Abstract

Objective

Globally, 11 million deaths are attributable to suboptimal diet annually, and nutrition care has been shown to improve health outcomes. While medically trained clinicians are well-placed to provide nutrition care, medical education remains insufficient to support clinicians to deliver nutrition advice as part of routine clinical practice. Competency standards provide a framework for workforce development and a vehicle for aligning health priorities with the values of a profession. Although, there remains an urgent need to establish consensus on nutrition competencies for medicine. The aim of this review is to provide a critical synthesis of published nutrition competencies for medicine internationally.

Design

Integrative review.

Data sources

CINAHL, Medline, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science and Global Health were searched through April 2020.

Eligibility criteria

We included published Nutrition Competency Frameworks. This search was complemented by handsearching reference lists of literature deemed relevant.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted into summary tables and this matrix was then used to identify common themes and to compare and analyse the literature. Miller’s pyramid, the Knowledge to Action Cycle and the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition were also used to consider the results of this review.

Results

Using a predetermined search strategy, 11 articles were identified. Five common themes were identified and include (1) clinical practice, (2) health promotion and disease prevention, (3) communication, (4) working as a team and (5) professional practice. This review also identified 25 nutrition competencies for medicine, the majority of which were knowledge-based.

Conclusions

This review recommends vertical integration of nutrition competencies into existing medical education based on key, cross-cutting themes and increased opportunities to engage in relevant, skill-based nutrition training.

Keywords: medical education & training, nutrition & dietetics, education & training (see medical education & training)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review offers a critical and timely synthesis of medical nutrition competencies and a conceptual Nutrition Competency Framework.

Themes such as communication and teamwork are not specific to nutrition and highlight integration of topics across a curriculum.

As an integrative review, this framework might be considered a candidate theory for further review and development.

It is recognised that the characteristics of included publications is skewed towards those published in the USA and that there may be other frameworks internationally. However, it is relevant to note that there are a greater number of medical education facilities in the USA than other countries included such as Australia, New Zealand and Sweden.

Research into competence and competency standards is dynamic and frameworks included are from varied time periods. This may limit application of this work to modern standards.

Introduction

Globally, 11 million deaths are attributable to suboptimal diet annually.1 Furthermore, in 2014, more than 1.9 billion adults were overweight, while 462 million were underweight. This coexistence of undernutrition, along with overweight and obesity, or diet-related chronic diseases, is referred to as the double burden of malnutrition. This burden is universal and presents an imperative to improve the nutrition capacity of the health workforce.2 Nutrition is a powerful tool for the prevention and management of diet-related chronic diseases.1 Nutrition care refers to any intervention performed by a health professional to improve the nutrition behaviour and subsequent health status of an individual or community and has been shown to improve diet-related and health outcomes, often with reduced risk, side effects and costs when compared with pharmacological interventions.3 4 For example, when doctors provide nutrition advice as part of prenatal care, their patients have fewer complications associated with pregnancy and give birth to healthier children.5 In fact, a recent systematic analysis reports that improvement of diet could potentially prevent one in every five deaths globally.1 Furthermore, public health legislation such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Sections 4001(d),3 4004(c)(d), 4103(b) and 4206) recognise the increased need for preventive healthcare interventions, such as nutrition care and authorises investments in training health professionals.6 Other countries, such as Australia, have not updated their National Nutrition Policy in over 25 years, while the National Healthy Food and Drink Policy in New Zealand does not include any reference of training of health professionals.7 8 The WHO reiterate the need for increased investments in nutrition for improved health and successful development; the objectives of Universal Health Coverage cannot be achieved until nutrition actions are integrated across the healthcare continuum.9 Therefore, it is essential that clinicians of all backgrounds are cognisant of the role of nutrition in health and are well-equipped to initiate and support nutrition care as part of routine clinical practice.

Medically trained clinicians are well-placed to initiate and support patient nutrition care,10 in part due to their regular contact with the individuals for whom they provide care. For example, 88% of individuals are likely to see a general practitioner (primary care physician) annually.11 Furthermore, in a hospital setting, an estimated 13%–69% of hospitalised individuals are malnourished on admission, and importantly, the prevalence is also high predischarge.12–15 Despite this, a recent systematic review indicates that medical education remains insufficient to support clinicians to provide nutrition care as part of routine clinical practice.16 There are a number of organisations calling for improved nutrition education for physicians.17 Competency standards provide a framework for workforce development and are essential for the delivery of safe, effective and patient-centred care18 and a vehicle for aligning the health priorities of the country with the values of a profession.19 This is particularly relevant, as there is an existing disconnect between medical education and the exigent double burden of malnutrition.16 While there are many approaches to developing a competency framework, authors argue that a preoccupation with discipline-specific tasks overlooks the relevance of cross-cutting attributes such as critical thinking, communication and collaboration which align outcomes across disciplines.18 20 An integrated approach to competency encompasses the ability to combine and apply practical and reflexive competence in different contexts.20 The use of competency standards in improving medical nutrition education has been previously established and has been shown to increase a clinician’s ability to integrate nutrition into patient care.4 Competency in nutrition care is important in the delivery of safe, effective and coordinated care.21 However, there is a recognised need to establish consensus on relevant nutrition competencies for medicine.16 The aim of this review is to provide a critical synthesis of published nutrition competencies for medicine internationally. As the UN Decade of Action on Nutrition 2016–2025 is well underway, this is a timely and important review.22

Methods

This review was an integrative literature review, a ‘form of research that reviews, critiques and synthesises representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated’.23 This methodology is considered rigorous in this context, and was selected as it allows for a combination of various study designs and data sources to be included.24 25 Data, namely, nutrition competencies, were extracted into summary tables24 and this matrix was then used to identify common themes and compare, contrast and analyse the literature.26 Miller’s pyramid, the Knowledge to Action Cycle and the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition were also used to consider the results of this review.27–29 These frameworks acknowledge the complexity of clinical competence and the process of skill acquisition including the application of knowledge in practice. Furthermore, Miller’s pyramid and the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition have been previously used as a theoretical framework on which to underpin and improve educational practice in the field of medicine.30–33 These frameworks were therefore used as a theoretical blueprint for the organisation of nutrition competencies identified in this review. For the purposes of this review, we initially defined key concepts based on published definitions and author experience (table 1).

Table 1.

Definitions of key concepts used within this review

| Concept | Definition |

| Competency (or competency standard) | A measure used to describe the idealised capacity of an individual to perform a role or set of tasks.76 |

| Competence | Competence can be described as the ability to perform a task with desirable outcomes under varied circumstances. This definition encompasses multiple components such as the habitual and judicious application of knowledge, technical skills, values, clinical reasoning and attitudes.63 77 |

| Domains of competence | Competency domains represent organised clusters of competencies which are intended to characterise a central aspect of professional practice in which a professional should be competent.34 |

| Competency framework | A competency framework represents a complete collection of competencies required for effective performance.18 |

| Curriculum framework | A curriculum framework is an organised set of standards or learning objectives that define educational requirements |

Search methods

CINAHL, Medline, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science and Global Health were searched through April 2020 to identify published Nutrition Competency Frameworks (NCFs) for medical education. The search strategy for each database is provided in online supplemental material 1. In brief, the key concepts were related to medically trained clinicians, nutrition and diet and competency. A research team comprised all authors in this study, as well as a medical librarian, agreed on terms with the aim of avoiding researcher bias when selecting articles. This search was complemented by handsearching reference lists of literature deemed relevant.

bmjopen-2020-043066supp001.pdf (60.3KB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria for this review were original research publications representing nutrition competencies for the continuum of medical education (preregistration and postregistration). We included interdisciplinary NCFs if the framework stipulated use by the medical profession. We excluded frameworks which included only limited reference to nutrition. For example, if a framework was specific to a disease, condition or specialty rather than only nutrition, the paper was excluded (eg, Cardiovascular disease-related frameworks which only included a reference to possible nutrition therapy). We included only current versions of frameworks and excluded editorials, reviews, conference proceedings, opinion papers and interviews. Grey literature was also reviewed by searching the reference lists of literature deemed relevant. The results of the search were not limited by time or language.

Search outcome

All database searches were directly imported into the electronic reference management tool Endnote V.X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, USA) and grey literature searches were manually entered by the primary author (BL). After the removal of duplicates using EndNote and manually, one author (BL) independently screened titles and abstracts and selected studies according to the predefined inclusion criteria. If the abstract was not sufficient, full texts of remaining papers were screened independently to identify publications for inclusion. Where it was not clear, the primary author engaged in consultative and iterative discussion among authors to reach consensus. All authors reached consensus on the included articles.

Data analysis

Data extraction was completed independently by the primary researcher (BL). Information relating to nutrition competencies was extracted from the retained articles. Information discussing the nutrition-related knowledge, skills or attitudes which published authors believed medical practitioners needed to obtain was categorised as a competency and recorded. Similarly, competency domains or themes represent organised clusters of competencies which are intended to characterise a central aspect of professional practice in which a professional should be competent.34 Information related to competency domains was also included. Data were extracted from each paper into a summary table and series of matrices. The following information was extracted from full-text publications and presented systematically: citation and country, organisation/group, name of the framework, nutrition domains (if stated), nutrition competencies, learning objectives (if stated) and the level of medical education that the framework is intended for (eg, residency). Findings were read, re-read and articles compared and contrasted to identify patterns and relationships.

Quality appraisal

To determine quality and risk of bias for review, the full text of each article was assessed independently for quality (including risk of bias) by the primary researcher (BL). Given the variation in research methodologies, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool was modified for use, as adapted by Halcomb et al25 (CASP; Halcomb et al25).

Patient and public involvement

There is no patient and public involved in the study.

Results

Search results

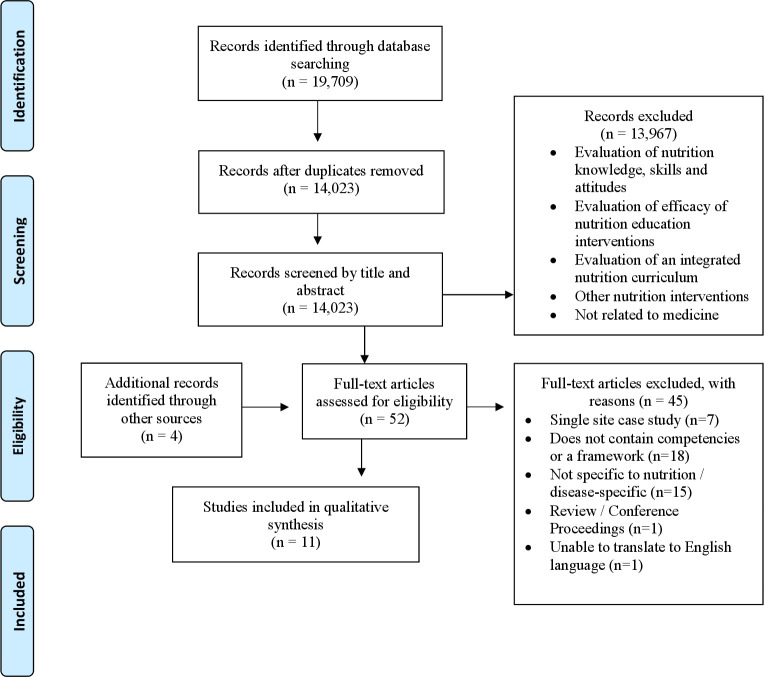

The total yield from all databases was 19 709 results. This was reduced to 14 023 results after the removal of duplicates. Using the exclusion criteria against title and abstract, a total of 56 full-text publications were assessed for eligibility, including four publications identified through hand searching of reference lists (figure 1). It is of interest to note that a considerable number of results were related to the impact of a nutrition course or competency framework on nutrition knowledge, skills and attitudes and therefore not eligible for inclusion. Following full-text review, 11 articles were included in the review. Reasons for exclusion included papers which did not include competencies or a framework (n=18) and competencies that are not specific to nutrition or competencies for a specific aspect of nutrition or healthcare (eg, cardiovascular disease nutrition competencies) (n=15). A list of excluded studies along with reasons for exclusion is provided in online supplemental material 2.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram for identification of articles related to nutrition competencies for medicine.

bmjopen-2020-043066supp002.pdf (34.1KB, pdf)

Characteristics of included publications

Included studies were published between 1983 and 2019. The majority were peer-reviewed articles (n=7), with the remaining grey literature comprising documented frameworks form expert professional groups (eg, professional associations or accrediting bodies) (n=3) and a position statement (n=1). Seven studies were from the USA, with one study from each of Australia and New Zealand, Africa, Sweden and the UK.

Quality appraisal

Descriptions of how the competency frameworks were developed varied in level of detail. It is important to note that few publications reported the research methods used to develop their frameworks. Furthermore, few publications acknowledged the limitations or weaknesses of the processes used to develop the competency frameworks (question 5). Given these limitations, articles that did not achieve a ‘yes’ on all items of the checklist were not excluded from the review, but the appraisal was taken into consideration in the overall rigour of the present review (table 2).

Table 2.

Quality appraisal

| ||||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | |

| American Academy of Family Physicians, 1998 | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| Asp et al48 | Unclear | Yes | ||||

| Cuerda et al35 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes |

| Deen et al47 | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| Deakin University Strategic Teaching and Learning Grant Steering Committee38 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | |

| Jhpiego & Save the Children45 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Lindsley et al36 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Maillet and Young44 | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| Sierpina et al21 | Unclear | Yes | Yes | |||

| Young et al46 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| ICGN Undergraduate Nutrition Education Implementation Group39 | Unclear | Yes | ||||

Competency domains

Five of eleven publications (45%) explicitly used competency domains to categorise or subdivide nutrition competencies. Different methods of classification, or domains, included type of competency (such as knowledge, skills and attitudes), domains of human nutrition (including concepts of basic nutrition, concepts of applied nutrition and principles of clinical nutrition) and subdivision of competencies by nutrition concept (eg, macronutrients and micronutrients) or by elements of nutrition care (eg, diagnosis, treatment, prevention).35–40 The most common competency domains were related to the role of nutrition in health promotion and disease prevention (n=3), nutrition assessment (n=2) and nutrition management (n=2).36 37 39 Competency domains which were identified but only found within one framework included those related to patient nutrition counselling skills, nutrition referral, nutrition evidence, aspects of critical nutrition care (such as enteral and parenteral nutrition) and the impact of disease on nutrition.36 39

The NCF for medical graduates, developed by the Deakin University Strategic Teaching and Learning Grant Steering Committee in Australia, was the only framework in this review purposefully mapped to a medical framework, namely, the Australian Medical Council (AMC) Graduate Outcome Statements.38 41 Other frameworks in this review, published in the UK, are endorsed by statutory bodies such as the General Medical Council (GMC) and Medical Schools Council.39 42 43 Some interdisciplinary NCFs also delineated competencies, such as by amount of patient education responsibility or by level of service delivery, to emphasise the relevance of nutrition competencies for the wider health workforce.44 45

Despite differences in the taxonomy and language across included nutrition competencies for medical education, there are some common underlying themes, which in some contexts may be considered ‘domains’ if the papers are summarised. Specifically, five common themes were identified across the included nutrition competencies, including clinical practice (all 11 publications), health promotion and disease prevention (n=8), communication (n=7), working as a team (n=7) and professional practice (n=3). These themes overlap with existing medical competency standards and could be considered cross-cutting.

Competencies

Twenty-five unique nutrition competencies for medical education were identified in the 11 publications. Fifteen of twenty-five nutrition competencies for medicine were classified as knowledge/behaviour-based competencies. For example, ‘Demonstrate knowledge of the functions of essential nutrients’.36 40 Seven nutrition competencies were classified as skill-based (eg, ‘Demonstrate ability to select and prescribe dietary strategies in the prevention and treatment of disease’36 38–40 44–48) and only four competencies were attitude/value-based (eg, ‘Demonstrate sensitivity to the social, cultural, emotional and psychological factors that may affect an individual’s nutrition behaviour and health status’36 (table 3). The most common nutrition competencies (suggested in greater than 50% of articles), were related to (1) skills in nutrition assessment, (2) the ability to prescribe dietary interventions in the prevention and treatment of disease, (3) knowledge of the role of nutrition in health promotion and disease prevention and (4) knowledge of the social and cultural importance of food, including food consumption trends and current nutrition recommendations. Authors less commonly suggested the relevance of demonstrating competency in how disease can affect nutritional status, food-borne illness, an awareness of personal health and nutrition and a commitment to provide evidence-based nutrition care for all patients regardless of health status. Articles published in developed countries were more likely to recommend competencies related to nutritional management of chronic diseases, while studies originating from low-income and middle-income countries included competencies related to emergency medicine and nutritional management for people living with HIV and AIDS.36 45 One paper specified cross-cutting nutrition competencies for all health professionals including community mobilisation and nutrition counselling.45

Table 3.

Nutrition competencies for medicine

| Theme and number of publications which include this theme | Domain | Competency | Competency type | n* |

| Clinical practice n=11 (100%) | Nutrition assessment | Demonstrate skills in the assessment of nutritional health including the ability to calculate energy expenditure, nutrition requirements and body composition21 35 36 38–40 44–48 | Skill | 11 |

| Nutrition management | Demonstrate knowledge of evidence-based dietary strategies for prevention and treatment of disease21 35 36 38 | Knowledge/behaviour | 4 | |

| Demonstrate ability to select and prescribe dietary strategies in the prevention and treatment of disease36 38–40 44–48 | Skill | 9 | ||

| Demonstrate knowledge of possible drug–nutrient interactions and prescribe accordingly21 35 36 40 46 | Skill | 5 | ||

| Demonstrate knowledge of breast feeding and complementary feeding practices36 45 | Knowledge/behaviour | 2 | ||

| Nutrition monitoring and evaluation | Demonstrate the ability to monitor nutrition status and modify dietary recommendations as needed46 47 | Skill | 2 | |

| Health promotion and disease prevention n=8 (73%) | Basic sciences as applied to nutrition | Demonstrate knowledge of the basic scientific principles of human nutrition35 36 38 | Knowledge/behaviour | 3 |

| Demonstrate knowledge of nutrition applied to different stages of the life cycle35 36 40 | Knowledge/behaviour | 3 | ||

| Demonstrate awareness of the nutritional content of food including the major dietary sources of macronutrients and micronutrients35 36 40 | Knowledge/behaviour | 3 | ||

| Demonstrate knowledge of the difference between food allergies and food intolerance35 36 40 | Knowledge/behaviour | 3 | ||

| Demonstrate knowledge of the functions of essential nutrients36 40 | Knowledge/behaviour | 2 | ||

| Demonstrate an understanding of how disease and its management can affect nutritional status39 | Knowledge/behaviour | 1 | ||

| The role of nutrition in health promotion and disease prevention | Demonstrate an awareness of their own personal health and nutrition21 | Attitude/value | 1 | |

| Demonstrate knowledge of the role of nutrition in health promotion and disease prevention35 36 38–40 44 48 | Knowledge/behaviour | 7 | ||

| Demonstrate knowledge of the social and cultural importance of food, including awareness of food consumption trends and current nutrition recommendations21 35 36 38 40 48 | Knowledge/behaviour | 6 | ||

| Demonstrate knowledge of nutrition-related causes of mortality and morbidity in the population21 35 48 | Knowledge/behaviour | 3 | ||

| Demonstrate knowledge of the principles of public health nutrition, including strategies to reduce the burden of disease36 45 | Knowledge/behaviour | 2 | ||

| Describe food-borne illnesses and outline the process of reporting and investigating outbreaks of these illnesses36 | Knowledge/behaviour | 1 | ||

| Communication n=7 (64%) | Nutrition counselling skills | Demonstrate the ability to effectively provide nutrition education and counselling21 35 36 40 44 47 | Skill | 6 |

| Demonstrate sensitivity to the social, cultural, emotional, and psychological factors that may affect an individual’s nutrition behaviour and health status36 | Attitude/value | 2 | ||

| Working as a team n=7 (64%) | The multidisciplinary team approach to nutrition care | Demonstrate the ability to work effectively in a multidisciplinary team to deliver nutrition care, including the ability to refer onwards21 36 38 44 46 | Skill | 5 |

| Demonstrate knowledge of the role of other health professionals and community services in the multidisciplinary approach to nutrition care36 40 48 | Knowledge/behaviour | 3 | ||

| Professional practice n=3 (27%) | Critical thinking | Demonstrate ability to think critically including the ability to interpret nutrition evidence and apply appropriately in clinical practice21 36 38 40 47 | Skill | 3 |

| Ethics | Demonstrate the ability to consider and apply principles of ethics related to nutritional management35 36 38 | Attitude/value | 2 | |

| Demonstrate a commitment to promote sound nutritional decision-making and appropriate levels of physical activity for all patients regardless of health status36 | Attitude/value | 1 |

*Number of articles which include this competency.

Level of medical education

All 11 articles specified the level of medical education where there would be an expectation to teach and achieve the nutrition competencies. Five articles included nutrition competencies for undergraduate and graduate (entry-level) medical education. Three of the eleven articles stipulated use by primary care providers and one paper included competencies for family practice residents. The remaining two articles merely specified use by ‘practicing physicians’.

Summary of concepts

A summary NCF, adapted from Hughes et al20 and informed by the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition, the framework for clinical competency assessment outlined in Miller and the Knowledge to Action Cycle as described by Graham and colleagues20 27 28 49–51 is presented based on the competencies in the literatureor table 4). This provides a preliminary model for an NCF for medicine, which can be further investigated in subsequent research. In this framework, categories of competency units are delineated into four different tiers to represent hierarchies of competency acquisition and assessment. At the base of the matrix are enabling and critical competencies (know and know how) which underpin higher level nutrition practice behaviours. At a foundational level, the Dunning-Kruger effect indicates that individuals may be ‘unconsciously unskilled’.52 The proposed framework also includes common, cross-cutting attributes identified in this review. Cross-cutting competencies delineate the professionalism required for effective, collaborative and safe practice and improve the transferability of the competency framework across health disciplines.20 Top-level practice competencies are defined by Hughes et al20 as ‘higher order composite behaviours’ which are required to ‘perform complex practice behaviours’ which underpin core functions of the profession.20 Practice competencies involve behavioural performance (showing how and doing) and it is hoped the inclusion of these competencies bridges the gap between cognitive competencies and translation in practice.20

Table 4.

Proposed conceptual nutrition competency framework for medicine

| Practice (does) |

Assessment of nutritional health including the ability to calculate energy expenditure, nutrition requirements and body composition | Select and prescribe dietary strategies in the prevention and treatment of disease | Monitor nutrition status and modify dietary recommendations as needed | Effectively provide nutrition education and counselling | Work effectively in a multidisciplinary team to deliver nutrition care, including the ability to refer onwards | ||

| Cross-cutting (shows how) | Clinical practice | Health promotion and disease prevention | Communication | Working as a team | Professional practice | ||

| Critical (knows how) |

Evidence-based dietary strategies for the prevention and treatment of disease | Knowledge of possible drug–nutrient interactions and prescribe accordingly | Think critically including the ability to interpret nutrition evidence and apply appropriately in clinical practice | Consider and apply principles of ethics related to nutritional management | Commitment to promote sound nutritional decision-making and appropriate levels of physical activity for all patients regardless of health status | Awareness of their own personal health and nutrition | |

| Enabling (knows) |

Knowledge of the functions of essential nutrients | Nutritional content of food including the major dietary sources of macronutrients and micronutrients | Nutrition applied to different stages of the life cycle | Describe food- borne illnesses and outline the process of reporting and investigating outbreaks of these illnesses | An understanding of how disease and its management can affect nutritional status | Awareness of the social and cultural importance of food, including food consumption trends and current nutrition recommendations | |

| Basic scientific principles of human nutrition | The role of nutrition in health promotion and disease prevention | Breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices | Food allergies and intolerances | Nutrition-related causes of mortality and morbidity in the population | Public health nutrition, including strategies to reduce the burden of disease | The role of other health professionals and community services in the multidisciplinary approach to nutrition | |

Discussion

There is currently no consensus on nutrition competencies relevant for medical education. This review provides a critical synthesis of published nutrition competencies for medical education and practice internationally. This review identified five common themes across nutrition competencies which add to existing literature related to medical nutrition education. Twenty-five unique nutrition competencies for medical education were identified from 11 articles.

The five common themes across nutrition competencies for medicine, were clinical practice, health promotion and disease prevention, communication, working as a team and professional practice. The latter three, while referring to nutrition, highlighting generic skills that are required to be applied across all aspects of medical care. This is congruent with core competencies and individual roles in existing medical frameworks, such as the CanMEDS Physician Competency Framework, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) core competencies, the GMC Outcomes for graduates, the AMC Limited Graduate Outcome Statements and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians Professional Practice Framework.41 53–56 For example, the CanMEDS Physician Competency Framework, one of the most globally recognised healthcare profession competency frameworks articulates a number of intrinsic roles which reflect key themes identified in this review, such as the communicator, collaborator and health advocate.

Generic themes such as those identified in this review can provide leverage in educational reform, by aligning incentives to facilitate synergy across healthcare professions.57 For example, a multidisciplinary team (MDT—identified as ‘working as a team’ in this review) approach to nutrition care has been shown to provide high quality, cost-effective nutrition outcomes.58 59 However, there is a disconnect between the university education environment, which is generally not interdisciplinary, and the practice environment, which increasingly requires collaborative skills.57 Furthermore, communication and collaboration are key aspects of the iterative process of knowledge translation, including the ability to exchange information to overcome barriers to implementation. Communication and collaboration (teamwork) were also common themes identified by this review. Optimised knowledge translation has been shown to improve the quality of evidence-based nutrition care and strengthen the healthcare system, as summarised by the Knowledge to Action Cycle.50 Not only does this cross-over between medical and nutrition competencies highlight the lateral nature of nutrition as a cognate scientific discipline, but it also provides merit to opportunity for the vertical integration of nutrition competencies into existing medical education. Rather than an isolated concept with a distinct set of competencies, existing medical spiral curricula could be enhanced by applying existing medical competencies to a nutrition context. Deen60 illustrated this by successfully mapping the Curriculum Committee of the National Academic Award learning objectives to the ACGME competencies for competency-based resident evaluation.60 This reiterates the relevance of nutrition as a core facet of clinical practice without necessarily adding time to curricula. Namely, vertical integration of nutrition competencies into medical education is particularly relevant in a crowded curriculum, and is a key element of a successful integrated medical nutrition curriculum, shown to improve medical students’ perceptions of nutrition as part of total patient care.61 62 However, there is a need to first build consensus on nutrition competencies for medical education.

The majority of the medical nutrition competencies identified in this review were knowledge-based, while less than 30% of nutrition competencies were skill-based and only four competencies were attitude-based (table 3). While knowledge-based (enabling) competencies are essential to interpret new concepts in nutrition and underpin higher order (practice) competencies, skill-based competencies are relevant to clinical practice, which requires the complex and judicial application of knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, values and reflection under varied circumstances.63 This is in line with the experience of medical graduates and practising physicians, who do not feel comfortable or adequately prepared to provide nutrition counselling to their patients.10 16 64 65 In order to overcome these barriers, Adams et al66 and Lindsley et al36 emphasise the need for ‘skill-centred nutrition training’.66 A realist synthesis of educational interventions to improve nutrition care competencies and delivery by doctors and other healthcare professionals, reports that educational interventions which led to improvements in the delivery of nutrition care focused on skills and attitudes rather than just knowledge.67 Skill-based nutrition training has been shown to improve medical students’ nutrition knowledge and confidence in lifestyle counselling.68

While competency frameworks provide an architectural blueprint for constructing educational programmes, the centrality of valid assessment methods to support the life-long journey of competency development cannot be overlooked.19 Increasing the weighting of a topic in assessment has been shown to enhance medical students’ reported motivation to learn about the topic.69 Furthermore, regular and repeated assessment can improve knowledge retention in medical students.70 71 This is particularly important given that despite initial high interest in nutrition, interest in and perception of the importance of nutrition may decline during time in medical school.72 Earlier research highlights the effectiveness of the Objective Structured Clinical Exam (OSCE) in evaluating the ability to synthesise and translate knowledge to clinical practice.62 Miller also emphasises the role of skill-based assessment methods such as the OSCE in the appraisal of technical and clinical competence.73 Problem-based learning tutorials, culinary skills training and clinical case presentations have also been shown to promote active learning and lead to significant changes in participants’ knowledge, personal health habits, confidence to provide dietary counselling and ability to nutritionally manage malnutrition.67 A combination of innovative learning strategies is required to support the development of clinical competence. Educational strategies and assessment methods which improve nutrition care competencies, such as problem-based learning and the OSCE, are already widely used methods in medical education.74 Therefore, the application of existing learning to a nutrition context, such as a nutrition OSCE, may lead to improvements in competency to provide nutrition care in future practice. There is currently no consensus on the required nutrition competencies for medicine, which presents a further barrier to the integration of nutrition in medical education.16 The nutrition competencies identified in this review provide a potential benchmark for the nutrition knowledge, skills and attitudes to be included in curricula (table 3). However, given the lack of consensus on relevant nutrition competencies, commitment of individual institutions to compulsory nutrition education is insufficient and regulation is required. The 2019 report ‘Doctoring Our Diet’ recommends policy levers to include nutrition in US medical training, such as government investment to provide financial incentive for the inclusion of nutrition in medical training, amending accreditation standards to mandate requirements for nutrition education, increasing representation of nutrition in step and board-examinations and compulsory nutrition training in continuing medical education.17

Strengths and limitations

This review offers a critical and timely synthesis of medical nutrition competencies and a conceptual NCF. As an integrative review, this framework might be considered a candidate theory for further review and development. However, this review also needs to be considered in the context of its limitations. While the search strategy used included terms previously used to identify competency frameworks, others may exist and therefore some studies may not have been captured. We acknowledge there may be some bias in the conduct of the review in that only one author was involved in extraction of data. It is recognised that the characteristics of included publications is skewed towards those published in the USA (and English language) and that this may have biased our findings. However, it is relevant to note that there are a greater number of medical education facilities in the USA than other countries included such as Australia, New Zealand and Sweden.75 The majority (6/7) of the included studies were published in developed countries; this may have implications on the generalisability of the proposed NCF. We used the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition, Miller’s hierarchy for the assessment of clinical competence and the Knowledge to Action Cycle20 27 28 49 50 to frame this work, and acknowledge that other frameworks may also be useful in this context. For example, the frameworks used may not consider elements of cognitive aptitude such as diagnostic reasoning.

Conclusion

This review identified five common, cross-cutting themes across nutrition competencies for medicine: (1) clinical practice, (2) health promotion and disease prevention, (3) communication, (4) working as a team and (5) professional practice. This review also identified 25 nutrition competencies for medicine, the majority of which were knowledge-based. The most common nutrition competencies were related to nutrition assessment, dietary interventions for the prevention and treatment of disease, the role of nutrition in health promotion and disease prevention and knowledge of the social and cultural importance of food. This review recommends vertical integration of nutrition competencies into existing medical education based on key, cross-cutting themes and increased opportunities to engage in relevant, skill-based nutrition training.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Isla Kuhn, Medical Librarian at the University of Cambridge for her invaluable input to the search strategy.

Footnotes

Contributors: BL, EJB, KJM and SR contributed to the design of the review. BL did the literature search, performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript. EJB contributed to data extraction. All authors contributed to revision of the manuscript and approval of the final manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. Patients and/or the public were not involved in this study.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. Not applicable.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators . Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 2019;393:1958–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . The double burden of malnutrition: policy brief. Geneva: World Health organization. 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/255413

- 3.Gwynn J, Sim K, Searle T, et al. Effect of nutrition interventions on diet-related and health outcomes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025291. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kris-Etherton PM, Akabas SR, Douglas P, et al. Nutrition competencies in health professionals' education and training: a new paradigm. Adv Nutr 2015;6:83–7. 10.3945/an.114.006734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kominiarek M, Rajan P. Nutrition recommendations in pregnancy and lactation. Med Clin 2016;100:1199–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Authenticated U.S. Government Information . Patient and Affordable care act, HR 3590, 111th Congress, Sec. 1001, 2020. Available: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-111hr3590enr/pdf/BILLS-111hr3590enr.pdf

- 7.Australian Government . Food and nutrition policy. Canberra: Australian Government, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Health . National healthy food and drink policy (2nd ed). Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . Mobilising ambitious and impactful commitments for mainstreaming nutrition in health systems: nutrition in universal health coverage - global nutrition summit. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ball LE, Hughes RM, Leveritt MD. Nutrition in general practice: role and workforce preparation expectations of medical educators. Aust J Prim Health 2010;16:304–10. 10.1071/PY10014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners . General practice: health of the nation 2018. East Melbourne, Victoria: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Flynn J, Peake H, Hickson M, et al. The prevalence of malnutrition in hospitals can be reduced: results from three consecutive cross-sectional studies. Clin Nutr 2005;24:1078–88. 10.1016/j.clnu.2005.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh H, Watt K, Veitch R, et al. Malnutrition is prevalent in hospitalized medical patients: are housestaff identifying the malnourished patient? Nutrition 2006;22:350–4. 10.1016/j.nut.2005.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang MC KJ, Ryu SW, Moon JY, et al. Korean Society for parenteral and enteral nutrition (KSPEN) clinical research groups. prevalence of malnutrition in hospitalized patients: a multicenter cross-sectional study. J Korean Med Sci 2018;33:e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Vliet IMY, Gomes-Neto AW, de Jong MFC, et al. High prevalence of malnutrition both on hospital admission and predischarge. Nutrition 2020;77:110814. 10.1016/j.nut.2020.110814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowley J, Ball L, Hiddink GJ. Nutrition in medical education: a systematic review. Lancet Planet Health 2019;3:E379–89. 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Food Law and Policy Clinic, Harvard Law School . Doctoring our diet: policy tools to include nutrition in U.S. medical training. 2019. https://www.chlpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Doctoring-Our-Diet_-September-2019-V2.pdf

- 18.Hughes R. Competencies for effective public health nutrition practice: a developing consensus. Public Health Nutr 2004;7:683–91. 10.1079/PHN2003574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gruppen LD, Mangrulkar RS, Kolars JC. The promise of competency-based education in the health professions for improving global health. Hum Resour Health 2012;10:43. 10.1186/1478-4491-10-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes R, Shrimpton R, Recine E. Empowering our profession [Commentary]. World Nutr J 2012;3:33–54. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sierpina VS, Welch K, Devries S, et al. What competencies should medical students Attain in nutritional medicine? Explore 2016;12:146–7. 10.1016/j.explore.2015.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations . United nations decade of action on nutrition 2016-2025, 2020. Available: https://www.un.org/nutrition/about

- 23.Torraco RJ. Writing integrative literature reviews: guidelines and examples. Hum Resour Manag Rev 2005;4:356–67. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 2005;52:546–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halcomb E, Stephens M, Bryce J, et al. Nursing competency standards in primary health care: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs 2016;25:1193–205. 10.1111/jocn.13224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 2005;52:546–53. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med 1990;65:s63–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benner P. Use of the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition to describe and interpret skill acquisition and clinical judgement in nursing practice and education. Bull Sci Technol Soc 2005;24:188–99. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graham I, Tetroe J, Pearson A. Turning knowledge into action: practical guidance on how to do integrated knowledge translation research. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Field A. Understanding the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition to improve ultrasound training for obstetrics and gynaecology trainees. Ultrasound 2014;22:118–22. 10.1177/1742271X14521125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell EL, Arora S. How educational theory can inform the training and practice of vascular surgeons. J Vasc Surg 2012;56:530–7. 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.01.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadideen H, Plonczak A, Saadeddin M, et al. How educational theory can inform the training and practice of plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2018;6:e2042. 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carr SJ. Assessing clinical competency in medical senior house officers: how and why should we do it? Postgrad Med J 2004;80:63–6. 10.1136/pmj.2003.011718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frankson R, Hueston W, Christian K, et al. One health core competency domains. Front Public Health 2016;4:192. 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cuerda C, Muscaritoli M, Donini LM, et al. Nutrition education in medical schools (NEMS). An ESPEN position paper. Clin Nutr 2019;38:969–74. 10.1016/j.clnu.2019.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindsley JE, Abali EE, Bikman BT, et al. What nutrition-related knowledge, skills, and attitudes should medical students develop? Med Sci Educ 2017;27:579–83. 10.1007/s40670-017-0476-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akner G, Andersson H, Forsum E, et al. [A national document on clinical nutrition. Developmental work for improvement of medical education]. Lakartidningen 1997;94:1731–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deakin University Strategic Teaching and Learning Grant Steering Committee . Extended nutrition competency framework (NCF). Committee DUSTaLGS 2016.

- 39.ICGN Undergraduate Nutrition Education Implementation Group . CGN undergraduate curriculum in nutrition. United Kingdom. 2013. https://www.aomrc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Undergraduate_Curriculum_Nutrition_0213-2.pdf

- 40.Recommended core educational guidelines on nutrition for family practice residents. Am Fam Physician 1989;40:265–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Australian Medical Council Limited . Assessment and Accreditation of Primary Medical Programs by the Australian Medical Council 2012. https://www.deakin.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/511245/NCF_extended_final_March2016.pdf

- 42.General medical Council . General medical council: general medical Council, 2020. Available: https://www.gmc-uk.org/

- 43.Medical Schools Council . Home: medical schools Council (MSC), 2020. Available: https://www.medschools.ac.uk/

- 44.Maillet JO, Young EA. Position of the American dietetic association: nutrition education for health care professionals. J Am Diet Assoc 1998;98:343–6. 10.1016/s0002-8223(98)00080-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jhpiego & Save the Children . Nutrition core competencies for health science cadres and undergraduate nutritionists in Ethiopia 2012. https://resources.jhpiego.org/resources/nutrition-core-competencies-health-science-cadres-and-undergraduate-nutritionists-ethiopia

- 46.Young EA, Weser E, McBride HM, et al. Development of core competencies in clinical nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr 1983;38:800–10. 10.1093/ajcn/38.5.800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deen D, Karp R, Lowell B. A new approach to nutrition education for primary care physicians in the United States. J Gen Intern Med 1994;9:407–8. 10.1007/BF02629525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Asp NG, Akner G, Forsum E, et al. [Nutrition in Swedish medical education]. Nord Med 1995;110:292–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dreyfus S, Dreyfus H. A five-stage model of the mental activities involved in directed skill acquisition and clinical judgement in nursing practice and education. Berkeley: University of California, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laur C, Keller HH. Implementing best practice in hospital multidisciplinary nutritional care: an example of using the knowledge-to-action process for a research program. J Multidiscip Healthc 2015;8:463–72. 10.2147/JMDH.S93103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a MAP? J Contin Educ Health Prof 2006;26:13–24. 10.1002/chp.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dunning D. Chapter Five - The Dunning-Kruger Effect: On Being Ignorant of One’s Own Ignorance. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 2011;44:247–96. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada . CanMEDS 2015 physician competency framework. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) . ACGME core competency [ACGME Outcome Project Web site] 2007. http://www.acgme.net/outcome/comp/compFull.asp

- 55.RACP . Professional practice framework: Royal Australiasian College of physicians (RACP), 2020. Available: https://www.racp.edu.au/trainees/curricula/professional-practice-framework

- 56.General Medical Council (GMC) . Outcomes for graduates 2018. London, UK: General Medical Council (GMC), 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Institute of Medicine (IOM) . Committee on the Health Professions Education Summit, Greiner, A. C., & Knebel, E. (Eds.). (2003). Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. National Academies Press (US), 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Butcher M. P1.29: the impact of a nutrition multidisciplinary team. Transplantation 2019;103:S73–4. 10.1097/01.tp.0000575832.73538.eb [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rasmussen NML, Belqaid K, Lugnet K, et al. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary nutritional support in older hospitalised patients: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2018;27:P44–52. 10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deen D. How can nutrition education contribute to competency-based resident evaluation? Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:976S–80. 10.1093/ajcn/83.4.976S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krebs NF, Primak LE. Comprehensive integration of nutrition into medical training. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:945S–50. 10.1093/ajcn/83.4.945S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taren DL, Thomson CA, Koff NA, et al. Effect of an integrated nutrition curriculum on medical education, student clinical performance, and student perception of medical-nutrition training. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;73:1107–12. 10.1093/ajcn/73.6.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs 1982;82:402–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levine BS, Wigren MM, Chapman DS, et al. A national survey of attitudes and practices of primary-care physicians relating to nutrition: strategies for enhancing the use of clinical nutrition in medical practice. Am J Clin Nutr 1993;57:115–9. 10.1093/ajcn/57.2.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soltesz KS, Price JH, Johnson LW, et al. Family physicians' views of the preventive services Task force recommendations regarding nutritional counseling. Arch Fam Med 1995;4:589–93. 10.1001/archfami.4.7.589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Powell M, et al. Nutrition in medicine: nutrition education for medical students and residents. Nutr Clin Pract 2010;25:471–80. 10.1177/0884533610379606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mogre V, Scherpbier AJJA, Stevens F, et al. Realist synthesis of educational interventions to improve nutrition care competencies and delivery by doctors and other healthcare professionals. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010084. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pang B, Memel Z, Diamant C, et al. Culinary medicine and community partnership: hands-on culinary skills training to empower medical students to provide patient-centered nutrition education. Med Educ Online 2019;24:1630238. 10.1080/10872981.2019.1630238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wormald BW, Schoeman S, Somasunderam A, et al. Assessment drives learning: an unavoidable truth? Anat Sci Educ 2009;2:199–204. 10.1002/ase.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Larsen DP, Butler AC, Roediger HL. Test-Enhanced learning in medical education. Med Educ 2008;42:959–66. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kromann CB, Jensen ML, Ringsted C. The effect of testing on skills learning. Med Educ 2009;43:21–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03245.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morgan SL, Weinsier RL, Boker JR, et al. A comparison of nutrition knowledge of freshmen and senior medical students: a collaborative study of southeastern medical schools. J Am Coll Nutr 1988;7:193–7. 10.1080/07315724.1988.10720236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med 1990;65:s63–7. 10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Witheridge A, Ferns G, Scott-Smith W. Revisiting Miller's pyramid in medical education: the gap between traditional assessment and diagnostic reasoning. Int J Med Educ 2019;10:191–2. 10.5116/ijme.5d9b.0c37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.World Directory of Medical Schools . World Directory of Medical Schools: World Federation for Medical Education (WFME) & Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research (FAIMER), 2020. Available: https://search.wdoms.org/

- 76.Verma S, Paterson M, Medves J. Core competencies for health care professionals: what medicine, nursing, occupational therapy, and physiotherapy share. J Allied Health 2006;35:109–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA 2002;287:226–35. 10.1001/jama.287.2.226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-043066supp001.pdf (60.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043066supp002.pdf (34.1KB, pdf)