Abstract

Abbreviations

- ACE

angiotensin‐converting enzyme

- ACE2

angiotensin‐converting enzyme type 2

- ACEi

angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor

- ADAM‐17

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain‐17

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- Ang1‐7

angiotensin 1‐7

- ARB

angiotensin type 1 receptor blocker

- AT1R

angiotensin type 1 receptor

- ET‐1

endothelin 1

- HSC

hepatic stellate cell

- IFN‐γ

interferon‐γ

- MasR

Mas receptor

- RAS

renin‐angiotensin system

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- TMPRSS2

transmembrane protease, serine 2

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) is a positive‐sense single‐stranded RNA virus, and the syndrome it causes is named the coronavirus disease outbreak, or COVID‐19, which was first diagnosed in the year 2019. To date, more than one and a half million patients have died of the illness worldwide.

In severe clinical cases, SARS‐CoV‐2 infects type II pneumocytes and leads to acute respiratory distress syndrome. Comorbidities, including chronic liver diseases, arterial hypertension, obesity, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular and pulmonary dysfunctions, worsen the prognosis of patients with COVID‐19.( 1 ) This is because the cell membrane‐bound metallopeptidase angiotensin‐converting enzyme type 2 (ACE2), the primary entry receptor for SARS‐CoV‐2, is ubiquitous, leading to multiple organs being involved in COVID‐19.( 2 , 3 ) ACE2, the viral receptor, is also an integral part of the nonclassical or tissue renin‐angiotensin system (RAS).

The Nonclassical RAS

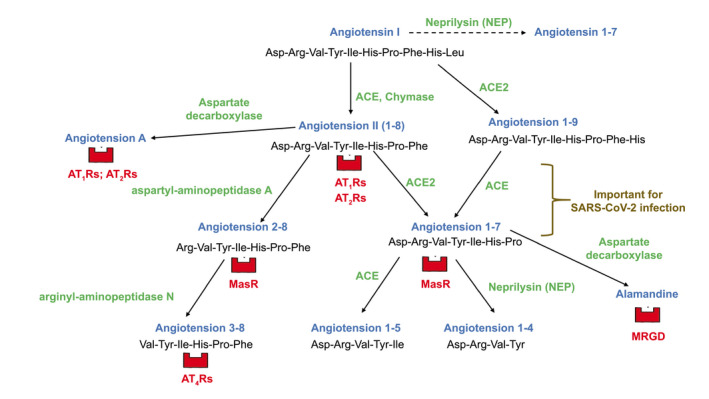

The nonclassical RAS is a network of enzymes and angiotensins (Fig. 1) derived from angiotensin II (Ang II) and involved in the regulation of inflammation and tissue blood perfusion. The major player is ACE2, a transmembrane protein with an extracellular N‐terminal domain containing a monocarboxypeptidase site and a transmembrane C‐terminal tail. ACE2 N‐terminal domain is the SARS‐CoV‐2 binding site.( 2 , 3 ) ACE2 cleaves the Pro7‐Phe8 bond of Ang II to form angiotensin 1‐7 (Ang1‐7), which binds to cell membrane G protein‐coupled receptors called Mas receptors (MasRs). This leads to vasodilatation and increased natriuresis through the production of arachidonic acid and increased cell levels of cyclic GMP.( 4 )

FIG. 1.

Diagram depicting pathways of synthesis and degradation of angiotensins in classical and nonclassical RAS, with respective receptors for each bioactive peptide. Classical RAS is defined as the ACE–Ang II–AT1R axis; the nonclassical RAS is composed of the ACE2–Ang1‐7–MasR axis, further metabolism of Ang1‐7, and the angiotensin 2‐8/angiotensin 3‐8 pathway. The main degradative pathway of Ang II in humans is through the sequential actions of plasma aminopeptidases A and N. AT1‐2‐4Rs, angiotensin type 1‐2‐4 receptors; MRGD, Mas‐related G protein‐coupled receptor member D.

The nonclassical RAS extends well beyond the ACE2‐Ang1‐7‐MasR axis. Ang1‐7 can be transformed into heptapeptide alamandine by an aspartate decarboxylase that converts Asp1 of Ang1‐7 into Ala1 of alamandine, which binds to Mas‐related G protein‐coupled receptor member D, leading to arterial vasodilatation.( 5 ) Cellular zinc‐metallo‐endopeptidase neprilysin can generate Ang1‐7 from angiotensin I but continues to metabolize Ang1‐7 at the Tyr4‐Ile5 bond to form inactive byproduct angiotensin 1‐4. Moreover, serine endopeptidase chymase, present in liver, heart, kidney, and ubiquitous mast cells, converts angiotensin I into Ang II as angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) does in the endothelium.( 4 )

The RAS Inside the Liver

ACE, Ang II, and its angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1R) as well as ACE2, Ang1‐7, MasRs, chymase, and neprilysin are expressed in the healthy and, especially, in the diseased liver, in which they modulate vascular tone and the development of progressive fibrosis during chronic injury. In the diseased liver, hepatic levels of Ang II are already elevated in pre‐cirrhosis animal models of liver fibrosis.( 6 ) Although the endothelium produces Ang II through ACE, chymase produces 80% of Ang II found in tissues. Ang II leads to hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation and production of profibrotic cytokines and connective tissue growth factors. Activated HSCs themselves express de novo ACE and AT1Rs and also synthesize Ang II.( 6 ) Ang II also activates infiltrating inflammatory cells, leading to their proliferation, production of inflammatory mediators (interleukin‐6 and tumor necrosis factor‐α), and chemotaxis. Therefore, the RAS system is already active inside the liver before the onset of cirrhosis. In patients with decompensated cirrhosis, hepatic levels of Ang II are much more elevated, spilling into the systemic circulation. This is related to chymase being massively up‐regulated in hepatocytes of regenerative nodules and α‐smooth muscle‐positive HSCs.( 7 ) In tissues with chronic inflammation, chymase also converts big endothelin 1 (ET‐1) into profibrotic polypeptide ET‐1.( 7 )

Liver neprilysin, another enzyme in the system, causes Ang1‐7 degradation and ET‐1 production from big ET‐1 and ET1‐31. In the cytosol fraction of the cirrhotic rat liver, neprilysin content is increased by 280%. This enzyme is localized mostly in desmin‐positive activated HSCs of fibrotic septa.( 8 )

ACE2 expression and Ang1‐7 synthesis are also increased in the cirrhotic liver,( 9 ) and the latter peptide is a negative regulator of the classical ACE–Ang II–AT1R axis. Ang1‐7 binds to the C‐terminal domain of ACE and reduces Ang II generation.( 10 ) Experimental liver fibrosis is aggravated by MasR antagonists( 6 ) and relieved by recombinant ACE2.( 11 ) Several studies have shown that activated ACE2‐Ang1‐7‐MasR axis reduces release of proinflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor α, interleukin‐6, and transforming growth factor β) that may cause liver cell apoptosis and necrosis followed by tissue fibrosis.( 10 ) Thus, it appears that having excess ACE2 is advantageous to the patient with liver cirrhosis.

In the cirrhotic liver, because of ACE, chymase, and neprilysin overexpression, faced by the sole increase in ACE2 activity, some 5‐fold increase in the Ang II/Ang1‐7 ratio occurs compared with normal liver.( 4 ) Any further damage to hepatic ACE2‐Ang1‐7‐MasR axis may lead to end‐stage liver disease. This occurs during the COVID‐19 clinical course.

SARS‐CoV‐2 and the Liver

ACE2 protein (SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor) is detectable at low levels in healthy livers, mostly in endothelial cells, occasional bile duct cells, and sparse centrilobular hepatocytes.( 9 ) In human cirrhosis, liver ACE2 mRNA levels are up‐regulated 34‐fold, ACE2 protein 97‐fold, and ACE2 immunostaining is identified in 80% of hepatocytes.( 9 ) Therefore, cirrhotic liver is highly susceptible to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Overexpression of ACE2 and increased synthesis of Ang1‐7 are also found in the mesenteric arterioles of patients with cirrhosis, contributing to the mesenteric hyperdynamic circulation that supports portal hypertension.( 12 , 13 ) After viral entry, SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA is found in the liver, along with microvacuolar steatosis, syncytial multinuclear hepatocytes, and lobular and portal inflammatory activity.( 14 ) In fatal cases, platelet‐fibrin microthrombi are identified in hepatic sinusoids at postmortem, and this is due to SARS‐CoV‐2–dependent endothelial dysfunction and coagulopathy.( 1 ) Aminotransferase levels are increased in up to 62% of patients with severe COVID‐19. Patients who are infected show hypoalbuminemia and elevation of gamma‐glutamyl transferase, but significant cholestasis is rare.( 15 ) In patients with underlying hepatic steatosis, >50% of COVID‐19 cases are severe, with 17% mortality. Liver cirrhosis is an independent risk factor of mortality in COVID‐19: the combined COVID‐HEP and SECURE‐Cirrhosis registries confirm that 38% of patients with cirrhosis and COVID‐19 had worsening ascites, encephalopathy, or acute kidney injury, and 40% of them died.( 16 ) In a group of patients with cirrhosis and COVID‐19 from North America, mortality was 30%, whereas that in patients with COVID‐19 alone was 13%.( 17 ) Among 50 Italian patients with cirrhosis and COVID‐19,( 18 ) 30‐day mortality was 34%; 64% of patients needed noninvasive respiratory support; when compared with the last outpatient visit before SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, bilirubin, international normalized ratio, alanine aminotransferase, and creatinine significantly increased, whereas albumin levels decreased; the percentage of patients with Child‐Pugh class C rose from 12% to 33%. Other contributors to increased mortality in cirrhosis during this pandemic include delayed screening or cancellation of elective therapeutic procedures for varices and hepatocellular carcinoma. Acute liver injuries related to drugs used to treat COVID‐19 have been described.( 15 )

SARS‐CoV‐2 Mechanisms of Liver Damage

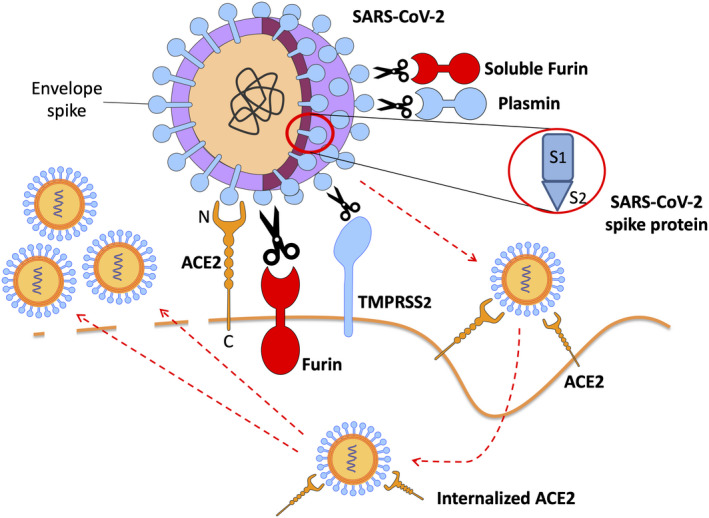

The spikes of SARS‐CoV‐2 envelope have an S glycoprotein that contains two functional domains: an S1 ACE2‐binding domain and an S2 domain essential for fusion of viral envelope and cell membranes.( 19 ) Cellular trypsin‐like transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2) cuts between S1 and S2 to allow viral entry into cells (Figs. 2 and 3). TMPRSS2 is highly expressed in hepatocytes, and priming of viral spikes is critical for infection.( 19 ) Host furin, an enzyme of the subtilisin‐like proprotein convertase family,( 3 ) and plasmin, a furin‐like protease,( 20 ) may also prime SARS‐CoV‐2 S glycoprotein at a site different from TMPRSS2 cleavage site. Once S glycoprotein is primed, clathrin‐dependent endocytosis of the parent virions into cells occurs.( 19 )

FIG. 2.

Mechanisms of COVID‐19 binding to cell membrane ACE2; viral spike glycoprotein priming into S1 and S2 subunits by host proteases furin, plasmin, and TMPRSS2; and viral entry along with ACE2 into human cells. Protease furin may be found as free‐floating in the extracellular fluids or as membrane‐bound enzyme. N‐terminal domain of ACE2 is the extracellular viral binding site, whereas ACE2 C‐terminal tail anchors the enzyme to plasma membranes.

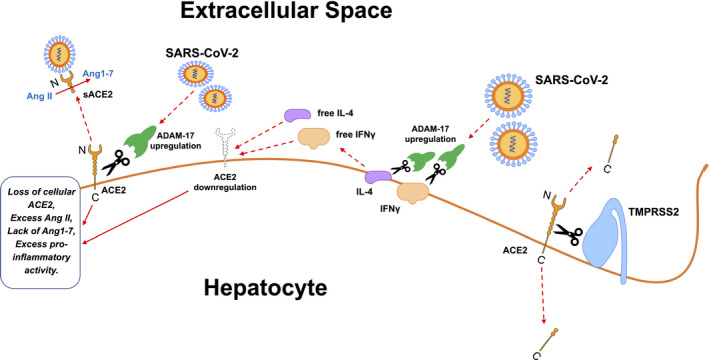

FIG. 3.

SARS‐CoV‐2 causes ACE2 cellular depletion through ADAM‐17 upregulation, and ADAM‐17‐mediated IL‐4 and IFN‐γ cellular shedding into extracellular fluids. In turn, free IL‐4 and IFN‐γ further down‐regulate ACE2 cellular expression. Arginine and lysine residues within ACE2 amino acids 697 to 716 are essential for ACE2 cleavage by TMPRSS2; ADAM‐17 requires arginine and lysine residues within ACE2 amino acids 652 to 659 for cleavage. Righthand side of the picture: C‐terminal ACE2 fragments of 13 kDa results from TMPRSS2 processing of cellular ACE2. Lefthand side of the picture: soluble ACE2 (sACE2), obtained through action of ADAM‐17 on cellular ACE2, is the complete N‐terminal ectodomain of the enzyme and is still able to bind SARS‐CoV2 and convert Ang II into Ang1‐7 in the extracellular space.

High plasmin levels are found in patients with cirrhosis, which is related to increased tissue‐type plasminogen‐activator activity and decreased alpha 2‐antiplasmin.( 21 ) Targeting plasmin with inhibitors (aprotinin, tranexamic acid) may be an option to reduce hyperfibrinolysis (critical to disease progression in COVID‐19) and viral spike priming in infected patients with cirrhosis.( 20 )

SARS‐CoV‐2 infection prompts inflammatory responses that depend on cellular depletion of ACE2.( 19 ) Firstly, internalization of ACE2 bound to virions reduces its availability on the cell surface. Secondly, unknown viral mediators induce gene expression of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain‐17 (ADAM‐17). ADAM‐17 functions as a “sheddase,” releasing anchored ACE2, interleukin‐4, and interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ) from the membranes of cells, including hepatocytes. Finally, free interleukin‐4 and IFN‐γ further down‐regulate membrane‐bound ACE2. TMPRSS2, beyond priming SARS‐CoV‐2 spikes, also cleaves ACE2 and competes with ADAM‐17 for ACE2 extracellular shedding.( 19 ) Loss of ACE2 leads to shift of the RAS to higher Ang II and lower Ang1‐7 tone. In patients with COVID‐19, plasma Ang II levels increase, and this correlates with the viral load in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.( 1 )

Moreover, ACE2 annihilation by SARS‐CoV‐2 means that clearance of inflammatory mediator des‐arginine bradykinin is reduced during infection because ACE2 metabolizes this peptide, which promotes pulmonary inflammation in COVID‐19 through stimulation of bradykinin B1 receptors in lung endothelial cells.( 22 ) Overexpression of endothelial bradykinin B1 receptors occurs in livers of rats with experimental cirrhosis.( 23 ) This may further fuel inflammation in the cirrhotic liver.

Ang II, through activation of extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK)1/ERK2, further reduces ACE2 cell expression.( 24 ) Therefore, any compound that blocks Ang II function, such as ACE inhibitors (ACEis) or AT1R blockers (ARBs), should increase ACE2 activity, as repeatedly shown in several experimental settings.( 2 ) The conundrum is that ACEis and ARBs may improve outcomes in patients with COVID‐19 through reduced Ang II function, but both drug classes increase ACE2 expression and potential susceptibility to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.( 2 ) Recent meta‐analyses demonstrate that RAS inhibitors might be associated with better prognosis in patients who are hypertensive with COVID‐19( 25 ) or, at least, that ARBs or ACEis should be continued in these participants,( 26 ) as ACEis also reduce Ang1‐7 clearance (Fig. 1). However, in patients with ascitic cirrhosis, ACEis and ARBs are not recommended because they significantly increase the risk of hypotension and renal failure.( 4 ) Unfortunately, this also holds true in decompensated cirrhosis with COVID‐19.

Potential Therapeutic Options

Drugs in development affect the nonclassical RAS and may be beneficial to patients with cirrhosis and COVID‐19. The principles whereby these drugs could help are (1) reduced viral entry and (2) increased Ang1‐7 activity (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Drugs Affecting Nonclassical RAS and COVID‐19

| Drugs Influencing Nonclassical RAS | Biomolecular and Functional Mechanisms | Pathophysiological Consequences in COVID‐19 | Potential Advantages in COVID‐19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACEis | Increase cellular ACE2 expression, decrease Ang 1‐7 clearance | Increase cellular adhesion of SARS‐CoV‐2 | Less inflammatory damage because of increased ACE2 |

| ARBs | Increase cellular ACE2 expression | Increase cellular adhesion of SARS‐CoV‐2 | Less inflammatory damage because of increased ACE2 |

| Metallopeptidase inhibitors (e.g., MLN‐4760) | Conformational change of ACE2 | Decrease cellular adhesion of SARS‐CoV‐2 | Limited viral spread to vital organs |

| Nonpeptidic Ang1‐7 analogs (e.g., AVE0991) | Agonist effects on MasRs | Replacement of reduced Ang1‐7 function | Less inflammatory damage |

| Neprilysin inhibitors (e.g., candoxatrilat) | Decrease Ang1‐7 clearance | Prolongation of Ang1‐7 half‐life | Less inflammatory damage |

| Trypsin‐like serine protease chymase inhibitors (e.g., SF2809E) | Reduce Ang II local release; inhibition of SARS‐CoV‐2 spike glycoprotein priming | Decrease cellular adhesion of SARS‐CoV‐2 | Less inflammatory damage; limited viral spread to vital organs |

| Intranasal recombinant human ACE2 | Interference with SARS‐CoV‐2 adhesion to cells; promotion of systemic Ang1‐7 synthesis | Decrease cellular adhesion of SARS‐CoV‐2 | Less inflammatory damage; limited viral spread to vital organs |

Metallopeptidase inhibitor MLN‐4760 causes a conformational change in the extracellular domain of ACE2 that mimics the closing of a clam shell, thereby potentially reducing SARS‐CoV‐2 cell binding and viral spread to vital organs.( 27 ) In isolated and perfused bile‐duct‐ligated liver of rat, intraportal MLN‐4760 infusion increases Ang1‐7 production, an effect abolished by neprilysin inhibition, showing that, when MLN‐4760 interferes with ACE2, liver neprilysin mostly converts angiotensin I into Ang1‐7, rather than degrading the latter( 28 ) (Fig. 1). This hepatic upsurge of Ang1‐7 could prove to be protective in patients with cirrhosis and COVID‐19. Because mesenteric ACE2 also contributes to the splanchnic hyperdynamic circulation of cirrhosis,( 12 , 13 ) MLN‐4760 is expected to reduce portal pressure in patients with cirrhosis and COVID‐19.( 28 )

In patients with COVID‐19, replacement of Ang1‐7 function is helpful. Compound AVE0991 is a nonpeptidic Ang1‐7 analog. AVE0991 can be administered orally and reduces intrahepatic resistance to portal flow and portal pressure in rats with experimental cirrhosis.( 29 )

Reduced Ang1‐7 clearance would benefit patients with COVID‐19. Candoxatrilat inhibits endopeptidase neprilysin, which cleaves Ang1‐7 into angiotensin 1‐4 and therefore increases Ang1‐7 hepatic concentrations. In experimental liver cirrhosis, candoxatrilat acutely reduces portal pressure and increases solute‐free water clearance and urinary excretions of sodium and cyclic GMP without effects on arterial pressure and plasma renin activity.( 8 , 30 )

Trypsin‐like serine protease inhibitors (camostat and nafamostat mesylates) may prevent host TMPRSS2 from priming viral spike glycoprotein.( 31 ) Trypsin‐like serine protease inhibitor SF2809E blocks chymase, the main source of Ang II in tissues, and might prevent TMPRSS2 from priming the spike glycoprotein. SF2809E decreases liver and kidney Ang II content, reduces portal pressure and liver fibrogenesis, and increases natriuresis in experimental carbon tetrachloride induced cirrhosis.( 7 )

Soluble ACE2 converts Ang II into Ang1‐7 in extracellular fluids and antagonizes SARS‐CoV‐2 binding to transmembrane ACE2 (Fig. 3). Recently, in early COVID‐19, recombinant human ACE2 has been delivered intranasally, avoiding the arterial hypotension observed during ACE2 intravenous infusion.( 31 )

Conclusions

Hepatic overexpression of SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor (ACE2) and ACE and bradykinin B1 receptors, along with systemic hyperplasminemia, predisposes patients with cirrhosis to a severe COVID‐19 clinical course. In order to modify SARS‐CoV‐2 interaction with ACE2, mimic beneficial Ang1‐7 effects, prolong Ang1‐7 half‐life, or reduce tissue production of Ang II, suitable drugs exist, although they are still not available on the market. These drugs deserve further development in the context of liver cirrhosis with COVID‐19.

Author Contributions

G.S., M.A., and F.W. were responsible for drafting of the article, critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, and final approval of the article.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1708‐1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. South AM, Diz DI, Chappell MC. COVID‐19, ACE2, and the cardiovascular consequences. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2020;318:H1084‐H1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abassi Z, Assady S, Khoury EE, Heyman SN. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2—an ally or a Trojan horse? Implications to SARS‐CoV‐2 related cardiovascular complications. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2020;318:H1080‐H1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sansoè G, Aragno M, Wong F. Pathways of hepatic and renal damage through non‐classical activation of the renin‐angiotensin system in chronic liver disease. Liver Int 2020;40:18‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Annweiler C, Cao Z, Wu Y, Faucon E, Mouhat S, Kovacic H, et al. Counter‐regulatory ‘renin‐angiotensin’ system‐based candidate drugs to treat COVID‐19 diseases in SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected patients. Infect Disord Drug Targets 2020;20:407‐408. 10.2174/1871526520666200518073329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Warner FJ, Rajapaksha H, Shackel N, Herath CB. ACE2: From protection of liver disease to propagation of COVID‐19. Clin Sci 2020;134:3137‐3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sansoè G, Aragno M, Mastrocola R, Mengozzi G, Novo E, Parola M. Role of chymase in the development of liver cirrhosis and its complications: Experimental and human data. PLoS One 2016;11:e0162644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sansoè G, Aragno M, Mastrocola R, Restivo F, Mengozzi G, Smedile A, et al. Neutral endopeptidase (EC 3.4.24.11) in cirrhotic liver: A new target to treat portal hypertension? J Hepatol 2005;43:791‐798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Paizis G, Tikellis C, Cooper ME, Schembri JM, Lew RA, Smith AI, et al. Chronic liver injury in rats and humans upregulates the novel enzyme angiotensin converting enzyme 2. Gut 2005;54:1790‐1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brojakowska A, Narula J, Shimony R, Bander J. Clinical implications of SARS‐CoV‐2 interaction with renin angiotensin system. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:3085‐3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Österreicher CH, Taura K, De Minicis S, Seki E, Penz‐Österreicher M, Kodama Y, et al. Angiotensin‐converting‐enzyme 2 inhibits liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology 2009;50:929‐938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grace JA, Klein S, Herath CB, Granzow M, Schierwagen R, Masing N, et al. Activation of the MAS receptor by angiotensin‐(1‐7) in the renin‐angiotensin system mediates mesenteric vasodilatation in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2013;145:874‐884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Casey S, Schierwagen R, Mak K, Klein S, Uschner F, Jansen C, et al. Activation of the alternate renin‐angiotensin system correlates with the clinical status in human cirrhosis and corrects post liver transplantation. J Clin Med 2019;8:419‐431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bourgonje AR, Abdulle AE, Timens W, Hillebrands JL, Navis GJ, Gordijn SJ, et al. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), SARS‐CoV‐2 and the pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). J Pathol 2020;251:228‐248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ridruejo E, Soza A. The liver in times of COVID‐19: What hepatologists should know. Ann Hepatol 2020;19:353‐358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kushner T, Cafardi J. Chronic liver disease and COVID‐19: Alcohol use disorder/alcohol‐associated liver disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, autoimmune liver disease, and compensated cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis 2020;15:195‐199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bajaj JS, Garcia‐Tsao G, Biggins SW, Kamath PS, Wong F, McGeorge S, et al. Comparison of mortality risk in patients with cirrhosis and COVID‐19 compared with patients with cirrhosis alone and COVID‐19 alone: multicentre matched cohort. Gut 2020. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iavarone M, D'Ambrosio R, Soria A, Triolo M, Pugliese N, Del Poggio P, et al. High rates of 30‐day mortality in patients with cirrhosis and COVID‐19. J Hepatol 2020;73:1063‐1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hoffmann M, Kleine‐Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020;181:271‐280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ji HL, Zhao R, Matalon S, Matthay MA. Elevated plasmin(ogen) as a common risk factor for COVID‐19 susceptibility. Physiol Rev 2020;100:1065‐1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leebeek FW, Kluft C, Knot EA, de Maat MP, Wilson JH. A shift in balance between profibrinolytic and antifibrinolytic factors causes enhanced fibrinolysis in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1991;101:1382‐1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Van de Veerdonk FL, Netea MG, van Deuren M, van der Meer JW, de Mast Q, Brüggemann RJ, et al. Kallikrein‐kinin blockade in patients with COVID‐19 to prevent acute respiratory distress syndrome. eLife 2020;9:e57555. 10.7554/eLife.57555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nagaoka MR, Gomiero L, Teixeira FO, Agostino FG, Pouza JEP, Mimary P, et al. Is the expression of kinin B1 receptor related to intrahepatic vascular response? Biochim Biophys Acta 2006;1760:1831‐1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S, Huan Y, Guo F, Guan B, et al. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature 2005;436:112‐116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pirola CJ, Sookoian S. Estimation of renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone‐system (RAAS)‐inhibitor effect on COVID‐19 outcome: A meta‐analysis. J Infect 2020;81:276‐281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Flacco ME, Martellucci CA, Bravi F, Parruti G, Cappadona R, Mascitelli A, et al. Treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs and risk of severe/lethal COVID‐19: A meta‐analysis. Heart 2020;106:1519‐1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Towler P, Staker B, Prasad SG, Menon S, Tang J, Parsons T, et al. ACE2 X‐ray structures reveal a large hinge‐bending motion important for inhibitor binding and catalysis. J Biol Chem 2004;279:17996‐18007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Herath CB, Lubel JS, Jia Z, Velkoska E, Casley D, Brown L, et al. Portal pressure responses and angiotensin peptide production in rat liver are determined by relative activity of ACE and ACE2. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2009;297:G98‐G106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klein S, Herath CB, Schierwagen R, Grace J, Haltenhof T, Uschner FE, et al. Hemodynamic effects of the non peptidic angiotensin‐(1‐7) agonist AVE0991 in liver cirrhosis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0138732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sansoè G, Aragno M, Mastrocola R, Cutrin JC, Silvano S, Mengozzi G, et al. Overexpression of kidney neutral endopeptidase (EC 3.4.24.11) and renal function in experimental cirrhosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2006;290:F1337‐F1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Datta PK, Liu F, Fischer T, Rappaport J, Qin X. SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic and research gaps: Understanding SARS‐CoV‐2 interaction with the ACE2 receptor and implications for therapy. Theranostics 2020;10:7448‐7464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]