Abstract

A novel coumarin-based molecule, designed as a fluorescent surrogate of a thiacetazone-derived antitubercular agent, was quickly and easily synthesized from readily available starting materials. This small molecule, coined as Coum-TAC, exhibited a combination of appropriate physicochemical and biological properties, including resistance towards hydrolysis and excellent antitubercular efficiency similar to that of well-known thiacetazone derivatives, as well as efficient covalent labeling of HadA, a relevant therapeutic target to combat Mycobacterium tuberculosis. More remarkably, Coum-TAC was successfully implemented as an imaging probe that is capable of labeling Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a selective manner, with an enrichment at the level of the poles, thus giving for the first time relevant insights about the polar localization of HadA in the mycobacteria.

Keywords: thiacetazone, coumarin, HadA, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, fluorescence

Graphical Abstract

RESUME

In this work is reported the rational design, synthesis, antitubercular evaluation and imaging potential of a small and easy-to-prepare molecule playing the dual role of i) efficient inhibitor of a relevant therapeutic target, namely HadA, to combat Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and ii) fluorescent probe to selectively label M.tb and get insights for the first time on the localization of HadA in the mycobacteria.

INTRODUCTION

Despite being one of the ancient and deadliest diseases affecting mankind, tuberculosis (TB) still is today a major health burden by being the leading cause of mortality due to an infectious disease worldwide.1 In actual fact, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.tb), the prime causative agent of TB, is nowadays infecting more than one-quarter of the world’s population, with no fewer than 10 million new cases and 1.5 million deaths per year. The main obstacle to TB control is the emergence of M.tb strains that exhibit resistance to the frontline anti-TB drugs such as isoniazid (INH), rifampicin (RIF), ethambutol (EMB) and pyrazinamide (PYR).1,2 As these M.tb drug-resistant strains are spreading further at an alarming rate, there is an urgent need for the development of novel effective drugs and/or therapeutic targets to combat this scourge.

Currently, most of efficient anti-TB strategies take advantage of the unique cell wall composition of M.tb which is particularly rich in lipids. It is indeed well established that mycobacteria’s ability to survive is directly dependent on the integrity of its outer membrane called mycomembrane.3 The unique mycomembrane composition is due to the presence of specific fatty acids, namely mycolic acids (MAs), as major lipid components which are synthesized by two types of fatty acid-synthase system (FAS), i.e. FAS-I and FAS-II (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The FAS-II pathway in M.tb with enzymes in bold.

Among the FAS-II, four enzymes operate in tandem in each cycle of elongation. In particular, the third step of the fatty acid elongation is promoted by β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase complex (HadABC) via dehydration of β-hydroxyacyl-ACP to trans-2-enoyl-ACP,4 HadA and HadC being the substrate binding subunits and HadB the catalytic subunit. Of significance is that the HadABC knock-out mutant in M.tb proved to be not viable3 and further studies showed that HadA and HadB are essential for cell viability but not HadC5.

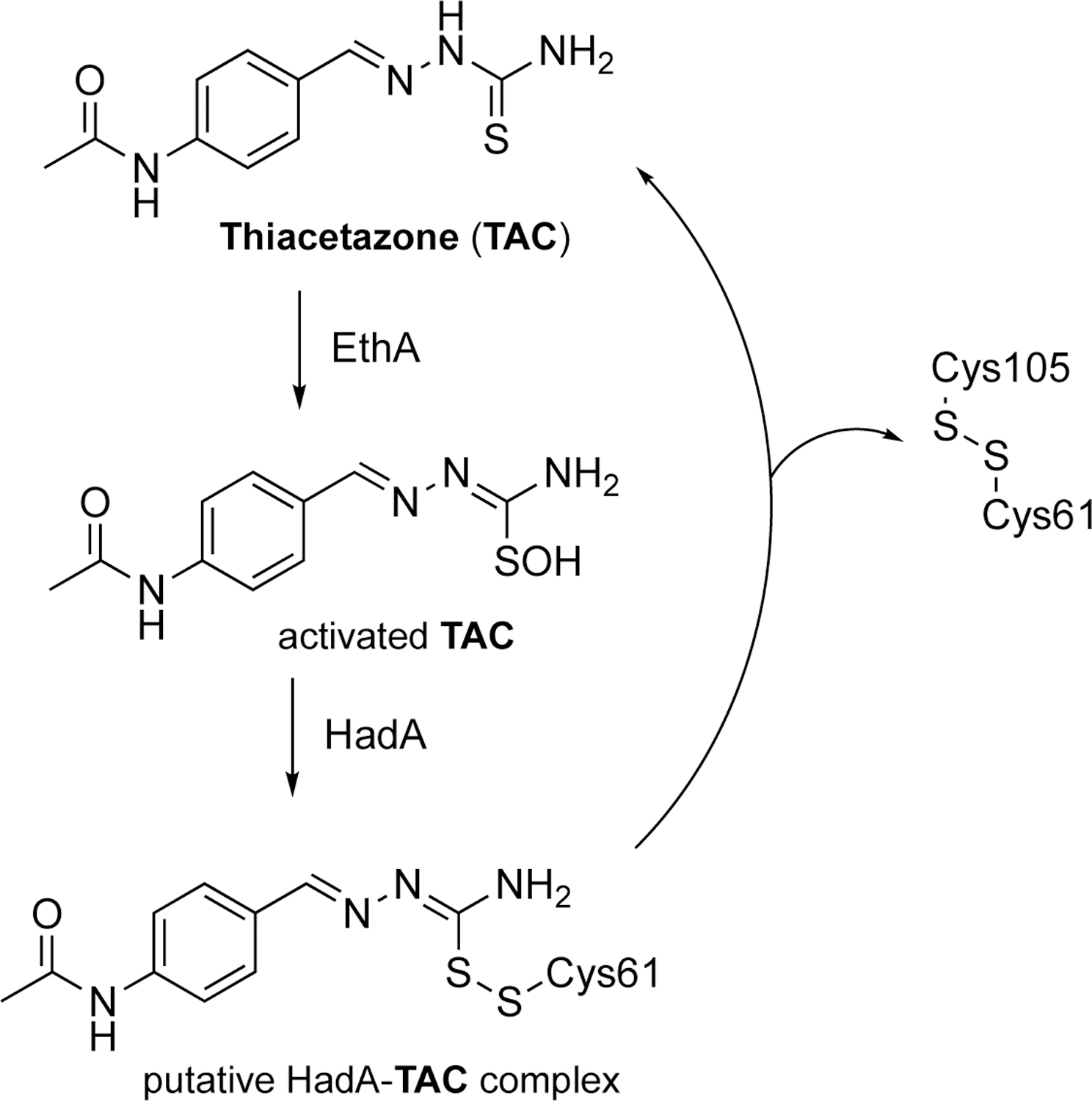

Thus, these results make Had proteins, especially HadA and HadB, relevant therapeutic targets to combat M.tb. Among the existing compounds targeting Had proteins, thiacetazone (TAC) is an anti-TB drug that had been widely used in combination with the prodrug isoniazid (INH) in South America and Africa (Scheme 1). TAC is a prodrug that has to be activated by the mycobacterial monoxygenase EthA that is also able to activate the two other well-known anti-TB drugs ethionamide (ETH) and isoxyl (ISO).6,7,8,9 Activated TAC and ISO have been shown to inhibit the dehydration step of the FAS-II system pathway, while ETH after activation acts as an inhibitor of enoyl-ACP reductase InhA.10 Biochemical and proteomic evidences established that TAC specifically and covalently reacts with a cysteine residue (i.e., Cys61) of HadA subunit of the dehydratase (Scheme 1).11 Unfortunately, attempts to characterize the HadAWT-drug complexes have failed so far due to the presence of Cys105 able to displace the drug to afford a disulfide bridge Cys61-Cys105, possibly formed either in the mycobacteria or during the isolation of the HadA-drug complexes.

Scheme 1.

Thiacetazone (TAC): structure and suggested mechanism of HadA inactivation.

In that context, there is an actual need to develop effective tools for increasing knowledge about HadA due to its relevance as therapeutic target. The localization of HadA in the mycobacteria would be a first step forward. Despite intensive efforts to localize proteins from the FAS-II system in the mycobacteria, the localization of HadA is indeed still unknown, unlike other FAS-II proteins, including MabA, InhA, KasA and KasB, which were localized in the same region at the poles (Figure 1).12 To achieve this goal, we intend to provide a novel chemical tool enabling the imaging and the identification of HadA in the mycobacteria.

Herein, we precisely report a structurally-simple and easy-to-prepare probe able to play a dual role of covalent inhibition and imaging. The present work thus details the rational design and straightforward synthesis of the envisaged probe, as well as the evaluation of its potential not only as an efficient covalent inhibitor of HadA and MAs biosynthesis in mycobacteria, but also as a useful fluorescent probe in M.tb.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design and synthesis of Coum-TAC.

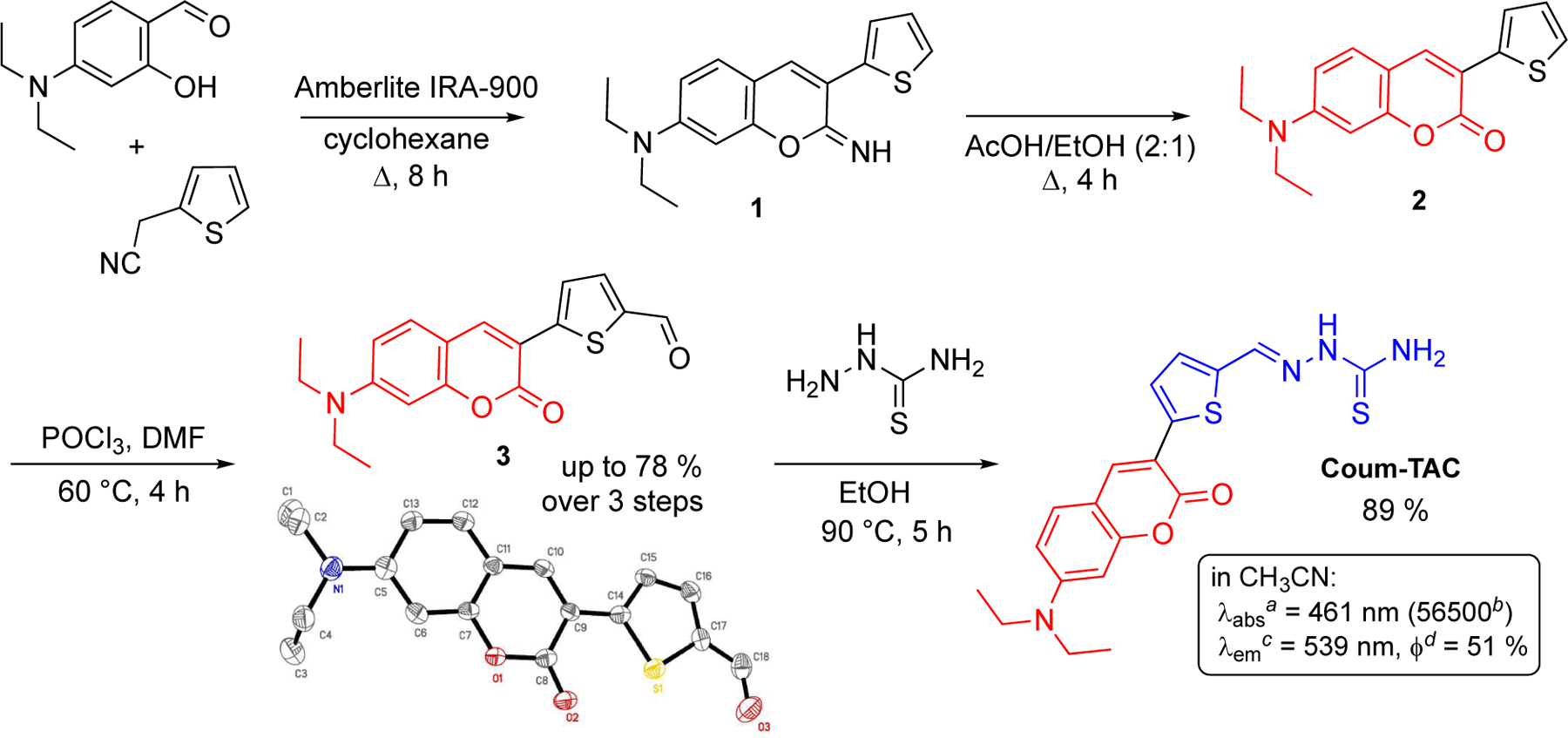

As depicted in Figure 2, the design of the envisaged probe (i.e., Coum-TAC) relied on the construction of a covalent conjugate of a known anti-TB agent with a fluorescent moiety (Figure 2). To find a judicious anti-TB agent, we focused our attention on already reported TAC analogues, bearing thus the thiocarbazone group prone to target HadA protein (Scheme 2). In fact, various TAC analogues have been reported in the literature as efficient anti-TB agents.12–14 While most of the reported analogues feature distinct substitution patterns on the aryl ring of TAC,13,14 some heteroaryl (i.e., thiophenyl, pyridinyl, quinoleinyl …) derivatives were also found to exhibit good to excellent activities against M.tb15. Regarding these data, we selected the thiophenyl-based TAC analogue (right hand blue structure in Figure 2) to be conjugated with a fluorescent moiety. This choice was motivated not only by the excellent anti-TB activity of this analogue (i.e., MIC (H37Rv) < 1 µg/mL), but also by its ease of chemical incorporation in the targeted Coum-TAC probe. As fluorescent moiety, our choice went to the coumarin scaffold, a popular heterocyclic chromophore responsible for the fluorescence of numerous compounds of imaging relevance.16 More particularly, 7-(N,N)-diethylaminocoumarin, commonly referred to as coumarin 466 (left hand red structure in Figure 2), was selected due to its well-known photophysical properties.17 Of note, the coumarin skeleton is also a privileged scaffold in life sciences due its presence in numerous biologically-relevant natural or synthetic products.18 The range of biological activities of coumarins is indeed quite broad, coumarin-based compounds having been reported in the literature as antitumor,19 antidepressant,20 anti-Alzheimer,21 anti-inflammatory,22 antioxidant,23 anti-HIV24 but also as anti-TB agents25.

Figure 2.

Coum-TAC probe as a covalent conjugate of an anti-TB agent (in blue, see ref 14 for details) with a fluorescent moiety (in red).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis and photophysical properties of Coum-TAC. a Maximum absorption wavelength in nm. b Molar extinction coefficient in M−1 cm−1. c Maximum emission wavelength in nm. d Fluorescence quantum yield at 461 nm.

We next planned the synthesis of Coum-TAC which was successfully achieved in four steps from 4-(N,N)-diethylaminosalicylaldehyde and 2-thiopheneacetonitrile as commercially available starting materials (Scheme 2). The two first steps allowed the construction of the required coumarin moiety via base-catalyzed cyclocondensation of 4-(N,N)-diethylaminosalicylaldehyde with 2-thiopheneacetonitrile followed by acid-mediated hydrolysis of the iminocoumarin intermediate 1. The so-formed coumarin 2 equipped with a thiophenyl residue was next subjected to Vilsmeier-Haack conditions to furnish formylated coumarin 3. Coum-TAC was finally obtained by condensation between 3 and thiosemicarbazide in refluxing ethanol. Noteworthy are the efficient, straightforward and easy-to-synthesize features of this four-steps sequence without the need for any chromatographic purification step.

Stability and photophysical evaluation of Coum-TAC.

Additional properties of Coum-TAC were required before moving forward with its biological profile.

First, we evaluated the stability of Coum-TAC under aqueous conditions in order to confirm the robustness of its hydrazone function towards hydrolysis. This data of robustness will provide relevant information about the stability of Coum-TAC under the conditions applied thereafter in the course of its biological evaluation. Hence, its stability was evaluated for 21 days at 37 °C in a mixture CH3CN/H2O 8:2 and monitored by LC/MS (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). Under such conditions, Coum-TAC exhibited sufficient resistance towards hydrolysis (less than 5 % decrease over the investigated period), thus revealing an adequate stability profile of Coum-TAC for its biological evaluation, which is to follow.

For imaging purposes, we also evaluated photophysical properties of Coum-TAC by means of UV-vis and fluorescence spectroscopies. Shifting from coumarin 466 to Coum-TAC led, as expected, to a substantial red shift at the apex of both absorption and emission peaks (maximum wavelengths increase of 80 nm and 91 nm in acetonitrile, respectively). Coum-TAC indeed exhibits a strong and sharp absorption band at 461 nm and a strong emission band at 539 nm, thus revealing a large Stokes shift (ie. 78 nm). These data make Coum-TAC a fluorescent candidate suited to imaging experiments detailed later in this study.

Evaluation of the anti-TB activity of Coum-TAC.

The antitubercular activity of Coum-TAC was determined against M.tb H37Rv (entry 1, Table 1), showing a MIC of 0.5 µg/mL very similar to MIC of various TAC analogues found in the literature12,13 and more specifically to that of the thiophenyl-based TAC analogue selected as anti-TB moiety of Coum-TAC (i.e., with a reported MIC (H37Rv) of 0.8 µg/mL) (Figure 2)14. As a control, no antimycobacterial effect was observed for the synthetic precursor 3 of Coum-TAC, thus revealing the crucial effect of the thiocarbazone group. MIC of Coum-TAC was also determined for M. smegmatis mc2155 strain. As expected,26 the MIC in M. smegmatis is > 256 µg/mL, thus revealing that M. smegmatis strain is resistant to Coum-TAC as for TAC. As a control, INH presents a MIC in M. smegmatis of 16 µg/mL. To investigate whether Coum-TAC has a bacteriostatic or cidal activity against M.tb H37Rv, kill kinetics were performed comparing the activity of Coum-TAC with that of TAC. M.tb cultures were exposed at MIC concentration (0.5 and 1 µg/ml, respectively) and 10-fold MIC values, and viability was measured. TAC has a bacteriostatic effect on M.tb cultures, as reported literature,7 and cultures treated with Coum-TAC also showed a similar bacteriostatic activity (Figure S2 in the Supporting Information).

Table 1.

Activity of Coum-TAC against M.tb H37Rv and several drug-resistant strains

| Entry | M.tb strains | MIC (µg/mL) Coum-TAC |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WT H37Rv | 0.5 | |

| 2 | 53.3 (Rv2466c, W28S) | 0.5 | 27 |

| 3 | NTB1 (DprE1, G387S) | 0.5 | 28 |

| 4 | DR1 (MmpL3, V681I) | 0.5 | 29 |

| 5 | Ty1 (Rv3405c, c190t) | 0.5 | 30 |

| 6 | 88.1 (CoaA, Q207R) | 0.5 | 31 |

| 7 | 88.7 (pyrG, V186G) | 0.5 | 32 |

| 8 | 81.10 (EthA, Δ1109–37) | >20 | 26 |

| 9 | CI1a–c | >20 | 33 |

| 10 | CI2a–c | >20 | 32 |

Drug resistance profiles of M.tb clinical isolates (CI): CI1 resistant to STR, INH, RIF, EMB, ETH / CI2 resistant to STR, INH, RIF, EMB, ETH, PYR, capreomycin).

With STR: streptomycin, INH: isoniazid, RIF: rifampicin, EMB: ethambutol, ETH: ethionamide, PYR: pyrazinamide.

For structures of INH, RIF, EMB and ETH, see Figure 1.

Consequently, in order to study the mechanism of action of Coum-TAC, a panel of nine M.tb mutants already available and harboring different mutations in genes encoding for drug targets (NTB1, DR1, 88.1, 88.7), activators (53.3 and 81.10) and inactivator (Ty1) was used. More specifically: i) 53.3 mutant harbours a mutation in Rv2466c coding for the activator of the TP053 thienopyrimidine (entry 2, Table 1),26 ii) NTB1 presents a mutation in dprE1, coding for the benzothiazinone target (entry 3),27 iii) DR1 mutant harbours a mutation in mmpL3, which codes for the cellular target of BM212 and other compounds (entry 4),28 iv) TY1 has a mutation in Rv3405c coding for the repressor of Rv3406, an enzyme inactivating the Ty38c carboxyquinoxaline (entry 5),29 v) 88.1 mutant harbours a mutation in coaA coding for PanK which is the target of thiphenecarboxamides (entry 6),30 vi) 88.7 presents a mutation in pyrG coding for the CTP synthetase which is the second target of thiophenecarboxamides (entry 7),31 vii) 81.10 compound has a mutation in ethA coding for the activator of TAC, ethionamide (ETH) and isoxyl (ISO) (entry 8)31. Finally, Coum-TAC was evaluated for its activity against two M.tb multi-drug resistant clinical isolates CI1 and CI2 (entries 9–10).32

As expected, 81.10 mutant (mutated in ethA gene) and the two clinical strains, i.e. CI1 and CI2 (also resistant to ETH), were resistant to Coum-TAC, suggesting that this compound could be activated by EthA similarly to TAC (entries 8–10). All the other mutants are sensitive to Coum-TAC, thus highlighting that their mutations are not linked to the mechanism of action/resistance of this compound.

Activation of Coum-TAC by EthA.

To further confirm the role of EthA in Coum-TAC activation, the ability of the enzyme to metabolize the compound was investigated. Using a direct spectrophotometric assay, which measures the decrease in absorbance of the NADPH cofactor during the catalysis, we performed a steady state kinetic analysis vs both TAC and Coum-TAC (Figure 3), demonstrating that Coum-TAC is effectively a substrate of EthA. The enzyme showed kinetic parameters for TAC (kcat = 4.83 ± 0.7 min−1; Km = 0.153 ± 0.011 mM) in accordance with those previously reported.6 The kcat value for Coum-TAC (0.72 ± 0.17 min−1), was lower than the one for TAC, but the affinity was about 10 fold higher with a Km of 0.016 ± 0.002 mM. Thus, EthA shows a similar specificity towards both substrates with kcat/Km of 45.0 ± 6.2 min−1 mM−1 for Coum-TAC vs 31.5 ± 7.6 min−1 mM−1 for TAC.

Figure 3.

Steady-state kinetics of EthA as a function of Coum-TAC as a substrate. Data are mean ± SD of at least three independent determinations. In the inset the comparison between the steady-state kinetics of TAC (red curve) vs Coum-TAC (black curve) is reported.

Inhibition of the synthesis of mycolic acids in M.tb H37Ra by Coum-TAC.

To investigate whether Coum-TAC inhibits the synthesis of mycolic acids similarly to TAC, 14C acetate metabolic labeling of M.tb H37Ra treated with Coum-TAC or TAC was performed. When the cells of M.tb H37Ra reached OD (600 nm) ~ 0.27, Coum-TAC or TAC were added in final concentrations 0.01, 0.05, 0.1 and 0.25 µg/ml. After 24 h of treatment, 14C label was added followed by further 24 h cultivation. Lipids and mycolic acids isolated from the 14C labeled cells were analyzed by TLC. While Coum-TAC did not affect the synthesis of any of major phospholipids, it completely abolished the synthesis of trehalose monomycolates (TMM) and trehalose dimycolates (TDM) in tested conditions (Figure 4A). Correlating with this observation, Coum-TAC did not inhibit the synthesis of standard fatty acids, however it completely blocked the synthesis of all forms of mycolic acids (Figure 4B). Coum-TAC thereby exhibits the same inhibition effect as TAC.

Figure 4.

TLC analysis of (A) lipids and (B) methyl esters of fatty (FAME) and mycolic (MAME) acids isolated from 14C labeled M.tb H37Ra cells treated with Coum-TAC or TAC. Lipids were separated in chloroform/methanol/water (20:4:0.5) and detected by autoradiography. Different forms of methyl esters were separated in n-hexane/ethyl acetate (95:5; 3 runs) and detected by autoradiography (with TDM: trehalose dimycolates; TMM: trehalose monomycolates; PE: phosphatidylethanolamine; CL: cardiolipin; alpha-, methoxy- and keto- refer to the forms of MAMEs).

Resistance against Coum-TAC resulting from overproduction of HadABC in M.tb.

To confirm that Coum-TAC targets the dehydratase in FASII system, the HadABC protein complex was overproduced in M.tb H37Ra using pVV16-hadABC construct34. The analysis of MIC of Coum-TAC and TAC against i) control M.tb H37Ra strain carrying empty plasmid pVV16 and ii) against M.tb H37Ra strain overproducing HadABC revealed dramatically increased MIC values of both compounds due to overproduction of HadABC reaffirming the same mode of action of TAC and Coum-TAC in mycobacterial cells (Table 2). As expected, no difference in MIC of Coum-TAC was observed after overproduction of another protein of FAS-II complex, enoyl-acyl-ACP reductase InhA.

Table 2.

Activity of Coum-TAC and TAC against different M.tb H37Ra strains

| Entry | M.tb strains | MIC (µg/mL) Coum-TAC |

MIC (µg/mL) TAC |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | pVV16 | 0.01–0.02 | 0.02 |

| 2 | pVV166-hadABC | >50a | >50a |

| 3 | pMV261 | 0.01–0.02 | 0.02 |

| 4 | pMV261-inhA | 0.01–0.02 | 0.02 |

Higher concentrations were not tested due to solubility issues.

Stimulation of in vitro HadA dimerization by TAC and Coum-TAC.

In a previous work, it was shown that in mycobacterial cells, TAC covalently binds to Cys61 of HadA protein.10 We have therefore investigated, whether Coum-TAC exerts the same behavior. We performed in vitro reactions containing isolated proteins HadA and EthA, NADPH and Coum-TAC. Alternatively, the reaction mixtures contained TAC to compare the effects of both compounds. After 1h incubation of the reactions at 37 °C, the proteins were analyzed on SDS-PAGE in non-reducing and reducing conditions. Interestingly, the addition of both compounds, TAC, as well as Coum-TAC, led to the formation of HadA dimer that depended on the presence of EthA activator (Figure 5). The addition of the reducing agent, 2-mercaptoethanol, to these samples resulted in disintegration of dimer and appearance of HadA monomer. It was suggested, that the presence of the second Cys residue (Cys105) in HadA may cause the HadA-drug adducts unstable, causing the formation of intramolecular Cys61-Cys105 disulfide bond in the protein (Scheme 1).11 We suggest that in our cell-free system containing isolated HadA protein in the presence of activated drugs, Cys61 interacts preferentially with Cys61 of another HadA molecule and thus observed homodimers are formed.

Figure 5.

Formation of HadA dimer under cell-free conditions. SDS-PAGE analysis of proteins from reaction mixtures containing: (A) isolated proteins HadA and EthA, as well as TAC or Coum-TAC. The samples were analyzed in non-reducing environment. Up: gel stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue; Down: immunodetection using anti-His antibodies; (B) only isolated protein HadA and TAC or Coum-TAC. The samples were analyzed in non-reducing environment. Up: gel stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue; Down: immunodetection using anti-His antibodies; (C) isolated proteins HadA and EthA, as well as TAC or Coum-TAC. The samples were analyzed in the presence of 2-mercaptoethanol. Left: gel stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue / Right: immunodetection using anti-His antibodies.

Covalent binding of EthA-activated Coum-TAC to HadA.

To demonstrate that once activated Coum-TAC might act on HadA, the EthA activation reaction was performed in the presence of HadA protein. The blank control was performed omitting NADPH to hinder the EthA-catalyzed reaction. After 1 h incubation of the reaction at 37 °C, HadA was re-purified by Ni-NTA chromatography, to remove EthA as well as any unbound compound, and dialyzed. Finally, the UV-visible spectra of the HadA samples were analyzed. As depicted in Figure 6A, the UV-Vis spectrum of HadA incubated with EthA reaction shows an additional peak at 470 nm, which is characteristic of the Coum-TAC compound. This peak being also present in the blank reaction, it is conceivable that Coum-TAC can bind HadA with low affinity, which is greatly increased upon EthA activation that mediates the formation of interaction. Thus, to ascertain if a covalent bound is formed between HadA and the activated Coum-TAC, the protein was subjected to heat denaturation. The denaturated protein was centrifuged, the pellet was resuspended in 10 % sodium dodecylsulfate solution and for both pellet and supernatant, UV-Vis spectra were recorded. As shown in Figure 6B, the peak at 470 nm of Coum-TAC was present in the spectrum of the denaturated HadA, only if the protein had been incubated with the complete reaction. Moreover, the labeled protein showed a fluorescence spectrum similar to that of the Coum-TAC (Figure 6C); once again, the protein after thermal denaturation showed fluorescence only after incubation with Coum-TAC, EthA and NADPH (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Covalent binding of EthA-activated Coum-TAC to HadA. (A) UV-vis spectrum of HadA protein, re-purified after the reaction with EthA and Coum-TAC (black line), compared with the blank reaction (red line). Green line represents the spectrum of Coum-TAC, while yellow line is the spectrum of HadA before incubation. (B) UV-vis spectrum of HadA/Coum-TAC adduct after heat denaturation (black line), compared with the blank reaction (red line). (C) Emission spectra (excitation at 470 nm) of HadA/Coum-TAC adduct at 0.5 mg/mL (green line), 1 mg/mL (red line) and 2 mg/mL (black line). (D) Emission spectra (excitation at 470 nm) of HadA/Coum-TAC adduct after heat denaturation (black line), compared with the blank reaction (red line).

The fluorescence properties of Coum-TAC are not altered by the EthA activation or by the formation of the complex with HadA, as shown by the fact that the spectra of the reaction mixture did not change during the incubation (Figure S3 in the Supporting Information). Finally, to further confirm that Coum-TAC covalently bind HadA, the enzyme treated with EthA and the compound as above, was dialyzed and subjected for mass analysis. As shown in (Figure S4 in the Supporting Information), HadA protein incubated with DMSO showed a MW of 18060 Da. By contrast, the protein showed a MW of 18440 Da after incubation with Coum-TAC, with a mass increase of 380 ± 40 Da thus compatible with the formation of a covalent adduct.

Taken together, these data clearly demonstrate that EthA promotes the formation of a covalent adduct between Coum-TAC and HadA.

Fluorescent labeling of M.tb mycobacteria in the presence of Coum-TAC.

With the previous results in hand, we further investigated the ability of Coum-TAC to image M.tb cells growths using fluorescence microscopy with the idea to label HadA and to get insights on its localization in the mycobacteria. From previous studies, FAS-II enzymes were shown to colocalize at the poles and septa of the mycobacterial cells.12 With this in mind, we decided to monitor the location of fluorescence over time in a M.tb H37Rv strain in the presence of Coum-TAC at 0.5 µg/mL. Time-lapse fluorescence microscopy analyses of Coum-TAC incorporation in mycobacteria show a preferential accumulation at the poles and septa of the mycobacteria (Figures 7A–B).35 Interestingly Coum-TAC accumulation can be observed as soon as 2 hours after incubation with manifest peaks after 18 hours. To go further and explore whether the so-observed pattern of Coum-TAC incorporation can be monitored at the population level, we compared the accumulation of Coum-TAC in M.tb at 18 hours after incubation with the accumulation of two model compounds i) coumarin 466, ie. the fluorescent moiety of Coum-TAC and ii) compound C2, ie. the hydrolyzed form of Coum-TAC (Figure 7E). To do this, we employed Lattice-Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM),36 a super-resolution microscopy technique in order to get a more resolved localization of these fluorescent compounds in M.tb (Figures 7C–D). The obtained images first revealed that coumarin 466 is poorly incorporated in M.tb in sharp contrast to C2 and Coum-TAC compounds. Moreover, the patterns of incorporation of Coum-TAC and C2 are significantly different, despite the observed heterogeneity which is expected37,38. While Coum-TAC proved to accumulate preferentially in both poles of M.tb in the form of foci, the accumulation of C2 in M.tb is homogeneous, with a slightly increased accumulation in one of the poles, without forming foci. Also of significance is that the noticeable difference of incorporation patterns of Coum-TAC vs C2 further revealed the stability of Coum-TAC under the applied biological conditions.

Figure 7.

Imaging of M.tb H37Rv strain incubated with Coum-TAC. (A) Monitoring of fluorescence in M.tb H37Rv mycobacteria expressing m-Cherry (red) with time-dependent fluorescence increase of Coum-TAC (in green) at the poles and septa. (B) Time-dependent Coum-TAC distribution along the medial axis of the mycobacteria. (C) Lattice-SIM microscopy of coumarin 466, C2 and Coum-TAC (in green) in M.tb H37Rv mycobacteria expressing m-Cherry (red). (D) M.tb was segmented using mCherry fluorescence and fluorescence intensity profiles of each compound was measured along the medial axis of each bacilli using the MicrobeJ plugin of ImageJ. Results show variations of intensity along the medial axis from the first pole (P0) to the opposite pole at regular intervals (Px). Results show Mean±SEM of >100 individual bacteria per condition. (E) Chemical structures of coumarin 466 and C2.

Altogether, our results proving the mechanism of action of Coum-TAC together with the localization studies in M.tb strongly indicate that it selectively accumulates at the poles, thus suggesting the polar localization of HadA enzyme similar as other FAS-II enzymes.

CONCLUSION

We reported herein the rational design and straightforward synthesis of Coum-TAC, a covalent conjugate of a thiacetazone-derived anti-TB agent with a fluorescent coumarin-based moiety enabling the dual covalent inhibition and fluorescent labeling of HadA. First, Coum-TAC proved to exhibit an excellent anti-TB efficiency with a profile similar to that of well-known thiacetazone derivatives. The similarity of mode of action was further confirmed by the effective activation of Coum-TAC by EthA and by its reaction with HadA to furnish a fluorescent HadA/Coum-TAC adduct. Finally, the easy-to-prepare molecule Coum-TAC was successfully implemented as an imaging probe capable of labeling Mycobacterium tuberculosis with a manifest selectivity for the poles of the bacteria, thus suggesting a polar localization of HadA in M.tb.

Further works, including structural optimization as well as pharmacological and toxicological studies, are now needed to evaluate the relevance of Coum-TAC or analogues as novel drug candidates against Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

METHODS

Chemistry – synthesis of Coum-TAC (Scheme 2)

General –

Starting materials were purchased at the highest commercial quality and used without further purification unless otherwise stated. Cyclohexane, acetic acid, ethanol (EtOH), dichloromethane, (N,N)-dimethylformamide (DMF), diethyl ether and ethyl acetate (EtOAc) and were purchased and used as received. – Reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography carried out on silica plates (silica gel 60 F254, Merck) using UV-light for visualization. – Evaporation of solvents were conducted under reduced pressure at temperatures less than 30 °C. – Melting points (M.p.) were measured in open capillary tubes on a Stuart SMP30 apparatus and are uncorrected. – IR spectra were obtained from the ‘Service Commun de Spectroscopie Infrarouge’ of the Plateforme Scientifique et Technique, Institut de Chimie de Toulouse (FR2599), and values are reported in cm−1. – 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 300 spectrometer at 300 and 75 MHz, respectively. Chemical shifts (δ) and coupling constants (J) are given in ppm and Hertz (Hz), respectively. The signal multiplicity is described according to the following abbreviations: s (singlet), bs (broad singlet), d (doublet), and t (triplet). Chemical shifts (δ) are reported relative to the residual solvent as an internal standard (DMSO-d6: δ = 2.50 ppm for 1H and δ = 39.5 ppm for 13C). – Electrospray (ESI) low/high-resolution mass spectra were obtained from the ‘Service Commun de Spectroscopie de Masse’ of the Plateforme Technique, Institut de Chimie de Toulouse (FR2599). Accurate mass measurements (HRMS) were performed with a Q-TOF analyzer. – Crystallographic data for compound 339,40 were collected on a Bruker-AXS Quazar APEX II diffractometer using a 30 W air-cooled microfocus source (ImS) with focusing multilayer optics at a temperature of 193(2)K, with MoKα radiation (wavelength - 0.71073 Å) using phi- and omega-scans. Semi-empirical absorption correction was employed.41 The structure was solved using an intrinsic phasing method (SHELXT),42 and refined using the least-squares method on F2.37 All non-H atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. Hydrogen atoms were refined isotropically at calculated positions using a riding model with their isotropic displacement parameters constrained to be equal to 1.5 times the equivalent isotropic displacement parameters of their pivot atoms for terminal sp3 carbon and 1.2 times for all other carbon atoms.

Synthesis of precursor 3 (5-(7-((N,N)-diethylamino)-2-oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde) –

Step 1 – In a 250 mL three-neck flask equipped with a Dean-Stark apparatus were successively added 4-(N,N)-diethylaminosalicylaldehyde (15.0 mmol), 2-thiopheneacetonitrile (15.0 mmol), cyclohexane (25 mL) and activated IRA-900 resin (5 g) as strong basic catalyst. The resulting mixture was then heated at reflux under nitrogen and after 8 h stirring, the reaction was complete as revealed by TLC analysis. After cooling to room temperature, the solid materials were removed by filtration and further washed with dichloromethane. The resulting organic phase was then evaporated to give the iminocoumarin intermediate 1 as a solid which was used in the second step without any further purification. - Step 2 – A mixture of acetic acid (20 mL) and EtOH (10 mL) was next added to the crude 1. After 4 h stirring at 80 °C, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and the resulting solid was recovered by filtration, washed with cold EtOH and dried under vacuum to give the expected coumarin intermediate 2, again used in the next step without any further purification. - Step 3 – After dropwise addition of DMF (10 mL) to phosphorus oxytrichloride (3 mL) at 40°C, the resulting mixture was further stirred at 50 °C for 45 min. After cooling to room temperature, a suspension of crude 2 in DMF (3 mL) was added and the reaction mixture was heated to 60 °C. After 4 h stirring at this temperature, the reaction was complete as revealed by TLC analysis and the reaction mixture was then poured into ice (100 g). After stirring for two additional hours, the solid materials were recovered by filtration, washed with water and dried in an oven at 50 °C, to furnish the expected formylated coumarin 3 as orange crystals at >95 % purity as judged by 1H NMR. - Yield 78 %. - This formylated coumarin precursor 3 is a known compound and exhibit spectroscopic data identical to the previously ones in the literature.43, 44

Synthesis of Coum-TAC ((E)-((5-(7-((N,N)-diethylamino)-2-oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl)thiophen-2-yl)methylene)hydrazine-1-carbothioamide) –

In a ChemSpeed Accelerator SLT-106 synthesizer reactor equipped with a refrigerant system were successively added coumarin 3 (0.3 mmol), thiosemicarbazide (0.3 mmol), EtOH (15 mL) as solvent, and 1 M aqueous HCl (15 μL). After 5 h orbital shaking at 600 rpm and 90 °C, the resulting precipitate was recovered by filtration, washed with diethyl ether and EtOH and dried under vacuum to furnish Coum-TAC in pure forms as an orange solid. - Yield 89 %. - M.p. 260 °C. - Rf = 0.50 (4:6 cyclohexane/EtOAc). - FTIR-ATR (neat) 3345, 3250, 3165, 1680, 1610, 1575, 1510 cm−1. - 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 11.44 (s, 1H), 8.46 (s, 1H), 8.21 (d, J = 0.9 Hz, 1H), 8.19 (bs, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (bs, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.46 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 4H), 1.14 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 6H). - 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO): δ = 177.4, 159.6, 155.4, 150.8, 139.3, 138.1, 138.0, 137.9, 130.6, 129.8, 124.4, 112.3, 109.8, 108.1, 96.2, 44.2, 12.4. - LRMS (ESI, positive mode): m/z (rel intensity) 401 ([MH]+, 100).

Biology –

MIC determination in vitro –

M.tb strain H37Rv, used as the reference strain, and all the M.tb mutants were grown at 37 °C in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco), supplemented with 0.05% Tween80, or on solid Middlebrook 7H11 medium (Difco) supplemented with oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC). MICs for the compounds were determined by means of the micro-broth dilution method. Dilutions of M.tb wild-type or mutant strains (about 105–106 cfu/mL) were streaked onto 7H11 solid medium containing a range of drug concentrations. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for about 21 days and the growth was visually evaluated. The lowest drug dilution at which visible growth failed to occur was taken as the MIC value. Results were expressed as the average of at least three independent determinations. M.tb H37Ra strains carrying empty vectors pMV261 or pVV16 and M.tb H37Ra InhA41 or HadABC33 overproducing strains were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco) supplemented with albumin-dextrose-catalase and 0.05 % Tween 80 in 96-well plates in the presence of 0, 0.001, 0.005, 0.01, 0.02, 0.05, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 5, 25 and 50 μg/mL of Coum-TAC or TAC. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 12 days and the growth was evaluated by measuring the values at OD (600 nm).

Time-killing assay –

M.tb H37Rv was cultured in 7H9 broth to mid-log phase. Bacteria were diluted to about 105 CFU/ml to inoculate 10-mL cultures growing in 50 ml Falcon tubes. TAC and Coum-TAC were added at MIC concentration (0.5 and 1 µg/ml, respectively) and 10-fold. At indicated time points, samples were collected, 10-fold serially diluted samples were plated on Middlebrook 7H11 agar plates supplemented with 10% OADC. After three weeks, viable counts were determined. Isoniazid was used as control at 0.5-fold MIC concentration.

14C metabolic labeling of M. tb H37Ra and analysis of lipids and mycolic acids –

The M.tb H37Ra strain was grown by shaking at 37 °C in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco) supplemented with albumin-dextrose-catalase and 0.05 % Tween 80. At OD (600 nm) of 0.27, the culture was divided into 200 µL aliquots and a DMSO solution of the tested compound was added in 0, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1 and 0.25 µg/mL final concentrations. The final concentration of DMSO in each culture was kept 2 %. The cells grew 24 h at 37 °C shaking at 120 rpm. Then [1,2-14C]-acetate (specific activity 110 mCi/mmol, ARC) was added in the final concentration 0.5 µCi/mL and the cultures continued growing for next 24 h. The cells were harvested and the lipids were extracted with 3 mL chloroform/methanol (1:2) at 56 °C for 2 h followed by two extractions with 3 mL chloroform/methanol (2:1) at the same conditions. The organic extracts were combined together in the clean tube, dried under N2 and washed by Folch.45 Isolated lipids were dissolved in 50 µL of chloroform: methanol (2:1) and 5 µL were loaded on the thin-layer chromatography (TLC) silica gel plates F254 (Merck). Lipids were separated in chloroform/methanol/water (20:4:0.5) and the plates were exposed to autoradiography film Biomax MR (Kodak) at −80 °C for 5 days. Methyl esters of fatty acids (FAME) and mycolic acids (MAME) were prepared as previously described.46 Dried extracts were dissolved as described for lipids and 5 µL were loaded on TLC plates and different forms of methyl esters were separated in n-hexane/ethyl acetate (95:5), 3 runs and detected by autoradiography. The plates were exposed to autoradiography film Biomax MR (Kodak) at −80 °C for 5 days.

Production of M.tb EthA and activation of Coum-TAC –

EthA from M.tb was expressed and purified to homogeneity, according to the previously published method.31 Enzyme activity assays were performed by a spectrophotometric method, following the decrease in absorbance of NADPH at 340 nm (ε = 6.22 mM−1 cm−1).31 Assays were performed at 37 °C, in an Eppendorf BioSpectrometer. Reaction mixtures typically contained 50 mM potassium phosphate pH 8.0, 0.2 mM NADPH, 10 µM bovine serum albumin (BSA), 50 µM of Coum-TAC, and the reaction was started by adding the enzyme solution (1 µM).

Steady-state kinetics parameters were determined by assaying the enzymes at least at 8 different concentrations of compound. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the kinetic constants, Km and kcat, were determined fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using Origin 8 software.

In order to obtain the HadA protein complexed with the EthA activated Coum-TAC, the enzyme was incubated with the compound in the presence of the monooxygenase. Briefly, HadA (50 µM) was incubated with EthA (10 µM) in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 8.0, 200 µM NADPH, 10 µM Bovine Serum Albumin, 100 µM Coum-TAC, at 37 °C. For the blank control, NADPH was omitted from the reaction mixture, in order to avoid prodrug activation.

The reaction was followed by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm of NADPH, and after 1 h of incubation, the reaction mixture was loaded on a Ni-NTA column equilibrated in 50 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl. The column was washed with the same buffer to elute EthA, unbound Coum-TAC and metabolite(s), then HadA was eluted with 500 mM imidazole in the same buffer, dialyzed against 50 mM potassium phosphate pH 8.0, and concentrated. The formation of the HadA-Coum-TAC was assessed by monitoring the UV-vis and fluorescence spectra. Fluorescence measurements were performed on a Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer (Varian). The excitation wavelength was 470 nm (3 nm slit width) and the emission was recorded between 500 and 680 nm (10 nm slit width). To confirm the covalent nature of the interaction between HadA and the activated Coum-TAC, the protein and the compound were incubated with EthA, then HadA purified as above. The protein was then incubated at 100 °C for 10 minutes. The denaturated protein was centrifuged 15 min at 12000 rpm, resuspended in a 10 % aqueous sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) solution, and UV-vis and fluorescence spectra were again recorded and compared to that of the control reaction, performed as above.

For MS analysis, the samples prepared as above were dialyzed, concentrated to 20 μl, diluted 1:5 in methanol-water 1:1 containing 0.01% formic acid, and directly analyzed in mass spectrometry, using an Ion Trap (LCQ FleetTM) mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization (ESI) ion source controlled by Xcalibur software 2.2. Mass spectra, recorded for two minutes, were generated in positive ion mode under constant instrumental conditions: source voltage 5.0 kV, capillary voltage 46 V, sheath gas flow 20 (arbitrary units), auxiliary gas flow 10 (arbitrary units), sweep gas flow 1 (arbitrary units), capillary temperature 210°C, tube lens voltage 105 V. MS/MS spectra, obtained by CID studies in the ion trap, were performed with an isolation width of 3 Da m/z, the activation amplitude was 35% of ejection RF amplitude that corresponds to 1.58 V. Spectra deconvolution was performed using UniDec 3.2.0 software.

In vitro monitoring the effect of TAC and Coum-TAC on HadA protein –

Recombinant HadA protein carrying C-terminal Has6-tag was produced in M. smegmatis mc2155 strain using pVV16-hadA construct.10 The cells were grown in LB medium containing 20 µg/mL kanamycin at 37 °C, shaking (130 rpm) and harvested in the exponential phase of growth. The cells were resuspended in equal volume of isolation buffer (50 mM TrisHCl pH = 7.5; 150 mM NaCl; 5 mM Imidazole; 10 µg/mL DNase; Roche EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor) and disrupted by sonication (20 cycles, 60s on, 90s off). Cell lysate was centrifuged at 10 000 x g, 15 min, 4 °C and the protein HadA was isolated from resulting supernatant using cobalt-based affinity chromatography with HiTrap TALON crude 1 mL column connected to ÄKTA start chromatography system. The protein was eluted with gradually increasing concentration of imidazole, up to 500 mM. Selected fractions containing isolated protein HadA were collected, desalted and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter unit (10 kDa cut off).

Recombinant EthA protein carrying C-terminal Has6-tag was produced in M. smegmatis mc2155 strain using pJAM2-ethA construct. The construct was prepared by cloning of PCR-amplified ethA from M. tuberculosis H37Rv into pJAM2 vector harboring a kanamycin resistance cassette47 using ScAI and XbaI restriction sites. M. smegmatis mc2155 pJAM2-ethA was cultivated in M63 medium at 37 °C until OD = 0.6 at 600 nm. At that point recombinant protein production was induced by adding 0.2 % acetamide and the cells were further cultivated for 24 h at 30 °C. The cells were resuspended in equal volume of isolation buffer (25 mM TrisHCl pH = 7.5; 300 mM NaCl) and disrupted by sonication (20 cycles, 60s on, 90s off). Cell lysate was centrifuged at 10 000 x g, 15 min, 4 °C and the protein EthA was isolated from resulting supernatant as described above for HadA protein.

In vitro assay was performed to monitor the effect of TAC and Coum-TAC on HadA protein. Reaction mixtures contained 10 µg of HadA protein, 10 µg of EthAtb protein, 4 mM NADPH, 100 mM KCl, 100 μg/mL BSA and 0, 1, 2, 5 and 10 µg/mL TAC or 0, 10, 20 and 40 µg/mL Coum-TAC (dissolved in DMSO, 2 % final concentration in the reaction mixtures) and 50 mM TrisHCl (pH = 7.5) in 50 µL final volume. Reaction mixtures were incubated 1 h at 37 °C and 10 μl were mixed with non-reducing 2 x sample buffer (without β-mercaptoethanol) and loaded on SDS PAGE. Alternatively, 10 µL were mixed with reducing 2 x sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol in 2 % final concentration, incubated 10 min at 95 °C and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with Coomasie Brilliant Blue R-250 or blotted to nitrocellulose membrane and detected with antiHis antibodies.

Live fluorescence microscopy –

M.tb strain H37Rv constitutively expressing mCherry was grown to the exponential phase in 7H9 media supplemented with 10 % OADC 0.5 % glycerol and an aliquot was plated on glass bottom 35 mm petri dishes (ibidi). After 10 minutes, the liquid was removed to leave a thin lawn of cells. Next, 7H9 media containing 0.2 % Noble agar and Coum-TAC (0,5 µg/ml) was overlaid on top of cells and left to solidify for 45 minutes at room temperature. The specimen was mounted on a Andor/Olympus spinning disk microscope equipped with a emCCD camera (Andor iXon Life 888) and kept at 37 °C for time-lapse imaging. To follow Coum-TAC incorporation overtime, a Z-stack (step 355 nm) was acquired every 15 min for two channels (525/40 and 607/36) with an Olympus 60x NA=1.35 objective. The profile of Coum-TAC incorporation was evaluated by drawing a line at the longest length of the cell, defined by mCherry fluorescence.

Lattice-SIM microscopy –

M.tb strain H37Rv constitutively expressing mCherry was grown to the exponential phase in 7H9 media supplemented with 10 % OADC 0.5% glycerol and Coum-TAC, C2 or coumarin 466 were added at a concentration of 0.5 µg/mL. 18 hours later, each bacteria suspension was washed in PBS tween 0.05 % and fixed for 2 hours in PFA 4 %. An aliquot of the suspension was placed on a slide and included in Prolong Glass mounting media. Incorporation of compounds was quantified using a Zeiss Elyra 7 Lattice-SIM microscope with a Zeiss 63x NA=1.4 objective and image analysis was performed in acquired Z stacks using MicrobeJ plugin48 in ImageJ Software. More specifically, mCherry fluorescence of M.tb was used to generate a smoothed particle contour of the bacilli using a skeletonization algorithm. Next, medial axes were generated from the particle contour and intensity profiles were calculated from the first pole (P0) to the opposite pole (Px) at regular levels. More than 100 individual bacteria were quantified per condition.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by i) the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and the University of Toulouse (M.D., F.G., C.C., A. P., C.L., S.C.), ii) the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR): Dipartimenti di Eccellenza Program (2018–2022) - Dept. of Biology and Biotechnology “L. Spallanzani”, University of Pavia (L.R.C., G.D., M.F., M.R.P.), iii) the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic, VEGA 1/0301/18 (J.K.), iv) the Slovak Research and Development Agency, APVV-15-0515 (J.K.) and v) the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/National Institutes of Health grant AI130929 (M.J.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH. A.F. thanks the Université de Sfax (Tunisia) for financial support. Finally, we gratefully acknowledge i) the TRI-IPBS Imaging Core Facility, member of TRI and Genotoul as well as the support of the Occitanie Region and the Fonds Européen de DEveloppement Régional (FEDER) through the ‘Plateformes régionales de recherche et d’innovation’ program, and ii) the Institut de Chimie de Toulouse, in particular Nathalie SAFFON, for their technical support.

ABBREVIATIONS

- TB

Tuberculosis

- M.tb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- INH

isoniazid

- RIF

rifampicin

- EMB

ethambutol

- PYR

pyrazinamide

- ETH

ethionamide

- ISO

isoxyl

- Mas

mycolic acids

- FAS

fatty-acid synthase

- ACP

acyl-carrier-protein

- TAC

thiacetazone

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- Ac

acetyl

- DMF

(N,N)-dimethylformamide

- LC/MS

liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry

- CI

clinical isolate

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- DprE1

decaprenyl-phosphoribose-2’-epimerase

- DPR

decaprenylphosphoryl-β-D-ribose

- DprE2

decaprenyl-phospho-2’-keto-D-arabinose reductase

- DPX

decaprenyl-phosphoryl-2’-keto-D-erythro-pentofuranose

- RND

resistance, nodulation and division

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- SD

standard deviation

- OD

optical density

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

- TMM

trehalose monomycolates

- TDM

trehalose dimycolates

- FAME

fatty acid methyl esters

- MAME

mycolic acid methyl esters

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- CL

cardiolipin

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- Cys

cysteine

- His

histidine

- Ni-NTA

nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- UV-vis

ultra-violet visible

- EtOAc

ethyl acetate

- EtOH

ethanol

- M.p.

melting point

- IR

infrared

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- FTIR-ATR

Fourier transform infrared-attenuated total reflectance

- OADC

oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- MS

mass spectrometry

REFERENCES

- (1).GBD Tuberculosis Collaborators. (2018) Global, regional, and national burden of tuberculosis, 1990–2016: results from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study. Lancet Infect. Dis 8, 1329–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Grobusch MP and Kapata N (2018) Global burden of tuberculosis: where we are and what to do. Lancet Infect. Dis 18, 1291–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Vilchèze C, Morbidoni HR, Weisbrod TR, Iwamoto H, Kuo M, Sacchettini JC, Jacobs WR (2000) Inactivation of the inhA-encoded fatty acid synthase II (FAS-II) enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase induces accumulation of the FAS-I end products and cell lysis of Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol 182, 4059–4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Sacco E, Covarrubias AS, O’Hare HM, Carroll P, Eynard N, Jones TA, Parish T, Daffé M, Bäckbro K, and Quémard A (2007) The missing piece of the type II fatty acid synthase system from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 14628–14633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Slama N, Jamet S, Frigui W, Pawlik A, Bottai D, Laval F, Constant P, Lemassu A, Cam K, Daffé M Brosch R, Eynard N, and Quémard A (2016) The changes in mycolic acid structures caused by hadC mutation have a dramatic effect on the virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. microbial 99, 794–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).DeBarber AE, Mdluli K, Bosman M, Bekker LG, and Barry CE 3rd (2000) Ethionamide activation and sensitivity in multidrug- resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 97, 9677–9682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Qian L, and Ortiz de Montellano PR (2006) Oxidative activation of thiacetazone by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis flavin monooxygenase EtaA and human FMO1 and FMO3. Chem. Res. Toxicol 19, 443–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Dover LG, Alahari A, Gratraud P, Gomes JM, Blowruth V, Reynolds RC, Besra GS, and Kremer L (2007) EthA, a common activator of thiocarbamide-containing drugs acting on different mycobacterial targets. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 51, 1055–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Korduláková J, Janin YL, Liav A, Barilone N, DosVultos T, Rauzier J, Brennan PJ, Gicquel B, and Jackson M (2007) Isoxyl activation is required for bacteriostatic activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 51, 3824–3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Wang F, Langley R, Gulten G, Dover LG, Besra GS, Jacobs WR Jr., and Sacchettini JC (2007) Mechanism of thioamide drug action against tuberculosis and leprosy. J. Exp. Med 204, 73–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Grzegorzewicz AE, Eynard N, Quemard A, North EJ, Margolis A, Lindenberger JJ, Jones V, Kordulakova J, Brennan PJ, Lee RE, Ronning DR, McNeil MR, and Jackson M (2015) Covalent modification of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis FAS-II dehydratase by Isoxyl and Thiacetazone. ACS Infect. Dis 1, 91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Carel C, Nukdee K, Cantaloube S, Bonne M, Diagne CT, Laval F, Daffé M, and Zerbib D, (2014) Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins involved in mycolic acid synthesis and transport localize dynamically to the old growing pole and septum. PloS One 9 (5), e97148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Coxon GD, Craig D, Corrales RM, Vialla E, Gannoun-Zaki L, and Kremer L (2013) Synthesis, antitubercular activity and mechanism of resistance of highly effective thiacetazone analogues. PLoS One 8, e53162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Halloum I, Viljoen A, Khanna V, Craig D, Bouchier C, Brosch R, Coxon G, Kremer L (2017) Resistance to thiacetazone derivatives active against Mycobacterium abscessus involves mutations in the MmpL5 Transcriptional Repressor MAB_4384. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 61, e02509–e02516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Alahari A, Trivelli X, Guérardel Y, Dover LG, Besra GS, Sacchettini JC, Reynolds RC, Coxon GD, and Kremer L (2007) Thiacetazone, an antitubercular drug that inhibits cyclopropanation of cell wall mycolic acids in mycobacteria. PLoS One 2 (12), e1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).(a) Sabnis RW (2015) Handbook of fluorescent dyes and probes, Wiley, Oboken, NJ; [Google Scholar]; (b) Wagner BD (2009) The use of coumarins as environmentally-sensitive fluorescent probes of heterogeneous inclusion systems. Molecules 14, 210–237; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zabradink M (1992) The production and application of fluorescent brightening agents, Wiley, New York. [Google Scholar]

- (17). Coumarin 466 is commercially available and sold as popular fluorescent label.

- (18).(a) For reviews/books dealing with the coumarin scaffold as a relevant pharmacophore, see:Stefanachi A, Leonetti F, Pisani L, Catto M, and Carotti A (2018) Coumarin: a natural, privileged and versatile scaffold for bioactive compounds. Molecules 23, E250; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ren Q, Gao C, Xu Z, Yu Y, Liu ML, Wu X, Guan JG, Feng L (2018) Bis-coumarin derivatives and their biological activities. Curr. Top. Med. Chem 18, 101–113; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hu YQ, Xu Z, Zhang S, Wu X, Ding JW, Lv ZS, and Feng LS (2017) Recent developments of coumarin-containing derivatives and their anti-tubercular activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem 136, 122–130; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Keri RS, Sasidhar BS, Nagaraja BM, and Santos MA (2015) Recent progress in the drug development of coumarin derivatives as potent antituberculosis agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem 100, 257–269; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Sandhu S, Bansal Y, Silakari O, and Bansal G (2014) Coumarin hybrids as novel therapeutic agents. Biooorg. Med. Chem 22, 3806–3814; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Penta S (2016) Advances in structure and activity relationship of coumarin derivatives, Academic Press, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- (19).(a) Suparji NS, Chan G, Sapili H, Arshad NM, In LLA, Awang K, and Nagoor NH (2016) Geranylated 4-phenylcoumarins exhibit anticancer effects against human prostate cancer cells through caspase-independent mechanism. PLoS One 11, e0151472; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Galayev O, Garazd Y, Garazd M, and Lesyk R Synthesis and anticancer activity of 6-heteroarylcoumarins. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2015, 105, 171–181; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Donnelly AC, Mays JR, Burlison JA, Nelson JT, Vielhauer G, Holzbeierlein J, and Blagg BSJ (2008) The design, synthesis and evaluation of coumarin ring derivatives of the novobiocin scaffold that exhibit anti-proliferative activity J. Org. Chem 73, 8901–8920; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Thakur A, Singla R, and Jaitak V (2015) Coumarins as anticancer agents: a review on synthetic strategies, mechanism of action and SAR studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem 101, 476–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).(a) Sashidhara KV, Modukuri RK, Singh S, Bhaskara Rao K, Aruna Teja G, Gupta S, and Shukla S (2015) Design and synthesis of new series of coumarin-aminopyran derivatives possessing potential anti-depressant-like activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 25 (2), 337–341; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sashidhara KV, Rao KB, Singh S, Modukuri RK, Aruna Teja G, Chandasana H, Shukla S, and Bhatta RS (2014) Synthesis and evaluation of new 3-phenylcoumarin derivatives as potential antidepressant agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 24, 4876–4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Shaik JB, Palaka BK, Penumala M, Kotapati KV, Devineni SR, Eadlapalli S Darla MM, Ampasala DR, Vadde R, and Amooru GD (2016) Synthesis, pharmacological assessment, molecular modeling and in silico studies of fused tricyclic coumarin derivatives as a new family of multifunctional anti-Alzheimer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem 107, 219–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huang M, Xie SS, Jiang N, Lan JS, Kong LY, and Wang XB (2015) Multifunctional coumarin derivatives: monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibition, anti-β-amyloid (Aβ) aggregation and metal chelation properties against Alzheimer’s disease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 25, 508–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Pu W, Lin Y, Zhang J, Wang F, Wang C, Zhang G (2014) 3-Arylcoumarins: synthesis and potent anti-inflammatory activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 24(23), 5432–5434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Martinčič R, Mravljak J, Švajger U, Perdih A, Anderluh M, and Novič M (2015) In Silico Discovery of novel potent antioxidants on the basis of pulvinic acid and coumarin derivatives and their experimental evaluation. PLoS One 10, e0140602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).(a) Kudo E, Taura M, Matsuda K, Shimamoto M, Kariya R, Goto H, Hattori S, Kimura S, and Okada S (2013) Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by a tricyclic coumarin GUT-70 in acutely and chronically infected cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 23, 606–609; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Boon Beng Ong E, Watanabe N, Saito A, Futamura Y, Abd El Galil KH, Koito A, and Najimudin N, and Osada H (2011) Vipirinin, a coumarin-based HIV-1 Vpr Inhibitor, interacts with a hydrophobic region of VPR. J. Biol. Chem 286, 14049–14056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).(a) Xy Z-Q, Barrow WW, Suling WJ, Westbrook L, Barrow E, Lin Y-M, and Flavi n M. T. (2004) Anti-HIV natural product (+)-calanolide A is active against both drug-susceptible and drug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Bioorg. Med. Chem 12, 1199–1207; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stanley SA, Kawate T, Iwase N, Shimizu M, Clatworthy AE, Kazyanskaya E, Sacchettini JC, Ioerger TR, Siddiqi NA, Minami S, Aquadro JA, Grant SS, Rubin EJ, and Hung DT (2013) Diarylcoumarins inhibit mycolic acid biosynthesis and kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis by targeting FadD32. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 11565–11570; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Manvar A, Malde A, Verma J, Virsodia V, Mishra A, Upadhyay K, Acharya H, Coutinho E, and Shah A (2008) Synthesis, an ti-tubercular activity and 3D-QSAR study of coumarin-4-acetic acid benzylidene hydrazides. Eur. J. Med. Chem 43, 2395–2403; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Manvar A, Bavishi A, Radadiya A, Patel J, Vora V, Dodia N, Rawal K, and Shah A (2011) Diversity oriented design of various hydrazides and their in vitro evaluation against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv strains. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 21, 4728–4731; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) V. Virsodia V, Shaikh MS, Manvar A, Desai B, Parecha A, Loriya R, Dholariya K, Patel G, Vora V, Upadhyay K, Denish K, Shah A, and Coutinho EC (2010) Screening for in vitro antimycobacterial activity and three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) study of 4-(arylamino)coumarin derivatives. Chem. Biol. Drug Des 76, 412–424; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Angelova VT, Valcheva V, Vassilev NG, Buyukliev R, Momekov G, Dimitrov I, Saso L, Djukic M, and Shivachev B (2017) Antimycobacterial activity of novel hydrazide-hydrazone derivatives with 2H-chromene and coumarin scaffold. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 27, 223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Carrère-Kremer S, Blaise M, Singh VK, Alibaud L, Tuaillon E, Halloum I, van de Weerd R, Guérardel Y, Drancourt M, Takiff H, Geurtsen J, Kremer L (2015) A new dehydratase conferring innate resistance to thiacetazone and intra-amoebal survival of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol 96, 1085–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Albesa-Jové D, Chiarelli LR, Makarov V, Pasca MR, Urresti S, Mori G, Salina E, Vocat A, Comino N, Mohorko E, Ryabova S, Pfieiffer B, Lopes Ribeiro AL, Rodrigo-Unzueta A, Tersa M, Zanoni G, Buroni S, Altmann KH, Hartkoorn RC, Glockshuber R, Cole ST, Riccardi G, and Guerin ME (2014) Rv2466c mediates the activation of TP053 to kill replicating and non-replicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ACS Chem. Biol 9 (7), 1567–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Makarov V, Manina G, Mikusova K, Möllmann U, Ryabova O, Saint-Joanis B, Dhar N, Pasca MR, Buroni S, Lucarelli AP, Milano A, De Rossi E, Belanova M, Bobovska A, Dianiskova P, Kordulakova J, Sala C, Fullam E, Schneider P, McKinney JD, Brodin P, Christophe T, Waddell S, Butcher P, Albrethsen J, Rosenkrands I, Brosch R, Nandi V, Bharath S, Gaonkar S, Shandil RK, Balasubramanian V, Balganesh T, Tyagi S, Grosset J, Riccardi G, and Cole ST (2009) Benzothiazinones kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis by blocking arabinan synthesis. Science 324 (5928), 801–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Poce G, Bates RH, Alfonso S, Cocozza M, Porretta GC, Ballell L, Rullas J, Ortega F, De Logu A, Agus E, La Rosa V, Pasca MR, De Rossi E, Wae B, Franzblau SG, Manetti F, Botta M and Biava M (2013) Improved BM212 MmpL3 inhibitor analogue shows efficacy in acute murine model of tuberculosis infection. PLoS One 8 (2), e56980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Neres J, Hartkoorn RC, Chiarelli LR, Gadupudi R, Pasca MR, Mori G, Venturelli A, Savina S, Makarov V, Kolly GS, Molteni E, Binda C, Dhar N, Ferrari S, Brodin P, Delorme V, Landry V, de Jesus Lopes Ribeiro AL, Farina D, Saxena P, Pojer F, Carta A, Luciani R, Porta A, Zanoni G, De Rossi E, Costi MP, Riccardi G, and Cole ST (2015) 2-Carboxyquinoxalines kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis through noncovalent inhibition of DrpE1. ACS Chem Biol 10 (3), 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Chiarelli LR, Mori G, Orena BS, Esposito M, Lane M, de Jesus Lopes Ribeiro AL, Degiacomi G, Zemanova G, Szadocka S, Huszar S, Palcekova, Manfredi M, Gosetti F, Lelièvre J, Ballell L, Kazakova E, Makarov V, Marengo E, Mikusova K, Cole ST, Riccardi G, Ekins S, and Pasca MR (2018) A multitarget approach to drug discovery inhibiting Mycobacterium tuberculosis PyrG and PanK. Sc. Rep 8, 3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Mori G, Chiarelli LR, Esposito M, Makarov V, Bellinzoni M, Hartkoorn RC, Degiacomi G, Boldrin F, Ekins E, de Jesus Lopes Ribeiro AL, Marino LB, Centárová I, Svetlíková Z, Blaško J, Kazakova E, Lepioshkin A, Barilone N, Zanoni G, Porta A, Fondi M, Fani R, Baulard AR, Mikušová K, Alzari PM, Manganelli R, de Carvalho LP, Riccardi G, Cole ST, and Pasca MR (2015) Thiophenecarboxamide derivatives activated by EthA kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis by inhibiting the CTP synthase PyrG. Chem. Biol 22, 917–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Degiacomi G, Sammartino JC, Sinigiani V, Marra P, Urbani A, Pasca MR (2020) In vitro study of Bedaquiline resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis multi-drug resistant clinical isolates. Front Microbiol 11:559469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Grzegorzewicz AE, Kordulakova J, Jones V, Born SE, Belardinelli JM, Vaquie A, Gundi VA, Madacki J, Slama N, Laval F, Vaubourgeix J, Crew RM, Gicquel B, Daffe M, Morbidoni HR, Brennan PJ, Quemard A, McNeil MR, and Jackson M (2012) A common mechanism of inhibition of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis mycolic acid biosynthetic pathway by isoxyl and thiacetazone. J. Biol. Chem 287, 38434–38441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35). For live imaging of the real-time incorporation of Coum-TAC into M.tb strain H37Rv, see the Movie given as Supplementary Materials.

- (36).Betzig E (2005) Excital strategies for optical lattice microscopy. Opt. Express 13, 3021–3036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Dewachter L, Fauvart M, Michiels J (2019) Bacterial heterogeneity and antibiotic survival: understanding and combatting persistence and heteroresistance. Mol. Cell 17, 255–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Ackermann M (2015) A functional perspective on phenotypic heterogeneity in microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 13, 497–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39). CCDC1998723 for compound 3 contains the supplementary data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/?.

- (40). Selected data for compound 3 : C18H17NO3S, M = 327.38, monoclinic, space group P 21/c, a = 13.441(3) Å, b = 12.660(3) Å, c = 9.421(2) Å, β = 105.759(7)°, V = 1542.9(6) Å3, Z = 4, crystal size 0.20 × 0.02 × 0.02 mm3, 35538 reflections collected (2689 independent, Rint = 0.1700), 210 parameters, R1[I>2s(I)] = 0.0485, wR2 [all data]= 0.1215, largest diff. peak and hole: 0.211 and –0.230 eÅ−3.

- (41).Bruker, SADABS, Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Sheldrick GM (2015) SHELXT - Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 71, 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Ordonez-Hernandez J, Jimenez-Sanchez A, Garcia-Ortega H, Sanchez-Puig N, Flores-Alamo M, Santillan R, and Farfan N (2018) A series of dual-responsive Coumarin-Bodipy probes for local microviscosity monitoring. Dyes Pigm 157, 305–313. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Liang H, Xue Z, Qing Y, Yujin L, and Jianrong G (2013) Synthesis and photoelectric properties of coumarin type sensitizing dyes. Chin. J. Org. Chem 33, 1000–1004. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Folch J, Lees M, and Sloane Stanley GH (1957) A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem 226, 497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Phetsuksiri B, Baulard AR, Cooper AM, Minnikin DE, Douglas JD, Besra GS, and Brennan PJ (1999) Antimycobacterial activities of isoxyl and new derivatives through the inhibition of mycolic acid synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 43, 1042–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Triccas JA, Parish T, Britton WJ, and Gicquel B (1998) An inducible expression system permitting the efficient purification of a recombinant antigen from Mycobacterium smegmatis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett 167, 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Ducret A, Quardokus EM, Brun YV (2016) MicrobeJ, a tool for high throughput bacterial cell detection and quantitative analysis. Nat. Microbiol 1, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.