Abstract

α‐synuclein is normally situated in the nerve terminal but it accumulates and aggregates in axons and cell bodies in synucleinopathies such as Parkinson's disease. The conformational changes occurring during α‐synucleins aggregation process affects its interactions with other proteins and its subcellular localization. This review focuses on interaction partners of α‐synuclein within different compartments of the cell with a focus on those preferentially binding aggregated α‐synuclein. The aggregation state of α‐synuclein also affects its catabolism and we hypothesize impaired macroautophagy is involved neuronal excretion of α‐synuclein species responsible for the prion‐like spreading of α‐synuclein pathology.

Keywords: α‐synuclein, neurodegeneration, protein interaction, proteomics, Parkinson's disease, Lewy Body, dementia

In the normal brain α‐synuclein (AS) is highly enriched in the nerve terminal as noted early at its discovery 74. In some neurodegenerative diseases, so‐called synucleinopathies, AS accumulates in cell bodies and axons as Lewy bodies (LBs) and Lewy neurites, and here it is present in an amyloid‐type aggregated state. The normal “native” state of AS is still a matter of debate and more such states may exist depending of the subcellular context. However, it is generally accepted that AS during pathological conditions enters a path of misfolding, where its native state changes into a partially folded soluble oligomeric state that subsequently enters an insoluble amyloid form. It is important to consider that the AS protein is translated in the cell body and subsequently transported through the axon before ending in the nerve terminal wherefrom it leaves by retrograde axonal transport 48. The protein thus has potential for interacting with a range of cellular structures that may change during diseased states. The normal function of AS is generally believed to be in the nerve terminal. This review will focus on normal and disease associated protein partners of AS defined as monomer and oligomer binding ligands for AS in different compartments partly based on our recent proteomic screen 7. We will speculate on mechanisms involved in the excretion of aberrant potentially prion‐like AS, and we will also describe interactions with lipid structures that are components of membranes, where AS binding may increase its local concentration thereby favoring subsequent protein interactions.

As Association to Membranes

Despite AS enrichment in nerve terminals, brain fractionation experiments reveal both vesicle‐bound and soluble AS 49, 53. The interaction is reduced by PD causing missense mutations 31, 37, 49, 51, 53, 118, suggesting that membrane association is important for the proper functioning of AS. This is corroborated by recent data demonstrating that binding and multimerization of AS on liposomes inhibit aggregation whereas release allows free AS to aggregate 8. Analysis of AS's primary structure identified in 1995 the presence of putative amphiphatic helical domains in the N‐terminal repeat region 35, which allows AS to form alpha‐helical structures upon binding to negative charged membranes in vitro and in vivo 22, 34. When bound to membranes AS has the ability to modulate the phospholipid composition in its vicinity 95 allowing for a dynamic interplay between different AS species and membranes. A structure of micelle bound AS reveals that two alpha‐helices can form in the repeat region with the PD mutations located close to their interhelical region further strengthening a role for alpha‐helical formation in avoiding aberrant functions 96.

Presynaptic Function

AS is highly concentrated in nerve terminals, where it is efficiently transported from the nerve cell body with axonal transport 48. In Parkinson's disease and Lewy body dementia, aggregated AS accumulate in axons and cell bodies as Lewy neurites and LBs 107, but evidence based on detection of proteinase K resistant AS also demonstrate significant aggregation within nerve terminals 61.

The normal biology of AS has been studied by various techniques and studies of a green fluorescent protein (GFP)‐AS fusion protein indicate that AS is highly mobile and subject to regulation by nerve cell activity 33. AS is believed to be important for the long term fidelity of the neurotransmitter release machinery 2, 9, but its effects on neurotransmission seems to be subtle based on AS overexpression‐ and knockout indicating a minor role in the acute regulation of terminal function 63, 85, 120.

Burré et al. showed in 2010 that AS interacts with the SNARE complex, which is involved in neurotransmitter release by mediating vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane. The link between the SNARE complex and AS arose, because the neurodegeneration in CSPα KO mice, which suffer from impaired SNARE complex assembly, could be rescued by additional transgenic overexpression of AS. Interestingly, AS interacted with the SNARE complex independently of CSPα, indicating a direct involvement in enhancing the SNARE complex assembly. VAMP2/synaptobrevin was found to be the direct interaction partner of AS within the complex, and this interaction, and not only the presynaptic localization, was necessary for enhancing SNARE complex assembly 9. Interestingly, our study of interaction partners of oligomeric and monomeric AS shows preferential binding of oligomeric AS to VAMP2 7. This implies that oligomerization enhances VAMP2 binding and could form the structural basis for the clustering of synaptic vesicles by AS multimers and attenuated recycling in vivo 25, 121. Furthermore, our proteomic screen finds Syntaxin‐1A, another protein of the SNARE complex, as an interaction partner of AS (with no preference for monomeric or oligomeric AS). Syntaxin‐1A is also a known interaction partner of CSPα 111, which might be of importance in relation to the compensatory function of AS seen in the CSPα knock out—AS overexpression mouse model.

AS interacts with other synaptic protein such as synapsin I 4, 7, 73 and synapsin III 127. Besides direct interaction, aberrant AS can also redistribute synapsin III shown in an AS aggregation model and in Parkinson's patients. Redistribution of synapsin III is also found upon lack of AS. Synapsin I is not affected in this aggregation model unless truncated AS is overexpressed 127. Synapsin I binds preferentially to oligomeric AS 7 indicating that oligomeric AS can induce alterations in the synaptic physiology.

Although in vitro membrane binding of AS can be shown without additional factors, the binding of AS to presynaptic membranes must be related to and regulated by the environment within the presynapse. A relation between AS and the Rab3a—HSP90—RabGDI complex, which regulates membrane fusion, is found 11. AS binds Rab3a in a membrane dependent manner. The Rab3a proteins cycle between membrane bound‐ and unbound states related on the binding to the Rab‐specific GDP‐dissociation inhibitor (GDI) and HSP90, and upon depolarization and Ca2+ influx, Rab3a GTP is hydrolyzed to GDP and recruited to the GDI‐HSP90 complex and subsequently dissociated from the membrane. Since AS binds the GTP version of Rab3a, dissociation of AS from membranes is likely related to nerve terminal firing and Rab3a dissociation although it remains to be solved whether the two proteins dissociate together or separately. Chen et al. suggest that by removing AS from membranes, its chaperoning activity in relation to SNARE complex assembly is also removed, and thereby vesicle fusion is facilitated—this theory is also supported by the fact that also CSPα is found to bind GDI, because of the proposed compensatory function of CSPα and AS in relation to SNARE complex assembly 9, 11. Interestingly, we find GDI as a preferentially AS oligomer binding protein 7.

Also related to SNARE complex assembly is the septins, which localize to the presynaptic membrane 56, 117. Involvement of septins in neurotransmission is for example evident from the diminished dopaminergic neurotransmission in Sept4 knockout mice 45. However, the direct interaction between Sept2 and AS is only recently found 115 and was confirmed in our proteomic screen as a binder of both monomer and oligomer AS 7. Interestingly, in the study by Tokhtaeva et al 115 synaptotagmin1 and Vesicle‐associated membrane protein‐associated protein B are found as Sept2 interaction partners – two proteins identified in our proteomic screen as binders of AS with no preference for the monomeric or oligomeric form 7. Sept2 binds SNAP‐25, and SNARE complex destabilization is seen upon septin inhibition. Together with previous findings of Sept4 as a component of LBs 45, the septins is a group of possible important interaction partners of AS also because of their cytoskeletal properties.

The transport to and from the presynapse is indeed important for the proper functioning of AS. Tau/MAPT, a known interaction partner of AS 46, that binds microtubules and is important for microtubule stability, also has the propensity itself to aggregate and form toxic aggregates 14, 52. Tau inclusions are found in some Parkinson patients 26, and the binding between Tau and AS increases the aggregation propensity of both proteins 38. The interaction of AS to another MAP (microtubule associated proteins) protein, MAP1B 7, 47 is known and we further identify MAP2 and MAP6 as AS interaction partners in our proteomic screen; MAP6 with preference for oligomeric AS 7. Likewise, we identify three tubulin alfa‐ and beta chains; α‐4a, β‐3 and β‐4 with a preference for oligomeric AS 7. P25α/TPPP, another protein involved in microtubule stabilization, colocalizes with AS in LBs 59, binds AS, and stimulates aggregation of AS 69. As the cytoskeleton represents the tracks responsible for directed movement within the cells, the interaction partners of AS within this machinery are particularly interesting, if they promote AS aggregation or favor binding to aberrant AS.

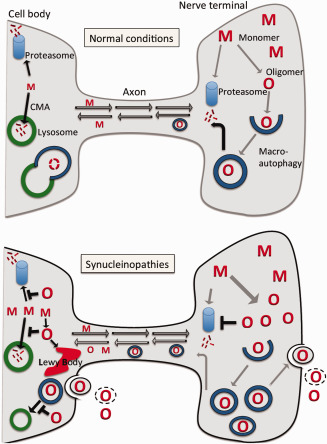

In the disease state with hypothesized aggregation of AS in nerve terminals, these structures are challenged because their proteostatic system is less developed compared to the cell body. Lysosomes are not present in terminals thus excluding chaperone‐mediated autophagy and leaving the proteasome as the only protein catabolic organelle 123. The initiating steps of macroautophagy with formation of autophagosomes are operational in terminals, but then require retrograde axonal transport before their fusion with lysosomes. The autophagosome formation rely on active vesicle acidification 123 and since AS oligomers bind preferentially subunit D1 of the V‐type proton ATPase involved in vesicle acidification, build‐up of AS aggregates thus have the potential of compromising both formation of functional autophagosome and the proteasome 68. Compromised acidification and fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes strongly increase cellular excretion of AS 29. Given autophagosomes are formed by the cell for disposal of aberrant material, we hypothesize that AS aggregation in terminals will lead to inhibited degradation of misfolded AS species that will be sequestered in malfunctional autophagosomes leading to their excretion into the presynaptic cleft where they will be involved in transsynaptic transmission of prion‐like AS particles thus promoting Braak‐type disease progression (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothetical involvement of impaired macroautophagy in neuronal excretion of prion‐like oligomeric α‐synuclein species. Normal conditions: Native or monomeric α‐synuclein (M) is produced in the nerve cell body and transported by anterograde axonal transport to the nerve terminal, where it is present in a high concentration. In nerve terminals, some native α‐synuclein will be degraded by the ubiquitin‐proteasome and some will be transported back to the cell body by retrograde transport. In the cell body, where lysosomes are present, native α‐synuclein can be catabolized by the chaperone mediated autophagic (CMA) system and the ubiquitin‐proteasome system. The high concentration of α‐synuclein in nerve terminals favors some degree of aggregation of native α‐synuclein into low amounts of oligomers (O), which will be recognized by the macroautophagic system and packaged into autophagosomes. The autophagosomes will be transported by retrograde axonal transport to the cell body, where they complete the macroautophagic process by fusing with lysosomes. Synucleinopathies: Build‐up of oligomers (O) in nerve terminals inhibits the ubiquitin‐proteasome system causing increase of native α‐synuclein (M) and further generation of oligomers. The macroautophagy system recognizes the oligomers leading to increased levels of oligomer‐containing autophagosomes that are transported to the cell body by retrograde axonal transport. The increased load of autophagomes in terminals initiates the process of exophagy, where autophagosomes fuse with the plasma membrane releasing their inner oligomer‐containing vesicle to the extracellular space. Extracellularly these vesicles may be taken up by neighboring cells, or the membrane may lyse leaving the oligomers as free particles. In the cell body, increased levels of oligomers inhibit both the ubiquitin‐proteasome system and the chaperone mediated autophagy system leaving the macroautophagic system to dispose of the misfolded α‐synuclein species. However, aberrant α‐synuclein inhibits the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes increasing the flow through the exophagic pathway. Moreover, the cell initiates formation of Lewy bodies to dispose of the increased levels of aggregated α‐synuclein. Conclusively, the increased formation of autophagosomes, which contain oligomeric α‐synuclein species selected by the cellular quality‐control system, combined with a decreased ability to fuse autophagosomes with lysosomes favor exophagy and spreading of aggregated α‐synuclein species that is able to trigger prion‐like spreading upon uptake by neighboring neurons.

As Catabolism

In the cell body where lysosomes are present, cells can dispose AS in several ways but major pathways are macroautophagy, chaperone mediated autophagy (CMA) and proteasomal degradation with their relative contributions regulated by age and other circumstances 27. We only briefly mention specific protein interactions with AS in these processes as they are dealt with in several specialized reviews.

CMA efficiently degrades native AS species and AS has been shown to directly bind Hsc70 and LAMP2A. The LAMP2A binding of mutant and aberrant AS species blocks CMA 20, 77, 92, 93, 125.

The 26S proteasome particle consists of a 20S catalytic particle attached to one or two regulatory 19S particles. AS and 20S proteasome components co‐localize in LBs, and subunits from 20S catalytic proteasome particles bind to AS fibrils but not monomeric AS in a process, where AS filaments and soluble oligomers inhibit proteasomal activity 68. AS also binds the S6’, a subunit of the 19S cap 106, and the regulatory Tat binding protein 1 of the proteasomal complex 36. Hence AS species, apart from being substrates for the proteasome, have the potential of modulating its proteolytic efficiency, thereby disturbing proteostasis.

Synphilin‐1, a known interaction partner of AS 30, 86, promotes inclusions in cell models 30, 88 and is also found as a component of LBs 122. However, a combined synphilin‐1 and A53T AS transgenic mouse model demonstrated that synphilin‐1 partly rescued the phenotype of the A53T AS mouse. Synphilin‐1 has been demonstrated to facilitate autophagy and inhibit the proteasome 1, 105 complicating the interpretation of the contradictory effects of synphilin‐1 on AS toxicity in different models.

Although of quantitative less importance for the clearance of AS, excretion of AS has become of interest in relation to its role for the prion‐like spreading hypothesis and as a biomarker in tissue fluids. Inhibition of regulatory steps in the autophagic process leading to a compromised fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes or activation of mTOR independent autophagy by trehalose 28, 29 leads to increased excretion of AS to the extracellular space. This process may be particularly important, because AS in the autophagosomes have been “selected” by the cell for degradation and thus may represent especially toxic species. Interestingly, cathepsin B, a proteolytic enzyme found in the lysosomes, enhances seeding activity of extracellular AS aggregates leading to AS nucleation and development of early aggregates in the lysosome 119.

The interaction of extracellular AS with cells is critical for initiation of neuroinflammatory responses and prion‐like propagation as highlighted in the chapter by Seung‐Jae Lee of this minisymposium and it will only be briefly covered here. When released into the extracellular space AS may be subject to degradation by proteolytic proteases, including neurosin 113, matrix metalloproteinases 110, and plasmin 54. Deregulation on the levels of such extracellular proteases has also been observed in neurodegenerative diseases other than PD 89. The activity of extracellular AS species may also be modulated by chaperone like molecules, for example members of the HSP70 family, that block AS aggregation and extracellular AS oligomer formation 21, 23, 44. Within the extracellular space AS also can engage antibodies and this is an area of great therapeutic interest. Preclinically more trials have been conducted in animals with the first conducted in 2005 79, and recently it has been demonstrated that AS directed IgG can block the transmission of AS misfolding in a cellular prion‐like spreading paradigm 116 further supporting that AS species indeed are part of the disease spreading structure.

Upregulation of toll‐like receptors (TLRs) in different synucleinopathies suggest a relationship between disease‐associated protein aggregation and microglia‐mediated neuroinflammation 66, 108. TLR2 and 4 have been reported as mediators of glial pro‐inflammatory responses 32, 55. The cellular uptake mechanisms for AS are not clear and may depend on the specific AS species. Monomeric AS can be internalized via ganglioside GM1 in the plasma membrane 78 whereas larger multimerized AS species likely depend on endocytosis 65, 109.

As and Mitochondria

Mitochondria has been closely linked to the pathogenesis of PD via the reduced complex I activity in PD 24, 103 and compiling evidence suggests a link between AS aggregation and mitochondrial dysfunction in PD pathophysiology. Reduced complex I activity is also seen in transgenic mice overexpressing WT AS or A53T AS 81 and modulation of AS levels in cell‐ and mouse models influences mitochondrial dynamics 10, 57, 75, 81, 82, 124. When discussing mitochondrial functions and molecular interactions, it is important to focus on mitochondria's complex structure with an outer membrane and inner membrane, separated by the intermembranous space, and with its matrix surrounded by the inner membrane. The inner membrane is important in ATP production, as structures of the electron transport chain is embedded in this membrane.

Mitochondrial membranes

Biochemical studies have verified an interaction between both normal‐ as well as aberrant AS to mitochondria 24, 67; a binding that appears to be enriched in mitochondria isolated from PD brain samples compared to age matched controls 24. The binding of AS to mitochondrial membranes is favored by the presence of the mitochondria‐specific lipid, cardiolipin, which in reconstituted liposomes binds AS tightly 83. Cardiolipin is enriched on inner mitochondrial membranes compared to outer membranes 17 and AS demonstrates enhanced binding to artificial inner membrane mimics compared to artificial outer membrane mimics 99. A substantial fraction of AS is associated with the inner membranes of mitochondria in PD brain samples 24 and in mitochondria isolated from transgenic mice overexpressing AS 82.

Translocase components in outer and inner mitochondrial membranes

How AS translocates from the cytosol into internal mitochondrial membranous structures is not fully understood but Tom40, a transmembranous component of the Translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane (TOM) complex appears to be involved based on in vitro studies 24. Tom40 levels are significantly reduced in the brain of PD patients and in transgenic mice overexpressing AS 6, and a direct interaction of AS to the TOM complex is corroborated in two proteomic screens 7, 80. Interactions of AS with translocase of the inner membranes, TIM 16 and 44, has also been demonstrated with the TIM44 interaction being favored by aggregated AS 7. These AS interactions with TIM complex components open up the possibility that small amounts of AS can be translocated through the internal membranes into the mitochondrial matrix.

Other mitochondrial proteins

AS binds to the mitochondrial adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT) that is a component of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore 7, 129, which has been linked to AS cytotoxicity 72, 76, 104. Furthermore, AS including its oligomeric form binds to the mitochondrial chaperone, mortalin, also known as Heat shock protein A9 7, 50 that has been implicated in AS cytotoxicity as well 70.

Mitochondria‐associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes

Mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) form apposing membrane structures, mitochondria‐associated ER membranes (MAM) that are highly specialized cellular subdomains involved in a number of key metabolic functions including Ca2+ transfer and phospholipid‐ and cholesterol metabolism 42. Tethering molecules on both membranes facilitate their stability. AS is localized to MAM structures in different cell lines 10, 40 and facilitated Ca2+ transfer between ER and mitochondria via structural elements in the C‐terminal domain of AS 10. The familial PD AS point mutations, A53T and A30P weakened MAM binding in subcellular fractionation studies and also appeared to weaken MAM tethering in general in cellular studies 40. The observations of AS interaction with the MAM region are corroborated by our proteomic screen showing interactions between monomeric and oligomeric AS and the calcium transporting Voltage‐dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1) that allows Ca2+ to enter the intermembranous space of mitochondria from ER in MAM interphases 7. VDAC1 has previously been shown to contribute to MAM tethering and could potentially be a mediator of AS involvement in the MAM region 97. VDAC1 positive nigral neurons and tissue levels are decreased in brain samples from sporadic and familial PD cases compared with age‐matched control—a finding replicated in substantia nigra from rodents overexpressing AS 12. These studies suggest AS to play a role in the maintenance of Ca2+ homeostasis by influencing the strength of subcellular MAM structures but mechanistically this is still unclear, as in vitro data demonstrate AS reversibly can block, rather than activate, VDAC channels 101.

Endoplasmic Reticulum

Unfolded protein response

The ER is a multifunctional tubular organelle that emanates from the nuclear membrane and penetrates most of the cytosol. It is involved in a multitude of functions including lipid biosynthesis, protein folding‐ and sorting, and calcium storage‐ and signaling. The unfolded protein response (UPR) is a major cellular stress response that originates from ER when encountering increased unfolded proteins within its lumen. The ER chaperone glucose regulated protein 78 (GRP78/BIP) normally resides bound to the luminal domain of the stress sensors inositol‐requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1 α) and protein kinase RNA‐like ER kinase (PERK), but dissociates from them when binding to unfolded proteins. This causes PERK and IRE1 α to initiate stress signals. AS binds directly to GRP78/BIP in coimmunoprecipitation experiments 7, and the two colocalized in AS transgenic HEK93 cells 5. Moreover, intraluminal serine129 phosphorylated and aggregated AS accumulated in ER‐enriched microsomes isolated from A53T mice prior to development of symptoms 16, and treatment with the UPR inhibitor Salubrinal attenuated the phenotype 15. The age related decrease in GRP78/BIP expression 102 is reversed in A53T mice 15 and in DLB and PD patients, where an increase occurs in brain tissue affected by AS pathology 3. The A53T mice also demonstrated increased levels of the ER chaperone Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) 15 that binds AS 7, 126 and colocalizes with AS in glial cytoplasmic inclusions 43 as well as in LBs from a DLB patient 18. The ER chaperone GRP94/endoplasmin, a member of the HSP90 chaperone family 58, 64 also binds aggregated AS 7, 50, and may modulate the immune response from AS 62. Hence, accumulation of misfolded AS in the ER has potential to be a pathogenic trigger and modulator of UPR in synucleinopathies.

ER‐Golgi sorting of proteins

Proteins destined for secretion or transported to vesicular compartments pass from the ER to the Golgi apparatus. Overexpression of AS leads to early inhibition of vesicular transport from ER to Golgi in yeast 19 and mammalian cells 114 by antagonizing ER/Golgi SNARES. The B‐cell receptor‐associated protein 31 (BAP31) interacts with AS 7. It is a multipass transmembrane and pro‐apoptotic protein in the ER involved in transporting membrane proteins to the synapses via Golgi. Also, a complex formed between BAP31 and cell death‐inducing p53 target 1 activates the caspase‐8 pathway 84, which is activated in tissue from PD patients 41. Discrepancy from in vitro studies exists on whether caspase‐8 is activated in models of AS aggregation dependent degeneration. Initially, caspase‐8 was found not to be activated by AS‐overexpression in PC12 cells 112, but more recently inhibition of caspase‐8 have been show to reverse the AS aggregation degeneration in OLN‐t40‐AS cells 60. Another AS interaction partner Sec61A2 7 is located in ER and ER‐Golgi intermediate compartment 39, and the calcium binding reticulocalbin 2 also binds AS 7 demonstrating that AS has potential in off‐setting steps in the secretory protein pathway.

Calcium

Treatment with L‐type calcium channel antagonists protects against development of sporadic PD but the molecular mechanisms are unclear 91, 98. AS can bind calcium and this stimulates its aggregation but the binding is weak with a Kd about 0.5 mM 71, 87. However, it may affect AS aggregation in the ER where this concentration is present. STIM1 represents a possible link between ER calcium homeostasis and aggregated AS, because STIM1 was identified as a ligand for aggregated AS in our proteomic screen 7. STIM1 proteins are clustering in areas of ER in close proximity with the plasma membrane in order to activate the store‐operated calcium entry when ER calcium becomes too low 13, 94. STIM1 clusters collect Orai1 subunits and assemble them into calcium‐release activated channels, which facilitate uptake of extracellular calcium 90, 100, 128. AS was also identified as a ligand for the calcium binding and regulatory proteins calmodulin [proposed to be a specific interactor of pSer129 AS 80], reticulocalbin 2, and plasma membrane calcium ATPase, that actively transport cytosolic calcium ions to the extracellular compartment 7.

The demonstration of specific protein targets for AS species allows hypothesizing on critical pathways and also provides means for specifically perturbing these processes in the quest for disease modifying therapies. However, one should bear in mind that another level of AS interactions with RNA species still aren't explored and may reveal a regulatory network that so far has been under the radar and which potentially could have large functional impacts.

References

- 1. Alvarez‐Castelao B, Castano JG (2011) Synphilin‐1 inhibits alpha‐synuclein degradation by the proteasome. Cell Mol Life Sci 68:2643–2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anwar S, Peters O, Millership S, Ninkina N, Doig N, Connor‐Robson N et al (2011) Functional alterations to the nigrostriatal system in mice lacking all three members of the synuclein family. J Neurosci 31:7264–7274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baek JH, Whitfield D, Howlett D, Francis P, Bereczki E, Ballard C et al (2015) Unfolded protein response is activated in Lewy body dementias. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol [Epub ahead of print; doi: 10.1111/nan.12260]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bellucci A, Navarria L, Falarti E, Zaltieri M, Bono F, Collo G et al (2011) Redistribution of DAT/alpha‐synuclein complexes visualized by “in situ” proximity ligation assay in transgenic mice modelling early Parkinson's disease. PLoS One 6:e27959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bellucci A, Navarria L, Zaltieri M, Falarti E, Bodei S, Sigala S et al (2011) Induction of the unfolded protein response by alpha‐synuclein in experimental models of Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem 116:588–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bender A, Desplats P, Spencer B, Rockenstein E, Adame A, Elstner M et al (2013) TOM40 mediates mitochondrial dysfunction induced by alpha‐synuclein accumulation in Parkinson's disease. PLoS One 8:e62277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 7. Betzer C, Movius AJ, Shi M, Gai WP, Zhang J, Jensen PH (2015) Identification of synaptosomal proteins binding to monomeric and oligomeric alpha‐synuclein. PLoS One 10:e0116473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burre J, Sharma M, Sudhof TC (2015) Definition of a molecular pathway mediating alpha‐synuclein neurotoxicity. J Neurosci 35:5221–5232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burré J, Sharma M, Tsetsenis T, Buchman V, Etherton MR, Südhof TC (2010) Alpha‐synuclein promotes SNARE‐complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science 329:1663–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Calì T, Ottolini D, Negro A, Brini M (2012) Alpha‐Synuclein controls mitochondrial calcium homeostasis by enhancing endoplasmic reticulum‐mitochondria interactions. J Biol Chem 287:17914–17929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen RH, Wislet‐Gendebien S, Samuel F, Visanji NP, Zhang G, Marsilio D et al (2013) alpha‐Synuclein membrane association is regulated by the Rab3a recycling machinery and presynaptic activity. J Biol Chem 288:7438–7449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chu Y, Goldman JG, Kelly L, He Y, Waliczek T, Kordower JH (2014) Abnormal alpha‐synuclein reduces nigral voltage‐dependent anion channel 1 in sporadic and experimental Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis 69:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clapham DE (2007) Calcium signaling. Cell 131:1047–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cleveland DW, Hwo SY, Kirschner MW (1977) Purification of tau, a microtubule‐associated protein that induces assembly of microtubules from purified tubulin. J Mol Biol 116:207–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Colla E, Coune P, Liu Y, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Iwatsubo T et al (2012) Endoplasmic reticulum stress is important for the manifestations of alpha‐synucleinopathy in vivo. J Neurosci 32:3306–3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Colla E, Jensen PH, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Glabe C, Lee MK (2012) Accumulation of toxic alpha‐synuclein oligomer within endoplasmic reticulum occurs in alpha‐synucleinopathy in vivo. J Neurosci 32:3301–3305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Comte J, Maǐsterrena B, Gautheron DC. Lipid composition and protein profiles of outer and inner membranes from pig heart mitochondria. Comparison with microsomes. Biochim Biophys Acta 419:271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Conn KJ, Gao W, McKee A, Lan MS, Ullman MD, Eisenhauer PB et al (2004) Identification of the protein disulfide isomerase family member PDIp in experimental Parkinson's disease and Lewy body pathology. Brain Res 1022:164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cooper AA et al (2006) Alpha‐synuclein blocks ER‐Golgi traffic and Rab1 rescues neuron loss in Parkinson's models. Science 313:324–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cuervo AM, Stefanis L, Fredenburg R, Lansbury PT, Sulzer D (2004) Impaired degradation of mutant alpha‐synuclein by chaperone‐mediated autophagy. Science 305:1292–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Danzer KM, Ruf WP, Putcha P, Joyner D, Hashimoto T, Glabe C et al (2011) Heat‐shock protein 70 modulates toxic extracellular alpha‐synuclein oligomers and rescues trans‐synaptic toxicity. FASEB J 25:326–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davidson WS, Jonas A, Clayton DF, George JM (1998) Stabilization of alpha‐synuclein secondary structure upon binding to synthetic membranes. J Biol Chem 273:9443–9449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dedmon MM, Christodoulou J, Wilson MR, Dobson CM (2005) Heat shock protein 70 inhibits alpha‐synuclein fibril formation via preferential binding to prefibrillar species. J Biol Chem 280:14733–14740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Devi L, Raghavendran V, Prabhu BM, Avadhani NG, Anandatheerthavarada HK (2008) Mitochondrial import and accumulation of alpha‐synuclein impair complex I in human dopaminergic neuronal cultures and Parkinson disease brain. J Biol Chem 283:9089–9100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Diao J, Burré J, Vivona S, Cipriano DJ, Sharma M, Kyoung M (2013) Native alpha‐synuclein induces clustering of synaptic‐vesicle mimics via binding to phospholipids and synaptobrevin‐2/VAMP2. Elife 2:e00592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Duda JE, Giasson BI, Mabon ME, Miller DC, Golbe LI, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ (2002) Concurrence of alpha‐synuclein and tau brain pathology in the Contursi kindred. Acta Neuropathol 104:7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ebrahimi‐Fakhari D, Cantuti‐Castelvetri I, Fan Z, Rockenstein E, Masliah E, Hyman BT et al (2011) Distinct roles in vivo for the ubiquitin‐proteasome system and the autophagy‐lysosomal pathway in the degradation of alpha‐synuclein. J Neurosci 31:14508–14520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ejlerskov P, Hultberg JG, Wang J, Carlsson R, Ambjørn M, Kuss M et al (2015) Lack of Neuronal IFN‐beta‐IFNAR Causes Lewy Body‐ and Parkinson's Disease‐like Dementia. Cell 163:324–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ejlerskov P, Rasmussen I, Nielsen TT, Bergström AL, Tohyama Y, Jensen PH, Vilhardt F (2013) Tubulin polymerization‐promoting protein (TPPP/p25alpha) promotes unconventional secretion of alpha‐synuclein through exophagy by impairing autophagosome‐lysosome fusion. J Biol Chem 288:17313–17335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Engelender S, Kaminsky Z, Guo X, Sharp AH, Amaravi RK, Kleiderlein JJ et al (1999) Synphilin‐1 associates with alpha‐synuclein and promotes the formation of cytosolic inclusions. Nat Genet 22:110–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fares MB, Ait‐Bouziad N, Dikiy I, Mbefo MK, Jovičić A, Kiely A et al (2014) The novel Parkinson's disease linked mutation G51D attenuates in vitro aggregation and membrane binding of alpha‐synuclein, and enhances its secretion and nuclear localization in cells. Hum Mol Genet 23:4491–4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fellner L, Irschick R, Schanda K, Reindl M, Klimaschewski L, Poewe W et al (2013) Toll‐like receptor 4 is required for alpha‐synuclein dependent activation of microglia and astroglia. Glia 61:349–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fortin DL, Nemani VM, Voglmaier SM, Anthony MD, Ryan TA, Edwards RH (2005) Neural activity controls the synaptic accumulation of alpha‐synuclein. J Neurosci 25:10913–10921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fortin DL, Troyer MD, Nakamura K, Kubo S, Anthony MD, Edwards RH (2004) Lipid rafts mediate the synaptic localization of alpha‐synuclein. J Neurosci 24:6715–6723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. George JM, Jin H, Woods WS, Clayton DF (1995) Characterization of a novel protein regulated during the critical period for song learning in the zebra finch. Neuron 15:361–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ghee M, Fournier A, Mallet J (2000) Rat alpha‐synuclein interacts with Tat binding protein 1, a component of the 26S proteasomal complex. J Neurochem 75:2221–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ghosh D, Sahay S, Ranjan P, Salot S, Mohite GM, Singh PK et al (2014) The newly discovered Parkinson's disease associated Finnish mutation (A53E) attenuates alpha‐synuclein aggregation and membrane binding. Biochemistry 53:6419–6421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Giasson BI, Forman MS, Higuchi M, Golbe LI, Graves CL, Kotzbauer PT et al (2003) Initiation and synergistic fibrillization of tau and alpha‐synuclein. Science 300:636–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Greenfield JJ, High S (1999) The Sec61 complex is located in both the ER and the ER‐Golgi intermediate compartment. J Cell Sci 112:1477–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guardia‐Laguarta C, Area‐Gomez E, Rüb C, Liu Y, Magrané J, Becker D et al (2014) Alpha‐Synuclein is localized to mitochondria‐associated ER membranes. J Neurosci 34:249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hartmann A, Troadec JD, Hunot S, Kikly K, Faucheux BA, Mouatt‐Prigent A et al (2001) Caspase‐8 is an effector in apoptotic death of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson's disease, but pathway inhibition results in neuronal necrosis. J Neurosci 21:2247–2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hayashi T, Rizzuto R, Hajnoczky G, Su TP (2009) MAM: more than just a housekeeper. Trends Cell Biol 19:81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Honjo Y, Ito H, Horibe T, Takahashi R, Kawakami K (2011) Protein disulfide isomerase immunopositive glial cytoplasmic inclusions in patients with multiple system atrophy. Int J Neurosci 121:543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huang C, Cheng H, Hao S, Zhou H, Zhang X, Gao J et al (2006) Heat shock protein 70 inhibits alpha‐synuclein fibril formation via interactions with diverse intermediates. J Mol Biol 364:323–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ihara M, Yamasaki N, Hagiwara A, Tanigaki A, Kitano A, Hikawa R et al (2007) Sept4, a component of presynaptic scaffold and Lewy bodies, is required for the suppression of alpha‐synuclein neurotoxicity. Neuron 53:519–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jensen PH, Hager H, Nielsen MS, Hojrup P, Gliemann J, Jakes R (1999) alpha‐synuclein binds to Tau and stimulates the protein kinase A‐catalyzed tau phosphorylation of serine residues 262 and 356. J Biol Chem 274:25481–25489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jensen PH, Islam K, Kenney J, Nielsen MS, Power J, Gai WP (2000) Microtubule‐associated protein 1B is a component of cortical Lewy bodies and binds alpha‐synuclein filaments. J Biol Chem 275:21500–21507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jensen PH, Li JY, Dahlström A, Dotti CG (1999) Axonal transport of synucleins is mediated by all rate components. Eur J Neurosci 11:3369–3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jensen PH, Nielsen MS, Jakes R, Dotti CG, Goedert M (1998) Binding of alpha‐synuclein to brain vesicles is abolished by familial Parkinson's disease mutation. J Biol Chem 273:26292–26294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jin J, Li GJ, Davis J, Zhu D, Wang Y, Pan C, Zhang J (2007) Identification of novel proteins associated with both alpha‐synuclein and DJ‐1. Mol Cell Proteomics 6:845–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jo E, Fuller N, Rand RP, St George‐Hyslop P, Fraser PE (2002) Defective membrane interactions of familial Parkinson's disease mutant A30P alpha‐synuclein. J Mol Biol 315:799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Joachim CL, Morris JH, Kosik KS, Selkoe DJ (1987) Tau antisera recognize neurofibrillary tangles in a range of neurodegenerative disorders. Ann Neurol 22:514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kahle PJ, Neumann M, Ozmen L, Muller V, Jacobsen H, Schindzielorz A et al (2000) Subcellular localization of wild‐type and Parkinson's disease‐associated mutant alpha ‐synuclein in human and transgenic mouse brain. J Neurosci 20:6365–6373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim KS, Choi YR, Park JY, Lee JH, Kim DK, Lee SJ et al (2012) Proteolytic cleavage of extracellular alpha‐synuclein by plasmin: implications for Parkinson disease. J Biol Chem 287:24862–24872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kim C, Ho DH, Suk JE, You S, Michael S, Kang J et al (2013) Neuron‐released oligomeric alpha‐synuclein is an endogenous agonistof TLR2 for paracrine activation of microglia. Nat Commun 4:1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kinoshita A, Noda M, Kinoshita M (2000) Differential localization of septins in the mouse brain. J Comp Neurol 428:223–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Knott AB, Perkins G, Schwarzenbacher R, Bossy‐Wetzel E (2008) Mitochondrial fragmentation in neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci 9:505–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Koch G, Smith M, Macer D, Webster P, Mortara R (1986) Endoplasmic reticulum contains a common, abundant calcium‐binding glycoprotein, endoplasmin. J Cell Sci 86:217–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kovács GG, László L, Kovács J, Jensen PH, Lindersson E, Botond G et al (2004) Natively unfolded tubulin polymerization promoting protein TPPP/p25 is a common marker of alpha‐synucleinopathies. Neurobiol Dis 17:155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kragh CL, Fillon G, Gysbers A, Hansen HD, Neumann M, Richter-Landsberg C et al (2013) FAS‐dependent cell death in alpha‐synuclein transgenic oligodendrocyte models of multiple system atrophy. PLoS One 8:e55243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kramer ML, Schulz‐Schaeffer WJ (2007) Presynaptic alpha‐synuclein aggregates, not Lewy bodies, cause neurodegeneration in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurosci 27:1405–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Labrador‐Garrido A, Cejudo-Guillen M, Daturpalli S, Leal MM, Klippstein R, De Genst EJ et al (2015) Chaperome screening leads to identification of Grp94/Gp96 and FKBP4/52 as modulators of the alpha‐synuclein‐elicited immune response. FASEB J 30:564–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Larsen KE, Schmitz Y, Troyer MD, Mosharov E, Dietrich P, Quazi AZ et al (2006) Alpha‐synuclein overexpression in PC12 and chromaffin cells impairs catecholamine release by interfering with a late step in exocytosis. J Neurosci 26:11915–11922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lee AS (1992) Mammalian stress response: induction of the glucose‐regulated protein family. Curr Opin Cell Biol 4:267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lee HJ, Suk JE, Bae EJ, Lee JH, Paik SR, Lee SJ (2008) Assembly‐dependent endocytosis and clearance of extracellular alpha‐synuclein. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40:1835–1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Letiembre M, Liu Y, Walter S, Hao W, Pfander T, Wrede A et al (2009) Screening of innate immune receptors in neurodegenerative diseases: a similar pattern. Neurobiol Aging 30:759–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Li WW, Yang R, Guo JC, Ren HM, Zha XL, Cheng JS, Cai DF (2007) Localization of alpha‐synuclein to mitochondria within midbrain of mice. Neuroreport 18:1543–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lindersson E, Beedholm R, Højrup P, Moos T, Gai W, Hendil KB, Jensen PH (2004) Proteasomal inhibition by alpha‐synuclein filaments and oligomers. J Biol Chem 279:12924–12934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lindersson E, Lundvig D, Petersen C, Madsen P, Nyengaard JR, Højrup P et al (2005) p25alpha Stimulates alpha‐synuclein aggregation and is co‐localized with aggregated alpha‐synuclein in alpha‐synucleinopathies. J Biol Chem 280:5703–5715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Liu FT, Chen Y, Yang YJ, Yang L, Yu M, Zhao J et al (2015) Involvement of mortalin/GRP75/mthsp70 in the mitochondrial impairments induced by A53T mutant alpha‐synuclein. Brain Res 1604:52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lowe R, Pountney DL, Jensen PH, Gai WP, Voelcker NH (2004) Calcium(II) selectively induces alpha‐synuclein annular oligomers via interaction with the C‐terminal domain. Protein Sci 13:3245–3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Luth ES, Stavrovskaya IG, Bartels T, Kristal BS, Selkoe DJ (2014) Soluble, prefibrillar alpha‐synuclein oligomers promote complex I‐dependent, Ca2+‐induced mitochondrial dysfunction. J Biol Chem 289:21490–21507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Maiya R, Ponomarev I, Linse KD, Harris RA, Mayfield RD (2007) Defining the dopamine transporter proteome by convergent biochemical and in silico analyses. Genes Brain Behav 6:97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Maroteaux L, Campanelli JT, Scheller RH (1988) Synuclein: a neuron‐specific protein localized to the nucleus and presynaptic nerve terminal. J Neurosci 8:2804–2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Martin LJ, Pan Y, Price AC, Sterling W, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA et al (2006) Parkinson's disease alpha‐synuclein transgenic mice develop neuronal mitochondrial degeneration and cell death. J Neurosci 26:41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Martin LJ, Semenkow S, Hanaford A, Wong M (2014) Mitochondrial permeability transition pore regulates Parkinson's disease development in mutant alpha‐synuclein transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging 35:1132–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Martinez‐Vicente M, Talloczy Z, Kaushik S, Massey AC, Mazzulli J, Mosharov EV et al (2008) Dopamine‐modified alpha‐synuclein blocks chaperone‐mediated autophagy. J Clin Invest 118:777–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Martinez Z, Zhu M, Han S, Fink AL (2007) GM1 specifically interacts with alpha‐synuclein and inhibits fibrillation. Biochemistry 46:1868–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Adame A, Alford M, Crews L, Hashimoto M et al (2005) Effects of alpha‐synuclein immunization in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Neuron 46:857–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. McFarland MA, Ellis CE, Markey SP, Nussbaum RL (2008) Proteomics analysis identifies phosphorylation‐dependent alpha‐synuclein protein interactions. Mol Cell Proteomics 7:2123–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Nakamura K (2013) Alpha‐Synuclein and mitochondria: partners in crime? Neurotherapeutics 10:391–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Nakamura K, Nemani VM, Azarbal F, Skibinski G, Levy JM, Egami K et al (2011) Direct membrane association drives mitochondrial fission by the Parkinson disease‐associated protein alpha‐synuclein. J Biol Chem 286:20710–20726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nakamura K, Nemani VM, Wallender EK, Kaehlcke K, Ott M, Edwards RH (2008) Optical reporters for the conformation of alpha‐synuclein reveal a specific interaction with mitochondria. J Neurosci 28:12305–12317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Namba T, Tian F, Chu K, Hwang SY, Yoon KW, Byun S et al (2013) CDIP1‐BAP31 complex transduces apoptotic signals from endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria under endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Rep 5:331–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Nemani VM, Lu W, Berge V, Nakamura K, Onoa B, Lee MK et al (2010) Increased expression of alpha‐synuclein reduces neurotransmitter release by inhibiting synaptic vesicle reclustering after endocytosis. Neuron 65:66–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Neystat M, Rzhetskaya M, Kholodilov N, Burke RE (2002) Analysis of synphilin‐1 and synuclein interactions by yeast two‐hybrid beta‐galactosidase liquid assay. Neurosci Lett 325:119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Nielsen MS, Vorum H, Lindersson E, Jensen PH (2001) Ca2+ binding to alpha‐synuclein regulates ligand binding and oligomerization. J Biol Chem 276:22680–22684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. O'Farrell C, Murphy DD, Petrucelli L, Singleton AB, Hussey J, Farrer M et al (2001) Transfected synphilin‐1 forms cytoplasmic inclusions in HEK293 cells. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 97:94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Park SM, Kim KS (2013) Proteolytic clearance of extracellular alpha‐synuclein as a new therapeutic approach against Parkinson disease. Prion 7:121–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Parekh AB, Penner R (1997) Store depletion and calcium influx. Physiol Rev 77:901–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Pasternak B, Svanstrom H, Nielsen NM, Fugger L, Melbye M, Hviid A (2012) Use of calcium channel blockers and Parkinson's disease. Am J Epidemiol 175:627–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Pemberton S, Madiona K, Pieri L, Kabani M, Bousset L, Melki R (2011) Hsc70 protein interaction with soluble and fibrillar alpha‐synuclein. J Biol Chem 286:34690–34699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Pemberton S, Melki R (2012) The interaction of Hsc70 protein with fibrillar alpha‐Synuclein and its therapeutic potential in Parkinson's disease. Commun Integr Biol 5:94–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Putney JW Jr (2005) Capacitative calcium entry: sensing the calcium stores. J Cell Biol 169:381–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Ramakrishnan M, Jensen PH, Marsh D (2003) Alpha‐synuclein association with phosphatidylglycerol probed by lipid spin labels. Biochemistry 42:12919–12926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Rao JN, Jao CC, Hegde BG, Langen R, Ulmer TS (2010) A combinatorial NMR and EPR approach for evaluating the structural ensemble of partially folded proteins. J Am Chem Soc 132:8657–8668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Raturi A, Simmen T (2013) Where the endoplasmic reticulum and the mitochondrion tie the knot: the mitochondria‐associated membrane (MAM). Biochim Biophys Acta 1833:213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Ritz B, Rhodes SL, Qian L, Schernhammer E, Olsen JH, Friis S (2010) L‐type calcium channel blockers and Parkinson disease in Denmark. Ann Neurol 67:600–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Robotta M, Gerding HR, Vogel A, Hauser K, Schildknecht S, Karreman C et al (2014) Alpha‐synuclein binds to the inner membrane of mitochondria in an alpha‐helical conformation. Chembiochem 15:2499–2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S et al (2005) STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store‐operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol 169:435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Rostovtseva TK, Gurnev PA, Protchenko O, Hoogerheide DP, Yap TL, Philpott CC et al (2015) Alpha‐Synuclein Shows High Affinity Interaction with Voltage‐dependent Anion Channel, Suggesting Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Regulation and Toxicity in Parkinson Disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 290:18467–18477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Salganik M, Sergeyev VG, Shinde V, Meyers CA, Gorbatyuk MS, Lin JH et al (2015) The loss of glucose‐regulated protein 78 (GRP78) during normal aging or from siRNA knockdown augments human alpha‐synuclein (alpha‐syn) toxicity to rat nigral neurons. Neurobiol Aging 36:2213–2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Schapira AH, Cooper JM, Dexter D, Clark JB, Jenner P, Marsden CD (1990) Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem 54:823–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Shen J, Du T, Wang X, Duan C, Gao G, Zhang J et al (2014) Alpha‐Synuclein amino terminus regulates mitochondrial membrane permeability. Brain Res 1591:14–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Smith WW, Liu Z, Liang Y, Masuda N, Swing DA, Jenkins NA et al (2010) Synphilin‐1 attenuates neuronal degeneration in the A53T alpha‐synuclein transgenic mouse model. Hum Mol Genet 19:2087–2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Snyder H, Mensah K, Theisler C, Lee J, Matouschek A, Wolozin B (2003) Aggregated and monomeric alpha‐synuclein bind to the S6’ proteasomal protein and inhibit proteasomal function. J Biol Chem 278:11753–11759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M (1997) Alpha‐synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388:839–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Stefanova N, Reindl M, Neumann M, Kahle PJ, Poewe W, Wenning GK (2007) Microglial activation mediates neurodegeneration related to oligodendroglial alpha‐synucleinopathy: implications for multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord 22:2196–2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Sung JY, Kim J, Paik SR, Park JH, Ahn YS, Chung KC (2001) Induction of neuronal cell death by Rab5A‐dependent endocytosis of alpha‐synuclein. J Biol Chem 276:27441–27448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Sung JY, Park SM, Lee CH, Um JW, Lee HJ, Kim J et al (2005) Proteolytic cleavage of extracellular secreted {alpha}‐synuclein via matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem 280:25216–25224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Swayne LA, Beck KE, Braun JE (2006) The cysteine string protein multimeric complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 348:83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Tanaka Y, Engelender S, Igarashi S, Rao RK, Wanner T, Tanzi RE et al (2001) Inducible expression of mutant alpha‐synuclein decreases proteasome activity and increases sensitivity to mitochondria‐dependent apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet 10:919–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Tatebe H, Watanabe Y, Kasai T, Mizuno T, Nakagawa M, Tanaka M, Tokuda T (2010) Extracellular neurosin degrades alpha‐synuclein in cultured cells. Neurosci Res 67:341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Thayanidhi N, Helm JR, Nycz DC, Bentley M, Liang Y, Hay JC (2010) Alpha‐synuclein delays endoplasmic reticulum (ER)‐to‐Golgi transport in mammalian cells by antagonizing ER/Golgi SNAREs. Mol Biol Cell 21:1850–1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Tokhtaeva E, Capri J, Marcus EA, Whitelegge JP, Khuzakhmetova V, Bukharaeva E et al (2015) Septin dynamics are essential for exocytosis. J Biol Chem 290:5280–5297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Tran HT, Chung CH, Iba M, Zhang B, Trojanowski JQ, Luk KC, Lee VM (2014) Alpha‐synuclein immunotherapy blocks uptake and templated propagation of misfolded alpha‐synuclein and neurodegeneration. Cell Rep 7:2054–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Tsang CW, Estey MP, DiCiccio JE, Xie H, Patterson D, Trimble WS (2011) Characterization of presynaptic septin complexes in mammalian hippocampal neurons. Biol Chem 392:739–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Tsigelny IF, Sharikov Y, Kouznetsova VL, Greenberg JP, Wrasidlo W, Overk C et al (2015) Molecular determinants of alpha‐synuclein mutants’ oligomerization and membrane interactions. ACS Chem Neurosci 6:403–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Tsujimura A, Taguchi K, Watanabe Y, Tatebe H, Tokuda T, Mizuno T, Tanaka M (2015) Lysosomal enzyme cathepsin B enhances the aggregate forming activity of exogenous alpha‐synuclein fibrils. Neurobiol Dis 73: 244–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Wu N, Joshi PR, Cepeda C, Masliah E, Levine MS (2010) Alpha‐synuclein overexpression in mice alters synaptic communication in the corticostriatal pathway. J Neurosci Res 88:1764–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Wang L, Das U, Scott DA, Tang Y, McLean PJ, Roy S (2014) Alpha‐synuclein multimers cluster synaptic vesicles and attenuate recycling. Curr Biol 24:2319–2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Wakabayashi K, Engelender S, Yoshimoto M, Tsuji S, Ross CA, Takahashi H (2000) Synphilin‐1 is present in Lewy bodies in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol 47:521–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Wang T, Martin S, Papadopulos A, Harper CB, Mavlyutov TA, Niranjan D et al (2015) Control of autophagosome axonal retrograde flux by presynaptic activity unveiled using botulinum neurotoxin type A. J Neurosci 35:6179–6194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Xie W, Chung KK (2012) Alpha‐synuclein impairs normal dynamics of mitochondria in cell and animal models of Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem 122:404–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Xilouri M, Vogiatzi T, Vekrellis K, Park D, Stefanis L (2009) Abberant alpha‐synuclein confers toxicity to neurons in part through inhibition of chaperone‐mediated autophagy. PLoS One 4:e5515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Yagi‐Utsumi M, Satoh T, Kato K (2015) Structural basis of redox‐dependent substrate binding of protein disulfide isomerase. Sci Rep 5:13909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Zaltieri M, Grigoletto J, Longhena F, Navarria L, Favero G, Castrezzati S et al (2015) alpha‐synuclein and synapsin III cooperatively regulate synaptic function in dopamine neurons. J Cell Sci 128:2231–2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Zhang SL, Yu Y, Roos J, Kozak JA, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH et al (2005) STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature 437:902–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Zhu Y, Duan C, Lü L, Gao H, Zhao C, Yu S et al (2011) Alpha‐Synuclein overexpression impairs mitochondrial function by associating with adenylate translocator. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 43:732–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]