Abstract

Background

Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and/or angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors could alter mortality from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), but existing meta-analyses that combined crude and adjusted results may be confounded by the fact that comorbidities are more common in ARB/ACE inhibitor users.

Methods

We searched PubMed/MEDLINE/Embase for cohort studies and meta-analyses reporting mortality by preexisting ARB/ACE inhibitor treatment in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Random effects meta-regression was used to compute pooled odds ratios for mortality adjusted for imbalance in age, sex, and prevalence of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease between users and nonusers of ARBs/ACE inhibitors at the study level during data synthesis.

Results

In 30 included studies of 17,281 patients, 22%, 68%, 25%, and 11% had cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. ARB/ACE inhibitor use was associated with significantly lower mortality after controlling for potential confounding factors (odds ratio 0.77 [95% confidence interval: 0.62, 0.96]). In contrast, meta-analysis of ARB/ACE inhibitor use was not significantly associated with mortality when all studies were combined with no adjustment made for confounders (0.87 [95% confidence interval: 0.71, 1.08]).

Conclusions

ARB/ACE inhibitor use was associated with decreased mortality in cohorts of COVID-19 patients after adjusting for age, sex, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. Unadjusted meta-analyses may not be appropriate for determining whether ARBs/ACE inhibitors are associated with mortality from COVID-19 because of indication bias.

Résumé

Introduction

Les antagonistes des récepteurs de l'angiotensine (ARA) et/ou les inhibiteurs de l'enzyme de conversion de l'angiotensine (IECA) feraient varier la mortalité liée à la COVID-19, mais il est possible que les méta-analyses actuelles qui combinaient les résultats bruts et ajustés soient invalidées du fait que les comorbidités sont plus fréquentes chez les utilisateurs d'ARA/IECA.

Méthodes

Nous avons effectué des recherches dans les bases de données PubMed/MEDLINE/Embase pour trouver des études de cohorte et des méta-analyses qui portent sur la mortalité associée à un traitement préexistant par ARA/IECA chez les patients hospitalisés atteints de la COVID-19. Nous avons utilisé la métarégression à effets aléatoires pour calculer les rapports de cotes regroupés de mortalité ajustés en fonction du déséquilibre de l’âge, du sexe, et de la prévalence des maladies cardiovasculaires, de l'hypertension, du diabète sucré et de l'insuffisance rénale chronique entre les utilisateurs et les non-utilisateurs d'ARA/IECA dans le cadre de l’étude durant la synthèse des données.

Résultats

Dans les 30 études portant sur 17 281 patients, 22 %, 68 %, 25 % et 11 % avaient respectivement une maladie cardiovasculaire, de l'hypertension, le diabète sucré et de l'insuffisance rénale chronique. L'utilisation des ARA/IECA a été associée à une mortalité significativement plus faible après avoir tenu compte des facteurs confusionnels potentiels (rapport de cotes 0,77 [intervalle de confiance à 95 % : 0,62, 0,96]). En revanche, la méta-analyse sur l'utilisation des ARA/IECA n'a pas été associée de façon significative à la mortalité lorsque toutes les études ont été combinées sans ajustement sur les facteurs confusionnels (0,87 [intervalle de confiance à 95 % : 0,71, 1,08]).

Conclusions

L'utilisation des ARA/IECA a été associée à la diminution de la mortalité au sein des cohortes de patients atteints de la COVID-19 après l'ajustement en fonction de l’âge, du sexe, des maladies cardiovasculaires, de l'hypertension, du diabète et de l'insuffisance rénale chronique. Les méta-analyses non ajustées peuvent ne pas permettre de déterminer si les ARA/IECA sont associés à la mortalité liée à la COVID-19 en raison du biais d'indication.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which has resulted in unprecedented global morbidity and mortality. The World Health Organization and other groups are performing numerous randomized controlled trials of vaccines and novel therapeutic agents to target SARS-CoV-2. However, the critical illness and many complications associated with COVID-19 are caused in part by the binding and inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE2) by SARS-CoV-21,2 and the consequent dysregulated host response.

SARS-CoV-2, H1N1, and H5N13 downregulate ACE2. SARS-CoV-2 is then endocytosed, and surface ACE2 is downregulated,1 thereby increasing angiotensin II (ATII, a potent vasoconstrictor) in COVID-19 because ACE2 catalyzes conversion of angiotensin II to angiotensin 1-7.4 Downregulation of ACE2 occurs in H1N1, H5N1, H7N9, and SARS5, 6, 7, 8 infection, leading to worsened lung injury in influenza models5, 6, 7 and increased viral load, disease progression, and mortality.9 Accordingly, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and ACE inhibitors are candidate therapies for COVID-19 because they block excessive angiotensin II.

There is clinical uncertainty regarding the safety and effectiveness of ARBs/ACE inhibitors for COVID-19 because of conflicting cohort studies and even conflicting meta-analyses. There is an inherent potential bias in cohort studies of use of ARBs or ACE inhibitors for COVID-19 because patients who are on ARBs or ACE inhibitors have underlying comorbidities, including chronic cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease, that increase the risk of complications and/or death from COVID-19. Accordingly, one must adjust for indication bias in patients who are or are not on ARBs or ACE inhibitors.

Some prior meta-analyses and studies found that use of ARBs and/or ACE inhibitors was not associated with altered mortality risk,10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 whereas one meta-analysis found that ACE inhibitors but not ARBs were associated with decreased COVID-19 mortality or critical illness,17 and others found that the use of ARBs or ACE inhibitors was associated with decreased mortality overall,18,19 in patients with cardiovascular disease,20 or in patients with hypertension.21, 22, 23, 24, 25 The reason for these conflicting results could be due partly to methodological differences. Several meta-analyses10,11,18,19,25 restricted their main or sensitivity analysis to studies that reported adjusted results and thus limited the number of studies that could be included. In contrast, other meta-analyses12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17,21, 22, 23, 24 have combined only crude results together or improperly combined unadjusted and adjusted results together—and thus may suffer from indication bias—and/or combined incompatible adjusted effect measures together (odds ratio [OR] and hazard ratio) to obtain the pooled estimates, which might yield biased results.

Meta-regression traditionally is used to examine the relationship between effect estimates of the included studies (eg, OR) and study-level covariates (eg, proportion of patients with hypertension in each study). Several prior meta-regression analyses17,23,26,27 have examined the effects of average age, sex distribution, or overall comorbidity prevalence of the included studies on patient outcome for ARB/ACE inhibitor users vs nonusers. A less well known use of meta-regression is to obtain pooled effect estimates adjusted for study-level covariates.28 In the current context, meta-regression provides a methodologically attractive approach to explicitly adjust the crude results for confounding, including indication bias, during data synthesis and further combine them with existing adjusted results to form a pooled adjusted estimate. To the best of our knowledge, no meta-analysis of the association of use of ARBs and/or ACE inhibitors with mortality from COVID-19 has explicitly adjusted the crude results for imbalance in comorbidities between ARB/ACE inhibitor users and nonusers and properly combined them with existing adjusted results through meta-regression.

We hypothesized that use of ARBs and/or ACE inhibitors is associated with decreased mortality from COVID-19 in analyses adjusted for underlying comorbidities.

Methods

This meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statements29 (Supplemental Table S1).

Data sources and searches

We conducted a literature search of PubMed/MEDLINE on August 19, 2020 for cohort and case-control studies that reported the frequencies of ARB or ACE inhibitor treatment and mortality in hospitalized patients infected with COVID-19 (Supplemental Appendix S1). More specifically, the studies evaluated the associations between prior use (ie, prehospitalization chronic use) of ARBs and/or ACE inhibitors in hospitalized patients infected with COVID-19. A further search of PubMed and Embase was performed on November 17, 2020 to identify meta-analyses for use of ARBs/ACE inhibitors and mortality in COVID-19 (Supplemental Appendices S1 and S2). Two authors (A.C. and T.L.) screened titles and abstracts to identify relevant studies.

Study selection

Studies were included if they provided data for at least 10 hospitalized COVID-19 patients. For the purpose of performing meta-regression, studies also need to report either (i) the frequency of ARB/ACE inhibitor use by patients, the number of deaths by ARB/ACE inhibitor usage, and the following patient characteristics by ARB/ACE inhibitor usage: age, sex, and prevalence of the comorbidities of interest (chronic cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease); or (ii) the adjusted OR of mortality for ARB/ACE inhibitor usage. We included full-text peer-reviewed articles, peer-reviewed articles published ahead of print, and letters and commentaries. Other studies meeting the inclusion criteria were identified from the references in review articles and other meta-analyses. Only articles in English were included in the final analysis. We excluded non-peer-reviewed articles, article abstracts, incomplete articles, research posters, conference abstracts, books, theses, and retracted articles.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Information on age, sex, comorbidities, ARB/ACE inhibitor usage, mortality, and adjusted OR of mortality for ARB/ACE inhibitor usage was extracted independently by 2 of the authors (AC and TL). The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale30 was used to assess the quality of the included studies. Studies with scores of ≥ 7 were regarded as high quality, 4-6 as fair quality, and < 4 as low quality.

Statistical analyses

The pooled OR of mortality for ARB/ACE inhibitor use was computed within each study type (studies reporting only crude results vs studies with results adjusted for confounders) using random effects meta-analysis based on the DerSimonian-Laird model. Publication bias was examined through visual inspection of the funnel plot for asymmetry. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by τ2, I2, and Cochran's Q test.

Random effects meta-regression was further used to compute the pooled OR by combining the results from all studies (both crude-results and confounder-adjusted studies). For studies with only crude results reported, meta-regression adjusted for the difference in average age, sex distribution, and the prevalence of comorbidities as defined by the individual studies (specifically, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease) between users and non-users of ARBs/ACE inhibitors. These 4 comorbidities were chosen because they are the most common reasons for prescribing ARBs and/or ACE inhibitors, and they are the comorbidities most commonly associated with COVID-19 and to death due to COVID-19. For confounder-adjusted studies, meta-regression did not apply any further adjustment to the reported OR.

Meta-regression examined the relationship between the degree of imbalance in mean age, gender distribution, and comorbidity prevalence of ARB/ACE inhibitor users vs nonusers and the OR for mortality of ARB/ACE inhibitor users vs nonusers. It also provided the pooled effect size adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidity. The outcome variable was the log of the OR for mortality. Studies that reported only crude results used the unadjusted OR as the outcome variable, whereas confounder-adjusted studies used the adjusted OR. The regression model included the mean age ratio, the ratio of the percentage of males, and the comorbidity prevalence ratio between the 2 groups as adjustment variables. For studies that reported adjusted results, the reported results were interpreted as if the 2 groups had been adjusted to be balanced in terms of the confounders. Even though some of the included studies did not adjust for all the variables we considered, we believe that the authors of these studies would have examined the potential confounders and adjusted for those that were imbalanced between groups to obtain the adjusted results. Thus, for the adjustment variables we considered herein, we assumed that they have a value of 1 for these studies. This assumption is essentially the same implicit assumption made when adjusted ORs are combined to form a pooled estimate in a traditional meta-analysis.

Given the number of studies available, we were able to adjust for only a limited number of confounders simultaneously before running the risk of overfitting the data.31,32 The general recommendation is that 10 to 20 studies be included for each adjustment variable31; the inclusion of 6 adjustment variables in our current analysis would require 60 to 120 studies, which exceeds this the number of studies available. Thus, as a sensitivity analysis, we conducted an additional analysis that we adjusted for only age and sex, and then 4 other separate analyses in which we adjusted for age, sex, and each of the 4 comorbidities. We further conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine the robustness of the meta-regression approach. For confounder-adjusted studies that provided patient characteristics (age, sex, and comorbidities) by ARB/ACE inhibitor usage, we used their crude data (mortality and patient characteristics) instead of the reported adjusted OR for the meta-regression analysis.

The adjusted pooled OR represented the OR for mortality if the 2 groups were to have the same mean age, sex distribution, and comorbidity prevalence and was obtained from the estimated meta-regression model by setting the mean age ratio, the male ratio, and the comorbidity prevalence ratio to 1.

Random effects meta-analysis and meta-regression were performed using the meta package in R 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Literature review

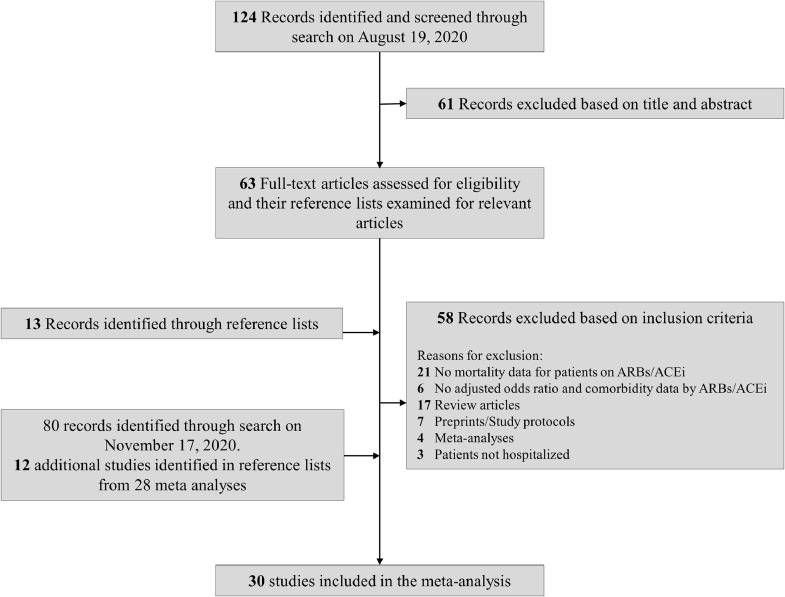

After screening titles and abstracts, 76 full-text articles and 28 meta-analyses (with literature searches covering up to October 12, 2020 [date refers to literature search performed by the authors in the 28 meta-analyses]) were reviewed (Fig. 1). We included 30 studies, with a total of 17,281 patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Thirteen studies reported only crude results for mortality, whereas 17 reported adjusted OR for mortality. Among the 13 crude-results studies, 1 reported an adjusted hazard ratio of mortality, 1 reported an OR of mortality within preexisting ARB/ACE inhibitor users for continuation vs discontinuation of treatment during hospitalization, and 3 reported adjusted ORs of the composite outcome of death or severe disease (Supplemental Table S2).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of studies of angiotensin receptor blockers/angiotensin-converting enzyme (ARBs/ACE) inhibitors in COVID-19 included in final analyses.

Comorbidities and ARB/ACE inhibitor treatment in COVID-19 patients

The baseline characteristics of patients in the included studies are shown in Table 1. Among hospitalized COVID-19 patients, 22% (n = 3161 of 14,682), 68% (n = 9919 of 14,682), 25% (n = 3621 of 14,370), and 11% (n = 1079 of 9952) had cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease, respectively. Mortality of patients taking either ARBs or ACE inhibitors was 19% (n = 847 of 4477), whereas this endpoint was reached in 15% (n = 1609 of 10,990) among those not taking ARBs/ACE inhibitors (Table 2). In 3 studies, information on continuing ARBs or ACE inhibitors was collected. Two showed that continuing ARBs or ACE inhibitors was significantly associated with decreased mortality,33,34 and one reported an OR that was substantially less than 1 but did not reach statistical significance.35

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in meta-analysis

| Number of patients |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | City/State/ Country | Total | Cardiovascular disease | Hypertension | Diabetes mellitus | Chronic kidney disease |

| With only crude results | ||||||

| Bean57 | London, United Kingdom | 1200 | 267 | 645 | 418 | 206 |

| Bravi58 | Pescara, Italy | 646 | 192 | 336 | 129 | 63 |

| Chaudhri35 | New York, USA | 300 | 96 | 133 | 74 | 34 |

| Hu36 | Zhejiang, China | 149 | 7 | 149 | 30 | 6 |

| Huang59 | Wuhan, China | 50 | 1 | 50 | 4 | — |

| Li60 | Wuhan, China | 362 | 62 | 362 | 127 | 35 |

| Meng61 | Shenzhen, China | 42 | 8 | 42 | 6 | 0 |

| Oussalah62 | Nancy, France | 147 | 38/133 | 66/133 | 38/133 | 8/133 |

| Sardu63 | Naples, Italy | 62 | 21 | 62 | 16 | 6 |

| Şenkal64 | Turkey | 156 | 55 | 156 | 64 | 15 |

| Tan65 | Wuhan, China | 100 | 18 | 100 | 28 | 8 |

| Yang66 | Wuhan, China | 251 | 45 | 126 | 55 | 4 |

| Zhang67 | Hubei, China | 1128 | 131 | 1128 | 240 | 35 |

| With adjusted results | ||||||

| Chen20 | Wuhan, China | 312 | 80 | 293 | — | — |

| Cannata34 | Lombardy, Italy | 397 | — | — | — | — |

| Covino69 | Rome, Italy | 166 | 70 | 166 | 22 | — |

| Di Castelnuovo68 | Italy | 4069 | 667 | 2057 | 793 | — |

| Felice70 | Treviso, Italy | 133 | 24 | 133 | 34 | — |

| Iaccarino42 | Italy | 1591 | 404 | 873 | 269 | 87 |

| Imam41 | Michigan, USA | 1305 | 283 | 734 | 393 | 228 |

| Jung71 | 38 countries | 324 | 108 | 211 | 95 | 49 |

| Jung72 | Seoul, Korea | 1954 | — | — | — | — |

| Lam33 | New York City, USA | 614 | 230 | 614 | 250 | 95 |

| López-Otero73 | Spain | 234 | — | — | — | — |

| Matsuzawa74 | Kanagawa, Japan | 39 | 1 | 39 | 14 | 3 |

| Negreira-Caamaño75 | Spain | 545 | 139 | 545 | 165 | 98 |

| Selçuk76 | Turkey | 113 | 37 | 113 | 48 | 13 |

| Shah77 | Georgia, USA | 531 | 116 | 425 | 228 | 77 |

| Xu78 | Wuhan, China | 101 | 13 | 101 | 19 | 2 |

| Yuan79 | Shanghai, China | 260 | 48 | 260 | 62 | 7 |

Cardiovascular disease includes coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure or heart failure, cardiopathy, ischemic heart disease, coronary heart disease, and cardiovascular disease. Dash (—) indicates no information was reported by the study.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics and outcome by ARB/ACE inhibitor usage

| Number of deaths/total | Patient characteristics—ARB or ACEi / no ARB or ACEi | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | ARB or ACEi | No ARB or ACEi | Adjusted OR for death (95% CI) | Age, y (mean)* | Male (%) | Cardiovascular disease (%) | Hypertension (%) | Diabetes mellitus (%) | CKD (%) |

| With only crude results | |||||||||

| Bean57 | 106/399 | 182/801 | — | 73/65 | 58/57 | 37/15 | 85/38 | 54/25 | 27/12 |

| Bravi58 | 87/267 | 67/379 | — | 77/64 | 58/51 | 45/19 | 100/18 | 30/13 | 14/7 |

| Chaudhri35 | 14/80 | 25/220 | — | 69/56 | 60/59 | 60/22 | 100/24 | 46/17 | 19/9 |

| Hu36 | 1/65 | 0/84 | — | 56/58 | 62/57 | 3/6 | 100/100 | 25/17 | 6/2 |

| Huang59 | 0/20 | 3/30 | — | 53/68 | 50/57 | 0/3 | 100/100 | 0/13 | — |

| Li60 | 21/115 | 56/247 | — | 65/67 | 59/49 | 23/14 | 100/100 | 37/34 | 11/9 |

| Meng61 | 0/17 | 1/25 | — | 62/62 | 47/60 | 12/24 | 100/100 | 12/16 | 0/0 |

| Oussalah62 | 10/43 | 9/104 | — | 70/63 | 65/61 | 49/19 | 86/32 | 58/14 | 9/4 |

| Sardu63 | 7/45 | 2/17 | — | 57/59 | 64/71 | 33/35 | 100/100 | 24/29 | 9/12 |

| Şenkal64 | 7/104 | 5/52 | — | 63/65 | 51/58 | 34/38 | 100/100 | 42/38 | 10/10 |

| Tan65 | 0/31 | 11/69 | — | 67/68 | 45/54 | 16/19 | 100/100 | 26/29 | 13/6 |

| Yang66 | 2/43 | 19/208 | — | 65/67 | 49/20 | 16/18 | 100/40 | 30/20 | 0/2 |

| Zhang67 | 7/188 | 92/940 | — | 64/64 | 53/54 | 15/11 | 100/100 | 23/21 | 4/3 |

| With adjusted results | |||||||||

| Chen20 | 7/81 | 66/231 | 0.136 (0.035, 0.532) | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Cannata34,† | 7/56 | 39/224 | 0.05 (0.01, 0.54) | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Cannata34,† | 32/117 | 39/224 | 1.11 (0.38, 3.45) | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Covino69 | 38/111 | 13/55 | 0.78 (0.29, 2.09) | 72/77 | 70/56 | 43/40 | 100/100 | 16/7 | — |

| Di Castelnuovo68,‡ | 116/549 | 423/2807 | 0.89 (0.67, 1.19) | — | 62/61 | 31/11 | 92/31 | 28/16 | — |

| Di Castelnuovo68,‡ | 112/542 | 423/2807 | 0.93 (0.69, 1.24) | — | 64/61 | 24/11 | 94/31 | 26/16 | — |

| Felice70 | 15/82 | 18/51 | 0.56 (0.17, 0.83) | 71/76 | 72/53 | 10/31 | 100/100 | 24/27 | — |

| Iaccarino42,§ | 63/348 | 125/1243 | 1.45 (0.99, 1.98) | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Imam41 | –/565 | –/740 | 1.20 (0.86, 1.68) | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Jung71,§ | 19/62 | 128/262 | 0.32 (0.15, 0.67) | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Jung 72 | 33/377 | 51/1577 | 0.88 (0.53, 1.44) | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Lam33 | 58/335 | 62/279 | 0.811 (0.529, 1.243) | 68/73 | 56/53 | 36/39 | 100/100 | 45/35 | 9/23 |

| López-Otero73 | 8/78 | 16/156 | 1.04 (0.16, 6.57) | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Matsuzawa74 | 2/21 | 3/18 | 0.36 (0.03, 3.53) | 71/72 | 62/78 | 0/6 | 100/100 | 52/17 | 10/6 |

| Negreira-Caamaño75 | 119/392 | 63/153 | 0.550 (0.304, 0.930) | 76/78 | 53/50 | 25/27 | 100/100 | 32/26 | 17/22 |

| Selçuk76 | 31/74 | 4/39 | 3.66 (1.11, 18.18) | 67/58 | 49/59 | 42/15 | 100/100 | 42/44 | 14/8 |

| Shah77 | 38/207 | 48/324 | 0.82 (0.45, 1.50) | 64/58 | 42/40 | 24/21 | 97/69 | 56/35 | 16/13 |

| Xu78 | 11/40 | 21/61 | 0.78 (0.32, 1.93) | 67/65 | 48/56 | 13/13 | 100/100 | 20/18 | 0/3 |

| Yuan79 | 6/130 | 22/130 | 0.50 (0.07, 3.58) | 67/66 | 45/45 | 18/18 | 100/100 | 26/22 | 4/2 |

Cardiovascular disease includes coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure or heart failure, cardiopathy, ischemic heart disease, coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease. Dash (—) indicates no information was reported by the study.

ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; OR, odds ratio.

Median age is shown if mean age was not reported.

Numbers are for ARBs/ACEis continued vs no therapy in the first row for Cannata, and for ARBs/ACEis discontinued vs no therapy in the second row.

Numbers are for ACEis vs no therapy in the first row for Di Castelnuovo, and for ARBs vs no therapy in the second row.

Numbers are for ACEis vs no ACEis.

Analyses by study type

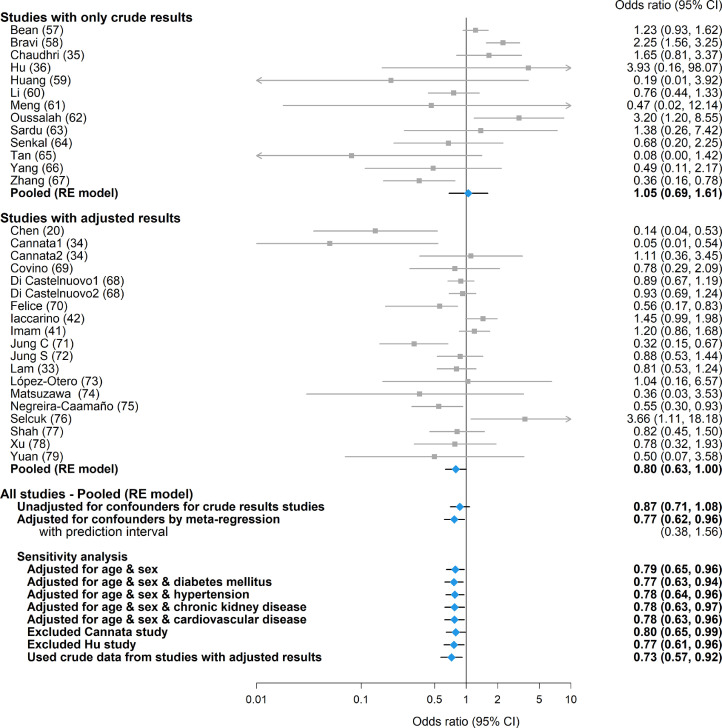

Among studies that reported only crude results (ie, with no adjustment for differences between groups in important prognostic factors) for mortality, the use of ARBs/ACE inhibitors was not significantly associated with mortality (OR 1.05 [95% confidence interval {CI}: 0.69, 1.61]; P = 0.82). The pooled OR among confounder-adjusted studies was also not significant (0.80 [95% CI: 0.63, 1.00; P = 0.055]). When combining all studies together without adjustment of confounders for the crude-results studies, the pooled OR was not significant (0.87 [95% CI: 0.71, 1.08; P = 0.21]; Fig. 2). Considerable statistical heterogeneity among studies was observed within both types of studies (τ2: 0.278 & 0.113; I2: 66.3% & 57.9%, P < 0.001 for both). No asymmetry in the funnel plot was observed within each study type (Supplemental Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of odds ratio of mortality for angiotensin receptor blockers/angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in coronavirus disease 2019. CI, confidence interval; RE, random effects.

Adjusted analyses by meta-regression

After adjusting for age, sex, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease, the use of ARBs/ACE inhibitors was associated with significantly lower mortality when all studies were combined (OR: 0.77 [95% CI: 0.62, 0.96]; P = 0.022; Fig. 2). This conclusion was unchanged in the sensitivity analyses, which adjusted for only a subset of confounders to avoid the possibility of overfitting the data. The adjusted OR of mortality from one study34 was reported separately for continuation of ARBs/ACE inhibitors vs no therapy and for discontinuation of ARBs/ACE inhibitors vs no therapy. The former was much lower compared to other included studies, and exclusion of this study from the analysis did not alter our conclusion (Fig. 2).

Nine confounder-adjusted studies also provided the distribution for age, sex, and comorbidities by ARB/ACE inhibitor usage (Table 2). Our conclusion was unchanged in the sensitivity analyses, which replaced the reported adjusted OR with crude data from these studies (Fig. 2; pooled OR was not adjusted for chronic kidney disease as it was not reported in 2 of these studies).

All studies with adjusted results were deemed to be of good quality based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (Supplemental Table S3). The quality of studies with only crude results was lower, as the crude mortality data reported could have been influenced by indication bias. Accordingly, we attempted to minimize this impact analytically through meta-regression. The exception was the Hu et al. study,36 for which the poor quality was mainly due to insufficient description of how the data were extracted. Exclusion of this study did not alter our conclusion (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The use of ARBs and the use of ACE inhibitors were associated with significantly decreased mortality in observational studies of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 after adjusting for age, sex, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. In contrast, we found that the use of ARBs and the use of ACE inhibitors were not associated with significantly decreased mortality in unadjusted analyses, possibly because patients on ARBs and patients on ACE inhibitors had more comorbidities, an imbalance that may have contaminated the crude association between ARB/ACE inhibitor use and mortality.

However, for both the analysis restricted to confounder-adjusted studies and the unadjusted analysis by meta-regression, the point estimate of the pooled OR and most of the 95% confidence interval were less than 1, suggesting that the effect may be important. There was substantial overlap in the confidence intervals for the pooled OR from the adjusted and unadjusted meta-regression, partly because the same set of data from the adjusted studies was used in both analyses. The degree of indication bias in the unadjusted meta-regression analysis clearly would depend on the number of included studies that have only crude results and the severity of indication bias in these studies. In particular, for studies that have restricted the analysis population to patients with a specific comorbidity (eg, hypertension), the degree of such bias might be lower, as the reported crude results have implicitly accounted for that particular comorbidity.

To our knowledge, no meta-analysis of ARBs and ACE inhibitors in COVID-19 has properly combined unadjusted and adjusted results by explicitly accounting for confounders during data synthesis, and so our findings must be interpreted as being hypothesis-generating. Among the included studies, 17 reported an adjusted OR of mortality, and by applying the meta-regression approach, we were able to increase the total number of studies to be included by also using data from studies that reported only crude results, to form an overall adjusted OR. Using this approach increased the statistical power of our analysis.

We emphasize that the results of observational studies of the use of ARBs and ACE inhibitors in COVID-19 are commonly confounded by indication bias. Prior research suggests that comorbidities, including chronic cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease, have a high prevalence, occurring in 30%-50% of COVID-19 patients,37, 38, 39 and these comorbidities themselves increase the risk of complications and/or death in COVID-19.40, 41, 42, 43, 44 Patients with these comorbidities are often treated with ARBs or ACE inhibitors.

Canadian hypertension guidelines recommend ARBs if ACE inhibitors are not tolerated,45 and ARBs and ACE inhibitors are very commonly prescribed (to 59% of hypertension patients,46 35% of hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease,47 and 32% of diabetes patients48). ARBs/ACE inhibitors are recommended first-line therapy in Canadian heart failure guidelines.49 They were used in 50%-70% of heart failure patients in Alberta, Canada50 and 52%-87% of heart failure patients in other countries.51, 52, 53

For all these reasons, one must adjust for indication bias in patients who are or are not on ARBs or ACE inhibitors when assessing the effect of these drugs on outcomes of COVID-19.

However, our findings are limited because a cohort association study is generally limited in addressing causation. There may be variables that we did not adjust for that confound the analyses and the results, so it is not possible to address causal relationship. For example, ARBs and ACE inhibitors may be tolerated in only patients who have less-severe disease (ie, the underlying comorbidities) and thus lower mortality of COVID-19, such that the underlying severity of disease and not the use of ARBs or ACE inhibitors caused the decreased mortality.

However, we suggest that only randomized controlled trials of ARBs and ACE inhibitors in COVID-19 can directly address causation—that is, whether ARBs and/or ACE inhibitors alter the mortality of COVID-19. There are several such randomized controlled trials that are currently ongoing, and one conference presentation54 of a randomized controlled trial (n = 659) from Brazil of stopping vs continuing ARBs and ACE inhibitors reports that ARBs and/or ACE inhibitors did not alter mortality of COVID-19 (2.7% vs 2.8%, respectively).

Among the 3 studies included in our analysis that reported comparison of continuation vs discontinuation of ARBs or ACE inhibitors, mortality was found to be lower for those who continued use of ARBs or ACE inhibitors. However, we suggest that cohort studies that address the therapeutic benefits of continuation of use of ARBs or ACE inhibitors are confounded by the fact that the decision to discontinue could be driven partly by disease progression or side effects of the treatment. Although the current recommendation by scientific societies is to not discontinue treatment, we agree that further studies are needed, such as the registered trials that randomize patients already on ARBs or ACE inhibitors to continue vs discontinue the ARB or ACE inhibitor use.

As for H1N1 and H5N1, ACE2 is the receptor for COVID-192 and SARS-CoV-2 downregulates ACE2.1 Downregulation of ACE2 by SARS-Cov-2 dysregulates the renin-angiotensin system, leading to increased plasma levels of angiotensin II in COVID-19. Plasma angiotensin II levels are increased in COVID-19 patients compared to healthy controls4 and are higher in critically ill than non–critically ill COVID-19 patients.55 Losartan (an ARB) decreases viral replication and lung injury in murine influenza pneumonia.56 Consequently, ARBs and ACE inhibitors are suitable drugs to evaluate in COVID-19 because they inhibit excess angiotensin II through 2 different mechanisms by blocking the angiotensin II type 1 receptor or inhibiting production of angiotensin II, respectively, and thus they may have different effects on outcomes of COVID-19.

We did not examine the effects of ARBs and ACE inhibitors separately in our current analysis as most included studies evaluated the 2 effects together. Based on a different set of 3 studies, one previous meta-analysis16 did not find the effect of ARBs on mortality to be different from that of ACE inhibitors, whereas another27 found that use of ARBs but not ACE inhibitors reduced mortality compared to nonuse. A recent meta-analysis that included both patients admitted vs not admitted to the hospital24 has synthesized these 2 effects separately using crude mortality data from 9 studies restricted to hypertensive patients and found no significant association between ARBs or ACE inhibitors and mortality.

There are other limitations of our study. First, as we do not have patient-level data, we could adjust only for potential confounders at the study level. Second, to avoid overfitting the data, we included only major confounding variables in the analysis. Also, for studies reporting adjusted results, not all have adjusted for the confounder variables we considered herein (ie, age, sex, and comorbidities). It is possible that the selection of adjustment variables was pre-specified based on prior knowledge rather than chosen based on observed imbalance. Thus, residual confounding may explain the association. It is also possible that our findings are subject to publication bias, although this bias should be limited given the urgency of COVID-19 research. Another limitation is that we have restricted our literature search to English-language articles and thus, findings could suffer from language bias. Finally, some of the included studies have censored the patients who were still hospitalized at the time of data extraction and reported them as survivors, which might not accurately reflect the final outcome of these patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, meta-regression analyses found that the use of ARBs/ACE inhibitors was associated with significantly decreased mortality of COVID-19 after adjusting for age, sex, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. Unadjusted meta-analyses may not be appropriate for determining whether ARBs or ACE inhibitors are associated with mortality of COVID-19 because of the potential for indication bias. In contrast, combining unadjusted and adjusted results with careful consideration of indication bias through meta-regression is methodologically sound and increases the statistical power of the analysis. Although association cannot prove causality, our findings support the need for randomized controlled trials evaluating ARBs and ACE inhibitors as therapeutic interventions to reduce mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and families who participated in the ARBs CORONA I study, which has increased our understanding of COVID-19. We also thank the many dedicated clinicians (doctors, nurses, therapists, and others) who cared for these patients and comforted their families. We also thank the investigators in the ARBs CORONA program for their ongoing support and tireless collaboration (Supplemental Appendix S3).

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research 439993.

Disclosures

Dr Russell reports patents owned by the University of British Columbia (UBC) that are related to the use of PCSK9 inhibitor(s) in sepsis and to the use of vasopressin in septic shock. Dr Russell is an inventor on these patents. Dr Russell was a founder, director, and shareholder in Cyon Therapeutics Inc. and is a shareholder in Molecular You Corp. Dr Russell reports receiving consulting fees in the last 3 years from: (i) Asahi Kesai Pharmaceuticals of America (AKPA; was developing recombinant thrombomodulin in sepsis); (ii) SIB Therapeutics LLC (developing a sepsis drug); and (iii) Ferring Pharmaceuticals (manufactures vasopressin and is developing selepressin). Dr Russell is no longer actively consulting for the following: (iv) La Jolla Pharmaceuticals (developing angiotensin II; Dr Russell chaired the data and safety monitoring board of a trial of angiotensin II from 2015 to 2017); and (v) PAR Pharma (sells prepared bags of vasopressin). Dr Russell reports having received an investigator-initiated grant from Grifols (entitled “Is HBP a mechanism of albumin's efficacy in human septic shock?”) that was provided to and administered by UBC. Dr Cheng reports grants from McGill Interdisciplinary Initiative in Infection and Immunity, and grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from GEn1E Lifesciences (as a member of the Scientific Advisory Board), and personal fees from nplex biosciences (as a member of the scientific advisory board), outside the submitted work. Dr Todd Lee receives research salary support from the Fonds de recherche du Québec—Santé. Dr Murthy receives research salary support from Innovative Medicines Canada. Dr Rewa has received consulting fees from Baxter Healthcare Inc. Dr Walley reports a patent owned by UBC that is related to the use of PCSK9 inhibitor(s) in sepsis. Dr Walley is an inventor on this patent. Dr Walley was a founder, director, and shareholder in Cyon Therapeutics Inc.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement: No formal ethics approval was required to conduct meta-analysis of published studies.

See page 973 for disclosure information.

To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit CJC Open at https://www.cjcopen.ca/ and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjco.2021.03.001.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y, Yang Y, Zhang C. Clinical and biochemical indexes from 2019-nCoV infected patients linked to viral loads and lung injury. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63:364–374. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1643-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C. Clinical Characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao S. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med. 2005;11:875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang F, Guo J, Zou Z. Angiotensin II plasma levels are linked to disease severity and predict fatal outcomes in H7N9-infected patients. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3595. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu J, Teng Y, Shang L. The effect of prior ACEI/ARB treatment on COVID-19 susceptibility and outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin infect Dis. 2020:ciaa1592. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flacco ME, Acuti Martellucci C, Bravi F. Treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs and risk of severe/lethal COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Heart. 2020;106:1519–1524. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, Yu J, Pan LY, Jiang HY. ACEI/ARB use and risk of infection or severity or mortality of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol Res. 2020;158 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grover A, Oberoi M. A systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients on angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020;7:148–157. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alamer A, Abraham I. Mortality in COVID-19 patients treated with ACEIs/ARBs: Re-estimated meta-analysis results following the Mehra et al. retraction. Pharmacol Res. 2020;160 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caldeira D, Alves M, Gouveia E. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers and the risk of COVID-19 infection or severe disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2020;31 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patoulias D, Katsimardou A, Stavropoulos K. Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evidence for significant geographical disparities. Curr Hyperten Rep. 2020;22:90. doi: 10.1007/s11906-020-01101-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pirola CJ, Sookoian S. Estimation of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system (RAAS)-inhibitor effect on COVID-19 outcome: a meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Long C, Xiong Q. Association of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with risk of COVID-19, inflammation level, severity, and death in patients with COVID-19: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/clc.23421. 10.1002/clc.23421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasan SS, Kow CS, Hadi MA, Zaidi STR, Merchant HA. Mortality and disease severity among COVID-19 patients receiving renin-angiotensin system inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2020;20:571–590. doi: 10.1007/s40256-020-00439-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen FF, Zhong M, Liu Y. The characteristics and outcomes of 681 severe cases with COVID-19 in China. J Crit Care. 2020;60:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo X, Zhu Y, Hong Y. Decreased mortality of COVID-19 with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors therapy in patients with hypertension: a meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2020;76:e13–e14. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren L, Yu S, Xu W. Lack of association of antihypertensive drugs with the risk and severity of COVID-19: a meta-analysis. J Cardiol. 2021;77:482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2020.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Chen B, Li Y. The use of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors is associated with a lower risk of mortality in hypertensive COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2021;93:1370–1377. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee MMY, Docherty KF, Sattar N. Renin-angiotensin system blockers, risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and outcomes from CoViD-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart JCardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020:pvaa138. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ssentongo AE, Ssentongo P, Heilbrunn ES. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors and the risk of mortality in patients with hypertension hospitalised for COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart. 2020;7 doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2020-001353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan CK, Huang YS, Liao HW. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and risks of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2020;76:1563–1571. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pranata R, Permana H, Huang I. The use of renin angiotensin system inhibitor on mortality in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:983–990. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravishankar N, Sreekumaran Nair N. Meta-regression: adjusting covariates during meta-analysis. Int J Adv Res. 2015;3:6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Med. 2009;6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed December 1, 2020.

- 31.Harrell FE. Springer; New York: 2015. Regression Modeling Strategies. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrer M, Cuijpers P, Furukawa TA, Ebert, DD. Doing meta-analysis in R: a hands-on guide. Available at: https://bookdown.org/MathiasHarrer/Doing_Meta_Analysis_in_R/. Accessed October 12, 2020.

- 33.Lam KW, Chow KW, Vo J. Continued in-hospital angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin ii receptor blocker use in hypertensive COVID-19 patients is associated with positive clinical outcome. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:1256–1264. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cannata F, Chiarito M, Reimers B. Continuation versus discontinuation of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers in COVID-19: effects on blood pressure control and mortality. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020;6:412–414. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaudhri I, Koraishy FM, Bolotova O. Outcomes associated with the use of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade in hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Kidney360. 2020;1:801–809. doi: 10.34067/KID.0003792020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu J, Zhang X, Zhang X. COVID-19 is more severe in patients with hypertension; ACEI/ARB treatment does not influence clinical severity and outcome. J Infect. 2020;81:979–997. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh AK, Gupta R, Misra A. Comorbidities in COVID-19: outcomes in hypertensive cohort and controversies with renin angiotensin system blockers. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fosbøl EL, Butt JH, Østergaard L. Association of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker use with COVID-19 diagnosis and mortality. JAMA. 2020;324:168–177. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Imam Z, Odish F, Gill I. Older age and comorbidity are independent mortality predictors in a large cohort of 1305 COVID-19 patients in Michigan, United States. J Intern Med. 2020;288:469–476. doi: 10.1111/joim.13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iaccarino G, Grassi G, Borghi C. Age and multimorbidity predict death among COVID-19 patients. Hypertension. 2020;76:366–372. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W. Factors associated with death in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1–12. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:211–218. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rabi DM, McBrien KA, Sapir-Pichhadze R. Hypertension Canada's 2020 comprehensive guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, risk assessment, and treatment of hypertension in adults and children. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:596–624. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.02.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johansen ME, Yun J, Griggs JM, Jackson EA, Richardson CR. Anti-hypertensive medication combinations in the United States. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:143. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2020.01.190134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy DP, Drawz PE, Foley RN. Trends in angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin ii receptor blocker use among those with impaired kidney function in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30:1314. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018100971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ibrahim SL, Jiroutek MR, Holland MA, Sutton BS. Utilization of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) in patients diagnosed with diabetes: analysis from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Prev Med Rep. 2016;3:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ezekowitz JA, O'Meara E, McDonald MA. 2017 comprehensive update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Heart Failure. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:1342–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chiu MH, Miller RJH, Barry R. Kidney function, ACE-inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker use, and survival following hospitalization for heart failure: a cohort study. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2018;5 doi: 10.1177/2054358118804838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghimire R, Dhungana SP. Evaluation of drugs used in chronic heart failure at tertiary care centre: a hospital based study. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2019;11:79–84. doi: 10.15171/jcvtr.2019.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tran RH, Aldemerdash A, Chang P. Guideline-directed medical therapy and survival following hospitalization in patients with heart failure. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38:406–416. doi: 10.1002/phar.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teng T-HK, Tromp J, Tay WT. Prescribing patterns of evidence-based heart failure pharmacotherapy and outcomes in the ASIAN-HF registry: a cohort study. Lancet Global Health. 2018;6:e1008–e1018. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.European Society of Cardiology. Hot line: Can ACEis and ARBs be safely continued in patients hospitalised with COVID-19? Results from the BRACE CORONA trial. Available at:https://www.escardio.org/Congresses-&-Events/ESC-Congress/Congress-resources/Congress-news/hot-line-can-aceis-and-arbs-be-safely-continued-in-patients-hospitalised-with-covid-19-results-from-the-brace-corona-trial. Accessed December 16, 2020.

- 55.Wu Z, Hu R, Zhang C. Elevation of plasma angiotensin II level is a potential pathogenesis for the critically ill COVID-19 patients. Crit Care. 2020;24:290. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03015-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang P, Gu H, Zhao Z. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) mediates influenza H7N9 virus-induced acute lung injury. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7027. doi: 10.1038/srep07027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bean DM, Kraljevic Z, Searle T. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers are not associated with severe COVID-19 infection in a multi-site UK acute hospital trust. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:967–974. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bravi F, Flacco ME, Carradori T. Predictors of severe or lethal COVID-19, including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers, in a sample of infected Italian citizens. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang Z, Cao J, Yao Y. The effect of RAS blockers on the clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients with hypertension. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:430. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.03.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li J, Wang X, Chen J, Zhang H, Deng A. Association of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors with severity or risk of death in patients with hypertension hospitalized for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:825–830. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meng J, Xiao G, Zhang J. Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors improve the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients with hypertension. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:757–760. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1746200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oussalah A, Gleye S, Clerc Urmes I. Long-term ACE inhibitor/ARB use is associated with severe renal dysfunction and acute kidney injury in patients with severe COVID-19: results from a referral center cohort in the Northeast of France. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2447–2456. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sardu C, Maggi P, Messina V. Could anti-hypertensive drug therapy affect the clinical prognosis of hypertensive patients with COVID-19 infection? Data from centers of Southern Italy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Şenkal N, Meral R, Medetalibeyoğlu A. Association between chronic ACE inhibitor exposure and decreased odds of severe disease in patients with COVID-19. Anatol J Cardiol. 2020;24:21–29. doi: 10.14744/AnatolJCardiol.2020.57431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan ND, Qiu Y, Xing XB. Associations between angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin ii receptor blocker use, gastrointestinal symptoms, and mortality among patients with COVID-19. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1170–1172. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.034. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang G, Tan Z, Zhou L. Effects of ARBs and ACEIs on virus infection, inflammatory status and clinical outcomes In COVID-19 patients with hypertension: a single center retrospective study. Hypertension. 2020;76:51–58. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang P, Zhu L, Cai J. Association of inpatient use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with mortality among patients with hypertension hospitalized with COVID-19. Circ Res. 2020;126:1671–1681. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, Antinori A. COVID-19 RISk and Treatments (CORIST) Collaboration. RAAS inhibitors are not associated with mortality in COVID-19 patients: findings from an observational multicenter study in Italy and a meta-analysis of 19 studies. Vasc Pharmacol. 2020;135 doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2020.106805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Covino M, De Matteis G, Burzo ML. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers and prognosis of hypertensive patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Intern Med J. 2020;50:1483–1491. doi: 10.1111/imj.15078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Felice C, Nardin C, Di Tanna GL. Use of RAAS inhibitors and risk of clinical deterioration in COVID-19: results from an Italian cohort of 133 hypertensives. Am J Hypertens. 2020;33:944–948. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpaa096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jung C, Bruno RR, Wernly B. Inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system and COVID-19 in critically ill elderly patients. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2021;7:76–77. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jung SY, Choi JC, You SH, Kim WY. Association of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related outcomes in Korea: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2121–2128. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.López-Otero D, López-Pais J, Cacho-Antonio CE. Impact of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers on COVID-19 in a western population. CARDIOVID registry. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2021;74:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Matsuzawa Y, Ogawa H, Kimura K. Renin–angiotensin system inhibitors and the severity of coronavirus disease 2019 in Kanagawa, Japan: a retrospective cohort study. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:1257–1266. doi: 10.1038/s41440-020-00535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Negreira-Caamaño M, Piqueras-Flores J, Martínez-DelRio J. Impact of treatment with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors on clinical outcomes in hypertensive patients hospitalized with COVID-19. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2020;27:561–568. doi: 10.1007/s40292-020-00409-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Selçuk M, Çınar T, Keskin M. Is the use of ACE inb/ARBs associated with higher in-hospital mortality in covid-19 pneumonia patients? Clin Exper Hypertens. 2020;42:738–742. doi: 10.1080/10641963.2020.1783549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shah P, Owens J, Franklin J. Baseline use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/AT1 blocker and outcomes in hospitalized coronavirus disease 2019 African-American patients. J Hypertens. 2020;38:2537–2541. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xu J, Huang C, Fan G. Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers in context of COVID-19 outbreak: a retrospective analysis. Front Med. 2020;14:601–612. doi: 10.1007/s11684-020-0800-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yuan Y, Liu D, Zeng S. In-hospital use of ACEI/ARB is associated with lower risk of mortality and critic illness in COVID-19 patients with hypertension. J Infect. 2020;81:816–846. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.