Abstract

Background

Deep remission in patients with UC has relied on initial achievement of biochemical, endoscopic, and/or histological remission. We evaluated persistent symptomatic remission and endoscopic healing (EH: Mayo endoscopy score [MES] 0 or 1) on consecutive endoscopic examinations as a durable treatment endpoint.

Methods

In a retrospective cohort study, we estimated and compared cumulative risk of clinical relapse in patients with persistent EH, with and without persistent histological remission and depth of EH, among adults with active UC treated-to-target of symptomatic remission and EH who achieved and maintained symptomatic remission and EH over two serial endoscopic assessments. We also explored risk of relapse in patients with persistent EH whose therapy was de-escalated.

Results

Of 270 patients who initially achieved EH with treatment-to-target, 89 maintained symptomatic remission and EH on follow-up endoscopy [interval between EH1 and EH2, 16 months]. On follow-up after EH2 [median, 19 months], 1-year cumulative risk of relapse in patients with persistent EH was 11.5%, and with persistent histological remission was 9.5%. Seventeen patients with persistent EH, who underwent de-escalation of therapy, did not have an increased risk of relapse as compared with patients who continued index therapy [5.3% vs 14%, p = 0.16].

Conclusions

Patients with active UC treated-to-target of clinical remission, who achieve and maintain symptomatic remission and EH over consecutive endoscopies, have a low risk of relapse, particularly in a subset of patients who simultaneously achieve histological remission. Persistent EH should be examined as a treatment endpoint suggestive of deep remission.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel diseases, biologics, deep remission, flare

1. Introduction

An optimal treatment strategy in ulcerative colitis [UC] involves identifying patients at high risk of complications, selecting appropriate therapy, and treating systematically towards a relevant clinical target. Whereas considerable emphasis has been placed on risk stratification, positioning of therapies, and choosing treatment endpoints of symptomatic, biochemical, endoscopic, and/or histological remission, approaches to de-escalation of therapy have not been well studied in patients with UC. An ideal strategy would involve identifying patients at the lowest acceptable risk of relapse, followed by close monitoring for early detection of relapse. Premature de-escalation increases risk of relapse; delayed de-escalation may unnecessarily subject patients to treatment-related toxicity. Current studies suggest that annual risk of relapse after de-escalation of anti-tumour necrosis factor-α(anti-TNFα] therapy in patients with UC is ~35%, based on a meta-analysis of four studies with 122 patients. 1

Ongoing endoscopic activity has been among the most studied factors that contribute to relapse, but the achievement of endoscopic remission beyond symptomatic remission still carries an annual risk of relapse that exceeds 25%. 2–5 Recent studies have focused on achieving histological remission as a more stringent endpoint, achievement of which may be associated with lower risk of relapse. 6–9 However, in a retrospective cohort study of patients with active UC treated systematically to a target of symptomatic and endoscopic remission, we observed that annual risk of relapse in patients who additionally achieved histological remission was 18.9%. 3 Most previous studies have focused on deep remission as a durable treatment endpoint, assessed cross-sectionally, as simultaneously achieving corticosteroid-free symptomatic remission with varying degree of biochemical, endoscopic and/or histological remission. There has been limited assessment of longitudinal achievement and maintenance of symptomatic and endoscopic remission, with or without histological remission, as a treatment endpoint that may help identify patients with UC at lowest risk of relapse.

Hence, we conducted a retrospective cohort study in patients with active UC who were treated-to-target of conventional clinical remission (comprising both symptomatic remission and endoscopic healing [EH] defined as modified Mayo endoscopy score [MES] 0 or 1) in routine clinical practice, and maintained symptomatic remission and EH [persistent EH] on a follow-up endoscopy. We sought to evaluate cumulative risk of relapse in this cohort, overall and by varying depth of EH [MES 0 vs MES 1], and histological remission. We explored outcomes in patients with persistent EH who underwent de-escalation of therapy.

2. Methods

2.1. Study setting

We performed a retrospective cohort study in UC patients followed at the University of California San Diego [UCSD], a tertiary care inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] referral centre. This study was approved by the UCSD Institutional Review Board [IRB# 191,127].

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible patients had: [a] a diagnosis of UC based on standard clinical, endoscopic, and histological criteria; [b] were seen and followed at UCSD for at least 6 months between 2012 and 2019; [c] had clinically and endoscopically active UC at cohort entry; [d] achieved treatment target of both symptomatic remission and EH [EH1] through iterative treat-to-target interventions; and [e] demonstrated persistent symptomatic remission and EH [EH2] on a successive endoscopy.

Patients were excluded if they had Crohn’s disease or IBD unclassified, if they did not have active disease at initial assessment, or did not achieve symptomatic remission and EH at two follow-up endoscopic evaluations. Patients who experienced symptomatic and/or endoscopic flare between EH1 and EH2 were excluded.

2.3. Routine clinical practice

All patients with IBD at UCSD are treated by an IBD team following unified evidence-based guidelines. Patients with UC are treated-to-target of EH consisting of serial endoscopic evaluation every 4–6 months, followed by stepwise treatment intensification in the presence of moderate to severe endoscopic activity [MES 2 or 3], and interval re-evaluation. All endoscopies are performed by gastroenterologists trained specifically in IBD through an advanced fellowship, and two out of four endoscopists serve as central readers for clinical trials. All endoscopists follow a standard biopsy protocol. For disease activity assessment, a minimum of two biopsies are obtained from the worst area of the right and left colon [colonoscopy] or from the rectosigmoid colon [flexible sigmoidoscopy]. If performed for dysplasia surveillance, then biopsies are obtained from the caecum/ascending, transverse, descending, and rectosigmoid colon. One of five pathologists blinded to all clinical information reviewed slides, and a single gastroenterologist [SJ] blinded to other clinical data at the time of review, assigned a histological classification [described below].

2.4. Data abstraction

A single reviewer [SJ] abstracted data using a standardised form. In addition to exposure and outcome variables [see below], the following items were abstracted: age at cohort entry and diagnosis, sex, body mass index, smoking status, disease duration, disease location, clinical and endoscopic disease activity, treatment at initial and follow-up evaluations, date of endoscopy, degree of EH, degree of histological activity at time of active UC and during periods of clinical remission, and de-escalation of biologics, Janus kinase [JAK] inhibitors, immunomodulators, or aminosalicylic acid [ASA] therapy.

2.5. Definitions

Clinically active disease was defined as rectal bleeding (rectal bleeding score [[RBS] >0) and 3–4 stools above normal (stool frequency score [SFS], 2 to 3). Endoscopically active disease was defined as MES 2 or 3. Symptomatic remission was defined as resolution of rectal bleeding [RBS 0] and near-normalisation of stool frequency [SFS 0 or 1], with absence of corticosteroids. EH was defined as MES 0 or 1, complete endoscopic remission as MES 0, and mild endoscopic activity as MES 1. Persistent EH was defined as persistent symptomatic remission and EH on two successive endoscopic evaluations. Patients with persistent EH may have mild endoscopic activity [MES 1] or complete endoscopic remission [MES 0] on one or both endoscopic evaluations, and may or may not have achieved histological remission on one or both examinations. Histological remission was defined as either complete mucosal normalisation or chronic architectural changes in the absence of neutrophilic infiltrate. Histological activity was defined as architectural changes with superimposed acute infiltrate characterised as mild [neutrophilic cryptitis], moderate [neutrophilic cryptitis and neutrophilic crypt abscesses], or severe [presence of ulcer], similar to the established Nancy histological index. 10,11 Persistent histological remission was defined as patients achieving and maintaining histological remission, as previously described, on two consecutive endoscopic assessments, during persistent EH. One patient had no histological assessment on subsequent endoscopic evaluation, and was excluded from histological analyses.

2.6. Exposures and comparisons

Our primary analysis focused on evaluating the cumulative risk of relapse in patients with UC who achieve persistent EH [regardless of histological activity], and in patients who achieve persistent EH and histological remission.

Secondary analyses included the following.

1. Compare risk of clinical relapse based on depth of persistent EH, regardless of histological activity (EH1 and EH2: persistent complete endoscopic remission [MES 0/0] vs mild endoscopic activity at either one or both follow-up evaluations [MES 1/1 or MES 0/1 or MES 1/0]). Exploratory analyses based on depth of EH at time of EH2 [MES 0 vs MES 1] regardless of depth of EH at time of EH1, and comparing patients with persistent complete endoscopic remission [MES 0/MES 0] vs patients with persistent mild endoscopic activity [MES 1/MES 1] were also performed.

2. Compare risk of clinical relapse based on histological activity status at time of persistent EH [persistent histological remission on both EH1 and EH2 vs histological activity at time of either EH1 or EH2 or both EH1 and EH2]. Exploratory analyses based on presence vs absence of histological remission at time of EH2, regardless of histological activity status at time of EH1, and comparing patients with persistent histological remission vs patients with persistent histological activity on both assessments, were also performed.

We also evaluated risk of relapse in patients with persistent EH where a clinical decision was made to de-escalate therapy vs patients who were continued on index therapy. De-escalation was defined as reduction in dose [or widening of interval] of biologic therapy, reduction in dose of JAK inhibitor therapy, reduction or cessation of immunomodulator therapy [azathioprine, mercaptopurine, or methotrexate] either in patients on combination therapy or immunomodulator monotherapy, or reduction or cessation of ASA therapy. An event was considered as de-escalation only if the decision to de-escalate was made by the patients and treating providers that it was safe to de-escalate, rather than withdrawal of therapy due to non-compliance or adverse events. In this retrospective study, de-escalation was at discretion of individual providers and not protocolised.

2.7. Outcomes

The primary outcome was time to clinical relapse, defined as recurrence of any rectal bleeding [RBS >0] with an increase in stool frequency [SFS 2 or 3], after achieving persistent EH. Secondary outcomes were time to UC-related emergency room visit or hospitalisation and time to UC-related surgery.

2.8. Statistical analyses

Patients who achieved persistent EH were classified based on depth of EH, and presence or absence of histological remission at time of EH1 and EH2. Patients were followed from the time they achieved persistent EH [time of EH2] until clinical relapse [or UC-related emergency room visit or hospitalisation or surgery], date of last follow-up in the clinic, or end of study [30 April 2020]. For the primary analysis, we used Kaplan‐Meier survival curves to estimate the cumulative risk of clinical relapse in patients who achieved persistent EH, and in patients who achieved persistent EH and persistent histological remission. For secondary analyses, we used log-rank tests to compare time to clinical relapse based on: [1] depth of EH [MES 0/0 vs MES 0/1 or 1/0 or 1/1; MES 0 vs MES 1 at time of EH2, regardless of depth of EH at time of EH1]; and [2] histological remission status [persistent histological remission on both EH1 and EH2 vs histological activity at time of either EH1 or EH2 or both EH1 and EH2; presence or absence of histological remission at time of EH2, regardless of histological activity at time of EH1].

In exploratory analysis where a clinical decision had been made to de-escalate therapy, we examined differences in clinical, endoscopic, and histological activity in patients who were vs were not de-escalated. We compared time to clinical relapse in patients whose therapy was de-escalated vs not de-escalated, in response to persistent EH.

All hypothesis testing was performed using a two-sided p-value with statistical significance threshold <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using RStudio [Version 1.1.456, Boston, MA].

3. Results

3.1. Study cohort

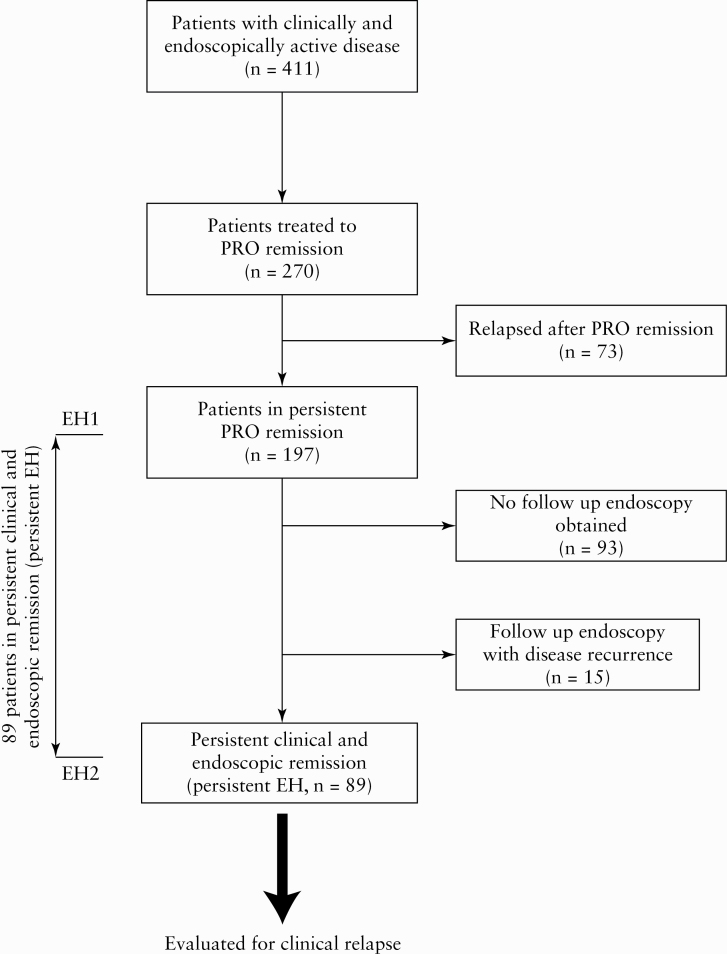

We identified 411 patients with clinically and endoscopically active UC who underwent iterative treat-to-target interventions, of whom 270 [65.7%] successfully achieved clinical remission over a median of 11 months (interquartile range [IQR], 6–11 months). Of the 270 who achieved clinical remission, 197 [73.0%] patients remained in persistent symptomatic remission over a median follow-up time of 22 months [attained EH1, IQR, 10–43]. Of these 197 patients in persistent symptomatic remission, 93 patients [47%] did not undergo follow-up endoscopies, therefore it was not possible to determine if these patients were in persistent EH. Of the remaining 104 patients in persistent symptomatic remission who had follow-up endoscopies, 53 [51%] underwent the second scope to confirm endoscopic healing and 51 [49%] underwent the second scope for dysplasia surveillance. Fifteen patients were found to have endoscopically active disease on the second endoscopy. The remaining 89 patients demonstrated persistent symptomatic remission and EH over a median duration of 16 months between EH1 and EH2 [IQR, 12–24], and formed the study cohort [persistent EH, n = 89] [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Study schema.

To account for potential selection bias, we compared baseline characteristics of patients in persistent symptomatic remission with no follow-up endoscopies [n = 93] vs patients in persistent symptomatic remission who had follow-up endoscopies demonstrating persistent EH [EH2, n = 89]. No significant differences were observed in key clinical characteristics, including age at time of active UC, age at UC diagnosis, disease extent, and use of immunosuppressive therapy, except a longer disease duration in patients with follow-up endoscopy [12 years vs 8 years; p <0.05] [Supplementary Table 1, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online].

At the time of EH2, 34 patients [27%] were using ASA, 31 patients [35%] were taking anti-TNF therapy, 33 patients [37%] were on vedolizumab, and four patients [4.5%] were on tofacitinib; 16 patients [18%] were on combination therapy with either an anti-TNF or vedolizumab and an immunomodulator.

3.2. Persistent endoscopic healing and risk of relapse

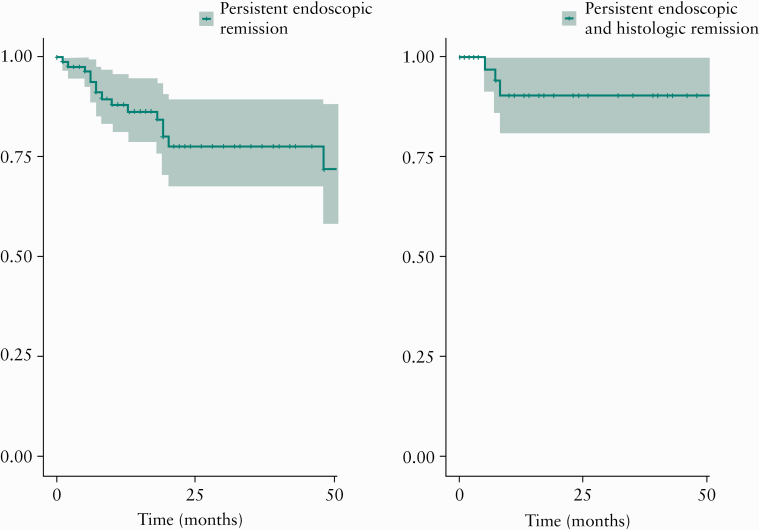

Over a median follow-up time of 19 months [IQR 9–40 months] after achieving persistent EH [after EH2], 17 patients [19.1%] relapsed, with a 1- and 2-year cumulative risk of relapse of 11.8% and 22.3%, respectively [Figure 2A]. As compared with patients with persistent EH who remained in remission, patients who relapsed were more likely to have persistent histological activity on both endoscopies [EH1 and EH2], or at time of last endoscopy [EH2] [Table 1]. Patients who relapsed were also more likely to have a longer duration of disease [17 months vs 11.5 months, p <0.05] and were less likely to be on concurrent immunomodulators or biologics [52.9% vs 84.7%, p <0.05]. Risks of surgery and hospitalisation were low in patients with persistent EH. At the end of follow-up, only four patients [4.5%] required surgery and four patients [4.5%] required an emergency room visit or hospitalisation.

Figure 2.

Cumulative risk of clinical relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis [UC], treated to target of clinical remission, who achieve: [A] persistent symptomatic and endoscopic remission over two consecutive endoscopies; and [B] persistent symptomatic and endoscopic remission with concurrent histological remission over two consecutive endoscopies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with ulcerative colitis in persistent symptomatic and endoscopic remission over two consecutive endoscopies, with ongoing remission or subsequent clinical relapse.

| No relapse | Relapse | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 72 | 17 | ||

| Age, mean, [SD] | 47.8 [16.1] | 53.5 [20.1] | 0.25 | |

| Female gender, frequency | 52.8% | 58.8% | 0.39 | |

| Age at diagnosis, mean [SD] | 34.2 [15.6] | 34.2 [17.2] | 0.84 | |

| Disease duration, median [IQR] | 11.5 [9.75] | 17 [13] | <0.05 | |

| Extensive colitis [% of total] | 52.8% | 47.1% | 0.67 | |

| Current biologic and/or immunomodulator use frequency | 84.7% | 52.9% | <0.05 | |

| Previous biologic or immunomodulator use | 76.3% | 70.6% | 0.62 | |

| Duration of remission between endoscopic assessments, median [IQR] | 15.5 [12] | 16 [11] | 0.65 | |

| MES 1, frequency | On first assessment | 54.2% | 760.5% | 0.09 |

| On second assessment | 40.3% | 520.9% | 0.34 | |

| On both assessments | 30.6% | 470.1% | 0.20 | |

| Histological activity, frequency | On first assessment | 38.9% | 520.9% | 0.29 |

| On second assessment | 27.8% | 620.5% | <0.05 | |

| On both assessments | 15.3% | 430.8% | <0.05 |

IQR, interquartile range; MES, Mayo endoscopy score; SD, standard deviation.

Bolded p-values show statistical significance <0.05.

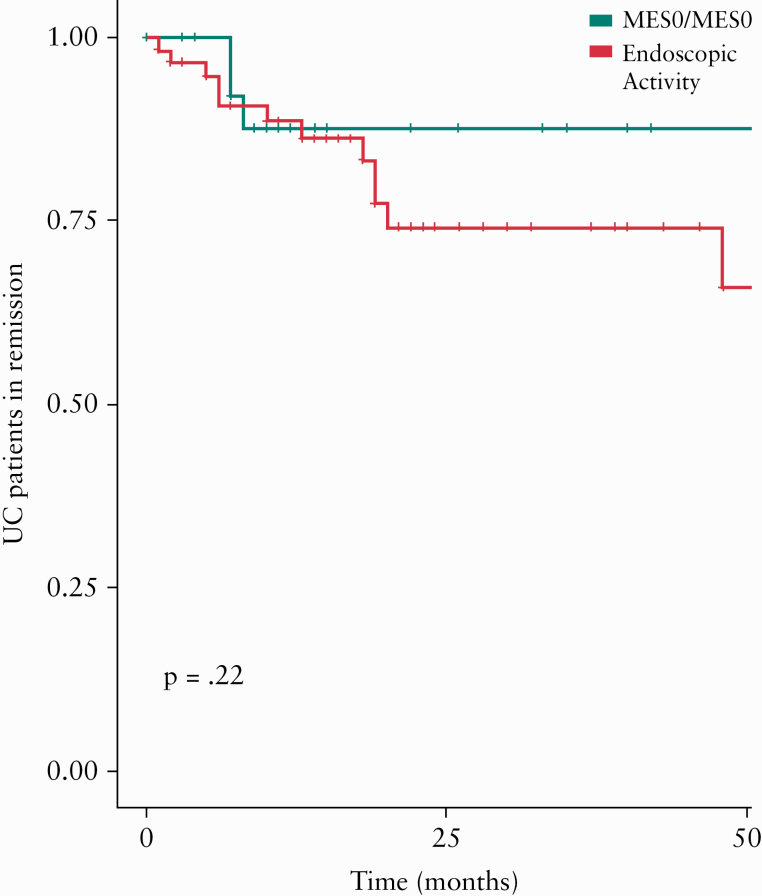

3.3. Depth of endoscopic healing and risk of subsequent clinical relapse

Of 89 patients with persistent EH, 29 patients [32.6%] had persistent complete endoscopic remission [MES 0/MES 0] and 30 patients [33.7%] had persistent mild endoscopic activity [MES 1/MES 1] [Supplementary Figure 1A, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online]. Though numerically risk of relapse in patients who achieved persistent complete endoscopic remission [MES 0/0, n = 29] vs patients who had mild endoscopic activity [n = 60] at either or both follow-up endoscopic examinations was lower, this difference was not statistically significant [2-year risk of relapse = 12.4% vs 25.9%, p = 0.22] [Figure 3]. Similarly, though numerically the risk of relapse was lower in patients with complete endoscopic remission [MES 0/0 or MES 1/0] vs patients with mild endoscopic activity [MES 1/1 or MES 0/1] at last assessment, this difference was not statistically significant [2-year risk of relapse = 14.6% vs 31.0%, p = 0.47] [Supplementary Figure 2, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online].

Figure 3.

Cumulative risk of clinical relapse in patients with UC, treated to target of clinical remission, who achieve persistent symptomatic and endoscopic remission with either [green] complete endoscopic remission over two consecutive endoscopies [MES 0/MES 0] or [red] mild ongoing endoscopic activity on either or both endoscopic assessments [MES 1/0, MES 0/1, or MES 1/1]. UC, ulcerative colitis; MES, Mayo Endoscopy score.

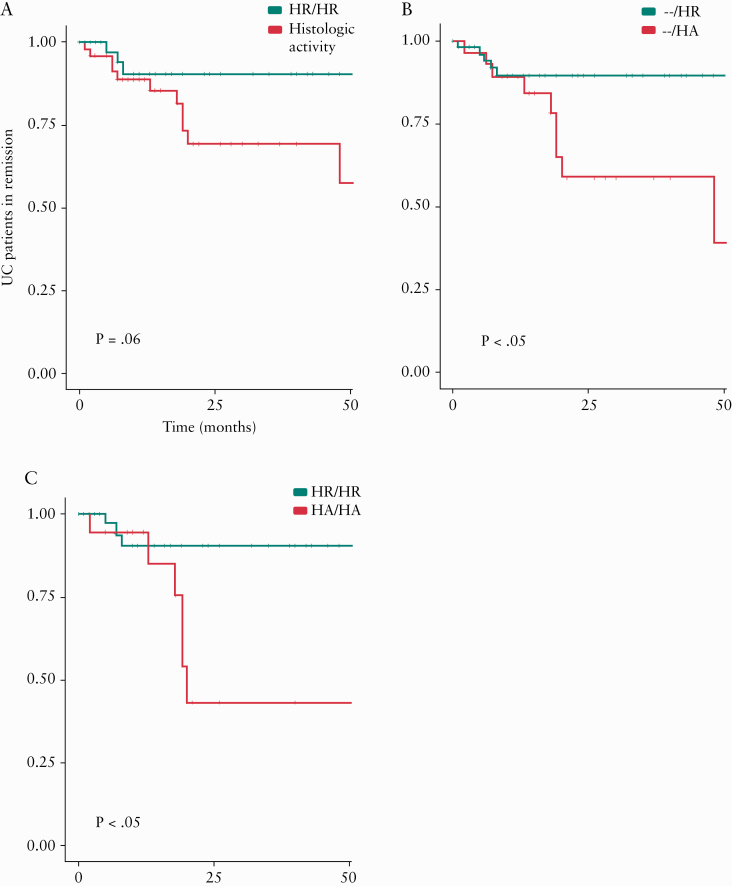

3.4. Persistent histological remission and risk of relapse

Of 89 patients with persistent EH, 39 patients [44.3%] had persistent histological remission on both endoscopic evaluations [EH1 and EH2] and 19 patients [21.5%] had persistent histological activity on both assessments [Supplementary Figure 1B]. In the 39 patients with persistent EH and histological remission, 1- and 2-year cumulative risks of relapse were 9.5% and 9.5%; persistent histological remission was associated with very low risk of relapse beyond 1 year of follow-up [Figure 2B].

On time-to-event analysis, the risk of clinical relapse was numerically but not statistically lower in patients with persistent histological remission [on both assessments] vs patients with histological activity at either or both follow-up endoscopic examinations [Figure 4A] [2-year risk of relapse: 11.3% vs 30.7%, p = 0.06]. However, risk of clinical relapse was significantly lower in patients with histological remission vs histological activity at last assessment [2-year risk of relapse: 10.4% vs 41.3% p <0.01] [Figure 4B]. Risk of clinical relapse was also significantly lower in patients with persistent histological remission vs persistent histological activity on both assessments [2-year risk of relapse: 9.5% vs 56.8%] [Figure 4C].

Figure 4.

Cumulative risk of clinical relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis [UC], treated to target of clinical remission, who achieve: [A] persistent symptomatic and endoscopic remission with either [green] concurrent histological remission on both endoscopic assessments [HR/HR] or [red] ongoing histological activity on either or both endoscopic assessments [HA/HR, HR/HA, or HA/HA]; [B] persistent symptomatic and endoscopic remission with either [green] concurrent histological remission on last endoscopic assessments [-/HR] or [red] ongoing histological activity on last endoscopic assessments [-/HA]; [C] persistent symptomatic and endoscopic remission with either [green] concurrent histological remission on both endoscopic assessments [HR/HR] or [red] ongoing histological activity on both endoscopic assessments [HA/HA]. HA, histologic activity; HR, histologic remission.

3.5. Sensitivity analysis of patients with persistent endoscopic healing who had de-escalation of pharmacotherapy

Following persistent EH, 19 patients [21.3%] underwent de-escalation—seven patients reduced their biologic dose [of 29 patients on dose-escalated biologics], seven patients reduced or stopped an immunosuppressive [out of 16 patients on combination therapy], and five patients reduced or stopped ASA. Among those patients on biologic monotherapy or combination therapy with an immunomodulator who underwent de-escalation of either biologic dose or immunomodulator dose [n = 14], seven patients had trough concentrations of the biologic drug checked before de-escalation and only three patients had trough concentrations obtained after de-escalation. All seven of these patients had infliximab, adalimumab, or vedolizumab levels above recommended therapeutic thresholds before de-escalation.

Depth of EH or persistence of histological remission did not differ among patients who were de-escalated vs patients who were not de-escalated [Supplementary Table 2, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online]. On follow-up, patients who de-escalated therapy were not more likely to relapse than those who were not de-escalated [2-year risk of relapse, 13.9% vs 25%, p = 0.16].

4. Discussion

Previous studies have focused on cross-sectional achievement of biochemical, endoscopic. and/or histological remission, besides corticosteroid-free symptomatic remission, as ‘deep remission’. 12–14 In this study, we examined clinical outcomes in patients achieving and maintaining treatment endpoints of EH with or without histological remission, on stable therapy. In a well-characterised cohort of 270 patients with active UC who achieved symptomatic remission and EH through iterative treat-to-target interventions, we identified 89 patients who maintained EH [median interval between endoscopic evaluations, 16 months]. Over a median follow-up of 19 months after persistent EH, we observed that the cumulative risk of relapse at 1 year was 11.8%, significantly lower than the 1-year risk of relapse of 23.7% observed in patients who achieved EH at one time point, with treat-to-target interventions in our cohort. 3 In a smaller set of patients who achieved and maintained histological remission with persistent EH [44% of cohort], the cumulative risk of relapse at 1 year was 9.5%, significantly lower than the 1-year risk of relapse of 18.7% observed in patients who achieved histological remission with EH at one time point, with treat-to-target interventions. Risk of relapse was not incremental beyond 1 year of follow-up after persistent EH, particularly in patients with persistent complete endoscopic remission and/or persistent histological remission. Our observation of a low risk of relapse in patients achieving and maintaining EH with or without histological remission is within the acceptable risk of relapse, such that patients may be willing to consider de-escalation of medications. 15

Though numerical trends were noted, we did not observe significant differences in the risk of relapse in patients with varying depth of EH (persistent complete endoscopic remission [MES 0] or persistent or transient mild endoscopic activity [MES 1]). Our study may have been underpowered to detect these differences, and future prospective studies are warranted to identify whether depth of persistent EH modifies risk of relapse in patients with UC. We observed that the risk of relapse was significantly lower in patients with persistent EH who incrementally achieved histological remission, as compared with patients who had persistent or transient histological activity. In our study, patients were in symptomatic remission and EH for median 16 months, and in this subset with durable remission, persistent histological remission was incrementally associated with minimal risk of relapse. We have previously shown that patients treated to endoscopic remission have superior outcomes when concurrent histological remission is achieved, with subsequent reduced clinical relapse rates and hospitalisations especially in patients with MES 1 disease. 16,17 Consequently, our results here underline our earlier observations that histological remission may prove a more durable target than endoscopic remission alone.

On exploratory analysis of a smaller set of patients with persistent EH, who were de-escalated at the discretion of treating providers, we did not observe significant differences in risk of relapse as compared with patients who continued on their index therapy after persistent EH; at 1 year, risk of relapse was 5.6% in a carefully selected subset of patients who underwent de-escalation. Previous studies have suggested that the risk of relapse with de-escalation in patients with IBD achieving ‘deep remission’, defined as a combination of clinical and endoscopic remission, is 28.7% at 1 year and 38.4% at 2 years. 18 In a recent prospective trial of anti-TNF withdrawal in patients with UC, investigators observed that anti-TNF withdrawal, after one-time achievement of endoscopic healing after >6 months of corticosteroid-free symptomatic remission, was associated with an unacceptably high 46% risk of relapse at 48 weeks. 19 Besides achievement of symptomatic, endoscopic, and histological remission endpoints, several other factors have been associated with risk of relapse in patients with UC undergoing de-escalation of therapy. These include young age, extensive disease, ‘difficulty’ in achieving remission with pharmacotherapy, with multiple earlier relapses on index therapy or failure of alternative immunosuppressive therapies and short duration of remission. Therefore, the achievement of persistent endoscopic remission, even with concurrent histological remission, may not be sufficient for maintenance of remission following de-escalation. Although persistent endoscopic remission is an appealing target to achieve given the subsequently low relapse rates demonstrated in this study, considerations for de-escalation must still be tailored to the additional risks carried within the individual patient. This includes careful consideration of de-escalating patients on combination therapy with anti-TNF agents and immunomodulators, who may be genetically at high risk of immunogenicity. 20

Whereas there are several strengths to our study, including examining a novel treatment endpoint of achieving and maintaining persistent EH in patients with active UC treated to conventional targets, and systematic endoscopy and biopsy protocols in our cohort, there are several limitations. First, as a retrospective observational study, there was no defined protocol for follow-up endoscopies in patients who initially achieved EH with treat-to-target interventions. However, we did not observe any selection bias when comparing patients with persistent symptomatic remission who did vs did not undergo follow-up endoscopy. Due to lack of standard protocol, our proposed treatment endpoint of persistent EH includes both a component of persistency of EH as well as duration of remission [median interval between endoscopic assessments showing EH, 16 months]. Second, since the number of patients with persistent symptomatic and endoscopic remission was relatively small [n = 89] with low rates of outcomes, our study may be underpowered to detect significant differences in risk of relapse in patients with varying depth of endoscopic healing. Third, de-escalation of therapy was not standardised or universally implemented, and was at discretion of treating provider. The number of patients who underwent de-escalation was small. Furthermore, it is not clear what factor[s] drove the shared provider and patient decision to de-escalate, and we cannot be certain how much the findings of persistent EH played into the decision. Fourth, we did not use a validated histological scoring system. However, histological assessment was blinded and pathologists modelled their interpretations on the established Nancy index, as a recommended index for use in clinical practice. 11

In conclusion, in the subset of patients with active UC who are treated to conventional clinical remission target, we observed that patients who achieve and maintain persistent EH may have a low risk of clinical relapse [1-year risk of relapse <12%], particularly a subset of patients with concurrent histological remission. In a selected subset of these patients with persistent EH, a clinical decision to de-escalate therapy was not associated with an increased risk of relapse. However, de-escalation is a complex decision affected by many variables. Larger prospective studies are needed examine whether persistent endoscopic healing may serve as a durable treatment endpoint for considering therapeutic de-escalation using protocol-driven treatment changes.

Supplementary Material

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Funding

PSD is supported by an American Gastroenterology Association Research Scholar Award. BSB is supported by the National Institute of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases K23DK117058. WS is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease-funded San Diego Digestive Diseases Research Center [P30 DK120515]. SS is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases K23DK117058. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

AC reports consulting fees from Abbvie, Janssen, and Takeda, and speaking fees from Abbvie, Janssen, and Takeda. PD has received research support from Takeda, Pfizer, Abbvie, Janssen, Polymedco, ALPCO, Buhlmann, and consulting fees from Takeda, Pfizer, Abbvie, and Janssen. BB has received research support from Prometheus Biosciences, and consulting fees from Pfizer. WS has received: research grants from Atlantic Healthcare, Amgen, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Abbvie, Janssen, Takeda, Lilly, Celgene/Receptos,Pfizer, Prometheus Laboratories [now Prometheus Biosciences]; consulting fees from Abbvie, Allergan, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Avexegen Therapeutics, BeiGene, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Celltrion, Conatus, Cosmo, Escalier Biosciences, Ferring, Forbion, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Gossamer Bio, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Research, Landos Biopharma, Lilly, Oppilan Pharma, Otsuka, Pfizer, Progenity, Prometheus Biosciences [merger of Precision IBD and Prometheus Laboratories], Reistone, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Robarts Clinical Trials [owned by Health Academic Research Trust, HART], Series Therapeutics, Shire, Sienna Biopharmaceuticals, Sigmoid Biotechnologies, Sterna Biologicals, Sublimity Therapeutics, Takeda, Theravance Biopharma, Tigenix, Tillotts Pharma, UCB Pharma, Ventyx Biosciences, Vimalan Biosciences, Vivelix Pharmaceuticals; and stock or stock options from BeiGene, Escalier Biosciences, Gossamer Bio, Oppilan Pharma, Prometheus Biosciences [merger of Precision IBD and Prometheus Laboratories], Progenity, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Ventyx Biosciences, Vimalan Biosciences. SS has received research grants from AbbVie and Janssen, and personal fees from Pfizer. SJ, AKH, LP has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to: the concept and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be submitted. Concept: SJ, WJS, SS; data abstraction: SJ; data analysis and interpretation: SJ, PDS, BGS, WJS, SS; drafting of manuscript: SJ, WJS, SS; critical review of manuscript: SJ, AH, PDS, BGS, AC, LP, WJS, SS; statistical analysis: SJ, SS; guarantor of article: SS.

References

- 1. Kennedy NA, Warner B, Johnston EL, et al. ; UK Anti-TNF withdrawal study group . Relapse after withdrawal from anti-TNF therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: an observational study, plus systematic review and meta-analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;43:910–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gisbert JP, Marín AC, Chaparro M. Systematic review: factors associated with relapse of inflammatory bowel disease after discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:391–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jangi S, Yoon H, Dulai P, et al. Effect of histologic activity on clinical outcomes in patients with ulcerative colitis treated-to-target: comparison of clinical vs endoscopic vs histological remission. Gastroenterology 2020;158:S‐698. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barreiro-de Acosta M, Vallejo N, de la Iglesia D, et al. Evaluation of the risk of relapse in ulcerative colitis according to the degree of mucosal healing [Mayo 0 vs 1]: A longitudinal cohort study. J Crohns Colitis 2016;10:13–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boal Carvalho P, Dias de Castro F, Rosa B, Moreira MJ, Cotter J. Mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis—when zero is better. J Crohns Colitis 2016;10:20–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Christensen B, Hanauer SB, Erlich J, et al. Histological normalization occurs in ulcerative colitis and is associated with improved clinical outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:1557–64.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cushing KC, Tan W, Alpers DH, Deshpande V, Ananthakrishnan AN. Complete histological normalisation is associated with reduced risk of relapse among patients with ulcerative colitis in complete endoscopic remission. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020;51:347–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Calafat M, Lobatón T, Hernández-Gallego A, et al. Acute histological inflammatory activity is associated with clinical relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical and endoscopic remission. Dig Liver Dis 2017;49:1327–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gubatan J, Mitsuhashi S, Zenlea T, et al. Low serum vitamin D during remission increases risk of clinical relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:240–6 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marchal-Bressenot A, Salleron J, Boulagnon-Rombi C, et al. Development and validation of the Nancy histological index for UC. Gut 2017; 66:43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Magro F, Doherty G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. ECCO position paper: Harmonisation of the approach to ulcerative colitis histopathology. J Crohns Colitis 2020,. Jun 6. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa110. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fiorino G, Cortes PN, Ellul P, et al. Discontinuation of infliximab in patients with ulcerative colitis is associated with increased risk of relapse: a multinational retrospective cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1426–32.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Casanova MJ, Chaparro M, García-Sánchez V, et al. Evolution after anti-TNF discontinuation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a multicenter long-term follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:120–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Molander P, Färkkilä M, Ristimäki A, et al. Does fecal calprotectin predict short-term relapse after stopping TNFα-blocking agents in inflammatory bowel disease patients in deep remission? J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Siegel CA, Thompson KD, Walls D, et al. Crohn’s disease patients’ and gastroenterologists’ perspectives towards de-escalating inflammatory bowel disease therapy: a comparative European and American survey. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, Dec 27. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.11.062. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jangi S, Yoon H, Dulai PS, et al. Predictors and outcomes of histological remission in ulcerative colitis treated to endoscopic healing. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020, August 9. 10.1111/apt.16026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yoon H, Jangi S, Dulai PS, et al. Incremental benefit of achieving endoscopic and histological remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2020, Jun 22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.043. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang B, Gulati A, Alipour O, et al. Relapse from deep remission after therapeutic de-escalation in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis 2020, Apr 26. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa087. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kobayashi T, Motoya S, Nakamura S, et al. The first prospective, multicentre, randomised controlled trial on discontinuation of infliximab in ulcerative colitis in remission; endoscopic normalisation does not guarantee successful withdrawal. J Crohns Colitis 2020;14:S076–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sazonovs A, Kennedy NA, Moutsianas L, et al. ; PANTS Consortium . HLA-DQA1*05 carriage associated with development of anti-drug antibodies to infliximab and adalimumab in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2020;158:189–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.