Abstract

People living with HIV (PWH) are at higher risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and stroke in comparison to their non-infected counterparts. The ABCS (aspirin-blood pressure control-cholesterol control-smoking cessation) reduce atherosclerotic (ASCVD) risk in the general population, but little is known regarding strategies for promoting the ABCS among PWH. Guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), we designed multilevel implementation strategies that target PWH and their clinicians to promote appropriate use of the ABCS based on a 10-year estimated ASCVD risk. Implementation strategies include patient coaching, automated texting, peer phone support, academic detailing and audit and feedback for the patient’s clinician. We are evaluating implementation through a stepped wedge cluster randomized trial based on the Reach-Effectiveness-Adoption-Maintenance/Qualitative-Evaluation-for-Systematic-Translation (RE-AIM/QuEST) mixed methods framework that integrates quantitative and qualitative assessments. The primary outcome is change in ASCVD risk. Findings will have important implications regarding strategies for reducing ASCVD risk among PWH.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Risk factors, HIV, Primary prevention, Implementation effectiveness

Background

People living with HIV (PWH) are living longer lives now because of effective antiretroviral therapy (ART).1 However, atherosclerotic (AS) cardiovascular disease (CVD, ASCVD) is more common among PWH than in the general population even when controlling for traditional CVD risk factors, resulting in significant ASCVD morbidity and mortality.2 Evidence shows associations between HIV and inflammatory and coagulation markers, including interleukin (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP) and D-dimer.2 Changes within lipid subclasses, i.e. lower high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels were reported as inversely associated with IL-6 levels3 and suggest additional contributions to ASCVD risk. For these reasons, HIV-infection is regarded as a risk-enhancing factor to consider when estimating a person’s 10-year ASCVD risk.4 This increase in risk is present even when there is complete HIV suppression with ART.2

Evidence-based interventions for reducing CVD include the appropriate use of aspirin, blood pressure control, cholesterol reduction, and smoking cessation (i.e. ABCS).5 The ABCS are endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) and an integral aspect of the Million Hearts Initiative, with recent recommendations de-emphasizing the role of aspirin in primary prevention.6 Yet the ABCS are underutilized in the care of PWH,7–12 resulting in potentially avoidable ASCVD morbidity and mortality.

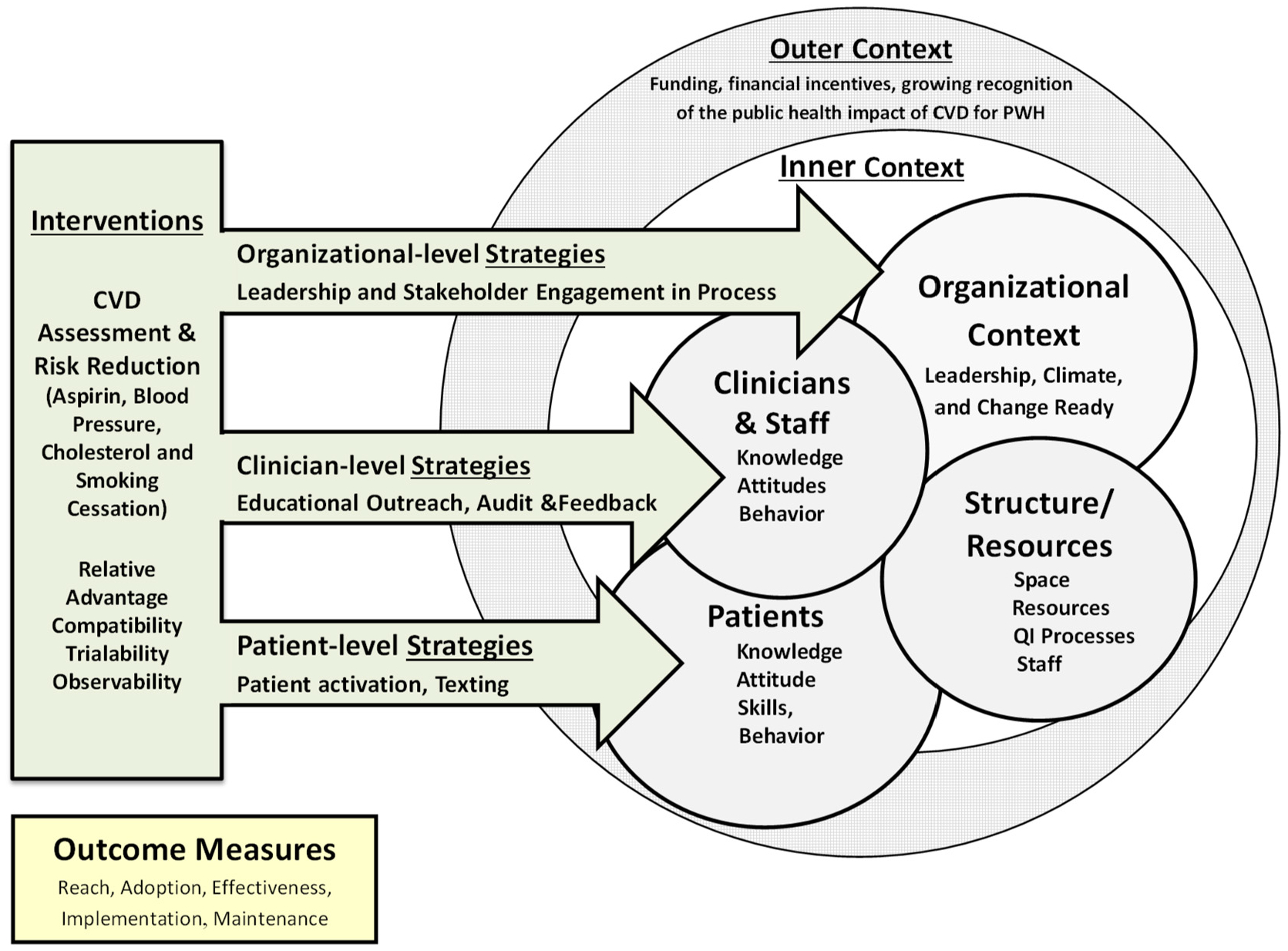

To date, there are no proven strategies for promoting appropriate uptake of the ABCS for primary prevention of ASCVD among PWH. To address this evidence-to-practice gap, we designed the ABCS for HIV trial. We drew upon evidence-based strategies for promoting uptake of evidence-based interventions for clinicians and for the general patient population. We sought to promote shared decision-making regarding the ABCS among PWH and their clinicians using patient and clinician targeted strategies guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) for our conceptual model for implementation (Fig. 1).13 We used the RE-AIM-QuEST framework to evaluate implementation. RE-AIM specifies four domains: Reach, Adoption, Implementation (including cost) and Maintenance. The Qualitative Evaluation for Systematic Translation (QuEST) component integrates RE-AIM quantitative and qualitative measures to inform questions regarding who benefits or not, how, why and under what circumstances, beginning at implementation.14 We are testing the following specific hypotheses using a hybrid type II,15 stepped wedge cluster randomized trial.

Implementation will reduce estimated ASCVD 10-year risk among PWH.

Implementation will improve provision of the ABCS among PWH.

Implementation will improve patient adherence to ABCS medications.

Implementation will improve body mass index, diet, physical activity and safe drinking.

Implementation will improve clinician-PWH shared decision-making regarding ABCS.

Implementation will not adversely affect viral load suppression.

Fig. 1.

Implementation using the CFIR.

Methods/design

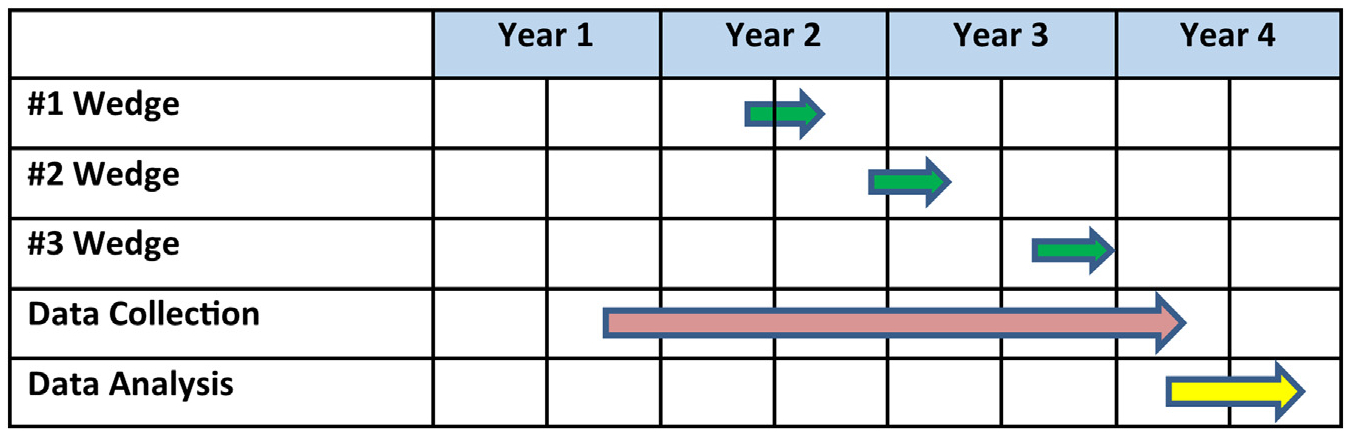

ABCS for HIV involves a multicomponent implementation strategy for promoting uptake of the ABCS by targeting PWH based on ASCVD risk and their HIV clinicians. The unit of randomization is the practice and the primary outcome is ASCVD risk measured at the patient level. We will roll out implementation using a stepped wedge cluster randomized trial design in which the implementation strategies are sequentially rolled out to participating practices, clinicians and patients in three steps separated by 6–8 months. We chose this design to implement proven strategies and to ensure all practices receive the intervention. Practice enrollment began November 15, 2018. The nine practices include academic medical centers, freestanding HIV practices and federally qualified health centers providing care to PWH in New York, NY (five practices), Rochester, NY (two practices), and Dallas, TX (two practices).

Patient and clinician eligibility criteria

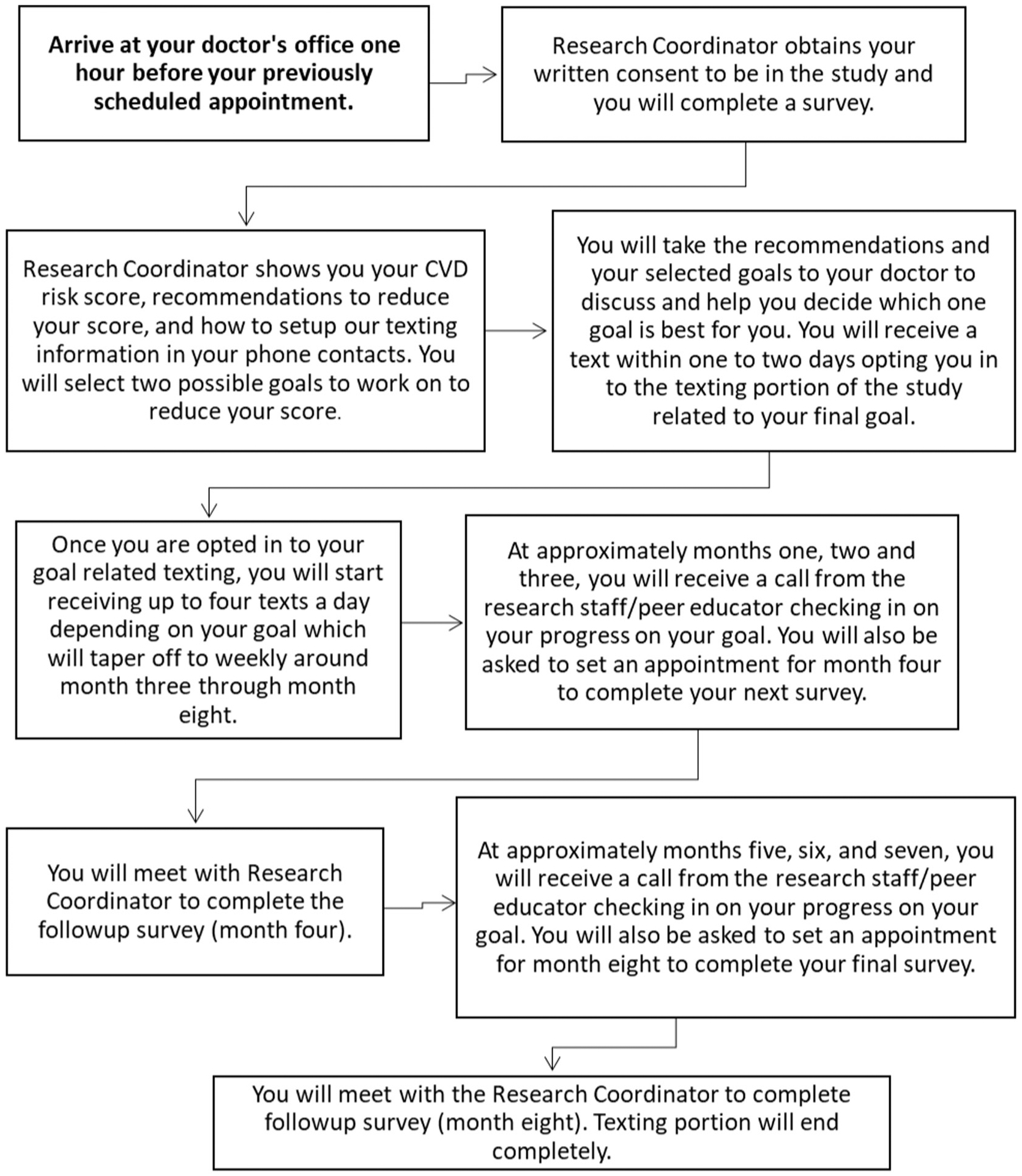

Eligibility criteria are shown in Table 1. We are recruiting PWH with at least 5% 10-year ASCVD risk. We chose this risk calculated by the 10-year ASCVD tool because the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/AHA/National Lipid Association (NLA) guidelines4 state that this is the threshold risk at which statin therapy should be discussed and HIV results in significantly higher risk than estimated. Acting under the auspices of the practice, we work with clinical staff to identify a strategy that best suits their workflow to conduct outreach by phone to potential patients. We supplement this modality with face-to-face interactions at the practice. The study has been approved by the central Institutional Research Board (IRB) at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC), with reliant review agreements at each of the participating sites. Informed consent is conducted in the patient’s preferred language (English or Spanish). Patient subject study flow is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Patient, clinician, and practice eligibility.

| Criteria | Patient | Clinician | Practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion | Age 40–75 years by 7/1/2018, HIV/AIDS diagnosis, receipt of care within the participating practice, at ≥5% risk for ASCVD as calculated using the ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus, current lipid values, i.e. within 15 months of enrollment, own a texting capable cellphone, proficient in English or Spanish, is willing to participate, and expects to remain in the study throughout the entire study period. | Physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant who provides direct HIV care within a participating practice and is willing to participate. | Serve a cohort of at least 100 HIV patients, have an EHR and agree to collaborate on implementing feasible adaptations of these strategies. |

| Exclusion | Experienced a prior cardiac or vascular event such as myocardial infarction (MI) or cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or have had a ASCVD procedure such as installation of a stent or angioplasty, have peripheral vascular disease, intermittent claudication or peripheral arterial disease, current participation in other CVD trials, have had stage 5 chronic kidney disease, or on renal dialysis, pregnant, or lacks capacity to consent. | Plans to leave the practice within 12 months. |

Fig. 2.

Patient subject study flow.

Randomization

The offsite URMC study biostatistician randomly assigned practices along with consenting clinicians and their consenting patients to different wedges (Fig. 3). Randomization was performed using randomization tables stratified by city (i.e., NYC, Rochester, Dallas), in block sizes of three. Nine practices were randomized to the three wedges. Yet because there are not three participating clinical practices in each of the three cities, the blocks are unbalanced.

Fig. 3.

Project timeline.

Implementation strategies

Guided by the internal context within CFIR (Fig. 1), the implementation strategies target practice leadership (active engagement and organizational support), HIV clinicians (knowledge attitudes and skills related to assessment of ASCVD risk and shared decision-making with PWH regarding clinically appropriate use of the ABCS) and PWH (knowledge, attitude and skills that support selection of ABCS based on ASCVD risk and shared decision-making).

Leadership implementation strategies involve ensuring project goals align with those of the practice, partnering with the organization to obtain relevant data and to assist with patient and clinician targeted strategies.16 We operationalize these through separate in-person meetings with medical directors and/or administrators from each practice.

Clinician implementation strategies involve two ABCS educational outreach sessions,17 six ABCS online learning modules and two audit and feedback reports on use of ABCS.18 Clinicians first receive a group-based educational overview of the project including the interventions, followed by two academic detailing sessions delivered remotely to each clinician by clinical pharmacists who have been trained in academic detailing.19 These sessions are designed around the learning needs of each clinician. The first session focuses on one of the ABCS chosen by the clinician and the follow-up sessions review the clinician’s experiences with implementing it into his or her practice. During these sessions the detailers refer the clinician to the online learning modules that address use of the ACC/AHA ASCVD risk calculator and based on the preference of the clinician, address one or more of the ABCS. Given recent uncertainty regarding the relative harms and benefits for aspirin for primary ASCVD prevention,5 the learning modules and academic detailing sessions address use of an aspirin risk calculator to estimate harms and benefits, including appropriate prescribing or deprescribing. The learning modules are estimated to take 20–30 min to complete and are accredited for continuing medical education credit (CME). The audit and feedback reports provide the clinician with average ASCVD risk scores of their patients, calculated from the electronic health record (EHR) data, along with rates of the therapies specified in the ABCS, e.g. uncontrolled BP, no evidence of a statin prescription and current smoking.

Participant implementation strategies involve increasing patient activation through one coaching session20 and short messaging service (SMS) texting,21,22 with as-needed support by peer coaches.23 The initial patient coaching is provided by trained research assistants (RAs) who meet face-to-face with patients shortly after they enroll in the study. The coaching session begins with an exercise in “values affirmation,” designed to enhance the patients’ motivation to improve their health.24 Coaches then provide CVD and ABCS education, emphasizing knowledge that patients can use for informed goal selection. They review their ASCVD risk score (calculated based on data from the EHR) and invite the patient to select one of the ABCS based on the recommendations produced by the calculator. Additionally, patients note their personal preferences for further discussion and confirmation with their clinician.

The second patient component uses automated text messages, delivered over eight months, that are tailored to the patient’s chosen ABCS strategy and support the patient with implementation and goal-setting. Text messages are delivered using a library of text messages we developed and piloted according to an algorithm we developed. Text messages are based on use behavior change techniques that target behavioral determinants,25 i.e. knowledge, affirmation/reinforcement, tailored information, self-efficacy adherence support and goal commitment at tailored frequencies. Sample text messages include: “Eating a heart healthy diet and taking blood pressure medicine can lower your blood pressure.” and “Cravings will get weaker and less frequent with every day that you don’t smoke. What is your craving level? Text 1 for HI, 2 for MED, or 3 for LOW.” The texts are delivered through a commercial vendor (2020 Mosio) with an online tracking log of text messages. Patients receive small, periodic incentives to optimize engagement. Texting tapers in frequency from several times per week early in the intervention, to monthly during the last five months of the 8-month texting period.

The third patient component involves use of peer coaches, i.e. PWH with prior experience in HIV engagement or advocacy work. Peer coaches are trained to support patients in implementing their chosen goal and assist patients in addressing problem solving barriers.26 Peers utilize motivational interviewing techniques in months 2–8 to support patients, on an as needed basis, in following through on their chosen ABCS strategy.

Baseline data collection

Following informed consent, we electronically extract data from the EHR and the Research Assistant (RA) administers surveys to patients. Data for the primary outcome ASCVD risk are derived from the EHR at the end of the study. These data enable us to calculate ASCVD risk scores for all participants beginning at roughly the same baseline period. We augment EHR data with patient demographic characteristics (not available in the EHR), overall medication adherence, tobacco and alcohol use, lifestyle factors, physical activity, diet, shared decision making, patient activation, health literacy, acculturation, perceived numerical literacy and readiness to change. These data are used to validate EHR data (e.g. smoking status) and provide data that are not available in the EHR (e.g. physical activity, diet, etc.).

Follow-up data collection

At the end of the study, we will extract longitudinal EHR data from 2018 to 2022 to assess change in patient-level ASCVD risk. We collect supplementary patient survey assessments at baseline, 4-months and 8-months post baseline. Each of the clinical practices key informants are interviewed at approximately 12-months post baseline to understand barriers and facilitators to implementation of the ABCS at their respective practice. All study measurements obtained from patients and practices are performed by trained RAs.

Outcomes

We are using RE-AIM for our outcome evaluation framework.27 The primary effectiveness outcome is change from a common baseline to 12 months in ASCVD risk using data extracted from the EHR over the time periods. Secondary outcomes, including changes in systolic blood pressure (SBP) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, are obtained from the EHR over the same time periods while changes in smoking status are assessed through the patient’s report at baseline and follow-up. We also explore changes in the patient’s body mass index (BMI), hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c), HIV viral load suppression, risky drinking (Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System [BRFSS]), physical activity (Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity), diet (Starting the Conversation), and changes in aspirin prescription/de-prescription and patient adherence. Measures and times points for outcomes are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Study measures.

| Construct/topic of interest | Measure/instrument | Patient | Clinician | Data source | Collection time points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary effectiveness outcome | |||||

| Changes in cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk [age, sex, race, SBP/DBP total cholesterol HDL-C, LDL-C, diabetes, smoking status/date quit, taking antihypertensive, statin, aspirin] | American College of Cardiology (ACC) ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus48 | x | EHR | Continuous | |

| Blood pressure | Office measure | x | EHR | Continuous | |

| Cholesterol | Office measure | x | EHR | Continuous | |

| Smoking | BRFSS | x | Survey, EHR | T0–T3 Continuous | |

| Secondary effectiveness outcomes | |||||

| HIV disease status | HIV viral load (both actual level and whether undetectable or not) | x | EHR | Continuous | |

| Risky drinking | BRFSS | x | Survey | T0–T2 | |

| Physical activity | Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity | x | Survey | T0–T2 | |

| Diet | Starting the conversation | x | Survey | T0–T2 | |

| Shared decision making | CollaboRATE | x | Survey | T0–T2 | |

| Patient adherence to chosen intervention | Adherence to Refills and Medication Scale (ARMS) | x | Survey | T0–T2 | |

| Co-variates, instrumental variables | |||||

| Patient activation | Patient Activation Measure (PAM-13) | x | Survey | T0–T2 | |

| Health literacy | Prescription Label | x | Survey | T0–T2 | |

| Acculturation | Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH) | x | Survey | T0 | |

| Perceived numerical ability | Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS) | x | Survey | T0–T2 | |

| Change readiness | Readiness to Change Ruler | x | Survey | T0–T2 | |

| BMI & HbA1c | Medical Record | x | EHR | Continuous | |

| Patient demographics and other social risk factors | Age, sex, race, ethnicity, income, out of pocket medical costs, travel distance and method, cell phone type, changes in clinician/site, food security, family history of CVD or CHD, marital/partner status, drug and alcohol use, insurance status, language | x | Survey, | T0 | |

| Clinician stakeholders | Barriers and facilitators to implementation, clinical specialty, number of years in practice, age, sex | x | Survey | T0, T2 |

T0 = Baseline; T1 = 4-months post baseline (4 months into intervention); T2 = Post Intervention (8 months post baseline); T3 = 12-months post-baseline.

Sample size calculation

To ascertain the statistical power associated with this study design, we fixed the number of patients per clinician to 12 and assumed that nine practices will contribute the following number of clinicians: 4, 4, 4, 4, 4 (five practices in NYC); 6, 10 (two practices in Rochester); 2, 12 (two practices in Dallas). By convention, each patient contributes data at each of three waves in a stepped wedge design with three wedges. If the mean 10-year ASCVD risk score is 26 at baseline (i.e. during the control period) and 20 during the intervention period, the within-cluster standard deviation is 16, and the between-cluster standard deviation is six, then the study design has between 75 and 99% statistical power to reject the null hypothesis of no difference in the ASCVD risk score,28 using a 2-sided test with a 5% Type I (alpha) error rate. The range in statistical power is due to the randomness in the wedge, when the smallest and largest practices will be randomized, and the potential for severe imbalance between the number of endpoints during control and intervention periods. In an extreme scenario, the statistical power could be as low as 75%.

Quantitative data analysis

This study employs a stepped wedge clustered randomized trial design with stratification by region and clinicians and their patients clustering within practices. Each practice, including all consenting clinicians and their consenting patients, begin the trial as a control (usual care). Thereafter, these clusters are randomized into three waves (‘wedges’) which will determine when these clusters receive the clinician and patient implementation strategies. The randomization is stratified by geographic region so that not all practices within same region are randomized to the same wedge. The study biostatistician has generated the stratified, permuted, block allocation using a computerized, randomization program. Neither study personnel, participating clinicians, nor patients will be blinded to start dates. Following the stepped wedge intervention phase and final EHR data extraction, we will conduct a mixed methods analysis, involving both quantitative and qualitative measures. Data obtained from the EHR will be supplemented with surveys of patients based on brief validated scales and open-ended questions suitable for qualitative coding and analysis. We will also conduct semi-structured interviews with clinicians and patients to capture barriers and facilitators to the implementation process as well as key implementation adaptations. The proposed data analyses follow a rich literature for the analysis of longitudinal data1 for which the stepped wedge trial design is a special case.

Analysis of primary endpoint

The primary outcome is change in ASCVD risk, among patients, as assessed by the ACC/AHA ASCVD Risk Estimator.29 This tool is based on patient age, sex, race, smoking, diabetes, systolic blood pressure, lipids (total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol) and appropriate use of aspirin, antihypertensive medications and statins. Risk scores (and changes) will be aggregated at the clinician and practice levels. We will calculate scores based on EHR-abstracted data at baseline and study completion, and we will likewise conduct pre- and post-surveys of patients to obtain data, which are less likely to be reliably recorded in the EHR, for example, smoking status and aspirin intake. Accordingly, consistent with principles for pragmatic implementation trials,15,30,31 we will rely on existing data from the EHR to assess the primary outcomes and use data collected during the process of care to assess implementation.

Following general principles for stepped wedge cluster randomized trials set forth by Hughes et al,32 the principal statistic for the primary endpoint will be an F-test of the intervention effect through the linear mixed model in Eq. (1), using appropriate methods to adjust the denominator degrees of freedom for small numbers of clusters (e.g. Hughes and colleagues32,33):

where the primary outcome Yijk is the ASCVD risk score for the jth subject (j=1,…,ni) nested within the ith practice (Pi, i=1,…, 9), repeated at the kth time point (k=1,⋯,mijk). In other words, there are different numbers of patients in each clinical practice and we expect each patient may have variable number of observations. The fixed effects include: μ, the overall mean ASCVD risk score in the control period, (γ1, γ2, γ3) are blocking factors corresponding to cities (B1,B2,B3) for which no inference will be drawn (here, γ1 = 0, by design), s(tijk) is a function of time defined below, xijk are time-dependent treatment indicators (1 = if the ith practice has begun the intervention rollout by time tijk, 0 = otherwise) and θ is the treatment effect. In the primary analysis, we define our smooth function of time via regression splines:

where (κ1,κ2,κ3) are knots and (ν1,ν2,ν3,ν4) are parameters associated with the linear spline. The knots are defined as the intervention rollout dates for wedges 1, 2, and 3. The random effects are: αi is a mean-zero Gaussian practice effect with variance , αj(i) is a mean-zero Gaussian patient-level effect for the jth patient nested within the ith practice independent from αi and has variance , and eijk is a mean-zero Gaussian error with variance independent from both αi and αj(i). We allow for the possibility of serial correlation among temporally-observed, repeated outcomes from the same patient, nested within practice, through the term Wj(i)(tijk). For continuous outcomes, we will use the linear mixed model (LMM) framework; for discrete outcomes, we will use the generalized linear mixed model framework (GLMM). Importantly, we will use Satterthwaite’s method to adjust the degrees of freedom in F- and t-tests when drawing statistical inference from a stepped wedge cluster randomized trial with a small number of clusters. The primary endpoint will be analyzed under an intent-to-treat (ITT) principle. That is, the step or wave to which patients were randomly assigned at baseline will be their “treatment” assignment for the statistical analysis. We will also consider other statistical analyses that adjust for post-randomization treatment decisions, e.g. switching “treatments” and/or non-adherence, will be considered secondary analyses.

To the extent possible, we will include data from all patients and all clinicians, even if they elect to dropout or leave the study. However, some missing data is expected and we propose to use multiple imputation to address it in the statistical analysis. Multiple imputation is a general strategy for drawing statistical inference in the presence of missing data and works similarly when the missing variables are endpoints or explanatory variables. Our primary endpoint, ASCVD risk score, is a continuous score computed from several other variables (age, sex, race, diabetes, smoking status, SBP, cholesterol (total, HDL and LDL)), use of antihypertensive medications, aspirin and statins; most variables are time-varying, where age, sex, race, and diabetes are the time-constant variables. In order to compute the ASCVD risk score at each clinic visit, the input variables must be present. The general strategy will be to construct a rectangular data set with each row representing one patient. Then, we will use multiple imputation using chained equations (MICE) to impute the missing values; in MICE, the chained equations will be run for 10 cycles and then the imputed values retained for 1 “complete” data set. ASCVD risk scores can then be computed from this imputed data set. This process will be repeated 20 times to produce 20 multiply imputed data sets. We will use Rubin’s rules to draw statistical inferences from multiply imputed data sets.34

Secondary quantitative outcomes including covariates will be evaluated among both patients and clinicians. At the clinician level, we will assess an index of clinician-relevant ABCS behavior, (i.e. prescription of aspirin and statins, blood pressure control, smoking cessation counseling) based on EHR abstraction and their patients’-self-reported prescription information. At the patient level we will assess use of recommended practical measures for reducing cardiovascular events.35 These include: BMI and blood pressure (EHR), and smoking (BRFSS36), physical activity (Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity36,37), risky drinking (BRFSS36) and diet (Starting the Conversation38). We will also assess shared decision-making using (CollaboRATE39), and patient adherence to their chosen intervention using the Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS40), a validated adherence scale. In addition, we will assess patients’ acculturation status using the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH41), patient activation using the validated Patient Activation Measure (PAM42), readiness for cardiovascular risk-reduction behavior changes using the Readiness to Change Ruler43 and patient numeracy and literacy skills using the Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS44) and the HIV Prescription Label tool from the Parkland Health System. Last, we will assess unintended consequences by assessing decreases in HIV viral load suppression based on EHR laboratory data abstraction, as we have done previously.45 The same generalized linear mixed model (described above) will be used to assess the primary endpoint. We will utilize the equation proposed by Hughes et al to evaluate secondary outcomes.

Analyses of patient & clinician subgroups

The team will investigate whether other variables mediate or moderate the intervention effect. We will explore the intervention effects in pre-specified subgroups through the regression model in Eq. (1), adding additional terms to the statistical model for subgroup indicators and interaction terms. Specific patient-level variables defining pre-specified subgroups of interest include age, demographics, sex at birth, gender identity, socio-economic status (SES), insurance type (public/Medicaid vs private), enrollment in the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP), language (English vs Spanish), illicit drug user, nutrition, diet and exercise. Clinician-level variables of interest include an indicator of infectious disease training, age, sex, years in practice and specialty.

Qualitative analysis

Using the QuEST framework developed by Forman et al.,14 we created open ended questions that corresponded to each of the quantitative measures of RE-AIM (Table 3). RE-AIM-QuEST formalizes the mixed methods approach that Holtrop et al. intend for RE-AIM.46 To assess the process of implementation, we will use mixed methods, analyzed at the patient and clinician levels.47 Qualitative assessment can yield critical insights regarding why, when and how implementation succeeds or not.24 Accordingly, the qualitative assessment will involve the following data sources: text fields from surveys, research assistant and academic detailing logs and semi-structured interviews with 6–8 patients/practice, 3–4 clinicians/practice, all enrollers, clinical pharmacists who conduct the academic detailing and all leaders from each practice. The logs will be used to keep track of attendance of the clinicians as well as material covered during the sessions. We will audiotape and transcribe interviews conducted with practice staff and organize data using the QuEST Framework Method, an approach involving qualitative thematic analysis.27 The RE-AIM QuEST framework will be used as a starting point for codes and during the process, other relevant codes will be added related to the CFIR, (i.e. outer and inner contexts) such as the ABCS interventions and attitudes of individuals.24 Using this framework, we will compare and contrast data to describe and interpret the implementation process. A mixed methods approach will be used to integrate the RE-AIM results from the quantitative and qualitative data. We will enter all data into the MAXQDA mixed-methods software program to facilitate coding and analysis. Once consensus among the coding group is reached, two independent coders with experience in qualitative coding will apply these codes to the text and resolve differences by discussion and consensus.

Table 3.

Summary of implementation outcome measures based on the RE-AIM QuEST framework.

| RE-AIM | QuEST | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Data source | Qualitative | Data source | |

| Reach |

|

Enrollment logs | What were patient barriers and reasons for not enrolling? |

|

| Effectiveness |

|

|

What factors across practices explain variation in effectiveness? |

|

| Adoption |

|

Enrollment logs | What were the clinician reasons for not enrolling or dropping out? |

|

| Implementation | Patients

|

|

|

|

| Maintenance |

|

Documentation of continuation of components | What reasons do practices have for continuing or not? | Semi-structured interviews with clinicians |

Discussion

The ABCS for HIV protocol will test an evidence-informed, implementation strategy for primary prevention of ASCVD in PWH cared for in HIV practices. Findings have important clinical implications for the reduction of CVD morbidity and mortality in this at risk population. The ABCS are the framework by which the Million Hearts® 2022 national initiative, co-led by the CDC and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), will attempt to prevent one million heart attacks and strokes within five years.6 Our population is more complex because the inadequacy of the ASCVD risk calculator in guiding therapy in the PWH population necessitates that a more personalized approach be taken in primary prevention requiring informed and shared, clinician-patient, decision-making regarding primary prevention interventions.

Clinician evaluation of ASCVD risk among PWH is hampered by the lack of clinical trial data in this population. The goal of the ABCS for HIV protocol is to enable an efficient clinician-patient discussion and workflow to discuss ASCVD risk with the goal of modifying the natural history of subclinical ASCVD that remains under-recognized and under-treated. To date, there is little empirical evidence to guide implementation of the ABCS into practice for PWH. It remains unclear how the clinician may attempt to further risk stratify participants that have an uncertain, borderline risk score. Our evidence-based, multilevel strategies offer promise for closing the prevalent evidence-to-practice gap.

The use of peer-coaches and the use of a texting platform in the management of ASCVD risk factor s and behavioral change will foster patient activation. This aspect of telehealth shows promising results and this trial will contribute to its potential use in real life settings. The use of peers in this context is novel. Peers enhance cultural appropriateness and accessibility of the intervention.

It is reasonable in lower risk individuals to choose non-pharmacologic means of addressing the ABCS. The ABCS for HIV protocol promotes shared, informed decision-making. While this method of addressing risk factors is part of the management algorithm in lower risk participants, the change in the components making up the trial’s primary outcome may occur at a slower pace and not be appreciable over the 1-year evaluation period. Potentially, attaining therapeutic goals using behavioral changes has greater potential to significantly impact cardiovascular health, compared to use of pharmacologic means.

Limitations

There are several limitations that warrant discussion. First, the original ASCVD model was designed primarily for cross-sectional use.48 When adapted for longitudinal use, incorporation of hypertension treatment can yield paradoxical results. The longitudinal ASCVD model currently used in the CMS Million Hearts trial was developed to address this limitation,48 but the underlying equations for this model are not yet available. To address this challenge, we will conduct sensitivity analyses around hypertension treatment as a risk factor. We will also compare results from use of the pooled equations model with those from the longitudinal ASCVD risk model once we obtain the longitudinal equations. Importantly, we will separately assess impact on CVD risk factors, including blood pressure, LDL-C and smoking in addition to potential reduction in aspirin use.

Second, recent trial data have cast doubt on the comparative benefits versus harms for the use of low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of ASCVD events. Current recommendations suggest a more limited role for aspirin,5 raising the need for potential de-implementation.

Last, it will not be possible to determine with certainty which element of this multicomponent intervention improves outcomes the most. However, proposed process analyses may shed some light on particularly salient pathways.

Conclusions/implications of research

Primary prevention targeting specific modifiable risks for cardiovascular disease has the most impact in decreasing ASCVD morbidity and mortality. PWH are at elevated CVD risk despite effective use of ART. Our proposal is innovative in its focus on identifying effective implementation strategies for promoting the ABCS among PWH at appreciable risk. Findings have implications for addressing this emerging ASCVD epidemic among PWH.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge our participating sites:

Joseph P. Addabbo Health Center, Queens, NY

Morris Heights Health Center, Bronx, NY

Brownsville Multi-specialty Practice, Brooklyn, NY

Metropolitan Family Health Center and Jersey City Medical Center, Jersey City, NJ

Family Health Centers at NYU Langone – Sunset Terrace Health Center, Brooklyn, NY

Bluitt-Flowers Health Clinic, Dallas, TX

Amelia Court Clinic, Dallas, TX

URMC AIDS Center, Rochester, NY

Trillium Health, Rochester, NY

Supported by: NHLBI U01HL142107 and NCATS UL1 TR002001 and NCATS UL1 TR000043.

Abbreviations and acronyms:

- ABCS

aspirin-blood pressure control-cholesterol control-smoking cessation

- ACC

American College of Cardiology

- ADAP

AIDS Drug Assistance Program

- AHA

American Heart Association

- ARMS

Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- ASCVD

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- BMI

body mass index

- BRFSS

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CFIR

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- CME

continuing medical education

- CMS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- EHR

electronic health record

- GLMM

generalized linear mixed model

- HbA1c

hemoglobin A1C

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- IL

interleukin

- IRB

Institutional Research Board

- ITT

intent-to-treat

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LMM

liner mixed model

- MICE

multiple imputation using chained equations

- NLA

National Lipid Association

- PAM

Patient Activation Measure

- PWH

people living with HIV

- QuEST

Qualitative Evaluation for Systematic Translation

- RA

research assistants

- RE-AIM

Reach-Effectiveness-Adoption-Implementation-Maintenance

- SASH

Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- SES

socio-economic status

- SNS

Subjective Numeracy Scale

- URMC

University of Rochester Medical Center

Footnotes

Statement of conflict of interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interests with regard to this publication.

References

- 1.Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D: A: D): a multicohort collaboration. Lancet 2014;384 (9939):241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feinstein MJ, Hsue PY, Benjamin LA, et al. Characteristics, prevention, and management of cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;140(2):e98–e124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker JV, Duprez D. Biomarkers and HIV-associated cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010;5(6):511–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73(24):e285–e350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnett Donna K, Blumenthal Roger S, Albert Michelle A, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2019;0(140): e596–e646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Million hearts. NIH. , https://millionhearts.hhs.gov/about-million-hearts/index.html. [Published 2019. Accessed December 12, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson-Paul AM, Lichtenstein KA, Armon C, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk prediction in the HIV Outpatient Study. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63(11):1508–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clement ME, Park LP, Navar AM, et al. Statin utilization and recommendations among HIV-and HCV-infected veterans: a cohort study. Rev Infect Dis 2016;63(3):407–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly SG, Krueger KM, Grant JL, et al. Statin prescribing practices in the comprehensive care for HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;76(1):e26–e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suchindran S, Regan S, Meigs JB, et al. Aspirin use for primary and secondary prevention in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-infected and HIV-uninfected patients. Open Forum Infect Dis 2014;1(3), ofu076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shuter J, Salmo LN, Shuter AD, et al. Provider beliefs and practices relating to tobacco use in patients living with HIV/AIDS: a national survey. AIDS Behav 2012;16(2):288–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monroe AK, Chander G, Moore RD. Control of medical comorbidities in individuals with HIV. JAIDS 2011;58(5):458–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4(1):50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forman J, Heisler M, Damschroder LJ, et al. Development and application of the RE-AIM QuEST mixed methods framework for program evaluation. Prev Med Rep 2017;6:322–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, et al. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012;50(3):217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boaz A, Baeza J, Fraser A. Effective implementation of research into practice: an overview of systematic reviews of the health literature. BMC Res Notes 2011;4(1):212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. [Review] [111 refs][Update of Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000409]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;4, CD000409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;6, CD000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soumerai SB, Avorn J. Principles of educational outreach (“academic detailing”) to improve clinical decision making. JAMA 1990;263(4):549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinnersley P, Edwards A, Hood K, et al. Interventions before consultations for helping patients address their information needs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;3, CD004565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schedlbauer A, Davies P, Fahey T. Interventions to improve adherence to lipid lowering medication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;3(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yasmin F, Banu B, Zakir SM, et al. Positive influence of short message service and voice call interventions on adherence and health outcomes in case of chronic disease care: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2016;16:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher EB, Tang PY, Coufal MM, et al. Peer support. Chronic illness care. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, Cham; 2018. p. 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrer RA, Cohen GL. Reconceptualizing self-affirmation with the trigger and channel framework: lessons from the health domain. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 2019;23(3):285–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 2013;46(1):81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Genberg BL, Shangani S, Sabatino K, et al. Improving engagement in the HIV care cas-cade: a systematic review of interventions involving people living with HIV/AIDS as peers. AIDS Behav 2016;20(10):2452–2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 1999;89(9):1322–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karmali KN, Lloyd-Jones DM, Berendsen MA, et al. Drugs for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: an overview of systematic reviews. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1(3):341–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63(25 Pt B):2935–2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, et al. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ 2015;350, h2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Loudon K. PRECIS-2 helps researchers design more applicable RCTs while CONSORT Extension for Pragmatic Trials helps knowledge users decide whether to apply them. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;84:27–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hughes JP, Granston TS, Heagerty PJ. Current issues in the design and analysis of stepped wedge trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2015;45:55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2007;28(2):182–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mons U, Müezzinler A, Gellert C, et al. Impact of smoking and smoking cessation on cardiovascular events and mortality among older adults: meta-analysis of individual participant data from prospective cohort studies of the CHANCES consortium. BMJ 2015;h1551:350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system. , https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html. [Published 2017. Accessed December 26, 2019].

- 37.Topolski TD, LoGerfo J, Patrick DL, et al. The Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity (RAPA) among older adults. Prev Chronic Dis 2006;3(4):A118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paxton AE, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ, et al. Starting the conversation: performance of a brief dietary assessment and intervention tool for health professionals. Am J Prev Med 2011;40(1):67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barr PJ, Thompson R, Walsh T, et al. The psychometric properties of CollaboRATE: a fast and frugal patient-reported measure of the shared decision-making process. J Med Internet Res 2014;16(1):e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kripalani S, Risser J, Gatti ME, et al. Development and evaluation of the Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS) among low-literacy patients with chronic disease. Value Health 2009;12(1):118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barona A, Miller JA. Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanic Youth (SASH-Y): a preliminary report. Hisp J Behav Sci 1994;16(2):155–162. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, et al. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zimmerman GL, Olsen CG, Bosworth MF. A “stages of change” approach to helping patients change behavior. Am Fam Physician 2000;61(5):1409–1416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Smith DM, Ubel PA, et al. Validation of the Subjective Numeracy Scale: effects of low numeracy on comprehension of risk communications and utility elicitations. Med Decis Making 2007;27(5):663–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carroll JK, Farah S, Fortuna RJ, et al. Addressing medication costs during primary care visits: a before–after study of team-based training. Ann Intern Med 2019;170:S46–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holtrop JS, Rabin BA, Glasgow RE. Qualitative approaches to use of the RE-AIM framework: rationale and methods. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18(1):177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Creswell JW, Fetters MD, Ivankova NV. Designing a mixed methods study in primary care. Ann Fam Med 2004;2(1):7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lloyd-Jones DM, Huffman MD, Karmali KN, et al. Estimating longitudinal risks and benefits from cardiovascular preventive therapies among medicare patients: the Million Hearts Longitudinal ASCVD Risk Assessment Tool: a special report from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. Circulation 2017;135(13):e793–e813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]