Abstract

The narrow pH range of Fenton oxidation restricts its applicability in water pollution treatment. In this work, a CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite was synthesized via a stepwise thermal polymerization method using melamine, citric acid, and Cu2O. Adding H2O2 to form a heterogeneous Fenton system can degrade Rhodamine B (Rh B) under dark conditions. The synthesized composite was characterized by Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction (XRD), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms. The results showed that CDs, Cu2O, and CuO were successfully loaded on the surface of g-C3N4. By evaluating the catalytic activity on Rh B degradation in the presence of H2O2, the optimal contents of citric acid and Cu2O were 3 and 2.8%, respectively. In contrast to a typical Fenton reaction, which is favored in acidic conditions, the catalytic degradation of Rh B showed a strong pH-dependent relation when the pH is raised from 3 to 11, with the removal from 45 to 96%. Moreover, the recyclability of the composite was evaluated by the removal ratio of Rhodamine B (Rh B) after each cycle. Interestingly, recyclability is also favored in alkaline conditions and shows the best performance at pH 10, with the removal ratio of Rh B kept at 95% even after eight cycles. Through free radical trapping experiments and electron spin resonance (ESR) analysis, the hydroxyl radical (•OH) and the superoxide radical (•O2–) were identified as the main reactive species. Overall, a mechanism is proposed, explaining that the higher catalytic performance in the basic solution is due to the dominating surface reaction and favored in alkaline conditions.

1. Introduction

Organic pollutants produced by the dye industry are harmful to the environment and human beings due to their high toxicity, persistence, and poor biodegradability.1,2 The key to advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) is the in situ-produced hydroxyl radical (•OH) with relatively high reactivity and nonselectivity for different organic pollutants.3,4 As one of the most efficient treatments for such organic pollutants, an AOP can mineralize almost all organic pollutants, which can be completely degraded into water, carbon dioxide, and some easily degradable inorganic ions in wastewater without causing secondary pollution.5−7 Like a typical AOP, a Fenton reaction can produce more number of •OH when the ferrous ions react with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).8 Some disadvantages of the Fenton reaction are a narrow pH range (pH < 4), the formation of iron sludge, and the high cost of catalyst recovery.9−11

Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4), a nonmetallic semiconductor, has a wide range of applications due to the narrow band gap (2.7 eV), low cost, nontoxicity, good chemical stability, and superior resistance to acids and alkalis.12,13 However, some shortcomings, such as a high photoexciting electron–hole recombination, low specific surface area, and low utilization rate,14,15 limit the application of g-C3N4 in the field of photocatalysts. Therefore, many strategies, such as changing the morphology,16 nonmetal or metal and metal oxide loading,17−19 construction of heterojunctions, etc.,20,21 have been employed to improve its photocatalytic performance. Among these strategies, the use of carbon nanodots (CDs) to modify g-C3N4 not only increased the specific surface area of pure g-C3N4 but also improved its photocatalytic activity and promoted photocatalytic H2 production.22

On this basis, several studies have been conducted by introducing a third compound (e.g., TiO2, Ag3PO4, Ag nanoparticles, etc.) into CDs/g-C3N4 to further improve the photocatalytic performance on H2 production or pollutant degradation.23−25 Besides improving the photocatalytic performance, the CDs/g-C3N4 composite may also act as a Fenton-like catalyst and catalyze the decomposition of H2O2 to form •OH in the light-shielding condition according to its intrinsic property, which has been used to remove organic pollutants.26 Recent studies have shown that in some pollutants, the introduction of a metal oxide into the CDs/g-C3N4 matrix may improve the degradation efficiency, such as loading ZnO on the surface of CDs/g-C3N4 to prepare a CDs/g-C3N4/ZnO nanocomposite for tetracycline total degradation.27

Similar to the redox properties of iron, copper can undergo a Fenton-like system with H2O2 to achieve mutual conversion between Cu+ and Cu2+ and produce •OH, as shown in eqs 1 and 2.28,29 It should be noted that eq 2 is a rate-limiting step and Cu2+ can be from a copper complex [Cu(H2O)6]+ at a neutral pH, which can be used in the Cu2+/Cu+/H2O2 Fenton-like system.30 Cu+/Cu2+ has limited applicability due to the narrow range of pH and the extreme volatility of Cu+. Therefore, to expand the application of CDs/g-C3N4 and overcome some limitations of the Fenton system and the Cu+/Cu2+ Fenton-like system, this study chose to load Cu2O on CDs/g-C3N4 and form a Fenton-like system for the degradation of Rh B in the reaction.

| 1 |

| 2 |

In this study, a more promising strategy is proposed to fix Cu2O on CDs/g-C3N4 by thermal polymerization, in which CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composites are obtained that can initiate a Fenton-like reaction in the presence of H2O2 to generate active free radicals that are used for the degradation of organic pollution. The prepared composites were characterized by FT-IR, XRD, TEM, XPS, and BET techniques. The optimal synthesis and experiment conditions, including CDs content, Cu2O content, H2O2 concentration, solution ion reaction, and influence of different pH values, were explored. Also, to further explore the reasons for the differences in the changes at different pH conditions, the changes in the dissolved oxygen, total copper content, and the stability of composites at different pH values were studied. Besides, reactive oxygen species (ROS) were investigated by ESR analysis and free radical capture experiments. Based on the above results, the degradation mechanism of Rh B was outlined in the presence of H2O2 with the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite in a wide range of pH conditions.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of Catalysts

2.1.1. FT-IR

The as-prepared composites, labeled as g-C3N4, CD3/g-C3N4, and CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO, were investigated to distinguish the functional groups via the FT-IR spectrum. As presented in Figure S1, the characteristic peaks of g-C3N4 were observed at 1200–1645 cm–1, corresponding to the stretching vibration modes of CN-bond heterocycles (C=N and C–N groups).31 The appearance of the absorption peak at 810 cm–1 was allocated to the normal vibration of the tris(3′,5′-dimethylpyrazol-1-yl)-s-triazine structure.32 The aforementioned absorption peaks could be characterized as g-C3N4, similar to a previous study.33 Further, a broadband emerged approximately at 3200 cm–1, which can be allocated to the stretching vibration modes of NH and NH2 group.34 For CD3/g-C3N4 and CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO, similar peaks were present, showing that the skeletal structure of g-C3N4 was not damaged in these composites. With Cu2O doped into CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO, the corresponding peak of the stretching vibration of the Cu–O bond of Cu2O and CuO was not detected in FT-IR, implying that the corresponding copper-based functional groups were not formed by thermal polymerization of the synthesized composites.35,36

2.1.2. XRD

The crystal structures of Cu2O, g-C3N4, CD3/g-C3N4, and CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO were acquired via XRD patterns, as shown in Figure S2. For g-C3N4, the weak peak close to 13.0° can be indexed to (100) diffraction planes, corresponding to the in-planar structural packing motif of tri-s-triazine units. In addition, the strong diffraction peak at 27.5° corresponding to the typical (002) plane was due to the interlayer accumulation of the conjugated aromatic system.37 Besides the characteristic peaks of g-C3N4, with the loading of CDs, the sharp peak of CDs could be detected at 25.25°.38 After doping with Cu2O, the characteristic peaks of g-C3N4 appeared similar, but three diffraction peaks were observed at 36°, 38°, and 61.5° in CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite, which were in good agreement with the crystalline structure of CuO indexed with the standard (111̅) plane, the (111) plane, and corresponding to the (220) plane of the Cu2O phase,39,40 respectively. However, compared to g-C3N4 and CD3/g-C3N4, the (100) plane of the diffraction peaks weakened noticeably, the peak corresponding to the (002) plane shifted slightly, and no diffraction peak arose from the CDs in the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite as Cu2O addition may affect the thermal condensation of melamine, resulting in lower crystallinity of the (100) and (002) crystal planes. Moreover, the invisible diffraction peak of CDs may be due to the relatively low diffraction intensity in the composite.38 Therefore, the XRD spectral patterns revealed the coexistence of CuO and Cu2O in the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite.

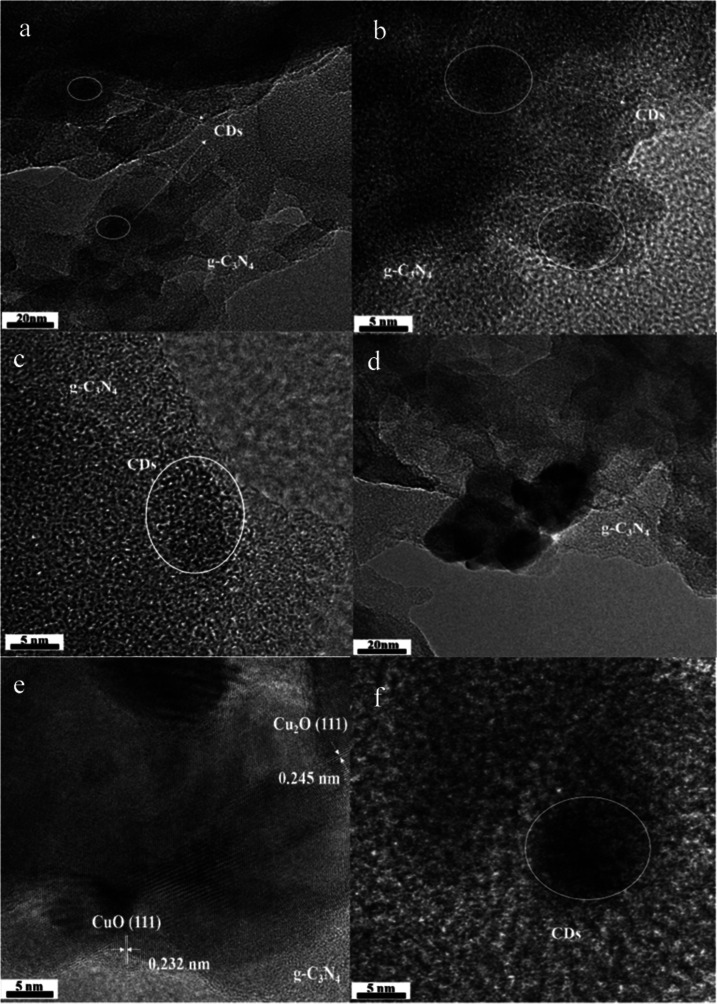

2.1.3. TEM

The morphology and microstructures of CD3/g-C3N4 and CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO samples were observed by TEM and HRTEM. Figure 1a–c shows that the appearance of the CDs is unevenly embedded in the g-C3N4 matrix (white circles), with a diameter of 10–20 nm. This observation was in concordance with the findings of a previous study.41,42 It indicates that CD3/g-C3N4 was successfully prepared by the thermal polymerization method. Figure 1d shows the TEM images of the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite and some particles (20–50 nm) fixed on the two-dimensional lamellar structures of g-C3N4. As shown by the corresponding HRTEM image in Figure 1e, lattice fringes with interlayer distance were measured to be 0.245 and 0.232 nm, which correspond to the (111) plane of Cu2O and the (111) plane of CuO.43,44 XRD results showed Cu2O and CuO in the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO. CDs particles were found on the surface of the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite with the same diameter as CDs in CD3/g-C3N4 (Figure 1c,f). A comparison between the TEM and HRTEM of CD3/g-C3N4 and CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO established that CDs and Cu2O are successfully loaded on the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO surface.

Figure 1.

TEM and HRTEM images of CD3/g-C3N4 (a–c) and CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO (d–f).

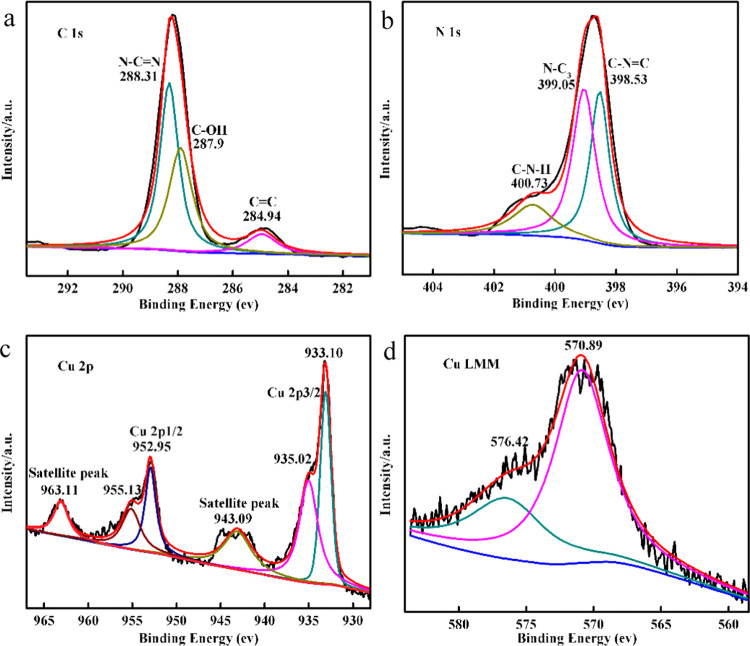

2.1.4. XPS

The elemental and surface chemical states of the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite were investigated via XPS spectral analysis. Only C, N, O, and Cu were present in the composite, and the atomic content ratios were 41.64, 52.28, 3.98, and 2.1%, respectively (Figure S3). Compared with the standard XPS binding energy table, the binding energy peaks of the four elements get slightly shifted toward the higher values.19

The results are shown in Figure 2 and Table S1. Figure 2a shows the high-resolution XPS spectrum of C 1s with peaks at 284.94 and 288.31 eV allocated to C–C and N–C=N, respectively. The peak at 287.90 eV was identified as C–OH, indicating the successful loading of CDs on the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite.32 The N 1s spectrum displayed in Figure 2b mainly shows three peaks at 398.53, 399.05, and 400.73 eV, which are located at the triazine rings (C–N=C), the sp3-hybridized nitrogen (N–C3), and amino groups (C–N–H),34 respectively. This indicates that the structure of g-C3N4 is not completely altered by the addition of CDs and Cu2O. For the O 1s spectrum (Figure S4), it contains three peaks, corresponding to 530.57 eV (O=C), 532.04 eV (C–OH), and 533.21 eV (adsorbed water).32Figure 2c displays that there are six characteristic peaks in Cu 2p; the binding energies at 933.10 and 952.95 eV were assigned to Cu 2p3/2 and Cu 2p1/2 of Cu+ and those at 935.02 and 955.13 eV were identified as Cu 2p3/2 and Cu 2p1/2 of Cu2+,45,46 respectively. The deconvoluted peaks at 943.09 and 963.11 eV, derived from the satellite peaks of Cu2+, established the existence of Cu2+ in the composite.45

Figure 2.

High-resolution (a) C 1s, (b) N 1s, (c) Cu 2p, and (d) Cu LMM spectra of the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite.

Since the binding energies of Cu+ and Cu0 are very close, they are hard to distinguish unless the Cu LMM peak is observed (Figure 2d). The Cu LMM peaks of the composite were observed at 570.89 and 576.42 eV, which was in accordance with the presence of Cu+.36 To conclude, the Cu 2p and Cu LMM peaks showed the existence of both Cu+ and Cu2+ ions in the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite, showing conformity with the results of XRD and TEM. These findings show the successful synthesis of the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite.

2.1.5. N2 Adsorption/Desorption Isotherms

The specific surface area and pore-size distribution curves of as-prepared g-C3N4, CD3/g-C3N4, and CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO samples were analyzed by BET. As presented in Figure S5, g-C3N4, CD3/g-C3N4, and CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO exhibit a typical type IV isotherm with a clear H3 hysteresis loop, suggesting the presence of a mesoporous structure with 2–8 nm pore size.47 The specific surface areas calculated using the BET method were 12.0 ± 0.7, 21.5 ± 1.2, and 90.3 ± 0.5 m2 g–1 for g-C3N4, CD3/g-C3N4, and CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO, respectively, indicating that the mixing with CDs and Cu2O increases the specific surface area of the g-C3N4. The specific surface areas of CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO were 7.53 times and 4.2 times that of pure g-C3N4 and CD3/g-C3N4, respectively. This suggests that the addition of CDs and Cu2O increases the specific surface area of the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite and the contact area of the reactant and provides more active sites.

2.2. Evaluation of the Catalytic Performance of CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO Composites

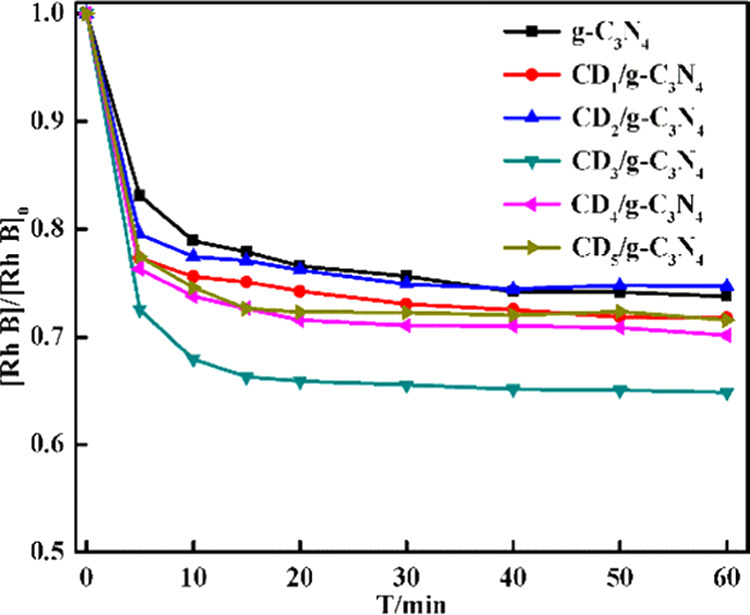

2.2.1. Content of CDs

To determine the optimal content of CDs in the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite, the catalytic performance on the removal of Rh B in the presence of H2O2 and several CDy/g-C3N4 composites with varied contents (1–6%) of CDs was compared. As demonstrated in Figure 3, only 22% of Rh B was removed in 60 min with pure g-C3N4, although the removal rate increased dramatically by raising the content of CDs, reaching its maximum when the CD content was 3. The increase in the removal rate could be ascribed to the fact that the higher amount of CDs might aggregate to form clusters and affect the progress of surface reactions.48 Therefore, the content of optimal CDs was confirmed as y = 3, and CD3/g-C3N4 was selected as the typical composite for further synthesis of CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composites.

Figure 3.

[Rh B]/[Rh B]0 as a function of time in the presence of 5 g/L CDy/g-C3N4 (y = 0–5) with the initial concentration of [H2O2]0 = 5 mM, [Rh B]0 = 0.064 mM, and V = 100 mL.

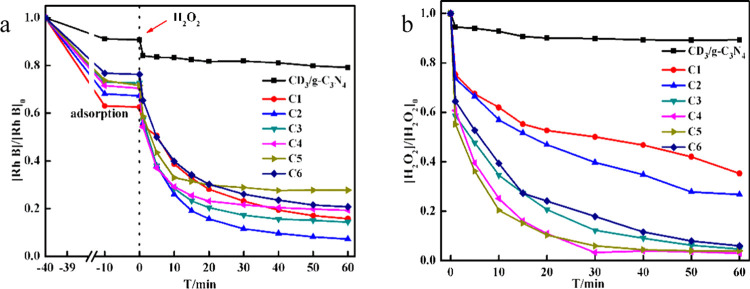

2.2.2. Effect of Cu2O Content

The effect of Cu2O content was studied by evaluating the removal rates of Rh B with CD3/g-C3N4/CuxO composites marked as C1–C6 in the presence of H2O2. The removal of Rh B was remarkably improved by adding Cu2O before and after the injection of H2O2 (Figure 4a), suggesting that the addition of Cu2O improves both the adsorption and catalytic performance of the composite. However, the final removal ratio of Rh B was not linearly related to the content of Cu2O. To be specific, the highest ratio for the adsorption phase and the catalytic degradation phase, during the whole process, responded to C1 and C2, respectively. The H2O2 concentration was also monitored (Figure 4b). The results showed that the decomposition of H2O2 was also enhanced by raising the amount of Cu2O, reaching the highest rate at C4. Notably, at C2, Rh B was degraded completely, with only 73.3% of H2O2 consumed and exhibited the highest utilization rate, as shown by eq 4. Therefore, the C2 composite was selected for further exploration in subsequent experiments. (C2 was taken as the optimal catalyst for property study. The CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite in the following text refers to C2 unless otherwise stated.)

Figure 4.

(a) [Rh B]/[Rh B]0 and (b) [H2O2]/[H2O2]0 as a function of time in the presence of 2 g/L from C1 to C6 with an initial concentration of [H2O2]0 = 5 mM, [Rh B]0 = 0.064 mM, and V = 100 mL.

2.2.3. Effect of H2O2 concentration

H2O2, as a precursor of •OH, was employed to induce Rh B degradation in the presence of the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite after the system reached the adsorption/desorption equilibrium. To evaluate the effect of H2O2, different concentrations of H2O2 were added. When the H2O2 concentration increased from 1 to 10 mM, the degradation rate of Rh B also increased (Figure S6). The degradation rate and utilization of Rh B (calculated from eq 4) with different concentrations of H2O2 are compared in Table S2 (t = 60 min). The higher concentrations of H2O2 induced a higher degradation ratio of Rh B. However, the general trend of the utilization rate of H2O2 decreased with an increase in the concentration of H2O2 as a very high H2O2 concentration was more prone to H2O2 decomposition, suggesting that more H2O2 concentration could lead to higher production of •OH and that in the side reaction H2O2 could be consumed by the formed •OH.49,50 Thus, the H2O2 at 5 mM utilization rate was relatively high, and the degradation rate of Rh B was also in the middle. Therefore, considering its degradation rate and utilization together, the optimal concentration of H2O2 was selected as 5 mM in other experiments.

2.2.4. Effect of Solution Reaction

To verify the potential homogeneous reaction in the system, a similar experiment was conducted by taking several samples at selected time points, filtering separately, and placing them together to observe the time-resolved concentration of Rh B in the filtrate.51 The results are summarized in Figure S7a. In contrast to the original heterogeneous reaction, only a slight decrease was observed in all filtrates, indicating a weaker solution reaction as compared to the surface reaction. The concentrations of Rh B and H2O2 in the filtrates were monitored from 1 min to several days. Figure S7b shows that Rh B was decomposed completely although at a much lower rate than that of the original heterogeneous system. Therefore, in subsequent experiments, the solution reaction was insignificant.

2.2.5. Effect of pH

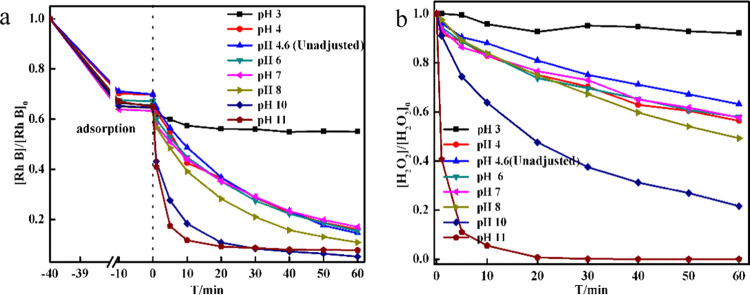

2.2.5.1. Degradation of Rh B and Decomposition of H2O2 under Different pH Conditions

The strict pH limitation (pH < 4) is a major disadvantage of various homogeneous Fenton reactions, preventing its application in neutral and alkaline conditions. Therefore, the study of the pH effect in the present system is very important. In the current study, several experiments were conducted by varying the solution pH from 3 to 11 to evaluate the pH effect on the degradation of Rh B and decomposition of H2O2. Initially, the Rh B solution was adjusted to different pH conditions and was scanned with an ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometer (Figure S8) to nullify the effect of pH on the maximum absorption peak. It was observed that the maximum absorption peak of Rh B can be maintained at 555 nm with the given pH ranges.

To further explore the effect of pH on the Fenton-like reaction and to compare the catalytic degradation of Rh B with CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composites, several different pH conditions were selected. The pH change showed a negligible effect on the adsorption phase (Figure 5a), while during the catalytic degradation phase, the degradation rate of Rh B exhibited a highly basic-favored trend. At pH 10 and 11, the removal rate was significantly higher than that at pH 3. H2O2 concentration in the catalytic degradation phase was also monitored (Figure 5b). Despite the similar degradation rate of Rh B at pH 10 and 11 (Figure 5a), the decomposition rate of H2O2 was much lower at pH 10 than that at pH 11. As discussed in the previous section, pH 10 showed better utilization efficiency. Therefore, the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite can be widely used in the application range of pH.

Figure 5.

(a) [Rh B]/[Rh B]0 as a function of time in the presence of 2 g/L CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite at different pH values with the initial concentration of [H2O2]0 = 5 mM, [Rh B]0 = 0.064 mM, and V = 100 mL. (b) Amount of H2O2 consumed by the catalysts in the degradation of Rh B at different pH values.

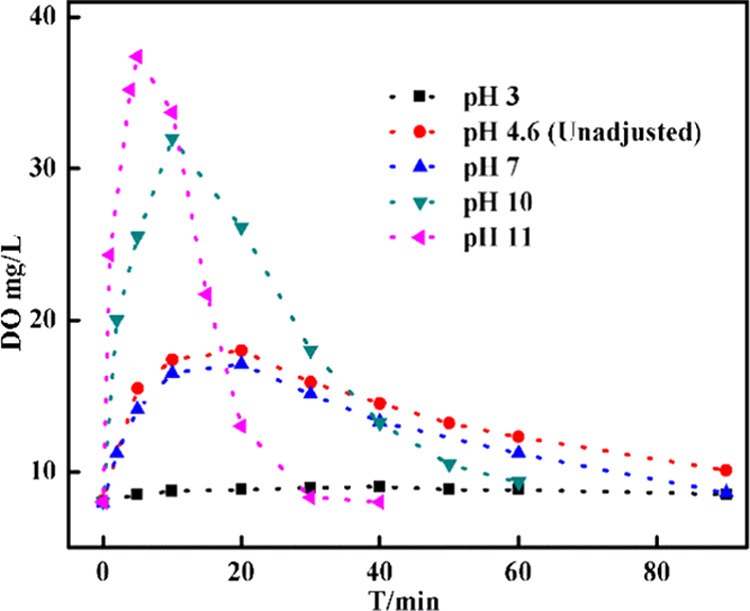

2.2.5.2. Dissolved Oxygen Changes in Solution

To further understand how the decomposition of H2O2 is affected by the change in pH since the decomposition of H2O2 results in H2O and O2, the dissolved oxygen could be used as a probe to study the effect of pH.52Figure 6 depicts a similar trend in the concentration of Dissolved Oxygen (DO), reaches a maximum and then decreases. The maximum was obtained earlier with higher pH. The reason can be explained as follows: the experiment was carried out in the air, and according to Henry’s law, the initial concentration of dissolved oxygen is 8 mg/L, and the observed increase in dissolved oxygen concentration is attributed to oxygen formation in the solution being faster than the equilibration with the surrounding gas phase. As the reaction (H2O2 → 1/2O2+H2O) continues, the formation rate of O2 increases sharply and is dependent on the pH.53 With the consumption of H2O2, the formation of O2 also slows down; thus, the peak appears. Such a trend and pH dependence are in line with the results in Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Change in dissolved oxygen in the presence of 2 g/L CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO with time under different pH conditions with the initial concentration of [H2O2]0 = 10 mM, [Rh B]0 = 0.064 mM, and V = 100 mL.

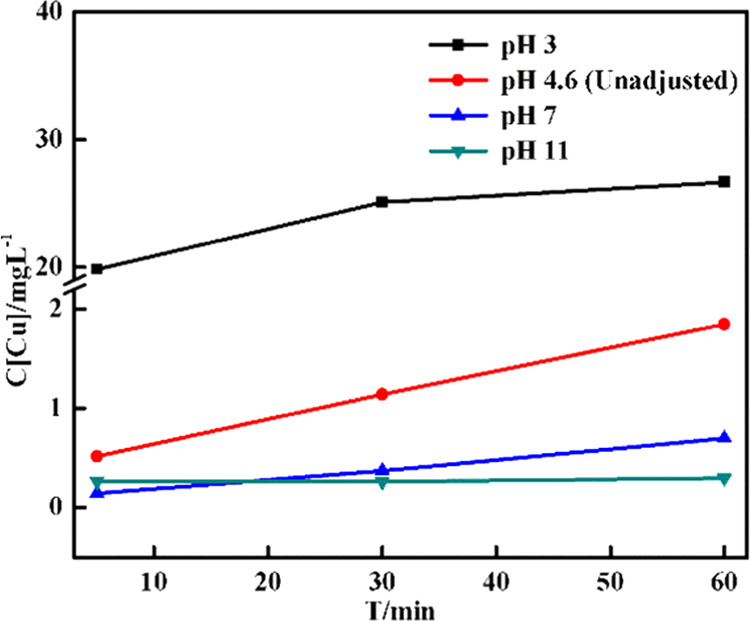

2.2.5.3. Ion Leaching under Different pH Conditions

According to several studies, the leaching of copper ions from the present heterogeneous system may be affected by pH.54,55 The concentration of dissolved Cu species was measured by inductively coupled plasma (ICP) spectrometry in the presence of a typical heterogeneous system (Figure 7). It can be seen that higher pH inhibits Cu leaching; the maximum concentration at pH 3 was about 60 times that at pH 11. According to the Eh-pH diagram of Cu-H2O,29,56,57 it mainly exists in the form of Cu2+ or Cu+, and Cu2O and Cu(OH)2 under acidic and alkali conditions, respectively. It was observed that the leaching of copper ions on the catalyst surface was promoted under acidic conditions; it had a certain inhibitory effect on the leaching of ions on the catalyst surface under alkaline conditions, thereby indicating that the surface reaction of the composite was dominant in the reaction.

Figure 7.

Change in the total copper ion concentration in the presence of 2 g/L CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO with time under different pH conditions with the initial concentration of [H2O2]0 = 5 mM, [Rh B]0 = 0.064 mM, and V = 100 mL.

2.2.5.4. Recycling Experiment

To verify the recyclability and stability of the prepared CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite, three sets of recycling experiments were explored. In the wet cycle, the number of composites remains unchanged, and Rh B and H2O2 were directly added after the reaction. In the dry cycle, a series of centrifugation, washing, and drying treatments were used on the composites after the reaction for the next cycle reaction. The composites were recycled via a wet or dry process, and the pH was fixed at 11, 4.6, and 10.

2.2.5.4.1 Recycling via the Wet Process at pH 11 The first set was performed at pH 11 via a wet recycling process since the original degradation rate of Rh B is relatively high. The concentrations of both H2O2 and Rh B against reaction time were investigated during each cycle (Figure S9). The decomposition rate of H2O2 slightly declined after 12 continuous cycles, while the degradation ratio of Rh B declined dramatically from 88.8 to 67.5% (Figure S9a). Then, Rh B was cyclically degraded under the same conditions (Figure S9b). The time interval was 30 min, and Rh B and H2O2 were added at the end of each cycle. It was noticed that although Rh B can be efficiently degraded by the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composites, the degradation efficiency is reduced after 10 cycles with incomplete degradation. The H2O2 concentration was adjusted from 5 to 10 mM under pH 11, and H2O2 showed rapid decomposition completely (Figure S10). In addition to the influence of method error and the side reaction at pH 11, it was observed that the degradation residues cover the surface of the composites for the wet cycle, thereby affecting the progress of the reaction.

2.2.5.4.2. Recycling via the Dry Process at pH 4.6 (Unadjusted pH) To reduce the impact of pH adjustment, under unadjusted pH (as the catalytic degradation performance is not lower than that under some pH conditions), a dry method was used to evaluate the circulation performance of CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO. As shown in Figure S11, the degradation of Rh B and the consumption of H2O2 are significantly affected by the number of cycles, and both experience a significant decrease. This indicates that the dry process has a greater impact on the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite. At pH 4.6, the copper on the surface of the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite mainly exists in the form of ions on the solution and causes loss of copper on the surface of the composite during the dry process.

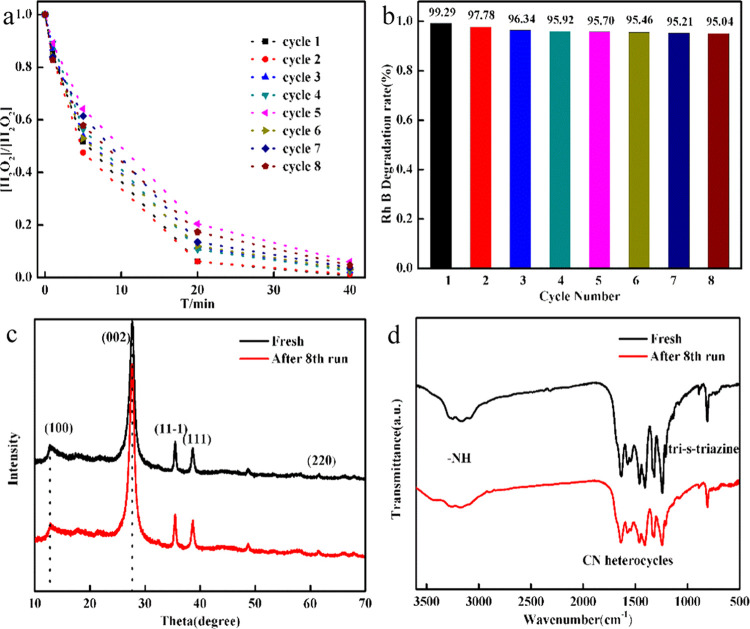

2.2.5.4.3. Recycling via the Dry Process at pH 10 Conditions After optimizing the conditions, combined with the influence of pH 10, the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite has a higher degradation efficiency for Rh B, so the dry method is also used to study the circulation performance of CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO. After eight cycles, the degradation efficiency of the composite on Rh B could be reduced by 4%, and the degradation ratio reached more than 95% in each cycle (Figure 8b). At the same time, the H2O2 consumed in each cycle was tested, and it almost completely decomposed after eight cycles, as shown in Figure 8a. This is because at pH 10, the copper on the surface of the composite mainly exists in the form of Cu2O and Cu(OH)2, and the loss of copper ions during the dry process can be overlooked. This observation agrees with the previous results regarding the ion leaching shown in Figure 7.

Figure 8.

(a) Cyclic degradation of Rh B consumed and the change of H2O2 with 2 g/L CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite in the presence of 10 mM H2O2 at pH 10. (b) Cycling runs for the catalytic degradation of Rh B (0.064 mM) with 2 g/L CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite in the presence of 10 mM H2O2 at pH 10. (c) XRD patterns and (d) FT-IR spectra of the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO sample before and after the cycling catalytic experiments.

Therefore, it can be concluded that the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite has good stability and strong catalytic performance at pH 10. To further establish the stability of the material, the XRD and FT-IR spectral patterns of the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite were studied before and after the 8th reaction cycle (Figure 8c,d). No noticeable changes were seen after the reaction in the structure and elemental groups of CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO.

A comparison with the previous studies was made in terms of cycle stability and pH range to validate the catalytic performance of the prepared CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite. Better cycle stability and a wider range of pH applications were observed for the prepared composites (Table S3).58−61 Therefore, the above findings show outstanding activity and reusability of the as-prepared CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO.

2.2.6. Degradation Mechanism

To determine the mechanism of Rh B degradation by the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite at different pH conditions, radical trapping experiments and ESR analyses were designed and the main active species generated by Rh B degradation were identified.

2.2.6.1. Radical Trapping

Several studies have shown that P-benzoquinone (BQ) and isopropanol (IPA) are often used as scavengers for •OH and •O2– because they can quickly trap free radicals (Table S4) and have a high reaction rate constant.51,53,62 In particular, p-benzoquinone (BQ) was used as a scavenger for superoxide (•O2–) and hydroxyl radicals (•OH); isopropanol (IPA) may react with only •OH.63 Additionally, pure N2 purging was employed to investigate the effect of dissolved oxygen in the reaction. The degradation rate of Rh B retarded after the addition of IPA (10 mM) and BQ (10 mM), but it got suppressed more significantly with the addition of BQ since BQ can trap both •OH and •O2–, while IPA only traps •OH (Figure S12a). Moreover, the inhibition effect of IPA increases as its concentration increases. By comparing the results with and without N2, it was observed that Rh B degradation is affected by the presence of O2.

To determine the inhibition effect of the scavengers more clearly, the reaction parameters were fitted to a pseudo-first-order kinetic model, and the corresponding parameters are shown in Figure S12c (where k represents the reaction rate). It can be seen that the reaction is significantly inhibited after adding the scavengers and introducing N2, and the fitting results are consistent with the results shown in Figure S12a. The results indicate that •OH and •O2– are the main oxidation species in the reaction process,64 and O2 has a certain positive effect on the reaction. However, neither scavenger nor O2 affected the H2O2 decomposition (Figure S12b).

To further determine the effect of pH on the generation of free radicals, free radical capture experiments were carried out under the conditions of pH 4.6 and 10 (Figure S12d). As can be seen, BQ shows a better inhibition effect than that of IPA at a given pH, which means that •O2– is more significant than •OH on the degradation of Rh B or the production of •O2– is higher than •OH. Moreover, by comparing the data after the addition of IPA or BQ with the blank at a certain pH, it is clear that the inhibition effect is also basic-favored.

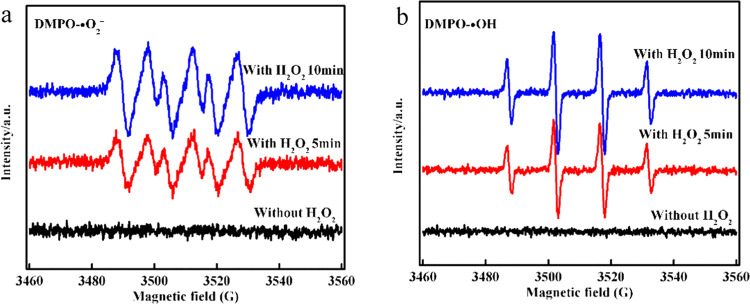

The EPR experiment was conducted to further identify the existence of •OH and •O2–, radicals formed during the reaction of the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite. The spin-trapping DMPO (5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide) (100 mM) is a persistent radical scavenger to trap other radicals, such as DMPO-•O2– or DMPO-•OH, which are spin adducts with characteristic EPR signals. The EPR signal was not clearly observed without the H2O2 condition (Figure 9a), whereas it clearly revealed a four-line spectrum with the relative intensities of 1:1:1:1 with H2O2, a characteristic signal of the DMPO-•O2– adduct.65 Besides, the EPR spectra featuring the characteristic 1:2:2:1 quartet indicated successful trapping of •OH by DMPO with H2O2 in the Rh B degradation experiment as depicted in Figure 9b.32 Further, no EPR signal of spin adduct DMPO-•OH was observed without H2O2. The results are consistent with those of the trapping experiments. Hence, we further verified the dominant role of •OH and •O2– active species.

Figure 9.

(a) DMPO spin-trapping EPR spectra of DMPO-•O2– in methanol dispersion in the Rh B degradation experiment and (b) DMPO-•OH in aqueous dispersion in the Rh B degradation experiment with the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite.

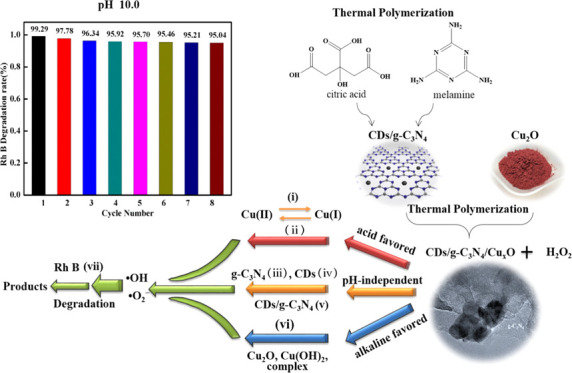

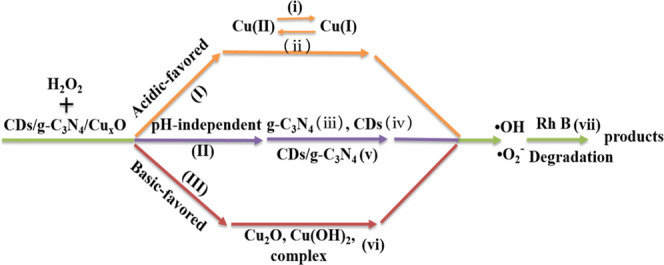

2.2.6.2. Mechanism

Based on the above-mentioned results, a mechanism was proposed (see Scheme 1). In the heterogeneous system containing the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite, H2O2, and Rh B, there are acidic-favored solution reactions, basic-favored surface reactions, and pH-independent surface reactions, while the surface reactions dominate the degradation of Rh B.

Scheme 1. Mechanism of Various Radical Generations over CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO in a Catalytic System.

It can be said that under acidic conditions, dissolved Cu(I) is mainly generated in the reaction system and undergoes a homogenous Fenton-like reaction with H2O2 to produce •OH and •O2– in solution; the related process is presented in (i) and (ii) and denoted reaction (I).30 However, under basic conditions, Cu2O, Cu(OH)2, and the complex mainly exist in the reaction system, which can react with H2O2 to produce •OH and •O2– radicals through surface reactions, mostly catalytic decomposition of H2O2, and the related reaction III is shown as (Vi).56,57 Besides, H2O2 can be catalytically decomposed on the surface of CDs, g-C3N4, and the matrix of the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite, generating •OH and •O2– (as per the related process presented as (iii), (iv), and (v)) (i.e., reaction II).26,66,67 Since reaction (II) did not involve light exposure, it was relatively slow in this work, and the reactions are pH-independent.57 Therefore, the major reactions in the heterogeneous system are reactions (I) and (II) in the acidic solution and reactions (II) and (III) in the basic solution. The role of reaction (I) is more significant under the acidic condition as compared to the basic condition (Figures 5 and S7). However, the major reactions in the heterogeneous system are the surface reactions (II) and (III) irrespective of the solution pH.

As compared to the acidic conditions, under basic conditions, the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite exhibited stronger catalytic activity and stability, which can continuously decompose H2O2 to generate •OH and •O2– so as to induce Rh B degradation (Figures 5 and S9). Also, the curve of degradation of Rh B follows the decomposition trend of H2O2 with the same pH, thereby indicating that pH primarily affects the decomposition of H2O2 and thus the degradation of Rh B (Figure 5).

The •OH and •O2– produced in this reaction are used for the degradation of Rh B, and the related process is shown in (vii).66 For the analysis of Rh B products, the degradation products after the reaction could be analyzed by LC/MS.68 Generally, the decomposition of Rh B undergoes a three-step process: N-deethylation, chromophore cleavage with subsequent triazine ring-opening, and mineralization.69 The active free radicals produced by the reaction destroy the structure of Rh B, degrading it into less harmful compounds.

3. Conclusions

In this work, a catalyst CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO was synthesized by a simple homogeneous method of thermal polymerization with stepwise modification of g-C3N4 with CDs and Cu2O, the catalytic performance of which is strongly pH-dependent. The major findings are enumerated as follows.

In the applied pH range (3–11), the catalytic performance is increased by raising the solution pH (45–96%). The optimal pH was confirmed to be 10 due to the relatively high degradation ratio of Rh B, lower consumption of H2O2, and better recyclability.

The dry method in the recycling experiments shows better recyclability than using the wet method. The degradation ratio of Rh B, in the dry method at pH 10, remains 95% even after eight cycles.

The major reactive species leading to the Rh B degradation in the present system are confirmed to be •OH and •O2–.

In the proposed mechanism, the major reactions in the heterogeneous system are reactions (I) and (II) in the acidic solution, and the role of reaction (I) is more significant, while the major reactions are reactions (II) and (III) in the basic solution, which are mainly the surface reactions in the heterogeneous system.

Overall, in this study, we developed a promising Fenton-like catalyst that exhibits a wider working pH and good recyclability and overcomes the narrow workable pH of the Fenton reaction.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Reagents

Reagents used in this study included melamine (CP, C3H6N6, ≥99.0%), citric acid monohydrate (AR, C6H8O7·H2O, ≥99.5%), cuprous oxide (AR, Cu2O, ≥97.0%), hydrogen peroxide (CP, H2O2, 30.0%), acetic acid (AR, CH3COOH, ≥99.5%), sodium acetate (AR, CH3COONa·3H2O, ≥99.5%), potassium iodide (AR, KI, ≥99.0%), ammonium molybdate (CP, H8MoN2O4, 56.5%), ethanol (AR, C2H6O, 99.7%), hydrochloric acid (AR, HCl, 36%), sodium hydroxide (AR, NaOH, ≥98.0%), isopropanol (AR, IPA, ≥99.7%), p-benzoquinone (CP, BQ, ≥98.0%), rhodamine B (AR, C28H31ClN2O3, ≥99.0%), 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (AR, DMPO, ≥97.0%), and nitrogen (CP, N2, ≥99.0%) stored in gas cylinders. All solutions were prepared with deionized water, and all chemicals were supplied by the manufacturer (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent co. Ltd., Shanghai, China) and used as received without further purification.

4.2. Preparation of CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO Composites

4.2.1. CDs/g-C3N4

CDs/g-C3N4 composites were prepared by thermal polymerization, using citric acid monohydrate as the precursor of CDs as previously reported.70 Typically, 0.6 g of citric acid and 20 g of melamine were placed in an aluminum crucible, mixed well, and calcined at 600 °C for 3 h at the ramping rate of 2 °C min–1 in a muffle furnace. After naturally cooling down at room temperature (RT), the CD3/g-C3N4 composite was obtained. Furthermore, several CDy/g-C3N4 composites (y, 1–6) that included different amounts of CDs were prepared, where y represents the initial mass ratio of citric acid monohydrate to melamine.

4.2.2. CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO Composite

The cuprous oxide (Cu2O)-modified CDs/g-C3N4 composite was prepared by a similar thermal polymerization pathway as previously reported.71 Typically, 5 g of CDs/g-C3N4 composite material and 0.14 g of Cu2O were added to 10 mL of ethanol solution with stirring for 0.5 h. The mixed material/solution was placed in an aluminum crucible, heated at a ramp of 1 °C min–1 to 520 °C for 3 h, and cooled to RT in a muffle furnace. The derived powder was stored and labeled as C2. Additionally, CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composites that included different amounts of Cu2O were prepared (Table S5).

4.3. Material Characterization

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (Nicolet iS5 FT-IR spectrometer, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to investigate the samples of infrared absorption spectra using the standard potassium bromide (KBr) disk method in the wavenumber range from 400 to 4000 cm–1.

The structural properties of the composite were detected by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, D/max- III A, Bruker Corporation, Germany) measurements, which used Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å; angle of 2θ, 10–70°).

The morphology and microstructure of the synthesized composites were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (TEM JEM-2100 model, JEOL Ltd., Japan) and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM).

An investigation of the surface component elemental state of the resultant catalyst was done using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, via an ESCALAB 250XI, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and the C 1s signal at 284.60 eV was used as the internal standard to calibrate binding energies.

The specific surface and pore volume were analyzed by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) (TriStar II 3020, Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, Georgia) via isothermal desorption and adsorption with high-purity nitrogen.

The absorbance of the studied reagents, i.e., H2O2 and Rh B, was measured by a V-5600 spectrophotometer (Shanghai Metash Instruments Co. Ltd., China) and a UV-5500 PC (Shanghai Metash Instruments Co. Ltd., China) spectrophotometer in the wavelength range of 200–800 nm.

The pH of the solutions was measured using the ST2100 pH meter (China) with an accuracy of ±0.01 pH units and a working temperature from 5 to 40 °C.

The prepared samples were weighed to ±10–4 g in an ME104E microbalance (Mettler Toledo, China).

The dissolved oxygen (DO) of the solution was analyzed by the portable dissolved oxygen meter (JPB-607A, China).

An inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) Prodigy 7 (Teledyne instrument Labs, Mason, OH) was used to measure the total copper ion concentration of the solution.

The ROS were detected by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) using an A300 spectrometer (Bruker Instrument, Germany) and spin-trapping agents such as 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrrolidine-N-oxide (DMPO, 100 mM) aqueous solution (Bruker Instrument, Germany).

4.4. Catalytic Activity Experiment

Rh B was used as the target dye for evaluating the catalytic properties of the synthesized composites. All catalytic degradation experiments were conducted in the dark with magnetic stirring at RT.

In a typical experiment, a certain amount of synthesized composite was added to the Rh B solution and stirred for 40 min to achieve adsorption/desorption equilibrium before the addition of H2O2, which triggered the catalysis. At fixed time points, 4 mL of suspension was taken and filtered using a 0.22 μm membrane filter. The absorbance was measured so as to obtain the time-resolved concentrations of H2O2 and Rh B. In some cases, the concentrations of H2O2, Rh B, and dissolved copper species in the filtered samples were also monitored to evaluate the potential reaction in the homogeneous system.

The concentration of Rh B was determined by measuring the absorbance at 555 nm using an ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectrophotometer. The H2O2 concentration was detected by the Ghormley triiodide method, which states that I– could be oxidized to triiodide (I3–) by H2O2 in the presence of acetic acid and the catalyst ammonium molybdate (AMD). The absorbance of I3– can be measured by a spectrophotometer at 350 nm.72 The intermediate products produced in the experiment may interfere with the measurements, but the experimental error was less than 2% for the concentrations of Rh B and H2O2 determined.

The specific free radical scavengers, including benzoquinone (BQ) and isopropanol (IPA), were separately added into the suspension after the adsorption–desorption equilibrium before the addition of H2O2, scavenging •O2– and •OH, respectively.73 Additionally, the suspension was purged with N2 to remove O2 in the whole reaction process.

The degree of degradation was expressed by degradation ratios and utilization, which are defined in eqs 3 and 4,74 where [Rh B]0 or [H2O2]0 is the initial concentration of Rh B and H2O2, and [Rh B]t or [H2O2]t is the concentration of Rh B (mM) or H2O2 at time t (t = 60 min), respectively. All of these experiments were carried out in beakers in the dark to avoid dye sensitization.

| 3 |

| 4 |

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (217071108) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (WUT: 2018IVB044).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c05915.

FT-IR spectra of g-C3N4, CD3/g-C3N4, and CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composites (Figure S1); XRD patterns of Cu2O, g-C3N4, CD3/g-C3N4, and CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composites (Figure S2); XPS spectra of the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite (Figure S3); high-resolution XPS spectra of O 1s (Figure S4); N2 adsorption/desorption isotherm and the pore-size distribution of g-C3N4, CD3/g-C3N4,and CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO (Figure S5); [Rh B]/[Rh B]0 as a function of time with different H2O2 concentrations in the presence of 2 g/L CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite with the initial concentration of [Rh B]0 = 0.064 mM and V = 100 mL (Figure S6); [Rh B]/[Rh B]0 as a function of time in stock CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO (2 g/L) suspensions and filtrates obtained at selected time intervals with the initial concentration of [Rh B]0 = 0.064 mM, [H2O2]0 = 5 mM, and V = 100 mL; degradation of Rh B in heterogeneous catalytic reaction and filtered solution in 1 min reacting over a longer period of time (Figure S7); variation of the Rh B wavelength at different pH values (Figure S8); recycling performance for 5 mM H2O2 decomposition in the presence of the 2 g/L CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite at pH 11 at 25 min per cycle and V = 100 mL; recycling performance of the 2 g/L CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite for Rh B (0.064 mM) degradation in the presence of 5 mM H2O2 at pH 11 at 30 min per cycle (Figure S9); [Rh B]/[Rh B]0 as a function of time in the presence of the 2 g/L CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite for Rh B (0.064 mM) degradation in the presence of 10 mM H2O2 at pH 11 (Figure S10); H2O2 consumed in cycling reactions by the 2 g/L CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite for Rh B (0.064 mM) degradation in the presence of 5 mM H2O2 at pH 4.6 (unadjusted pH; V = 100 mL); recycling degradation of the Rh B (0.064 mM) was conducted by the 2 g/L CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite in the presence of 5 mM H2O2 at pH 4.6 (unadjusted pH; V = 100 mL) (Figure S11); [Rh B]/[Rh B]0 and [H2O2]/[H2O2]0 as a function of time in the presence of different quenchers by the 2 g/L CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite for Rh B (0.064 mM) degradation in the presence of 5 mM H2O2; parameters of the pseudo-first-order kinetic models of different quenchers by the 2 g/L CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite for Rh B (0.064 mM) degradation in the presence of 5 mM H2O2; [Rh B]/[Rh B]0 as a function of time in the presence of different quenchers by the 2 g/L CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite for Rh B (0.064 mM) degradation in the presence of 5 mM H2O2 at different pH values (Figure S12); XPS results of the CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composite (Table S1); efficiency of Rh B at different H2O2 concentrations (Table S2); comparison of the catalytic performance of CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO and several reported relative studies (Table S3); reaction formulas and reaction rate constants of possible reactions in radical trapping (Table S4); and the initial mass ratio of Cu2O to CDs/g-C3N4 for CDs/g-C3N4/CuxO composites (Table S5) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Gui L.; Peng J.; Li P.; Peng R.; Yu P.; Luo Y. Electrochemical degradation of dye on TiO2 nanotube array constructed anode. Chemosphere 2019, 235, 1189–1196. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.06.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phanichphant S.; Nakaruk A.; Channei D. Photocatalytic activity of the binary composite CeO2/SiO2 for degradation of dye. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 387, 214–220. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.06.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q.; Mao Q.; Zhou Y.; Wei J.; Liu X.; Yang J.; Luo L.; Zhang J.; Chen H.; Chen H.; et al. Metal-free carbon materials-catalyzed sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation processes: A review on heterogeneous catalysts and applications. Chemosphere 2017, 189, 224–238. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An T.; Yang H.; Li G.; Song W.; Nie X.; et al. Kinetics and mechanism of advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) in degradation of ciprofloxacin in water. Appl. Catal., B 2010, 94, 288–294. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2009.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bilińska L.; Gmurek M.; Ledakowicz S. Textile wastewater treatment by AOPs for brine reuse. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 109, 420–428. 10.1016/j.psep.2017.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrat F.; Paluch S.; Dogruoz E.; Dorfler P.; Kirsch M.; Korth H. G.; Sustmann R.; De Groot H. Reduction of Fe(III) ions complexed to physiological ligands by lipoyl dehydrogenase and other flavoenzymes in vitro: implications for an enzymatic reduction of Fe(III) ions of the labile iron pool. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 46403–46413. 10.1074/jbc.M305291200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi M.; Habibi-Yangjeh A.; Pouran S. R. Review on magnetically separable graphitic carbon nitride-based nanocomposites as promising visible-light-driven photocatalysts. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 1719–1747. 10.1007/s10854-017-8166-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eshaq G.; ElMetwally A. E. Bmim[OAc]-Cu2O/g-C3N4 as a multi-function catalyst for sonophotocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 53, 99–109. 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Wang Y.; Wang Y.; Cao T.; Zhao G. Electro-Fenton oxidation of pesticides with a novel Fe3O4@Fe2O3/activated carbon aerogel cathode: High activity, wide pH range and catalytic mechanism. Appl. Catal., B 2012, 125, 120–127. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2012.05.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F.; Xie S.; Huang X.; Qiu X. Ionothermal synthesis of Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles as efficient heterogeneous Fenton-like catalysts for degradation of organic pollutants with H2O2. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 322, 152–162. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Wu X.; Long Z.; Zhang C.; Ma Y.; Hao X.; Zhang H.; Pan C. Photodegradation of Imidacloprid in Aqueous Solution by the Metal-Free Catalyst Graphitic Carbon Nitride using an Energy-Saving Lamp. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2015, 63, 4754–4760. 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b01105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Zhao L.; Geng F.; Guo L.-H.; Wan B.; Yang Y. Carbon dots decorated graphitic carbon nitride as an efficient metal-free photocatalyst for phenol degradation. Appl. Catal., B 2016, 180, 656–662. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.06.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S.; Xia Y.; Lv K.; Li Q.; Jie S.; Mei L. Effect of carbon-dots modification on the structure and photocatalytic activity of g-C3N4. Appl. Catal., B 2016, 185, 225–232. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X.; Wang L.; Wang Y.; Yao W.; Zhu Y. Enhanced oxidation ability of g-C3N4 photocatalyst via C60 modification. Appl. Catal., B 2014, 152–153, 262–270. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2014.01.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Wang J.; Dong Y.; Jiang P. Noble-Metal-Free Iron Phosphide Cocatalyst Loaded Graphitic Carbon Nitride as an Efficient and Robust Photocatalyst for Hydrogen Evolution under Visible Light Irradiation. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 8053–8060. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b01665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S.; Xia Y.; Lv K.; Li Q.; Sun J.; Li M. Effect of carbon-dots modification on the structure and photocatalytic activity of g-C3N4. Appl. Catal., B 2016, 185, 225–232. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J. E.; Sorescu D. C.; Burkert S. C.; White D. L.; Star A. Uncondensed Graphitic Carbon Nitride on Reduced Graphene Oxide for Oxygen Sensing via a Photoredox Mechanism. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 27142–27151. 10.1021/acsami.7b06017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J.; Yang Q.; Wen Y.; Liu W. Fe-g-C3N4/graphitized mesoporous carbon composite as an effective Fenton-like catalyst in a wide pH range. Appl. Catal., B 2017, 201, 232–240. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.08.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Zan J.; Wu L.; Zuo S.; Xu H.; Xia D. Heterojunction Tuning and Catalytic Efficiency of g-C3N4-Cu2O with Glutamate. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 4000–4009. 10.1021/acs.iecr.8b04581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sano T.; Tsutsui S.; Koike K.; Hirakawa T.; Teramoto Y.; Negishi N.; Takeuchi K. Activation of graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) by alkaline hydrothermal treatment for photocatalytic NO oxidation in gas phase. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 6489–6496. 10.1039/c3ta10472a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akhundi A.; García-López E. I.; Marcì G.; Habibi-Yangjeh A.; Palmisano L. Comparison between preparative methodologies of nanostructured carbon nitride and their use as selective photocatalysts in water suspension. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2017, 43, 5153–5158. 10.1007/s11164-017-3046-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Liu Y.; Liu N.; Han Y.; Zhang X.; Huang H.; Lifshitz Y.; Lee S. T.; Zhong J.; Kang Z. Metal-free efficient photocatalyst for stable visible water splitting via a two-electron pathway. Science 2015, 347, 970–974. 10.1126/science.aaa3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Feng X.; Lu Z.; Yin H.; Liu F.; Xiang Q. Enhanced photocatalytic H2-production activity of C-dots modified g-C3N4/TiO2 nanosheets composites. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 513, 866–876. 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao X.; Yue X.; Ji Z.; Shen X.; Zhou H.; Liu M.; Xu K.; Zhu J.; Zhu G.; Kong L.; et al. Nitrogen-doped carbon dots decorated on g-C3N4/Ag3 PO4 photocatalyst with improved visible light photocatalytic activity and mechanism insight. Appl. Catal., B 2018, 227, 459–469. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.01.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dadigala R.; Bandi R.; Gangapuram B. R.; Guttena V. Carbon dots and Ag nanoparticles decorated g-C3N4 nanosheets for enhanced organic pollutants degradation under sunlight irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2017, 342, 42–52. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2017.03.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Shen Q.; Zhou C.; Fang L.; Yang M.; Xia T. Kinetic and Mechanistic Study on Catalytic Decomposition of Hydrogen Peroxide on Carbon-Nanodots/Graphitic Carbon Nitride Composite. Catalysts. 2018, 8, 445. 10.3390/catal8100445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F.; Shi W.; Guan W.; Huang H.; Liu Y. Carbon dots/g-C3N4/ZnO nanocomposite as efficient visible-light driven photocatalyst for tetracycline total degradation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 173, 295–303. 10.1016/j.seppur.2016.09.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B.; Li H.; Li X.; Liu X.; Zhang C.; Xu H.; Zhao X. S. Degradation of Organic Dyes over Fenton-Like Cu2O-Cu/C Catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 14011–14021. 10.1021/acs.iecr.8b02697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C.; Liu Z.; Fang L.; Guo Y.; Feng Y.; Yang M. Kinetic and Mechanistic Study of Rhodamine B Degradation by H2O2 and Cu/Al2O3/g-C3N4 Composite. Catalysts 2020, 10, 317 10.3390/catal10030317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S.; Zhu H.; Cao W.; Wen Z.; Wang J.; François-Xavier Philippe C.; Wintgens T. Cu-Al2O3-g-C3N4 and Cu-Al2O3-C-dots with dual-reaction centres for simultaneous enhancement of Fenton-like catalytic activity and selective H2O2 conversion to hydroxyl radicals. Appl. Catal., B 2018, 234, 223–233. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.04.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.; Wu Y.; Zhang J.; Han X.; Shi H. Visible-light-driven g-C3N4/Cu2O heterostructures with efficient photocatalytic activities for tetracycline degradation and microbial inactivation. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2019, 378, 1–8. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2019.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang P.-Y.; Tseng I.-H. Photocatalytic conversion of gas phase carbon dioxide by graphitic carbon nitride decorated with cuprous oxide with various morphologies. J. CO2 Util. 2018, 26, 511–521. 10.1016/j.jcou.2018.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asadzadeh-Khaneghah S.; Habibi-Yangjeh A.; Yubuta K. Novel g-C3N4 nanosheets/CDs/BiOCl photocatalysts with exceptional activity under visible light. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 102, 1435–1453. 10.1111/jace.15959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng B.; Zhang S.; Yang S.; Wang H.; Yu H.; Zhang S.; Peng F. Synthesis and characterization of g-C3N4/Cu2O composite catalyst with enhanced photocatalytic activity under visible light irradiation. Mater. Res. Bull. 2014, 56, 19–24. 10.1016/j.materresbull.2014.04.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Zan J.; Wu L.; Zuo S.; Xu H.; Xia D. Heterojunction Tuning and Catalytic Efficiency of g-C3N4-Cu2O with Glutamate. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 4000–4009. 10.1021/acs.iecr.8b04581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Zuo S.; Xu H.; Zan J.; Sun L.; Han D.; Liao W.; Zhang B.; Xia D. Synthesis of a g-C3N4-Cu2O heterojunction with enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity by PEG. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 531, 28–36. 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Kuo D. H.; Lu D. F. Nanonization of g-C3N4 with the assistance of activated carbon for improved visible light photocatalysis. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 66814–66821. 10.1039/C6RA10357J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S.; Zhu H.; Cao W.; Wen Z.; Wang J.; François-Xavier Philippe C.; Wintgens T. Cu-Al2O3-g-C3N4 and Cu-Al2O3-C-dots with dual-reaction centres for simultaneous enhancement of Fenton-like catalytic activity and selective H2O2 conversion to hydroxyl radicals. Appl. Catal., B 2018, 234, 223–233. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.04.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu K.; Bisht A.; Kuriakose S.; Mohapatra S. Two-dimensional CuO-ZnO nanohybrids with enhanced photocatalytic performance for removal of pollutants. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2020, 137, 109223 10.1016/j.jpcs.2019.109223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo S.; Xu H.; Liao W.; Yuan X.; Sun L.; Li Q.; Zan J.; Li D.; Xia D. Molten-salt synthesis of g-C3N4-Cu2O heterojunctions with highly enhanced photocatalytic performance. Colloids Surf., A. 2018, 546, 307–315. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S.; Yang X.; Kangle L.; Qin L.; Jie S. B.; et al. Effect of carbon-dots modification on the structure and photocatalytic activity of g-C3N4. Appl. Catal., B. 2016, 185, 225–232. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S.; Xia Y.; Lv K.; Li Q.; Sun J.; Li M. Effect of carbon-dots modification on the structure and photocatalytic activity of g-C3N4. Appl. Catal., B. 2016, 185, 225–232. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Min Z.; Wang X.; Li Y.; Jiang J.; Li J.; Qian D.; Li J. A highly efficient visible-light-responding Cu2O-TiO2/g-C3N4 photocatalyst for instantaneous discolorations of organic dyes. Mater. Lett. 2017, 193, 18–21. 10.1016/j.matlet.2017.01.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen S.; Mutreja V.; Singh S.; Pal B. Highly dispersed Au, Ag and Cu nanoparticles in mesoporous SBA-15 for highly selective catalytic reduction of nitroaromatics. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 184–190. 10.1039/C4RA10050F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X.; Zhang J.; Wang B.; Li Q.; Chu S. Hierarchical Cu2O foam/g-C3N4 photocathode for photoelectrochemical hydrogen production. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 427, 907–916. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.09.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji C.; Yin S.-N.; Sun S.; Yang S. An in situ mediator-free route to fabricate Cu2O/g-C3N4 type-II heterojunctions for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic H2 generation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 434, 1224–1231. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.11.233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo S.; Haiming X.; Wei L.; Xiangjuan Y.; Lei S.; Qiang L.; Jie Z.; Dongya L.; Xia D. Molten-salt synthesis of g-C3N4-Cu2O heterojunctions with highly enhanced photocatalytic performance. Colloids Surf., A 2018, 546, 307–305. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thaweesak S.; Wang S.; Lyu M.; Xiao M.; Peerakiatkhajohn P.; Wang L. Boron-doped graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets for enhanced visible light photocatalytic water splitting. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 10714–10720. 10.1039/C7DT00933J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavitha V.; Palanivelu K. Destruction of cresols by Fenton oxidation process. Water Res. 2005, 39, 3062–3072. 10.1016/j.watres.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Gao H.; Huang Y.; Wang X.; Hayat T.; Li J.; Xu X.; Wang X. Ultrathin g-C3N4 nanosheets coupled with amorphous Cu-doped FeOOH nanoclusters as 2D/0D heterogeneous catalysts for water remediation. Environ. Sci.: Nano 2018, 5, 1179–1190. 10.1039/C8EN00124C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L.; Liu Z.; Zhou C.; Guo Y.; Feng Y.; Yang M. Degradation Mechanism of Methylene Blue by H2O2 and Synthesized Carbon Nanodots/Graphitic Carbon Nitride/Fe(II) Composite. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 26921–26931. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b06774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M.; Jonsson M. Evaluation of the O2 and pH Effects on Probes for Surface Bound Hydroxyl Radicals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 7971–7979. 10.1021/jp412571p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babuponnusami A.; Muthukumar K. A review on Fenton and improvements to the Fenton process for wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 557–572. 10.1016/j.jece.2013.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q.-B.; Hofmann J. P.; Litke A.; Hensen E. J. M. Cu2O photoelectrodes for solar water splitting: Tuning photoelectrochemical performance by controlled faceting. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2015, 141, 178–186. 10.1016/j.solmat.2015.05.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.; Kang L.; Zhou M.; Zhong Z.; Xing W. Membrane enhanced COD degradation of pulp wastewater using Cu2O/H2O2 heterogeneous Fenton process. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 26, 1896–1903. 10.1016/j.cjche.2018.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q.-B.; Hofmann J. P.; Litke A.; Hensen E. J. M. Cu2O photoelectrodes for solar water splitting: Tuning photoelectrochemical performance by controlled faceting. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2015, 141, 178–186. 10.1016/j.solmat.2015.05.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aylmore M. G.; Muir D. M. Thermodynamic analysis of gold leaching by ammoniacal thiosulfate using Eh/pH and speciation diagrams. Min., Metall., Explor. 2001, 18, 221–227. 10.1007/BF03403254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.; Zhu Z.; Zhang H.; Shen X.; Qiu Y.; Yin D. Enhanced Removal of Veterinary Antibiotic Florfenicol by a Cu-Based Fenton-like Catalyst with Wide pH Adaptability and High Efficiency. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 1982–1994. 10.1021/acsomega.8b03406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu L.; Han M.; Cao W.; Gao Y.; Zeng Q.; Yu G.; Huang X.; Hu C. Efficient Fenton-like process for organic pollutant degradation on Cu-doped mesoporous polyimide nanocomposites. Environ. Sci.: Nano 2019, 6, 798–808. 10.1039/C8EN01365A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nekoeinia M.; Yousefinejad S.; Hasanpour F.; Yousefian-Dezaki M. Highly efficient catalytic degradation of p-nitrophenol by Mn3O4.CuO nanocomposite as a heterogeneous fenton-like catalyst. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2020, 15, 322–336. 10.1080/17458080.2020.1796977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Liu C.; Xu B.; Qi F.; Chu W. Degradation of benzotriazole by a novel Fenton-like reaction with mesoporous Cu/MnO2: Combination of adsorption and catalysis oxidation. Appl. Catal., B 2016, 199, 447–457. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watts R. J.; Teel A. L. Hydroxyl radical and non-hydroxyl radical pathways for trichloroethylene and perchloroethylene degradation in catalyzed H2O2 propagation systems. Water Res. 2019, 159, 46–54. 10.1016/j.watres.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez E. M.; Márquez G.; Tena M.; Álvarez P. M.; Beltrán F. J. Determination of main species involved in the first steps of TiO2 photocatalytic degradation of organics with the use of scavengers: The case of ofloxacin. Appl. Catal., B 2015, 178, 44–53. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2014.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong G.; Ai Z.; Zhang L. Total aerobic destruction of azo contaminants with nanoscale zero-valent copper at neutral pH: promotion effect of in-situ generated carbon center radicals. Water Res. 2014, 66, 22–30. 10.1016/j.watres.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H.; Liu X.; Liu F.; Hao Z.; Zhang J.; Lin Z.; Barnett Y.; Pan G. Visible-light photocatalysis accelerates As(III) release and oxidation from arsenic-containing sludge. Appl. Catal., B 2019, 250, 1–9. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.03.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Li D.; Nan Z. Effect of N content in g-C3N4 as metal-free catalyst on H2O2 decomposition for MB degradation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 224, 152–162. 10.1016/j.seppur.2019.04.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q.; Liu G.; Yan M.; Ye J.; Zhu L.; Huang J.; Yang X. Cu(2+) enhanced chemiluminescence of carbon dots-H2O2 system in alkaline solution. Talanta 2020, 208, 120380 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.120380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z.; Yang S.; Ju Y.; Sun C. Microwave photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B using TiO2 supported on activated carbon: Mechanism implication. Global J. Environ. Sci. 2009, 21, 268–272. 10.1016/S1001-0742(08)62262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatima R.; Kim J.-O. Inhibiting photocatalytic electron-hole recombination by coupling MIL-125(Ti) with chemically reduced, nitrogen-containing graphene oxide. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 541, 148503 10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.148503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Datta A.; Kapri S.; Bhattacharyya S. Carbon dots with tunable concentrations of trapped anti oxidant as an efficient metal-free catalyst for electrochemical water oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 14614–14624. 10.1039/C6TA04737H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Shen S.; Guo P.; Wang M.; Wu P.; Wang X.; Guo L. In-situ reduction synthesis of nano-sized Cu2O particles modifying g-C3N4 for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production. Appl. Catal., B 2014, 152–153, 335–341. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2014.01.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M.; Zhang X.; Grosjean A.; Soroka I.; Jonsson M. Kinetics and Mechanism of the Reaction between H2O2 and Tungsten Powder in Water. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 22560–22569. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b07012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Guo Y.; Chen Z.; Zhang Z.; Fang X. Constructing a novel ternary Fe(III)/graphene/g-C3N4 composite photocatalyst with enhanced visible-light driven photocatalytic activity via interfacial charge transfer effect. Appl. Catal., B 2016, 183, 231–241. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.10.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L.; Liu Z.; Zhou C.; Guo Y.; Feng Y.; Yang M. Degradation Mechanism of Methylene Blue by H2O2 and Synthesized Carbon Nanodots/Graphitic Carbon Nitride/Fe(II) Composite. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 26921–26931. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b06774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.