Abstract

The parvoviruses are small nonenveloped single stranded DNA viruses that constitute members that range from apathogenic to pathogenic in humans and animals. The infection with a parvovirus results in the generation of antibodies against the viral capsid by the host immune system to eliminate the virus and to prevent re-infection. For members currently either being developed as delivery vectors for gene therapy applications or as oncolytic biologics for tumor therapy, efforts are aimed at combating the detrimental effects of pre-existing or post-treatment antibodies that can eliminate therapeutic benefits. Therefore, understanding antigenic epitopes of parvoviruses can provide crucial information for the development of vaccination applications and engineering novel capsids able to escape antibody recognition. This review aims to capture the information for the binding regions of ∼30 capsid-antibody complex structures of different parvovirus capsids determined to date by cryo-electron microscopy and three-dimensional image reconstruction. The comparison of all complex structures revealed the conservation of antigenic regions among parvoviruses from different genera despite low sequence identity and indicates that the available data can be used across the family for vaccine development and capsid engineering.

Keywords: parvoviruses, viral vectors, neutralizing antibodies, binding epitopes, cryo-EM and 3D image reconstruction

Introduction

The Parvoviridae are small nonenveloped, single stranded DNA packaging viruses, with two subfamilies, the Parvovirinae and Densovirinae, which differ in their ability to infect vertebrates or invertebrates, respectively (30). Only the vertebrate parvoviruses encounter true immunoglobulins (antibodies) during the natural viral life cycle, the focus of this review. The Parvovirinae consist of eight genera: Amdoparvovirus, Aveparvovirus, Bocaparvoviruses, Copiparvovirus, Dependoparvoviruses, Protoparvoviruses, Erythroparvoviruses, and Tetraparvovirus. The genomes of these viruses have a size range of ∼4 to 6 kb, and contain two or three large open reading frames (ORFs), the NS (for nonstructural) or Rep (for replication), NP (for nucleoprotein), and Cap/VP (for capsid viral protein) (85). The proteins encoded by the NS/Rep and NP ORFs have regulatory functions that include genome replication, genome packaging, and gene expression, while the Cap/VP ORF encodes proteins that assemble the viral capsids.

Parvoviruses are defined as having a T = 1 icosahedral symmetry capsid with a diameter of ∼260Å. They are assembled from 60 individual VPs (85). Depending on the genus either two or three overlapping VPs are incorporated into capsids in a ratio of ∼1:10 (VP1:VP2) or 1:1:10 (VP1:VP2:VP3), respectively (115). The VPs vary in size (VP1: 75 to 82 kDa; VP2: 64 to 69 kDa; VP3: 59 to 66 kDa for the parvoviruses with three VPs and VP1: 77 to 116 kDa; VP2: 60 to 74 kDa for the parvoviruses with two VPs) with an overlap at the common C-terminus comprising the major capsid protein, VP2 or VP3. The VP1 contains a unique region, VP1 unique (VP1u), containing a phospholipase A2 (PLA2) enzyme, essential for infection. Parvoviral capsids assemble by forming 2-fold, 3-fold, and 5-fold symmetry interactions using the VP3 common region. The 2-fold axis is characterized by a depression on the capsid surface, the 3-fold axis by protrusions at or surrounding it, and the 5-fold axis by a channel connecting the outside with the capsid interior surrounded by a canyon-like depression (85). In addition, the 2- and 5-fold depressions are separated by a raised region that is termed the 2/5-fold wall. This capsid morphology is conserved among the Parvovirinae despite high amino acid sequence diversity (58,85).

Following an infection with a parvovirus in animals or humans, the adaptive immune system will generate antibodies against viral antigens, mediated by B cells (18,23,24,41) to eliminate the virus from the host and to prevent future re-infections of the same virus by creating memory lymphocytes. As a result, a large percentage of these hosts are seropositive (18,64,103,125). The most common type of antibodies in the blood stream are immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies (38). These immunoglobulins have a molecular weight of ∼150 kDa and are composed of two identical heavy chains and two identical light chains that are linked by a series of disulfide bonds forming a “Y-like” shape (104). Generally, the C-termini of the heavy chains from different IgGs are conserved and termed fragment crystallizable (Fc) region. This region shapes the bottom of the “Y-like” structure and is responsible for the interaction with cell surface receptors and other proteins of the immune system. On the opposite end of the immunoglobulin, two identical domains with high diversity are located, which are each formed by the N-terminal half of the heavy chain and the entire light chain. These regions are termed fragment antigen binding (Fab) and contain the antigen contact determining regions (CDRs), recognizing specific antigens like viruses or other pathogens. In summary, one IgG molecule is composed of one Fc and two Fab regions. Binding of antibodies to viral capsids can be neutralizing, for example, by competition, such as with a receptor molecule, and thereby preventing entry into target cells upon re-infection (51,57). Some parvovirus antibodies also act postentry (52,131). While neutralization is favorable for pathogenic parvoviruses, it is detrimental to viral vectors being developed for gene delivery applications.

To characterize the interaction of parvoviral capsids with antibodies, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) coupled with three-dimensional (3D) image reconstruction has been the method of choice since 1994 (129). Initially, the resolutions of the capsid-antibody complex structures were low to medium with resolutions in a range of 23 to 7 Å (13,51–53,60,81,123,129). Nevertheless, they were sufficient to narrow down the epitope on the viral capsid using pseudo-atomic model building and site-directed mutagenesis. Significantly, the continuous improvement of technology has led to atomic resolution of parvovirus capsid-antibody structures, allowing the identification of the direct interacting residues of the epitope (59,122). This review provides a snapshot of the field 25 years after the first antibody complex structure with canine parvovirus (CPV) (129), was published. Importantly, parvoviruses share commonality in antigenic epitopes consistent with functional utilization of similar but sequence diverse capsid regions.

Cryo-EM for the Antigenic Characterization of Parvoviruses

Cryo-EM and subsequent 3D-image reconstruction has become a very attractive and robust tool for studying the interaction of antibodies and other ligands with macromolecules. In recent years, advancements in the technique have allowed for the analysis of macromolecules at atomic resolution. These advancements include microscope design, imaging hardware (energy filters, direct electron detectors [DEDs], and phase plates), enhanced image processing, and automation, which include DEDs allowing for the collection of movie frames, and frame alignment (27,35,49). To date, over 1,000 cryo-EM structures have been deposited in the protein data bank and electron microscopy data bank combined. In the field of parvovirology, cryo-EM has contributed to the characterization of viral capsids alone or in complex with receptor molecules as well for the analysis of capsid-antibody interactions in an effort to identify the antigenic regions on the viral capsid (13,51–53,59,60,81,84,91,122,123,129). The icosahedral symmetry of the parvovirus capsids further benefits the utilization of cryo-EM, with 60-fold averaging allowing reasonable resolutions to be achieved even with low numbers of extracted particles.

For the parvoviruses, the majority of the antigenic region mapping have used purified viral capsids combined with either purified mouse IgGs or Fabs at ratios where all potential capsid binding sites are saturated. The complexes are vitrified on cryo-EM grids after a short incubation period, and used for micrograph data collection (37). The vitrification process creates a thin ice layer, in an amorphous non-crystalline (vitreous) form, in which the capsid-antibody complexes are embedded in different orientations. For data collection on the sample, a low dose electron beam from a transmission electron microscope is used to produce two-dimensional (2D) images of the complexes, which are captured as movie frames on a detector. The movie frames are aligned, and then single particle images are extracted. The single particle images are processed using various software applications to generate a 3D reconstructed density map of the 2D projected images. Depending on the resolution obtained for the complex structures and the availability of the sequence information for the antibody utilized and 3D structure for the capsid, pseudo-atomic capsid and antibody models can be built and fitted into density maps to identify residues or regions of capsid-antibody interactions. Since the parvoviral capsids are composed of 60 icosahedrally arranged VPs, up to 60 Fabs or IgGs could potentially bind to the capsid surface (34). However, most studies determining capsid-antibody structures are performed utilizing the Fab fraction of IgGs or IgAs to avoid aggregation of the capsids and steric hindrance of the larger whole antibody that might prevent full decoration of the viral capsid. A lower number than 60 Fabs can also be bound to the capsid when the interaction is near or exactly at a symmetry axis. For example, antibodies binding at the center of the 3-fold are limited to 20 averaged binding events. Furthermore, icosahedral averaging effects the quality of the density of antibodies binding in symmetry axes (reduces resolution) because they do not obey the 60-fold symmetry of the viral capsid utilized.

Antigenic interactions of dependoparvoviruses

The Dependoparvovirus genus of the subfamily Parvovirinae comprise the Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) (30). The capsids of the AAVs are composed of VP1, VP2, and VP3 in an approximate molar ratio of 1:1:10 (Fig. 1A). The capsid packages a ∼4.7 kb genome that encodes Rep, Cap, and AAP (Assembly Activating Protein). The rep gene produces four overlapping proteins that vary in size and function in viral genome replication and packaging, whereas the cap gene produces three capsid proteins (VP1, VP2, and VP3) (127). AAP is translated from an alternative reading frame within the cap gene and assists capsid assembly (118). The AAVs require coinfection with a helper virus, such as adenoviruses or herpesviruses, for productive replication (22,25). Currently, 13 primate AAV serotypes (AAV1–13) and numerous additional natural isolates from primates and nonprimates have been described (40,42,76,88,110,111).

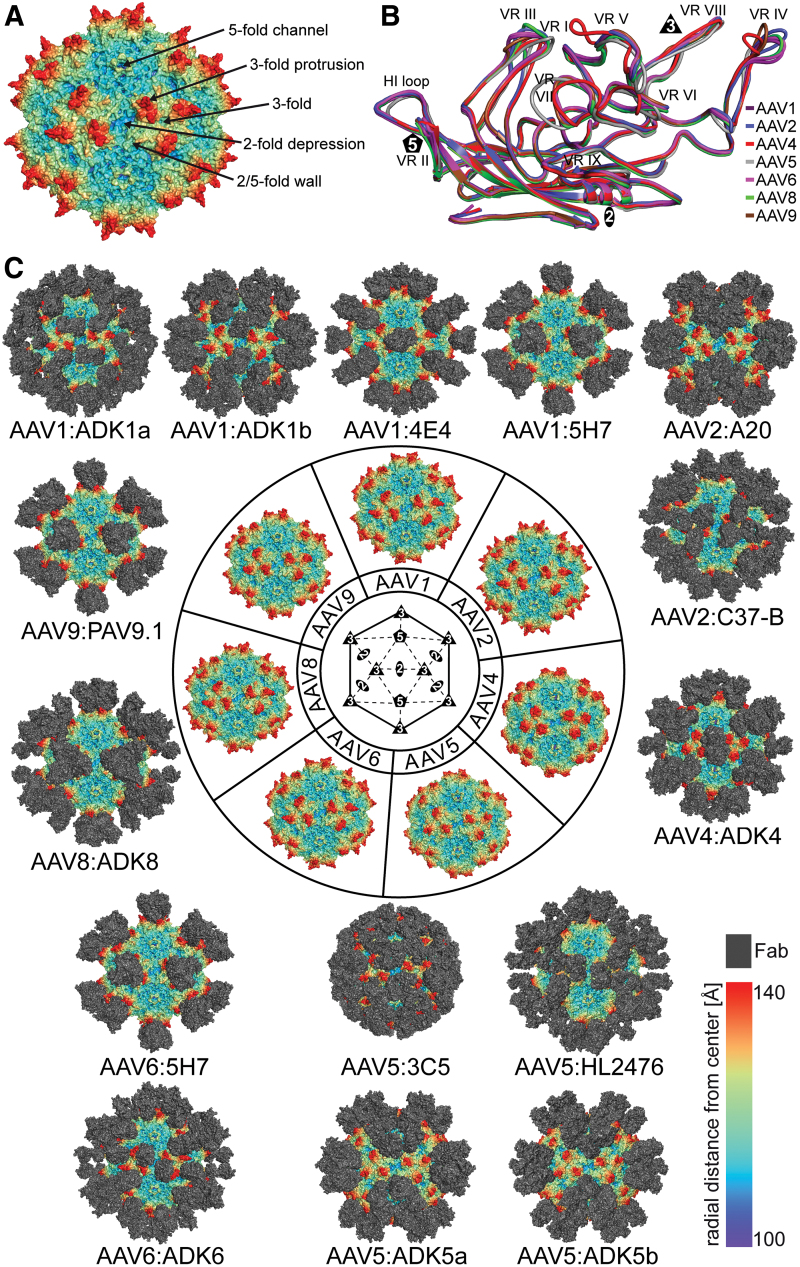

FIG. 1.

Antigenic Interactions of Dependoparvoviruses. (A) Capsid surface representation of AAV2. The approximate locations of the 2-, 3-, and 5-fold axes are indicated along with the 2/5-fold wall and 3-fold protrusions. (B) Structural superposition of VP monomers from different AAV serotypes. The VRs are labeled. (C) Depiction of the cryo-reconstructed density maps of the AAV capsids complexed to the Fab portion of monoclonal antibodies. The serotypes shown are AAV1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 9, located at the center of the figure. Generic or specific Fab models are docked onto the viral capsids at the appropriate locations identified by the cryo-reconstructed maps. These epitopes span the 2-fold, 3-fold, and 5-fold regions together with the 2/5-fold wall. In (A) and (C) the viral capsids are colored radially, such that regions closest to the center are colored purple, and those farthest away are colored red, and the Fabs are colored gray, as indicated by the scale bar (bottom right). These images were generated using PyMol (31). AAV, adeno-associated virus; Fab, fragment antigen binding; VP, viral protein; VR, variable region. Color images are available online.

The VP amino acid sequences of the dependoparvoviruses are diverse with identities ranging from 50% to 99% (42), however, the overall morphology of the AAV capsids are conserved (Fig. 1A) (3,26,54,85). The majority of amino acid differences can be found in VP loops forming the outer surface of the capsids that also display high structural variability (46). The differences at the apexes of these loops are termed variable regions (VRs) defined as two or more amino acids with Cα positions greater than 1Å apart when the VP structures of the different AAV serotypes are superposed (46). For the dependoparvoviruses nine VRs (VR-I-IX) are described (Fig. 1B). These VRs are located throughout the VP chain, but cluster on the capsid surface (85).

Infections with AAVs have not been associated with any disease; however, seroprevalence data indicate that they are widespread in humans, ranging from ∼40% for AAV5 to ∼70% for AAV2 in the general population (18). The AAVs utilize various glycan and protein receptors (5,32,56,65,82,96,100,121,128,132) for cell attachment and entry, and thus differ in tissue tropism (42,102,119). The ability to package a desired transgene expression cassette, for example, for the expression of a therapeutic gene, instead of the wild-type viral genome into capsids, made the AAVs attractive as gene delivery vectors for gene therapy applications (47). These recombinant AAVs (rAAVs) are replication deficient, deliver their packaged vector genome to target cells, and result in long-term transgene expression. These characteristics have made rAAVs one of the most successful tools for restoring function in monogenic disorders. Currently, three AAV-vector-mediated gene therapies have been approved; Glybera, an AAV1 vector for the treatment of lipoprotein lipase deficiency by the European Medicines Agency (113), Luxturna, an AAV2 vector for the treatment of Leber's congenital amaurosis (78), and Zolgensma, an AAV9 vector for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (7) by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Despite the success of AAV vectors in gene delivery, obstacles remain for full realization of the system (86). One of these is the presence of circulating pre-existing neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) against AAV capsids (18,23,24,73,87). These NAbs have been shown to block stages of the viral life cycle, including preventing cell attachment, viral entry and endocytosis, endosomal escape, and trafficking of vector into the nucleus (51). Thus, understanding the antibody epitopes of the AAVs is a major factor in the development of better gene therapy vectors. For this purpose, numerous mouse monoclonal antibodies have been generated against AAV serotypes for study of capsid-antibody interactions (55,59,71,117,124,130). To date, 14 AAV capsid-antibody structures for six AAV serotypes, AAV1, AAV2, AAV5, AAV6, AAV8, and AAV9, have been reported (Fig. 1C).

Four structures of AAV1 capsids complexed to the Fabs of monoclonal antibodies ADK1a, ADK1b, 4E4, and 5H7, were determined to 11Å, 11Å, 12Å, and 23Å, respectively (55,123). The Fab of ADK1a bound to the tip of the icosahedral 3-fold protrusions with contacts at VR-IV, and -V, whereas the ADK1b footprint is localized to the 2/5-fold wall, including residues in VR-I, -III, -VII, and -IX, and extending toward the 5-fold symmetry axis (Table 1) (Fig. 1C). Both, ADK1a and ADK1b were able to neutralize AAV1 infection (123). The mechanism of neutralization by ADK1a was identified as the blockage of the sialic acid (SIA) binding site, the glycan receptor for AAV1 (57). Evidence for this resulted from observation that some residues at the SIA binding region and ADK1a epitope overlap, and non-SIA binding variants escape recognition by ADK1a (57). The mechanism for neutralization by ADK1b was not identified, however, overlap of ADK1b's epitope with that of Mab A20 that neutralizes AAV2 postentry (131), suggests a postentry effect. In addition, ADK1b's footprint overlaps with some residues identified as being important for AAV1 transduction efficiency (19,123). The footprint of Mab 4E4, localized to the side of the 3-fold protrusions involving VR-IV and -V, and extending across to 2-fold axis, whereas 5H7 localized to the center of the 3-fold protrusions involving VR-V and -VIII (Table 1) (Fig. 1C) (51). Both 4E4 and 5H7 are able to hinder cell surface association, however, 4E4 also neutralizes both viral attachment and entry, and may be involved in postentry neutralization (51,55). Overall, the general mechanism of neutralization for both 4E4 and 5H7 is the occlusion of the receptor binding site (55). All of the AAV1 antibodies also cross-react with AAV6 capsids that differs by only three amino acids on the capsid surface, E531K, F584L, and A598V, which are not part of the footprints.

Table 1.

Summary of Reported Antibody Complex Structures for Dependoparvoviruses and Bocaparvoviruses

| Virus | Antibody/Fab | Resolution in Å | Involved VRs | Contact residues | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependoparvovirus | |||||

| AAV1 | 4E4 | 12 | IV, V | 456–459, 492–498 | Gurda et al. (51) |

| 5H7 | 23 | V, VIII | 494, 496–499, 582, 583, 588–595, 597 | Gurda et al. (51) | |

| ADK1a | 11 | IV, V | 448, 450, 453–457, 500 | Tseng et al. (123) | |

| ADK1b | 11 | I, III, VII, IX | 256, 258, 259, 261, 263–266, 272, 385, 386, 547, 709, 710, 716–718, 720, 722 | Tseng et al. (123) | |

| AAV2 | A20 | 8.5 | I, III, VII, IX | 253, 254, 258, 261–264, 384, 385, 548, 556, 658–660, 708, 717 | McCraw et al. (81) |

| C37-B | 11 | V, VIII | 492–498, 585–589 | Gurda et al. (51) | |

| AAV4 | ADK4 | 20 | I, III, IV, V, VIII | 256–261, 375–378, 446, 487–490, 496–498, 513, 583–586 | This publication |

| AAV5 | 3C5 | 16 | I, III, V, VII, HI loop, IX | 246, 254–261, 374, 375, 483, 485–492, 494, 496, 499–501, 530, 532–538, 651, 653, 654, 656, 657, 704–708 | Gurda et al. (51) |

| ADK5a | 11 | I, III, IV, VII, HI-loop, IX | 244, 246, 248–256, 263, 377, 378, 453, 456, 532, 533, 535–543, 546, 653, 654, 656, 697, 698, 704–710 | Tseng et al. (123) | |

| ADK5b | 12 | II, IV, VII, IX | 248, 316–319, 443, 530–535, 540–543, 545, 546, 697, 704, 706, 708–710 | Tseng et al. (123) | |

| HL2476 | 3.1 | IV, V, VIII | 443, 444, 471, 481, 483, 484, 576–578 | Jose et al. (59) | |

| AAV6 | 5H7 | 15 | V, VIII | 494, 496–499, 582, 583, 588–595, 597 | Gurda et al. (51) |

| ADK6 | 13 | I, IV, VIII | 264, 266, 269, 272, 457, 588, 589 | Bennett et al. (13) | |

| AAV8 | ADK8 | 18.7 | IV, V, VIII | 456–460, 493–501, 586–591 | Gurda et al. (52) |

| AAV9 | PAV9.1 | 4.2 | V, VIII | 496–498, 588–593 | Giles et al. (44) |

| Bocaparvovirus | |||||

| HBoV1 | 4C2 | 16 | I, IV, V, VI, VIII | 81–83, 277–282, 307, 309–314, 334–336, 354–355, 392 | Kailasan et al. (60) |

| 9G12 | 8.5 | I, IV, V, VI, VIII | 81–83, 277–282, 307, 309–314, 334–336, 354–355, 392 | Kailasan et al. (60) | |

| 12C1 | 11.9 | I, IV, V, VI, VIII | 81–83, 277–282, 307, 309–314, 334–336, 354–355, 392 | Kailasan et al. (60) | |

| 15C6 | 18.6 | II, IIIB | 141–146, 461–463 | Kailasan et al. (60) | |

| HBoV2 | 15C6 | 17.8 | II, IIIB | 141–146, 457–459 | Kailasan et al. (60) |

| HBoV4 | 15C6 | 9.5 | II, IIIB | 142–147, 460–462 | Kailasan et al. (60) |

AAV, adeno-associated virus; HBoV, human bocavirus; Fab, fragment antigen binding; VR, variable region.

For the AAV2 capsid, the C37-B and A20 Mab footprints were mapped at 11 and 8.5Å resolution, respectively (51,81). While C37-B binding is localized to the icosahedral 3-fold protrusions and involved VR-V (3-fold symmetry related VP) and -VIII, A20 binding is localized to the 2/5-fold wall involving VR-I, -III, -VII, and -IX (Table 1) (Fig. 1C). The epitope of C37-B contains two residues, R585 and R588, reported to be important for the attachment of AAV2 to heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) (131), thus C37-B is predicted to be using receptor-blocking as a neutralization mechanism (51). A20's mechanism of neutralizing viral transduction occurs at a step postentry (131). The epitope was shown not to overlap with the HSPG (81,90) or AAVR binding sites (138). The A20 footprint overlaps with a transduction “dead zone” reported for AAV2, based on mutagenesis of surface residues, describing variants resulting in inability to infect cells and express a packaged transgene (79). Residues within or close to this region are reported to play a role in AAV2 capsid trafficking and genome transcription (10,107). While C37-B does not cross-react with any other AAV serotype, A20 was shown to cross-react with AAV3 (83).

For AAV4, a capsid—complex structure with serotype specific MAb ADK4 (71) is yet to be published. Here, we mention the low, ∼20Å resolution, reconstructed AAV4-ADK4 complex structure from 59 extracted particles with the same methods as previously described (123). In this map, the ADK4 footprint maps to the side of the icosahedral 3-fold protrusions facing the 2/5-fold wall, extending across the 2-fold axis of symmetry, and includes VR-I, III, -IV, -V, and VIII (Table 1) (Fig. 1C). This binding pattern is similar to that of the AAV1–4E4 complex (see above) and the CPV/feline panleukopenia virus (FPV)-FabE, and FPV-FabF complexes (see below). The footprint overlaps residues reported to be involved in SIA binding by AAV4 (492, 503, 523, 581, 583, and 585) suggesting receptor steric hindrance as a potential mechanism of neutralization (57,114).

The four complex structures for AAV5, with MAbs ADK5a, ADK5b, 3C5, and HL2476, were determined to 11Å, 12Å, 16Å, and 3.1Å, respectively (51,59,123). ADK5a bound to the 2/5-fold wall and around the 5-fold channel involving VR-I, III, IV, VII, IX, and the HI loop (Table 1) (Fig. 1C). ADK5b had a similar footprint but is localized closer toward the 5-fold symmetry axis, involving also VR-II but not VR-I and -III (Table 1) (Fig. 1C) (123). ADK5a and ADK5b were both able to neutralize viral transduction (123), but this is not related to receptor attachment since the residues do not overlap (1). The 3C5 antibody had an unusual binding pattern, with the Fabs binding in a tangential orientation (51). At the low resolution of the structure, the CDR is indistinguishable from the constant region of the Fab. Nonetheless, the Fab density is occluding most of the AAV5 capsid including VR-I, -III, V, VII, IX, and the HI loop (Table 1) leaving only the 3-fold region and the 5-fold channel exposed. In contrast to ADK5a and ADK5b neither the Fabs or IgG of the 3C5 antibody inhibited viral transduction (55) consistent with lack of overlap with the receptor attachment site at the 3-fold axes or 5-fold region proposed to be involved in PLA2 function (16,45,137). The current highest resolution parvovirus-antibody structure is AAV5-HL2476 (59). The HL2476 Mab bound to the 3-fold protrusions, interacting with residues within VR-IV, -V, and -VIII (Table 1) (Fig. 1C). The HL2476 antibody neutralized AAV5's infectivity at very low antibody concentrations. A mutational analysis of the AAV5 capsid identified multiple single residue variants of AAV5 that were able to escape from HL2476. These are V481P, V481Y, R483K, A484Q, and S576Q (59). These changes, with the exception of V481Y, led to a reduction of AAV5 transduction efficiency. The HL2476 footprint partially overlaps with the AAV5 SIA binding site (1), and thus it likely prevents the binding of AAV5 capsids to glycosylated receptors (59).

Two capsid–antibody structures, AAV6-ADK6 and AAV6–5H7, are available for AAV6. ADK6 is an AAV6 serotype-specific antibody (117). The AAV6 capsid—ADK6 structure was determined to 16Å resolution (13). The Fab bound to the side of the 3-fold protrusions across the icosahedral 2-fold axis with a footprint including VR-I, -IV, and -VIII (Table 1) (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, residues contacting the Fab CDR model, 264, 266, 269, 272, 457, 588, and 589 did not include K531 identified as determining AAV6's recognition of ADK6 (13). K531 is one of the six amino acids that differ from closely related AAV1 and found in the surface area occluded by ADK6 binding, and as such still part of the footprint. The mechanism for neutralization was proposed as steric hindrance of binding to HSPG. The second MAb, 5H7, is cross-reactive to AAV1, due to high sequence identity between the VP1 of the two viruses, differing by only 6/736 residues (51). The AAV6–5H7 complex structure is at 15Å resolution. As stated above for the AAV1–5H7 complex, this Fab bound to the center of the icosahedral 3-fold axis, involving VR-V and -VIII (Table 1) (Fig. 1C) (51,57). It was assumed that 5H7 is also occluding a receptor binding site (55).

For AAV8, although several mouse MAbs are available (117,124), only the AAV8-ADK8 structure, in which the Fab is bound to the icosahedral 3-fold protrusions involving VR-IV, -V, and -VIII, has been reported (52) (Table 1) (Fig. 1C). Substitution mutagenesis confirmed that amino acids at the apex of VR-VIII, aa585 to aa591, form an important part of the ADK8 footprint (52). This Mab neutralizes AAV8 transduction in vitro and in vivo, by hindering intracellular trafficking by causing perinuclear accumulation of viral capsids (52). While this antibody was generated utilizing AAV8 capsids, it cross-reacts with AAV3, AAV7, and AAVrh.10 capsids (83).

For AAV9, as for AAV8, several MAbs are available (44,117,124). However, the only available structure is that of AAV9-PAV9.1, determined to a resolution of 4.2Å (44). This Fab bound similar to 5H7 to the center of the icosahedral 3-fold axis contacting residues in VR-V, and -VIII (Table 1) (Fig. 1C). The epitope for PAV9.1 was reported as being important for AAV9 liver tropism, with variants in this epitope producing liver de-targeting phenotypes (44). Furthermore, residues 590 and 592 have been characterized as being important for AAV9 transduction (99), indicating that binding of this MAb blocks essential residues that determine transduction efficiency.

Antigenic interactions of bocaparvoviruses

The capsids of the human bocaviruses (HBoVs), belonging to genus Bocaparvovirus, like the AAVs, are composed of VP1, VP2, and VP3 in a ratio of ∼1:1:10 (101) (Fig. 2A). Similar to the AAVs, the majority of amino acid differences between genus members are on the surface of the capsids. Structural superposition of bovine parvovirus (61) and the HBoVs identified 10 VRs containing two or more amino acids with Cα-Cα distances greater than 2Å (84) (Fig. 2B). Unlike AAVs, the HBoV replicate autonomously and are pathogenic. HBoV1 causes respiratory tract infections with symptoms such as acute bronchitis and interstitial pneumonia while HBoV2–4 are associated with gastrointestinal infections (6,9,36). Seroprevalence of the HBoVs is reported to range from 25% in children younger than 1 year of age, to 93% in children older than 3 years of age (64). Furthermore, in a study conducted in China, it was observed that the seroprevalence for HBoV1-4 in children ages 1–14 was 50%, 37%, 29%, and 1% respectively. In persons older than 15 years, seroprevalence for HBoV1-4 was 67%, 49%, 39%, and 1% respectively (50). Thus, antibodies against HBoV1 are the most common but high levels of cross-reactivity among anti-HBoV antibodies are reported (63).

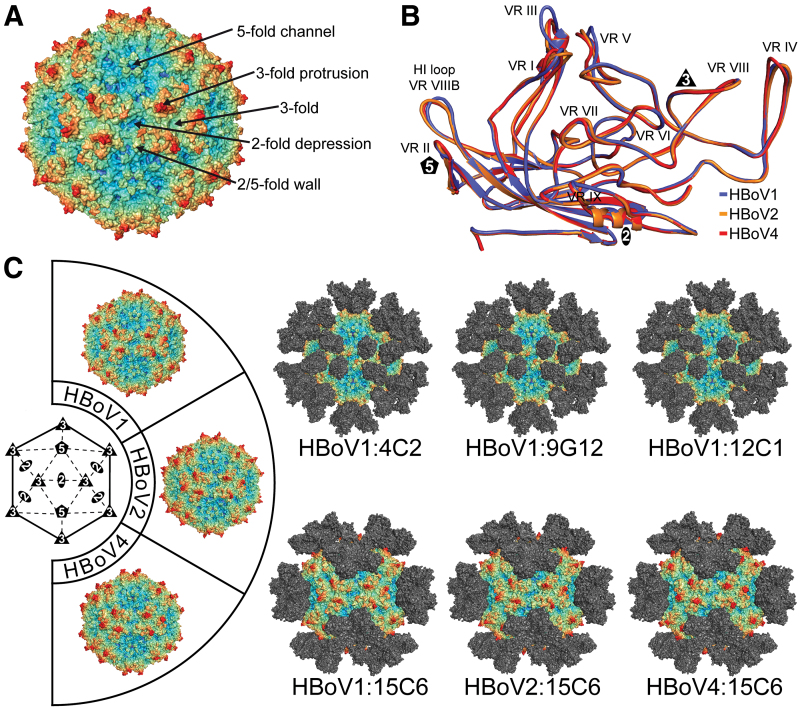

FIG. 2.

Antigenic interactions of Bocaparvoviruses. (A) Capsid surface representation of HBoV1. The approximate locations of the 2-, 3-, and 5-fold axes are indicated along with the 2/5-fold wall and 3-fold protrusions. (B) Structural superimposition of VP monomers from different HBoVs. The VRs are labeled. (C) Depiction of the cryo-reconstructed density maps of the HBoV viral capsids complexed to the Fab portion of monoclonal antibodies. The viral strains shown here are HBoV1, 2, and 4, identified by the capsid wheel located to the left of the figure. Generic Fabs are docked onto the viral capsids at the appropriate locations identified by the cryo-reconstructed maps. These epitopes span the 3-fold and 5-fold axes of symmetry. The viral capsids in (A) and (B) are colored radially, such that regions closest to the center are colored purple, and those farthest away are colored red, with the Fabs colored gray, as indicated by the scale bar (bottom right in Fig. 1). These images were generated using PyMol (31). HBoV, human bocavirus. Color images are available online.

Currently, no treatments or vaccines are available against HBoVs. Furthermore, recombinant HBoVs packaging transgenes are being developed as gene delivery vectors because of their tissue specificity and possess a larger (than AAV) genome packaging capacity (39,134,135). However, like the AAVs, the high seroprevalence of anti-HBoV capsid antibodies in the human population would also reduce the efficiency of HBoV gene delivery vectors. Thus, the antigenic epitopes of HBoVs are being characterized. Four mouse MAbs, 4C2, 9G12, 12C1, and 15C6, have been generated against the HBoV1 capsid (60). Three of these, 4C2, 9G12, and 12C1 are specific for HBoV1 whereas 15C6 cross-reacts with the capsids of HBoV2 and HBoV4 (60). Cryo-EM structures are available for these four MAbs with HBoV1, and for HBoV2 and HBoV4 complexed with 15C6 from 8.0Å to 18.6Å in resolution (60).

While the initial interpretation of the HBoV-Fab footprints relied on pseudo-atomic models for the HBoV capsids, recent atomic resolution structures for these viruses (84) now allow a more accurate description of the epitopes. The cross-reacting 15C6 antibody binds very similarly to the capsids of HBoV1, HBoV2, and HBoV4 around the 5-fold axis of symmetry extending outward toward the 2/5-fold wall making contact and occluding residues 80–95 in VR-I, residues 141–144 in the DE loop, and residues 461–463 in the HI loop (Table 1) (Fig. 2C). The lack of recognition of HBoV3 to 15C6 was originally attributed to residue 146, which is a valine in HBoV3 while a threonine in the other HBoVs (60). The HBoV1 specific antibodies, 9G12, 4C2, and 12C1 all localized to the 3-fold protrusions toward the 2/5-fold wall of the capsid with similar epitopes (60). The footprint residues are located in VR-I (residues 80–85), VR-V (residues 306–315 and 331–336), and VR-VI (residues 354–356) of one VP monomer, and VR-IV (residues 283–288), and VR-VIII (residues 388–395) of the adjacent 3-fold point symmetry related monomer (Table 1) (60). The observation that the cross-reactive antibody binds at the 5-fold symmetry axis of the capsid is consistent with the conservation of sequence and structure among the HBoVs, and parvoviruses in general, at the 5-fold region, while the strain specific recognition of the 3-fold protrusions highlights regions of variability for these viruses (85).

Antigenic interactions of protoparvoviruses

The genus Protoparvovirus comprises many viruses pathogenic to animals and humans, and includes minute virus of mice (MVM), FPV, CPV, and human bufaviruses (BuVs) (30). The capsids of members of this genus are composed of VP1 and VP2 incorporated in a ratio of ∼1:10, with VP3 generated by cleavage of VP2 in genome packaged (full) viruses for some members (2,4,30,85) (Fig. 3A). Ten VRs; VR-0, -1, -2, -3, -4a, -4b, -5, -6, -7, and -8 have been described for the Protoparvoviruses where most of the sequence and structural differences between members are located (85) (Fig. 3B). Importantly, these differences coincide with those described for the dependoparvoviruses and the bocaparvoviruses (Figs. 1B, 2B, and 3B).

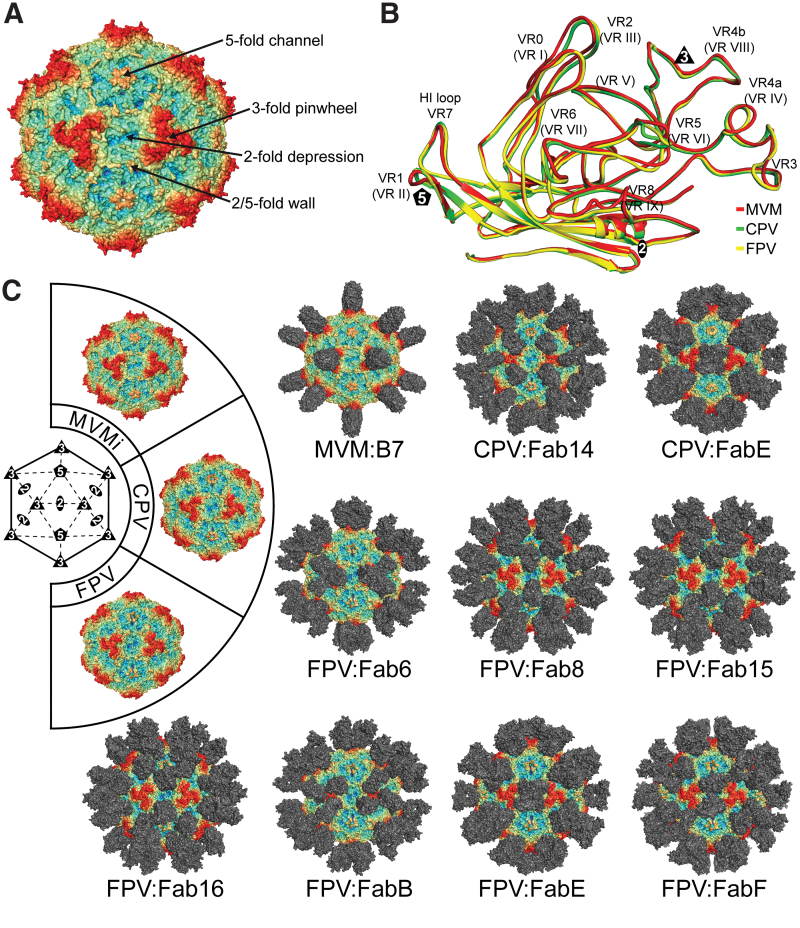

FIG. 3.

Antigenic interactions of Protoparvoviruses. (A) Capsid surface representation of MVM. The approximate locations of the 2-, 3-, and 5-fold axes are indicated along with the 2/5-fold wall and 3-fold protrusions. (B) Structural superimposition of VP monomers from different Protoparvoviruses. The VRs are labeled. (C) Depiction of the cryo-reconstructed density maps of the MVM, CPV, and FPV viral capsids complexed to the Fab portion of monoclonal antibodies. The viral strains are identified in the capsid wheel located to the left of the figure. Generic or specific Fabs are docked onto the viral capsids at the appropriate locations identified by the cryo-reconstructed maps. These epitopes span the 2-fold, 3-fold, and 5-fold axes together with the 2/5-fold wall. The viral capsids in (A, B) are colored radially, such that regions closest to the center are colored purple, and those farthest away are colored red, with the Fabs colored gray, as indicated by the scale bar (bottom right in Fig. 1). These images were generated using PyMol (31). CPV, canine parvovirus; FPV, feline panleukopenia virus; MVM, minute virus of mice immunosuppressive strain. Color images are available online.

The viruses are highly infectious to their respective hosts resulting in high seroprevalences, for example, up to 100% for CPV in dogs (105), 93% for FPV in cats (15), and 72% for the BuVs in humans (125). FPV is the cause of a very contagious and life-threatening gastrointestinal, immune, and nervous system diseases in both wild and domesticated cats, however, available vaccines are able to prevent the detrimental effects of this virus (93,97,112,120). A vaccine is also available for CPV (98). There are currently no vaccines or other forms of treatment for BuVs. In addition to the above viruses, rodent protoparvoviruses are being developed as viral biologics for oncolytic therapies (8,48,80,92). These oncolytic viruses have the ability to target human tumor cells, replicate in these, and kill the cells. However, no disease outcome has been reported in humans from these treatments (20,80). Generally, no pre-existing humoral immunity to the rodent Protoparvoviruses is present in humans, which makes oncolytic virotherapy especially attractive. However, antibodies will develop after the initial dose of the virus (11,72) preventing the readministration with the same virus. Thus, understanding the antibody epitopes of the oncolytic parvoviruses is important toward developing novel vectors that can escape antibody recognition.

The mapping of antigenic epitopes on the protoparvovirus capsids used several Mabs generated against MVM (66), CPV, and FPV (94,129). The first structure determined for a parvovirus-antibody complex was that of CPV bound to the Fab of Mab A3B10 antibody at a resolution of 23Å (129). This Fab bound to the 2/5-fold wall of the CPV capsid involving VR-0, -2, -3, and -6 (Table 2) (Fig. 3C). Both the Fab and the whole IgG were able to neutralize CPV infection. The mechanism of neutralization was not analyzed but blocking of the receptor-binding site or stabilization of the viral capsid, preventing capsid uncoating, were proposed (129). In addition to A3B10, two additional Fab complex structures have been determined for CPV. The structure of CPV complexed with Fab14, a CPV-specific antibody (94), was determined to 12.4Å resolution and it bound at the 3-fold protrusions (53) involving VR-2, -4b, and -5 (Table 2) (Fig. 3C). Due to the close relationship of CPV to FPV, which only differ by a few amino acids in VP2, residue 93, an asparagine in CPV but a lysine in FPV, which was part of the footprint, was proposed as the capsid recognition determinant (53). The third CPV-Fab complex structure was with the cross-reactive FabE that also recognized FPV, mink enteritis virus, and racoon parvovirus (94). The CPV:FabE structure was determined to a resolution of 4.1Å with the Fab footprint localized to the side of the icosahedral 3-fold protrusions across to the 2-fold axis and involved VR-0, -2, -3, and -8 (Table 2) (Fig. 3C) (91). Due to the near atomic resolution of this complex structure, specific residues of CPV (Table 1) could be identified as responsible for the interaction with FabE. Despite the partial overlap of two FabE molecules at the 2-fold symmetry axis, it was shown, by mass spectrometry, that up to 60 FabE molecules can bind to a single CPV capsid (34). The kA for the CPV:FabE complex was determined to be 2.4 × 106 and 8.6 × 106 for CPV:Fab14 (34). While the IgGs of both antibodies neutralize CPV infection, FabE has a higher neutralization efficiency and show the greatest competition with the host transferrin receptor that binds to the 2/5-fold wall, thus preventing viral attachment to cells (89). An alternative neutralization mechanism involving the whole IgGs was proposed to be cross-linking of viral particles (53).

Table 2.

Summary of Reported Antibody Complex Structures for Protoparvoviruses and Erythroparvoviruses

| Virus | Antibody/Fab | Resolution in Å | Involved VRs | Contact residues | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protoparvovirus | |||||

| MVM1 | B7 | 7 | 2, 4b | 225, 228, 229, 425, 426, 432–440 | Kaufmann et al. (66) |

| FPV | Fab6 | 18 | 0, 2, 4b, 5 | 92, 93, 219, 226, 421, 425–428, 433, 435, 437, 438, 440, | Hafenstein et al. (53) |

| Fab-8 | 8.5 | 0, 2, 6, 7, 8 | 81, 85, 87, 296–299, 301, 302, 510–517 | Hafenstein et al. (53) | |

| Fab-15 | 10.5 | 0, 2, 6, 7, 8 | 81, 292–299, 300–302, 305, 306, 515–517, 570, 559 | Hafenstein et al. (53) | |

| Fab-16 | 13 | 0, 2, 6, 7, 8 | 75, 292, 293, 295–299, 300–303, 305, 386, 387, 389–391, 516, 517, 520, 570 | Hafenstein et al. (53) | |

| Fab-B | 14 | 0, 2, 4b, 5 | 91–93, 219, 226, 227, 228, 421, 425–428, 440, | Hafenstein et al. (53) | |

| Fab-E | 12 | 0, 2, 8 | 87, 88, 231, 233, 234, 298, 299, 300–302, 387, 556 | Hafenstein et al., (53) | |

| Fab-F | 14 | 0, 2, 8 | 87, 228, 231, 234, 236, 298, 299, 300–302, 387 | Hafenstein et al., (53) | |

| CPV | Fab-E | 4.1 | 0, 2, 3, 8 | 81, 85, 87, 88, 91, 101, 123, 231–237, 387, 390, 391, 554–565, 568, 570 | Organtini et al. (91) |

| Fab-14 | 12.4 | 2, 4b, 5 | 87, 88, 89, 91, 93, 95, 222, 223, 224, 227, 305, 309, 312, 324, 422, 423, 425–428 | Hafenstein et al. (53) | |

| Fab A3B10 | 23 | 0, 2, 3, 6 | 85, 87, 231, 232, 233, 296, 297, 299, 300, 301, 302, 303, 390, 391 | Wikoff et al. (129) | |

| Erythroparvovirus | |||||

| B19 | α-hu 860–55D | 3.2 | I, III, IV, HI-loop | 57–62, 197,198, 200, 256, 274, 278–280, 283, 470, 471, 473 | Sun et al. (122) |

CPV, canine parvovirus; FPV, feline panleukopenia virus; MVM, minute virus of mice.

Many of the antibodies binding to the CPV capsids also cross-react with FPV capsids due to high sequence identity. Seven capsid-antibody structures have been determined for FPV (53): FPV-Fab6, FPV-Fab8, FPV-Fab15, FPV-Fab16, FPV-FabB, FPV-FabE, and FPV-FabF, reconstructed to 8Å, 8.5Å, 10.5Å, 13Å, 14Å, 12Å, and 14Å resolution, respectively (Fig. 3). In these complex maps Fab6 and FabB bound to the icosahedral 3-fold protrusions involving VR-0, -2, -4b, and -5 (Table 2) (Fig. 3C) (53). This region has been termed the A-site that also includes Fab14 for CPV (89), Fab8, Fab15, and Fab16 bound to the 2/5-fold wall involving VR-0, -2, -6, -7, and -8 (Table 2) (Fig. 3C) (53), which is considered the B-site. FabE and FabF contact the side of the 3-fold protrusions and the 2/5-fold wall and their footprint extends across the 2-fold symmetry axis involving VR-0, -2, and -8 (Table 2) (Fig. 3C) (53). The FabE similarly binds on the CPV capsid, but the lower resolution suggested a larger area in FPV.

A single capsid-antibody complex structure, MVM-FabB7, has been determined for MVM immunosuppressive strain to 7Å (66). The B7 Fab bound at the icosahedral 3-fold symmetry axis with contacts involving VR-2, and -4b (Table 2) (Fig. 3C). The antibody was proposed to neutralize viral infection by blocking the attachment of virus to target cells. However, the addition of MAbB7 at various time points after virus attachment still neutralizes MVM infection (66). It was proposed that this postattachment neutralization mechanism could be a result of the blockage of pH mediated conformational changes of the capsid preventing the externalization of the VP1u region and genome release, in addition to blocking nuclear entry (66).

Antigenic interactions of erythroparvoviruses

The genus Erythroparvovirus contain a group of pathogenic viruses including primate erythroparvovirus 1, referred to as Parvovirus B19 (B19), the prototype of this genus (30). The capsids of B19 are composed of VP1 and VP2 in an approximate ratio of 1:10 (Fig. 4A, B). In contrast to the other Parvovirinae genera the N-termini of the B19 VP1 are believed to be located on the outside of the capsid and contain receptor-binding domains (74). Thus, in addition to the icosahedral capsid, antigenic reactivity for the VP1u region is also prevalent (77). B19 is one of the most common human pathogens worldwide, with seroprevalence in humans of up to 80% (103). B19 primarily infects erythroid progenitor cells, with outcomes ranging from asymptomatic to mild cold-like symptoms and various clinical conditions including arthropathy, erythema infectiosum or fifth's disease in children, chronic red cell aplasia, and hydrops fetalis (29,101). In addition, clinical conditions linked to B19 infection include epilepsy, autoimmune hepatitis, myocarditis, and meningitis (17,68,101). There is currently no vaccines available to protect against infection, although attempts have been made to use virus-like particles for this purpose (12,14,62).

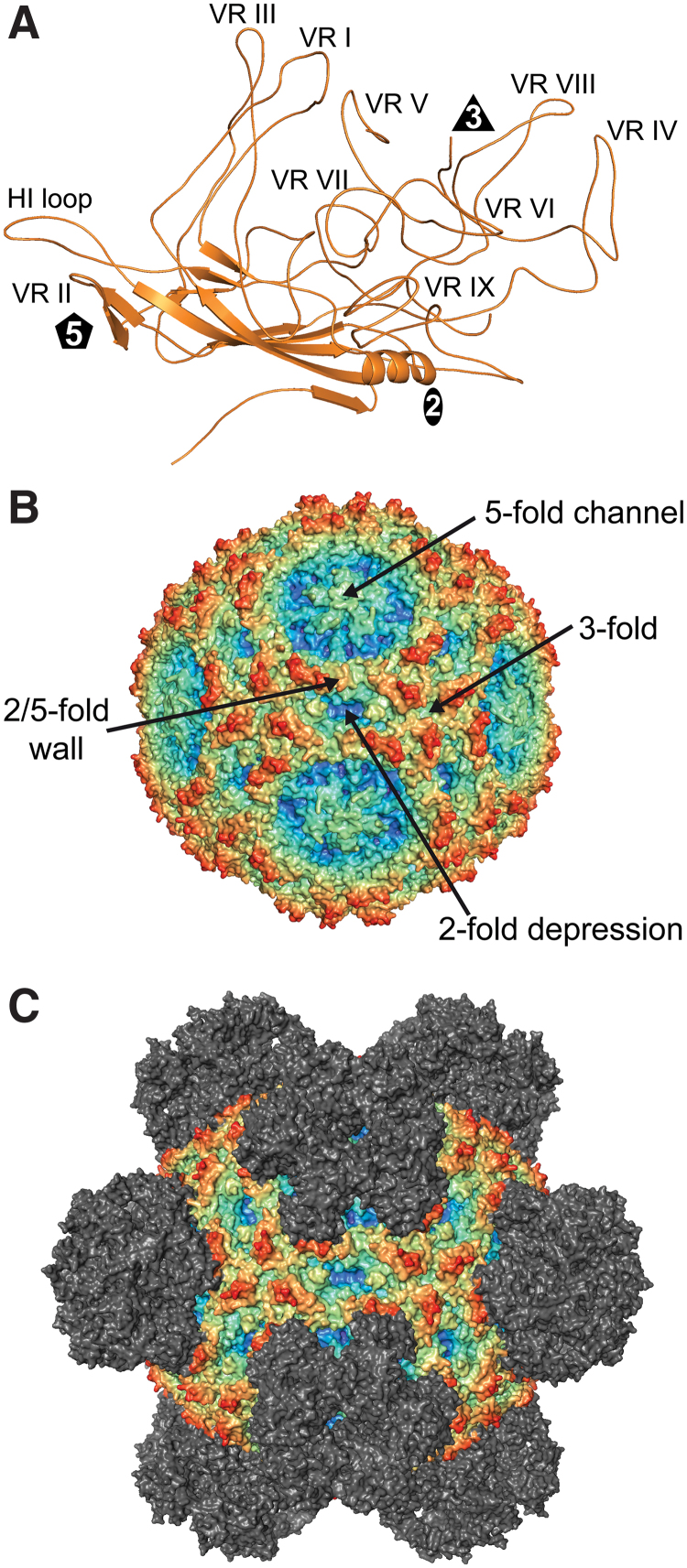

FIG. 4.

Antigenic Interaction of Erythroparvoviruses. (A) Structure of the VP monomer of Parvovirus B19. VRs are labeled. (B) Capsid surface representation of Parvovirus B19. The approximate locations of the 2-, 3-, and 5-fold axes are indicated along with the 2/5-fold wall and 3-fold protrusions. (C) Depiction of the cryo-reconstructed density map of the B19 viral capsid complexed to the Fab portion of a monoclonal antibody. The Fab was docked onto the viral capsid as identified by the cryo-reconstructed maps. The epitope spans the 5-fold axes of symmetry. The viral capsids in (A, B) are colored radially, such that regions closest to the center are colored purple, and those farthest away are colored red, with the Fabs colored gray, as indicated by the scale bar (bottom right in Fig. 1). These images were generated using PyMol (31). Color images are available online.

There have been efforts to understand the antigenic epitopes of the B19 viral capsid to help develop antigens for vaccination purposes. For this purpose, Mabs have been generated against the B19 VP1u or the VP2 region of native capsids (43,69,136). Antibodies against both regions neutralize B19 infection (43,106,108,109). The epitopes of several antibodies have been mapped using peptides, which indicate that different surface loops are contacted by different antibodies (21,108,109,136), and residues 30–42 of the VP1u (33,106). Currently, only a single capsid-antibody complex structure of B19 has been determined (122). In that study, the Fabs of the neutralizing human antibody 860-55D was used. This targets VP2 capsids (43). The B19-Fab complex structure was determined to a resolution of 3.2Å and showed binding of Fab close to the 5-fold axis, extending toward the 2/5-fold wall, and encompassing a conformational epitope that overlapped with three neighboring VP2 monomers (122) (Fig. 4C). Residues that are part of the epitope are located within VR-I, VR-III, the base of VR-IV (equivalent loops relative to the dependoparvoviruses), and the HI-loop (Table 2). Binding of the Fab to the B19 capsid resulted in the structural alteration of the HI-loop with a maximum Cα-Cα distance of 10Å at residue K471 (122). While the mechanism of neutralization by 860-55D has not been analyzed, the blocking of α5β1 integrin, a cellular co-receptor for B19, has been suggested. While all characterized monoclonal antibodies against the B19 capsid displayed neutralizing potential, some antibodies derived from human sera have been shown to enhance B19 infection by an antibody-dependent enhancement mechanism (126).

Commonalities in Antibody Epitopes Among the Parvovirinae

Despite low VP amino acid sequence identities among the different Parvovirinae genera, as low as 15%, the overall capsid morphology is conserved (85). Consequently, the epitopes mapped for viruses in different genera bind to similar regions of the capsid. Cross-reactivity of the antibodies between different viruses also exist but only within the same genus; for example, ADK1a binds to AAV1 and AAV6; 15C6 binds to HBoV1, HBoV3, and HBoV4; and FabE binds to CPV and FPV.

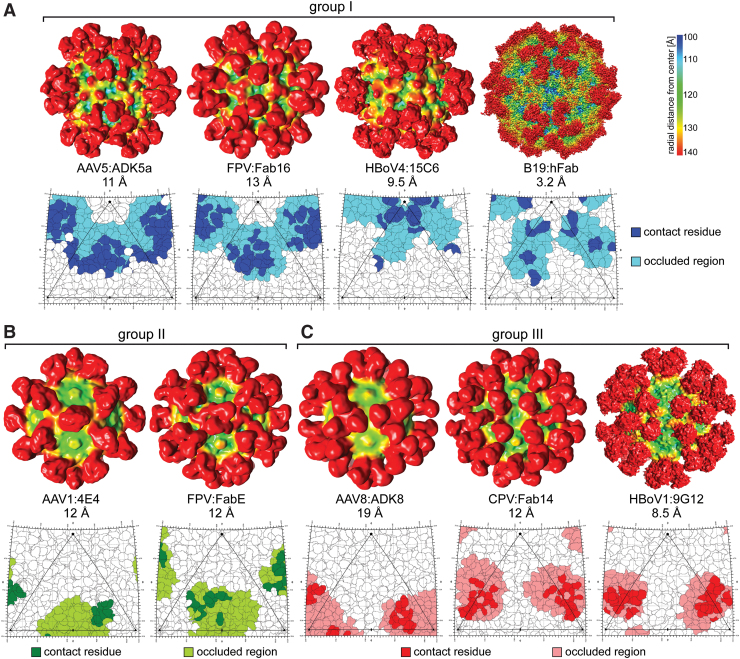

Based on the known capsid-antibody complex structures, most binding epitopes can be classified into three groups. Group I bind at or around the 5-fold symmetry axis and the 2/5-fold wall and include ADK1b, A20, ADK5a, ADK5b, 15C6, A3B10, MAb8, MAb15, Mab16, and 860-55D (Examples in Fig. 5A). Group II bind at the side of the 3-fold protrusions and the 2/5-fold wall leaning toward the 2-fold symmetry axis and include 4E4, ADK4, ADK6, MAbE, and MAbF (Examples in Fig. 5B). Antibodies of this group likely clash with each other across the 2-fold symmetry axis thereby preventing the binding of the symmetry related Fab. Group III antibodies bind at or near the 3-fold protrusions and include ADK1a, 5H7, C37-B, HL2476, ADK8, PAV9.1, 4C2, 9G12, 12C1, B7, Mab6, Mab14, and MabB (Fig. 5C). Similar to the group II, the Fabs that bind too close to the center of the 3-fold symmetry axis, for example, 5H7 against AAV1 and PAV9.1 against AAV9 (Fig. 1C), could prevent stoichiometric binding of all symmetry related capsid sites. The only antibody for which a footprint could not be clearly assigned is AAV5's 3C5 antibody. Due to its tangential binding pattern, the Fab is occluding most of the AAV5 capsid except the 3-fold protrusions and the 5-fold channel, and thus displays a hybrid of group I and II.

FIG. 5.

Commonalities in Parvovirus Antigenic Epitopes. Example cryo-EM density maps and 2D Roadmaps are shown, viewed down the 2-fold axis of symmetry, for common Fab binding regions for the dependoparvoviruses, protoparvoviruses, bocaparvoviruses, and erythroparvoviruses. (A) Group I—antibodies binding at or around the 5-fold symmetry axis and the 2/5-fold wall. (B) Group II—antibodies binding on the 2-fold facing wall of the 3-fold protrusions across the 2-fold axis. (C) Group III—antibodies binding at or near the 3-fold protrusions. The density maps are colored radially such that regions closest to the center of the capsid are colored blue, and those farthest away are colored red. Capsid density is shown mostly in blue, yellow, and green, while that corresponding to the Fabs are in red (see color key at the top right hand corner). The map images were generated using UCSF-chimera (95). The roadmap projections were generated with Radial Interpretation of Viral Electron density Maps (133). The viral asymmetric unit, with the 5-fold axis (pentagon), the 2-fold axis (ellipse), and the two 3-fold axes (triangles), is shown. Contact and occluded residues are indicated by different color shades. 2D, two-dimensional; cryo-EM, cryo-electron microscopy; RIVEM, Radial Interpretation of Viral Electron density Maps. Color images are available online.

All antibodies bind either to the 2/5-fold wall, 3-fold protrusions, or 5-fold region. While some of the antibodies occlude the 2-fold symmetry axes, none of the antibodies bind directly to residues within the 2-fold depression likely due to the inability of the Fabs CDRs to penetrate into the depression. The other capsid regions occluded by antibody binding, 2/5-fold wall, the 3-fold protrusions, and 5-fold regions including the DE and HI loops, are associated with functional properties of the parvovirus capsid. The 2/5-fold wall contains residues involved in receptor attachment and cellular trafficking (10,57,138), the 3-fold protrusions contain residues that serve in receptor attachment (1,28,67,75), the 5-fold channel is postulated as the portal for genome packaging and uncoating (16), and VP1u externalization during trafficking through the endo/lysosomal pathway (70,116). Thus, information from capsid–antibody complex structure studies informs on functional regions of the capsid and provides information for creation of potential vaccines and sites for engineering host immune system escape vectors for use in therapeutic gene delivery.

Author Disclosure Statement

M.A.-M. is a SAB member for Voyager Therapeutics, Inc., and AGTC, has a sponsored research agreement with StrideBio, Inc., Voyager Therapeutics, and Intima Biosciences, Inc., and is a consultant for Intima Biosciences, Inc. M.A.-M. is a co-founder of StrideBio, Inc. This is a biopharmaceutical company with interest in developing AAV vectors for gene delivery application.

Funding Information

The University of Florida COM and NIH GM082946 provided funds for the research efforts at the University of Florida.

References

- 1. Afione S, DiMattia MA, Halder S, et al. Identification and mutagenesis of the adeno-associated virus 5 sialic acid binding region. J Virol 2015;89:1660–1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Agbandje M, McKenna R, Rossmann MG, et al. Structure determination of feline panleukopenia virus empty particles. Proteins 1993;16:155–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agbandje-McKenna M, and Kleinschmidt J. AAV capsid structure and cell interactions. Methods Mol Biol 2011;807:47–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Agbandje-McKenna M, Llamas-Saiz AL, Wang F, et al. Functional implications of the structure of the murine parvovirus, minute virus of mice. Structure 1998;6:1369–1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Akache B, Grimm D, Pandey K, et al. The 37/67-kilodalton laminin receptor is a receptor for adeno-associated virus serotypes 8, 2, 3, and 9. J Virol 2006;80:9831–9836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Allander T, Tammi MT, Eriksson M, et al. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:12891–12896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Al-Zaidy SA, and Mendell JR. From clinical trials to clinical practice: Practical considerations for gene replacement therapy in SMA type 1. Pediatr Neurol 2019;100:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Angelova AL, Barf M, Geletneky K, et al. Immunotherapeutic potential of oncolytic H-1 parvovirus: hints of glioblastoma microenvironment conversion towards immunogenicity. Viruses 2017;9:382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arthur JL, Higgins GD, Davidson GP, et al. A novel bocavirus associated with acute gastroenteritis in Australian children. PLoS Pathog 2009;5:e1000391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aydemir F, Salganik M, Resztak J, et al. Mutants at the 2-fold interface of adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) structural proteins suggest a role in viral transcription for AAV capsids. J Virol 2016;90:7196–7204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ball-Goodrich LJ, Paturzo FX, Johnson EA, et al. Immune responses to the major capsid protein during parvovirus infection of rats. J Virol 2002;76:10044–10049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ballou WR, Reed JL, Noble W, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant parvovirus B19 vaccine formulated with MF59C.1. J Infect Dis 2003;187:675–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bennett AD, Wong K, Lewis J, et al. AAV6 K531 serves a dual function in selective receptor and antibody ADK6 recognition. Virology 2018;518:369–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bernstein DI, El Sahly HM, Keitel WA, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a candidate parvovirus B19 vaccine. Vaccine 2011;29:7357–7363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blanco K, Prendas J, Cortes R, et al. Seroprevalence of viral infections in domestic cats in Costa Rica. J Vet Med Sci 2009;71:661–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bleker S, Sonntag F, and Kleinschmidt JA. Mutational analysis of narrow pores at the fivefold symmetry axes of adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids reveals a dual role in genome packaging and activation of phospholipase A2 activity. J Virol 2005;79:2528–2540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bock CT, Klingel K, and Kandolf R. Human parvovirus B19-associated myocarditis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1248–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boutin S, Monteilhet V, Veron P, et al. Prevalence of serum IgG and neutralizing factors against adeno-associated virus (AAV) types 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9 in the healthy population: implications for gene therapy using AAV vectors. Hum Gene Ther 2010;21:704–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bowles DE, McPhee SW, Li C, et al. Phase 1 gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy using a translational optimized AAV vector. Mol Ther 2012;20:443–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bretscher C, and Marchini A. H-1 parvovirus as a cancer-killing agent: past, present, and future. Viruses 2019;11:562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brown CS, Jensen T, Meloen RH, et al. Localization of an immunodominant domain on baculovirus-produced parvovirus B19 capsids: correlation to a major surface region on the native virus particle. J Virol 1992;66:6989–6996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buller RM, Janik JE, Sebring ED, et al. Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 completely help adenovirus-associated virus replication. J Virol 1981;40:241–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Calcedo R, Vandenberghe LH, Gao G, et al. Worldwide epidemiology of neutralizing antibodies to adeno-associated viruses. J Infect Dis 2009;199:381–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Calcedo R, and Wilson JM. Humoral immune response to AAV. Front Immunol 2013;4:341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Casto BC, Atchison RW, and Hammon WM. Studies on the relationship between adeno-associated virus type I (AAV-1) and adenoviruses. I. Replication of AAV-1 in certain cell cultures and its effect on helper adenovirus. Virology 1967;32:52–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chapman MS, and Agbandje-McKenna M. Atomic structure of viral particles. In: Bloom SFC, ME, Linden RM, Parrish CR, and Kerr JR, ed. Parvoviruses. London: Edward Arnold, Ltd., 2006:109–123. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cheng Y. Single-particle cryo-EM at crystallographic resolution. Cell 2015;161:450–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chipman PR, Agbandje-McKenna M, Kajigaya S, et al. Cryo-electron microscopy studies of empty capsids of human parvovirus B19 complexed with its cellular receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93:7502–7506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chorba T, Coccia P, Holman RC, et al. The role of parvovirus B19 in aplastic crisis and erythema infectiosum (fifth disease). J Infect Dis 1986;154:383–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cotmore SF, Agbandje-McKenna M, Canuti M, et al. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: parvoviridae. J Gen Virol 2019;100:367–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics Syste. San Carlos, CA: DeLano Scientific, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Di Pasquale G, Kaludov N, Agbandje-McKenna M, et al. BAAV transcytosis requires an interaction with beta-1-4 linked-glucosamine and gp96. PLoS One 2010;5:e9336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dorsch S, Kaufmann B, Schaible U, et al. The VP1-unique region of parvovirus B19: amino acid variability and antigenic stability. J Gen Virol 2001;82:191–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dunbar CA, Callaway HM, Parrish CR, et al. Probing antibody binding to canine parvovirus with charge detection mass spectrometry. J Am Chem Soc 2018;140:15701–15711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dutta M. Recent advances in single particle cryo-electron microscopy and cryo-electron tomography to determine the structures of biological macromolecules. J Indian Inst Sci 2018;98:231–245 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Edner N, Castillo-Rodas P, Falk L, et al. Life-threatening respiratory tract disease with human bocavirus-1 infection in a 4-year-old child. J Clin Microbiol 2012;50:531–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Elmlund D, Le SN, and Elmlund H. High-resolution cryo-EM: the nuts and bolts. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2017;46:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fahey JL, and McKelvey EM. Quantitative determination of serum immunoglobulins in antibody-agar plates. J Immunol 1965;94:84–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fakhiri J, Schneider MA, Puschhof J, et al. Novel chimeric gene therapy vectors based on Adeno-associated virus (AAV) and four different mammalian bocaviruses (BoV). Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2019;12:202–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Farkas SL, Zadori Z, Benko M, et al. A parvovirus isolated from royal python (Python regius) is a member of the genus Dependovirus. J Gen Virol 2004;85:555–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fitzpatrick Z, Leborgne C, Barbon E, et al. Influence of pre-existing anti-capsid neutralizing and binding antibodies on AAV vector transduction. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2018;9:119–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gao G, Vandenberghe LH, Alvira MR, et al. Clades of Adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J Virol 2004;78:6381–6388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gigler A, Dorsch S, Hemauer A, et al. Generation of neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies against parvovirus B19 proteins. J Virol 1999;73:1974–1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Giles AR, Govindasamy L, Somanathan S, et al. Mapping an Adeno-associated virus 9-specific neutralizing epitope to develop next-generation gene delivery vectors. J Virol 2018;92:1–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Girod A, Wobus CE, Zadori Z, et al. The VP1 capsid protein of adeno-associated virus type 2 is carrying a phospholipase A2 domain required for virus infectivity. J Gen Virol 2002;83:973–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Govindasamy L, Padron E, McKenna R, et al. Structurally mapping the diverse phenotype of adeno-associated virus serotype 4. J Virol 2006;80:11556–11570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gray JT, and Zolotukhin S. Design and construction of functional AAV vectors. Methods Mol Biol 2011;807:25–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Grekova SP, Raykov Z, Zawatzky R, et al. Activation of a glioma-specific immune response by oncolytic parvovirus minute virus of mice infection. Cancer Gene Ther 2012;19:468–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Grigorieff N, and Harrison SC. Near-atomic resolution reconstructions of icosahedral viruses from electron cryo-microscopy. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2011;21:265–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guo L, Wang Y, Zhou H, et al. Differential seroprevalence of human bocavirus species 1–4 in Beijing, China. PLoS One 2012;7:e39644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gurda BL, DiMattia MA, Miller EB, et al. Capsid antibodies to different adeno-associated virus serotypes bind common regions. J Virol 2013;87:9111–9124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gurda BL, Raupp C, Popa-Wagner R, et al. Mapping a neutralizing epitope onto the capsid of adeno-associated virus serotype 8. J Virol 2012;86:7739–7751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hafenstein S, Bowman VD, Sun T, et al. Structural comparison of different antibodies interacting with parvovirus capsids. J Virol 2009;83:5556–5566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Halder S, Ng R, and Agbandje-McKenna M. Parvoviruses: structure and infection. Future Virol 2012;7:253–278 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Harbison CE, Weichert WS, Gurda BL, et al. Examining the cross-reactivity and neutralization mechanisms of a panel of mAbs against adeno-associated virus serotypes 1 and 5. J Gen Virol 2012;93:347–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Huang LY, Halder S, and Agbandje-McKenna M. Parvovirus glycan interactions. Curr Opin Virol 2014;7:108–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Huang LY, Patel A, Ng R, et al. Characterization of the adeno-associated virus 1 and 6 sialic acid binding site. J Virol 2016;90:5219–5230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ilyas M, Mietzsch M, Kailasan S, et al. Atomic resolution structures of human bufaviruses determined by cryo-electron microscopy. Viruses 2018;10:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jose A, Mietzsch M, Smith K, et al. High resolution structural characterization of a new AAV5 antibody epitope toward engineering antibody resistant recombinant gene delivery vectors. J Virol 2019;93:1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kailasan S, Garrison J, Ilyas M, et al. Mapping antigenic epitopes on the human bocavirus capsid. J Virol 2016;90:4670–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kailasan S, Halder S, Gurda B, et al. Structure of an enteric pathogen, bovine parvovirus. J Virol 2015;89:2603–2614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kajigaya S, Fujii H, Field A, et al. Self-assembled B19 parvovirus capsids, produced in a baculovirus system, are antigenically and immunogenically similar to native virions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991;88:4646–4650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kantola K, Hedman L, Arthur J, et al. Seroepidemiology of human bocaviruses 1–4. J Infect Dis 2011;204:1403–1412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Karalar L, Lindner J, Schimanski S, et al. Prevalence and clinical aspects of human bocavirus infection in children. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010;16:633–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kashiwakura Y, Tamayose K, Iwabuchi K, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor receptor is a coreceptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. J Virol 2005;79:609–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kaufmann B, Lopez-Bueno A, Mateu MG, et al. Minute virus of mice, a parvovirus, in complex with the Fab fragment of a neutralizing monoclonal antibody. J Virol 2007;81:9851–9858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kern A, Schmidt K, Leder C, et al. Identification of a heparin-binding motif on adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids. J Virol 2003;77:11072–11081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kerr JR. The role of parvovirus B19 in the pathogenesis of autoimmunity and autoimmune disease. J Clin Pathol 2016;69:279–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kerr JR, O'Neill HJ, Deleys R, et al. Design and production of a target-specific monoclonal antibody to parvovirus B19 capsid proteins. J Immunol Methods 1995;180:101–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kronenberg S, Bottcher B, von der Lieth CW, et al. A conformational change in the adeno-associated virus type 2 capsid leads to the exposure of hidden VP1 N termini. J Virol 2005;79:5296–5303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kuck D, Kern A, and Kleinschmidt JA. Development of AAV serotype-specific ELISAs using novel monoclonal antibodies. J Virol Methods 2007;140:17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lang SI, Giese NA, Rommelaere J, et al. Humoral immune responses against minute virus of mice vectors. J Gene Med 2006;8:1141–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lee S, Kang IK, Kim JH, et al. Relationship between neutralizing antibodies against adeno-associated virus in the vitreous and serum: effects on retinal gene therapy. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2019;8:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Leisi R, Di Tommaso C, Kempf C, et al. The receptor-binding domain in the VP1u region of parvovirus B19. Viruses 2016;8:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lerch TF, and Chapman MS. Identification of the heparin binding site on adeno-associated virus serotype 3B (AAV-3B). Virology 2012;423:6–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Li Y, Ge X, Hon CC, et al. Prevalence and genetic diversity of adeno-associated viruses in bats from China. J Gen Virol 2010;91:2601–2609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lin CY, Chiu CC, Cheng J, et al. Antigenicity analysis of human parvovirus B19-VP1u protein in the induction of anti-phospholipid syndrome. Virulence 2018;9:208–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lloyd A, Piglowska N, Ciulla T, et al. Estimation of impact of RPE65-mediated inherited retinal disease on quality of life and the potential benefits of gene therapy. Br J Ophthalmol 2019;103:1610–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lochrie MA, Tatsuno GP, Christie B, et al. Mutations on the external surfaces of adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids that affect transduction and neutralization. J Virol 2006;80:821–834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Marchini A, Bonifati S, Scott EM, et al. Oncolytic parvoviruses: from basic virology to clinical applications. Virol J 2015;12:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. McCraw DM, O'Donnell JK, Taylor KA, et al. Structure of adeno-associated virus-2 in complex with neutralizing monoclonal antibody A20. Virology 2012;431:40–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Mietzsch M, Broecker F, Reinhardt A, et al. Differential adeno-associated virus serotype-specific interaction patterns with synthetic heparins and other glycans. J Virol 2014;88:2991–3003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Mietzsch M, Grasse S, Zurawski C, et al. OneBac: platform for scalable and high-titer production of adeno-associated virus serotype 1–12 vectors for gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther 2014;25:212–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Mietzsch M, Kailasan S, Garrison J, et al. Structural insights into human bocaparvoviruses. J Virol 2017;91:e00261–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Mietzsch M, Penzes JJ, and Agbandje-McKenna M. Twenty-five years of structural parvovirology. Viruses 2019;11:E362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mingozzi F, and High KA. Therapeutic in vivo gene transfer for genetic disease using AAV: progress and challenges. Nat Rev Genet 2011;12:341–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mingozzi F, and High KA. Immune responses to AAV vectors: overcoming barriers to successful gene therapy. Blood 2013;122:23–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Mori S, Takeuchi T, Enomoto Y, et al. Tissue distribution of cynomolgus adeno-associated viruses AAV10, AAV11, and AAVcy.7 in naturally infected monkeys. Arch Virol 2008;153:375–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Nelson CDS, Palermo LM, Hafenstein SL, et al. Different mechanisms of antibody-mediated neutralization of parvoviruses revealed using the Fab fragments of monoclonal antibodies. Virology 2007;361:283–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. O'Donnell J, Taylor KA, and Chapman MS. Adeno-associated virus-2 and its primary cellular receptor—cryo-EM structure of a heparin complex. Virology 2009;385:434–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Organtini LJ, Lee H, Iketani S, et al. Near-atomic resolution structure of a highly neutralizing Fab bound to canine parvovirus. J Virol 2016;90:9733–9742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Paglino JC, Ozduman K, and van den Pol AN. LuIII parvovirus selectively and efficiently targets, replicates in, and kills human glioma cells. J Virol 2012;86:7280–7291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Parrish CR. Pathogenesis of feline panleukopenia virus and canine parvovirus. Baillieres Clin Haematol 1995;8:57–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Parrish CR, and Carmichael LE. Antigenic structure and variation of canine parvovirus type-2, feline panleukopenia virus, and mink enteritis virus. Virology 1983;129:401–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 2004;25:1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Pillay S, Meyer NL, Puschnik AS, et al. An essential receptor for adeno-associated virus infection. Nature 2016;530:108–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Pollock RV, and Carmichael LE. Dog response to inactivated canine parvovirus and feline panleukopenia virus vaccines. Cornell Vet 1982;72:16–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Pratelli A, Cavalli A, Martella V, et al. Canine parvovirus (CPV) vaccination: comparison of neutralizing antibody responses in pups after inoculation with CPV2 or CPV2b modified live virus vaccine. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2001;8:612–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Pulicherla N, Shen S, Yadav S, et al. Engineering liver-detargeted AAV9 vectors for cardiac and musculoskeletal gene transfer. Mol Ther 2011;19:1070–1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Qing K, Mah C, Hansen J, et al. Human fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is a co-receptor for infection by adeno-associated virus 2. Nat Med 1999;5:71–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Qiu J, Soderlund-Venermo M, and Young NS. Human parvoviruses. Clin Microbiol Rev 2017;30:43–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Rocha EM, Di Pasquale G, Riveros PP, et al. Transduction, tropism, and biodistribution of AAV vectors in the lacrimal gland. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:9567–9572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Rohrer C, Gartner B, Sauerbrei A, et al. Seroprevalence of parvovirus B19 in the German population. Epidemiol Infect 2008;136:1564–1575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Roux KH. Immunoglobulin structure and function as revealed by electron microscopy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 1999;120:85–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Saasa N, Nalubamba KS, M'Kandawire E, et al. Seroprevalence of Canine Parvovirus in Dogs in Lusaka District, Zambia. J Vet Med 2016;2016:9781357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Saikawa T, Anderson S, Momoeda M, et al. Neutralizing linear epitopes of B19 parvovirus cluster in the VP1 unique and VP1-VP2 junction regions. J Virol 1993;67:3004–3009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Salganik M, Aydemir F, Nam HJ, et al. Adeno-associated virus capsid proteins may play a role in transcription and second-strand synthesis of recombinant genomes. J Virol 2014;88:1071–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Sato H, Hirata J, Furukawa M, et al. Identification of the region including the epitope for a monoclonal antibody which can neutralize human parvovirus B19. J Virol 1991;65:1667–1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Sato H, Hirata J, Kuroda N, et al. Identification and mapping of neutralizing epitopes of human parvovirus B19 by using human antibodies. J Virol 1991;65:5485–5490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Schmidt M, Katano H, Bossis I, et al. Cloning and characterization of a bovine adeno-associated virus. J Virol 2004;78:6509–6516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Schmidt M, Voutetakis A, Afione S, et al. Adeno-associated virus type 12 (AAV12): a novel AAV serotype with sialic acid- and heparan sulfate proteoglycan-independent transduction activity. J Virol 2008;82:1399–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Scott FW, and Geissinger CM. Long-term immunity in cats vaccinated with an inactivated trivalent vaccine. Am J Vet Res 1999;60:652–658 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Scott LJ. Alipogene tiparvovec: a review of its use in adults with familial lipoprotein lipase deficiency. Drugs 2015;75:175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Shen S, Troupes AN, Pulicherla N, et al. Multiple roles for sialylated glycans in determining the cardiopulmonary tropism of adeno-associated virus 4. J Virol 2013;87:13206–13213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Snijder J, van de Waterbeemd M, Damoc E, et al. Defining the stoichiometry and cargo load of viral and bacterial nanoparticles by Orbitrap mass spectrometry. J Am Chem Soc 2014;136:7295–7299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Sonntag F, Bleker S, Leuchs B, et al. Adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids with externalized VP1/VP2 trafficking domains are generated prior to passage through the cytoplasm and are maintained until uncoating occurs in the nucleus. J Virol 2006;80:11040–11054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Sonntag F, Kother K, Schmidt K, et al. The assembly-activating protein promotes capsid assembly of different adeno-associated virus serotypes. J Virol 2011;85:12686–12697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Sonntag F, Schmidt K, and Kleinschmidt JA. A viral assembly factor promotes AAV2 capsid formation in the nucleolus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:10220–10225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Srivastava A. In vivo tissue-tropism of adeno-associated viral vectors. Curr Opin Virol 2016;21:75–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Steinel A, Parrish CR, Bloom ME, et al. Parvovirus infections in wild carnivores. J Wildlife Dis 2001;37:594–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Summerford C, and Samulski RJ. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J Virol 1998;72:1438–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Sun Y, Klose T, Liu Y, et al. Structure of parvovirus B19 decorated by Fabs from a human antibody. J Virol 2019;93:e01732–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Tseng YS, Gurda BL, Chipman P, et al. Adeno-associated virus serotype 1 (AAV1)- and AAV5-antibody complex structures reveal evolutionary commonalities in parvovirus antigenic reactivity. J Virol 2015;89:1794–1808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Tseng YS, Vliet KV, Rao L, et al. Generation and characterization of anti-Adeno-associated virus serotype 8 (AAV8) and anti-AAV9 monoclonal antibodies. J Virol Methods 2016;236:105–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Vaisanen E, Mohanraj U, Kinnunen PM, et al. Global distribution of human protoparvoviruses. Emerg Infect Dis 2018;24:1292–1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. von Kietzell K, Pozzuto T, Heilbronn R, et al. Antibody-mediated enhancement of parvovirus B19 uptake into endothelial cells mediated by a receptor for complement factor C1q. J Virol 2014;88:8102–8115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Weitzman MD, and Linden RM. Adeno-associated virus biology. Methods Mol Biol 2011;807:1–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Weller ML, Amornphimoltham P, Schmidt M, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor is a co-receptor for adeno-associated virus serotype 6. Nat Med 2010;16:662–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Wikoff WR, Wang G, Parrish CR, et al. The structure of a neutralized virus: canine parvovirus complexed with neutralizing antibody fragment. Structure 1994;2:595–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Wistuba A, Weger S, Kern A, et al. Intermediates of adeno-associated virus type 2 assembly: identification of soluble complexes containing Rep and Cap proteins. J Virol 1995;69:5311–5319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Wobus CE, Hugle-Dorr B, Girod A, et al. Monoclonal antibodies against the adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV-2) capsid: epitope mapping and identification of capsid domains involved in AAV-2-cell interaction and neutralization of AAV-2 infection. J Virol 2000;74:9281–9293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Wu Z, Miller E, Agbandje-McKenna M, et al. Alpha2,3 and alpha2,6 N-linked sialic acids facilitate efficient binding and transduction by adeno-associated virus types 1 and 6. J Virol 2006;80:9093–9103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Xiao C, and Rossmann MG. Interpretation of electron density with stereographic roadmap projections. J Struct Biol 2007;158:182–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Yan Z, Keiser NW, Song Y, et al. A novel chimeric adenoassociated virus 2/human bocavirus 1 parvovirus vector efficiently transduces human airway epithelia. Mol Ther 2013;21:2181–2194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Yan Z, Zou W, Feng Z, et al. Establishment of a high-yield recombinant adeno-associated virus/human bocavirus vector production system independent of bocavirus nonstructural proteins. Hum Gene Ther 2019;30:556–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Yoshimoto K, Rosenfeld S, Frickhofen N, et al. A second neutralizing epitope of B19 parvovirus implicates the spike region in the immune response. J Virol 1991;65:7056–7060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Zadori Z, Szelei J, Lacoste MC, et al. A viral phospholipase A2 is required for parvovirus infectivity. Dev Cell 2001;1:291–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Zhang R, Cao L, Cui M, et al. Adeno-associated virus 2 bound to its cellular receptor AAVR. Nat Microbiol 2019;4:675–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]