Abstract

The human body hosts vast microbial communities, termed the microbiome. Less well known is the fact that the human body also hosts vast numbers of different viruses, collectively termed the ‘virome’. Viruses are believed to be the most abundant and diverse biological entities on our planet, with an estimated 1031 particles on Earth. The human virome is similarly vast and complex, consisting of approximately 1013 particles per human individual, with great heterogeneity. In recent years, studies of the human virome using metagenomic sequencing and other methods have clarified aspects of human virome diversity at different body sites, the relationships to disease states and mechanisms of establishment of the human virome during early life. Despite increasing focus, it remains the case that the majority of sequence data in a typical virome study remain unidentified, highlighting the extent of unexplored viral ‘dark matter’. Nevertheless, it is now clear that viral community states can be associated with adverse outcomes for the human host, whereas other states are characteristic of health. In this Review, we provide an overview of research on the human virome and highlight outstanding recent studies that explore the assembly, composition and dynamics of the human virome as well as host–virome interactions in health and disease.

Subject terms: Bacteriophages, Virology, Microbiome, Metagenomics

The human body hosts vast numbers of different viruses, collectively termed the virome. In this Review, Liang and Bushman provide an overview of research on the human virome and highlight recent studies that explore the assembly and composition of the human virome as well as host–virome interactions in health and disease.

Introduction

We are becoming accustomed to the idea that healthy humans are colonized by a rich diversity of microorganisms — the microbiome. However, less well known is that healthy humans are also colonized by a remarkable diversity of viruses — the virome. The human virome comprises bacteriophages (phages) that infect bacteria, viruses that infect other cellular microorganisms such as archaea, viruses that infect human cells and viruses present as transients in food1–7.

Centuries of medical research have linked infection by specific viruses with characteristic disease states; however, the nature and importance of whole viral populations were mostly not appreciated until the development of advanced DNA sequencing methods that could report the structures of whole communities. Untargeted sequencing of purified viral samples, termed ‘shotgun sequencing’, was first applied to environmental viral populations in 2002 by Breitbart et al. Viral particles were prepared from seawater, and then shotgun metagenomic sequencing was employed to characterize the viral communities present8, revealing highly abundant and diverse phage genomes, as well as a large proportion of viral ‘dark matter’ (that is, sequences that looked like nothing in available databases). The next year, the same research group carried out the first study of whole viral communities from human faeces1, again revealing rich and diverse viral populations, and emphasizing how little of this diversity had been studied previously. Since then, similar methods have been applied in many studies of virome populations, providing a rich picture of the associations of the human virome with health and disease, and continuing to emphasize the expanse of viral dark matter (reviewed in refs9,10).

The discovery of so much dark matter is not surprising, given that seawater has ~107 virus-like particles (VLPs) per millilitre and faeces ~109 VLPs per gram. In these studies, particles that look like viral particles are not commonly verified as replication competent; thus, the term VLP is used to reflect the fact that we are uncertain that these particles are replication-competent viruses, although for many it seems likely. These vast populations, inferred to be mostly unstudied phages, are extremely diverse in the number of types as well as overall numbers of particles. Furthermore, in a few cases, viral lineages have been shown to evolve rapidly, also contributing to the observed rich sequence variation4. The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Genomes database contains only 10,462 complete viral genome sequences (as of February 2021), a tiny fraction of the global diversity. Thus, studying the virome is exciting for the extent of the novelty in every experiment, but also daunting for the analytical challenges.

Viral populations vary greatly across the human body. The human gut contains the most abundant populations, and these have been the most studied. This site is rich in cells of both the human gut and prokaryotic microbiota, providing a rich variety of hosts for viral growth. Most other sites have sparser microbiota, at least in healthy individuals, and so sparser viral populations as well; however, recent work has defined rich viral populations at many locations throughout the human body. A high degree of inter-individual variation is seen in the human virome, paralleling findings from bacterial and fungal communities, raising questions of to what extent inter-individual differences in phenotypes are attributable to differences in the virome (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of viral population alterations in human disorders

| Human disease | Sample | Major virome alteration | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe acute malnutrition | Faeces | Reduced viral diversity | 102 |

| Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis | Faeces | Increased Caudovirales richness | 14 |

| Crohn’s disease | Faeces and biopsies | Moderate alterations | 152 |

| AIDS | Faeces | Increased enteric adenoviruses | 30 |

| Type 1 diabetes | Faeces | Reduced viral diversity | 16 |

| Hypertension | Faeces | Erwinia phage ΦEaH2 and Lactococcus phage 1706 may be associated with hypertension | 18 |

| Type 2 diabetes | Faeces | Increased putative phage scaffolds | 153 |

| DOCK8 deficiency | Skin swabs | Increased skin virome, especially human papillomavirus | 71 |

| Colorectal cancer | Faeces | Increased viral diversity | 19 |

| Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis | Faeces | Increased Caudovirales abundance | 11 |

| Type 1 diabetes during pregnancy | Faeces | Increased picobirnaviruses and tobamoviruses | 17 |

| Bacterial vaginosis | Vaginal swabs | Viral population structures correlated with bacterial vaginosis | 74 |

| Early-diagnosed Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis | Gut biopsies | Increased Hepadnaviridae and Hepeviridae; reduced Polydnaviridae, Tymoviridae and Virgaviridae | 154 |

| Coeliac disease autoimmunity | Faeces | Increased enteroviruses | 145 |

| Crohn’s disease | Faeces | The virulent phages are replaced with temperate phages | 13 |

| Ulcerative colitis | Gut biopsies | Increased Caudovirales, phage and bacteria virulence functions, and loss of viral–bacterial correlations | 15 |

| HIV viraemia | Seminal fluid | Increased human cytomegalovirus | 75 |

| Very early-onset inflammatory bowel disease | Faeces | Increased ratio of Caudovirales to Microviridae | 12 |

| Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation | Faeces | Increased picobirnaviruses | 155 |

Recent studies have uncovered numerous factors that show associations with virome structure in addition to anatomical location, such as diet, age and geographic location of the individual sampled. Disease is another prominent influence, with emerging studies suggesting associations between virome structure and inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, hypertension and cancer11–19. Most studies have only reported associations of the virome and diseases — thus, more work is needed to understand the directions of causal relationships.

In this Review, we provide an overview of research on the human virome, focusing both on secure conclusions and on areas where additional work would be helpful. We first discuss the virome at different body sites in healthy humans. Next, we summarize nascent work on the origin of these populations, that is, the initial assembly of the human virome in neonates and infants after delivery. We then summarize data on interactions between the host and the virome, including links to disease states.

Human virome diversity

The number of bacterial cells associated with the human body is estimated to be roughly the same as the number of human cells, ~1013 in total20. One estimate suggests that each gram of metazoan tissue is associated, on average, with 3 × 109 bacteria21, and the complexity of these communities increases with body size22. VLP counts in humans reveal that the ratios between viruses and bacteria range from roughly 0.1 to 10, suggesting that the total number of viruses in the human body is of a similar order to the number of bacterial and human cells (reviewed in ref.10).

Viruses that are found in humans can be categorized by various features. Viral genomes can be either RNA or DNA, and either double-stranded or single-stranded. Genome sizes can be as low as a few kilobases or as large as hundreds of kilobases. All viruses have a protein shell (or capsid) surrounding the genome; viruses can also be enclosed in one or more lipid membranes. Viral particles can be classified according to their morphology — spherical (usually icosahedral), filamentous, bullet-shaped, pleomorphic or, for phages, tailed.

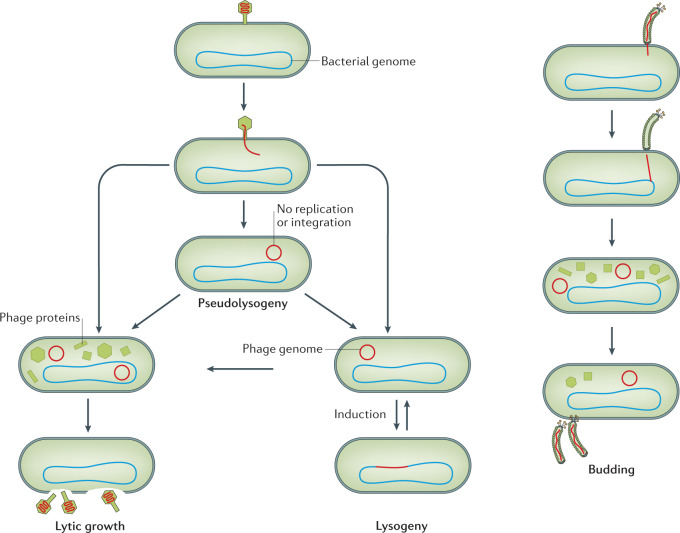

Most constituents of the human virome are inferred to be phages. This is an inference because, in most cases, the majority of sequences uncovered in a virome metagenomic sequencing experiment do not align with any information present in existing databases (Box 1), so it is unknown whether they are phages or some other virus types. The major taxa of phages are typically Caudovirales (tailed phages) and Microviridae (icosahedral non-tailed phages) of the group including phage ΦX174. Phages can have multiple relationships with their bacterial hosts, which constrain ideas about virome dynamics (Fig. 1). Lytic phages inject their nucleic acid into cells, leading to the synthesis of new viral components, the assembly of particles and the lysis of host cells, thus releasing progeny phages. Another mode of replication, carried out by temperate phages, can spare the host initially. Phages inject DNA into cells, after which the DNA can then become integrated into the host cell chromosome, forming a prophage. Prophages are maintained in a quiescent state by repressor proteins23. However, should conditions become unfavourable in the host cell — for example, by damage to DNA — phage DNA can become excised from the cellular chromosome leading to lytic growth, resulting in cell lysis and the production of viral progeny. Phages can also have other relationships with their hosts — one is pseudolysogeny, in which phage genomes persist as episomes without integration. In another mode, phages can bud out of infected cells, sparing the host cell from lysis and death.

Fig. 1. Phage replication cycles.

Phages can engage in four types of interactions with their hosts. In lytic growth, phages infect cells, produce viral macromolecules, assemble new particles and lyse host cells, thereby liberating new viral particles. In lysogenic growth, phages inject their genomes into cells, and the genomes then become integrated into the bacterial cellular chromosome. The prophage is maintained in a quiescent state until detection of a suitable induction signal, after which the phage genome becomes excised and goes on to direct lytic growth. Pseudolysogeny is a loose interaction between the phage and the host in which the phage genome is present in the bacterial cell but not actively directing lytic growth156. Lastly, some phages such as the filamentous phages (Inoviridae) can infect cells and preserve the infected cell while producing new phage progeny by budding.

Viruses that infect human cells are also an important part of the human virome. Some may cause acute infections, and others may establish long-term latency. Some viruses engage in benign colonization and cannot be associated with any particular disease, appearing to be long-term ‘passengers’ or ‘commensals’. Virome sequencing studies have unveiled some new lineages of human viruses that appear to be such commensals. For example, the Anelloviridae are a family of non-enveloped, single-stranded DNA viruses with quite small circular genomes (2–4 kb), including torque teno virus, torque teno mini virus and torque teno midi virus24–26. The genomes of viruses in this family encode what appears to be a single large protein, although gene expression has not been well studied because representative Anelloviridae have not yet been grown in pure culture. Anelloviridae are extremely diverse and can be found in many human body sites in a large fraction of all humans examined. No specific pathogenic effects have been linked to Anelloviridae so far (reviewed in refs27,28). Greater abundance of Anelloviridae has been found in individuals who are immunocompromised, including the recipients of lung transplants, individuals who are HIV positive and individuals on immunosuppressive medications owing to inflammatory bowel disease, indicating that Anelloviridae are normally under host immune control12,14,29–31. The newly discovered Redondoviridae are another family of small circular DNA viruses that appear to be widespread commensals commonly found in the respiratory tract32–34.

High inter-individual variation in the human virome has been reported in many studies (reviewed in refs9,10,35–38). However, within a healthy adult, the virome is usually relatively stable over time, paralleling stability in the cellular microbiome. For example, one study found that ~80% of viral contigs present persisted over a span of 2.5 years in the gut of one individual6. Another recent study tracked the gut virome of 10 individuals and found that >90% of recognizable viral contigs persisted in each individual over 1 year39. Studies on the oral virome revealed similar stability40,41. As discussed below, destabilization of the virome is often associated with disease states.

Box 1 Methods for studying the virome and the ‘dark matter’.

Isolating virus-like particles (VLPs) from samples of interest is the first step of a virome study. Focusing on VLPs avoids wasting resources on sequencing of non-viral nucleic acids. Filtration is a typical first step to purify VLPs, taking advantage of the fact that viruses are smaller than cells. Commonly used filter pore sizes include 0.2 μm and 0.45 μm. Filtering VLPs using 0.2-μm filters may lose large viruses158, whereas 0.45-μm filters may fail to retain some bacteria, as rare bacteria are <0.45 μm159. However, these bacteria appear to be uncommon in humans160,161, so use of 0.45-μm filters seems optimal. Unpublished comparisons of the two filter types in our laboratory showed no differences in contamination with bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences, supporting use of 0.45-μm filters.

Other fractionation steps can provide purer VLPs, but often at the expense of losing viral material. Chloroform extraction can be used to disrupt cell membranes, but results in the loss of membrane-enclosed viruses. Comparison of VLP samples purified from human stool with or without chloroform treatment showed that chloroform modestly reduced the recovery of contaminating bacterial DNA. For stool, membrane-enclosed viruses are rare51, so chloroform treatment may allow superior VLP purification.

For virome nucleic acid preparations, absolute yields are typically low, so multiple displacement amplification using phage Φ29 DNA polymerase has been used to increase DNA amounts. However, this can result in unequal amplification of different DNA forms, with small circular single-stranded DNA genomes amplifying preferentially162, distorting the ratios of different viral lineages163. Nevertheless, this is often the method of choice.

Numerous algorithms, databases and pipelines have been developed to process virome sequencing data, supporting quality control, read dereplication, contig assembly, viral identification, dark matter exploration and other steps (see the table). Despite steadily improving methods, it remains challenging to identify unstudied viruses in complex mixtures. Researchers can align individual sequence reads to databases, allowing identification of many candidate viruses, but attributions are often tentative and a large proportion of reads are typically not attributed to anything (that is, the ‘dark matter’). Assembling reads into contigs can provide more opportunity to explore previously unstudied sequences, but still a substantial fraction of contigs may find no attribution. Combining contig analysis with cataloguing gene types, and quantifying matches to gene families known to be viral, can help with attribution. Another helpful step can be assessing circularity in contigs, which commonly indicates completion of a metagenomic viral sequence (although this too can arise as an artefact of sequence repetition in a contig assembly).

No standards of dark matter annotation have been established, so the proportion of viral dark matter varies between studies. Values range from 13 to 95% (reviewed in refs9,35). In some cases, a community will be dominated by a well-known virus, driving down the unknown proportion, but commonly the unknown sequences represent a majority. A recent study constructed 33,242 viral species from 32 available public human virome studies, and >32,000 species were predicted to be phages, which is 12-fold higher than the phage number in the RefSeq database133. Thus, metagenomic sequencing boosts the discovery of novel viral genomes enormously. The vast majority of these probable viruses have yet to be grown in cell culture, classically a key step in establishing viral taxa, but today viral lineages are commonly specified as sequences before successful culture. As a consequence, for many members of the virome, it is not known what organisms serve as hosts for replication. The field is developing stand-alone virome-derived contig databases that can be updated regularly, such as the Gut Virome Database (GVD)133, which are useful for updating new discoveries and establishing standards for annotating the dark matter.

RNA viruses of the human virome have generally been less studied. RNA appears to be less stable in samples typically used for metagenomics, so the RNA viruses may be undersampled for technical reasons. Many studies focus on phages, and only a few RNA phages have been reported. Recent studies have highlighted a much greater diversity of RNA phages than previously thought in certain ecological niches164,165, focusing interest in further studies of RNA viruses.

Another challenge is DNA contamination in low-biomass samples. Studies have found that low levels of environmental DNA are usually present in laboratory reagents and that this DNA can predominate in samples that start with low amounts of nucleic acid88,166,167. The yields of nucleic acids from virome preparations are typically modest, so it is important to consider contamination when interpreting virome data. It is essential to analyse multiple blank samples in parallel with experimental samples so as to document the contamination background — commonly, at least a little of this background will annotate as viral, providing considerable challenges in data analysis. Sequence data from negative controls should be uploaded to databases along with virome data as part of the publication process. One useful tool for evaluating virome enrichment in virome sequence data is ViromeQC168. Overall, it is important to be mindful of the potential contribution of contamination and to carefully consider the potential impact on interpretation of experimental results.

Software for analysis of the human virome

| Name | Function | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| ViromeQC | Detects contamination | 168 |

| CD-HIT | Reads clustering | 169 |

| grabseqs | Public data downloading | 170 |

| VirSorter | Viral contig annotation | 171 |

| VirFinder | Viral contig annotation | 172 |

| FastViromeExplorer | Viral contig annotation | 173 |

| Metavir | Viral contig annotation | 174 |

| MetaPhinder | Viral contig annotation | 175 |

| ViromeScan | Viral contig annotation | 176 |

| vConTACT | Taxonomic classification | 177 |

| NCBI Virus | Database | 178 |

| UniProt | Database | 179 |

| pVOG | Database | 180 |

| Pfam | Database | 181 |

| Vfam | Database | 182 |

| Sunbeam | Analysis pipeline | 183 |

| Cenote-Taker | Analysis pipeline | 184 |

| VirusSeeker | Analysis pipeline | 185 |

| PHACT | Phage life cycle classification | 186 |

| PHASTER | Prophage prediction | 187 |

Virome of different body sites

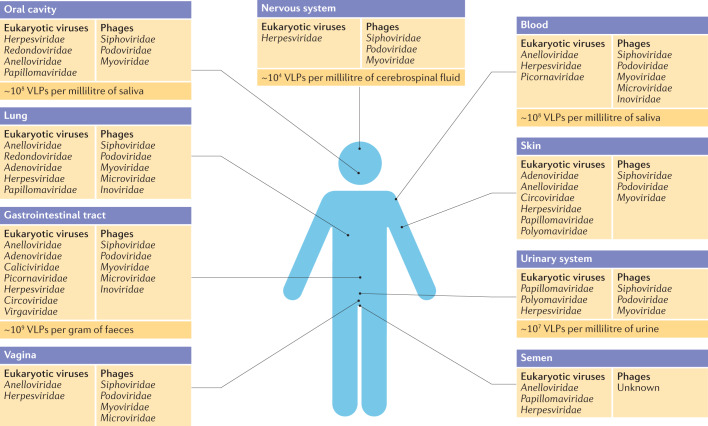

Numerous recent studies have characterized the human virome at different body sites, revealing rich populations at numerous locations (Fig. 2). Phages are distributed widely across the human body, and different anatomical sites may have quite different phage composition due to the presence of different host bacteria. The distribution of eukaryotic viruses also differs at different body sites. Some notable site-specific features are summarized below.

Fig. 2. The human virome at different body sites.

Summary of viruses found at each human body site. Viral types are summarized from published virome surveys2,9,10,29,32–38,40–48,53–74,76–78; those known at each body site are likely to increase as more human populations are surveyed and more viral types are discovered. In a few cases, viral lineages were excluded from the analysis because they likely represent contaminants or misattributions. These exclusions include mimivirus, phycodnavirus, marseillevirus, flaviviruses and poxviruses in blood, and baculovirus in the vagina. VLP, virus-like particle.

Gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract is commonly the most abundant site of viral colonization, reaching ~109 VLPs per gram of intestinal contents. Analysis of virome sequence data suggests that phages are the most abundant identifiable members of this population (reviewed in refs9,10,35–38). Visualization of stool VLPs using electron microscopy reveals that the majority of the phages belong to the order Caudovirales (tailed phages; reviewed in ref.10). Metagenomic sequencing of the human gut virome also indicated that Caudovirales is commonly predominant, along with the spherical Microviridae (reviewed in refs9,10,35–38).

It has been suggested that the most prevalent phage lineage in the human gut is often crAssphage (cross-assembly phage; members of the Caudovirales), specifically the short-tailed podoviruses, which infect bacteria of the phylum Bacteriodetes, common members of the gut microbiota42–46. crAssphages are commonly found in greater than 50% of human gut content samples and show a global distribution42–44. The abundance of crAssphages can be up to 90% of a human gut viral community42. Recently, the crAssphage ΦCrAss001 has been shown to infect Bacteroides intestinalis46, specifying one host species experimentally. Genomic analysis shows that phage genes important for lysogeny are rare or absent in crAssphage genomes45,46, and a lytic mode of replication has been suggested by infection studies in vitro46. However, curiously, proliferation of crAssphages does not appear to reduce the growth rate of their host cells in vitro46. One explanation is that crAssphages replicate via pseudolysogeny, in which the phage genome persists in a quiescent state as an episome (reviewed in ref.47), only rarely lysing the host cell.

The healthy human gut usually contains relatively low proportions of eukaryotic viruses. DNA viral lineages occasionally detected include Anelloviridae, Geminiviridae, Herpesviridae, Nanoviridae, Papillomaviridae, Parvoviridae, Polyomaviridae, Adenoviridae and Circoviridae (reviewed in ref.48). The most commonly detected RNA viruses include Caliciviridae, Picornaviridae, Reoviridae and some plant viruses that appear to originate in food, such as Virgaviridae2,12,49,50.

A notable pattern in viruses of the gut is that most residents, including both phages and human viruses, are not enveloped. This makes sense — lipid envelopes are unlikely to survive the detergent effects of bile salts, dehydration in the large intestine and the conditions of the environment outside the gut required for transmission via the faecal–oral route. A recent statistical analysis showed a significant association between faecal–oral transmission and the absence of a lipid envelope51. It will be of interest to investigate virus structure–transmission relationships in more detail and at additional human body sites.

Surprisingly, coronaviruses are an exception; despite possessing a lipid envelope, many coronaviruses are known to be transmitted via the faecal–oral route51. For severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), viral RNA has been widely reported in faeces, although the infectious potential of these viruses is uncertain52. One possible explanation is that coronaviruses such as SARS-CoV-2 can replicate in host cells of the lower gastrointestinal tract, so they do not need to traverse the entire gastrointestinal tract in order to appear in faeces; another possibility is that coronavirus particles are relatively stable for enveloped viruses. It will be useful to investigate these questions and clarify the infectivity of coronaviruses in faecal material systematically.

Oral cavity

The human oral cavity contains diverse viral communities as well as complex microbial populations. To date, saliva samples have been the primary source of material to characterize the oral virome40,53, revealing abundant viral populations. Additional oral microenvironments, such as dental plaque54, have also been studied, revealing high diversity in these environments as well. Staining of particles with a fluorescent dye that binds DNA, followed by visualization under a fluorescent microscope, shows approximately 108 VLPs per millilitre of saliva in healthy humans55. The most abundant taxon of phages in the oral virome is the Caudovirales40,41,56.

Common eukaryotic viruses in the oral cavity of healthy adults include Herpesviridae, Papillomaviridae, Anelloviridae and Redondoviridae32,57. Anelloviridae are the most common, but, surprisingly, the newly discovered Redondoviridae32 is the second most common virus family. However, it should be noted that prevalence measures are expected to be dependent on the sampling methods used, and the multiple displacement amplification steps typically used to amplify virome samples likely favour amplification of small DNA circles, potentially boosting detection of Anelloviridae and Redondoviridae. Reports so far put the prevalence of Redondoviridae at 2–15% in different populations32–34. As with Anelloviridae, whether Redondoviridae can cause disease is unknown. Preliminary studies show increased levels of redondoviruses in humans with periodontitis, patients who are critically ill in a medical intensive care unit and individuals with severe respiratory diseases32,33, although to date there is no evidence that redondoviruses are contributing to the disease states. Thus, both anelloviruses and redondoviruses appear to be common commensal viruses that might be undetected if not for developments in viral metagenomic sequencing methods.

Respiratory tract

Virome analyses have been performed on respiratory tract samples including sputum, nasopharyngeal swabs and bronchoalveolar lavage, showing that the healthy human lung and respiratory tract can be populated by large viral communities29,58–62. Among human DNA viruses, Anelloviridae has been reported to be the most prevalent family of DNA viruses, followed by Redondoviridae32. Additional eukaryotic viruses frequently detected include Adenoviridae, Herpesviridae and Papillomaviridae29,58–62. Phages are commonly found, including Caudovirales, Microviridae and Inoviridae29,58–62. Phages, like most of the cellular microbiota, even when found in the lung appear to be derived mainly from the abundant bacterial populations in the mouth and upper respiratory tract.

Blood

Viruses of blood have been studied closely, to understand human health and also to assess the safety of donor blood supplies. A pioneering study found viral particles in blood using electron microscopy and identified genomic sequences related to several eukaryotic viruses, including Anelloviridae63. Other recent studies have reported Herpesviridae, Marseilleviridae, Mimiviridae, Phycodnaviridae and Picornaviridae families, with proportions varying with the geographical site sampled64,65. Some of these findings illustrate the challenges of virome studies, where samples with low levels of authentic viruses may be prone to contamination (Box 1). It is important to note that Marseilleviridae, Mimiviridae and Phycodnaviridae are not known to replicate in human cells, and may represent environmental contamination. Phages belonging to the Myoviridae, Siphoviridae, Podoviridae, Microviridae and Inoviridae families have also been reported in blood, and, similarly, their origin is unclear (reviewed in refs48,66,67). Some of these studies did not perform viral particle enrichment prior to sequencing, so that prophage sequences integrated in bacterial genomes (rather than viral particles) may have been identified. A recent study reported that phage particles may be transported across gut epithelial cell layers by transcytosis, potentially reaching systemic circulation, with unknown consequences68. Thus, much remains to be learnt about the blood virome of healthy individuals; however, it does seem likely that at least Anelloviridae are common in blood and so must be expected to be present throughout the blood supply.

Skin

Compared with other body sites, the skin has a relatively low microbial biomass, which can, for some samples, make it difficult to distinguish the resident microbiome and virome from various forms of contamination. Metagenomic analysis of skin swabs revealed the presence of multiple eukaryotic virus families including Polyomaviridae, Papillomaviridae and Circoviridae69. In a recent DNA virome study with VLP enrichment70, ~95% of the viral sequences did not match a known viral genome and of the reads that could be assigned, many were associated with Caudovirales. This study also reported that the skin of healthy individuals harboured eukaryotic viruses including Adenoviridae, Anelloviridae, Circoviridae, Herpesviridae, Papillomaviridae and Polyomaviridae70. A notable expansion of these eukaryotic viruses was observed on the skin of individuals with primary immunodeficiencies, indicating the importance of immune surveillance in controlling viral colonization of the skin71.

Urogenital system

Urine samples from healthy humans have been reported to contain viruses in the region of 107 VLPs per millilitre72. Most of the identifiable viruses were phages; in addition, human papillomaviruses could be identified in >90% of subjects in some cohorts72,73. Virome analyses of healthy vaginal samples showed that the majority of identified viral sequences are derived from double-stranded DNA phages, with eukaryotic viruses contributing only 4% of total reads74. In seminal fluid, Anelloviridae, Herpesviridae and multiple genotypes of Papillomaviridae have been detected75. Thus, for these body sites we again see mixtures of viruses that replicate in human cells and viruses from the resident microbiota.

Nervous system

Little information is available on virome populations in the nervous system in healthy humans. A recent study estimated the VLP number at ~104 per millilitre of cerebrospinal fluid, with phages predominant, including Myoviridae, Siphoviridae and Podoviridae76. Herpesviridae were also detectable76. The clinical consequences of infection by herpesviruses in the nervous system have been well studied. Herpes simplex viruses, human cytomegalovirus and varicella zoster virus can establish latent infections in the central nervous system without symptoms77,78; these viruses can later be reactivated and produce viral particles78.

To summarize the virome over multiple human body sites, the human gut contains the most abundant viruses and has been the most frequently studied. Lower particle numbers are found at other body sites, but all seem to have detectable viral colonization. For sites with a resident microbiota, the viruses found are typically a mixture of viruses replicating in the local human cells and viruses infecting the local microbiota. The extent of circulation between sites is just starting to be assessed. Upper respiratory microbiota likely contribute much of the microbiome and virome to lower respiratory sites, at least for the phage population. Small circular DNA viruses (Anelloviridae and Redondoviridae) are common in respiratory samples and can also be found in faecal samples, although it is not known whether they appear in the gut because of replication in the gastrointestinal tract or swallowing of saliva. Anelloviridae but not Redondoviridae appear in blood, indicating systemic circulation. Even sites that are mostly cut off from normal microbial colonization, such as cerebrospinal fluid, show low levels of viruses including phages. How much of this colonization is due to true local viral replication, how much is due to systemic circulation of viruses and how much is due to technical mishaps associated with reagent contamination remains to be fully clarified. At all of these sites, unannotated ‘dark matter’ sequences are prominent, emphasizing how much remains to be learnt.

Establishment of the human virome

Timing of the first microbial colonization

The timing of virome establishment is linked to the question of establishment of the microbiome as a whole in human neonates and infants. Historically, the inability to culture microorganisms from samples from healthy deliveries has supported the idea that neonates are usually born sterile. Starting in 2014, several studies using metagenomic sequencing were carried out, leading to the proposal of a microbiome in the placenta, amniotic fluid and even the fetus, implying that microbial colonization may start in utero79–83. However, multiple recent studies have indicated that these detections of microorganisms are likely to be false positives due to experimental contamination, and that no placental microbiome is present before rupture of membranes and delivery84–88. This raises the question of when viral colonization takes place in human neonates. Vertical transmission of pathogenic viruses during pregnancy has been well documented for rubella virus, human cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex viruses, HIV, Zika virus and human papillomavirus (reviewed in refs89–92). However, these are characteristic of disease states and not health. Virome populations are robust in adults, so the question is when does the virome become established in healthy neonates.

The virome at delivery

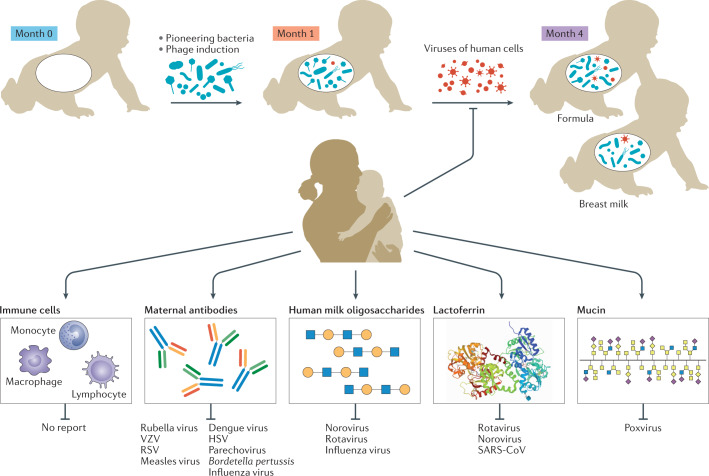

An early study of virome colonization sampled meconium shortly after delivery, and failed to find VLPs using epifluorescent microscopy but did report ~108 VLPs per gram at 1 week of life, suggesting that the neonate lacked a virome at birth but was quickly colonized93. In a study of amniotic fluid, no evidence was found for the existence of a virome in healthy pregnancies before delivery86. A later study of neonate stool samples, investigating both RNA and DNA viromes, taken a median of 2.6 days after birth found high diversity in the gut virome, consistent with rapid colonization after delivery50. Another metagenomic study using stool samples collected a median of 37 h after birth again showed high viral diversity, supporting rapid virome acquisition94. A more recent study of VLPs sampled a median of 17 h after birth reported that only 15% of samples were positive49. Thus, the picture that emerges is that neonates usually lack a detectable virome at birth, but are rapidly colonized after rupture of membranes and delivery (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Stepwise assembly of the paediatric virome.

Healthy neonates are typically born lacking a gut virome or microbiome. Pioneering bacteria colonize the gut of the neonate, such that infants have a detectable microbiome by month 1 of life. These bacteria commonly harbour integrated prophages, which occasionally induce prophages, providing a first wave of viral particles in the gut. Later, by month 4, more viruses that infect human cells can be detected. Infection with these viruses, some of which can be pathogenic, is inhibited by breastfeeding. Breastfeeding can also alter the types of phages present by altering the proportions of bacteria in the infant gut, which consequently alters the proportions of their phages. The protective effects of breast milk can be conferred by maternal immune cells or various macromolecules. These include maternal antibodies, human milk oligosaccharides, lactoferrin, mucin and gangliosides. The viral groups targeted by each antiviral factor in human breast milk are shown. Supporting references include refs49,111,113–121,157. HSV, herpes simplex viruses; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SARS-CoV; severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; VZV, varicella zoster virus.

The first detectable viruses — a predominance of phages

Several studies have investigated the nature of the human virome in samples taken very early in life. Recognizable early colonizers were mainly phages of the Siphoviridae, Podoviridae and Myoviridae families. Another phage family, the Microviridae, are less abundant during early life but rise in abundance with age49,50. Early bacterial colonizers commonly include Escherichia, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species95,96, and the phages of these bacteria are some of the most common early virome members.

A recent study investigated the production of the virome in gut samples of infants at 1 month of life and concluded that lytic phages were relatively rare49. Ongoing replication of lytic phages could not be detected in direct infection assays; viral sequences were annotated primarily as lysogenic phages and not lytic phages; and Microviridae and crAssphages, which usually do not form lysogens, were rare or absent during the first month in infant guts. Instead, prophage induction was found to contribute most of the gut virome. Bacterial strains were isolated from infants’ stools, and many were found to produce viral particles at high levels. The viruses that were produced could be detected as prophage sequences in the bacterial genome sequences. Sequences of the induced phages were also commonly found in the infant stool virome, and the abundance of each type of VLP in stool was positively correlated with the abundance of the host bacteria in the same sample.

These experiments suggested a high rate of phage induction in the infant gut, raising the question of what constitutes the inducing signal. DNA damage is the most studied signal (reviewed in ref.97). In vitro studies suggested that spontaneous induction rates may be relatively low98,99. Bacterial metabolites, nutrients and bile salts have all been shown to induce prophages in some models100,101. Thus, the signals (if there are any) are unclear and an interesting topic for future studies.

Later evolution of the paediatric virome

The paediatric virome continues to mature with age. Lytic phages appear to become more common later in life. For example, the crAssphages are mostly absent in the first month of life but become more prominent by month 4 (ref.49). The gut virome also often undergoes a shift from Caudovirales-dominated to Microviridae-dominated12,50,102.

Another question is the possible influence of the mode of delivery. A metagenomic analysis of faecal virome samples from 20 infants at 1 year of age compared spontaneous vaginal delivery with caesarean section and found that the birth mode resulted in distinctly different viral communities, with infants born by spontaneous vaginal delivery having greater viral diversity103. The effect of the delivery mode has been reproduced in some, but not all, cohorts in other studies49. Studies linking the birth mode and long-term health outcomes reported greater risk for various diseases, including asthma, obesity and diabetes, in children delivered by caesarean section, although the results are controversial and research is ongoing104–108. It may be useful to consider possible influences of the virome as well.

Colonization of infants with viruses infecting human cells

The viruses that replicate in human cells are also detected in metagenomic surveys of samples taken in early life. Gastroenteritis is one of the leading causes of childhood mortality, resulting in more than two million deaths every year109, and viral pathogens are primary causes (reviewed in ref.110), highlighting the importance of paediatric virome studies. Viruses that have been reported to be associated with childhood diarrhoea include rotavirus, astrovirus, calicivirus, picornavirus, polyomavirus and adenovirus (reviewed in ref.110). Less well known is the fact that these viruses are commonly found in healthy infant guts in metagenomic studies49,50. Other common viruses in healthy infant guts include parvovirus and anellovirus49,50.

Thus, recent data suggest that healthy infants are colonized in a stepwise fashion. In the first step, prophage induction from pioneering bacteria provides an initial population. Later, lytic phages become more common, and also viruses that replicate in human cells.

Factors that shape the human virome

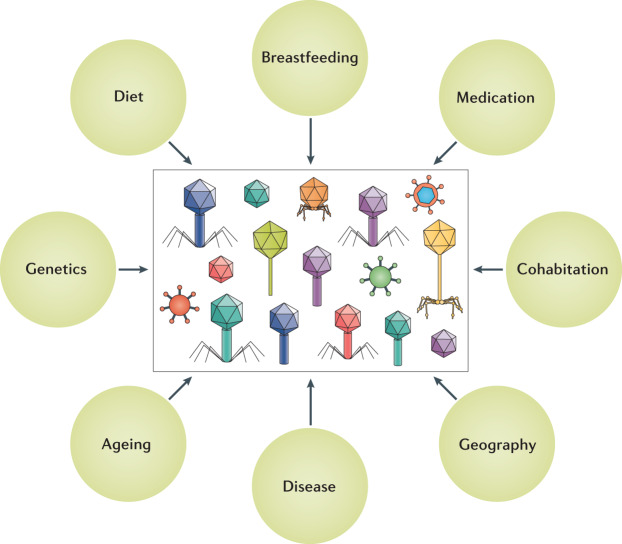

Numerous factors have been reported to influence the human virome and, ultimately, affect health (Fig. 4), starting in infancy and extending throughout the life of the individual.

Fig. 4. Factors that shape the human virome.

Major factors include the diet6, breast milk or formula feeding49,94, medications (including antibiotics and immunosuppressants)12,131, host genetics3,50,94,102,128,130, cohabitation53, geography49,65,131–134, presence of disease (Table 1) and ageing133.

Diet

The infant virome, including both phages and eukaryotic viruses, can be affected by diet. Breastfeeding is well established to reduce viral gastroenteritis and infant mortality (reviewed in refs111,112). A recent metagenomic virome study showed lower accumulation of animal cell viruses in guts of infants fed with breast milk49 (Fig. 3). The protective effect was seen in cohorts from both the United States and Botswana49. Viruses affected included Adenoviridae, Picornaviridae and Caliciviridae. Breast milk contains multiple components that protect children from intestinal infections, such as maternal antibodies, oligosaccharides and lactoferrin (reviewed in ref.111). These antiviral components have been reported to inhibit viruses, such as rotavirus, norovirus, enterovirus, influenza virus and SARS-CoV (reviewed in refs111,113–121). The phage population structure in infant stool can also be influenced by breastfeeding — specific bacteria are known to increase in abundance with breastfeeding, and in a recent report their phages were increased in abundance as well49. Alterations of the viral population in infant stool samples owing to breastfeeding has been proposed in another study, although the small sample size was a limitation94. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the infant virome may, in fact, be at least partially transmitted from the mother via breast milk122,123.

Diet has also been reported to affect the virome in adults. For example, comparison of the virome structure in adult subjects on two different controlled diets showed that individuals on the same diet showed more similar viral compositions than those on different diets6.

Host genetics and immunity

Intense interest has focused on the potential influence of human genetics on the microbiome, raising the linked question of the role of human genetics in programming the virome. Several studies of twins, comparing monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs, have suggested an influence of human genetics on microbiome composition because the monozygotic twins showed more similarity124–126. By contrast, a recent large-scale study of healthy adults (non-twins) reported little effect of genetics and emphasized environmental factors127. In studies of the infant virome, the gut virome compositions of co-twins were more similar than those between unrelated individuals50,94,102, but this similarity was not strongly affected by zygosity94,102, emphasizing the importance of the shared environment over human genetic composition. In an early study of adult twins, no greater similarity of virome samples was seen in twin pairs3. In a more recent study with a larger cohort of adult monozygotic twins, some were found to have greater similarity in virome composition compared with unrelated individuals, but in other co-twin pairs the microbiota and the virome had diverged to the degree that the twins were no longer notably similar128. Collectively, studies of the gut virome in twin pairs so far show similarities early in life, but not stronger similarities in monozygotic twins versus dizygotic twins, thus emphasizing the importance of shared environmental factors in colonization versus contributions of genetic make-up.

However, in inherited diseases such as primary immunodeficiencies, the effects of genetics on the virome are well established. In some cases, phenotypes of mutations in human genes can only be understood by considering the interaction with the virome. One drastic example involves epidermodysplasia verruciformis (also known as treeman syndrome, which is a rare heritable skin disease). In the presence of a mutation in TMC6 (EVER1) or TMC8 (EVER2), skin papillomaviruses replicate aggressively and cause massive inappropriate outgrowth of skin cells, resulting in treeman syndrome (reviewed in ref.129). Other primary immunodeficiencies may similarly allow specific viruses or microorganisms to replicate unchecked, resulting in distinctive disorders. The effects of immunodeficiencies on the skin virome were mentioned above; also, virome studies of individuals undergoing treatment for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID-X1) revealed distinctive outgrowths of several viral lineages in the gut130. An interesting question for future investigation is how much of the phenotypes of diverse human genetic diseases are a result of altered interactions with the normal virome.

Geography and stochastics of colonization

Large-scale virome studies have provided evidence that geographic location and stochastics of colonization have strong impacts on human virome variation. A study of human faecal samples from different regions within China reported variation of the phage population structure and found that geography had the strongest impact compared with other variables, including diet, ethnicity and medication131. Geography has been associated with the eukaryotic virus populations as well. An early study found geographic variation in eukaryotic viromes in children with diarrhoea from two locations within Australia, with differential prevalence of Adenoviridae and Picornaviridae132. A blood virome analysis of eukaryotic viruses in a Chinese population revealed a distinctive pattern for people living in the southern part of China65. Moreover, one study of the infant virome found a higher prevalence of viruses infecting human cells in cohorts of people of African descent than in cohorts from the United States49. A recent study collected public metagenomic data sets and built a virome database with >30,000 viral genomes, and found higher viral diversity in populations from non-western countries compared with populations from western countries133. Similar results were reported in another study134. Thus, effects of geography are quite prominent.

Additional factors

Additional factors have been tested and reported to influence the human virome. One study tested age using public data, and found that viral diversities in early life and in older individuals (>65 years of age) are lower than those in healthy adults (18–65 years of age), indicating another dimension of age-dependent patterns133. Effects of ethnicity and medication were also found in a large Chinese cohort131. Cohabitation is also a factor — in an early study, members of the same household shared more similarity in the oral virome compared with those from different households53, suggesting transmission of the virome via close contact.

Thus, nascent studies of factors affecting the virome highlight diet, geography, age and health status as major correlates of virome structure. Genetics is less clear, at least in studies so far of healthy twins. More studies of large cohorts with linked comprehensive metadata will be helpful going forward.

The virome in health and disease

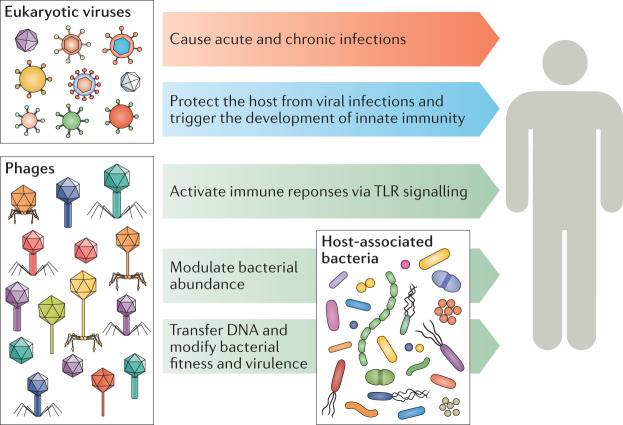

Virome populations can influence their human hosts in numerous ways. Eukaryotic viruses that infect human cells establish infections, trigger immune responses and, sometimes, cause diseases. Phages can affect the host indirectly via modulating of bacterial composition and bacterial fitness. Some phages and human cell viruses can be integrated into cells of their respective hosts, on occasion transferring new functionality to host cells. Some phages may also interact with human cells directly and trigger immune responses (Fig. 5). Recent examples of host–virome interactions in health and disease are discussed below (for reviews, see refs135,136).

Fig. 5. Host–virome interactions.

Eukaryotic viruses have both detrimental (red arrow) and beneficial (blue arrow) effects on host health. Phages interact with the host directly or indirectly via the host-associated bacterial community and pose undetermined effects (green arrow) on host health. Data based on refs68,137–144,149–151. TLR, Toll-like receptor.

Interactions between bacteria, phage and their human hosts

Relatively little is known about the impact of phage predation on human bacterial communities. A window on phage predation and host health is provided by phage therapy, in which phages are deliberately applied to human individuals to treat bacterial infections. As more drug-resistant bacteria are emerging, there is increased interest in this approach (reviewed in ref.137). Recently, several studies have used phage cocktails to treat bacterial infection in a few individuals, with apparent success (reviewed in ref.138) motivating larger clinical trials. Evidence that the phages are in fact creating evolutionary pressure on pathogenic bacteria in these studies comes from the observation that bacteria often mutated to become resistant to the therapeutic phage. Phages may even be useful to treat additional diseases. For example, a phage cocktail targeting adherent invasive Escherichia coli strains has been suggested recently as a treatment for Crohn’s disease139.

Phages can move DNA between cells and, thereby, introduce new functionality to bacterial genomes, which may modify bacterial fitness and virulence (reviewed in ref.140). In a recent study using a mouse model, the stool virome was analysed after antibiotic treatment, showing that there was an enrichment of phage-encoded genes for antibiotic resistance141, which increased resistance in the bacterial community.

Prophage induction can also lead to bacterial cell lysis, regulating bacterial abundance. A recent publication investigated diet-mediated prophage induction of human-associated bacterial strains in vitro, revealing that several common food compounds can inhibit bacterial growth by inducing prophages, including artificial sweeteners142.

Recent in vitro and animal studies indicated that phages may interact with the host immune system directly. Phages may be taken up by immune cells and trigger immune responses, without the mediation of bacteria, via Toll-like receptor (TLR) signalling. A recent publication reported that phages produced by pathogenic bacteria can be taken up by immune cells (dendritic cells, B cells and monocytes) in mice to induce type I interferon responses via TLR3 signalling143. Another study showed that interferon-γ (IFNγ)-producing CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were increased in mucosal sites in germ-free mice fed an E. coli phage isolated from the human gut144. Furthermore, this study also revealed that Lactobacillus, Escherichia and Bacteroides phages can stimulate the production of IL-12, IL-6, IL-10 and IFNγ via the nucleotide-sensing receptor TLR9 (ref.144). Collectively, the interactions among phages, bacteria and the host immune system likely have important roles in host immune homeostasis.

Human disease-associated virome signatures

Studies of interactions between the virome with human diseases are just starting. Of course, numerous individual viruses are well known to cause morbidity and mortality. Studies of whole viral populations have now also begun to show patterns associated with disease states. Some recent examples are described below.

The virome has been considered to be a potential trigger of autoimmune diseases. In one study, changes in viral populations were both directly and inversely associated with the development of paediatric type 1 diabetes16. Virome signatures have been associated with paediatric and adult inflammatory bowel disease in several studies11–15, including a reproducible expansion of Caudovirales and a reduction of Microviridae. Whether this is a consequence of altered dysbiotic bacterial populations or is more deeply involved in the disease process remains to be clarified. A metagenomic study showed that children with frequent exposure to enterovirus between 1 and 2 years of age have a higher risk of coeliac disease145. Recent studies revealed that the relationships between phages and bacterial populations may influence growth stunting in children146,147. Examples of proposed associations between diseases and viral population structure are listed in Table 1.

Studies using animal models have indicated that some eukaryotic viruses may even be beneficial to the host (reviewed in refs135,148). For example, persistent infection by a strain of murine norovirus can compensate for the absence of bacteria in gnotobiotic mice, allowing restoration of intestinal morphology and promoting lymphocyte differentiation149. Murine astrovirus protected immunodeficient mice from enteric norovirus infections through the induction of type III interferons in the intestinal epithelial barrier150. Depletion of murine gut viruses using an antiviral cocktail inhibited the development of the intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes, at least in part151. So far, all of these studies showing positive effects were performed in model organisms — it will be of interest to determine how much beneficial immune instruction may be directed by the virome in humans.

Thus, both phages and eukaryotic viruses can promote host health through interactions with the host immune system. However, virome studies using human cohorts suggest that dysbiosis of the virome is associated with multiple diseases. These studies emphasize the balance between beneficial and harmful roles of viral populations in humans and other organisms.

Conclusions and perspectives

The virome field has come a long way since the first paper in 2002 that reported metagenomic sequencing of a viral specimen. The methods for study have advanced, although there are still many challenges associated with working with metagenomic dark matter. Human virome population diversity and composition is being documented for many body sites — one consistent conclusion is that each individual harbours diverse and distinctive viral communities. Future studies are needed to clarify the DNA and RNA viromes at different anatomical sites and to link the alterations of viral composition to specific diseases. We now have a detailed picture of the stepwise nature of the assembly of the human virome after birth. The impact of viral colonization during early life on long-term health outcomes is still unknown and warrants careful study. Breastfeeding appears to have an important role during viral colonization; how the antiviral components in breast milk interact with the different components of the virome warrants further investigation. Emerging data indicate that factors that influence the human microbiome also often influence the virome as well, so that sorting out the influence of each will be a challenge going forward. Resident viruses are not only actively interacting with other microorganisms but also with the mammalian immune system. Many intriguing conclusions have so far only been obtained in animal studies or in vitro experiments, focusing attention on translation to studies in humans. Associations between alterations of virome and disease states are being identified more commonly, but in many cases causality and molecular mechanisms remain to be worked out. The vast world of the human virome is beginning to be understood, laying the ground work for numerous future studies of its importance.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank members of the Bushman laboratory for help and suggestions, and L. Zimmerman for artwork designs. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grants R61-HL137063, R01-HL113252), the Penn Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI 045008), the PennCHOP Microbiome Program and a Tobacco Formula grant under the Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement (CURE) programme (grant number SAP # 4100068710), and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation.

Glossary

- Temperate phages

Phages that are able to grow via both lytic and lysogenic replication pathways.

- Viral contigs

Contiguous sequences assembled from overlapping sequence reads, which are then annotated as whole or partial viral genomes.

- Multiple displacement amplification

A whole-genome amplification method, which starts by binding random primers to the template DNA and is then followed by strand displacement DNA synthesis performed by DNA polymerase, usually Φ29 DNA polymerase.

- Primary immunodeficiencies

A group of rare immune disorders caused by genetic defects.

- Meconium

The first stool of a neonate.

Author contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Microbiology thanks F. Maggi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Guanxiang Liang, Email: liangguanxiang@gmail.com.

Frederic D. Bushman, Email: bushman@pennmedicine.upenn.edu

References

- 1.Breitbart M, et al. Metagenomic analyses of an uncultured viral community from human feces. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:6220–6223. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.20.6220-6223.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang T, et al. RNA viral community in human feces: prevalence of a pathogenic viruses. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:0108–0118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reyes A, et al. Viruses in the faecal microbiota of monozygotic twins and their mothers. Nature. 2010;466:334–338. doi: 10.1038/nature09199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minot S, et al. Rapid evolution of the human gut virome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:12450–12455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300833110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minot S, Wu GD, Lewis JD, Bushman FD. Conservation of gene cassettes among diverse viruses of the human gut. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minot S, et al. The human gut virome: inter-individual variation and dynamic response to diet. Genome Res. 2011;21:1616–1625. doi: 10.1101/gr.122705.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minot S, Grunberg S, Wu GD, Lewis JD, Bushman FD. Hypervariable loci in the human gut virome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:3962–3966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119061109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breitbart M, et al. Genomic analysis of uncultured marine viral communities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14250–14255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202488399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aggarwala V, Liang G, Bushman FD. Viral communities of the human gut: metagenomic analysis of composition and dynamics. Mob. DNA. 2017;8:12. doi: 10.1186/s13100-017-0095-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shkoporov AN, Hill C. Bacteriophages of the human gut: the “known knknown” of the microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;25:195–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandes MA, et al. Enteric virome and bacterial microbiota in children with ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019;68:30–36. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang G, et al. Dynamics of the stool virome in very early-onset inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis. 2020;14:1600–1610. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clooney AG, et al. Whole-virome analysis sheds light on viral dark matter in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;26:764–778.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norman JM, et al. Disease-specific alterations in the enteric virome in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2015;160:447–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuo T, et al. Gut mucosal virome alterations in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2019;68:1169–1179. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-318131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao G, et al. Intestinal virome changes precede autoimmunity in type I diabetes-susceptible children. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E6166–E6175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706359114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim KW, et al. Distinct gut virome profile of pregnant women with type 1 diabetes in the ENDIA study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019;6:ofz025. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han M, Yang P, Zhong C, Ning K. The human gut virome in hypertension. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:3150. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakatsu G, et al. Alterations in enteric virome are associated with colorectal cancer and survival outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:529–541.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kieft TL, Simmons KA. Allometry of animal–microbe interactions and global census of animal-associated microbes. Proc. Royal. Soc. B. 2015;282:20150702. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.0702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherrill-Mix S, et al. Allometry and ecology of the bilaterian gut microbiome. mBio. 2018;9:e00319-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00319-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacob F, Sussman R, Monod J. On the nature of the repressor ensuring the immunity of lysogenic bacteria [French] C. R. Acad. Sci. 1962;254:4214–4216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishizawa T, et al. A novel DNA virus (TTV) associated with elevated transaminase levels in posttransfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;241:92–97. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi K, Iwasa Y, Hijikata M, Mishiro S. Identification of a new human DNA virus (TTV-like mini virus, TLMV) intermediately related to TT virus and chicken anemia virus. Arch. Virol. 2000;145:979–993. doi: 10.1007/s007050050689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ninomiya M, et al. Identification and genomic characterization of a novel human torque teno virus of 3.2 kb. J. Gen. Virol. 2007;88:1939–1944. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82895-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freer G, et al. The virome and its major component, anellovirus, a convoluted system molding human immune defenses and possibly affecting the development of asthma and respiratory diseases in childhood. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:686. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spandole S, Cimponeriu D, Berca LM, Mihăescu G. Human anelloviruses: an update of molecular, epidemiological and clinical aspects. Arch. Virol. 2015;160:893–908. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2363-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young JC, et al. Viral metagenomics reveal blooms of anelloviruses in the respiratory tract of lung transplant recipients. Am. J. Transpl. 2015;15:200–209. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monaco CL, et al. Altered virome and bacterial microbiome in human immunodeficiency virus-associated acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, et al. AIDS alters the commensal plasma virome. J. Virol. 2013;87:10912–10915. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01839-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbas AA, et al. Redondoviridae, a family of small, circular DNA viruses of the human oro-respiratory tract associated with periodontitis and critical Illness. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;25:719–729.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spezia PG, et al. Redondovirus DNA in human respiratory samples. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;131:104586. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lázaro-Perona F, et al. Metagenomic detection of two vientoviruses in a human sputum sample. Viruses. 2020;12:327. doi: 10.3390/v12030327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mirzaei MK, Maurice CF. Ménage à trois in the human gut: interactions between host, bacteria and phages. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017;15:397–408. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim ES, Wang D, Holtz LR. The bacterial microbiome and virome milestones of infant development. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Virgin HW. The virome in mammalian physiology and disease. Cell. 2014;157:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reyes A, Semenkovich NP, Whiteson K, Rohwer F, Gordon JI. Going viral: next-generation sequencing applied to phage populations in the human gut. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:607–617. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shkoporov AN, et al. The human gut virome is highly diverse, stable, and individual specific. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;26:527–541.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abeles SR, et al. Human oral viruses are personal, persistent and gender-consistent. ISME J. 2014;8:1753–1767. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abeles SR, Ly M, Santiago-Rodriguez TM, Pride DT. Effects of long term antibiotic therapy on human oral and fecal viromes. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0134941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dutilh BE, et al. A highly abundant bacteriophage discovered in the unknown sequences of human faecal metagenomes. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:1–11. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guerin E, et al. Biology and taxonomy of crAss-like bacteriophages, the most abundant virus in the human gut. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;24:653–664.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edwards RA, et al. Global phylogeography and ancient evolution of the widespread human gut virus crAssphage. Nat. Microbiol. 2019;4:1727–1736. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0494-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yutin N, et al. Discovery of an expansive bacteriophage family that includes the most abundant viruses from the human gut. Nat. Microbiol. 2018;3:38–46. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0053-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shkoporov AN, et al. ΦCrAss001 represents the most abundant bacteriophage family in the human gut and infects Bacteroides intestinalis. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07225-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sutton TDS, Hill C. Gut bacteriophage: current understanding and challenges. Front. Endocrinol. 2019;10:784. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rascovan N, Duraisamy R, Desnues C. Metagenomics and the human virome in asymptomatic individuals. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;70:125–141. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-102215-095431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang G, et al. The stepwise assembly of the neonatal virome is modulated by breastfeeding. Nature. 2020;581:470–474. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2192-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lim ES, et al. Early life dynamics of the human gut virome and bacterial microbiome in infants. Nat. Med. 2015;21:1228–1234. doi: 10.1038/nm.3950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bushman FD, McCormick K, Sherrill-Mix S. Virus structures constrain transmission modes. Nat. Microbiol. 2019;4:1778–1780. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0523-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zapor M. Persistent detection and infectious potential of SARS-CoV-2 virus in clinical specimens from COVID-19 patients. Viruses. 2020;12:1384. doi: 10.3390/v12121384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robles-Sikisaka R, et al. Association between living environment and human oral viral ecology. ISME J. 2013;7:1710–1724. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naidu M, Robles-Sikisaka R, Abeles SR, Boehm TK, Pride DT. Characterization of bacteriophage communities and CRISPR profiles from dental plaque. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pride DT, et al. Evidence of a robust resident bacteriophage population revealed through analysis of the human salivary virome. ISME J. 2012;6:915–926. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pérez-Brocal V, Moya A. The analysis of the oral DNA virome reveals which viruses are widespread and rare among healthy young adults in Valencia (Spain) PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0191867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baker JL, Bor B, Agnello M, Shi W, He X. Ecology of the oral microbiome: beyond bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25:362–374. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Willner D, et al. Metagenomic analysis of respiratory tract DNA viral communities in cystic fibrosis and non-cystic fibrosis individuals. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wylie KM, Mihindukulasuriya KA, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Storch GA. Sequence analysis of the human virome in febrile and afebrile children. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e27735. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clarke EL, et al. Microbial lineages in sarcoidosis a metagenomic analysis tailored for low-microbial content samples. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;197:225–234. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201705-0891OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abbas AA, et al. The perioperative lung transplant virome: torque teno viruses are elevated in donor lungs and show divergent dynamics in primary graft dysfunction. Am. J. Transplant. 2017;17:1313–1324. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abbas AA, et al. Bidirectional transfer of Anelloviridae lineages between graft and host during lung transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2019;19:1086–1097. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Breitbart M, Rohwer F. Method for discovering novel DNA viruses in blood using viral particle selection and shotgun sequencing. Biotechniques. 2005;39:729–736. doi: 10.2144/000112019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moustafa A, et al. The blood DNA virome in 8,000 humans. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006292. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu S, et al. Genomic analyses from non-invasive prenatal testing reveal genetic associations, patterns of viral infections, and Chinese population history. Cell. 2018;175:347–359.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Castillo DJ, Rifkin RF, Cowan DA, Potgieter M. The healthy human blood microbiome: fact or fiction? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019;9:148. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zárate S, Taboada B, Yocupicio-Monroy M, Arias CF. Human virome. Arch. Med. Res. 2017;48:701–716. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nguyen S, et al. Bacteriophage transcytosis provides a mechanism to cross epithelial cell layers. mBio. 2017;8:1874–1891. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01874-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Foulongne V, et al. Human skin microbiota: high diversity of DNA viruses identified on the human skin by high throughput sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hannigan GD, et al. The human skin double-stranded DNA virome: topographical and temporal diversity, genetic enrichment, and dynamic associations with the host microbiome. mBio. 2015;6:e01578-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01578-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tirosh O, et al. Expanded skin virome in DOCK8-deficient patients. Nat. Med. 2018;24:1815–1821. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Santiago-Rodriguez TM, Ly M, Bonilla N, Pride DT. The human urine virome in association with urinary tract infections. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garretto A, Miller-Ensminger T, Wolfe AJ, Putonti C. Bacteriophages of the lower urinary tract. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2019;16:422–432. doi: 10.1038/s41585-019-0192-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jakobsen RR, et al. Characterization of the vaginal DNA virome in health and dysbiosis. Viruses. 2020;12:1143. doi: 10.3390/v12101143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li Y, et al. Semen virome of men with HIV on or off antiretroviral treatment. AIDS. 2020;34:827–832. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ghose C, et al. The virome of cerebrospinal fluid: viruses where we once thought there were none. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:2061. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Meyding Lamade U, Strank C. Herpesvirus infections of the central nervous system in immunocompromised patients. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2012;5:279–296. doi: 10.1177/1756285612456234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McGavern DB, Kang SS. Illuminating viral infections in the nervous system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:318–329. doi: 10.1038/nri2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Aagaard K, et al. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci. Transl Med. 2014;6:237ra65. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Antony KM, et al. The preterm placental microbiome varies in association with excess maternal gestational weight gain. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;212:653.e1–653.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Prince AL, et al. The placental membrane microbiome is altered among subjects with spontaneous preterm birth with and without chorioamnionitis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016;214:627.e1–627.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.01.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Collado MC, Rautava S, Aakko J, Isolauri E, Salminen S. Human gut colonisation may be initiated in utero by distinct microbial communities in the placenta and amniotic fluid. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep23129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Martinez KA, et al. Bacterial DNA is present in the fetal intestine and overlaps with that in the placenta in mice. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0197439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Theis KR, et al. Does the human placenta delivered at term have a microbiota? Results of cultivation, quantitative real-time PCR, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and metagenomics. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2019;220:267.e1–267.e39. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lauder AP, et al. Comparison of placenta samples with contamination controls does not provide evidence for a distinct placenta microbiota. Microbiome. 2016;4:29. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0172-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lim ES, Rodriguez C, Holtz LR. Amniotic fluid from healthy term pregnancies does not harbor a detectable microbial community. Microbiome. 2018;6:87. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0475-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Leiby JS, et al. Lack of detection of a human placenta microbiome in samples from preterm and term deliveries. Microbiome. 2018;6:196. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0575-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]