Abstract

Objective:

To test the hypothesis that delayed brain development in fetuses with d-transposition of the great arteries (d-TGA) or hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) heightens their postnatal susceptibility to acquired white matter injury (WMI).

Methods:

This is a cohort study across three sites. Subjects underwent fetal (third trimester) and neonatal pre-operative MRI of the brain to measure total brain volume (TBV) as a measure of brain maturity and the presence of acquired WMI after birth. WMI was categorized as none-mild or moderate-severe based on validated grading criteria. Comparisons were made between the injury groups.

Results:

63 subjects were enrolled (d-TGA:37; HLHS:26). WMI was present in 32.4% (n=12) of d-TGA and 34.6% (n=8) of HLHS subjects. Overall TBV (taking into account fetal and neonatal scan) was significantly lower in those with postnatal moderate-severe WMI compared to none-mild WMI after adjusting for age at scan and site in d-TGA (Coeff: 14.8 mL, 95%CI: −28.8,−0.73, p= 0.04). The rate of change in TBV from fetal to postnatal life did not differ by injury group. In HLHS, no association was noted between overall TBV or change in TBV with postnatal WMI.

Conclusions:

Lower TBV beginning in late gestation is associated with increased risk of postnatal moderate-severe WMI in d-TGA but not HLHS. Rate of brain growth was not a risk factor for WMI. The underlying fetal and perinatal physiology has different implications for postnatal risk of WMI.

Keywords: Congenital heart disease, Brain development, Brain injury, Neurodevelopment

Introduction:

Brain injury in the form of white matter injury (WMI) and stroke is common in the full-term neonate with critical congenital heart disease (CHD) 1, such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) or d-transposition of the great arteries (d-TGA). Studies have shown that approximately one-third of newborns with critical CHD have evidence of WMI even before the neonatal operation2. Importantly, moderate to severe WMI in the newborn period is associated with impairments in motor outcomes in late infancy3. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in the fetus and neonate with CHD have revealed delays in global brain volumes, microstructure and metabolic brain development4,5.

The mechanism of postnatal WMI in the patient with CHD is thought to be related to brain immaturity similar to mechanisms observed in the premature population. In particular, hypoxic and ischemic events are thought to affect selectively vulnerable cell populations including pre-oligodendrocytes leading to white matter injury. Although replenishment occurs in this progenitor cell population, maturation is arrested in pre-oligodendrocytes resulting in impaired myelination6. The relationship between brain immaturity and WMI in the CHD population has been difficult to elucidate given the myriad of risk factors in the postnatal period that are associated with neurologic outcomes7–9.

In order to design effective preventative strategies in this patient population, understanding the causal pathway to acquired neonatal brain injury is crucial. In this study, we sought to determine the association between fetal and neonatal brain size and growth as a measure of maturational state with the risk of postnatal pre-operative WMI utilizing longitudinal MR imaging from fetal to postnatal life. We chose moderate to severe WMI as the primary outcome due to the clinically relevant association with impaired motor outcomes in infancy noted in prior studies3. We studied two well-characterized groups of patients (d-TGA & HLHS) to account for varying cardiac anatomy and physiology that can influence both our primary predictor and outcome of interest.

Methods:

Between 2010 and 2018, pregnant mothers with a fetal diagnosis of critical CHD at three sites (University of California San Francisco (UCSF), University of British Columbia (UBC) and University of Toronto Hospital for Sick Children (UT)) were invited consecutively to participate in a prospective protocol using MRI to study brain development and brain injury in CHD. Fetuses with a suspected congenital infection, clinical evidence of a congenital malformation or syndrome and/or a suspected or confirmed genetic or chromosomal anomaly were excluded. Once written informed consent was received, subjects underwent a fetal brain MRI in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy followed by a postnatal brain MRI of the neonate prior to cardiac surgery. The institutional committee on human research approved the study protocol at each site. Written informed consent was obtained from each pregnant mother and postnatal infant’s parents.

Subjects diagnosed as having d-TGA or HLHS with both a fetal and neonatal brain MRI were included in this study. 10 subjects (HLHS= 5; d-TGA= 5) had a fetal brain MRI but did not return for a neonatal brain MRI and were not included in the study. There were no significant differences between the subjects included in the study versus those that did not have repeat imaging after birth. D-TGA was defined as great vessel malposition with the aorta arising from the right ventricle and pulmonary artery arising from the left ventricle with or without a ventricular septal defect. HLHS was defined as the presence of one functioning right ventricle with varying degrees of severe left heart hypoplasia requiring a palliative surgical intervention for survival (Stage I operation) in the newborn period. In all subjects the cardiac diagnosis was confirmed with postnatal echocardiography.

MRI Study:

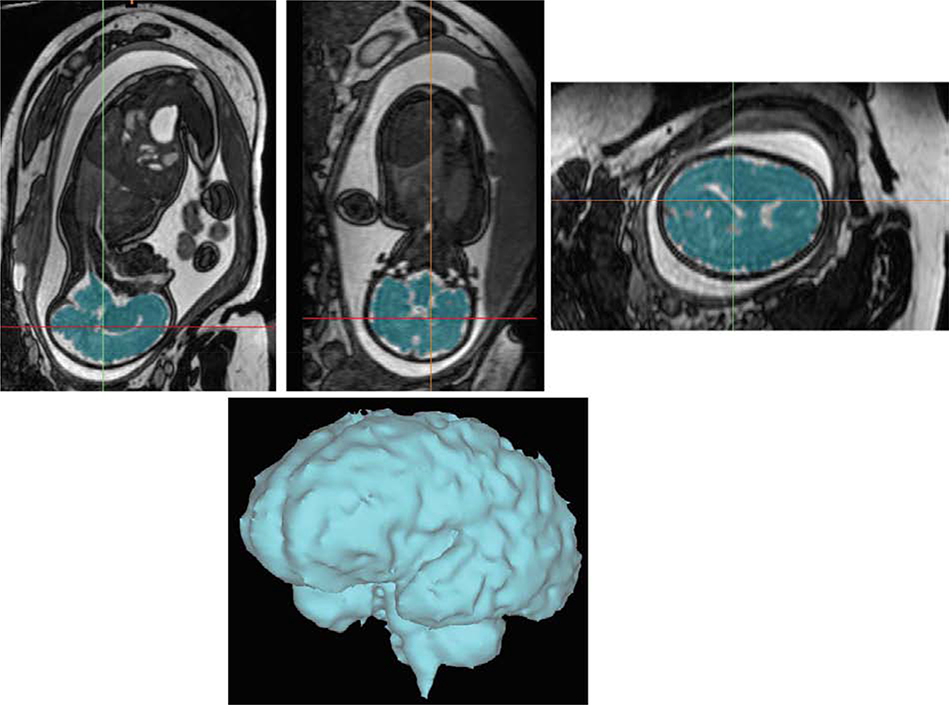

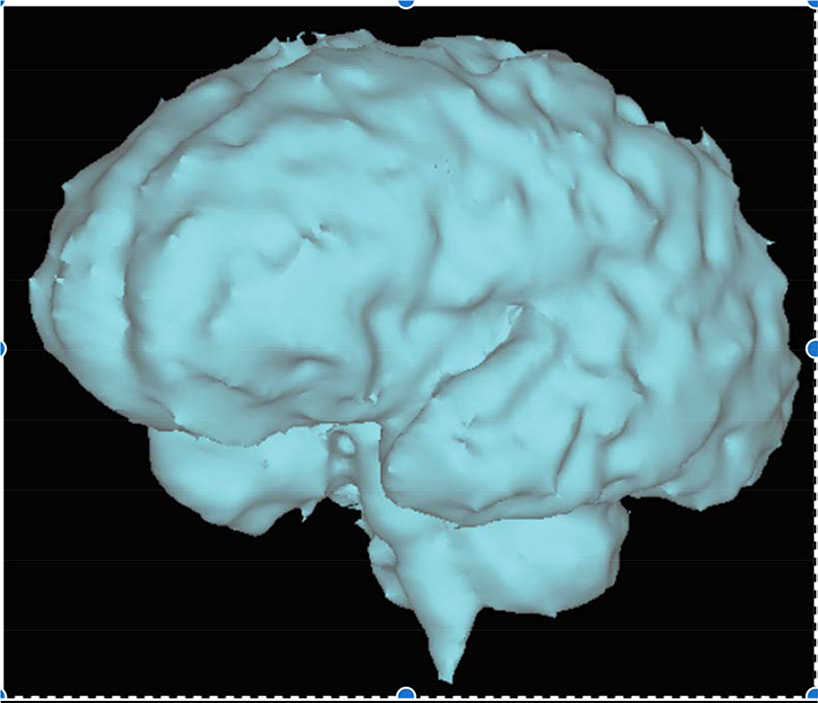

A fetal brain MRI was performed in the third trimester (median 35 weeks, IQR: 32.6–36). Similar imaging protocols were utilized at each site. The fetal scans were performed on either a 1.5-T (Siemens Avanto, Erlangen, Germany, UBC & UT) or 3-T (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA, UCSF) MRI system. A 3-dimensional steady-state free-precession acquisition (UT, UBC) or T2-weighted images (UCSF) were used to measure fetal brain volume. Imaging parameters used at each site are detailed in supplementary material. All scans were post-processed at one site (UT). Postprocessing of the acquisition to segment the fetal brain was performed by use of a combination of threshold, cutting, and filling tools with a commercial software package (Mimics, Materialize, Leuven) as previously described10 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Fetal brain volumetry in a fetus with congenital heart disease with segmentation of a 3-dimensional steady-state free-precession acquisition to measure total brain volume. Three orthogonal planes are depicted with the final volumetric image of the fetal brain.

Postnatal MRI studies prior to cardiac surgery were performed as soon as the baby could be safely transported to the MRI scanner as determined by the clinical team. Imaging parameters at each site are detailed in supplementary materials. Brain volume was measured on the postnatal scan as was done on the fetal scan above (post-processing of scans and measurement of brain volumes were performed at a single site). A neuroradiologist at each site reviewed each MRI for focal, multifocal or global changes blinded to clinical variables. For this study, brain injury in the form of white matter injury (WMI) was collected. WMI was further classified as mild (1 to 3 foci each < 2mm), moderate (>3 foci or any foci > 2mm), or severe (>5% of WM volume) 2. We have previously demonstrated high inter-rater reliability of the neuroradiology scores applied to grade the severity of brain injury11 as well as consistent findings when compared to quantitative measures of WMI3. Other forms of brain injury were also recorded including stroke, though all were small and not analyzed as part of the present study.

Clinical Variables:

Clinical data (including fetal, delivery and postnatal variables) were prospectively collected from the medical records by the study physicians and/or a team of trained neonatal research nurses and reviewed by investigators at each site blinded to all neuroimaging findings.

Statistical Analysis:

Our primary outcome was prospectively defined as the presence of moderate to severe WMI on the postnatal pre-operative MRI as defined above. Baseline demographics were compared between those with and without WMI within each cardiac group (d-TGA or HLHS). Our primary exposure was total brain volume (TBV) on the fetal and neonatal MRI. We identified a significant interaction with cardiac diagnostic group in the relationship between our primary predictor and outcome, thus the analysis was stratified by cardiac diagnosis (HLHS and d-TGA). To take into account two imaging time points and within-subject correlation, we conducted a repeated measures analysis using generalized estimating equations to assess the relationship between total brain volume at both the fetal and neonatal time points with the prevalence of moderate to severe WMI after birth. The final model included an adjustment for both time at MRI (postmenstrual age at scan) as well as site. All analyses were performed on Stata 14.0 software (StataCorp, College, Texas).

Results:

A total of 63 subjects were enrolled that had both fetal and neonatal brain MRIs (d-TGA= 37, HLHS= 26). Baseline demographics are presented in Table 1 by WMI severity. Gestational age at birth was on average 1 week earlier for those with moderate-severe WMI on the postnatal pre-operative MRI, though not statistically significant (GA birth: d-TGA: 38.8 weeks, 95% CI: 38.2–39.4 vs. 39.1 weeks, 95% CI: 38.7–39.5 wks, p= 0.5; HLHS: 38.1 weeks, 95% CI: 37.6–38.5 vs. 39.1 weeks, 95% CI: 38.5–39.9 wks, p= 0.07). No other clinical or demographic factors were different by WMI severity for either cardiac group. Anatomic details are included in Table 1. Among the d-TGA group, the percentage of patients with a VSD was similar in those with none/mild WMI compared to those with moderate-severe WMI. In addition, 4 subjects had an associated coarctation of the aorta, one of which had moderate-severe WMI. Among the HLHS group, a significantly higher percentage of patients had aortic atresia in the moderate/severe WMI group. The prevalence and severity of pre-operative neonatal brain injury is presented in Table 2. In the d-TGA group, 12 (32.4%) subjects had WMI, of whom 4 (10.8%) had moderate to severe WMI. In the HLHS group, 8 (34.6%) had WMI, of whom 5 (19.2%) had moderate to severe WMI. A small number of patients had evidence of stroke on the neonatal MRI (d-TGA: n= 3, 8.1%; HLHS: n= 2, 7.7%), all of which were small.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of study population by cardiac group and white matter injury severity (comparing those with none/mild white matter injury to those with moderate/severe white matter injury).

| d-TGA (n= 37) | p-value | HLHS (n= 26) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None/mild WMI (n= 33) | Mod/severe WMI (n= 4) | None/mild WMI (n= 21) | Mod/severe WMI (n= 5) | |||

| GA fetal scan Mean, 95% CI | 35.1 (34.4, 35.8) | 34.5 (31.7, 37.3) | 0.58 | 34.7 (33.7, 35.7) | 32.8 (30.1, 35.4) | 0.07 |

| Male | 20 (60.6%) | 4 (100%) | 0.28 | 17 (81%) | 3 (60%) | 0.25 |

| GA birth Mean, 95% CI | 39.1 (38.7, 39.5) | 38.8 (38.2, 39.4) | 0.5 | 39.1 (38.5, 39.7) | 38.1 (37.6, 38.5) | 0.07 |

| Birth weight, kg Mean, 95% CI | 3.4 (3.2, 3.5) | 3.3 (2.8, 3.9) | 0.86 | 3.2 (3.0, 3.5) | 3.0 (2.6, 3.3) | 0.34 |

| Birth HC, cm Mean, 95% CI | 34.2 (33.8–34.7) | 34 (31.7–36.2) | 0.72 | 34.1 (33.2–34.9) | 33.7 (33.1–34.2) | 0.65 |

| pH on first arterial blood gas Mean, 95% CI | 7.29 (7.26–7.33) | 7.29 (7.21–7.38) | 0.98 | 7.30 (7.25–7.35) | 7.33 (7.24–7.41) | 0.58 |

| Lowest pre-operative O2 saturation | 69.1 (61.6, 76.5) | 64.5 (34.5, 94.5) | 0.68 | 80.5 (73.0, 87.9) | 85.4 (80.1, 90.7) | 0.48 |

| Pre-op Cardiac Arrest, N(%) | 1 (3.0%) | 0 | 1.0 | 1 (4.8%) | 0 | 1.0 |

| BAS, N(%) | 26 (78.8%) | 2 (50%) | 0.28 | 3 (14.3%) | 0 | 1.0 |

| VSD, N(%) | 11 (33.3%) | 3 (75%) | 0.13 | |||

| Aortic Atresia, N(%) | 10 (47.6%) | 5 (100%) | 0.05 | |||

| Retrograde flow in aortic arch, N(%) | 14 (66.7%) | 5 (100%) | 0.29 | |||

| GA postnatal scan, Mean, 95% CI | 39.6 (39.2, 40.0) | 39.3 (38.4, 40.2) | 0.62 | 39.8 (39.3, 40.4) | 38.5 (37.9, 39.1) | 0.02 |

| Site | 0.42 | 0.46 | ||||

| UCSF | 4 (12.1%) | 1 (25%) | 10 (47.6%) | 4 (80%) | ||

| UBC | 6 (18.2%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 | ||

| Toronto | 23 (69.7%) | 2 (50%) | 10 (47.6%) | 1 (20%) | ||

D-TGA= d-transposition of the great arteries; HLHS= hypoplastic left heart syndrome; WMI= white matter injury; GA= gestational age; HC= head circumference; BAS= balloon atrial septostomy; VSD= ventricular septal defect; UCSF= University of California San Francisco; UBC= University of British Columbia

Table 2.

Prevalence and severity of pre-operative brain injury by cardiac group

| d-TGA (n= 37) | HLHS (n= 26) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total WMI, N (%) | 12 (32.4%) | 8 (34.6%) |

| Mild WMI | 8 (18.9%) | 3 (11.5%) |

| Mod-Sev WMI | 4 (10.8%) | 5 (19.2%) |

| Stroke, N (%) | 3 (8.1%) | 2 (7.7%) |

d- TGA= d-transposition of the great arteries; HLHS= hypoplastic left heart syndrome; WMI= white matter injury

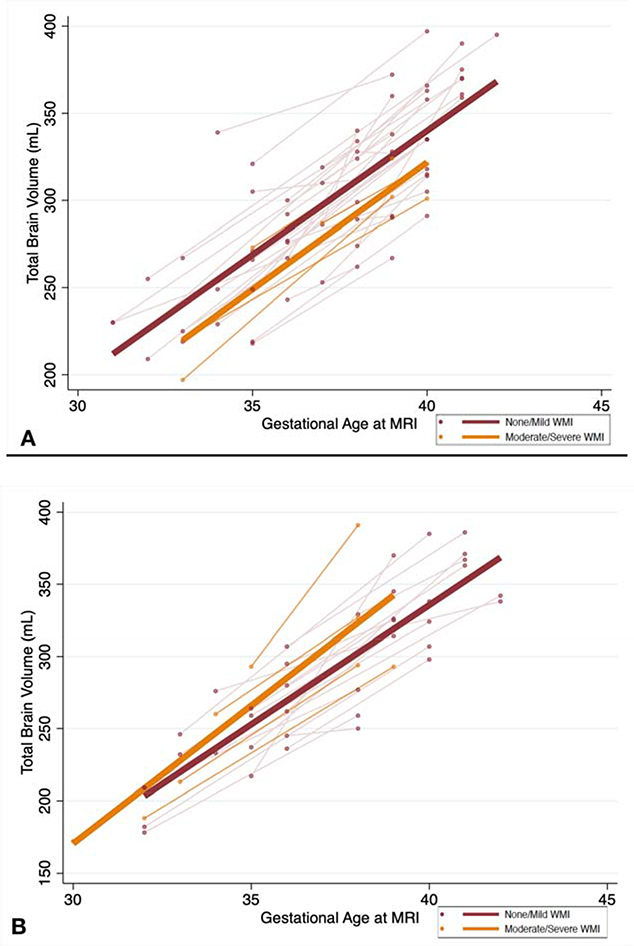

The average TBV on the fetal MRI and neonatal MRI are listed in Table 3 by cardiac group and WMI severity. The trajectory of TBV from the fetal to neonatal time period by WMI severity is depicted in Figures 2a and 2b. In d-TGA subjects, overall TBV was significantly lower in the group with acquired neonatal moderate to severe WMI after adjusting for postmenstrual age at scan and site (overall TBV was 14.8 mL (95% CI: −28.8, −0.73) lower each week from fetal to neonatal life in those with moderate to severe WMI compared to those with none/mild WMI, p= 0.04) (Table 4). However, the rate of change in TBV (i.e. rate of growth) did not differ by injury group. TBV increased at a rate of 15.5 mL/week (95% CI: 11.8–19.1) in the subjects with none/mild WMI while it increased at a rate of 13.8 mL/week (95% CI: 7.9–19.5) in those with moderate-severe WMI (p= 0.74). To account for differences in anatomy, a sensitivity analysis was performed removing the 4 d-TGA subjects with associated coarctation of the aorta. We observed a similar trend of a lower TBV among those with acquired neonatal moderate/severe WMI after adjusting for age at scan and site (overall TBV was 14.7 mL (95% CI: −31.7, 2.2) lower each week from fetal to neonatal life in those with moderate-severe WMI compared to those with none/mild WMI, p= 0.08) In HLHS subjects, no significant difference was noted in overall TBV between those with none/mild WMI and those with moderate-severe WMI (coefficient 14.8, 95% CI: −14.4, 44.1, p= 0.32) and there was no difference noted in rate of change in TBV between the groups (15.1 mL/week, 95% CI: 11.9–18.4 in none/mild WMI vs. 19.1 mL/week, 95% CI: 9.7–28.5 in mod-sev WMI, p= 0.27).

Table 3.

Fetal and neonatal total brain volume by white matter injury severity on the pre-operative neonatal MRI in each cardiac group

| d-TGA | HLHS (n= 26) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None/Mild WMI N= 33 |

Mod-Sev WMI N= 4 |

None/Mild WMI N= 21 |

Mod-Sev WMI N= 5 |

|

| Fetal TBV, mL Mean, 95% CI | 267.6 (254.1–281.1) |

244.1 (176.2–311.9) |

250.0 (231.3–268.7) |

225.1 (162.2–288.0) |

| Neonatal TBV, mL Mean, 95% CI | 336.6 (323.7–349.6) |

312.0 (292.6–331.4) |

330.1 (311.9–358.3) |

325.8 (276.4–375.1) |

TBV= total brain volume; d-TGA= d-transposition of the great arteries; HLHS= hypoplastic left heart syndrome; WMI= white matter injury

Figure 2. Rate of change in total brain volume from fetal to postnatal life in subjects with d-transposition of the great arteries(d-TGA) (A) and hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) (B) by white matter injury (WMI) severity.

The plots include fetal and neonatal brain MRI measures with a line connecting the fetal to neonatal measurement for each subject (light orange and light red) as well as a best-fitted line. The orange and light orange lines represent those with moderate to severe WMI and the red and light red lines represent those with none or mild WMI. The x-axis represents gestational age at the time of MRI and the y-axis represents total brain volume in mL. A) Among d-TGA subjects, overall total brain volume is significantly lower among those with acquired neonatal moderate to severe WMI after adjusting for gestational age at scan and site (p= 0.04) with no difference noted in rate of growth between the two time points by injury status (p=0.27); B) Among HLHS subjects, there was no significant difference in overall total brain volume or rate of growth by injury status.

Table 4.

Results from the repeated measures analysis assessing the relationship between total brain volume on both the fetal and neonatal scan with white matter injury severity on the postnatal scan in each cardiac group.

| d-TGA | HLHS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WMI Severity | Coefficient (95% CI)* | p-value | Coefficient (95% CI)* | p-value |

| None-Mild | Ref | Ref | ||

| Mod-Severe | −14.8 (−28.8, −0.73) | 0.04 | 14.8 (−14.4, 44.1) | 0.32 |

The coefficient represents the difference in overall total brain volume between those with moderate to severe white matter injury compared to those with none or mild white matter injury after accounting for gestational age at scan and site

d-TGA= d-transposition of the great arteries; HLHS= hypoplastic left heart syndrome; WMI= white matter injury

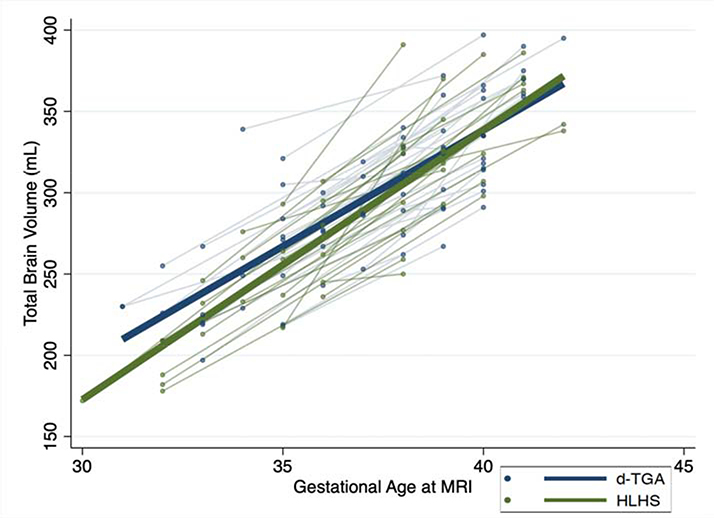

Finally, we noted no difference in the rate of growth from fetal to neonatal life by cardiac diagnosis. TBV increased by 15.3 mL/week in d-TGA and 15.9 mL/week in HLHS. The difference in slopes per 1 week increase in postmenstrual age was minimal at 1.6 mL, 95% CI: −0.61, 3.8, p= 0.16 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Rate of change in total brain volume from fetal to postnatal life by cardiac diagnosis group, d-transposition of the great arteries (d-TGA) or hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS).

The plots include fetal and neonatal brain MRI measures with a line connecting the fetal to neonatal measurement for each subject (light blue and light green) as well as a best-fitted line. The blue and light blue lines represent those with d-TGA and the green and light green lines represent those with HLHS. The x-axis represents gestational age at the time of MRI and the y-axis represents total brain volume in mL. No difference was noted in overall total brain volume or in the rate of change from fetal to neonatal life between the two cardiac groups (p= 0.16).

Discussion:

In this prospective longitudinal study across three sites, we demonstrate that lower TBV as a measure of brain maturity beginning in the 3rd trimester of fetal life is associated with increased risk of acquired moderate to severe WMI in the neonatal pre-operative period in patients with d-TGA, but not in HLHS. Interestingly, rate of perinatal brain growth, though similar between d-TGA and HLHS was not a risk factor for injury in either group. Our results identify important differences between HLHS and d-TGA with regard to acquired postnatal brain injury that brings to light several physiologic considerations that are unique to the fetus with complex CHD.

The overall model that informed our study design is the concept that fetuses with CHD and restricted oxygen/nutrient delivery have delayed brain development4,10 that heightens their postnatal susceptibility to WMI via instability during the perinatal transitional period. The mechanism of acquired WMI in term neonates with complex CHD is thought to be secondary to hypoxic-ischemic injury to susceptible immature premyelinating oligodendrocytes similar to the mechanism seen in premature infants6. Similar to prior studies we did not identify WMI on fetal MRI, thus we designed our study to determine if brain immaturity beginning in the fetal time period is associated with postnatal acquired brain injury. Given the myriad of risk factors associated with WMI in the CHD population after birth7–9, isolating the relationship between brain maturity and WMI has been challenging with varying results in the literature. Semi-quantitative techniques have suggested that brain immaturity is a risk factor for WMI12,13, while other studies utilizing quantitative diffusion weighted imaging have not found similar results8. As a crude measure of brain immaturity, relative prematurity (i.e. early term birth) has been associated with increased risk of pre-operative WMI in patients with CHD14,15, which was a trend observed in our study. In the present study, we found that in subjects with d-TGA, fetal total brain volume is lower and continues to remain low after birth among those that go on to acquire postnatal moderate to severe WMI compared to those who do not.

A piglet CHD model demonstrates that hypoxia impairs the generation and migration of neural progenitors destined to become forebrain interneurons and reduces overall cortical growth16. It is possible, that within the d-TGA group, there are varying degrees of impaired oxygen and nutrient delivery to the brain such that a certain subset of patients have a greater decline in cortical growth, overall brain volumes and maturation. Those with the most brain immaturity may be particularly vulnerable to hemodynamic instability that occurs after placental separation and is often difficult to predict prenatally17 leading to significant WMI. Pre-operative brain injury is more common in d-TGA compared with new post-operative brain injury18, suggesting that fetal, perinatal and neonatal risk factors play an important role in the development of acquired injury.

Perinatal brain ischemia may be a significant contributor to risk of WMI in the setting of brain immaturity. Animal models support a role for cerebral ischemia in acquired WMI in addition to hypoxemia. In particular, systemic hypotension and cerebral hypo-perfusion resulting from umbilical cord occlusion in the fetal lamb model results in periventricular white matter injury as well as injury to the cerebral cortex19,20. In the normal newborn, the transitional circulation results in a 3–5 fold increase in left ventricular output due to the decline in pulmonary vascular resistance and increase in pulmonary blood flow. This is mirrored by dramatic reductions in output from the right ventricle with removal of the umbilical circulation21,22. In contrast to the normal fetus, in d-TGA, cerebral circulation is largely driven by output from the right ventricle and is thus more dependent on systemic venous return. These hemodynamic aberrations unique to the fetus with d-TGA may lead to varying degrees of cerebral ischemia during the transitional period from fetal to neonatal life further contributing to acquired perinatal WMI. In addition, lower PaO2 levels prior to corrective cardiac surgery has been associated with WMI in d-TGA9. In the setting of an immature brain, these patients may be even more sensitive to relatively low PaO2 levels supporting timely interventions for those with a restrictive atrial communication and/or earlier corrective surgery18. Given that all of the subjects in this cohort were prenatally diagnosed, this cohort is likely generally healthier with regard to perinatal clinical characteristics and brain health compared to postnatally diagnosed patients23,24. Despite this advantage, a significant percentage of subjects with d-TGA in our cohort had evidence of postnatal WMI prior to surgery, highlighting the potential significance of the transitional circulation as it pertains to perinatal/ delivery room and pre-operative management to protect cerebral blood flow and minimize ischemia. Our findings potentially provide a mechanism to prenatally identify d-TGA subjects that are the most vulnerable to ischemia and thus at highest risk of acquired WMI after birth to allow for clinical care that provides the highest degree of neuroprotection.

Interestingly, perinatal brain growth from the fetal to postnatal time period did not differ by cardiac group, similar to a prior study25. Oxygen and nutrient delivery to the fetal brain are thought to be similar between HLHS and d-TGA as seen by lower oxygen saturation levels in the ascending aorta by fetal cardiac MRI. In addition, both subgroups demonstrate trends towards decreased cerebral oxygen delivery and significantly lower cerebral oxygen consumption compared with controls10. Despite the similarity in perinatal brain growth, the two groups diverged in the association between brain immaturity and acquired postnatal WMI. No significant association was identified between brain immaturity and acquired postnatal WMI in HLHS suggesting that the underlying fetal and perinatal physiology has different implications for postnatal risk of WMI in this group compared to d-TGA. In particular, anatomic factors within the HLHS group may contribute more to susceptibility to WMI during the perinatal transitional period. As described above, changes during transitional circulation such as a decline in pulmonary vascular resistance and increase in pulmonary blood flow leads to a significant increase in LV output with a decline in RV output in the normal neonate. In the setting of HLHS with varying degrees of left heart hypoplasia, cerebral blood flow and risk of ischemia might be more variable in the transitional period depending on the presence or absence of antegrade flow across the aorta. Thus, those at the extreme end of the spectrum with aortic atresia and lack of any antegrade flow to the brain are likely at highest risk of ischemia and acquiring WMI during the transitional period. In fact, all 5 HLHS subjects with moderate to severe WMI had aortic atresia in our cohort. Indeed postnatal studies have demonstrated an association between aortic atresia and smaller ascending aorta size with impairments in white matter microstructure both at birth26 and later in life27. Our findings for both d-TGA and HLHS suggest that future studies should focus on the transitional circulation and its impact on cerebral blood flow and risk of WMI including incorporation of anatomical details to tailor possible interventions.

Our study was strengthened by the prospective design with longitudinal fetal and neonatal MRI scans. In addition, our study reports findings within homogeneous groups of patients with either HLHS or d-TGA allowing for analysis by cardiac physiology. However, our findings are limited by the relatively small sample size making it challenging to determine causality in the relationship between brain maturity and injury. The multi-center nature of this study may lead to unmeasured confounders that can influence the relationship between brain maturity and WMI; however, this was addressed by adjusting for site in our analysis.

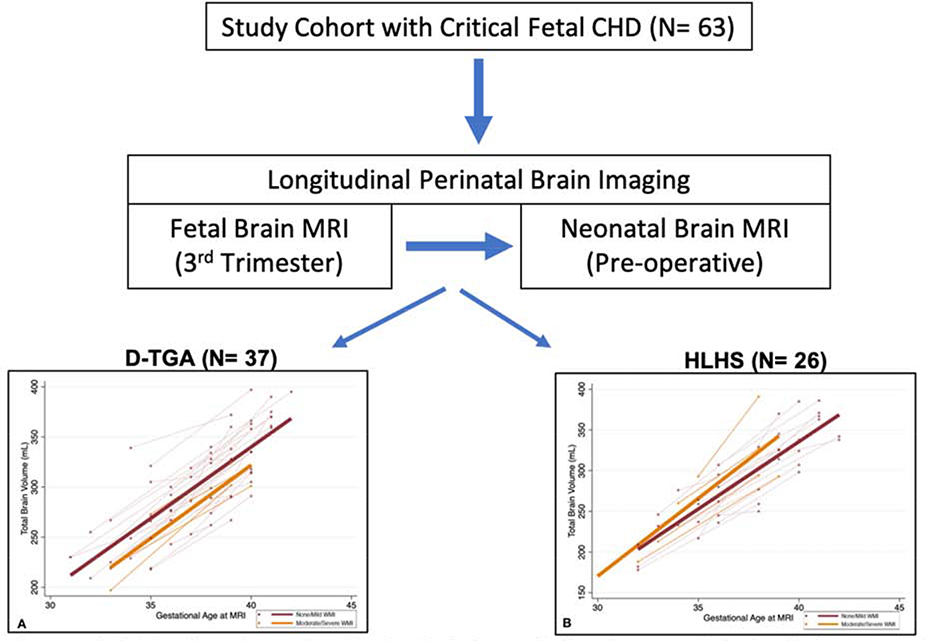

In conclusion, perinatal brain development appears to be related to the risk of clinically significant acquired postnatal WMI, particularly in patients with d-TGA (Figure 4). Given the association between moderate to severe WMI and poor motor outcomes in infancy3, these findings aid in identifying imaging markers before birth to predict neurologic outcomes. In addition, our results can help inform clinical trials on perinatal interventions aimed at optimizing brain development and minimizing clinically significant brain injury in the CHD population.

Figure 4:

Graphical summary of study findings. A total of 63 subjects were included of which 37 had d-transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA) and 26 had hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). Subjects underwent a fetal brain MRI in the 3rd trimester followed by a neonatal MRI prior to their cardiac operation.

Supplementary Material

Central Picture:

Fetal brain volumetry in a fetus with congenital heart disease. Segmentation of a 3-dimensional steady-state free-precession acquisition was performed to measure total brain volume. The image depicted is the final volumetric image of the fetal brain.

Central Message: Smaller total brain volume beginning in utero is associated with acquired clinically significant white matter injury after birth among those with d-transposition of the great arteries.

Perspective Statement:

Patients with CHD have delayed brain development and are at risk for brain injury after birth. In this longitudinal study from fetal to neonatal life, we identify an association between brain immaturity and acquired brain injury in d-transposition of the great arteries but not hypoplastic left heart syndrome, highlighting the importance of cardiac physiology in our understanding of brain health in CHD.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by grants K23 NS099422, R01 NS40117, R01 NS063876, R01 EB009756, P01 NS082330 from the National Institutes of Health (NINDS), MOP-142204, MOP-93780 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and The Bloorview Children’s Hospital Chair in Pediatric Neuroscience (SPM).

Glossary of Abbreviations:

- WMI

white matter injury

- CHD

congenital heart disease

- HLHS

hypoplastic left heart syndrome

- d-TGA

d-transposition of the great arteries

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- UCSF

University of California San Francisco

- UBC

University of British Columbia

- UT

University of Toronto

- TBV

total brain volume

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

IRB Approval: The institutional committee on human research approved the study protocol at each site. UCSF: 10–03749 (10/2001) & 18–25582 (9/26/2018); UT: 1000051521 (4/26/2016); UBC: H05–70524 (04/2006)

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Licht DJ, Wang J, Silvestre DW, Nicolson SC, Montenegro LM, Wernovsky G, et al. Preoperative cerebral blood flow is diminished in neonates with severe congenital heart defects. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004December;128(6):841–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McQuillen PS, Barkovich AJ, Hamrick SEG, Perez M, Ward P, Glidden DV, et al. Temporal and anatomic risk profile of brain injury with neonatal repair of congenital heart defects. Stroke. 2007February;38(2 Suppl):736–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peyvandi S, Chau V, Guo T, Xu D, Glass H, Synnes A, et al. Neonatal Brain Injury and Timing of Neurodevelopmental Assessment in Patients With Congenital Heart Disease. JAC. 2018May8;71(18):1986–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Limperopoulos C, Tworetzky W, McElhinney DB, Newburger JW, Brown DW, Robertson RL, et al. Brain volume and metabolism in fetuses with congenital heart disease: evaluation with quantitative magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Circulation. 2010January5;121(1):26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller SP, McQuillen PS, Hamrick S, Xu D, Glidden DV, Charlton N, et al. Abnormal brain development in newborns with congenital heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2007November8;357(19):1928–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Back SA, Miller SP. Brain injury in premature neonates: A primary cerebral dysmaturation disorder? Ann Neurol. 2014April;75(4):469–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goff DA, Shera DM, Tang S, Lavin NA, Durning SM, Nicolson SC, et al. Risk factors for preoperative periventricular leukomalacia in term neonates with hypoplastic left heart syndrome are patient related. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013July20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimitropoulos A, McQuillen PS, Sethi V, Moosa A, Chau V, Xu D, et al. Brain injury and development in newborns with critical congenital heart disease. Neurology. 2013July16;81(3):241–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petit CJ, Rome JJ, Wernovsky G, Mason SE, Shera DM, Nicolson SC, et al. Preoperative brain injury in transposition of the great arteries is associated with oxygenation and time to surgery, not balloon atrial septostomy. Circulation. 2009February10;119(5):709–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun L, Macgowan CK, Sled JG, Yoo S-J, Manlhiot C, Porayette P, et al. Reduced fetal cerebral oxygen consumption is associated with smaller brain size in fetuses with congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2015April14;131(15):1313–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Block AJ, McQuillen PS, Chau V, Glass H, Poskitt KJ, Barkovich AJ, et al. Clinically silent preoperative brain injuries do not worsen with surgery in neonates with congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010September;140(3):550–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beca J, Gunn JK, Coleman L, Hope A, Reed PW, Hunt RW, et al. New white matter brain injury after infant heart surgery is associated with diagnostic group and the use of circulatory arrest. Circulation. 2013March5;127(9):971–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andropoulos DB, Hunter JV, Nelson DP, Stayer SA, Stark AR, McKenzie ED, et al. Brain immaturity is associated with brain injury before and after neonatal cardiac surgery with high-flow bypass and cerebral oxygenation monitoring. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010March;139(3):543–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo T, Chau V, Peyvandi S, Latal B, McQuillen PS, Knirsch W, et al. White matter injury in term neonates with congenital heart diseases: Topology & comparison with preterm newborns. Neuroimage. 2019January15;185:742–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goff DA, Luan X, Gerdes M, Bernbaum J, D’Agostino JA, Rychik J, et al. Younger gestational age is associated with worse neurodevelopmental outcomes after cardiac surgery in infancy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012March;143(3):535–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morton PD, Korotcova L, Lewis BK, Bhuvanendran S, Ramachandra SD, Zurakowski D, et al. Abnormal neurogenesis and cortical growth in congenital heart disease. Sci Transl Med. 2017January25;9(374):eaah7029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donofrio MT, Levy RJ, Schuette JJ, Skurow-Todd K, Sten M-B, Stallings C, et al. Specialized delivery room planning for fetuses with critical congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2013March1;111(5):737–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim JM, Porayette P, Marini D, Chau V, Au-Young SH, Saini A, et al. Associations Between Age at Arterial Switch Operation, Brain Growth, and Development in Infants With Transposition of the Great Arteries. Circulation. 2019June11;139(24):2728–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Back SA, Riddle A, Dean J, Hohimer AR. The instrumented fetal sheep as a model of cerebral white matter injury in the premature infant. Neurotherapeutics. 2012April;9(2):359–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Back SA. Cerebral white and gray matter injury in newborns: new insights into pathophysiology and management. Clin Perinatol. 2014March;41(1):1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudolph A Congenital Diseases of the Heart. John Wiley & Sons; 2011. 1 p. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crossley KJ, Allison BJ, Polglase GR, Morley CJ, Davis PG, Hooper SB. Dynamic changes in the direction of blood flow through the ductus arteriosus at birth. J Physiol (Lond). 2009October1;587(Pt 19):4695–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peyvandi S, De Santiago V, Chakkarapani E, Chau V, Campbell A, Poskitt KJ, et al. Association of Prenatal Diagnosis of Critical Congenital Heart Disease With Postnatal Brain Development and the Risk of Brain Injury. JAMA Pediatr. 2016February22;170(4):e154450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Algra SO, Haas F, Poskitt KJ, Groenendaal F, Schouten ANJ, Jansen NJG, et al. Minimizing the risk of preoperative brain injury in neonates with aortic arch obstruction. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2014December;165(6):1116–1122.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Claessens NHP, Khalili N, Isgum I, Heide Ter H, Steenhuis TJ, Turk E, et al. Brain and CSF Volumes in Fetuses and Neonates with Antenatal Diagnosis of Critical Congenital Heart Disease: A Longitudinal MRI Study. AJNR. 2019May;40(5):885–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sethi V, Tabbutt S, Dimitropoulos A, Harris KC, Chau V, Poskitt K, et al. Single-ventricle anatomy predicts delayed microstructural brain development. Pediatr Res. 2013May;73(5):661–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaidi AH, Newburger JW, Wypij D, Stopp C, Watson CG, Friedman KG, et al. Ascending Aorta Size at Birth Predicts White Matter Microstructure in Adolescents Who Underwent Fontan Palliation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018December18;7(24):e010395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.