Abstract

Objectives:

To estimate county-level adult life expectancy for Whites, Black/African Americans (Black), American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) and Asian/Pacific Islander (Asian) populations and assess the difference across racial groups in the relationship among life expectancy, rurality and specific race proportion.

Methods:

We used individual-level death data to estimate county-level life expectancy at 25 (e25) for Whites, Black, AIAN and Asian in the contiguous US for 2000–2005. Race-sex-stratified models were used to examine the associations among e25, rurality and specific race proportion, adjusted for socioeconomic variables.

Results:

Lower e25 was found in the central US for AIANs and in the west coast for Asians. We found higher e25 in the most rural areas for Whites but in the most urban areas for AIAN and Asians. The associations between specific race proportion and e25 were positive or null for Whites, but were negative for Blacks, AIAN, and Asians. The relationship between specific race proportion and e25 varied across rurality.

Conclusions:

Identifying differences in adult life expectancy, both across and within racial groups, provides new insights into the geographic determinants of life expectancy disparities.

Keywords: Life expectancy at age 25, rurality, American Indian/Alaska Native population, Asian/Pacific Islander population, specific race proportion, contiguous US

Introduction

Large disparities in life expectancy in the United States (US) have been observed across races and geographic areas. Between races in the US, Black and Asian populations demonstrated the largest difference in life expectancy at birth (e0), which was about 12 years in 2009 (Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation 2009). The difference in e0 was about 5 years between Black and White populations (Levine et al. 2001; National Center for Health Statistics 2016; Crimmins and Saito 2001; Harper et al. 2007). Across geographies, county-level differences in e0 between the best-off and worst-off counties was about 18 years for Black males, 14 years for Black females, 15 years for White males, and 11 years for White females in 2001 (Murray et al. 2006).

Although county-level life expectancy for Whites and Black/African Americans (Black) has been reported, very little is known for American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) and Asian/Pacific Islanders (Asian). Studies of life expectancy usually pool AIAN and Asians at the national/regional levels (Crimmins and Saito 2001; Murray et al. 2006), or pool them by socioeconomic status (Singh and Siahpush 2014; Singh and Siahpush 2006), or exclude them all together. However, the determinants of life expectancy for Asian and/or AIAN populations may differ from Whites and Blacks and may also vary geographically. Life expectancy estimates at a geographic unit other than the national level (e.g., county-level) for AIANs and Asians would enable a better understanding of their health status and potential disparities in these racial groups that have been under-studied.

Individual factors, such as income and education, are linked with variations in life expectancy (Singh and Siahpush 2006; Chetty et al. 2016). However, less is understood about area-level measures (such as rurality) that may represent differential environmental exposures and thus potentially influence life expectancy. Limited studies in the US have explored the differences in life expectancy across the rural-urban gradient. Singh and Siahpuch (2014) found higher e0 in metropolitan areas compared to non-metropolitan areas. However, Geronimus et al. (2001) found life expectancy at age 16 (e16) was higher in rural areas for Black and Whites. Besides contrasting results, the causes of the rural-urban disparities remain unclear, motivating further investigations into life expectancy across the rural-urban gradient.

Another area-level variable potentially influencing life expectancy is the proportion of a given race residing in a neighborhood, which we will refer to as the specific race proportion. This race proportion matters for understanding the geographic determinants of mortality because while mortality rates differ by race, so do the factors that may contribute to mortality differentials, such as investment in neighborhood resources and health promotion infrastructure (Jackson et al. 2000; Inagami et al. 2006). A few studies have reported proportions of the same race were linked with race-specific mortality, but the results were inconsistent (Jackson et al. 2000; Inagami et al. 2006; Fang et al. 1998; Hutchinson et al. 2009). The relationship between specific race proportion and life expectancy has rarely been assessed previously and needs further investigation.

In this study we addressed these questions by (1) estimating county-level life expectancy at age 25 (e25) in the contiguous US for Whites, Blacks, AIAN, and Asians, and investigating the geographic patterns in e25; (2) assessing the differences in life expectancy across rurality (defined by Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (United States Department of Agriculture 2016)); (3) assessing the associations between life expectancy and county-level specific race proportion (county-level proportion of a given race, same-race%); and (4) examining potential interactions between rurality and specific race proportion for Whites and Blacks.

Methods

Data for mortality, population, rurality, and other sociodemographic variables

Individual death data from the National Center for Health Statistics were aggregated as death counts into five-year age groups by county and race-sex groups for the contiguous US for years 2000–2005 (National Center for Health Statistics 2000–2005). We focused on the contiguous US in this study because of the small number of deaths in Alaska and Hawaii and because of the county changes in Alaska that prevented matching county-level mortality and population data during the study period.

We used bridged-race population estimates to calculate five-year mortality rates. The bridged population data mapped 31 race categories, as specified in the 1997 Office of Management and Budget standards for the collection of data on race and ethnicity, to the four race categories specified under the 1977 standards (the same as race categories in mortality registration) (Ingram et al. 2003). Age-specific bridged population estimates for 2000–2005 were obtained from National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results 2016).

The urban-rural gradient was represented by the 2003 Rural Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC), which distinguished metropolitan counties by population size, and nonmetropolitan counties by degree of urbanization and adjacency to a metro area (United States Department of Agriculture 2016). The nine RUCC groups were condensed into four groups as has been done elsewhere: metropolitan urbanized (RUCC1, urban population ≥ 250,000, categories1–3 in the original nine classification), non-metropolitan urbanized (RUCC2, urban population of 20,000 – 250,000, categories 4 and 5 in the original classification), less urbanized (RUCC3, urban population of 2500 −19999, categories 6 and 7 in the original classification), and thinly populated (RUCC4, completely rural, <2500 urban population, categories 8 and 9 in the original classification) areas (Luben et al. 2009; Messer et al. 2010).

We obtained county-level sociodemographic data for 2000–2005 from the US Census Bureau. These included median household income, percent of population attaining greater than high school education (high school%), and percent of county occupied rental units (rent%). We obtained county violent crime from Uniform Crime Reports and used it to calculate mean number of violent crimes per capita (Federal Bureau of Investigation 2010). These four variables were used for confounder control in adjusted models.

Estimation of life expectancy at age 25

In our study we focused on e25 to represent adult life expectancy. County-level e25 was calculated using age-specific death rates for every five-year group starting at age 25. The observed death rates (death counts / population) can be unstable for counties with small populations, which leads to inaccuracy in the estimated life expectancy. Therefore, we used a random slope, random intercept Poisson regression to stabilize the county-level and race-sex specific death rates. We constructed a log-linear model between death rate and age to borrow strength across age groups when estimating age-specific death rate.

The log-linear relationship between death rate and age has been used in other life expectancy work (Chetty et al. 2016) and was observed for our mortality data for age between 25 and 84. We estimated e25 for eight race-sex groups (White, Black, AIAN, Asian, male and females). Ethnicity (Hispanics vs non-Hispanic) was not estimable due to data limitation. To address unstable estimates in many counties for ages over 84, we linearly extrapolated, through age 100–104, the logs of the five-year age-specific mortality rates for ages 25–84 by sex and race. The details of the model for estimating e25 can be found in Electronic Supplementary Materials (EMS). We reported e25 for each sex-race group using median and interquartile range since mortality is not normally distributed.

Statistical analysis

We used linear regression models to assess the relationships among county-level e25, rurality, and specific race proportion: (1) models with only RUCC as the independent variable; (2) models with only specific race proportion as the independent variable (3) models with both specific race proportion and RUCC, adjusted for sociodemographic variables (household income, school%, rent%, and number of violent crimes per capita); and (4) models with RUCC, specific race proportion, and the interaction between RUCC and specific race proportion, also adjusted for sociodemographic variables. Specific race proportion was represented by county-level proportion of a given race (same-race%, for example White% for White population and Black% for Black population). The first three models were run for all the eight race-sex groups and the last model was run only for Whites and Blacks to test our hypothesis that the associations of e25 and specific race proportion may vary across the rural-urban gradient. All models were run separately for the race-sex groups. For the rural-urban gradient, life expectancy in RUCC 2 (non-metro urbanized), RUCC 3 (less populated), and RUCC 4 (thinly populated) was compared against RUCC 1 (metropolitan areas). We assessed models both with and without the adjusting sociodemographic variables and compared their results to check the influence of these variables on the associations among e25, rurality, and specific race proportion; we reported estimates for the adjusted models. Specific race proportion and sociodemographic variables were standardized (mean=0 and standard deviation = 1) prior to inclusion in the model to ensure the comparability among the model coefficients (Table EMS1). Thus, the results were presented as the change in life expectancy per one standard deviation change in specific race proportion.

All models were assessed for violations of model assumptions. Counties with fewer than 12 deaths (2 deaths per year per county on average) during 2000–2005 for the sex-race group were excluded (Table EMS2 shows the remaining number of counties for each race-sex group). For sensitivity analyses, we also tested models in which counties with fewer than 72 deaths (6 deaths per year per county on average) during 2000–2005 were excluded, and the results (not shown) were similar. For Asian populations in RUCC 3 (less populated) and 4 (thinly populated), there were fewer than 15 counties with estimated e25. Thus, they were not included in the analyses.

Results

Estimated life expectancy at age 25

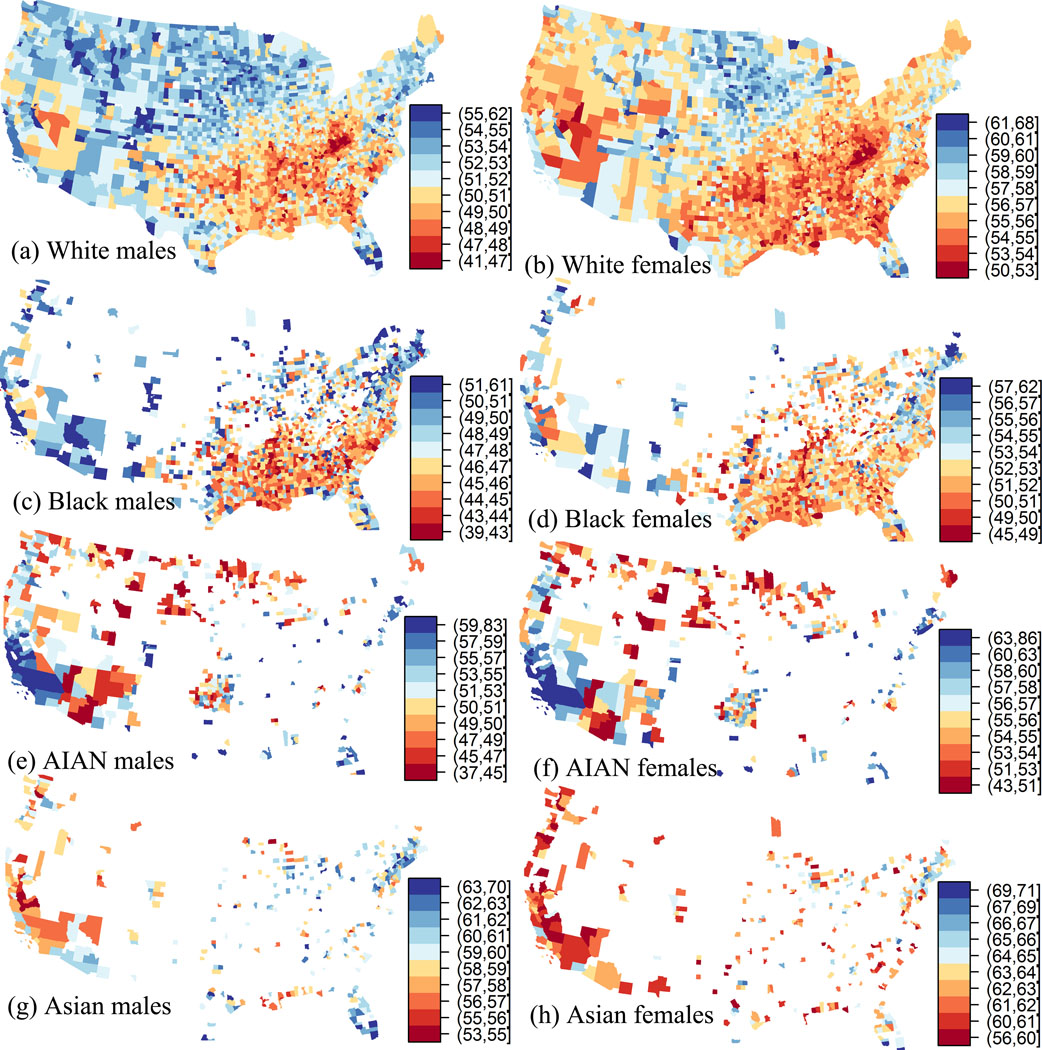

Overall, in the contiguous US, the estimated county-level e25 (mean remaining years of life at age 25) was highest for Asian females: 62.6 years (61.1, 64.3) (median and interquartile range) and lowest for Black males 46.7 years (45.1, 48.8) (Table EMS2). The AIANs had the largest variations in e25 (for both males and females) compared to other race-sex groups (Table EMS2). Geographically, lower e25 for the Whites and Blacks were observed in the southeast (Figure 1). Lower e25 for AIANs was found in the central part of US, and lower e25 for Asians was observed in the western coast for the metropolitan and non-metro urbanized counties (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

County-level life expectancy at age 25 for the contiguous US 2000–2005 (Deciles differed among sex-race groups). White patches: counties with no estimated life expectancy.

Difference of life expectancy at age 25 across urban-rural status

The model with only RUCC showed that for Whites the highest e25 was found in thinly populated areas (RUCC 4), followed by metropolitan areas (RUCC 1). However, for Blacks, AIANs, and Asians, the highest e25 was found in metropolitan areas (RUCC 1) (Table EMS3). The model with RUCC and specific race proportion adjusted for sociodemographic variables, showed a different pattern for the trend of e25 across rurality (Table EMS4). For Whites, we observed a monotonically increasing trend for e25 from the most urban (RUCC1) to the most rural areas (RUCC4). For Blacks, we found that the highest e25 was found in thinly populated areas (RUCC4). The results for AIAN were similarly best in RUCC 4.

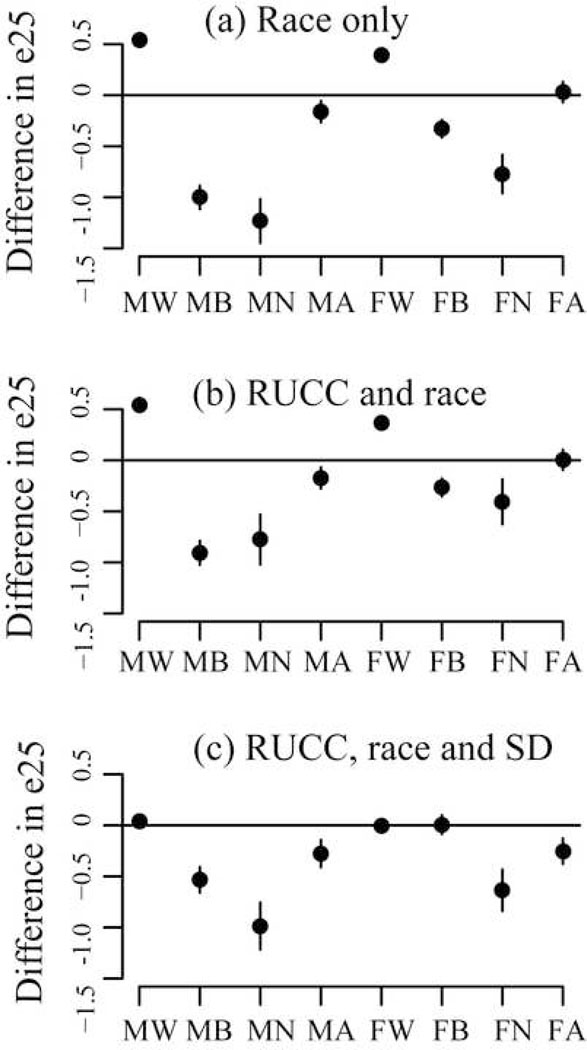

Difference of life expectancy at age 25 across specific race proportion

The model with only specific race proportion resulted in positive associations between e25 and White% for White, but mostly negative associations between e25 and specific race proportion for other groups (Figure 2 and Table EMS5). The negative associations suggested that e25 was lower in counties with larger proportion of the same race. For example, a one standard deviation increase (6.7 percentage points) in AIAN% was associated with −1.2 (−1.4, −1.0) (mean and 95% CI) and −0.8 (−1.0, −0.6) years change in e25 of AIAN males and females, respectively. The model with both RUCC and specific race proportion had similar results with the model with only specific race proportion (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Differences in life expectancy at age 25 (e25) per one standard deviation change in (95% Confidence Interval) specific race proportion from the models for the contiguous US 2000–2005 with (a) specific race proportion only, (b) the models with both Rural Urban Continuum Code (RUCC) and specific race proportion, and (c) the models with RUCC, specific race proportion, and adjusting sociodemographic variables (SD). MW: Male White; MB: Male Black; MN: Male AIAN; MA: Male Asian; FW: Female White; FB: Female Black; FN: Female AIAN; FA: Female Asian

The model with RUCC, specific race proportion, and adjusting sociodemographic variables also showed mostly negative associations between e25 and specific race proportion for Black, AIAN, and Asian populations. However, the associations between e25 and specific race proportion, adjusted for sociodemographic variables, was null for Whites (Figure 2 and Table EMS4).

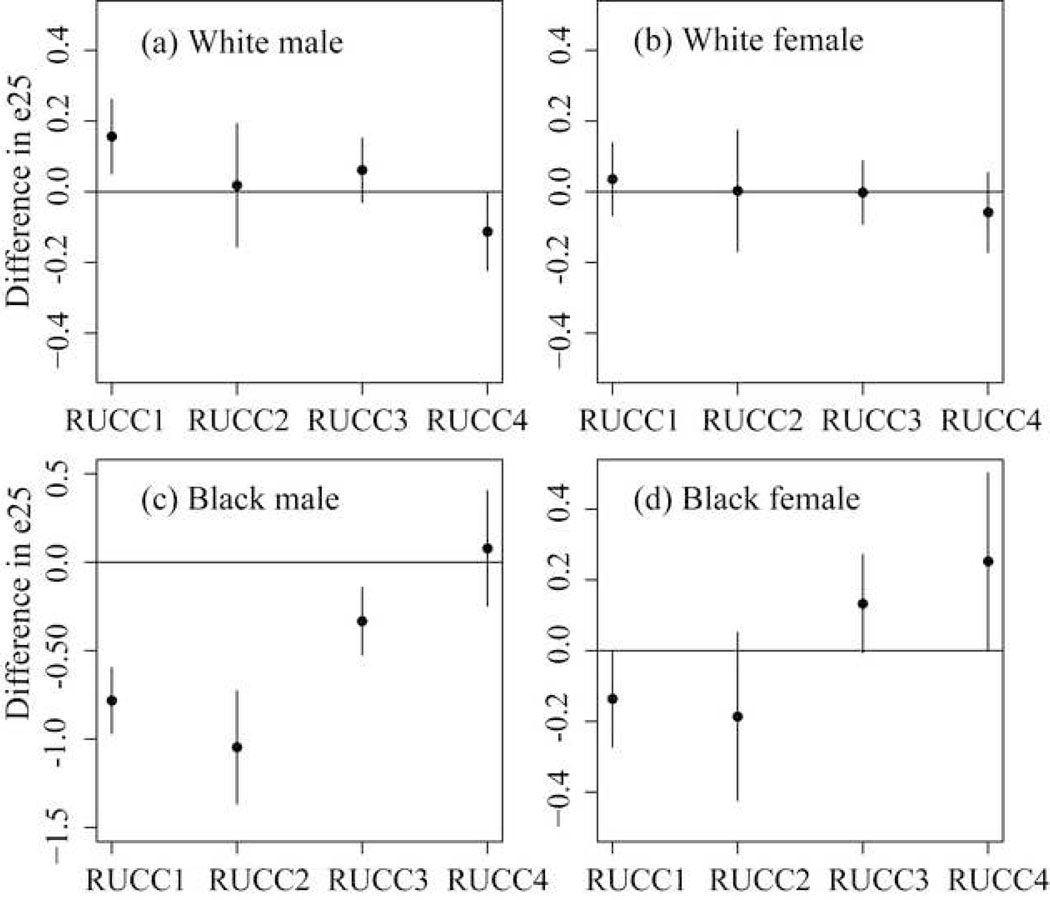

Interactions between rurality and specific race proportion

In the models with interactions between rurality and specific race proportion, adjusted for sociodemographic variables, some statistically significant interactions were observed for both Blacks and Whites (Table EMS6). However, the directionality of the association varied between races, and the net effects were generally more negative for Blacks, particularly in RUCC1 (metropolitan) and RUCC2 (non-metro urbanized) (Table EMS6, Figure 3). For White males, the association between e25 and White% was significantly positive in the metropolitan areas (0.2 (0.1, 0.3)), but significantly negative in thinly populated areas (−0.1 (−0.2, 0.0)). For Black females, the association between e25 and Black% was significantly negative in the metropolitan areas (−0.1 (−0.3, 0.0)), but significantly positive in thinly populated areas (0.3 (0.0, 0.5)). For White females, the e25-racial share association was null in all RUCCs. For Black males, the association was significantly negative in all RUCCs except the thinly populated areas.

Figure 3.

Difference in life expectancy at age 25 (e25) per one standard deviation change (95% Confidence Interval) in specific race proportion across rurality from the interaction models with adjusting variables for the contiguous US 2000–2005. RUCC1: metropolitan areas; RUCC2: non-metro urbanized areas; RUCC3 areas: less populated; RUCC4: thinly populated areas

Discussion

In this study we estimated county-level life expectancy at age 25 (e25) for eight race-sex groups in the contiguous US and modeled the associations among e25, rurality and specific race proportion. We found different trends in e25 across the rural-urban gradient and different relationships between e25 and specific race proportion among Whites, Blacks, AIANs, and Asians. We also observed significant interactions between specific race proportion and rurality, suggesting varying relationships between e25 and specific race proportion in rural and urban areas for Whites and Blacks.

County-level life expectancy for AIANs and Asians has rarely been reported. Our analyses showed, for the first time to our knowledge, the geographic patterns of e25 for AIAN in the contiguous US and Asian populations in metropolitan and non-metro urbanized counties. The difference in the geographic pattern may suggest that the driving factors for life expectancy vary spatially within racial groups.

Wide disparities in the county-level e25 were observed within race-sex groups. For example, the interquartile range was 48.7 to 55.6 for AIAN males and was 53.5 to 59.3 for AIAN females. The magnitude of the within-race difference in e25 was comparable to the between-race difference for both e25 in our study and life expectancy at birth (e0) from previous studies (Harper et al. 2007; Murray et al. 2006) The wide gaps in the county-level e25 suggested large disparities in overall health status within a racial group across geographic locations.

Our results suggest the trend of e25 across rural-urban gradient was different between race groups. Our results for the White and Black populations when adjusting for sociodemographic variables were consistent with the findings of Geronimus et al. (2001) which showed that rural residents outlive urban residents. Unadjusted results (not shown) had been similar to the results of Singh and Siahpuch (2014) for Black population, which found higher life expectancy at birth (e0) in metropolitan areas. However, we observed the highest e25 in the most rural areas for White population, which was different from the results of Singh and Siahpuch (2014). Of note, our study estimated e25 while the study of Geronimus et al. (2001) focused on e16, and Singh and Siahpuch (2014) reported e0. This suggests the trends of overall health status across rural-urban gradient may differ among age groups.

This study also reported the associations between specific race proportion (same-race%) and e25 in the contiguous US and how they varied across rurality. The negative associations between specific race proportion and e25 for Black, AIAN, and Asian populations were consistent with previous studies which showed worse health outcomes in areas with smaller percent of White population (Jackson et al. 2000; Mellor and Milyo 2004; Hart et al. 1998). However, our models with the interaction between specific race proportion and rurality further showed the magnitude and the signs of associations between specific race proportion and e25 were different in the most urban and the most rural areas for White and Black populations.

In our analyses, we adjusted for sociodemographic variables. Compared to unadjusted models, for rurality, these models showed different trends of e25 across rural-urban status for White and Black populations; for specific race proportion, these models had similar results for Black, AIAN, and Asian populations, but different results for White populations. The differences between adjusted and unadjusted models suggest that part of the differences in e25 across rurality and across specific race proportion gradient may be attributed to the sociodemographic variables. Both the adjusted and unadjusted models may misattribute the relationships because the true causal pathways of rural-urban status and specific race proportion on adult life expectancy are unknown. It is possible that including the sociodemographic variables in the model may remove some of the legitimate differences in e25 that are attributable to rurality and specific race proportion. However, we were more concerned that models without sociodemographic adjustment may misattribute the observed associations to rurality or specific racial proportion. For example, if education influences life expectancy and it is also determined by other unmeasured factors (such as regional differences), leaving it unadjusted can result in misleading associations. Therefore, we presented adjusted models.

In most previous studies, life expectancy was estimated using either observed age-specific death rates or age-specific death estimated separately for age groups (Murray et al. 2006; Kulkarni et al. 2011; Dominici et al. 2015). In our study, we assumed a log-linear relationship between death rate and age starting at 25 to pool information across age groups. Additionally, the random intercept and random slope model also allowed us to borrow strength across race, sex and county groups. This method likely produced more robust estimates of life expectancy for counties with small populations and enabled us to estimate county-level e25 for AIANs and Asians which could not be calculated previously.

Our inability to account for individual-level SES is a limitation of this study. Further, macro-level characteristics, such as social security benefits or public welfare systems, may contribute to differential mortality. This study also lacked detailed information about differential migration of individuals. Rural areas may appear healthier as the infirm and disabled may prefer to stay in more urbanized areas with more social services. It is also possible that people who migrate to urban areas for job opportunities are healthier than the average population (Diaz et al. 2016; Schenker et al. 2014). If this is the case, the apparent difference in e25 across urban/rural status may be affected by migration patterns. Further studies comparing life expectancy between the migrating population and non-migrating populations may shed light on this problem.

Another limitation is our inability to address ethnicity (Hispanic vs Non-Hispanic) separately in our analyses. The Hispanic population was estimated to have longer life expectancy than Non-Hispanic White and Non-Hispanic Black populations at the national level (National Center for Health Statistics 2016). However, little is known about their life expectancy at the county-level. We could not separate ethnicity because it was not available in the bridged-race population estimates. Future studies about county-level life expectancy for Hispanic and Non-Hispanic populations will be valuable for understanding their overall health status.

The estimation of e25 in this study relied on the validity of the population and death data used. Misclassifications of race in death certificates have been reported, and the influence of this on the estimated e25 could differ by racial groups (Casper ML et al. 2003; Rosenberg HM et al. 1999). The e25 of Asians and AIANs are more likely to be impacted by misclassification compared to Whites and Black due to their smaller population (Casper ML et al. 2003; Rosenberg HM et al. 1999). This difference in the racial misclassification may also affect our estimated associations between e25, rurality, and specific race proportion.

Conclusions

This study was the first to assess county-level adult life expectancy (e25) for Asians and AIANs, and further highlighted racial heterogeneity in e25 by geographic region, rurality, and specific race proportion. Asians and AIANs had different geographic patterns in e25 and different associations between rurality status and e25, when compared to Whites and Blacks. Specific race proportion was associated with lower e25 for Blacks, AIANs, and Asians, but higher e25 for Whites. Significant interactions were observed between rurality and specific race proportion for Whites and Blacks, suggesting that the relationship between specific race proportion (same-race%) and adult life expectancy varies across rural-urban gradient. The results of this study revealed the wide difference in adult life expectancy both within and between racial groups, providing new insights into the geographic determinants of life expectancy disparities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Office of Research and Development (ORD) partially funded the research with L.C.M. (contracts EP12D000264, EP09D000003 and EP17D000079); J.S.J (contract EP17D000063), Y.J., J.S.J., and C.L.G. were supported in part by an appointment to the Internship/Research Participation Program at Office of Research and Development (NHEERL), U.S. EPA, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. EPA. We also thank Bryan Hubbell, Patricia Murphy, and Stephanie DeFlorio-Barker for their insightful suggestions to this study.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

We used mortality data to calculate life expectancy in this study. Thus, by definition, it is non-human subject research. No human subject ethics approval is needed as determined by the Human Research Protocol Officer from the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, United States Environmental Protection Agency.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. EPA. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Casper ML, Barnett E, Williams GI Jr., Halverson, Braham, KJ G. 2003. Atlas of Stroke Mortality: Racial, Ethnic, and Geographic Disparities in the United States. . Atlanta, GA:Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. 2016. THe association between income and life expectancy in the united states, 2001–2014. JAMA 315(16): 1750–1766. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, Saito Y. 2001. Trends in healthy life expectancy in the United States, 1970–1990: gender, racial, and educational differences. Social Science & Medicine 52(11): 1629–1641. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00273-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz CJ, Koning SM, Martinez-Donate AP. 2016. Moving Beyond Salmon Bias: Mexican Return Migration and Health Selection. Demography 53(6): 2005–2030. 10.1007/s13524-016-0526-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominici F, Wang Y, Correia AW, Ezzati M, Pope CA, Dockery DW. 2015. Chemical Composition of Fine Particulate Matter and Life Expectancy: In 95 US Counties Between 2002 and 2007. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 26(4): 556–564. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Madhavan S, Bosworth W, Alderman MH. 1998. Residential segregation and mortality in New York City. Social Science & Medicine 47(4): 469–476. 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00128-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2010. Uniform Crime Reporting. Available at https://ucr.fbi.gov/.

- Geronimus AT, Bound J, Waidmann TA, Colen CG, Steffick D. 2001. Inequality in life expectancy, functional status, and active life expectancy across selected black and white populations in the United States. Demography 38(2): 227–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper S, Lynch J, Burris S, Davey Smith G. 2007. Trends in the black-white life expectancy gap in the united states, 1983–2003. JAMA 297(11): 1224–1232. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.11.1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart KD, Kunitz SJ, Sell RR, Mukamel DB. 1998. Metropolitan governance, residential segregation, and mortality among African Americans. American journal of public health 88(3): 434–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. 2009. Life Expectancy at Birth (in years). Available: http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/life-expectancy-by-re/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

- Hutchinson RN, Putt MA, Dean LT, Long JA, Montagnet CA, Armstrong K. 2009. Neighborhood racial composition, social capital and black all-cause mortality in Philadelphia. Social Science & Medicine 68(10): 1859–1865. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagami S, Borrell LN, Wong MD, Fang J, Shapiro MF, Asch SM. 2006. Residential Segregation and Latino, Black and White Mortality in New York City. Journal of Urban Health : Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 83(3): 406–420. 10.1007/s11524-006-9035-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram DD, Parker JD, Schenker N, Weed JA, Hamilton B, Arias E, et al. 2003. United States Census 2000 population with bridged race categories. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2(135). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_135.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SA, Anderson RT, Johnson NJ, Sorlie PD. 2000. The relation of residential segregation to all-cause mortality: a study in black and white. American journal of public health 90(4): 615–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni SC, Levin-Rector A, Ezzati M, Murray CJ. 2011. Falling behind: life expectancy in US counties from 2000 to 2007 in an international context. Population Health Metrics 9(1): 16. 10.1186/1478-7954-9-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine RS, Foster JE, Fullilove RE, Fullilove MT, Briggs NC, Hull PC, et al. 2001. Black-white inequalities in mortality and life expectancy, 1933–1999: implications for healthy people 2010. Public Health Reports 116(5): 474–483. 10.1093//phr/116.5.474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luben TJ, Messer LC, Mendola P, Carozza SE, Horel SA, Langlois PH. 2009. Urban–rural residence and the occurrence of neural tube defects in Texas, 1999–2003. Health & Place 15(3): 863–869. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor JM, Milyo JD. 2004. Individual Health Status and Racial Minority Concentration in US States and Counties. American journal of public health 94(6): 1043–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer LC, Luben TJ, Mendola P, Carozza SE, Horel SA, Langlois PH. 2010. Urban-Rural Residence and the Occurrence of Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate in Texas, 1999–2003. Annals of Epidemiology 20(1): 32–39. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Kulkarni SC, Michaud C, Tomijima N, Bulzacchelli MT, Iandiorio TJ, et al. 2006. Eight Americas: investigating mortality disparities across races, counties, and race-counties in the United States. PLoS Med 3(9): e260. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results. 2016. U.S. Population data - 1969–2014. Available: http://seer.cancer.gov/popdata/.

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2000–2005. [PubMed]

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2016. Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. . Hyattsville, MD. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg HM, Maurer JD, Sorlie PD, NJ J. 1999. Quality of death rates by race and Hispanic origin: A summary of current research, 1999. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2(128). 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenker MB, Castañeda X, Rodriguez-Lainz A. 2014. Migration and Health: A Research Methods Handbook: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, Siahpush M. 2006. Widening socioeconomic inequalities in US life expectancy, 1980–2000. International Journal of Epidemiology 35(4): 969–979. 10.1093/ije/dyl083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, Siahpush M. 2014. Widening Rural - Urban Disparities in Life Expectancy, US., 1969–2009. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 46(2): e19–e29. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. 2016. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes, Available at http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.