Abstract

Background

Maternal depression has a recurring course that can influence offspring outcomes. There is limited evidence about how to treat maternal depression to improve longer term maternal outcomes and reduce intergenerational transmission of psychopathology using task-shifted, low-intensity scalable psychosocial interventions. We sought to fill this gap, evaluating the effects of a peer-delivered psychosocial depression intervention on maternal depression and child development at 3 years of age.

Methods

Forty village clusters in Pakistan were randomly allocated to treatment or enhanced usual care (EUC). Pregnant women aged 18 years or over screening positive for moderate or severe depression symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) score 10+) were recruited into the trial (n=570) and a non-depressed cohort was also enrolled (n=584). Primary outcomes were maternal depression symptoms and remission (PHQ-9<10) and child socioemotional skills (Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire- Total Difficulties (SDQ-TD)/. Analyses were intention-to-treat. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT02658994.

Findings

At 36-months postnatal, complete data were available from 889 mother-child dyads: 206 treatment (72.5%), 216 EUC (75.3%), and 467 prenatally non-depressed (80.0%). We did not observe significant outcome differences between treatment and EUC arms of the trial (PHQ-9 total score: Standardized Meand Difference = −0.13, 95% CI −0.33 to 0.07; PHQ-9 remission: RR= 1.08, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.33; SDQ-TD treatment estimate: −0·10; 95%CI −1·39, 1·19;). Approximately 40% of women did not complete their treatment sessions, and competence levels of peers dropped over time.

Interpretation

Reduced symptom severity and high remission rates were seen across both arms, possibly masking any treatment effects. A multi-year, psychosocial interventions can be task-shifted via peers but are susceptible to reductions in fidelity and dosage over time. Early intervention efforts might need to rely on multiple models (e.g. collaborative care), be of greater intensity, and potentially targeted toward higher risk mothers to reduce the intergenerational transmission of psychopathology from mothers to children.

Introduction

Global prevalence estimates of depression in the perinatal period range from 4% to over 50%, with the highest burden in low-resource settings, making depression a public health priority.1 In addition to the effect of maternal depression on the woman’s functioning, physical health, and risk of suicide, observational evidence suggests that maternal depression is associated with higher risk of multiple negative child outcomes, including stunting, socioemotional difficulties, problems with school readiness and performance, and depressive symptoms over their lifecourse.1,2 Women experiencing perinatal depression are at much higher risk of subsequent or recurrent episodes of depression and this chronic or episodic depression is most deleterious for numerous maternal and child outcomes.3,4 This risk of intergenerational transmission of psychopathology is most heavily borne by poorer families and those in low resource settings with limited access to quality healthcare, thus exacerbating economic and social inequality.3

Because of the lack of specialists in many LMIC settings, task shifting for maternal depression is necessitated to bridge the treatment gap. Evidence-based, task-shifted, targeted maternal depression or universal psychosocial interventions can be delivered through community health workers as well as lay peers.5,6 However, most of these interventions are delivered either during pregnancy or in the early postnatal months, focusing on the acute phase of maternal depression, without tackling issues of recurrence and chronicity. To our knowledge no depression interventions that begin prenatally are designed specifically to prevent recurrence after the perinatal period. Hence, the extent to which such interventions can break the cycle of recurrence of depression beyond the first postnatal year remains unknown.

While interventions have demonstrated efficacious reductions in shorter term (i.e. 12 months or less) maternal depression and improved maternal behaviours,7 we do not know whether such interventions can reduce intergenerational transmission to children. Many depression interventions in the perinatal period include a child development component, opening the possibility that such depression interventions, including the one studied here, may affect child outcomes through pathways that are independent of changes in depression symptoms themselves. While maternal depression interventions have been shown to improve key parenting practices,8 evidence of long-term effects on child socioemotional development is scarce.9 Studies showing improved child outcomes have short post-intervention follow-up periods, typically less than 12 months,10–12 leaving uncertainty about longer lasting program impacts. The few studies with follow-up longer than one year have reported mixed or even incongruent effects.4,6,13,14 For example, analysis of the subset of women who were depressed when beginning the Philani+ program in South Africa, which broadly focused on improving child outcomes and lasted through 6 months postnatally, showed improved child physical and cognitive outcomes at 18 months but higher levels of aggression at 5 years of age.6,15 The challenges of differential attrition in longer-term follow-ups, diminishing sample sizes, and heterogeneous responses among particular sub-groups (such as those exposed to poverty or intimate partner violence) make clear conclusions difficult.2,14

The Thinking Healthy Program, Peer-delivered (THPP), delivered individual and group sessions from pregnancy to 6 months postnatal and has been evaluated through two randomized controlled trials, one in Pakistan and one in India.16–18 Although the country specific findings were weak, the pooled analyses of these trials showed greater recovery from perinatal depression among the intervention group at 6 months postnatal. It also showed that delivering this psychosocial intervention through peers was a cost-effective, feasible and acceptable approach.16

We evaluate a 3-year, task-shifted psychosocial peer-delivered intervention for maternal depression, Thinking Healthy Program, Peer-delivered Plus (THPP+),19 that followed up on the THPP, in rural Pakistan, a low resource context characterized by high levels of maternal depression and limited access to clinical mental healthcare.20

Although our hypothesis was that the children in the intervention arm will be less high risk, the full impact of the intervention can only be discerned if we know the level of excess risk remaining- that is, the difference between the reduced level of risk among children (of prenatally depressed mothers) in the intervention arm and the risk among children whose mothers were not depressed. If outcomes of these two groups are comparable, we can infer that the intervention is capable of preventing the intergenerational transmission of risk. To achieve this we gathered data on women who were not depressed in pregnancy. The resulting pregnancy-birth cohort of both prenatally depressed (trial participants) and non-depressed women is referred to as the Bachpan Cohort (Bachpan means Childhood in the local Urdu language). Finally, we examined whether intervention effects differ by key social contextual factors such as socioeconomic status and intimate partner violence.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a stratified cluster-randomized controlled trial in Kallar Syedan, a rural subdistrict of Rawalpindi, Pakistan. The sub-district is a socioeconomically deprived area with poverty rates around 50%, female literacy of 40–45%, and a high fertility rate (3·8 births per woman).21 It is primarily agrarian with close knit communities co-residing in large households (average 6·2 people per household). The sub-district has 11 Union Councils (UC), the smallest administrative unit, each with a population of about 22,000–25,000. Each UC is serviced by a Primary Health Care Facility which houses a physician, midwife, vaccinator, dispenser, and village-based Lady Health Workers (LHWs).

This trial maintained the original cluster criterion, randomization sequence and procedures under the previous trial.16,22 Pregnant women in the 3rd trimester, aged 18+ years and registered with their LHWs, were eligible. Approximately 95% of the women in the study area were registered with LHWs. All pregnant women were approached by trained research staff either within the pregnant woman’s residence or that of their LHW and, if they consented, were assessed. Women who needed immediate medical or psychiatric inpatient care were excluded from the study. All eligible women were invited to be screened for depression using the Urdu version of the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), which has been used extensively as a screening tool in the study setting and has an acceptable criterion validity and reliability for this population.23 Women screening positive (PHQ-9 score ≥ 10) were eligible for enrolment into the trial and follow-up as part of the Bachpan Cohort.16 One out of every three women who screened with a < 10 score on PHQ were enrolled to participate in the Bachpan Cohort only, resulting in a roughly equal size of prenatally non-depressed and depressed women at the beginning the cohort.24

Randomization and masking

The trial was conducted at a sub-district level. Forty village-clusters (population of 2,400 to 3,600) were the unit of randomization and were geographically separate to minimize contamination risk. The subdistrict is administratively subdivided into 11 Union Councils (as explained above and, within each of these 11 union councils, we identified an even number of village clusters to ensure that equal numbers of clusters are randomized into intervention or control condition (ie 1:1 ratio) by an independent statistician using a computerized randomization sequence. Research teams responsible for identifying, obtaining consent and recruiting trial participants were blind to the allocation status. The trial PI, site PIs/coordinators, trial statisticians, and members of the Trial Steering Committee were blinded to the allocation status until the analysis of the six-month data for the initial THPP trial.25

The Thinking Healthy Program, Peer-delivered Plus (THPP+) Intervention

The intervention arm received the longer-duration peer-delivered psychosocial intervention (THPP+). It consisted of 18 group-based “booster” sessions (from 7th to 36th month postnatal). Of these, the first 6 sessions were delivered monthly, then bi-monthly until 36 months. These sessions built on the shorter duration intervention and were delivered by the same peers. The peers were lay married women who lived in the same community as that of the depressed women and volunteered their time.

The key features of this psychosocial intervention, delivered by non-specialists, were peer-support, behavioural activation, and problem-solving in a culturally sensitive, non-medicalized format, and developmental activities for children up to the 36th month (See Appendix p.1–3 for the overall structure of the intervention and peer characteristics.19 A cascaded model of training and supervision was used which included frequent competence assessments.26 A competency checklist was used for supervision, including direct observation of the peers, and to provide feedback. Each peer received this assessment six times over the course of the program. During the feedback meetings, the supervisor discussed checklist information along with session logs maintained by the peers. Competence was assessed through observations and the checklist captured whether content was delivered as intended. Refresher trainings were done 6 and 18 months after the initial training. The two-day training included re-orientation to the intervention and its principles, as well as training on materials and use of job aids.

The intervention group sessions provided a safe environment for women to voice their problems, share experiences of childcare, and provide support to women. Peer volunteers were trained to use culturally grounded vignettes that served as tools to deliver health and well-being messages. The sessions aimed for maternal well-being but also child-care and development by encouraging mother-infant interaction and play. The intervention provided examples of age-appropriate activities, derived from the UNICEF/WHO’s Care for Development Package and encouraged demonstration of these activities during the sessions. While these ‘booster’ group sessions did not focus on specific strategies to address depression, the peer could still draw on her prior knowledge and skills of specific psychotherapeutic elements such as behavioural activation when required. Additional details of the intervention are reported elsewhere.19,26 We defined overall treatment completion as attending 10 (out of 14) sessions from pregnancy through 6 months postnatal (Phase 1: THPP, individual and group sessions) and 12 (out of 18) sessions from 7 to 36 months postnatal (Phase 2: THPP+, booster group sessions).

Both intervention and control arms received Enhanced Usual Care (EUC). No treatment was offered to the prenatally non-depressed women in either of the arms. EUC consisted of informing participants about their depression status and ways to seek help for it, informing their respective LHWs about women’s depression status at enrollment, training all the 11 primary care facility-based physicians in the subdistrict on the mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) treatment guidelines for maternal depression,27 and providing depressed participants with a leaflet on how and where to seek appropriate health care during pregnancy and beyond.

Procedures

Assessments were conducted 6 times over the course of the study (in pregnancy, and 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months postnatal). As originally specified, the current analysis utilizes mother and child outcome data at 36 months.22All measures were extensively piloted. Assessments were done at the community level within households of women by trained interviewers blind to the allocation status, all questions were interviewer administered. Assessors inter-rater reliability was ensured through classroom-based training which included role plays, followed by field practice sessions. During these sessions each pair of assessors assessed up to 10 participants jointly and discussed their coding on each item to establish inter-rater reliability prior to start of actual data collection.

The project received approval for the IRBs of Human Development Research Foundation (HDRF), Duke University, and University of North Carolina. The study protocol for the effectiveness trial of THPP+ and inclusion of prenatally non-depressed pregnant women in the Bachpan Cohort study has been published previously.16,22

Outcomes

The primary maternal outcome was depression symptoms assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and analyzed as symptom severity (total score) and remission (score < 5). The secondary maternal outcomes were disability assessed using WHO’s Disability Assessment Schedule, WHO-28DAS, and current major depressive episode based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) Disorders.29 Process data regarding THPP+ sessions attended, competence scores of peers, duration of sessions, and peers’ supervision attendance are described elsewhere30 and in the appendix (p.4–8).

The primary child outcome was child socioemotional development measured using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, Total Difficulties (SDQ-TD) score. The SDQ is a parent-reported measure of 25 child attributes with five subscales: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and prosocial behavior.31 The Total Difficulties (TD) score is calculated based on four subscales (omitting prosocial behaviour) with a score range of 0–40 points. The SDQ is widely used in low- and middle-income countries and has been translated into Urdu32; in our sample, internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78.

The secondary child outcomes were two developmental domains. Given language differences, two subscales from the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, 3rd edition (BSITD III) were selected to assess achievement of developmental milestones, the Receptive Language and Fine Motor subscales.33 The BSITD was administered in the family’s home; scaled scores were calculated using the child’s chronological age. The BSITD has been widely used and validated internationally.34

An additional outcome of interest, child growth, was analysed using weight- and length-for-age Z-scores. Additional variables included demographic and psychosocial factors hypothesized to moderate the effect of the intervention. These included household assets as an indicator of socioeconomic status,35 maternal education (coded as none vs. any), household composition (nuclear family status), intimate partner violence (IPV) in the previous 12 months, child gender, maternal age (18–24 vs. 25+), number of siblings (0 vs. 1+), treatment expectations (very/moderately useful vs. somewhat/not useful), depression chronicity (<12 weeks vs. ≥12 weeks), and depression severity (PHQ-9 10–14 vs. 15+).23,36 We collected information on a number of domains that may have been differentially distributed across the treatment and EUC arms or correlated with loss to follow-up (table 1 and Appendix p.9–14).

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of women in study population (n=1154)

| Characteristics | Control Arm (EUC) (N = 287) N (%) or mean (SD) | Intervention Arm (THPP/THPP+) (N = 283) N (%) or mean (SD) | Prenatally Non-depressed (N = 584) N (%) or mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age | 27.29 (4.97) | 26.80 (4.60) | 26.37 (4.26) |

| 18–24 | 83 (28.9%) | 88 (31.1%) | 203 (34.8%) |

| 25+ | 204 (71.1%) | 195 (68.9%) | 381 (65.2%) |

| Mother's Education (in years) | |||

| None (0) | 55 (19.2%) | 52 (18.4%) | 63 (10.8%) |

| Primary (1–5) | 71 (24.7%) | 68 (24.0%) | 87 (14.9%) |

| Middle/Secondary (6–12) | 134 (46.7%) | 145 (51.2%) | 338 (57.9%) |

| Tertiary (13+) | 27 (9.4%) | 18 (6.4%) | 96 (16.4%) |

| Mother's Education (in years) | |||

| None (0) | 55 (19.2%) | 52 (18.4%) | 63 (10.8%) |

| Any (1+) | 232 (80.8%) | 231 (81.6%) | 521 (89.2%) |

| Nuclear Family | 49 (17.1%) | 50 (17.7%) | 59 (10.1%) |

| Total Number of Children in the Household | 2.97 (2.67) | 3.09 (2.71) | 2.51 (2.63) |

| Number of Children | |||

| First pregnancy | 72 (25.1%) | 65 (23.0%) | 212 (36.3%) |

| 1 to 3 | 183 (63.8%) | 180 (63.6%) | 336 (57.5%) |

| 4+ | 32 (11.1%) | 38 (13.4%) | 36 (6.2%) |

| SCID (MDE) | 210 (73.2%) | 218 (77.0%) | 14 (2.4%) |

| PHQ-9 Total Score | 14.48 (3.58) | 14.89 (3.72) | 2.80 (2.46) |

| Severity (PHQ-9 score) | |||

| 10–14 | 167 (58.2%) | 145 (51.2%) | 584 (100.0%) |

| ≥15 | 120 (41.8%) | 138 (48.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| MSPSS Total Score | 3.95 (1.33) | 3.92 (1.41) | 4.97 (1.01) |

| WHO-DAS Total Score | 16.11 (9.12) | 16.71 (8.52) | 5.61 (6.46) |

| Duration of Depression (Chronicity) | |||

| <12 weeks | 38 (13.2%) | 35 (12.4%) | |

| ≥12 weeks | 155 (54.0%) | 171 (60.4%) | N/A |

| missing | 94 (32.8%) | 77 (27.2%) | |

| SES (Assets) | |||

| Lowest Quintile | 74 (25.8%) | 85 (30.0%) | 71 (12.2%) |

| Lower Middle Quintile | 67 (23.3%) | 71 (25.1%) | 93 (15.9%) |

| Middle Quintile | 55 (19.2%) | 50 (17.7%) | 126 (21.6%) |

| Upper Middle Quintile | 47 (16.4%) | 39 (13.8%) | 145 (24.8%) |

| Upper Quintile | 44 (15.3%) | 38 (13.4%) | 149 (25.5%) |

| SES (Assets index) | |||

| Bottom 1/3rd | 109 (38.0%) | 119 (42.0%) | 113 (19.3%) |

| Top 2/3rds | 178 (62.0%) | 164 (58.0%) | 471 (80.7%) |

| Number of people per room | 2.47 (1.87) | 2.79 (2.03) | 2.22 (1.79) |

| Life Events Checklist Score | 4.10 (2.33) | 4.70 (2.44) | 2.90 (2.16) |

| Any IPV (last 12 months) | 165 (59.1%) | 178 (65.4%) | 179 (33.0%) |

| Treatment Expectations | |||

| None/somewhat | 76 (26.5%) | 70 (24.7%) | N/A |

| Moderate/very | 211 (73.5%) | 213 (75.3%) | N/A |

Statistical analyses

For mother outcomes, anticipating a sample of 480 prenatally depressed women, we were powered at 90% to detect a remission rate of 65% in the prenatally depressed-intervention versus 45% in prenatally depressed-control at the two-tailed 5% significance level and assuming a conservative ICC of 0.07 in intervention arm and 0.05 in control.22 For child outcomes, with the sample sample size, we were powered at 90% to detect a difference between treatment arms of 3 points on the SDQ-TD at the two-tailed 5% significance level assuming a standard deviation of 5.2 points and ICC of 0.04–0.08.22 We were also well-powered to test for equivalence of SDQ-TD score between children of prenatally depressed mothers in the treatment arm and children of prenatally non-depressed mothers in the EUC arm, with equivalence defined as the 95% confidence interval of the mean difference being between −2 and 2 units.22

Statistical analyses were done according to the CONSORT guidelines in Stata software version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and SPSS. All analyses compare the three groups (prenatally depressed in intervention, prenatally depressed in control, and prenatally non-depressed) across the two arms, using the 36-month outcomes. We had pre-specified a comparison of outcomes between intervention and control arms within the prenatally non-depressed women and, in the absence of such an effect, present results for the overall prenatally non-depressed cohort.

The primary analyses were designed as intention-to-treat. Data from prenatally depressed and non-depressed participants were analyzed jointly using linear mixed effects models so that all comparisons of interest could be estimated from the same model. The identity link was used for continuous outcomes to estimate differences in mean outcomes. Standardized mean differences (SMDs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained using the method of Hedges.37 In the primary model, we included a random intercept for cluster and fixed effects for treatment arm (depressed intervention, depressed control, non-depressed), union council (11 levels; the stratification variable), and variables found to be imbalanced by loss to follow-up or at baseline (determined using p<0.10; see Appendix p.9–14). Mixed models assume missing at random, since we include baseline data in the model and adjusting for variables lost to follow-up will help account for missing data. We used restricted maximum likelihood (REML). The between-within method was used to apply small-sample bias corrections to the intervention effect standard errors in the mixed effects framework.38 These models also generated the intra-cluster correlation (ICC) values.

All binary outcomes were analyzed using generalized estimating equations (GEE). As with the continuous outcomes, we include as fixed effects treatment arm and union council, as well as fixed effects for any variables found to be imbalanced by loss to follow-up or at baseline. In the GEE framework, we took into account clustering using an exchangeable working correlation matrix. We used a modified Poisson approach39 and Kauermann-Carroll bias-corrected standard errors to account for the relatively small number of clusters (i.e. 40).40 When analyzing SCID major depressive episode, we included SCID at all time points as the outcome in a GEE model with exchangeable working correlation for village cluster. Additional analyses focus on a priori identified potential moderators of any main associations with the primary outcomes (described above). We tested for moderation of the intervention effect by including these potential moderators in the model as individual interaction terms.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02658994 (registered on 21 January 2016).

Role of Funding Source

The Funding Source (NIH) had no influence in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding authors had full access to all of the data and the final responsibility to submit for publication.

Results

From Oct 15, 2014 to Feb 25, 2016, we identified and randomly selected 40 village clusters out of 46 and randomly assigned 20 village clusters each to intervention (THPP+) and control (EUC) arms. In all we approached 1910 pregnant women; 287 prenatally depressed women in the control arm and 283 in the intervention arm completed the baseline questionnaire. Of the prenatally non-depressed women approached, 584 were enrolled, yielding comparable numbers of prenatally depressed and prenatally non-depressed women in each of the 40 village clusters.

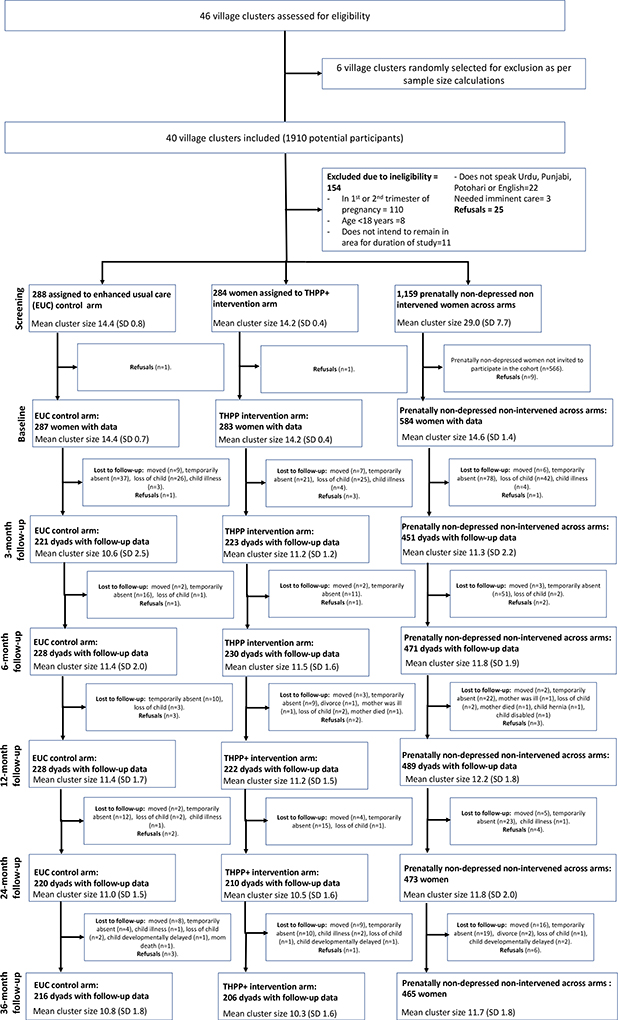

Of the 1,154 participants enrolled at baseline, 889 (77.0%) were successfully interviewed at 36 months: 206 (72.5%) intervention, 216 (75.3%) EUC, and 467 (80.0%) prenatally non-depressed (Figure 1). There was no differential loss to follow up by treatment arm and no differences in adverse events (Appendix p.9–14).

Figure 1.

CONSORT sample flow chart

At baseline, the mean age of the women in the sample was 26.7 (SD: 4.5) years, with 30.2% of women being in their first pregnancy. The mean PHQ-9 scores across the treatment arms were similar (14.5 control and 14.9 intervention) with a mean score of 2.8 among prenatally non-depressed women. Further baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. At 36 months, 49.6% of the infants were girls.

Baseline variables that were imbalanced between intervention and control groups include the life events checklist score with a higher mean score in the intervention arm. Other variables were found to be imbalanced but were not included because of collinearity or conceptual overlap (e.g. subjective religiosity). Additional baseline demographic variables that were associated with loss to follow-up at 36 months and adjusted for include number of people per room, child’s grandmother living with him/her, nuclear family status, number of living children and the asset score.

Just over two-thirds of prenatally depressed women in the intervention arm completed the THPP+ intervention (Appendix p.5). Only 63% of women completed treatment during Phase 2 compared to nearly 80% treatment completion in Phase 1. The competence levels of the peers declined over the implementation period, particularly in the period after time point 3 (i.e. at 12 months postnatal) where we introduced new content for the booster sessions and the frequency of peer supervisions dropped from monthly to every two months (appendix p.6–8) show high and low scoring peers and their competence levels over time

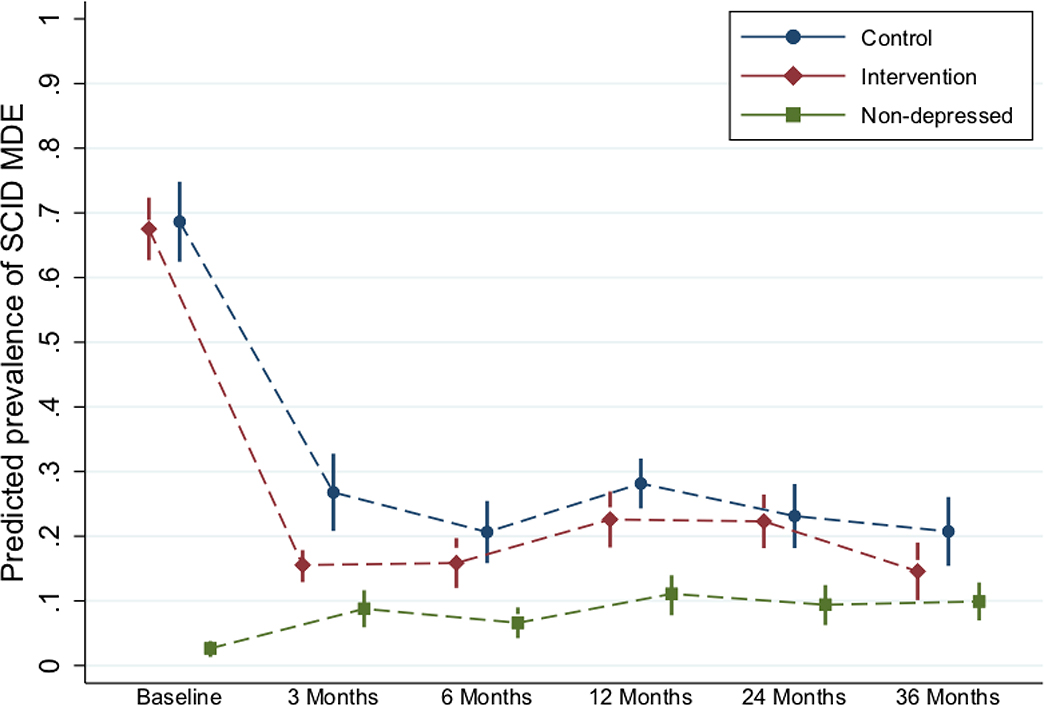

For all prenatally depressed women, depression scores dropped meaningfully, regardless of their arm allocation (Figure 2). There were no significant differences in depression outcomes between arms (THPP+ vs EUC) at 36 months postnatal (Table 2). The adjusted standardized mean difference (SMD) in depressive symptom severity (PHQ-9) between arms was −0.13 (95% CI −0.33 to 0.07) and the risk ratio (RR) for depression remission (PHQ-9<10) was 1.00 (95% CI 1.13 to 0.97). Turning to the secondary outcomes, we observed a relatively larger difference between arms on the secondary outcomes of SCID-based major depressive episode at 36 months (22% control vs 16.5% intervention) (RR=0.67, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.05). The intervention effects on disability (SMD=−0.12, 95% CI −0.33 to 0.09) were not statistically significant.

Figure 2: Depressive episodes (recurrence) across time points and comparison groups.

Note: *Abbreviations: SCID – Structured Clinical Interview for Depression; MDE – Major Depressive Episode.

**Predicted prevalences come from a longitudinal GEE model with SCID at all time points as the outcome. Time point, intervention arm (depressed in intervention, depressed in control, and non-depressed), and the interaction between these two variables are included in the model. In addition, the model is adjusted for the variables imbalanced at baseline or differential by missingness at any time point (see footnote to Table 3). An exchangeable working correlation matrix is used to take into account clustering by village cluster. Marginal predicted prevalences are computed from this model—at the average of continuous adjustors and the population percentages of categorical adjustors—and these are graphed by intervention arm.

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary maternal and child trial outcomes at 36 months postnatal

| Control Arm (EUC) (N=216) mean (SD) or N (%) | Intervention Arm (N=206) mean (SD) or N | Non-depressed (N=467) mean (SD) or N (%) | Adjusted Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) or adjusted RR (95% CI) for (%) Intervention vs Control arm | ICC* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRIMARY OUTCOMES | |||||

| Maternal PHQ-9 score | 6.48 (6.25) | 5.84 (5.80) | 3.44 (4.53) | SMD= −0.13 (−0.33, 0.07) | 0.009 |

| Remission: PHQ-9 < 10 score | 54 (75.0%) | 51 (75.2%) | 61 (86.9%) | 1.00 (0.88, 1.13) | <0.001 |

| Child SDQ-Total Difficulties | 14.72 (6.13) | 14.73 (6.04) | 13.69 (6.34) | −0.10 (−1.39, 1.19) | 0.020 |

| SECONDARY OUTCOMES | |||||

| Maternal Major Depressive episode (SCID) | 48 (22.2%) | 34 (16.5%) | 42 (9.0%) | RR= 0.67 (0.43, 1.05) | <0.001 |

| Maternal Disability (WHO-DAS) | 6.78 (9.44) | 5.87 (8.06) | 3.34 (6.19) | SMD= −0.12 (−0.33,0.09) | 0.018 |

| Child Bayley Scaled Receptive Score | 9.98 (2.60) | 10.42 (2.81) | 10.41 (2.79) | 0.38 (−0.19, 0.96) | 0.027 |

| Child Bayley Scaled Fine Motor Score | 11.38 (4.12) | 11.42 (4.05) | 11.31 (3.99) | 0.03 (−0.83, 0.90) | 0.039 |

PHQ-9: Patient Healthy Questionnaire; SDQ: Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; WHO-DAS: World Health Organization – Disability Assessment Schedule; SD: Standard Deviation; RR: Risk Ratio; ICC: Intra-cluster correlation.

ICC comes from the mixed models; for the binary outcomes the ICCs are based on mixed-effects logit models, although GEE was used to estimate the effects).

The prevalence of SCID-based major depressive episodes among the three groups of women: the prenatally depressed intervention arm, prenatally depressed control arm, and prenatally non-depressed women became increasingly similar in the proportion depressed by 36 months postnatal (figure 2). The THPP+ intervention arm showed higher convergence with the prenatally non-depressed women at 36 months compared to the control arm, so much so that there was not a statisticaly significant difference in the probability of being depressed (using SCID) between the intervention arm women (at 16.5%) and the prenatally non-depressed (9.0% of whom were depressed at 36 months, RR 0·74 (0·46 to 1·18).

We also examined intervention arm differences in depression severity (PHQ-9 scores) at 36 months postnatal by potential moderators assessed at baseline. There was no strong evidence of meaningful moderation of the intervention effect by any of these factors (Appendix p.18).

For the child primary outcome of SDQ-TD, the mean adjusted difference between treatment and control arms was −0·10; 95% CI −1·39 to 1·19 (Table 2). There were also no meaningful differences between the two arms in the secondary outcomes of Receptive Language and Fine Motor scores (from BSITD) (Table 2).

Similar to maternal depression results, we do not find strong support for the hypothesis that baseline characteristics moderated treatment effect on the SDQ-TD scores (Appendix p.19).

Children of prenatally non-depressed mothers had somewhat better SDQ-TD scores than the intervention or control arm children (e.g. SDQ-TD=13.7 among the children of the prenatally non-depressed vs. 14.7 in the intervention arm, p-value=0.07, Table 2). In other words, the prenatal depression episode predicted slightly worse SDQ-TD scores at 36 months of age, independent of the intervention. Exploratory analyses of the five sub-scales of the SDQ separately showed that this overall difference was driven by the hyperactivity and conduct problems sub-scales, with negligible differences by prenatal depression status for the peer problems, emotional problems, and the pro-social scales (Appendix p.19). As an example, the adjusted mean difference in the hyperactivity scores between the non-depressed and the control arm was 0·31 (95% CI −0·62, 0·01, ). The receptive language, fine motor and physical growth indicators did not meaningfully differ between the children of prenatally non-depressed and depressed mothers, regardless of intervention arm.

Discussion

Our study showed that a peer-delivered intervention beginning in pregnancy with booster sessions through 36-months postnatal did not measurably affect a range of maternal depression symptom and child developmental outcomes. Though women in the treatment arm did show greater convergence in depression symptoms with the prenatally non-depressed women at 36 months, relative to women in the control arm, evidence of a meaningful intervention effect is lacking. We also find only weak evidence that the prenatal depression episode was itself associated with child socioemotional outcomes and no evidence of associations with other developmental outcomes; for the most part, children of prenatally depressed and prenatally non-depressed mothers had similar outcomes at 36-months of age.

The overall small effect sizes and lack of statistical significance on maternal outcomes might be attributable to several factors. First, the intervention was a non-specialist, lay peer delivered psychosocial intervention. The lay peers were housewives from rural villages, without prior training or work experience. They were trained and supervised by non-specialists using a cascaded model (with no direct specialist contact). 26 Second, this lay peer delivered approach was used to inform scaling-up of maternal mental health services through existing health systems and community resources. It is possible that this non-specialist, low-intensity design, coupled with longer-duration implementation, led to what Chambers and colleagues refer to as ‘voltage drop’ (the intervention loses some degree of its potency (or fidelity) when moving from efficacy to effectiveness in the real world) and ‘program drift’ (the intervention deviates from its manualized or implementation protocols).41 We saw a substantial drop in women attending the maintenance group sessions delivered every two months beyond the 6th month postnatal period. This implementation challenge of attendance is reported in other community based interventions targeting maternal outcomes.42 Women reported that the women lost interest in attending these group sessions or found it demanding on their time. This challenge of poor attendance and how to best address it came up regularly in peer supervision meetings. In addition to attempts to add more interesting content to the sessions, we made sure that community health workers reminded women about the sessions and followed up with those who missed a session. Addressing sustaining participant interest and limited time is seminal in community-based program success and has been highlighted as an important challenge in other low resource settings.43 Finally, it is possible that, since the booster group sessions did not focus on specific strategies to address depression as mentioned earlier, the intervention arm was not so different from the EUC arm. There were no detectable treatment effect at the 6 month postnatal wave.16The boosters introduced after the 6 months mark did not change this- we continue to see no intervention effect at 36 months.

Maintaining the competence levels and motivation of the peers over the multi-year long implementation period was challenging. Perhaps the cascaded model of supervision via non-specialists led to dropped potency (or fidelity) of sessions. We explored the perceptions of the peers about this intervention in a nested qualitative study at six months postnatal.26 We did not find any negative perceptions towards the intervention which might have led to change in motivation or competence levels.. The reduced frequency of supervision sessions of the peers from every month to every two months seems to have contributed to the drop in competence levels. This drop in supervisory intensity has been shown to reduce effectiveness of known approaches.44,45 Another contributing factor to the drop in competence levels was the addition of new content, beyond the 6th month postnatal period: both the high and low scoring peers experienced a drop in competence levels when more content was added. Finding the right balance of content vs capacity of peers, and maintaining fidelity, is an implementation challenge reported in other programs.46,47

Finally, we saw a substantial improvement in the control arm (lowered rates and higher recovery from depression). The control arm recovery rates were higher compared to our previous studies from 2008 and 2020.8,48 This could be attributable to “regression to the mean” or to spillover of the intervention through the LHWs who regularly interact with LHWs responsible for women residing in control arm sites. The active control arm received enhanced usual care and some evidence suggests that informing people about their illness status improves outcomes,49 which raises important methodological (study design) issues for trials that are embedded within community settings. Perhaps future trials, using similar active control arms ought to consider equivalence or non-inferiority trial designs to avoid a nonsignificant superiority trial being wrongly interpreted, as proof of no difference between the two active comparisons.50

We found no clear indications of sub-group differences. This points to the challenge of intervention targeting especially given that approximately one-fifth of women did not respond to this treatment, indicating a need for different interventions. A collaborative care model where non-responders can be detected earlier and connected to more specialized may be needed.

The findings suggesting an association (albeit weak) between prenatal depression and child socioemotional outcomes at age 3, which is not mitigated by the intervention, mirrors results from our previous trial with a different sample, designed to examine a similar intervention’s effect on children at age seven.4 Children’s socioemotional development may be less likely to ‘catch up’ during the resolution phase of depression within the postnatal period. If confirmed in other studies, differences in socioemotional, but not other developmental outcomes, may point to specific mechanisms in maternal-child intergenerational transmission of risk.11

While chronic depression likely has the greatest effect on child development,51 the majority of children in our study were exposed to varying maternal depression levels, including periods of low or no depression symptoms over the study period. An association between the prenatal episode and child socioemotional outcomes at 36 months would be consistent with ‘foetal programming,’52 and is supported by evidence of linking prenatal depression to a number of child outcomes regardless of postnatal depression.53 However, inconsistent with foetal programming, another study concluded that a reduction in maternal depression levels postnatally lead to ‘near normal levels’ of child behavioural problems.54

A possible explanation for the lack of intervention effects on child outcomes is that, unlike the trained specialist delivery in Stein et al’s study, this intervention was delivered by lay peers in a low-income country.54 As mentioned above, we experienced a ‘voltage drop’ over time in terms of reductions in both session frequency and attendance, posing significant challenges to sustained implementation.41 Another potential explanation of no group differences in socioemotional outcomes is that the variability maternal depression symptoms in the first 3 years could itself be a risk factor. Given that depression is a chronic, recurring disorder, mothers who were prenatally depressed likely recovered and had a recurrence. Variation in symptoms over time would be larger among women who entered the study depressed compared to those non-depressed. It is possible that these children were exposed to inconsistent or unpredictable parenting, which has been linked with negative behavioral and socioemotional indicators.55 This hypothesis is supported by results from prior work, showing a tendency toward worse child anxiety symptoms among children whose mothers relapsed when compared with those who had chronic depression.4

Our findings that receptive language, fine motor, and length- and weight-for-age Z scores were not a function of maternal prenatal depression status or whether she was treated with the intervention are consistent with our previous study and also with Tomlinson et al who did not observe intervention effects when looking at the continuous versions of the Bayley Scales and growth outcomes, although they did report a difference when outcomes were dichotomized.4,6 These results suggest that a different set of pathways operates for these outcomes relative to socioemotional development. It is possible that the child’s experience of maternal depression did not, on average, reach severe or chronic enough levels to affect language and fine motor development and growth. The possibility is consistent with prior literature that suggests that the most deleterious effects on child outcomes are from severe and persistent depression levels.51 A complementary possibility is that the effects of maternal depression on these child outcomes are a function of baseline levels of other risk factors, such as illness, low maternal literacy, intimate partner violence, and others. In samples such as ours where a large fraction of women carry these risk factors, the effects of depression per se on child development may be overshadowed.

The study has limitations. The indicators of child socioemotional outcomes, although measured with validated and extensively used instruments, were mother-reported and, as such, susceptible to bias. We addressed this by utilizing only validated instruments used extensively globally. Additionally, if depression symptoms biased reporting, we would expect this to affect the overall socioemotional domain. However, in exploratory analyses we found that only specific socioemotional domains were predicted by prenatal depression; we have no reason to believe that reports of hyperactivity or conduct problems would be more influenced by depression than reporting of peer or emotional problems.

Overall, our results on the lack of intervention effectiveness for maternal depression and child development at 36 months suggest three potential scenarios. First, specific to the socioemotional domains, the intervention may have been too “light touch” to reverse the effect of prenatal depression exposure. The peer delivered version of this psychosocial intervention had a weaker effect on maternal depression than found in a previous study where community health workers were used to deliver the intervention instead of peer volunteers.16,17 It is likely that women at risk of depression (and their children) need more than bimonthly group sessions delivered by peers for sustained changes to occur that will reduce depression’s effect on children. A different model of delivery such as collaborative, or stepped care, merit consideration, with a number of interventions simultaneously targeting specific population needs, e.g. domestic violence, poverty alleviation, social services, social health protection Second, single screening in pregnancy for elevated depression symptoms may not be sufficient to identify the highest risk women, those who will go on to have the most chronic depression trajectories, with the worst effects on their children. Targeting women with a history of depression in combination with other risk factors, such as poverty or IPV, and tailoring the intervention for them, may yield stronger results. Finally, the program was delivered in a high poverty context. It thus remains possible that if the entire socio-political environment were to prioritize women and children’s wellbeing and health, interventions such as ours would have more power to make a difference.

In sum, our findings suggest that prenatal depression may have persistent effects on the child’s socioemotional skills that are not easily reversed by a psychosocial intervention. Future preventive and early intervention efforts might benefit from being higher intensity and target the highest risk mothers. Importantly, interventions need to be attuned to the social context and ideally implemented as part of a suite of health promoting policies that address social determinants of maternal and child health.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study.

Recent systematic reviews of psychotherapy interventions for depression have highlighted the limited evidence on long-term effects of psychotherapy on either maternal mental health or child outcomes. We conducted a search to identify studies designed to evaluate interventions for perinatal depression, whose intervention either lasted beyond 12 months postnatal (e.g. booster sessions), or whose follow-up was more than 12 after the completion of the intervention, in years 2002-April 2020. We limited our search to randomized clinical trials or meta-analyses. We did not place restrictions on language or country. We used Pubmed and Web of Science, with the following search terms: ( (maternal depression) or (perinatal depression) or (postpartum depression) or (postpartum depression) ) AND ( (treatment) or (therapy) or (intervention) or (psychotherapy) or (cognitive behavioral therapy) ) AND ( (longer-term) or (longer) or (booster)). We identified six RCTs specific to perinatal depression with the longer follow-up period, ranging from 1.5 to 7 years. None utilized an extended duration design (booster sessions) that continued past 12 month postnatal; two studies included a non-depressed comparison group. Most common intervention models were Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Interpersonal Therapy (IPT). Evidence generally showed that interventions improved outcomes which then weakened over time so that, overall, there is limited evidence of intervention effects of perinatal depression interventions that persist beyond the perinatal period. Of the six studies, two reported some lasting impact. One study of 884 mother-child dyads assessed maternal and child outcomes 7 years after the end of a CBT intervention and found a 5 point percent lower rates of depression among mothers who received the intervention, but no significant effects on child outcomes. With this one exception, sample sizes were small, with studies having fewer than 60 participants per group available at follow-up.

Added value of this study.

Given the chronic and recurring nature of depression, longer lasting interventions may be necessary to effectively reduce disease burden and potentially reduce the intergenerational transmission of psychopathology. This study, in rural Pakistan, is the first large multi-year randomized controlled trial, focusing on both maternal and child outcomes, where individuals with depression received psychotherapy beginning prenatally. The extended duration psychosocial intervention evaluated in the current study did not show evidence of meaningfully reducing depression symptom levels, nor improving child outcomes, at the 3 years postnatal mark. These findings highlight the challenges of implementing a peer-delivered psychosocial intervention over a longer period in a low resource community setting.

Implications of all the available evidence.

These findings point to several implementation lessons for such task-shifted, low-intensity interventions when delivered at scale alongside existing health systems. These include importance of ensuring high levels of fidelity of the intervention, potentially through use of technology platforms. It is also important that any intervention be situated within a collaborative care model that can help detect and respond to women in need of other services to help social determinants like poverty and domestic violence or pharmacological interventions.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the NIH R01HD075875, NIMH U19MH95687, and NICHD T32HD007168.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

We declare we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gelaye B, Rondon MB, Araya R, Williams MA. Epidemiology of maternal depression, risk factors, and child outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet Psychiatry 2016; 3(10): 973–82. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30284-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D. Maternal Depression and Child Psychopathology: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2011; 14(1): 1–27. 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel V, Saxena S, Lund C, Thornicroft G, Baingana F, Bolton P, Chisholm D, Collins PY, Cooper JL, Eaton J, Herrman H, Herzallah MM, Huang Y, Jordans MJD, Kleinman A, Medina-Mora ME, Morgan E, Niaz U, Omigbodun O, Prince M, Rahman A, Saraceno B, Sarkar BK, De Silva M, Singh I, Stein DJ, Sunkel C, UnÜtzer J. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. The Lancet 2018; 392(10157): 1553–98. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maselko J, Sikander S, Bhalotra S, Bangash O, Ganga N, Mukherjee S, Egger H, Franz L, Bibi A, Liaqat R, Kanwal M, Abbasi T, Noor M, Ameen N, Rahman A. Effect of an early perinatal depression intervention on long-term child development outcomes: follow-up of the Thinking Healthy Programme randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2015; 2(7): 609–17. 10.1016/s2215-0366(15)00109-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahman A, Fisher J, Bower P, Luchters S, Tran T, Yasamy MT, Saxena S, Waheed W. Interventions for common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2013; 91(8): 593–601I. 10.2471/BLT.12.109819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomlinson M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Scheffler A, le Roux I. Antenatal depressed mood and child cognitive and physical growth at 18-months in South Africa: a cluster randomised controlled trial of home visiting by community health workers. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2018; 27(6): 601–10. 10.1017/s2045796017000257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman SH, Garber J. Evidence-Based Interventions for Depressed Mothers and Their Young Children. Child Dev 2017; 88(2): 368–77. 10.1111/cdev.12732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baranov V, Bhalotra S, Biroli P, Maselko J. Maternal Depression, Women’s Empowerment, and Parental Investment: Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial. American Economic Review 2020; 110(3): 824–59 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunlicks ML, Weissman MM. Change in child psychopathology with improvement in parental depression: A systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2008; 47(4): 379–89. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181640805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuijpers P, Weitz E, Karyotaki E, Garber J, Andersson G. The effects of psychological treatment of maternal depression on children and parental functioning: a meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psych 2015; 24(2): 237–45. 10.1007/s00787-014-0660-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman SH, Cullum KA, Dimidjian S, River LM, Kim CY. Opening windows of opportunities: Evidence for interventions to prevent or treat depression in pregnant women being associated with changes in offspring’s developmental trajectories of psychopathology risk. Development and Psychopathology 2018; 30(3): 1179–96. 10.1017/S0954579418000536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loechner J, Starman K, Galuschka K, Tamm J, Schulte-Körne G, Rubel J, Platt B. Preventing depression in the offspring of parents with depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Psychology Review 2018; 60: 1–14. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milgrom J, Holt CJ, Bleker LS, Holt C, Ross J, Ericksen J, Glover V, O’Donnell KJ, de Rooij SR, Gemmill AW. Maternal antenatal mood and child development: an exploratory study of treatment effects on child outcomes up to 5 years. J Dev Orig Health Dis 2019; 10(2): 221–31. 10.1017/s2040174418000739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kersten-Alvarez LE, Hosman CMH, Riksen-Walraven JM, van Doesum KTM, Hoefnagels C. Long-term effects of a home-visiting intervention for depressed mothers and their infants. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2010; 51(10): 1160–70. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02268.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Arfer KB, Christodoulou J, Comulada WS, Stewart J, Tubert JE, Tomlinson M. The association of maternal alcohol use and paraprofessional home visiting with children’s health: A randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2019; 87(6): 551–62. 10.1037/ccp0000408PMC6775769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sikander S, Ahmad I, Atif N, Zaidi A, Vanobberghen F, Weiss HA, Nisar A, Tabana H, Ain QU, Bibi A, Bilal S, Bibi T, Liaqat R, Sharif M, Zulfiqar S, Fuhr DC, Price LN, Patel V, Rahman A. Delivering the Thinking Healthy Programme for perinatal depression through volunteer peers: a cluster randomised controlled trial in Pakistan. Lancet Psychiatry 2019; 6(2): 128–39. 10.1016/s2215-0366(18)30467-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanobberghen F, Weiss HA, Fuhr DC, Sikander S, Afonso E, Ahmad I, Atif N, Bibi A, Bibi T, Bilal S, De Sa A, D’Souza E, Joshi A, Korgaonkar P, Krishna R, Lazarus A, Liaqat R, Sharif M, Weobong B, Zaidi A, Zuliqar S, Patel V, Rahman A. Effectiveness of the Thinking Healthy Programme for perinatal depression delivered through peers: Pooled analysis of two randomized controlled trials in India and Pakistan. J Affect Disord 2019. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuhr DC, Weobong B, Lazarus A, Vanobberghen F, Weiss HA, Singla DR, Tabana H, Afonso E, De Sa A, D’Souza E, Joshi A, Korgaonkar P, Krishna R, Price LN, Rahman A, Patel V. Delivering the Thinking Healthy Programme for perinatal depression through peers: an individually randomised controlled trial in India. Lancet Psychiatry 2019; 6(2): 115–27. 10.1016/s2215-0366(18)30466-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atif N, Bibi A, Nisar A, Zulfiqar S, Ahmed I, LeMasters K, Hagaman A, Sikander S, Maselko J, Rahman A. Delivering maternal mental health through peer volunteers: a 5-year report. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 2019; 13(1): 62. 10.1186/s13033-019-0318-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute of Population Studies - NIPS/Pakistan & ICF Intternational. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2012–2013. Islamabad: NIPS/Pakistan and ICF International, 2012–3. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institute of Population Studies Islamabad. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey. Islamabad, Pakistan: National Institute of Population Studies, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner EL, Sikander S, Bangash O, Zaidi A, Bates L, Gallis J, Ganga N, O’Donnell K, Rahman A, Maselko J. The effectiveness of the peer-delivered Thinking Healthy PLUS (THPP+) Program for maternal depression and child socioemotional development in Pakistan: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2016; 17(1): 442. 10.1186/s13063-016-1530-yPMC5017048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallis J, Maselko J, O’Donnell K, Song KE, Saqib K, Turner EL, Sikander S. Criterion-related validity and reliability of the Urdu version of the patient health questionnaire in community-based women in Pakistan. PeerJ 2018; 6(e5185). 10.7717/peerj.5185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sikander S, Ahmad I, Bates LM, Gallis J, Hagaman A, O’Donnell K, Turner EL, Zaidi A, Rahman A, Maselko J. Cohort Profile: Perinatal depression and child socioemotional development; the Bachpan cohort study from rural Pakistan. BMJ Open 2019; 9(5): e025644. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sikander S, Lazarus A, Bangash O, Fuhr DC, Weobong B, Krishna RN, Ahmad I, Weiss HA, Price L, Rahman A, Patel V. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the peer-delivered Thinking Healthy Programme for perinatal depression in Pakistan and India: the SHARE study protocol for randomised controlled trials. Trials 2015; 16: 14. 10.1186/s13063-015-1063-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atif N, Nisar A, Bibi A, Khan S, Zulfiqar S, Ahmad I, Sikander S, Rahman A. Scaling-up psychological interventions in resource-poor settings: training and supervising peer volunteers to deliver the ‘Thinking Healthy Programme’ for perinatal depression in rural Pakistan. Global mental health (Cambridge, England) 2019; 6: e4. 10.1017/gmh.2019.4PMC6521132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Organization. WH. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. mhGAP Intervention Guide for Mental, Neurological and Substance Use Disorders in Non-Specialized Health Settings: Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP): Version 20. Geneva: World Health Organization Copyright (c) World Health Organization 2016.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health O. WHO Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHO DAS II). http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/whodasii/en/index.html (accessed May 7, 2010.

- 29.Gorman LL, O’Hara MW, Figueiredo B, Hayes S, Jacquemain F, Kammerer MH, Klier CM, Rosi S, Seneviratne G, Sutter-Dallay AL. Adaptation of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV disorders for assessing depression in women during pregnancy and post-partum across countries and cultures. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2004; 46(23): s17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmad I, Suleman N, Waqas A, Atif N, Malik AA, Bibi A, Zulfiqar S, Nisar A, Javed H, Zaidi A, Khan ZS, Sikander S. Measuring the implementation strength of a perinatal mental health intervention delivered by peer volunteers in rural Pakistan. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2020: 103559. 10.1016/j.brat.2020.103559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodman R The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 1997; 38(5): 581–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samad L, Hollis C, Prince M, Goodman R. Child and adolescent psychopathology in a developing country: testing the validity of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Urdu version). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 2005; 14(3): 158–66. 10.1002/mpr.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayley N, Reuner G. Bayley scales of infant and toddler development: Bayley-III: Harcourt Assessment, Psych. Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Donnell K, Murphy R, Ostermann J, Masnick M, Whetten RA, Madden E, Thielman NM, Whetten K. A brief assessment of learning for orphaned and abandoned children in low and middle income countries. AIDS Behav 2012; 16(2): 480–90. 10.1007/s10461-011-9940-zPMC3817622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maselko J, Bates L, Bhalotra S, Gallis JA, O’Donnell K, Sikander S, Turner EL. Socioeconomic status indicators and common mental disorders: Evidence from a study of prenatal depression in Pakistan. SSM - Population Health 2018; 4: 1–9. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9 - Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2001; 16(9): 606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hedges LV. Effect Sizes in Cluster-Randomized Designs. JEBS 2007; 32(4): 341–70. 10.3102/1076998606298043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li P, Redden DT. Comparing denominator degrees of freedom approximations for the generalized linear mixed model in analyzing binary outcome in small sample cluster-randomized trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2015; 15(1): 38. 10.1186/s12874-015-0026-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gallis J, Turner EL. Relative measures of association for binary outcomes: Challenges and recommendations for the global health researchers. Ann Glob Health 2019; 85(1): 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gallis JA, Li F, Turner EL. xtgeebcv: A command for bias-corrected sandwich variance estimation for GEE analyses of cluster randomized trials. Stata Journal (in press): [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation science : IS 2013; 8: 117. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117PMC3852739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tandon SD, Ward EA, Hamil JL, Jimenez C, Carter M. Perinatal depression prevention through home visitation: a cluster randomized trial of mothers and babies 1-on-1. J Behav Med 2018; 41(5): 641–52. 10.1007/s10865-018-9934-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sondaal AEC, Tumbahangphe KM, Neupane R, Manandhar DS, Costello A, Morrison J. Sustainability of community-based women’s groups: reflections from a participatory intervention for newborn and maternal health in Nepal. Community development journal 2019; 54(4): 731–49. 10.1093/cdj/bsy017PMC6924535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baqui AH, El-Arifeen S, Darmstadt GL, Ahmed S, Williams EK, Seraji HR, Mannan I, Rahman SM, Shah R, Saha SK, Syed U, Winch PJ, Lefevre A, Santosham M, Black RE. Effect of community-based newborn-care intervention package implemented through two service-delivery strategies in Sylhet district, Bangladesh: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2008; 371(9628): 1936–44. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60835-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tripathy P, Nair N, Barnett S, Mahapatra R, Borghi J, Rath S, Rath S, Gope R, Mahto D, Sinha R, Lakshminarayana R, Patel V, Pagel C, Prost A, Costello A. Effect of a participatory intervention with women’s groups on birth outcomes and maternal depression in Jharkhand and Orissa, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2010; 375(9721): 1182–92. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62042-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yousafzai AK, Rasheed MA, Rizvi A, Armstrong R, Bhutta ZA. Parenting Skills and Emotional Availability: An RCT. Pediatrics 2015; 135(5): e1247–e57. 10.1542/peds.2014-2335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hafeez A, Mohamud B, Shiekh M, Shah I, Jooma R. Lady health workers programme in Pakistan: challenges, achievements and the way forward. JPMA 2011; 61(210): [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, Roberts C, Creed F. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008; 372(9642): 902–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paterick TE, Patel N, Tajik AJ, Chandrasekaran K. Improving health outcomes through patient education and partnerships with patients. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2017; 30(1): 112–3. 10.1080/08998280.2017.11929552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lesaffre E Superiority, equivalence, and non-inferiority trials. Bulletin of the NYU hospital for joint diseases 2008; 66(2): 150–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Netsi E, Pearson RM, Murray L, Cooper P, Craske MG, Stein A. Association of Persistent and Severe Postnatal Depression With Child OutcomesAssociation of Persistent and Severe Postnatal Depression With Child OutcomesAssociation of Persistent and Severe Postnatal Depression With Child Outcomes. JAMA psychiatry 2018; 75(3): 247–53. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robinson R, Lahti-Pulkkinen M, Heinonen K, Reynolds RM, Räikkönen K. Fetal programming of neuropsychiatric disorders by maternal pregnancy depression: a systematic mini review. Pediatric Research 2019; 85(2): 134–45. 10.1038/s41390-018-0173-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Donnell KJ, Glover V, Barker ED, O’Connor TG. The persisting effect of maternal mood in pregnancy on childhood psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology 2014; 26(2): 393–403. 10.1017/S0954579414000029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stein A, Netsi E, Lawrence PJ, Granger C, Kempton C, Craske MG, Nickless A, Mollison J, Stewart DA, Rapa E, West V, Scerif G, Cooper PJ, Murray L. Mitigating the effect of persistent postnatal depression on child outcomes through an intervention to treat depression and improve parenting: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2018; 5(2): 134–44. 10.1016/s2215-0366(18)30006-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frankenhuis WE, Del Giudice M. When Do Adaptive Developmental Mechanisms Yield Maladaptive Outcomes? Developmental Psychology 2012; 48(3): 628–42. 10.1037/a0025629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.