Abstract

Preconditioning by brief ischemic episode induces tolerance to a subsequent lethal ischemic insult, and it has been suggested that reactive oxygen species are involved in this phenomenon. Thioredoxin 2 (Trx2), a small protein with redox‐regulating function, shows cytoprotective roles against oxidative stress. Here, we had focused on the role of Trx2 in ischemic preconditioning (IPC)‐mediated neuroprotection against oxidative stress followed by a subsequent lethal transient cerebral ischemia. Animals used in this study were randomly assigned to six groups; sham‐operated group, ischemia‐operated group, IPC plus (+) sham‐operated group, IPC + ischemia‐operated group, IPC + auranofin (a TrxR2 inhibitor) + sham‐operated group and IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated group. IPC was subjected to a 2 minutes of sublethal transient ischemia 1 day prior to a 5 minutes of lethal transient ischemia. A significant loss of neurons was found in the stratum pyramidale (SP) of the hippocampal CA1 region (CA1) in the ischemia‐operated‐group 5 days after ischemia‐reperfusion; in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group, pyramidal neurons in the SP were well protected. In the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group, Trx2 and TrxR2 immunoreactivities in the SP and its protein level in the CA1 were not significantly changed compared with those in the sham‐operated‐group after ischemia‐reperfusion. In addition, superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) expression, superoxide anion radical ( ) production, denatured cytochrome c expression and TUNEL‐positive cells in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group were similar to those in the sham‐operated‐group. Conversely, the treatment of auranofin to the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group significantly increased cell damage/death and abolished the IPC‐induced effect on Trx2 and TrxR2 expressions. Furthermore, the inhibition of Trx2R nearly cancelled the beneficial effects of IPC on SOD2 expression, production, denatured cytochrome c expression and TUNEL‐positive cells. In brief, this study shows that IPC conferred neuroprotection against ischemic injury by maintaining Trx2 and suggests that the maintenance or enhancement of Trx2 expression by IPC may be a legitimate strategy for therapeutic intervention of cerebral ischemia.

Keywords: delayed neuronal death, ischemia‐reperfusion, oxidative stress, superoxide anion, superoxide dismutase 2, thioredoxin 2

INTRODUCTION

Transient global cerebral ischemia occurs when cerebral blood supply is cut off and results in oxygen and glucose deprivation of brain tissues, which may cause irreversible cerebral damage 32. In humans, selective neuronal damage/death in the brain can occur frequently after cardiac arrest and/or cardiopulmonary bypass surgery, which is a worldwide devastating health problem 23, 53. Ischemic preconditioning (IPC) is an endogenous protective phenomenon by which a sublethal ischemic episode results in tolerance to later severe ischemic insult 11. Clinically, transient ischemic attacks before ischemic stroke induce tolerance by raising the threshold of tissue vulnerability 72, which is critical for neuroprotection. A 2‐minutes period of cerebral ischemia in the gerbil, which is a good animal model of transient global cerebral ischemia because the gerbils usually lack the posterior communicating arteries (incomplete Circle of Willis) and show a reliable reproducibility of ischemia‐reperfusion injury by the occlusion of both common carotid arteries 31, 34, produces no appreciable neuronal damage in the hippocampus 46. Five minutes or more periods of transient ischemia usually kill pyramidal neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region of the gerbil brain several days after ischemia; however, IPC (2‐min period of ischemia) protects against neuronal damage following longer periods of ischemia 46. Cerebral tolerance by IPC has been extensively studied but remains only partly understood. IPC is a complex phenomenon, involving diverse pathways and regulatory mechanisms.

Oxidative stress is caused by dramatically increased intracellular concentrations of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and has been associated with neuronal damage/death in global cerebral ischemia 30, 49, 76. After an ischemic episode, oxidative stress caused by the disruption of redox balance and the overproduction of ROS can attack macromolecules such as lipids, DNA and proteins and trigger redox state‐sensitive pro‐death signaling pathways, ultimately leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal death 5, 39, 77. Therefore, antioxidant therapy for ischemia‐reperfusion induced damage attracts intense interest.

Thioredoxin (Trx) is a small ubiquitous protein with pleiotropic biological functions, including cellular defense mechanisms against oxidative stress 40. It has a redox‐active disulfide/dithiol function within conserved catalytic site (Cys‐Gly‐Pro‐Cys) and participates in redox reactions through the reversible oxidation of cysteine pair while reducing disulfide bridges of various proteins 21, 22. Oxidized Trx is reduced to dithiol form by a Trx reductase (TrxR) with the use of electrons from NADPH (so‐called Trx system). Because of their unique capacity to quench singlet oxygen and scavenge hydroxyl radicals 9, Trx is considered to be crucial antioxidant protein. In animal brains, Trx is induced during ischemia‐reperfusion and appears to play an important role not only in scavenging ROS, which are implicated in the pathogenesis of cerebral infarction, but also in signal transduction during ischemia 5, 65. Among Trx subtypes, Trx1 is a cytosolic form, which is released from various types of cells, maintains redox environment as one of important enzymatic antioxidants 40, and Trx2, which is localized in the mitochondria, is more resistant to oxidation than cytosolic Trx1 60 and shows to play essential roles in cell survival and mitochondria‐mediated apoptosis 8, 66. In addition, it has been suggested that an enhanced expression of Trx2 system by hypoxia preconditioning is related with tolerance to hypoxia‐ischemia in the rat brain 61. However, the role of Trx2 in the IPC has not been fully investigated.

Various possible explanations exist for the protective effect of IPC against brain ischemia. Although Trx2 is known to be induced in response to various forms of oxidative stress, including ischemia‐reperfusion injury, the specific role of this protein in the IPC have not been fully investigated. In this study, we hypothesized that IPC‐mediated Trx2 expression would represent an important defense against oxidative stress and apoptosis in the hippocampal CA1 region after global cerebral ischemia. Thus, the contribution of Trx2 to IPC‐induced neuroprotection against oxidative stress and apoptosis followed by ischemia‐reperfusion was examined in the present study. Here, therefore, we compared Trx2 immunoreactivity and its protein level, which may be related with neuronal death in the hippocampal CA1 region, between the control and IPC‐induced gerbil brains followed by 5 minutes of transient cerebral ischemia. Furthermore, to examine the contribution of Trx2 to IPC‐induced neuroprotection, we used auranofin (a gold‐based pharmaceutical for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis), which has been identified as an effective inhibitor of TrxR2 in in vitro and in vivo studies 56, 63.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals

Male Mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) obtained from the Experimental Animal Center, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, South Korea. Gerbils were used at 6 months (B.W., 65–75 g) of age. The animals were housed in a conventional state under adequate temperature (23°C) and humidity (60%) control with a 12‐h light/12‐h dark cycle, and provided with free access to water and food. The procedures for animal handling and care adhered to guidelines that are in compliance with the current international laws and policies (Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, The National Academies Press, 8th Ed., 2011) and they were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Kangwon University. All of the experiments were conducted to minimize the number of animals used and the suffering caused by the procedures used in the present study.

Animal groups

The animals were divided into six groups (n = 14 at each point in time in each group): (i) sham‐operated‐group was exposed the bilateral common carotid arteries and no ischemia was given (sham‐operation); (ii) ischemia‐operated‐group was given a 5 min of transient cerebral ischemia; (iii) IPC plus sham‐operated‐group (IPC + sham‐operated‐group) was subjected to a 2 min sublethal transient ischemia prior to sham‐operation; (iv) IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group was subjected to a 2 minutes of sublethal ischemia 1 day prior to a 5 min of transient ischemia, (v) IPC + auranofin + sham‐operated‐group was given IPC 1 day prior to sham‐operation and treated with auranofin (a thioredoxin reductase 2 (TrxR2) inhibitor) 1 h prior to sham‐operation and (vi) IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐group was given IPC 1 day prior to a 5 minutes of transient ischemia and treated with auranofin 1 h prior to a 5 minutes of transient ischemia. The IPC paradigm has been proven to be very effective at protecting neurons against ischemic damage in this ischemic model. The animals in all groups were given recovery times of 2 days and 5 days, because pyramidal neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region do not die until 3 days and begin to die 4 days after ischemia‐reperfusion 46.

Treatment of auranofin

To examine the contribution of Trx2 to IPC‐induced neuroprotection, auranofin (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), a TrxR2 inhibitor, was dissolved in corn oil at a concentration of 10 mM, and the same dose of corn oil was used as the control. The needle of Alzet brain infusion kit (Durect Co., Cupertino, CA, USA) was implanted into the lateral ventricle to inject the control or auranofin according to stereotaxic coordination. One hour before ischemic insult, the animals were administered vehicle or auranofin using Alzet brain infusion kit (10 μL, intraventricularlly, Alzet). The dose of auranofin used in this study was selected according to the result of a previous study 63.

Induction of transient cerebral ischemia

The animals were anesthetized with a mixture of 2.5% isoflurane in 33% oxygen and 67% nitrous oxide. A midline ventral incision was then made in the neck, and bilateral common carotid arteries were isolated, freed of nerve fibers, and occluded using non‐traumatic aneurysm clips. The complete interruption of blood flow was confirmed by observing the central artery in retinae using an ophthalmoscope (HEINE K180®, Heine Optotechnik, Herrsching, Germany). After 5 minutes of occlusion, the aneurysm clips were removed from the common carotid arteries. The restoration of blood flow (reperfusion) was observed directly using the ophthalmoscope. Body (rectal) temperature was maintained under free‐regulating or normothermic (37 ± 0.5°C) conditions with a rectal temperature probe (TR‐100; Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA, USA) and a thermometric blanket before, during and after the surgery until the animals completely recovered from anesthesia. Thereafter, animals were kept in a thermal incubator (temperature, 23°C; humidity, 60%) (Mirae Medical Industry, Seoul, South Korea) to maintain the body temperature until the animals were euthanized. The sham groups were subjected to the same surgical procedures except that the common carotid arteries were not occluded.

Tissue processing for histology

All of the animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium at the designated times and perfused transcardially with 0.1 M phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate‐buffer (PB, pH 7.4). The brains were removed and postfixed in the same fixative for 6 h. The brain tissues were cryoprotected by infiltration with 30% sucrose overnight. Thereafter, frozen tissues were serially sectioned on a cryostat (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) into 30‐μm coronal sections and then collected into six‐well plates containing PBS.

Cresyl violet staining

To examine neuronal damage in the CA1 region (n = 7 at each point in time in each group) using CV staining, the sections were mounted on gelatin‐coated microscopy slides. Cresyl violet (CV) acetate (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved at 1.0% (w/v) in distilled water, and glacial acetic acid was added to this solution. The sections were stained and dehydrated by immersing in serial ethanol baths, and they were then mounted with Canada balsam (Kanto chemical, Tokyo, Japan).

NeuN immunohistochemistry

To examine neuronal damage in the CA1 region (n = 7 at each point in time in each group) after cerebral ischemia using anti‐neuronal nuclei (NeuN, a marker for neurons), the sections were sequentially treated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in PBS for 30 minutes and 10% normal goat serum in 0.05 M PBS for 30 minutes. The sections were next incubated with diluted mouse anti‐NeuN (1:1000, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C. Thereafter the tissues were exposed to biotinylated goat anti‐mouse IgG (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA, USA) and streptavidin peroxidase complex (1:200, Vector). And they were visualized by staining with 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride in 0.1 M Tris‐HCl buffer (pH 7.2) and mounted on gelatin‐coated slides. After dehydration, the sections were mounted with Canada balsam (Kanto chemical).

Fluoro‐Jade B histofluorescence staining

To examine neuronal death in the CA1 region at each point in time after transient ischemia using Fluoro‐Jade B (F‐J B) (a high affinity fluorescent marker for the localization of neuronal degeneration) histofluorescence 3, the sections were first immersed in a solution containing 1% sodium hydroxide in 80% alcohol, and followed in 70% alcohol. These sections were then transferred to a solution of 0.06% potassium permanganate, and transferred to a 0.0004% F‐J B (Histochem, Jefferson, AR, USA) staining solution. After washing, the sections were placed on a slide warmer (approximately 50°C), and then examined using an epifluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) with blue (450–490 nm) excitation light and a barrier filter. With this method neurons that undergo degeneration brightly fluoresce in comparison to the background 58.

Immunohistochemistry for Trx2, TrxR2, superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) and cytochrome c

To examine changes of antioxidants in the CA1 region (n = 7 at each point in time in each group) after ischemia‐reperfusion, we carried out immunohistochemical staining for Trx2, SOD2 and cytochrome c according to our previous method 24, 73. The sections were sequentially treated with 0.3% H2O2 in PBS for 30 minutes and 10% normal goat serum in 0.05 M PBS for 30 minutes. These sections were then incubated with rabbit anti‐Trx2 (diluted 1:500, Ab Frontier, Seoul, South Korea), rabbit anti‐TrxR2 (diluted 1:500, Ab Frontier), goat anti‐SOD2 (diluted 1:1000, Calbiochem, Novabiochem, Boston, MA, USA), mouse anti‐cytochrome c (denatured form, 1:100, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) overnight at 4°C and subsequently exposed and biotinylated goat anti‐rabbit, mouse IgG and rabbit anti‐goat IgG (Vector) for secondary antibody and streptavidin peroxidase complex (diluted 1:200, Vector). These sections were then visualized according to the above mentioned‐method (see the NeuN immunohistochemistry). To establish the specificity of the immunostaining, a negative control test was carried out with preimmune serum instead of primary antibody. The negative control resulted in the absence of immunoreactivity in any structures.

Double immunofluorescence staining

To confirm the cell type containing Trx2 and SOD2 immunoreactivity, the sections 5 days (n = 7) after the ischemic surgery were processed by double immunofluorescence staining according to our previous method 24. Double immunofluorescence staining was performed using rabbit anti‐Trx2 (diluted 1:100, Ab Frontier) or goat anti‐SOD2 (diluted 1:1000, Calbiochem)/mouse anti‐glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (diluted 1:200, Chemicon International) for astrocytes or mouse anti‐ionized calcium‐binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba‐1, diluted 1:200, Wako, Osaka, Japan) for microglia. The sections were incubated in the mixture of antisera overnight at room temperature. After washing 3 times for 10 minutes with PBS, these sections were then incubated in a mixture of both FITC‐conjugated goat anti‐rabbit IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. West Grove, PA, USA) or FITC‐conjugated rabbit anti‐goat IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.) and Cy3‐conjugated horse anti‐mouse IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.) for 2 h at room temperature. The immunoreactions were observed under the confocal MS (LSM510 META NLO, Carl Zeiss).

Western blot analysis for Trx2, TrxR2, SOD2 and cytochrome c

To examine changes in the protein levels of Trx2, TrxR2, SOD2 and cytochrome c (denatured form) in the ischemic CA1 region, the animals (n = 7 at each point in time) were used for western blot analysis at sham, 2 days and 5 days after the ischemic surgery according to our previous method 35. After sacrificing the animals and removing the hippocampus, it was serially and transversely cut into a thickness of 400 µm on a vibratome (Leica), and the hippocampal CA1 region was then dissected with a surgical blade. The tissues were homogenized in 50 mM PBS (pH 7.4) containing EGTA (pH 8.0), 0.2% NP‐40, 10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 15 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 100 mM β‐glycerophosphate, 50 mM NaF, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM sodium orthvanadate, 1 mM PMSF and 1 mM DTT. After centrifugation, the protein level in the supernatants was determined using a Micro BCA protein assay kit with bovine serum albumin as a standard (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL, USA). Aliquots containing 50 µg of total protein were boiled in loading buffer containing 250 mM Tris (pH 6.8), 10 mM DTT, 10% SDS, 0.5% bromophenol blue and 50% glycerol. The aliquots were then loaded onto a suitable polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the gels were transferred to nitrocellulose transfer membranes (Pall Crop, East Hills, NY, USA). To incubate antibodies, the same striped nitrocellulose membranes were used. To reduce background staining, the membranes were incubated with 5% non‐fat dry milk in TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 for 45 minutes, followed by incubation with rabbit anti‐Trx2 (diluted 1:1000, Chemicon International), rabbit anti‐TrxR2 (1:1000; Ab Frontier), goat anti‐SOD2 (diluted 1:1000, Calbiochem), mouse anti‐cytochrome c (denatured form, 1:1000, BD Biosciences) overnight at 4°C and subsequently exposed to peroxidase‐conjugated horse anti‐Goat IgG, goat anti‐rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.) and an ECL kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.).

Western blot analysis for the redox state of Trx2

The redox state of Trx2 in response to transient cerebral ischemia was determined using the redox western blot method as previously, with minor modifications 16, 18. Briefly, brain tissues were homogenized in a lysis buffer (6 M Guanidine HCl; 50 mM Tris‐HCl pH 8.3, 3 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X‐100, 10 μg/mL aprotonin and 10 μg/mL leupeptin) containing 50 mM iodoacetic acid (IAA) and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Excess IAA was removed by Sephadex chromatography (MicroSpin G‐25 columns, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Total protein (100 μg per sample) was resolved by 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Blots were incubated with an anti‐Trx2 (diluted 1:1000, Chemicon International) or anti‐actin (1:2000; Sigma‐Aldrich) antibodies overnight at 4°C followed by secondary incubation with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated antibodies (1:2000, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.) Bound antibodies were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech.) on X‐ray film.

TUNEL staining

For TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl dUTP nick‐end labeling) staining, frozen tissues of the CA1 region (n = 7 at each point in time in each group), which were sectioned on a cryostat (Leica) into 8‐μm coronal sections, were mounted on gelatin‐coated slides and air‐dried for 5 minutes before TUNEL staining and these sections were washed in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) for 30 minutes before being incubated in blocking solution (3% H2O2 in 0.01 M PBS) at room temperature for 20 minutes. The sections were then washed in PBS for 5 minutes and treated with permeabilization solution (0.1% Triton X‐100 in 0.1% sodium citrate) at 4°C for 2 minutes. Next, the sections were washed three times with PBS (10 minutes per wash), and then incubated in TUNEL reaction mixture according to kit instructions (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) at 37°C for 1 h in a humidified chamber. The TUNEL reaction mixture was prepared with a 1:2 dilution of the enzyme solution, which was mixed with the label solution just before use. The sections were washed three times with PBS (10 minutes per wash) before being incubated in converter‐POD (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) at 37°C for 30 minutes in a humidified chamber and they were washed and treated with DAB‐substrate solution for 2 minutes. After washing the sections three times in PBS (5 minutes per wash), the sections were dehydrated and coverslipped with Canada Balsam (Kanto chemical), and slides coded for subsequent blind counting.

Dihydroethidium fluorescence staining

The gerbil brains were processed for analysis of oxidative stress at 2 and 5 days after ischemia‐reperfusion (n = 7 at each point in time). The oxidative fluorescent dyedihydroethidium (DHE; Sigma‐Aldrich) was used to evaluate in situ production of superoxide anion. Histological detection of superoxide anion radical was performed as described previously 64. In brief, sections were mounted on a glass slide, and then equilibrated under indentical conditions for 30 minutes at 37°C in Krebs‐HEPES buffer (130 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.24 mM MgCl2, 8.3 mM HEPES, 11 mM glucose, pH 7.4). Fresh buffer containing DHE (10 μmol/L) was applied topically on each tissue section, coverslipped, and incubated for 2 h in a light‐protected humidified chamber at 37°C. DHE was oxidized on reaction with superoxide to ethidium, which could bind to DNA in the nucleus and fluoresced red. For detection of ethidium, slides were examined with an epifluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss) using an excitation wavelength of 520–540 nm. The fluorescence intensity of brain sections was analyzed at the center of the CA1 region in the stratum pyramidale (SP); mean values were recorded.

Data analysis

All measurements were performed to ensure objectivity in blind conditions, by three observers for each experiment, carrying out the measures of control and experimental samples under the same conditions. The studied tissue sections were selected with 120 µm interval according to anatomical landmarks corresponding to AP −1.4 to −1.8 mm of the gerbil brain atlas, and cell counts were obtained by averaging the counts from 20 sections taken from each animal. All NeuN‐, F‐J B‐, TUNEL‐positive structures were taken from three layers (strata oriens, pyramidale and radiatum in the hippocampus proper) through an AxioM1 light microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a digital camera (Axiocam, Carl Zeiss) connected to a PC monitor. The mean number of NeuN+, F‐J B+ and TUNEL+ cells was counted in a 200 × 200 µm square applied approximately at the center of the CA1 region. Cell counts were obtained by averaging the total cell numbers from each animal per group. Ten sections per animal were selected to quantitatively analyze Trx2, TrxR2, SOD2 and cytochrome c immunoreactivity and superoxide anion fluorescence intensity in the CA1 region. The staining intensity of Trx2‐, TrxR2‐, SOD2‐, cytochrome c‐immunoreactive structures and superoxide anion radical was evaluated on the basis of an optical density (OD), which was obtained after the transformation of the mean gray level using the formula: OD = log (256/mean gray level). The OD of background was taken from areas adjacent to the measured area. After the background density was subtracted, a ratio of the OD of an image file was calibrated in Adobe Photoshop 8.0 and then analyzed as a percent, with sham‐operated‐group designated as 100% in NIH Image 1.59.

The results of western blot analyses were scanned and densitometric analyses for the quantification of the bands was done using Scion Image software (Scion Corp., Frederick, MD, USA). The expression rates of the target proteins were normalized through the corresponding expression rates of β‐actin.

Statistical analysis

The estimation of sample size was dependent on the standard deviation as in a published study by Ozkan et al 50. Sample size was at least seven gerbils per group with an alpha error of 0.05 and a power of >80%, and the sample size was calculated with power calculator (UCLA Department of Statistics, http://www.stat.ubc.ca/~rollin/stats/ssize). All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. A multiple‐sample comparison was applied to test the differences between groups (ANOVA and the Tukey multiple range test as post hoc test using the criterion of the least significant differences). Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

IPC‐mediated neuroprotection against transient ischemia

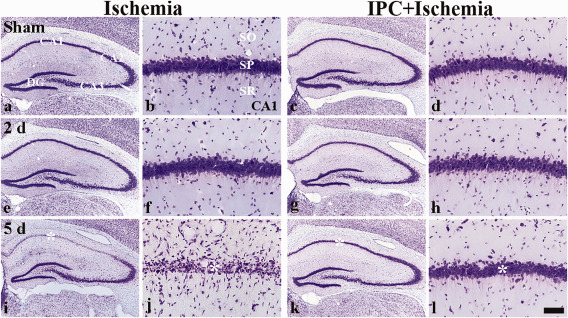

CV‐positive (CV+) cells

We examined whether IPC was associated with neuronal cell survival in the CA1 region after ischemia/reperfusion (Figure 1). In the sham‐operated‐group, CV+ cells were easily detected in all subregions of the hippocampus, and CV+ cells in the SP were relatively large, pyramid‐like or round in shape (Figure 1A,B). In the ischemia‐operated‐group, the morphology of CV+ cells was not changed at 2 days post‐ischemia (Figure 1E,F). However, at 5 days post‐ischemia, CV+ cells was significantly decreased in the SP of the CA1 region, not the CA2/3 region, compared with that of the sham‐operated‐group (Figure 1I,J): in this group, CV+ cells in the SP were shrunken and contained dark and polygonal nuclei (Figure 1J).

Figure 1.

Effect of IPC on CV+ cells in the CA1 region of the ischemia‐operated‐ (left two columns) and IPC + ischemia‐operated‐ (right two columns) groups at sham (A–D), 2 (E–H) and 5 days (I–L) post‐ischemia. In the ischemia‐operated‐group, only a few CV+ cells (asterisk) are shown in the stratum pyramidale (SP) at 5 days post‐ischemia, whereas abundant CV+ cells (asterisk) are observed in the SP of the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group. CA1; cornus ammonis 1, DG; dentate gyrus, SO; stratum oriens, SR; stratum radiatum. Scale bar = 800 (A, C, E, G, I, K) and 50 (B, D, F, H, J, L) μm.

In the IPC + sham‐operated‐group, the distribution pattern of CV+ cells in the hippocampus was very similar to that in the sham‐operated‐group (Figure 1C,D). In the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group, the distribution pattern of CV+ cells in the SP of the CA1 region was also similar to that in the IPC + sham‐operated‐group (Figure 1G,H,K,L).

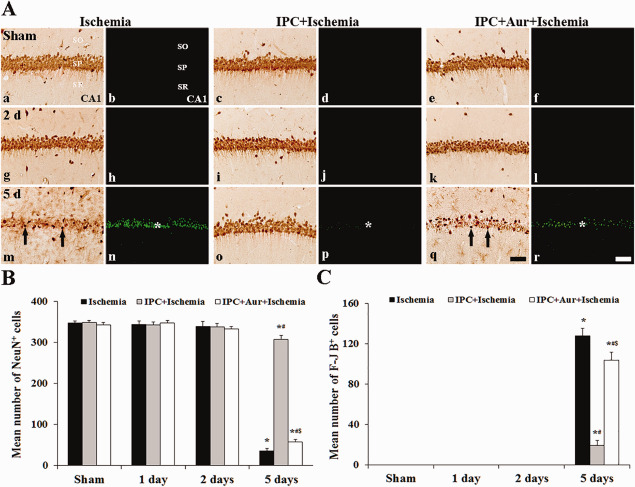

NeuN+ and F‐J B+ cells

IPC‐mediated neuroprotection in the hippocampus was also assessed with NeuN immunohistochemistry and F‐J B histofluorescence staining (Figure 2). Pyramidal neurons in the SP were well stained with NeuN and easily observed in the sham‐operated‐group (Figure 2A[a]), and, in this group, no F‐J B+ neurons were found in the CA1 region (Figure 2A[b]). In the ischemia‐operated‐groups, we did not find significant change in numbers of NeuN+ and F‐J B+ neurons in the CA1‐3 regions at 2 days post‐ischemia (Figure 2A[g,h]); however, 5 days after post‐ischemia, a significant loss of NeuN+ neurons and a significant increase of F‐J B+ cells was observed in the SP of the CA1 region, not in the CA2/3 region (Figure 2A[m,n]): in this group, the mean percentage of NeuN+ neurons in the SP was about 7.9% of that in the ischemia‐sham‐operated‐group (see Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Effect of IPC on NeuN+ and F‐J B+ cells in the CA1 region of the ischemia‐operated‐ (left two columns), IPC + ischemia‐operated‐ (middle two columns) and IPC + aur + ischemia‐operated‐(right two columns) groups at sham (a–f), 2 (g–l) and 5 days (m–r) post‐ischemia. A. In the ischemia‐operated‐group, a few NeuN+ cells (arrows) are shown in the stratum pyramidale (SP) at 5 days post‐ischemia; however, the distribution pattern of NeuN+ in the SP of the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group is similar to that in the sham‐operated‐group. In the ischemia‐operated‐group, many F‐J B+ cells (asterisk) are detected in the SP at 5 days post‐ischemia; however, F‐J B+ cells (asterisk) are rarely detected in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group at 5 days post‐ischemia. In the IPC + aur + ischemia‐operated‐group, a few NeuN+ neurons (arrows) and many F‐J B+ cells (asterisk) are detected in the stratum pyramidale at 5 days post‐ischemia. CA1; cornus ammonis 1, SO, stratum oriens; SR, stratum radiatum. Scale bar = 50 μm. B and C. Quantitative analyses of NeuN+ (B) and F‐J B+ (C) cells in all the groups. The bars indicate the means ± SEM (*P < 0.05 vs. sham‐operated‐group; # P < 0.05 vs. ischemia‐operated‐group; $ P < 0.05 vs. IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group).

In the IPC + sham‐operated‐group, distribution patterns of NeuN+ and F‐J B+ neurons in the CA1 region were similar to those in the ischemia‐sham‐operated‐group (Figure 2A[c,d]). In the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group, distribution patterns of NeuN+ and F‐J B+ cells in the SP were not significantly changed at 2 days post‐ischemia compared with that in the IPC + sham‐operated‐group (Figure 2A[i,j]). At 5 days post‐ischemia, many NeuN+ cells were found in the SP of the CA1 region (Figure 2A[o]): 92.1% of CA1 pyramidal neurons were stained with NeuN compared to that in the IPC + sham‐operated‐group (Figure 2B). In addition, at this point in time, few F‐J B+ cells were detected in the SP (Figure 2A[p]): the mean percentage of the F‐J B+ cells in the SP was 12.6% of the ischemia‐operated‐group at 5 days post‐ischemia (Figure 2C).

Abolishment of IPC‐mediated neuroprotection by TrxR2 inhibition

NeuN+ and F‐J B+ cells

We examined effects of TrxR2 inhibition on IPC‐mediated neuroprotection in the hippocampal CA1 region after 5 minutes of transient ischemia by NeuN immunohistochemistry, F‐J B histofluorescence staining (Figure 2). In the IPC + auranofin + sham‐operated‐group, NeuN+ neurons in the SP were similar to those in the sham‐operated‐group (Figure 2A[e]). In the IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐groups, no change in NeuN+ neurons was found 2 days after ischemia‐reperfusion (Figure 2A[k],B); however, at 5 days post‐ischemia, NeuN+ neurons were markedly decreased (Figure 2A[q],B). Conversely, F‐J B+ cells in the IPC + auranofin + sham‐operated‐groups were not detected in the CA1 region at sham and 2 days post‐ischemia (Figure 2A[f,l],C); however, many F‐J B+ cells were found in the SP at 5 days post‐ischemia (Figure 2A[r],C).

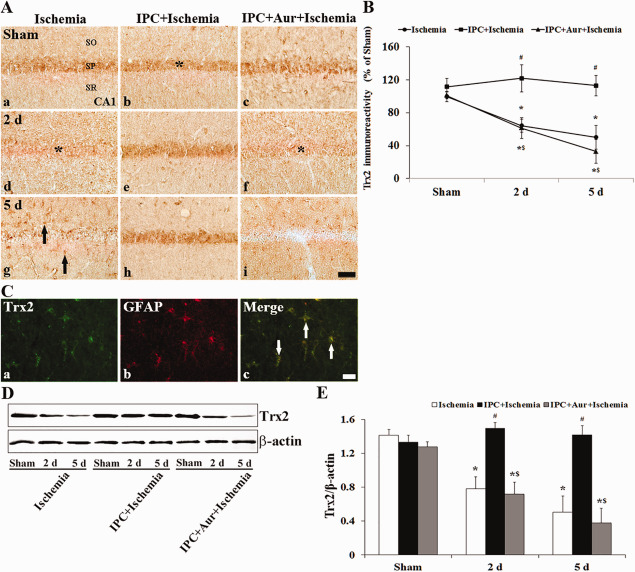

Relationship between IPC‐mediated Trx2 and TrxR2 expressions

Trx2 immunoreactivity and its protein level

In the sham‐operated‐group, Trx2 immunoreactivity was easily detected in CA1 pyramidal neurons (Figure 3A[a]). At 1 day post‐ischemia, Trx2 immunoreactivity was slightly decreased in many CA1 pyramidal neurons and significantly decreased 2 days after ischemia‐reperfusion compared with that in the sham‐operated‐group (Figure 3A[d]). At 5 days post‐ischemia in this group, Trx2 immunoreactivity in the SP was hardly detected; however, Trx2 immunoreactivity was shown in non‐pyramidal cells (glia‐like cells) in the strata oriens and radiatum (Figure 3A[g]): based on double immunofluorescence staining, Trx2+ cells were identified as GFAP+ astrocytes (Figure 3C). In the IPC + sham‐operated‐group, Trx2 immunoreactivity in the SP of the CA1 region was slightly increased compared with that in the sham‐operated‐group (Figure 3A[b],B). In the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐groups, Trx2 immunoreactivity in the SP was increased at 2 day post‐ischemia (Figure 3A[e],B), and, thereafter, the immunoreactivity was maintained until 5 days post‐ischemia (Figure 3A[h],B). In the IPC + auranofin + sham‐operated‐group, Trx2 immunoreactivity in the SP of the CA1 region was similar to that in the sham‐operated‐group (Figure 3A[c]). In the IPC + Aur + ischemia‐operated‐group, Trx2 immunoreactivity was intensely decreased in the SP 2 days post‐ischemia, and thereafter, the immunoreactivity in the SP was hardly detected at 5 days post‐ischemia (Figure 3A[f,i],B).

Figure 3.

A. Effect of IPC on Trx2 immunoreactivity in the CA1 region of the ischemia‐operated‐ (left column), IPC + ischemia‐operated‐ (middle column) and IPC + aur + ischemia‐operated‐ (right column) groups at sham (a–c), 2 (d–f) and 5 days (g–i) post‐ischemia. In the ischemia‐operated‐ and IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐groups, Trx2 immunoreactivity is apparently decreased in the stratum pyramidale (SP, asterisks) at 2 and 5 days post‐ischemia. In the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group, Trx2 immunoreactivity in the SP is increased compared with that in the sham‐operated‐group. CA1, cornus ammonis 1; SO, stratum oriens; SR, stratum radiatum. Scale bar = 50 μm. B. Quantitative analysis of Trx2 immunoreactivity in the SP of all the groups. A ratio of the ROD was calibrated as %, with the sham‐operated‐group designated as 100%. The bars indicate the means ± SEM (* P < 0.05 vs. sham‐operated‐group; # P < 0.05 vs. ischemia‐operated‐group; $ P < 0.05 vs. IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group). C. Double immunofluorescence staining for Trx2 (green, a), GFAP (red, b) and merged images (c) at 5 days post‐ischemia. Trx2+ cells in the SO and SR are colocalized with GFAP+ astroglial cells (white arrows). Scale bar = 20 μm. D and E. Western blot analysis of Trx2 protein in the hippocampus derived from all the groups. Protein expression is normalized to β‐actin. The bars indicate the means ± SEM (* P < 0.05 vs. sham‐operated‐group; # P < 0.05 vs. ischemia‐operated‐group; $ P < 0.05 vs. IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group).

We examined changes in Trx2 protein level in the CA1 of all experimental groups. The change patterns of Trx2 protein level were generally similar to the immunohistochemical changes. The protein level of Trx2 in the IPC + sham‐operated‐group was similar to those in the sham‐operated‐group. In the ischemia‐operated‐groups, protein level of Trx2 was considerably decreased in the ischemic CA1; however, in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐groups, their level was not changed compared with that in the sham‐operated‐group (Figure 3D,E). In addition, the change pattern of Trx2 protein levels in the IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐groups was similar to that in the ischemia‐operated‐groups (Figure 3D,E). Levels of Trx2 protein were down‐regulated in time‐dependent manner following ischemia‐reperfusion: Trx2 level was significantly decreased 5 days after ischemia‐reperfusion (Figure 3D,E).

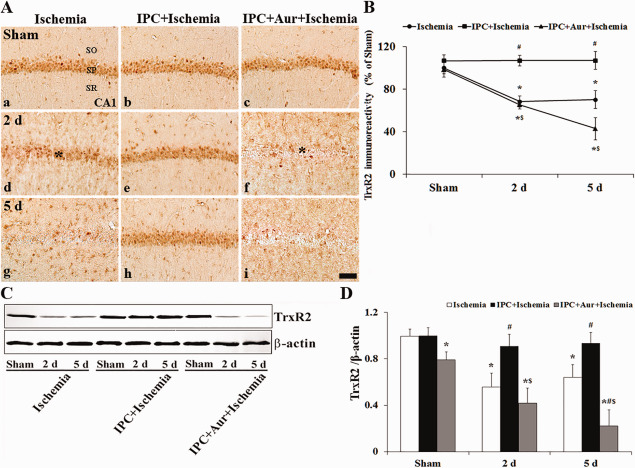

TrxR2 immunoreactivity and its protein level

In the sham‐operated‐group, moderate TrxR2 immunoreactivity was found in the SP of the CA1 region (Figure 4A[a]). Following ischemia, TrxR2 immunoreactivity was significantly decreased 2 days after ischemia‐reperfusion compared with that in the sham‐operated‐group (Figure 4A[d]). At 5 days post‐ischemia in this group, TrxR2 immunoreactivity in the SP was hardly detected; however, TrxR2 immunoreactivity was shown in non‐pyramidal cells (glia‐like cells) in the strata oriens and radiatum (Figure 4A[g]): TrxR2+ cells were identified as GFAP+ astrocytes by double immunofluorescence staining (data not shown). In the IPC + sham‐operated‐group, TrxR2 immunoreactivity in CA1 pyramidal neurons was similar to that in the sham‐operated‐group (Figure 4A[b],B). In the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐groups, TrxR2 immunoreactivity was not significantly changed in the SP until 5 days post‐ischemia (Figure 4A[e,h],B). In the IPC + auranofin + sham‐operated‐group, TrxR2 immunoreactivity in the SP of the CA1 region was similar to that in the sham‐operated‐group (Figure 4A[c],B). Auranofin treatment to the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group showed a distinct decrease of TrxR2 immunoreactivity in the SP 2 days after ischemia‐reperfusion (Figure 4A[f],B). At 5 days post‐ischemia, the TrxR2 immunoreactivity in the SP very low (Figure 4A[i],B).

Figure 4.

A. Effect of IPC on TrxR2 immunoreactivity in the CA1 region of the ischemia‐operated‐ (left column), IPC + ischemia‐operated‐ (middle column) and IPC + aur + ischemia‐operated‐ (right column) groups at sham (a–c), 2 (d–f) and 5 days (g–i) post‐ischemia. In the ischemia‐operated‐ and IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐groups, TrxR2 immunoreactivity is apparently decreased in the stratum pyramidale (SP, asterisks) at 2 and 5 days post‐ischemia. In the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group, TrxR2 immunoreactivity in the SP is maintained. CA1, cornus ammonis 1; SO, stratum oriens; SR, stratum radiatum. Scale bar = 50 μm. B. Quantitative analysis of TrxR2 immunoreactivity in the SP of all the groups. A ratio of the ROD was calibrated as %, with the sham‐operated‐group designated as 100%. The bars indicate the means ± SEM (* P < 0.05 vs. sham‐operated‐group; # P < 0.05 vs. ischemia‐operated‐group; $ P < 0.05 vs. IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group). C and D. Western blot analysis of TrxR2 protein in the hippocampus derived from all the groups. Protein expression is normalized to β‐actin. The bars indicate the means ± SEM (* P < 0.05 vs. sham‐operated‐group; # P < 0.05 vs. ischemia‐operated‐group; $ P < 0.05 vs. IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group).

Western blot was used to assess the expression of TrxR2 protein in the CA1 region at different times after the reperfusion with or without IPC (Figure 4C,D). Moderate TrxR2 protein level was detected in the sham‐operated‐group, significantly decreased at 2 days post‐ischemia and much more decreased at 5 days post‐ischemia (Figure 4C,D). In the IPC + sham‐operated‐group, TrxR2 protein level was similar to that in the sham‐operated‐group, and, in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group, TrxR2 protein level was not significantly changed compared with that in the IPC + sham‐operated‐group (Figure 4C,D). In addition, the change pattern of TrxR2 protein level in the IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐group was similar to that in the ischemia‐operated‐group (Figure 4C,D); the level was down‐regulated in a time‐dependent manner following ischemia‐reperfusion and significantly decreased 5 days after ischemia‐reperfusion (Figure 4C,D).

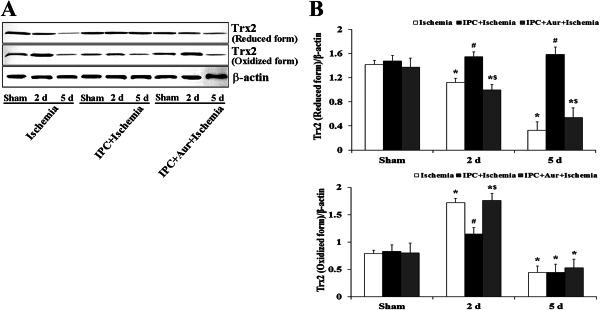

Redox state of Trx2

Redox western blot was used to assess the redox state of Trx2 protein in the CA1 region at different times after the reperfusion with or without IPC (Figure 5). The level of reduced Trx2 protein was down‐regulated in a time‐dependent manner following ischemia‐reperfusion: the reduced Trx2 level was significantly decreased 5 days after ischemia‐reperfusion. In the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐groups, the level of reduced Trx2 protein was not significantly changed compared with that in the sham‐operated‐group. However, the change pattern of reduced Trx2 protein levels in the IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐groups was similar to that in the ischemia‐operated‐groups (Figure 5A,B). Conversely, the level of oxidized Trx2 protein was significantly increased at 2 days post‐ischemia, and the protein level was again decreased at 5 days post‐ischemia. In the IPC + sham‐operated‐group, oxidized Trx2 protein level was not significantly changed compared with that in the sham‐operated‐group. In the IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐group, the change pattern of oxidized Trx2 protein levels was similar to that in the ischemia‐operated‐group (Figure 5A,B).

Figure 5.

Effect of IPC on redox states of Trx2 in the hippocampus of the sham‐operated‐, ischemia‐operated‐, IPC + ischemia‐operated‐ and IPC + aur + ischemia‐operated‐groups at sham, 2 and 5 days post‐ischemia. A. Western blot analysis of redox states of Trx2 in the hippocampus derived from all the groups. B. Quantitative analysis of redox states of Trx2 in the hippocampus from all the groups. Protein expression is normalized to β‐actin. The bars indicate the means ± SEM (* P < 0.05 vs. sham‐operated‐group; # P < 0.05 vs. ischemia‐operated‐group; $ P < 0.05 vs. IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group).

Attenuation of ischemia‐induced oxidative stress by IPC‐mediated increase of Trx2

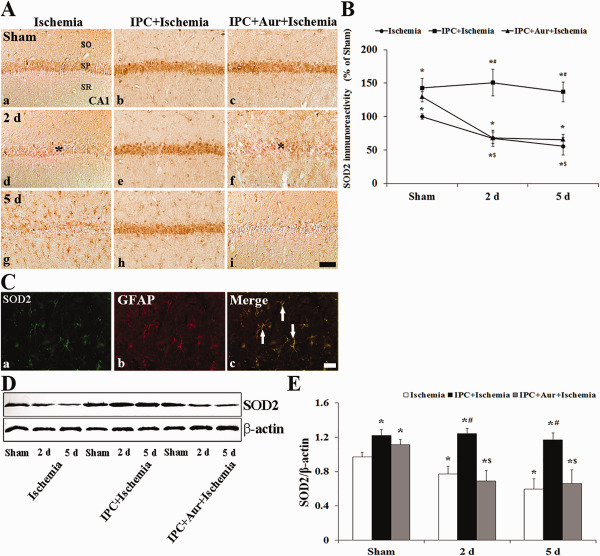

SOD2 immunoreactivity and its protein level

In the sham‐operated‐group, moderate SOD2 immunoreactivity was detected in the SP of the CA1 region (Figure 6A[a]). In the ischemia‐operated‐group, SOD2 immunoreactivity was significantly decreased in the SP 2 days after ischemia‐reperfusion (Figure 6A[d]). At 5 days post‐ischemia, the pattern of SOD2 immunoreactivity in the SP was similar to that at 2 days post‐ischemia, and SOD2 immunoreactivity was newly expressed in glial‐like cells in the strata oriens and radiatum (Figure 6A[g]). In this group, based on double immunofluorescence staining, SOD2 immunoreactive glial cells were identified as GFAP+ astrocytes, not Iba‐I+ microglia (Figure 6C). In the IPC + sham‐operated‐group, SOD2 immunoreactivity was slightly increased in pyramidal cells of the CA1 region compared with that in the sham‐operated‐group (Figure 6A[b],B). In the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group, SOD2 immunoreactivity in the SP was maintained until 5 days after ischemia‐reperfusion (Figure 6A[e,h],B). SOD2 immunoreactivity in the SP of the CA1 region of the IPC + auranofin + sham‐operated‐group was significantly higher than that that in the sham‐operated‐group; however, the immunoreactivity was slightly lower than that in the IPC + sham‐operated‐group (Figure 6A[c],B). In the IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐group, the change pattern of SOD2 immunoreactivity was similar to that in the ischemia‐operated‐group (Figure 6A[f,i],B).

Figure 6.

A. Effect of IPC on SOD2 immunoreactivity in the CA1 region of the ischemia‐operated‐ (left column), IPC + ischemia‐operated‐ (middle column) and IPC + aur + ischemia‐operated‐ (right column) groups at sham (a–c), 2 (d–f) and 5 days (g–i) post‐ischemia. A. In the ischemia‐operated‐ and IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐groups, SOD2 immunoreactivity is apparently decreased in the stratum pyramidale (SP, asterisk) at 2 and 5 days post‐ischemia. In the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group, SOD2 immunoreactivity in the SP is increased compared with that in the sham‐operated‐group. CA1, cornus ammonis 1; SO, stratum oriens; SR, stratum radiatum. Scale bar = 50 μm. B. Quantitative analysis of SOD2 immunoreactivity in the SP from all the groups. A ratio of the ROD was calibrated as %, with the sham‐operated‐group designated as 100%. The bars indicate the means ± SEM (* P < 0.05 vs. sham‐operated‐group; # P < 0.05 vs. ischemia‐operated‐group; $ P < 0.05 vs. IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group). C. Double immunofluorescence staining for SOD2 (green, a), GFAP (red, b) and merged images (c) at 5 days post‐ischemia. SOD2+ non‐pyramidal cells are colocalized with GFAP+ astrocytes (white arrows). Scale bar = 20 μm. D and E. Western blot analysis of SOD2 protein in the hippocampus derived from all the groups. Protein expression is normalized to β‐actin. The bars indicate the means ± SEM (* P < 0.05 vs. sham‐operated‐group; # P < 0.05 vs. ischemia‐operated‐group; $ P < 0.05 vs. IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group).

The result of western blot study showed that the change pattern of SOD2 protein level in the hippocampus was generally similar to the immunohistochemical change (Figure 6D,E). SOD2 protein level was significantly decreased at 2 days post‐ischemia compared with that in the sham‐operated‐group, and the protein level was much more decreased at 5 days post‐ischemia (Figure 6D,E). In the IPC + sham‐ and IPC + ischemia‐operated‐groups, SOD2 protein levels were not significantly changed compared with that in the sham‐operated‐group (Figure 6D,E), In addition, the change pattern of SOD2 protein level in the IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐group was similar to that in the ischemia‐operated‐group (Figure 6D,E). SOD2 protein level was significantly decreased with time after ischemia‐reperfusion (Figure 6D,E).

DHE fluorescence

In the sham‐operated‐group, superoxide anion radical level by DHE fluorescence was very weakly detected in the SP of the CA1 region (Figure 7A[a–c]). Two days after ischemia‐reperfusion, superoxide anion radical production was increased in all the groups; the superoxide anion radical level in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group was significantly lower than that in ischemia‐operated‐ and IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐groups (Figure 7A[d–f],B). At 5 days post‐ischemia, although superoxide anion radical production was decreased in all the groups, the superoxide anion radical level in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group was significantly lower than that in both ischemia‐operated‐ and IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐groups (Figure 7A[g–i],B).

Figure 7.

A. Effect of IPC on superoxide anion production in the CA1 region of the ischemia‐operated‐ (left column), IPC + ischemia‐operated‐ (middle column) and IPC + aur + ischemia‐operated‐groups (right column) at sham (a–c), 2 (d–f) and 5 days (g–i) post‐ischemia. Immunofluorescence of DHE is increased in the stratum pyramidale (SP, asterisks) in the ischemia‐operated and IPC + auranofin +ischemia‐operated‐groups at 2 days post‐ischemia; however, at 5 days post‐ischemia, the immunoreactivity is significantly low (arrows) only in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group. CA1, cornus ammonis 1; SO, stratum oriens; SR, stratum radiatum. Scale bar = 50 μm. B. Quantitative analysis of DHE immunofluorescence in the stratum pyramidale from all the groups. A ratio of the ROD was calibrated as %, with the sham‐operated‐group designated as 100%. The bars indicate the means ± SEM (* P < 0.05 vs. sham‐operated‐group; # P < 0.05 vs. ischemia‐operated‐group; $ P < 0.05 vs. IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group).

Reduction of ischemia‐induced neuronal apoptosis by IPC‐mediated increase of Trx2

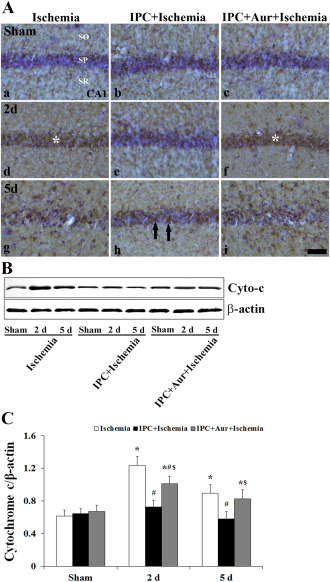

Cytochrome c immunoreactivity and its protein level

In the sham‐operated‐group, weak cytochrome c (denatured form) immunoreactivity was detected in the SP of the CA1 region (Figure 8A[a–c]). Cytochrome c immunoreactivity was significantly increased in the SP in the IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐group as well as in the ischemia‐operated‐group at 2 days post‐ischemia (Figure 8A[d,f]); in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group, however, cytochrome c immunoreactivity was not increased in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group (Figure 8A[e]). At 5 days post‐ischemia, cytochrome c immunoreactivity was slightly increased in the SP of the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group; however, in the other groups, strong cytochrome c immunoreactivity was shown in the strata oriens and radiatum (Figure 8A[g–i]).

Figure 8.

A. Effect of IPC on cytochrome c (denatured form) expression in the CA1 region of the ischemia‐operated‐ (left column), IPC + ischemia‐operated‐ (middle column) and IPC + aur + ischemia‐operated‐ (right column) groups at sham (a–c), 2 (d–f) and 5 days (g–i) post‐ischemia. Cytochrome c immunoreactivity is significantly changed in the stratum pyramidale (SP, asterisks) of the ischemia‐operated‐ and IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐groups at 2 days post‐ischemia; however, cytochrome c immunoreactivity (arrows) is not changed in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group. CA1, cornus ammonis 1; SO, stratum oriens; SR, stratum radiatum. Scale bar = 50 μm. B and C. Western blot analysis of cytochrome c protein in the hippocampus derived from all the groups. Protein expression is normalized to β‐actin. The bars indicate the means ± SEM (* P < 0.05 vs. sham‐operated‐group; # P < 0.05 vs. ischemia‐operated‐group; $ P < 0.05 vs. IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group).

In addition, western blot study showed that cytochrome c protein level was significantly increased in the IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐groups as well as in the ischemia‐operated‐group compared with that in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group (Figure 8B,C).

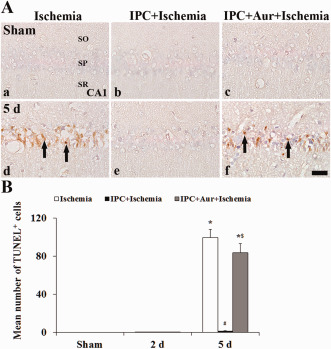

TUNEL+ cells

Pyramidal neurons in the CA1 region were not stained with TUNEL in the sham‐operated‐, IPC+ sham‐operated‐ and IPC + auranofin + sham‐operated‐groups (Figure 9A[a–c],B). At 5 days post‐ischemia, many TUNEL+ neurons were found in the SP of the ischemia‐operated‐group (Figure 9A[d],B), not in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group (Figure 9A[e],B). However, in the IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐group, the neuroprotective effect of IPC was strongly reduced (Figure 9A[f],B).

Figure 9.

A. Effect of IPC on TUNEL+ cells in the CA1 region of the ischemia‐operated‐ (left column), IPC + ischemia‐operated‐ (middle column) and IPC + aur + ischemia‐operated‐ (right column) groups at sham (a–c) and 5 days (d–f) post‐ischemia. Many TUNEL+ cells (arrows) are found in the stratum pyramidale of the IPC + auranofin‐ischemia‐operated‐group as well as in the ischemia‐operated‐group; however, no TUNEL+ cells are shown in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group. CA1, cornus ammonis 1; SO, stratum oriens; SP, stratum pyramidale; SR, stratum radiatum. Scale bar = 50 μm. B. Quantitative analysis of TUNEL+ cells in the SP from all the groups. The bars indicate the means ± SEM (* P < 0.05 vs. sham‐operated‐group; # P < 0.05 vs. ischemia‐operated‐group; $ P < 0.05 vs. IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group).

DISCUSSION

The major novel findings of the current study are that (i) IPC significantly protected pyramidal neurons of the CA1 region from a subsequent ischemic damage; (ii) IPC markedly attenuated oxidative stress via increasing or maintaining Trx2 expression followed by increasing or maintaining SOD2 expression in CA1 pyramidal neurons; (iii) IPC significantly reduced cerebral ischemia‐induced neuronal apoptosis via decreasing the expression of denatured cytochrome c, which was provably attenuated by Trx2.

Transient global cerebral ischemia occurs commonly when cardiac arrest breaks out and selectively induces neuronal damage/death in some specific brain regions including the hippocampus, neocortex and striatum, which is commonly referred to as “selective vulnerability of the brain” 32. Especially, pyramidal neurons in the CA1 region do not die immediately but survive over several days after transient global cerebral ischemia. This unique process is termed “delayed neuronal death (DND)” 31. The Mongolian gerbil has been used as a good animal model to investigate the molecular mechanism of neuronal damage following transient global cerebral ischemia 4, 42 because about 90% of gerbils lack the communicating vessels between the carotid and vertebral circulations 15, 25, 59. Thus, the occlusion of both common carotid arteries completely removes the blood flow to the forebrain while completely sparing the vegetative centers of the brainstem.

IPC can induce neuronal tolerance to a subsequent longer or lethal period of transient ischemia and does not lead to neuronal death 36. Preconditioning time period was determined by a previous report 46; it indicated that at least a 1 day interval between sublethal 2‐minutes ischemia and lethal 5‐minutes ischemia was necessary for the induction of the neuroprotection of the CA1 pyramidal neurons. In our present study, IPC was induced by subjecting the gerbils to a 2‐minutes transient ischemia followed by 1 day recovery, and we found that, in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐groups, the CA1 pyramidal neurons were well protected from the subsequent transient ischemic damage at 5 days post‐ischemia; the mean number of the dead CA1 pyramidal neurons was significantly decreased by IPC. This result is consistent with our previous study 51. However, until now, the basic biology or mechanism of IPC effect in ischemic insults has been unclear.

Ischemic brain injury is associated with the oxidative stress caused by the overproduction of ROS and other free radicals 27, 29. ROS‐generating systems, such as the electron transport chain in mitochondria and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase in brains, are activated and lead to oxidative stress 29, 44. Excessive ROS production is followed by dysfunctions of important redox‐sensitive enzymes, membrane receptors and ion channels, DNA damage, membrane lipid peroxidation and cytochrome c release from mitochondria, which activate caspases that aggravate cell death after ischemic‐reperfusion injury 70. Thus, neuronal defense mechanisms against oxidative stress have been focused on antioxidant systems, particularly, proteins of the Trx family 68. Antioxidant systems are tightly regulated to maintain the redox balance 70, and endogenous antioxidants can be rapidly used for defense against harmful ROS that are then degraded 2, 5. The Trx system consists of Trx, TrxR and NADPH 41. Trx is a redox (reduction/oxidation)‐active protein containing a dithiol‐active site, which catalyzes electron flux from NADPH through TrxR 21, 41. Trx plays important role in reducing ROS by itself and partly with peroxiredoxin 20, 33, 67. A study, which used transgenic mice that overexpressed Trx, showed that Trx was neuroprotective against ischemic brain damage 65, suggesting that it had a potent antioxidant role and blocked the detrimental action of ROS in the brain. In addition, Trx is oxidized during conditions of oxidative stresses caused by chemical, physical or biologic stimuli. Theoretically, oxidized Trx is reversibly reduced by NADPH and TrxR, whereas the reduced Trx is used for the reduction of peroxiredoxins (Prxs) 54.

Among Trx subtypes, Trx2 is a major player that controls ROS levels in mitochondria and controlled by Trx2R in mitochondria, therefore, it plays a key role in regulating oxidant‐induced cell death. For example, Trx2‐deficient cells undergo apoptosis on the repression of Trx2 transgene, showing an accumulation of intracellular ROS 66. In our present study, we found that Trx2 immunoreactivity in CA1 pyramidal neurons was significantly decreased after ischemia‐reperfusion and that Trx2 immunoreactivity was newly expressed in astrocytes at 5 days post‐ischemia. Unfortunately, we could not explain clearly why Trx2 immunoreactivity was newly expressed in astrocytes after ischemia‐reperfusion. However, it has been reported that astrocytes are hyperactivated in all layers in the CA1 region after transient cerebral ischemia and ischemia‐induced astrocyte activation leads to a release of cytotoxic agents, which induce inflammatory response that is closely related to neuronal death 13, 17. On the basis of the above references, our present finding suggests that new Trx2 expression in astrocytes in the ischemic CA1 region may be related to the delayed neuronal death of the CA1 pyramidal neurons, although further studies need to investigate the exact mechanism of Trx2 in astrocytes. Conversely, we observed that IPC maintained the Trx2 expression in the CA1 pyramidal neurons in the ischemic CA1 region. This finding is supported by a report that showed that expressions of mitochondrial peroxiredoxin and thioredoxin were markedly changed in neurons and glia in the gerbil hippocampal CA1 region induced by transient cerebral ischemia and they showed protective effects in the ischemic CA1 region 24. In addition, Jia et al 26 reported that an increase in Trx2 mRNA was related with the decrease of behavioral deficit and brain infarction through the upregulation of Trx transcription in the rat brain induced by focal cerebral ischemia‐reperfusion injury.

With the above‐mentioned findings, in the present study, we found that IPC significantly elevated the expression of Trx2 in the CA1 pyramidal neurons in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group, which was significantly decreased in the ischemia‐operated‐group. This finding is supported by a paper that showed that hypoxia preconditioning enhanced Trx2 expression that was related with tolerance to hypoxia‐ischemia in the rat brain 57. It was also reported that the transfection of human neurotrophic cells with Trx mRNA antisense oligonucleotides concomitantly blocked Trx biosynthesis that was strongly associated with neuroprotection induced by hypoxia preconditioning 1, 2. Furthermore, we found that the IPC‐mediated neuroprotection was abolished by the inhibition of TrxR2, namely, the treatment of auranofin to the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group did not protect CA1 pyramidal neurons form ischemic damage and dramatically reduced Trx2 expression in the CA1 pyramidal neurons. On the basis of these findings, Trx2 must be a key molecule in IPC‐mediated neuroprotection. We dare to state that one of mechanisms of IPC‐mediated protection against global cerebral ischemia‐reperfusion injury may be the upregulated expression of Trx2.

In our present study, the change pattern of SOD2 immunoreactivity in the CA1 region of the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐groups was similar to the change of Trx2 immunoreactivity in those groups. In addition, the expression of SOD2 in the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐groups was cancelled by auranofin treatment. It is well known that the brain is vulnerable to oxidative damage due to the lack of antioxidant enzymes 37, 69. As major antioxidant enzymes, SODs are located in mitochondria and reduce the damage from oxidative stress through catalyzing superoxide anion radical into oxygen and H2O2 6, 57. The induction of SOD2 in the mitochondria from oxidative stress may be closely associated with Trx2 expression. Some papers have shown that the treatment of exogenous Trx increases expressions of both SOD2 mRNA and its protein level in epithelial cells of the human lens 75 and in microvascular endothelial cells in the human lung 10. Furthermore, we recently reported that the maintenance or increase of endogenous SODs was closely related with protective effects against ischemia‐induced neuronal death in the gerbil hippocampus 38, 74. With these findings, therefore, we strongly suggest that the enhanced expression of SOD2 in the ischemic CA1 pyramidal neurons by IPC is related with neuroprotective effect through Trx2 against oxidative stress induced by ischemia‐reperfusion injury.

Excess production of superoxide anion radical in hippocampal neurons can occur as a result of mitochondrial dysfunction under physiological and pathological conditions 1, 45. In fact, there is a selective vulnerability of CA1 pyramidal neurons to oxidative stress induced by superoxide anion radical, which is thought to be critical in producing neuronal damage 45, 62. Furthermore, in this study, the superoxide anion radical production by DHE fluorescence was significantly increased in the CA1 pyramidal neurons in the ischemia‐operated‐groups and apparently decreased by IPC; however, auranofin treatment to the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐group significantly increased superoxide anion radical production in the CA1 pyramidal neurons. It was reported that the deficiency of SODs resulted in a significant increase in superoxide anion radical production and neuronal death after transient cerebral ischemia in the mouse brain 14, 45 and that the over‐expression of SOD2 reduced the age‐related increase of superoxide anion radical production and prevented a decline of memory function following ischemic damage in rodents 43, 52. In addition, many researchers have suggested that preventing ROS generation by scavenging ROS with Trx2 is important as potential therapeutic strategies for treating ischemia 19, 24, 71. Therefore, our results indicate that Trx2 reduces or scavenges superoxide anion radicals.

Conversely, it was reported that Trx2 documented anti‐apoptotic action, especially, the action was based on the prevention of cytochrome c release from mitochondria 48. In addition, Tanaka et al demonstrated that the deficiency of Trx2 resulted in the elevation of cytochrome c release from the mitochondria in chicken DT40 66. A similar study revealed that overexpressed Trx2 in human mitochondria confered a resistance to oxidant‐induced apoptosis in human osteosarcoma cell line 7. In addition, Trx2 is involved in the regulation of mitochondrial membrane permeability 55 that might be relevant to anti‐apoptotic effects of Trx2 48, 66.

Together the above‐mentioned findings, in this study, we found that TUNEL‐positive cells were not detected in the SP of the CA1 region of the IPC + ischemia‐operated‐groups; however, the inhibition of TrxR2 showed many TUNEL‐positive cells in the SP in the IPC + auranofin + ischemia‐operated‐groups. This finding is supported by some studies that showed that the cytochrome c release from mitochondria to cytosol is closely associated with mitochondria‐mediated apoptosis in the gerbil CA1 region after transient cerebral ischemia 12, 28, 47. These and our observations indicate that the maintenance or increase of Trx2 induced by IPC affects neuronal apoptosis following ischemia‐reperfusion.

In brief, we had focused on the role of Trx2 in IPC‐mediated neuroprotection against oxidative stress and apoptosis in the hippocampal CA1 region followed by a subsequent ischemia‐reperfusion using a gerbil model of transient cerebral ischemia and demonstrated that increased or maintained Trx2 expression prevented the CA1 pyramidal neurons form ischemic injury via controlling SOD2 expression followed by ROS production through Trx2. Therefore, this study strongly suggest that maintaining or enhancing Trx2 expression may be a legitimate strategy for therapeutic intervention of cerebral ischemic injury.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Mr. Seung Uk Lee for their technical help. This research was supported by the Bio‐Synergy Research Project (NRF‐2015M3A9C4076322) of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning through the National Research Foundation, by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF‐2013M3A9B6046563), which was funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning, and by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the NRF funded by the Korean government, MSIP (NRF‐2015M3A9B6066835).

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Moo‐Ho Won, Email: mhwon@kangwon.ac.kr.

Young‐Myeong Kim, Email: ymkim@kangwon.ac.kr.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bindokas VP, Jordan J, Lee CC, Miller RJ (1996) Superoxide production in rat hippocampal neurons: selective imaging with hydroethidine. J Neurosci 16:1324–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bulkley GB (1987) Free radical‐mediated reperfusion injury: a selective review. Br J Cancer Suppl 8:66–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Candelario‐Jalil E, Alvarez D, Merino N, Leon OS (2003) Delayed treatment with nimesulide reduces measures of oxidative stress following global ischemic brain injury in gerbils. Neurosci Res 47:245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cao Y, Mao X, Sun C, Zheng P, Gao J, Wang X et al (2011) Baicalin attenuates global cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in gerbils via anti‐oxidative and anti‐apoptotic pathways. Brain Res Bull 85:396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chan PH (2001) Reactive oxygen radicals in signaling and damage in the ischemic brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 21:2–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen X, Stern D, Yan SD (2006) Mitochondrial dysfunction and Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 3:515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen Y, Cai J, Murphy TJ, Jones DP (2002) Overexpressed human mitochondrial thioredoxin confers resistance to oxidant‐induced apoptosis in human osteosarcoma cells. J Biol Chem 277:33242–33248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Damdimopoulos AE, Miranda‐Vizuete A, Pelto‐Huikko M, Gustafsson JA, Spyrou G (2002) Human mitochondrial thioredoxin. Involvement in mitochondrial membrane potential and cell death. J Biol Chem 277:33249–33257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Das KC, Das CK (2000) Thioredoxin, a singlet oxygen quencher and hydroxyl radical scavenger: redox independent functions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 277:443–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Das KC, Lewis‐Molock Y, White CW (1997) Elevation of manganese superoxide dismutase gene expression by thioredoxin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 17:713–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dirnagl U, Becker K, Meisel A (2009) Preconditioning and tolerance against cerebral ischaemia: from experimental strategies to clinical use. Lancet Neurol 8:398–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Endo H, Kamada H, Nito C, Nishi T, Chan PH (2006) Mitochondrial translocation of p53 mediates release of cytochrome c and hippocampal CA1 neuronal death after transient global cerebral ischemia in rats. J Neurosci 26:7974–7983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Endoh M, Maiese K, Wagner J (1994) Expression of the inducible form of nitric oxide synthase by reactive astrocytes after transient global ischemia. Brain Res 651:92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fujimura M, Morita‐Fujimura Y, Narasimhan P, Copin JC, Kawase M, Chan PH (1999) Copper‐zinc superoxide dismutase prevents the early decrease of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease and subsequent DNA fragmentation after transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Stroke 30:2408–2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fukuchi T, Katayama Y, Kamiya T, McKee A, Kashiwagi F, Terashi A (1998) The effect of duration of cerebral ischemia on brain pyruvate dehydrogenase activity, energy metabolites, and blood flow during reperfusion in gerbil brain. Brain Res 792:59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Go YM, Jones DP (2009) Thioredoxin redox western analysis. Curr Protoc Toxicol Unit 17:12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gu L, Huang B, Shen W, Gao L, Ding Z, Wu H, Guo J (2013) Early activation of nSMase2/ceramide pathway in astrocytes is involved in ischemia‐associated neuronal damage via inflammation in rat hippocampi. J Neuroinflammation 10:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hansen JM (2012) Thioredoxin redox status assessment during embryonic development: the redox Western. Methods Mol Biol 889:305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hattori I, Takagi Y, Nakamura H, Nozaki K, Bai J, Kondo N et al (2004) Intravenous administration of thioredoxin decreases brain damage following transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Antioxid Redox Signal 6:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hirota K, Murata M, Sachi Y, Nakamura H, Takeuchi J, Mori K, Yodoi J (1999) Distinct roles of thioredoxin in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus. A two‐step mechanism of redox regulation of transcription factor NF‐kappaB. J Biol Chem 274:27891–27897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Holmgren A (1985) Thioredoxin. Annu Rev Biochem 54:237–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holmgren A (1989) Thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. J Biol Chem 264:13963–13966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Horn M, Schlote W (1992) Delayed neuronal death and delayed neuronal recovery in the human brain following global ischemia. Acta Neuropathol 85:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hwang IK, Yoo KY, Kim DW, Lee CH, Choi JH, Kwon YG et al (2010) Changes in the expression of mitochondrial peroxiredoxin and thioredoxin in neurons and glia and their protective effects in experimental cerebral ischemic damage. Free Radic Biol Med 48:1242–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Janac B, Radenovic L, Selakovic V, Prolic Z (2006) Time course of motor behavior changes in Mongolian gerbils submitted to different durations of cerebral ischemia. Behav Brain Res 175:362–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jia J, Zhang X, Hu YS, Wu Y, Wang QZ, Li NN et al (2009) Protective effect of tetraethyl pyrazine against focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats: therapeutic time window and its mechanism. Thromb Res 123:727–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jung JE, Kim GS, Chen H, Maier CM, Narasimhan P, Song YS et al (2010) Reperfusion and neurovascular dysfunction in stroke: from basic mechanisms to potential strategies for neuroprotection. Mol Neurobiol 41:172–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kadenbach B, Arnold S, Lee I, Huttemann M (2004) The possible role of cytochrome c oxidase in stress‐induced apoptosis and degenerative diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1655:400–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim GS, Jung JE, Niizuma K, Chan PH (2009) CK2 is a novel negative regulator of NADPH oxidase and a neuroprotectant in mice after cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci 29:14779–14789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim HJ, Lee SR, Moon KD (2003) Ether fraction of methanol extracts of Gastrodia elata, medicinal herb protects against neuronal cell damage after transient global ischemia in gerbils. Phytother Res 17:909–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kirino T (1982) Delayed neuronal death in the gerbil hippocampus following ischemia. Brain Res 239:57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kirino T, Sano K (1984) Selective vulnerability in the gerbil hippocampus following transient ischemia. Acta Neuropathol 62:201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kong L, Zhou X, Li F, Yodoi J, McGinnis J, Cao W (2010) Neuroprotective effect of overexpression of thioredoxin on photoreceptor degeneration in Tubby mice. Neurobiol Dis 38:446–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kuchinka J, Nowak E, Szczurkowski A, Kuder T (2008) Arteries supplying the base of the brain in the Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus). Pol J Vet Sci 11:295–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee JC, Park JH, Ahn JH, Kim IH, Cho JH, Choi JH et al (2015) New GABAergic neurogenesis in the hippocampal CA1 region of a gerbil model of long‐term survival after transient cerebral ischemic injury. Brain Pathol, doi: 10.1111/bpa.12334. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lehotsky J, Burda J, Danielisova V, Gottlieb M, Kaplan P, Saniova B (2009) Ischemic tolerance: the mechanisms of neuroprotective strategy. Anat Rec 292:2002–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leutner S, Eckert A, Muller WE (2001) ROS generation, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzyme activities in the aging brain. J Neural Transm 108:955–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li H, Park JH, Lee JC, Yoo KY, Hwang IK, Lee CH et al (2013) Neuroprotective effects of Alpinia katsumadai against experimental ischemic damage via control of oxidative stress. Pharm Biol 51:197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lin HW, Thompson JW, Morris KC, Perez‐Pinzon MA (2011) Signal transducers and activators of transcription: STATs‐mediated mitochondrial neuroprotection. Antioxid Redox Signal 14:1853–1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lu J, Holmgren A (2014) The thioredoxin antioxidant system. Free Radic Biol Med 66:75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Luthman M, Holmgren A (1982) Rat liver thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase: purification and characterization. Biochemistry 21:6628–6633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Malek M, Duszczyk M, Zyszkowski M, Ziembowicz A, Salinska E (2013) Hyperbaric oxygen and hyperbaric air treatment result in comparable neuronal death reduction and improved behavioral outcome after transient forebrain ischemia in the gerbil. Exp Brain Res 224:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Massaad CA, Washington TM, Pautler RG, Klann E (2009) Overexpression of SOD‐2 reduces hippocampal superoxide and prevents memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:13576–13581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moro MA, Almeida A, Bolanos JP, Lizasoain I (2005) Mitochondrial respiratory chain and free radical generation in stroke. Free Radic Biol Med 39:1291–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Murakami K, Kondo T, Kawase M, Li Y, Sato S, Chen SF, Chan PH (1998) Mitochondrial susceptibility to oxidative stress exacerbates cerebral infarction that follows permanent focal cerebral ischemia in mutant mice with manganese superoxide dismutase deficiency. J Neurosci 18:205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nakamura H, Katsumata T, Nishiyama Y, Otori T, Katsura K, Katayama Y (2006) Effect of ischemic preconditioning on cerebral blood flow after subsequent lethal ischemia in gerbils. Life Sci 78:1713–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nakatsuka H, Ohta S, Tanaka J, Toku K, Kumon Y, Maeda N et al (2000) Cytochrome c release from mitochondria to the cytosol was suppressed in the ischemia‐tolerance‐induced hippocampal CA1 region after 5‐min forebrain ischemia in gerbils. Neurosci Lett 278:53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nonn L, Williams RR, Erickson RP, Powis G (2003) The absence of mitochondrial thioredoxin 2 causes massive apoptosis, exencephaly, and early embryonic lethality in homozygous mice. Mol Cell Biol 23:916–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Numagami Y, Sato S, Ohnishi ST (1996) Attenuation of rat ischemic brain damage by aged garlic extracts: a possible protecting mechanism as antioxidants. Neurochem Int 29:135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ozkan A, Sen HM, Sehitoglu I, Alacam H, Guven M, Aras AB et al (2015) Neuroprotective effect of humic acid on focal cerebral ischemia injury: an experimental study in rats. Inflammation 38:32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Park YS, Cho JH, Kim IH, Cho GS, Park JH, Ahn JH et al (2014) Effects of ischemic preconditioning on VEGF and pFlk‐1 immunoreactivities in the gerbil ischemic hippocampus after transient cerebral ischemia. J Neurol Sci 347:179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Peluffo H, Acarin L, Aris A, Gonzalez P, Villaverde A, Castellano B, Gonzalez B (2006) Neuroprotection from NMDA excitotoxic lesion by Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene delivery to the postnatal rat brain by a modular protein vector. BMC Neurosci 7:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Petito CK, Feldmann E, Pulsinelli WA, Plum F (1987) Delayed hippocampal damage in humans following cardiorespiratory arrest. Neurology 37:1281–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rhee SG, Chae HZ, Kim K (2005) Peroxiredoxins: a historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling. Free Radic Biol Med 38:1543–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rigobello MP, Callegaro MT, Barzon E, Benetti M, Bindoli A (1998) Purification of mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase and its involvement in the redox regulation of membrane permeability. Free Radic Biol Med 24:370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rigobello MP, Messori L, Marcon G, Agostina Cinellu M, Bragadin M, Folda A et al (2004) Gold complexes inhibit mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase: consequences on mitochondrial functions. J Inorg Biochem 98:1634–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sato EF, Higashino M, Ikeda K, Wake R, Matsuo M, Utsumi K, Inoue M (2003) Oxidative stress‐induced cell death of human oral neutrophils. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284:C1048–C1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schmued LC, Hopkins KJ (2000) Fluoro‐Jade B: a high affinity fluorescent marker for the localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res 874:123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Selakovic V, Korenic A, Radenovic L (2011) Spatial and temporal patterns of oxidative stress in the brain of gerbils submitted to different duration of global cerebral ischemia. Int J Dev Neurosci 29:645–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Spyrou G, Enmark E, Miranda‐Vizuete A, Gustafsson J (1997) Cloning and expression of a novel mammalian thioredoxin. J Biol Chem 272:2936–2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stroev SA, Gluschenko TS, Tjulkova EI, Spyrou G, Rybnikova EA, Samoilov MO, Pelto‐Huikko M (2004) Preconditioning enhances the expression of mitochondrial antioxidant thioredoxin‐2 in the forebrain of rats exposed to severe hypobaric hypoxia. J Neurosci Res 78:563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sugawara T, Chan PH (2003) Reactive oxygen radicals and pathogenesis of neuronal death after cerebral ischemia. Antioxid Redox Signal 5:597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sun N, Hao JR, Li XY, Yin XH, Zong YY, Zhang GY, Gao C (2013) GluR6‐FasL‐Trx2 mediates denitrosylation and activation of procaspase‐3 in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats. Cell Death Dis 4:e771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Szocs K, Lassegue B, Sorescu D, Hilenski LL, Valppu L, Couse TL et al (2002) Upregulation of Nox‐based NAD(P)H oxidases in restenosis after carotid injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22:21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Takagi Y, Mitsui A, Nishiyama A, Nozaki K, Sono H, Gon Y et al (1999) Overexpression of thioredoxin in transgenic mice attenuates focal ischemic brain damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:4131–4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tanaka T, Hosoi F, Yamaguchi‐Iwai Y, Nakamura H, Masutani H, Ueda S et al (2002) Thioredoxin‐2 (TRX‐2) is an essential gene regulating mitochondria‐dependent apoptosis. EMBO J 21:1695–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Turoczi T, Chang VW, Engelman RM, Maulik N, Ho YS, Das DK (2003) Thioredoxin redox signaling in the ischemic heart: an insight with transgenic mice overexpressing Trx1. J Mol Cell Cardiol 35:695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ueda S, Masutani H, Nakamura H, Tanaka T, Ueno M, Yodoi J (2002) Redox control of cell death. Antioxid Redox Signal 4:405–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Urikova A, Babusikova E, Dobrota D, Drgova A, Kaplan P, Tatarkova Z, Lehotsky J (2006) Impact of Ginkgo Biloba Extract EGb 761 on ischemia/reperfusion ‐ induced oxidative stress products formation in rat forebrain. Cell Mol Neurobiol 26:1343–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J (2007) Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 39:44–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wang L, Jiang DM (2009) Neuroprotective effect of Buyang Huanwu Decoction on spinal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. J Ethnopharmacol 124:219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wegener S, Gottschalk B, Jovanovic V, Knab R, Fiebach JB, Schellinger PD et al (2004) Transient ischemic attacks before ischemic stroke: preconditioning the human brain? A multicenter magnetic resonance imaging study. Stroke 35:616–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]