Abstract

Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) in the infant brain give rise to mature oligodendrocytes that myelinate CNS axons. OPCs are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress that occurs in many forms of brain injury. One common cause of infant brain injury is neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), which releases blood into the CSF and brain parenchyma of preterm infants. Although blood contains the powerful oxidant hemoglobin, the direct effects of hemoglobin on OPCs have not been studied.

We utilized a cell culture system to test if hemoglobin induced free radical production and mitochondrial dysfunction in OPCs. We also tested if phenelzine (PLZ), an FDA-approved antioxidant drug, could protect OPCs from hemoglobin-induced oxidative stress. OPCs were isolated from Sprague Dawley rat pups and exposed to hemoglobin with and without PLZ. Outcomes assessed included intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels using 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) fluorescent dye, oxygen consumption using the XFe96 Seahorse assay, and proliferation measured by BrdU incorporation assay. Hemoglobin induced oxidative stress and impaired mitochondrial function in OPCs. PLZ treatment reduced hemoglobin-induced oxidative stress and improved OPC mitochondrial bioenergetics. The effects of hemoglobin and PLZ on OPC proliferation were not statistically significant, but showed trends towards hemoglobin reducing OPC proliferation and PLZ increasing OPC proliferation (p=0.06 for both effects). Collectively, our results indicate that hemoglobin induces mitochondrial dysfunction in OPCs and that antioxidant therapy reduces these effects. Therefore, antioxidant therapy may hold promise for white matter diseases in which hemoglobin plays a role, such as neonatal IVH.

Background

Phenelzine (PLZ) exerts anti-oxidant effects and improves mitochondrial dysfunction in neurological diseases such as traumatic brain injury and ischemia. However, there are no studies investigating the effect of PLZ on white matter diseases mediated by hemoglobin-induced oxidative stress, such as intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) of prematurity. Here, we demonstrate that PLZ reduces hemoglobin-induced oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells.

Keywords: Intraventricular hemorrhage, seahorse, free radicals, white matter

INTRODUCTION

Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) of prematurity occurs in up to 30% of very low birthweight infants.1 IVH originates from the fragile blood vessels of the underdeveloped germinal matrix, a site of rapid cell division adjacent to the lateral ventricles of the brain. These vessels rupture due to physiologic events such as sudden blood pressure variations that are common in preterm infants. Intraventricular blood products such as hemoglobin and iron cause post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus (PHH) and white matter injury.2,3 The developing brain is rich in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs)4 that give rise to white matter and are highly vulnerable to oxidative stress.5,6 Although white matter injury is a hallmark of IVH7, the direct effects of the powerful oxidant hemoglobin on OPCs have not been studied.

Mitochondria direct cell survival and death by maintaining energy homeostasis and regulating redox-dependent signaling pathways.8 Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) that induce lipid, protein and DNA injury9 and mitochondria themselves can be vulnerable to oxidative injury.10 Since hemoglobin is a powerful oxidant, we hypothesized that it could disrupt mitochondrial dysfunction in OPCs.

One drug that has shown promise in reducing oxidative stress after neurological injury is phenelzine (PLZ). PLZ has antidepressant function due to its monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAO-I) activity but is also a free radial carbonyl scavenger capable of covalently binding carbonyls through a hydrazine functional group (-NH-NH2).11 PLZ scavenges free radical species, such as 4-hydroxynonenal, and reduces mitochondrial dysfunction and tissue loss in animal models of brain injury.12–15

In this study, we found that hemoglobin induces intracellular ROS generation and impairs mitochondrial function in OPCs. Treatment with PLZ reduced these effects. These data suggest that hemoglobin could directly impair white matter development in neonatal IVH and that antioxidant therapy may be a viable treatment strategy for neonatal IVH and other forms of injury to developing white matter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary cell culture.

All experiments were approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Timed pregnant Sprague Dawley rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). Primary OPCs were isolated as described previously16,17 with some modifications. Postnatal day 2 rat pups were euthanized by rapid decapitation and the cortices removed. Pooled cultures were prepared by placing tissues on ice in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing L-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, and 1g/L (corning#10–014-CM) glucose in all experiments, except for a preliminary experiment using 4.5g/L glucose (corning#10–013-CM). The tissue was minced in DMEM with a sterile scalpel blade and centrifuged at 4°C, 300 rcf for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was re-suspended in 10 ml dissociation media (DMEM with 0.280 μg/ml trypsin) and incubated on an orbital shaker at 200 rpm for 10 minutes at 37°C. Next, 10 ml of wash media (DMEM with 200U/ml DNase and 530 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor) was added and the mixture was briefly shaken and centrifuged at 690 rcf for 5 minutes. The pellet was then re-suspended in 3 ml of wash media and triturated to a single cell suspension. Next, 4 ml of enzymatic quench media (DMEM containing 1M MgCl2 and 1M CaCl2) was added and the mixture briefly shaken and centrifuged at 200 rcf for 5 minutes. The pellet was re-suspended in T-75 media (DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum) at a volume of approximately 10 ml per brain. The suspension was then plated into uncoated T-75 flasks at 10 ml per flask. Flasks were kept in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. Media was replaced after 24 hours and every 4–6 days thereafter.

Cells were allowed to proliferate until confluent, corresponding to day 9–13 post-dissection. Upon reaching confluency, microglia were detached and removed by vigorously tapping the flasks on the bench top and replacing the media.18 T-75 flasks, with OPCs remaining attached to an astrocyte monolayer, were then returned to the incubator for 2 hours. After equilibration, flasks were shaken again at 200 rpm overnight. OPCs, now in the supernatant, were re-suspended in 4 ml of serum free DMEM Sato with either 10 ng/ml platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) to maintain cells as OPCs or without PDGF and bFGF to allow for maturation in select experiments.19,20 In order to remove any remaining microglia, the cell suspension was incubated at 37°C for 45 minutes in a non-coated petri dish. The dish was then gently rinsed with culture media in order to release loosely attached OPCs, but leave more tightly adherent microglia behind. The supernatant was adjusted to a density of 15,000 cells per ml and transferred into poly-L-lysine-coated 4-well chamber slides, with 500 μl of cell suspension added per well (7,500 cells/well). These OPC cultures were >90% pure as verified by immunocytochemistry. Two different glucose concentrations were used, with a high glucose concentration (4.5g/L) used in initial experiments for ROS detection and Seahorse analysis (Figures 1 and 3); however, all subsequent experiments were performed using a lower (1g/L) glucose concentration.

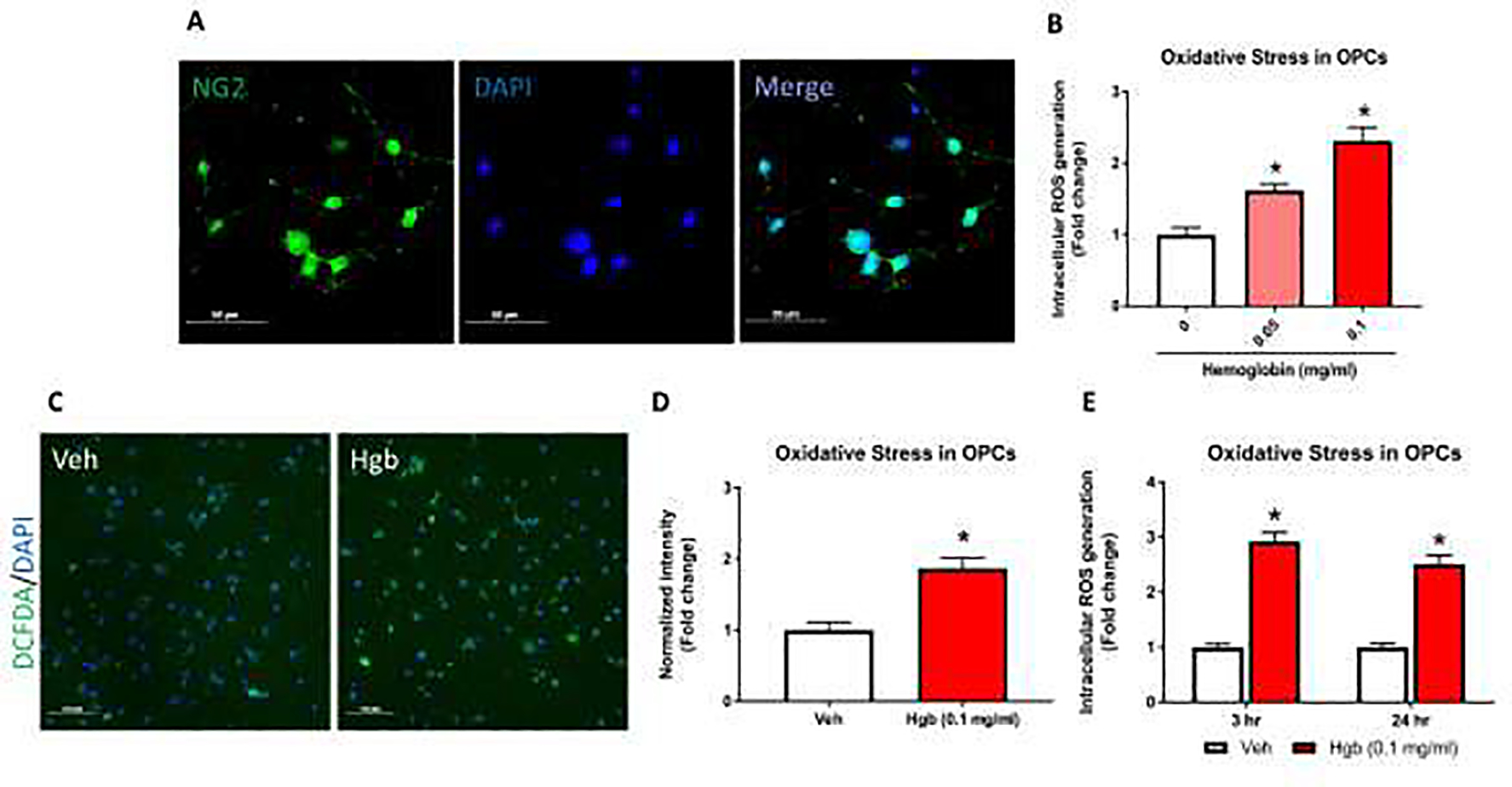

Fig 1. Hemoglobin-induced oxidative stress in primary OPCs.

Intracellular ROS measured by DCF-DA assay from isolated OPCs. (A) Immunofluorescence (IF) images show primary OPCs stained with NG2 (green) and the nuclear stain DAPI (blue). >90% of cells were NG2 positive. (B) OPCs were exposed to hemoglobin (0.05 and 0.1 mg/ml) for 24 hours and immediately assessed for intracellular ROS levels by DCF-DA via fluorescent microplate analysis. Both 0.05 and 0.1 mg/ml hemoglobin concentrations for 24 hours induced significant increase in ROS. (C) ROS production detected by DCF staining. Representative fluorescent images show that 24 hours of hemoglobin (Hgb) exposure increased ROS production in primary OPCs compared to vehicle (Veh). (D) Quantitative analyses show normalized DCF-DA fluorescent intensity. (E) Acute and chronic exposure of 0.1 mg/ml hemoglobin were tested for intracellular ROS generation. A significant increase oxidative stress was seen at 3 hours (2.92 fold) and 24 hours (2.51 fold) time point. Data are presented as mean ± SE; N = 3–8 for all groups. Each experiment was repeated two times and *=p < 0.05 was considered as significant vs vehicle.

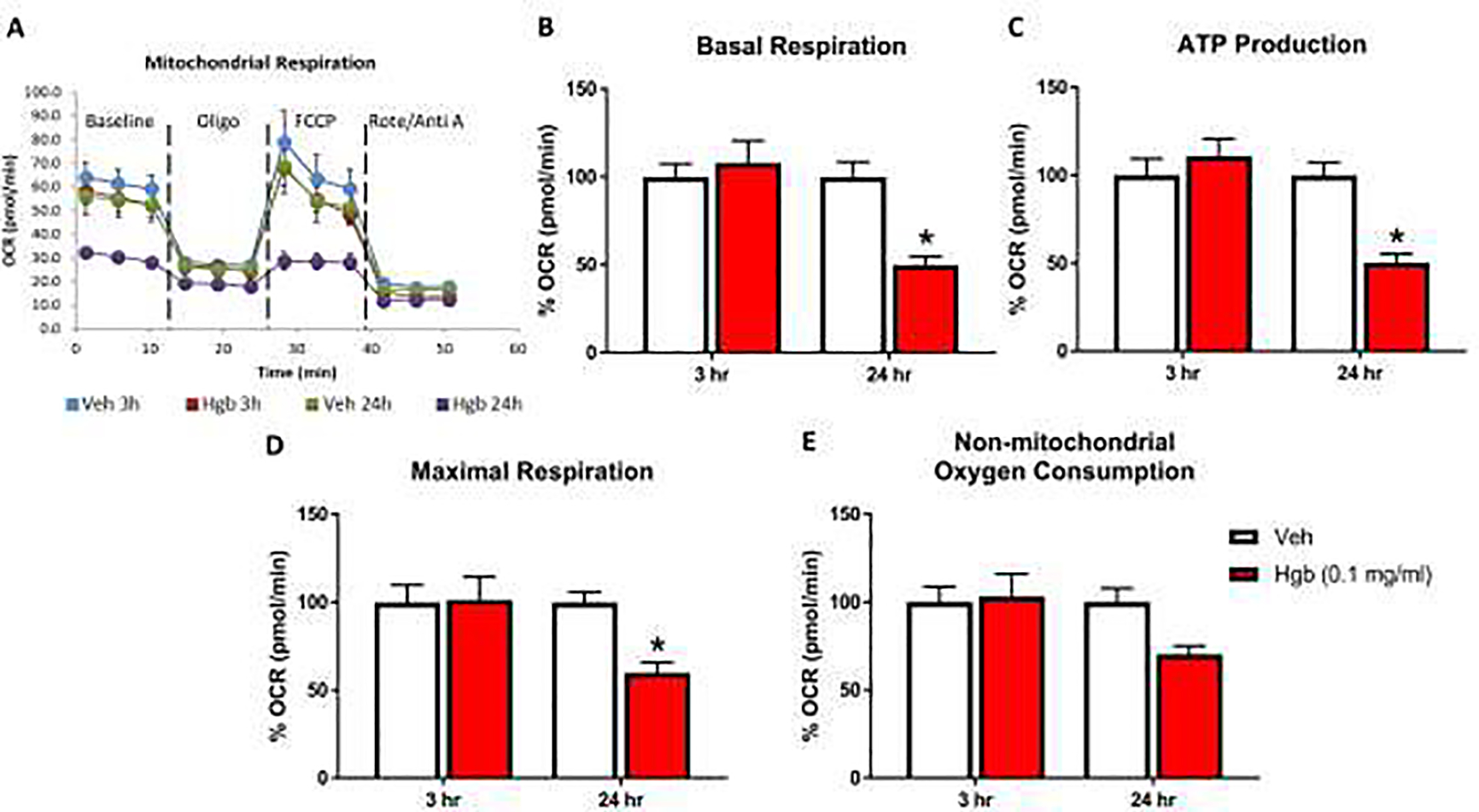

Fig 3. Hemoglobin decreases oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in OPCs.

Seahorse Cell Mito Stress Test was performed to measure OCR in acute (3 hours) and chronic (24 hours) incubation of vehicle and hemoglobin following a sequential addition of inhibitors of mitochondrial function such as oligomycin, carbonyl cyanide-ptrifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP), and a combination of rotenone and antimycin A; (A) OCR profile plot, (B) basal respiration, (C) ATP production, (D) maximal respiration and (E) non-mitochondrial consumption. Basal respiration was calculated after subtraction of non-mitochondrial respiration. ATP production or ATP-linked respiration were calculated following the addition of oligomycin. Maximal respiration was measured following the addition of FCCP. Data are presented as mean ± SE; N = 4 for all groups. Each experiment was repeated two times and *=p < 0.05 was considered as significant difference vs vehicle.

Intracellular ROS level.

A fluorometric microplate assay was used to measure intracellular ROS as described by others.21 Briefly, OPCs were plated at 20,000 cells/well in sterile 96-well opaque flat bottom microplates. At the designed time points, fresh media containing 10μM DCF-DA was added and the plates were incubated for 30 min at 37°C, 5% CO2. DCF-DA containing media was removed and cells were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Cells without DCF-DA dye (Invitrogen, D399) were used as blank. The oxidation of DCF-DA into highly fluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin (DCF) by intracellular ROS was measured at Ex/Em: 485/528 nm on a plate reader (BioTek, Synergy HTX).

LDH release assay.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release was used to detect cell death. The CyQUANT™ LDH Cytotoxicity Assay kit (Invitrogen, C20301) was utilized per the manufacturer’s protocol in OPCs grown in 96-well plates.

Mitochondrial bioenergetics assessment.

Mitochondrial function was determined as oxygen consumption rate (OCR) using a XFe96 Seahorse Bioscience Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Agilent Technologies) per manufacturer’s protocol. A standard XF cell Mito Stress Test (MST) protocol was performed to determine mitochondrial function.22 Briefly, OPCs were plated in 96-well plates at 20,000 cells/well density and treated the next day with either hemoglobin (0.1 mg/ml) PLZ (10, 30, and 100 μM) or vehicle in combinations for 3 hours and 24 hours. Prior to the assay, OPCs were washed and media replaced with pre-warmed XF assay medium supplemented with 1 mM Pyruvate, 2 mM Glutamine and 10 mM Glucose for 1 hour in a CO2-free incubator at 37°C. OCR measurements were carried out using XFe96 Seahorse analyzer at the beginning and after each sequential injection (to the final concentration) of oligomycin (4 μM), Carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP; 3 μM), and rotenone/antimycin A via sensor cartridge injection ports. The OCR was expressed as Basal, Maximal respiration, ATP (Adenosine triphosphate) production and non-mitochondrial respiration analyzed using a standard mitochondrial stress test report generator.23

Immunofluorescence staining.

For immunofluorescence (IF) staining of OPCs, cells were permeabilized with 0.2% triton-X100 for 5 min followed by blocking with 5% normal donkey serum for 1 hour at room temperature. Rabbit anti-neural/glial antigen 2 (NG2, 1:300, ab5320) and rat anti-Bromodeoxyuridine/5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU, 1:200, ab6326) monoclonal antibody staining was performed overnight at 4°C followed by rinsing with PBS and incubating with goat anti-rabbit (1:200, AF488, Invitrogen, A11008) and goat anti-rat (1:250, Cy3, Jackson Immunoresearch, 112–165-167) secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 hour. Slides were coverslipped using mounting media with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) counterstain (Vector Hardset Antifade Mounting Media), and stored at −20°C until imaging. Slides were scanned into digital files with a Zeiss Axio Scan.Z1 slide scanner at 20x magnification.

Cell Proliferation Assay.

Cell proliferation was quantified with a BrdU incorporation assay. OPCs were plated onto poly-L-lysine-coated 96-well plate at a density of 25×103 cells per well and were incubated without growth factors for 24 hours to allow for attachment. Cells were then treated with vehicle and hemoglobin in the presence and absence of PLZ for 48 hours. Cells were incubated with a single pulse of BrdU (10 mM) for 16 hours prior to the assay. Cells were washed, fixed and processed as described by others.19,24 Data were acquired using immunofluorescence staining. Data was expressed as mean +/− SEM.

Quantitative analysis of IF.

All slides were scanned with a Zeiss Axio Scan Z.1 digital slide scanner at 20x. Semi-automated, quantitative analysis was performed for scanned slides using HALO v2.2 software (Indica Labs). All analyses were performed by a technician blinded to experimental group. User-defined thresholds for positive staining were identical across all slides stained under the same conditions. The automated CytoNuclear FL v1 algorithm was used to identify and count positively stained cells. Positive cells were counted as number of cells displaying colocalization of BrdU and nuclear stain. Counted cells met user-set parameters including size limits and intensity thresholds that were applied uniformly across all experimental groups. The number of BrdU positive cells were calculated, and values were expressed as % proliferation (BrdU+DAPI+ cells).

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed by a statistician blinded to treatment group. The effect of hemoglobin on oxidative stress in OPCs was assessed with linear models adjusting for level of hemoglobin at 24 hours and a model adjusting for hours of exposure with hemoglobin at 0.1 mg/ml. All other analyses were stratified by 3 hour and 24 hour measurements. Generalized linear models were fit adjusting for dose and the interaction of hemoglobin and PLZ and experimental run. Since multiple comparisons were of interest, p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini and Hochberg method and p<0.05 was considered as significant.25 Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4. All experiments were performed in 2 separate replications and results pooled for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Hemoglobin increases intracellular ROS levels in primary OPCs.

Greater than 90% OPC purity was confirmed by immunofluorescence (IF) staining using NG226 (Fig 1A). All experiments in Figure 1 were performed in OPCs grown in media containing 4.5 g/L glucose starting from initial isolation as described above in materials and methods. Hemoglobin treatment for 24 hours increased ROS in a dose dependent manner as measured by quantitative florescence using DCF-DA analyzed by a plate reader system, where 0.05 mg/ml hemoglobin induced a 1.62-fold (p = 0.003) and 0.1 mg/ml hemoglobin induced a 2.32-fold (p < 0.0001) increase in oxidative stress compared to vehicle (Fig 1B). This effect was verified by intracellular DCF-DA fluorescence using microscopic image analysis (Fig 1C). Hemoglobin exposure for 24 hours significantly increased ROS generation as quantified by intracellular DCF-DA fluorescence using microscopic image analysis, where 0.1 mg/ml hemoglobin showed a 1.9-fold increase as compared to vehicle (p = 0.009; Fig 1D). Similarly, comparing different durations of hemoglobin exposure showed increased ROS levels after both 3 hours (2.92-fold; p < 0.0001) and 24 hours (2.51-fold; p <0.0001) of exposure to 0.1 mg/ml hemoglobin compared to vehicle (Fig 1E) via plate reader analysis. Exposure of OPCs to 0.1 mg/ml hemoglobin for both 3 and 24 hours did not demonstrate significant cytotoxicity as assessed by LDH assay (data not shown).

PLZ treatment suppresses hemoglobin-induced intracellular ROS in primary OPCs.

A range of PLZ doses were tested to reduce ROS generation in OPCs exposed to hemoglobin. PLZ doses of 10 μM, 30 μM and 100 μM were selected based on previously published work.12 All experiments in Figure 2 were performed in OPCs grown in media containing 1 g/L glucose starting from initial isolation as described above in materials and methods. OPCs were exposed to hemoglobin (0.1 mg/ml) for 3 hours and 24 hours, with and without simultaneous PLZ treatment. Hemoglobin exposure alone for 3 hours significantly increased ROS levels to 2.56-fold of control (p < 0.0001), and amongst different concentrations of PLZ tested, 10 μM treatment showed the strongest trend (p = 0.053) toward reducing the effects of hemoglobin (Fig 2A). Similarly, hemoglobin treatment for 24 hours significantly increased intracellular ROS levels 2.18-fold (p = 0.0003) compared to vehicle treatment (Fig 2B).

Fig 2. PLZ protects the hemoglobin-induced changes in oxidative stress in OPCs.

Isolated OPCs were treated with Hgb for 3 hours and 24 hours with or without simultaneous PLZ treatment. ROS production were immediately determined by DCF-DA assay. PLZ treatment was able to protect OPCs ROS production in a time-dependent manner. (A) Different dose (10μM, 30 μM and 100 μM) of PLZ treatment at 10 μM for 3 hours found to be protective against hemoglobin exposed increased ROS levels. (B) PLZ treatment for 24 hours, at 10 μM shows protective trends against hemoglobin-induced ROS levels in OPCs. Data are presented as mean ± SE; N = 3 for all groups. Each experiment was repeated two times and *=p < 0.05 was considered as significant difference vs vehicle exposed group.

Hemoglobin administration impairs mitochondrial respiration in OPCs.

To further assess mitochondrial function, we measured oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in live OPCs using the Seahorse XFe96 analyzer system.22,27 All experiments in Figure 3 were performed in OPCs grown in media containing 4.5g /L glucose starting from initial isolation as described above in materials and methods. Fig 3A shows a representative overview of vehicle and hemoglobin exposure for 3 hours and 24 hours. The results indicate that cell respiration analyses were functioning properly to treatments of oligomycin, FCCP, rotenone and antimycin A. Hemoglobin treatment (0.1 mg/ml) for 24 hours significantly reduced basal respiration to 49.95% of vehicle control (p < 0.0004; Fig 3B) and ATP production to 50.29% of vehicle control (p < 0.0002; Fig 3C), indicating mitochondrial functional impairment. Similarly, maximal respiration (Fig 3D), following the addition of FCCP showed a significant decline (59.96% of control; p < 0.0047), while non-mitochondrial OCR (Fig 3E) was not altered by 24 hours of hemoglobin exposure compared to vehicle treatment. Hemoglobin exposure for 3 hours did not show any significant effects on mitochondrial respiration (Fig 3B – E).

PLZ protects against hemoglobin-induced mitochondrial respiratory dysfunction in OPCs.

We then tested the ability of PLZ to reduce hemoglobin-induced OPC mitochondrial dysfunction. OPCs exposed to hemoglobin alone and in combination with various doses of PLZ underwent OCR measurement for 24 hours. PLZ and hemoglobin doses were chosen based on preliminary experiments of hemoglobin-induced toxicity and protective effects of PLZ. All experiments in Figure 4 were performed in OPCs grown in media containing 1 g/L glucose starting from initial isolation as described above in materials and methods. Hemoglobin treatment significantly reduced basal respiration to 46.70% of control (p < 0.0001; Fig 4A) and ATP production to 41.61% of control (p = 0.0001; Fig 4B). 10 μM PLZ treatment for 24 hours showed a protective trend against impairment of basal respiration by hemoglobin (p = 0.07), restoring it to 63.06% of control (Fig 4A). Similarly, maximal respiration was significantly decreased to 46.51% of control (p < 0.0007; Fig 4C) by hemoglobin, and 10 μM PLZ showed significant protection against this effect (p = 0.03). In this experiment, hemoglobin significantly reduced non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption to 75.89% of control (p = 0.04; Fig 4D) at 24 hours. In a separate experiment, the effects of hemoglobin and PLZ on OPC mitochondrial bioenergetics were tested at 3 hours. At the 3-hour time point, there were no changes in basal respiration (Fig S1A), ATP production (Fig S1B), maximal respiration (Fig S1C) and non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption (Fig S1D).

Fig 4. PLZ treatment enhance mitochondrial bioenergetics in hemoglobin exposed OPCs.

Oxygen consumption rate by seahorse were determined in primary OPCs after 24 hours of hemoglobin exposure in presence and absence of different concentration of PLZ; (A) OCR profile plot, (B) basal respiration, (C) ATP production, (D) maximal respiration and (E) non-mitochondrial consumption. PLZ at 10 μM concentration ameliorated the hemoglobin-induced decrease in basal and maximal respiration; however, ATP production shows increased trend. Non-mitochondrial respiration decreased with hemoglobin exposure, but did not changed with PLZ treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SE; N = 4–6 for all groups. Each experiment was repeated two times and *=p < 0.05 was considered significant vs vehicle.

OPC proliferation after hemoglobin and PLZ treatment.

OPC proliferation was quantified using a BrdU incorporation assay. Primary OPCs were treated with hemoglobin (0.1 mg/ml) with and without PLZ (10 μM) and cell proliferation was measured 48 hours later (Fig 5). The percentage of BrdU+ cells (Fig 5A–D) was lower in cells exposed to hemoglobin, but did not reach statistical significance (27.5% proliferating cells in hemoglobin group versus 37.5% proliferating cells in vehicle group; p = 0.06, Fig 5E). Similarly, when compared to the vehicle group, there was no statistically significant effect of PLZ on OPC proliferation (p = 0.06; Fig 5E).

Fig 5. PLZ enhances OPC proliferation.

Effects of hemoglobin (0.1 mg/ml) in presence and absence of PLZ (10 μM) treatment on OPC proliferation were measured by the BrdU incorporation assay. (A) Representative confocal images show that OPCs were stained with BrdU (red) and DAPI (blue) after 48 hours of PLZ and hemoglobin treatment. BrdU was added for the last 16 hours before fixing the cells. The images were acquired at 20X and scale bar is 100 μm. The pink spots represent the proliferative OPCs. (B) Quantitative analyses shows % proliferation, as calculated by BrdU+DAPI+ cells using HALO software. Data represents mean % proliferation ± SE (N = 3) and *P < 0.05 vs vehicle.

DISCUSSION

IVH releases hemoglobin into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)28 and brain parenchyma29 where it can react with developing white matter. Extracellular hemoglobin is a powerful oxidant30 and extracellular iron released from hemoglobin can generate free radicals via the Fenton reaction31. Although developing white matter is comprised primarily of OPCs, which have low levels of antioxidants32–34, the direct effects of hemoglobin on OPCs have not been previously studied.

We observed that hemoglobin significantly increased intracellular oxidative stress in OPCs and that PLZ, an FDA approved antioxidant drug, reduced this effect. Examining this effect at the level of the mitochondria, using the Seahorse system, revealed that hemoglobin directly reduced mitochondrial respiration and ATP production. Diminished ATP levels, excessive free radical production, and dysregulated cellular homeostasis contribute to many neurodegenerative diseases.35,36 Though our study is the first to show hemoglobin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in CNS cells, hemoglobin-induced dysregulation of mitochondrial function has been shown outside the CNS.37–39 Therefore, IVH may share common characteristics with other conditions such as sickle cell disease and thalassemia where hemoglobin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction is a key pathological event.

Notably, the effects of hemoglobin on mitochondrial function were significant only after 24 hours of hemoglobin exposure, and not at 3 hours. This time-dependent effect of hemoglobin on OPC function may have implications for IVH, as blood products released into the CSF and brain parenchyma persist for days or even weeks after IVH.40 This implies that antioxidant therapy for IVH could be applied in a delayed fashion and still be effective at improving OPC bioenergetics. Our in vivo work in an animal model of IVH is consistent with the in vitro data presented here, as we observed a peak in oxidative stress 24 hours after hemoglobin injection into the lateral ventricles of neonatal mice, without a significant effect at 3 hours.14,41,42

Without sufficient ATP production, cells are unable to proliferate.43 OPCs are the most mitotic cell population in the CNS, and infancy is a time of rapid brain growth and white matter development.44 We hypothesized that OPC proliferation would decrease as ATP production was hampered by hemoglobin, and recover with PLZ treatment in the same manner as oxidative stress and basal and maximal respiration. Contrary to our hypothesis, there were no statistically significant effects of hemoglobin and PLZ on OPC proliferation or cell death at the timepoints tested.

In conclusion, we present in vitro evidence that extracellular hemoglobin contributes to oxidative stress and that mitochondrial dysfunction could contribute to the pathophysiology of IVH or other diseases in which blood is released into the CNS, such as hemorrhagic stroke. This is consistent with our observation of white matter oxidative stress in an in vivo model of IVH.42 The improvement of hemoglobin-induced oxidative stress and altered mitochondrial bioenergetics by PLZ suggests that PLZ or other anti-oxidant therapies could reduce white matter injury that occurs in response to hemoglobin-induced injury.

Supplementary Material

Fig 6.

Schematic model of protective role of PLZ in hemoglobin-mediated ROS generation and altered mitochondrial bioenergetics in OPCs.

Translational Significance.

This study provides evidences that PLZ reduces oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in OPCs. This finding has translational significance, as it may serve as a foundation for developing therapeutics to preserve white matter after IVH.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This publication is based upon work supported in part by a Hydrocephalus Association Innovator Award to BAM, NIH/NINDS K08 NS112580 to BAM, University of Kentucky CCTS KL2 Fellowship to BAM, University of Kentucky CCTS Pilot Award to BAM and JCG UL1TR001998 and a University of Kentucky Research Alliance Award to BAM. We are thankful to Thomas Dolan and Matthew Hazzard, medical illustrators at University of Kentucky, for preparing schematic diagram. All authors have read the journal’s policy on conflicts of interest. Also, all authors have read the journal’s authorship agreement.

Abbreviations:

- OPC

oligodendrocyte progenitor cell

- IVH

intraventricular hemorrhage

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- PLZ

phenelzine

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- DCF-DA

2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- BrdU

Bromodeoxyuridine/5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine

- CNS

central nervous system

- PHH

post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus

- MAO-I

monoamine oxidase inhibitor

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- bFGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- OCR

oxygen consumption rate

- MST

mito stress test

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- IF

immunofluorescence

- NG2

neural/glial antigen 2

- FCCP

carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone

- Veh

vehicle

- Hgb

hemoglobin

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hart AR, Whitby EW, Griffiths PD, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and developmental outcome following preterm birth: review of current evidence. Dev Med Child Neurol 2008;50:655–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Z, Gao C, Hua Y, et al. Role of iron in brain injury after intraventricular hemorrhage. Stroke 2011;42:465–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JY, Keep RF, He Y, et al. Hemoglobin and iron handling in brain after subarachnoid hemorrhage and the effect of deferoxamine on early brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010;30:1793–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goulding DS, Vogel RC, Pandya CD, et al. Neonatal hydrocephalus leads to white matter neuroinflammation and injury in the corpus callosum of Ccdc39 hydrocephalic mice. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2020:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Back SA. Perinatal white matter injury: the changing spectrum of pathology and emerging insights into pathogenetic mechanisms. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 2006;12:129–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giacci M, Fitzgerald M. Oligodendroglia Are Particularly Vulnerable to Oxidative Damage After Neurotrauma In Vivo. J Exp Neurosci 2018;12:1179069518810004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adler I, Batton D, Betz B, et al. Mechanisms of injury to white matter adjacent to a large intraventricular hemorrhage in the preterm brain. J Clin Ultrasound 2010;38:254–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Kroemer G. Mitochondria: master regulators of danger signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012;13:780–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adiele RC, Adiele CA. Metabolic defects in multiple sclerosis. Mitochondrion 2019;44:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 2006;443:787–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galvani S, Coatrieux C, Elbaz M, et al. Carbonyl scavenger and antiatherogenic effects of hydrazine derivatives. Free Radic Biol Med 2008;45:1457–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cebak JE, Singh IN, Hill RL, et al. Phenelzine Protects Brain Mitochondrial Function In Vitro and In Vivo following Traumatic Brain Injury by Scavenging the Reactive Carbonyls 4-Hydroxynonenal and Acrolein Leading to Cortical Histological Neuroprotection. J Neurotrauma 2017;34:1302–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh IN, Gilmer LK, Miller DM, et al. Phenelzine mitochondrial functional preservation and neuroprotection after traumatic brain injury related to scavenging of the lipid peroxidation-derived aldehyde 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013;33:593–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pandya CDG DS; Vogel RC, Silberstein A; Morganti JM; Miller BA Utilizing in vitro Models of Neonatal Intraventricular Hemorrhage to Screen Anti-inflammatory and White Matter-protective Compounds American Association of Neurological Surgeons and Congress of Neurological Surgeons Section on Pediatric Neurological Surgery Annual Meeting,. Scottsdale, AZ, USA2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood PL, Khan MA, Moskal JR, et al. Aldehyde load in ischemia-reperfusion brain injury: neuroprotection by neutralization of reactive aldehydes with phenelzine. Brain Res 2006;1122:184–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller BA, Crum JM, Tovar CA, et al. Developmental stage of oligodendrocytes determines their response to activated microglia in vitro. J Neuroinflammation 2007;4:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCarthy KD, de Vellis J. Preparation of separate astroglial and oligodendroglial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue. J Cell Biol 1980;85:890–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin L, Desai R, Wang X, et al. Characteristics of primary rat microglia isolated from mixed cultures using two different methods. J Neuroinflammation 2017;14:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pang Y, Fan LW, Tien LT, et al. Differential roles of astrocyte and microglia in supporting oligodendrocyte development and myelination in vitro. Brain Behav 2013;3:503–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller BA, Sun F, Christensen RN, et al. A sublethal dose of TNFalpha potentiates kainite-induced excitotoxicity in optic nerve oligodendrocytes. Neurochem Res 2005;30:867–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H, Joseph JA. Quantifying cellular oxidative stress by dichlorofluorescein assay using microplate reader. Free Radic Biol Med 1999;27:612–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akundi RS, Zhi L, Sullivan PG, et al. Shared and cell type-specific mitochondrial defects and metabolic adaptations in primary cells from PINK1-deficient mice. Neurodegener Dis 2013;12:136–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saxena S, Vekaria H, Sullivan PG, et al. Connective tissue fibroblasts from highly regenerative mammals are refractory to ROS-induced cellular senescence. Nat Commun 2019;10:4400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pang Y, Zheng B, Fan LW, et al. IGF-1 protects oligodendrocyte progenitors against TNFalpha-induced damage by activation of PI3K/Akt and interruption of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Glia 2007;55:1099–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishiyama A, Boshans L, Goncalves CM, et al. Lineage, fate, and fate potential of NG2-glia. Brain Res 2016;1638:116–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Logan S, Pharaoh GA, Marlin MC, et al. Insulin-like growth factor receptor signaling regulates working memory, mitochondrial metabolism, and amyloid-beta uptake in astrocytes. Mol Metab 2018;9:141–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savman K, Nilsson UA, Blennow M, et al. Non-protein-bound iron is elevated in cerebrospinal fluid from preterm infants with posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation. Pediatr Res 2001;49:208–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darrow VC, Alvord EC Jr., Mack LA, et al. Histologic evolution of the reactions to hemorrhage in the premature human infant’s brain. A combined ultrasound and autopsy study and a comparison with the reaction in adults. Am J Pathol 1988;130:44–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bamm VV, Lanthier DK, Stephenson EL, et al. In vitro study of the direct effect of extracellular hemoglobin on myelin components. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015;1852:92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panfoli I, Candiano G, Malova M, et al. Oxidative Stress as a Primary Risk Factor for Brain Damage in Preterm Newborns. Front Pediatr 2018;6:369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thorburne SK, Juurlink BH. Low glutathione and high iron govern the susceptibility of oligodendroglial precursors to oxidative stress. J Neurochem 1996;67:1014–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosko L, Smith VN, Yamazaki R, et al. Oligodendrocyte Bioenergetics in Health and Disease. Neuroscientist 2019;25:334–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pantoni L, Garcia JH, Gutierrez JA. Cerebral white matter is highly vulnerable to ischemia. Stroke 1996;27:1641–6; discussion 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo C, Sun L, Chen X, et al. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen Res 2013;8:2003–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parihar MS, Brewer GJ. Mitoenergetic failure in Alzheimer disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2007;292:C8–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cardenes N, Corey C, Geary L, et al. Platelet bioenergetic screen in sickle cell patients reveals mitochondrial complex V inhibition, which contributes to platelet activation. Blood 2014;123:2864–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higdon AN, Benavides GA, Chacko BK, et al. Hemin causes mitochondrial dysfunction in endothelial cells through promoting lipid peroxidation: the protective role of autophagy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2012;302:H1394–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chintagari NR, Jana S, Alayash AI. Oxidized Ferric and Ferryl Forms of Hemoglobin Trigger Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Injury in Alveolar Type I Cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2016;55:288–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strahle J, Garton HJ, Maher CO, et al. Mechanisms of hydrocephalus after neonatal and adult intraventricular hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res 2012;3:25–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goulding DG, Vogel RC, Pandya C, Miller BA Acute Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in a Rat Model of Neonatal Intraventricular Hemorrhage. American Association of Neurological Surgeons and Congress of Neurological Surgeons Section on Pediatric Neurological Surgery Annual Meeting,. Nashville, TN, USA2018. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goulding DS, Vogel RC, Gensel JC, et al. Acute brain inflammation, white matter oxidative stress, and myelin deficiency in a model of neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2020:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lunt SY, Vander Heiden MG. Aerobic glycolysis: meeting the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2011;27:441–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neumann B, Kazanis I. Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells: the ever mitotic cells of the CNS. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2016;8:29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.