Abstract

Background and purpose

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection predisposes patients to arterial and venous thrombosis. This study aimed to systematically review the available evidence in the literature for cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) in association with coronavirus disease‐2019 (COVID‐19).

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases to identify cases of COVID‐19–associated CVT. The search period spanned 1 January 2020 to 1 December 2020, and the review protocol (PROSPERO‐CRD42020214327) followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses guidelines. Identified studies were evaluated for bias using the Newcastle‐Ottawa scale. A proportion meta‐analysis was performed to estimate the frequency of CVT among hospitalized COVID‐19 patients.

Results

We identified 57 cases from 28 reports. Study quality was mostly classified as low. CVT symptoms developed after respiratory disease in 90%, and the mean interval was 13 days. CVT involved multiple sites in 67% of individuals, the deep venous system was affected in 37%, and parenchymal hemorrhage was found in 42%. Predisposing factors for CVT beyond SARS‐CoV‐2 infection were present in 31%. In‐hospital mortality was 40%. Using data from 34,331 patients, the estimated frequency of CVT among patients hospitalized for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection was 0.08% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.01–0.5). In an inpatient setting, CVT accounted for 4.2% of cerebrovascular disorders in individuals with COVID‐19 (cohort of 406 patients, 95% CI: 1.47–11.39).

Conclusions

Cerebral venous thrombosis in the context of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is a rare, although there seems to be an increased relative risk. High suspicion is necessary, because the diagnosis of this potentially life‐threatening condition in COVID‐19 patients can be challenging. Evidence is still scarce on the pathophysiology and potential prevention of COVID‐19–associated CVT.

Keywords: cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, cerebral venous thrombosis, coronavirus, COVID‐19, intracranial complication, intracranial sinus thrombosis, SARS‐CoV‐2

Cerebral venous thrombosis can happen in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 infection. Early diagnosis and proper management are paramount, as it is associated with high mortality.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease‐2019

- CVT

cerebral venous thrombosis

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2

INTRODUCTION

The outbreak of the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, has rapidly evolved into a pandemic. The clinical features of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (coronavirus disease‐19 [COVID‐19]) and its prognosis are manifold. They range from asymptomatic infection to severe viral pneumonia with respiratory failure and high fatality rates [1]. Importantly, angiotensin converting enzyme‐2, the primary receptor utilized by SARS‐CoV‐2 for cell entry, is not only expressed in the lungs but also in the central nervous system and vascular endothelial cells [2]. There is emerging evidence for neurological complications of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection [3, 4]. Both neuroinvasive disease and parainfectious complications [3] as well as an increased risk of stroke and thrombotic complications, have been described in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection [5, 6, 7, 8]. Likewise, pulmonary embolism was identified as a major cause of sudden death in these patients [9]. Several factors have been hypothesized to contribute to this observation. They include immobility, reduced effectivity of thromboprophylaxis, prothrombotic events caused by cytokine storm, and either tropism of SARS‐CoV‐2 to endothelial cells or the ability of SARS‐CoV‐2 to damage endothelial cells [5, 6, 8, 10].

Despite the attention given to cerebrovascular thrombotic events, few reports have addressed the risk of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVT) in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Given the higher risk of thrombosis among patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, it is not unforeseen that the number of reports on CVT in the context of COVID‐19 is increasing in the literature [11, 12, 13]. CVT is a rarer form of venous thrombosis, which predominantly affects younger individuals. As CVT is a potentially life‐threatening cause of stroke that may be preventable in the context of COVID‐19, it is important to describe the clinical, radiological, and paraclinical features, management, and prognosis of the condition. In this study, we aimed to summarize the current knowledge on the frequency and disease characteristics of SARS‐CoV‐2–related CVT on the basis of a systematic review of the literature and meta‐analysis.

METHODS

Search strategy

A systematic review was carried out to collect all cases reporting CVT in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. The protocol followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses guidelines for reporting of systematic reviews and was registered with PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; CRD42020214327). MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases were searched for articles published from January 1 2020 to December 1 2020 regarding CVT and COVID‐19. The search strategy included the following terms, as either keywords or Medical Subject Headings: (i) COVID, coronavirus, or SARS‐CoV‐2 and (ii) cerebral venous thrombosis, intracranial sinus thrombosis, or cranial sinus thrombosis (search string available in Supplementary Material). Reference lists and cited articles were also reviewed to increase the identification of relevant studies.

Selection criteria, bias assessment, and data sharing

No limitations were imposed on study type: case reports, case series, observational and interventional studies, as well as randomized controlled trials were considered. We restricted studies to those published in English and excluded studies based on animal models and preclinical settings. Reviews, editorials, and letters were discarded unless they provided original data.

The search aimed to select studies reporting CVT in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection; therefore, reports of CVT occurring later than 2 months after the resolution of SARS‐CoV‐2–related symptoms were excluded. Two reviewers (T.B., G.M.A.) independently evaluated the results of the systematic review and selected the studies according to prespecified criteria. Disagreement was resolved by the corresponding author (M.R.).

Biases were assessed with the Newcastle‐Ottawa scale, which included ratings of selection bias, assessment bias, comparability issues, causality, and reporting bias as previously performed [14, 15].

Data extraction, qualitative, and quantitative synthesis

The following data were extracted from studies identified via the search strategy outlined above: study design, number of patients hospitalized with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, number of cases of CVT, risk factors for CVT, clinical and neuroradiological features of CVT, laboratory tests (including D‐dimer, fibrinogen, and thrombophilic screening), treatment of CVT, and clinical–neuroradiological follow‐up, if available. Two reviewers (T.B., G.M.A.) independently extracted data from selected articles. Disagreement was resolved by the supervising author (M.R.).

Qualitative and quantitative synthesis was performed to assess occurrence rate of CVT among people hospitalized with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Moreover, we studied the spectrum of known risk factors for CVT in these patients. We also evaluated clinical and radiological features, management (including anticoagulation and anticonvulsive drugs), and short‐term prognosis. Regarding the latter, we examined the clinical status as defined by each study, including the corresponding modified Rankin Scale score at the last available follow‐up, as well as mortality after CVT. We reported lack of data whenever needed.

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics were calculated, and descriptive statistics were presented as mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, and counts and percentage for categorical variables. We used t tests and χ2 tests as appropriate. We performed statistical analyses pooling data extracted from selected studies. To calculate the proportion of CVT in hospitalized patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, we excluded case reports and case series, as no denominator was available, and pooled estimates only from large cohort studies including consecutive hospitalized patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Heterogeneity was assessed by means of Cochrane's Q test and I 2 statistics [16]. Meta‐analysis of proportions was performed by using a DerSimonian‐Laird random‐effects model due to consistent differences in design and assessment across studies. Reported probability values were two‐sided, with significance set at p < 0.05. Visual inspection of funnel plots was used to assess reporting bias. Sensitivity analysis through a leave‐one‐out paradigm was planned. Statistical analysis was performed with R v.3.3.1, and the “meta” package for meta‐analysis of proportions.

RESULTS

Results of the systematic review and bias assessment

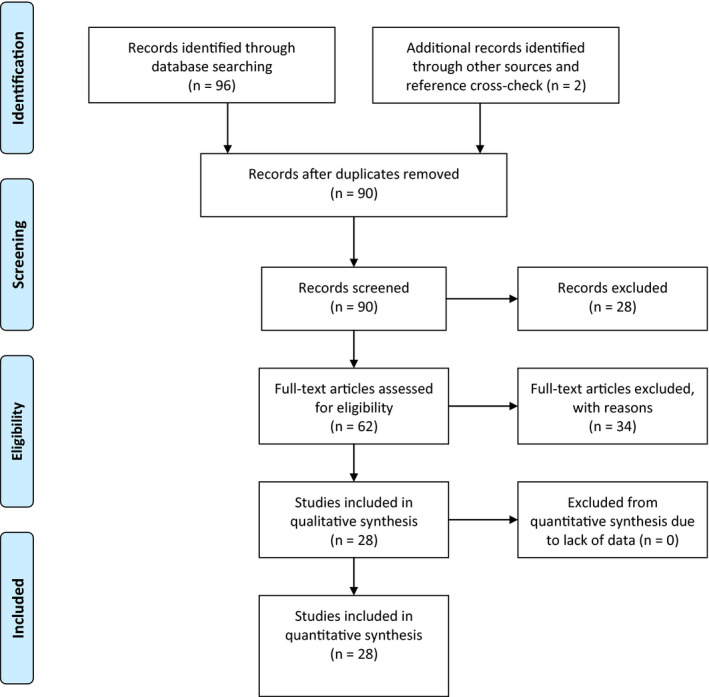

The systematic search yielded 90 articles, of which 62 underwent full‐text assessment (Figure 1). Thirty‐four were excluded because they were commentaries, letters, or reviews (Supplementary Material, Table 1 for excluded studies and reason).

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses flowchart. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the CVT cases

| Author | Year | Design | Study sample size |

CVT (n) |

Age, years (mean) |

Sex (female/total) | SARS‐Cov‐2 testing | COVID‐19 systemic symptoms | Abnormal lung imaging (CT/x‐ray) | CVT symptoms start in relation to systemic symptoms | Interval between systemic and CVT symptoms (days) | Known risk factors for CVT other than SARS‐CoV‐2 infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baudar [27] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 33 | 1/1 | NP swab PCR/serology | Fever, dyspnea, cough, anosmia | No | After | 36 | Oral contraceptive |

| Bolaji [24] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 63 | 0/1 | NP swab PCR | Fever, dyspnea, cough | Yes | After | 9 | No |

| Cavalcanti [28] | 2020 | Case report | 3 | 3 | 34 | 1/3 | NP swab PCR | Fever, cough, headache, vomit, diarrhea | Yes | After | 7.5 | Oral contraceptive (n = 1) |

| Chougar [29] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 72 | 0/1 | NP swab PCR | (Unspecified) mild respiratory symptoms | NA | After | Few days | No |

| Chow [17] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 72 | 1/1 | NP swab PCR | Cough | Yes | After | 47 | Polycythemia vera |

| Dahl‐Cruz [35] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 53 | 0/1 | NP swab PCR | Fever, dyspnea, anosmia, myalgia | NA | After | 7 | No |

| Essajee [37] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1/1 | NP swab PCR | Dyspnea | Yes | Before | −3 | Tuberculous meningitis |

| Garaci [32] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 44 | 1/1 | NP swab PCR | Fever, dyspnea, cough | Yes | After | >20 | No |

| Haroon [41] | 2020 | Case series | 1 | 1 | 30 | 0/1 | NP swab PCR | cough | No | Before | 1 | No |

| Hemasian [33] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 65 | 0/1 | NP swab PCR | NA | Yes | NA | NA | No |

| Hoelscher [21] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 54 | 0/1 | NA | Pneumonia | Yes | After | 15 | NA |

| Hughes [34] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 59 | 0/1 | NP swab PCR | Fever | NA | Before | NA | No |

| Kananeh [42] | 2020 | Case series | 1 | 1 | 54 | 0/1 | NP swab PCR | Cough, dyspnea | Yes | After | 10 | No |

| Keaney [20] | 2020 | Case report | 2 | 2 | 61.5 | 1/2 | Clinico‐radiological diagnosis | Fever, dyspnea, cough | Yes | After | 15 | No |

| Klein [25] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 29 | 1/1 | NP swab PCR | Fever, dyspnea, cough, mild headache | Yes | After | 7 | No |

| Koh [36] | 2020 | Prospective observational | 47,572 | 4 |

NA (27–38) |

NA | NP swab PCR/serology | Asymptomatic (1), mild unspecified symptoms (3) | NA | With/after | 0–21 (interval) | Occipital skull fracture (n = 1) |

| Malentacchi [30] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 81 | 0/1 | NP swab PCR | Acute respiratory distress syndrome | NA | After | >18 | B‐cell lymphoma |

| Mowla [40] | 2020 | Retrospective observational case–control | NA | 13 | 50.9 | 8/13 | NP swab PCR (n = 12), clinico‐radiological (n = 1) | Asymptomatic (n = 1), mild–moderate respiratory symptoms (n = 9), severe symptoms (n = 1) | NA | With (n = 4), after (n = 9) | NA | Oral contraceptive (n = 3) |

| Poillon [31] | 2020 | Case series | 1 | 2 | 58 | 2/2 | NP swab PCR | Fever, dyspnea, cough | Yes | After | 14.5 | Breast cancer (n = 1) |

| Rifino [19] | 2020 | Retrospective observational | 1760 | 1 | 55 | 0/1 | NP swab PCR (83%) clinico‐radiological diagnosis (17%) a | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Rouyer [43] | 2020 | Case series | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | NP swab PCR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Roy‐Gash [26] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 63 | 1/1 | Serology (NP swab PCR negative) | Fever, cough, anosmia | Yes | After | 12 | NA |

| Shahjouei [23] | 2020 | Prospective observational | 17,799 | 6 | 50.3 | 4/6 | NP swab PCR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Siegler [22] | 2020 | Retrospective observational | 14,483 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Sugiyama [44] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 53 | 0/1 | NP swab PCR | Fever, malaise | Yes | After | 12 | No |

| Thompson [18] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 1 | 50 | 0/1 | Clinico‐radiological diagnosis a | Delirium | NA | After | 7 | No |

| Trimaille [38] | 2020 | Retrospective observational | 289 | 3 | NA | NA | NP swab PCR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tu [39] | 2020 | Case series | 2 | 2 | NA | 0/2 | NP swab PCR | Fever, chest pain (n = 1) | No | After (n = 1) | 4 (n = 1) | No |

| Overall | 81,929 b | 57 c | 53.5 ± 12.8 |

22/44 (50%) |

50/53 (94.3%) NP swab PCR | 39/42 (92.9%) | 17/21 (81%) | 36/40 (90%) with/after | 13 ± 11.6 | 11/36 (30.6%) |

Abbreviations: COVID‐19, coronavirus disease‐2019; CT, computed tomography; CVT, cerebral venous thrombosis; NA, not available; NP, nasopharyngeal; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2.

Negative NP swab PCR.

There were 81,903 from cohort studies.

There were 19 from cohort studies.

Overall, 28 reports of CVT in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection were included in the qualitative synthesis (Table 1) [17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38]. Four were retrospective observational studies describing cerebrovascular diseases in a cohort of SARS‐CoV‐2–positive patients [19, 22, 38, 39], two were prospective observational studies with consecutive enrolment [23, 36], one was a retrospective multicenter case series [40]; the remaining articles were retrospective case series or case reports. The largest study (n = 17,799) investigated all stroke subtypes, including CVT, ischemic, and hemorrhagic stroke, among patients hospitalized with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection across multiple hospitals in Europe, Asia, America, and Oceania [23].

Bias assessment revealed low quality for almost all studies, with only two case series [28, 40] with moderate quality (Table S1). Quality issues were mainly related to selection and reporting bias, as most of the cases were single reports. Moreover, studies addressing CVT occurrence in larger samples often did not report specific methods of assessment, causality, outcome, or follow‐up. Limitations in study quality were also related to uncertain exposure to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in some studies, because diagnosis could be based on clinical and radiological features or serology in the presence of a negative nasopharyngeal swab polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test but high clinical suspicion (Table S2) [18, 20].

Cohort characteristics, COVID‐19 diagnosis, and treatment

Overall, 57 CVT cases were collected from 28 reports (Table 1) [17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44]. Mean age was 53.5 years, with 11 cases presenting CVT at age <50 years and balanced gender distribution (50% female).

SARS‐CoV‐2 infection was ascertained through nasopharyngeal swab PCR in 50 out of 53 cases (92.1%; Table 1). Clinical and radiological criteria were used to establish diagnosis in three studies [18, 19, 20], one of which used such criteria to diagnose COVID‐19 even in light of a negative nasopharyngeal swab PCR test in 17% of the total cohort [19].

COVID‐19 symptom status was reported in 39/42 patients (92.9%). Only two studies reported CVT in patients asymptomatic for pulmonary or other systemic SARS‐CoV‐2 symptoms [36, 40]. High‐resolution computerized tomography of the chest or chest x‐ray demonstrated abnormalities consistent with pulmonary COVID‐19 in 81% of cases (17/21), with only four patients reported to have normal findings (Table 1) [27, 39, 41].

All patients received COVID‐19–specific treatment, which reflected local standard operating procedures and included hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, ritonavir, and antibiotics in suspected cases of superimposed bacterial pneumonia.

Cerebral venous thrombosis and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection

Six studies reported the occurrence of CVT in consecutively enrolled cohorts of patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection [19, 22, 23, 36, 38, 39]. Occurrence rates varied across the studies: 0.001% among all those diagnosed with COVID‐19 in Singapore [36, 39], 0.02% to 1% in multicenter cohorts of hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 (n = 17,799) [22, 23, 38], and 0.06% among hospitalized patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection referred for neurological assessment [19].

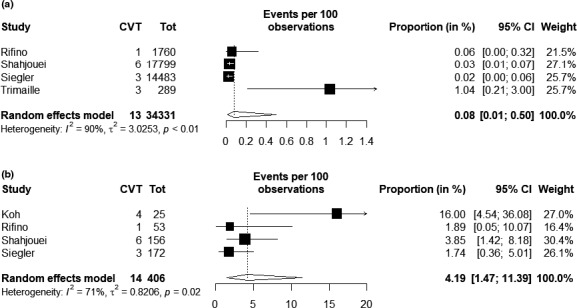

In pooling data from studies reporting events in hospitalized SARS‐CoV‐2 patients (n = 34,331) [19, 22, 23, 38], an estimated proportion of 0.08% of cases had CVT (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.01–0.50, p heterogeneity = 0.007; Figure 2a). Random‐effects modeling was justified by heterogeneity attributable to large samples, few events, and interstudy bias (Figure S1, Table 3). This would translate into an estimate of approximately 0.8 cases per 1,000 hospitalized patients with SARS‐CoV‐2. In pooling data from studies reporting numbers of cerebrovascular events among hospitalized patients (n = 406), CVT was reported in 4.19% of those cases (95% CI: 1.47–11.39, p heterogeneity = 0.02; Figure 2b), with leave‐one‐out sensitivity analyses yielding rates ranging from 2.8% to 5.7% (Table S3).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot for proportion estimates of patients having CVT among those hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection (a) and among those hospitalized with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and reported to have a cerebrovascular event (b). CI, confidence interval; CVT, cerebral venous thrombosis.

TABLE 3.

Neuroradiological features of CVT

| Author | Year | N | CTA/MRA | CVT single/multiple | Site of CVT | Venous infarct | Local edema | Hemorrhage | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superior sagittal | Straight | Transverse | Sigmoid | Internal jugular | Deep vein | Cortical vein | ||||||||

| Baudar [27] | 2020 | 1 | MRA | Single | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Bolaji [24] | 2020 | 1 | CTA | Multiple | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cavalcanti [28] | 2020 | 3 | CTA (1 DSA) | Multiple | Yes (n = 2) | Yes (n = 2) | Yes (n = 2) | Yes (n = 1) | Yes (n = 1) | Yes (n = 3) | Yes (n = 1) | Yes (n = 1) | NA | NA |

| Chougar [29] | 2020 | 1 | CTA + MRI | Multiple | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chow [17] | 2020 | 1 | CTA | Multiple | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Dahl‐Cruz [35] | 2020 | 1 | CTA | Multiple | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Na | Yes |

| Essajee [37] | 2020 | 1 | CTA | Multiple | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Garaci [32] | 2020 | 1 | CTA | Multiple | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Haroon [41] | 2020 | 1 | CTA + MRI | Multiple | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Hemasian [33] | 2020 | 1 | CTA + MRA | Multiple | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | NA | Yes |

| Hoelscher [21] | 2020 | 1 | CTA + MRI | Multiple | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Hughes [34] | 2020 | 1 | CTA | Multiple | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | NA | No |

| Kananeh [42] | 2020 | 1 | CTA + MRA | Multiple | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Keaney [20] | 2020 | 2 | CTA | Single | Yes (n = 2) | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (n = 2) | Yes (n = 2) | Yes (n = 2) |

| Klein [25] | 2020 | 1 | CTA + MRI | Multiple | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Koh [36] | 2020 | 4 | CTA | Multiple | Yes (n = 1) | No | Yes (n = 4) | Yes (n = 4) | Yes (n = 3) | No | No | NA | NA | Yes (n = 1) |

| Malentacchi [30] | 2020 | 1 | CTA | Single | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | NA | No |

| Mowla [40] | 2020 | 13 | CTA (n = 2), MRI (n = 11) | Mutiple (n = 4), single (n = 9) | Yes (n = 7) | Yes (n = 1) | Yes (n = 9) | NA | NA | NA | Yes (n = 5) | Yes (n = 2) | NA | Yes (n = 4) |

| Poillon [31] | 2020 | 2 | CTA + MRI | Single (n = 1), multiple (n = 1) | No | Yes (n = 1) | Yes (n = 2) | No | No | Yes (n = 1) | Yes (n = 1) | Yes (n = 1) | NA | Yes (n = 2) |

| Rifino [19] | 2020 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Rouyer [43] | 2020 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Roy‐Gash [26] | 2020 | 1 | CTA + MRI | Multiple | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Shahjouei [23] | 2020 | 6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Siegler [22] | 2020 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Sugiyama [44] | 2020 | 1 | MRI | Single | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Thompson [18] | 2020 | 1 | CTA | Multiple | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Trimaille [38] | 2020 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tu [39] | 2020 | 2 | CTA + MRI | Multiple | No | No | Yes (n = 2) | Yes (n = 2) | Yes (n = 1) | No | No | No | Yes (n = 1) | Yes (n = 1) |

| Overall | 57 | 30/43 (69.8%) CTA | 29/43 (67.4%) multiple | 19/43 (44.2%) | 9/43 (20.9%) | 28/43 (65.1%) | 14/30 (46.7%) | 6/30 (20%) | 11/30 (36.7%) | 9/43 (20.9%) | 16/43 (37.2%) | 12/30 (40%) | 18/43 (41.9%) | |

Abbreviations: COVID‐19, coronavirus disease‐2019; CTA, computed tomography angiography; CVT, cerebral venous thrombosis; DSA, digital subtraction angiography; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not available.

In four cases, CVT diagnosis preceded by a few days the onset of COVID‐19–related systemic symptoms, whereas in all other reports, CVT signs, symptoms, and diagnosis followed the onset of COVID‐19 (36/40, 90%) (Table 1). The interval between onset of COVID‐19 respiratory symptoms and CVT manifestation had a wide variability, ranging from the very same day of COVID‐19 onset to 47 days after COVID‐19 started.

Risk factors for CVT were reported inconsistently. Overall, details of known risk factors for CVT independent of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection were reported in 11 cases (30.6%): five women [27, 28, 40] were taking oral contraceptives; one individual had a previous diagnosis of polycythemia vera for which aspirin was taken as primary prevention [17], two individuals had solid tumors (one with breast cancer using hormone therapy and one with B‐cell lymphoma [30, 31]), one individual was a 3‐year old child with concomitant tuberculous meningitis [37] and another individual had concomitant traumatic occipital skull fracture [36]. No patient had preexisting thrombophilia or a history of previous CVT or deep venous thrombosis (Table 1).

CVT clinical and neuroradiological features

All patients had neurological signs or symptoms due to CVT. Among reports with detailed clinical features, an isolated headache pattern was reported in only one case [31], whereas all other cases presented with encephalopathy, focal signs, or seizures. Altered mental status was common (60.5%), whereas focal neurological signs varied according to CVT location and affected brain region, ranging from hemiparesis to aphasia. Epileptic seizures were reported in 10 cases (27.8%), and were focal (n = 3) [24, 27, 35], generalized tonic–clonic (n = 2) [25, 33] or refractory status epilepticus (Table 2) [29].

TABLE 2.

Clinical features of included cases of cerebral venous thrombosis

| Author | Year | Cause of admission | Mental status | Focal neurological signs/seizures | NIHSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baudar [27] | 2020 | Neurological | Altered | Focal impaired awareness seizure | NA |

| Bolaji [24] | 2020 | Neurological | Altered | Focal impaired awareness seizure, left hemiparesis | NA |

| Cavalcanti [28] | 2020 | Neurological | Altered (n = 2) | Aphasia | 15 |

| Chougar [29] | 2020 | Neurological | Altered | Left hemiparesis | NA |

| Chow [17] | 2020 | Neurological | Altered | Right hemiparesis | NA |

| Dahl‐Cruz [35] | 2020 | Neurological | Normal | Focal aware seizure | 3 |

| Essajee [37] | 2020 | Neurological | Altered | Left hemiparesis | NA |

| Garaci [32] | 2020 | Pulmonary | NA | NA | NA |

| Haroon [41] | 2020 | Neurological | Normal | Left arm paresis | NA |

| Hemasian [33] | 2020 | Neurological | Altered | Seizure | 0 |

| Hoelscher [21] | 2020 | Neurological | Altered | No | NA |

| Hughes [34] | 2020 | Neurological | Normal | Headache, right hemiparesis | 10 |

| Kananeh [42] | 2020 | Neurological | Altered | No | NA |

| Keaney [20] | 2020 | Pulmonary | Altered | No | NA |

| Klein [25] | 2020 | Neurological | Altered | Generalized tonic–clonic seizure | 15 |

| Koh [36] | 2020 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Malentacchi [30] | 2020 | Pulmonary | altered | No | NA |

| Mowla [40] | 2020 | NA | Altered (n = 5) | Seizure (n = 3) a , focal neurological signs (n = 2) | NA |

| Poillon [31] | 2020 | Pulmonary | Altered | NA | NA |

| Rifino [19] | 2020 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Rouyer [43] | 2020 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Roy‐Gash [26] | 2020 | Neurological | Normal | Aphasia, right hemiparesis | 19 |

| Shahjouei [23] | 2020 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Siegler [22] | 2020 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Sugiyama [44] | 2020 | Pulmonary | Normal | No | NA |

| Thompson [18] | 2020 | Neurological | Altered | Dysexecutive syndrome | NA |

| Trimaille [38] | 2020 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tu [39] | 2020 | Pulmonary (n = 1), neurological (n = 1) | Altered (n = 1), normal (n = 1) | Seizures (n = 1) | NA |

| Overall (n = 57) | 16/26 (61.5%) neurological | 23/38 (60.5%) altered | 6/36 (16.7%) no focal signs, 10/36 (27.8%) seizure disorder | 10.3 ± 7.5 |

Abbreviations: NA, not available; NIHSS, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale score.

Undefined seizure semiology.

Computed tomography angiography was the most frequent imaging technique used for diagnostic assessment (30/43, 69.8%; Table 3). Only one patient underwent digital subtraction angiography, showing signs consistent with extensive hemispheric venous congestion [28]. Involvement of multiple venous vessels was more frequent than thrombosis of a single vessel (29 vs. 14/43). The transverse sinus was most frequently affected (65%), followed by the sigmoid sinus (47%), the superior sagittal sinus (44%), and the straight sinus (21%). The deep venous system was involved in 37% of cases, whereas thrombosis in cortical veins was detected in 21% of cases. Hemorrhagic lesions were reported in 42% of cases (Table 3).

Laboratory findings and thrombophilia screening

Regarding coagulation, fibrinogen was abnormal in 54.5% of cases (mean fibrinogen = 490.8 ± 112.9 mg/dl), whereas D‐dimer levels were above threshold in all but two cases [39, 44] (mean = 7812 ± 15,062 ng/ml) (Table S4). C‐reactive protein was elevated in all but two cases [33, 44] (mean = 42.5 ± 54.7 mg/dl), whereas lymphocyte count was only inconsistently reported across studies, with 19/21 cases reporting lymphopenia (90.5%).

Thrombophilia screening results were available for 12 cases [18, 41, 42], 41.7% of which had pathological findings (three with positive lupus anticoagulant, two with anticardiolipin antibodies; Table S4). Cerebrospinal fluid testing for SARS‐CoV‐2 by PCR was negative in all cases where it was available (n = 5/5) [21, 28, 29, 32, 33]. No data were available on opening pressure.

Treatment and prognosis

Nine patients were treated with anticonvulsive medication, in one instance as prophylactic treatment (Table 4) [17]. Anticoagulants were administered to 37 patients (95%); one pediatric patient was treated with antiplatelets [37] and one patient received endovascular treatment (mechanical thrombectomy and local thrombolysis) [28]. Follow‐up imaging was reported in only four cases, at variable time points ranging from 1 to 4 weeks after admission, and showed partial [18, 44] or no recanalization [17, 26].

TABLE 4.

Treatment and outcome of cerebral venous thrombosis cases included

| Author | Year | N | Antiseizure medication | Admitted to ICU | Anticoagulation | Interventional/surgical procedures | mRS at follow‐up | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baudar [27] | 2020 | 1 | No | No | Yes | No | 0 | Full recovery |

| Bolaji [24] | 2020 | 1 | Yes (LEV) | Yes | Yes | No | 3 | Partial recovery |

| Cavalcanti [28] | 2020 | 3 | No | Yes (n = 2) | Yes | Yes (MT + rtPA n = 1; external ventricular drain n = 1) | 6 (all cases) | Death (n = 3) |

| Chougar [29] | 2020 | 1 | Yes (undefined) | Yes | Yes | No | 6 | Death |

| Chow [17] | 2020 | 1 | Yes (LEV) a | No | Yes | No | 4 | Poor recovery |

| Dahl‐Cruz [35] | 2020 | 1 | Yes (LEV) | No | Yes | No | NA | Full recovery |

| Essajee [37] | 2020 | 1 | No | No | No (aspirin) | No | NA | Partial recovery |

| Garaci [32] | 2020 | 1 | No | NA | Yes | No | NA | NA |

| Haroon [41] | 2020 | 1 | No | NA | Yes | No | NA | NA |

| Hemasian [33] | 2020 | 1 | Yes (LEV) | No | Yes | No | NA | Full recovery |

| Hoelscher [21] | 2020 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Poor recovery |

| Hughes [34] | 2020 | 1 | No | No | Yes | No | NA | Full recovery |

| Kananeh [42] | 2020 | 1 | No | NA | Yes | External ventricular drain | 6 | Death |

| Keaney [20] | 2020 | 2 | Yes (LEV, n = 1) | No | NA | No | 6 (n = 2) | Death (n = 2) |

| Klein [25] | 2020 | 1 | Yes (LEV) | No | Yes | No | NA | partial recovery |

| Koh [36] | 2020 | 4 | NA | NA | Yes | No |

6 (n = 1), NA (n = 3) |

Death (n = 1), full recovery (n = 3) |

| Malentacchi [30] | 2020 | 1 | No | Yes | Yes | No | 6 | death |

| Mowla [40] | 2020 | 13 | NA | NA | Yes (n = 13) | Yes (decompressive craniectomy, n = 1) |

6 (n = 3), ≤2 (n = 6) b |

Partial/full recovery (n = 6), death (n = 3) |

| Poillon [31] | 2020 | 2 | No | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Rifino [19] | 2020 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Rouyer [43] | 2020 | 1 | NA | NA | Yes | No | NA | NA |

| Roy‐Gash [26] | 2020 | 1 | YES (LCS) | NO | Yes | Yes (decompressive craniectomy) | 6 | Death c |

| Shahjouei [23] | 2020 | 6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Siegler [22] | 2020 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Sugiyama [44] | 2020 | 1 | No | NA | Yes | No | 0 | Recovery |

| Thompson [18] | 2020 | 1 | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Partial recovery |

| Trimaille [38] | 2020 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tu [39] | 2020 | 2 | Yes (n = 1) | NA | Yes | Yes (decompressive craniectomy, n = 1) |

0 (n = 1), 6 (n = 6) |

Recovery (n = 1), death (n = 1) |

| Overall | 57 | 9/25 (36%) | 5/17 (29.4%) | 37/38 (97.4%) | 7/41 (17.1%) | 21/35 (60%) recovered, 14/35 (40%) died | ||

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; LCS, lacosamide; LEV, levetiracetam; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; MT, mechanical thrombectomy; NA, not available; rtPA, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator.

Prophylactic use.

Data available for nine patients.

Due to recurrent cerebral venous thrombosis with hemorrhage.

In‐hospital mortality was high, as 14/35 patients died (40%). One of them had recurrent contralateral CVT and associated hemorrhage (with persistent left transverse sinus thrombosis) after 2 weeks from the initial CVT [26]. Among them, six had nonhemorrhagic lesions and seven had parenchymal hemorrhage [20, 30, 39, 42]. Parenchymal hemorrhage tended to be more frequent in those not surviving CVT (60% vs. 40%, p = 0.1). Full or partial recovery was reported in 21 cases, nine of which had a full recovery at the last available follow‐up [27, 33, 34, 35, 36, 39, 44].

DISCUSSION

This systematic review including 57 patients disclosed that CVT in the context of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is a rare but life‐threatening complication, which was predominantly seen in patients with mild to moderate COVID‐19 disease. In detail, we determined a frequency of 0.08% among patients hospitalized for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. In addition, CVT represented 4.2% of all cerebrovascular events among patients hospitalized for COVID‐19. These results support a potential higher occurrence rate of CVT in SARS‐CoV‐2 patients, given an expected rate of only 5 to 20 per million per year in the general population [12, 45].

Conditions associated with CVT can be classified as predisposing (e.g., genetic prothrombotic diseases, antiphospholipid syndrome, cancer) or precipitant (oral contraceptives, infections, drugs with prothrombotic action) [46]. In 90% of cases of our cohort, neurological signs and symptoms of CVT developed with or after (1–8 weeks) the emergence of respiratory or systemic symptoms of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Together with the previous knowledge about increased risk of thrombosis in COVID‐19, our findings suggest a potential causality [3, 7, 8, 47, 48]. For the four cases in which CVT diagnosis preceded the onset of COVID‐19–related systemic symptoms, it seems more likely that SARS‐CoV‐2 infection may not have been causal. Defining causality, however, would require population‐based studies with an adequately sized control group [3, 47].

Considering that the pandemic continues, it is necessary to raise awareness for CVT as a potential complication of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. This should be particularly emphasized to curtail missed or delayed diagnosis of a potentially treatable condition such as CVT, which requires specific imaging workup [13]. The diagnosis is complicated by mild and subtle clinical presentations that may be seen as common residual symptoms of COVID‐19 infection, with isolated headache pattern potentially underrecognized, as it is underreported in this review. Thus, a low threshold for diagnostic consideration for CVT and subsequent intracerebral vessel imaging (e.g., computed tomography venography) should be maintained in the acute and subacute phase of COVID‐19 in case of headache, encephalopathy, mental status changes, focal neurological signs, or seizures [11]. Elevated D‐dimer and fibrinogen levels can raise suspicion of CVT but are also commonly observed during the acute phase of systemic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection [49]. Computed tomography venography may be preferred over magnetic resonance imaging given the substantially shorter scan timing and broader availability, which is critical in times of limited hospital resources and risk for spread of infection to hospital personnel [50].

We found a high rate of thrombosis of the cerebral deep venous system (37%) and involvement of multiple sinuses (67%). Despite the limitations due to the quality of the reports, the involvement of deep veins seems more frequent than usual, with the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis reporting rates of deep venous system involvement of as low as 11% [51]. The frequent parenchymal lesions and hemorrhages raise additional interest, and may be related with (i) diagnostic bias toward more severe cases (low level of suspicion, shortage of care, or difficulty in identifying acute neurological symptoms in critical patients), (ii) delayed presentation to emergency departments, or by (iii) a relationship to the potential precipitant factor in terms of systemic inflammation or direct viral involvement. Pathological mechanisms of SARS‐CoV‐2–induced thrombosis have yet to be fully elucidated, but several potential mechanisms have been proposed. Venous thrombosis can result either from systemic inflammation and cytokine storm, from a direct immune‐mediated postinfectious mechanism, or from virus‐induced angiitis [8, 52]. Moreover, COVID‐19–associated coagulopathy may also have contributed to the development of parenchymal hemorrhage.

Mortality was high in patients with CVT and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Whether this is related to the neurological involvement or the severity of COVID‐19 per se remains unclear, as reports considered in this systematic review did not detail the course of events leading to unfavorable outcomes. However, the fact that most of the patients were reported to have mild respiratory symptoms on admission seems supportive of a negative effect of CVT on overall prognosis. Management of CVT in a stroke unit with reserved beds for SARS‐CoV‐2 patients could optimize care and minimize additional complications. Some guidelines suggest early prophylactic low‐molecular‐weight heparin in symptomatic COVID‐19–positive patients. Whether this measure is sufficient to reduce the risk for CVT needs to be explored in future prospective studies [53].

The current review is, to our knowledge, the first and only to systematically address CVT features in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2, and might represent a basis to orient clinical practice and guide future larger studies.

However, limitations have to be clarified. First, the quality of included studies was low, mainly in relation to design and report methodology. Second, few data regarding neuroradiological features were available, which limited the identification of peculiar sites or pattern of thrombosis. Third, meta‐analysis was limited to few studies, with differences in patient selection and potential bias. In this regard, our attempt was to limit the analysis to hospitalized patients, which might represent a more stable denominator than the number of patients testing positive for SARS‐CoV‐2, independently from location. Nevertheless, nation‐based policies, healthcare service organization, and access to diagnostics might have influenced results and contributed to the heterogeneity across studies. Overall, our systematic review provides proof that CVT is worth suspicion among patients with encephalopathy and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

In conclusion, our systematic review raises awareness for CVT in the context of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Prospective studies and analysis of registries are warranted to confirm our findings, to identify further peculiar features of CVT in people infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 and the characteristics of post‐COVID‐19 CVT, and to provide potential insights into the ascertainment and treatment of the underlying thrombophilic state.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Tommaso Baldini: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); funding acquisition (lead); investigation (lead); methodology (lead); project administration (lead); resources (lead); software (lead); supervision (lead); validation (lead); visualization (lead); writing–original draft (equal); writing–review and editing (equal). Gian Maria Asioli: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); funding acquisition (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); resources (equal); software (equal); supervision (equal); validation (equal); visualization (equal); writing–original draft (equal); writing–review and editing (equal). Michele Romoli: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); funding acquisition (lead); investigation (lead); methodology (lead); project administration (lead); resources (equal); software (lead); supervision (lead); validation (lead); visualization (lead); writing–original draft (lead); writing–review and editing (lead). Mariana Carvalho Dias: Conceptualization (supporting); data curation (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); funding acquisition (supporting); investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); project administration (supporting); resources (supporting); software (supporting); supervision (supporting); validation (supporting); visualization (supporting); writing–original draft (supporting); writing–review and editing (equal). Eva Schulte: Conceptualization (supporting); data curation (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); funding acquisition (supporting); investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); project administration (supporting); resources (supporting); software (supporting); supervision (supporting); validation (supporting); visualization (supporting); writing–original draft (supporting); writing–review and editing (equal). Diana Aguiar de Sousa: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (lead); funding acquisition (equal); investigation (lead); methodology (lead); project administration (equal); resources (equal); software (equal); supervision (lead); validation (lead); visualization (equal); writing–original draft (lead); writing–review and editing (lead). Johann Sellner: Conceptualization (supporting); data curation (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); funding acquisition (supporting); investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); project administration (supporting); resources (supporting); software (supporting); supervision (supporting); validation (supporting); visualization (supporting); writing–original draft (supporting); writing–review and editing (equal). Andrea Zini: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); funding acquisition (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); resources (equal); software (equal); supervision (equal); validation (equal); visualization (equal); writing–original draft (lead); writing–review and editing (lead).

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

© Romoli contributed equally to this work.

Diana Aguiar De Sousa, Johann Sellner, and Andrea Zini are senior authors.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data collected for this systematic review will be available upon request from the corresponding author (M.R.).

REFERENCES

- 1. Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;1091:m1091. 10.1136/bmj.m1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sellner J. Of mice and men: COVID‐19 challenges translational neuroscience. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:1762‐1763. 10.1111/ene.14278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Romoli M, Jelcic I, Bernard‐Valnet R, et al. A systematic review of neurological manifestations of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: the devil is hidden in the details. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:1712‐1726. 10.1111/ene.14382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moro E, Priori A, Beghi E, et al. The international European Academy of Neurology survey on neurological symptoms in patients with COVID‐19 infection. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:1727‐1737. 10.1111/ene.14407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poissy J, Goutay J, Caplan M, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID‐19. Circulation. 2020;142:184‐186. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):683. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Varatharaj A, Thomas N, Ellul MA, et al. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID‐19 in 153 patients: a UK‐wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;2:1‐8. 10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30287-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fifi JT, Mocco J. COVID‐19 related stroke in young individuals. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:713‐715. 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30272-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Piazza G, Campia U, Hurwitz S, et al. Registry of arterial and venous thromboembolic complications in patients with COVID‐19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2060‐2072. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khan IH, Savarimuthu S, Leung MST, et al. The need to manage the risk of thromboembolism in COVID‐19 patients. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72:799‐804. 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferro JM, Bousser MG, Canhão P, et al. European Stroke Organization guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis – Endorsed by the European Academy of Neurology. Eur Stroke J. 2017;2:195‐221. 10.1177/2396987317719364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Silvis SM, De Sousa DA, Ferro JM, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:555‐565. 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saposnik G, Barinagarrementeria F, Brown RD, et al. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:1158‐1192. 10.1161/STR.0b013e31820a8364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Romoli M, Paciaroni M, Tsivgoulis G, et al. Mothership versus drip‐and‐ship model for mechanical thrombectomy in acute stroke: a systematic review and meta‐analysis for clinical and radiological outcomes. J Stroke. 2020;22: 10.5853/jos.2020.01767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vidale S, Romoli M, Consoli D, et al. Bridging versus direct mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke: a subgroup pooled meta‐analysis for time of intervention, eligibility, and study design. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;49(2):223‐232. 10.1159/000507844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539‐1558. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chow LC, Chew LP, Leong TS, et al. Thrombosis and bleeding as presentation of COVID‐19 infection with polycythemia vera. A case report. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;2(11):2406‐2410. 10.1007/s42399-020-00537-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thompson A, Morgan C, Smith P, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis associated with COVID‐19. Pract Neurol. 10.1136/practneurol-2020-002678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rifino N, Censori B, Agazzi E, et al. Neurologic manifestations in 1760 COVID‐19 patients admitted to Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital, Bergamo, Italy. J Neurol. 2020. 10.1007/s00415-020-10251-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Keaney K, Mumtaz T. Cerebral venous thrombosis in patients with severe COVID‐19 infection in intensive care. Br J Hosp Med. 2020;81:1‐4. 10.12968/hmed.2020.0327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hoelscher C, Sweid A, Ghosh R, et al. Cerebral deep venous thrombosis and COVID‐19: case report. J Neurosurg. 2020;9:1‐4. 10.3171/2020.5.JNS201542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Siegler JE, Cardona P, Arenillas JF, et al. Cerebrovascular events and outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19: The SVIN COVID‐19 Multinational Registry. Int J stroke Off J Int Stroke Soc. 2020;1747493020959216: 10.1177/1747493020959216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shahjouei S, Naderi S, Li J, et al. Risk of stroke in hospitalized SARS‐CoV‐2 infected patients: a multinational study. EBioMedicine. 2020;59:102939. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bolaji P, Kukoyi B, Ahmad N, et al. Extensive cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a potential complication in a patient with COVID‐19 disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:e236820. 10.1136/bcr-2020-236820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klein DE, Libman R, Kirsch C, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis: a typical presentation of COVID‐19 in the young. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29:104989. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roy‐Gash F, Marine DM, Jean‐Michel D, et al. COVID‐19‐associated acute cerebral venous thrombosis: clinical, CT, MRI and EEG features. Crit Care. 2020;24:1‐3. 10.1186/s13054-020-03131-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Baudar C, Duprez T, Kassab A, et al. COVID‐19 as triggering co‐factor for cortical cerebral venous thrombosis? J Neuroradiol. 2020. 10.1016/j.neurad.2020.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cavalcanti DD, Raz E, Shapiro M, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis associated with COVID‐19. Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41:1370–1376. 10.3174/AJNR.A6644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chougar L, Mathon B, Weiss N, et al. Atypical deep cerebral vein thrombosis with hemorrhagic venous infarction in a patient positive for COVID‐19. Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41:1‐3. 10.3174/ajnr.a6642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Malentacchi M, Gned D, Angelino V, et al. Concomitant brain arterial and venous thrombosis in a COVID‐19 patient. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:e38‐e39. 10.1111/ene.14380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Poillon G, Obadia M, Perrin M, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis associated with COVID‐19 infection: Causality or coincidence? J Neuroradiol. 2020. 10.1016/j.neurad.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Garaci F, Di Giuliano F, Picchi E, et al. Venous cerebral thrombosis in COVID‐19 patient. J Neurol Sci. 2020;414:116871. 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hemasian H, Ansari B. First case of Covid‐19 presented with cerebral venous thrombosis: a rare and dreaded case. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2020;176:521‐523. 10.1016/j.neurol.2020.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hughes C, Nichols T, Pike M, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis as a presentation of COVID‐19. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7:1691. 10.12890/2020_001691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dahl‐Cruz F, Guevara‐Dalrymple N, López‐Hernández N. Cerebral venous thrombosis and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Rev Neurol. 2020;70:391‐392. 10.33588/rn.7010.2020204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Koh JS, De Silva DA, Quek AML, et al. Neurology of COVID‐19 in Singapore. J Neurol Sci. 2020;418:117118. 10.1016/j.jns.2020.117118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Essajee F, Solomons R, Goussard P, et al. Child with tuberculous meningitis and COVID‐19 coinfection complicated by extensive cerebral sinus venous thrombosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:e238597. 10.1136/bcr-2020-238597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Trimaille A, Curtiaud A, Marchandot B, et al. Venous thromboembolism in non‐critically ill patients with COVID‐19 infection. Thromb Res. 2020;193:166‐169. 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.07.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tu TM, Goh C, Tan YK, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis in patients with COVID‐19 infection: a case series and systematic review. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29:1‐9. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mowla A, Shakibajahromi B, Shahjouei S, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis associated with SARS‐CoV‐2; a multinational case series. J Neurol Sci. 2020;419:117183. 10.1016/j.jns.2020.117183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Haroon KH, Muhammad A, Hussain S, et al. COVID‐19 related cerebrovascular thromboembolic complications in three young patients. Case Rep Neurol. 2021;12(3):321‐328. 10.1159/000511179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kananeh MF, Thomas T, Sharma K, et al. Arterial and venous strokes in the setting of COVID‐19. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;79:60‐66. 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rouyer O, Pierre‐Paul I‐N, Balde A, et al. High prevalence of deep venous thrombosis in non‐severe COVID‐19 patients hospitalized for a neurovascular disease. medRxiv. 2020;10:174‐180. 10.1159/000513295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sugiyama Y, Tsuchiya T, Tanaka R, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis in COVID‐19‐associated coagulopathy: a case report. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;79:30‐32. 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.07.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Otite FO, Patel S, Sharma R, et al. Trends in incidence and epidemiologic characteristics of cerebral venous thrombosis in the United States. Neurology. 2020;95:e2200‐e2213. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ferro JM, Aguiar de Sousa D. Cerebral venous thrombosis: an update. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2019;19:74. 10.1007/s11910-019-0988-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ellul M, Varatharaj A, Nicholson TR, et al. Defining causality in COVID‐19 and neurological disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91:811‐812. 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ellul MA, Benjamin L, Singh B, et al. Neurological associations of COVID‐19. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:767‐783. 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30221-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Quintana‐Díaz M, Andrés‐Esteban EM, Ramírez‐Cervantes KL, et al. Coagulation parameters: an efficient measure for predicting the prognosis and clinical management of patients with COVID‐19. J Clin Med. 2020;9:3482. 10.3390/jcm9113482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zini A, Romoli M, Gentile M, et al. The stroke mothership model survived during COVID‐19 era: an observational single‐center study in Emilia‐Romagna. Italy. Neurol Sci. 2020;41:3395‐3399. 10.1007/s10072-020-04754-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ferro JM, Canhão P, Stam J, et al. Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the international study on cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke. 2004;35:664‐670. 10.1161/01.STR.0000117571.76197.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID‐19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417‐1418. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. National Institutes of Health N, COVID‐19 Treatment Guidelines Panel N . COVID‐19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) Treatment Guidelines; 2020. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

Data collected for this systematic review will be available upon request from the corresponding author (M.R.).