Abstract

Objective:

African Americans and Latinos/Hispanics have a higher prevalence of dementia compared to non-Latino Whites. This scoping review aims to synthesize non-pharmaceutical interventions to delay or slow age-related cognitive decline among cognitively healthy African American and Latino older adults.

Design:

A literature search for articles published between January 2000 and May 2019 was performed using the databases PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Web of Science. Relevant cited references and grey literature were also reviewed. Four independent reviewers evaluated 1,181 abstracts, and full-article screening was subsequently performed for 145 articles. The scoping review consisted of eight studies, which were evaluated according to peer-reviewed original manuscript, non-pharmaceutical intervention, cognitive function as an outcome, separate reporting of results for African American and Latinos, minimum age of 40, and conducted in the United States. A total of 8 studies were considered eligible and were analyzed in the present scoping review.

Results:

Eight studies were identified. Four studies focused on African Americans and four focused on Latinos. Through the analysis, results indicated cognitive training-focused interventions were effective in improving memory, executive function, reasoning, visuospatial, psychological function, and speed among African Americans. Exercise interventions were effective in improving cognition among Latinos.

Conclusion:

This scoping review identified effective non-pharmaceutical interventions among African American and Latinos. Effective interventions focused on cognitive training alone for African Americans and exercise combined with group educational sessions for Latinos. Future research should explore developing culturally appropriate non-pharmaceutical interventions to reduce disparities and to enhance cognition among older African American and Latinos.

Keywords: Dementia, Minorities, Aging, Cognitive Training, Exercise, Diet

Introduction

Approximately 5.4 million Americans have dementia and the prevalence is expected to double by 2050 (Association 2017). Dementia is one of the major causes of mortality and disability in later life, has a significant health impact on family members and caregivers and is more costly than cancer and heart disease (Association 2017, Lopez et al. 2006, Sallim et al. 2015, World Health Organization 2012). In the absence of effective disease-modifying medications there is now a major effort to prevent cognitive decline or delay the onset of dementia among older adults, particularly through behavioral interventions (National Academies of Sciences 2017).

A recent systematic review stated that encouraging, although inconclusive, evidence supports that lifestyle interventions may delay or slow age-related cognitive decline (National Academies of Sciences 2017). This report found the strongest evidence came from cognitive training and physical activity (PA) interventions based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Two years earlier, a less strict systematic review of 17 non-pharmaceutical RCTs found that out of several interventions, PA had specific favorable results on cognition (Barnett et al. 2015).

The older U.S. adult population is expected to grow more racially and ethnically diverse. Specially, by 2060 the older African American (AA) population is expected to rise from 9% to 12% and older Latino population will rise from 8% to 22%, while the older non-Hispanic White population is expected to decrease from 78% to 55% (Colby and Ortman). It is important to note that currently AAs (13.8%) and Latinos (12.2%) 65 years and older have higher prevalence of chronic diseases and conditions including cognitive disorders (i.e. ADRD) compared to non-Hispanic Whites (10.3%) and by 2060 researchers estimate that 3.2 million Latinos and 2.2 million AAs will have ADRD (Matthews et al. 2019).

Previous research has indicated that non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) such as exercise and diet are associated with positive cognitive benefits (i.e. improved memory performance, visuospatial function) (Vidoni et al. 2015, Erickson et al. 2011, Kramer et al. 1999, Maass et al. 2015, Ngandu et al. 2015, Morris et al. 2015). The current research landscape examining NPIs for older adults has primarily focused on non-Hispanic Whites (Babulal et al. 2018, Burchard et al. 2003, Fuller-Thomson et al. 2009), resulting in limited knowledge regarding cognitive health outcomes and a thorough understanding of culturally appropriate NPI strategies for racial/ethnic minorities. Additionally, systematic reviews have indicated inclusion of minorities in trials is minimal, which makes extrapolating results to these groups impossible (Zhou et al. 2017, Faison et al. 2007, Watson et al. 2014, National Academies of Sciences 2017, Barnett et al. 2015). Barnett’s (2015) systematic review indicated that 7 of the 37 studies reviewed indicated race and of the 7 studies 6 reported having a majority White sample. With the growing rate of racially/ethnic populations and current disproportional impact of ADRD it is imperative to 1) understand the role NPIs have on cognitive health outcomes and to 2) identify culturally tailored NPIs that have found to be effective in positive cognitive health outcomes among older AAs and Latinos. In response to the lack of a comprehensive and critical review of NPIs among AAs and Latinos, this scoping review aims to synthesize NPIs designed to delay or slow age-related cognitive decline among cognitively healthy African American and Latino older adults (Association 2017, Zhou et al. 2017, Faison et al. 2007, Watson et al. 2014, National Academies of Sciences 2017).

Methods

Search Strategy

We performed a literature search between May 1 – May 7 in 2019 in PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Web of Science. We also searched for relevant cited references and grey literature. A combination of keywords and controlled vocabulary terms were used to identify the NPI in older AA and Latino populations. The type of intervention was searched with the Mesh terms ‘Exercise’ or Physical activity’ or ‘physical activities’ or ‘recreation’ or ‘sensory art therapies’ or ‘dancing’ or ‘diet’ or ‘nutrition therapy’ or ‘dietary supplements’ or ‘sleep’. Table 1 shows the final search terms used in PubMed, CINAHI, PycINFO, and Web of Science. We included only English language studies as this is the primary research language of the U.S. The search was limited to studies from January 1, 2000 to April 30, 2019 by applying the databases’ publication date limit feature. The search strategy resulted 1,178 unique results after de-duplicating using the bibliographic software EndNote (Endnote X8, Clarivate Analytics, Clarivate.com).

Table 1.

Search Terms for Scoping Review

| PubMed |

| ((((((((((“exercise”[MeSH Terms] OR “exercise”[tiab] OR “physical activity”[tiab] OR “physical activities”[tiab] OR “Recreation”[Mesh] OR “Sensory Art Therapies”[Mesh] OR “art”[MeSH Terms] OR “art”[tiab] OR “dancing”[MeSH Terms] OR “dancing”[tiab] OR “dance”[All Fields] OR “Dance Therapy”[Mesh] OR “Art therapy”[tiab] OR “Recreation”[Mesh] OR “Recreation Therapy”[Mesh] OR “art therapies”[All Fields] OR “Diet”[Mesh] OR “diet”[tiab] OR “nutritional status”[MeSH Terms] OR “nutritional status”[All Fields] OR “nutrition”[tiab] OR “nutritional”[tiab] OR “Nutritional Supplementation”[All Fields] OR “Nutrition Therapy”[Mesh] OR “Dietary Supplements”[Mesh] OR “cognitive training”[tiab] OR Cognition-based interventions OR “sleep therapy”[tiab] OR “sleep”[MeSH Terms] OR “sleep”[tiab] OR “Memory interventions”[tiab])) AND (“cognition”[MeSH Terms] OR “cognition”[tiab] OR “cognitive”[tiab] OR “Retention (Psychology)”[Mesh] OR “executive function”[MeSH Terms] OR “Cognitive function”[tiab] OR “Cognitive functions”[tiab] OR “Cognitive functioning”[tiab] OR “Cognitive Decline”[tiab] OR “memory”[MeSH Terms] OR “memory”[tiab] OR forgetting[tiab] OR “Processing Speed”[tiab] OR “Memory loss”[tiab] OR “executive functioning”[tiab] OR “cognitive functioning”[tiab] OR “episodic memory”[tiab] OR “problem solving”[tiab] OR Neurocognitive[tiab])) AND (“Hispanic Americans”[Mesh] OR Hispanics OR Hispanic OR Latino OR Latinos OR Latina OR Latinas OR “Mexican American” OR “Latin- American” OR “Mexican Americans” OR “African American” OR “African Americans” OR “African Americans”[Mesh] OR black OR blacks)) AND (“Aged”[Mesh] OR “Aged, 80 and over”[Mesh] OR aging[tiab] OR ageing[tiab] OR Aged[tiab] OR seniors[tiab] OR elderly[tiab] OR elder[TIAB] OR older[tiab] OR Geriatrics OR Geriatric OR Gerontology))))))) |

| CINAHL |

| ((MH “Exercise+”) OR exercise OR (MH “Physical Activity”) OR “physical activity” OR “physical activities” OR (MH “Dancing”) OR Dance OR (MH “Dance Therapy”) OR (MH “Art Therapy”) OR “art therapies” OR Art OR (MH “Meditation”) OR (MH “Music Therapy”) OR (MH “Spiritual Healing”) OR (MH “Tai Chi”) OR (MH “Yoga+”) OR Recreation OR (MH “Dietary Supplements+”) OR (MH “Nutritional Support+”) OR (MH “Dietary Supplementation”) OR (MH “Home Nutritional Support”) OR (MH “Nutrition”) OR (MH “Diet+”) OR nutrition OR nutritional OR “nutritional status” OR “nutritional supplementation” OR supplements OR diet OR (MH “Cognitive Therapy+”) OR “cognitive training” OR “sleep therapy” OR sleep OR (MH “Sleep”) OR Cognition-based interventions) AND ((MH “Cognition”) OR cognition OR cognitive OR retention OR “cognitive function” OR “cognitive functions” OR “cognitive functioning” OR “cognitive decline” OR “Cognition-based interventions” OR (MH “Executive Function”) OR (MH “Memory”) memory OR (MH “Problem Solving”) OR “processing speed” OR “memory interventions” OR “memory loss” OR “executive functioning” OR “episodic memory” OR “problem solving” OR neurocognitive) AND ((MH “Hispanics”) OR “Hispanic Americans” OR Hispanics OR Hispanic OR Latino OR Latinos OR Latina OR Latinas OR “Mexican American” OR Latin-American OR (MH “Blacks”) OR Black OR “African Americans” OR “African American”) AND ((MH “Aged+”) OR aging OR ageing OR Aged OR seniors OR elderly OR elder OR older OR geriatrics OR geriatric) |

| PycINFO |

| ((DE “Exercise”) OR (DE “Yoga”) OR “Tai Chi” OR swimming OR Exercise OR (DE “Physical Activity”) OR “physical activity” OR “physical activities” OR (DE “Dance”) OR dancing OR dance OR music OR (DE “Dance Therapy”) OR art OR (DE “Art Therapy”) OR “Art therapies” OR (DE “Recreation”) OR (DE “Recreation Therapy”) OR recreation OR (DE “Diets”) OR diet OR (DE “Dietary Supplements”) OR (DE “Nutrition”) OR “Nutritional Status” OR Nutrition OR “Nutritional Supplementation” OR “Nutrition therapy” OR (DE “Cognitive Behavior Therapy”) OR (DE “Cognitive Therapy”) OR “cognitive training” OR Cognition-based interventions OR (DE “Sleep”) OR (DE “Sleep Treatment”) OR sleep) AND ((DE “Cognition”) OR (DE “Cognitive Impairment”) OR (DE “Cognitive Processing Speed”) OR cognition OR cognitive OR cognitive function* OR cognitive declin* OR (DE “Executive Function”) OR (DE “Cognitive Ability”) OR (DE “Retention”) OR retention OR DE “Recall (Learning)” OR DE “Recognition (Learning)” OR (DE “Forgetting”) OR (DE “Memory”) OR (DE “Cognitive Processing Speed”) OR (DE “Memory”) OR (DE “Memory Decay”) OR “memory decline” OR “memory loss” OR memory OR “executive functioning” OR “cognitive functioning” OR “episodic memory” OR “problem solving” OR Neurocognitive) AND ((DE “Latinos/Latinas”) OR (DE “Mexican Americans”)OR Hispanic Americans OR Hispanic OR Hispanic OR Latino OR Latinas OR “Mexican American” OR Latin-American (DE “Blacks”) OR Black OR Blacks OR “African Americans” OR “African American”) AND ((DE “Gerontology”) OR (DE “Geriatrics”) OR geriatric OR (DE “Aging”) OR aging OR ageing OR aged OR seniors OR elderly OR elder OR older) |

| Web of Science |

| #4 AND #3 AND #2 AND #1 |

|

TOPIC: (Aged OR aging OR ageing OR seniors OR elderly OR elder OR older OR Geriatrics OR Geriatric OR Gerontology) |

| TS=(“Hispanic Americans” OR Hispanics OR Hispanic OR Latino OR Latinos OR Latina OR Latinas OR “Mexican American” OR “Latin-American” OR “Mexican Americans” OR “African American” OR “African Americans” OR black OR blacks) |

|

TOPIC: (cognition OR cognitive OR Retention OR “executive function” OR “Cognitive function” OR “Cognitive functioning” OR “Cognitive Decline” OR memory OR forgetting OR “Processing Speed” OR “Memory loss” OR “executive functioning” OR “cognitive functioning” OR “episodic memory” OR “problem solving” OR Neurocognitive) |

|

TOPIC=(exercise OR “physical activity” OR “physical activities” OR “Recreation” OR “Sensory Art Therapies” OR art OR dancing OR dance OR Dance Therapy OR Art therapy OR Recreation OR “Recreation Therapy” OR “art therapies” OR Diet OR “nutritional status” OR nutrition OR nutritional OR “Nutritional Supplementation” OR “Nutrition Therapy” OR “Dietary Supplements” OR “cognitive training” OR “Cognition-based interventions” OR “sleep therapy” OR sleep OR “Memory interventions”) |

Study Selection

We screened original studies that reported on NPI with a cognitive function outcome among non-demented AA and Latinos. The criteria for inclusion were: 1) peer reviewed original manuscripts including 2) NPI trials, independent of the number of intervention arms, 3) cognitive function as an outcome, 4) reporting results for AA and/or Latinos separately, 5) with a minimum age of 40, and 6) conducted in the United States (U.S.). We chose the age limit of 40 in order to maximize the sensitivity of the results and due to some databases vaguely performing the age limit feature. Additionally, it is important to note that we only included U.S. studies focused on Latinos and AAs, which are racial and ethnic minority identities common in the US, and are best interpreted within defined geopolitical and social boundaries. The literature review was conducted in three phases. Phase 1 consisted of double screening all titles and abstracts by four authors (AS, JP, EVM, and EDV). Reviewers used a duplicate-free library to independently review each title and abstract and excluded non-related ones. For Phase 2, the same four authors double-reviewed the full texts of the positively screened articles to further exclude those not meeting the eligibility criteria. Phase 3 consisted of the data extraction, conducted by two of the authors (ARS, and EDV).

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data were extracted into a spreadsheet with the following information: first author, year, city and state of intervention, setting of intervention, demographic and clinical characteristics of participants, acculturation assessment, type of trial, specific ethnoracial minority group(s), components of the intervention, intervention nature, cultural and individual tailoring, modality of the intervention, operationalization of cognitive function, and main findings. We categorized domains and subdomains based on DSM-5 categories and the main author determined the cognitive function based on the DSM-5 criteria (Sachdev et al. 2014). This review followed a standard framework for conducting scoping reviews (Colquhoun et al. 2014).

Results

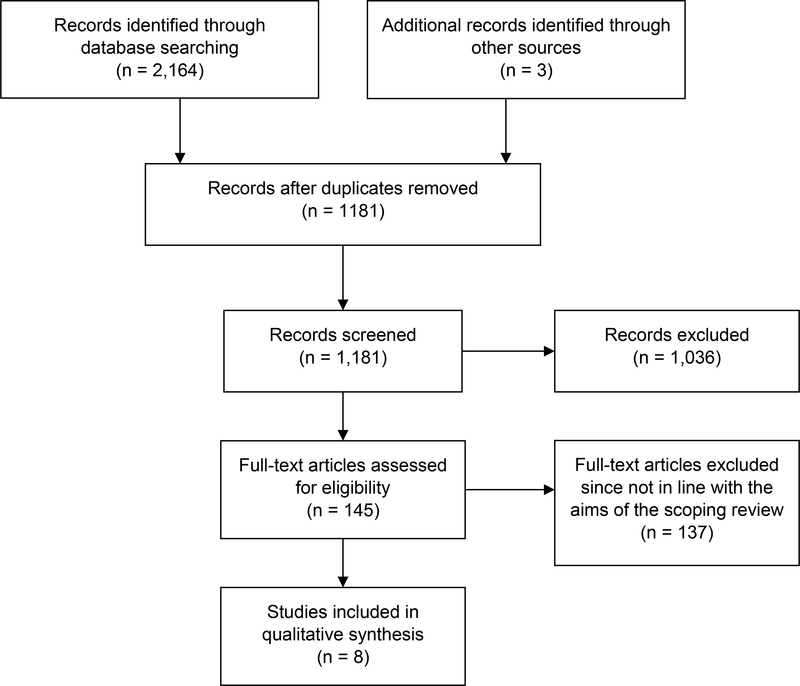

A total of 2,164 articles were identified and three manuscripts were added manually. In total, 1,181 articles were identified after duplicates were removed. After review of abstracts, an additional 1,036 articles were excluded. Of the 145 articles reviewed; 137 were excluded for one or more of the these reasons: 1) the study was not a peer reviewed original manuscript (n=22), 2) the study was not a trial (n=30), 3) treatment was pharmaceutical (n=20), 4) not conducted in the United States (n=14), 5) did not report the results for AA and/or Latinos separately (n=62), 6) included individuals < 40 years old (n=42), 7) included individuals who were not cognitively normal at baseline (n=94), and 8) cognition was not a measured outcome (n=95). Note that these numbers do not add up to 100% as most studies were excluded for two or more reasons. A total of 8 articles were eligible for inclusion. Study selection flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram

Two types of trial designs were identified across the 8 studies, including RCT (n=7) and single group pre-post trials (n=1). Among the RCT, all studies randomized to two groups except the ACTIVE trial that included three groups (Zahodne et al. 2015). Table 2 shows a brief summary of the study characteristics and main outcomes.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Non-Pharmacological Interventions on Cognitive Functioning Among Older African Americans and Latinos

| Author (year) | N (TC, CC) | Race/ethnicity | Age range (mean) | Type of intervention/delivery mode | Duration/hours | Measurement(s) of outcome(s) | Outcome(s)/Key finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carlson et al. (2008) | 128 (70, 58) | African American Other |

60+ (69) | Cognition intervention intensive preparatory training and service vs senior service over the ensuing academic year | Academic Yr Everyday/32 h |

Executive function (TMT A and B, Rey-O complex figure text); Nonverbal memory (delayed recall or the CFT following a 15-min filled interval); verbal memory (three-learning trials with a list of 20 common words from the Iowa Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly-Immediate and followed by a verbal recall) | Improvement in cognition from baseline to follow-up between intervention and control group; |

| Hernandez et al. (2018) | 572 | Hispanic/Latino | NR (73.13) | Group session + exercise In person, group session and exercise class |

4 weeks/ 1h class + 1 h exercise | Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) Scale (GDS) |

Cognitive measures were associated with impaired cognitive functioning among older adults in the exercise intervention |

| Marquez et al. (2015) | 13 (9, NR) | Hispanic/Latino | 55 – 73 (65.2) | Dance sessions In person, group sessions | 13 weeks/1 h per week | East Boston Memory Test, Stroop Neuropsychological Screening Test, Numbers Comparison Test, Verbal Fluency | Improvement in test scores from pre to post |

| Marquez et al. (2017) | 57 (28, 29) | Hispanic/Latino | 55 – 80, TC (64.8), CC (66.4) | Dance sessions In person, group sessions |

16 weeks/ 1 h per week | NACC UDS: Executive function (Trail Making Test, Color task from Stroop, Word fluency, symbol-digit modalities test); Working memory (digit span test, digit ordering test); Episodic memory (logical memory I and II) | Improvement in global and individual function; Dance group performed significantly better in executive function. Dance group and CG improved in global cognition |

| McDougall et. al (2010) | 265 (135, NR) | African American, Hispanic/Latino, White | 65 – 94 IG(74.69) CG (74.83) |

Cognitive training using Senior WISE trial (memory vs. health training) | 2 times/week for 4 weeks 12 h | Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Revised, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised, Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test | Latinos and African Americans performed better than Whites on visual memory. African Americans performed better over time on instrumental activities of daily living |

| Oweusu et al. (2019) | 260 (130, 130) | African American | NR (68.2) | Dietary supplementation for cognition/administration of supplementation by pill at home | 36 months/daily | Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) | MMSE scores increased in both IG and CG. No significant difference between IG and CG |

| Pierda et al. (2017) | 571 (279, 292) | Hispanic/Latino | NR (73.12) | Group discussion + exercise In person lecture and exercise class |

24 months 4 weeks/ 1 h class + 1h exercise Year 1: monthly follow-up Year 2: every 2 months follow-up |

Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) | Improvement in 3MS from baseline to year 1 and 2; Participants in both trial arms had higher cognitive functioning scores at year 1 and 2 compared to baseline; no difference between IG and CG |

| Zahonde et al. (2015) | 2062 Speed group: 687 Memory group: 693 Reasoning group: 682 Control: N/A |

African American, White | 65 + (73.5) AA (71.8) |

Cognitive training: memory vs. reasoning vs. speed Individual and small group cognitive exercises |

NR/ 1h – 1.25h per week | Memory (Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, Paragraph Recall Test from RVMT); Reasoning (Word Series, Letter Series, and Letter Sets); Speed (Useful Field of View) | African Americans in IG showed improvements in reasoning, memory, and speed from cognitive training |

Note: AA = African American. CG= control group; IG = intervention group; NR = not reported

Overview of Characteristics of Participants in Included Studies

A total of 3,928 participants were recruited across eight studies examined. Five studies reported specifically on Latinos (n=1,258), and three reported specifically on AA (n=1,015). Participants’ age ranged from 55 to 94 years. Participants were predominately women (76.8% - 100%) across all eight studies. Among studies that reported geographical area (n=5), all reported taking place in urban areas. Studies that reported study setting (n=6) varied from community centers (n=2), senior centers (n=3), to public schools (n=1). Lastly, four studies reported acculturation with regards to preference of language in the delivery of the interventions. Among these studies (n=3) 33.3%, 73.0%, and 96.4% of participants reported Spanish as their preference.

Focus and Outcomes of Included Studies

All studies assessed the cognitive domain of memory as an outcome. Also, several studies assessed additional cognitive domains including reasoning, speed, executive function, and global cognition. The most common instruments used to assess cognitive function were Modified Mini-Mental State (n=2), Trail Making Test (n=2), and the Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test (n=2).

Over half of the interventions (57%) included some form of exercise. Of the exercise-focused interventions (n=4), the target population in all was Latino and the study designs included RCT (n=3) and a single group design (n=1). Specifically, two studies reported using dance sessions, which showed improvement in executive function (Marquez et al. 2017) and global cognition (Marquez et al. 2015, Marquez et al. 2017) among participants. Also, two studies reported using structured exercise training in the interventions, in which one resulted in higher cognitive function scores (Piedra et al. 2017) and one showed promise of having an positive impact on cognitive function in older Latinos (Hernandez et al. 2018). Of the studies that examined executive function, participants in the intervention groups performed significantly better compared to the control group (Carlson et al. 2008, Marquez et al. 2017).

Interventions in seven studies were delivered using in-person group sessions and one study indicated using both group and individual cognitive exercises as part of the intervention (Zahodne et al. 2015). Duration of interventions ranged from four weeks to 36 months. Intensity of study interventions varied from 1-hour sessions (n=5), 1.5-hour sessions (n=1), to 2.28 hour sessions (n=1). Lastly, most of the studies examined were tailored to culture (n=4). Of the tailored studies, two were developed considering Latino’s appreciation of dancing and one was tailored first through focus groups to incorporate important cultural themes. Six (75%) of the studies examined reported language of intervention, in which most were delivered in both English and Spanish (n=3).

Characteristics of Included Studies focused on African Americans

Four studies primarily included AA within their sample. However, one of the studies had a sample of AA under 100 (11%, n=29) (McDougall et al. 2010). Of the three studies that had larger sample sizes, participants were mostly female with low education and income. Acculturation was not assessed in any of the four studies focused on AA.

Recruitment efforts varied across studies focused on AA. However, most studies indicated recruiting AA via churches and senior centers or senior targeted events (Carlson et al. 2008, McDougall et al. 2010, Owusu et al. 2019). Use of local media such as TV and print was also a recruitment tool found to be successful in reaching older AA (Carlson et al. 2008). All studies examined required AA participants to have no communication or vision problems. Further, most studies examined in this review indicated that individuals were excluded for having a history of conditions such as cancer or stroke.

Three of the four studies that specifically examined AA involved cognitive training as an intervention, and the training across the three studies varied. Cognitive training in Carlson et al. (2008) involved participants supporting reading achievement, library support, and classroom behavior for elementary aged children 15 hours a week during an academic school year. Memory training in McDougall et al. (2010) followed structured training topics (i.e. memory and health, memory beliefs and aging, internal and external memory strategies). Cognitive training by Zahonde et al. (2015) involved the use of the ACTIVE study memory training model (Jobe et al. 2001).

Additionally, the three studies that focused on cognitive training as an intervention varied in terms of type of the cognitive functions being measured ranging from memory (verbal and nonverbal), executive function, reasoning, visuospatial, psychological function to processing speed (Carlson et al. 2008, McDougall et al. 2010, Zahodne et al. 2015). Also, execution of the cognitive training varied across studies including group training (Carlson et al. 2008, McDougall et al. 2010) and a combination of individual and small group training (Zahodne et al. 2015). The fourth study focused on the consumption of vitamin D and its effects on cognition among AA in which types of cognition measured included memory, language, and orientation (Owusu et al. 2019).

Of the interventions focused on AA, three of the four studies reported increasing cognitive performance from baseline to follow-up. When compared to other racial/ethnic groups, the cognitive performance of AA was found to be higher in the memory domain compared to Latinos, and Whites (McDougall et al. 2010). One study, however indicated that the intervention was only slightly successful for supporting cognition in AA due to racial disparities found within memory and reasoning training gains compared to Whites (Zahodne et al. 2015). It is important to note that even though this study did not show an effect of the intervention on cognition among AA, there was an improvement in reasoning and memory performance in this group.

Main limitations of the examined NPI studies that focused on AA were having a sample size under 100, generalizability, and intervention duration. Examined studies reported a sample size of AA under 100 within the intervention group (Carlson et al. 2008, Zahodne et al. 2015). There was a lack of socioeconomically and educationally diverse AA represented reported in the examined studies and participants were more likely to be female, resulting in a low generalizability among AA (Zahodne et al. 2015, Carlson et al. 2008, McDougall et al. 2010, Owusu et al. 2019). Due to the short duration of NPI researchers were unable to determine if the intervention could enhance and maintain cognition over time among AA (Zahodne et al. 2015).

Characteristics of Included Studies Focused on Latinos

Of the eight included studies, four focused on interventions for Latinos. Acculturation was operationalized through focus groups that identified aspects of culture important to the Latino community or by delivering the intervention in Spanish. Three of the four examined studies indicated that at least 73% of participants preferred Spanish over English for intervention delivery (Marquez et al. 2017, Hernandez et al. 2018, Piedra et al. 2017). Recruitment efforts for Latinos were primarily through senior centers (Hernandez et al. 2018, Marquez et al. 2015, Piedra et al. 2017) and through established relationships from the lead investigator (Marquez et al. 2015, 2017).

Studies examined required Latino participants to be currently engaged in limited PA. Most studies excluded individuals currently engaging in regular PA or having health conditions/diseases such as a stroke. All four examined studies indicated that NPIs were group-oriented, held in person, and included a PA component. Cognitive outcomes varied in terms of domain measured, ranging from memory (verbal and nonverbal), executive function, reasoning, visuospatial, psychological function and speed. All four intervention studies were found to be effective in improving cognitive performance (Hernandez et al. 2018, Piedra et al. 2017).

The main limitations of the NPI Latino-focused studies were sample size, generalizability, minimal cognition measures, control group treatment, and not assessing intensity of PA in relation to cognition. Two examined studies reported sample sizes under 100, which may have impacted the ability to identify PA related improvements in other cognitive domains (Marquez et al. 2015, 2017). There was a lack of within-group cultural diversity reported in the represented sample across the examined studies. Most examined studies reported primarily Latinos of Mexican descent (Marquez et al. 2015, Piedra et al. 2017, Hernandez et al. 2018), or Latinos as a whole. Studies lacked details regarding other Latino groups such as Central/South American or Caribbean Latinos, which have shown to have poorer cognitive outcomes (Perales-Puchalt et al. 2020). This lack of within-group cultural diversity inherently creates barriers in translating evidence in practice when delivering NPIs to the increasingly diverse Latino population in the U.S. Moreover, due to recruitment strategies targeting public institutions such as senior centers, and interventions being carried out at a single site, results may not be generalizable to Latinos in other settings including primary care (Marquez et al. 2017, Hernandez et al. 2018). Two studies reported assessing and analyzing minimal cognitive measures, and reported including more measures may helped to better understand the effect of the intervention (Hernandez et al. 2018, Piedra et al. 2017). Of the studies examined that included a control group, two indicated that the control groups were not truly untreated and received part of the intervention such as health education (Piedra et al. 2017, Marquez et al. 2017). Lastly, interventions incorporating PA did not examine intensity in relation to cognition, as intensity of PA may have impacted cognition (Marquez et al. 2017).

Similarities/Differences Between African American and Latino Studies

Among the studies examined there were several similarities and differences found between AA and Latinos. Recruitment efforts were found to be similar between AA and Latinos, in which participants were primarily recruited through senior centers. However, AA were more likely to be recruited through churches compared to Latinos.

Seven of the eight interventions focused on AA and Latinos were found to be effective in improving cognition from baseline to follow-up. The biggest difference between interventions aimed at Latinos compared to AA was the intervention modality. All interventions for Latinos involved some type of PA and were all group oriented. In contrast, most interventions aimed at AA focused on cognitive training. Only one study with AA focused on a dietary intervention to improve cognition. Also, interventions for Latinos incorporated cultural activities within the intervention design such as dancing and acculturation (language) within the delivery of the intervention, which was not seen among intervention studies for AA.

Although all interventions measured cognition, NPI for AA incorporated more measures of cognition across examined studies compared to interventions for Latinos. Similar reported limitations of examined studies included sample size and generalizability. Differences in reported limitations were also found. Most AA-focused studies reported short duration of the intervention as a main limitation while examined studies focused on Latinos reported few measures of cognition and having a treated control group as main limitations.

Discussion

This review reports results from nearly 20 years of interventions aimed at improving cognition among older AA and Latinos. Results highlighted the underrepresentation of these populations in trials aimed at improving cognitive function. Only eight NPI studies have reported outcomes among these vulnerable populations. Interventions included dietary supplementation, cognitive training, and exercise in conjunction with group educational sessions. All were effective to some extent. Most studies were also feasible, with adherence rates of 76% among AA and 66%−85% among Latinos. Cognitive training interventions improved memory, executive function, reasoning, visuospatial function, and processing speed among AA. Exercise interventions improved cognition among Latinos. Cognitive training interventions encountered challenges in terms of sample size and generalizability, which is congruent with previous aging related research.

Despite the disproportionate risk of dementia in these populations, few NPI have attempted to reduce that risk among AA and Latinos. The Latino-focused PA interventions were both culturally and linguistically tailored and demonstrated acceptability, feasibility, and efficacy in improving cognitive performance. This finding is consistent with previous literature focused on increasing PA to reduce chronic health conditions and shows that culturally tailored PA interventions for Latinos can effectively enhance health outcomes (Bopp, Fallon, and Marquez 2011).

For AA, NPI were cognitive training-focused and did not incorporate cultural tailoring. Culturally adapted lifestyle interventions among AA older adults have been shown to be effective in increasing PA and have been shown to be feasible to implement within the AA community (Gretebeck et al. 2018). Additionally, faith-based lifestyle interventions targeted to reduce chronic disease risks among AA have consistently shown to be effective for behavioral change (Sattin et al. 2016). Future research should explore how culturally tailored PA interventions with cognitive training can impact cognition among older AA adults, and several registered clinical trials are currently testing culturally innovative means to promote physical activity in the older adult AA community. It may also be valuable to re-asses existing large trials with sizeable minority participant pools, to evaluate if these not tailored interventions provide the effectiveness and adherence across diverse populations.

Socioeconomic status is intimately intertwined with race, sex, and ethnicity in the U.S. The resulting interplay can have both positive and negative lifetime physiological outcomes such as cognitive impairment (Glymour and Manly 2008). Therefore, it is imperative that future studies include more socioeconomically diverse AA and Latino participants, and capture socioeconomic indicators such as income, education, and local deprivation (Health 2015) to appropriately design future studies, and study various social conditions across ones life course.

Only one of the studies incorporated a nutrition component, which has consistently been shown to impact brain function in previous research (Sofi et al. 2010, Lourida et al. 2013). Further, research has noted that unhealthy eating habits disproportionately impact minorities, resulting in chronic diseases and conditions such as obesity and hypertension, which are associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment (Satia 2009, Gottesman et al. 2017). More nutrition-based intervention studies for underrepresented minorities are needed to provide evidence-based guidance for physical and cognitive health outcomes in the Latino and African American communities in the U.S. (National Academies of Sciences 2017).

Some studies noted within the eligibility criteria that individuals were excluded who had diseases such as a stroke (Marquez et al. 2017, Zahodne et al. 2015). Since stroke rates are highest among AA, and the rate of strokes among Latino has increased since 2013, it is important to establish culturally appropriate inclusion/exclusion criteria to better reach and enhance diverse enrollment for AA and Latinos in NPI.

All studies were conducted in urban areas and in various settings such as community and senior centers, suggesting there is lack of NPI research being conducted in rural areas. African Americans and Latinos are growing in numbers in rural areas of the U.S and racial/ethnic minorities now make up 22% of the rural population (Cromartie 2018). Latinos are now the fastest growing population in the rural U.S. (9%) with a growth rate of 2% per year since 2012 (Cromartie 2018). Rural Americans are at a higher risk of dementia due to limited healthy lifestyle resources and access to preventative care (Blocker et al. 2020). Therefore, future research should examine tailored approach NPIs to reduce the risk of dementia among this underserved population, (Service 2005)as these individuals might have unique needs.

Because AA and Latinos do not represent a homogeneous group, ]studies should explore NPI on cognitive function in diverse groups (i.e. African Caribbean and Puerto Rican). Examining diverse subgroups of populations of African and Latino descent will lead to a richer understanding of how culture and acculturation influences health behaviors in these groups. Further, exploring diverse groups can help shape the customization of culturally sensitive NPI designed to improve cognitive function.

Improved cognition performance as a result of cognitive training in studies assessed in this scoping review align with other NPI that have focused on cognitive training through PC-based training and PC-based training combined with PA. Computer-based cognitive training has been shown to stimulate immediate and delayed memory, and language in older adults (Miller et al. 2013). PC game-based cognitive training has resulted in improvements of attention among older adults (Whitlock, McLaughlin, and Allaire 2012). Since PC based cognitive training has shown promise, future research should explore how culturally tailored PC based training impacts cognition among AA and Latinos.

Similar to the Zahonde et al. (2015) study in this scoping review which found that combining cognitive training with PA improved memory, reasoning, and speed among AA; PC-based training combined with PA has been shown to improve cognition among older adults of other racial backgrounds. Researchers conducted a randomized virtual reality-enhanced cycling PA intervention among older adults and found that the cyber-cycling group achieved better cognition compared to individuals in the traditional cycling group (Anderson-Hanley et al. 2012). Future research should explore PA in combination with PC-based cognitive training intervention studies aimed at minorities to better understand its impact on change in cognitive domains. To gain a more wholistic view of inclusion of AA and Latino participants in NPI clinical trials to improve cognition, future studies should examine the percentage of AA and Latino participants included in all trials conducted in the U.S.

This scoping review had several strengths including use of a comprehensive, systematic methodology searching in electronic databases and grey literature. Despite findings from this review, there are limitations that need to be taken into consideration when interpreting findings. We excluded studies measuring dementia incidence rather than cognition. However, the probability of a study that assessed dementia incidence as an outcome among minorities is low given the length of the interventions in our findings. To optimize the search, we only included studies involving AA and Latinos in the United States. Race and ethnicity are social constructs, with consequences and opportunities that are often best interpreted within defined geographic and socio-political boundaries. Limiting our search to the U.S. allowed us to focus on underrepresented minorities that regularly experience significant disparity in the US health care and research systems, especially regarding cognitive outcomes and dementia. Our results are not necessarily representative of related populations (e.g. individuals in Africa or Latin America), who might differ in contextual, psychological, social, and physiological characteristics.

Given the small number of manuscripts retrieved, it was not feasible to conduct a meta-analysis of the findings.

Conclusion

AA and Latino adults and older adults are underrepresented in NPI for cognitive health. The results of the eight NPI reviewed in this study hold promise in promoting cognitive improvement among AA and Latinos. In this review, we have summarized the effectiveness of NPI studies among AA and Latinos. Effective interventions focused on cognitive training and diet for AA and PA combined with group educational sessions for Latinos. Culturally-driven interventions were effective in improving cognition. Given the increase in racial/ethnic diverse groups in the United States and their underrepresentation in clinical studies, there is a need to expand culturally appropriate NPI to reduce health disparities and to enhance cognition among older AA and Latinos.

Acknowledgments

Funding details

This work was supported by the National Institute of Aging grant number P30AG035982.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

- Anderson-Hanley C, Arciero PJ, Brickman AM, Nimon JP, Okuma N, Westen SC, Merz ME, Pence BD, Woods JA, Kramer AF, and Zimmerman EA. 2012. “Exergaming and older adult cognition: a cluster randomized clinical trial.” Am J Prev Med 42 (2):109–19. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association, Alzheimer’s. 2017. “2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures.” Alzheimer Dementia 13 (4):325–373. [Google Scholar]

- Babulal GM, Williams MM, Stout SH, and Roe CM. 2018. “Driving Outcomes among Older Adults: A Systematic Review on Racial and Ethnic Differences over 20 Years.” Geriatrics (Basel) 3 (1). doi: 10.3390/geriatrics3010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett J, Bahar-Fuchs A, Cherbuin N, Herath P, and Anstey K. 2015. “Intervention to prevent cognitive decline and dementia in adults without cognitive impairment: A systematic review.” J Prevent Alzheimers Dis 2:38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blocker EM, Fry AC, Luebbers PE, Burns JM, Perales-Puchalt J, Hansen DM, and Vidoni ED. 2020. “Promoting Alzheimer’s Risk-Reduction through Community-Based Lifestyle Education and Exercise in Rural America: A Pilot Intervention.” Kans J Med 13:179–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp Melissa, Fallon Elizabeth A., and Marquez David X.. 2011. “A Faith-Based Physical Activity Intervention for Latinos: Outcomes and Lessons.” Am J Health Promot 25 (3):168–171. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090413-ARB-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchard EG, Ziv E, Coyle N, Gomez SL, Tang H, Karter AJ, Mountain JL, Perez-Stable EJ, Sheppard D, and Risch N. 2003. “The importance of race and ethnic background in biomedical research and clinical practice.” N Engl J Med 348 (12):1170–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb025007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MC, Saczynski JS, Rebok GW, Seeman T, Glass TA, McGill S, Tielsch J, Frick KD, Hill J, and Fried LP. 2008. “Exploring the effects of an “everyday” activity program on executive function and memory in older adults: Experience Corps.” Gerontologist 48 (6):793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SL, and Ortman JM. 2014. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. U.S. Census Bureau. Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun Heather L, Levac Danielle, O’Brien Kelly K, Straus Sharon, Tricco Andrea C, Perrier Laure, Kastner Monika, and Moher David. 2014. “Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting.” J Clin Epidemiol 67 (12):1291–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromartie J 2018. Rural America At a Glance. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Washington, D.C.: Economic Research Service. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, Basak C, Szabo A, Chaddock L, Kim JS, Heo S, Alves H, White SM, Wojcicki TR, Mailey E, Vieira VJ, Martin SA, Pence BD, Woods JA, McAuley E, and Kramer AF. 2011. “Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 (7):3017–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015950108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faison WE, Schultz SK, Aerssens J, Alvidrez J, Anand R, Farrer LA, Jarvik L, Manly J, McRae T, Murphy GM Jr., Olin JT, Regier D, Sano M, and Mintzer JE. 2007. “Potential ethnic modifiers in the assessment and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: challenges for the future.” Int Psychogeriatr 19 (3):539–58. doi: 10.1017/S104161020700511X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Nuru-Jeter A, Minkler M, and Guralnik JM. 2009. “Black-White disparities in disability among older Americans: further untangling the role of race and socioeconomic status.” J Aging Health 21 (5):677–98. doi: 10.1177/0898264309338296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glymour M Maria, and Manly Jennifer J. 2008. “Lifecourse social conditions and racial and ethnic patterns of cognitive aging.” Neuropsychol Rev 18 (3):223–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman RF, Albert MS, Alonso A, Coker LH, Coresh J, Davis SM, Deal JA, McKhann GM, Mosley TH, Sharrett AR, Schneider ALC, Windham BG, Wruck LM, and Knopman DS. 2017. “Associations Between Midlife Vascular Risk Factors and 25-Year Incident Dementia in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Cohort.” JAMA Neurol 74 (10):1246–1254. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gretebeck K, Green-Harris G, Ward E, Houston S, Skora T, Brown M, Means J, and Gretebeck R. 2018. “Cultural Adaption of a Lifestyle Exercise Interventio nfor Older African Americans: Research Results.” Innovation in Aging 2 (suppl_1):18–18. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igy023.065 %J Innovation in Aging. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- University of Wisconsin School of Medicne and Public Health. 2015. “Area Deprivation Index v2.0.” https://www.neighborhoodatlas.medicine.wisc.edu/.

- Hernandez R, Cheung E, Liao M, Boughton SW, Tito LG, and Sarkisian C. 2018. “The Association Between Depressive Symptoms and Cognitive Functioning in Older Hispanic/Latino Adults Enrolled in an Exercise Intervention: Results From the “ inverted exclamation markCaminemos!” Study.” J Aging Health 30 (6):843–862. doi: 10.1177/0898264317696776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe JB, Smith DM, Ball K, Tennstedt SL, Marsiske M, Willis SL, Rebok GW, Morris JN, Helmers KF, Leveck MD, and Kleinman K. 2001. “ACTIVE: a cognitive intervention trial to promote independence in older adults.” Control Clin Trials 22 (4):453–79. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(01)00139-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer AF, Hahn S, Cohen NJ, Banich MT, McAuley E, Harrison CR, Chason J, Vakil E, Bardell L, Boileau RA, and Colcombe A. 1999. “Ageing, fitness and neurocognitive function.” Nature 400 (6743):418–9. doi: 10.1038/22682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Alan D, Mathers Colin D, Ezzati Majid, Jamison Dean T, and Murray Christopher JL. 2006. “Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data.” Lancet 367 (9524):1747–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourida I, Soni M, Thompson-Coon J, Purandare N, Lang IA, Ukoumunne OC, and Llewellyn DJ. 2013. “Mediterranean diet, cognitive function, and dementia: a systematic review.” Epidemiol 24 (4):479–89. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182944410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maass A, Duzel S, Goerke M, Becke A, Sobieray U, Neumann K, Lovden M, Lindenberger U, Backman L, Braun-Dullaeus R, Ahrens D, Heinze HJ, Muller NG, and Duzel E. 2015. “Vascular hippocampal plasticity after aerobic exercise in older adults.” Mol Psychiatry 20 (5):585–93. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez DX, Bustamante EE, Aguinaga S, and Hernandez R. 2015. “BAILAMOS: Development, Pilot Testing, and Future Directions of a Latin Dance Program for Older Latinos.” Health Educ Behav 42 (5):604–10. doi: 10.1177/1090198114543006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez DX, Wilson R, Aguinaga S, Vasquez P, Fogg L, Yang Z, Wilbur J, Hughes S, and Spanbauer C. 2017. “Regular Latin Dancing and Health Education May Improve Cognition of Late Middle-Aged and Older Latinos.” J Aging Phys Act 25 (3):482–489. doi: 10.1123/japa.2016-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Xu W, Gaglioti AH, Holt JB, Croft JB, Mack D, and McGuire LC. 2019. “Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015–2060) in adults aged >/=65 years.” Alzheimers Dement 15 (1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall GJ Jr., Becker H, Pituch K, Acee TW, Vaughan PW, and Delville CL. 2010. “Differential benefits of memory training for minority older adults in the SeniorWISE study.” Gerontologist 50 (5):632–45. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KJ, Dye RV, Kim J, Jennings JL, O’Toole E, Wong J, and Siddarth P. 2013. “Effect of a computerized brain exercise program on cognitive performance in older adults.” Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 21 (7):655–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, Sacks FM, Bennett DA, and Aggarwal NT. 2015. “MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease.” Alzheimers Dement 11 (9):1007–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine. 2017. Preventing Cognitive Decline and Dementia: A Way Forward: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A, Levalahti E, Ahtiluoto S, Antikainen R, Backman L, Hanninen T, Jula A, Laatikainen T, Lindstrom J, Mangialasche F, Paajanen T, Pajala S, Peltonen M, Rauramaa R, Stigsdotter-Neely A, Strandberg T, Tuomilehto J, Soininen H, and Kivipelto M. 2015. “A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial.” Lancet 385 (9984):2255–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu Jeanette E., Islam Shahidul, Katumuluwa Subhashini S., Stolberg Alexandra R., Usera Gianina L., Anwarullah Ayesha A., Shieh Albert, Dhaliwal Ruban, Ragolia Louis, Mikhail Mageda B., and Aloia John F.. 2019. “Cognition and Vitamin D in Older African-American Women– Physical performance and Osteoporosis prevention with vitamin D in older African Americans Trial and Dementia.” J Am Geriatr Soc 67 (1):81–86. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perales-Puchalt J, Gauthreaux K, Shaw A, McGee JL, Teylan MA, Chan KCG, Rascovsky K, Kukull WA, and Vidoni ED. 2020. “Risk of mild cognitive impairment among older adults in the United States by ethnoracial group.” Int Psychogeriatr:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219002175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piedra LM, Andrade FCD, Hernandez R, Boughton SW, Trejo L, and Sarkisian CA. 2017. “The Influence of Exercise on Cognitive Function in Older Hispanic/Latino Adults: Results From the “ inverted exclamation markCaminemos!” Study.” Gerontologist 57 (6):1072–1083. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev PS, Blacker D, Blazer DG, Ganguli M, Jeste DV, Paulsen JS, and Petersen RC. 2014. “Classifying neurocognitive disorders: the DSM-5 approach.” Nat Rev Neurol 10 (11):634–42. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallim Adnaan Bin, Sayampanathan Andrew Arjun, Cuttilan Amit, and Ho Roger Chun-Man. 2015. “Prevalence of mental health disorders among caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease.” J Am Med Dir Assoc 16 (12):1034–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satia Jessie A. 2009. “Diet-related disparities: understanding the problem and accelerating solutions.” J Am Dietetic Assoc 109 (4):610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattin RW, Williams LB, Dias J, Garvin JT, Marion L, Joshua TV, Kriska A, Kramer MK, and Narayan KM. 2016. “Community Trial of a Faith-Based Lifestyle Intervention to Prevent Diabetes Among African-Americans.” J Community Health 41 (1):87–96. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0071-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Service, United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research. 2005. “Population Change and Geography.” https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/44570/29568_eib8full.pdf?v=41305.

- Sofi F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, and Casini A. 2010. “Accruing evidence on benefits of adherence to the Mediterranean diet on health: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis.” Am J Clin Nutr 92 (5):1189–96. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidoni ED, Johnson DK, Morris JK, Van Sciver A, Greer CS, Billinger SA, Donnelly JE, and Burns JM. 2015. “Dose-Response of Aerobic Exercise on Cognition: A Community-Based, Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial.” PLoS One 10 (7):e0131647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JL, Ryan L, Silverberg N, Cahan V, and Bernard MA. 2014. “Obstacles and opportunities in Alzheimer’s clinical trial recruitment.” Health Aff 33 (4):574–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock Laura A., McLaughlin Anne Collins, and Allaire Jason C.. 2012. “Individual differences in response to cognitive training: Using a multi-modal, attentionally demanding game-based intervention for older adults.” Computers Human Behavior 28 (4):1091–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.01.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2012. Dementia: a public health priority: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Zahodne LB, Meyer OL, Choi E, Thomas ML, Willis SL, Marsiske M, Gross AL, Rebok GW, and Parisi JM. 2015. “External locus of control contributes to racial disparities in memory and reasoning training gains in ACTIVE.” Psychol Aging 30 (3):561–72. doi: 10.1037/pag0000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Elashoff D, Kremen S, Teng E, Karlawish J, and Grill JD. 2017. “African Americans are less likely to enroll in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials.” Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 3 (1):57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]