Abstract

Human tau seeding and spreading occur following intracerebral inoculation of brain homogenates obtained from tauopathies in transgenic mice expressing natural or mutant tau, and in wild‐type (WT) mice. The present study was geared to learning about the patterns of tau seeding, the cells involved and the characteristics of tau following intracerebral inoculation of homogenates from primary age‐related tauopathy (PART: neuronal 4Rtau and 3Rtau), aging‐related tau astrogliopathy (ARTAG: astrocytic 4Rtau) and globular glial tauopathy (GGT: 4Rtau with neuronal deposits and specific tau inclusions in astrocytes and oligodendrocytes). For this purpose, young and adult WT mice were inoculated unilaterally in the hippocampus or in the lateral corpus callosum with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART, ARTAG and GGT cases, and were killed at variable periods of three to seven months. Brains were processed for immunohistochemistry in paraffin sections. Tau seeding occurred in the ipsilateral hippocampus and corpus callosum and spread to the septal nuclei, periventricular hypothalamus and contralateral corpus callosum, respectively. Tau deposits were mainly found in neurons, oligodendrocytes and threads; the deposits were diffuse or granular, composed of phosphorylated tau, tau with abnormal conformation and 3Rtau and 4Rtau independently of the type of tauopathy. Truncated tau at the aspartic acid 421 and ubiquitination were absent. Tau deposits had the characteristics of pre‐tangles. A percentage of intracellular tau deposits co‐localized with active (phosphorylated) tau kinases p38 and ERK 1/2. Present study shows that seeding and spreading of human tau into the brain of WT mice involves neurons and glial cells, mainly oligodendrocytes, thereby supporting the idea of a primary role of oligodendrogliopathy, together with neuronopathy, in the progression of tauopathies. In addition, it suggests that human tau inoculation modifies murine tau metabolism with the production and deposition of 3Rtau and 4Rtau, and by activation of specific tau kinases in affected cells.

Keywords: aging‐related tau astrogliopathy, globular glial tauopathy, primary age‐related tauopathy, seeding, spreading, tau, tauopathies

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases with abnormal protein aggregates are progressive disorders with specific vulnerability of selected regions, cell types including neurons and glial cells, and particular deposits, all of which are disease dependent. The formation of abnormal protein species leading to aggregates is an active and very complex process involving several steps 72.

One of the mechanisms operating in the progression of Alzheimer's disease (AD), tauopathies and other neurodegenerative diseases with abnormal protein aggregates is thought to occur by transcellular and transregional propagation of the abnormal protein, mimicking prion diseases 30, 54, 60. Several studies support the hypothesis of intercellular tau transmission in AD and tauopathies. The generation of transgenic mice expressing human tau in the entorhinal cortex demonstrates the spread of tau with age anterogradely from the entorhinal cortex to the dentate gyrus, CA1 region of the hippocampus and subiculum, and retrogradely to scattered neurons in the perirhinal and secondary somatosensory cortex 18, 56. Tau protein is axonally transferred from hippocampus neurons to neurons of distant brain regions such as the olfactory and limbic systems using a lentiviral‐mediated rat model 19.

Tau seeding has been produced following inoculation of preformed synthetic fibrils and with enriched tau fractions from human brain homogenates injected into the brain of transgenic mice overexpressing human normal or mutated tau. Inoculation of preformed synthetic tau fibrils into the hippocampus of human mutant P301S tau‐expressing transgenic mice induces tau pathology in connected brain regions including the locus ceruleus 40. Injection of tau fibrils into the locus ceruleus in P301S mice spreads through certain afferent and efferent connections but not to the hippocampus or entorhinal cortex 41. Similarly, intracerebral injection of preformed synthetic tau fibrils initiates widespread tauopathy and neuronal loss in the brains of P301L transgenic mice 64. Importantly, seeding along neuronal connections following intracerebral injection of tau synthetic preformed fibrils of P301S transgenic mice is associated with abnormal synaptic transmission, altered behavior and motor deficits 70. Seeding and spreading of abnormal tau also occurs after inoculation of brain homogenates from P301S transgenic mice, AD, and other tauopathies into the brain of transgenic mice overexpressing human normal tau or human‐mutated tau 2, 7, 13, 14, 15, 16. Deposits in inoculated animals seem to be disease dependent, which suggests the occurrence of different species or strains of tau depending on the disease 7, 13, 14, 15, 16. This is in line with a set of experiments showing that inoculation into the mouse brain of different artificially generated strains of tau produces variable types of neuronal deposits including neurofibrillary tangles, soma vs. axonal inclusions, grain‐like structures, dendritic and axonal threads and astrocytic plaques, with variable rates of propagation depending on the strains 45, 65.

Seeding also occurs after intracerebral inoculation into wild‐type (WT) mice of human tau from homogenates of AD and tauopathies with neuronal and glial involvement 5, 36, 61. The pattern of tau seeding and spreading using human brain homogenates enriched with tau fibrils from brains with tauopathy is also different from the patterns produced following inoculation of recombinant tau 36, 61, thus further supporting the idea that different species of tau have different properties.

All these experiments were performed using brain post‐mortem brain samples of AD or tauopathies with tau pathology in neurons and in glial cells. Abnormal tau in these paradigms can spread to resident neurons, astrocytes and oligodendroglia 5, 7, 13, 16, 61. Whether astrocytic tau alone is able to induce tauopathy has recently been assessed. Tau‐enriched fractions of brain homogenates from pure aging‐related tau astrogliopathy (ARTAG) with no associated neuronal tauopathy inoculated into the hippocampus of WT mice‐generated intracytoplasmic hyperphosphorylated tau inclusions in astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and neurons near the site of injection, and in nerve fiber tracts in the fimbria and corpus callosum 25. These observations show that astrocytes containing hyperphosphorylated tau have the capability of seeding tau to neurons and glial cells, thus highlighting the putatively cardinal role of astrocytopathy in the pathogenesis of certain tauopathies 25.

Considering this background, the present study examines tau seeding and spreading of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions of brain homogenates from primary age‐related 4Rtau+3Rtau neuronal tauopathy (PART), pure 4Rtau astrocytopathy (ARTAG) and glial globular tauopathy (GGT), a 4Rtau tauopathy with distinct deposits in oligodendrocytes and astrocytes, into the hippocampus and lateral corpus callosum of WT mice expressing murine tau. The purpose of the study was to analyze whether seeding and spreading depend on (i) different human pathological tau strains, including tau isoforms linked to tau repeats; (ii) origin of tau (neuronal or glial); and/or (iii) tau substrate represented by murine tau instead of human normal or mutated tau as the target of tau seeding and spreading.

Material and methods

Human cases

Brain tissue was obtained from the Institute of Neuropathology HUB‐ICO‐IDIBELL Biobank following the guidelines of Spanish legislation on this matter (Real Decreto de Biobancos 1716/2011) and approval of the local ethics committee. One hemisphere was immediately cut in coronal sections, 1 cm thick, and selected areas of the encephalon were rapidly dissected, frozen on metal plates over dry ice, placed in individual air‐tight plastic bags and stored at −8°C until use for biochemical studies. The other hemisphere was fixed by immersion in 4% buffered formalin for 3 weeks for morphological studies; sections from 20 representative brain regions were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and Klüver–Barrera or processed for immunohistochemistry for microglia Iba1, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), β‐amyloid, AT8, 3Rtau, 4Rtau, phospho‐tau Thr181, Alz50 (tau amino acids 5–15), MC‐1 (tau amino acids 312–322), tau C‐3 (truncated tau at aspartic acid 421), α‐synuclein and TDP‐43 using EnVision+ System peroxidase (Dako) and diaminobenzidine and H2O2, or diaminobenzidine, NH4NiSO4, and H2O2. Details of the antibodies are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the antibodies used.

| Antibody | Mono‐/polyclonal | Dilution | Supplier | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β‐amyloid | Monoclonal | 1:50 | Dako | Glostrup, DK |

| α‐synuclein | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:500 | Chemicon, Merck‐Millipore | Billerica, MA, USA |

| TDP‐43 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:200 | Abcam | Cambridge, UK |

| Iba1 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:1000 | Wako | Richmond, VA, USA |

| 4Rtau | Monoclonal | 1:50 | Merck‐Millipore | Billerica, MA, USA |

| 3Rtau | Monoclonal | 1:800 | Merck‐Millipore | Billerica, MA, USA |

| Phospho‐tau Thr181 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:50 | Cell Signaling | Danvers, MA, USA |

| Phospho‐tau Ser422 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:1000 | Thermo Fisher | Waltham, MA, USA |

| AT8 (Ser202/Thr205) | Monoclonal | 1:50 | Innogenetics | Ghent, BE |

| Alz50 (aa 5–15) | Monoclonal | 1:20 | Dr. Peter Davies | New York, USA |

| MC‐1 (aa 312–322) | Monoclonal | 1:50 | Dr. Peter Davies | USA |

| tau‐C3 (tr Asp421) | Monoclonal | 1:300 | Abcam | Cambridge, UK |

| Ubiquitin | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:500 | Dako | Glostrup, DK |

| Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:500 | Dako | Glostrup, DK |

| P38‐P (Thr180‐Tyr182) | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:100 | Cell Signaling | Danvers, MA, USA |

| ERK 1/2‐P (Thr202/Tyr204) | Monoclonal | 1:50 | Merck‐Millipore | Billerica, MA, USA |

| p38 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:50 | Elabscience | Bionova, Madrid, Spain |

| ERK 1/2 | Monoclonal | 1:100 | Sigma Aldrich‐Merck | Darmstad, GE |

| Olig2 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:500 | Abcam | Cambridge, UK |

| NeuN | Monoclonal | 1:100 | Merck‐Millipore | Billerica, MA, USA |

PART cases were selected on the basis of pure neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) pathology in old age involving the temporal lobe with no accompanying tauopathy and without β‐amyloid deposits 17. NFT stages in PART cases were categorized according to Braak and Braak modified for paraffin sections 8, 9; cases were categorized as stage IV: one man aged 68 years and one woman aged 72 years. They had no apparent neurological deficits; the diagnosis was made at the post‐mortem neuropathological examination.

ARTG cases were defined by the presence of two types of tau‐bearing astrocytes: thorn‐shaped astrocytes (TSAs) and granular/fuzzy astrocytes (GFAs) in the brain of old‐aged individuals 49, 52. ARTAG often accompanies other tauopathies in old age; the present study used three pure ARTAG cases with no accompanying tauopathy excepting PART stage I (ref 25, cases 2, 3 and 4); cases were two women aged 78 and 87, and one man 68 years old. The patients had no neurological symptoms and the diagnosis was made in the post‐mortem neuropathological examination.

GGT cases corresponded to two kindred with familial globular tauopathy linked to P301T mutation in MAPT. The first patient was a man 49‐year‐old suffering from progressive gait disturbance starting at the age of 44, followed by cognitive decline and abnormal behavior, non‐fluent speech with echolalia, paresis of the vertical gaze and tetraparesis with severe spasticity. His mother was diagnosed with a progressive corticobasal syndrome at the age of 65 and died 4 years later. The second patient was a 43‐year‐old woman with two brothers, the mother and two uncles affected by similar disease, and three older sisters who were spared. She suffered from rapid cognitive decline and speech difficulties, aggressive behavior, rigidity, bradykinesia, alien hand phenomenon and reflex myoclonus.

In addition, one case of AD (stage VI/C of Braak: one 82‐year‐old man) and one control aged 62 were used as positive and negative tauopathy controls, respectively.

Cases with associated pathologies such as vascular diseases (excepting mild atherosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis), TDP‐43 proteinopathy, metabolic syndrome and hypoxia were excluded from the present study.

The cause of death was variable and included bronchopneumonia, respiratory failure, cardiac arrest, kidney failure, pulmonary thromboembolism and metastatic carcinoma. Post‐mortem delay between death and tissue processing was between 4 and 18 h.

Western blotting of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions

Human brain samples used for brain inoculation in mice were obtained from the hippocampus in the two cases of PART, AD and control; temporal white matter in the three cases of ARTAG; and prefrontal cortex area 8 in the two GGT cases. Frozen samples of about 1 g were lysed in 10 volumes (w/v) with cold suspension buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 0.8 M NaCl, 1 mM EGTA) supplemented with 10% sucrose, protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, GE). The homogenates were first centrifuged at 20 000 × g for 20 minutes (Ultracentrifuge Beckman with 70Ti rotor) and the supernatant (S1) was saved. The pellet was re‐homogenized in five volumes of homogenization buffer and re‐centrifuged at 20 000 × g for 20 minutes (Ultracentrifuge Beckman with 70Ti rotor). The two supernatants (S1 + S2) were then mixed and incubated with 0.1% N‐lauroylsarkosynate (sarkosyl) for 1 h at room temperature while being shaken. Samples were then centrifuged at 100 000 × g for 1 h (Ultracentrifuge Beckman with 70Ti rotor). Sarkosyl‐insoluble pellets (P3) were re‐suspended (0.2 mL/g) in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4). Protein concentrations were quantified with the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) assay (Pierce, Waltham, MA).

Sarkosyl‐insoluble and sarkosyl‐soluble fractions were processed for western blotting.

Samples were mixed with loading sample buffer and heated at 95°C for 5 minutes. 60 μg of protein was separated by electrophoresis in SDS‐PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (200 mA per membrane, 90 minutes). The membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 5% nonfat milk in TBS containing 0.2% Tween and were then incubated with the primary antibody anti‐tau Ser422 (diluted 1:1,000; Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA, USA). After washing with TBS‐T, blots were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (anti‐rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase diluted at 1:2,000, DAKO, DE) for 45 minutes at room temperature. Immune complexes were revealed by incubating the membranes with chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham, GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) 25.

Tansmission electron microscopy (TEM) procedures

Brain extract solutions were fixed to carbon forward‐coated copper supports, and negative staining was performed using a 2% uranyl acetate stain (pH 7.4), after which samples were placed in silica‐based desiccant for a minimum of 2 h. Finally, we proceeded to TEM observation using a Jeol JEM‐1010 electron microscope.

Thioflavin T (ThT) amyloid quantification assay

ThT stock solution was prepared at 2.5 mM (dissolved in 10 mM phosphate buffer (potassium), 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.0) and preserved in single aliquot at −80°C. The ThT assay was performed by dissolving 0.2 µL of brain sample in 0.2 mL of freshly prepared ThT (final concentration 30 µM) followed by quantification using an absorbance/excitation (445/485) microplate reader (Tecan Infinite M200Pro) in 96 flat‐bottom polystyrol plates (Nunclor). Plates were prepared and incubated at 37°C and readings were taken each hour during 15–16 h.

Animals and tissue processing

Wild‐type C57BL/6 mice from our colony were used. All animal procedures were carried out following the guidelines of the European Communities Council Directive 2010/63/EU and with the approval of the local ethical committee (University of Barcelona, Spain). The age and number of animals, the time of survival and the type of inoculum are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mice used in the study showing type of inoculum, age of inoculation, age of killing and survival. Inoculum refers to sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions of the corresponding human tauopathies (PART, ARTAG, GGT and AD) with the exception of ARTAGs, GGTs and ADs which indicate sarkosyl‐soluble fractions of GGT, ARTAG and AD cases, respectively; control refers to the inoculation of brain homogenates from normal brains and vehicle.

| Inoculum | Site | Age inocul month | Age killed month | Survival months | Tau deposits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PART | Hippocampus | 3 | 10 | 7 | ++ |

| Hippocampus | 3 | 10 | 7 | ++ | |

| Hippocampus | 12 | 19 | 7 | ++ | |

| Hippocampus | 12 | 19 | 7 | ++ | |

| Corpus callosum | 12 | 19 | 7 | +++ | |

| Corpus callosum | 12 | 19 | 7 | +++ | |

| Corpus callosum | 12 | 18 | 6 | +++ | |

| Corpus callosum | 12 | 18 | 6 | +++ | |

| ARTAG | Hippocampus | 7 | 10 | 3 | + |

| Hippocampus | 7 | 10 | 3 | + | |

| Hippocampus | 7 | 10 | 3 | − | |

| Hippocampus | 3 | 10 | 7 | ++ | |

| Hippocampus | 3 | 10 | 7 | ++ | |

| Hippocampus | 3 | 10 | 7 | ++ | |

| Hippocampus | 3 | 10 | 7 | ++ | |

| Hippocampus | 12 | 19 | 7 | ++ | |

| Hippocampus | 12 | 19 | 7 | ++ | |

| Corpus callosum | 7 | 10 | 3 | ++ | |

| Corpus callosum | 12 | 19 | 7 | +++ | |

| Corpus callosum | 12 | 19 | 7 | +++ | |

| Corpus callosum | 12 | 19 | 7 | +++ | |

| GGT | Corpus callosum | 7 | 11 | 4 | + |

| Corpus callosum | 7 | 11 | 4 | + | |

| Corpus callosum | 7 | 11 | 4 | + | |

| Corpus callosum | 7 | 11 | 4 | + | |

| Corpus callosum | 12 | 18 | 6 | ++ | |

| Corpus callosum | 12 | 18 | 6 | ++ | |

| Corpus callosum | 12 | 18 | 6 | − | |

| Corpus callosum | 12 | 18 | 6 | + | |

| AD | Hippocampus | 7 | 11 | 4 | ++ |

| Hippocampus | 7 | 11 | 4 | ++ | |

| Corpus callosum | 7 | 11 | 4 | ++ | |

| ARTAGs | Corpus callosum | 12 | 19 | 7 | − |

| GGTs | Corpus callosum | 7 | 11 | 4 | − |

| Corpus callosum | 7 | 11 | 4 | − | |

| Corpus callosum | 7 | 11 | 4 | − | |

| ADs | Hippocampus | 7 | 11 | 4 | − |

| Hippocampus | 7 | 11 | 4 | − | |

| Corpus callosum | 7 | 11 | 4 | − | |

| control | Hippocampus | 7 | 10 | 3 | − |

| Hippocampus | 3 | 10 | 7 | − | |

| Corpus callosum | 12 | 18 | 6 | − | |

| vehicle | Hippocampus | 3 | 10 | 7 | − |

| Corpus callosum | 7 | 11 | 4 | − | |

| Corpus callosum | 7 | 11 | 4 | − |

The column on the right is a brief summary of the efficiency of the injection (amount of tau deposits) in every mouse. Signs indicate: − absence; + a few; ++ many, +++ abundant tau deposits related to the inoculation independently of the type of deposit in neuron, glial cell or thread.

Inoculation into the hippocampus and lateral corpus callosum

Sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions isolated from PART, ARTAG, GGT and AD cases were used as inoculum. Sarkosyl‐soluble fraction of ARTAG, GGT and AD (ARTAGs, GGTs and ADs) were inoculated in another group of animals. Other animals were injected with homogenates from one control brain or with 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) as vehicle. Mice were deeply anesthetized by intraperitoneal ketamin/xylazine/buprenorphine cocktail injection and placed in a stereotaxic frame after assuring lack of reflexes. Intracerebral injections were done using a Hamilton syringe; the coordinates for hippocampal injections were −1.9 AP; ±1.4 ML relative to Bregma and −1.5 DV from the dural surface; the coordinates for lateral corpus callosum inoculations were −1.9 AP; ±1.4 ML relative to Bregma; and −1.0 DV from the dural surface 63. A volume of 1.5 µL was injected at a rate of 0.05 µL/minutes in the hippocampus, and 1.2 µL was injected at a rate of 0.1 µL/minutes in the corpus callosum. The syringe was retired slowly over a period of 10 minutes to avoid leakage of the inoculum. Each mouse was injected with inoculum from a single PART, ARTAG, or GGT case. Following surgery, the animals were kept in a warm blanket and monitored until they recovered from the anesthesia. Carprofen analgesia was administered immediately after surgery and once a day during the next two consecutive days. Animals were housed individually with full access to food and water.

Tissue processing

Animals were killed under anesthesia and the brains were rapidly fixed with paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer and embedded in paraffin. Consecutive serial sections 4 μm thick were obtained with a sliding microtome. De‐waxed sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Thioflavin S or processed for immunohistochemistry using the antibodies AT8, anti‐4Rtau, anti‐3Rtau, MC‐1 and tau‐C3, in addition to GFAP for reactive astrocytes and Iba1 for microglia. Following incubation with the primary antibody, the sections were incubated with EnVision + system peroxidase for 30 minutes at room temperature. The peroxidase reaction was visualized with diaminobenzidine and H2O2. Control of the immunostaining included omission of the primary antibody; no signal was obtained following incubation with only the secondary antibody. The specificity of 3Rtau and 4Rtau antibodies in mice was tested in coronal sections of the brain, cerebellum and brainstem of P301S transgenic mice aged 8–9 months 57. Tau‐immunoreactive inclusions in animals expressing mutant human 4Rtau were stained with anti‐4Rtau antibodies but were negative with anti‐3Rtau antibodies.

Double‐labeling immunofluorescence was carried out on de‐waxed sections, 4 μm thick, which were stained with a saturated solution of Sudan black B (Merck, DE) for 15 minutes to block autofluorescence of lipofuscin granules present in cell bodies, and then rinsed in 70% ethanol and washed in distilled water. The sections were boiled in citrate buffer to enhance antigenicity and blocked for 30 minutes at room temperature with 10% fetal bovine serum diluted in PBS. Then, the sections were incubated at 4°C overnight with combinations of AT8 and one of the following primary antibodies: GFAP, Iba‐1, Olig2 and p38‐P (Thr180‐Tyr182). Other sections were immunostained with anti‐phospho‐tauThr181, and anti‐NeuN and anti‐ERK‐P 1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204). Another set of sections was incubated with non‐phosphorylated p38 and non‐phosphorylated ERK 1/2 and phospho‐tau (see Table 1 for the characteristics of the antibodies). After washing, the sections were incubated with Alexa488 or Alexa546 fluorescence secondary antibodies against the corresponding host species. Nuclei were stained with DRAQ5TM. Then, the sections were mounted in Immuno‐FluoreTM mounting medium, sealed and dried overnight. Sections were examined with a Leica TCS‐SL confocal microscope.

Maps representing the localization and distribution of tau deposits were taken from the atlas of Paxinos and Franklin 63.

Semi‐quantitative studies were carried in the ipsilateral corpus callosum in three nonconsecutive sections per case using double‐labeling immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. Data were expressed as the percentage of oligodendrocytes (as revealed with the Olig2 antibody) with tau deposits (as seen with the antibody AT8) compared with the total number of oligodendrocytes in the same field. Regarding the number of glial cells co‐expressing phospho‐tau and phospho‐p38, data were expressed as the percentage of tau‐positive cells containing active p38 from the total number of tau‐containing cells in three nonconsecutive sections in every case.

In situ end‐labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation (ApoptTag® peroxidase in situ apoptosis detection kit, Merck) was used to visualize apoptotic cells. The brains of newborn irradiated rats (2Gys) with a survival time of 24 h where paraformaldehyde fixed and paraffin embedded; de‐waxed sections were processed in parallel with tissue samples from inoculated mice and used as positive controls of apoptosis.

Results

Neuropathological characteristics of human samples

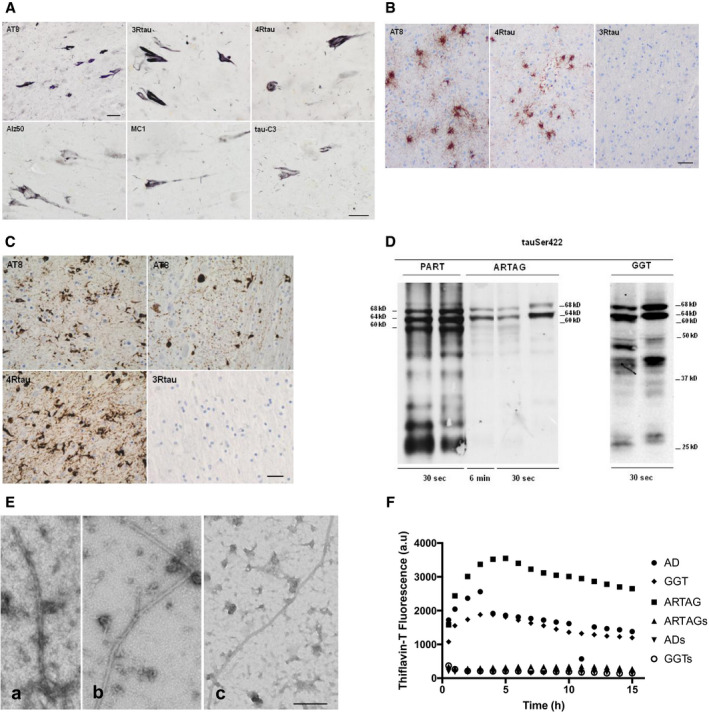

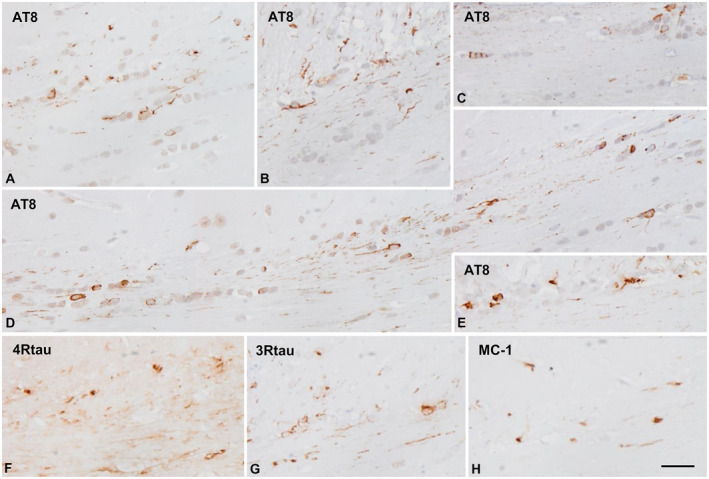

PART cases were characterized by neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in neurons of the entorhinal and transentorhinal cortices, hippocampus and deep regions of the temporal cortex, and by the absence of β‐amyloid plaques in all regions. Other regions affected were the locus ceruleus, raphe nuclei, amygdala and Meynert nucleus. NFTs were stained with antibody AT8 and with antibodies against 3Rtau and 4Rtau; NFTs were also positive with phospho‐specific anti‐tauThr181 and anti‐tauSer422 antibodies, and with conformational antibodies Alz50 (amino acids 5–10) and MC‐1 (amino acids 312–322). Most NFTs were also immunoreactive with antibody tau‐C3 directed against truncated tau at aspartic acid 421 (Figure 1A), and with anti‐ubiquitin antibodies.

Figure 1.

A. PART cases are characterized by the presence of neurofibrillary tangles only in the CA1 region of the hippocampus which are stained with antibodies AT8, anti‐3Rtau, anti‐4Rtau, Alz50 (amino acids 5–10), MC‐1 (amino acids 312–322) and tau‐C3 (truncated tau at C‐terminus, aspartic acid 421). Paraffin sections visualized with diaminobenzidine, NH4NiSO4 and H2O2 without hematoxylin counterstaining; bar = 25 μm, excepting AT8, bar = 45 μm. B. ARTAG cases with thorn‐shaped astrocytes (TSAs) contain hyperphosphorylated tau as revealed with antibody AT8, and 4Rtau. TSAs do not contain 3Rtau. Paraffin sections visualized with diaminobenzidine with slight hematoxylin counterstaining; bar = 25 μm. C. GGT cases showing neurofibrillary tangles and globular astrocytic inclusions in the cerebral cortex, and globular oligodendroglial inclusions in white matter stained with antibody AT8. These inclusions are immunoreactive with anti‐4Rtau antibodies but negative with anti‐3Rtau antibodies. Paraffin sections visualized with diaminobenzidine with slight hematoxylin counterstaining; bar = 25 μm. D. Sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions of brain homogenates blotted with anti‐tauSer422 in PART, ARTAG and GGT cases. The band pattern of PART is characterized by three bands of 68, 64 and 60 kDa, a weak upper band of 73 kDa and several lower bands of fragmented tau between 50 kDa, including strong bands of about 25 kDa. Pure ARTAG cases are characterized by two bands of 68 and 64 kDa, and no lower bands of truncated tau. GGT cases show bands of 68 and 64 kDa, bands between 50 and 37 kDa and strong bands of truncated tau of about 20 kDa. The amount of phospho‐tau is variable depending on the disease, much higher in PART and GGT than in ARTAG as revealed with exposure times of 30 s with similar protein loading in every lane. E. TEM of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from AD/PART (a), ARTAG (b) and GGT (c) showing the presence of specific fibrils; bar = 200 nm. F. ThT amyloid quantification assay shows the presence of thioflavin positivity in sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from AD, ARTAG and GGT cases whereas soluble fractions of the same cases are negative.

ARTAG cases were selected as pure forms with no other tau pathology in neurons and glial cells excepting PART stage I. Samples for inoculation corresponded to the white matter of the temporal lobe with large amounts of thorn‐shaped astrocytes (TSAs). These astrocytes were stained with antibody AT8, conformational antibodies Alz50 and MC‐1 and 4Rtau, but they were negative with anti‐3Rtau antibodies and with antibody tau‐C3; ubiquitin immunostaining was negative (Figure 1B).

GGT cases showed (i) neurofibrillary tangles in prefrontal cortex, motor cortex, primary sensory cortex, hippocampus, Meynert nucleus, striatum, substantia nigra, locus ceruleus, pontine nuclei and anterior horn of the spinal cord; (ii) globular astrocytic inclusions (GAIs) in the same regions; and (iii) globular oligodendroglial inclusions (GOIs) and coiled bodies in all these regions, excepting the locus ceruleus. GOIs and coiled bodies were abundant in the cerebral white matter. Neuronal and glial inclusions were stained with antibodies AT8, anti‐4Rtau, anti‐tauThr181, anti‐tauSer422, Alz50 and MC‐1. Inclusions were tau‐C3 positive in two cases but only rarely positive in the other two cases. Inclusions were negative with anti‐3Rtau antibodies (Figure 1C). Tau inclusions were positive with anti‐ubiquitin antibodies.

Characterization of tau deposits in the present series was consistent with data reported elsewhere 27 and summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of tau deposits in neurons and glial cells in AD, PART, ARTAG and GGT, and in WT mice unilaterally inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions of the respective human tauopathies in the hippocampus or in the corpus callosum.

| Cell type | tau‐Thr181 | AT8 | MC1 | 3Rtau | 4Rtau | Tau C‐3 | Ubiquitin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | Neuron | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Astrocyte | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Oligodendrocyte | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| PART | Neuron | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Astrocyte | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Oligodendrocyte | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| ARTAG | Neuron | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Astrocyte | + | + | + | − | + | +/− | − | |

| Oligodendrocyte | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| GGT | Neuron | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Astrocyte | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Oligodendrocyte | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| AD mice | Neuron | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Astrocyte | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | |

| Oligodendrocyte | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| PART mice | Neuron | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Astrocyte | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | |

| Oligodendrocyte | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| ARTAG mice | Neuron | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Astrocyte | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | |

| Oligodendrocyte | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| GGT mice | Neuron | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| Astrocyte | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | |

| Oligodendrocyte | + | + | + | +/− | + | − | − |

The sign + indicates presence and − absence of immunoreactivity. The sign / in the file of astrocytes in inoculated mice indicates that the small number of positive cells, if any, made it impossible to characterize the deposits in these cells; the sign / referring to neurons in mice inoculated with GGT homogenates indicates “not applicable” because the inoculation was carried out only in the corpus callosum.

Biochemical and morphological characteristic of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions of human brain homogenates

Sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions of brain homogenates blotted with anti‐tauSer422 showed disease‐specific band patterns. PART cases were characterized by three bands of 68, 64 and 60 kDa, a weak upper band of 73 kDa and several lower bands of fragmented tau between 50 and 25 kDa. Strong lower bands stained with anti‐tauSer422 indicated truncated tau at the C‐terminal. This pattern is typical of 4Rtau+3Rtau tauopathies (Figure 1D), and identical to that seen in AD (not shown).

Pure ARTAG cases were characterized by two bands of 68 and 64 kDa, and no lower bands of truncated tau even with longer times of exposure. The pattern was typical of 4Rtau tauopathies lacking tau truncation (Figure 1D).

GGT cases showed bands of 68 and 64 kDa in every case, and bands of lower molecular weight between 37 and 50 kDa, as well as strong bands of about 20 kDa consistent with truncated tau at the C‐terminal as revealed with the anti‐tauSer422 antibody. The pattern was typical of 4Rtau tauopathies with variable presence of truncated tau (Figure 1D).

TEM analysis showed paired helical filaments in AD, right tubules in ARTAG, and right tubules with smaller diameter than those of AD and ARTAG in GGT‐insoluble fractions (Figure 1E). No fibrils were identified in soluble fractions from the same cases (data not shown).

ThT amyloid quantification assay revealed positive curves of amyloid fibrils in sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from AD/PART, ARTAG and GGT cases. In contrast, the profiles of the soluble fractions of the same cases were flat (Figure 1F).

Mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART homogenates

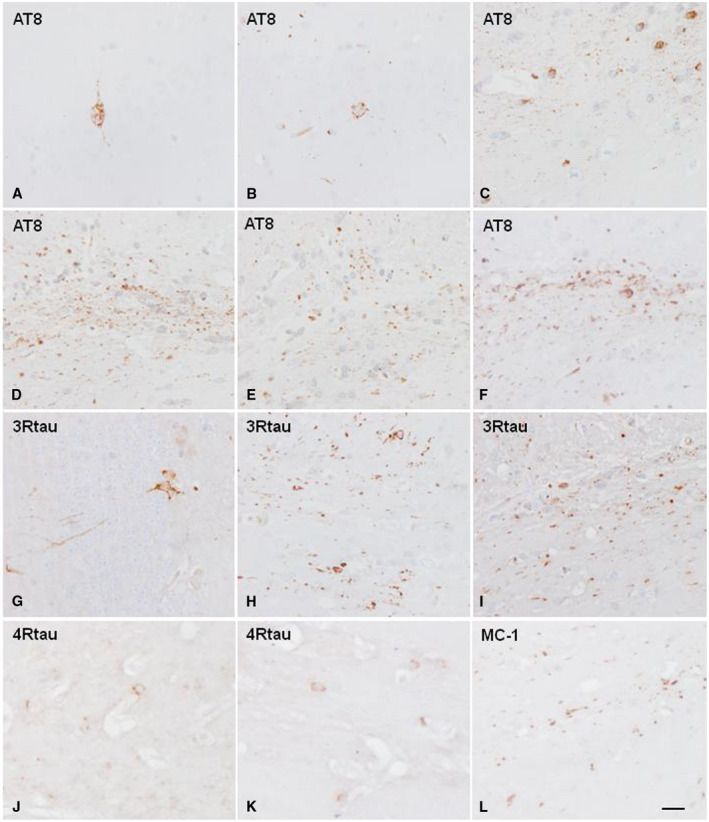

Two series of mice were unilaterally inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from two PART cases: i. mice aged 3 months and killed at the age of 10 months, and ii: mice aged 12 months and killed at 18–19 months. Following inoculation into the hippocampus, similar patterns were seen in young and adult animals injected at 3 or at 12 months, respectively, and killed 7 months later. Tau‐immunoreactive cells, as revealed with the AT8 antibody and anti‐tauThr181, were seen in ipsilateral neurons of the CA1 region of the hippocampus and dentate gyrus, and in glial cells in the fimbria and corpus callosum. Tau deposits extended to the middle region and the contralateral corpus callosum, and to scattered neurons and fibers in the septal nuclei and periventricular hypothalamus. Tau‐containing neurons and glial cells (mainly coiled bodies) were also stained with anti‐3Rtau and anti‐4Rtau antibodies, and with MC‐1 antibodies but not with antibodies directed against truncated tau (tau‐C3) and against ubiquitin (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hyperphosphorylated tau‐containing cells and threads following unilateral intrahippocampal injection of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART cases into WT mice inoculated at 12 months and killed at the age of 19 months (7 months survival). A, B, G. neurons in the hippocampus; C, H, I. glial cells and threads in the ipsilateral fimbria; D–F and J–L. glial cells and threads in the corpus callosum. D. ipsilateral corpus callosum; E. middle region of the corpus callosum; F. contralateral corpus callosum radiation. Paraffin sections immunostained with antibodies AT8, anti‐3Rtau, anti‐4Rtau and MC‐1, slightly counterstained with hematoxylin; A–L, bar in L = 25 μm.

Following inoculation into the lateral corpus callosum in mice aged 12 months and killed 6–7 months later, large numbers of glial cells and threads in the ipsilateral, middle region and contralateral corpus callosum were immunostained with AT8, anti‐tauThr181, anti‐3Rtau, anti‐4Rtau and MC‐1 antibodies; tau‐C3 and ubiquitin immunostaining were negative.

Mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from ARTAG homogenates

Three series of mice were unilaterally inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from three ARTAG cases: (i) mice aged 7 months and killed at 10 months, (ii) mice aged 3 months and killed at the age of 10 months and (iii) mice aged 12 months and killed at 19 months. This procedure covered (i) short postinoculation periods and (ii) long postinoculation periods in young and adult mice. Inoculation sites were the hippocampus and the lateral corpus callosum.

Mice inoculated into the hippocampus at the age of 7 months and killed 3 months later showed tau‐immunoreactive neurons in the CA1 region of the hippocampus and dentate gyrus, and in glial cells and threads in the fimbria and ipsilateral corpus callosum.

Mice inoculated in the hippocampus at the age of 3 months and killed at the age of 10 months, and mice inoculated at 12 months and killed at the age of 19 months (survival 7 months), showed tau‐immunoreactive neurons, as revealed with AT8 and anti‐tauThr181 antibodies, in the CA1 region of the hippocampus and dentate gyrus, glial cells and threads in the fimbria and ipsilateral corpus callosum, as well as glial cells in the middle region and contralateral corpus callosum (Figure 3). Tau‐immunoreactive fibers were also seen in the periventricular hypothalamus in the septal nuclei (see Figure 5A,B). Tau‐containing neurons, thread fibers and glial cells were stained with anti‐3Rtau and anti‐4Rtau antibodies, and with MC‐1antibodies, but not with antibodies directed against truncated tau and ubiquitin (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Hyperphosphorylated tau‐containing cells and threads following unilateral intrahippocampal injection of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from ARTAG cases into WT mice aged 12 months and killed at the age of 19 months (7 months survival). A, B, G, I. hippocampus; C, H. fimbria; C–F, J, K. corpus callosum. Tau‐containing neurons and glial cells are stained with anti‐4Rtau and with anti‐3Rtau antibodies. Paraffin sections immunostained with antibodies AT8, anti‐3Rtau, anti‐4Rtau and MC‐1, slightly counterstained with hematoxylin; A–L, bar L = 25 μm.

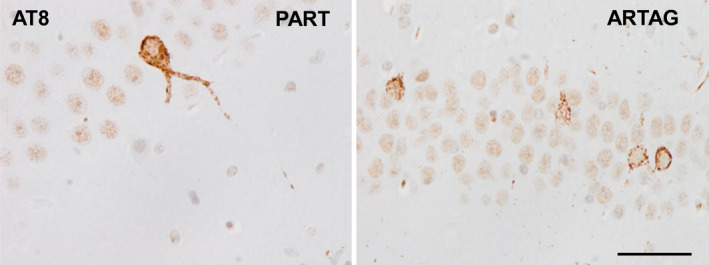

Figure 5.

Hyperphosphorylated tau deposits in neurons of the hippocampus in WT mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART and ARTAG cases at the age of 12 months and killed 7 months later. Tau deposits are diffuse or fine granular. Flame‐like appearance is absent. AT8 immunohistochemistry, paraffin sections slightly counterstained with hematoxylin; bar = 30 μm.

One mouse inoculated in the corpus callosum at the age of 7 months and killed 3 months later showed immunoreactive glial cells and threads limited to the ipsilateral and middle regions of the corpus callosum. However, large numbers of glial cells and threads were abundant along the ipsilateral, middle region and contralateral corpus callosum following unilateral inoculation into the corpus callosum in mice aged 12 months and killed at the aged of 18–19 months (survival 7 months). Tau deposits were labeled with AT8, anti‐tauThr181, anti‐3Rtau, anti‐4Rtau and MC‐1, but not with tau‐C3 and ubiquitin antibodies.

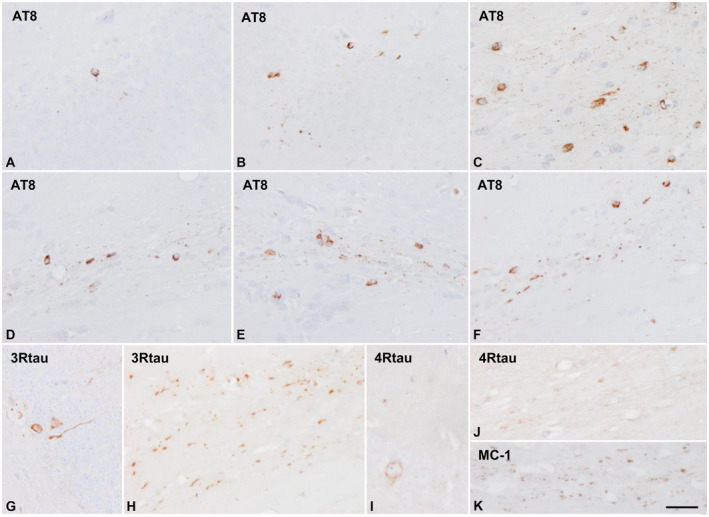

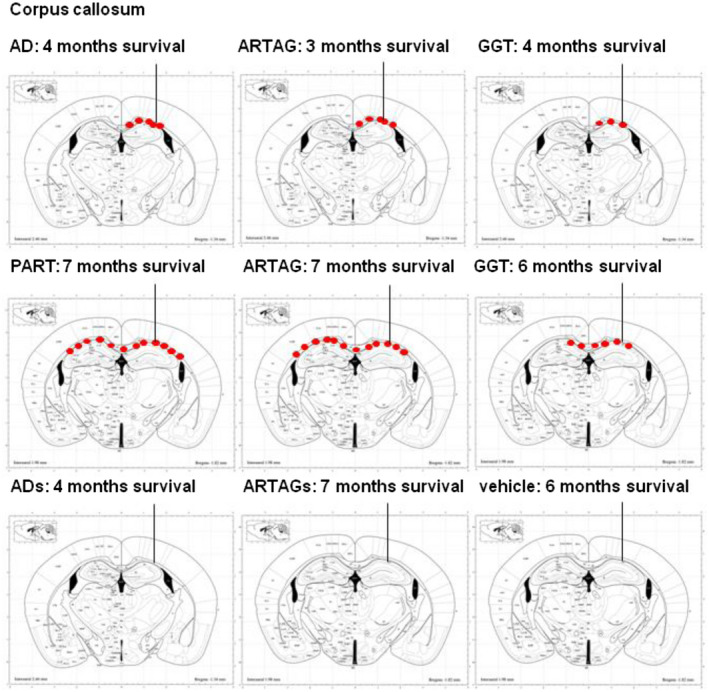

Mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from GGT homogenates

Mice unilaterally inoculated in the lateral corpus callosum at the age of 7 months and killed 4 months later showed tau‐immunoreactive deposits in glial cells and threads in the ipsilateral and middle region of the corpus callosum. Mice unilaterally inoculated in the lateral corpus callosum at the age of 12 months and killed 6 months later showed larger numbers of glial cells and threads in the middle regions and in the contralateral corpus callosum at long distances as revealed with AT8 and anti‐tauThr181 antibodies. Glial inclusions had the morphology of coiled bodies. The majority of inclusions were 4Rtau‐ but 3Rtau‐immunoreactive deposits were also seen in glial cells and threads. Only a few inclusions were stained with MC‐1 antibodies whereas tau‐C3 immunostaining was negative (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Hyperphosphorylated tau‐containing cells and threads following unilateral intrahippocampal injection of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from GGT cases into WT mice at the age of 7 months and killed at the age of 11 months (4 months survival) (A–C), and inoculated at the age of 12 months and killed at the age of 18 months (6 months survival) (D–H). Rows of glial cells and threads are stained along the ipsilateral corpus callosum (A–C), and along the contralateral corpus callosum with longer time of survival (D, E). The majority of cells and fibers are stained with anti‐4Rtau antibodies (F) but smaller numbers of glial cells and fibers are also stained with anti‐3Rtau antibodies. A minority of glial cells and fibers contain tau with abnormal conformation as revealed with the antibody MC‐1. Paraffin sections immunostained with antibodies AT8, anti‐3Rtau, anti‐4Rtau and MC‐1, slightly counterstained with hematoxylin; bar = 25 μm.

Mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from AD homogenates

Two mice were inoculated into the hippocampus and one mouse into the corpus callosum at the age of 7 months; mice were killed at the age of 11 months. Mice inoculated in the hippocampus and corpus callosum with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from AD showed the same changes as those seen in mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from ARTAG and GGT cases surviving 3–4 months. Labeled neurons and oligodendroglia were positive with AT8, anti‐tauThr181, anti‐4Rtau, anti‐3Rtau and MC‐1 antibodioes, but negative with anti‐ubiquitin and tau‐C3 antibodies (images not shown).

Control mice and mice inoculated with soluble fractions from AD, ARTAG and GGT cases

Animals inoculated with vehicle did not show tau pathology. Mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐soluble fractions in the hippocampus and corpus callosum from AD, ARTAG and GGT cases did not show tau deposits (data not shown).

General neuropathological aspects following inoculation

Apoptosis, as assessed with the method of in situ end‐labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation was not seen in inoculated mice at the time points examined in the present study. Reactive astrogliosis and microgliosis, as revealed with GFAP and Iba1 immunohistochemistry, were absent. Regarding thioflavin S staining, only very rarely did neurons show fluorescence in the ipsilateral hippocampus following unilateral injection of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from AD, PART and ARTAG cases; comparative analysis of immediate sections stained with AT8 antibodies revealed lack of fluorescence in the majority of tau‐containing neurons. The assessment of fluorescence in glial cells in the white matter was hampered by the fluorescence of myelin. Lack of fluorescence with thioflavin was agreeing with the diffuse or fine granular tau deposits in tau‐containing neurons (Figure 5) in inoculated mice which was consistent with pre‐tangle rather than with tangle stages of hyperphosphorylated tau deposition.

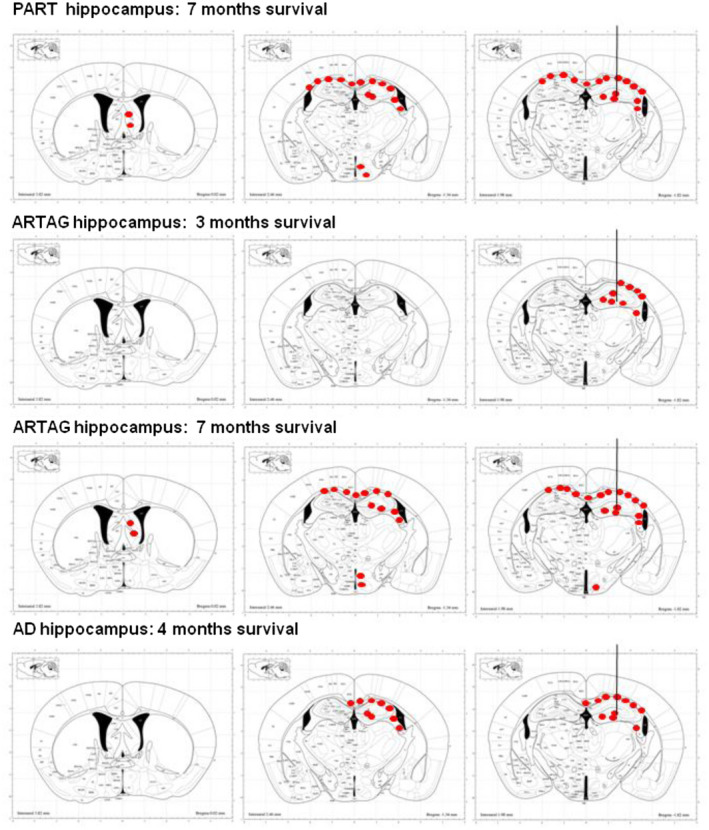

Summary of the localization and distribution of tau deposits in injected mice

Figure 6 summarizes the localization and distribution of tau‐immunoreactive deposits in mice unilaterally inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART, ARTAG and AD into the hippocampus with variable time of survival. Mice with short survival times (3–4 months) showed deposits in the ipsilateral hippocampus, fimbria and corpus callosum. Long survival times (7 months) in mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART and ARTAG cases showed additional tau deposits in the septal region, periventricular area of the hypothalamus and contralateral corpus callosum.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of phospho‐tau‐immunoreactive deposits (red dots), as revealed with the AT8 antibody, following unilateral inoculation of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from ARTAG and AD to WT into the hippocampus of mice aged 7 months and killed 3 or 4 months later, respectively; from PART and ARTAG in mice aged 3 months, and ARTAG in mice aged 7 months and killed 7 months later. Mice killed 3–4 months after inoculation show tau deposits restricted to the ipsilateral hemisphere, whereas mice killed at longer times postinoculation reveal deposits in distal projections such as the periventricular hypothalamus and septal nuclei, and the contralareral corpus callosum. The site of injection is indicated by a vertical line ending in the lateral hippocampus. Maps obtained from the atlas of Paxinos and Franklin 63.

Figure 7 summarizes the localization and distribution of tau‐immunoreactive deposits in mice unilaterally inoculated into the corpus callosum with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from AD, ARTAG and GGT cases and killed 3–4 months later; and in mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART, ARTAG and GGT cases, killed 6–7 months later. Tau deposits in the corpus callosum in mice surviving for short periods were restricted to the ipsilateral corpus callosum, whereas longer survival times were manifested by additional tau‐immunoreactive deposits in the contralateral corpus callosum. Moreover, PART and ARTAG homogenates appeared to have more capacity for seeding than GGT homogenates at long survival times.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of phospho‐tau‐immunoreactive deposits (red dots), as revealed with the AT8 antibody, following unilateral inoculation of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions in the corpus callosum from AD, ARTAG and GGT aged 7 months and killed 3–4 months later; and PART, ARTAG and GGT homogenates in mice aged 7 months and killed 6–7 months later. Tau deposits in the corpus callosum are restricted to the ipsilateral hemisphere in animals surviving 3–4 months; however, mice killed 6–7 months after inoculation show, in addition, tau deposits in the contralateral corpus callosum. In contrast, no tau deposits are seen following inoculation of sarkosyl‐soluble fractions of AD (ADs) and ARTAG (ARTAGs) at 4 and 7 months after injection, and in mice injected with vehicle alone. The site of injection is indicated by a vertical line ending in the lateral hippocampus. Maps obtained from the atlas of Paxinos and Franklin 63.

Finally, schemes of the brain of mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐soluble fractions of AD and ARTAG (ADs and ARTAGs, respectively), and of one mouse inoculated with vehicle are represented in the same figure. No tau deposits were seen following inoculation of sarkosyl‐soluble fractions or vehicle.

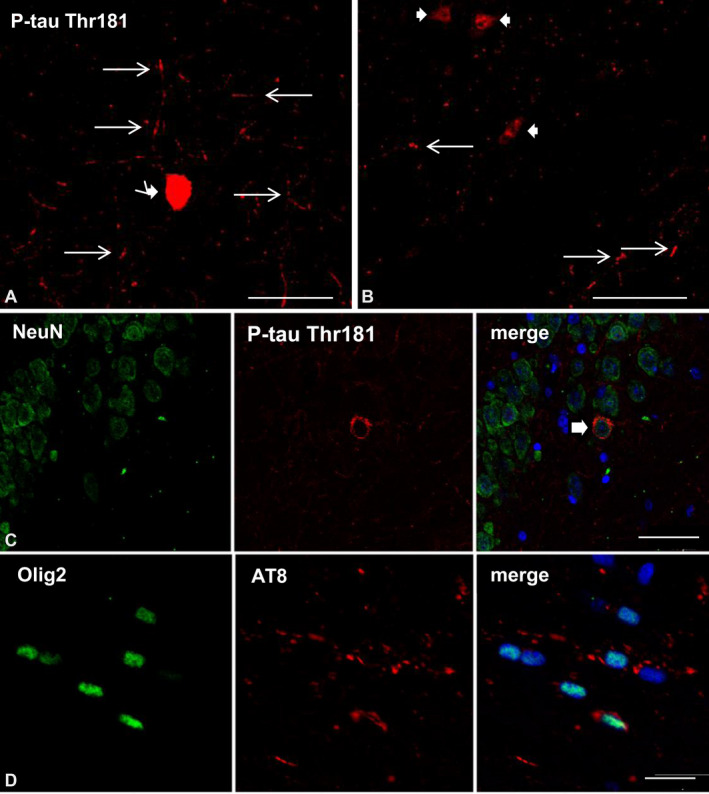

Single and double‐labeling immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy: seeding and spreading of tau is associated with activation of tau‐kinases in tau‐positive cells

Labeled neurons and fine cellular processes were best visualized in serial reconstructions of sections stained with immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy (Figure 8A); thin tau‐immunoreactive processes and weakly stained neurons were seen not only in the ipsilateral hippocampus but in the septal nuclei as well (Figure 8B). The type of tau‐immunolabeled cells following inoculation of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from tauopathies were recognized by double‐labeling with anti‐tau antibodies and specific neuronal (NeuN), astroglial (GFAP) and oligodendroglial (Olig2) antibodies. Double‐labeling immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy identified NeuN and tauThr181 co‐localization in neurons following inoculation of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART and ARTAG cases (Figure 8C). Double‐labeling immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy identified oligodendroglial cells, as revealed with the Olig2 and AT8 antibodies, to be the only population of tau‐containing glial cells in the fimbria and corpus callosum following inoculation of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions of PART, ARTAG and GGT into the hippocampus or into the corpus callosum (Figure 8D–F).

Figure 8.

A, B. WT mice unilaterally inoculated into the hippocampus with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART at 12 months and killed at 19 months (7 months survival) showing one tau‐immunofluorescent CA1 neuron (thick arrow) and fine neuronal cell processes (thin arrows) in the ipsilateral hippocampus (A), and weaker tau‐immunoreactive neurons (thick arrows) and threads (thin arrows) in the septal nucleus (B). C. WT mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART in the hippocampus at the age of 3 months and killed at the age of 10 months (7 months survival) showing tau‐immunoreactive neurons (thick arrow), as revealed by double‐labeling immunofluorescence to NeuN and P‐tauThr181. D–F. WT mice inoculated into the corpus callosum with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from ARTAG (D), GGT (E) and PART (F) at 12 months and killed at 18–19 months (6–7 months survival); double‐labeling immunofluorescence to Olig2 (green) and AT8 (red) shows oligodendrocytes (thin arrow) in the corpus callosum containing hyperphosphorylated tau. Paraffin sections, nuclei stained with DRAQ5™ (E: blue); A, B: bar = 30 μm; C: bar = 40 μm; D: bar = 40 μm; E, bar = 25 μm; F, bar = 30 μm.

Tau deposits were rarely seen in astrocytes in the hippocampus, but not in the corpus callosum. Importantly, in no cases did microglial cells stained with the antibody Iba1 contain phosphorylated tau at any survival time following inoculation (data not shown).

Semiquantitative studies were carried out in the ipsilateral corpus calloum of mice inoculated into the corpus callosum with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART, ARTAG and GGT, and killed at 6–7 months after injection. These studies revealed that about 50% of the total number of oligodendrocytes contained phospho‐tau deposits in mice inoculated with PART and ARTAG homogenates, whereas the percentage was lower (about 30%) in mice inoculated with GGT homogenates.

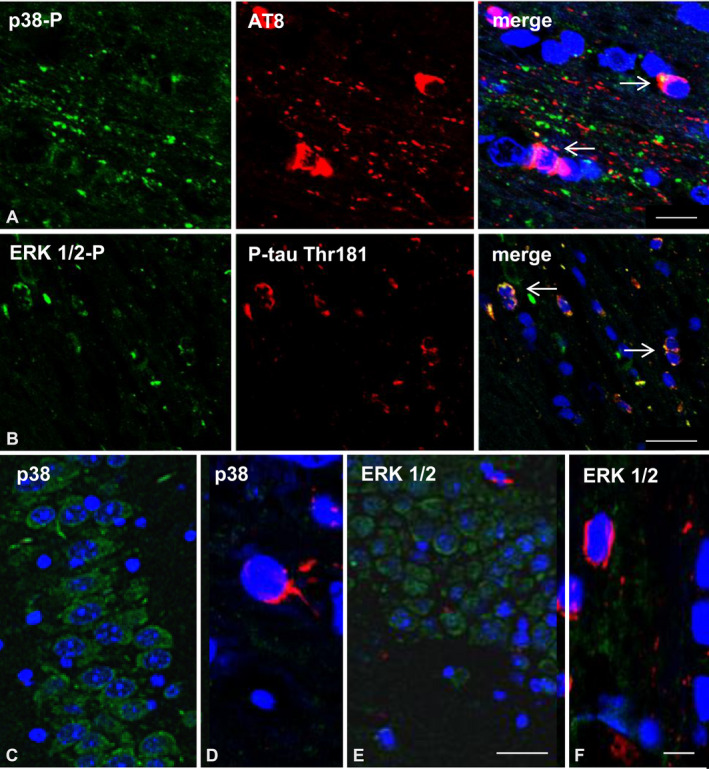

Double‐labeling immunofluorescence with anti‐phospho‐tau antibodies (AT8) and antibodies directed to phosphorylated p38 kinase (p38‐P:Thr180‐Tyr182) examined with confocal microscopy identified co‐localization of tau and active p38 (p38‐P) in about 20%–30% of tau‐positive glial cells of the corpus callosum in mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from ARTAG (Figure 9A), and PART and GGT cases. Similarly, double‐labeling immunofluorescence with anti‐P‐tauThr181 and phospho‐ERK 1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) showed co‐localization of tau and active ERK 1/2‐P in 25%–35% of the total glial cells in the corpus callosum of mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from GGT (Figure 9B), and PART and ARTAG cases. Since oligodendroglial cells were the only cells stained with anti‐phospho‐tau antibodies in the corpus callosum in mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from different tauopathies, it was inferred that active kinases expressed in phospho‐tau‐containing cells were localized in oligodendrocytes. In addition, to oligodendrocytes, phospho‐tau‐immunoreactive dots and threads in the corpus callosum were heavily stained with anti‐phosphorylated p38 kinase and anti‐phospho‐ERK 1/2 antibodies (Figure 9A,B).

Figure 9.

A. Double‐labeling immunofluorescence to phosphorylated p38 (p38‐P: Thr180‐182) (green) and AT8 (red) in the corpus callosum of WT mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from ARTAG at the age of 12 months and killed at the age of 19 months (7 months survival). Active p38 kinase (p38‐P) co‐localizes with tau deposits (arrows) in oligodendrocytes and, more markedly, in tau‐positive dots and threads in the corpus callosum. B. Double‐labeling immunofluorescence to ERK 1/2‐P (Thr202/Tyr204) (green) and P‐tau Thr181 (red) in the hippocampus and neighboring regions of WT mice inoculated in the corpus callosum with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from GGT at the age of 12 months and killed at the age of 19 months (7 months survival). Active ERK 1/2 co‐localizes with tau deposits (arrows) in oligodendrocytes and in tau‐positive dots and threads in the corpus callosum. C, D. Double‐labeling immunofluorescence to p38 (green) and AT8 (red) showing immunolabeling of all neurons in the hippocampus (C) and lack of p38 in one glial cell containing phospho‐tau localized in the vicinity of the corpus callosum (D). E, F. Double‐labeling immunofluorescence to ERK1/2 (green) and P‐tau Thr181 (red) showing immunolabeling of all neurons in the hippocampus without phospho‐tau deposits (E), and absence of ERK1/2 in few tau‐positive glial cells in the vicinity of the corpus callosum (F) of WT mice inoculated with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from ARTAG at the age of 12 months and killed at the age of 19 months. P38 and ERK1/2 heavily stained fibers in the fimbria and corpus callosum (not shown) thus impeding any visualization of p38 and ERK1/2 glial immunoreactivity in these tracts. Paraffin sections, nuclei stained with DRAQ5™ (blue), A: bar = 15 μm; B: bar = 20 μm; C and E, bar = 25 μm D and F, bar = 8 μm.

In contrast, non‐phosphorylated p38 was expressed in all neurons in the hippocampus in mice inoculated into the corpus callosum with vehicle or with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART, ARTAG and GGT cases. Non‐phosphorylated p38 also stained fibers in the corpus callosum but visualization of p38‐imunostained oligodendrocytes in the corpus callosum was hindered by the immunostaining of positive fibers. However, a few glial cells outside but in the vicinity of nerve fiber tracts, such as the corpus callosum and fimbria, which contained hyperphosphorylated tau were not stained with anti‐p38 antibodies at the concentration used in this study (Figure 9C,D). Similarly, non‐phosphorylated ERK 1/2 was expressed in the totality of neurons in the hippocampus and in the fibers of the corpus callosum in mice. Again, visualization of the cytoplasm of oligodendrocytes was prevented by the staining of the fibers in the corpus callosum and fimbria. The pattern of non‐phosphorylated ERK 1/2 in mice inoculated with vehicle was similar to that seen in mice inoculated with human brain homogenates. Again, a few glial cells, outside but in the vicinity of the corpus callosum and fimbria, which contained hyperphosphorylated tau were not stained with anti‐p38 antibodies at the concentration used in this study (Figure 9E,F).

Comparison of tau deposits in human tauopathies and inoculated WT mice

A comparison of the characteristics of cells and tau deposits in neurons and glial cells in human tauopathies and inoculated mice with sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions of the corresponding diseases is shown in Table 3. Main differential aspects are the following: (i) tau deposits in inoculated mice had the characteristics of pre‐tangles, whereas tau inclusions in AD, PART and GGT were mostly tangles; (ii) tau deposits in inoculated mice were composed of 4Rtau and 3Rtau, whereas tau deposits in GGT and ARTAG were composed of 4Rtau; (iii) tau deposits in inoculated mice occurred in neurons and oligodendrocytes, in addition to threads, independently of the tauopathy, whereas tau deposits in AD and PART were only neuronal, and those in pure ARTAG were only found in astrocytes; and (iv) TSAs, GOIs and GAIs, which are characteristic of ARTAG and GGT, respectively, were not observed in the corresponding inoculated mice.

Discussion

The present observations show successful seeding and spreading of human pathological tau from sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions obtained from AD, PART, ARTAG and GGT cases inoculated unilaterally into the hippocampus and the lateral corpus callosum of WT transgenic mice at different ages and surviving for variable periods. These tauopathies were chosen because they are characterized by different types of tau deposits in particular cell types, including neurons or glial cells, or both. Moreover, these tauopathies are characterized by the deposition of 3Rtau+4Rtau or deposition of only 4Rtau. AD and PART are pure neuronal 3Rtau+4Rtau tauopathies; ARTAG is a pure 4Rtau astroglial tauopathy with typical thorn‐shaped astrocytes (TSAs); and GGT a unique 4Rtau neuronal and glial tauopathy with distinctive globular glial inclusions called globular oligodendroglial inclusions (GOIs) and globular astrocytic inclusions (GAIs) 1, 3, 6, 17, 20, 25, 28, 43, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 58.

Tau seeding and spreading to neurons, glial cells and threads show similar characteristics following intracerebral inoculation of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART, ARTAG and GG homogenates in WT mice

Neurons, rarely astrocytes and abundant oligodendrocytes and threads are the main targets following inoculation into the hippocampus independently of the age at the time of inoculation. Spread of abnormal tau occurs from the hippocampus, fimbria and corpus callosum to the septal nucleus and periventricular hypothalamus following unilateral hippocampal inoculation in animals surviving 7 months after the injection. This pattern is similar to that seen following intrahippocampal inoculation of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions of AD in WT mice described in previous studies 36; minor differences related to the more limited extension of tau deposits can be the consequence of the lower doses of the inoculum in our model (1.5 vs. 2.5 µL). Tau spreading in the hippocampus, fimbria and ipsilateral hippocampus was also observed three months after unilateral inoculation of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from AD in the present series.

Oligodendrocytes and threads are the main targets following inoculation into the lateral corpus callosum. Spread of abnormal tau occurs from the ipsilateral to the contralateral hemisphere through the corpus callosum in every condition.

Tau spreading is time dependent, as explored in ARTAG following injection into the hippocampus; tau deposition progresses to distant regions in the ipsilateral hemisphere and to the contralateral hemisphere after 7 months of survival when compared with the term of 3 months. Similarly, tau from ARTAG and GGT homogenates inoculated into the corpus callosum spread up to the middle region of the corpus callosum in animals after 3 or 4 months of survival, but tau deposits extended to considerable distances along the contralateral corpus callosum at survival times of 7 months.

Tau deposits are immunostained with anti‐phosphorylated tau (AT8), and more rarely with antibodies against certain forms of conformational tau (MC‐1). This is in accordance with the characteristics of tau in the corresponding human diseases. However, no truncated tau at aspartic acid 421, as revealed with the antibody tau‐C3 is found in hyperphosphorylated tau deposits in either neurons or glial cells in inoculated mice. Moreover, tau deposits in inoculated mice are not ubiquitinated. This is in contrast with the presence of truncated tau in neurons in PART, and in neurons and glial cells in PART and GGT human cases labeled with the tau‐C3 antibody. Furthermore, tau deposits in inoculated mice are not stained with anti‐ubiquitin antibodies. This is also in contrast with the characteristics of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions of PART and GGT cases used for inoculation, which contain truncated tau at the C‐terminal, as revealed with anti‐P‐tau Ser422 antibodies in western blots. Since co‐expression of truncated and full‐length tau induces severe neurotoxicity 62, lack of truncated tau in murine cells containing hyperphosphorylated tau probably accounts for the lack of neuronal and glial demise in inoculated mice. We do not know the reasons for the absence of tau truncation at these survival times following inoculation in WT mice, and whether truncated tau would appear with longer survival periods. Biochemical characteristics of tau deposits, together with their diffuse or fine granular immunostaining, almost absence of fluorescence with thioflavin and lack of flame‐like shape strongly suggest that tau deposits in inoculated WT mice have the traits of pre‐tangles 27. Unfortunately, the small number of tau‐labeled cells and their presence in restricted brain regions makes it difficult to obtain frozen samples for biochemical studies geared to identifying the tau band pattern of phospho‐tau in the inoculated animals.

Inoculated tau has a half‐life of a few days 36, and tau spreading increases with time. Moreover, as previously shown in ARTAG 25, abnormal cytoplasmic tau deposits, and more precisely between 30% and 50% of oligodendroglia in the ipsilateral corpus callosum of inoculated mice with PART, ARTAG and GGT sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions co‐express active tau‐kinase p‐38 and ERK‐1/2, thus suggesting active phosphorylation of endogenous murine tau 21, 26. Interestingly, expression of non‐phosphoylated p38 and ERK 1/2 occurs in neurons of the hippocampus, and in fiber tracts in the corpus callosum and fimbria in mice either inoculated with vehicle or with human brain homogenates; therefore, it was difficult to visualize p38 and ERK 1/2 in glial cells in the corpus callosum. However, p38 and ERK 1/2 were apparently absent in a few isolated glial cells outside but in the vicinity of the corpus callosum. Since phospho‐p38 and phospho‐ERK1/2 in the corpus callosum are restricted to glial cells containing phospho‐tau, it is feasible that small amounts of p38 and ERK 1/2 are present in oligodendrocytes, even though we have been unable to identify immunoreactivity under the present methodological conditions.

No other phospho‐kinases linked to tau phosphorylation were analyzed in the current study.

Tau seeding and spreading induced by sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions of PART, ARTAG and GGT homogenates in WT mice do not recapitulate corresponding human tauopathies

Disease‐specific neuronal and glial inclusions are seen following inoculation of brain homogenates from AD, only‐tangle dementia (TD), argyrophilic grain disease (AGD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal degeneration (CBD) into the brain of mice expressing the longest human 4Rtau isoform (ALZ17 line) 13, 16. Neurons, astrocyte plaques, oligodendrocytes and threads are labeled with anti‐phospho‐tau antibodies in the brain of transgenic mice bearing the P301S mutation (line PS19) and inoculated with CBD homogenates, but only neurons and threads are immunolabeled following inoculation of AD homogenates 7.

Regarding inoculations in WT mice, previous studies inoculating total homogenates in ALZ17 mice showed a few neuronal, oligodendroglial and thread inclusions regardless of the origin of the inoculums, AD, TD, PSP, AGD and CBD 13. Yet other studies using inocula enriched in paired helical filaments showed tau spreading to neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes following intracerebral CBD‐tau and PSP‐tau in WT mice; astrocytes reminiscent of astrocytic plaques are seen following CBD‐tau inoculation, and doubtful tufted astrocytes following PSP‐tau inoculation 61. Only neurons were cited as targets of seeding and spreading following inoculation of AD homogenates following the same protocol and the same WT model 36, 61. Finally, no neurons, but grains, threads and coiled bodies, were described as containing phosphorylated tau following inoculation of paired helical filaments from AD cases into the brain of WT mice 5.

The present findings reveal that inoculation of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions of PART, ARTAG and GGT into the hippocampus and corpus callosum of WT mice does not recapitulate certain aspects of the corresponding human tauopathies.

Neurons and oligodendrocytes, and more rarely, astrocytes are targets following AD‐, PART‐ and ARTAG‐tau inoculation into the hippocampus. Oligodendrocytes are the only identified targets following inoculation of AD, PART, ARTAG and GGT into the corpus callosum. This is not rare considering that the predominant glial cells in the corpus callosum, accounting for about 75%–80% of total glia, are oligodendrocytes 74.

TSAs, and GOIs and GAIs which are hallmarks of ARTAG and GGT, respectively, are not found in the brain of inoculated mice.

Species‐specific modulation of tau seeding and spreading

Previous studies have shown different patterns of tau seeding, spreading and specific cell deposits following intracerebral inoculation of tau of different origins (recombinant, and native total or enriched tau in sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from AD and other tauopathies). Differences may be explained on the basis of different tau “strains” present in each particular inoculum. This is evident in transgenic mice expressing human full length or human mutant tau inoculated with human homogenates 7, 13, 15, 16, 45, 65. 4Rtau is accumulated in inoculated mice expressing human tau and different patterns of tau deposition are distinguished depending on the human tauopathy.

Greater capacity for tau seeding and spreading occurs with PART and ARTAG homogenates when compared with GGT homogenates in the present study, thereby suggesting possible differences of tau strains in these tauopathies. However, as indicated above, target cells and characteristics of tau deposits do not recapitulate human diseases in our model.

The present observations show that 4Rtau and 3Rtau accumulate in WT mice following inoculation of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART (3Rtau+4Rtau), but 3Rtau also accumulates to a lesser degree following ARTAG (4Rtau) and GGT (4Rtau) inoculation of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions. It is worth stressing that no tau deposits are observed following inoculation of ThT‐negative sarkosyl‐soluble fractions.

The identification of 3Rtau and 4Rtau in mice in the present study is based on the use of antibodies, as no biochemical methods were utilized due to restricted populations of affected cells. Yet the same antibodies are commonly used in the study of 3Rtau and 4Rtau in human tauopathies 24, 27, and 3Rtau immunoreactivity is absent in transgenic mice expressing the human mutant P301S mutation. Therefore, it can be suggested that 3Rtau is a hidden component of ARTAG and GGT human cases and/or that the metabolism of tau in the host (ie, mouse) plays a role in tau seeding and spreading following inoculation of human tau.

Protein tau in human brain is expressed in six isoforms arising from alternative splicing of exons 2 and 3 which encode N‐terminal sequences, and exon 10 which encodes a microtubule binding repeat domain; isoforms with 352 (3R/0N), 381 (3R/1N) and 410 (3R/2N) amino acids are 3Rtau, and isoforms with 383 (4R/0N), 412 (4R/1N) and 441 (4R/2N) amino acids are 4Rtau. All six isoforms are expressed in adult human brain 11, 31, 32, 34, 35, 37, 69. In contrast, 4Rtau isoforms predominate in the brain of adult mice 35, 44, 53, 59, 69. In human and rodent fetal brain, the smallest 3Rtau isoform that lacks sequences from exons 2, 3 and 10 (3R/0N) is predominant 10, 32, 42, 46, 71. In addition to differences in the shift of isoform expression linked to exon 10 from embryonic to adult brain between murine and human brain, murine tau also differs from human tau in a number of ways including the N‐terminal domain (residues 18–28) and three amino acid residues at the C‐terminal domain 33, 44, 53, 66, as well as in the distribution and localization of the different tau isoforms 12, 55, 59.

A shift from fetal to adult tau isoform expression occurs in most species, including mice and humans 39. However, the mechanisms inducing the shift of tau splicing, particularly those involving exon 10, are poorly understood. Exon 10 shows a default splicing pattern of inclusion 73 which depends on several modulators; the individual significance of these remains unknown. Several regulatory elements exist in the introns flanking exon 10, some upstream and others downstream, including inhibitors such as SRp30c, SRp55, SRp75, 9G8, U2AF, PTB and hnRNPG, and activators such as htra2beta1, CELF3 and CELF4 4, 29, 68. Yet we are far from understanding the exact control of exon 10 inclusion later in development in mice and humans, and the silencing of 3Rtau isoforms in adult murine brain. The reason for 3Rtau deposits in WT mice following intracerebral inoculation of human 4Rtau is intriguing; it probably indicates major modifications in tau splicing modulation in the adult mouse brain following human tau seeding.

Therefore, several factors, including tau primary sequence of the protein, strain and environmental factors, may contribute to a species barrier or species‐dependent determinants that would explain, in part, the lack of correspondence between induced tauopathies in mice and the corresponding human tauopathies used for tau seeding and spreading, as posited in the present study. This idea is not new; the concept of “species barrier” is well recognized in prion transmissibility 38, 67.

The importance of glial cells in the process of seeding and spreading in tauopathies

Involvement of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes is a constant element in most tauopathies 22, 23, 24, 47, 48, 50. Recent studies have suggested glial involvement in the process of disease progression in certain tauopathies such as frontotemporal lobe degeneration‐tau 22, 23, 24, 48, 50. Preliminary studies in ARTAG 25 together with the present confirmatory observations demonstrate the capacity for seeding and spreading of ARTAG‐tau in neurons and oligodendrocytes, thereby upholding the role of astrocytes in the pathogenesis of tauopathies 22, 24, 50, 52.

Tau‐immunoreactive inclusions similar to coiled bodies are abundant in the corpus callosum following inoculation of sarkosyl‐insoluble fractions from PART, ARTAG and GGT into the hippocampus, particularly after inoculation into the lateral corpus callosum. Thus, oligodendrocytes are identified as primary targets of seeding and spreading of human tau in WT mice. This observation is relevant as most non‐AD, non‐PART human tauopathies show involvement of oligodendrocytes and threads in the white matter, lending further support to oligodendrocytopathy 23 as a key pathogenic component of human tauopathies.

Conflict of Interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Benjamín Torrejón‐Escribano (Biology Unit, Scientific and Technical Services, University of Barcelona, Hospitalet de Llobregat, Spain) for his help with the confocal microscopy, and Tom Yohannan for editorial assistance.

This study was supported by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Institute of Health Carlos III (co‐funded by European Regional Development Fund, ERDF, a way to build Europe): FIS PI17/00809, IFI15/00035 fellowship to PA‐B and co‐financed by ERDF under the program Interreg Poctefa: RedPrion 148/16; and the IntraCIBERNED 2019 collaborative project. LL was granted by MINECO (FPU15/02705).

References

- 1. Ahmed Z, Bigio EH, Budka H, Dickson DW, Ferrer I, Ghetti B, et al (2013) Globular glial tauopathies (GGT): consensus recommendations. Acta Neuropathol 126:537–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahmed Z, Cooper J, Murray TK, Garn K, McNaughton E, Clarke H, et al (2014) A novel in vivo model of tau propagation with rapid and progressive neurofibrillary tangle pathology: the pattern of spread is determined by connectivity, not proximity. Acta Neuropathol 127:667–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahmed Z, Doherty KM, Silveira‐Moriyama L, Bandopadhyay R, Lashley T, Mamais A, et al (2011) Globular glial tauopathies (GGT) presenting with motor neuron disease or frontotemporal dementia: an emerging group of 4‐repeat tauopathies. Acta Neuropathol 122:415–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andreadis A (2005) Tau gene alternative splicing: expression patterns, regulation and modulation of function in normal brain and neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1739:91–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Audouard E, Houben S, Masaracchia C, Yilmaz Z, Suain V, Authelet M, et al (2016) High‐molecular weight paired helical filaments from Alzheimer brain induces seeding of wild‐type mouse tau into argyrophilic 4R tau pathology in vivo. Am J Pathol 186:2709–2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bigio EH, Lipton AM, Yen SH, Hutton ML, Baker M, Nacharaju P, et al (2001) Frontal lobe dementia with novel tauopathy: sporadic multiple system tauopathy with dementia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 60:328–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boluda S, Iba M, Zhang B, Raible KM, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ (2015) Differential induction and spread of tau pathology in young PS19 tau transgenic mice following intracerebral injections of pathological tau from Alzheimer's disease or corticobasal degeneration brains. Acta Neuropathol 129:221–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K (2006) Staging of Alzheimer disease‐associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol 112:389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Braak H, Braak E (1991) Neuropathological staging of Alzheimer‐related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82:239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brion JP, Smith C, Couck AM, Gallo JM, Anderton BH (1993) Developmental changes in tau phosphorylation: fetal tau is phosphorylated in a manner similar to paired helical filament‐tau characteristic of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem 61:2071–2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brion JP, Tremp G, Octave JN (1999) Transgenic expression of the shortest human tau affects its compartmentalization and its phosphorylation as in the pretangle stage of Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol 154:255–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bullmann T, de Silva R, Holzer M, Mori H, Arendt T (2007) Expression of embryonic tau protein isoforms persist during adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Hippocampus 17:98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clavaguera F, Akatsu H, Fraser G, Crowther RA, Frank S, Hench J, et al (2013) Brain homogenates from human tauopathies induce tau inclusions in mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:9535–9540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clavaguera F, Bolmont T, Crowther RA, Abramowski D, Frank S, Probst A, et al (2009) Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain. Nat Cell Biol 11:909–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clavaguera F, Hench J, Goedert M, Tolnay M (2015) Invited review: prion‐like transmission and spreading of tau pathology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 41:47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clavaguera F, Lavenir I, Falcon B, Frank S, Goedert M, Tolnay M (2013) “Prion‐like” templated misfolding in tauopathies. Brain Pathol 23:342–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crary JF, Trojanowski JQ, Schneider JA, Abisambra JF, Abner EL, Alafuzoff I, et al (2014) Primary age‐related tauopathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta Neuropathol 128:755–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Calignon A, Polydoro M, Suárez‐Calvet M, William C, Adamowicz DH, Kopeikina KJ, et al (2012) Propagation of tau pathology in a model of early Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 73:685–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dujardin S, Lécolle K, Caillierez R, Bégard S, Zommer N, Lachaud C, et al (2014) Neuron‐to‐neuron wild‐type tau protein transfer through a trans‐synaptic mechanism: relevance to sporadic tauopathies. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duyckaerts C, Braak H, Brion JP, Buée L, Del Tredici K, Goedert M, et al (2015) PART is part of Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol 129:749–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferrer I (2004) Stress kinases involved in tau phosphorylation in Alzheimer's disease, tauopathies and APP transgenic mice. Neurotox Res 6:469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ferrer I (2017) Diversity of astroglial responses across human neurodegenerative disorders and brain aging. Brain Pathol 27:645–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ferrer I (2018) Oligodendrogliopathy in neurodegenerative diseases with abnormal protein aggregates: the forgotten partner. Prog Neurogibol 169:24–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ferrer I (2018) Astrogliopathy in tauopathies. Neuroglia 1:126–150. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferrer I, Aguiló García M, López González I, Diaz Lucena D, Roig Villalonga A, Carmona M, et al (2018) Aging‐related tau astrogliopathy (ARTAG): not only tau phosphorylation in astrocytes. Brain Pathol 28:965–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ferrer I, Gomez‐Isla T, Puig B, Freixes M, Ribé E, Dalfó E, Avila J (2005) Current advances on different kinases involved in tau phosphorylation, and implications in Alzheimer's disease and tauopathies. Curr Alzheimer Res 2:3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ferrer I, López‐González I, Carmona M, Arregui L, Dalfó E, Torrejón‐Escribano B, et al (2013) Glial and neuronal tau pathology in tauopathies: characterization of disease‐specific phenotypes and tau pathology progression. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 73:81–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fu YJ, Nishihira Y, Kuroda S, Toyoshima Y, Ishihara T, Shinozaki M, et al (2010) Sporadic four‐repeat tauopathy with frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Parkinsonism, and motor neuron disease: a distinct clinicopathological and biochemical disease entity. Acta Neuropathol 120:21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gao QS, Memmott J, Lafyatis R, Stamm S, Screaton G, Andreadis A (2000) Complex regulation of tau exon 10, whose missplicing causes frontotemporal dementia. J Neurochem 74:490–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goedert M, Spillantini MG (2017) Propagation of tau aggregates. Mol Brain 10:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Cairns NJ, Crowther RA (1992) Tau proteins of Alzheimer paired helical filaments: abnormal phosphorylation of all six brain isoforms. Neuron 8:159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Rutherford D, Crowther RA (1989) Multiple isoforms of human microtubule‐associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 3:519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goedert M, Wischik CM, Crowther RA, Walker JE, Klug A (1988) Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding a core protein of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease: identification as the microtubule‐associated protein tau. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:4051–4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goode BL, Feinstein SC (1994) Identification of a novel microtubule binding and assembly domain in the developmentally regulated inter‐repeat region of tau. J Cell Biol 124:769–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gotz J, Probst A, Spillantini MG, Schafer T, Jakes R, Burki K, Goedert M (1995) Somatodendritic localization and hyperphosphorylation of tau protein in transgenic mice expressing the longest human brain tau isoform. EMBO J 14:1304–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guo JL, Narasimhan S, Changolkar L, He Z, Stieber A, Zhang B, et al (2016) Unique pathological tau conformers from Alzheimer's brains transmit tau pathology in nontransgenic mice. J Exp Med 213:2635–2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gustke N, Trinczek B, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E (1994) Domains of tau protein and interactions with microtubules. Biochemistry 33:9511–9522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hagiwara K, Hara H, Hanada K (2013) Species‐barrier phenomenon in prion transmissibility from a viewpoint of protein science. J Biochem 153:139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hefti MM, Farrell K, Kim S, Bowles KR, Fowkes ME, Raj T, Crary JF (2018) High‐resolution temporal and regional mapping of MAPT expression and splicing in human brain development. PLoS One 13:e0195771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Iba M, Guo JL, McBride JD, Zhang B, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM (2013) Synthetic tau fibrils mediate transmission of neurofibrillary tangles in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's‐like tauopathy. J Neurosci 33:1024–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]