Abstract

Objective

Determine the effectiveness of digital mental health interventions for individuals with a concomitant chronic disease.

Design

We conducted a rapid review of systematic reviews. Two reviewers independently conducted study selection and risk of bias evaluation. A standardised extraction form was used. Data are reported narratively.

Interventions

We included systematic reviews of digital health interventions aiming to prevent, detect or manage mental health problems in individuals with a pre-existing chronic disease, including chronic mental health illnesses, published in 2010 or after.

Main outcome measure

Reports on mental health outcomes (eg, anxiety symptoms and depression symptoms).

Results

We included 35 reviews, totalling 702 primary studies with a total sample of 50 692 participants. We structured the results in four population clusters: (1) chronic diseases, (2) cancer, (3) mental health and (4) children and youth. For populations presenting a chronic disease or cancer, health provider directed digital interventions (eg, web-based consultation, internet cognitive–behavioural therapy) are effective and safe. Further analyses are required in order to provide stronger recommendations regarding relevance for specific population (such as children and youth). Web-based interventions and email were the modes of administration that had the most reports of improvement. Virtual reality, smartphone applications and patient portal had limited reports of improvement.

Conclusions

Digital technologies could be used to prevent and manage mental health problems in people living with chronic conditions, with consideration for the age group and type of technology used.

Keywords: mental health, health informatics, general medicine (see internal medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We conducted a rapid review of systematic reviews published in the last 10 years, including a large body of evidence in four clusters of population.

A panel of knowledge users were involved in each step of the review, from conceptualisation to publication to ensure relevance in clinical context and policy making.

Study selection and bias evaluation were completed by two independent reviewers and data extraction used a standardised form.

We limited the search to the most relevant databases and the last 10 years.

The overlapping of primary studies was not evaluated.

Introduction

Chronic diseases are the main burden on healthcare systems in developed countries and account for almost 70% of deaths worldwide.1 An individual with a chronic condition is two to three times more likely to present a concomitant mental health problem than the general population.2 As the number of physical chronic conditions increase in a population, so do the mental health ones. The co-occurrence of chronic and mental health conditions leads to an increase in total healthcare costs and services utilisation, as well as poorer quality of life and health outcomes for these individuals.3 4

The psychosocial consequences of the current COVID-19 pandemic are alarming and will persist long after the pandemic is over.5 In the current COVID-19 pandemic context, efforts have been invested to rapidly produce scientific evidence in mental health for adapting the clinical setting and supporting policy making (eg, confinement measures). Adapting to telehealth, when in-person consultation is not recommended, requires efficient and relevant digital mental health interventions for the population with concomitant chronic diseases and mental health issues. While a large number of interventions using digital technologies have been evaluated for the management of depression or anxiety,6 7 the relevance of these interventions for people living with chronic diseases remains to be defined.

This rapid review of systematic reviews aimed to determine effectiveness of digital mental health interventions aiming to prevent, detect or manage mental health problems in individuals with a pre-existing chronic condition.

Methods

We conducted a rapid review following the guidance from the Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group.8 We report our results based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement.9 The protocol for this rapid review was registered in the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools COVID-19 Rapid Evidence Service (ID 75).

Knowledge users engagement

We engaged a panel of knowledge users (patients, clinicians and decision makers), content experts, review methodologists and researchers throughout the review process, from question development, literature search, data extraction and analysis, interpretation and writing of results, and dissemination of findings.

Eligibility criteria

We followed the PICO Framework in establishing eligibility criteria10 (table 1). We considered any review that included digital health interventions aiming to prevent, detect or manage mental health problems in individuals with a pre-existing chronic disease, including chronic mental health diseases, published in 2010 or after. There was no language restriction.

Table 1.

PICO eligibility criteria

| Population (P) | Adults with any chronic disease (eg, diabetes, ischaemic heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, arthritis/rheumatoid arthritis, chronic pain, cancer, chronic renal disease, inflammatory bowel diseases, mood disorders and attention deficit disorders). We will rely in the authors’ definition of chronic disease and presenting, or at risk of presenting, a concomitant mental health problem (eg, mood disorders, depression, anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, panic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder). |

| Intervention (I) | Digital health technologies, including but not limited to: telemedicine/teleconsultation, patient portal, electronic health record, web-based/internet intervention or smartphone applications. |

| Comparator (C) | No intervention, usual care and any other (digital or non-digital) intervention. |

| Outcomes (O) | Prevalence of mental health problems; scores of depression, anxiety or other mental health problem; quality of life; specific clinical indicators (eg, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) for diabetes); patient satisfaction; impact on care utilisation (eg, emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalisation and outpatient consultations); and costs (for the individual and the health system). |

Literature search

An experienced medical information specialist developed and tested the search strategies through an iterative process in consultation with the review team and knowledge users. Using the OVID platform, we searched Ovid MEDLINE, including Epub Ahead of Print and In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Embase Classic+Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and the Health Technology Assessment Database. We also searched CINAHL (EBSCO) and Web of Science. All searches were performed on 11 June 2020. We used a combination of controlled vocabulary (eg, “Chronic Disease”, “Mood Disorders” and “Internet”) and keywords (eg, “cancer”, “anxiety” and “telehealth”) and adjusted vocabulary and syntax across the databases. We applied a systematic review filter to all searches except for the Cochrane databases, where it is not required. Specific details regarding the strategies appear in online supplemental file 1).

bmjopen-2020-044437supp001.pdf (96.8KB, pdf)

Study selection, data extraction and synthesis

Six reviewers individually performed screening for titles, abstracts and then full text using a standardised form pilot-tested by all reviewers on 25 citations. All citations were reviewed by two reviewers independently at the first level of screening. We developed a standardised extraction form that included study characteristics (eg, authors, country and design), intervention characteristics (eg, type of digital intervention) and outcomes reported. A senior reviewer reviewed all full-text citations for inclusion. Single reviewers extracted data, which were then confirmed by a senior reviewer. We resolved discrepancies through discussion. We report data using a narrative approach that includes tables of study characteristics, intervention characteristics and mental health outcomes.

Critical appraisal

We used the AMSTAR 2 tool to critically appraise each included review.11 This revised version of the AMSTAR tool was developed for the evaluation of systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions. This tool has good inter-rater reliability, is widely used for healthcare research and uses a four-level rating of overall confidence. A single reviewer rated the critical appraisal tool and all judgements were verified by a second author.11

Patient and public involvement

A panel of knowledge users (patients and clinicians) was involved throughout the research process, from funding acquisition to publication. The panel will also be involved in subsequent dissemination activities.

Results

Characteristics of included reviews

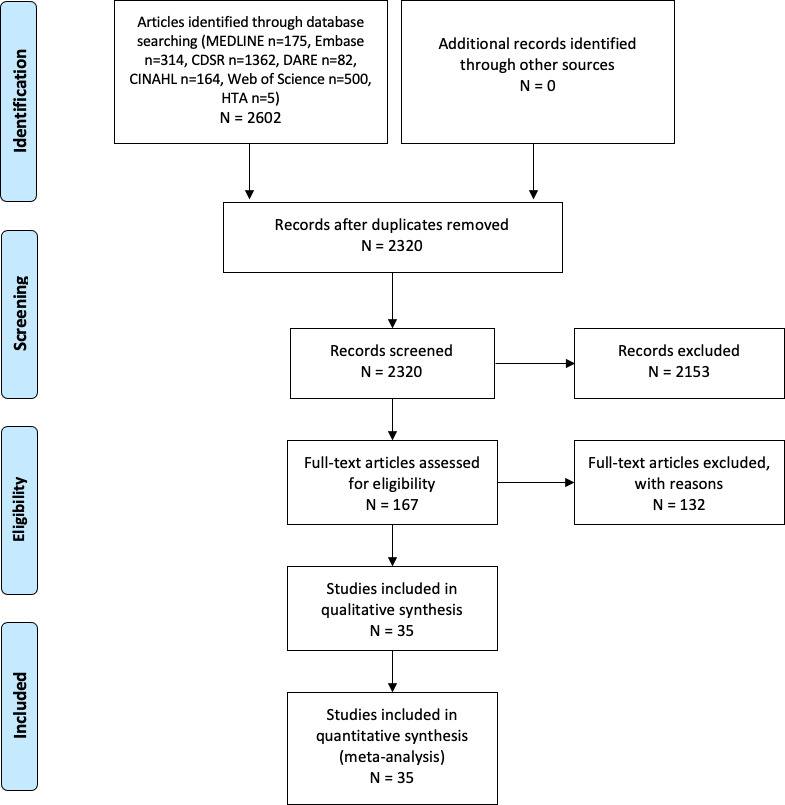

Our search strategy identified 2320 individual citation. Following screening of titles and abstracts, we excluded 2153 records. We excluded an additional 132 citations during full-text screening, resulting in a total of 35 citations included in our review (figure 1).12–46Of these reviews, there were 17 systematic reviews, 17 systematic reviews with meta-analysis and one integrative review, totalising 702 primary studies with a total sample of 50 692 participants.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study inclusion process. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Most reviews described digital interventions performed in a specialised care setting (42%) and targeted an adult population (83%). They were looking at interventions to manage and treat a mental health problem (60%), testing web-based and internet interventions (32%) by comparing them with usual care (48%), for people affected with cancer or various chronic diseases (77%). We present the complete description of included reviews in table 2. A presentation of the reviews by technology used in available in additional table 1.

Table 2.

Description of included reviews

| Author, year | Review design | No. of primary studies, design | No. of patients (pooled) | Type of chronic diseases | Type of digital technology interventions | Depression outcomes | Anxiety outcomes | Other mental health outcomes |

| Chronic disease cluster | ||||||||

| Beatty 201314 |

SR | 24 Experimental |

NR | Chronic physical diseases | Web-based/internet intervention, app, email and relemedicine/teleconsultation. | Improvement between groups comparison. Improvement within group (moderate effect size). Improvement sustained at 12-month follow-up. iCBT with and without therapist showed no differences between groups. iCBT showed no difference when compared with group CBT. |

Improvement at 3 months and at 12 months. | NR |

| Charova 201516 |

SR with MA | 11 Experimental |

1348 | Any chronic disease with comorbid MH disorder | Web-based/internet intervention. | DW 0.31; 95% CI 0.17 to 0.45; p<0.01. | NR | NR |

| Clari, 202018 | SR | 1 Mixed |

84 | COPD | Telemedicine/teleconsultation. | No difference between groups. | No difference between groups. | Qualitative data: promoted active acceptance of their disease/improved the awareness of their physical sensations /helped identify signs and symptoms /improvement of the management of acute events. |

| Eccleston, 201919 | SR with MA | 14 Experimental |

2012 | Chronic pain | Web-based/internet intervention, app and telemedicine/teleconsultation. | SMD=−0.26 (95% CI −0.87 to 0.36). | SMD=−0.48 (95% CI −1.22 to 0.27). | NR |

| Hedman, 201223 | SR with MA | 108 Experimental |

NR | Any | Web-based/internet intervention. | MD=0.94 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.11) large effect size, within groups. | MD=1.12 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.62), large effect size. | NR |

| McCombie, 201531 | SR | 29 Mixed |

3935 | Chronic physical diseases | Web-based/internet intervention. | Improvement of depression scores (4/8). | Improvement (2/7). | NR |

| Mehta, 201833 | SR with MA | 25 Experimental |

3450 | Any | Web-based/internet intervention and email. | Improved depression symptoms with small to medium effect size. Therapist-guided ICBT showed larger effect size than self-guided ICBT. |

Improved anxiety, similar effect size than usual care. | NR |

| Mikolasek, 201834 | SR with meta-analysis | 17 Experimental |

1855 | Chronic physical diseases | Web-based/internet intervention. | Active control: 2/7 showed superior effectiveness; 4/7 equal effectiveness; 1/7 inferior effectiveness. Usual care: 1/4 showed superior effectiveness; 3/4 showed equal effectiveness. |

Active control: 2/7 showed superior effectiveness; 4/7 equal effectiveness; 1/7 inferior effectiveness. Usual care: 1/4 showed superior effectiveness; 3/4 showed equal effectiveness. |

NR |

| Palacios, 201736 | SR | 7 Experimental |

1321 | Chronic physical diseases | Web-based/internet intervention, app, email and text message. | PHQ-9 score mean from 12 (post) to 8.4 (follow-up). | NR | NR |

| Paul, 2013 37 | SR | 36 Experimental |

NR | Any chronic disease with comorbid MH disorder. | Web-based/internet intervention and online chat. | Improved depression in comparison between groups. | Improved anxiety in comparison with control. | Mixed results in psychosocial outcomes. |

| Toivonen, 201740 | SR | 16 Experimental |

NR | Any | Web-based/internet intervention, email and online chat. | Improved depression symptoms with a small effect size. | Improved anxiety symptoms with a small effect size. | NR |

| van Beugen, 201442 | SR with MA | 23 Experimental |

2299 | Any | Web-based/internet intervention, app, email, text message and online chat. | SMD=0.21 (95% CI: 0.08 to 0.34). | SMD=0.17 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.32). | General distress: SMD=0.21 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.41). |

| Vugts, 2018 43 | SR with MA | 46 Experimental |

NR | Chronic physical diseases | Web-based/internet intervention, email, text message, online chat and telemedicine/teleconsultation. | SMD=−0.18 (95% CI −0.28 to −0.07). SMD=−0.18 (95% CI−0.28 to −0.07) passive control (post). SMD=−0.29 (95% CI −0.48 to −0.10) passive control (follow-up). SMD=0.14 (95% CI −0.37 to 0.09) active control (post). SMD=0.31 (95% CI: −0.78 to 0.16) active control (follow-up). |

NR | NR |

| Cancer cluster | ||||||||

| Agboola, 201512 |

SR | 20 Experimental |

3789 | Cancer | Web-based/internet, app, virtual reality, text message, online chat and telemedicine/teleconsultation. | Heterogeneous studies no pooling possible. | Improvement in anxiety symptoms (3/8). | NR |

| Bártolo, 201913 |

SR | 8 Experimental |

1016 | Cancer | Web-based/internet, patient portal, app, email and telemedicine/teleconsultation. | Improvement in depression symptoms 3 weeks postinterventions. Small effect size. The telephone intervention yielded medium effect size improvement. |

NR | Improvement in global distress, small effect size. |

| Bouma, 201515 |

SR | 16 Experimental |

2620 | Cancer | Web-based/internet intervention. | Improvement on depression symptoms (1/7) (between groups). | Improvement in anxiety symptoms (2/10). | Improvement on quality of life (3/11). |

| Chen, 2018 17 | SR with MA | 20 Experimental |

2190 | Cancer | Web-based/internet intervention and telemedicine/teleconsultation. | SMD=1.29 (95% CI 2.28 to 0.30). | SMD=0.09 (95% CI 0.22 to 0.04). | Distress: SMD = ¼ 0.25,(95% CI 0.40 to 0.10, p<0.001). |

| Forbes, 201921 | SR | 16 Experimental |

2446 | Cancer | Web-based/internet intervention, email and online chat. | Improvement of depression score within group. Better improvement with CBT compared with online forum. |

NR | Psychological distress: effect size larger with ICBT compared with forum. |

| Fridriksdottir, 201722 | SR | 20 Experimental |

NR | Cancer | Web-based/internet intervention and email. | Improvement in depression symptoms (2/10). | Improvement in anxiety symptoms (4/10). | Improvement on psychological distress (3/8). |

| Kim, 2015 24 | SR with MA | 37 Experimental |

NR | Cancer | Web-based/internet intervention, email, text message, online chat and telemedicine/teleconsultation. | Hedges’ g=−0.169 (−0.282 to −0.055). | Hedges’ g=−0.293 (−0.465 to −0.122). | QOL: Hedges' g=−0.221 (−0.359 to −0.084). |

| Kim, 2017 25 | SR with MA | 19 Mixed |

2381 | Cancer | Web-based/internet intervention and telemedicine/teleconsultation. | d=−0.07, p=0.284 (post). d=−0.2, p=0.477 (follow-up). |

d=−0.2, p=0.132. | NR |

| Lin, 202027 | Mixed | 16 Mixed |

1053 | Cancer | Web-based/internet intervention, app, email and text message. | Improvement of depression scores (5/11). | Improvement of anxiety scores (5/11). | NR |

| McCaughan, 201730 | SR | 6 Experimental |

492 | Cancer | Web-based/internet intervention, patient portal, email and online chat. | SMD=−0.37 (95% CI −0.75 to 0.00). | Mean 0. 4 lower at end of intervention (95% CI 6.42 lower to 5.62 higher). MD=−0.40 (95% CI −6.42 to 5.62); low-quality evidence between groups. |

NR |

| Qan'ir, 2019 38 | SR with MA | 10 Experimental |

1124 | Cancer | Web-based/internet intervention, app and online chat. | Improvement of depression score (between group) (2/7). Improvement of depression score (within group)(1/7). |

Improvement of anxiety score (between group) (1/5). Improvement of anxiety score (within group) (1/5). |

NR |

| Ugalde, 201541 | SR | 4 Experimental |

NR | Cancer | Web-based/internet intervention. | NR | NR | Improved self-efficacy for regulating negative mood. |

| Wang, 2020 44 | SR with MA | 7 Experimental |

1220 | Cancer | Web-based/internet intervention, app and email. | SMD=−0.58, 95% CI (−1.12 to –0.03), p=0.04) (between groups). | SMD=−1.03 (95% CI − 2.63 to 0.57) (between groups). | NR |

| Zeng, 2019 46 | SR with MA | 6 Mixed |

NR | Cancer | Virtual reality. | WMD=−1.11 (Z-scores=1.05, p=0.29). | SMD=−3.03 (95% CI=−6.20 to 0.15)). | NR |

| Youth and children cluster | ||||||||

| Fisher, 2019 20 | SR with MA | 10 Mixed |

697 | Chronic pain | Web-based/internet intervention and app. | SMD 0.04 (95% CI −0.18 to 0.26). | SMD 0.53 (95% CI −0.63 to 1.68). | NR |

| Lopez-Rodriguez, 202028 | SR | 8 Mixed |

286 | Cancer | App and virtual reality. | Improved depression (3/3). | Improved anxiety (2/3). | NR |

| McGar, 2019 32 | SR | 22 Experimental |

1764 | Chronic physical diseases | Web-based/internet intervention. | Improved depression symptoms (3/7). | Improved anxiety (4/5) (post). | Improved PTSD symptoms (2/3) (post). |

| Tang, 2018 39 | SR with MA | 4 Experimental |

404 | Chronic pain | Web-based/internet intervention. | MD=0.23 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.43) (within group). MD=0.02 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.22) (between group). SMD=0.02 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.22, p=0.86) (follow-up). |

SMD=3.24 (95% CI 1.88 to 4.61) (within group). SMD=0.41 (95% CI 1.79 to 0.98) (between group). |

NR |

| Mental health cluster | ||||||||

| Lewis, 2018 26 | SR with MA | 10 Experimental |

720 | PTSD | Web-based/internet intervention. | SMD=−0.61 (95% CI −1.17 to −0.05)) (between groups/post). MD=−8.95, 95% CI −15.57 to −2.33) (between groups/follow-up). |

SMD=−0.67 (95% CI −0.98 to −0.36)(between groups/post). MD=−12.59 (95% CI −20.74 to −4.44)(between groups/follow-up). |

PTSD SMD=−0.60 (95% CI −0.97 to −0.24) (between groups/post). RR=0.53 (95% CI 0.28 to 1.00) (between groups/post). |

| Mayo-Wilson, 201329 | SR with MA | 43 Experimental |

8403 | Anxiety | Web-based/internet intervention, email, text message and telemedicine/teleconsultation. | NR | SMD=0.79 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.96) (internet delivered). | NR |

| Olthuis, 201635 | SR with MA | 38 Experimental |

3214 | Anxiety | Web-based/internet intervention, app, email, and nline chat. | NR | *RR=3.75 (95% CI 2.51 to 5.60) (generalised anxiety). SMD=−1.06 (95% CI −1.29 to −0.8) (disorder specific anxiety). |

NR |

| Wickersham, 201945 | SR | 5 Experimental |

653 | PTSD | App | NR | NR | No improvement in PTSD between groups when compared with usual care. |

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; dw, Cohen’s effect size; iCBT, internet-based cognitive behavior therapy; MA, meta-analysis; MH, mental health; NR, not reported; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; QOL, quality of life; RR, risk ratio; SMD, standardized mean difference; SR, systematic review; WMD, weighted mean difference.

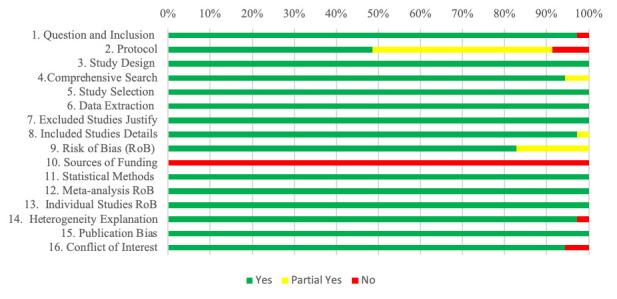

The overall confidence ratings of the AMSTAR 2 tool were mostly high or moderate (31/35) with a limited number of low ratings (4/35) and no critically low rating (table 3). A small percentage of the AMSTAR 2 items were not reported in the included reviews with the exception of the source of funding of primary studies in the included reviews (0%) (figure 2).

Table 3.

Critical appraisal of the included reviews

| 1. Question and inclusion | 2. Protocol | 3. Study design | 4. Comprehensive search | 5. Study selection | 6. Data extraction | 7. Excluded studies justify | 8. Included studies details | 9. Risk of bias (RoB) | 10. Sources of funding | 11. Statistical methods | 12. Meta-analysis RoB | 13. Individual studies RoB | 14. Heterogeneity explanation | 15. Publication bias | 16. Conflict of interest | Overall confidence rating | |

| Agboola 201512 | N | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | N | N/A | Y | Low |

| Bartolo 2019 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Moderate |

| Beatty 2012 | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | N | Moderate |

| Bouma 2019 | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Moderate |

| Charova 201516 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate |

| Chen 201817 | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate |

| Clari 202018 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | High |

| Eccleston 201919 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Fisher 201920 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Forbes 201921 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | High |

| Fridriksdottir 2017 | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Moderate |

| Hedman 201223 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low |

| Kim 201524 | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate |

| Kim 201725 | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Moderate |

| Lewis 201826 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Lin 202027 | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Moderate |

| Lopez-Rodriguez 202028 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Mayo-Wilson 201329 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| McCaughan 201730 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| McCombie 201531 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Low |

| McGar 201932 | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Moderate |

| Mehta 201933 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate |

| Mikolasek 201834 | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Moderate |

| Olthuis 201635 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate |

| Palacios 201736 | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Moderate |

| Paul 201337 | Y | PY | Y | PY | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | PY | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Moderate |

| Qan'ir 201938 | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Moderate |

| Tang 201839 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Toivonen 201740 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Low |

| Ugalde 2017 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | High |

| van Beugen 201442 | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate |

| Vaugts 201843 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Wang 202044 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Wickersham 201945 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | High |

| Zeng 201946 | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate |

NA, not applicable; N, no; PY, partial yes; Y, Yes.

Figure 2.

Overall critical appraisal of the included studies using the AMSTAR 2 tool.

We structured our synthesis according to four population clusters: (1) chronic diseases; (2) cancer; (3) mental health; and (4) children and youth. The mental health outcomes found in the included reviews were mainly depression and anxiety symptoms, assessed through heterogeneous outcomes measures. The results are further presented by type of reporting (quantitative or narrative).

Chronic diseases cluster

We identified 13 reviews referring to people with various chronic diseases (table 2). Six of the 13 reviews reported their results using pooled difference of score mean.16 19 23 36 42 43 The majority of the reviews presenting quantitative results reported improvement of depressive symptoms (5/6), but only one identified improvement in anxiety symptoms (1/3). One review reported improvement of general distress.42 The synthesis with the largest effect size included 108 primary studies with only web-based and internet cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) interventions.23 Most of the reviews that yielded narrative results reported improvement of depressive symptoms (6/7), improvement in anxiety symptoms (6/7) and psychosocial outcomes (1/1). Only one report of inferior effectiveness was identified for both depression and anxiety symptoms.18 Narrative reports described a small to moderate effect size within group in depression and anxiety symptoms. One integrative review report based on qualitative data described that digital health interventions for people with chronic diseases promoted active acceptance of their disease, improved the awareness of physical manifestations of the disease, helped identify signs and symptoms of worsening and improved management of acute events.18 The types of digital technology that had the most reports of improvements were web-based interventions, followed by email. Virtual reality and patient portal had no reports of improvements on outcomes when used (table 4).

Table 4.

Studies reporting improvements classified by the type of digital technology used

| Chronic diseases cluster | Cancer cluster | Children and youth cluster | Mental health cluster | |||||||||

| Depression | Anxiety | Other | Depression | Anxiety | Other | Depression | Anxiety | Other | Depression | Anxiety | Other | |

| Web-based interventios | 23 42 43 16 36 31 14 40 33 34 37 | 23 31 14 40 33 34 37 | 37 | 17 44 24 21 13 | 17 30 44 24 | 24 17 21 41 13 | 20 39 | 20 39 32 | 32 | 26 | 29 35 26 | 26 |

| Patient portal | 30 | |||||||||||

| Smartphone application | 42 36 14 | 14 | 44 | 44 | 20 28 | 20 28 | 35 | |||||

| Virtual reality | 28 | 28 | ||||||||||

| 42 43 36 14 40 33 | 14 40 33 | 44 24 21 13 | 30 44 24 | 21 24 13 | 29 35 | |||||||

| Text messae | 42 43 36 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 29 | |||||||

| Online chat | 42 43 40 37 | 40 37 | 37 | 24 21 | 30 24 | 21 24 | 35 | |||||

| Telemedicine/teleconsultation | 42 14 | 14 | 17 24 13 | 17 24 | 24 17 13 | 29 | ||||||

Cancer cluster

We identified 14 reviews referring to people with cancer (table 2). Quantitative reporting was present in six reviews.17 24 25 30 44 46 Four (4/6) of those reported improvements of depressive symptoms, and half showed improvements in anxiety symptoms (3/6). Other quantitative reports of improvements in mental health outcomes included distress and quality of life. The quantitative report with the largest effect size included 20 primary studies, a total sample of 2190 participants, and looked at web-based and teleconsultations CBT interventions.17 Reviews that yielded narrative results reported improvements of depression symptoms (6/7), anxiety symptoms (5/5), distress (3/3), quality of life (1/1) and mood regulation (1/1). Pooling of the results was impossible in one review due to heterogeneity.12 The narrative outcome reports described a small effect size within group for depression and anxiety symptoms.21 The types of digital intervention that had the most reports of improvements were web-based interventions and email. Virtual reality had no reports of improvements (table 4)

Children and youth cluster

We identified four reviews related to digital health interventions targeting children and youth (table 2). Two reviews reported a quantitative synthesis presenting mixed effects: one showing within group improvements in depression and anxiety and both showing no between group difference on these outcomes.20 39 As for narrative syntheses, both reported improvements on depression and anxiety, with one of the reviews reporting on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms improvement.28 32 The limited reports on improvement for this population was associated with the used of web-based interventions (3/4), smartphone applications (2/4) and virtual reality (1/4) (table 4).

Mental health cluster

We identified four reviews related to population with mental health conditions (table 2). The quantitative reports showed improvements in anxiety symptoms for generalised anxiety disorder and disease-specific anxiety (3/3), improvements of depression symptoms (1/1) and PTSD symptoms (1/1). The only narrative report for that cluster showed no improvement on PTSD symptoms between groups.45 The types of digital technology that had the most reports of improvement were web-based interventions (3/4) and email (2/4) with unique reports for smart phone applications, text messages and online chat (table 4).

Discussion

We conducted a rapid review of systematic reviews to identify digital health interventions effective to prevent, detect or manage mental health problems in individuals with a pre-existing chronic disease. In total, 35 reviews were included.

Our findings are in line with the extensive evidence that internet CBT interventions are effective and comparable to face-to-face interventions.47 Our analysis adds to the body of evidence on effectiveness regarding concomitant chronic diseases in four clusters of population. For people with various chronic diseases, most of the included reviews showed that digital health interventions have a positive effect on depression, anxiety, distress and psychosocial outcomes. The data showed that interventions have a moderate effect size within the intervention group and a small effect size when compared with usual care. For the cluster of population affected by cancer (including survival), evidence already exists regarding the effectiveness of digital mental health interventions with positive to mixed effect.48 Our data also showed that digital health interventions are effective in improving depression, anxiety, distress, quality of life and mood regulation. Also, teleconsultation and web-based interventions were the most effective modes of delivery for this population. Regarding the paediatric population, a meta-review targeting digital mental health interventions for children and youth reported a positive effect for the use of web-based CBT but only in children and youth with anxiety and depression with no other concomitant conditions.49 Quantitative data were inconclusive regarding effectiveness and effect size within group but showed a non-inferiority when compared with usual care. All included reviews in this population combined smartphone applications and web-based interventions, making it difficult to draw any conclusion about the most effective mode of delivery for the intervention at this level of analysis. For the mental health population, the included reviews emphasised that digital health interventions are effective for individuals with a combination of physical and mental conditions, as well as for people with multiple mental health problems.

Available evidence suggests that digital health interventions such as web-based CBT, email messaging and teleconsultation could be effective and provide an alternative to face-to-face psychological interventions to prevent and manage mental health problems in people affected by cancer or other chronic diseases. In line with our findings, Torous et al50 described that offering health provider-directed synchronous digital health solutions such as teleconsultation is the first step to increase access to quality mental healthcare in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of these innovations support the care of people in need of special attention, including those with chronic illnesses. Due to smaller effect size, we were not able to draw any conclusion related to the other forms of digital health interventions such as online chat, text message and smartphone applications. These types of digital health interventions are asynchronous; they may improve access and promote low-threshold alternatives to mental health consultations within the healthcare system. However, more evidence regarding implementation and evaluation to be safe for patients would be required.50 Included reviews that looked at other intervention delivery methods reported smaller to no effect, but it could be related to heterogeneity of the data. Even with reports of effectiveness, there is still a lack of evidence of economic data to perform a proper cost analysis of digital health interventions.51 52

This review was rapidly performed to inform knowledge users in a timely matter. In line with recommendations for rapid reviews,53 methods that would lead to a systematic review were not followed as strictly to allow for a faster methodology. We limited the scope of the search to the aim of the study by looking at limited databases and imposing a period of publication. These methodological choices resulted in the ability to perform an appropriate and structured study selection, data extraction and critical appraisal.

This rapid review of reviews has limitations. In order to respect the requirements of this urgent strategic call in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and provide stakeholders and decision makers with up-to-date evidence, we limited the search to the most relevant databases and the last 10 years. Despite our best efforts, we may have missed some publications. Moreover, we did not assess the overlapping of primary studies in the included reviews. While we rigorously followed guidance for the conduct of rapid reviews, results from this study should be interpreted with caution. Further analyses will be required for stronger recommendations, notably by considering the potential publication bias, as well as other factors that could decrease the level of confidence in the reported effects.

Future research on digital mental health interventions should provide economic data to give a broader insight for possible implementation. Research on digital mental health interventions could also further assess the safety and limitations of asynchronous and self-administered technologies. Finally, efforts should be put on developing a structured method to report what kind of technology (eg, internet based and smartphone app) and function (eg, communication, intervention and evaluation) were used in the intervention. A structured method of reporting would improve the evidence precision and knowledge implementation.

Conclusion

This rapid review outlines the current evidence regarding the use of digital health interventions for people with a concomitant chronic disease. For individuals with a chronic disease or cancer, health provider directed digital interventions (eg, teleconsultation) are effective and safe. However, further analyses of this large body of evidence are required in order to provide precise recommendations regarding relevance for specific populations (such as children and youth), modes of delivery and type of intervention. In response to the current crisis, but also to better prepare for the postcrisis and future crises, digital technologies could be used to prevent and manage mental health problems in people living with chronic conditions, with consideration for the age group and type of technology used.

bmjopen-2020-044437supp002.pdf (321.3KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the knowledge users for their support throughout this review and the SPOR Evidence Alliance for their support.

Footnotes

Contributors: MS, AL, M-PG, M-CC, MBe, NB, PC, CA, AL and GC identified the need for this study and contributed to its conception and design. BS developed and conducted the search strategy. MS, M-PG, MBo, MD, MG and JT conducted the data collection and analysis. MS developed the first draft of the report. All authors contributed to writing and editing and gave the final approval of the version submitted.

Funding: This review was funded by the Canadian Institute for Health Research in the Operating Grant: Knowledge Synthesis: COVID-19 in Mental Health & Substance Use. Grant number: 202005CMS-442711-CMV-CFBA-111141.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request with the first (MS) or last (MPG) authors.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation . Global status report on noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman DP, Perry GS, Strine TW. The vital link between chronic disease and depressive disorders. Prev Chronic Dis 2005;2:A14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naylor C, Parsonage M, McDaid D. Long-term conditions and mental health: the cost of co-morbidities. The King’s Fund and Centre for Mental Health 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shigemura J, Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, et al. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2020;74:281–2. 10.1111/pcn.12988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García-Lizana F, Muñoz-Mayorga I. Telemedicine for depression: a systematic review. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2010;46:119–26. 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00247.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards D, Richardson T. Computer-Based psychological treatments for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2012;32:329–42. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garritty CGG, Kamel C, King VJ. Cochrane rapid reviews. : CR R, . Interim guidance from the Cochrane rapid reviews methods group. Cochrane Collaboration, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein KM, Fisher DA, Wu RR, et al. An electronic family health history tool to identify and manage patients at increased risk for colorectal cancer: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2019;20:576. 10.1186/s13063-019-3659-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017;358:j4008. 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agboola SO, Ju W, Elfiky A, et al. The effect of technology-based interventions on pain, depression, and quality of life in patients with cancer: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e65. 10.2196/jmir.4009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bártolo A, Pacheco E, Rodrigues F, et al. Effectiveness of psycho-educational interventions with telecommunication technologies on emotional distress and quality of life of adult cancer patients: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 2019;41:870–8. 10.1080/09638288.2017.1411534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beatty L, Lambert S. A systematic review of Internet-based self-help therapeutic interventions to improve distress and disease-control among adults with chronic health conditions. Clin Psychol Rev 2013;33:609–22. 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouma G, Admiraal JM, de Vries EGE, et al. Internet-based support programs to alleviate psychosocial and physical symptoms in cancer patients: a literature analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2015;95:26–37. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charova E, Dorstyn D, Tully P, et al. Web-based interventions for comorbid depression and chronic illness: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare 2015;21:189–201. 10.1177/1357633X15571997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y-Y, Guan B-S, Li Z-K, et al. Effect of telehealth intervention on breast cancer patients' quality of life and psychological outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare 2018;24:157–67. 10.1177/1357633X16686777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clari M, Conti A, Fontanella R, et al. Mindfulness-based programs for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a mixed methods systematic review. Mindfulness 2020;11:1848–67. 10.1007/s12671-020-01348-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eccleston C, Fisher E, Brown R. Psychological therapies (internet-delivered) for the management of chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher E, Law E, Dudeney J, et al. Psychological therapies (remotely delivered) for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;4:CD011118. 10.1002/14651858.CD011118.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forbes CC, Finlay A, McIntosh M, et al. A systematic review of the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of online supportive care interventions targeting men with a history of prostate cancer. J Cancer Surviv 2019;13:75–96. 10.1007/s11764-018-0729-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fridriksdottir N, Gunnarsdottir S, Zoëga S, et al. Effects of web-based interventions on cancer patients' symptoms: review of randomized trials. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:337–51. 10.1007/s00520-017-3882-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2012;12:745–64. 10.1586/erp.12.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim AR, Park H-A. Web-based self-management support interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Stud Health Technol Inform 2015;216:142–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim SH, Kim K, Mayer DK. Self-management intervention for adult cancer survivors after treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum 2017;44:719–28. 10.1188/17.ONF.719-728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis C, Roberts NP, Bethell A, et al. Internet-based cognitive and behavioural therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;12:CD011710. 10.1002/14651858.CD011710.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin H, Ye M, Chan SW-C, et al. The effectiveness of online interventions for patients with gynecological cancer: an integrative review. Gynecol Oncol 2020;158:143–52. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.04.690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez-Rodriguez MM, Fernández-Millan A, Ruiz-Fernández MD, et al. New technologies to improve pain, anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with cancer: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:19. 10.3390/ijerph17103563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayo-Wilson E, Montgomery P. Media-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy and behavioural therapy (self-help) for anxiety disorders in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;9:CD005330. 10.1002/14651858.CD005330.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCaughan E, Parahoo K, Hueter I, et al. Online support groups for women with breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;15:CD011652. 10.1002/14651858.CD011652.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCombie A, Gearry R, Andrews J, et al. Computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for psychological distress in patients with physical illnesses: a systematic review. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2015;22:20–44. 10.1007/s10880-015-9420-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGar AB, Kindler C, Marsac M. Electronic health interventions for preventing and treating negative psychological sequelae resulting from pediatric medical conditions: systematic review. JMIR Pediatr Parent 2019;2:e12427. 10.2196/12427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehta S, Peynenburg VA, Hadjistavropoulos HD. Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic health conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Med 2019;42:169–87. 10.1007/s10865-018-9984-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mikolasek M, Berg J, Witt CM, et al. Effectiveness of mindfulness- and relaxation-based eHealth interventions for patients with medical conditions: a systematic review and synthesis. Int J Behav Med 2018;25:1–16. 10.1007/s12529-017-9679-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olthuis JV, Watt MC, Bailey K, et al. Therapist-supported Internet cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;3:CD011565. 10.1002/14651858.CD011565.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palacios J, Lee GA, Duaso M, et al. Internet-delivered self-management support for improving coronary heart disease and Self-management-Related outcomes: a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2017;32:E9–23. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paul CL, Carey ML, Sanson-Fisher RW, et al. The impact of web-based approaches on psychosocial health in chronic physical and mental health conditions. Health Educ Res 2013;28:450–71. 10.1093/her/cyt053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qan'ir Y, Song L. Systematic review of technology-based interventions to improve anxiety, depression, and health-related quality of life among patients with prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2019;28:1601–13. 10.1002/pon.5158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang W-X, Zhang L-F, Ai Y-Q, et al. Efficacy of internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for the management of chronic pain in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2018;97:e12061. 10.1097/MD.0000000000012061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toivonen KI, Zernicke K, Carlson LE. Web-based mindfulness interventions for people with physical health conditions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e303. 10.2196/jmir.7487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ugalde A, Haynes K, White V. Self-guided psychological interventions for people with cancer: a systematic review. Asia-Pacific J Clin Oncol 2015;4:146. [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Beugen S, Ferwerda M, Hoeve D, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with chronic somatic conditions: a meta-analytic review. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e88. 10.2196/jmir.2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vugts MAP, Joosen MCW, van der Geer JE, et al. The effectiveness of various computer-based interventions for patients with chronic pain or functional somatic syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2018;13:e0196467. 10.1371/journal.pone.0196467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y, Lin Y, Chen J, et al. Effects of Internet-based psycho-educational interventions on mental health and quality of life among cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 2020;28:2541–52. 10.1007/s00520-020-05383-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wickersham A, Petrides PM, Williamson V, et al. Efficacy of mobile application interventions for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Digital Health 2019;5:205520761984298. 10.1177/2055207619842986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeng Y, Zhang J-E, Cheng ASK, et al. Meta-Analysis of the efficacy of virtual Reality-Based interventions in cancer-related symptom management. Integr Cancer Ther 2019;18:1534735419871108. 10.1177/1534735419871108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Andersson G. Internet-administered cognitive behavior therapy for health problems: a systematic review. J Behav Med 2008;31:169–77. 10.1007/s10865-007-9144-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McAlpine H, Joubert L, Martin-Sanchez F, et al. A systematic review of types and efficacy of online interventions for cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:283–95. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hollis C, Falconer CJ, Martin JL, et al. Annual research review: digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems - a systematic and meta-review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2017;58:474–503. 10.1111/jcpp.12663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Torous J, Jän Myrick K, Rauseo-Ricupero N, et al. Digital mental health and COVID-19: using technology today to accelerate the curve on access and quality tomorrow. JMIR Ment Health 2020;7:e18848. 10.2196/18848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iribarren SJ, Cato K, Falzon L, et al. What is the economic evidence for mHealth? A systematic review of economic evaluations of mHealth solutions. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170581. 10.1371/journal.pone.0170581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Badawy SM, Kuhns LM. Economic evaluation of text-messaging and smartphone-based interventions to improve medication adherence in adolescents with chronic health conditions: a systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016;4:e121. 10.2196/mhealth.6425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garritty C, Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, et al. Cochrane rapid reviews methods group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2021;130:13–22. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-044437supp001.pdf (96.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-044437supp002.pdf (321.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request with the first (MS) or last (MPG) authors.