Abstract

Background and aim

Cognitive impairment and sleep disorder are both common poststroke conditions and are closely related to the prognosis of patients who had a stroke. The Impairment of CognitiON and Sleep after acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack in Chinese patients (ICONS) study is a nationwide multicentre prospective registry to investigate the occurrence and associated factors of cognitive impairment and sleep disorder after acute ischaemic stroke (AIS) or transient ischaemic attack (TIA).

Methods

Consecutive AIS or TIA in-hospital patients within 7 days after onset were enrolled from 40 participating sites in China. Comprehensive baseline clinical and imaging data were collected prospectively. Blood and urine samples were also collected on admission and follow-up visits. Patients were interviewed face to face for cognition and sleep related outcomes at 2 weeks, 3, 6 and 12 months after AIS/TIA and followed up for clinical outcomes by telephone annually over 5 years.

Results

Between August 2015 and January 2018, a total of 2625 patients were enrolled. 92.65% patients had AIS and 7.35% patients had TIA. Overall, the average age was 61.04 years, and 72.38% patients were male. Median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was 3 in AIS patients.

Conclusions

The ICONS study is a large-scale nationwide prospective registry to investigate occurrence and the longitudinal changes of cognitive impairment and sleep disorder after AIS or TIA. Data from this registry may also provide opportunity to evaluate associated factors of cognitive impairment or sleep disorder after AIS or TIA and their impact on clinical outcome.

Keywords: stroke, brain

Introduction

With the accelerating process of population ageing, stroke has been a leading cause of disability.1

Cognitive impairment and sleep disorder are both common poststroke conditions and are closely related to reduced quality of life, poorer functional outcome and more recurrent strokes.2–6

Poststroke cognitive impairment (PSCI) and poststroke sleep disorder may cast a heavy economic burden to families and society.

Stroke is now one of the main diseases affecting the health of Chinese people. The National Epidemiological Survey of Stroke in China reported that there were 11 million patients who had a stroke in China in 2013. The annual age-standardised incidence is 247/100 000.7 8 In China, among incident and prevalent strokes, ischaemic stroke constituted 69.6% and 77.8%.7 Patients with PSCI and sleep disorders should be a huge population. However, there is currently no nationwide multicentre survey of cognitive impairment and sleep disorder in acute ischaemic stroke (AIS) and transient ischaemic attack (TIA) patients in China, except data from some cities.9–11 There are also few international studies on sleep disorder after stroke and its impact on the prognosis of stroke.12

There are reports that about 60%–70% of people with cognitive impairment also have sleep disorder.13 Some research had found that sleep fragmentation and abnormal sleep duration were both related to poorer cognitive performance and risk of dementia.13–15 Obstructive sleep apnoea is also linked with poorer attention, executive functioning, visuospatial and constructional abilities, and psychomotor speed in non-demented.16 So conducting a registration study to evaluate both of them at the same follow-up points may help to better explore their connections and interactions. Treating sleep problems and disorders in patients who had a stroke may be a potential strategy to prevent cognitive decline.

We conducted this study to investigate the occurrence and the associated factors of cognitive impairment and sleep disorder after AIS or TIA in Chinese patients. This article introduces the design, rationale and baseline patient characteristics of the study.

Methods

Overview of the study

The Impairment of CognitiON and Sleep after acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack study in Chinese patients (ICONS) is one of the research subgroups of China National Stroke Registry-III (CNSR-III).17 CNSR-III is a national prospective registry that recruited consecutive AIS or TIA in-hospital patients within 7 days after onset from 201 hospitals that cover 22 provinces and 4 municipalities in China.17

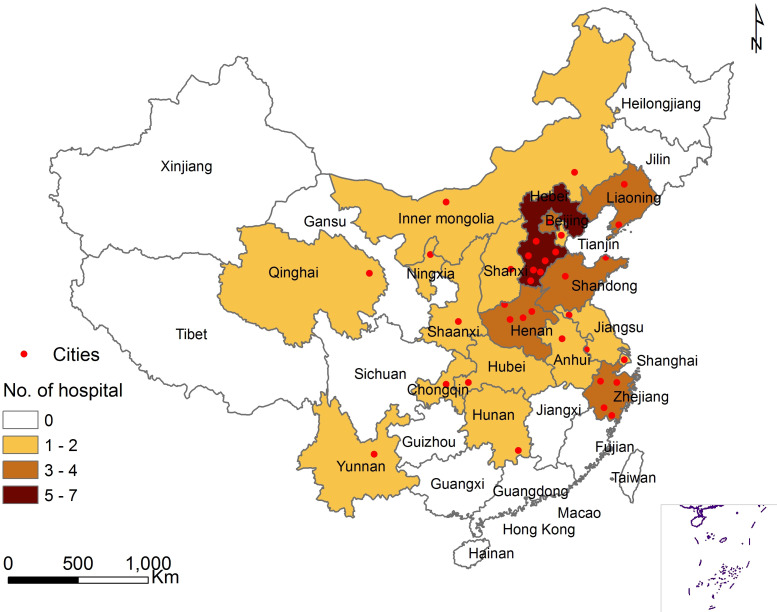

In 201 hospitals of the CNSR-III study, the steering committee of ICONS chose hospitals nationwide to represent the population from each region of east, south, west, north and centre of Mainland China. Fifty-two hospitals with the experience of cognition and sleep research were invited initially and 40 hospitals with qualified research capability and proved commitment to the study were ultimately selected. The complete list of ICONS members and sites could be found in online supplementary appendix S1, including 35 grade III hospitals (usually central hospitals for certain city or district) and five grade II hospitals (usually hospitals serving several communities). Figure 1 presented the geographical locations of all participating sites.

Figure 1.

The geographical locations of participating sites in ICONS. AIS, acute ischaemic stroke; TIA, transient ischaemic attack. Xiaoling Liao illustrated the figure 1.

svn-2020-000359supp001.pdf (21KB, pdf)

The primary aim of this study is to investigate the occurrence and associated factors of cognitive impairment and sleep disorder after AIS or TIA.

Patient enrolment

Between August 2015 and January 2018, in 40 selected sites that joined both CNSR-III and ICONS study, all patients participating in CNSR-III study were screened. If the patient met the criteria of ICONS study and signed informed consent, the patient would be also enrolled to the ICONS study.

The inclusion criteria of ICONS were same as CNSR-III, including: age older than 18 years; in-hospital AIS or TIA patients within 7 days after onset. However, the following exclusion criteria were added to ICONS, including: prior diagnosis of cognitive impairment, schizophrenia or psychosis disease; illiterate patients; and concomitant neurological disorders that interfere with cognitive or sleep evaluation, for example, severe aphasia defined as National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) item 9>2, visual impairment, hearing loss, dyslexia, severe unilateral neglect or consciousness disorders. AIS and TIA were defined according to the WHO criteria and confirmed by brain MRI or CT.17 18 Cerebral infarction on MRI or CT without symptoms and signs were excluded.

Baseline data collection and data management

The baseline data collection and processing methods of the ICONS study were same as that of the CNSR-III study.17 The information was collected including patient demographics, education level, occupation, medical history, risk factor of stroke assessment, laboratory tests and NIHSS score, and in addition to all information in the CNSR-III study, patients enrolled in the ICONS study were supplemented with medical history information including cognitive impairment, insomnia, apnoea and restless legs syndrome. For physical examination, measurement of neck circumference was added.

An electronic data capture system (EDC) was developed by Zhinantech company and used for data collection. It provided the opportunity of simultaneous automatic data check for completeness and logical correction of the uploaded data and would be better to improve the data quality. Independent data monitoring was performed through EDC by an independent contract research organisation throughout the study period. All data were deidentified before data analysis to protect patient confidentiality.

Biological sample and imaging collection

Biological sample and imaging collection were also same as the CNSR-III study.17 Blood samples were collected within 24 hours of admission, at 3 months and 12 months after stroke. Urine samples were collected at the first day of enrolment (within 24 hours) and 3-month follow-up. In ICONS study, MRI was recommended for all patients, including diffusion-weighted imaging with apparent diffusion coefficient maps, T1 weighted, T2 weighted, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, T2*/susceptibility-weighted imaging and magnetic resonance angiography. All MRI image data were collected in DICOM format on discs and sent to the image research centre in Beijing Tiantan Hospital for centralised quality control, privacy removal, standardised naming and double-blind manual interpretation analysis. If interpretation is in doubt, mediation analysis will be conducted by the committee of imaging experts.

Follow-up data collection and data management

Information including functional status, cardiovascular/cerebrovascular events, compliance of recommended secondary prevention medication and risk factor control was queried at 3 months, 6 months and 1–5 year annually follow-up by trained research coordinators together with CNSR-III study.17 In addition to those above, patients enrolled in the ICONS study were supplemented with the following information.

At 2 weeks or discharge, 3 months and 12 months, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA),19 20 Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index,21 Epworth Sleeping Scale,22 Anxiety Disorder-7,23 Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),24 Stroke Impact Scale and general 10 m walking speed test were evaluated face to face.25 26 All tests above were administered by trained examiners.

At 6 months, if patients could cooperate, comprehensive neuropsychological assessment would be performed face to face. The scales including MoCA, Auditory Verbal Learning Test, Symbol Digit Modalities Test, Verbal Fluency Test, Boston Naming Test, Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, Stroop Color-Word Test-Chinese version, Chinese modified version of the Trail Making Test-A and B, PHQ-9, Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline and activities of daily living. All tests were administered by trained examiners.

In the medication survey at each follow-up point, antidementia drugs, antidepressant drugs and insomnia treatment drugs were added in ICONS. The list of antidementia drug collection information includes donepezil, memantine hydrochloride, rivastigmine and galantamine. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and selective serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors antidepressant drugs were both collected., and the list of insomnia treatment drugs included 17 commonly used drugs, such as diazepam, estazolam, alprazolam, zolpidem tartrate and zopiclone.

Statistical analysis

The processing method for dropout were same as that of the CNSR-III study.17 Patients who were not eligible at the baseline or could not complete the scale evaluation at 2 weeks were excluded from the study. The association of most imaging and biological markers with the occurrence of cognitive impairment or sleep disorder will be performed by univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression model and HRs with their 95% CIs will be evaluated. For the outcome of poor functional outcome, univariate and multivariate logistic regression will be performed and ORs with their 95% CI will be evaluated.

In this article, the analyses focused on the baseline characteristics. Categorical variables were presented as percentages and continuous variables as mean with SD or median with IQR. Comparison of baseline variables among different groups were performed using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and t test or Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. The level of significance was p<0.05 (two sided). All analyses were conducted with SAS V.9.4.

Results

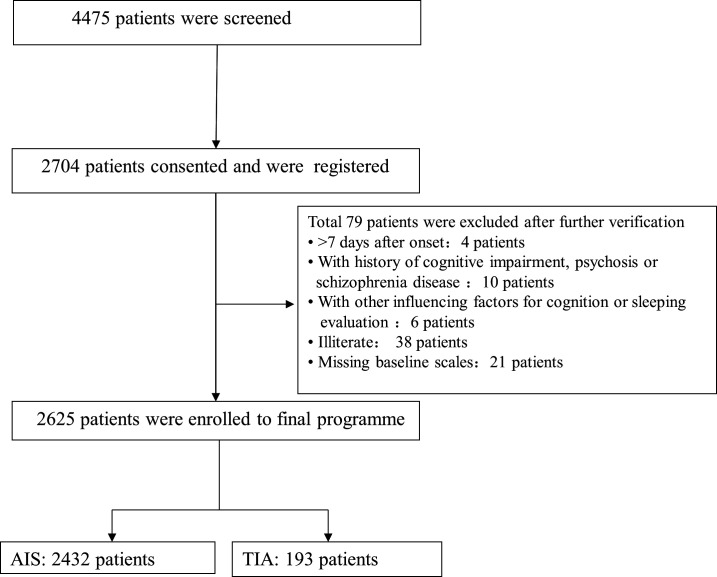

The patient recruitment phase had been completed. Between August 2015 and January 2018, 4475 patients who were enrolled to the CNSR-III study in 40 participating sites were screened for the ICONS study. A total 2704 patients consented and were registered in EDC at first. Moreover, a total of 79 patients were excluded after further verification. Finally, a total of 2625 patients who were eligible and had completed baseline scale evaluation at 2 weeks entered the final programme. A percentage of 92.65 patients were AIS and 7.35% patients were TIA. The detailed patient enrolment flow chart was shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of patient enrolment in ICONS. AIS, acute ischaemic stroke; ICONS, Impairment of CognitiON and Sleep after acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack in Chinese patients; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Baseline characteristics of the included patients are presented in tables 1 and 2. Overall, 72.38% patients were male, and the average age was 61.04 years. Among all enrolled patients, 35.85% were current smoker and 6.21% were heavy drinker. A percentage of 33.79 had a high school or above of education level. A percentage of 22.82 had diabetes, 62.55% had hypertension and 22.13% had a past history of stroke. The median time from symptom onset to enrolment was 1 day. Median NIHSS score was 3 in AIS patients.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics of ICONS patients

| Baseline variables | All patients (N (%)) n=2625 |

AIS (N (%)) n=2432 |

TIA (N (%)) n=193 |

P value |

| Gender male | 1900 (72.38) | 1774 (72.94) | 126 (65.28) | 0.022 |

| Average age (years) | 61.04±10.85 | 60.95±10.78 | 62.10±11.67 | 0.160 |

| Race (Han) | 2543 (96.88) | 2351 (96.67) | 192 (99.48) | 0.028 |

| Marital status (married) | 2483 (94.59) | 2298 (94.49) | 185 (95.85) | 0.42 |

| Living condition before (alone) | 155 (5.90) | 144 (5.92) | 11 (5.70) | 0.90 |

| Education level | 0.039 | |||

| Elementary or below | 675 (25.71) | 638 (26.23) | 37 (19.17) | |

| Middle school | 940 (35.81) | 867 (35.65) | 73 (37.82) | |

| High school or above | 887 (33.79) | 809 (33.26) | 78 (40.41) | |

| Unknown | 123 (4.69) | 118 (4.85) | 5 (2.59) | |

| Family monthly income per capita | 0.23 | |||

| <700 yuan | 95 (3.62) | 92 (3.78) | 3 (1.55) | |

| 700~2300 yuan | 1135 (43.24) | 1047 (43.05) | 88 (45.60) | |

| >2300 yuan | 933 (35.54) | 859 (35.32) | 74 (38.34) | |

| Unknown | 462 (17.60) | 434 (17.85) | 28 (14.51) | |

| Occupation | 0.005 | |||

| Employed | 1475 (56.19) | 1379 (56.70) | 96 (49.74) | |

| Unemployed | 238 (9.07) | 212 (8.72) | 26 (13.47) | |

| Retirement | 766 (29.18) | 699 (28.74) | 67 (34.72) | |

| Unknown | 146 (5.56) | 142 (5.84) | 4 (2.07) | |

| Current smoker | 941 (35.85) | 890 (36.60) | 51 (26.42) | 0.005 |

| Secondhand smoking | 416 (15.85) | 385 (15.83) | 31 (16.06) | 0.93 |

| Heavy drinker (>60 g/day) | 163 (6.21) | 154 (6.33) | 9 (4.66) | 0.35 |

| Physical activity | 1661 (63.28) | 1532 (62.99) | 129 (66.84) | 0.29 |

ICONS, Impairment of CognitiON and Sleep after acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack in Chinese patients.

Table 2.

Baseline medical history and clinical characteristics of ICONS patients

| Baseline variables | All patients (N (%)) n=2625 |

AIS (N (%)) n=2432 |

TIA (N (%)) n=193 |

P value |

| Medical history | ||||

| Diabetes | 599 (22.82) | 562 (23.11) | 37 (19.17) | 0.21 |

| Hypertension | 1642 (62.55) | 1530 (62.91) | 112 (58.03) | 0.18 |

| Lipid metabolism disorders | 259 (9.87) | 234 (9.62) | 25 (12.95) | 0.14 |

| Stroke history | 581 (22.13) | 534 (21.96) | 47 (24.35) | 0.44 |

| Cerebral infarction | 555 (21.14) | 509 (20.93) | 46 (23.83) | 0.34 |

| Intracranial cerebral haemorrhage | 35 (1.33) | 32 (1.32) | 3 (1.55) | 1.00 |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 5 (0.19) | 4 (0.16) | 1 (0.52) | 0.32 |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 88 (3.35) | 64 (2.63) | 24 (12.44) | 0.001 |

| Heart disease | 356 (13.56) | 327 (13.45) | 29 (15.03) | 0.54 |

| Coronary heart disease | 296 (11.28) | 270 (11.10) | 26 (13.47) | 0.32 |

| Heart failure | 9 (0.34) | 9 (0.37) | 0 (0.00) | 1.00 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 76 (2.90) | 72 (2.96) | 4 (2.07) | 0.48 |

| Others | 17 (0.65) | 15 (0.62) | 2 (1.04) | 0.82 |

| Carotid artery stenosis | 18 (0.69) | 15 (0.62) | 3 (1.55) | 0.13 |

| Epilepsy | 7 (0.27) | 7 (0.29) | 0 (0.00) | 1.00 |

| Sleep apnoea | 34 (1.30) | 29 (1.19) | 5 (2.59) | 0.098 |

| Median time from symptom onset to enrolment (day) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | 0.031 |

| Median NIHSS score (IQR) | 3 (1–5) | 3 (1–5) | 0 (0–1) | 0.001 |

ICONS, Impairment of CognitiON and Sleep after acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack in Chinese patients; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Discussion

The ICONS study had collected comprehensive baseline information, including comprehensive imaging and biological samples. All laboratory tests, imaging and biomarker information were under the centralised unified evaluation. Benefit from the EDC platform, the quality of the data had been highly improved. The overall completion of the baseline data was very good, and the missing values were controlled within 1%.

The ICONS study was the first prospective national registry study for cognitive impairment and sleep disorders after AIS or TIA in an inpatient population in China. It will help us to see whether PSCI and sleep disorders of the Chinese population have different characteristics and associated factors from those of the western populations. Compared with previous studies, ICONS study has the advantage of combining brief and comprehensive neuropsychological tests with longer and more frequent face-to-face follow-ups, and by taking advantage of the CNSR-III research platform, the patients will be followed for clinical outcomes by telephone annually over 5 years, which is helpful to investigate the impact of PSCI or sleep disorder on long-term clinical outcomes. This study may promote the Chinese doctors to identify and intervene cognitive impairment and sleep disorder after AIS/TIA. This may help to further improve the quality of life of patients and relieve the stroke burden of china.

Of course, we need to explain that the selected population of this study could not represent all AIS/TIA populations. The cognitive evaluation scale used in this study is the MOCA scale, which requires a relatively higher degree of patient cooperation. So as we introduced in the research method, some patients with severe physical disabilities, aphasia or consciousness disorders were excluded from this study. The patients selected in this study were mainly mild ischaemic stroke or TIA patients. However, the mild AIS or TIA population may be the stroke population that we should pay more attention to. Their physical or language disabilities are relatively mild, so the impact of cognitive impairment or sleep disorder on their quality of life is relatively more prominent.

There are several limitations of ICONS. First, comprehensive neuropsychological assessment was not designed for all time points and only performed at the 6-month follow-up for some patients who were able to cooperate. Second, the two scales for sleep quality evaluation used in our study were both only self-reported questionnaires. Third, the selected sites in this study mostly represented the hospitals with more medical resources and expertise than the low-level hospitals.

In conclusion, the ICONS study is a large-scale nationwide prospective registry to investigate occurrence and the longitudinal changes of cognitive impairment and sleep disorder after AIS or TIA. Data from this registry may also provide opportunity to evaluate associated factors of cognitive impairment or sleep disorder after AIS or TIA and their impact on clinical outcome.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the centres and all the members participated in the Impairment of CognitiON and Sleep after acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack in Chinese patients study.

Footnotes

Contributors: YW had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: YW, XL, CW and HL. Supplying patients: LZ, NZ, YY and JJ. Drafting of the manuscript: XL, LZ and NZ. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: YW, JS and HL. Statistical analysis: YP and XX. Study supervision and organisation of the project: YW, XM, CW, YW, XZ and HL.

Funding: This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (Grant No. 2016YFC0901001, 2016YFC0901002, 2017YFC1310901, 2017YFC1310902) and Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission(Grant No. D151100002015003).

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on the map(s) in this article does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The ethics committee at Beijing Tiantan Hospital approved the study (No. KY2015-001-01) and written informed consent is obtained from all participants.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Strong K, Mathers C, Bonita R. Preventing stroke: saving lives around the world. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:182–7. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70031-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fride Y, Adamit T, Maeir A, et al. What are the correlates of cognition and participation to return to work after first ever mild stroke? Top Stroke Rehabil 2015;22:317–25. 10.1179/1074935714Z.0000000013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Birkbak J, Clark AJ, Rod NH. The effect of sleep disordered breathing on the outcome of stroke and transient ischemic attack: a systematic review. J Clin Sleep Med 2014;10:103–8. 10.5664/jcsm.3376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kwon HS, Lee D, Lee MH, et al. Post-Stroke cognitive impairment as an independent predictor of ischemic stroke recurrence: PICASSO sub-study. J Neurol 2020;267:688–93. 10.1007/s00415-019-09630-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim KT, Moon H-J, Yang J-G, et al. The prevalence and clinical significance of sleep disorders in acute ischemic stroke patients-a questionnaire study. Sleep Breath 2017;21:759–65. 10.1007/s11325-016-1454-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Swartz RH, Bayley M, Lanctôt KL, et al. Post-Stroke depression, obstructive sleep apnea, and cognitive impairment: rationale for, and barriers to, routine screening. Int J Stroke 2016;11:509–18. 10.1177/1747493016641968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu S, Wu B, Liu M, et al. Stroke in China: advances and challenges in epidemiology, prevention, and management. Lancet Neurol 2019;18:394–405. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30500-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang W, Jiang B, Sun H, et al. Prevalence, Incidence, and Mortality of Stroke in China: Results from a Nationwide Population-Based Survey of 480 687 Adults. Circulation 2017;135:759–71. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sun J-H, Tan L, Yu J-T. Post-Stroke cognitive impairment: epidemiology, mechanisms and management. Ann Transl Med 2014;2:80. 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.08.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhou DHD, Wang JYJ, Li J, et al. Frequency and risk factors of vascular cognitive impairment three months after ischemic stroke in China: the Chongqing stroke study. Neuroepidemiology 2005;24:87–95. 10.1159/000081055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ding M-Y, Xu Y, Wang Y-Z, et al. Predictors of cognitive impairment after stroke: a prospective stroke cohort study. J Alzheimers Dis 2019;71:1139–51. 10.3233/JAD-190382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mims KN, Kirsch D. Sleep and stroke. Sleep Med Clin 2016;11:39–51. 10.1016/j.jsmc.2015.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wennberg AMV, Wu MN, Rosenberg PB, et al. Sleep disturbance, cognitive decline, and dementia: a review. Semin Neurol 2017;37:395–406. 10.1055/s-0037-1604351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ramos AR, Dong C, Elkind MSV, et al. Association between sleep duration and the Mini-Mental score: the Northern Manhattan study. J Clin Sleep Med 2013;9:669–73. 10.5664/jcsm.2834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Virta JJ, Heikkilä K, Perola M, et al. Midlife sleep characteristics associated with late life cognitive function. Sleep 2013;36:1533–41. 10.5665/sleep.3052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bucks RS, Olaithe M, Eastwood P. Neurocognitive function in obstructive sleep apnoea: a meta-review. Respirology 2013;18:61–70. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02255.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang Y, Jing J, Meng X, et al. The third China national stroke registry (CNSR-III) for patients with acute ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack: design, rationale and baseline patient characteristics. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2019;4:158–64. 10.1136/svn-2019-000242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stroke--1989. Recommendations on stroke prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Report of the WHO Task Force on Stroke and other Cerebrovascular Disorders. Stroke 1989;20:1407–31. 10.1161/01.STR.20.10.1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:695–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wen H-B, Zhang Z-X, Niu F-S, et al. [The application of Montreal cognitive assessment in urban Chinese residents of Beijing]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2008;47:36–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991;14:540–5. 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Duncan PW, Lai SM, Bode RK, et al. Stroke impact Scale-16: a brief assessment of physical function. Neurology 2003;60:291–6. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000041493.65665.D6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peters DM, Fritz SL, Krotish DE. Assessing the reliability and validity of a shorter walk test compared with the 10-Meter walk test for measurements of gait speed in healthy, older adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2013;36:24–30. 10.1519/JPT.0b013e318248e20d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

svn-2020-000359supp001.pdf (21KB, pdf)