INTRODUCTION

Adolescence and young adulthood may be characterized as a time of becoming.1 It is a time of significant personal and professional growth and of recognizing major life milestones such as graduations, jobs, and new relationships. Nearly 90,000 adolescents and young adults (AYAs) in the United States are diagnosed with cancer annually,2 experiencing it as a significantly distressing, widely disruptive, and singularly defining event in their lives. For AYAs with cancer, their “time of becoming” often is characterized by adapting to a wide-ranging number of challenges that compromise their physical, emotional, and social development and health-related quality of life (HRQOL).3–6 Their lives are less focused on life milestones and more on major treatment milestones such as completing chemotherapy, receiving “clean” scans, and returning to work or school.7–10 Among AYAs, cancer is the most common disease-related cause of death for females and second only to heart disease for males,2 yet the vast majority of AYAs will survive their disease with an average 5-year survival rate of >80%.11–13 Unfortunately, many AYA survivors report poorer HRQOL compared with their healthy peers,3,4 and are at increased risks of cancer-related infertility, financial hardship, disease recurrence, second primary cancers, and symptom burden for late and long-term effects.14–16

Despite the unique needs and challenges of being diagnosed with and surviving cancer as an AYA, the HRQOL experiences of AYA patients rarely are evaluated as part of clinical trials,17 and when they are assessed, they are inconsistently and incompletely captured by existing patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures. In 2013, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) held a State of the Science meeting to review and discuss current gaps in the evidence base for AYA oncology across epidemiology, basic biology, clinical trials, health services and medical care, and HRQOL research.13 Key findings and future directions to advance AYA oncology research were summarized in a special series of articles published in Cancer in the spring of 2016. Among the consensus recommendations for “next steps” from the HRQOL working group was the following: “Valid, reliable, developmentally relevant, and psychometrically robust measures of HRQOL, overall and by subdomain, are needed that cross the age spectrum and allow for studies of the full AYA age range.”13

More recently, the Childhood Cancer Data Initiative (CCDI) highlighted a similar need “to collect, analyze, and share data to address the burden of cancer in children and AYAs.”18 The CCDI has called for a better understanding of the barriers to PRO data collection in pediatric and AYA studies as well as the increased use of valid and reliable assessment measures. Common barriers to the completion of PROs can occur at both the patient and clinic levels. At the patient level, factors that decrease completion rates can include respondent burden, measures that are not content or culturally relevant to the patient experience, or measures that are poorly written (those that are colloquial, double-barreled, or have high literacy levels) and/or are available only in English. At the provider and/or clinic level, PROs are not always integrated into the electronic medical record or the existing workflow, paper forms can be misplaced, and the scoring of measures may not be interpretable or actionable. Collectively, these factors have contributed to the relatively low yield of PRO data from AYAs to inform future research and cancer care.

The goal of the current commentary was to highlight the benefit of applying scale development methodologies from the National Institutes of Health’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) to the field of HRQOL measurement among AYAs who are affected by cancer. This can be done in 2 ways: 1) using existing PROMIS measures that are relevant to the life experiences of AYA patients; and 2) using PROMIS methodologies to develop new measures for AYA patients in which gaps in important HRQOL content domains exist. PROMIS represents the state-of-the-art measurement science of PROs and is a National Institutes of Health Roadmap initiative designed to improve the assessment of PROs using modern psychometric methods.19,20 The main focus of the PROMIS initiative has been on developing instruments to assess health status for patients with chronic disease conditions across the age range from pediatrics to adults. Adapting the World Health Organization’s tripartite framework of physical, mental, and social health,21 PROMIS has developed and calibrated measures with which to capture multiple areas of health and functioning22–30 and has extensive evidence of its validity and reliability in both pediatric and adult cancer populations.31–38

HRQOL Measurement in AYAs

AYAs with cancer represent a wide range of both disease types and developmental stages, with a correspondingly wide range of HRQOL priorities. The most common cancer types among AYAs are breast cancer, thyroid cancer, hematologic malignancies, germ cell cancer, and melanoma.39 Developmentally, the AYA age group captures at least 3 distinct subgroups of adolescents (aged 15–17 years), emerging adults (aged 18–25 years), and young adults (aged 26–39 years).40 This level of disease and developmental heterogeneity results in an understandably broad range of HRQOL domains impacted by cancer and a lack of consensus regarding the standardized assessment of HRQOL for AYA patients. A recent systematic literature review identified the following core domains of HRQOL for AYAs: physical, cognitive, emotional, restricted activities, relationships with others, fertility, body image, and spirituality/outlook on life.41 In an observational study of developmentally diverse AYA patients and survivors, their most important HRQOL domains were physical function, pain, cognitive function, social support, and finances.42 The importance of individual HRQOL domains varied based on the age of the subgroup and treatment status. Pain more frequently was ranked as a priority domain for AYA patients undergoing treatment compared with those who had completed treatment, and finances were more commonly ranked by older AYA patients. In what to our knowledge is the largest population-based study of HRQOL conducted in AYA patients, the National Cancer Institute’s Adolescent & Young Adult Health Outcomes & Patient Experience (AYA HOPE) study,43 the most common negative psychosocial life disruptions reported by AYAs (regardless of their age cohort) were finances, body image, and fertility and/or parenthood.44

Unfortunately, existing HRQOL measures for AYAs often are limited in several important ways: content that is not specific to the unique HRQOL needs of AYAs or appropriate for their age group, questions that are not perceived to be relevant to AYAs, summary scores that lack meaningful reference values or norms, and questions that describe concepts in idiomatic or culturally biased ways or are otherwise not translatable.42,45–47 Thus, there is a clear need for psychometrically robust measures of HRQOL to be used with AYAs that capture meaningful constructs. Rather than reinvent the wheel, it is important to provide a clearer delineation of the appropriateness of existing HRQOL measurement frameworks and to identify any existing gaps in HRQOL domains for AYA patients with cancer. Existing measures of HRQOL may be generic, providing global evaluations of HRQOL across broad domains of physical, mental, and social health, or they may be cancer specific, incorporating disease-specific and treatment-specific aspects of HRQOL. Furthermore, these measures may be developed for and validated with pediatric and adolescent populations (eg individuals aged 8–17 years) or adult populations (individuals aged ≥18 years). Applying these tools for AYA research is challenging when the cohort crosses the common threshold of 18 years of age. Instead of using both pediatric and adult HRQOL measures to conduct research in AYAs, a single AYA HRQOL profile measure with a select number of short forms that captures the relevant HRQOL domains for individuals aged 15 to 39 years would be ideal.

An informal review of generic and cancer-specific HRQOL measures for pediatric and AYA populations (Table 1)48–55 identified cross-cutting themes of physical, mental, and social HRQOL. Additional areas of relevance to the HRQOL of AYAs are not easily captured by these 3 overarching themes and therefore comprise a fourth category for “other” HRQOL concerns (eg, school, work). To the best of our knowledge, only 2 measurement frameworks cover the entire AYA age range from 15 to 39 years: the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL),54–56 which has separate, partially overlapping forms for adolescents, emerging adults, and young adults; and the Minneapolis-Manchester Quality of Life Instrument (MMQL),50,51 which has separate, nonparallel forms for adolescents and for young adults. It is interesting to note that several important aspects of the AYA experience (ie, financial burden,46,57 body image concerns,41,46 and fertility and/or parenthood concerns41,45) are rarely and inconsistently assessed using these measures.

TABLE 1.

Common Measures and Domains for Assessing HRQOL in AYAsa

| Domain | MMQL Adolescent and Young Adult Forms | PedsQL 4.0 Generic and 3.0 Cancer Module | PCQL-32 and PCQL Modular | LAYA-SRQL | IOC-CS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For Ages: | 13 to 20 and 21 to 45 Years | 13 to 18, 18 to 25, and ≥25 Years | 8 to 18 Years | 18 to 39 Years | 18 to 39 Years |

| Physical |

|

|

|

|

|

| Mental |

|

|

|

|

|

| Social |

|

|

|

|

|

| Other |

|

|

|

Abbreviations: AYA, adolescent and young adult; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; IOC-CS, Impact of Cancer scale for childhood cancer survivors48; LAYA-SRQL, Late Adolescence and Young Adulthood–Survivorship-Related Quality of Life scale49; MMQL Adolescent, Minneapolis-Manchester Quality of Life instrument–Adolescent form50; MMQL Young Adult, Minneapolis-Manchester Quality of Life instrument–Young Adult form51; PCQL Modular, Pediatric Cancer Quality of Life Inventory–Modular Approach53; PCQL-32, Pediatric Cancer Quality of Life Inventory-3252; PedsQL 3.0 Cancer Module, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Cancer Module54; PedsQL 4.0 Generic, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Version 4.0 Generic Core Scales.55

Bold font indicates the presence of financial burden, body image, and fertility and/or parenthood dimensions captured by existing measures.

Advantages of PROMIS

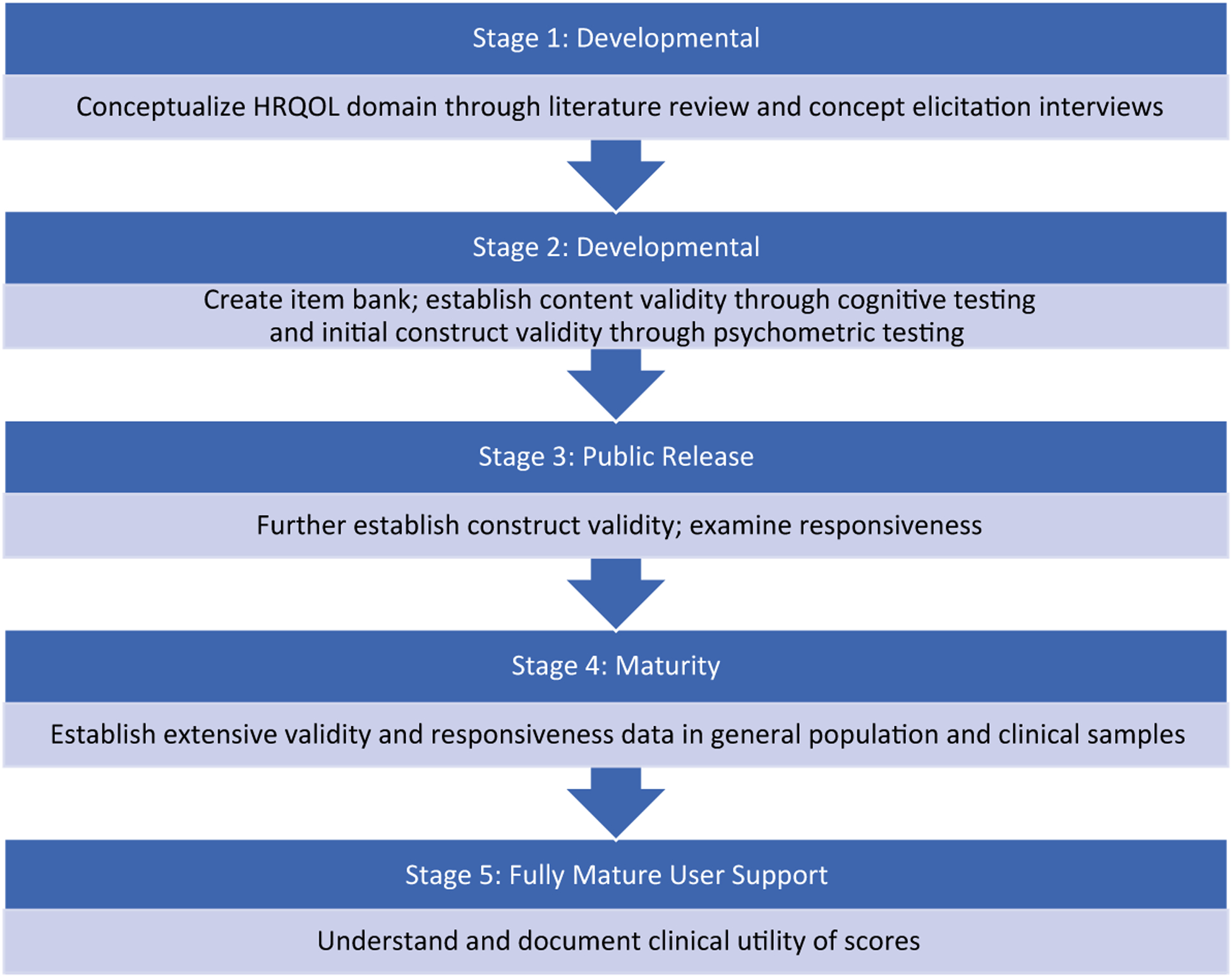

PROMIS includes >300 measures of physical, mental, and social HRQOL from among 102 adult and 25 pediatric domains.58 The PROMIS approach involves iterative steps of comprehensive literature searches, the development of conceptual frameworks through concept elicitation interviews, identifying and categorizing items, the qualitative assessment of items using focus groups and cognitive interviews, and the quantitative evaluation of items using techniques from both classic test theory and item response theory.19,20,32,59–61 To assist developers in meeting the scientific standard criteria for assessing PROs, the PROMIS investigators created an Instrument Maturity Model.62 This model describes the 5 stages of instrument development from latent trait or domain conceptualization to evidence of psychometric properties in multiple clinical samples (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Instrument Maturity Model. HRQOL indicates health-related quality of life. For additional details regarding the PROMIS Instrument Maturity Model, see http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/PROMISStandards_Vers_2_0_MaturityModelOnly_508.pdf.

What makes PROMIS stand apart from other established HRQOL measures is that each HRQOL domain measured by PROMIS is captured by an item bank. Other established HRQOL measures have a limited number of questions with which to assess each HRQOL construct (eg, 6 questions regarding fatigue, 8 questions regarding physical functioning, etc). The PROMIS item banks (1 bank for each PRO) include a much larger number of questions that have undergone extensive testing using qualitative and quantitative methods. Every PROMIS measure draws a select number of questions from the item bank to provide a reliable and valid assessment of the HRQOL domain of interest (eg, selecting 10 fatigue questions from the 95 fatigue questions in the PROMIS Fatigue item bank). PROMIS measures can be administered on paper or electronically as fixed-length short forms. This version of the PROMIS measure means that everyone in the study answers the same set of questions (eg, the 10-question fatigue measure). An alternate way to administer PROMIS measures is through computer adaptive testing (CAT). A CAT-based assessment individually tailors the measure to each individual based on her or his responses to each question administered. Compared with fixed-length short forms, the CAT can reduce the number of questions being administered (eg, perhaps 5 instead of 10 questions) and achieve appropriately reliable measurements. Because all PROMIS measures (fixed-length short forms or CAT-based assessments) use items selected from the same PROMIS item bank, the scores can be compared or combined together across the measures.

A particular challenge within AYA HRQOL measurement is that both pediatric and adult perspectives are represented among individuals aged 15 to 39 years. Previous testing of PROMIS measures was conducted with a broad age range (8 to 17 years and 18 to ≥99 years) and did not include a specific focus on AYAs. Linking analyses provide an approach with which to “connect” the pediatric and adult forms in physical and emotional health domains.63,64 Alternatively, many of the adult items may prove reliable and valid for administration with older adolescents (those aged 15–17 years), thereby precluding the need for multiple forms. A unique strength of item banking and CAT is the flexibility in administration within a diverse sample. For example, younger and older AYAs may have different social health needs and priorities. A core set of items could be selected from within the PROMIS Social Health bank that can form a fixed-length short form across the entire AYA age range and be supplemented with additional items from the bank for specific age groups (younger vs older AYAs) to allow for greater measurement precision. This approach would provide tailoring at the item content level while also preserving comparability of scores within the full AYA age range.

Leveraging PROMIS standards and methodology is an important next step to improve the assessment of HRQOL in AYA patients with cancer. PROMIS can serve as a blueprint for researchers interested in developing new measures that have the same high standards as PROMIS as well as extending existing PROMIS measures to new clinical populations of interest (eg, AYA patients). Accordingly, developing new item banks to assess financial burden, body image concerns, and fertility and/or parenthood concerns among AYAs will allow the creation of optimal short forms and CATs. These tools should be designed following the PROMIS scientific standards60 and related COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN).65–68 By adhering to this rigorous stepwise approach to the development and testing of PROs, PROMIS can be used effectively to address many of the challenges that exist in measuring HRQOL among AYA patients with cancer (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

AYA HRQOL Measurement Challenges and Potential Solutions

| AYA HRQOL PRO Measures Need to Be… | PROMIS Provides… |

|---|---|

| Flexible | Fixed short forms or computer adaptive testing |

| Efficient | Minimal response burden by selecting the most relevant questions |

| Reliable | Includes questions that demonstrate high ability to differentiate among individual HRQOL levels |

| Age appropriate | Adult PROMIS questions are written at a ≤ sixth-grade reading level |

| Relevant | Wide range of HRQOL domains can be assessed by PROMISa |

| Comprehensible | Vetted through cognitive interviews with a diverse sample of individuals with respect to age, educational level, race and/or ethnicity, and health status |

| Interpretable | Uses easily interpretable T score metric with reference scores to the US general population |

| Translatable | Available in Spanish and other languages |

Abbreviations: AYA, adolescent and young adult; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; PRO, patient-reported outcome; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

The PROMIS HRQOL domains overlap with the majority of important HRQOL domains for AYAs with the exception of financial burden, body image, and fertility and/or parenthood.

Conclusions

The NCI has issued a clear call for a more psychometrically robust approach to measurement science in AYA oncology, a call that has been echoed by the CCDI. Advances in the development and validation of PROs for use with AYAs will strengthen understanding of the patient experience and ultimately may contribute to the more efficient identification of AYA patients who are at risk of experiencing psychosocial distress and deleterious outcomes. There is growing awareness in the oncology field that PROs are valuable for capturing the patient experience to evaluate treatment efficacy and safety and should be collected routinely in trials.69–74 Additional buy-in and sustained support from funding and regulatory agencies as well as from leaders of oncology cooperative groups and review committees is needed to further catalyze PRO research in AYA oncology. A measurement system that is flexible, efficient, reliable, age appropriate, relevant, comprehensible, interpretable, and translatable holds the potential to significantly elevate AYA clinical care and research pursuits. PROMIS provides this needed framework and approach to move this field forward.

FUNDING SUPPORT

Supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award R01CA218398. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

John M. Salsman was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01CA218398) for work performed as part of the current study. David E. Victorson was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01CA218398; Principal Investigator: John M. Salsman) for work performed as part of the current study. Bradley J. Zebrack was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01CA218398) for work performed as part of the current study. Bryce B. Reeve was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01CA218398; Principal Investigator: John M. Salsman) for work performed as part of the current study. All co-authors received some salary support from the same grant.

Footnotes

Portions of this article were previously presented at the 3rd Global Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Congress; Sydney, New South Wales, Australia; December 4–6, 2018.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mack JW. The PRISM intervention for adolescents and young adults with cancer: paying attention to the patient as a whole person. Cancer. 2018;124:3802–3805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. American Cancer Society; 2020. Accessed April 20, 2020. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2020.html [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith AW, Bellizzi KM, Keegan THM, et al. Health-related quality of life of adolescent and young adult cancer patients in the United States: the AYA HOPE study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2136–2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salsman JM, Garcia SF, Yanez B, Sanford SD, Snyder MA, Victorson D. Physical, emotional, and social health differences between post-treatment young adults with cancer and matched healthy controls. Cancer. 2014;120:2247–2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Victorson D, Garcia SF, Sanford S, Snyder MA, Lampert S, Salsman JM. A qualitative focus group study to illuminate the lived emotional and social impacts of cancer and its treatment on young adults. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2019;8:649–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Husson O, Zebrack BJ, Block R, et al. Health-related quality of life in adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: a longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:652–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vetsch J, Wakefield CE, McGill BC, et al. Educational and vocational goal disruption in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2018;27:532–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zebrack B, Kent EE, Keegan TH, Kato I, Smith AW. “Cancer sucks,” and other ponderings by adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2014;32:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keegan TH, Lichtensztajn DY, Kato I, et al. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: a population-based cancer registry study. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:239–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ketterl TG, Syrjala KL, Casillas J, et al. Lasting effects of cancer and its treatment on employment and finances in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2019;125:1908–1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keegan TH, Ries LA, Barr RD, et al. Comparison of cancer survival trends in the United States of adolescents and young adults with those in children and older adults. Cancer. 2016;122:1009–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moke DJ, Tsai K, Hamilton AS, et al. Emerging cancer survival trends, disparities, and priorities in adolescents and young adults: a California Cancer Registry–based study. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019;3:pkz031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith AW, Seibel NL, Lewis DR, et al. Next steps for adolescent and young adult oncology workshop: an update on progress and recommendations for the future. Cancer. 2016;122:988–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barr RD, Ferrari A, Ries L, Whelan J, Bleyer WA. Cancer in adolescents and young adults: a narrative review of the current status and a view of the future. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smitherman AB, Anderson C, Lund JL, Bensen JT, Rosenstein DL, Nichols HB. Frailty and comorbidities among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer: a cross-sectional examination of a hospital-based survivorship cohort. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2018;7:374–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salsman JM, Bingen K, Barr RD, Freyer DR. Understanding, measuring, and addressing the financial impact of cancer on adolescents and young adults. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66:e27660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollock BH. What’s missing in the assessment of adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer outcomes? J Natl Cancer Inst. Published online March 3, 2020. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Institute. Childhood Cancer Data Initiative (CCDI). Published 2020. Access June 12, 2020. https://www.cancer.gov/research/areas/childhood/childhood-cancer-data-initiative

- 19.DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, Stone AA;PROMIS Cooperative Group. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS Qualitative Item Review. Med Care. 2007;45(5 suppl 1):S12–S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, et al. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Med Care. 2007;45(5 suppl 1):S22–S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, Cella D; PROMIS Cooperative Group. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18:263–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia SF, Wagner LI, Choi S, George J, Cella D. PROMIS-compatible perceived cognitive function item banks for people with cancer. Paper presented at: Second Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information Systems (PROMIS) Conference; March 2008; Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hahn EA, Devellis RF, Bode RK, et al. Measuring social health in the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): item bank development and testing. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:1035–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu L, Buysse DJ, Germain A, et al. Development of short forms from the PROMIS sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairment item banks. Behav Sleep Med. 2011;10:6–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai JS, Cella D, Choi S, Teresi JA, Hays RD, Stone AA. Developing a fatigue item bank for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS FIB version 1). Presented at: International Conference on Survey Methods in Multinational, Multiregional, and Multicultural Contexts (3MC); June 25–29, 2008; Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, et al. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain. 2010;150:173–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Revicki DA, Cook KF, Amtmann D, Harnam N, Chen WH, Keefe FJ. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of the PROMIS pain quality item bank. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:245–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rose M, Bjorner JB, Gandek B, Bruce B, Fries JF, Ware JE Jr. The PROMIS Physical Function item bank was calibrated to a standardized metric and shown to improve measurement efficiency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:516–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weinfurt KP, Lin L, Bruner DW, et al. Development and initial validation of the PROMIS(®) Sexual Function and Satisfaction Measures Version 2.0. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1961–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hinds PS, Nuss SL, Ruccione KS, et al. PROMIS pediatric measures in pediatric oncology: valid and clinically feasible indicators of patient-reported outcomes. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia SF, Cella D, Clauser SB, et al. Standardizing patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer clinical trials: a Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5106–5112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flynn KE, Lin L, Cyranowski JM, et al. Development of the NIH PROMIS Sexual Function and Satisfaction measures in patients with cancer. J Sex Med. 2013;10(suppl 1):43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reeve BB, McFatrich M, Mack JW, et al. Expanding construct validity of established and new PROMIS pediatric measures for children and adolescents receiving cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67:e28160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hinds PS, Wang J, Cheng YI, et al. PROMIS pediatric measures validated in a longitudinal study design in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66:e27606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reeve BB, Edwards LJ, Jaeger BC, et al. Assessing responsiveness over time of the PROMIS® pediatric symptom and function measures in cancer, nephrotic syndrome, and sickle cell disease. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:249–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen RE, Potosky AL, Reeve BB, et al. Validation of the PROMIS physical function measures in a diverse US population–based cohort of cancer patients. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:2333–2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen RE, King-Kallimanis BL, Sexton E, et al. Measurement properties of PROMIS Sleep Disturbance short forms in a large, ethnically diverse cancer cohort. Psychol Test Assess Modeling. 2016;58:353–370. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bleyer A, Barr R, Hayes-Lattin B, Thomas D, Ellis C, Anderson B. The distinctive biology of cancer in adolescents and young adults. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:288–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sodergren SC, Husson O, Robinson J, et al. Systematic review of the health-related quality of life issues facing adolescents and young adults with cancer. Qual Life Res. 2017;26:1659–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salsman J, Snyder M, Zebrack B, Reeve B, Chen E. Measuring quality of life in adolescents and young adults (AYAS) with cancer: a promising solution? Ann Behav Med. 2016;50(suppl 1):1–335.26318593 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith AW, Keegan T, Hamilton A, et al. Understanding care and outcomes in adolescents and young adult with cancer: a review of the AYA HOPE study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66:e27486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bellizzi KM, Smith A, Schmidt S, et al. Positive and negative psychosocial impact of being diagnosed with cancer as an adolescent or young adult. Cancer. 2012;118:5155–5162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quinn GP, Huang IC, Murphy D, Zidonik-Eddelton K, Krull KR. Missing content from health-related quality of life instruments: interviews with young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quinn GP, Goncalves V, Sehovic I, Bowman ML, Reed DR. Quality of life in adolescent and young adult cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2015;6:19–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clinton-McHarg T, Carey M, Sanson-Fisher R, Shakeshaft A, Rainbird K. Measuring the psychosocial health of adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors: a critical review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zebrack BJ, Donohue JE, Gurney JG, Chesler MA, Bhatia S, Landier W. Psychometric evaluation of the impact of cancer (IOC-CS) scale for young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:207–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park C, Wortmann J, Hale A, Cho D, Blank T. Assessing quality of life in young adult cancer survivors: development of the Survivorship-Related Quality of Life scale. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2213–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhatia S, Jenney ME, Bogue MK, et al. The Minneapolis-Manchester Quality of Life instrument: reliability and validity of the Adolescent Form. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4692–4698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bhatia S, Jenney ME, Wu E, et al. The Minneapolis-Manchester Quality of Life instrument: reliability and validity of the Youth Form. J Pediatr. 2004;145:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Varni JW, Katz ER, Seid M, Quiggins DJ, Friedman-Bender A. The pediatric cancer quality of life inventory-32 (PCQL-32): I. Reliability and validity. Cancer. 1998;82:1184–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seid M, Varni JW, Rode CA, Katz ER. The Pediatric Cancer Quality of Life Inventory: a modular approach to measuring health-related quality of life in children with cancer. Int J Cancer Suppl. 1999;12:71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Katz ER, Meeske K, Dickinson P. The PedsQL in pediatric cancer: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer. 2002;94:2090–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39:800–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robert RS, Paxton RJ, Palla SL, et al. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of the pediatric quality of life inventory generic core scales, cancer module, and multidimensional fatigue scale in long-term adult survivors of pediatric cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:703–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Minimizing the “financial toxicity” associated with cancer care: advancing the research agenda. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108:djv410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.HealthMeasures. HealthMeasures (introduction). Published 2017. Accessed June 12, 2020. http://www.healthmeasures.net/index.php

- 59.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45(5 suppl 1):S3–S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Measures Health. PROMIS Health Organization and PROMIS Cooperative Group. PROMIS® Instrument Development and Validation: Scientific Standards Version 2.0 (revised May 2013). Published 2013. Access April 2, 2020. http://www.nihpromis.org/Documents/PROMISStandards_Vers2.0_Final.pdf

- 61.Lasch KE, Marquis P, Vigneux M, et al. PRO development: rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:1087–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Measures Health. PROMIS Health Organization and PROMIS Cooperative Group. PROMIS® Instrument Maturity Model (revised May 2013). Published 2013. Access date April 2, 2020. http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/PROMISStandards_Vers_2_0_MaturityModelOnly_508.pdf

- 63.Tulsky DS, Kisala PA, Boulton AJ, et al. Determining a transitional scoring link between PROMIS® pediatric and adult physical health measures. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:1217–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reeve BB, Thissen D, DeWalt DA, et al. Linkage between the PROMIS® pediatric and adult emotional distress measures. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:823–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, Ostelo RW, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res. 2011;21:651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:539–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, et al. Protocol of the COSMIN study: COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.St Germain D, Denicoff A, Torres A, et al. Reporting of health-related quality of life endpoints in National Cancer Institute–supported cancer treatment trials. Cancer. 2020;126:2687–2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Basch E The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:865–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Au HJ, Ringash J, Brundage M, Palmer M, Richardson H, Meyer RM; NCIC CTG Quality of Life Committee. Added value of health-related quality of life measurement in cancer clinical trials: the experience of the NCIC CTG. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10:119–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Secord AA, Coleman RL, Havrilesky LJ, Abernethy AP, Samsa GP, Cella D. Patient-reported outcomes as end points and outcome indicators in solid tumours. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12:358–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cella D In our patient-centered era, it is time we gave patient-reported outcomes their due. Cancer. 2020;126:2592–2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith AB, Cocks K, Parry D, Taylor M. Reporting of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) data in oncology trials: a comparison of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life (EORTC QLQ-C30) and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G). Qual Life Res. 2014;23:971–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]