Abstract

Identifying markers capable of predicting outcomes in lung cancer patients treated with nivolumab represents a growing research interest. The combination of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and body mass index (BMI) may help predict treatment efficacy. Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the influence of NLR and BMI on progression-free survival (PFS) in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients treated with nivolumab. A retrospective study was made on 80 patients with NSCLC that were treated with nivolumab at the OncoHelp Oncology Center, Timisoara, Romania after platinum-based chemotherapy, from January 2018 to April 2020. Patients were administered nivolumab at a dose of 3 mg/m2 or 240 mg total dose, every 2 weeks. The predictive impact of NLR (baseline at 2 and 4 weeks after the start of nivolumab) and BMI for disease progression was assessed. Median PFS for subjects with NLR <3 before treatment was 18.5 weeks, while in subjects with NLR ≥3 was 14 weeks (P=0.50). Median PFS for subjects with NLR2 <3 at 2 weeks after treatment was 21 weeks, while in subjects with NLR2 ≥3, PFS was 14 weeks (P=0.17). Median PFS for subjects with NLR4 <3 at 4 weeks after treatment was 23 weeks, while in subjects with NLR4 ≥3, PFS was 19 weeks (P=0.33). Multivariate analysis for the association with PFS showed that baseline NLR, male sex and BMI were associated independently, thus we could develop a significant statistical model [AUROC=0.76, 95% CI (0.45-0.89), P=0.03], a new predictive score for PFS. The assessment of NLR and BMI may represent simple and useful biomarkers; combining them and taking into consideration the male sex may predict PFS in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with nivolumab.

Keywords: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, body mass index, nutritional status, predictive score, progression-free survival, non-small-cell lung cancer, NSCLC, nivolumab

Introduction

Lung cancer (LC) remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality and the most common diagnosed cancer worldwide, in both sexes and for all age groups; in 2018 an estimated 1.7 million deaths, with an incidence of approximately 2 million cases were reported (1). The histology of LC is represented by small cell lung cancer at a proportion of 15%, while non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) represents about 85% of all LC cases (2).

In recent years, the role of immunotherapy for the treatment of cancer has been highlighted and the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has led to improved patient survival (3). Nivolumab, a fully human anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) immunoglobulin G4 monoclonal antibody (mAb) is the first ICI to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of previously treated advanced or metastatic NSCLC after prior chemotherapy in adults (4). However, the treatment response with nivolumab varies and a reliable biomarker to assess the prediction of clinical outcome using this anti-PD-1 mAb has not yet been established (4).

It is widely known that inflammation plays an important role in the development and propagation of many diseases, including cancer. Moreover, many retrospective studies regarding various cancer sites have concluded that systemic inflammation, indexed commonly by the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), calculated as the ratio between the absolute neutrophil count and the absolute lymphocyte count in the peripheral blood, is associated with a poorer prognosis in patients with cancer (5,6).

Another key factor in the development and therapeutic response in cancer is represented by the body mass index (BMI), where obesity appears to influence the immune system and to induce a state of low-grade inflammation (7). Furthermore, Cortellini et al found that overweight/obese patients who suffer from different types of diseases, including lung cancer, have a better response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies (8), a fact also observed in other retrospective studies regarding advanced/metastatic melanoma (9,10).

The association between inflammatory and nutritional status may help predict treatment efficacy and allow patient selection for different types of treatment. Therefore, our study aimed to investigate the influence of baseline NLR and BMI on progression-free survival (PFS) in NSCLC patients treated with nivolumab.

Patients and methods

Study population

A retrospective study was carried out on 80 patients with NSCLC who were treated with nivolumab after failed response to platinum-based chemotherapy, from January 2018 to April 2020, at the OncoHelp Oncology Center, Timisoara, Romania.

Inclusion criteria were: Patients older than 18 years of age, diagnosed with NSCLC as confirmed by histopathological analysis, who failed first-line treatment. Exclusion criteria were patients who did not have the available biochemical tests and evaluation of nutritional status. Nivolumab (3 mg/m2 or 240 mg total dose) was administered every 2 weeks until the occurrence of disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, treatment withdrawal or patient death.

PFS was the time from the start of nivolumab treatment to disease progression or death.

All patients gave their informed consent for data collection. The study protocol was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration after the approval by OncoHelp Oncology Center's Ethics Committee (no. 1b/27.04.2020).

Clinical assessment

Clinical assessment, anthropometric and demographic data were collected from the medical records including: Age, sex, hemogram parameters (leukocyte count, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, platelet count, hemoglobin value, NLR) at initial diagnosis, after 2 and after 4 weeks, pathological diagnosis, tumor stage, treatment, progression, and death. TNM staging was recorded for all patients. The NLR ratio was obtained from the absolute neutrophil count and the absolute lymphocyte count and for the first analysis, it was dichotomized according to previous literature (11), NLR ≥3 and NLR <3. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by square of the height in meters. Underweight, normal weight, overweight and obesity were defined as BMI <18.5 kg/m², BMI ≥18.5 and <25 kg/m², BMI ≥25 and <30 kg/m² and BMI ≥30 kg/m², respectively.

Statistical analysis

MedCalc software for Windows (v. 19.2.0) (https://www.medcalc.org/) and the R software packages (v.3.3) (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://cran.r-project.org/) were used for statistical computing. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used for testing the distribution of numerical variables. Qualitative variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Parametric tests (t-test, ANOVA) were used for the assessment of differences between numerical variables with normal distribution and nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis tests) for variables with non-normal distribution. The Chi-square (χ²) test was used for comparing proportions expressed as percentages (‘n’ designates the total number of patients included in a particular subgroup). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the association between variables. Survival curves were calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method and differences between groups were assessed with the log-rank test. Multivariate survival analysis was carried out using the Cox proportional hazards model. For the best threshold, the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve analysis was used, by identifying the optimal cut-off values using the Youden index. We considered a P-value of 0.05 as the threshold for statistical significance and a confidence level of 95% for estimating intervals.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 80 patients were included in the study (mean age 60.91±8.42, 70% male). Patient characteristics are documented in Table I. A total of 54/80 (67.5%) patients were diagnosed with adenocarcinomas, 20/80 (25.0%) patients with squamous cell carcinoma and 6/80 (7.5%) patients with uncategorized NSCLC. A total of 4/80 (5%) patients had epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation and 1/80 (1.2%) patients had echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fusion gene. The most prevalent nutritional status was normal weight (51.2%); 50 subjects (62.5%) had NLR ≥3. Additional characteristics are presented in Table I.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the NSCLC patients (N=80).

| Parameter | Data values |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 60.91±8.42 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 56 (70.0) |

| BMI (kg/m²), mean ± SD | 25.03±5.36 |

| NLR ≥3, n (%) | |

| Yes | 50 (62.5) |

| No | 30 (37.5) |

| Nutritional status, n (%) | |

| Underweight | 3 (3.7) |

| Normal weight | 41 (51.2) |

| Overweight/obese | 36 (45.0) |

| Histological type, n (%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 54 (67.5) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 20 (25.0) |

| Uncategorized NSCLC | 6 (7.5) |

| Targetable driver mutation, n (%) | |

| EGFR | 4 (5.0) |

| ALK | 1 (1.2) |

| Stage, n (%) | |

| 1 | 2 (2.5) |

| 2 | 5 (6.2) |

| 3 | 25 (31.2) |

| 4 | 48 (60.0) |

| Progressive disease, n (%) | |

| Yes | 21 (26.2) |

| No | 59 (67.5) |

| Status, n (%) | |

| Alive | 52 (65.0) |

| Deceased | 28 (35.0) |

BMI, body mass index; n, number of observations; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; NSCLC, non-small cell carcinoma; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase.

The frequency of nutritional status, evaluated by BMI, showed some differences according to age (P=0.01). Subjects under 65 years had a higher prevalence of normal weight (54%), while subjects over 65 years had a higher prevalence of overweight/obese (50%). There were no differences between the NLR distribution in subjects under 65 years and subjects over 65 years (70 vs. 50%, P=0.12).

Treatment response and survival analysis

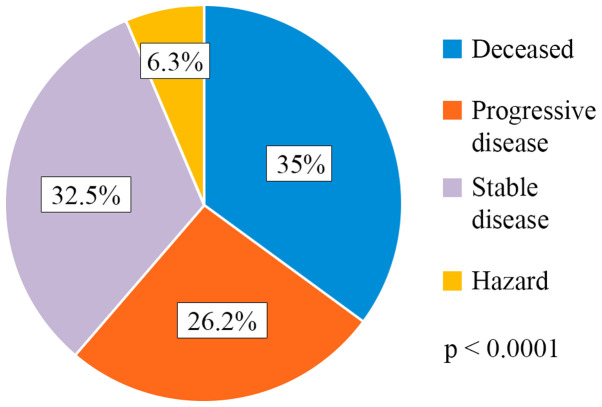

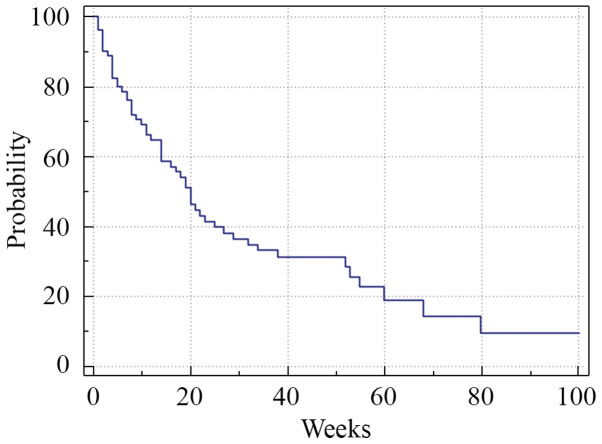

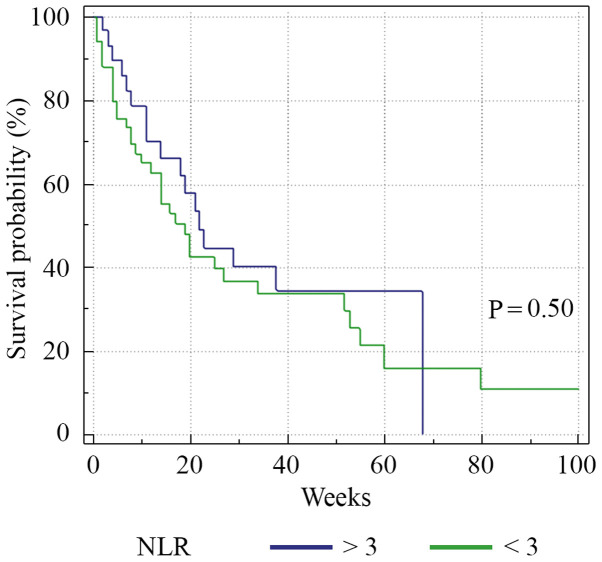

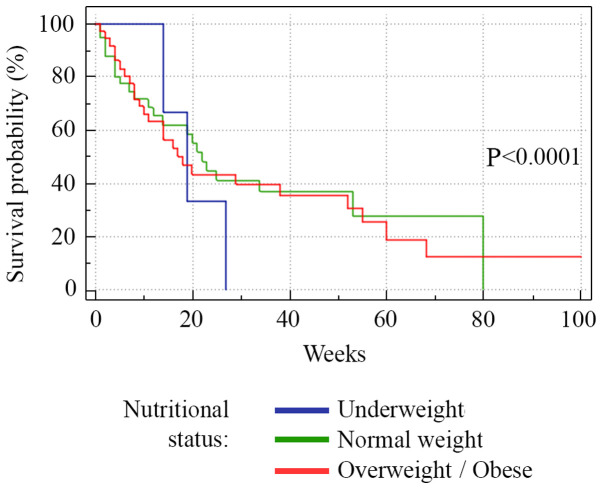

A total of 35% of the patients succumbed to the disease (28/80), 26.2% of the patients had progressive disease (21/80), 32.5% (26/80) had stable disease and 6.3% (5/80) were hazard (lost from evidence due to non-oncological causes or low compliance for treatment) (Fig. 1). Median PFS was 13 weeks (range 1-80) (Fig. 2). Analysis of the survival curve showed that the NLR above the proposed cut-off point was significantly associated with underweight patients (P=0.04) and lower survival (P=0.01). The differences between survival time of the patients with NLR >3 and those with NLR <3 are showed in Fig. 3. Regarding nutritional status, overweight/obese subjects had a higher survival rate (P=0.001), while underweight subjects had a lower survival rate (P=0.0001) (Fig. 4).

Figure 1.

Treatment response distribution.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. Median PFS was 13 weeks (range 1-80). The horizontal axis represents PFS measured in weeks and the vertical axis represents the percentage of patients who survived without progression at a given time. PFS, progression-free survival.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier plots quantifying the effects of NLR on PFS. The horizontal axis represents PFS measured in weeks and the vertical axis represents the percentage of patients who survived without progression at a given time, depending on the NLR value. PFS, progression-free survival; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier plots quantifying the effects of nutritional status on the PFS in NSCLC patients. The horizontal axis represents PFS measured in weeks and the vertical axis represents the percentage of patients who survived without progression at a given time, depending on the nutritional status. PFS, progression-free survival; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer.

Relationship between NLR and PFS

We analyzed initial NLR, NLR at 2 weeks (NLR2) and NLR at 4 weeks (NLR4). The median PFS for subjects with NLR <3 before treatment was 18.5 weeks, while in subjects with NLR ≥3 the median PFS was 14 weeks (P=0.50). The median PFS for subjects with NLR2 <3 at 2 weeks after treatment was 21 weeks, while in subjects with NLR2 ≥3 the PFS was 14 weeks (P=0.17). The median PFS for subjects with NLR4 <3 at 4 weeks after treatment was 23 weeks, while in subjects with NLR4 ≥3, the PFS was 19 weeks (P=0.33).

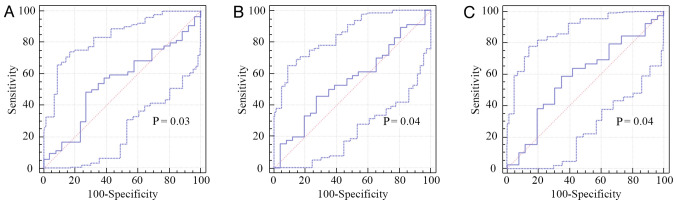

As initial NLR, NLR2 and NLR4 are good predictors for PFS (P=0.03, P=0.04 and P=0.04, respectively), we obtained new cut-off values for predicting PFS (Table II; Fig. 5).

Table II.

Performance of baseline NLR, NLR2 and NLR4 for predicting PFS.

| Variable | Cut-off | AUROC | P-value | Se (%) | Sp (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLR | 3.28 | 0.55 | <0.0001 | 71.4 | 49.1 | 33.3 | 82.9 |

| NLR2 | 3.26 | 0.56 | <0.0001 | 60.8 | 46.1 | 66.7 | 40 |

| NLR4 | 3.49 | 0.59 | <0.0001 | 58.9 | 65.3 | 71.9 | 51.5 |

NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; NLR2, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio after 2 weeks from the beginning of the treatment; NLR4, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio after 4 weeks from the beginning of the treatment; AUROC, area under the receiver operating curve; Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; PPV, positive predicting value; NPV, negative predicting value.

Figure 5.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis for (A) baseline NLR, (B) NLR at 2 weeks after initial treatment, and (C) NLR at 4 weeks after initial treatment.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

We also investigated factors that are associated with NLR (Table III) and other factors that may be associated with the outcome of nivolumab treatment, such as age of >65 years, sex, BMI and nutritional status. The factors associated with NLR in univariate analysis were male sex, age over 65 years, BMI value and underweight patients. In multivariate analysis, only BMI value and underweight patients were independently associated. Underweight status was able to increase the NLR value by 27 times (OR=27), normal weight patients by 2 times (OR=2.07), while overweight/obese patients appeared to have a protective role over NLR value (OR=0.60). For PFS, in univariate logistic regression analysis (Table IV), NLR, male sex and BMI value were associated (P=0.001, P=0.02, P=0.01, respectively). Multivariate analysis for the association with PFS showed that the same variables, NLR, male sex and BMI, were associated independently, thus we were able to develop a significant statistical model [AUROC=0.76, 95% CI (0.45-0.89), P=0.03], a new predictive score for PFS:

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression model for NLR by clinical characteristics of the NSCLC patients.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age over 65 years | 0.42 (0.16-1.09) | 0.04 | 0.89 (0.65-1.2) | 0.48 |

| Male sex | 1.05 (0.38-2.91) | 0.03 | 1.28 (0.54-1.8) | 0.91 |

| BMI value | 0.96 (0.58-1.56) | 0.01 | 1.01 (0.23-1.9) | 0.001 |

| Nutritional status | ||||

| Underweight | 27 (7.1-30) | 0.04 | 15 (5.7-21.3) | 0.01 |

| Normal weight | 2.07 (0.82-5.20) | 0.11 | - | - |

| Overweight/obese | 0.60 (0.24-1.49) | 0.27 | - | - |

NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; BMI, body mass index; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table IV.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression model for PFS by clinical characteristics of the NSCLC patients.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age over 65 years | 0.86 (0.20-1.10) | 0.56 | - | - |

| NLR | 1.03 (0.37-2.88) | 0.001 | 1.10 (0.38-3.12) | 0.01 |

| Male sex | 0.80 (0.27-2.35) | 0.02 | 0.95 (0.86-1.05) | 0.04 |

| BMI value | 0.95 (0.87-1.01) | 0.01 | 0.96 (0.96-1.91) | 0.001 |

| Nutritional status | ||||

| Underweight | 1.42 (0.12-16.5) | 0.77 | - | - |

| Normal weight | 1.37 (0.50-3.76) | 0.55 | - | - |

| Overweight/obese | 0.84 (0.28-2.51) | 0.75 | - | - |

PFS, progression-free survival; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; BMI, body mass index; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

PFS-NSCLC Score=0.43-0.08 x NLR value + 0.02 x BMI value + 1 (if male)

The best cut-off value for a poor PFS for this score in our cohort was 1.32, with a sensitivity of 90.4% and a negative predictive value of 95.7%.

Multivariate Cox regression demonstrated that NLR ≥3 (HR=2.21, P=0.03) and male sex (HR=1.10, P=0.01) were identified as independent poor prognostic factors for PFS. Conversely, normal weight subjects (HR=0.52, P<0.0001) and overweight/obese subjects (HR=0.45, P<0.0001) presented a better prognosis (Table V).

Table V.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression models of factors that may influence patient survival.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||||

| Variables | HR | Lower | Upper | P-value | HR | Lower | Upper | P-value |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| <65 | 1.20 | 1.01 | 1.68 | 0.85 | 1.10 | 0.35 | 1.94 | 0.76 |

| ≥65 | 0.97 | 0.55 | 1.72 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.55 | 1.76 | 0.97 |

| Nutritional status | ||||||||

| Underweight | 1.27 | 0.31 | 5.20 | 0.73 | 1.08 | 0.24 | 4.79 | 0.91 |

| Normal weight | 0.90 | 0.52 | 1.56 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.15 | 1.73 | <0.0001 |

| Overweight/obese | 1.10 | 0.64 | 1.89 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 1.25 | <0.0001 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| F | 1.01 | 0.56 | 1.81 | 0.96 | - | - | - | - |

| M | 1.06 | 1.02 | 1.10 | 0.01 | 1.10 | 0.95 | 1.90 | 0.01 |

| NLR ≥3 | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.05 | 1.01 | 1.09 | 0.02 | 2.21 | 0.65 | 2.24 | 0.03 |

| No | 1.05 | 0.96 | 1.14 | 0.25 | 1.10 | 0.85 | 1.25 | 0.48 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; F, female; M, male; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Discussion

The identification of prognostic indicators and predictive markers related to the clinical evolution of lung cancer (LC) is extremely relevant, since the disease stands as number one in regards to patient mortality and incidence worldwide (1). Our study revealed that LC patients treated with nivolumab who showed high baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and were underweight had a significantly lower progression-free survival (PFS) rate and that overweight/obese patients had a prolonged PFS rate. Furthermore, independently, patients who presented NLR ≥3 and those of male sex had a poor prognosis, while normal weight and overweight/obese patients had a better prognosis. Ultimately, we managed to develop a significant statistical model, a new predictive score for PFS, based on the association between NLR, body mass index (BMI) and male sex.

It is known that cancer-associated inflammation plays an important role in disease progression and survival in a variety of solid tumors (12), while the absence of inflammation could favor outcomes, even though, in this situation, tumors could develop unnoticed (13,14). Accordingly, NLR, as an indicator of systemic inflammation associated with alterations in peripheral blood leukocytes, could play a significant role in various cancers and it has been extensively studied in this matter (6,15). An integral part of the innate immune system is represented by neutrophils, with both immune-suppressive and tumor-promoting roles being described (16-20). Beside the fact that neutrophils produce chemokines and cytokines that influence tumor progression, they can also suppress the immune activity of lymphocytes to further promote metastasis (21-23). Lymphocytes have been proven to exhibit a vital role in host cell-mediated immune regulation and their increased infiltration into tumors has been linked with a better response to cytotoxic treatment and progression in cancer patients (24,25). Furthermore, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) have been shown to have prognostic significance in cancer clinical outcomes (26,27). Considering that immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) block negative regulators of T-cell function, thus enhancing antitumor immunity (28), an alteration in peripheral blood leukocytes in favor of neutrophils, with a commonly associated lymphopenia, could influence the efficacy of ICIs. Bagley et al demonstrated that higher pretreatment NLR in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with nivolumab was independently associated with lower PFS and overall survival (OS) (29). However, the pre-specified cut-off value for NLR used in this study was 5, based on the validation of a previous study that assessed patients with metastatic melanoma treated with ipilimumab (30). Conversely, in an Asian cohort, Nakaya et al did not report a significant association between baseline NLR and median PFS, but revealed that a NLR <3 at 2 and 4 weeks after nivolumab initiation may be an independent predictive indicator in patients with advanced NSCLC (31). In the present study, high pretreatment NLR was associated with lower PFS and a poor outcome.

BMI has also become a subject of interest in the context of clinical outcomes of cancer patients. It is considered to be the second highest risk factor after tobacco smoking, causing approximately 20% of the number of cancer cases (32). Moreover, studies have found that obesity is associated with lower survival and poorer cancer treatment response (32-35), until in the recent years, when the ‘obesity paradox’ was described, a phenomenon which suggests a protective effect increased BMI has in chronic diseases, including cancer (36-39). Furthermore, since the development of ICIs, there is growing evidence that highlights a connection between high BMI and a better response to immunotherapy and improved cancer survival, with the evidence by Naik et al that improved OS was associated in male patients who had high serum creatinine levels (a marker for high muscle mass) (8,9). A separate study that analyzed individual participant data from 4 different clinical trials found a linear connection between increased BMI and improved survival in patients with NSCLC treated with atezolizumab (an anti-PD-L1). In comparison, the same connection was not found in the groups treated with the chemotherapy agent docetaxel (40). The present study adds to the evidence that high BMI may improve PFS and response to immunotherapy. In addition, despite the small number of underweight patients, the results of our study showed that this category presented a significantly lower PFS, intersecting with what Cortellini et al revealed in their retrospective observational study, which included NSCLC patients receiving ICIs (41).

The biological basis that stands between the association of BMI and cancer survival following immunotherapy is just at the beginning of understanding. The obese state induces a low-grade systemic inflammation and an impaired immune response, including T-cell dysfunction and a growing number of exhausted PD-1-presenting T-cells in adipose tissue and tumor microenvironment via a leptin-dependent mechanism, which are known to have a strong affinity for PD-L1, a ligand located on tumor cells, meant to further suppress T-cell function (7). Based on this hypothesis, nivolumab, which acts as an anti-PD-1 antibody, blocking the bonding between PD-L1/PD-1 molecules, might induce a better response in patients with increased BMI and an established PD-1 T-cell exhausted state.

Despite not being the main aim of the present study, our statistical analysis revealed that the male sex may represent a poor predictive factor for PFS, a fact that proves to be inconsistent with other studies that showed variation in ICI outcomes related to sex (10,42,43). At the same time, according to univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis, male sex, NLR and BMI were found to be associated with PFS. Consequently, we proposed a new predictive score for PFS. PFS-NSCLC Score has the ability to rule-out the poor outcome at a cut-off value of more than 1.32 with a specificity of 90.4% and a negative predictive value of 95.7%.

Nevertheless, our study has its limitations. The number of patients in our cohort was relatively moderate with a few disproportions regarding baseline characteristics, such as sex, NLR and nutritional status distributions. In addition, being a retrospective study, we did not use any of the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) methodologies and the expression of PD-L1 was examined only in a few patients, because of insurance policy constraints and succession of treatments. Despite these limitations, we managed to set a new NLR cut-off value (3.26) for predicting PFS, which resembles the one used in previous literature (11). In addition, new cut-off values were calculated for NLR after 2 and 4 weeks after the initiation of nivolumab (NLR2=3.26, NLR4=3.49, respectively). Regarding the proposed predictive score for PFS, the performance in the present study appears to be good and, to our knowledge, this type of tool is the first one to be proposed. We consider our study significant, as the power of the test was 75%. However, more research is required, with larger populations and specific characteristics.

In conclusion, NLR and BMI may represent simple and useful biomarkers and, by combining them and taking into consideration the male sex, they may predict PFS in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with nivolumab.

Acknowledgements

Professional editing, linguistic and technical assistance were performed by Irina Radu, Individual Service Provider.

Funding Statement

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

RD and RL organized the study, analyzed and interpreted the study data and wrote the manuscript. ASD, AN, SS, DP and MS analyzed the data and helped to draft the findings and critically reviewed the manuscript; SN interpreted the data and critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients provided written informed consent for the study participation and data collection. The study protocol was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki after the approval by OncoHelp Oncology Center's Ethics Committee (no. 1b/27.04.2020).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Lung cancer. Available at: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx. Accessed June 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inamura K. Lung cancer: Understanding its molecular pathology and the 2015 WHO classification. Front Oncol. 2017;7(193) doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onoi K, Chihara Y, Uchino J, Shimamoto T, Morimoto Y, Iwasaku M, Kaneko Y, Yamada T, Takayama K. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer treatment: A review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(1362) doi: 10.3390/jcm9051362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malhotra J, Jabbour SK, Aisner J. Current state of immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2017;6:196–211. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2017.03.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han F, Liu Y, Cheng S, Sun Z, Sheng C, Sun X, Shang X, Tian W, Wang X, Li J, et al. Diagnosis and survival values of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and red blood cell distribution width (RDW) in esophageal cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2019;488:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Šeruga B, Vera-Badillo FE, Aneja P, Ocaña A, Leibowitz-Amit R, Sonpavde G, Knox JJ, Tran B, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(dju124) doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodall MJ, Neumann S, Campbell K, Pattison ST, Young SL. The effects of obesity on anti-cancer immunity and cancer immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(1230) doi: 10.3390/cancers12051230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortellini A, Bersanelli M, Buti S, Cannita K, Santini D, Perrone F, Giusti R, Tiseo M, Michiara M, Di Marino P, et al. A multicenter study of body mass index in cancer patients treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors: When overweight becomes favorable. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(57) doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0527-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naik GS, Waikar SS, Johnson AE, Buchbinder EI, Haq R, Hodi RS, Schoenfeld JD, Ott PA. Complex inter-relationship of body mass index, sex and serum creatinine on survival: Exploring the obesity paradox in melanoma patients treated with checkpoint inhibition. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(89) doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0512-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McQuade JL, Daniel CR, Hess KR, Mak C, Wang DY, Rai RR, Park JJ, Haydu LE, Spencer C, Wongchenko M, et al. Association of body-mass index and outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or chemotherapy: A retrospective, multicohort analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:310–22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30078-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozyurek BA, Ozdemirel TS, Ozden SB, Erdogan Y, Kaplan B, Kaplan T. Prognostic value of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in lung cancer cases. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:1417–1421. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.5.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fouad TM, Kogawa T, Liu DD, Shen Y, Masuda H, El-Zein R, Woodward WA, Chavez-MacGregor M, Alvarez RH, Arun B, et al. Erratum: Overall survival differences between patients with inflammatory and noninflammatory breast cancer presenting with distant metastasis at diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;152:407–416. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3477-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faur CI, Pop DL, Motoc AGM, Folescu R, Grigoraş ML, Gurguş D, Zamfir CL, Iacob M, Vermeşan D, Deleanu BN, et al. Large giant cell tumor of the posterior iliac bone-an atypical location. A case report and literature review. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2020;61:247–252. doi: 10.47162/RJME.61.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guthrie GJ, Charles KA, Roxburgh CS, Horgan PG, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: Experience in patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88:218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hao S, Andersen M, Yu H. Detection of immune suppressive neutrophils in peripheral blood samples of cancer patients. Am J Blood Res. 2013;3:239–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pillay J, Kamp VM, van Hoffen E, Visser T, Tak T, Lammers JW, Ulfman LH, Leenen LP, Pickkers P, Koenderman L. A subset of neutrophils in human systemic inflammation inhibits T cell responses through mac-1. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:327–336. doi: 10.1172/JCI57990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pillay J, Tak T, Kamp VM, Koenderman L. Immune suppression by neutrophils and granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells: Similarities and differences. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:3813–3827. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1286-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uribe-Querol E, Rosales C. Neutrophils in cancer: Two sides of the same coin. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015(983698) doi: 10.1155/2015/983698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cools-Lartigue J, Spicer J, Najmeh S, Ferri L. Neutrophil extracellular traps in cancer progression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:4179–4194. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1683-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galdiero MR, Garlanda C, Jaillon S, Marone G, Mantovani A. Tumor associated macrophages and neutrophils in tumor progression. J Cell Physiol. 2013;228:1404–1412. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coffelt SB, Kersten K, Doornebal CW, Weiden J, Vrijland K, Hau CS, Verstegen NJ, Ciampricotti M, Hawinkels LJ, Jonkers J, de Visser KE. IL-17-producing γδ T cells and neutrophils conspire to promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2015;522:345–348. doi: 10.1038/nature14282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fridlender ZG, Albelda SM, Granot Z. Promoting metastasis: Neutrophils and T cells join forces. Cell Res. 2015;25:765–766. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gooden MJ, de Bock GH, Leffers N, Daemen T, Nijman HW. The prognostic influence of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in cancer: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:93–103. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarraf KM, Belcher E, Raevsky E, Nicholson AG, Goldstraw P, Lim E. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and its association with survival after complete resection in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:425–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geng Y, Shao Y, He W, Hu W, Xu Y, Chen J, Wu C, Jiang J. Prognostic role of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37:1560–1571. doi: 10.1159/000438523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeng DQ, Yu YF, Ou QY, Li XY, Zhong RZ, Xie CM, Hu QG. Prognostic and predictive value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for clinical therapeutic research in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:13765–13781. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bagley SJ, Kothari S, Aggarwal C, Bauml JM, Alley EW, Evans TL, Kosteva JA, Ciunci CA, Gabriel PE, Thompson JC, et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a marker of outcomes in nivolumab-treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2017;106:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrucci PF, Gandini S, Battaglia A, Alfieri S, Di Giacomo AM, Giannarelli D, Cappellini GC, De Galitiis F, Marchetti P, Amato G, et al. Baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with outcome of ipilimumab-treated metastatic melanoma patients. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:1904–1910. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakaya A, Kurata T, Yoshioka H, Takeyasu Y, Niki M, Kibata K, Satsutani N, Ogata M, Miyara T, Nomura S. Neutrophil-To-Lymphocyte ratio as an early marker of outcomes in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23:634–640. doi: 10.1007/s10147-018-1250-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolin KY, Carson K, Colditz GA. Obesity and cancer. Oncologist. 2010;15:556–565. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Pergola G, Silvestris F. Obesity as a major risk factor for cancer. J Obes. 2013;2013(291546) doi: 10.1155/2013/291546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reeves GK, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J, Spencer E, Bull D. Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the million women study: Cohort study. BMJ. 2007;335(1134) doi: 10.1136/bmj.39367.495995.AE. Million Women Study Collaboration. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vucenik I, Stains JP. Obesity and cancer risk: Evidence, mechanisms, and recommendations. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2012;1271:37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tobias DK, Pan A, Jackson CL, O'Reilly EJ, Ding EL, Willett WC, Manson JE, Hu FB. Body-Mass index and mortality among adults with incident type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:233–244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1401876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersen KK, Olsen TS. The obesity paradox in stroke: Lower mortality and lower risk of readmission for recurrent stroke in obese stroke patients. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:99–104. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curtis JP, Selter JG, Wang Y, Rathore SS, Jovin IS, Jadbabaie F, Kosiborod M, Portnay EL, Sokol SI, Bader F, et al. The obesity paradox: Body mass index and outcomes in patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2005;168:55–61. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.1.55. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silva TH, Schilithz AO, Peres WAF, Murad LB. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and nutritional status are clinically useful in predicting prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Nutr Cancer. 2020;72:1345–1354. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2019.1679198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kichenadasse G, Miners JO, Mangoni AA, Rowland A, Hopkins AM, Sorich MJ. Association between body mass index and overall survival with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:512–518. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.5241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cortellini A, Bersanelli M, Santini D, Buti S, Tiseo M, Cannita K, Perrone F, Giusti R, De Tursi M, Zoratto F, et al. Another side of the association between body mass index (BMI) and clinical outcomes of cancer patients receiving programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1)/Programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) checkpoint inhibitors: A multicentre analysis of immune-related adverse events. Eur J Cancer. 2020;128:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallis CJD, Butaney M, Satkunasivam R, Freedland SJ, Patel SP, Hamid O, Pal SK, Klaassen Z. Association of patient sex with efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors and overall survival in advanced cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:529–536. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sagerup CMT, Småstuen M, Johannesen TB, Helland A, Brustugun OT. Sex-Specific trends in lung cancer incidence and survival: A population study of 40 118 cases. Thorax. 2011;66:301–307. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.151621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.