Abstract

Background

Whole lung tissue transcriptomic profiling studies in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have led to the identification of several genes associated with the severity of airflow limitation and/or the presence of emphysema, however, the cell types driving these gene expression signatures remain unidentified.

Methods

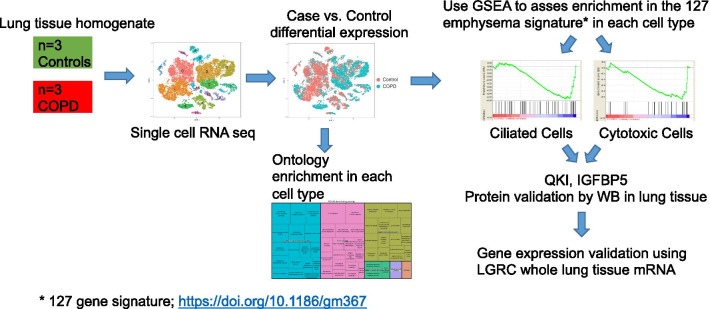

To determine cell specific transcriptomic changes in severe COPD, we conducted single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA seq) on n = 29,961 cells from the peripheral lung parenchymal tissue of nonsmoking subjects without underlying lung disease (n = 3) and patients with severe COPD (n = 3). The cell type composition and cell specific gene expression signature was assessed. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was used to identify the specific cell types contributing to the previously reported transcriptomic signatures.

Results

T-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding and clustering of scRNA seq data revealed a total of 17 distinct populations. Among them, the populations with more differentially expressed genes in cases vs. controls (log fold change >|0.4| and FDR = 0.05) were: monocytes (n = 1499); macrophages (n = 868) and ciliated epithelial cells (n = 590), respectively. Using GSEA, we found that only ciliated and cytotoxic T cells manifested a trend towards enrichment of the previously reported 127 regional emphysema gene signatures (normalized enrichment score [NES] = 1.28 and = 1.33, FDR = 0.085 and = 0.092 respectively). Among the significantly altered genes present in ciliated epithelial cells of the COPD lungs, QKI and IGFBP5 protein levels were also found to be altered in the COPD lungs.

Conclusions

scRNA seq is useful for identifying transcriptional changes and possibly individual protein levels that may contribute to the development of emphysema in a cell-type specific manner.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12931-021-01675-2.

Keywords: Single cell RNA-seq, COPD, Cigarette smoke

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common respiratory disorder characterized by irreversible expiratory airflow limitation in response to inhalation of noxious stimuli (e.g., cigarette smoke) [1]. COPD is the third leading cause of death [2] and a major economic burden in the United States [3].

COPD is a heterogeneous disorder that can manifest with multiple clinical phenotypes, including emphysema (destructive enlargement of the airspaces distal to terminal bronchioles), chronic bronchitis, and small airway disease [4–7]. Over the last few decades, several lung homogenates and airway transcriptomic studies have been conducted in order to reveal molecular pathways linked to the pathogenesis of smoking-related airflow limitations and emphysema [8–12]. These studies have resulted in the identification of several biological processes, now believed to be associated with smoking-related FEV1 decline [13–15], including (1) chronic immune response and inflammation [16, 17]; (2) imbalance of proteases/anti-proteases [18]; (3) oxidative stress [19, 20]; (4) cellular senescence (permanent loss of proliferative capacity) [21, 22]; and (5) lung epithelial cell (LEC) apoptosis.

In one of the most comprehensive transcriptomic analyses of smoking-related emphysema to date, Campbell, et al. profiled gene expression in eight separate regions (based on degree of emphysema) from six emphysematous lungs and compare those transcriptomes with two non-diseased lungs (8 regions × 8 lungs = 64 samples). They identified a total of 127 genes with expression levels significantly correlating with the emphysema severity [23]. Many genes upregulated with increased emphysema severity were involved in inflammation (e.g., the B-cell receptor signaling), while those downregulated with increasing disease severity were implicated in tissue repair (e.g., the transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) pathway) [23]. This 127 gene emphysema signature was enriched in the transversal studies of lung tissue of patients with severe COPD and emphysema [13, 15]. However, it remains to be elucidated which specific cell types contribute most to this smoking-related emphysematous and small airflow damage transcriptome signature.

Here, we used scRNA-seq technology to identify lung cell-type specific gene expression signatures associated with airflow limitation and/or emphysema. We examined the single-cell transcriptomes of cell populations from lung tissue samples obtained from a representative selection of three ex-smokers with severe COPD/emphysema and three nonsmokers without any history of lung disease. We compared our findings with previously reported whole lung tissue homogenate airflow limitation and emphysema signatures, and experimentally validated the key associated genes.

Methods

Human lung tissue samples

For scRNA seq, fresh lung parenchymal tissue samples were obtained from the upper lobes of three nonsmoking subjects without underlying lung disease who underwent warm autopsies and three patients with severe COPD who received lung transplantation (Table 1). For immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2a), frozen lung parenchymal tissue was obtained from smokers without any history of lung disease (n = 5), or very severe COPD (n = 7); both were provided by the University of Pittsburgh, Lung Tissue Research Consortium (LTRC), respectively (Table 2). Data from the Lung Genomics Research Consortium (LGRC) Cohort was used for gene expression analysis of QKI and IGFBP5 (Table 3). The COPD Specialized Center for Clinically Oriented Research (SCCOR) cohort was utilized for comparison of serum IGFBP5 levels between 40 patients with COPD and 40 smokers without clinically evident COPD (Table 4).

Table 1.

Three normal nonsmokers and three patients with severe COPD

| ID | Age | Sex | Smoking (pack-years) | FEV1/FVC | FEV1% ref | DLCO % ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL 1 | 57 | F | None | NA | NA | NA |

| NL 2 | 18 | M | None | NA | NA | NA |

| NL 3 | 23 | F | None | NA | NA | NA |

| COPD 1 | 65 | F | 60 | 0.33 | 33 | 14 |

| COPD 2 | 62 | F | 75 | 0.29 | 22 | 53 |

| COPD 3 | 61 | F | 45 | 0.25 | 21 | 20 |

Fig. 2.

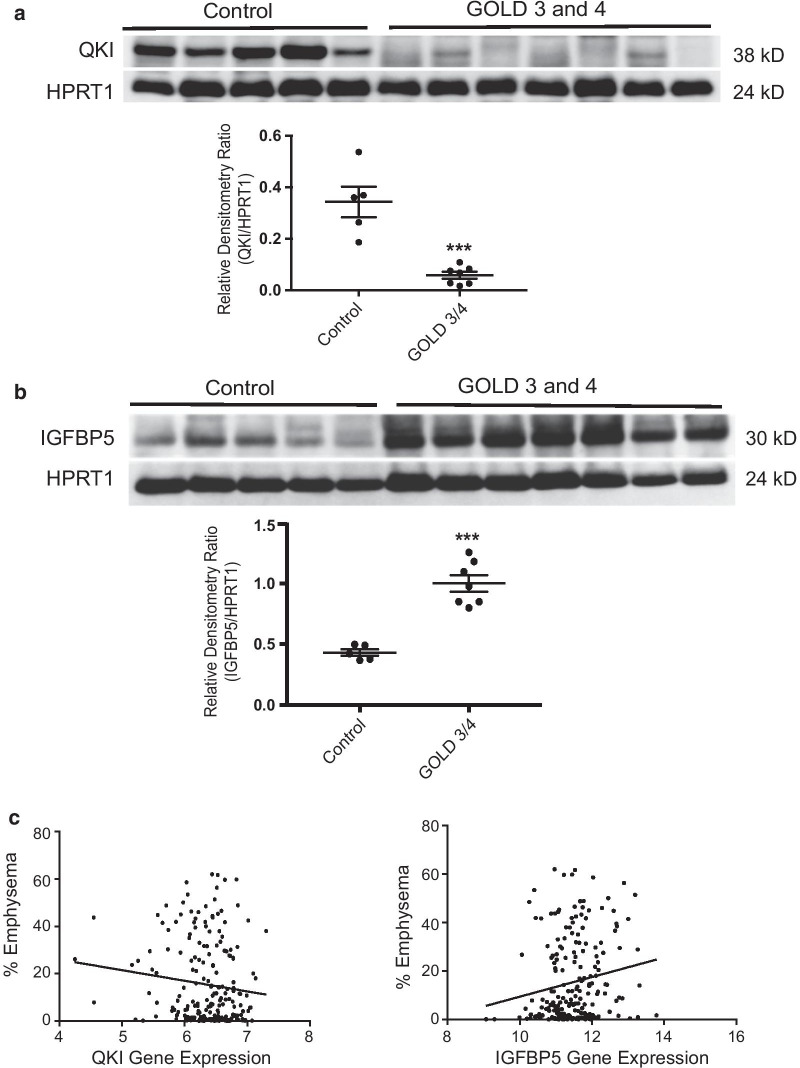

Quantifying protein levels of some genes significantly altered between normal and COPD lungs. a Whole parenchymal lung tissues from non-smokers without COPD (n = 5) and former-smokers with COPD GOLD stage 3 or 4 (n = 7) were evaluated for protein expression of QKI by immunoblot analysis. The densitometry data (QKI/HPRT1) obtained from individual groups are expressed as mean ± SEM. ***p value < 0.0001. b Whole parenchymal lung tissues from the same groups as in (a) were evaluated for protein expression of IGFBP5 by immunoblot analysis. The densitometry data (IGFBP5/HPRT1) obtained from individual groups are expressed as mean ± SEM. ***p value < 0.0001. c QKI and IGFBP5 gene expression in whole lung parenchymal tissue obtained from subjects with various severities of emphysema

Table 2.

Clinical and demographics of the control and COPD subjects (immunoblot analysis)

| Control | COPD (GOLD Stage 4) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 5 | 7 |

| Age, year, mean (SD) | 62.0 (10.0) | 62.0 (2.8) |

| Gender | 3 M/2F | 4 M/3F |

| Smoking (pack-years) | 35 (10.6) | 50.7 (23.1) |

Table 3.

Clinical and demographics of the Lung Genomics Research Consortium (LGRC) Cohort (used for QKI and IGFBP5 gene expression analysis)

| Control | COPD | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 108 | 219 |

| Age, year, mean (SD) | 63.6 (11.4) | 64.7 (9.7) |

| Gender (% Female) | 55% | 43% |

| Smoking status, (%) | ||

| Never | 30% | 5.50% |

| Current | 1.90% | 6.40% |

| Ever | 58% | 86.70% |

| Unknown | 10.10% | 1.40% |

| Pulmonary function, mean (SD) | ||

| FEV1, % predicted | 95 (12.6) | 50.6 (24.0) |

| FVC, % predicted | 94.4 (13.1) | 73,8 (19.5) |

| DLCO, % predicted | 84.1 (16.7) | 56.6 (23.1) |

| Emphysema, % mean (SD) | 15.4 (17.1) | |

DLCO diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide

Table 4.

Clinical and demographics of the SCCOR Cohort (used for IGFBP5 ELISA)

| Control | COPD | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 40 | 40 |

| Age, year, mean (SD) | 66.7 (7.5) | 67.5 (6.4) |

| Gender (% Female) | 42.50% | 42.50% |

| Current smoking (%) | 47.50% | 40% |

| Pack years (SD) | 50.3 (30.5) | 65.4 (29.1) |

| Pulmonary function, mean (SD) | ||

| FEV1, % predicted | 99.1 ± 14.7% | 70.7 ± 18.8% |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | 0.763 ± 0.037 | 0.535 ± 0.104 |

| Emphysema %F950a | 0.005 ± 0.003 | 0.107 ± 0.086 |

a % low-attenuation area defined as the fraction of voxels less than − 950 Houndsfield Unit of total voxels identified in regions of the lung

Preparation of single-cell libraries, sequencing, and analysis

The whole lung tissue samples were processed as described previously [24]. Briefly, lung tissue samples were digested, cell suspensions laded into the Chromium instrument (10× Genomics, Pleasanton, CA), and the resulting barcoded cDNAs were used to construct libraries. RNA-seq was conducted on all mixed samples as a pool. The total number of reads for the three single cell COPD samples was: 456,870,504 reads. Cell-gene specific molecular identifier counting matrices were generated and analyzed using Seurat [25] to identify distinct cell populations [26] and hierarchically clustered using Cluster 3.0 [27].

Reagents and antibodies

Chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical and Calbiochem. Polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were obtained from Bio-Rad. ECL Plus was obtained from Amersham. Antibodies were obtained from various sources: HPRT1 and EPAS1 antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling; QKI, RTN4, STOM, IGFBP5 and secondary antibodies (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse Ig) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Immunoblot analysis

Human lung tissues (control and severe COPD groups) were thawed and homogenized in RIPA buffer using a Bullet Blender (next advance). Samples were centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 12,000G and resuspended in protein loading buffer. For western blot, about 30 ug of proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE gel and transferred into a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked and incubated with primary antibodies and the appropriated secondary antibody HRP conjugated. The signal was acquired with Chemi‐Doc MP (Bio‐Rad) using WesternBright Sirius HRP substrate (advansta).

ELISA for IGFBP5

The IGFBP5 Human ELISA Kit was purchased from Thermal Fisher Scientific. Serum IGFBP5 levels were measured from 40 control smokers and 40 smokers with COPD according to the vendor’s instructions.

Gene Ontology enrichment and GSEA

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was used to identify similarities with previously published emphysema and severity signatures [28]. The gene ontology biological process enrichment was done in R with the ClusterProfiler package [29], and the ontologies were summarized and visualized with the Revigo package [30].

Results

-

Single cell RNA sequencing reveals 17 distinct cell clusters from human lungs with severe COPD.

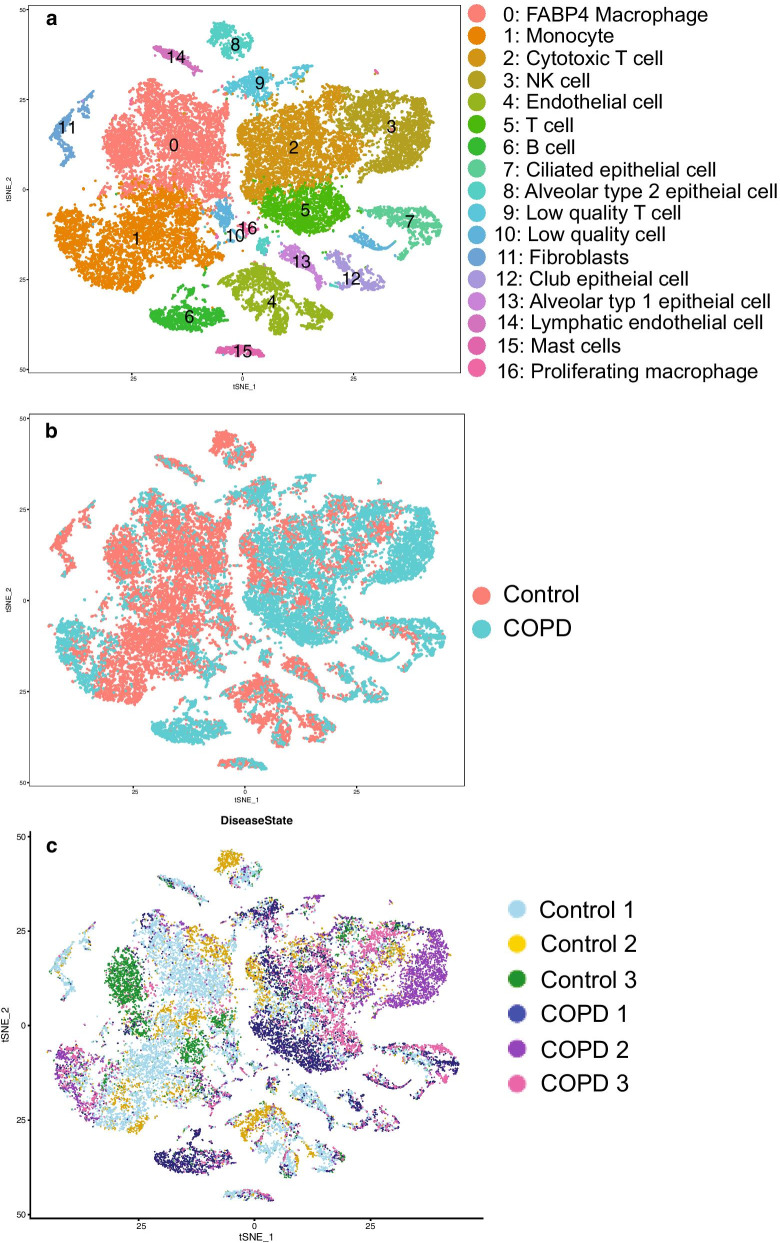

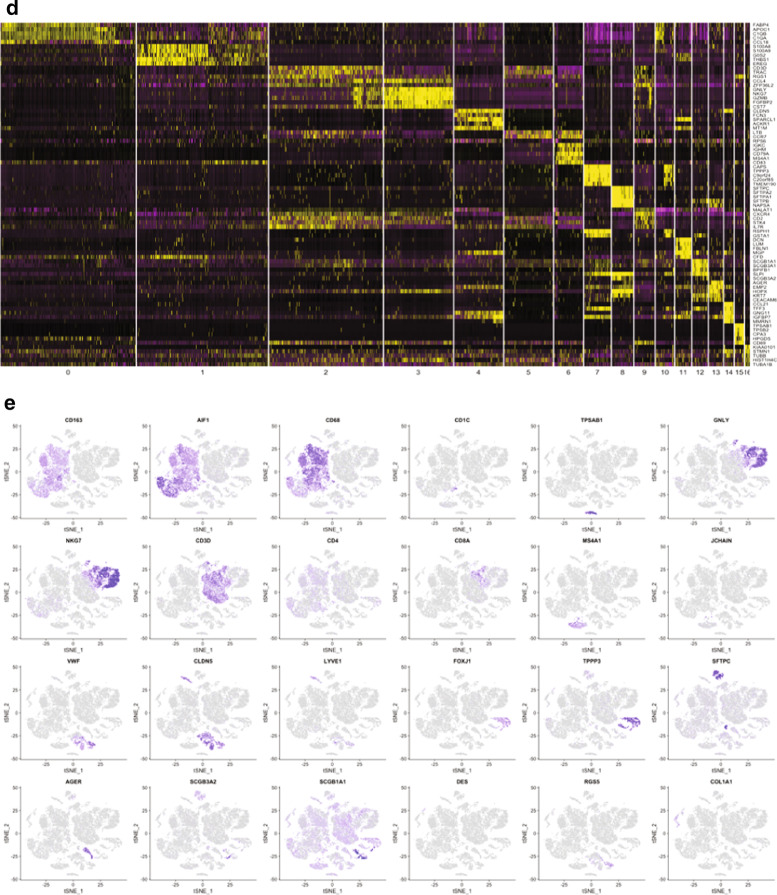

We conducted single cell transcriptomic analysis of all cells obtained from the whole parenchymal lung tissue of three nonsmokers without underlying lung disease and three patients with severe COPD (demographic data: Table 1). Pathology with H&E staining confirmed the presence of moderate to severe emphysematous changes in all three COPD patients (see Additional file 8: Figure S1). We examined a total of 29,961 cells from six subjects (3914–5920 cells/sample). All the samples were pooled and analyzed together to gain the power to detect rare cell types as previously described [24]. t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) plots were generated using statistically significant principal components and cells were clustered using an unbiased graph-based clustering algorithm (smart local moving [SLM] clustering), which identified 17 distinct types of cells (Fig. 1a). Cells from disease conditions and the individual subjects were indicated in different colors (Fig. 1b, c, respectively). SLM clustering was performed according to the distinct gene expression patterns based on various cell types in the lung (Fig. 1d). The cell clusters that cannot be reliably classified due to fewer unique molecular identifiers were referred as “low quality” cells. Cell clusters were predominantly identified as: FABP4 as a cell cluster of FABP4 macrophages (#0); S100A8 as a cluster of monocytes (#1); CD3D as cytotoxic T cells (#2); GNLY as NK cells (#3); CLDN5 as endothelial cells (#4); LTB as T cells (#5); IGKC as B cells (#6); CAPS as ciliated epithelial cells (#7); SFTPC as alveolar type 2 epithelial (AT2) cells (#8); MALAT1 as low quality T cells (#9); RSPH1 as low quality cells (#10); DCN as fibroblasts (#11); SCGB1A1 as club epithelial cells (#12); AGER as alveolar type 1 epithelial (AT1) cells (#13); CCL21 as lymphatic endothelial cells (#14); TPSAB1 as mast cells (#15); KIAA0101 as proliferating macrophages (#16). These and other markers provided strong transcriptome signatures for each cell cluster (see Additional file 1: Table S1, shown graphically in feature plots (Fig. 1e). The prevalence of individual cell types between normal nonsmokers and patients with COPD is shown in Table 5. None of the differences in the abundance of individual cell types between normal nonsmokers and COPD patients reached statistical significance (Wilcoxon). However, a trend existed for decreased percentages of macrophages, endothelial cells, AT2 cells, and fibroblasts in the COPD lungs.

-

Gene expression in 17 individual types of cells in severe emphysematous lungs.

For each cluster, the differential gene expression among the cells of the three COPD patients vs. the controls was computed using a Wilcoxon test. This analysis identified the number of differentially expressed genes per cluster when applying the filter of log fold change >|0.4| and FDR = 0.05 (Additional file 2: Table S2). Interestingly, the major populations showing the largest differences in gene expression were: monocytes, macrophages, low quality cells, ciliated epithelial cells, T cells, AT2 cells, and NK cells (Table 5). Most gene expression changes corresponded to an increased transcription (up-regulation) in patients with COPD (Table 5).

-

The Gene Ontology enrichment Gene expression in 17 individual types of cells from severe emphysematous lungs.

Next, we performed the functional enrichment with the upregulated or downregulated genes in COPD for each population for GO biological processes (Additional file 3: Table S3 and Additional file 4: Table S4). Results for the upregulated genes in COPD (i.e., macrophages, monocytes, ciliated epithelial cells and NK cells), have been summarized with Revigo and are shown as Treemaps (Additional file 8: Figures S2–S5). Of note, these four individual cell types shared ontologies related to the activation of T cells, defense response and three of them (not macrophages) also presented ontologies related to the viral life cycle.

-

Single cell contribution to the 127 emphysema-related gene signatures.

Next, we identified how the transcriptomic changes of each cell type contribute to the previously described 127 gene signatures of emphysema reported by Campbell et al. [23]. We computed the overlap using GSEA (Table 6). Three individual cell types were enriched with a nominal p value < 0.05 and an FDR < 0.1 (i.e., ciliated epithelial cells, cytotoxic T cells, and low quality T cells). The genes in the core enrichment for these three individual cell types and the values of differentially expressed genes in Campbell’s data set are shown in Additional file 5: Table S5. EPAS1, QKI and STOM were differentially expressed core genes in all three-cell types (Additional file 1: Table S5).

As a complementary analysis, we showed which individual cell types differentially expressed the 127 emphysema related genes (Additional file 6: Table S6 and Additional file 8: Figure S6). FCN3, RTN4 and CCR7 were differentially expressed in a total of five individual cell types, and EPAS1, QKI and STOM in the four individual cell types. The individual cell types with more differentially expressed genes were: monocytes (n = 10), AT2 cells (n = 9), macrophages (n = 8), ciliated cells (n = 5), and T cells (n = 5).

-

Comparison with severe airflow limitation genes.

Next, we determined whether the gene expression changes observed in the individual cell types represent the previously identified gene signatures in whole lung tissue of patients with severe airflow limitation. To achieve this, we assessed the enrichment with GSEA of the individual cell types with the differentially expressed genes between n = 17 non-smokers and n = 30 patients with GOLD stage 4 obtained from LTRC (GSE47460, GPL14550). Overall, the enrichment in all individual cell types appeared to be consistent with the genes differentially expressed in whole lung tissue. However, the enrichment was significant at a nominal p value for only four individual cell types (mast cells, proliferating macrophages, monocytes, and FBPB4 macrophages) (Table 7). The full list of genes differentially expressed in the LTRC and differentially expressed in the individual cell clusters is shown in Additional file 7: Table S7.

Our analysis identified several genes expressed in a distinct cell types that were previously reported to be differentially expressed in lung tissue homogenates according to the severity of airflow limitation [14, 31]. These genes are FGG (AT2 cells), CCL19 (monocytes), PLA2G7 (macrophages), HP (macrophages), TNFSF13B (monocytes) and FCRLA (B cells). In addition, following genes were differentially expressed in several individual cell types: S100A10 (n = 7), RPS10, GNG11, and CAV1 (n = 6), S100A6 (n = 5), and AGER (n = 4).

-

Quantifying protein levels of some genes significantly altered between normal and COPD lungs.

To determine whether significantly altered genes between normal and COPD lungs also correlate with the related protein levels, whole parenchymal lung tissues from non-smokers without COPD (n = 5 per group) and former-smokers with COPD GOLD stage 3 or 4 (n = 6 or 7 per group) were evaluated for protein expression of QKI, STOM, and EPAS1 by immunoblot analysis. We also included IGFBP5 (insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5), which was primarily expressed in three-cell types (ciliated cells, fibroblasts, and lymphatic endothelial cells). Although IGFBP5 was significantly upregulated in only ciliated cells of COPD lungs relative to controls (p = 0.029), given a known genetic association of IGFBP5 with COPD [32] and a potential application as a serum biomarker in patients with COPD, we added IGFBP5 to this analysis.

Consistent with altered gene expression, QKI and IGFBP5 protein levels were significantly increased in the COPD lungs relative to non-smokers (Fig. 2a, b), but neither STOM nor EPAS1 protein levels were altered (Additional file 8: Figure S7A). Further, we determined whether QKI and IGFBP5 gene expressions in whole lung tissue correlated with emphysema severity. QKI expression appeared to decrease according to % emphysema (n = 208; p = 0.0854), whereas, IGFBP5 expression significantly increased according to % emphysema (p = 0.0150). Since IGFBP5 is an excretory protein, we measured the serum levels of IGFBP5 in smokers with or without COPD (n = 40, each group), but detected no significant differences between the two group (Additional file 8: Figure S7B). These results suggest that some of the significantly altered genes in COPD lungs identified by scRNA seq indeed correlate with the individual protein levels in the whole lung tissue.

Fig. 1.

Single cell RNA sequencing reveals 17 distinct cell clusters from human lungs with severe COPD. a. scRNA sequencing was conducted using lung parenchymal tissues obtained from three nonsmoking normal subjects and three patients with severe COPD. t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) blots were shown using statistically significant principal components and cells were clustered using an unbiased graph-based clustering algorithm (smart local moving [SLM] clustering, which in total identified 17 distinct types of cells, distinguished by color. b Cells from disease conditions were indicated by different colors. c Cells from individual subjects were indicated by different colors. d SLM clustering was made according to distinct gene expression patterns based on various cell types in the lung. e SLM clustering is shown graphically in feature plots

Table 5.

Identified clusters, number of differentially expressed genes in case vs. control, mean % of cells belonging to this cluster both in cases and controls, fold change differences between cluster percentage and the p value of the comparison of the cluster frequency in cases vs. controls both with t-test and Wilcoxon-test

| Cluster | Population | # DE genes | Up | Down | Control % of cells | COPD % of cells | Fold change | p value (t.test) | p value (Wilcox) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | FABP4 Macrophages | 868 | 620 | 248 | 27.97 ± 10.74 | 5.15 ± 1.57 | 5.43 | 0.02 | 0.057 |

| 1 | Monocytes | 1499 | 677 | 822 | 23.80 ± 12.90 | 11.24 ± 4.84 | 2.12 | 0.18 | 0.23 |

| 2 | Cytotoxic T cells | 539 | 165 | 374 | 11.18 ± 6.48 | 21.86 ± 9.80 | − 1.96 | 0.14 | 0.11 |

| 3 | NK cells | 431 | 233 | 198 | 3.85 ± 2.89 | 22.14 ± 27.41 | − 5.75 | 0.23 | 0.4 |

| 4 | Endothelial | 242 | 185 | 57 | 9.17 ± 3.90 | 2.37 ± 0.52 | 3.87 | 0.03 | 0.057 |

| 5 | T cells | 213 | 64 | 149 | 2.11 ± 1.00 | 11.68 ± 9.02 | − 5.54 | 0.08 | 0.23 |

| 6 | B cells | 153 | 30 | 123 | 0.99 ± 0.59 | 6.80 ± 7.95 | − 6.84 | 0.19 | 0.23 |

| 7 | Ciliated | 590 | 433 | 157 | 1.84 ± 0.98 | 6.18 ± 4.36 | − 3.35 | 0.10 | 0.23 |

| 8 | AT2 | 476 | 34 | 442 | 4.12 ± 2.52 | 0.96 ± 0.32 | − 4.28 | 0.09 | 0.057 |

| 9 | Low quality T cells | 41 | 14 | 27 | 1.75 ± 0.68 | 3.71 ± 2.07 | − 2.12 | 0.13 | 0.11 |

| 10 | Low quality cells | 596 | 369 | 227 | 2.02 ± 0.95 | 2.83 ± 1.50 | − 1.40 | 0.41 | 0.63 |

| 11 | Fibroblasts | 96 | 87 | 9 | 3.17 ± 1.62 | 0.27 ± 0.07 | 11.60 | 0.03 | 0.057 |

| 12 | Club cells | 98 | 70 | 28 | 1.35 ± 0.81 | 2.72 ± 2.16 | − 2.02 | 0.29 | 0.63 |

| 13 | AT1 | 68 | 59 | 9 | 2.60 ± 1.91 | 0.46 ± 0.36 | 5.71 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| 14 | Lymphatic-endothelial | 27 | 20 | 7 | 1.93 ± 1.10 | 0.33 ± 0.29 | 5.85 | 0.06 | 0.23 |

| 15 | Mast cells | 32 | 25 | 7 | 1.32 ± 0.79 | 0.91 ± 0.24 | 1.44 | 0.44 | 0.63 |

| 16 | Proliferative macrophages | 111 | 55 | 56 | 0.84 ± 0.35 | 0.39 ± 0.25 | 2.17 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

Table 6.

GSEA enrichment of the different clusters with the 127 gene signature

| Cluster | ES | NES | NOM p-val | FDR q-val | FWER p-val |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciliated | 0.33 | 1.33 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| Cytotoxic T | 0.33 | 1.29 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| Low quality T cells | 0.47 | 1.29 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.00 |

| AT2 | 0.39 | 1.27 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.04 |

| Fibroblasts | 0.40 | 1.31 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.05 |

| T cells | 0.31 | 1.17 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.05 |

| Proliferative macrophages | 0.37 | 1.23 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.05 |

| B cells | − 0.24 | − 0.97 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.09 |

| NK | 0.31 | 1.05 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.14 |

| AT1 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 0.22 |

| Monocytes | 0.20 | 0.84 | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.36 |

| Macrophages | − 0.22 | − 0.92 | 0.70 | 0.83 | 0.37 |

| Club | − 0.20 | − 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.88 | 0.39 |

| Low quality | − 0.25 | − 0.78 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 0.43 |

| Endothelial | − 0.17 | − 0.53 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.44 |

| Mast cells | 0.28 | 0.77 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 0.47 |

Table 7.

GSEA enrichment results of the different clusters with the differential gene expression of the LTRC (COPD Gold 4 vs. non-smokers)

| Size | ES | NES | NOM p-value | FDR q-value | FWER p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mast cells | 70 | − 0.62 | − 1.72 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| Proliferating macrophages | 164 | − 0.56 | − 1.71 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Monocytes | 103 | − 0.63 | − 1.58 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| FBPB4 macrophages | 27 | − 0.61 | − 1.46 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.23 |

| AT2 | 80 | − 0.56 | − 1.56 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.14 |

| B cells | 48 | − 0.47 | − 1.42 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.28 |

| Club | 83 | − 0.51 | − 1.38 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.32 |

| Fibroblasts | 245 | − 0.49 | − 1.45 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.24 |

| Cytotoxic T cells | 30 | − 0.54 | − 1.33 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.39 |

| Low quality T cells | 126 | − 0.45 | − 1.38 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.33 |

| Ciliated | 55 | − 0.48 | − 1.17 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.57 |

| T cells | 36 | − 0.42 | − 1.14 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.60 |

| Endothelial | 94 | − 0.36 | − 0.93 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.76 |

| AT1 | 221 | − 0.12 | − 0.56 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.92 |

| NK cells | 23 | − 0.21 | − 0.55 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.92 |

Discussion

This study uses scRNA seq from human lung homogenate in order to identify the specific cell types driving gene expression changes found in bulk RNA sequencing of patients with severe emphysema and airway obstruction. We found that: (1) t-SNE and clustering of scRNA-seq data identified a total of 17 distinct populations based on predetermined markers per cell type. Monocytes, macrophages, ciliated cells and low quality cells exhibited more differentially expressed genes in cases vs. controls relative to the other cell types; (2) GSEA revealed that the populations contributing most to the previously reported emphysema signature were ciliated cells, cytotoxic T cells and low quality T cells. While in the severe COPD LTRC signature, the populations enriched by GSEA were proliferating macrophages, mast cells, AT2 cells and monocytes; (3) key COPD associated genes were found to be expressed by specific cell types:. FGG (AT2 cells), CCL19/TNFSF13B (monocytes) and PLA2G7 (macrophages); (4) We verified the expression of some of the specific scRNA seq differentially expressed genes at the protein level as well (i.e. QKI and IGFBP5).

Previous studies

Although the scRNA seq methodology has been applied to the profiling of lung tissue of patients with IPF [33–35], this is the first study to our knowledge which profiles the lung tissue of patients with COPD. In relation to severe COPD and emphysema, several studies have reported the transcriptomic profile of lung tissue homogenates [14, 31], but the scRNA seq has several advantages over the previously used RNA seq methods. First, scRNA seq can determine which cell types are responsible for the significant transcriptomic changes in a disease process (e.g., the emphysematous and/or airflow limitation signature). Second, scRNA seq can detect alteration of the cell composition as opposed to the whole cell RNA-seq. Third, scRNA seq may uncover an important molecular pathway unique to a specific cell type that contributes to the development of the disease.

Interpretation of novel findings

We identified 17 cell subtypes in the lung tissue of patients with severe COPD and non-smoking controls. In relation to cell composition, differences were not statistically significant, but in agreement with previous reports. We observed an overall increase of immune cell types (T, NK and B cells) and a decrease in structural cells (Fibroblasts, AT2 cells and endothelial cells) [36]. However, the sampling effects inherent to scRNA seq may have contributed to the skewed proportion of distinct cell populations. Interestingly, we found that the genes up-regulated in the cell types with more differential expression (monocytes, macrophages, ciliated cells, cytotoxic T cells and AT2 cells) were related to T cell activation, antigen presentation and signaling. The role of cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) in severe COPD has long been recognized [36–38] and emphysema has been proposed to be associated with a Th1 response activated by infiltrating ILC1, NK, and LTi cells [39]. Here, we expand these findings by showing that antigen presenting cells (macrophages, monocytes and AT2 cells) are also involved in T cell activation. Interestingly, the viral related ontologies appeared to be enriched in these cell types as well as in ciliated epithelial cells and NK cells. Further work profiling the virome in parallel with cellular phenotyping may complement these findings.

In relation to the previously described 127 emphysema gene signature, our GSEA analysis showed an enrichment of genes differentially expressed by ciliated and T cells (cytotoxic and of low quality), suggesting an active involvement of T cells in the emphysematous tissue remodeling and accumulation of primary cilia [39, 40]. Some of the genes associated with the homing of B cells and previously identified by homogenate tissue profiling (i.e. CCL19, TNFSF13B) [23, 31] were found in the current study to be expressed by macrophages and monocytes. Yet in the current analysis, the increase in B cells was observed in 2 of the 3 severe COPD samples, and the genes hyper expressed by the severe COPD B cells were related to the T cell activation in concordance with previous works [31]. Upregulation of gene expression for fibrinogen (FGG) is a well-recognized biomarker in COPD [41] and is produced by AT2 cells. Fibrinogen has a well-known role in both innate and T cell mediated adaptive immune responses to bacteria [42]. Similar to these previous findings, our analysis showed an upregulation of genes related to the antigen presentation in AT2 cells, suggesting a role in the stimulation and perpetuation of the observed immune response in the lung. AGER, another well-known gene associated with COPD [43], was upregulated in four cell types in our analysis (macrophages, monocytes, low quality T cells and B cells) that are associated with immune response, suggesting a role of the RAGE axis in the chronic immune infiltrate observed in severe COPD/emphysema. In our analysis, club cells that express the COPD associated CC-16 protein, were found to have altered mRNA catabolism and toxic substance response pathways. Further investigation is warranted to determine the impact of these alterations in cell functionality [44].

Finally, in this study, we attempted to verify whether differences in gene expression correlated with differential protein content in the cellular populations derived from COPD and normal lungs. Among several common targets, we found that COPD lungs exhibit decreased protein levels of QKI and increased protein levels of IGFBP5.

Our scRNA seq data show that QKI is expressed abundantly in myeloid cells, endothelial cells, and AT1 cells, whereas IGFBP5 is expressed in ciliated cells, fibroblasts, and lymphatic endothelial cells relative to the other types of cells. QKI, a KH domain containing RNA binding protein, regulates versatile mRNA metabolism—splicing, export, stability, and protein translation [45]. Loss-of-function mutations in QKI disturb myelination and cause embryonic lethality [46]. QKI has been implicated in various disease processes, including atherosclerosis [47], tumorigenesis [48], and fibrosis [49]. IGFBP5, insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5, is one of the six proteins of the IGFBP family [50]. IGFBP proteins bind IGF-I/II and regulate their bioavailability and downstream signaling. In addition, IGFBP proteins can regulate cell growth and survival independent of IGF-I/II [50]. In particular, IGFBP5 plays a causal role in the induction of cellular senescence and inflammation [51], which may be linked to pulmonary fibrosis [52]. Further, an intergenic SNP of IGFBP5 (rs6435952) associates with airway obstruction [32]. Although IGFBP5 is a secretory protein [53], there was no significant change in the serum levels of IGFBP5 in COPD patients compared with control smokers. However, there may be excretory impairment of IGFBP5 protein in the COPD lung which remains to be determined in future studies. An in vivo animal study will be necessary to elucidate causal roles for QKI and IGFBP5 in the development of smoking-induced COPD.

Limitations

Several scRNA seq studies using the human lung tissue were conducted and profiled approximately 3000 to 6000 per sample [35, 54, 55]. The range of cell number per sample analyzed in this study are pretty comparable to the previous studies. However, the main limitation of this study is the sample size as we have analyzed three control subjects without underlying lung disease and three patients with severe COPD. We used the nonsmoking control libraries which were included in another dataset we published [35]. Two and one of the control subjects did not match with respect to age and sex with the COPD subjects, respectively. The potential effects of age and sex differences between the control and COPD subjects on the data analysis could be substantial; however, it is difficult to determine as a result of the small sample size used in this study.

Active cigarette smoke exposure has the major influence on gene expression [56]. Furthermore, it is known that smoke dose exposure and duration and length of cessation also affect gene expression. Accordingly, to control for an active smoking effect, included in the three COPD subjects are a former smoker who had stopped smoking for at least 6 months. Due to this, there was no significant increase either in the ALDH3A1 or CYP1A1 genes (known transcriptional targets of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor robustly upregulated by CS [56]) in the lungs of COPD subjects relative to the controlled nonsmoking subjects. In addition, our findings are not representative of the COPD heterogeneity and we will need to increase the sample size with appropriately controlled smoking subjects (i.e., matching age, sex, smoking dose and time and cessation period) to address this open issue in future investigations. Notwithstanding this limitation, the main focus of this work has been to use the generated data to explore which cell types express the key genes previously shown to be associated with COPD and emphysema.

Conclusions

We identified ciliated and CD8+ T cells as prominent cell types associated with the 127 gene signature associated with emphysema. Our findings support a prominent role of the immune response in severe COPD, with the implication of structural and antigen presenting cells in its homing and perpetuation. Finally, QKI and IGFBP5 are identified as potential COPD biomarkers, whose both gene and protein expression are significantly altered in COPD lungs relative to normal lungs. The causal role of QKI and IGFBP5 in the development of COPD/emphysema will need further investigation.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Transcriptomic markers per cell type (top 100 genes per cluster).

Additional file 2: Table S2. DE genes per cell type, log FC|0.4| and FDR.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Biological process gene ontology enrichment in genes upregulated in each cluster in COPD.

Additional file 4: Table S4. Biological process gene ontology enrichment in genes downregulated in each cluster in COPD.

Additional file 5: Table S5. Genes present in the GSEA core enrichment with the 127 emphysema gene signature.

Additional file 6: Table S6. Genes from the 127 gene signature differentially expressed by cell type.

Additional file 7: Table S7. Genes from the sever COPD signature (LTRC) differentially expressed by cell type.

Additional file 8: Figure S1. Lung histology of three COPD cases (hematoxylin & eosin staining). Figure S2. Revigo summary of biological processes enriched in Macrophages. Figure S3. Revigo summary of biological processes enriched in Monocytes. Figure S4. Revigo summary of biological processes enriched in Ciliated epithelial cells. Figure S5. Revigo summary of biological processes enriched in NK cells. Figure S6. Differentially expressed genes in the 127 gene signature per type of cell, per patient. Figure S7. A: Immunoblot analysis for STOM, EPAS1, RTN4 (controls vs. COPD GOLD stage 4). B: Serum IGFBP5 measurements in controls (n = 40) and COPD cases (n = 40).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AGER

Advanced glycosylation end product receptor

- AT1

Alveolar type 1 epithelial

- AT2

Alveolar type 2 epithelial

- CAPS

Calcyphosine

- CC-16

Club cell protein 16

- CCL19

C–C motif chemokine ligand 19

- CCL21

C–C motif chemokine ligand 21

- CCR7

C–C motif chemokine receptor 7

- CLDN5

Claudin 5

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CS

Cigarette smoke

- DCN

Decorin

- EPAS1

Endothelial PAS domain protein 1

- ECL

Enhanced luminol-based chemiluminescent

- ELISA

Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay

- FABP4

Fatty acid binding protein 4

- FCN3

Ficolin 3

- FCRLA

Fc receptor like A

- FDR

False discovery rate

- FEV1

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FGG

Fibrinogen gamma chain

- GNG11

G protein subunit gamma 11

- GNLY

Granulysin

- GO

Gene Ontology

- GOLD

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

- GSEA

Gene set enrichment analysis

- LTB

Lymphotoxin beta

- H&E

Hematoxylin and eosin

- HP

Haptoglobin

- HPRT1

Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1

- HRP

Horseradish peroxidase

- IGFBP5

Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5

- IGKC

Immunoglobulin Kappa Constant

- ILC1

Innate lymphoid cell 1

- IPF

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- LEC

Lung epithelial cell

- LGRC

Lung Genomics Research Consortium

- LTi

Lymphoid tissue inducer

- LTRC

Lung Tissue Research Consortium

- MALAT1

Metastasis Associated Lung Adenocarcinoma Transcript 1

- NK cell

Natural killer cell

- PLA2G7

Phospholipase A2 Group VII

- QKI

KH domain containing RNA binding protein

- RAGE

Receptor for advanced glycation endproducts

- RIPA

Radioimmunoprecipitation assay

- RPS10

Ribosomal protein S10

- RSPH1

Radial spoke head component 1

- RTN4

Reticulon 4

- S100A6

S100 calcium binding protein A6

- S100A8

S100 calcium binding protein A8

- S100A10

S100 calcium binding protein A10

- SCCOR

COPD specialized center for clinically oriented research

- SCGB1A1

Secretoglobin Family 1A Member 1

- scRNA seq

Single-cell RNA sequencing

- SDS-PAGE

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SFTPC

Surfactant protein C

- SLM

Smart local moving

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- STOM

Stomatin

- TGFβ

Transforming growth factor beta

- TNFSF13B

TNF superfamily member 13b

- TPSAB1

Tryptase alpha/beta 1

- t-SNE

T-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding

Authors' contributions

MR, RL, RF, and TN conceived and designed the experiments; TS, XL, RV, PS, GN, JS, YZ performed the experiments; TS, XL, TK, GN, and RF collected and analyzed the data; CZ, PS, YZ, FS, MR, JM, and TN provided reagents/materials/data analysis; XL, TS, CZ, PS, MR, PS, DC, RM, FS edited the manuscript; XL, GN, RF, and TN wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL149719); Merit Review Award from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (CX001048 and CX000105), AHA transformational Grant to TN (19TPA34830061) and Miguel Servet Fellowship from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CP16/00039, PI17/00369) to RF. These funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its additional information files].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All research involving human subjects was approved by the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board (#14010265 and 19090239). Written informed consent was obtained from all study subjects. The use of human cadaveric tissue and decedent medical records for this study was approved by the Committee for Oversight of Research and Clinical Training Involving Decedents (CORID) (#765). The written consent was obtained either via body donation registration, autopsy authorization, or provided by next of kin or legal representatives.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no completing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rosa Faner and Toru Nyunoya contributed equally to this work

References

- 1.Brown DW. Smoking prevalence among US veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(2):147–149. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1160-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han MK. Update in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 2010. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(10):1311–1315. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201102-0280UP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guarascio AJ, Ray SM, Finch CK, Self TH. The clinical and economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the USA. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:235–245. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S34321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogg JC. Pathophysiology of airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2004;364(9435):709–721. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16900-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim V, Criner GJ. Chronic bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(3):228–237. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201210-1843CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez FJ, Foster G, Curtis JL, Criner G, Weinmann G, Fishman A, DeCamp MM, Benditt J, Sciurba F, Make B, et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with emphysema and severe airflow obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(12):1326–1334. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200510-1677OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minai OA, Benditt J, Martinez FJ. Natural history of emphysema. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(4):468–474. doi: 10.1513/pats.200802-018ET. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrow JD, Chase RP, Parker MM, Glass K, Seo M, Divo M, Owen CA, Castaldi P, DeMeo DL, Silverman EK, et al. RNA-sequencing across three matched tissues reveals shared and tissue-specific gene expression and pathway signatures of COPD. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1032-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faner R, Morrow JD, Casas-Recasens S, Cloonan SM, Noell G, Lopez-Giraldo A, Tal-Singer R, Miller BE, Silverman EK, Agusti A, et al. Do sputum or circulating blood samples reflect the pulmonary transcriptomic differences of COPD patients? A multi-tissue transcriptomic network META-analysis. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12931-018-0965-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spira A, Beane J, Pinto-Plata V, Kadar A, Liu G, Shah V, Celli B, Brody JS. Gene expression profiling of human lung tissue from smokers with severe emphysema. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31(6):601–610. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0273OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamontagne M, Timens W, Hao K, Bosse Y, Laviolette M, Steiling K, Campbell JD, Couture C, Conti M, Sherwood K, et al. Genetic regulation of gene expression in the lung identifies CST3 and CD22 as potential causal genes for airflow obstruction. Thorax. 2014;69(11):997–1004. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusko RL, Brothers Ii JF, Tedrow J, Pandit K, Huleihel L, Perdomo C, Liu G, Juan-Guardela B, Kass D, Zhang S, et al. Integrated genomics reveals convergent transcriptomic networks underlying COPD and IPF. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:948–960. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201510-2026OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faner R, Cruz T, Casserras T, Lopez-Giraldo A, Noell G, Coca I, Tal-Singer R, Miller B, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Spira A, et al. Network analysis of lung transcriptomics reveals a distinct B cell signature in emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:1242–1253. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1311OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrow JD, Zhou X, Lao T, Jiang Z, DeMeo DL, Cho MH, Qiu W, Cloonan S, Pinto-Plata V, Celli B, et al. Functional interactors of three genome-wide association study genes are differentially expressed in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease lung tissue. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44232. doi: 10.1038/srep44232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Obeidat M, Nie Y, Fishbane N, Li X, Bosse Y, Joubert P, Nickle DC, Hao K, Postma DS, Timens W, et al. Integrative genomics of emphysema associated genes reveals potential disease biomarkers. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;57:411–418. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0284OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnes PJ, Shapiro SD, Pauwels RA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: molecular and cellular mechanisms. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(4):672–688. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00040703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnes PJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(1):16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stockley RA. Neutrophils and protease/antiprotease imbalance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5 Pt 2):S49–52. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.supplement_1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rangasamy T, Cho CY, Thimmulappa RK, Zhen L, Srisuma SS, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Petrache I, Tuder RM, Biswal S. Genetic ablation of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(9):1248–1259. doi: 10.1172/JCI200421146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundar IK, Yao H, Rahman I. Oxidative stress and chromatin remodeling in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and smoking-related diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(15):1956–1971. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito K, Barnes PJ. COPD as a disease of accelerated lung aging. Chest. 2009;135(1):173–180. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmad T, Sundar IK, Lerner CA, Gerloff J, Tormos AM, Yao H, Rahman I. Impaired mitophagy leads to cigarette smoke stress-induced cellular senescence: implications for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. FASEB J. 2015;29(7):2912–2929. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-268276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell JD, McDonough JE, Zeskind JE, Hackett TL, Pechkovsky DV, Brandsma CA, Suzuki M, Gosselink JV, Liu G, Alekseyev YO, et al. A gene expression signature of emphysema-related lung destruction and its reversal by the tripeptide GHK. Genome Med. 2012;4(8):67. doi: 10.1186/gm367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabib T, Morse C, Wang T, Chen W, Lafyatis R. SFRP2/DPP4 and FMO1/LSP1 define major fibroblast populations in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(4):802–810. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satija R, Farrell JA, Gennert D, Schier AF, Regev A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(5):495–502. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macosko EZ, Basu A, Satija R, Nemesh J, Shekhar K, Goldman M, Tirosh I, Bialas AR, Kamitaki N, Martersteck EM, et al. Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell. 2015;161(5):1202–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Hoon MJ, Imoto S, Nolan J, Miyano S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(9):1453–1454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(43):15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16(5):284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Supek F, Bosnjak M, Skunca N, Smuc T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e21800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faner R, Cruz T, Casserras T, Lopez-Giraldo A, Noell G, Coca I, Tal-Singer R, Miller B, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Spira A, et al. Network analysis of lung transcriptomics reveals a distinct B-cell signature in emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(11):1242–1253. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1311OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shrine N, Guyatt AL, Erzurumluoglu AM, Jackson VE, Hobbs BD, Melbourne CA, Batini C, Fawcett KA, Song K, Sakornsakolpat P, et al. New genetic signals for lung function highlight pathways and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associations across multiple ancestries. Nat Genet. 2019;51(3):481–493. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0321-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reyfman PA, Walter JM, Joshi N, Anekalla KR, McQuattie-Pimentel AC, Chiu S, Fernandez R, Akbarpour M, Chen CI, Ren Z, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of human lung provides insights into the pathobiology of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(12):1517–1536. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201712-2410OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu Y, Mizuno T, Sridharan A, Du Y, Guo M, Tang J, Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA, Perl AT, Funari VA, Gokey JJ, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies diverse roles of epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. JCI Insight. 2016;1(20):e90558. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.90558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morse C, Tabib T, Sembrat J, Buschur KL, Bittar HT, Valenzi E, Jiang Y, Kass DJ, Gibson K, Chen W, et al. Proliferating SPP1/MERTK-expressing macrophages in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(2):1802441. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02441-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, Cherniack RM, Rogers RM, Sciurba FC, Coxson HO, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(26):2645–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saetta M, Di Stefano A, Turato G, Facchini FM, Corbino L, Mapp CE, Maestrelli P, Ciaccia A, Fabbri LM. CD8+ T-lymphocytes in peripheral airways of smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(3 Pt 1):822–826. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.3.9709027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agusti A, Hogg JC. Update on the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(13):1248–1256. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1900475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki M, Sze MA, Campbell JD, Brothers JF, 2nd, Lenburg ME, McDonough JE, Elliott WM, Cooper JD, Spira A, Hogg JC. The cellular and molecular determinants of emphysematous destruction in COPD. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):9562. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10126-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perotin JM, Coraux C, Lagonotte E, Birembaut P, Delepine G, Polette M, Deslee G, Dormoy V. Alteration of primary cilia in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(1):1800122. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00122-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duvoix A, Dickens J, Haq I, Mannino D, Miller B, Tal-Singer R, Lomas DA. Blood fibrinogen as a biomarker of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2013;68(7):670–676. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun H. The interaction between pathogens and the host coagulation system. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:281–288. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00059.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng DT, Kim DK, Cockayne DA, Belousov A, Bitter H, Cho MH, Duvoix A, Edwards LD, Lomas DA, Miller BE, et al. Systemic soluble receptor for advanced glycation endproducts is a biomarker of emphysema and associated with AGER genetic variants in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):948–957. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0247OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laucho-Contreras ME, Polverino F, Gupta K, Taylor KL, Kelly E, Pinto-Plata V, Divo M, Ashfaq N, Petersen H, Stripp B, et al. Protective role for club cell secretory protein-16 (CC16) in the development of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(6):1544–1556. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00134214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vernet C, Artzt K. STAR, a gene family involved in signal transduction and activation of RNA. Trends Genet. 1997;13(12):479–484. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(97)01269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ebersole TA, Chen Q, Justice MJ, Artzt K. The quaking gene product necessary in embryogenesis and myelination combines features of RNA binding and signal transduction proteins. Nat Genet. 1996;12(3):260–265. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Bruin RG, Shiue L, Prins J, de Boer HC, Singh A, Fagg WS, van Gils JM, Duijs JM, Katzman S, Kraaijeveld AO, et al. Quaking promotes monocyte differentiation into pro-atherogenic macrophages by controlling pre-mRNA splicing and gene expression. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10846. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mukohyama J, Isobe T, Hu Q, Hayashi T, Watanabe T, Maeda M, Yanagi H, Qian X, Yamashita K, Minami H, et al. miR-221 targets QKI to enhance the tumorigenic capacity of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2019;79:5151–5158. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chothani S, Schafer S, Adami E, Viswanathan S, Widjaja AA, Langley SR, Tan J, Wang M, Quaife NM, Jian Pua C, et al. Widespread translational control of fibrosis in the human heart by RNA-binding proteins. Circulation. 2019;140(11):937–951. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.039596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baxter RC. IGF binding proteins in cancer: mechanistic and clinical insights. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(5):329–341. doi: 10.1038/nrc3720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanada F, Taniyama Y, Muratsu J, Otsu R, Shimizu H, Rakugi H, Morishita R. IGF binding protein-5 induces cell senescence. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:53. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allan GJ, Beattie J, Flint DJ. Epithelial injury induces an innate repair mechanism linked to cellular senescence and fibrosis involving IGF-binding protein-5. J Endocrinol. 2008;199(2):155–164. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ding M, Bruick RK, Yu Y. Secreted IGFBP5 mediates mTORC1-dependent feedback inhibition of IGF-1 signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18(3):319–327. doi: 10.1038/ncb3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adams TS, Schupp JC, Poli S, Ayaub EA, Neumark N, Ahangari F, Chu SG, Raby BA, DeIuliis G, Januszyk M, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals ectopic and aberrant lung-resident cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Adv. 2020;6(28):eaba1983. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valenzi E, Bulik M, Tabib T, Morse C, Sembrat J, Trejo Bittar H, Rojas M, Lafyatis R. Single-cell analysis reveals fibroblast heterogeneity and myofibroblasts in systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(10):1379–1387. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rangasamy T, Misra V, Zhen L, Tankersley CG, Tuder RM, Biswal S. Cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in A/J mice is associated with pulmonary oxidative stress, apoptosis of lung cells, and global alterations in gene expression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296(6):L888–900. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90369.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Transcriptomic markers per cell type (top 100 genes per cluster).

Additional file 2: Table S2. DE genes per cell type, log FC|0.4| and FDR.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Biological process gene ontology enrichment in genes upregulated in each cluster in COPD.

Additional file 4: Table S4. Biological process gene ontology enrichment in genes downregulated in each cluster in COPD.

Additional file 5: Table S5. Genes present in the GSEA core enrichment with the 127 emphysema gene signature.

Additional file 6: Table S6. Genes from the 127 gene signature differentially expressed by cell type.

Additional file 7: Table S7. Genes from the sever COPD signature (LTRC) differentially expressed by cell type.

Additional file 8: Figure S1. Lung histology of three COPD cases (hematoxylin & eosin staining). Figure S2. Revigo summary of biological processes enriched in Macrophages. Figure S3. Revigo summary of biological processes enriched in Monocytes. Figure S4. Revigo summary of biological processes enriched in Ciliated epithelial cells. Figure S5. Revigo summary of biological processes enriched in NK cells. Figure S6. Differentially expressed genes in the 127 gene signature per type of cell, per patient. Figure S7. A: Immunoblot analysis for STOM, EPAS1, RTN4 (controls vs. COPD GOLD stage 4). B: Serum IGFBP5 measurements in controls (n = 40) and COPD cases (n = 40).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its additional information files].