 64 percent increase), 1.9 among American Indian and Alaska Native people (a 22 percent increase), and 2.7 among those with other or two or more races (a 60 percent increase). Differences relative to White unadjusted excess mortality were statistically significant at the 5 percent level for Hispanic, Black, and Asian people (appendix Section 3.2).15

Exhibit 3:

Model estimates of all-cause excess mortality in April 2020, by race

| Race/ethnicity | Excess mortality (per 10,000), April 2020 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

| Unadjusted | Age adjusted | Age, sex, and state adjusted | ||||

| Rate | Standard error | Rate | Standard error | Rate | Standard error | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 2.13 | 0.08 | 1.64 | 0.04 | 1.54 | 0.04 |

| Hispanic | 2.74 | 0.13 | 3.75 | 0.10 | 4.26 | 0.10 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 6.13 | 0.17 | 6.85 | 0.13 | 6.77 | 0.13 |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 2.86 | 0.16 | 3.00 | 0.13 | 2.73 | 0.13 |

| American Indian and Alaskan, non-Hispanic | 1.95 | 0.24 | 2.81 | 0.24 | 3.91 | 0.24 |

| Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic | 1.32 | 0.43 | 2.46 | 0.42 | 4.26 | 0.43 |

| Other or two or more, non-Hispanic | 2.74 | 0.30 | 4 | 0.30 | 3.42 | 0.30 |

SOURCE Authors’ calculations from Census Numident 2011–2020, 2010 Decennial Census, 2010 Census Modeled Race File, and 2010–19 Master Address File Auxiliary Reference File. NOTES Table shows regression-based estimates of levels of excess all-cause mortality by race in April 2020. Columns report the results of regression models with or without demographic adjustments as specified in column titles. Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. The details of the regression analysis used to construct the estimates are reported in the statistical analysis. All results were approved for release by the US Census Bureau, authorization number CBDRB-FY21-ERD002-003.

Adjusting for differences in age distributions is important for comparing all-cause mortality by race, as age distributions differ starkly across races (appendix Section 3.3).15 Adjusting for age exacerbates differences in excess mortality between White people and people of each other race (column 2). For example, the difference between Hispanic and White excess mortality rises from 0.62 deaths per 10,000 (unadjusted) to more than two deaths once age-adjusted. The highest excess mortality is still observed among Black Americans, with 6.8 excess age-adjusted deaths per 10,000 people, which is a gap of 5.2 relative to White people. In contrast, adjusting for differences in the sex distribution between races does not meaningfully change our estimates of the levels or gaps in excess mortality for any race (appendix Section 3.2).15

Adjusting for the state of residence has an important effect on the estimates of levels and differences in excess mortality for smaller racial groups (appendix Section 3.2).15 In particular, it substantially increases estimated excess mortality for American Indian and Alaska Native people, as well as for Hawaiian and Pacific Islander people. This, in turn, decreases the estimated gaps in excess mortality between these racial groups and White people.

Exhibit 3 also reports results adjusting for sex, age, and state simultaneously. This allows us to compare excess mortality rates across races for a standardized distribution of sex, age, and state of residence. This adjusted excess mortality is lowest for White people, at 1.5 excess deaths per 10,000, and highest for Black people, at 6.8 excess deaths per 10,000. Relative to White people, adjusted excess mortality rates are higher by 2.7 deaths per 10,000 for Hispanic people, 1.2 for Asian people, 2.4 for American Indian and Alaska Native people, and 2.7 for Hawaiian and Pacific Islander people.

Racial Disparities By State

Age- and sex-adjusted excess mortality showed substantial geographic variation across states for each race. Appendix Section 3.4 reports the point estimates and 95% CIs of White, Black, and Hispanic excess mortality for each state.15 The (unweighted) interquartile range across states was 0.09–1.4 excess deaths per 10,000 for White people; 1.2–4.8 excess deaths per 10,000 for Black people, and 0.13–2.1 excess deaths per 10,000 for Hispanic people.

Although Black and Hispanic people experienced higher adjusted excess mortality than White people in nearly every state, exhibits 4 and 5 show that these racial disparities differ substantially by state. We observed particularly staggering levels and racial differences in excess all-cause mortality in New York and New Jersey—the two states that were affected the most by the first wave of the pandemic. White non-Hispanic excess all-cause mortality was 7.1 per 10,000 in New York and 8.6 in New Jersey. Black people, however, experienced excess all-cause mortality that was 4.6 and 2.9 times higher in New York and New Jersey, respectively, amounting to 32.7 per 10,000 age- and sex-adjusted excess all-cause deaths among Black people in New York and 24.7 in New Jersey. Hispanic people in the two states fared only slightly better, with 27.2 per 10,000 age- and sex-adjusted excess all-cause deaths in New York and 20.5 in New Jersey.

Exhibit 4:

Association of Black non-Hispanic and White non-Hispanic excess all-cause mortality across states, April 2020

Source/Notes: Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ calculations from Census Numident 2011–2020, 2010 Decennial Census, 2010 Census Modeled Race File, and 2010–19 Master Address File Auxiliary Reference File. NOTES Figure reports the association in the estimates of sex- and age-adjusted all-cause excess mortality in April 2020 by state among non-Hispanic Black people versus non-Hispanic White people. The details of the regression analysis used to construct the estimates are reported in the statistical analysis. The trend line marks the line of best fit for the relationship between White and Black excess mortality by state. All results were approved for release by the US Census Bureau, authorization number CBDRB-FY21-ERD002-003.

Exhibit 5:

Association of Hispanic and White non-Hispanic excess all-cause mortality across states, April 2020

Source/Notes: Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ calculations from Census Numident 2011–2020, 2010 Decennial Census, 2010 Census Modeled Race File, and 2010–19 Master Address File Auxiliary Reference File. NOTES Figure reports the association in the estimates of sex- and age-adjusted all-cause excess mortality in April 2020 by state among Hispanic versus non-Hispanic White people. The details of the regression analysis used to construct the estimates are reported in the statistical analysis. The trend line marks the line of best fit for the relationship between White and Hispanic excess mortality by state. All results were approved for release by the US Census Bureau, authorization number CBDRB-FY21-ERD002-003.

In general, the difference between Black excess mortality or Hispanic excess mortality and White excess mortality was larger in states where White excess mortality was higher. But even states with similar levels of adjusted White excess mortality exhibited substantial variation in the level of adjusted Black or Hispanic excess mortality. Michigan, for instance, had much higher adjusted Black excess mortality (18.3 excess deaths per 10,000) than Louisiana (9.8 per 10,000), even though the two states had comparable adjusted White excess mortality (2.8 and 2.7 per 10,000, respectively). Likewise, Pennsylvania had much higher adjusted Black excess mortality (10.6 excess deaths per 10,000) than Rhode Island (3.4 per 10,000), even though the two states had comparable adjusted White excess mortality (1.8 and 1.7 per 10,000, respectively). As another example, Hispanics experienced higher adjusted excess mortality in Pennsylvania than in Delaware, even though White adjusted excess mortality was similar in both states. All reported comparisons are statistically significant at 5 percent confidence level (appendix Section 3.4).15

In addition, in several states, Black and Hispanic Americans experienced an increase in mortality in April 2020, whereas White people did not. For, example, in Wisconsin, we estimate adjusted excess mortality for Black people to be 4.6 per 10,000 (95% CI: 2.9, 6.3) and for Hispanic people to be 1.4 per 10,000 (95% CI: 0.5, 2.3), whereas White adjusted excess mortality was a statistically insignificant 0.27 per 10,000 (95% CI: −0.0, 0.6). In Kentucky, Alabama, South Carolina, California, and Washington, Black adjusted excess mortality was higher than 1.5 per 10,000 people (p < 0.05 for the null of zero adjusted excess mortality in each state), whereas White adjusted excess mortality was under 0.5 per 10,000 in each of those states.

Discussion

Excess all-cause mortality differed substantially across racial groups during the early spread of the novel coronavirus. Our data allowed us to examine racial disparities in national excess all-cause mortality for seven different racial groups, to examine the role of demographic differences in these racial disparities, and to examine differences in racial disparity by state. The results indicate pronounced differences in the overall impact of the pandemic across racial groups and in the extent of racial disparities across states.

All racial groups experienced substantial excess mortality in the first full month of the pandemic. When adjusted to a standardized distribution of sex, age, and state of residence, White and Asian Americans had the lowest excess mortality (at 1.5 and 2.7 excess deaths per 10,000), whereas Black Americans had the highest (at 6.8 excess deaths). Differences by race were more pronounced when adjusted for demographic differences, highlighting important differences in age and geographic distributions by race. Crude excess mortality overestimates the mortality effect for White Americans, who are on average older, and underestimates it for other races, who are on average younger. Our unadjusted national estimates of all-cause excess mortality are similar, but slightly higher, compared with those based on CDC data releases (2.75 per 10,000 in our data versus 2.4 per 10,000 based on CDC data)1,2,19; compared with prior estimates of COVID-specific deaths, our estimates suggest that 35 percent of excess deaths during the first month of the pandemic are not directly attributable to infections with the novel coronavirus. Our results are qualitatively consistent with findings of pronounced racial disparities in COVID-19-specific deaths nationwide.6,7,9

Racial disparities in adjusted excess all-cause mortality varied substantially across states. The states that exhibited the highest levels of White excess mortality of seven to eight excess deaths per 10,000 and were generally the most affected by the first wave of the pandemic, New York and New Jersey, experienced staggering levels of Black non-Hispanic and Hispanic excess mortality, ranging from twenty to more than thirty excess deaths per 10,000 people. Some states, such as Michigan and Pennsylvania, had substantially higher Black excess mortality than other states with similar White excess mortality (for example, Louisiana and Rhode Island, respectively). In addition, several states that experienced virtually no White excess mortality in April 2020 exhibited substantial Black excess mortality. For example, Wisconsin experienced significant Black excess mortality of 4.6 per 10,000, whereas the state’s White excess mortality was statistically indistinguishable from zero (point estimate, 0.27).

These findings are consistent with the growing literature that has documented the broader importance of geography for understanding the patterns of health disparities in the US.20 Although geographic difference in the overall level of excess mortality likely reflects the different timing of COVID-19’s spread, the causes of the stark variation in racial disparities across states are less clear. The geographic patterns that we document for the first full month of the pandemic may point to an important role of the indirect effects of the pandemic on non-White people. In the states where we observe excess mortality among White people that is close to zero, it is possible that the community transmission of the virus was still limited, whereas the indirect effects of the pandemic, such as the impact on the economy that has been documented to be much more geographically spread early on,2 was already affecting the non-White populace.

As direct and indirect impacts of the pandemic would call for different mitigating policies—for instance, different vaccine distribution priority in the case of direct effects and differential economic interventions in the case of indirect effects—understanding what drives the variation in all-cause mortality across states and racial groups is crucial for evidence-based policies. In addition, the geographic variation in the extent of racial disparities in the pandemic’s early and later impact may provide an opportunity to examine the relative roles of social and environmental factors (such as occupational and residential segregation) and underlying comorbidities in contributing to these racial disparities; such evidence would have important implications both for policies aimed at mitigating racial disparities during the pandemic and potentially more broadly beyond the pandemic.

In this article we demonstrate the enormous potential of linking administrative records and census responses at the individual level to explore these future research questions. An important limitation of our work is that we cannot pinpoint the drivers of the geographic variation in the racial disparities of the pandemic’s impact. Several hypotheses about the underlying causes of racial disparities in COVID’s mortality impact have been put forward, including racial differences in education and occupation21–24; neighborhood characteristics such as safety, food availability, and pollution22,24–26; risk for infection27; access to health care28; and comorbidities.24,29 Our results suggest that factors driving racial disparities may well differ across states. Assembling additional empirical evidence on the sources of geographic variation in racial disparities during the period we studied as well as later in the pandemic will likely help shed light not only on the underlying reasons for the unequal impact of the pandemic on mortality across racial groups in the US and the best associated policy responses but also on the drivers of racial health disparities more generally.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Presented at the National Bureau of Economic Research COVID-19 and Health Outcomes Conference; December 4, 2020; virtual conference. Maria Polyakova is the principal investigator for a grant from the National Institute for Health Care Management. Amy N. Finkelstein is the principal investigator for grant R01-AG032449 from the National Institute on Aging. Polyakova and Victoria Udalova contributed equally as co-first authors. The authors thank the National Institute on Aging and National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation for financial support and James Okun for outstanding research assistance. Any conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US Census Bureau. All results were approved for release by the Disclosure Review Board of the US Census Bureau, authorization number CBDRB-FY21-ERD002-003. All numeric values were rounded according to US Census Bureau disclosure protocols to preserve data privacy.

BIOS for 2020-02142 (Polyakova)

Bio1: Maria Polyakova (maria.polyakova@stanford.edu) is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at Stanford University, in California.

Bio2: Victoria Udalova is a Research Economist at the US Census Bureau, in Washington, D.C.

Bio3: Geoffrey Kocks is a graduate student in economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Bio4: Katie Genadek is a Research Economist at the US Census Bureau.

Bio5: Keith Finlay is a Research Economist at the US Census Bureau.

Bio6: Amy N. Finkelstein is the John & Jennie S. McDonald Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Notes

- 1.Rossen LM, Branum AM, Ahmad FB, Sutton P, Anderson RN. Excess deaths associated with COVID-19, by age and race and ethnicity—United States, January 26–October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(42):1522–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polyakova M, Kocks G, Udalova V, Finkelstein A. Initial economic damage from the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States is more widespread across ages and geographies than initial mortality impacts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(45):27934–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Sabo RT, Weinberger DM, Hill L. Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes, March–April 2020. JAMA. 2020;324(5):510–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinberger DM, Chen J, Cohen T, Crawford FW, Mostashari F, Olson D, et al. Estimation of excess deaths associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, March to May 2020. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1336–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz J, Lu D, Sanger-Katz M. True pandemic toll in the U.S. reaches 377,000. New York Times [serial on the Internet]. 2020. May 5 [last updated 2020 Dec 16; cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/05/05/us/coronavirus-death-toll-us.html [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bassett MT, Chen JT, Krieger N. The unequal toll of COVID-19 mortality by age in the United States: quantifying racial/ethnic disparities [Internet]. Cambridge (MA): Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies: 2020. June 12 [cited 2020 Dec 18]. (HCPDS Working Paper Vol. 19, No. 3). Available from: https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1266/2020/06/20_Bassett-Chen-Krieger_COVID-19_plus_age_working-paper_0612_Vol-19_No-3_with-cover.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford T, Reber S, Reeves RV. Race gaps in COVID-19 deaths are even bigger than they appear [Internet]. Washington (DC): Brookings Institution; 2020. June 16 [cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/06/16/race-gaps-in-covid-19-deaths-are-even-bigger-than-they-appear/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.APM Research Lab staff. The color of coronavirus: COVID-19 deaths by race and ethnicity in the U.S. [Internet]. St. Paul (MN): American Public Media; 2020. December 10 [cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-by-race [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein JR, Atherwood S. Improved measurement of racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality in the United States. medRxiv. 2020. May 23. [Preprint]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cromer SJ, Lakhani CM, Wexler DJ, Burnett-Bowie S-AM, Udler M, Patel CJ. Geospatial analysis of individual and community-level socioeconomic factors impacting SARS-CoV-2 prevalence and outcomes. medRxiv. 2020. September 30. [Preprint]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarty TR, Hathorn KE, Redd WD, Rodriguez NJ, Zhou JC, Bazarbashi JN, et al. How do presenting symptoms and outcomes differ by race/ethnicity among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection? Experience in Massachusetts. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. August 22. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seoane L. Hospitalization and mortality among Black patients and White patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2534–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rentsch CT, Kidwai-Khan F, Tate JP, Park LS, King JT Jr, Skanderson M, et al. Patterns of COVID-19 testing and mortality by race and ethnicity among United States veterans: A nationwide cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(9):e1003379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yehia BR, Winegar A, Fogel R, Fakih M, Ottenbacher A, Jesser C, et al. Association of Race with mortality among patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at 92 US hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2018039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 16.Arias E, Heron M, Hakes J,. The validity of race and Hispanic-origin reporting on death certificates in the United States: An update. Vital Health Stat 2. 2016;(172):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barbieri M Investigating the difference in mortality estimates between the Social Security Administration Trustees’ report and the Human Mortality Database [Internet]. Ann Arbor (MI): University of Michigan Retirement Research Center; 2018. September [2020 Dec 18]. (Working Paper 2018–394). Available from: https://mrdrc.isr.umich.edu/publications/papers/pdf/wp394.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bureau Census. 2010 Census match study report [Internet]. Washington (DC): Census Bureau; 2012. November 19 [cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2012/dec/2010_cpex_247.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flagg A, Sharma D, Fenn L, Stobbe M. COVID-19’s toll on people of color is worse than we knew [Internet]. New York (NY): The Marshall Project; 2020. August 21 [cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/08/21/covid-19-s-toll-on-people-of-color-is-worse-than-we-knew [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, Lin S, Scuderi B, Turner N, et al. The association between income and life Expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLaren J Racial disparity in COVID-19 deaths: seeking economic roots with census data [Internet]. Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. June [cited 2020 Dec 18]. (NBER Working Paper No. 27407). Available from: https://www.nber.org/papers/w27407.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray R Why are Blacks dying at higher rates from COVID-19? Fixgov [blog on the Internet]. 2020. April 9 [cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2020/04/09/why-are-blacks-dying-at-higher-rates-from-covid-19/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selden TM, Berdahl TA. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities in health risk, employment, and household composition. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(9):1624–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardy B, Logan TD. Racial economic inequality amid the COVID-19 crisis [Internet]. Washington (DC): Brookings Institution; 2020. August 13 [cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/research/racial-economic-inequality-amid-the-covid-19-crisis/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desmet K, Wacziarg R. Understanding spatial variation in COVID-19 across the United States [Internet]. London (UK): Centre for Economic Policy Research; 2020. June [last updated 2020 Jul; cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available from: https://cepr.org/active/publications/discussion_papers/dp.php?dpno=14842 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makridis C, Rothwell JT. The real cost of political polarization: evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Rochester (NY): SSRN; 2020. June 30 [last updated 2020 Oct 29; cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available for download from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Papers.cfm?abstract_id=3638373 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zelner J, Trangucci R, Naraharisetti R, Cao A, Malosh R, Broen K, et al. Racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality are driven by unequal infection risks. MedRxiv [serial on the Internet]. 2020. September 11 [cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2020.09.10.20192369 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishnan L, Ogunwole SM, Cooper LA. Historical insights on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the 1918 influenza pandemic, and racial disparities: illuminating a path forward. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(6):474–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2466–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.