Abstract

Background

Cutaneous reactions after messenger RNA (mRNA)-based COVID-19 vaccines have been reported but are not well characterized.

Objective

To evaluate the morphology and timing of cutaneous reactions after mRNA COVID-19 vaccines.

Methods

A provider-facing registry-based study collected cases of cutaneous manifestations after COVID-19 vaccination.

Results

From December 2020 to February 2021, we recorded 414 cutaneous reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines from Moderna (83%) and Pfizer (17%). Delayed large local reactions were most common, followed by local injection site reactions, urticarial eruptions, and morbilliform eruptions. Forty-three percent of patients with first-dose reactions experienced second-dose recurrence. Additional less common reactions included pernio/chilblains, cosmetic filler reactions, zoster, herpes simplex flares, and pityriasis rosea-like reactions.

Limitations

Registry analysis does not measure incidence. Morphologic misclassification is possible.

Conclusions

We report a spectrum of cutaneous reactions after mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. We observed some dermatologic reactions to Moderna and Pfizer vaccines that mimicked SARS-CoV-2 infection itself, such as pernio/chilblains. Most patients with first-dose reactions did not have a second-dose reaction and serious adverse events did not develop in any of the patients in the registry after the first or second dose. Our data support that cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccination are generally minor and self-limited, and should not discourage vaccination.

Key words: COVID-19, dermatology, Moderna, mRNA, Pfizer, public health, registry, SARS-CoV-2, vaccine, vaccine reaction, delayed hypersensitivity, delayed inflammatory reaction, zoster, shingles, delayed large local reaction, pityriasis rosea, local injection site reaction, erythromelalgia, urticaria, morbilliform, pernio, chilblains, vesicular, erythema multiforme, filler, vasculitis

Capsule Summary.

-

•

Across 414 cutaneous reactions to the messenger RNA COVID-19 vaccines in our registry, the most common morphologies were delayed large local reactions, local injection site reactions, urticaria, and morbilliform eruptions.

-

•

Less than 50% of patients with cutaneous reactions after the first dose experienced second-dose recurrence. None reported serious adverse events.

Introduction

In December 2020, the Food and Drug Administration issued Emergency Use Authorizations for Pfizer/BioNTech (BNT162b2) and Moderna (mRNA-1273) COVID-19 vaccines.

Clinical trials for both vaccines reported local injection site reactions and systemic symptoms after both doses.1 , 2 Moderna additionally noted delayed injection site reactions (on/after day 8) in 244 participants (0.8%) after the first dose and in 68 participants (0.2%) after the second dose.1 Moderna's trial also described vesicular, urticarial, exfoliative, macular, and papular rashes, as well as facial swelling after cosmetic filler injections.1 However, trials did not fully characterize cutaneous reactions and did not describe whether subjects with reactions after the first dose also had reactions with the second.

Given the importance of widespread vaccination in curbing the pandemic, we aimed to collect cases of cutaneous side effects to the messenger RNA (mRNA) COVID-19 vaccines (1) to describe the morphology and timing of cutaneous reactions to the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines and (2) to understand differences in cutaneous reactions between the 2 vaccine doses to guide vaccine counseling.

Methods

Our international registry of cutaneous manifestations of SARS-CoV-2, established in March 2020 as a collaboration between the American Academy of Dermatology and the International League of Dermatological Societies, expanded on December 24, 2020, to collect COVID-19 vaccine cutaneous reactions, shortly after the Food and Drug Administration issued Emergency Use Authorizations (www.aad.org/covidregistry).3 Case entry in the registry was open to health care workers only. Collected data were deidentified.

The vaccine module of the registry collected dates for both vaccine doses, morphology of cutaneous reaction(s), timing and duration of reaction(s), and treatments. Local site reactions were defined as occurring within 3 days of first-dose vaccination and delayed large local reactions were defined as occurring 4 or more days after the first vaccination. A wheal at the vaccine site was considered an immediate or delayed large local reaction, depending on timing.4 Conversely, urticarial reactions were defined as wheals in a distribution beyond the injection site.

We only included cutaneous reactions reported after vaccination with Food and Drug Administration-approved Pfizer or Moderna mRNA vaccines, which at the time of analysis were being administered mostly to health care workers and elderly patients. Both vaccines require 2 doses administered 3-4 weeks apart. All respondents who only entered a cutaneous reaction to the first vaccine dose were sent a follow-up email to solicit the presence/absence of a cutaneous reaction to the second vaccine dose. We contacted providers who entered partially completed records and asked them to complete all fields. We excluded records where the provider was ultimately unable to provide key variables (eg, vaccine brand or those in which vaccine dose elicited a reaction). We used Stata version 16 (StataCorp, LLC) to descriptively analyze data. The Massachusetts General Brigham Institutional Review Board exempted this study as not human subject research.

Results

From December 24, 2020, to February 14, 2021, one or more cutaneous reactions to Moderna (83%) or Pfizer (17%) COVID-19 vaccines were reported by healthcare workers for 414 unique patients (Fig 1 ). Median patient age was 44 years (interquartile range [IQR], 36-59 years), and patients were 90% female, 78% White, and primarily from the United States (98%; Table I ). Cases were reported by dermatologists (30%), other physicians (26%), mid-level practitioners (8.8%), nurses (13%), and other health care workers (22%).

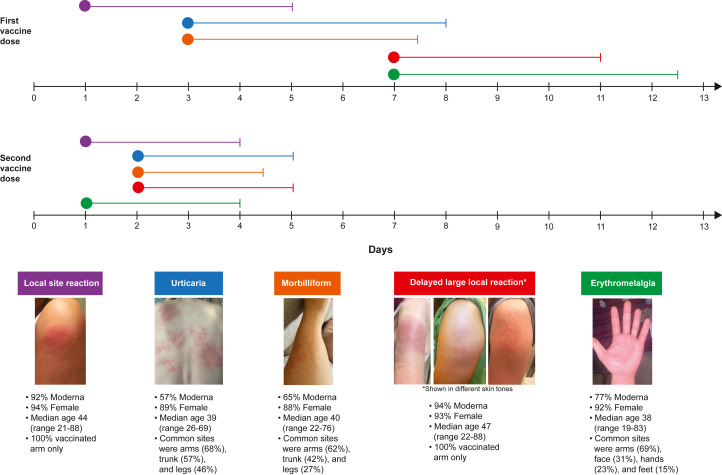

Fig 1.

Timeline representing the time to onset and duration of the top 5 most common dermatologic findings reported after the Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccines. The circles represent median time to onset of the cutaneous reaction and lines represent median duration of the cutaneous reaction. Supplemental Table I (available via Mendeley) provides detailed information about the timing of vaccine reactions.

Table I.

Characteristics of cutaneous reactions reported after Moderna or Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination

| Characteristic | Moderna vaccine unique reports n (%) (n = 343) |

Pfizer vaccine unique reports n (%) (n = 71) |

Total unique reports n (%) (n = 414) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter title | |||

| Dermatologist | 96 (28) | 30 (42) | 126 (30) |

| Other physician | 79 (23) | 29 (41) | 108 (26) |

| Physician assistant | 10 (2.9) | 1 (1.4) | 11 (2.6) |

| Nurse practitioner | 24 (6.9) | 2 (2.8) | 26 (6.2) |

| Nurse | 49 (14) | 5 (7.0) | 54 (13) |

| Other medical professional | 85 (25) | 4 (5.6) | 89 (21) |

| Patient age (median, IQR) | 45 (36-60) | 42 (36-54) | 44 (36-59) |

| Patient sex (female) | 314 (92) | 60 (85) | 374 (90) |

| Patient race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 265 (77) | 57 (80) | 323 (78) |

| Asian | 38 (11) | 8 (11) | 46 (11) |

| Black/African American | 8 (2.3) | 2 (2.8) | 10 (2.4) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 27 (7.9) | 4 (5.6) | 31 (7.5) |

| Unknown | 4 (1.2) | 0 | 4 (1.0) |

| Patient country | |||

| United States | 337 (99) | 66 (93) | 403 (98) |

| Canada | 2 (0.58) | 1 (1.4) | 3 (0.7) |

| Germany | 1 (0.3) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (0.5) |

| Israel | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Italy | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| United Kingdom | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Puerto Rico | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| Guam | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| Prior SARS-CoV-2 infection | |||

| No | 272 (79) | 46 (65) | 318 (77) |

| PCR+ | 7 (2.0) | 4 (5.6) | 11 (2.7) |

| Antibody+ | 2 (0.6) | 2 (2.8) | 4 (1.0) |

| Laboratory + but type unknown | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| Clinical suspicion only | 10 (2.9) | 2 (2.8) | 12 (2.9) |

| Unknown | 51 (15) | 17 (24) | 68 (16) |

| Past dermatologic history | |||

| None | 296 (86) | 53 (75) | 349 (84) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 12 (3.5) | 5 (7.0) | 17 (4.1) |

| Contact dermatitis | 10 (2.9) | 2 (2.8) | 12 (2.9) |

| Psoriasis | 6 (1.7) | 3 (4.2) | 9 (2.2) |

| Urticaria | 5 (1.5) | 2 (2.8) | 7 (1.7) |

| Acne vulgaris | 4 (1.2) | 2 (2.8) | 6 (1.4) |

| Other | 10 (2.9) | 4 (5.6) | 14 (3.4) |

| Vaccine allergy history | |||

| None | 316 (92) | 64 (90) | 380 (92) |

| Prior local site reaction | 11 (3.2) | 2 (2.8) | 13 (3.1) |

| Prior urticaria | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 2 (0.5) |

| Other | 3 (0.9) | 1 (1.4) | 4 (1.0) |

| Unknown | 12 (3.5) | 4 (5.6) | 16 (3.9) |

| Past medical history | |||

| None | 210 (61) | 46 (65) | 256 (62) |

| Hypertension | 55 (16) | 8 (11) | 63 (15) |

| Obstructive lung disease | 18 (5.2) | 2 (2.8) | 20 (4.8) |

| Morbid obesity | 14 (4.1) | 3 (4.2) | 17 (4.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14 (4.1) | 1 (1.4) | 15 (3.6) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 8 (2.3) | 2 (2.8) | 10 (2.4) |

| Rheumatologic disease | 6 (1.7) | 4 (5.6) | 10 (2.4) |

| Malignancy | 5 (1.5) | 3 (4.2) | 8 (1.9) |

| Other | 29 (8.5) | 11 (15) | 40 (10) |

| Unknown | 18 (5.2) | 1 (1.4) | 19 (4.6) |

IQR, Interquartile range; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; +, positive.

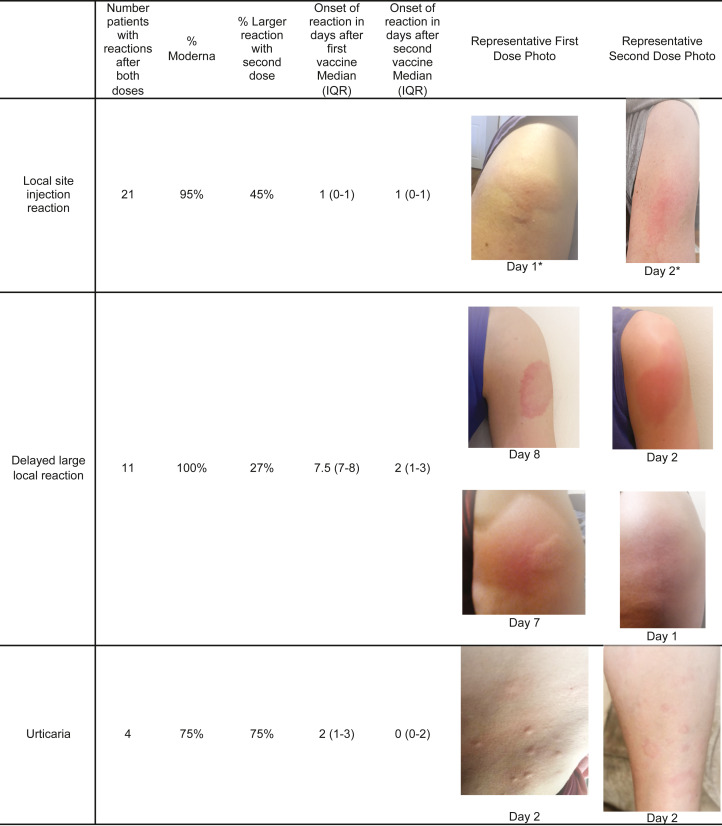

Of the 414 patient records reviewed, information about both vaccine doses was available for 180 (43% of cases). Of these, 38/180 (21%) reported reactions after the first dose only, 113/180 (63%) reported a reaction after the second dose only, and 29/180 (16%) reported reactions to both doses (Supplemental Fig 1 available via Mendeley at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/3t4zn67nc4). Therefore, of the 67 patients who had a cutaneous reaction to the first dose, 29 (43%) also had a cutaneous reaction to the second dose. Of these 29 patients who reported reactions after both doses, 8 (28%) reported similar reactions to both doses, 8 (28%) reported a lesser reaction to the second dose, and 13 (45%) reported a more robust reaction to the second dose (Fig 2 ).

Fig 2.

A depiction of the characteristics of the subset of patients who experienced the same dermatologic finding after both the first and second COVID-19 vaccine doses. No patient experienced anaphylaxis or another severe adverse event after the second COVID-19 vaccine dose. ∗Different patient photos are used for local site injection reaction photos. All other photos follow individual patients' reaction after vaccine dose 1 and dose 2.

There were 343 unique reports of cutaneous manifestations after the Moderna vaccination, including 267 reported after the first dose and 102 reported after the second dose. The most common cutaneous reactions were delayed large local reactions (n = 175 first; n = 31 second dose), local injection site reaction (n = 117 first dose; n = 69 second dose), urticaria (n = 16 first dose; n = 7 second dose), morbilliform (n = 11 first dose; 7 second dose), and erythromelalgia (n = 5 first dose; n = 6 second dose; Table II ). Of the 343 patients with cutaneous manifestations, only reactions to the first dose were recorded for 215 (63%) patients, of whom 203 (94%) planned to receive the second dose and 12 (5.6%) did not plan to receive the second dose due to concerns regarding their first-dose cutaneous reactions. Of those who reported information for both doses (n = 130), 28 (22%) reported a reaction to the first dose only, 76 (58%) reported a reaction to the second dose only, and 26 (20%) reported reactions to both doses.

Table II.

Dermatologic findings reported after the Pfizer or Moderna COVID-19 vaccines. Patients who reported dermatologic findings after both vaccine doses are counted in both the first-dose and second-dose columns (n = 29)

| Characteristic | Moderna first dose (n = 267) n (%) | Moderna second dose (n = 102) n (%) | Pfizer first dose (n = 34) n (%) | Pfizer second dose (n = 40) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutaneous reactions∗,† | ||||

| Delayed large local reaction | 175 (66) | 31 (30) | 5 (15) | 7 (18) |

| Local injection site reaction | 143 (54) | 71 (70) | 8 (24) | 10 (25) |

| Swelling | 117 (44) | 69 (68) | 6 (18) | 6 (15) |

| Erythema | 132 (49) | 68 (67) | 6 (18) | 8 (20) |

| Pain | 94 (35) | 60 (59) | 8 (24) | 7 (18) |

| Urticaria within 24 hours | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 0 | 1 (2.5) |

| Urticaria after 24 hours | 13 (4.8) | 5 (4.9) | 9 (26) | 7 (18) |

| Urticaria unknown timing | 3 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Morbilliform | 11 (4.1) | 7 (6.9) | 6 (18) | 3 (7.5) |

| Erythromelalgia | 5 (1.9) | 6 (5.9) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (5.0) |

| Flare of existing dermatologic condition‡ | 3 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) | 8 (24) | 3 (7.5) |

| Vesicular | 4 (1.5) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (8.8) | 2 (5.0) |

| Pernio/chilblains | 3 (1.1) | 0 | 3 (8.8) | 2 (5.0) |

| Zoster (VZV) | 5 (1.9) | 0 | 1 (2.9) | 4 (10) |

| Angioedema | 5 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.5) |

| Pityriasis rosea | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 2 (5.9) | 1 (2.5) |

| Erythema multiforme | 3 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Filler reaction | 3 (1.1) | 5 (4.9) | 0 | 1 (2.5) |

| Vasculitis | 2 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (2.9) | 0 |

| Contact dermatitis | 3 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 2 (5.0) |

| Reaction in breastfed infant | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 2 (5.9) | 1 (2.5) |

| Onset of new dermatologic condition§ | 2 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 2 (5.0) |

| Petechiae | 1 (0.4) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (2.9) | 0 |

| Other‖ | 7 (2.6) | 8 (7.8) | 2 (5.9) | 3 (7.5) |

| Systemic reactions in patients reporting cutaneous reactions | ||||

| Fatigue | 58 (22) | 63 (62) | 11 (32) | 13 (33) |

| Myalgia | 55 (21) | 63 (62) | 10 (29) | 10 (25) |

| Headache | 46 (17) | 54 (53) | 9 (26) | 6 (15) |

| Fever | 18 (6.7) | 42 (41) | 4 (12) | 4 (10) |

| Arthralgia | 16 (6.0) | 28 (27) | 5 (15) | 8 (20) |

| Nausea | 15 (5.6) | 28 (27) | 4 (12) | 3 (7.5) |

| Chills | 14 (5.2) | 47 (46) | 4 (12) | 5 (13) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 13 (4.9) | 9 (8.8) | 2 (5.9) | 3 (7.5) |

| Diarrhea | 9 (3.4) | 4 (3.9) | 1 (2.9) | 0 |

| Other¶ | 10 (3.7) | 10 (10) | 4 (12) | 1 (2.5) |

PCR, Polymerase chain reaction.

Providers were able to check off multiple dermatologic conditions in each patient.

A subset of patients reporting vaccine reactions had prior laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, including 11 who were PCR+ and 4 who were antibody+. Cutaneous reactions for these patients included local injection site reactions (n = 5), delayed large local reactions (n = 3), urticaria (n = 2), morbilliform eruption (n = 1), pernio/chilblains (n = 1), erythromelalgia (n = 1), erythema multiforme (n = 1), pityriasis rosea (n = 1), and reaction in breastfed infant (n = 1).

Includes flare of herpes simplex virus (n = 4), atopic dermatitis (n = 2), psoriasis (n = 2), urticarial vasculitis (n = 1), and unspecified eczema (n = 2).

Includes Raynaud's (n = 2), lichen planus (n = 1), and unspecified eczema (n = 1).

Other cutaneous first-dose reactions included full-body skin pain/burning (n = 2), hypopigmentation (n = 2), Sweet's-like fixed urticarial plaque (n = 1), pseudovesiculated patches (n = 2), and spongiotic dermatitis (n = 1). Other cutaneous second-dose reactions included canker sore on tongue (n = 1), aphthous ulceration on labium (n = 1), monomorphic papular eruption (n = 2), eczematous pigmented purpura (n = 1), spongiotic dermatitis (n = 1), and full-body skin pain/burning (n = 2).

Other systemic reactions included vomiting (n = 4, first dose; n = 3, second dose), nasal congestion (n = 4; n = 3), arm tingling/numbness (n = 2; n = 1), syncope (n = 1; n = 2), dizziness (n = 1; n = 2), hot flashes (n = 1; first dose only), metallic taste in mouth (n = 1; first dose only), and hematuria (n = 1; second dose only).

There were 71 reports of Pfizer vaccine cutaneous manifestations, including 34 after the first dose and 40 after the second dose. The most common were urticaria (n = 8, first dose; n = 6, second dose), local injection site reaction (n = 8, first dose; n = 8, second dose), and morbilliform rash (n = 6, first dose; n = 3, second dose). Of the 71 cases with cutaneous manifestations, only reactions to the first dose were recorded for 21 (30%). These included patients who were planning to receive their second dose (n = 12) and patients not planning to receive their second dose (n = 4) because of concerns regarding their first cutaneous reactions. Of 50 patients with information entered for both Pfizer doses, 10 (20%) reported reactions after the first dose only, 37 (74%) after the second dose only, and 3 (6.0%) after both doses.

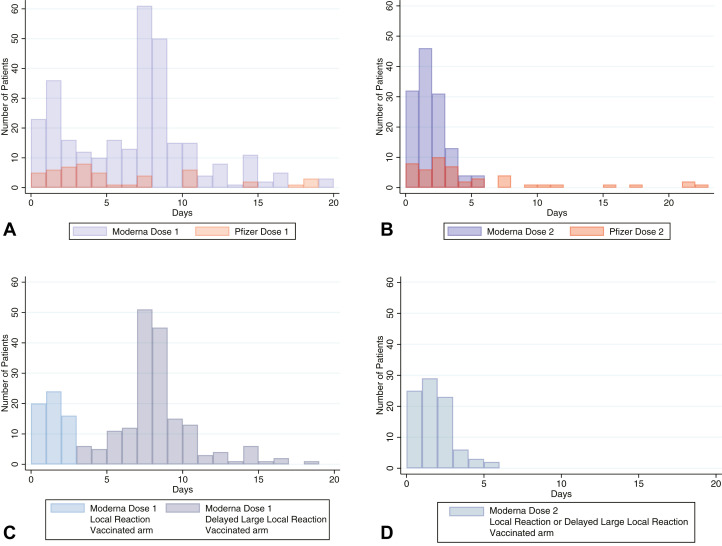

Of the 414 records, 350 (85%) had timing information. The median time from first vaccination to onset of cutaneous symptoms was 7 days (IQR 2-8), which occurred in 2 clusters, one between days 1 and 3 and the other between days 7 and 8 (Fig 3 ). The majority of timing data came from patients with reactions on the vaccinated arm only, with local injection site reaction occurring a median of 1 day (IQR 0-1) and delayed large local reactions occurring median 7 days (IQR 7-8) after vaccination (Supplemental Table I available via Mendeley at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/3t4zn67nc4). The median time from second-dose vaccination to cutaneous symptom onset was shorter, occurring at day 1 (IQR 1-2). No urticaria or angioedema reports after the first dose were immediate in onset; all came after 1 day or more. Of 18 patients who reported urticaria after their first vaccine dose for which information about their second vaccine dose was entered, urticaria developed only in 4 (22%) after their second dose, with most (n = 3) reporting more widespread urticaria.

Fig 3.

Number of days from vaccination (day 0) until the development of a cutaneous reaction after COVID-19 vaccine. A and B, First- and second-dose dermatologic findings, respectively, after Moderna (purple) or Pfizer (orange) vaccination. C and D, First- and second-dose findings, respectively, restricted to patients who received Moderna and experienced the development of a rash on the vaccinated arm, showing local injection site reactions (light blue) and delayed large local symptoms (dark blue). A,Top left. B,Top right. C,Bottom left. D,Bottom right.

Delayed large local arm reactions occurred primarily after Moderna vaccination (94%) at a median of 7 days (IQR 7-8) after the first vaccine and lasted a median of 4 days (IQR 3-6; Fig 3). The reaction occurred more quickly after the second vaccine dose, at a median of 2 days (IQR 1-3) and lasted a median of 3 days (IQR 2-5). For patients who had delayed large local reactions after both doses (n = 11), 3 (27%) had a larger reaction with the second dose. A smaller group of patients who did not have any cutaneous reaction after the first vaccine dose had a delayed large local reaction to the second dose (n = 23), which occurred a median of 2 days (IQR 1-3) after the second vaccination. One hundred sixteen of the 207 (56%) patients with delayed large local reactions also had preceding local site injection reactions.

Less common reports of other cutaneous findings with both vaccines included 9 reports of swelling at the site of cosmetic fillers, 8 pernio/chilblains, 10 varicella zoster, 4 herpes simplex flares, 4 pityriasis rosea-like reactions, and 4 rashes in infants of vaccinated breastfeeding mothers.

Discussion

In this registry-based study, we characterized the morphology and timing of cutaneous reactions for the novel Moderna and Pfizer mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. We observed a broad spectrum of reported reactions after vaccination, from local injection site reactions and delayed large local reactions, to urticaria and morbilliform eruptions, to more unusual reactions, such as erythromelalgia, pernio/chilblains, filler reactions, and pityriasis-rosea-like eruptions. Of 67 patients with cutaneous findings after the first dose and in whom information on both doses was available, only 29 (43%) showed cutaneous symptoms after the second dose. This analysis should provide reassurance to health care providers counseling patients who had a cutaneous reaction after the first dose of Moderna or Pfizer vaccine regarding their second dose, as there were no cases of anaphylaxis or other serious adverse events.5

The most commonly reported cutaneous finding after vaccine administration was a delayed large local reaction a median of 7 days after the first vaccine dose, primarily after Moderna (94%). Second-dose delayed reactions generally occurred more quickly (day 2) and were generally lesser. Similarly, the Moderna clinical trial described 0.8% participants in whom delayed large local reactions developed from the first dose after day 8, and only 0.2% of participants experienced a reaction with the second dose but did not link the reactions from 1 dose to another and, thus, would have missed detecting it if patients reacted more quickly to the second dose.1 , 6 Rarely, delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions have been described after vaccination, with symptoms such as large localized swelling, skin nodules, and/or induration. These reactions, thought to be mediated by T cells, have been attributed to ingredients such as neomycin or thimersol and have not been considered as a contraindication to subsequent vaccination.4 Although the etiology of these delayed large local reactions due to the Moderna vaccine is unclear, a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to the excipient polyethylene glycol is 1 potential etiology.6

In our registry, no severe sequelae were identified after the second dose in patients experiencing a delayed large reaction after the first dose. Patients responded well to topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, and/or pain-relieving medications. These reactions resolved after a median of 3-4 days. Antibiotics were not required for resolution but were sometimes given by providers concerned that the reaction might be cellulitis, as reported elsewhere.7 Taken together, these data provide reassurance to clinicians tasked with counseling patients who have experienced a delayed cutaneous arm reaction after their first Moderna dose that (1) patients tolerated the second dose without experiencing severe adverse or allergic events, (2) the rash may recur the second time but is, on average, likely to be less severe and may develop faster, and (3) symptomatic therapies (eg, ice/pain-relief/antihistamines/topical corticosteroids) can be used for treatment without antibiotics.

We additionally observed reactions to Moderna and Pfizer vaccines that had been noted after the SARS-CoV-2 infection itself, including pernio/chilblains (eg, “COVID toes”), erythromelalgia, and pityriasis-rosea-like exanthems.3 , 8 , 9 That these exanthems mimic dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19 potentially suggests that (1) the host immune response to the virus is being replicated by the vaccine and (2) some components of these dermatologic manifestations of the virus are likely to be from an immune response to the virus rather than direct viral effects.10 , 11 Erythromelalgia and pityriasis rosea have been noted in response to other vaccines, such as those for influenza and hepatitis B, although not commonly.12, 13, 14

We additionally identified rare patients with facial swelling after both Moderna and Pfizer vaccines, which were associated with prior use of injectable cosmetic filler. This phenomenon was similarly described in 3 subjects in Moderna trial reporting; Pfizer did not report any such cases.1 These reactions may represent a delayed hypersensitivity to filler following the introduction of an immunologic trigger,15 and have been previously noted after other viral illnesses16 and influenza vaccines.1 , 17

It is important to distinguish immediate hypersensitivity reactions, defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as including pruritus, urticaria, flushing, and angioedema occurring within the first 4 hours of an injection, from similar reactions that occur >4 hours after injection.18 This distinction is particularly relevant for urticaria and angioedema, which are potential contraindications for a second vaccine dose.18 Although this registry captured time between vaccination and skin reaction in days rather than hours, none of the first-dose urticaria reports or angioedema reports occurred on the day of vaccination and, therefore, would not be classified as immediate hypersensitivity. Of the 18 urticaria reports where information was available for both vaccine doses, only 4 had urticaria with their second dose and none reported anaphylaxis, which should provide reassurance regarding patients in whom urticaria develops >4 hours after first vaccination. Importantly, allergic cutaneous symptoms reported in this study, such as urticaria, angioedema, and/or morbilliform eruptions, may not be caused by allergy to the vaccine but instead related to host immune response or an immunologic reaction to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents commonly taken for pain and fever after vaccination.

Another limitation of this registry analysis includes an incomplete record follow-up. Because providers only enter data at 1 point in time, patients have differential lengths of follow-up. To overcome this, we reached out via email to all providers after such patients received second doses; nevertheless, we still mostly report information regarding first vaccine dose reactions. Reporting on the second vaccine dose may be more common when there are symptoms (rather than no reaction) to report. As such, this reporting bias might result in our study demonstrating a “worst case scenario” for the second dose. Still, less than half of patients had recurrence with the second dose. An additional limitation is that the morphology description of vaccine reactions is provider dependent. Future studies are needed to classify morphologies with objectively classifiable clinical images and histopathologic evaluation.

We are unable to measure the incidence of cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccination through a registry-based study, which lacks a denominator. There may be confirmation bias, as providers were more likely to enter cases with severe or rare manifestations. The registry noted 343 reactions from the Moderna vaccine and only 71 from the Pfizer vaccine, but it will require further population-level data to understand whether this is a true difference or related to reporting bias. As of February 22, 2021, 53% of allocated vaccine doses in the United States were Moderna and 47% were Pfizer.19 , 20

Ninety percent of the vaccine reactions were reported in female patients. It is difficult to assess whether there is a true sex-related difference in the likelihood of the development of a cutaneous reaction or whether it might reflect reporting bias or stem from the health care workforce being 76% female.21 Further, vaccine reactions in this registry were primarily in White (78%) patients, which highlights important concerns about disparities in vaccine access, health care access after experiencing a potential side effect, differential likelihood of reporting to the registry, and/or recognition of skin reactions by health care providers in patients with skin of color.22 , 23 Patients were primarily located in the United States (98%); at this time, there were no reports in the registry of cutaneous reactions from patients in low- and middle-income countries, raising attention to global inequities in COVID-19 vaccine access.24

We characterize a spectrum of cutaneous reactions reported with novel mRNA vaccines for COVID-19. Certain dermatologic findings echo prior vaccine hypersensitivity knowledge, while newer findings, such as delayed large local reactions to the Moderna vaccine and filler reactions may suggest new immunologic mechanisms. Pernio/chilblains post vaccine may suggest an immunologic connection to infection with SARS-CoV-2.8 , 9

Conclusions

Overall, our data support that cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccination are generally minor and self-limited and should not discourage vaccination.1 , 2 Presence of a cutaneous reaction to the first vaccine dose, when it appears >4 hours after injection, is not a contraindication to receiving the second dose of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine. No patients with these findings experienced anaphylaxis or another severe adverse event. Health care workers must be aware of these potential vaccine reactions and advise patients accordingly. Counseling patients about potential benefits of receiving a COVID-19 vaccine is equally, if not more, important.

Conflicts of interest

Drs Freeman, Hruza, Rosenbach, Lipoff, and Fox are members of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) COVID-19 Ad Hoc Task Force. Dr French is the President and Dr Lim is a board member of the International League of Dermatological Societies. Dr Thiers is the President of the American Academy of Dermatology. Dr Freeman is an author of COVID-19 dermatology for UpToDate. Drs Amerson, Desai, and Blumenthal and authors McMahon, Moustafa, and Tyagi have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the following individuals for providing clinical photographs: Latasha Jackson, Audrey Fetch, Stephanie Cebreros-Rosales, Su Luo, Josette McMichael, Jaquelyn Saban, Anne Pylkas, and Gina Sevigny. The authors also thank Grace Chamberlin at Massachusetts General Hospital for her assistance with the administration of the COVID-19 Dermatology Registry and all the health care providers worldwide who entered cases in this registry.

Footnotes

Funding sources: COVID-19 registry support provided to Massachusetts General Hospital by the International League of Dermatological Societies for administration and maintenance and by the American Academy of Dermatology for in-kind administrative support.

IRB approval status: Exempt. The registry was reviewed by the Partners Healthcare (Massachusetts General Hospital) Institutional Review Board and was determined to not meet the definition of human subject research.

References

- 1.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman E.E., McMahon D.E., Lipoff J.B., et al. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelso J.M., Greenhawt M.J., Li J.T., et al. Adverse reactions to vaccines practice parameter 2012 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(1):25–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimabukuro T.T., Cole M., Su J.R. Reports of anaphylaxis after receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in the US-December 14, 2020-January 18, 2021. JAMA. 2021;325(11):1101–1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerji A., Wickner P.G., Saff R., et al. mRNA vaccines to prevent COVID-19 disease and reported allergic reactions: current evidence and suggested approach. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;9(4):1423–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.12.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumenthal K.G., Freeman E.E., Saff R.R., et al. Delayed large local reactions to mRNA-1273 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(13):1273–1277. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2102131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman E.E., McMahon D.E., Lipoff J.B., et al. The spectrum of COVID-19-associated dermatologic manifestations: an international registry of 716 patients from 31 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(4):1118–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galvan Casas C., Catala A.C., Carretero Hernandez G., et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(1):71–77. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welsh E., Cardenas-de la Garza J.A., Cuellar-Barboza A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein positivity in pityriasis rosea-like and urticaria-like rashes of COVID-19. Br J Dermatol. 2021 doi: 10.1111/bjd.19833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colmenero I., Santonja C., Alonso-Riano M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 endothelial infection causes COVID-19 chilblains: histopathological, immunohistochemical and ultraestructural study of 7 paediatric cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(4):729–737. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamada K., Gleason S.L., Levi B.Z., et al. H-2RIIBP, a member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that binds to both the regulatory element of major histocompatibility class I genes and the estrogen response element. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(21):8289–8293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Confino I., Passwell J.H., Padeh S. Erythromelalgia following influenza vaccine in a child. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1997;15(1):111–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabaud C., Barbaud A., Trechot P. First case of erythermalgia related to hepatitis B vaccination. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(1):233–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rice S.M., Ferree S.D., Atanaskova Mesinkovska N., et al. The art of prevention: COVID-19 vaccine preparedness for the dermatologist. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(2):209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turkmani M.G., De Boulle K., Philipp-Dormston W.G. Delayed hypersensitivity reaction to hyaluronic acid dermal filler following influenza-like illness. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:277–283. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S198081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munavalli G.G., Guthridge R., Knutsen-Larson S., et al. COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 virus spike protein-related delayed inflammatory reaction to hyaluronic acid dermal fillers: a challenging clinical conundrum in diagnosis and treatment. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021;30(1):53–59. doi: 10.1007/s00403-021-02190-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines Currently Authorized in the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/clinical-considerations.html Available at:

- 19.COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution Allocations by Jurisdiction - Moderna Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://data.cdc.gov/Vaccinations/COVID-19-Vaccine-Distribution-Allocations-by-Juris/b7pe-5nws Available at:

- 20.COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution Allocations by Jurisdiction - Pfizer Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://data.cdc.gov/Vaccinations/COVID-19-Vaccine-Distribution-Allocations-by-Juris/saz5-9hgg Available at:

- 21.Your Health Care Is in Women's Hands United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/08/your-health-care-in-womens-hands.html Available at:

- 22.Demographic Characteristics of People Receiving COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-demographic Available at:

- 23.Buster K.J., Stevens E.I., Elmets C.A. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baraniuk C. How to vaccinate the world against covid-19. BMJ. 2021;372:n211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]