Abstract

Nitrogen heterocycles are present in approximately 60% of drugs, with non-planar heterocycles incorporating stereogenic centers being of considerable interest to the fields of medicinal chemistry, chemical biology, and synthetic methods development. Over the past several years, our laboratory has developed synthetic strategies to access highly functionalized nitrogen heterocycles with multiple stereogenic centers. This approach centers on the efficient preparation of diverse 1,2-dihydropyridines by a Rh-catalyzed C−H bond alkenylation/electrocyclization cascade from readily available α,β-unsaturated imines and alkynes. The often densely substituted 1,2-dihydropyridine products have proven to be extremely versatile intermediates that can be elaborated with high regioselectivity and stereoselectivity, often without purification or even isolation. Protonation or alkylation followed by addition of hydride or carbon nucleophiles affords tetrahydropyridines with divergent regioselectivity and stereoselectivity depending on the reaction conditions. Mechanistic experiments in combination with DFT calculations provide a rationale for the high level of regiocontrol and stereocontrol that is observed. Further elaboration of the tetrahydropyridines by diastereoselective epoxidation and regioselective opening furnishes hydroxy-substituted piperidines. Alternatively, piperidines can be obtained directly from dihydropyridines by catalytic hydrogenation in good yield and with high face selectivity.

When trimethylsilyl alkynes or N-trimethylsilylmethyl imines are employed as starting inputs, the Rh-catalyzed C−H bond alkenylation/electrocyclization cascade provides silyl-substituted dihydropyridines that enable a host of new and useful transformations to different heterocycle classes. Protonation of these products under acidic conditions triggers the loss of the silyl group with formation of unstabilized azomethine ylides that would be difficult to access by other means. Depending on the location of the silyl group, [3+2] cycloaddition of the azomethine ylides with dipolarophiles provides tropane or indolizidine privileged frameworks, which for intramolecular cycloadditions yield complex polycyclic products with up to five contiguous stereogenic centers. By employing different types of conditions, loss of the silyl group can result in either rearrangement to cyclopropyl fused pyrrolidines or to aminocyclopentadienes. Mechanistic experiments supported by DFT calculations provide reaction pathways for these unusual rearrangements.

The transformations described in this Account are amenable to natural product synthesis and drug discovery applications due to the biological relevance of the structural motifs that are prepared, short reaction sequences that rely on readily available starting inputs, high regiocontrol and stereocontrol, and excellent functional group compatibility. For example, the methods have been applied to efficient asymmetric syntheses of morphinan drugs, including the opioid antagonist (−)-naltrexone, which is extensively used for the treatment of drug abuse.

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Nitrogen heterocycles are present in a majority of pharmaceutical agents, with those incorporating six-membered ring frameworks being by far the most prevalent.5 Additionally, drug discovery endeavors increasingly prioritize structures that allow for the three-dimensional display of functionality with the possible introduction of stereogenic centers at multiple sites.6,7 Therefore, methods for the rapid assembly of non-aromatic six-membered nitrogen heterocycle frameworks from simple starting materials and with the flexibility to introduce stereogenic centers at different sites are of high value to drug discovery and development.

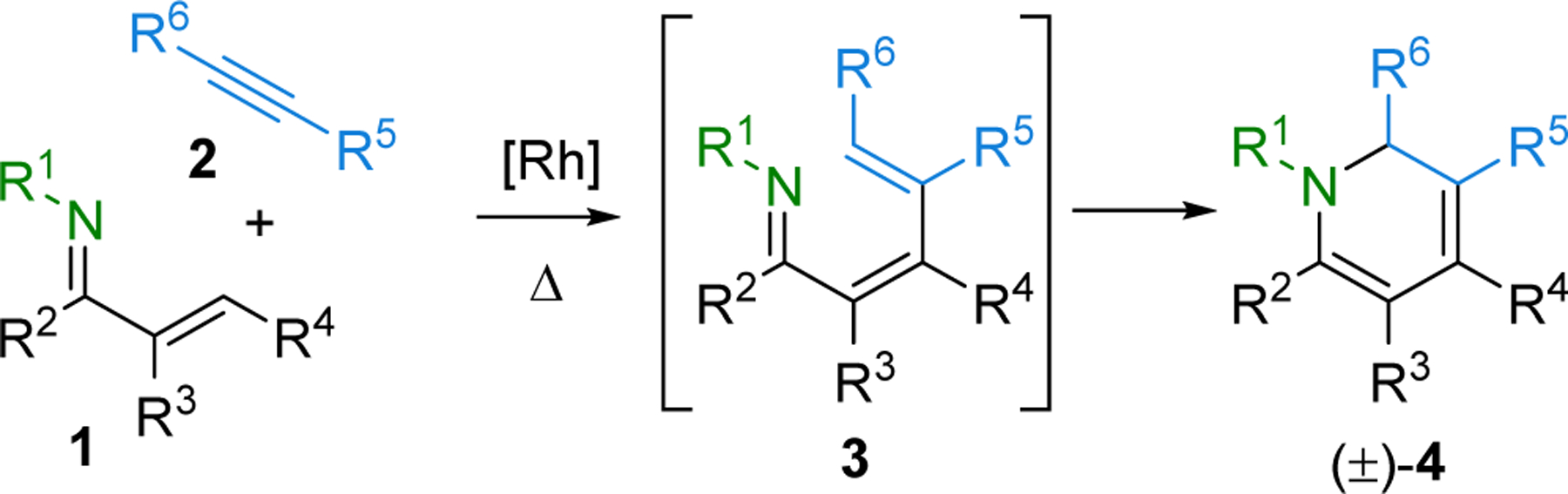

In 2008, we reported a Rh(I)-catalyzed C–H bond activation, alkenylation, and electrocyclization cascade to access 1,2-dihydropyridines 4 from α,β-unsaturated imines 1 and alkynes 2 (Scheme 1).8–13 The α,β-unsaturated imines are in turn readily obtained in one step from large numbers of commercially available primary amines or anilines and carbonyl compounds. Importantly, 1,2-dihydropyridines are extremely versatile intermediates for further elaboration to give different types of six-membered nitrogen heterocycle frameworks.14–16

Scheme 1.

One-Pot Rh(I)-Catalyzed C–H Activation/Alkenylation and 6π Electrocyclization Cascade.

As summarized in this Account, we have developed a large variety of new regioselective and stereoselective transformations to efficiently elaborate dihydropyridines 4 to provide different classes of nitrogen heterocycles that bear multiple stereogenic centers. Many of the heterocycle classes that we have prepared are frameworks that frequently occur in drugs and natural products, including six-membered tetrahydropyridines and piperidines as well as bicyclic isoquinuclidines, tropanes, and indolizidines.

2. DIASTEREOSELECTIVE SYNTHESIS OF HIGHLY SUBSTITUTED TETRAHYDROPYRIDINES

Tetrahydropyridines are present in a number of natural product-derived drugs such as the psychotropic agents LSD and ergotamine, anticancer agents vinblastine and vincristine, and dehydroemetine with antiprotozoal activity.17 Moreover, tetrahydropyridines are versatile intermediates for alkene addition reactions to provide piperidines, which are the most prevalent nitrogen heterocycles found in drugs (see sections 4 and 5).5

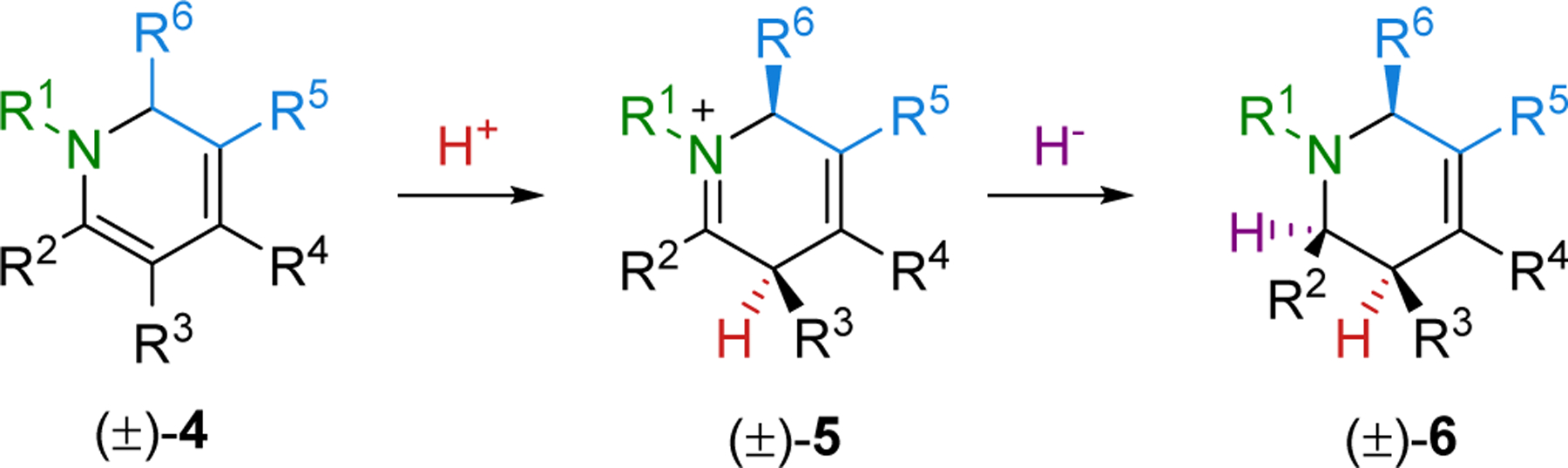

We disclosed the synthesis of tetrahydropyridine 6, which is prepared from dihydropyridine 4 by regio- and diastereoselective protonation followed by in situ diastereoselective reduction of the iminium intermediate 5 (Scheme 2).18 The acid and reducing agent were carefully selected after extensive optimization to achieve a high yield and stereoselectivity. Acetic acid was found to be an efficient Bronsted acid with stronger acids resulting in lower yields and stereoselectivities. For the hydride, the very mild reductant NaBH(OAc)3 was determined to be an optimal.19 Protonation occurs on the opposite face of the R6 substituent, which is disposed directly above the six-membered ring due to A(1,2) allylic strain between R6 and the R1 nitrogen substituent.1,20 When R5 is a carbon substituent, A(1,2) allylic strain with the R6 substituent further reinforces this conformation. Similarly, the face selectivity for hydride addition was also found to be controlled by steric hindrance as supported by computational studies carried out in collaboration with the Houk lab.21

Scheme 2.

Regio- and Diastereoselective Protonation and Reduction of 4.

In practice, dihydropyridines 4 are reduced without workup or isolation to enable the efficient one-pot preparation of tetrahydropyridines 6 from imines 1 and alkynes 2 (Table 1).18 Both the precatalyst [RhCl(coe)2]2 and optimal ligand 4-Me2NPhPEt2 are commercially available, which adds to the utility of this one-pot sequence. Exploration of the reaction scope revealed that the products were formed in high yields and diastereoselectivities from a wide variety of imines and alkynes (Table 1). Depending on the imine substitution pattern, products with one (6a), two (6b) or three (6c–6e) stereogenic centers can be produced. Although N-benzyl imines are shown for most of the examples in Table 1, N-aryl imines (6d) and alkyl imines (not shown) are also successful inputs with many additional examples provided throughout this Account. Tolanes, such as parent diphenylacetylene (6e), were effective alkyne substrates and afforded products in excellent yield and stereoselectivity. Bicyclic compounds (6f–6g) and derivatives incorporating heterocycles such as furans (6g) and indoles (6h) could also be prepared in high yields and stereoselectivity.

Table 1.

One-Pot Synthesis of 6by a Rh(I)-Catalyzed C–H Alkenylation–Electrocyclization–Reduction Cascade.

|

0.25 mol % of [RhCl(coe)2]2 on >100 mmol scale.

0.25 mol % of [RhCl(coe)2]2 on >5 mmol scale.

The preparative scale syntheses of 6c and 6g are especially noteworthy. At a loading of only 0.25 mol% of precatalyst and on a >100 mmol scale and >5 mmol scale, respectively, for 6c and 6g, comparable yields and diastereoselectivities were observed relative to the reactions performed with higher catalyst loadings on smaller scale.22

Carbon nucleophiles add stereoselectively in place of the hydride to enable a higher degree of substitution at the α position in tetrahydropyridine 7 (Table 2).1 Because organometallic reagents are incompatible with the acid required for protonation of 4, a stepwise protonation and nucleophilic addition process was implemented. Irreversible protonation was achieved with the strong acid PhSO3H to give iminium 5, to which a variety of organometallic reagents R-[M] were added in excellent overall yields and stereoselectivities, as exemplified for allyl (7a) and benzyl (7b) cerium reagents,23 alkynyl Grignard reagents (7c, 7d), and Reformatsky enolates (7e).24 The facial selectivity for the carbon nucleophile addition step was determined to be the same as that for hydride reduction, suggesting that the addition is primarily dictated by the iminium ion geometry 5 rather than the type of the nucleophile.

Table 2.

Addition of Carbon Nucleophiles to Give 7.

|

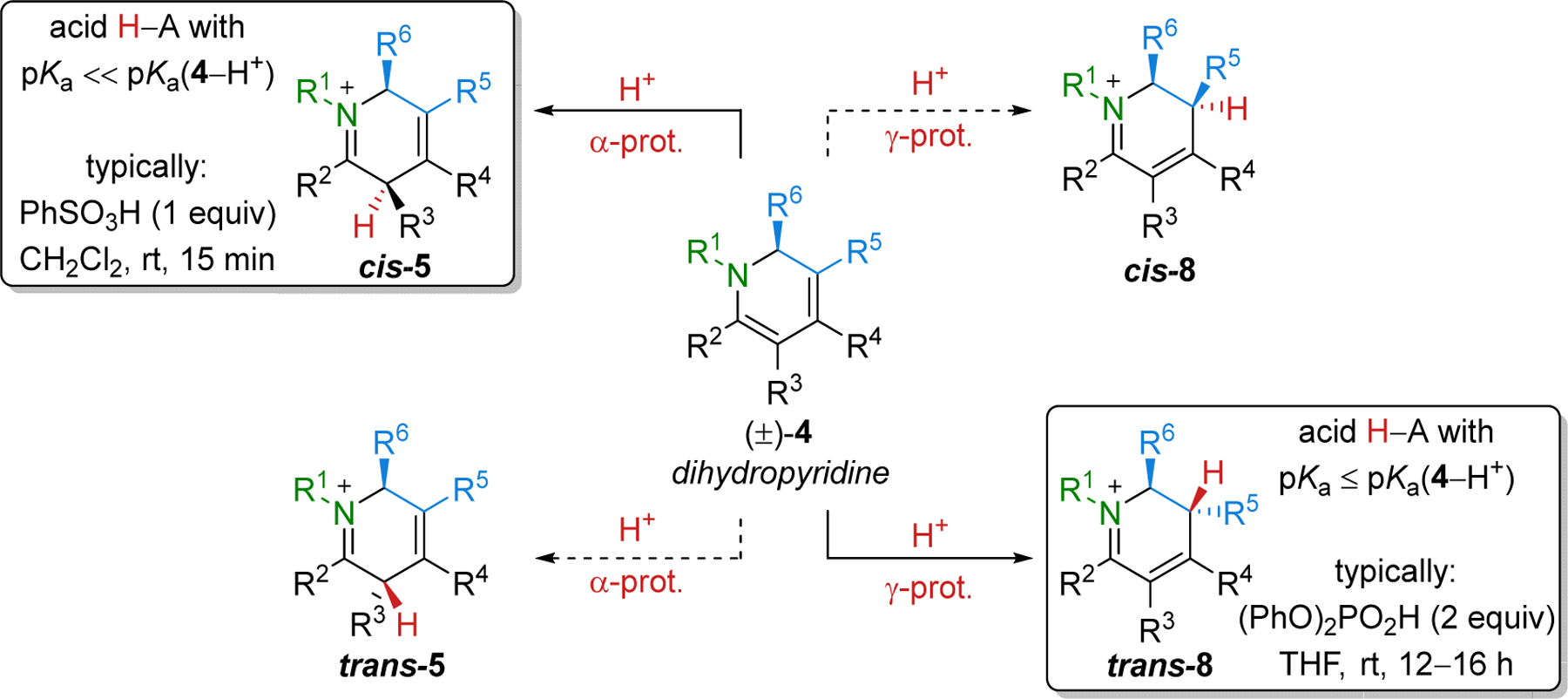

In the previous examples, kinetic protonation at the α position to give cis-5 (Scheme 3) is achieved either with a mild acid like AcOH with in situ reduction to prevent equilibration (see Table 1) or by irreversible protonation with the strong acid PhSO3H (see Table 2). However, protonation of dihydropyridine 4 can theoretically provide four possible iminiums, namely cis and trans stereoisomers of reactive iminium ions 5 and 8, obtained by protonation at the α and γ positions, respectively (Scheme 3). To that end, we found that protonation with acids strong enough to favor iminium formation but that still allow equilibration, such as (PhO)2PO2H, give the most stable iminium trans-8. Indeed, trans-8 obtained from 4a (R1 = Bn; R2, R3, R4 = Me; and R5, R6 = Et) was determined to be >3 kcal/mol more stable than the other three iminium isomers by density functional theory (DFT) calculations.1 Significantly, X-ray structures of iminiums cis-5 and trans-8 matched well with the calculated low energy structures for these isomers to provide support for the calculations.

Scheme 3.

Four Possible Iminium Ions Resulting from Protonation of 4.

Upon formation of the thermodynamic iminium 8, reduction can generally be accomplished without isolation of the iminium intermediate to provide tetrahydropyridines 9 in high yields and diastereoselectivities (>95:5) (Table 3). As illustrated by the representative examples, benzyl (9a), aryl (9b) and alkyl (9c) nitrogen substituents, unsymmetrical alkyne inputs (9d and 9e), and bicyclic products (9f) are all compatible with this one-pot sequence. It is notable that tetrahydropyridine 9 provides a differential spatial display of substituents relative to previously described tetrahydropyridine 6 (Table 1). In collaboration with the Houk lab, the π-facial preference of the hydride attack to give 9 was found to be controlled by torsional steering25 with the favored attack leading to a lower-energy “half-chair”-like conformation of 9 with attack at the other π-face resulting in an unfavorable “twist-boat” conformation.21

Table 3.

One-Pot Synthesis of 9.

|

Dihydropyridine isolated by filtration through alumina prior to the protonation/reduction steps.

Iminium 8, obtained by thermodynamic protonation of dihydropyridine 4, also reacted with carbon nucleophiles to give tetrahydropyridine 10 (Table 4).1 After protonation with (PhO)2PO2H, alkynyl Grignard reagents (10a), benzyl and allyl cerium reagents (10b) and Reformatsky enolates (10c) all added in high overall yields and selectivities (Table 4). The facial selectivity of carbon nucleophile additions was the same as previously observed for hydride addition as confirmed by X-ray structural analysis.

Table 4.

Diastereoselective Protonation and Carbon Nucleophile Addition to Give 10.

|

In all of the previously described approaches for tetrahydropyridine synthesis, the iminium intermediates 5 and 8 were generated by protonation of 4. We postulated that the use of electrophilic alkylating agents in place of a proton source would provide iminiums 11 that upon reduction or carbon nucleophile addition would introduce quaternary carbon centers (Table 5).26 When investigating the feasibility of an alkylation-reduction sequence to afford 12 (Table 5a), we found that alkyl triflates were generally the most effective carbon electrophiles and Me4NBH(OAc)3 was typically used as a convenient hydride source. A variety of substitution patterns around the dihydropyridine core was tolerated , as exemplified by the installation of methyl (12a and 12d), ethyl (12b), and methoxyethyl (12c) substituents. The iminium ion 11 generated upon alkylation can also be reacted with a carbon nucleophile to generate 13 (Table 5b). As exemplified by 13b to 13d, contiguous tetrasubstituted carbons can be introduced with high selectivity, with the relative stereochemistry for many of the products rigorously determined by X-ray crystallography.26 It is noteworthy that this family of piperidine derivatives has unprecedented levels of substitution that would be difficult to access by other means.

Table 5.

One-Pot Alkylation and Reduction or Carbon Nucleophile Addition.

|

K(iPrO)3BH, THF, −78 °C to rt.

Isoquinuclidines are pharmaceutically relevant bridged bicyclic heterocycles that are present in a variety of bioactive natural products exemplified by the ibogamine alkaloids.27 Dihydropyridine 4, which incorporates alkyl and aryl nitrogen substituents, represents an exceptionally reactive diene for the efficient synthesis of isoquinuclidines (Table 6).28 A wide range of dienophiles, including methyl acrylate (14a and 14e–g), acrylonitrile (14b), N-phenyl maleimide (14c and 14d) added with high face and endo selectivity. Benzyl (14a–b and 14e–g), aryl (14c) and alkyl (14d) nitrogen substituents on the dihydropyridine all proved to be effective dienes for Diels–Alder cycloaddition. Moreover, a variety of different substituents can be displayed at R2 to R6, as exemplified by isoquinuclidine products 14e to 14g.

Table 6.

Synthesis of Isoquinuclidines from Dihydropyridines via the Diels–Alder Reaction.

|

Neat, 105 °C.

N-Phenyl maleimide (1.05 equiv), 0.1 M CH2Cl2, rt.

3. SYNTHESIS OF SILYL SUBSTITUTED DIHYDROPYRIDINES AND THEIR TRANSFORMATIONS

Rh(I)-catalyzed C–H bond alkenylation and electrocyclization cascades with trimethylsilyl (TMS) alkynes 15 to form 6-trimethylsilyl-substituted dihydropyridines 16 created the opportunity to overcome a limitation in our synthesis of dihydropyridines (Table 7). In the previously described studies, only internal alkynes were employed as inputs due to competitive Rh(I)-catalyzed homocoupling for terminal alkynes (see section 2).11,29 However, without purification or isolation of the trimethylsilyl-substituted 16, treatment with acid and a mild reducing agent provides tetrahydropyridine 17 as a single diastereomer and regioisomer with hydrogen replacing the silicon substituent (Table 7).30 A variety of acids and hydride sources were tested, revealing that Me4NBH(OAc)3 and (PhO)2PO2H is generally the optimal pair for this transformation. A broad scope of TMS acetylenes 15 and imines 1 was demonstrated, of which a representative set is illustrated in Table 7. Aromatic (17a and 17c–d) and heteroaromatic (17b) groups on the alkyne were obtained in high overall yields from imines 1 along with high diastereoselectivities. The indole silyl alkyne was also shown to provide a comparable yield of 17b when the reaction was performed on a gram scale at a [RhCl(coe)2]2 precatalyst loading of 0.50 mol %.22 In addition to the N-benzyl group used in most examples, N-cyclopropylmethyl (17c) and N-cyclohexyl (17d) were suitable nitrogen substituents. A variety of functionality was incorporated in the TMS alkyne input as exemplified by a Boc protected amine (17e). Dihydropyridines with R2 = H derived from aldimine precursors required slightly altered conditions due to incomplete desilylation under the standard reaction conditions. In these instances, the reaction was carried out in THF with HF-pyridine in place of diphenyl phosphoric acid, as exemplified for 17f, which was isolated in 70% overall yield.

Table 7.

Convergent Assembly of 17with TMS Alkyne as a Terminal Alkyne Equivalent.

|

0.5 mol % of [RhCl(coe)2]2 on > 5 mmol scale.

Reduction performed with Me4NBH(OAc)3 and HF-pyr in THF at 0 to 23 °C.

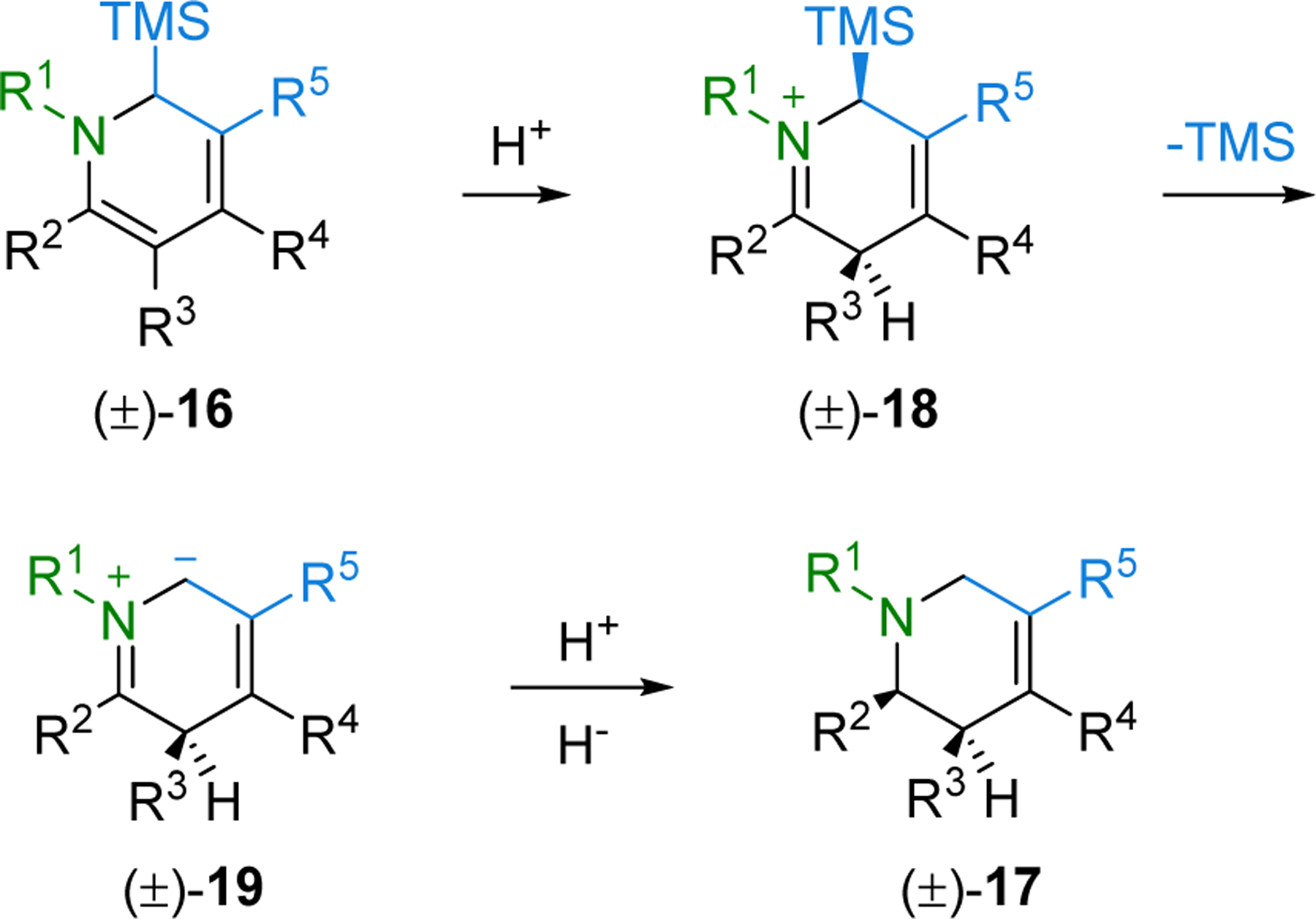

Examination of the reaction mechanism established that upon protonation of 16, iminium 18 undergoes desilylation to form the unstabilized azomethine ylide 19, which upon protonation and reduction gives product 17 (Scheme 4).30,31 The discovery that the highly substituted unstabilized ylide 19 was the reactive intermediate presented an exciting opportunity to explore new transformations to useful amine products with substitution patterns that would be difficult to introduce by alternative methods.

Scheme 4.

Proposed Mechanistic Pathway.

Tropanes are bridged bicyclic nitrogen heterocycles that are found in well-known bioactive natural products like cocaine, and more importantly, in many drugs such as maraviroc used to treat HIV, atropine for heart problems, and spiriva for asthma and COPD.32 We envisioned that tropane derivatives with unexplored substitution patterns could be prepared by [3+2] cycloaddition between the endocyclic unstabilized azomethine ylide 19 (Scheme 4) and dipolarophiles.33–35 Direct treatment of 16, without isolation, with diphenyl phosphoric acid and dimethylacetylene dicarboxylate (DMAD) produced tropane 20a in high overall yield from imine 1 and with 15:1 diastereoselectivity (Table 8).30 X-ray crystallographic analysis of 20a established the relative stereochemistry. The preparation of tropanes from 16 with different substitution patterns are exemplified by tropanes 20a and 20b. Additionally, tropane 20c illustrates that unsymmetrical alkyne dipolarophiles also provide the tropane products in good overall yields and stereoselectivity and with moderate regioselectivity.

Table 8.

Tropane Synthesis via [3+2] Cycloaddition of Endocyclic Azomethine Ylides with Alkyne Dipolarophiles.

|

Performed at −78 °C in toluene.

While the aforementioned tropane synthesis relies on formation of an endocyclic azomethine ylide, we also established that this protonation/desilylation strategy is applicable to exocyclic ylide generation allowing for entry into the indolizidine framework.36,37 In this case, the N-trimethylsilylmethyl dihydropyridine 21 was prepared via the Rh(I)-catalyzed C–H activation/alkenylation/electrocyclization cascade using internal alkynes and imines derived from (trimethylsilyl)methylamine (Table 9).2 Under acidic conditions and without isolation, 21 undergoes protonation with desilylation to generate ylide 22, which then further reacted with alkyne dipolarophiles to yield indolizidines 23. Internal alkyne dipolarophiles gave the desired products exemplified by 23a–b in moderate to high yields and as single regio- and stereoisomers. Modest selectivity was also achieved when employing terminal alkyne dipolarophiles bearing ester (not shown) or amide groups (23c).

Table 9.

Indolizidines Synthesis via [3+2] Cycloaddition of Exocyclic Azomethine Ylides with Alkyne Dipolarophiles.

|

Having previously shown that dihydropyridines can be alkylated to form iminium intermediates that upon reduction provide tetrahydropyridines (see section 2), we sought to use electrophilic alkylating agents with 16 to trigger the formation of azomethine ylide intermediate 24, thereby enabling the preparation of tropanes 25 that incorporate quaternary carbon centers (Table 10).2 We found that iminium formation occurred with alkyl triflates in place of diphenyl phosphate, and that the addition of Bu4NOAc effectively facilitated desilylation to generate the unstabilized ylide. Under these conditions, tropanes 25 were synthesized in good yield by trapping the resulting ylide with a dipolarophile. Use of EtOTf as the alkylating agent resulted in contiguous tetrasubstituted carbons with excellent diastereoselectivity as exemplified by 25a. Characterization by X-ray crystallography of a closely related product to 25a (not shown) established that the dipolarophile adds to the opposite face of the bulkier ethyl substituent at the 3-position. In addition to alkynes, cyclic and acyclic alkene dipolarophiles also underwent cycloaddition with good diastereoselectivity, with the N-phenylmaleimide-derived tropane 25b providing a representative example. Bridged tricyclic tropanes 27 were also accessible by employing an alkylating agent tethered to a dipolarophile. For this intramolecular variant, no external desilylation agent was required. Tropane 27a, which contains five contiguous stereocenters and was formed as a single diastereoisomer, exemplifies the types of polycyclic frameworks obtainable by this method.

Table 10.

Regio- and Stereoselective Cascades via Cycloadditions with Unstabilized Azomethine Ylides.

|

EtOTf, rt then dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate, Bu4NOAc, 0 °C to rt.

MeOTf, CH2Cl2, rt then 1-phenyl-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione, Bu4NOAc, CH2Cl2 0 °C to rt.

Methyl (E)-7-(((trifluoromethyl) sulfonyl)oxy)hept-2-enoate, rt.

MeOTf, CH2Cl2, rt then 3-oxetanone or 1-Boc-3-azetidinone, Bu4NOAc, CH2Cl2, 0 °C to rt.

Methyl (E)-7-(((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)oxy)hept-2-enoate, CH2Cl2, Cs2CO3, 0 °C to rt.

This alkylation-cycloaddition cascade was next examined for exocyclic azomethine ylides. Dihydropyridine 21 efficiently reacted with alkylating agents to form an iminium intermediate, which upon protonation and desilylation produces unstabilized ylide 28 (Table 10). While cycloadditions with alkene and alkyne dipolarophiles resulted in mixtures of product isomers, symmetrical activated ketone dipolarophiles yielded fused bicyclic oxazolidines 29 with high regio- and diastereoselectivities. For instance, product 29a was prepared in moderate yield and a 93:7 isomer ratio following cycloaddition with 3-oxetanone, and oxazolidine 29b, derived from 1-Boc-3-azetidinone, formed in slightly higher yield and with excellent selectivity. Polycyclic indolizidines, such as 31a, were also obtained by intramolecular cycloaddition of ylide 30 with tethered dipolarophiles.

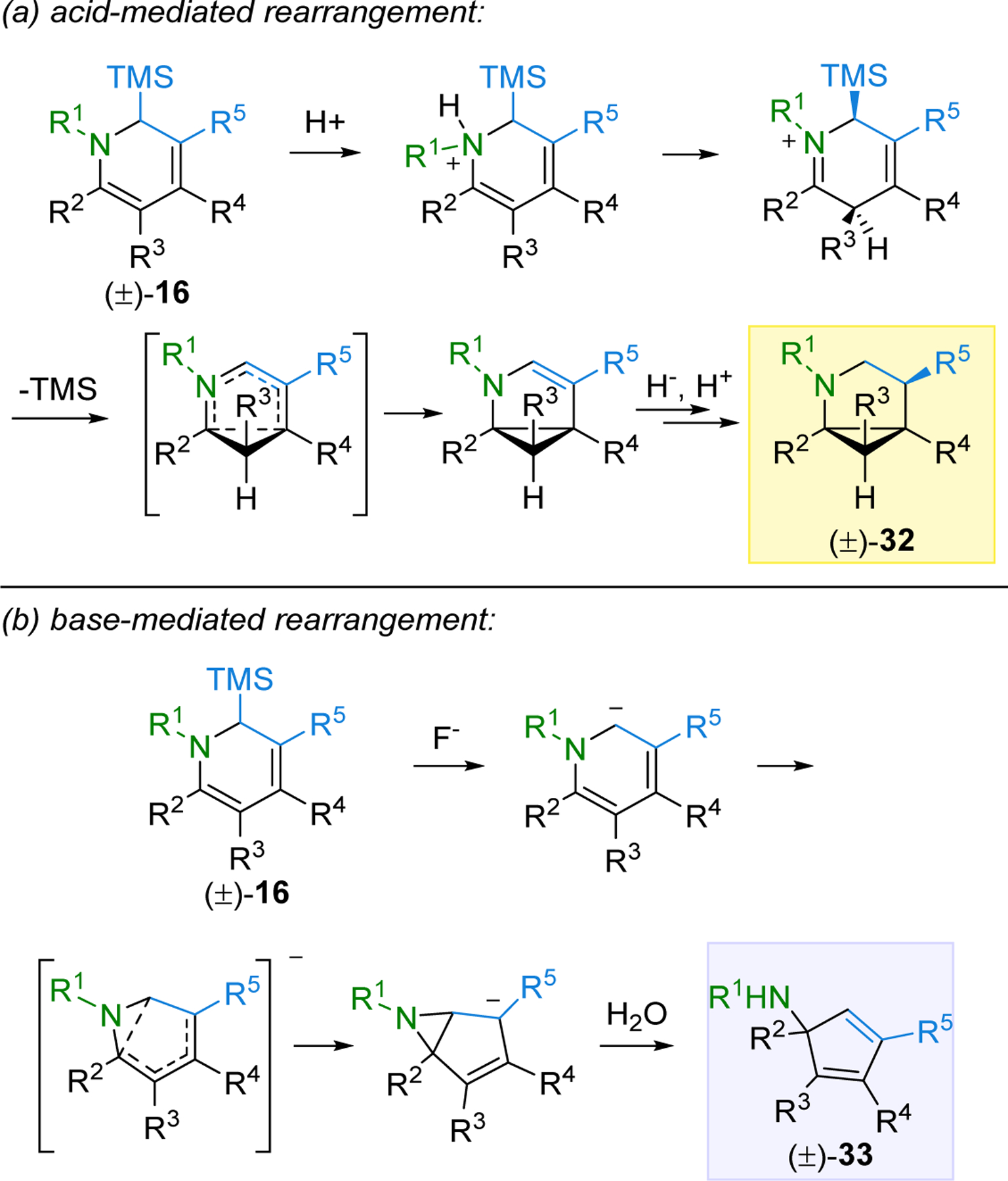

Further studies with 16 revealed that desilylative rearrangements are also possible, leading to either cyclopropyl-fused pyrrolidines or aminocyclopentadienes depending on the conditions employed (Table 11). We found that when select derivatives of 16 were treated with PhSO3H and Me4NBH(OAc)3 at −78 °C and then slowly warmed to room temperature, cyclopropyl-fused pyrrolidines 32a and 32b could be obtained.30 An X-ray crystal structure of the amine salt of 32a rigorously confirmed this structural assignment. In contrast, under basic conditions using Bu4NF hydrate, appropriately substituted derivatives of 16 rearranged to aminocyclopentadienes 33, with this skeletal rearrangement also verified by X-ray structural analysis.38 Benzyl (33a), alkyl (33b–c), and aryl (not shown) N-substituents were all successful in this transformation, and high yields were observed when an ester group was present at the R5-position (33d–33f). The versatility of the aminocyclopentadiene products 33 for further elaboration was demonstrated by the chemoselective functionalization of the amine, ester, or one or both alkenes in 33f (not shown).38

Table 11.

Acid- or Base-Mediated Rearrangement of 16.

|

Possible mechanisms for these acid- and base-mediated rearrangements are depicted in Scheme 5. In the presence of acid, 16 was observed to undergo kinetic protonation on nitrogen.30 Upon warming, tautomerization to the C-protonated ketiminium triggers desilylation and disrotatory 6π electrocyclization to an enamide, that upon protonation and reduction provides pyrrolidine 32 (Scheme 5a). When a suitably substituted derivative of 16 is instead treated with the base Bu4NF, desilylation generates an anionic species that undergoes a different disrotatory 6π electrocyclization, this time producing an aziridine intermediate (Scheme 5b).38 Experimental support for this anionic mechanism was provided by the requirement of an electron-withdrawing R5 substituent that could stabilize the negative charge after the ring contraction. DFT calculations provided support for the proposed mechanism and also indicated that the free energies of activation for the electrocyclization transition state were much lower with electron-withdrawing R5 substituents than when a methyl group was placed in this position. Experimentally, no cyclopentadiene product was observed when an R5 methyl group was tested. In the last step of this mechanism, the aziridine intermediate, in the presence of water as a proton source, regioselectively opens to generate product 33.

Scheme 5.

Proposed Mechanisms for the Divergent Rearrangements of 16.

4. SYNTHESIS OF PIPERIDINES

Piperidines occur more frequently in drugs than any other class of heterocycles, and for this reason, efficient methods for their preparation and elaboration are important for drug discovery and development.5 Dihydropyridines and tetrahydropyridines are useful synthons that can be transformed into various piperidines by further functionalization of the alkene bonds. For example, piperidines with varying substitutions were prepared by palladium-catalyzed hydrogenation of dihydropyridines to form the all-syn stereoisomer with high diastereoselectivities and excellent overall yields for the two-step process (Table 12).3 This transformation was feasible for a wide range of substrates such as those with linear (34a) or branched alkyl groups (34b–34f), including saturated heterocyclic (34c) substituents at R6, as well as for a variety of substituted aryl groups on the piperidine nitrogen (34e–34f).

Table 12.

Synthesis and Hydrogenation of Dihydropyridines to Give Piperidines 34.

|

The piperidines prepared in Table 12, which incorporate several stereogenic centers, enabled the exploration of photoredox catalysis for carrying out a diastereoselective transformation. Notably, at the time this work was performed, only a few examples of diastereoselective photoredox-mediated reactions had previously appeared.39,40 Efficient coupling of piperidines 34 with cyanoarenes 35 gave the arylated products 37 with high diastereoselectivities (Table 13).3,41 The diastereomers that formed were unambiguously confirmed by X-ray crystallography. Moreover, regardless of the substitution pattern of the starting piperidine 34, the major product 37 always corresponded to the most stable diastereomer as determined by DFT calculations. Mechanistic studies in collaboration with the Mayer lab, which included optical and fluorescent spectroscopic methods as well as reaction kinetics, revealed that although initial C–H arylation proceeds rapidly and without selectivity to give a mixture of diastereomers 36, a slower epimerization then occurs to provide the more stable stereoisomer 37.3

Table 13.

Diastereoselective Functionalization of Highly Substituted Piperidines by Photoredox-Catalyzed α-Amino C–H Arylation and Epimerization.

|

[Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2]PF6 instead of Ir(ppy)3.

Piperidines can also be prepared by additions to the alkene functionality in tetrahydropyridines. For example, stereoselective epoxidation followed by nucleophilic addition provides a general approach for the preparation of piperidinols (Table 14–15).42 Tetrahydropyridine 9 and 6, respectively obtained by thermodynamic and kinetic protonation and reduction of dihydropyridines 4, underwent highly diastereoselective epoxidation with peracid in the presence of an acid source to protect the basic piperidine amine from N-oxidation.

Table 14.

Face Selective Epoxidation of Tetrahydropyridines 9 and 6.

|

(CF3CO)2O (6.0 equiv) and H2O2 (30% w/w in H2O, 5.0 equiv) premixed in THF at 0 °C.

Table 15.

Regioselective Ring-Opening of Epoxides via Nucleophilic Additions.

|

H2O addition was achieved by heating at 70 °C in a CH2Cl2/sat. aq NaHSO4 mixture.

MeOH addition was performed at 80 °C in anhydrous MeOH with dry PhSO3H (2 equiv).

HF addition was accomplished by treating with HBF4 Et2O (2 equiv) at rt.

Tetrahydropyridine 9 furnished the epoxide in a high yield and diastereoselectivity when treated with m-chloroperbenzoic acid and trichloroacetic acid, where the relative configuration of the epoxidized product was rigorously determined by X-ray crystallography (Table 14a). The high level of stereoselectivity is predicted to arise from the face-selective H-bonding of the peroxy acid group oxygen with the ammonium proton. This protocol was successful for a variety of derivatives of 9, including those with different degrees of substitution on the ring (38a–b) and with varying nitrogen substituents (38d–e). For derivatives of 9 with sterically demanding substituents, an alternative method of premixing trifluoroacetic anhydride and H2O2 was chosen to provide a reactive peroxidation reagent in situ (38c).

The isomeric tetrahydropyridine 6 with R2, R3, and R6 groups all positioned on the same face required an alternative strategy to achieve a highly diastereoselective epoxidation, as the preexisting conditions optimized for 9 resulted in a slower reaction and a lower diastereoselectivity. Therefore, a new reagent was designed to control the face-selective epoxidation. Reaction of an electron-deficient cyclic anhydride with H2O2 generates a percarboxy acid with a pendant carboxylic acid capable of hydrogen bonding with the piperidine amine (Table 14b). This bifunctional epoxidation reagent, which is prepared in situ, provided highly diastereoselective epoxidation of 6 with varying degrees of substitution around the ring (39a–b), unbranched and branched alkyl groups on the nitrogen (39c), and even for a sterically hindered bicyclic system (39d).

Epoxides 38 and 39 were each shown to be viable substrates for the preparation of piperidinols (Table 15). Acidic conditions were employed to protonate the piperidine nitrogen as well as to activate the epoxide for ring-opening, which enabled nucleophilic additions with water (40a and 41a), methanol (40b), and fluoride (41b). The piperidinols were obtained in high yields by regioselective nucleophilic attack at the site distal to the protonated piperidine nitrogen. This approach provides an efficient entry to piperidinols bearing adjacent tetrasubstituted carbons with a wide range of substitution patterns on the ring.

5. ASYMMETRIC SYNTHESIS OF (+)-KETORPHANOL AND (−)-NALTREXONE

Opioid ligands containing the morphinan core are among the most well-known alkaloid natural products and represent some of the most important drugs for managing pain, albeit also causing serious societal problems as drugs of abuse.43 Semi-synthetic opioids are primarily produced from naturally occurring morphine or thebaine, which due to their highly elaborated structures, limit the types of modifications that are possible. Using readily available inputs, we envisioned that an intramolecular C–H activation, alkenylation, electrocyclization and reduction sequence could provide rapid access to fused bicyclic cores that in just a few additional steps could be taken on to diverse morphinan products. To demonstrate this approach, we reported total syntheses of the enantiomer of the semisynthetic opioid agonist (+)-ketorphanol44,45 and the more complex opioid antagonist (−)-naltrexone,4,46 which is widely used to treat opioid addiction.

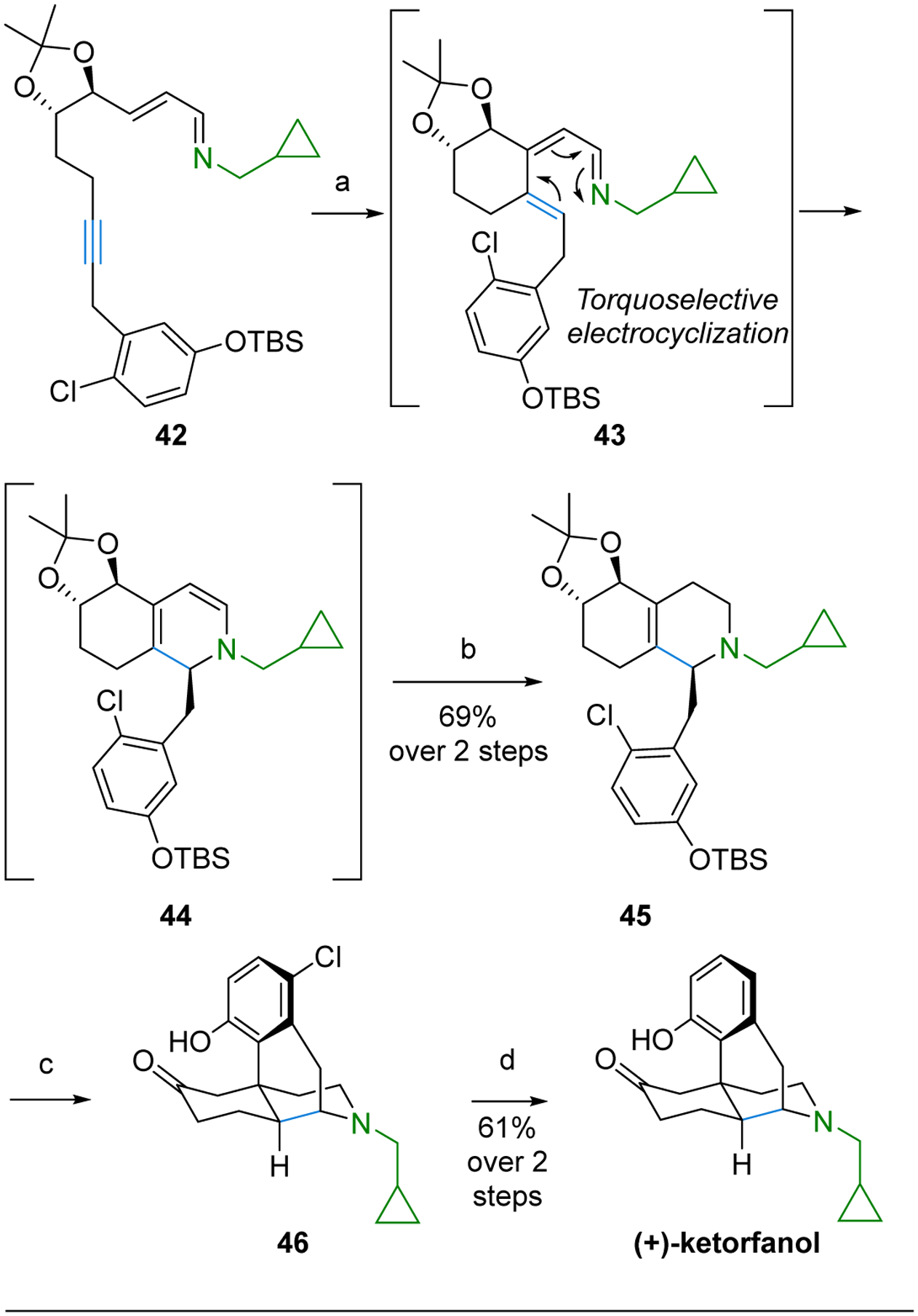

Rh(I)-catalyzed C–H activation and alkenylation of imine 42 afforded the azatriene 43, which undergoes in situ, torquoselective 6π electrocyclization to give a single diastereomer of the hexahydroisoquinoline 44 as determined by 1H NMR analysis (Scheme 6).44 Treatment with NaBH(OAc)3 and AcOH without workup or isolation then provides the bicyclic, fused compound 45 in 69% overall yield. This one-pot sequence results in the formation of two new rings, introduces a key stereogenic center, and correctly places the double bond at the ring fusion site for subsequent transformations.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of (+)-Ketorphanol from the Rh(I) Cascade Starting from Imine and Tethered Alkyne.

(a) [RhCl(coe)2]2 (5 mol %), 4-(diethylphosphino)-N,N-dimethylaniline (10 mol %), toluene, 55 °C; (b) NaHB(OAc)3, AcOH, EtOH, 0 to 23 °C; (c) 85% H3PO4, 125 °C; (d) H2, Pd/C, NaHCO3, EtOH, 23 °C.

The torquoselective electrocyclization of 43 is of particular interest because it represents one of the few examples of controlling azatriene electrocyclization stereoselectivity with remote stereogenic centers.47 The Houk lab performed DFT calculations to establish that the chiral acetonide enforces transition-state conformational preferences of the six-membered ring appended to the azatriene to result in a 3.2 kcal/mol lower energy for the electrocyclization to give the desired stereoisomer.

Treatment of 45 with H3PO4 afforded the morphinan core 46 in a single step that proceeded by removal of the protecting groups, redox-neutral transformation of the diol into the ketone, and intramolecular Friedel-Craft cyclization. Reductive dehalogenation of the chloride initially installed to enable regiospecific Friedel-Craft cyclization then gave (+)-ketorphanol.

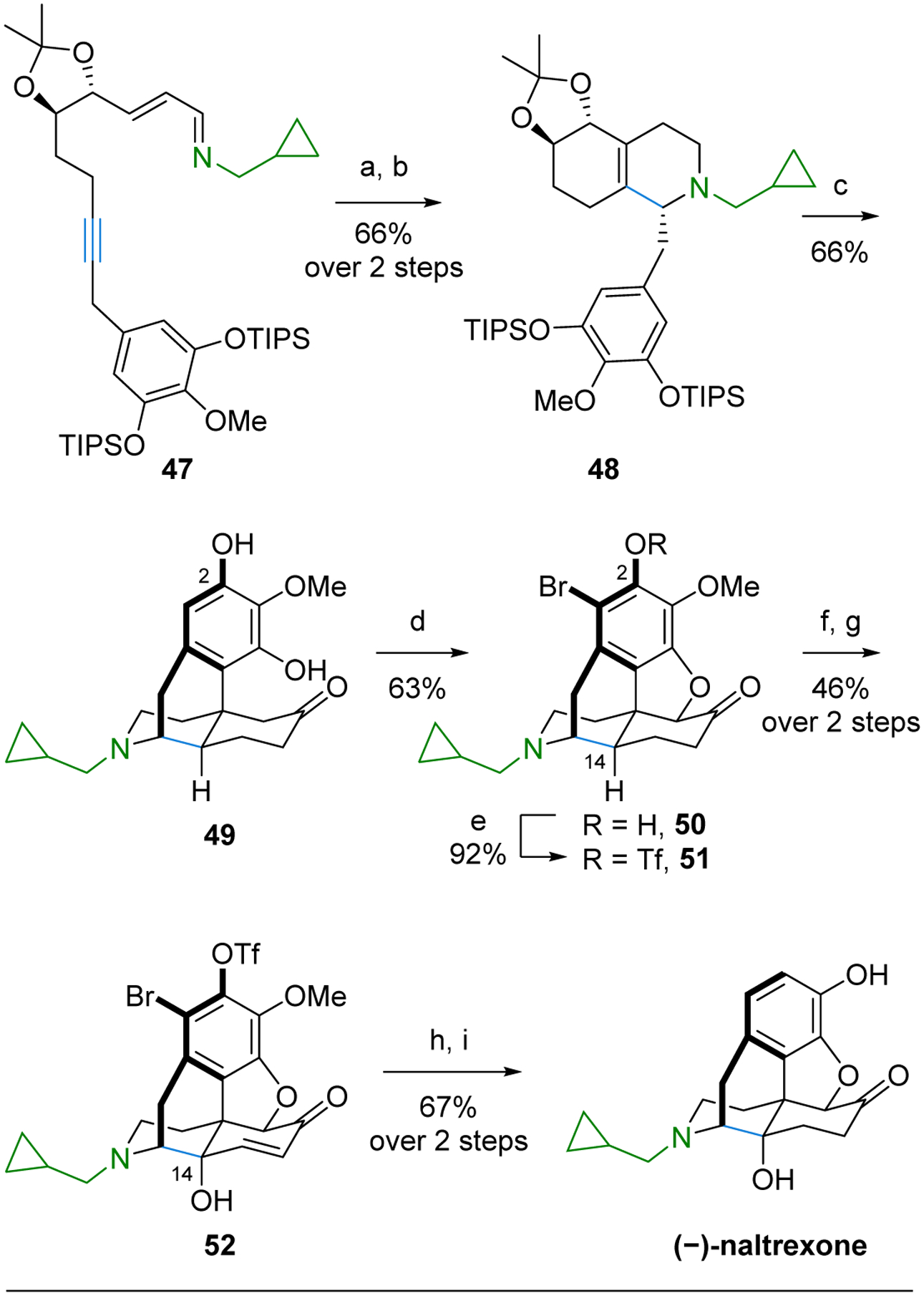

The feasibility of accessing the morphinan core by a torquoselective Rh(I)-catalyzed C–H alkenylation/electrocyclization cascade paved the way for our efficient preparation of the more complex opioid antagonist (−)-naltrexone (Scheme 7). This antagonist has seen extensive use for the treatment of drug abuse but has previously only been prepared from other natural products such as (–)-thebaine, which is isolated in small quantities from opium (0.3–1.5%).4

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of (−)-Naltrexone.

(a) [RhCl(coe)2]2 (5 mol %), (pNMe2)PhPEt2 (10 mol %), PhMe, 85 °C; (b) NaBH(OAc)3 (5.0 equiv), AcOH, EtOH, 0 °C; (c) 55% H3PO4, 125 °C; (d) Br2, AcOH, 23 °C; NaOH (aq), 23 °C; (e) Tf2O, pyridine, 0 °C; (f) Pd(TFA)2 (1.4 equiv), TFA, DMSO, 80 °C; (g) CuSO4 (2 mol %), ketoglutaric acid, pyridine, 23 °C, O2; (h) Et3N, Pd(OH)2 (20 wt%), 1:3 EtOAc/MeOH, H2, 23 °C; (i) BBr3, CH2Cl2, −40 to 0 °C.

Submitting imine tethered alkyne 47 with the (R,R)-acetonide to the Rh(I)-catalyzed C–H alkenylation/electrocyclization cascade followed by protonation and reduction sequence provided octahydroquinoline 48 as a single diastereomer (Scheme 7). Subsequent treatment with acid then gave 49 containing the morphinan core through an analogous series of transformations to that described for (+)-ketorphanol.

Formation of dihydrofuran 50 was accomplished by α–bromination of ketone 49 with concomitant bromination of the aromatic ring and nucleophilic displacement by the adjacent phenol. The remaining C-2 hydroxyl in 50, installed to avoid regioselectivity issues in the acid-catalyzed cyclization step, was converted to the triflate 51 to allow for its reductive removal along with the bromide in a later step. Installation of the C-14 hydroxyl, which is essential to the bioactivity of (−)-naltrexone, was next accomplished by sequential C–H oxidation reactions. First, C–H dehydrogenation of 51 gave an enone48 that activated the ɣ C-14 site for C–H hydroxylation by Cu(II)-catalyzed oxidation with O2 to provide 52. Hydrogenolytic removal of the bromide and triflate with reduction of the enone in a single step followed by demethylation then afforded (−)-naltrexone, which represents the first synthesis of this drug that does not proceed through thebaine.

6. CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOK

As described in this Account, the rapid and efficient preparation of 1,2-dihydropyridines with different substitution patterns and diverse display of functionality is achieved by a Rh(I)-catalyzed C–H bond alkenylation and electrocyclization cascade using readily accessible α,β-unsaturated imines and alkynes. Dihydropyridines prepared by this approach have proven to be exceedingly versatile intermediates for regioselective and stereoselective elaborations. In just one or two steps, we have demonstrated that they can be transformed to a variety of different nitrogen heterocycle frameworks displaying multiple stereogenic centers, including piperidines and tetrahydropyridines, bicyclic isoquinuclidines, tropanes and indolizidines, and even more complex polycyclic structures. Mechanistic studies often supported by DFT calculations provide an understanding of the sometimes surprising reaction pathways of these new transformations, including a rationale for the typically high observed regioselectivity and stereoselectivity.

The ability to easily introduce different types of substituents on 1,2-dihydropyridines created the opportunity to uncover previously unexplored reactivity along with the development of useful new synthetic transformations. This is exemplified by silyl-substituted dihydropyridines, which upon protonation and loss of the silyl group, provide unstabilized ylides capable of undergoing a range of different transformations, including [3+2] cycloadditions to tropanes, indolizidines and other heterocycles as well an unusual rearrangement to cyclopropylpyrrolidines. On the other hand, treatment of silyl-substituted dihydropyridines with tetrabutylammonium fluoride triggers a very different rearrangement to give aminocyclopentadienes. We look forward to the discovery of additional chemical transformations by further exploration of the reactivity of these versatile heterocycles.

As demonstrated by the efficient syntheses of the morphinan drugs (+)-ketorphanol and (−)-naltrexone, the chemistry described in this Account is directly applicable to the multistep syntheses of important classes of bioactive natural products and their derivatives. Given that the reported chemistry relies on readily accessible inputs, short reaction sequences, and provides valued non-aromatic nitrogen heterocycles with three-dimensional display of functionality, we believe that it will be even more impactful for the discovery of completely new drug leads and chemical biology tool compounds.7 Indeed, much of our current efforts in collaboration with researchers in industry and academics are directed at leveraging this chemistry to the discovery of potent and selective druglike compounds to receptors and enzymes. These endeavors will be published in due course.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The National Institutes of Health Grant R35GM122473 supported much of the research described in this Account and is gratefully acknowledged. The authors would like to thank the many current and past co-workers and collaborators for their essential contributions to the research described in this Account. We would especially like to thank Bob Bergman for a productive and highly enjoyable collaboration, which resulted in many of the early results described in this Account.

ABBREVIATIONS

- TMS

trimethylsilyl

- DMAD

dimethyl acetylene dicarboxylate

Biographies

Danielle N. Confair received her B.S. in chemistry from the University of Richmond in 2016 conducting research under the guidance of Professor C. Wade Downey. She is currently a Ph.D. student in Professor Jonathan A. Ellman’s research group at Yale University studying rhodium-catalyzed C–H activation methods for the synthesis and elaboration of N-heterocycles along with their application to the identification of bioactive compounds.

Sun Dongbang received her B.S. and M.S. from Korea University under the guidance of Professor Jong Seung Kim. She earned her Ph.D. under the direction of Professor Jonathan A. Ellman from Yale University, where she worked on the total synthesis of opioids and Co-catalyzed synthetic methods. She is currently a postdoctoral researcher in Professor Abigail G. Doyle’s group at Princeton University.

Jonathan A. Ellman received his B.S. from MIT and his Ph.D. from Harvard University under the direction of David Evans. He carried out postdoctoral research with Peter Schultz at the University of California at Berkeley, and in 1992 he became a member of the chemistry faculty at the same institution. In 2010, he joined the chemistry and pharmacology faculty at Yale University. His laboratory focuses on the development of practical and efficient new synthesis methods and on the design of chemical tools for biological inquiry.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Duttwyler S; Chen S; Takase MK; Wiberg KB; Bergman RG; Ellman JA Proton Donor Acidity Controls Selectivity in Nonaromatic Nitrogen Heterocycle Synthesis. Science 2013, 339, 678–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Divergent regioselective and stereoselective elaboration of dihydropyridines give highly functionalized tetrahydropyridines. The dihydropyridines are prepared in a single step by a Rh-catalyzed C−H bond alkenylation/electrocyclization cascade using readily available alkyne and α,β-unsaturated imine inputs.

- 2.Chen S; Bacauanu V; Knecht T; Mercado BQ; Bergman RG; Ellman JA New Regio- and Stereoselective Cascades via Unstabilized Azomethine Ylide Cycloadditions for the Synthesis of Highly Substituted Tropane and Indolizidine Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 12664–12670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Readily prepared silyl substituted dihydropyridines undergo protonation and alkylation triggered desilylation to give unstabilized azomethine ylides that upon reaction with dipolarophiles provide indolizidines, tropanes, and complex polycyclic heterocycles in good yields and with high regioselectivity and diastereoselectivity.

- 3.Walker MM; Koronkiewicz B; Chen S; Houk KN; Mayer JM; Ellman JA Highly Diastereoselective Functionalization of Piperidines by Photoredox-Catalyzed α-Amino C–H Arylation and Epimerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 8194–8202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Face-selective catalytic hydrogenation of N-aryl 1,2-dihydropyridines affords piperidines with high stereoselectivity. Photoredox catalyzed C–H arylation of the piperidines with cyanoarenes initially proceeds with poor stereoselectivity, but in situ photoredox-mediated epimerization provides the more stable isomer of the arylated product.

- 4.Dongbang S; Pedersen B; Ellman JA Asymmetric Synthesis of (−)-Naltrexone. Chem. Sci 2019, 10, 535–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A Rh(I)-catalyzed intramolecular C–H alkenylation and torquoselective electrocyclization cascade affords the hexahydroisoquinoline bicyclic framework that upon elaboration efficiently provides the morphinan core and requisite functionality of (−)-naltrexone, an opioid antagonist used to manage drug abuse.

- 5.Vitaku E; Smith DT; Njardarson JT Analysis of the Structural Diversity, Substitution Patterns, and Frequency of Nitrogen Heterocycles among U.S. FDA Approved Pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 10257–10274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovering F; Bikker J; Humblet C Escape from Flatland: Increasing Saturation as an Approach to Improving Clinical Success. J. Med. Chem 2009, 52, 6752–6756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boström J; Brown DG; Young RJ; Keserü GM Expanding the Medicinal Chemistry Synthetic Toolbox. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2018, 17, 709–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colby DA; Bergman RG; Ellman JA Stereoselective Alkylation of α,β-Unsaturated Imines via C–H Bond Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 5604–5605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colby DA; Bergman RG; Ellman JA Synthesis of Dihydropyridines and Pyridines from Imines and Alkynes via C−H Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 3645–3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fallon BJ; Garsi J-B; Derat E; Amatore M; Aubert C; Petit M Synthesis of 1,2-Dihydropyridines Catalyzed by Well-Defined Low-Valent Cobalt Complexes: C–H Activation Made Simple. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 7493–7497. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin RM; Bergman RG; Ellman JA Synthesis of Pyridines from Ketoximes and Terminal Alkynes via C–H Bond Functionalization. J. Org. Chem 2012, 77, 2501–2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romanov-Michailidis F; Sedillo KF; Neely JM; Rovis T Expedient Access to 2,3-Dihydropyridines from Unsaturated Oximes by Rh(III)-Catalyzed C–H Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 8892–8895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parthasarathy K; Jeganmohan M; Cheng C-H Rhodium-Catalyzed One-Pot Synthesis of Substituted Pyridine Derivatives from α,β-Unsaturated Ketoximes and Alkynes. Org. Lett 2008, 10, 325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bull JA; Mousseau JJ; Pelletier G; Charette AB Synthesis of Pyridine and Dihydropyridine Derivatives by Regio- and Stereoselective Addition to N-Activated Pyridines. Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 2642–2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva EMP; Varandas PAMM; Silva AMS Developments in the Synthesis of 1,2-Dihydropyridines. Synthesis 2013, 45, 3053–3089. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mesganaw T; Ellman JA Convergent Synthesis of Diverse Tetrahydropyridines via Rh(I)-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization Sequences. Org. Process Res. Dev 2014, 18, 1097–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. The structure, bioactivity, literature, and clinical trials of LSD, ergotamine, vinblastine, vincristine, and dehydroemetine can be obtained by searching the compound name in PubChem.

- 18.Duttwyler S; Lu C; Rheingold AL; Bergman RG; Ellman JA Highly Diastereoselective Synthesis of Tetrahydropyridines by a C–H Activation–Cyclization–Reduction Cascade. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 4064–4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gribble W, Sodium G Borohydride in Carboxylic Acid Media: A Phenomenal Reduction System. Chem. Soc. Rev 1998, 27, 395–404. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson F Allylic Strain in Six-Membered Rings. Chem. Rev 1968, 68, 375–413. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen S; Chan AY; Walker MM; Ellman JA; Houk KN π-Facial Selectivities in Hydride Reductions of Hindered Endocyclic Iminium Ions. J. Org. Chem 2019, 84, 273–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mesganaw T; Ellman JA Preparative Synthesis of Highly Substituted Tetrahydropyridines via a Rh(I)-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization Sequence. Org. Process Res. Dev 2014, 18, 1105–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu H-J; Shia K-S; Shang X; Zhu B-Y Organocerium Compounds in Synthesis. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 3803–3830. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ocampo R; Dolbier WR The Reformatsky Reaction in Organic Synthesis. Recent Advances. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 9325–9374. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang H; Houk KN Torsional Control of Stereoselectivities in Electrophilic Additions and Cycloadditions to Alkenes. Chem. Sci 2014, 5, 462–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duttwyler S; Chen S; Lu C; Mercado BQ; Bergman RG; Ellman JA Regio- and Stereoselective 1,2-Dihydropyridine Alkylation/Addition Sequence for the Synthesis of Piperidines with Quaternary Centers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 3877–3880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavaud C; Massiot G, The Iboga Alkaloids. In Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products 105, Kinghorn AD; Falk H; Gibbons S; Kobayashi J, Eds. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp 89–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin RM; Bergman RG; Ellman JA Synthesis of Isoquinuclidines from Highly Substituted Dihydropyridines via the Diels–Alder Reaction. Org. Lett 2013, 15, 444–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.García-Garrido SE, Catalytic Dimerization of Alkynes. In Modern Alkyne Chemistry, Trost BM; Li CJ, Eds. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: 2014; pp 299–334. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ischay MA; Takase MK; Bergman RG; Ellman JA Unstabilized Azomethine Ylides for the Stereoselective Synthesis of Substituted Piperidines, Tropanes, and Azabicyclo[3.1.0] Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 2478–2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Padwa A; Dent W Use of N-[(Trimethylsilyl)methyl]amino Ethers as Capped Azomethine Ylide Equivalents. J. Org. Chem 1987, 52, 235–244. [Google Scholar]

- 32. The structure, bioactivity, literature, clinical trials, and usage of maraviroc, atropine and spiriva can be obtained by searching the compound name in PubChem.

- 33.Pandey G; Bagul TD; Sahoo AK [3 + 2] Cycloaddition of Nonstabilized Azomethine Ylides. 7. Stereoselective Synthesis of Epibatidine and Analogues. J. Org. Chem 1998, 63, 760–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peese KM; Gin DY Asymmetric Synthetic Access to the Hetisine Alkaloids: Total Synthesis of (+)-Nominine. Chem. Eur. J 2008, 14, 1654–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coldham I; Hufton R Intramolecular Dipolar Cycloaddition Reactions of Azomethine Ylides. Chem. Rev 2005, 105, 2765–2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michael JP Indolizidine and Quinolizidine Alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep 2008, 25, 139–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bélanger G; Darsigny V; Doré M; Lévesque F Highly Diastereoselective Synthesis of Substituted Pyrrolidines Using a Sequence of Azomethine Ylide Cycloaddition and Nucleophilic Cyclization. Org. Lett 2010, 12, 1396–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker MM; Chen S; Mercado BQ; Houk KN; Ellman JA Formation of Aminocyclopentadienes from Silyldihydropyridines: Ring Contractions Driven by Anion Stabilization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 6605–6609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McManus JB; Onuska NPR; Nicewicz DA Generation and Alkylation of α-Carbamyl Radicals via Organic Photoredox Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 9056–9060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xuan J; Cheng Y; An J; Lu L-Q; Zhang X-X; Xiao W-J Visible Light-Induced Intramolecular Cyclization Reactions of Diamines: A New Strategy to Construct Tetrahydroimidazoles. Chem. Comm 2011, 47, 8337–8339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McNally A; Prier CK; MacMillan DWC Discovery of an α-Amino C–H Arylation Reaction Using the Strategy of Accelerated Serendipity. Science 2011, 334, 1114–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen S; Mercado BQ; Bergman RG; Ellman JA Regio- and Diastereoselective Synthesis of Highly Substituted, Oxygenated Piperidines from Tetrahydropyridines. J. Org. Chem 2015, 80, 6660–6668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rinner U; Hudlicky T, Synthesis of Morphine Alkaloids and Derivatives. In Alkaloid Synthesis, Knölker H-J, Ed. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp 33–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phillips EM; Mesganaw T; Patel A; Duttwyler S; Mercado BQ; Houk KN; Ellman JA Synthesis of ent-Ketorfanol via a C–H Alkenylation/Torquoselective 6π Electrocyclization Cascade. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 12044–12048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manmade A; Dalzell HC; Howes JF; Razdan RK (−)-4-Hydroxymorphinanones: Their Synthesis and Analgesic Activity. J. Med. Chem 1981, 24, 1437–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Varghese V; Hudlicky T, A Short History of the Discovery and Development of Naltrexone and Other Morphine Derivatives. In Natural Products in Medicinal Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim: 2014; pp 225–250. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vargas DF; Larghi EL; Kaufman TS The 6π-Azaelectrocyclization of Azatrienes. Synthetic Applications in Natural Products, Bioactive Heterocycles, and Related Fields. Nat. Prod. Rep 2019, 36, 354–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diao T; Stahl SS Synthesis of Cyclic Enones via Direct Palladium-Catalyzed Aerobic Dehydrogenation of Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 14566–14569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]