Abstract

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is one of the most commonly performed weight-loss procedures, but how severe obesity and RYGB affect circulating HDL-associated microRNAs (miRNAs) remains unclear. Here, we aim to investigate how HDL-associated miRNAs are regulated in severe obesity and how weight loss after RYGB surgery affects HDL-miRNAs. Plasma HDLs were isolated from patients with severe obesity (n = 53) before and 6 and 12 months after RYGB by immunoprecipitation using goat anti-human apoA-I microbeads. HDLs were also isolated from 18 healthy participants. miRNAs were extracted from isolated HDL and levels of miR-24, miR-126, miR-222, and miR-223 were determined by TaqMan miRNA assays. We found that HDL-associated miR-126, miR-222, and miR-223 levels, but not miR-24 levels, were significantly higher in patients with severe obesity when compared with healthy controls. There were significant increases in HDL-associated miR-24, miR-222, and miR-223 at 12 months after RYGB. Additionally, cholesterol efflux capacity and paraoxonase activity were increased and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) levels decreased. The increases in HDL-associated miR-24 and miR-223 were positively correlated with an increase in cholesterol efflux capacity (r = 0.326, P = 0.027 and r = 0.349, P = 0.017, respectively). An inverse correlation was observed between HDL-associated miR-223 and ICAM-1 at baseline. Together, these findings show that HDL-associated miRNAs are differentially regulated in healthy participants versus patients with severe obesity and are altered after RYGB. These findings provide insights into how miRNAs are regulated in obesity before and after weight reduction and may lead to the development of novel treatment strategies for obesity and related metabolic disorders.

Supplementary key words: micro-ribonucleic acid, high-density lipoprotein functionality, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, weight loss

Abbreviations: DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; HOMA-B, homeostatic model assessment for beta cell function; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; miRNA, microRNA; PON1, paraoxonase-1; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SBP, systolic blood pressure

The global prevalence of obesity has doubled over the last three to four decades and continues to rise progressively (1, 2). Bariatric surgery results in durable reduction in weight and sustained improvement in metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes, both in a weight-dependent and weight-independent manner (3, 4). The precise molecular mechanisms driving the metabolic effects of bariatric surgery remain to be fully established.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding RNAs that negatively regulate mRNAs through target transcript degradation or by inhibiting translation (5). miRNAs are involved in a diverse range of biological pathways and have been implicated in the biological processes underlying obesity and the associated cardiometabolic disease (5, 6, 7, 8, 9). Altered miRNA expression, including increased miR-24 (10) and decreased miR-126 in adipose tissue (11), and increased miR-222 (7) and decreased miR-223 (12) in the circulation, have all been described previously in obesity. miRNAs act at the intracellular level and are transported between cells in association with lipid-based vesicles, lipoproteins, and lipid-free protein complexes (13). We and others have recently demonstrated the involvement of HDLs in the transport of functional miRNAs within an intercellular communication network, with delivery of a specific miRNA (miR-223) to endothelial cells, contributing to the anti-inflammatory capacity of HDLs (13, 14, 15).

HDL-C levels have been shown to correlate inversely with cardiovascular disease risk (16), and a clear link exists between excess weight and adiposity in obesity and low HDL-C levels (17). Improvements in HDL structure and function have been reported following metabolic surgery (18), although evidence for its effect on cholesterol efflux capacity has been inconsistent so far (19, 20, 21). Bariatric surgery has been shown to impact on the circulating miRNA signature of obesity (7), and significant changes have been described even prior to significant weight loss (22). The effect of bariatric surgery on HDL-associated miRNAs has not been investigated and may contribute mechanistically to improved HDL function following bariatric surgery. In this study, we assessed the changes in HDL-associated miR-24, miR-126, miR-222, and miR-223 levels following bariatric surgery.

Materials and methods

Participants

We recruited 53 patients with severe obesity (BMI 45.6–57.5 kg/m2 and weight circumference 142 ± 17 cm) who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery at the Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust tertiary weight management center (Salford, UK). Patients with acute coronary syndrome within the past 6 months, history of malignancy, anemia, active infections, HIV, and autoimmune diseases were excluded. Assessments were undertaken at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months after surgery. Eighteen healthy participants without a history of type 2 diabetes or statin therapy were recruited for comparison. This study was approved by the Greater Manchester Central Research and Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to participation and study assessments were conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

Laboratory analyses

Venous blood samples were obtained from patients between 0900 and 1100 following an overnight fast of at least 12 h. Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was measured using standard laboratory methods in the Department of Biochemistry, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (Manchester, UK) on the day of collection. Isolated serum and plasma samples were stored at −80°C until use. Other laboratory measurements were performed at the end of the study.

Total cholesterol and triglyceride were measured using CHOP-PAP and GPO-PAP methods, respectively. ApoA-I and apoB were measured using immunoturbidimetry. HDL-C was assayed using a second-generation homogenous direct method (23). Serum paraoxonase (PON1) activity was measured using paraoxon [O,O-diethyl O-(4-nitrophenyl) phosphate] as a substrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (24). All these tests were performed on a Randox Daytona+ analyzer (Randox Laboratories, Crumlin, UK). The laboratory participated in the RIQAS (Randox International Quality Assessment Scheme; Randox Laboratories, Dublin, Ireland). LDL-C was estimated using the Friedewald formula. No patients had triglyceride levels above 4.5 mmol/l.

Adiponectin, leptin, resistin, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) were measured using DuoSet ELISA development kits (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK), and insulin and glucose were measured using Mercodia ELISA kits (Diagenics Ltd., Milton Keynes, UK). The homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was used for the assessment of insulin resistance (25).

Cholesterol efflux capacity of HDL was determined using a previously validated method (26, 27, 28). The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 3.9% and 7.3%, respectively. Briefly, J774A.1 cells were incubated with 0.2 μCi of radiolabeled 3H-cholesterol in RPMI 1640 medium with 0.2% BSA at 37°C in a 5% carbon dioxide humidified atmosphere. ABCA1 expression was upregulated using 0.3 mM C-AMP [8-(4-chlorophenylthio) adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate sodium salt] for 4 h and the cells incubated with 2.8% (v/v) apoB-depleted serum using polyethylene glycol (PEG MW8000) for 4 h. The cell medium was then collected, and the cells were dissolved in 0.5 ml 0.2 N NaOH to determine radioactivity. Cholesterol efflux was expressed as the percentage of radioactivity in the medium from the radioactivity in the cells and medium collectively:

HDL isolation

Isolation of HDL was performed by immunoprecipitation of serum (600 μl) as previously described (29). Serum was applied to a column containing goat anti-human apoA-I antibody covalently coupled to cyanogen bromide (CNBr)-activated Sepharose 4B (Academy Bio-Medical Co., Inc., Houston, TX). The column was then washed 10 times with TBS to remove proteins nonspecifically bound to the beads. HDL was then eluted using stripping buffer (0.1 M acetic acid) and immediately neutralized with 1 M Tris, pH 11 (final concentration, 0.11 M). An Amicon Ultra-15 centrifuge filter unit and an Amicon Ultra-0.5 ultracel-10 membrane were used for further concentration of the samples.

HDL-associated miRNA

HDL-miRNA levels were assessed using real-time PCR TaqMan miRNA assays as previously described (29). Total RNA was isolated from HDL using QIAzol miRNAeasy kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and total RNA was quantified by spectrophotometry. Total RNA was purified and reversed transcribed using the TaqMan miRNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) and 7.5 μl of the reverse transcription product was used for detecting specific miRNAs using TaqMan miRNA assay kits (Applied Biosystems). Values were normalized to both Caenorhabditis elegans (Cel) miR-39 (which was spiked into the samples after the QIAzol step) and HDL total protein concentration determined by BCA assay (Thermo Scientific). Results were expressed as 2−[Ct(miRNA)−Ct(Cel-miR-39)].

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Statistical significance was set at two-tailed P < 0.05. Data were examined for normality based on skewness and kurtosis, and Shapiro-Wilk’s W test before analysis. Non-normally distributed variables were normalized prior to analysis using nature logarithmic (ln) transformation. To evaluate the effect of time on clinical characteristics and HDL-associated miRNA levels, one-way univariate repeated measures ANOVA was performed with time (baseline before surgery, and 6 and 12 months after surgery) as the within subject factor. Participants with missing data were excluded from the analysis. As there were a substantial number of participants with missing clinical characteristics at 6 months after surgery, clinical characteristics at baseline were compared with those at 6 and 12 months after surgery using individual paired t-test. Multiple testing correction was performed by Bonferroni correction for the two time-points, in which the threshold of P value for significance was <0.025. As the miRNA levels were highly correlated with each other, multiple testing corrections for the four miRNAs was not performed. Correlations between different HDL-associated miRNAs as well as between changes in individual miRNAs and changes in other variables were performed using bivariate Spearman correlation coefficients.

Results

Study sample and HDL-associated miRNA levels at baseline before surgery

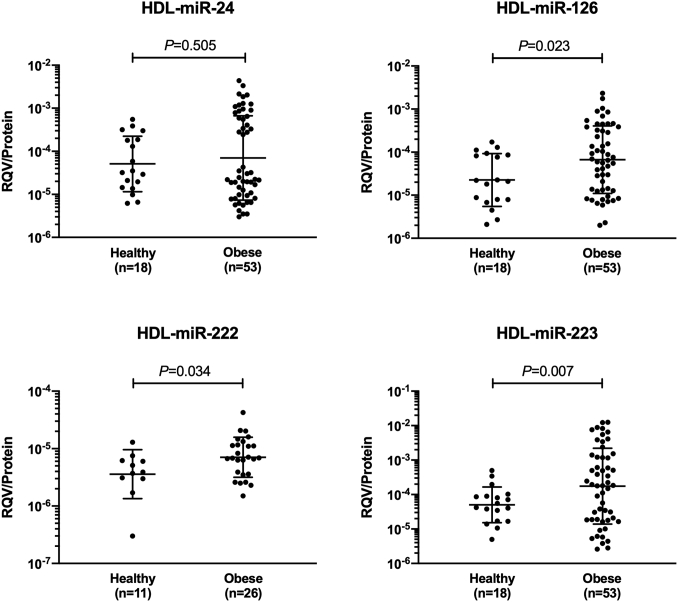

A total of 53 patients with severe obesity and a comparison group of 18 healthy participants were included in this study. The clinical characteristics for both groups are summarized in Table 1. Twenty-nine patients had type 2 diabetes and 26 were statin-treated, which remained unchanged following surgery. Blood samples were available for HDL-associated miRNA measurements at baseline and 12 months after surgery for all patients, and at 6 months after surgery for 42 patients. There was no significant difference in age, sex, and BMI between those with and without samples at 6 months after surgery (P = 0.104, 0.305, and 0.949, respectively). As shown in Fig. 1, HDL-associated miR-126, miR-222, and miR-223 levels, but not HDL-associated miR-24 levels, were significantly elevated in patients with severe obesity compared with healthy participants. The elevation of HDL-associated miR-126, miR-222, and miR-223 levels remained significant after adjusting for age and sex in multivariable linear regression analysis (P = 0.006, 0.034, and 0.037, respectively).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients who underwent surgery and healthy participants

| Characteristics | RYGB (n = 53) | Healthy (n = 18) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48.9 ± 8.7 | 43.3 ± 11.9 |

| Female (n, %) | 40, 75 | 14, 78 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 49.4 (45.8–57.4) | 22.0 (20.5–23.6) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 137.3 (128.5–150.5) | 81.0 (71.1–94.0) |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 131 (120–146) | 127 (115–140) |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 75.4 ± 13.8 | 73.0 ± 12.5 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 4.26 (3.79–5.28) | 5.26 (4.77–5.87) |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.46 (1.12–1.93) | 0.81 (0.70–1.41) |

| HDL-C (mmol/l) | 1.03 (0.87–1.32) | 1.66 (1.40–1.88) |

| LDL-C (mmol/l) | 2.44 (1.96–3.21) | 3.29 (2.61–3.60) |

| ApoA-I (g/l) | 1.26 (1.15–1.40) | 1.55 (1.39–1.84) |

| ApoB (g/l) | 0.80 (0.68–1.02) | 0.85 (0.77–0.95) |

Data are presented as mean ± SD and percent (n) or median (interquartile range). SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of different HDL-associated miRNA levels in healthy and obese subjects. Data shown are geometric mean and SD with log scale on the y axis. Data were compared using independent t-test after log transformation.

HDL-associated miR-24, miR-126, and miR-223 levels correlated positively with total cholesterol, HDL-C, LDL-C, and apoB levels (r = 0.318 to 0.549, all P < 0.05, Table 2). Positive correlations were also observed with cholesterol efflux capacity (miR-24, miR-126, and miR-223; r = 0.307–0.449; all P < 0.05) and PON1 activity (miR-24 and miR-126; r = 0.340 and 0.427, respectively, both P < 0.05, Table 2). Both HDL-associated miR-126 and miR-223 correlated inversely with ICAM-1 (r = −0.382 and −0.281, respectively, both P < 0.05, Table 2). HDL-associated miR-126, miR-222, and miR-223 levels inversely correlated with diastolic blood pressure (r = −0.272 to −0.467, all P < 0.05, Table 2) and HDL-associated miR-223 inversely correlated with resistin (r = −0.275, P = 0.048, Table 2).

Table 2.

Spearman correlation between different HDL-associated miRNAs and clinical characteristics at baseline before surgery

| Characteristics | miR-24 | miR-126 | miR-222 | miR-223 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | −0.012 | −0.127 | −0.232 | 0.005 |

| Height (m) | −0.019 | −0.258 | −0.074 | −0.042 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.164 | −0.122 | −0.038 | −0.241 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | −0.259 | −0.108 | 0.030 | −0.256 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | −0.115 | −0.118 | −0.124 | −0.099 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | −0.222 | -0.272a | -0.467a | -0.320a |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 0.426b | 0.549c | 0.220 | 0.461c |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 0.156 | 0.071 | 0.157 | 0.060 |

| HDL-C (mmol/l) | 0.373b | 0.459c | −0.252 | 0.495c |

| LDL-C (mmol/l) | 0.318a | 0.462c | 0.288 | 0.350a |

| ApoA-I (g/l) | 0.127 | 0.142 | −0.218 | 0.235 |

| ApoB (g/l) | 0.372b | 0.498c | 0.077 | 0.397b |

| Cholesterol efflux capacity (%) | 0.352a | 0.449b | 0.202 | 0.307a |

| PON1 activity (nmol/ml/min) | 0.340a | 0.427b | −0.069 | 0.242 |

| HbA1c (mmol/l) | −0.021 | −0.079 | −0.238 | −0.085 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) | 0.025 | 0.056 | −0.213 | 0.113 |

| Fasting insulin (mU/l) | 0.087 | 0.142 | −0.201 | 0.070 |

| HOMA-IR, ratio | 0.061 | 0.121 | −0.336 | 0.094 |

| HOMA-B, % | 0.091 | 0.072 | −0.043 | −0.023 |

| ICAM-1 (ng/ml) | −0.111 | -0.382a | −0.127 | -0.281a |

| Adiponectin (mg/l) | 0.200 | 0.095 | 0.034 | 0.155 |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 0.110 | 0.055 | −0.021 | 0.002 |

| Resistin (ng/ml) | −0.041 | −0.090 | 0.388 | -0.275a |

SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

Change in clinical characteristics after surgery

Table 3 shows the clinical characteristics of patients with severe obesity at baseline and 6 and 12 months after RYGB. As expected, median BMI decreased significantly from 49.4 kg/m2 at baseline to 37.3 kg/m2 at 6 months and 35.0 kg/m2 at 12 months after surgery, which was accompanied by similar reductions in waist circumference. There were significant improvements in cardiovascular risk profile, which included significant decreases in blood pressure, triglycerides, apoB, HbA1c, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and HOMA-IR, and an increase in HDL-C at 12 months after surgery. There was also a significant increase in cholesterol efflux capacity, PON1 activity, and adiponectin levels, and significant decreases in ICAM-1, leptin, and resistin levels 12 months after surgery. Some of the changes in clinical characteristics (systolic blood pressure, triglycerides, HbA1c, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and HOMA-IR) and biomarker levels (cholesterol efflux capacity, ICAM-1, adiponectin, and leptin) were statistically significant at 6 months after surgery.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics before surgery and 6 and 12 months after surgery

| Characteristics | Before Surgery (n = 53) |

6 Months After Surgery (n = 42) |

12 Months After Surgery (n = 53) |

Overall Pb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Estimate | n | Estimate | Pa | n | Estimate | Pa | ||

| BMI (kg/m2)c | 53 | 49.4 (45.6–57.5) | 43 | 37.3 (33.4–44.0) | <0.001 | 53 | 35.0 (30.3–38.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 53 | 142 ± 17 | 35 | 118 ± 16 | <0.001 | 53 | 106 ± 14 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| SBP (mm Hg)c | 53 | 131 (120–146) | 38 | 126 (109–137) | 0.006 | 52 | 119 (110–132) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 53 | 75.4 ± 13.8 | 38 | 71.2 ± 14.8 | 0.132 | 52 | 69.6 ± 10.5 | 0.002 | 0.041 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l)c | 53 | 4.26 (3.79–5.28) | 42 | 4.41 (3.55–5.49) | 0.520 | 53 | 4.43 (3.73–5.14) | 0.943 | 0.720 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l)c | 53 | 1.46 (1.12–1.93) | 41 | 1.29 (1.01–1.60) | 0.025 | 53 | 1.08 (0.84–1.41) | 0.005 | 0.014 |

| HDL-C/l)c | 53 | 1.03 (0.87–1.32) | 42 | 1.17 (0.96–1.44) | 0.070 | 53 | 1.29 (1.04–1.43) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| LDL-Cl/l)c | 52 | 2.44 (1.96–3.21) | 41 | 2.56 (1.82–3.57) | 0.817 | 53 | 2.43 (1.97–3.20) | 0.547 | 0.468 |

| ApoA-I (g/l)c | 52 | 1.26 (1.15–1.40) | 43 | 1.20 (1.10–1.42) | 0.093 | 52 | 1.23 (1.11–1.38) | 0.391 | 0.243 |

| ApoB (g/l)c | 53 | 0.80 (0.68–1.02) | 43 | 0.77 (0.63–0.99) | 0.139 | 53 | 0.73 (0.61–0.86) | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Cholesterol efflux capacity (%) | 53 | 12.94 ± 3.79 | 43 | 14.28 ± 3.95 | 0.025 | 53 | 16.03 ± 4.38 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PON1 activity (nmol/ml/min) | 53 | 67.0 (36.7–172.6) | 43 | 69.7 (43.0–162.8) | 0.683 | 53 | 83.0 (46.8–162.0) | 0.009 | 0.007 |

| HbA1c (mmol/l)c | 51 | 45.4 (41.0–53.0) | 44 | 38.4 (33.5–41.0) | <0.001 | 52 | 35.0 (32.3–37.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l)c | 52 | 5.99 (5.13–6.78) | 43 | 5.54 (4.68–6.19) | 0.006 | 53 | 5.00 (4.66–5.82) | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Fasting insulin (mU/l)c | 52 | 18.44 (13.41–32.58) | 42 | 9.46 (6.54–17.53) | <0.001 | 53 | 6.91 (4.75–12.29) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HOMA-IR, ratioc | 52 | 5.71 (3.35–8.61) | 42 | 2.66 (1.65–4.30) | <0.001 | 53 | 1.54 (1.06–2.94) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HOMA-B, %c | 51 | 153 (64–258) | 42 | 107 (72–168) | 0.047 | 53 | 103 (69–159) | 0.032 | 0.006 |

| ICAM-1 (ng/ml) | 53 | 199.0 (154.7–234.2) | 42 | 163.7 (132.9–190.3) | 0.009 | 53 | 136.8 (124.5–157.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Adiponectin (mg/l) | 52 | 3.28 ± 1.46 | 42 | 4.39 ± 1.83 | <0.001 | 53 | 5.97 ± 2.67 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Leptin (ng/ml)c | 52 | 70.3 (48.8–98.4) | 42 | 25.8 (13.9–44.5) | <0.001 | 53 | 17.0 (8.5–36.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Resistin (ng/ml) | 52 | 15.1 (10.8–17.6) | 42 | 12.6 (9.3–16.2) | 0.099 | 53 | 9.4 (6.3–13.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean ±± SD and percent (n) or median (interquartile range). SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

Data were compared with those at baseline using paired t-test.

Ps for change over time from baseline to 12 months after surgery (repeated measures ANOVA).

Ps were estimated using ln-transformed data.

Change in HDL-associated miRNA levels after surgery

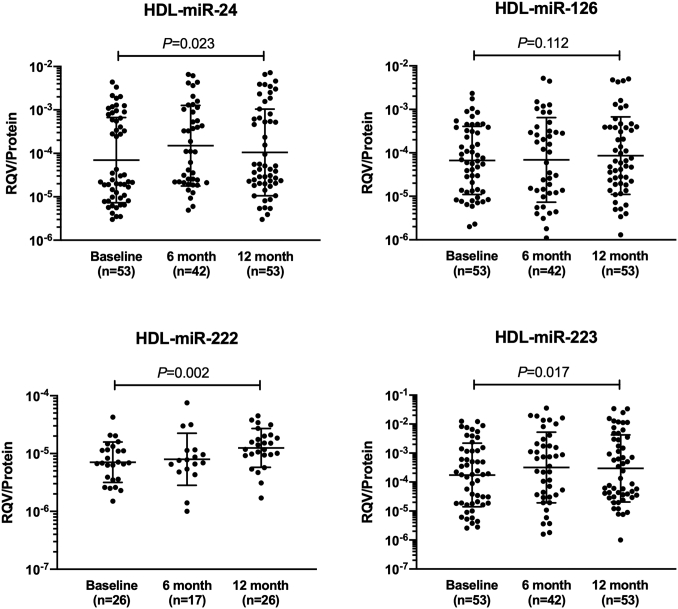

Table 4 shows the median and interquartile ranges of different HDL-associated miRNAs at baseline and 6 and 12 months after surgery, while Fig. 2 shows the corresponding geometric mean and standard deviation of these HDL-associated miRNAs.

Table 4.

Comparison of HDL-associated miR-223, miR-24, miR-126, and miR-222 levels at baseline before surgery and 6 and 12 months after surgery

| HDL-Associated miRNAs | Before Surgery (n = 53) |

6 Months After Surgery (n = 42) |

12 Months After Surgery (n = 53) |

Overall Pb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | RQV/Protein (×10−5) | n | RQV/Protein (×10−5) | Pa | n | RQV/Protein (×10−5) | Pa | ||

| miR-24 | 53 | 2.5 (1.0–71.8) | 42 | 11.1 (2.2–106.1) | 0.033 | 53 | 4.3 (2.0–73.3) | 0.004 | 0.023 |

| miR-126 | 53 | 6.5 (1.3–35.4) | 42 | 8.2 (1.2–33.7) | 0.943 | 53 | 6.5 (1.9–3.9) | 0.062 | 0.112 |

| miR-222 | 26 | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 17 | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.016 | 26 | 1.3 (0.9–2.0) | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| miR-223 | 53 | 18.4 (1.9–131.1) | 42 | 50.0 (3.5–232.6) | 0.071 | 53 | 24.4 (3.6–325.8) | 0.002 | 0.017 |

Data are presented median (interquartile range) in the unit of RQV/protein and were ln-transformed before analysis.

Ps for change over time from baseline to 12 months after surgery (repeated measures ANOVA).

Data were compared with those at baseline using paired t-test.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of different HDL-associated miRNA levels in obese subjects at baseline before surgery and 6 and 12 months after surgery. Data shown are geometric mean and SD with log scale on the y axis. Data were compared using one-way univariate repeated measures ANOVA and participants with missing data at any time-points were excluded from the analysis.

There were significant increases in HDL-associated miR-24, miR-222, and miR-223 levels, but not the miR-126 level, at 12 months after surgery, in which the increase in HDL-associated miR-222 levels remained statistically significant at 6 months after correcting for multiple testing of two time-points (Table 4, Fig. 2). Although HDL-associated miR-24 showed a significant increase at 6 months, the increase was not statistically significant after correcting for multiple testing. For all these HDL-associated miRNAs, the change over time did not differ between groups divided based on gender, presence of type 2 diabetes, or statin therapy (all P for time interaction >0.05).

All HDL-associated miRNAs showed strong positive correlation with each other at baseline (r = 0.461–0.878, all P < 0.05). Similar results were found at 6 and 12 months after surgery, although the correlation of HDL-associated miR-222 with miR-126 and miR-223 was attenuated to nonsignificance at 12 months after surgery (Table 5).

Table 5.

Cross-sectional bivariate Spearman correlation among different HDL-associated miRNAs at baseline and 6 and 12 months after surgery

| HDL-Associated miRNA | miR-24 | miR-126 | miR-222 | miR-223 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before surgery | ||||

| miR-24 | — | |||

| miR-126 | 0.824a | — | ||

| miR-222 | 0.610a | 0.837a | — | |

| miR-223 | 0.762a | 0.878a | 0.461b | — |

| 6 months | ||||

| miR-24 | — | |||

| miR-126 | 0.875a | — | ||

| miR-222 | 0.709c | 0.387 | — | |

| miR-223 | 0.824a | 0.859a | 0.700c | — |

| 12 months | ||||

| miR-24 | — | |||

| miR-126 | 0.800a | — | ||

| miR-222 | 0.646a | 0.354 | — | |

| miR-223 | 0.810a | 0.817a | 0.363 | — |

P < 0.001.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

Among the HDL-associated miRNA levels that showed significant increase at 12 months after surgery, increase in HDL-associated miR-24 levels correlated strongly and positively with increase in HDL-associated miR-222 and miR-223 levels (r = 0.732 and 0.577, respectively, both P < 0.05). There was, however, no significant correlation between the changes in HDL-associated miR-222 and miR-223 levels (Table 6).

Table 6.

Bivariate Spearman correlation among changes in HDL-associated miR-24, miR-222 and miR-223 at 12 months after surgery

| HDL-Associated miRNA | miR-24 | miR-222 | miR-223 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | |||

| miR-24 | — | ||

| miR-222 | 0.732a | — | |

| miR-223 | 0.577a | 0.354 | — |

| 12 months | |||

| miR-24 | — | ||

| miR-222 | 0.744a | — | |

| miR-223 | 0.757a | 0.342 | — |

P < 0.001.

Correlation of changes in HDL-associated miRNA levels with changes in clinical characteristics

Although none of the HDL-associated miRNA levels correlated with BMI at baseline, changes in HDL-associated miR-24 levels at 12 months after surgery correlated positively with changes in BMI (r = 0.309, P = 0.024, Table 7). In fact, a significantly larger reduction in weight was observed in patients with sub-median change in HDL-associated miR-24 levels at 12 months after surgery (Table 8). A larger weight reduction was also observed among patients with decreased miR-24 (n = 17) compared with patients with increased miR-24 (n = 36) at 12 months after RYGB (−17.9 ± 5.7 kg/m2 vs. −15.9 ± 5.8 kg/m2, P = 0.248) although statistical significance was not achieved. Weight reduction did not differ between groups divided using median baseline HDL-associated miRNA levels (Table 8).

Table 7.

Spearman correlation between absolute changes in HDL-associated miRNAs and absolute changes in clinical characteristics at 12 months after surgery

| Characteristics | ΔmiR-24 | ΔmiR-222 | ΔmiR-223 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔBMI (kg/m2) | 0.309a | 0.238 | 0.259 |

| ΔWaist circumference (cm) | 0.175 | 0.146 | 0.206 |

| ΔSBP (mm Hg) | 0.285a | 0.232 | 0.089 |

| ΔDBP (mm Hg) | 0.223 | −0.030 | 0.153 |

| ΔTotal cholesterol (mmol/l) | 0.034 | 0.142 | −0.126 |

| ΔTriglycerides (mmol/l) | 0.331a | −0.069 | 0.112 |

| ΔHDL-C (mmol/l) | −0.230 | −0.025 | −0.117 |

| ΔLDL-C (mmol/l) | −0.023 | 0.244 | −0.115 |

| ΔApoA-I (g/l) | 0.003 | 0.077 | 0.060 |

| ΔApoB (g/l) | 0.085 | −0.111 | −0.060 |

| ΔCholesterol efflux capacity (%) | 0.326a | 0.453 | 0.349a |

| ΔPON1 activity (nmol/ml/min) | 0.248 | 0.333 | 0.242 |

| ΔHbA1c (mmol/l) | 0.230 | −0.123 | 0.187 |

| ΔFasting glucose (mmol/l) | 0.023 | −0.215 | 0.048 |

| ΔFasting insulin (mU/l) | −0.089 | 0.022 | −0.057 |

| ΔHOMA-IR, ratio | −0.060 | −0.025 | −0.044 |

| ΔHOMA-B, % | −0.179 | 0.433a | −0.185 |

| ΔICAM-1 (ng/ml) | −0.147 | 0.109 | −0.265 |

| ΔAdiponectin (mg/l) | -0.336a | −0.245 | −0.246 |

| ΔLeptin (ng/ml) | 0.033 | 0.099 | −0.089 |

| ΔResistin (ng/ml) | 0.082 | 0073 | 0.029 |

P < 0.05.

Table 8.

Reduction in BMI according to HDL-associated miRNAs at baseline before surgery and their changes from baseline to 12 months after surgery

| Subgroups | Reduction in BMI (kg/m2) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Before surgery | ||

| miR-24 | ||

| <Median (n = 26) | 15.2 (12.4–20.1) | 0.803 |

| ≥Median (n = 27) | 15.7 (13.2–19.7) | |

| miR-222 | ||

| <Median (n = 26) | 14.1 (11.6–19.6) | 0.300 |

| ≥Median (n = 27) | 18.3 (13.1–20.2) | |

| miR-223 | ||

| <Median (n = 26) | 15.7 (12.8–20.5) | 0.669 |

| ≥Median (n = 27) | 15.5 (13.0–19.5) | |

| Change at 12 months | ||

| ΔmiR-24 | ||

| <Median (n = 26) | 18.2 (14.0–20.7) | 0.015 |

| ≥Median (n = 27) | 14.0 (10.9–17.9) | |

| ΔmiR-222 | ||

| <Median (n = 26) | 16.1 (13.3–19.3) | 0.762 |

| ≥Median (n = 27) | 13.4 (11.4–20.8) | |

| ΔmiR-223 | ||

| <Median (n = 26) | 15.7 (13.3–20.1) | 0.355 |

| ≥Median (n = 27) | 14.5 (11.8–19.0) |

Data are presented median (interquartile range). P was estimated using Mann-Whitney U test.

There were significant positive correlations between changes in HDL-associated miR-24 and miR-223 levels with cholesterol efflux capacity (r = 0.326, P = 0.027 and r = 0.349, P = 0.017, respectively, Table 7). The correlation between HDL-associated miR-222 and cholesterol efflux capacity did not achieve statistical significance (r = 0.453, P = 0.052, Table 7). There were also trends for positive correlations between HDL-associated miR-24, miR-222, and miR-223 with PON1 activity, which did not achieve statistical significance (r = 0.248, P = 0.074; r = 0.333, P = 0.097 and r = 0.242, P = 0.081, respectively). Similarly, a trend for negative correlation was observed between changes in ICAM-1 and changes in HDL-associated miR-223 (r = −0.265, P = 0.055) but not the other miRNAs.

Furthermore, HDL-associated miR-24 levels positively correlated with changes in triglyceride levels, and inversely with changes in adiponectin (r = 0.331, P = 0.015 and r = −0.336, P = 0.015, Table 7), while changes in HDL-associated miR-222 positively correlated with changes in homeostatic model assessment for beta cell function (HOMA-B) (r = 0.433, P = 0.035, Table 7).

Discussion

This is the first study to assess the changes in HDL-associated miRNAs following RYGB in patients with severe obesity. Here, we demonstrate an alteration in miRNA signature in patients with severe obesity following bariatric surgery in tandem with the expected reduction in BMI and improvements in metabolic and glycemic markers.

Following RYGB, there were significant increases in HDL-associated miR-24, miR-222, and miR-223, with positive correlations between miRNAs at baseline maintained at 12 months after surgery. The increase in HDL-associated miRNAs appears to indicate an overall increase in HDL function following surgery and this is supported by the positive correlations and trends observed with improvements in markers of HDL functionality such as cholesterol efflux capacity and PON1 activity. Both miR-222 and miR-223 are modulators of key components within the pathophysiology of cardiometabolic disease in obesity, and increases in these HDL-associated miRNAs could reflect enhancement of HDL’s cardioprotective functions and explain at least some of the metabolic improvements that are observed following RYGB.

Multiple studies have suggested a role for miR-222 within the pathophysiological process underlying obesity and cardiometabolic disease. miR-222 is closely related to glucose metabolism and is thought to negatively regulate adipose tissue insulin sensitivity (5) with increased expression of miR-222 in circulation being described in obesity (7, 30), and within the adipose tissue of patients with diabetes and insulin resistance (5). Higher levels of HDL-associated miR-222 have also been previously reported in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (14). In our study, we found a positive correlation between changes in HDL-miR-222 and HOMA-B, suggesting that it may have a role in improving glycemia after bariatric surgery. The higher levels of HDL-miR-222 in obesity and diabetes shown in previous studies may reflect a compensatory rise in response to the underlying metabolic derangement rather than the cause. This hypothesis is consistent with miR-222 being shown to improve hyperglycemia through proliferation of pancreatic β cells in a previous study using murine models (31). It is, however, important to point out that assessment of β cell function using static measures of insulin and glucose is suboptimal and is influenced by factors such as insulin action, alterations in energy balance, and marker alterations in glucose and insulin before and after surgery (32). Indeed, a reduction in HOMA-B was observed in our cohort despite improvements in all markers of glycemia and, therefore, require further study with dynamic testing. Also, interestingly, in contrast with our findings, a previous study of patients who underwent RYGB found a significant postsurgical reduction of circulating plasma miR-222 (7). One potential explanation for these discrepant results may be that, despite a reduction in overall circulating miR-222, the amount transported by HDL is increased due to the enhanced uptake capacity. Further studies will be required to further assess this.

miR-223 has an important role in the development and regulation of the immune system and is established as a potent regulator of inflammatory processes (33). It has been previously associated with obesity with increased levels of visceral adipose tissue miR-223 being demonstrated (34). Increased adipose tissue inflammation and marked systemic insulin resistance have been shown in miR-223 knockout mice on a high-fat diet (35). Furthermore, the transfer of miR-223 from HDL has been shown to decrease ICAM-1 expression in endothelial cells (15). Indeed, a negative correlation between HDL-associated miR-223 and serum ICAM-1 levels at baseline and a negative trend between postsurgical changes were observed following RYGB. This provides support for enhanced HDL anti-inflammatory function following surgery, conferred in part through the transfer of miR-223. Furthermore, we have also demonstrated a positive correlation between HDL-associated miR-223 and cholesterol efflux capacity and a trend with PON1 activity, contributing further to an overall picture of enhanced HDL function after RYGB.

Although miR-223 has previously been shown to predict the response to a nonsurgical weight loss intervention with an 800–880 kcal/day hypocaloric diet (36), miR-223 expression did not differ between patients who achieved supra- and sub-median reductions in BMI following RYGB. Furthermore, in contrast to our post-RYGB observation, a reduction in HDL-associated miR-223 had been demonstrated following high-protein diet-induced weight loss in patients with obesity (29). This observed difference in impact on circulating miRNA can be explained by the difference in magnitude of reduction in weight and, therefore, adiposity following the dietary weight loss study (37) and this study. This is supported by both subcutaneous and omental adipose tissue being established sites of altered miRNA expression, including miR-223, following weight loss intervention (38, 39). There is likely also a difference in the impact on HDL functionality, particularly its transporting capacity between dietary and surgical weight loss. While cholesterol efflux capacity is shown to be increased post-RYGB in our study, studies on dietary weight loss are limited with no significant increase in cholesterol efflux capacity being noted following hypocaloric diet in the absence of exercise training (40).

Elevated levels of miR-24 have been reported in abdominal adipose tissue of patients with obesity, and are positively correlated with percentage body fat (10). Somewhat contrastingly, it has also been demonstrated that miR-24 has a role in modulating the expression of von Willibrand factor, where its levels are increased in type 2 diabetes when miR-24 levels are reduced through application of anti-miR-24, implicating a potential role in the risk of thrombotic cardiovascular events (41). In the same study, miR-24 was also shown to be downregulated in endothelial cells in response to hyperglycemia. It is therefore possible that the postsurgical increase in HDL-associated miR-24 observed in our cohort may result from glycemic improvement as well as enhancement of HDL function, and may contribute to a reduction in cardiovascular risk following RYGB. Interestingly, although both HDL-associated miR-24 and adiponectin levels increased after RYGB, a negative correlation was seen between the two. Similarly, despite contrasting post-RYGB changes, positive correlations were observed between changes in miR-24 and changes in BMI, triglyceride levels, and systolic blood pressure. In keeping with this, a significantly larger reduction in BMI was also observed in patients with decreased or smaller increase in miR-24 at 12 months. This may reflect the complex pathophysiological changes following RYGB, with differing relationships between miR-24 and changes in weight, adiposity, and glycemia.

Despite increases after RYGB, both HDL-associated miR-222 and miR-223 were higher at baseline compared with healthy participants, with similar observations also noted with HDL-associated miR-126. Although the lower miRNA expression in healthy participants may seem unexpected given the postsurgical upregulation, there are two potential explanations for this observation. First, the higher miR-126 (7), miR-222 (30), and miR-223 (34) expressions in obesity are in keeping with previous studies, and we postulate that this is likely triggered by underlying metabolic derangement, which would be in line with the effect of miR-222 on glycemia (31) and miR-223 on ICAM-1 (15) shown in previous studies. The increase in HDL-associated miRNA after surgery is in keeping with the improvement in HDL function, which may represent a dynamic process that drives metabolic improvements. It would be of great interest to see whether this upregulation of HDL-associated miRNA then reverts to the levels observed in healthy participants once the process of metabolic correction is completed. Second, statin therapy had been shown to upregulate both miR-222 and miR-223 expression (42), and a significant proportion of statin-use within our cohort with severe obesity is therefore likely to have contributed to the difference in miRNA expression.

Limitations to our study include the observational design and the small sample size, particularly within the control group. As only patients who underwent RYGB were included in our study, these findings may therefore not be extended to other weight loss procedures. Further studies with a larger study population including other metabolic surgical procedures would allow for comparison of surgical procedures and confirm the findings in our study.

In conclusion, severe obesity is associated with altered HDL-associated miRNAs, which is significantly changed following RYGB. The increase in expression of HDL-associated miRNAs following surgery may reflect an improvement in HDL function and may explain some of the cardiometabolic benefits observed following RYGB in severe obesity.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Study concept and design were by F. T. and H. S. J. H. H., S. A., Z. I., and S. D. undertook patient recruitment and clinical assessments. K. L. O., J. H. H., L. F. C. T., and Y. L. performed laboratory analyses. J. H. H. and K. L. O. performed the data analyses and undertook interpretation of findings with F. T. and H. S. J. H. H. produced the first draft and the final version with F. T. and H. S. S. A., Z. I., S. D., B. J. A., A. A. S., P. N. D., and K.-A. R. provided critical review for important intellectual content.

Author ORCIDs

Kerry-Anne Rye https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9751-917X

Handrean Soran https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1714-5014

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health Research/Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility (Manchester, UK) and the Lipid Disease Fund.

References

- 1.Finucane M.M., Stevens G.A., Cowan M.J., Danaei G., Lin J.K., Paciorek C.J., Singh G.M., Gutierrez H.R., Lu Y., Bahalim A.N. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet. 2011;377:557–567. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng M., Fleming T., Robinson M., Thomson B., Graetz N., Margono C., Mullany E.C., Biryukov S., Abbafati C., Abera S.F. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams T.D., Davidson L.E., Litwin S.E., Kim J., Kolotkin R.L., Nanjee M.N., Gutierrez J.M., Frogley S.J., Ibele A.R., Brinton E.A. Weight and metabolic outcomes 12 years after gastric bypass. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:1143–1155. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J. Intern. Med. 2013;273:219–234. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deiuliis J.A. MicroRNAs as regulators of metabolic disease: pathophysiologic significance and emerging role as biomarkers and therapeutics. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.). 2016;40:88–101. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schroen B., Heymans S. Small but smart–microRNAs in the centre of inflammatory processes during cardiovascular diseases, the metabolic syndrome, and ageing. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012;93:605–613. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortega F.J., Mercader J.M., Catalan V., Moreno-Navarrete J.M., Pueyo N., Sabater M., Gomez-Ambrosi J., Anglada R., Fernandez-Formoso J.A., Ricart W. Targeting the circulating microRNA signature of obesity. Clin. Chem. 2013;59:781–792. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.195776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hulsmans M., De Keyzer D., Holvoet P. MicroRNAs regulating oxidative stress and inflammation in relation to obesity and atherosclerosis. FASEB J. 2011;25:2515–2527. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-181149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vickers K.C., Remaley A.T. MicroRNAs in atherosclerosis and lipoprotein metabolism. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2010;17:150–155. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32833727a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nunez Lopez Y.O., Garufi G., Pasarica M., Seyhan A.A. Elevated and correlated expressions of miR-24, miR-30d, miR-146a, and SFRP-4 in human abdominal adipose tissue play a role in adiposity and insulin resistance. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2018;2018:7351902. doi: 10.1155/2018/7351902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arner E., Mejhert N., Kulyte A., Balwierz P.J., Pachkov M., Cormont M., Lorente-Cebrian S., Ehrlund A., Laurencikiene J., Heden P. Adipose tissue microRNAs as regulators of CCL2 production in human obesity. Diabetes. 2012;61:1986–1993. doi: 10.2337/db11-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen D., Qiao P., Wang L. Circulating microRNA-223 as a potential biomarker for obesity. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2015;9:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vickers K.C., Remaley A.T. Lipid-based carriers of microRNAs and intercellular communication. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2012;23:91–97. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328350a425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vickers K.C., Palmisano B.T., Shoucri B.M., Shamburek R.D., Remaley A.T. MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:423–433. doi: 10.1038/ncb2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabet F., Vickers K.C., Cuesta Torres L.F., Wiese C.B., Shoucri B.M., Lambert G., Catherinet C., Prado-Lourenco L., Levin M.G., Thacker S. HDL-transferred microRNA-223 regulates ICAM-1 expression in endothelial cells. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3292. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordon T., Castelli W.P., Hjortland M.C., Kannel W.B., Dawber T.R. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Am. J. Med. 1977;62:707–714. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rashid S., Genest J. Effect of obesity on high-density lipoprotein metabolism. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2875–2888. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zvintzou E., Skroubis G., Chroni A., Petropoulou P.I., Gkolfinopoulou C., Sakellaropoulos G., Gantz D., Mihou I., Kalfarentzos F., Kypreos K.E. Effects of bariatric surgery on HDL structure and functionality: results from a prospective trial. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2014;8:408–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heffron S.P., Lin B.X., Parikh M., Scolaro B., Adelman S.J., Collins H.L., Berger J.S., Fisher E.A. Changes in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol efflux capacity after bariatric surgery are procedure dependent. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018;38:245–254. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.310102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aron-Wisnewsky J., Julia Z., Poitou C., Bouillot J.L., Basdevant A., Chapman M.J., Clement K., Guerin M. Effect of bariatric surgery-induced weight loss on SR-BI-, ABCG1-, and ABCA1-mediated cellular cholesterol efflux in obese women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;96:1151–1159. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kjellmo C.A., Karlsson H., Nestvold T.K., Ljunggren S., Cederbrant K., Marcusson-Stahl M., Mathisen M., Lappegard K.T., Hovland A. Bariatric surgery improves lipoprotein profile in morbidly obese patients by reducing LDL cholesterol, apoB, and SAA/PON1 ratio, increasing HDL cholesterol, but has no effect on cholesterol efflux capacity. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2018;12:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atkin S.L., Ramachandran V., Yousri N.A., Benurwar M., Simper S.C., McKinlay R., Adams T.D., Najafi-Shoushtari S.H., Hunt S.C. Changes in blood microRNA expression and early metabolic responsiveness 21 days following bariatric surgery. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2019;9:773. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charlton-Menys V., Liu Y., Moorhouse A., Durrington P.N. The robustness of the Roche 2nd generation homogenous HDL cholesterol (PEGME) method: assessment of the effect of serum sample storage for up to 8 years at -80 degrees C. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2007;382:142–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlton-Menys V., Liu Y., Durrington P.N. Semiautomated method for determination of serum paraoxonase activity using paraoxon as substrate. Clin. Chem. 2006;52:453–457. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.063412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthews D.R., Hosker J.P., Rudenski A.S., Naylor B.A., Treacher D.F., Turner R.C. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de la Llera-Moya M., Drazul-Schrader D., Asztalos B.F., Cuchel M., Rader D.J., Rothblat G.H. The ability to promote efflux via ABCA1 determines the capacity of serum specimens with similar high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to remove cholesterol from macrophages. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010;30:796–801. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.199158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khera A.V., Cuchel M., de la Llera-Moya M., Rodrigues A., Burke M.F., Jafri K., French B.C., Phillips J.A., Mucksavage M.L., Wilensky R.L. Cholesterol efflux capacity, high-density lipoprotein function, and atherosclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:127–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hafiane A., Genest J. HDL-mediated cellular cholesterol efflux assay method. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2015;45:659–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tabet F., Cuesta Torres L.F., Ong K.L., Shrestha S., Choteau S.A., Barter P.J., Clifton P., Rye K.A. High-density lipoprotein-associated miR-223 is altered after diet-induced weight loss in overweight and obese males. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ortega F.J., Mercader J.M., Moreno-Navarrete J.M., Rovira O., Guerra E., Esteve E., Xifra G., Martinez C., Ricart W., Rieusset J. Profiling of circulating microRNAs reveals common microRNAs linked to type 2 diabetes that change with insulin sensitization. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1375–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsukita S., Yamada T., Takahashi K., Munakata Y., Hosaka S., Takahashi H., Gao J., Shirai Y., Kodama S., Asai Y. MicroRNAs 106b and 222 improve hyperglycemia in a mouse model of insulin-deficient diabetes via pancreatic beta-cell proliferation. EBioMedicine. 2017;15:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bradley D., Magkos F., Klein S. Effects of bariatric surgery on glucose homeostasis and type 2 diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:897–912. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.07.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taïbi F., Metzinger-Le Meuth V., Massy Z.A., Metzinger L. miR-223: An inflammatory oncomiR enters the cardiovascular field. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1842:1001–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deiuliis J.A., Syed R., Duggineni D., Rutsky J., Rengasamy P., Zhang J., Huang K., Needleman B., Mikami D., Perry K. Visceral adipose microRNA 223 is upregulated in human and murine obesity and modulates the inflammatory phenotype of macrophages. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhuang G., Meng C., Guo X., Cheruku P.S., Shi L., Xu H., Li H., Wang G., Evans A.R., Safe S. A novel regulator of macrophage activation: miR-223 in obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation. Circulation. 2012;125:2892–2903. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.087817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milagro F.I., Miranda J., Portillo M.P., Fernandez-Quintela A., Campion J., Martinez J.A. High-throughput sequencing of microRNAs in peripheral blood mononuclear cells: identification of potential weight loss biomarkers. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wycherley T.P., Brinkworth G.D., Clifton P.M., Noakes M. Comparison of the effects of 52 weeks weight loss with either a high-protein or high-carbohydrate diet on body composition and cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight and obese males. Nutr. Diabetes. 2012;2:e40. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2012.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macartney-Coxson D., Danielson K., Clapham J., Benton M.C., Johnston A., Jones A., Shaw O., Hagan R.D., Hoffman E.P., Hayes M. MicroRNA profiling in adipose before and after weight loss highlights the role of miR-223-3p and the NLRP3 inflammasome. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:570–580. doi: 10.1002/oby.22722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kristensen M.M., Davidsen P.K., Vigelso A., Hansen C.N., Jensen L.J., Jessen N., Bruun J.M., Dela F., Helge J.W. miRNAs in human subcutaneous adipose tissue: effects of weight loss induced by hypocaloric diet and exercise. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017;25:572–580. doi: 10.1002/oby.21765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan A.A., Mundra P.A., Straznicky N.E., Nestel P.J., Wong G., Tan R., Huynh K., Ng T.W., Mellett N.A., Weir J.M. Weight loss and exercise alter the high-density lipoprotein lipidome and improve high-density lipoprotein functionality in metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018;38:438–447. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.310212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiang Y., Cheng J., Wang D., Hu X., Xie Y., Stitham J., Atteya G., Du J., Tang W.H., Lee S.H. Hyperglycemia repression of miR-24 coordinately upregulates endothelial cell expression and secretion of von Willebrand factor. Blood. 2015;125:3377–3387. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-620278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J., Chen H., Ren J., Song J., Zhang F., Zhang J., Lee C., Li S., Geng Q., Cao C. Effects of statin on circulating microRNAome and predicted function regulatory network in patients with unstable angina. BMC Med. Genomics. 2015;8:12. doi: 10.1186/s12920-015-0082-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.