Abstract

Purpose:

To characterize the clinical presentation of limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) associated with glaucoma surgeries.

Methods:

This is a retrospective cross-sectional study of patients with LSCD and glaucoma who presented to the Stein Eye Institute at University of California, Los Angeles between 2009 to 2018. Patients who underwent trabeculectomy and/or aqueous shunt surgery were included. The severity of LSCD was staged using global consensus guidelines and a clinical assessment scoring system, and basal cell density was measured by in vivo confocal microscopy. Anatomic locations of glaucoma and non-glaucoma surgeries, locations of LSCD, and severity of LSCD were compared.

Results:

Fifty-one eyes of 41 patients with LSCD associated with glaucoma surgery were included in this study. LSCD in these patients uniquely featured sectoral replacement of corneal epithelium by conjunctival epithelium, without corneal neovascularization or pannus. The sites of glaucoma surgery strongly correlated with the locations of LSCD (p=0.002). There was a trend toward increased severity of LSCD in eyes with two or more glaucoma surgeries compared to eyes with one glaucoma surgery, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.3). The use of topical glaucoma medications correlated with LSCD severity, while the impact of antimetabolites did not reach statistical significance. The location of glaucoma drainage surgery correlates with the location of LSCD.

Conclusions:

LSCD associated with glaucoma surgery presents with clinical features distinct from LSCD resulting from other etiologies. Further study is required to delineate the full impact of glaucoma surgery on limbal stem cell function and survival.

Keywords: Limbal stem cell deficiency, limbal stem cell, glaucoma surgery, glaucoma drainage device, trabeculectomy

INTRODUCTION

Orderly proliferation of limbal stem cells (LSC) is crucial for maintaining corneal epithelial homeostasis. Limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) is defined as a decrease in the population and/or function of corneal epithelial stem cells with consequent inability to sustain homeostasis of the corneal epithelium.1

Disorders involving the limbus, including aniridia,2,3 Stevens-Johnson syndrome,2,4 mucus membrane pemphigoid,5,6 chemical injury,7,8 contact lens wear,9-11 ocular surface neoplasia,12,13 and drug toxicity,14-16 may result in LSCD. In addition, LSCD can arise from limbus-involving surgeries, such as conjunctival tumor excision, repeated or extensive pterygium surgery, and complex cataract surgeries.2,17,18

The surgical limbus begins with its anterior border at the termination of Bowman’s and Descemet’s membrane, and ends with its posterior border overlying the scleral spur. As such, the limbus forms the anterior wall of the angle and lies in close proximity to the trabecular meshwork.19 Glaucoma drainage surgeries, including trabeculectomy and drainage device implantation, inevitably involve the limbus and can damage both LSCs and their niche architecture. Iatrogenic LSCD after glaucoma surgery was first reported by Schwartz and Holland in 2001 and later by Muthusamy and colleagues in 2018.20,21 Our previous studies showed that iatrogenic LSCD was among the most common etiologies of LSCD and a majority of these patients underwent glaucoma surgery.22,23 However, the clinical presentation of LSCD following glaucoma surgery has not been fully characterized. This study consists of the largest series of patients with LSCD after glaucoma surgery (trabeculectomy and/or drainage device implantation) and provides a comprehensive analysis of the clinical presentation, anatomic location, and severity of LSCD in relation to glaucoma surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a retrospective cross-sectional study of patients who presented to the Stein Eye Institute between 2009 to 2018. Approval by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA Institutional Review Board #10-001601) was obtained prior to initiation of the study. The described research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the work was Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) compliant. Appropriate consent was obtained prior to initiating the study.

The available medical records of patients with a diagnosis of both LSCD and glaucoma were reviewed. Patient demographics, best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) by Snellen chart, slit-lamp microscopy and photography, use of glaucoma medications at the time of diagnosis, and in vivo laser scanning confocal microscopy were extracted from the medical records. Impression cytology results of 16 patients who consented to the test.

Surgical Data

The type, location, and number of trabeculectomies and/or drainage devices, and the use of mitomycin C (MMC) and/or 5-fluorouracil (5FU) were obtained by chart review. Patients were stratified by the number of glaucoma surgeries into 2 groups: those who had a single glaucoma surgery (Group 1); and those who had ≥2 glaucoma surgeries (Group 2). The limbal location of each glaucoma surgery was recorded. A single surgery could involve more than 1 quadrant. The limbal locations of other surgeries involving the limbus, such as limbal/conjunctival tumor excision, pterygium excision with or without conjunctival autograft, Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK)/Descemet's stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK), phacoemulsification cataract extraction and intraocular lens (CE/IOL), and 20-gauge pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) were similarly recorded.

Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency Diagnosis and Staging

Patients with LSCD were identified on clinical exam. All patients underwent confirmatory testing by in vivo confocal microscopy using the Heidelberg Retina Tomograph III Rostock Corneal Module Confocal Microscope (Heidelberg Engineering GmBH, Dossenheim, Germany). Sixteen patients consented to impression cytology for further evaluation.

The clinical exam and slit lamp photos for each patient were reviewed to determine the location and severity of LSCD. Patients were characterized by two methods: the global consensus on clinical staging of LSCD (Supplementary Figure 1)1 and a previously published clinical scoring system (Supplementary Figure 2).24

Measurement of Central Corneal Basal Cell Density

The measurement of central corneal basal epithelial cell density (BCD) by laser scanning confocal microscopy followed a previously reported protocol.22 Briefly, Z-scan images were taken by the Heidelberg Retina Tomograph III Rostock Corneal Module Confocal Microscope (Heidelberg Engineering GmBH, Dossenheim, Germany). A minimum of 3 volume scans of the central cornea were collected. Volume scans with minimal motion artifact were analyzed. The 3 image frames of central cornea basal cell layer that best showed cellular morphology were selected. A defined area containing ≥50 cells was selected for cell count using the software provided by the manufacturer, avoiding areas of compression artifact if present. Two independent, masked observers measured central corneal BCD in all 3 images. The average of the counts was used for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics (mean, standard deviation, and frequency distribution) were generated using the demographic and clinical information. The Generalized Estimating Equation method was used to calculate the concordance between locations of LSCD, glaucoma surgeries, and other surgeries by each quadrant, while accounting for clustering of multiple quadrants within a subject. P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. The stage of LSCD severity across groups was compared with Fisher’s exact test and Spearman correlation analysis. Multivariate regression analysis was performed to determine if there were any significant risk factors for LSCD severity. Linear regression analysis was used to compare BCD between Groups 1 and 2 while adjusting for LSCD disease severity.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

Among 43 patients who received a dual diagnosis of glaucoma and LSCD, 51 eyes of 41 patients with prior limbus-involving glaucoma drainage surgery were identified and included in the study. Two patients underwent laser procedures and were excluded from this study. There were 22 males and 19 females, aged 25-90 years with a median age of 79 years (Table). The age between Group 1 and 2 was similar (p=0.8, Table). Two patients who received only laser treatment for glaucoma were excluded. Seven eyes had trabeculectomy, 7 eyes had drainage device implantation, and 37 eyes had both types of surgery. Thirty-six eyes (71%) were diagnosed with primary open or closed angle glaucoma, 14 eyes (27%) with secondary glaucoma, and 1 eye (2%) with congenital glaucoma.

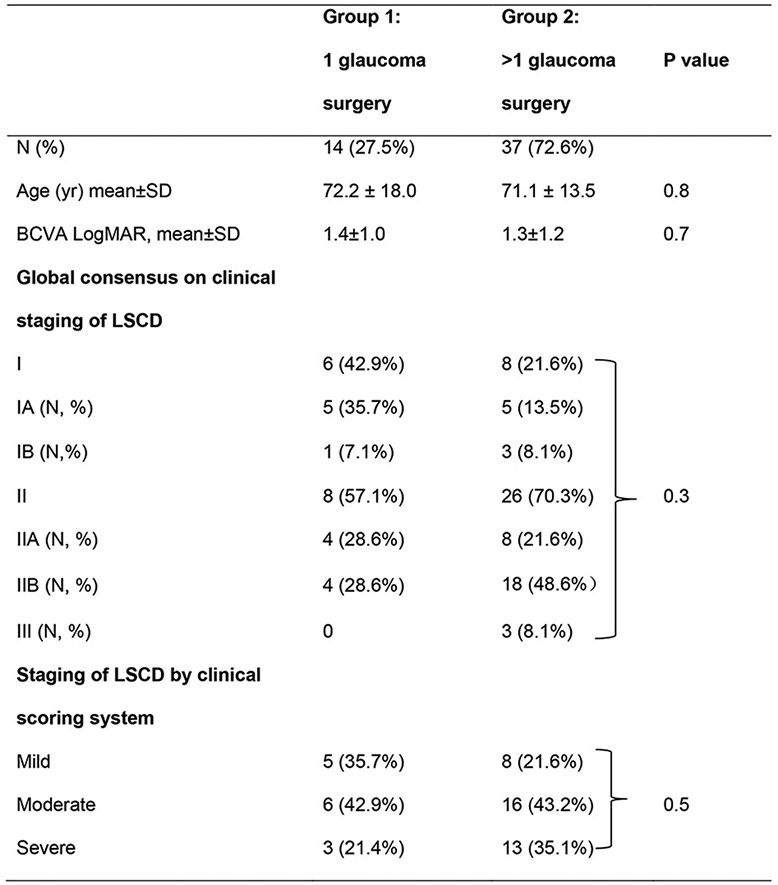

Table.

Demographics and clinical staging of limbal stem cell deficiency after glaucoma surgery

|

Abbreviations: yr, year; LSCD, limbal stem cell deficiency; N, number of eyes.

Clinical Features of Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency Associated with Glaucoma Surgeries

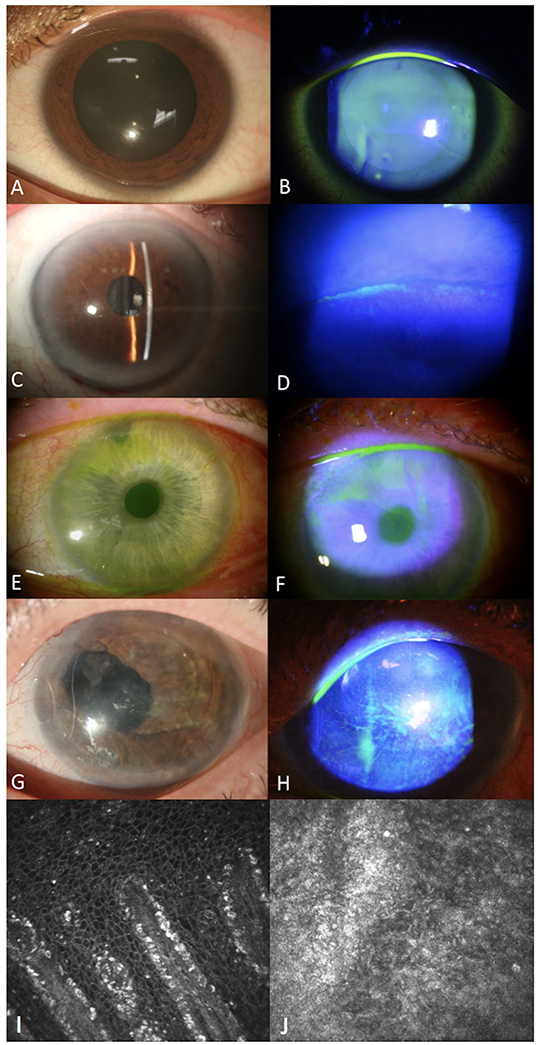

The degree of LSCD for all eyes was categorized as Stage I - III using the global consensus on clinical staging of LSCD1 and as mild/moderate/severe using a previously described clinical scoring system (Table).24 Representative slit lamp photos for the different stages of LSCD after glaucoma surgery are shown in Figure 1. Except for the normal control (Figure 1. A, B), all eyes depicted had undergone trabeculectomy in the superior quadrant. Adjacent to the conjunctival bleb, the eye in stage I (Figure 1. C, D) shows pale gray corneal epithelium from 11 to 1 o’clock under bright light and mild whorl-like pattern fluorescein staining under cobalt blue light. The eye in stage II (Figure 1. E, F) shows a wedge-shaped area in the superior quadrant of grayish opaque epithelium with typical whorled fluorescein staining and pooling that extends into the visual axis. The eye in stage III (Figure 1. G, H) demonstrates replacement of the entire corneal epithelium with thinned, opaque epithelium, with diffuse whorl-like staining. None of the eyes have developed corneal neovascularization or pannus. Compared to normal (Figure 1. I), in vivo confocal microscopic study of patients with LSCD (Figure 1. J) showed destruction of the limbal architecture, with absence of the palisades of Vogt in the affected limbal region.

Figure 1.

Clinical and confocal features of different stages of limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) after glaucoma surgery. Compared to a normal eye (A,B), the corneal epithelium for stage IA (C, D) shows localized superior limbal involvement with a slight whorl-like pattern and pooling under the adjacent bleb. Stage IIA (E, F) shows a wedge-shaped area of classic epithelial whorling and fluorescein pooling extending from the superior limbus to within the central 5 mm of cornea. Stage III (G, H) entails thinning and disruption of the entire corneal epithelium without superficial neovascularization. In vivo confocal microscopy of a normal limbus (I, 400 x 400 um) and one with LSCD (J, 400 x 400 um) shows destruction of normal limbal architecture, loss of corneal epithelial cells, and presence of hyper-reflective conjunctival epithelial cells.

A slightly stronger correlation between the severity of LSCD and a worse visual acuity was found using the clinical assessment scoring system (Spearman coefficient=0.26, p=0.07) than the global consensus staging system (Spearman coefficient=0.15, p=0.28, Supplemental Figure 3).

Correlation of Surgical Site with Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency

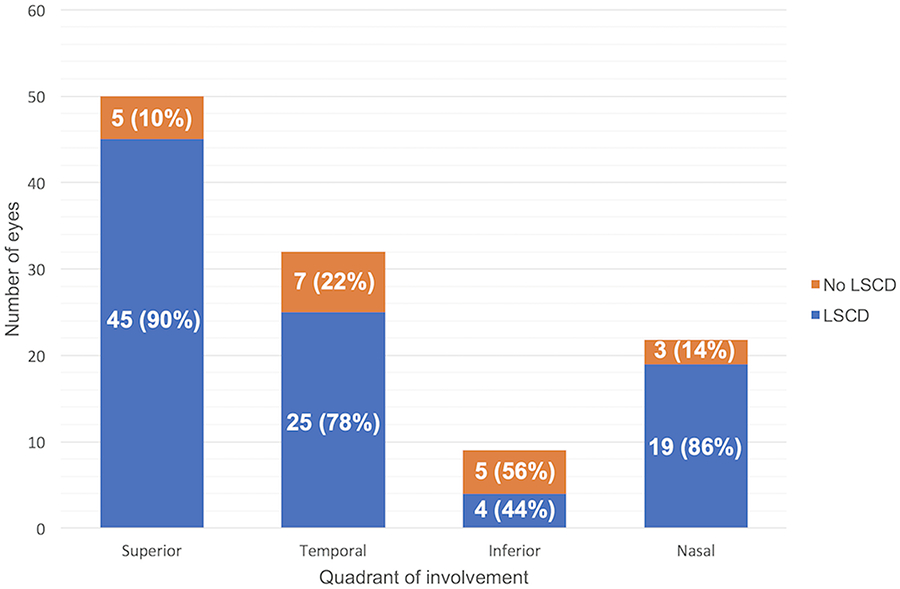

The superior limbus was the most frequently affected region, followed by the temporal and nasal limbus (Figure 2). The sites of glaucoma surgery were strongly correlated with the locations of LSCD (p=0.002). Forty-three eyes had non-glaucoma surgeries that involved the limbus, including DMEK (7 eyes), DSEK (9 eyes), CE/IOL (40 eyes). The locations of these surgeries did not correlate with the locations of LSCD (p=0.5).

Figure 2.

Correlation of site of glaucoma surgery with the location of limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD). The site of LSCD was the same as the site of glaucoma surgery (blue) compared to no LSCD (orange) in 4 limbal quadrants except for the inferior quadrant, (p=0.002).

Correlation of limbal stem cell deficiency severity with number of glaucoma surgeries

Fourteen eyes were classified as Group 1 and 37 eyes as Group 2. Although Group 2 had more eyes with advanced stages of LSCD (IIb or higher, 21 eyes, 56.8%)compared to Group 1 (4 eyes, 28.6%), the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.3, Table). Using the clinical scoring system that was previously developed, 9 (64.3%) eyes of patients in Group 1 developed moderate or severe LSCD, compared to 29 (78.3%) eyes of patients in Group 2. Again, there was a trend toward more mild disease in Group 1 and more severe disease in Group 2 but the difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.5).

Impact of medication on Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency Severity

The effect of MMC/5-FU application during trabeculectomy on LSCD was reviewed. MMC was applied during trabeculectomy for 38 eyes, consisting a lower proportion of Group 1 (7 eyes, 50.0%) compared to Group 2 (31 eyes, 83.8%) (p=0.03). Twenty-one eyes were treated with a routine concentration of 0.3mg/ml MMC for 1-2 minutes, 5 eyes were treated with a higher concentration of 0.4 or 0.5 mg/ml MMC for 3-5 minutes, and 12 eyes received MMC of unknown concentration or duration. There was no significant difference in MMC treatment, dose, or duration, nor in 5-FU treatment between stages of LSCD severity (p >0.05).

Forty-three of 50 eyes were receiving topical glaucoma medications at the time of data extraction. When stratified by the global consensus staging of LSCD, 64.2% (9/14) of eyes in stage I were on glaucoma medications, compared to 94.1% (32/34) of eyes in stage II, and all (2/2) of eyes in stage III. Under the clinical scoring system, 61.5% (8/13) of eyes with mild LSCD received topical therapy, compared to 95.4% (21/22) eyes with moderate and 93.3% (14/15) eyes with severe LSCD.

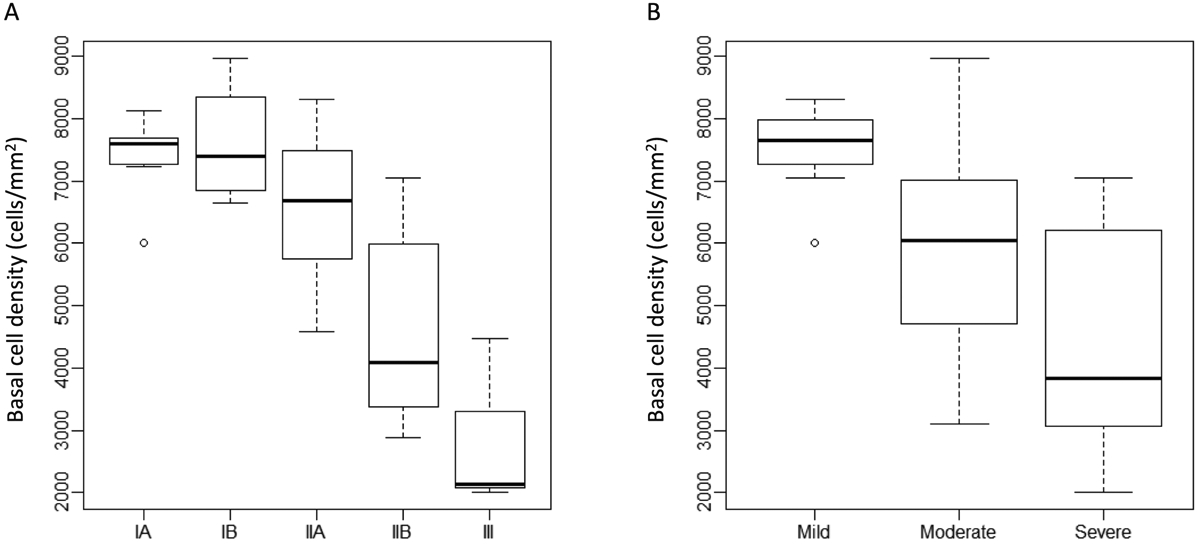

Central Corneal Basal Epithelial Cell Density

There were no differences in the overall mean BCD between the two groups, even when stratified by stage of LSCD by global consensus criteria (p=0.8) or clinical scoring system (p=0.4, Supplemental Table). However, in both groups, BCD decreased as LSCD increased in severity based on clinical staging. Compared to the BCD in stage IA, there was a significant reduction of BCD in stage IIB or moderate stage (p <0.0001) and stage III or severe (p <0.0001), with similar results when LSCD was graded by the clinical scoring system (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Central basal epithelial cell density (BCD) at different limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) stages. Central BCD was inversely proportional to stage of LSCD. Patients with stage IIB or III LSCD (A), or moderate or severe LSCD (B), had significantly lower CBD compared to patients in stage IA or mild stage (all p<0.05), respectively.

A multivariate regression analysis was performed to determine if age, sex, number of glaucoma medication at the time of LSCD diagnosis, number of glaucoma surgeries, or treatment with MMC or 5FU were risk factors for increased LSCD severity. However, none of these variables reached statistical significance (all p>0.05).

DISCUSSION

The current study shows that LSCD caused by previous glaucoma surgery has a unique clinical presentation that differs from LSCD acquired through chemical injury or ocular inflammatory diseases. Sectoral replacement of corneal epithelial cells by conjunctival epithelial cells without significant corneal neovascularization or pannus is the classic feature in LSCD caused by glaucoma surgery. In contrast, diffuse limbal involvement and corneal neovascularization is often present in LSCD after chemical injury and ocular inflammatory diseases.25,26 Although the clinical signs of LSCD caused by glaucoma surgery share some similarity to those associated with contact lens wear, LSCD after glaucoma surgery is often irreversible, whereas a majority of LSCD cases associated with contact lens wear can be treated successfully with cessation of contact lens wear and medications.27,28

The limbal location of glaucoma surgery strongly correlated to the location of LSCD, suggesting that glaucoma surgery was likely the etiology of LSCD in these patients. Glaucoma is a progressive, blinding disease that requires surgical intervention when medical treatment is not sufficient. However, filtering surgeries that involve the limbus can cause inadvertent injury to LSCs and their niche. Use of MMC/5FU may further compromise the reserve of LSCs at the surgical site, and the presence of a bleb can alter the niche environment of LSCs postoperatively. The acute injury during surgery and chronic alternation of the niche can reduce the LSC population and LSC function, leading to LSCD. In contrast, the locations of non-glaucoma surgeries involving the limbus did not correlate with the sites of LSCD. The disparity between these results and those of previous studies, which included data on older surgical techniques such as, intracapsular cataract extraction (CE), are likely due to advances in techniques for CE, keratoplasty etc., which utilize smaller, shorter incisions that minimize limbal trauma and risk for LSCD.

Previous studies have demonstrated that multiple surgeries involving the limbus can induce LSCD.2,20 In the case of glaucoma, patients often require subsequent surgical revisions to achieve adequate control of intraocular pressure. The current study reveals a trend toward more severe stages of LSCD in patients with multiple surgeries, suggesting that repeated glaucoma surgery predisposes to increased severity of LSCD, although a larger study is needed to confirm this observation.

Reduction of central corneal BCD correlates with the severity of LSCD and is a useful supplement in the clinical staging of LSCD.24,29 In this study, the BCD of eyes with LSCD Stages IIb and III by global consensus criteria and moderate/severe by the clinical scoring system was significantly lower compared to that of stage IA or mild stage. Although BCD correlated with LSCD severity, BCD reduction did not correlate with the number of glaucoma surgeries. However, the large variation of BCD among the different stages and limited sample size this study may mask differences across the number of surgeries.

Anti-metabolites such as MMC and 5-fluorouracil (5FU) are routinely used during and after trabeculectomy to inhibit wound healing and promote a functional filtering bleb.30-32 There is growing evidence that use of these drugs is linked to LSCD.14,33 Our data also show a tendency for these drugs to damage LSCs, but the small number of eyes in this study limited the statistical significance of the results. Further study is required to determine the effect of MMC on LSCs. Steps to minimize limbal manipulation and decrease MMC exposure may help reduce disruption of the ocular surface and its complications.

In addition to filtering surgery and anti-metabolite use, additional aspects of glaucoma management may contribute to LSCD. Topical medication use, including pilocarpine and beta blockers, has been linked to limbal stem cell deficiency,34 while the ubiquitous preservative benzalkonium chloride can by itself induce limbal stem cell deficiency in mice.16 In this study, use of topical anti-hypertensive medications was indeed associated with an increased severity of LSCD. Additionally, glaucoma patients are at higher risk for iatrogenic bullous keratopathy due to a myriad of factors; ocular hypertension,35 topical glaucoma medications, laser iridotomy/trabeculoplasty,36 and filtering surgeries, especially drainage device implants,37 can accelerate endothelial cell loss. In turn, bullous keratopathy has been associated with limbal stem cell deficiency.38 These additional complications of glaucoma management need to be considered. Further studies are necessary to delineate the role of chronic topical medication toxicity and endothelial failure in glaucoma-associated iatrogenic LSCD.

Recognizing the risk of ocular surface compromise has potential impact on glaucoma management. Whether limbus-based trabeculectomy, judicious use of anti-metabolites or preservative-free eye medication could reduce the risk of iatrogenic LSCD need further investigation. It is important to recognize these risk factors for developing LSCD in glaucoma patients. Medical therapies that improve the ocular surface should be considered such as,treatments of dry eye disease with preservative-free artificial tears, punctal occlusion, and tarsorrhaphy; treatments to reduce ocular surface inflammation; and minimizing toxicity from topical medications such as avoiding benzalkonium chloride. In eyes with central visual axis involvement of LSCD, treatment with large diameter fluid-filled scleral lens could improve vision but might not change the course of the LSCD. Limbal stem cell replacement therapy would be a more definitive treatment to reverse the pathology of LSCD. However, the efficacy of limbal stem cell treatment is unknown in this population of iatrogenic LSCD.

There are limitations of the current study. Although this study represents the largest series of LSCD related to glaucoma surgery thus far, larger studies are still needed to fully analyze differences between subgroups based on the number of glaucoma drainage surgeries, use of anti-metabolites, and the severity of LSCD. The natural course of LSCD after glaucoma surgery needs to be elucidated.

In summary, LSCD occurring after glaucoma surgery often presents differently from that after chemical injury with only epithelial changes without corneal neovascularization. There is a correlation between the site of glaucoma surgery and the limbal locations of LSCD. Measures to reduce injury to the limbus should be considered to reduce the risk of LSCD.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table. Central basal cell density by clinical stage of limbal stem cell deficiency after glaucoma surgery.

Supplemental Figure 1. Global consensus on clinical staging of limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD). The severity of LSCD is classified into 3 stages. Stage I disease only involves the periphery of the cornea and the degree of involvement is staged into A, B, and C (top panel). Stage II disease involves both periphery and central 5 mm of the cornea (middle panel). Stage III disease involves the entire corneal surface (bottom panel).

Image credit: Deng et al.1

Supplemental Figure 2. Clinical scoring system for staging limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD). The severity of LSCD is classified into 3 stages: mild, moderate and severe. Points are assigned regarding clock hours of limbal involvement, corneal surface area, and involvement of the visual axis. Slit-lamp photos of an example eye (right column) show characterization with 6 total points, qualifying as moderate stage LSCD.

Image credit, adapted from: Aravena C et al.22

Supplemental Figure 3. Distribution of visual acuity in relation to the severity of limbal stem cell deficiency. A) The spearman correlation coefficient between visual acuity and the clinical assessment score was 0.255 (p=0.07). B) The spearman correlation coefficient between visual acuity and global consensus score was 0.154 (p=0.28).

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: This work is supported in part by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY) to the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of California, Los Angeles. SXD received grant support from the National Eye Institute (2R01 EY021797 and R01 EY028557) and California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (TR2-01768 and CLIN1-08686) to study limbal stem cells; SXD is a consultant for W. L. Gore & Associates (Newark, NJ), Dompe US (San Bruno, CA) and Kowa Research Institute, Inc. (Morrisville, NC). For the remaining authors, none were declared.

References

- 1.Deng SX, Borderie V, Chan CC, et al. Global Consensus on Definition, Classification, Diagnosis, and Staging of Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Cornea. 2019;38:364–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puangsricharern V, Tseng SC. Cytologic evidence of corneal diseases with limbal stem cell deficiency. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1476–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishida K, Kinoshita S, Ohashi Y, et al. Ocular surface abnormalities in aniridia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:368–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma KN, Thanos A, Chodosh J, et al. A Novel Technique for Amniotic Membrane Transplantation in Patients with Acute Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Ocul Surf. 2016;14:31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long Q, Zuo Y-G, Yang X, et al. Clinical features and in vivo confocal microscopy assessment in 12 patients with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. International journal of ophthalmology. 2016;9:730–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazala JR. Ocular pemphigus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1959;48:355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballen PH. TREATMENT OF CHEMICAL BURNS OF THE EYE. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1964;43:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pellegrini G, Traverso CE, Franzi AT, et al. Long-term restoration of damaged corneal surfaces with autologous cultivated corneal epithelium. Lancet. 1997;349:990–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Achong ODRA, Caroline FAAOP. Limbal stem cell deficiency in a contact lens-related case. Clinical Eye and Vision Care. 1999;11:191–197. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloomfield SE, Jakobiec FA, Theodore FH. Contact Lens Induced Keratopathy: A Severe Complication Extending the Spectrum of Keratoconjunctivitis in Contact Lens Wearers. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Aversa G, Luchs JL, Fox MJ, et al. Advancing wave-like epitheliopathy. Clinical features and treatment. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:962–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyall DA, Srinivasan S, Roberts F. Limbal stem cell failure secondary to advanced conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma: a clinicopathological case report. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prabhasawat P, Tseng SC. Impression cytology study of epithelial phenotype of ocular surface reconstructed by preserved human amniotic membrane. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:1360–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pires RT, Chokshi A, Tseng SC. Amniotic membrane transplantation or conjunctival limbal autograft for limbal stem cell deficiency induced by 5-fluorouracil in glaucoma surgeries. Cornea. 2000;19:284–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lichtinger A, Pe'er J, Frucht-Pery J, et al. Limbal stem cell deficiency after topical mitomycin C therapy for primary acquired melanosis with atypia. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Z, He H, Zhou T, et al. A mouse model of limbal stem cell deficiency induced by topical medication with the preservative benzalkonium chloride. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2013;54:6314–6325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen JJ, Tseng SC. Abnormal corneal epithelial wound healing in partial-thickness removal of limbal epithelium. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 1991;32:2219–2233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz GS, Holland EJ. Iatrogenic limbal stem cell deficiency. Cornea. 1998;17:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Buskirk EM. The anatomy of the limbus. Eye (Lond). 1989;3 ( Pt 2):101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz GS, Holland EJ. Iatrogenic limbal stem cell deficiency: when glaucoma management contributes to corneal disease. J Glaucoma. 2001;10:443–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muthusamy K, Tuft SJ. Iatrogenic limbal stem cell deficiency following drainage surgery for glaucoma. Can J Ophthalmol. 2018;53:574–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng SX, Sejpal KD, Tang Q, et al. Characterization of limbal stem cell deficiency by in vivo laser scanning confocal microscopy: a microstructural approach. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:440–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan EH, Chen L, Yu F, et al. Epithelial Thinning in Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160:669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aravena C, Bozkurt K, Chuephanich P, et al. Classification of Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency Using Clinical and Confocal Grading. Cornea. 2019;38:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sangwan V, Jain S, Vemuganti G, et al. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis with limbal stem cell deficiency. cornea. 2011;30:491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sati A, Basu S, Sangwan VS, et al. Correlation between the histological features of corneal surface pannus following ocular surface burns and the final outcome of cultivated limbal epithelial transplantation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:477–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim BY, Riaz KM, Bakhtiari P, et al. Medically reversible limbal stem cell disease: clinical features and management strategies. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:2053–2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossen J, Amram A, Milani B, et al. Contact Lens-induced Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Ocul Surf. 2016;14:419–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan EH, Chen L, Rao JY, et al. Limbal Basal Cell Density Decreases in Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160:678–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khaw PT, Migdal CS. Current techniques in wound healing modulation in glaucoma surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1996;7:24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katz GJ, Higginbotham EJ, Lichter PR, et al. Mitomycin C versus 5-fluorouracil in high-risk glaucoma filtering surgery. Extended follow-up. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1263–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkins M, Indar A, Wormald R. Intra-operative mitomycin C for glaucoma surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD002897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sauder G, Jonas JB. Limbal stem cell deficiency after subconjunctival mitomycin C injection for trabeculectomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:1129–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holland EJ, Schwartz GS. Iatrogenic limbal stem cell deficiency. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1997;95:95–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gagnon MM, Boisjoly HM, Brunette I, et al. Corneal endothelial cell density in glaucoma. Cornea. 1997;16:314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kozobolis VP, Detorakis ET, Vlachonikolis IG, et al. Endothelial corneal damage after neodymium:YAG laser treatment: pupillary membranectomies, iridotomies, capsulotomies. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1998;29:793–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim MS, Kim KN, Kim CS. Changes in Corneal Endothelial Cell after Ahmed Glaucoma Valve Implantation and Trabeculectomy: 1-Year Follow-up. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2016;30:416–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uchino Y, Goto E, Takano Y, et al. Long-standing bullous keratopathy is associated with peripheral conjunctivalization and limbal deficiency. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1098–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table. Central basal cell density by clinical stage of limbal stem cell deficiency after glaucoma surgery.

Supplemental Figure 1. Global consensus on clinical staging of limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD). The severity of LSCD is classified into 3 stages. Stage I disease only involves the periphery of the cornea and the degree of involvement is staged into A, B, and C (top panel). Stage II disease involves both periphery and central 5 mm of the cornea (middle panel). Stage III disease involves the entire corneal surface (bottom panel).

Image credit: Deng et al.1

Supplemental Figure 2. Clinical scoring system for staging limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD). The severity of LSCD is classified into 3 stages: mild, moderate and severe. Points are assigned regarding clock hours of limbal involvement, corneal surface area, and involvement of the visual axis. Slit-lamp photos of an example eye (right column) show characterization with 6 total points, qualifying as moderate stage LSCD.

Image credit, adapted from: Aravena C et al.22

Supplemental Figure 3. Distribution of visual acuity in relation to the severity of limbal stem cell deficiency. A) The spearman correlation coefficient between visual acuity and the clinical assessment score was 0.255 (p=0.07). B) The spearman correlation coefficient between visual acuity and global consensus score was 0.154 (p=0.28).