Abstract

Exercise is one of the most effective strategies to maintain a healthy body and mind, with particular beneficial effects of exercise on promoting brain plasticity, increasing cognition and reducing the risk of cognitive decline and dementia in later life. Moreover, the beneficial effects resulting from increased physical activity occur at different levels of cellular organization, mitochondria being preferential target organelles. The relevance of this review article relies on the need to integrate the current knowledge of proposed mechanisms, focus mitochondria, to explain the protective effects of exercise that might underlie neuroplasticity and seeks to synthesize these data in the context of exploring exercise as a feasible intervention to delay cognitive impairment associated with neurodegenerative conditions, particularly Alzheimer disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, exercise, mitochondria

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer disease (AD), the most common neurodegenerative disorder in which the nervous system progressively and irreversibly deteriorates, affects millions of people worldwide. The etiology of AD has a genetic background in 1%–5% of the population (familial early‐onset <60 years), while the majority, accounting for more than 95%, represent sporadic cases (late‐onset >60 years) 183. As AD is mainly a late‐onset age‐dependent disorder, it is estimated that its prevalence will increase along with the increase in life expectancy, exacerbating the societal and economic impact in the coming years. AD clearly is associated with systemic manifestations that extend beyond the central nervous system. In fact, triggered by environmental and endogenous factors, the risk for brain dysfunction and AD is augmented by obesity, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and chronic inflammation 151.

The symptoms of AD appear several years after the disease initiation and are characterized by a progressive cognitive decline, mostly related with memory and thinking language impairment, confusion and disorientation 88. Additionally, AD is related with neurobehavioral disarrangements, including apathy, depression, agitation and anxiety 88. The AD brain is further characterized by decreased neuronal cell proliferation 95, 96, survival 115, 201 and differentiation 15, 56, and a progressive loss of neurons and synapses number in specific brain regions, particularly in the hippocampus, followed by changes in the cortical and subcortical structures and complexity 21, 50, 115.

From a histopathological point of view, extracellular deposition of senile plaques (SP) mainly composed of amyloid β peptide (Aβ) and intracellular deposition of neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), comprised of hyperphosphorylated tau are common features of AD clinical diagnosis stage. In addition, an early intracellular accumulation of Aβ, preceding the formation of extracellular Aβ deposits and NFT formation in the brains of AD patients 89, 90, 117, 149 and of AD mouse models, may be a key factor in the induction of neuronal stress characterizing the progression of AD 167, 180, 215, 221, 222, 235.

Mitochondria have a central role in cellular energy metabolism; however, these organelles are also involved in several other important cellular tasks, such as intracellular calcium regulation and redox and apoptotic signaling. The progressively accumulation of Aβ within mitochondria has also been associated with the onset and progression of AD neuronal homeostasis perturbation. Accordingly, Swerdlow and Khan 211 proposed the “mitochondrial cascade hypothesis” to explain sporadic late‐onset AD. Briefly, this hypothesis suggests that mitochondrial deregulation is the primary event in AD sporadic pathology leading to SN and NFT deposition. The precise mechanism behind this is still elusive, although some studies indicate that gradual accumulation of Aβ within mitochondria may be the link for mitochondria‐mediated toxicity 35, 97. Moreover, mitochondrial dysfunction comprises an increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) namely superoxide anion ( ), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radical (•OH), which further enhances Aβ production closing a vicious circle 124.

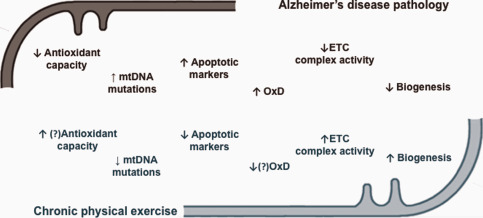

Physical exercise has been associated with neuronal protection against aging associated alterations and is recommended as a preventive and therapeutic non‐pharmacological strategy in the management of patients with neurodegenerative disorders 4, 113, 138. Although this concept is nowadays accepted, the precise molecular mechanism by which physical exercise protects the brain against the onset and the progression of AD has not been fully understood so far. Exercise induces a myriad of cellular and subcellular adaptations, being probably one of the most important the modulation of mitochondrial network 140, 162. In fact, given the pivotal role of mitochondria providing the energy required for metabolism, it is not surprising that modulation in these organelles even in non‐contractile tissue, such as brain, have been associated with physical exercise. Therefore, it is expected that mitochondria may have a central role to explain the cross‐tolerance phenomena between exercise and AD (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic summary of described adaptations triggered by chronic physical exercise against brain mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease pathology (Adapted from 138 with permission). mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; OxD, oxidative damage; ETC, electron transport chain; ↑, increase; ↓, decrease;?, no consensual information.

The present review discusses the potentiality of physical exercise as a mediator of neuroprotection against AD. Particularly, this work highlights the role of mitochondria as critical organelles responsible for adaptive responses with potential beneficial neurological outcomes. It is our belief that the understanding of the potential interaction between physical exercise and mitochondrial‐related paths are essential to fully ascertain the safety and efficient application of exercise models as examples of active life‐styles and supportive interventions to delay and antagonize AD side effects.

THE RELEVANCE OF MITOCHONDRIA FOR A HEALTHY BRAIN FUNCTION

High metabolic energy demands are required by the human brain for its normal function. Despite its small size, brain consumes about 20% of the body's total oxygen. In fact, since neurons have a limited glycolytic capacity, they are highly dependent on mitochondrial energy production. Approximately 90% of cerebral adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production occurs in the mitochondria 188. This energy is essential to support several cellular processes, such as synthesis, secretion and recycling of neurotransmitters and neuronal membrane potential 130. However, together with energy metabolism, mitochondria also play a pivotal role in cell survival and death‐related mechanisms maintaining cellular redox potential, regulating apoptotic pathways and contributing to the regulation of synaptic plasticity 143. Moreover, mitochondria are also involved in intracellular calcium (Ca2+) homeostasis 108. For instance, synaptic terminal mitochondria accumulate or release excess intracellular Ca2+ to maintain homeostasis 213. Being synaptic mitochondria involved in the regulation of neurotransmission 19, mitochondrial function impairment leads to cellular alterations that range from subtle changes in neuronal function to neuronal death and degeneration.

Mitochondria are the major producer of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and at the same time a target of ROS toxicity 74. Under normal physiological conditions, ROS are produced by electron leakage as a byproduct of OXPHOS; however an efficient antioxidant network counteracts its harmful effects 217. Moreover, ROS are also involved in intracellular signaling pathways acting as second messengers 5, thus subtle rise of the steady‐state ROS concentration has been considered to have a fundamental physiological role 69. However, when mitochondrial function is compromised, an imbalance in the redox steady‐state may occur either by an increased ROS production or by a decreased antioxidant defense capability. In fact, a supra‐physiological production of mitochondrial ROS linked to a defective scavenging system is associated with aging and age‐associated diseases, such as AD 17, 155. Neurons increased susceptibility to oxidation because of its polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) enriched membranes, low activity of antioxidant enzymes 166, 191, and its high content in transition metals 109, 110, 146, causes irreversible alterations to surrounding macromolecules and ultimately facilitates neuronal degeneration and death.

Neurons are elongated cells in which energy‐dependent mechanisms must spatially match energy production to local energy usage. Therefore, mitochondria have a ubiquitous distribution along the cells with a major presence in synapses, where the demand for ATP is critical for synaptic transmission. In axons, mitochondrial movement is driven by two oppositely directed motor proteins throughout the microtubules, kinesins and dyneins 16, 103. Tightly bind to microtubules, the microtubule associated proteins (MAPs), including tau, regulate their function and also ensure the transport cargo 129, 224. This organized railroad to transport mitochondria from soma to nerve terminals (providing a localized ATP supply and Ca2+‐buffering capacity) or back to soma in a retrograde way (for recycling damaged mitochondria by mitophagic processes) is essential for neuron survival. However, besides mitochondrial rapid bidirectional transport, the crosstalk between mitochondrial quality‐control systems and autophagy are also central for the maintenance of a precisely distributed and healthy/functional mitochondrial network. Mitochondrial dynamics is governed by fission and fusion events in which small spheres or tubular‐like structures are respectively generated, being these process intimately connected with biogenesis and selective degradation 218. Generally, dysfunctional mitochondria can be repaired by fusion with healthy mitochondria allowing the mixture of its contents, whereas severely damaged mitochondria are segregated by fission, ultimately leading to their elimination by mitophagy (a cargo‐selective autophagic mechanism that degrades mitochondria within lysosomes after their transport back to the soma) 41, 64, 234, 244. These dynamic processes regulate mitochondrial function by enabling the recruitment of healthy mitochondria to subcellular compartments with high demands for ATP, the content exchange between mitochondria and the mitochondrial shape control and mitochondrial turnover via mitophagy 30, 41, 200. Therefore, these mechanisms constitute a closely coordinated and reciprocal elaborate system of mitochondrial quality control, constantly monitored in order to maintain a healthy mitochondrial population and consequent neurons viability. Disruptions in any of these processes lead to mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular failure and neurological defects 41, 200.

Considering the importance of mitochondrial machinery in neuronal function, it is not surprising that mitochondrial dysfunction has been recognized as an early event in AD pathology, preceding and inducing neurodegeneration and memory loss. The mechanisms behind the interaction between the hallmarks of AD and mitochondrial dysfunction will be addressed to better comprehend mitochondria has a therapeutic target against the onset and progression of AD.

HALLMARKS OF AD‐INDUCED MITOCHONDRIAL DYSFUNCTION

APP and Aβ

In mammals, the Amyloid‐β protein precursor (APP) gene family comprises, besides APP, the two amyloid precursor‐like proteins APLP1 and APLP2. These are type 1 membrane proteins with a long extracellular N‐terminal and a short intracellular C‐terminal domain, harboring several protein interaction 173. The APP family members are highly expressed in neurons and have been localized in somata, axons and dendrites. Although the physiological role of APP and its processing products in the central nervous system is controversial, it has been proposed that this protein undergoes fast axonal transport and all three APP family members have been identified as constituents of the presynaptic active zone of central nervous system neurons 120. Even though mice lacking single APP family members are fully viable, they exhibit severe metabolic abnormalities and behavioral deficits 100, 186. In contrast, double knockout mice lacking APLP1/APLP2 or APP/APLP2 die within the first day after birth 100, 227, suggesting a determinant physiological role of these proteins, particularly APP2. The APP localized in the plasma membrane 111 has been suggested to have important roles in cell adhesion 28 and cell movement 189. However, APP can still be found in cellular organelles, including the trans‐Golgi network 236, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), endosomal, lysosomal 111 and mitochondrial membranes 148.

Currently, it has been proposed that the accumulation of intraneuronal Aβ is an early event in the progression of AD, preceding the formation of extracellular Aβ deposits. In fact, a link between intracellular and extracellular Aβ has been explored suggesting that extracellular Aβ may originate from intraneuronal pools and a delicate dynamic equilibrium exists between these two Aβ pools (reviewed in: 117). Moreover, it has been also proposed that Aβ can be re‐accumulated from the extracellular medium by receptor‐dependent mechanisms 212 or endossomal/lysosomal pathway 165 and/or it can be generated within the ER and Golgi system and secreted as part of the constitutive secretory pathway 48, 91, 98.

Numerous studies report AD pathology associated with abnormal mitochondrial dysfunction and with the mitochondrial localization of Aβ and APP even before extracellular deposition of SP 156, 228, 239, which highlights the particular role of mitochondrial APP as an early feature for AD pathogenesis. Although under normal circumstances is targeted to the ER and reach their final destination in the plasma membrane through a secretory pathway, it has also been found to be associated with mitochondrial translocation channels under APP overexpression conditions in cell cultures or in the brains of transgenic mice overexpressing APP 10, forming a super‐complex with Tom40 and Tim23 subunits 147. This accumulation of APP in mitochondrial import channels is negatively associated with the ability to import nuclear‐encoded proteins, eventually resulting in the collapse of mitochondrial function and ultimately in neuronal cell death in AD‐affected brain regions 65. Nevertheless, a mechanism involving the cleavage of APP by serine protease HTRA2 in mitochondrial intermembrane space seems to prevent mitochondrial dysfunction caused by the accumulation of APP 158. Moreover, the protease Omi, involved in mitochondrial quality control by degrading unfolded or misfolded proteins 177 is also involved in mitochondria‐associated APP cleavage 161. However, it remains to be clarified if the inhibition of APP accumulation in mitochondrial import channels or increased proteolysis of APP would protect neurons from mitochondria‐mediated injury and potentially decelerate AD progression 160.

Studies on post‐mortem AD brains, patients with cortical plaques and transgenic APP mice have shown that Aβ accumulates within mitochondria, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction (mtDNA defects, abnormalities in mitochondrial dynamic and trafficking) 35, 65, 70, 128, 132. Although the exact mechanisms are not fully understood, accumulating evidence suggest that Aβ is imported to mitochondria. In fact, since active γ‐secretase was found to be particularly abundant in the contact sites connecting mitochondria and ER 11, it is possible that under pathological AD conditions, significant amounts of Aβ can be produced in the mitochondria surrounding area, resulting in Aβ‐mediated mitochondrial dysfunction. Nevertheless, the understanding of how Aβ can reach mitochondria has been particularly challenging. Several authors proposed complex pathways of Aβ traffic‐mediating mitochondrial and neuronal dysfunction. Hanson and coworkers 165 suggested that Aβ is accumulated by mitochondria through the TOM complex and accumulates in mitochondrial cristae. Both Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 import were prevented by pre‐treatment with proteinase K to remove receptors from the outer mitochondrial membrane, Tom20, Tom22 and Tom70. Moreover, Takuma et al 212, suggested that the receptor for advanced glycation end‐products (RAGEs) is also a binding receptor for Aβ, and therefore mediates the intraneuronal transport of Aβ and the consequent mitochondrial and neuronal dysfunction. However, Cha et al 37 reported that blocking RAGEs in HT22 cell line failed to rescue the Aβ1–42‐mediated mitochondrial disruption of both morphology and function, which suggests that RAGE‐Aβ engagement is not involved in the process of mitochondrial disruption by Aβ. Mitochondrial Aβ accumulation also can derive from the ER/Golgi. As previously stated, several subcellular compartments, including trans‐Golgi network, lysosomes and ER, may participate in APP amyloidogenic processing and Aβ generation within the cells. The ER and mitochondria are organelles functionally and morphologically connected via mitochondria‐associated ER membranes (MAM), and involved in crucial cellular metabolic processes, such as calcium signaling, glucose, phospholipid and cholesterol metabolism, and the regulation of apoptosis 58, 99. Impairment of the communication between ER and mitochondria may represent a common hit in AD as these processes seem to be significantly altered early during AD pathogenesis 18, 142, 204. In fact, an abnormal expression of some MAM‐associated proteins in post‐mortem AD brains and AD transgenic mice models were also shown 101. The enzymes of the amyloidogenic pathway have been shown to localize in MAM (reviewed elsewhere: 168), which makes it a site of Aβ production in close proximity to mitochondria 194. Moreover, besides being a possible source of mitochondria‐localized Aβ 11, it has been suggested that this pathway affects the metabolic and signaling pathways ruled by this site 194.

Tau and intracellular neurofibrillary lesions

Along with Aβ, tau hyperphosphorylation and aggregation are major proximal causes of neuron loss in AD pathogenesis 22. Tau is an important microtubule‐associated protein abundant in the central nervous system 20. Under physiological conditions, tau is a soluble protein that promotes microtubule assembly and stabilization, and affects the dynamics of microtubules in neurons (reviewed in: 13, 106 13, 106, 117, 121). The phosphorylation of tau regulates microtubule binding and assembly 228; however, under pathologic conditions, tau overexpression and hyperphosphorylation at certain residues appears to impair axonal transport of organelles through microtubules, including mitochondria, causing synapse “starvation” and depletion of ATP 6, 27, 136, 192, 197. Under this pathological condition, tau undergoes a series of post‐translational changes including abnormal phosphorylation, glycosylation, glycation and truncation (reviewed in: 9, which may render tau more prone to form NFT, a major hallmark of AD. Following aggregation, microtubules disintegrate, impairing the neuronal transport system and eventually leading to cell death. Hyperphosphorylation is believed to be an early event in the pathway that leads from soluble to insoluble and filamentous tau protein 26, resulting in the formation of the potently cytotoxic filamentous structures 116. Factors affecting tau hyperphosphorylation are not fully understood and in fact, it has been suggested that tau pathology can be triggered by different mechanisms, dependent and/or independent of Aβ.

Being aging the main risk factor for late‐onset AD and brain aging marked by mitochondrial bioenergetic deficits, defect in ROS scavenging and increase in ROS production (reviewed in: 123, 138, chronic oxidative stress has been suggested as a critical factor for hyperphosphorylation of tau in AD neurons. In fact, this mechanistically links mitochondrial oxidative stress with AD onset and progression.

As referred above, tau overexpression and phosphorylation have been linked to the inhibition of mitochondrial transport along the microtubules 73, 197, 203, 207. In fact, tau inhibits the transport of APP into axons and dendrites, and this inhibition causes the accumulation of APP in the cell body 136, 203. Moreover, besides abnormal distribution of mitochondria in AD neurons, it has been suggested that Aβ and tau, in an independent and/or synergistic way(s), lead to pathological deterioration of mitochondria in AD by impairing multiple mitochondrial‐related pathways, including bioenergetics and quality control (reviewed in: 74, 181). Accordingly, N‐terminal truncation of tau has been detected in cellular and animal AD models, as well as in synaptic mitochondria and cerebrospinal fluids (CSF) from human AD subjects 7, 8, 51, 159, 182, 187. This fragment is neurotoxic in primary cultured neurons 9, compromising mitochondrial respiratory and energy‐generating systems 12, 119, 185 and leading to mitochondrial potential loss and oxidative stress 170. Moreover, tau oligomers also seem to participate in the activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway 119. Concomitantly to bioenergetic deficits and synaptic damage, mitochondrial dynamics abnormalities toward a fragmented profile 135, 170 and an extensive autophagic clearance of mitochondria (mitophagy) 52 also seem to be associated with tau pathologies.

Overall, hallmarks of AD seem to interfere with mitochondrial function, impairing, at least in part, neuronal energetic and respiratory chain and contributing to the supra physiological generation of ROS, oxidative damage and activation of neuronal apoptosis. Moreover, mitochondrial dysfunction also seems to exacerbate AD hallmarks in a vicious circle. Specific alterations of mitochondrial bioenergetics and consequent raise in ROS production, as well as the disruption of mitochondrial quality control systems in primary neuron culture, brain tissue from AD patients and transgenic AD models will be detailed below.

Energy‐metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in AD

Decreased brain metabolism is one of the earliest features of AD. In fact, the degree of cognitive impairment in AD brains has been linked to the extent of mitochondrial dysfunction 68 and several reviews have already addressed the involvement of mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of AD 29, 36, 49, 53, 80, 81, 92, 104. Generically, it is clear the emerging relevance of these organelles as important mediators of AD pathological events and as attractive targets to pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions against neurodegeneration.

Several mitochondrial mechanisms are affected in AD. Briefly, AD transgenic models and postmortem AD brain human studies reported several defects in mitochondrial bioenergetics in AD that culminate in decreased ATP synthesis, namely impairments to the enzymatic activity of the protein complexes of the ETC, Ca2+ deregulation, and alterations in antioxidant enzymatic activity and increased ROS production (even before the appearance of Aβ and tau tangles) 92, 164, 193, 241, 243. In this context, Yao et al 241 found clear signs of mitochondrial dysfunction evidenced by the decline in OXPHOS activity, pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and cytochrome c oxidase (COX) regulatory enzymes in a female triple transgenic Alzheimer's mice (3xTg‐AD) model. Moreover, these were accompanied by increased H2O2 production and lipid peroxidation. Similar results were obtained by Correia et al 50 in Wistar male rats after 5 weeks of intracerebroventricular Streptozotocin injection. Altered expression and activity of PDH, COX, isocitrate dehydrogenase and α‐ketoglutarate dehydrogenase were also found in fibroblasts from AD patients and postmortem AD brain tissue 40, 151. Also, the voltage dependent anion channel VDAC, a major component of the outer mitochondrial membrane that regulates ion fluxes and metabolites, seems to be impaired because of oxidative damage in different AD models 78. Moreover, evidence from AD postmortem brains 25 showed a decrease in ATP levels and reduced respiratory chain complexes I, III, IV and V activity and content. Studies from different independent groups also highlighted mitochondrial impairment and oxidative damage in cell lines expressing mutant APP 231, 232, Aβ treated mammalian cells 71 and primary neurons from AD transgenic mice 31, 32.

Importantly, the increased level of mitochondrial Aβ binding to alcohol dehydrogenase (ABAD) in 3xTg‐AD female mice correlated to increased generation of mitochondrial free radicals 238. Manczak and colleagues 132 found an increase in H2O2 and a decrease in COX activity in an young APP transgenic mice model (Tg2576) prior to the appearance of Aβ plaques suggesting that oxidative stress is an early event in AD pathophysiology. Collectively, the data suggest that significant mitochondrial bioenergetics dysfunction coupled with increased oxidative stress contributes to the overproduction of Aβ and early AD pathogenesis. In line, Resende et al 184 reported, in an in vivo model of AD, decreased levels of glutathione and vitamin E and increased activity of the antioxidant enzymes glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) concomitant with increased lipid peroxidation. These alterations were reported during the Aβ oligomerization period, before the appearance of Aβ plaques and NFTs, suggesting that oxidative stress occurs early in AD development. By using a model of sporadic AD not associated with overexpression of familial AD‐associated mutant genes, Melov et al 145 showed that a deficiency in manganese‐dependent superoxide dismutase (Mn‐SOD) exacerbated the amyloid burden and increased the levels of phosphorylated tau, which suggest that oxidative stress from mitochondrial dysfunction promotes AD‐like pathology. In fact, cumulative oxidative lesions in mtDNA occur during the aging process and are also a prominent feature in AD. Postmortem AD brains exhibited a loss of integrity, including a decreased in mtDNA copy number and increased number of deletions and mutations 54, 125. This AD‐associated mtDNA damage can affect protein expression, including mitochondrial‐encoded genes of OXPHOS complexes leading to impairments in mitochondrial metabolism and oxidative stress (reviewed in: 181). Concomitantly, AD‐associated mitochondrial dysfunction and increased oxidative stress likely cause further loss of calcium homeostasis and the activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, mitochondrial fragmentation and abnormal distribution within the neurons (reviewed in: 233). The gradual and chronic accumulation of oxidation products can compromise brain cell structure and its constituents, particularly mitochondrial structure and function, which ultimately result in neuronal death 150.

Importantly, Grimm et al 95 pointed out that the vast majority of studies have been performed on cellular and animals models based on mutation found in familiar AD cases. Bearing in mind that, at least among the oldest people, dementia severity is dissociated to Aβ and tau neuropathology, the “Inverse Warburg hypothesis” postulate that sporadic AD is a metabolic disease initiated by an age‐related mitochondrial dysregulation 60, 62, 63. Moreover, Demetrius and Driver 61 highlighted that understanding sporadic AD as a metabolic disease will help to promote effective metabolic‐based therapeutic interventions, including exercise and healthy dietary habits.

Mitochondrial quality control alterations in AD

Mitochondrial dynamics is critical for the maintenance of mitochondrial integrity. Fission enables the renewal, redistribution and proliferation of mitochondria, whereas fusion events allow the interaction, communication and mtDNA exchange between organelles 38. Therefore, mitochondrial dynamics has been proposed as an important mechanism able to attenuate mtDNA mutation within the mitochondrial population. In fact, disruption in mitochondrial dynamics and abnormal mitophagy has been extensible reported in AD brains 41.

Altered expression of mitochondrial fission and fusion‐related genes, which in turn leads to an increase in mitochondrial fragmentation and abnormal mitochondrial dynamics were observed in mouse neuroblastoma cells incubated with Aβ peptide, AD transgenic mice and postmortem brain specimens from AD patients 31, 133, 135. Moreover, evidence from cells harboring mutant human APP showed increased mitochondrial network fragmentation and abnormal distribution within the cells 206, 231. Similarly, in HEK and M17 neuroblastoma cells overexpressing Swedish‐type mutant APP (APPsw), mitochondria were extensively fragmented and abnormally distributed 124, 232. These alterations were, at least in part, mediated by altered expression of dynamin‐related protein 1 (Drp1), a regulator of mitochondrial fission and distribution, because of elevated oxidative and/or Aβ‐induced stress 230. Importantly, it has been also suggested that AD disturbed mitochondrial fission‐fusion dynamics may contribute to impaired mitochondrial transport within the neurons 107, 223, 231, which could lead to mitochondrial depletion from axons and dendrites and, subsequently, synaptic loss.

Generally, disturbed mitochondrial fusion/fission activity observed in vitro and in AD patient's brains leads mitochondria to a fragmented phenotype and likely interferes with mitochondrial motility and mitophagy, thereby compromising mitochondrial quality control. Aberrant mitochondrial shape, integrity and distribution unequivocally affect the bioenergetic role of these organelles. Furthermore, mitochondrial bioenergetics deficits are linked with the supra‐physiological production of ROS and these products are known to augment even more mitochondrial pathology in AD brains.

Although mitochondrial dynamics changes may contribute to alterations in mitochondrial density and mass, changes in mitochondrial biogenesis can also impact these mitochondrial parameters. Shaerzadeh et al 196 showed that after an Aβ injection in hippocampal CA1 area, not only mitochondrial fission process increased but also mitochondrial biogenesis was severely affected. In fact, expression levels of mitochondrial biogenesis‐related proteins, such as PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC‐1α), nuclear respiratory factors1/2 (NRF1/2) and mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) were significantly decreased in both AD hippocampal tissue and APPsw M17 cells 232. Decreased mitochondrial biogenesis was also found in Aβ transgenic AD mice 33. These findings suggest that impaired mitochondrial biogenesis may be, at least in part, related to mitochondrial dysfunction in AD 169, 199. In this context, St‐Pierre et al 208 suggested that the apparent ability of PGC‐1α to increase mitochondrial ECT activity while stimulating antioxidant enzymes induction makes this an almost ideal protein to control or limit the damage that has been associated with the defective mitochondrial function seen in AD.

THE NEUROPROTECTIVE EFFECT OF PHYSICAL EXERCISE AGAINST AD

Evidence has repeatedly demonstrated that physical exercise, besides improving general health, has a specific positive impact on brain health 151 and can be an effective strategy to prevent and counteract neurodegenerative diseases 3, 94, 242. In fact, it is well established that physical exercise improves cognitive function 57, 153, 178, 225, 242, as well as attention, memory, reaction time, language, visual‐spatial and executive function 202. Moreover, physical exercise has been linked with a lower risk of cognitive impairment and is generally associated with behavioral‐related improvements in patients with neurodegenerative diseases 138.

Exercise‐induced alterations in cognition are potentially important in the context of AD improving patients’ quality of life. The general improvements in brain function promoted by physical exercise seem to be related to alterations in brain structure 1, 77, 178. These adaptations induced by exercise include the increased hippocampal neurogenesis 44 and volume 77, 163, the increase of synaptic plasticity 47, 179, the increase of brain blood flow 127 and the decrease of age‐related atrophy in different brain areas 47. Furthermore, some of the neurobiological mechanisms responsible for the beneficial effects of physical exercise in brain performance appear to be related to alterations at cellular level. Physical exercise induces an increase in the synthesis and release of neurotrophins and growth factors 127, which include brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) 75, insulin‐like growth factor‐1 (IGF‐1) and vascular endothelial growth factor (EGF) 179. The modulation of these neuromediators seems to improve the survival and growth of different neuronal subtypes 39, 102.

Besides these positive effects in brain function, physical exercise recently emerged as the most effective way to prevent and counteract neurodegenerative diseases 3, including AD 157. However, the volume, intensity and duration of physical exercise are still unclear and under debate. Physical exercise has a positive effect in some of the most characteristic signs of AD, generally through the regulation of oxidative stress‐related mechanisms on the brain 140, 174, 175, increased blood flow and metabolism 59, and especially decrease of cortical formation and accumulation of Aβ 2, 174, 175, 216. Moreover, some of the mechanisms through which exercise has a positive impact in AD appear to involve improvement of mitochondrial function. Because of the relevance of mitochondria on brain metabolism and its involvement on AD pathology, mitochondria has been considered a central target for pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions against the onset and progression of AD, including physical exercise. Nevertheless, the role of physical exercise against AD‐related mitochondrial dysfunction is not fully understood. The next topic will highlight existing studies approaching the role of mitochondria on the cross‐tolerance phenomena between exercise and AD.

Oxidative stress‐related adaptations induced by physical exercise

There are a number of ROS sources in neuronal cells; however, the mitochondrial ETC is one of the most important. The damaging potential of mitochondrial ROS is the core of the “mitochondrial free radical theory of aging.” Briefly, it is suggested that the accumulation of molecular damage over time induced by mitochondrial ROS lead to impairment function of respiratory chain, which in turn triggers further accumulation of ROS. This process leads to energy depletion and ultimately to cellular degeneration and death. However, accumulating evidence has revealed that ROS are not simply byproducts of mitochondrial metabolism. Instead, moderate levels of ROS have been associated with important redox signaling pathways in the healthy cell 118. Although this renewed perspective of ROS physiology has been increasingly recognized, many studies have clearly demonstrated that excessive amounts of ROS are also related to several mitochondrial diseases and neurodegenerative disorders, including AD.

Physical exercise can significantly increase the metabolic rate and is accompanied by ROS generation. Therefore, a simple question comes up: how ROS produced during physical exercise can be associated with exercise‐induced health‐promoting benefits? Bearing this in mind, it is important to distinguish between pathological ROS accumulation (reported during the aging process or AD pathology) and moderate/short‐term ROS levels associated to physical exercise. Several reports, elegantly reviewed by Radak et al 174, suggested that regular exercise promotes increased brain function and protection by activating a wide range of redox signaling pathways. As described above, neuronal cells are very sensitive to oxidative stress because of their high metabolic rate, high content of oxidizable substrates and low antioxidant capacity. It is, however, accepted that redox‐sensitive signaling pathways triggered by chronic exercise can selectively regulate the activity of brain mitochondrial antioxidant (for review see 174). Improvements in brain enzymatic antioxidant system and consequent modulation of oxidative damage can delay or even prevent redox alterations linked to aging and neurodegenerative disorders, such as AD 174. This can be achieved not only by the induction of the antioxidant defense system, which reduces ROS levels or severity, but also because long‐term adaptations to exercise can directly diminish ROS production 172. Nevertheless, physical exercise triggers a complex adaptive response that can be controversial. In fact, the high heterogeneity among exercise protocols with distinct intensity, volume and duration along with different age and animal characteristics leads to different physiological, biochemical and functional adaptations, namely in the brain 138. Moreover, gender‐specific adaptations related with exercise can be found 84, 87, 126, which may explain distinct exercise modulatory profiles on oxidative stress markers in the same organ.

Mechanisms behind exercise‐dependent regulation of the brain redox state pointed out that regular moderate exercise may activate specific redox‐sensitive transcription factors, culminating in an overall adaptive response with direct consequences on oxidative damage 34, 141, 171, 209.

Knowing that, as previously mentioned, disturbances in mitochondrial machinery and redox signaling are critical events leading to AD pathology, the ability of endurance exercise to increase antioxidant potential highlights the possible role of regular exercise as an important countermeasure to mitigate many neuropathophysiological conditions. Therefore, despite the diversity in methodology, the vast majority of exercise studies dealing with AD models report significant improvements in the antioxidant capacity. Table 1 provides a list of recent studies and summarizes major findings.

Table 1.

Effects of physical exercise on antioxidant capacity and oxidative stress‐induced damage in AD animal models.

| Tg line/strain | Sex | Tissue | Intervention | Main changes in antioxidant system promoted by exercise | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSE/APPsw | Not shown | Brain |

Treadmill 16 weeks, 13.2 m/min, 1 h/day, 5 days/week |

↑ Cu/Zn‐SOD, ↑ CAT | Um et al 220 |

| Tg‐NSE/htau23 | ♀♂ | Brain |

Treadmill 3 month, 12 or 19 m/min, 1 h/day, 5 days/week |

↑ Cu/Zn‐SOD, ↓ Mn‐SOD ↑ CAT | Leem et al 122 |

| NSE/APPsw | Not shown | Brain |

Treadmill 16 weeks, 13.2 m/min, 1 h/day, 5 days/week |

↑ Cu/Zn‐SOD, ↑ CAT | Cho et al 42 |

| 3xTg‐AD | ♀♂ | Cortex |

Treadmill 5 weeks, maximum: 4.2 m/min, 30 min/day, 5 days/week |

♀: ↓ GSH, ↓ GSSG, ∼ GPX, ∼ Cu/Zn‐SOD, ∼ Mn‐SOD, ∼ LPO ♂: ∼GSH, ∼GSSG, ∼ GPx, ∼ Cu/Zn‐SOD, ∼ Mn‐SOD, ↓ LPO |

Gimenez‐Llort et al 87 |

| Tg‐NSE/hPS2m | Not shown | Hippocampus |

Treadmill 12 weeks, 12 m/min, 1 h/day, 5 days/week |

↑ Cu/Zn‐SOD, ↑ Mn‐SOD | Um et al 219 |

| 3xTg‐AD | ♀♂ | Cortex |

RUN 1 and 6 months |

♀:↓ LPO, ∼GSSG, ∼GSH, ↑ GPx ∼ Cu/Zn‐SOD, ∼ Mn‐SOD ♂:∼ LPO, ↑ GSSG, ↓ GSH, ↑ GPx, ↓ Cu/Zn‐SOD, ∼ Mn‐SOD |

Garcia‐Mesa et al 84 |

| 3xTg‐AD | ♂ | Cortex |

RUN 6 months |

↑ GSH, ∼GSSG, ↑ GPx, ∼ Gr, ∼ Cu/Zn‐SOD, ↑ Mn‐SOD, ↓ LPO | Garcia‐Mesa et al 83 |

| C57bl/6 (Aβ25‐35 icv injection) | ♂ | Hippocampus |

RUN 12 days |

↓ Oxidative stress marker, ↓ Antioxidant stress marker | Wang et al 229 |

| APP/PS1 | Not shown | Hippocampus |

RUN 6 weeks |

∼ Oxidative stress marker, ∼ Antioxidant stress marker | Xu et al 237 |

| 3xTg‐AD | ♀ | Hippocampus |

RUN 3 months |

∼ Mn‐SOD, ∼ Catalase, ∼ GPx | Garcia‐Mesa et al 85 |

| APP/PS1 | ♂ | Hippocampus |

Treadmill 20 weeks, 11 m/min, 30 min/day, 5 days/week |

↓ ROS, ↑ Mn‐SOD (activity), ↑ GPx (activity) | Bo et al 23 |

| Tg601 | ♀ | Brain |

Treadmill 3 weeks, 10 m/min, 30 min/day, 5 days/week |

↑ LPO | Elahi et al 76 |

| 3xTg‐AD | ♀ | Cortex |

RUN 3 months |

↑ Cu/Zn‐SOD, ∼ Mn‐SOD ↓ GSSH, ↓ GPx, ↓GR, ↓ LPO | Garcia‐Mesa et al 82 |

CAT, catalase; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; GR, glutathione reductase; GSH, reduced glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; icv, intracerebroventricular; LPO, lipid peroxidation; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RUN, running wheel; SOD, superoxide dismutase; ↓, decrease; ↑, increase.

Concerning antioxidant enzymes, SOD and catalase activities are reduced in the brains of AD animal models and AD brains patients 122, 195, 220. However, some studies have highlighted that regular exercise increases such antioxidant enzymes in young rat and mice brains 83. Upregulation of both expression and activity of SOD and catalase were also reported in AD mice models submitted to chronic exercise 42, 122, 219, 220. Moreover, an improvement in the antioxidant defense system associated with physical exercise was further noticeable when combined with antioxidant supplementation in transgenic mice models of AD 42, 83.

On the other hand, data suggest that the overall levels of oxidative damage to lipids, proteins and DNA are elevated in AD brains 93. In fact, it is well established that oxidative stress‐related impairment increases with the mouse age and the AD‐like pathology severity 85. Brain tissue analysis from 12‐month‐old 3xTg‐AD mice showed higher levels of oxidative damage than those from their younger healthy counterparts 83. In contrast, a bulk of studies documented that endurance exercise interventions decrease lipid peroxidation in rat brain 172. However, inconsistent effects of physical exercise regarding lipid peroxidation have been observed in AD models. Moreover, Elahi et al 76 did not find a decrease in lipid peroxidation levels in aged mice after a short‐term treadmill running. As several redox‐dependent signaling pathways and physiological adaptations are activated by a mild increase in ROS generation 131, 173, redox imbalance during a short‐term exercise program seems to be beneficial and prepare the cellular environment for the subsequent stimulus. Therefore, repetitive moderate levels of lipid peroxidation could be an important signal to remodel cellular membranes despite the limited repair of lipid peroxidation 176. As stated before, mitochondrial DNA is localized near ROS production sites, which may cause mtDNA mutations and delections. Furthermore, mtDNA has a limited capacity for DNA repair and also lacks histones. Therefore, cumulative oxidative stress‐related lesions in mtDNA are reported during the aging process and are a prominent feature in AD. Postmortem analysis of AD patient's brains exhibit decreased in mtDNA copy number 55 and increased number of delections and mutations that are correlated with mitochondrial impairment 54. Interestingly, endurance training has been shown to attenuate or mitigate several metabolic alterations in the cortex of mtDNA mutator mouse, an animal model that mimics physiological aging 45. Also, after a long‐term treadmill exercise training program, mtDNA levels were preserved in 3xTg‐AD mice, which suggest that mitochondria are adequately protected against ROS‐induced mtDNA depletion 83.

The activities of oxidative damage enzymes can be considered as a second line of antioxidant defense. Mitochondrial 8‐oxoguanine DNA glycosylase‐1 (OGG1) activity, an enzyme responsible for the removal of oxidatively damaged bases from mtDNA, was found to be decreased in some regions of AD brains 198. Consistently, physical exercise was able to increase mtDNA repair by increasing mtOGG1 content and function in APP/SP1 animals, a transgenic mice model expressing AD phenotypes, including Aβ deposits and behavioral deficits 23. These findings suggest that exercise training was able to upregulate mtDNA repair capacity, which in turn attenuates AD‐related mitochondrial impairment and phenotypic degradation 23. It has been suggested that OGG1 expression and activity may be influenced by intracellular redox status. Reduced mitochondrial glutathione is thought to be important as a posttranslational mechanism to maintain mitochondrial OGG1 active 43. Moreover, a protein–protein interaction between MnSOD and OGG1 has been suggested for OGG1 DNA repairing activity 24. In this context, Bo et al 23 showed that 20 weeks of endurance training increased MnSOD and GPX activities, being this ameliorated modulation of mitochondrial redox status a potential mechanism involved in exercise‐induced mitochondrial OGG1 activity.

Severe altered redox status and mitochondrial malfunction are also believed to interfere with calcium homeostasis, which leads to increased mitochondrial susceptibility to calcium induced mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) and depolarization, and ultimately to the release of signaling proteins from mitochondria to the cytoplasm that in turn activate apoptotic cell death 154, 214. Chronic endurance training augmented the resistance to calcium‐induced mPTP opening and decreased apoptotic markers in mouse brain cortex highlighting the relevant protective effect of exercise on events leading to mitochondrial degeneration and cell death 139. Accordingly, a decrease in some pro‐apoptotic proteins, including Bax, cytochrome c, caspase 3 and 9 was reported in NSE/APPsw transgenic mice model of AD after endurance training 42, 220. Moreover, decreased levels of caspase 3 and 9 and increased Bcl‐2 protein content were also reported in NSE/PS2m transgenic mice model of AD engaged in an endurance training regimen 219. As extensive neuron loss because of apoptosis is a common feature in AD brain, exercise might be an effective strategy for extending AD neuron survival. In addition, endurance training also upregulates the levels of chaperones in brain tissue, particularly heat shock proteins (HSPs) facilitating protein import, folding and assembly. In fact, an increase in HSP‐70 content was found after exercise in AD models 220. HSP‐70s are highly conserved proteins that protect brain cells against excitotoxic and oxidative injury and it is likely that exercise‐induced HSP overexpression is mediated by redox‐signaling pathways 79. These results suggest that exercise training can mitigate neuronal cell apoptosis implicated in the pathogenesis of AD.

Mitochondrial bioenergetics modulation induced by physical exercise

Mitochondrial adaptations are crucial in exercise‐induced neuroprotection. In opposition to contractile‐dependent effects on skeletal and cardiac muscles, physical exercise adaptations in brain tissue are associated to systemic alterations during and after exercise.

Despite some inconsistencies related with the characteristics of the exercise protocols [Stranahan et al 209], reduced levels of intracellular Aβ and tau phosphorylation have been reported after an exercise intervention in mouse models of AD (reviewed in 209), which suggest that physical exercise can regulate basic mechanisms underlying AD.

The BDNF have been positively associated with structural and functional plasticity of the central nervous system. In fact, BDNF signaling have been linked with healthy brain mitochondria by several distinct mechanisms, namely: (i) improving glucose transport and respiratory coupling efficiency of synaptic mitochondria, (ii) upregulating antioxidant enzymes, (iii) mediating PGC‐1α‐induce mitochondrial biogenesis, and (iv) preventing neuronal apoptosis (reviewed in 137). Moreover, mitochondrial transport and distribution seems to play an essential role in BDNF‐mediated synaptic transmission 210. However, the expression of this neurothrophin seems to be modulated both by physical activity and by AD in opposite directions 140. Bearing this in mind, it is important to highlight that BDNF plasma levels were positively associated with physical activity levels of AD patients and that an acute bout of aerobic exercise seems to be sufficient to increase BDNF plasma levels in patients with AD 46. Therefore, BDNF‐associated mechanisms for improving neuronal bioenergetics might explain, at least in part, the effectives of exercise counteracting AD mitochondrial frailties.

Mitochondrial mechanisms underlying the protective phenotype induced by exercise in brain physiology are still elusive. Nevertheless, some studies report that exercise‐induced brain mitochondrial bioenergetics adaptations include increased content and/or activity of several enzymes involved in aerobic energy production 66, 67, 112, increased activity or content of OXPHOS complexes 139, 152 and improved mitochondrial ability to produce energy 139. These are important metabolic adaptations on the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation system that can result in improved ability to oxidize substrates and increased rate of mitochondrial ATP synthesis. On the other hand, AD has been associated with defects in mitochondrial electron transport chain enzymes. In fact, reductions in mitochondrial complex I and complex IV efficiency have been described in AD 134, 144. Since exercise modulates both these mitochondrial respiratory chain components 152, this might also contribute to counteract the development and symptoms of this pathology 138. Bo et al 23 showed an increase in mitochondrial complex I, IV and V activities in the APP/SP1 mice model of AD after an endurance training regimen. Although García‐Mesa et al 83 did not found an increase in protein complexes content with exercise, OXPHOS complexes levels recovered to levels of non‐transgenic mice with the combined treatment of exercise plus antioxidant supplementation. Still, these authors did not report complexes activity but rather expression levels, which might explain, at least in part, the results.

Sirtuin‐3 (SIRT3) is a mitochondrial deacetylase that modulates the activity of several mitochondrial proteins involved in metabolism. SIRT3 participates in the regulation of mitochondrial energy homeostasis and biogenesis. Additionally, SIRT3 deacetylates and directly activates Mn‐SOD and increases NADPH levels, which also increases the pool of available GSH 14, 190. Moreover, upregulation of SIRT3 can reduce ROS production and therefore reduces apoptosis (or increase neuronal survival) and mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) induction 72. In the context of neurodegenerative diseases, SIRT3 levels have been shown to be depleted in APP/PS1 models, suggesting a role of this protein in the development of AD via mitochondrial dysfunction 240. In contrast, an increase in SIRT3 protein content and in oxidative phosphorylation coupling was observed in the hippocampus of APP/SP1 AD mice model after endurance training 23.

Impact of physical exercise in mitochondrial biogenesis and quality control

Even though some studies were already published on the impact of physical exercise and AD per se on mitochondrial biogenesis and quality control, the possible role of exercise against these AD‐related mechanisms remains unclear. The proper balance of mitochondrial biogenesis and clearance/renewal is a key determinant to maintain the overall mitochondrial physiology within the neurons 86. Therefore, the regulation and stimulation of these processes by exercise models may translate into positive outcomes on AD brain mitochondrial metabolic activity. Physical exercise, particularly endurance training, has been suggested to stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis through activation of silent information regulator 1 (SIRT 1) and PGC‐1α in the hippocampus 205, 226. This is particularly relevant because both genes are downregulated in AD conditions 105. Additionally, an improvement in brain cortex mitochondrial function, accompanied by increased biogenesis, fusion of healthy mitochondria and segregation of damaged mitochondria was reported after endurance training 139. By increasing the healthy mitochondrial network, exercise possibly interferes on mitochondrial signaling pathways preventing the migration of damaged components into more fit mitochondria. These adaptations reinforce the idea that exercise may improve overall mitochondrial function, thus contributing to mitigate the development and symptoms associated with AD neurodegenerative process.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

With the increase in life expectancy, neurodegenerative diseases and other common chronic diseases are becoming considerable prevalent in elderly people. Therefore, AD is a critical issue to be addressed in the context of science and research. Although research continues to make outstanding progress in the understanding of AD etiology, effective pharmacological interventions failed to be identified. Through the modulation of multiple mechanisms related with brain health, exercise has emerged as a possible non‐pharmacological strategy, likely to contribute to a protective phenotype against AD. At least in part, mitochondria are an important target organelle involved in physical exercise‐related adaptations. Through the interaction with mitochondrial physiological processes, including redox modulation bioenergetics improvement, increased resistance to mPTP and decreased apoptotic signaling, activation of mitochondrial biogenesis, and the modulation of dynamics and autophagy, the role of physical exercise has been reinforced as a preventive and/or therapeutic strategy to attenuate the negative effects of AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant of Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) to J.M. (POCI‐01‐0145‐FEDER‐016690 ‐ PTDC/DTP‐DES/7087/2014) and to the Research Center in Physical Activity, Health and Leisure (CIAFEL) (UID/DTP/00617/2013). T.B. and I.A. are also supported by doctoral and post‐doctoral FCT grants, SFRH/BD/93281/2013 and SFRH/BPD/108322/2015, respectively.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Åberg MA, Pedersen NL, Torén K, Svartengren M, Bäckstrand B, Johnsson T et al (2009) Cardiovascular fitness is associated with cognition in young adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106:20906–20911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adlard PA, Perreau VM, Pop V, Cotman CW (2005) Voluntary exercise decreases amyloid load in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci 25:4217–4221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahlskog JE, Geda YE, Graff‐Radford NR, Petersen RC (2011) Physical exercise as a preventive or disease‐modifying treatment of dementia and brain aging. Mayo Clin Proc 86:876–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ahlskog JE, Geda YE, Graff‐Radford NR, Petersen RC (eds) (2011) Physical Exercise as a Preventive or Disease‐Modifying Treatment of Dementia and Brain Aging. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Elsevier: New York. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Allen R, Tresini M (2000) Oxidative stress and gene regulation. Free Radic Biol Med 28:463–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alonso AD, Di Clerico J, Li B, Corbo CP, Alaniz ME, Grundke‐Iqbal I et al (2010) Phosphorylation of tau at Thr212, Thr231, and Ser262 combined causes neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem 285:30851–30860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Amadoro G, Corsetti V, Sancesario GM, Lubrano A, Melchiorri G, Bernardini S et al (2014) Cerebrospinal fluid levels of a 20–22 kDa NH2 fragment of human tau provide a novel neuronal injury biomarker in Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. J Alzheimer's Dis 42:211–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Amadoro G, Corsetti V, Stringaro A, Colone M, D'Aguanno S, Meli G et al (2010) A NH2 tau fragment targets neuronal mitochondria at AD synapses: possible implications for neurodegeneration. J Alzheimer's Dis 21:445–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Amadoro G, Serafino A, Barbato C, Ciotti M, Sacco A, Calissano P et al (2004) Role of N‐terminal tau domain integrity on the survival of cerebellar granule neurons. Cell Death Differ 11:217–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anandatheerthavarada HK, Biswas G, Robin M‐A, Avadhani NG (2003) Mitochondrial targeting and a novel transmembrane arrest of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein impairs mitochondrial function in neuronal cells. J Cell Biol 161:41–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Area‐Gomez E, de Groof AJ, Boldogh I, Bird TD, Gibson GE, Koehler CM et al (2009) Presenilins are enriched in endoplasmic reticulum membranes associated with mitochondria. Am J Pathol 175:1810–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Atlante A, Amadoro G, Bobba A, De Bari L, Corsetti V, Pappalardo G et al (2008) A peptide containing residues 26–44 of tau protein impairs mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation acting at the level of the adenine nucleotide translocator. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)‐Bioenerg 1777:1289–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Avila J, Lucas JJ, Perez M, Hernandez F (2004) Role of tau protein in both physiological and pathological conditions. Physiol Rev 84:361–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bell EL, Guarente L (2011) The SirT3 divining rod points to oxidative stress. Mol Cell 42:561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ben‐Menachem‐Zidon O, Ben‐Menahem Y, Ben‐Hur T, Yirmiya R (2014) Intra‐hippocampal transplantation of neural precursor cells with transgenic over‐expression of IL‐1 receptor antagonist rescues memory and neurogenesis impairments in an Alzheimer's disease model. Neuropsychopharmacology 39:401–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bereiter‐Hahn J, Jendrach M (2010) Chapter one‐mitochondrial dynamics. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 284:1–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bernardo TC, Cunha‐Oliveira T, Serafim TL, Holy J, Krasutsky D, Kolomitsyna O et al (2013) Dimethylaminopyridine derivatives of lupane triterpenoids cause mitochondrial disruption and induce the permeability transition. Bioorg Med Chem 21:7239–7249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bezprozvanny I, Mattson MP (2008) Neuronal calcium mishandling and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci 31:454–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Billups B, Forsythe ID (2002) Presynaptic mitochondrial calcium sequestration influences transmission at mammalian central synapses. J Neurosci 22:5840–5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Binder LI, Frankfurter A, Rebhun LI (1985) The distribution of tau in the mammalian central nervous system. J Cell Biol 101:1371–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Biscaro B, Lindvall O, Tesco G, Ekdahl CT, Nitsch RM (2012) Inhibition of microglial activation protects hippocampal neurogenesis and improves cognitive deficits in a transgenic mouse model for Alzheimer's disease. Neurodegener Dis 9:187–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bloom GS (2014) Amyloid‐β and tau: the trigger and bullet in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. JAMA Neurol 71:505–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bo H, Kang W, Jiang N, Wang X, Zhang Y, Ji LL (2014) Exercise‐induced neuroprotection of hippocampus in APP/PS1 transgenic mice via upregulation of mitochondrial 8‐oxoguanine DNA glycosylase. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2014:834502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bonatto D (2007) A systems biology analysis of protein‐protein interactions between yeast superoxide dismutases and DNA repair pathways. Free Radic Biol Med 43:557–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bosetti F, Brizzi F, Barogi S, Mancuso M, Siciliano G, Tendi EA et al (2002) Cytochrome c oxidase and mitochondrial F1F0‐ATPase (ATP synthase) activities in platelets and brain from patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 23:371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Braak F, Braak H, Mandelkow E‐M (1994) A sequence of cytoskeleton changes related to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads. Acta Neuropathol 87:554–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brandt R, Hundelt M, Shahani N (2005) Tau alteration and neuronal degeneration in tauopathies: mechanisms and models. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)‐Mol Basis Dis 1739:331–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Breen K, Bruce M, Anderton B (1991) Beta amyloid precursor protein mediates neuronal cell‐cell and cell‐surface adhesion. J Neurosci Res 28:90–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cabezas‐Opazo FA, Vergara‐Pulgar K, Pérez MJ, Jara C, Osorio‐Fuentealba C, Quintanilla RA (2015) Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015:509654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cai Q, Tammineni P (2016) Alterations in mitochondrial quality control in Alzheimer's disease. Front Cell Neurosci 10:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Calkins MJ, Manczak M, Mao P, Shirendeb U, Reddy PH (2011) Impaired mitochondrial biogenesis, defective axonal transport of mitochondria, abnormal mitochondrial dynamics and synaptic degeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Hum Mol Genet 20:4515–4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Calkins MJ, Reddy PH (2011) Amyloid beta impairs mitochondrial anterograde transport and degenerates synapses in Alzheimer's disease neurons. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812:507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Calkins MJ, Reddy PH (2011) Assessment of newly synthesized mitochondrial DNA using BrdU labeling in primary neurons from Alzheimer's disease mice: implications for impaired mitochondrial biogenesis and synaptic damage. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812:1182–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Camiletti‐Moiron D, Aparicio VA, Aranda P, Radak Z (2013) Does exercise reduce brain oxidative stress? A systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports 23:e202–e212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Caspersen C, Wang N, Yao J, Sosunov A, Chen X, Lustbader JW et al (2005) Mitochondrial Abeta: a potential focal point for neuronal metabolic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Faseb J 19:2040–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cavallucci V, Ferraina C, D'Amelio M (2013) Key role of mitochondria in Alzheimer's disease synaptic dysfunction. Curr Pharm Des 19:6440–6450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cha M‐Y, Han S‐H, Son SM, Hong H‐S, Choi Y‐J, Byun J et al (2012) Mitochondria‐specific accumulation of amyloid β induces mitochondrial dysfunction leading to apoptotic cell death. PLoS One 7:e34929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chan DC (2006) Mitochondria: dynamic organelles in disease, aging, and development. Cell 125:1241–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chan KL, Tong KY, Yip SP (2008) Relationship of serum brain‐derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and health‐related lifestyle in healthy human subjects. Neurosci Lett 447:124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chaturvedi RK, Flint Beal M (2013) Mitochondrial diseases of the brain. Free Radic Biol Med 63:1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chen H, Chan DC (2009) Mitochondrial dynamics–fusion, fission, movement, and mitophagy–in neurodegenerative diseases. Hum Mol Genet 18:R169–RR76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cho JY, Um HS, Kang EB, Cho IH, Kim CH, Cho JS et al (2010) The combination of exercise training and alpha‐lipoic acid treatment has therapeutic effects on the pathogenic phenotypes of Alzheimer's disease in NSE/APPsw‐transgenic mice. Int J Mol Med 25:337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Circu ML, Moyer MP, Harrison L, Aw TY (2009) Contribution of glutathione status to oxidant‐induced mitochondrial DNA damage in colonic epithelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med 47:1190–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Clark PJ, Kohman RA, Miller DS, Bhattacharya TK, Brzezinska WJ, Rhodes JS (2011) Genetic influences on exercise‐induced adult hippocampal neurogenesis across 12 divergent mouse strains. Genes Brain Behav 10:345–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Clark‐Matott J, Saleem A, Dai Y, Shurubor Y, Ma X, Safdar A et al (2015) Metabolomic analysis of exercise effects in the POLG mitochondrial DNA mutator mouse brain. Neurobiol Aging 36:2972–2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Coelho FG, Vital TM, Stein AM, Arantes FJ, Rueda AV, Camarini R et al (2014) Acute aerobic exercise increases brain‐derived neurotrophic factor levels in elderly with Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 39:401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Colcombe SJ, Kramer AF, McAuley E, Erickson KI, Scalf P (2004) Neurocognitive aging and cardiovascular fitness: recent findings and future directions. J Mol Neurosci: MN 24:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cook DG, Forman MS, Sung JC, Leight S, Kolson DL, Iwatsubo T et al (1997) Alzheimer's Aβ (1–42) is generated in the endoplasmic reticulum/intermediate compartment of NT2N cells. Nat Med 3:1021–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Correia SC, Santos RX, Cardoso S, Carvalho C, Candeias E, Duarte AI et al (2012) Alzheimer disease as a vascular disorder: where do mitochondria fit? Exp Gerontol 47:878–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Correia SC, Santos RX, Santos MS, Casadesus G, Lamanna JC, Perry G et al (2013) Mitochondrial abnormalities in a streptozotocin‐induced rat model of sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 10:406–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Corsetti V, Amadoro G, Gentile A, Capsoni S, Ciotti M, Cencioni M et al (2008) Identification of a caspase‐derived N‐terminal tau fragment in cellular and animal Alzheimer's disease models. Mol Cell Neurosci 38:381–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Amadoro G, Corsetti V, Florenzano F, Atlante A, Ciotti MT, Mongiardi MP et al (2014) AD-linked, toxic NH2 human tau affects the quality control of mitochondria in neurons. Neurobiol Dis 62:489–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Coskun P, Wyrembak J, Schriner SE, Chen HW, Marciniack C, Laferla F et al (2012) A mitochondrial etiology of Alzheimer and Parkinson disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1820:553–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Coskun PE, Beal MF, Wallace DC (2004) Alzheimer's brains harbor somatic mtDNA control‐region mutations that suppress mitochondrial transcription and replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:10726–10731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Coskun PE, Wyrembak J, Derbereva O, Melkonian G, Doran E, Lott IT et al (2010) Systemic mitochondrial dysfunction and the etiology of Alzheimer's disease and down syndrome dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 20 Suppl 2:S293–S310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cotel MC, Jawhar S, Christensen DZ, Bayer TA, Wirths O (2012) Environmental enrichment fails to rescue working memory deficits, neuron loss, and neurogenesis in APP/PS1KI mice. Neurobiol Aging 33:96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Creer DJ, Romberg C, Saksida LM, van Praag H, Bussey TJ (2010) Running enhances spatial pattern separation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:2367–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. de Brito OM, Scorrano L (2010) An intimate liaison: spatial organization of the endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria relationship. EMBO J 29:2715–2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. de la Torre JC (2002) Vascular basis of Alzheimer's pathogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 977:196–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Demetrius LA, Driver J (2013) Alzheimer's as a metabolic disease. Biogerontology 14:641–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Demetrius LA, Driver JA (2015) Preventing Alzheimer's disease by means of natural selection. J R Soc Interface 12:20140919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Demetrius LA, Magistretti PJ, Pellerin L (2014) Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid hypothesis and the Inverse Warburg effect. Front Physiol 5:522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Demetrius LA, Simon DK (2012) An inverse‐Warburg effect and the origin of Alzheimer's disease. Biogerontology 13:583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Detmer SA, Chan DC (2007) Functions and dysfunctions of mitochondrial dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8:870–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Devi L, Prabhu BM, Galati DF, Avadhani NG, Anandatheerthavarada HK (2006) Accumulation of amyloid precursor protein in the mitochondrial import channels of human Alzheimer's disease brain is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurosci 26:9057–9068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dietrich MO, Andrews ZB, Horvath TL (2008) Exercise‐induced synaptogenesis in the hippocampus is dependent on UCP2‐regulated mitochondrial adaptation. J Neurosci 28:10766–10771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ding Q, Vaynman S, Souda P, Whitelegge JP, Gomez‐Pinilla F (2006) Exercise affects energy metabolism and neural plasticity‐related proteins in the hippocampus as revealed by proteomic analysis. Eur J Neurosci 24:1265–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Dragicevic N, Mamcarz M, Zhu Y, Buzzeo R, Tan J, Arendash GW et al (2010) Mitochondrial amyloid‐β levels are associated with the extent of mitochondrial dysfunction in different brain regions and the degree of cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's transgenic mice. J Alzheimer's Dis 20:535–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Dröge W (2002) Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev 82:47–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Du H, Guo L, Fang F, Chen D, Sosunov AA, McKhann GM et al (2008) Cyclophilin D deficiency attenuates mitochondrial and neuronal perturbation and ameliorates learning and memory in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med 14:1097–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Du H, Guo L, Yan S, Sosunov AA, McKhann GM, Yan SS (2010) Early deficits in synaptic mitochondria in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:18670–18675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Du H, Yan SS (2010) Mitochondrial permeability transition pore in Alzheimer's disease: cyclophilin D and amyloid beta. Biochim Biophys Acta 1802:198–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Dubey M, Chaudhury P, Kabiru H, Shea TB (2008) Tau inhibits anterograde axonal transport and perturbs stability in growing axonal neurites in part by displacing kinesin cargo: neurofilaments attenuate tau‐mediated neurite instability. Cell Motil Cytoskel 65:89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Eckert A, Schmitt K, Götz J (2011) Mitochondrial dysfunction—the beginning of the end in Alzheimer's disease? Separate and synergistic modes of tau and amyloid‐beta toxicity. Alzheimers Res Ther 3:1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Eggermont L, Swaab D, Luiten P, Scherder E (2006) Exercise, cognition and Alzheimer's disease: more is not necessarily better. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 30:562–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Elahi M, Motoi Y, Matsumoto SE, Hasan Z, Ishiguro K, Hattori N (2016) Short‐term treadmill exercise increased tau insolubility and neuroinflammation in tauopathy model mice. Neurosci Lett 610:207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, Basak C, Szabo A, Chaddock L et al (2011) Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:3017–3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ferrer I (2009) Altered mitochondria, energy metabolism, voltage‐dependent anion channel, and lipid rafts converge to exhaust neurons in Alzheimer's disease. J Bioenerg Biomembr 41:425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Fittipaldi S, Dimauro I, Mercatelli N, Caporossi D (2014) Role of exercise‐induced reactive oxygen species in the modulation of heat shock protein response. Free Radic Res 48:52–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Friedland‐Leuner K, Stockburger C, Denzer I, Eckert GP, Muller WE (2014) Mitochondrial dysfunction: cause and consequence of Alzheimer's disease. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 127:183–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Garcia‐Escudero V, Martin‐Maestro P, Perry G, Avila J (2013) Deconstructing mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013:162152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Garcia‐Mesa Y, Colie S, Corpas R, Cristofol R, Comellas F, Nebreda AR et al (2016) Oxidative stress is a central target for physical exercise neuroprotection against pathological brain aging. J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci 71:40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Garcia‐Mesa Y, Gimenez‐Llort L, Lopez LC, Venegas C, Cristofol R, Escames G et al (2012) Melatonin plus physical exercise are highly neuroprotective in the 3xTg‐AD mouse. Neurobiol Aging 33:1124–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Garcia‐Mesa Y, Lopez‐Ramos JC, Gimenez‐Llort L, Revilla S, Guerra R, Gruart A et al (2011) Physical exercise protects against Alzheimer's disease in 3xTg‐AD mice. J Alzheimers Dis 24:421–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Garcia‐Mesa Y, Pareja‐Galeano H, Bonet‐Costa V, Revilla S, Gomez‐Cabrera MC, Gambini J et al (2014) Physical exercise neuroprotects ovariectomized 3xTg‐AD mice through BDNF mechanisms. Psychoneuroendocrinology 45:154–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ghavami S, Shojaei S, Yeganeh B, Ande SR, Jangamreddy JR, Mehrpour M et al (2014) Autophagy and apoptosis dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders. Prog Neurobiol 112:24–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Gimenez‐Llort L, Garcia Y, Buccieri K, Revilla S, Sunol C, Cristofol R et al (2010) Gender‐Specific Neuroimmunoendocrine Response to Treadmill Exercise in 3xTg‐AD Mice. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2010:128354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Gimenez‐Llort L, Mate I, Manassra R, Vida C, De la Fuente M (2012) Peripheral immune system and neuroimmune communication impairment in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1262:74–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Golde TE, Janus C (2005) Homing in on intracellular Abeta? Neuron 45:639–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Gomez‐Ramos P, Asuncion Moran M (2007) Ultrastructural localization of intraneuronal Abeta‐peptide in Alzheimer disease brains. J Alzheimers Dis 11:53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Greenfield JP, Tsai J, Gouras GK, Hai B, Thinakaran G, Checler F et al (1999) Endoplasmic reticulum and trans‐Golgi network generate distinct populations of Alzheimer β‐amyloid peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96:742–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Grimm A, Friedland K, Eckert A (2015) Mitochondrial dysfunction: the missing link between aging and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Biogerontology 16:801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Guo C, Sun L, Chen X, Zhang D (2013) Oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen Res 8:2003–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Hamer M, Chida Y (2009) Physical activity and risk of neurodegenerative disease: a systematic review of prospective evidence. Psychol Med 39:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Hamilton A, Holscher C (2012) The effect of ageing on neurogenesis and oxidative stress in the APP(swe)/PS1(deltaE9) mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res 1449:83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Hamilton LK, Aumont A, Julien C, Vadnais A, Calon F, Fernandes KJ (2010) Widespread deficits in adult neurogenesis precede plaque and tangle formation in the 3xTg mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Neurosci 32:905–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Hansson Petersen CA, Alikhani N, Behbahani H, Wiehager B, Pavlov PF, Alafuzoff I et al (2008) The amyloid beta‐peptide is imported into mitochondria via the TOM import machinery and localized to mitochondrial cristae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:13145–13150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hartmann T, Bieger SC, Brühl B, Tienari PJ, Ida N, Allsop D et al (1997) Distinct sites of intracellular production for Alzheimer's disease Aβ40/42 amyloid peptides. Nat Med 3:1016–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Hayashi T, Rizzuto R, Hajnoczky G, Su T‐P (2009) MAM: more than just a housekeeper. Trends Cell Biol 19:81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Heber S, Herms J, Gajic V, Hainfellner J, Aguzzi A, Rülicke T et al (2000) Mice with combined gene knock‐outs reveal essential and partially redundant functions of amyloid precursor protein family members. J Neurosci 20:7951–7963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Hedskog L, Pinho CM, Filadi R, Rönnbäck A, Hertwig L, Wiehager B et al (2013) Modulation of the endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria interface in Alzheimer's disease and related models. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110:7916–7921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Heyn P, Abreu BC, Ottenbacher KJ (2004) The effects of exercise training on elderly persons with cognitive impairment and dementia: a meta‐analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 85:1694–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Hollenbeck PJ, Saxton WM (2005) The axonal transport of mitochondria. J Cell Sci 118:5411–5419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Hroudová J, Singh N, Fišar Z (2014) Mitochondrial dysfunctions in neurodegenerative diseases: relevance to Alzheimer's disease. BioMed Res Int 2014:175062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Intlekofer KA, Cotman CW (2013) Exercise counteracts declining hippocampal function in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis 57:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Iqbal K, Alonso AC, Chen S, Chohan MO, El‐Akkad E, Gong C‐X et al (2005) Tau pathology in Alzheimer disease and other tauopathies. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)‐Mol Basis Dis 1739:198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ishihara N, Nomura M, Jofuku A, Kato H, Suzuki SO, Masuda K et al (2009) Mitochondrial fission factor Drp1 is essential for embryonic development and synapse formation in mice. Nat Cell Biol 11:958–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]