Abstract

Prevention is better than cure. A milestone of the anthropocene is the emergence of a series of epidemics and pandemics often characterized by the transmission of a pathogen from animals to human in the past two decades. In particular, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has made a profound impact on emergency responding and policy-making in a public health crisis. Classical solutions for controlling the virus, such as travel restrictions, lockdowns, repurposed drugs and vaccines, are socially unpopular and medically limited by the fast mutation and adaptation of the virus. This is exacerbated by microbial resistance to therapeutic drugs and the slowness of vaccine development. In other words, microbial pathogens are somehow ‘smarter’ and faster than us, thus calling for more intelligent cures to combat future pandemics. Here, we compare therapeutics for COVID-19 such as synthetic drugs, vaccines, antibodies and phages. We present the strength and limitations of antibiotic and antiviral drugs, vaccines, and antibody-based therapeutics. We describe smarter, cheaper and preventive cures such as bacteriophages, food medicine using probiotics and prebiotics, sports, healthy diet, music, yoga, Tai Chi, dance, reading, knitting, cooking and outdoor activities. Some of these preventive cures have been intuitively developed since thousands of years ago, as illustrated by the fascinating similarity of the Chinese characters for ‘music’ and ‘herbal medicine.’

Keywords: Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, Microbial resistance, Immunotherapy, Probiotics, Immune system

Introduction

Microbes have lived and multiplied on earth for billions of years (Schopf et al. 2018). These tiny organisms are essential for maintaining mass and energy flows in both natural and engineered environments. For instance, soil bacteria allow natural decomposition of organic debris, carbon sequestration and remediation of polluted soils (Lichtfouse et al. 1995; Henner et al. 1997; Harvey et al. 2002). Inside the human body, decomposition is also performed, mostly by gut bacteria, which constitute an intrinsic part of the human metabolic system (Yatsunenko et al. 2012). The human body hosts a large number of bacteria, estimated at 3.8 × 1013, which is the same order as the total number of human cells (Sender et al. 2016). Most of these bacteria perform vital functions, including food digestion, without which humans would not survive. Intriguingly, microbial footprints are even present in human genes, with about 8% of the human genome containing retroviral gene fragments (Wildschutte et al. 2016). These ‘genetic fossils’ are relics of human ancestors who survived viruses and epidemics, and their presence in the human genome suggests that viral infection represents a natural process of human adaptation and evolution. Conversely, microbes have also been used to fight against human pathogens, saving countless lives and maintaining public health (Fig. 1, Newman and Cragg 2016). Beside synthetic drugs (FDA 2018), many bio-derived drugs and biologics are potent cures and consist an essential part of modern medicines for treating human infections. In essence, contrary to the common popular belief, microbes such as viruses and bacteria are not necessarily harmful, and some of them could be vital for the survival of life and ecosystems.

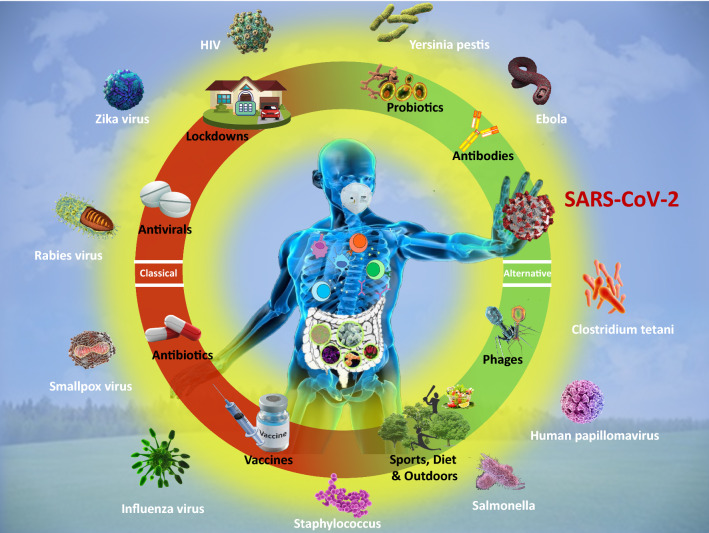

Fig. 1.

Classical and alternative medicines. Classical medicine treats patients with chemical drugs and vaccines after disease appearance; this approach is limited by pathogen mutation and adaptation to drugs, e.g., antibiotic resistance. Alternative medicine treats patients before disease appearance with living organisms, e.g., phages, probiotics or by applying practices that reinforce human immunity, e.g., sports, yoga, music, dance, healthy diet and outdoor activities

Some microbes are named pathogens because they are detrimental to human life and health. Indeed, millions of lives have been lost in epidemics caused by infections and pathogen spread in human history (Morens and Fauci 2020). More novel pathogens have infected humans following the aggravation of ecological balance disruption by expanding social and industrial activities (Cui et al. 2019). In particular, studies have shown links between infectious diseases and climate change, and have pointed out that emergent human diseases are often those where pathogens have spent a significant period of time outside the human host (Baylis 2017). For instance, in the past 20 years, humans have endured a series of epidemics and pandemics including the severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2002 (SARS), the 2009 swine flu (H1N1), the Middle East respiratory syndrome in 2012 (MERS), the US seasonal influenza in 2017–2018, the Western African Ebola virus in 2013–2016 and the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), most of which were caused by zoonotic pathogens (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_epidemics). At present, the global death toll of COVID-19 has reached three million, with more than 125 million people infected by the novel coronavirus (WHO 2021a). While microbes contribute to the evolution of living species on earth, the massive outbreaks of highly contagious and lethal pathogens may bring a devastating catastrophe to humans and some animals (Dyer 2020, O’Hanlon et al. 2018).

Indeed, in the twelfth month since the onset of the current pandemic, there is still no specific treatment available to the public for COVID-19. Although several vaccine manufacturers have declared their products to be generally effective (Moderna 2020; Pfizer 2020; Ramasamy et al. 2020), global vaccination is unlikely to happen anytime soon due to challenges in the allocation, storage and transport, and public acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines (Dai et al. 2020). Faced with this dilemma, many countries have imposed drastic travel restrictions and even lockdowns to slow the spread of the virus (Lau et al. 2020). While these policies have certainly been useful to some extent, they are causing serious secondary effects such as sharp economic losses and disruption of social, cultural and sport activities that are essential for maintaining the physical and mental health of humans. In the meantime, new challenges have continued to emerge even with these policies in place, such as re-emergent outbreaks (Han et al. 2020), novel viral strains (He et al. 2020) and reinfections due to the mutations of the novel coronavirus (To et al. 2020). Moreover, the inconsistent efficacy of many repurposed synthetic drugs (Pan et al. 2020) and possible growth of microbial resistance to these drugs are calling for an alternative path to prepare our communities for novel pathogens that are likely to emerge in the future. To this end, we must admit that current methods to combat pathogens are not fully efficient. Indeed, mainstream approaches such as finding a drug that kills the pathogen or creating a vaccine that improves human immunity are centuries old, e.g., early hints of inoculation for smallpox appeared in the tenth century and vaccination was first done by Edward Jenner in 1796 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vaccine). Here, we discuss the limits of antibiotics and antivirals, vaccines, antibodies, and we present promising alternatives such as phages, probiotics and improving the human immune system by diet, physical and outdoor activities. Advantages and limitations of classical and alternative cures are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Modes of action, advantages and limitations of classical and alternative cures for human infections caused by pathogens

| Type of cure | Modes of action (mechanism) | Advantages | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics |

Inhibit cell wall synthesis Enhance the permeability of bacterial cell membrane Interfere with protein synthesis Inhibit nucleic acid replication and transcription |

Wide applicability Safe Plentiful Cheap or affordable |

Promotes microbial resistance Gastrointestinal dysfunction Disruption of microbial community |

Brown and Wright (2016), Bud (2007), Finley et al. (2013), Ghooi and Thatte (1995) and Vaara (1992) |

| Antivirals |

Directly inhibit or kill viruses Interfere with virus attachment Prevent viruses from penetrating into cells Inhibit virus biosynthesis Inhibit virus release Enhance the antiviral ability of the host |

Wide applicability Plentiful Immunomodulation effects (interferons) Targeted therapy |

Promotes viral resistance Long treatment cycle Risk of rebound after withdrawal of medication Can be expensive |

Asselah et al. (2016), De Clercq (2004), De Clercq and Li (2016), Ison (2011) and Jefferson et al. (2006) |

| Vaccines | Induce immune response in human body to produce memory T cells and memory B cells, conferring specific immunity to humans |

High immune effect Long period of protection (for some pathogens) High specificity Multiple administration routes Cheap or affordable |

Long research & development cycle May fail or become less effective as pathogens evolve, requiring continuing vaccine development and vaccinations for protection Difficult to develop vaccines for fast-mutating species |

Hilleman (1998), Lachenbruch (1998), Ozawa et al. (2011), Pavlakis and Felber (2018) and Sutton and Boag (2019) |

| Antibodies |

Specific binding with antigens Based on the type of actions, they can be grouped into lectin, precipitin, antitoxin, lysin, opsonin, neutralizing antibody, complement fixation antibody, and others |

High specificity Low doses required |

Low yield Long preparation cycle Short-term prevention High costs |

Corti et al. (2016), Corti et al. (2011), Harrison (2020), Li et al. (2015) and Marovich et al. (2020) |

| Phages |

Adsorb: a phage adsorbs on the surface of a bacterium Invade: a phage enters the bacterium Replicate: a phage replicates itself in the bacterium Lyse: a phage breaks through the bacterium, the bacterium ruptures, and releases the replicating phage |

High specificity Short research & development cycle High yield Safe |

Not effective on viral pathogens without genome modification Unknown side effects |

Danis-Wlodarczyk et al. (2021), Krylov et al. (2019), Lammens et al. (2020), Sulakvelidze et al. (2001) and Wojewodzic (2020) |

| Probiotics |

Strengthen the gastrointestinal barrier by regulating tight junctions between intestinal epithelial cells Inhibit the invasion or overgrowth of pathogens Secreting bio-enzymes and bioactive peptides to promote the multiplication of immune cells and to participate in the repair of organs and tissues |

Immunomodulatory effects High yield Safe, mostly from food No additional costs Preventive effects |

Not an immediate cure A complex microbial community requiring further studies on their modes of action on invading pathogens and their long-term effects on human immune functions |

Antunes et al. (2020), Bidossi et al. (2018), Iordache et al. (2008), McFarland (2000), Sassone-Corsi and Raffatellu (2015), Vinderola et al. (2005) and Yan and Polk (2002) |

Synthetic drugs and microbial resistance

Since the nineteenth century, major advancements in chemistry, microbiology and genetics have paved the way for a ‘golden era’ of drugs, with successful developments of pioneering drugs such as the aspirin in 1897 (Berk et al. 2013), insulin in 1922 (Forsham 1982), penicillin in 1929 (Mehnaz 2013) and chemotherapeutic agents (Wang et al. 2017). While antibiotics and antivirals are highly effective in treating human infections, they are generally less effective in treating infections caused by novel pathogens (De Clercq and Li 2016). For instance, so far, none of the antiviral drugs can effectively fight against rabies, Ebola and emerging coronaviruses such as MERs-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Moreover, the abuse of antibiotics disrupts the balance between antibacterial drugs and bacterial resistance (Li et al. 2016). Indeed, through constant evolution and mutation, bacteria with single-drug resistance gradually evolve to multi-drug or even pan-drug resistant microbes, and eventually becoming ‘superbugs’ that are extremely difficult to treat with existing medicines (Rusu et al. 2015; Shin 2017). For instance, Staphylococcus aureus is a known drug-infective bacterium with high clinical importance, as it is almost resistant to all antibiotics (Antunes et al. 2020). Pseudomonas aeruginosa is also resistant to multiple antibiotics and consequently joined the ranks of superbugs due to its enormous capacity to engender resistance (Breidenstein et al. 2011).

The overuse and misuse of antibiotics and antivirals have been recognized as a major challenge in human health care (Feigman and Pires 2018). For example, 80% of outpatients with upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) are wrongly prescribed with antibiotics (Li et al. 2016), although etiological studies show that the main causes of these infections are viral pathogens, and only less than 10% of cases are caused by bacteria and thus require antibiotic treatment (Costelloe et al. 2010). In a recent report, the World Health Organization (WHO) highlighted a staggering surge of resistance to two key antiviral drugs, efavirenz and nevirapine, for treating human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (WHO 2019). The report further noted that combating antimicrobial resistance, including the emerging threat posed by drug-resistant HIV, is a major task of the research community. Further, excessive use of drugs can severely disrupt the microorganism communities in human bodies, causing massive elimination of beneficial microbes and aggressive selection of drug-resistant species (Croswell et al. 2009; Lawley et al. 2009; SanMiguel et al. 2017). Infections by drug-resistant pathogens lead to higher morbidity and mortality in patients, and impose additional burden and costs on our society (Wojewodzic 2020). In the United States alone, at least 2.8 million people are infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria each year, and more than 35,000 people eventually die from these infections (CDC 2019). According the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), antibiotic-resistant infections cost $20–$35 billion in direct healthcare costs annually in the United States (CDC 2014). Overall, antibiotics are generally not effective against viruses, and antibiotic overuse can rapidly induce the development of resistance by pathogenic bacteria. Vaccines thus appear to be a smarter approach, as discussed in the following section.

Vaccines, a smarter but outdated approach

The discovery of vaccines reminds us that our body’s immune system is an intelligent weapon against invading pathogens. As a preventive approach, the efficacy of vaccination has been proven on numerous human pathogens such as smallpox, rabies and tetanus (Ozawa et al. 2011). Millions of lives have been saved using subunit vaccines, non-replicating whole-virus or whole-bacteria vaccines, and attenuated live vaccines (Amanna and Slifka 2020; Yang et al. 2016). There are, however, inherent challenges and limitations on the development and use of vaccines (Dai et al. 2020). Generally, the development of any prospective vaccine requires stringent laboratory and clinical trials, a process that often takes years to complete to ensure its safety and efficacy (Wang et al. 2020a). Due to the long course of development and high specificity, vaccines are generally not considered first choices when responding to public health emergencies caused by novel pathogens (Lachenbruch 1998).

The inability to adapt to new variants of pathogens may also become the ‘Achilles’ heel’ of a vaccine. As of 23 March 2021, five SARS-CoV-2 variants, namely, the B.1.1.7 in the U.K., the B.1.351 in South Africa, the P.1 in Japan/Brazil, and the B.1.427 and the B.1.429 in California, United States, have been identified which are of most concerns because they spread more easily and are less susceptible to existing treatments (DeSimone 2021). Apart from these, the CDC is monitoring two emerging variants identified in New York, B.1.526 and B.1.525, and another variant identified in Brazil, P.2 (DeSimone 2021). Indeed, it is prohibitively difficult to develop effective vaccines against rapidly evolving and frequently mutating pathogens, such as the HIV and Helicobacter Pylori (Pavlakis and Felber 2018; Sutton and Boag 2019). For those which spread by selective routes, e.g., HIV, we could perhaps wait for the eventual success of vaccine development while in the meantime implementing effective measures to limit their spread in the population, e.g., by promoting public awareness. When dealing with a fast spreading and lethal novel pathogen, such as the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), we simply do not have enough time to cross one failure after another.

Whereas candidate vaccines have been successfully developed by Pfizer, Moderna and AstraZeneca as we write this article, detailed experimental data is unpublished. Particularly, how well these vaccines work in older people or those with underlying conditions, and their efficacy in preventing severe disease in COVID-19 patients are still unclear (Anonymous 2020). Whether the vaccines can effectively prevent the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 or mainly just protect people against illness is also largely unknown. Last, the willingness to take a COVID-19 vaccine is far from universal (Dai et al. 2020). Overall, the vaccine approach is somewhat smarter than chemical drug administration because vaccines aim at improving the immunity by ‘training human cells to combat a weakened enemy,’ yet virus mutation may outpace vaccine development by humans in a fast-spreading pandemic.

Promising antibodies

Since vaccination relies on creating specific antibodies, could we produce antibodies in other living organisms, then inject these antibodies into the human body? Here, the discovery of passive immunotherapy in the late nineteenth century paved the way for a new therapeutic treatment (Rosenberg and Terry 1977). Passive immunity refers to the transfer of active humoral immunity of ready-made antibodies to a different host. One example of natural passive immunity in human body is the transfer of maternal antibodies to the fetus through the placenta. Likewise, immunity can be artificially induced by transferring antibodies specific to a pathogen, which may be obtained from humans or animals, to non-immune persons, e.g., through immunization (CDC 2017). Passive immunization is used when there is a high risk of infection and insufficient time for the body to develop its own immune response to a novel pathogen, or to alleviate the symptoms of ongoing infections in patients (Savoy 2020). Since then, significant progress has been made in the field of immunotherapy, from murine monoclonal antibodies to the development of humanized antibodies (Manohar et al. 2015).

The application of genetic engineering brought new opportunities for the development of antibody drugs in recent years (Karagiannis et al. 2012). Antibody-based therapeutics have recently attracted wide attention (Shi et al. 2020), in which case the antibody was able to identify and bind to a particular protein on SARS-CoV-2, subsequently rendering the virus incapable of infecting human cells. This ‘neutralizing antibody’ is regarded as one of the most promising treatments for COVID-19.

Moreover, researchers have recently selected a monoclonal antibody from transgenic mice, then combined it with antibody-containing plasma of recovered patients, formulating a therapeutic cocktail for treating the novel coronavirus disease (Harrison 2020). This type of treatment, which received wide media coverage in the recent high-profile case of treating Donald J. Trump, the 45th President of the United States, can be highly effective and is well suited for treating individual patients. However, this treatment cannot be easily applied to a large population due to the inherently low yield and long preparation cycle of antibodies. Further, since neutralizing antibodies only provide short-term prevention, patients would need replenishing of antibodies every 1–2 months after receiving the initial treatment (Ferner and Aronson 2020; Harrison 2020). Overall, the antibody treatment appears efficient yet practically limited by its low yield and the need of frequent application.

Phages as predators for bacterial pathogens

Phagocyte is a type of cell in the human immune system that has the ability to ingest—and sometimes digest—foreign substances and pathogens. Phagocytes are one of the body’s natural defense mechanisms (Carlos and Harlan 1990). Interestingly, there are also viruses named ‘bacteriophages,’ which can ‘munch on’ bacteria. Bacteriophages have been used for treating people with bacterial infections in Russia and surrounding countries since the 1920s (Lammens et al. 2020), yet their application has later declined. In recent years, with the advent of antimicrobial resistance in bacterial pathogens, phage research has come back. For instance, in 2019 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first clinical trial of intravenously administered bacteriophage therapy (Voelker 2019). Systems biologist Marcin Wojewodzic recently commented that phages could be used to help COVID-19 patients by suppressing bacterial co-infections and producing antibodies (Wojewodzic 2020). Indeed, some phages are known to prey on bacterial pathogens that can cause human respiratory failure. By modifying their genomes, phages can be further used as mini production factories for making protective antibodies against viruses.

Compared with vaccines and antibodies, the development cycle for phage treatment is often shorter and the yield can be elevated (Lammens et al. 2020). Since phages are ‘picky predators’ that only act on specific types of bacteria (Sulakvelidze et al. 2001), the high specificity to target bacterium species gives the benefit of causing minimal damages to beneficial microbes in patient’s body (Wojewodzic 2020). Overall, phages can suppress bacterial co-infections and, through genome modification, produce antibodies to viral pathogens, thus representing a promising augmented therapy for COVID-19 patients.

Probiotics and prebiotics, the ‘food’ medicine

Probiotics are ‘live microorganisms that, when administrated, confer a health benefit to the host,’ according to the WHO and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (FAO/WHO 2020). Over the past two decades, there has been a surge in research on beneficial microbial communities with robust developments in the application of immunobiotics to combat human infections (Bhushan et al. 2019; Mandel et al. 2019). Probiotics are live bacteria, e.g., from food, that are ingested by humans. As major organisms in the human microbiome, probiotics play an indispensable role in the proper functioning of the human immune system. For instance, probiotics strengthen the gastrointestinal barrier by regulating tight junctions between intestinal epithelial cells (Zhang et al. 2018). Moreover, Bacillus subtilis strain 29784 enhanced the expression of tight junction proteins including zonula-1, occludin and claudin-1 to reinforce the intestinal barrier integrity (Rhayat et al. 2019). Some probiotics could even inhibit the invasion or overgrowth of pathogens (O’Callaghan and Corr 2019). Such effects have been demonstrated by the fact that intestinal microbiota can provide colonization resistance to infected Citrobacter rodentium (Lawley et al. 2009). Similarly, the cecal colonization of enterohemorrhagic E. coli, an enteric pathogen, could be reduced by commensal E. coli strains that compete for proline, a proteinogenic amino acid (Sassone-Corsi and Raffatellu 2015).

The inhibition effect of Lactobacillus strains has also been proven on several pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli and Enterobacter, where Lactobacillus strains produced bioactive soluble molecules to inhibit the growth of invading pathogens (Iordache et al. 2008). In a more recent study, probiotics Streptococcus salivarius 24SMB and Streptococcus oralis 89a inhibited the colonization of upper-airway pathogens, and reduced the inflammation on human respiratory mucosa by interfering with the biofilm formation of pathogens and by dispersing their pre-formed biofilms (Bidossi et al. 2018).

Probiotics can also boost human immune functions by secreting bio-enzymes and bioactive peptides to promote the multiplication of immune cells and to participate in the repair of organs and tissues (Kasahara et al. 2018; Lai et al. 2010; Mandel et al. 2019). Probiotics in HIV-infected patients exhibited therapeutic effects by restoring the functions of the epithelial barrier, facilitating the secretion of cluster differentiation (CD4)+ T cells and promoting immune activation (D’Angelo et al. 2017). Evidence also showed that various human skin resident microbes controlled the expression of antimicrobial peptides (Gallo and Hooper 2012) and augmented cutaneous IL-1 signaling to promote T cells effector functions (Naik et al. 2012). Meisel et al. (2018) further confirmed these findings at the transcriptome level, and revealed that skin microbiome mediated the immune response, epidermal development and differentiation through modulating gene expression.

Researchers have recently attempted to develop probiotic-based therapies for COVID-19 treatment. For instance, a recent investigation on changes in intestinal bacteria during COVID-19 patients’ hospitalization highlighted the concept that targeted modulation of gut microbiota may present a therapeutic avenue for COVID-19 and comorbidities (Zuo et al. 2020). An earlier study also demonstrated the principle of probiotic-based treatment as a means of targeted microbiome modulation where the needed probiotics were administrated to the patient as an intervention to change the gut microbiome toward a desired state (Schmidt et al. 2018). Furthermore, Antunes et al. (2020) presented evidence supporting the use of probiotics and prebiotics to promote gut and lung immunity, in a review on the use of beneficial microbes to protect the public in the ongoing pandemic.

If probiotics is a ‘food’ medicine for people, prebiotics is a special nutriment for probiotics. Prebiotics is defined as indigestible food ingredients that are not digested in the upper gastrointestinal tract and specifically fermented by the intestinal flora like bifidobacterial (Chen et al. 2016). Prebiotics can selectively stimulate the growth and activity of bacteria and the formation of bacterial flora in the colon (Kunz and Rudloff 1993; van den Heuvel et al. 1999). Prebiotics are important for the metabolism of lipid, protein and minerals, and are therefore more widely used in the food sector and some other fields (Gibson and Roberfroid 1995). Oligosaccharides including lactulose, fructooligosaccharides, isomaltooligosaccharides and galactooligosaccharides, inulin, and some microalgae, including spirulina and arthrospira, possess prebiotic properties (Sousa et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2016). Given that feeding our probiotics with proper feed, e.g. prebiotics such as dietary fibers, is as important to the immune health as taking probiotics, a healthy diet rich in prebiotics, e.g., fibers, fruits, vegetables and whole grains, is important for proper immune system functioning, in order to feed our probiotics properly. Overall, the discovery of new probiotics and prebiotics, and more importantly, further understanding of their mechanisms of actions could provide alternative therapeutics for human infections.

Sports, diet, music, yoga, Tai Chi, dance, reading, knitting, cooking and outdoor activities to improving our immune system

To combat future diseases, research should go beyond drugs, vaccines and other classical concepts. An obvious alternative is to reinforce the human immune system during infection and—most importantly—before infection. Many external factors are known to decrease the immunity: pollution, junk food, smoking, social stress, absence of physical activity, isolation from natural surroundings, excessive disinfection and sedentary lifestyles where people stay motionless behind computers or spending hours watching televisions or using smartphones. It would be worth to conceptually estimate the number of COVID-19 deaths than can be indirectly attributed to the decreased immunity of humans. While the COVID-19 pandemic has caused over two and a half million deaths, one should not ignore the fact that there has been many asymptomatic and self-recovering individuals without medical intervention (Oran and Topol 2020). Here, symptom aggravation not only depends on the viral load and strains from the initial transmission, but is closely related to the functioning of the individual’s immune system. If COVID-19 becomes an endemic like influenza and malaria (WHO 2020; WHO 2021b), then probably the best preventive strategy is to increase the immunity of the general population. A properly functioning immune system could be our most reliable and last line of defense for COVID-19 and its variants, and novel pathogens that will emerge in the future.

There are viable methods, many of which have been proven to increase the immunity of the human body, if practiced routinely (Lichtfouse 2020). To begin with, it has been long recognized that maintaining an adequate level of physical activities has profound effects on the functioning of the human immune system. Regular exercising improves immune regulation by affecting leucocytes, red blood cells and cytokines, while it also contributes to preventing infections and curing diseases (Wang et al. 2020b). Yoga, which originated from ancient India and is often recommended for people with depression or eating disorders, is an easy-to-practice exercise for promoting one’s physical and mental health (Greenlee et al. 2017). A recent study found that yoga practitioners overall enjoyed better health and had healthier lifestyles compared with the wider population (Cramer et al. 2019). Other alternative such as Tai Chi, a traditional internal Chinese martial art, improves the well-being of a person and helps prevent or alleviate chronic conditions (Guo et al. 2014).

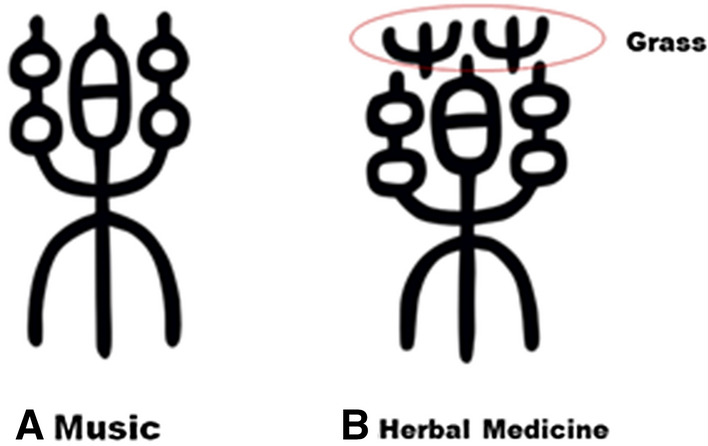

Maintaining a healthy diet is an essential step for maintaining the proper functioning of the intestinal immune system (Molendijk et al. 2019). A good, balanced diet rich in vitamins, probiotics and other nutrients preserves the balance of gut microbiota and the body’s metabolism (Schmidt et al. 2018, Shoaie et al. 2015). For some people, music therapy is also effective as an auxiliary means of alleviating stress and maintaining emotional wellness. In fact, it is regarded as an alternative medicine for mental health since ancient times. The fascinating similarity of the Chinese characters for ‘music’ and ‘medicine’ is a vivid expression of the ancient Chinese understanding of the relationship between music and medicine (Fig. 2). It was believed that music had the power to heal, enrich and harmonize as a therapeutic tool. Coincidently, there are also records of using music in healing in the Bible (Aluede and Ekewenu 2009). Some studies analyzed the relationship between the physics of sound and the psycho–neuro–immuno–endocrinologic system (Lippi et al. 2010, Diamond 2002). It has already been confirmed that music decreases anxiety, reduces psychological and physical symptoms, and helps increasing host immunity (Lippi et al. 2010).

Fig. 2.

Traditional Chinese characters of ‘music’ (a) and ‘herbal medicine’ (b). In ancient China, one of music’s earliest purposes was for healing. The two characters are similar on both strokes and pronunciations. Psychology and physiology are regarded as a unified whole in Chinese medicine, which means in the etiology, pathogenesis and treatment, changes in psychological and physiological interact together mostly (Karchmer 2013). Over 2000 years, music therapy is an important non-physiological approach for Chinese medicine in its therapeutic spectrum. Reprint from Zhang and Lai (2017)

Dancing, which combines light physical activities and music, has also been proved to promote community health and to treat cancer, diabetes and heart diseases with body movements, steps, expression and interaction (Ravelin et al. 2006; Iuliano et al. 2017). Reading, knitting and cooking are additional practices benefiting one’s mental health and social well-being. In the UK, the reading therapy has been recommended for treatment of mental disorder, from the early 1980s (Forrest 1998). Some researchers suggested that knitting in a group can promote relaxation, stress relief and creativity (Riley et al. 2013), while cooking activities have similar effects with additional benefits of enhancing one’s nutritional status, dietary variety, socialization and overall health (Goldschmidt and Song 2017).

Being close to nature by spending time in the natural outdoor environments can do wonders for one’s health. There is a lot of hidden knowledge in these ecological medicines and treatments. For instance, Swinburn et al. (1998) told many stories about the health benefits of spending time in nature. Seltenrich (2015) further suggested using parks to improve children’s health after reviewing ample documented evidence that children have much to gain from their activities in natural environments, which enhance their emotional well-being and amplify the benefits of physical exercise. Particularly, Kuo (2015) presented over twenty mechanisms of the nature-health connection in a review on how living and interacting with nature promotes human health. Kuo explained immunity improvement by three main factors: 1) active ingredients or environmental conditions including volatile organic chemicals emitted by plants, 2) sights and sounds of nature, and protection from air pollutants and heat. There is also emerging evidence that evergreen Mediterranean forests and shrubland plants may have alleviated the infections and symptom aggravation of COVID-19 in southern Italy (Roviello and Roviello 2020).

Ufnalska (2020a) pointed out the higher prevalence of suicides and disease transmission among family members during COVID-19 lockdowns. To alleviate this issue, she proposed a strategy by combining natural therapies and avoiding the ‘three Cs’: crowded places, closed-contact settings and confined places (Ufnalska 2020b). This strategy promotes a healthy lifestyle enriched in outdoor physical activities, e.g., strolls, gardening and birdwatching, and also forest education, music and art therapy to minimize the impact of mental stress and other problems resulting from the pandemic. Additionally, she stressed the need for proper indoor ventilation with fresh air as well as fighting addictions and fever phobia, which are known to lower our immunity. She also explained that breathing through the nose should decrease infection, as suggested by Nobel prize winner Prof. Louis Ignarro (2020). Indeed, our nasal cavities produce nitric oxide (NO), which intensifies blood flow through the lungs and elevates oxygen levels in the blood. As a consequence, inhaling air through the nose delivers NO directly into the lungs, which has proved to block the replication of SARS-CoV-1 (Åkerström et al. 2005).

More novel pathogens including zoonotic agents will emerge in the future as a consequence of the growing global population, urbanization and industrialization (Zhong et al. 2020). While modern medicine and treatments are still essential building blocks of public health systems, a smarter path could be pursued to provide long-term protection for people to live well in the future world. Studies on probiotics and the human immune system, maintaining a healthy lifestyle, and learning to live and evolve with microbial flora in nature may provide the answers for humans to adapt to the future uncertain world.

Conclusion

The increasing incidents of zoonotic pathogens spilling over to humans in the past few decades have caused catastrophic losses of human lives and abrupt disruptions to social and economic activities. Through the current pandemic, tremendous efforts have been made on conventional therapeutic treatments using repurposed drugs, vaccine developments, as well as various mandates refraining people from travels and social activities to reduce the virus spread and human infections. The efficacy and availability of these classical cures are reviewed in the current pandemic context, as well as their negative impact and inherent limitations. While these have served as the keystones on maintaining our public health system, their intrinsic shortcomings have been manifested by the current situation when humans are faced with a lethal, fast spreading and evolving novel pathogen. Consequently, we ought to reflect on whether current social restrictions and therapeutic venues are still competent in an era with exacerbated drug resistance and increasing emergence of novel pathogens. The challenges and dilemmas culminated in the current pandemic have set out a new imperative for scientists and public health authorities on seeking a smarter path to prepare our communities against novel pathogens beyond the current lockdowns, drugs and vaccines. In this domain, some creative research and comments in recent literature seem to offer valuable perspectives and strategies, such as neutralizing antibodies, phages, probiotics and methods to passively improve human immune functions to adapt to evolving microbes and novel pathogens.

With the ecological balances being constantly disrupted by anthropogenic activities, there is a need to provide long-term protection against novel pathogens that are inevitable to appear in the future. In this regard, a growing body of evidence suggests that probiotics, physical exercise, balanced diet and alternative therapies including being close to nature are potentially valuable in preventing infections and managing disease conditions, while improving the well-being and quality of life. We expect that these promising alternative cures and preventive strategies will make more important contribution in our fights with pathogens in the future uncertain world.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Young Talent Support Plan of Xi’an Jiaotong University and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.51888103). The authors wish to thank the anonymous reviewers for helping us improve the manuscript. We thank Sylwia B. Ufnalska for providing information on natural therapies.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in this work. In particular, we are not sponsored and most of our discussed cures are free and require no additional spending, only knowledge and education.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Åkerström S, Mousavi-Jazi M, Klingström J, Leijon M, Lundkvist Å, Mirazimi A. Nitric oxide inhibits the replication cycle of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2005;79:1966–1969. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1966-1969.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aluede CO, Ekewenu DB. Healing through music and dance in the Bible: its scope, competence and implications for the Nigerian music healers. Stud Ethno-Med. 2009;3(2):159–163. doi: 10.1080/09735070.2009.11886355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amanna IJ, Slifka MK. Successful vaccines. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2020;428:1–30. doi: 10.1007/82_2018_102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous (2020) COVID-19 vaccines: no time for complacency. Lancet 396(10263, 21–27):1607. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32472-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Antunes AEC, Vinderola G, Xavier-Santos D, Sivieri K. Potential contribution of beneficial microbes to face the COVID-19 pandemic. Food Res Int. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselah T, Boyer N, Saadoun D, Martinot-Peignoux M, Marcellin P. Direct-acting antivirals for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection: optimizing current IFN-free treatment and future perspectives. Liver Int. 2016;36:47–57. doi: 10.1111/liv.13027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylis M. Potential impact of climate change on emerging vector-borne and other infections in the UK. Environ Health. 2017;16:112. doi: 10.1186/s12940-017-0326-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Dean O, Drexhage H, McNeil JJ, Moylan S, O’Neil A, Davey CG, Sanna L, Maes M. Aspirin: a review of its neurobiological properties and therapeutic potential for mental illness. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):74. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan B, Singh BP, Saini K, Kumari M, Tomar SK, Mishra V. Role of microbes, metabolites and effector compounds in host-microbiota interaction: a pharmacological outlook. Environ Chem Lett. 2019;17(4):1801–1820. doi: 10.1007/s10311-019-00914-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bidossi A, De Grandi R, Toscano M, Bottagisio M, De Vecchi E, Gelardi M, Drago L. Probiotics Streptococcus salivarius 24SMB and Streptococcus oralis 89a interfere with biofilm formation of pathogens of the upper respiratory tract. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:11. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3576-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breidenstein EBM, de la Fuente-Nunez C, Hancock REW. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: all roads lead to resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19(8):419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ED, Wright GD. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature. 2016;529(7586):336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature17042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bud R. Antibiotics: the epitome of a wonder drug. BMJ (Clinical Res Ed) 2007;334(Suppl 1):s6–s6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39021.640255.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlos TM, Harlan JM. Membrane proteins involved in phagocyte adherence to endothelium. Immunol Rev. 1990;114:5–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1990.tb00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (2019) Center for disease control and prevention. More People in the United States Dying from Antibiotic-Resistant Infections than Previously Estimated. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p1113-antibiotic-resistant.html

- CDC (2017) Center for disease control and prevention. Vaccines: Vac-Gen/Immunity Types. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vac-gen/immunity-types.htm

- CDC (2014) Center for disease control and prevention. Executive Office of the President. President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. Report to the President on Combating Antibiotic Resistance. September 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/report-to-the-president-on-combating-antibiotic-resistance.pdf. Accessed 19 Oct 2014

- Chen Y-L, Liao F-H, Lin S-H, Chien Y-W. A prebiotic formula improves the gastrointestinal bacterial flora in toddlers. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:3504282. doi: 10.1155/2016/3504282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti D, Misasi J, Mulangu S, Stanley DA, Kanekiyo M, Wollen S, Ploquin A, Doria-Rose NA, Staupe RP, Bailey M, Shi W, Choe M, Marcus H, Thompson EA, Cagigi A, Silacci C, Fernandez-Rodriguez B, Perez L, Sallusto F, Vanzetta F, Agatic G, Cameroni E, Kisalu N, Gordon I, Ledgerwood JE, Mascola JR, Graham BS, Muyembe-Tamfun JJ, Trefry JC, Lanzavecchia A, Sullivan NJ. Protective monotherapy against lethal Ebola virus infection by a potently neutralizing antibody. Science. 2016;351(6279):1339–1342. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti D, Voss J, Gamblin SJ, Codoni G, Macagno A, Jarrossay D, Vachieri SG, Pinna D, Minola A, Vanzetta F, Silacci C, Fernandez-Rodriguez BM, Agatic G, Bianchi S, Giacchetto-Sasselli I, Calder L, Sallusto F, Collins P, Haire LF, Temperton N, Langedijk JPM, Skehel JJ, Lanzavecchia A. A neutralizing antibody selected from plasma cells that binds to group 1 and group 2 influenza A hemagglutinins. Science. 2011;333(6044):850. doi: 10.1126/science.1205669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, Mant D, Hay AD. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer H, Quinker D, Pilkington K, Mason H, Adams J, Dobos G. Associations of yoga practice, health status, and health behavior among yoga practitioners in Germany-Results of a national cross-sectional survey. Complement Ther Med. 2019;42:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croswell A, Amir E, Teggatz P, Barman M, Salzman NH. Prolonged impact of antibiotics on intestinal microbial ecology and susceptibility to enteric salmonella infection. Infect Immun. 2009;77(7):2741–2753. doi: 10.1128/iai.00006-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Li F, Shi ZL. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danis-Wlodarczyk K, Dabrowska K, Abedon ST. Phage therapy: the pharmacology of antibacterial viruses. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2021;40:81–163. doi: 10.21775/cimb.040.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo C, Reale M, Costantini E. Microbiota and probiotics in health and HIV infection. Nutrients. 2017 doi: 10.3390/nu9060615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, Han J, Lichtfouse E. Who is running faster, the virus or the vaccine? Environ Chem Lett. 2020;18(6):1761–1766. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01110-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E, Li G. Approved antiviral drugs over the past 50 years. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2016;29(3):695. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00102-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E. Antivirals and antiviral strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2(9):704–720. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSimone DC (2021) What’s the concern about the new COVID-19 variants? Are they more contagious? https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/expert-answers/covid-variant/faq-20505779

- Diamond J (2002) Chapter 24—The therapeutic power of music. In: Handbook of complementary and alternative therapies in mental health. pp 517–537. 10.1016/B978-012638281-5/50025-5

- Dyer O. Denmark to kill 17 million minks over mutation that could undermine vaccine effort. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 2020;371:4338. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO (2002) Guidelines for the evaluation or probiotics in food. In Proceedings of the Joint FAO/WHO Working Group Report on Drafting Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food, London, ON, Canada, 30 April–1 May 2002 https://www.who.int/foodsafety/fs_management/en/probiotic_guidelines.pdf

- FDA USFGA (2018) What are “biologics” questions and answers. Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/center-biologics-evaluation-and-research-cber/what-are-biologics-questions-and-answers.

- Feigman MJS, Pires MM. Synthetic immunobiotics: A future success story in small molecule-based immunotherapy? ACS Infect Dis. 2018;4(5):664–672. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferner RE and Aronson JK (2020) Monoclonal antibodies directed against SARS-CoV-2: synthetic neutralizing antibodies, the REGN-COV2 antibody cocktail. The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. October 7, 2020. https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/monoclonal-antibodies-directed-against-sars-cov-2-synthetic-neutralizing-antibodies-the-regn-cov2-antibody-cocktail/

- Finley RL, Collignon P, Larsson DGJ, McEwen SA, Li XZ, Gaze WH, Reid-Smith R, Timinouni M, Graham DW, Topp E. The Scourge of Antibiotic Resistance: The Important Role of the Environment. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(5):704–710. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsham PH. Milestones in the 60-year history of insulin (1922–1982) Diabetes Care. 1982;5:1–3. doi: 10.2337/diacare.5.2.S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest ME. Recent developments in reading therapy: a review of the literature. Health Info Libr J. 1998;15(3):157–164. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2532.1998.1530157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo RL, Hooper LV. Epithelial antimicrobial defence of the skin and intestine. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(7):503–516. doi: 10.1038/nri3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlee H, DuPont-Reyes MJ, Balneaves LG, Carlson LE, Cohen MR, Deng G, Johnson JA, Mumber M, Seely D, Zick SM, Boyce LM, Tripathy D. Clinical practice guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment. CA-Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(3):195–232. doi: 10.3322/caac.21397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt J, Song H-J. Development of cooking skills as nutrition intervention for adults with autism and other developmental disabilities. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(5):671–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.06.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghooi RB, Thatte SM. Inhibition of cell wall synthesis—Is this the mechanism of action of penicillins? Med Hypotheses. 1995;44(2):127–131. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(95)90085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson GR, Roberfroid MB. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota—introducing the concept of prebiotics. J Nutr. 1995;125:1401–1412. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.6.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Qiu P, Liu T. Tai Ji Quan: an overview of its history, health benefits, and cultural value. J Sport Health Sci. 2014;3(1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2013.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Zhang X, He S, Jia P. Can the coronavirus disease be transmitted from food? A review of evidence, risks, policies and knowledge gaps. Environ Chem Lett. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01101-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison C. Focus shifts to antibody cocktails for COVID-19 cytokine storm. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(8):905–908. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0634-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey P, Campanella B, Castro P, Harms H, Lichtfouse E, Schaeffner A, Smrcek S, Werck-Reichhart D. Phytoremediation of polyaromatic hydrocarbons, anilines and phenols. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2002;9:29–47. doi: 10.1007/BF02987315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Han J and Lichtfouse E (2020) Bidirectional human-animal transmission of COVID-19 may seed future reinfections and vaccine failure. Environ Chem Lett. 10.1007/s10311-020-01140-4

- Henner P, Schiavon M, Morel JL, Lichtfouse E (1997) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) occurrence and remediation methods. Analusis 25:M56–M59. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/file/index/docid/193277/filename/1997AnalusisPAHrevised.pdf

- Hilleman MR. Six decades of vaccine development - a personal history. Nat Med. 1998;4(5):507–514. doi: 10.1038/nm0598supp-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignarro LJ (2020) The right way to breathe during the coronavirus pandemic. Conversat. https://theconversation.com/the-right-way-to-breathe-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic-140695

- Iordache F, Iordache C, Chifiriuc MC, Bleotu C, Smarandache D, Sasarman E, Laza V, Bucu M, Dracea O, Larion C, Cota A, Lixandru M. Antimicrobial and immunomodulatory activity of some probiotic fractions with potential clinical application. Archiva Zootechnica. 2008;11(3):41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ison MG. Antivirals and resistance: influenza virus. Curr Opin Virol. 2011;1(6):563–573. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuliano JE, Lutrick K, Maez P, Nacim E, Reinschmidt K. Dance for your health: exploring social latin dancing for community health promotion. Am J Health Educ. 2017;48(3):142–145. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2017.1292875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson T, Demicheli V, Rivetti D, Jones M, Di Pietrantonj C, Rivetti A. Antivirals for influenza in healthy adults: systematic review. Lancet. 2006;367(9507):303–313. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(06)67970-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannis SN, Josephs DH, Karagiannis P, Gilbert AE, Saul L, Rudman SM, Dodev T, Koers A, Blower PJ, Corrigan C, Beavil AJ, Spicer JF, Nestle FO, Gould HJ. Recombinant IgE antibodies for passive immunotherapy of solid tumours: from concept towards clinical application. Cancer Immunol, Immun. 2012;61(9):1547–1564. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1162-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karchmer EI. The excitations and suppressions of the times: locating the emotions in the liver in modern Chinese medicine. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2013;37(1):8. doi: 10.1007/s11013-012-9289-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara K, Krautkramer KA, Org E, Romano KA, Kerby RL, Vivas EI, Mehrabian M, Denu JM, Backhed F, Lusis AJ, Rey FE. Interactions between Roseburia intestinalis and diet modulate atherogenesis in a murine model. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3(12):1461–1471. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0272-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krylov VN, Bourkaltseva MV, Pleteneva EA. Bacteriophage’s dualism in therapy. Trends Microbiol. 2019;27(7):566–567. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz C, Rudloff S. Biological functions of oligosaccharides in human milk. Acta Paediatr. 1993;82(12):903–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M. How might contact with nature promote human health? Promising mechanisms and a possible central pathway. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1093. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachenbruch PA. Sensitivity, specificity, and vaccine efficacy. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19(6):569–574. doi: 10.1016/S0197-2456(98)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y, Cogen AL, Radek KA, Park HJ, Macleod DT, Leichtle A, Ryan AF, Di Nardo A, Gallo RL. Activation of TLR2 by a small molecule produced by Staphylococcus epidermidis increases antimicrobial defense against bacterial skin infections. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(9):2211–2221. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammens E-M, Nikel PI, Lavigne R. Exploring the synthetic biology potential of bacteriophages for engineering non-model bacteria. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5294. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau H, Khosrawipour V, Kocbach P, Mikolajczyk A, Schubert J, Bania J, Khosrawipour T. The positive impact of lockdown in Wuhan on containing the COVID-19 outbreak in China. J Travel Med. 2020;27(3):7. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawley TD, Clare S, Walker AW, Goulding D, Stabler RA, Croucher N, Mastroeni P, Scott P, Raisen C, Mottram L, Fairweather NF, Wren BW, Parkhill J, Dougan G. Antibiotic treatment of Clostridium difficile carrier mice triggers a supershedder state, spore-mediated transmission, and severe disease in immunocompromised hosts. Infect Immun. 2009;77(9):3661–3669. doi: 10.1128/iai.00558-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Song X, Yang T, Chen Y, Gong Y, Yin X, Lu Z. A systematic review of antibiotic prescription associated with upper respiratory tract infections in China. Medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000003587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtfouse E, Dou S, Girardin C, Grably M, Balesdent J, Béhar F, Vandenbroucke M. Unexpected 13C-enrichment of organic components from wheat crop soils: evidence for the in situ origin of soil organic matter. Org Geochem. 1995;23:865–868. doi: 10.1016/0146-6380(95)80009-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtfouse E (2020) Methods, effects, and personal experiences on maintaining good immunity in the COVID-19 episode. Personal Communication

- Lippi D, Roberti di Sarsina P, D'Elios JP. Music and medicine. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2010;3:137–141. doi: 10.2147/jmdh.S11378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wan YH, Liu PP, Zhao JC, Lu GW, Qi JX, Wang QH, Lu XC, Wu Y, Liu WJ, Zhang BC, Yuen KY, Perlman S, Gao GF, Yan JH. A humanized neutralizing antibody against MERS-CoV targeting the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein. Cell Res. 2015;25(11):1237–1249. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel MJ, Broderick NA, Martens EC, Guillemin K. Reports from a healthy community: the 7th conference on beneficial microbes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2019;85(10):17. doi: 10.1128/aem.02562-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manohar A, Ahuja J, Crane JK. Immunotherapy for infectious diseases: past, present, and future. Immunol Invest. 2015;44(8):731–737. doi: 10.3109/08820139.2015.1093914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoy ML (2020) Passive immunization. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/immunization/passive-immunization

- Marovich M, Mascola JR, Cohen MS. Monoclonal antibodies for prevention and treatment of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(2):131–132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland LV. Beneficial microbes: health or hazard? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12(10):1069–1071. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012100-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehnaz S. Microbes - friends and foes of sugarcane. J Basic Microbiol. 2013;53(12):954–971. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201200299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel JS, Sfyroera G, Bartow-McKenney C, Gimblet C, Bugayev J, Horwinski J, Kim B, Brestoff JR, Tyldsley AS, Zheng Q, Hodkinson BP, Artis D, Grice EA. Commensal microbiota modulate gene expression in the skin. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0404-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moderna (2020) Moderna’s work on a COVID-19 vaccine candidate. https://www.modernatx.com/modernas-work-potential-vaccine-against-covid-19?utm_source=homepage&utm_medium=slider&utm_campaign=covid

- Molendijk I, van der Marel S, Maljaars PWJ. Towards a food pharmacy: immunologic modulation through diet. Nutrients. 2019;11(6):11. doi: 10.3390/nu11061239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morens DM, Fauci AS. Emerging pandemic diseases: how we got to COVID-19. Cell. 2020;183(3):837–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik S, Bouladoux N, Wilhelm C, Molloy MJ, Salcedo R, Kastenmuller W, Deming C, Quinones M, Koo L, Conlan S, Spencer S, Hall JA, Dzutsev A, Kong H, Campbell DJ, Trinchieri G, Segre JA, Belkaid Y. Compartmentalized control of skin immunity by resident commensals. Science. 2012;337(6098):1115–1119. doi: 10.1126/science.1225152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2014. J Nat Prod. 2016;79(3):629–661. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan AA, Corr SC. Establishing boundaries: the relationship that exists between intestinal epithelial cells and gut-dwelling bacteria. Microorganisms. 2019;7(12):12. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7120663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hanlon SJ, Rieux A, Farrer RA, Rosa GM, et al. Recent Asian origin of chytrid fungi causing global amphibian declines. Science. 2018;360(6389):621–627. doi: 10.1126/science.aar1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(5):362. doi: 10.7326/m20-3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa S, Stack ML, Bishai DM, Mirelman A, Friberg IK, Niessen L, Walker DG, Levine OS. During the ‘decade of vaccines’, the lives of 6.4 million children valued at $231 billion could be saved. Health Aff. 2011;30(6):1010–1020. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H, Peto R, Karim QA, Alejandria M, Henao-Restrepo AM, García CH, Kieny M-P, Malekzadeh R, Murthy S, Preziosi M-P, Reddy S, Periago MR, Sathiyamoorthy V, Røttingen J-A, Swaminathan S. Repurposed antiviral drugs for COVID-19—interim WHO SOLIDARITY trial results. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.10.15.20209817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlakis GN, Felber BK. A new step towards an HIV/AIDS vaccine. Lancet. 2018;392(10143):192–194. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31548-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfizer (2020) Our COVID-19 vaccine study—What’s next? https://www.pfizer.com/news/hot-topics/our_covid_19_vaccine_study_what_s_next

- Ramasamy MN, Minassian AM, Ewer KJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine administered in a prime-boost regimen in young and old adults (COV002): a single-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32466-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravelin T, Kylmä J, Korhonen T. Dance in mental health nursing: a hybrid concept analysis. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2006;27(3):307–317. doi: 10.1080/01612840500502940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhayat L, Maresca M, Nicoletti C, Perrier J, Brinch KS, Christian S, Devillard E, Eckhardt E. Effect of Bacillus subtilis strains on intestinal barrier function and inflammatory response. Front Immunol. 2019;10:564. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley J, Corkhill B, Morris C. The benefits of knitting for personal and social wellbeing in adulthood: findings from an international survey. Br J Occup Ther. 2013;76(2):50–57. doi: 10.4276/030802213X13603244419077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SA, Terry WD. Passive immunotherapy of cancer in animals and man. Adv Cancer Res. 1977;25:323–388. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60637-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roviello V, Roviello GN. Lower COVID-19 mortality in Italian forested areas suggests immunoprotection by Mediterranean plants. Environ Chem Lett. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01063-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusu A, Hancu G, Uivarosi V. Fluoroquinolone pollution of food, water and soil, and bacterial resistance. Environ Chem Lett. 2015;13(1):21–36. doi: 10.1007/s10311-014-0481-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel AJ, Meisel JS, Horwinski J, Zheng Q, Grice EA. Topical antimicrobial treatments can elicit shifts to resident skin bacterial communities and reduce colonization by Staphylococcus aureus competitors. Antimicrob Agents CH. 2017;61(9):e00774–00717. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00774-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassone-Corsi M, Raffatellu M. No vacancy: how beneficial microbes cooperate with immunity to provide colonization resistance to pathogens. J Immunol. 2015;194(9):4081–4087. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt TSB, Raes J, Bork P. The human gut microbiome: from association to modulation. Cell. 2018;172(6):1198–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopf JW, Kitajima K, Spicuzza MJ, Kudryavtsev AB, Valley JW. SIMS analyses of the oldest known assemblage of microfossils document their taxon-correlated carbon isotope compositions. PNAS. 2018;115(1):53–58. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718063115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltenrich N. Just what the doctor ordered: using parks to improve children’s health. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(10):A254–A259. doi: 10.1289/ehp.123-A254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi R, Shan C, Duan X, Chen Z, Liu P, Song J, Song T, Bi X, Han C, Wu L, Gao G, Hu X, Zhang Y, Tong Z, Huang W, Liu WJ, Wu G, Zhang B, Wang L, Qi J, Feng H, Wang F-S, Wang Q, Gao GF, Yuan Z, Yan J. A human neutralizing antibody targets the receptor-binding site of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;584(7819):120–124. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2381-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin E. Antimicrobials and antimicrobial resistant superbacteria. Ewha Med J. 2017;40(3):99–103. doi: 10.12771/emj.2017.40.3.99. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shoaie S, Ghaffari P, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Mardinoglu A, Sen P, Pujos-Guillot E, de Wouters T, Juste C, Rizkalla S, Chilloux J, Hoyles L, Nicholson JK, Consortium MI-O, Dore J, Dumas ME, Clement K, Backhed F, Nielsen J (2015) Quantifying diet-induced metabolic changes of the human gut microbiome. Cell Metab 22(2):320–331.10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sousa V, Santos E, Sgarbieri V. The importance of prebiotics in functional foods and clinical practice. Food Nutr Sci. 2011;2(2):133–144. doi: 10.4236/fns.2011.22019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sulakvelidze A, Alavidze Z, Morris JG. Bacteriophage therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(3):649–659. doi: 10.1128/aac.45.3.649-659.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton P, Boag JM. Status of vaccine research and development for Helicobacter pylori. Vaccine. 2019;37(50):7295–7299. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn BA, Walter LG, Arroll B, Tilyard MW, Russell DG. The green prescription study: a randomized controlled trial of written exercise advice provided by general practitioners. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(2):288–291. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To KK-W, Hung IF-N, Ip JD, Chu AW-H, Chan W-M, Tam AR, Fong CH-Y, Yuan S, Tsoi H-W, Ng AC-K, Lee LL-Y, Wan P, Tso E, To W-K, Tsang D, Chan K-H, Huang J-D, Kok K-H, Cheng VC-C, Yuen K-Y. COVID-19 re-infection by a phylogenetically distinct SARS-coronavirus-2 strain confirmed by whole genome sequencing. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ufnalska S. Why not encourage physical activity outdoors and inhaling through the uncovered nose during the coronavirus lockdown? Mater Sociomed. 2020;32:315–316. doi: 10.5455/msm.2020.32.315-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ufnalska S. Physical activity outdoors as an alternative to lockdown: the Three Cs strategy. Med Arch. 2020;74:399–402. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2020.74.399-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaara M. Agents that increase the permeability of the outer membrane. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56(3):395. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.3.395-411.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel EGHM, Muys T, van Dokkum W, Schaafsma G. Oligofructose stimulates calcium absorption in adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(3):544–548. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.3.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinderola G, Matar C, Perdigon G. Role of intestinal epithelial cells in immune effects mediated by gram-positive probiotic bacteria: Involvement of Toll-like receptors. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12(9):1075–1084. doi: 10.1128/cdli.12.9.1075-1084.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelker R. FDA approves bacteriophage trial. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. 2019;321(7):638–638. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MF, Wang JY, Li BC, Meng LX, Tian ZX. Recent advances in mechanism-based chemotherapy drug-siRNA pairs in co-delivery systems for cancer: a review. Colloids Surf B. 2017;157:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Liu S, Li G, Xiao J (2020b) Exercise regulates the immune system. Adv Exp Med Biol 1228:395–408. 10.1007/978-981-15-1792-1_27 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Peng Y, Xu H, Cui Z, Williams RO 3rd (2020a) The COVID-19 vaccine race: challenges and opportunities in vaccine formulation. AAPS PharmSciTech 21(6):225. 10.1208/s12249-020-01744-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- WHO (2019) World Health Organization. HIV drug resistance report 2019 https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/drugresistance/hivdr-report-2019/en/

- WHO (2021a) World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/

- WHO (2021b) World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 [PubMed]

- WHO (2020) World Health Organization. #HealthyAtHome—Physical activity. https://www.who.int/news-room/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/healthyathome/healthyathome---physical-activity

- Wildschutte JH, Williams ZH, Montesion M, Subramanian RP, Kidd JM, Coffin JM (2016) Discovery of unfixed endogenous retrovirus insertions in diverse human populations. PNAS 113(16):E2326–2334. 10.1073/pnas.1602336113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wojewodzic MW. Bacteriophages could be a potential game changer in the trajectory of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Phage. 2020;1(2):60–65. doi: 10.1089/phage.2020.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A, Jeang J, Cheng K, Cheng T, Yang B, Wu TC, Hung C-F. Current state in the development of candidate therapeutic HPV vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2016;15(8):989–1007. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2016.1157477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan F, Polk DB. Probiotic bacterium prevents cytokine-induced apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(52):50959–50965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207050200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, Heath AC, Warner B, Reeder J, Kuczynski J, Caporaso JG, Lozupone CA, Lauber C, Clemente JC, Knights D, Knight R, Gordon JI. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486(7402):222. doi: 10.1038/nature11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Lai H. Five phases music therapy (FPMT) in Chinese medicine: fundamentals and application. Open Access Libr J. 2017;04:1–11. doi: 10.4236/oalib.1104190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhao X, Zhu Y, Ma J, Ma H, Zhang H. Probiotic mixture protects dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis by altering tight junction protein expressions and increasing tregs. Mediat Inflam. 2018;2018:9416391. doi: 10.1155/2018/9416391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Z-P, Solonenko NE, Li Y-F, Gazitúa MC, Roux S, Davis ME, Van Etten JL, Mosley-Thompson E, Rich VI, Sullivan MB and Thompson LG (2020) Glacier ice archives fifteen-thousand-year-old viruses. bioRxiv: 2020.2001.2003.894675. 10.1101/2020.01.03.894675.

- Zuo T, Zhang F, Lui GCY, Yeoh YK, Li AYL, Zhan H, Wan Y, Chung ACK, Cheung CP, Chen N, Lai CKC, Chen Z, Tso EYK, Fung KSC, Chan V, Ling L, Joynt G, Hui DSC, Chan FKL, Chan PKS, Ng SC. Alterations in gut microbiota of patients with COVID-19 during time of hospitalization. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(3):944–955.e948. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]