Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a frequent and underdiagnosed disease in hypertensive individuals who experience cardiovascular events. The aim of this study was to define the best model that combined the ambulatory blood pressure (BP) monitoring (ABPM), anthropometric, sociodemographic, and biological variables to identify moderate to severe OSA. A total of 105 ABPM‐confirmed hypertensive patients were evaluated using their clinical histories, blood analyses, ABPM, and home respiratory polygraphic results. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the significant variables. The best model included sex, presence of obesity (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 and abdominal obesity), mean daytime BP, mean nocturnal heart rate, and minimal diastolic nighttime BP to achieve an area under the curve of 0.804. Based on this model, a validated scoring system was developed to identify the patients with an apnea‐hypopnea index ≥15. Therefore, in untreated hypertensive patients who snored, ABPM variables might be used to identify patients at risk for OSA.

The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in the adult population aged 30 to 70 years is approximately 26% to 34% in men and 17% to 28% in women.1, 2 This prevalence is especially high in hypertensive individuals (30%–50%3) and is significantly increased in hypertensive patients who snore.4 Sleep apnea is a disorder characterized by repeated episodes of upper airway obstruction, which can result in poor health status caused by the cardiovascular consequences.5 OSA has been clinically confirmed as a cause of hypertension independently of other clinical variables, such as weight,6, 7 especially in individuals younger than 60 years.8, 9

This syndrome has been associated with significant damage to target organs in hypertensive patients. OSA is associated with a high prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy,10, 11 ischemic heart disease,12, 13 heart failure,14, 15 arrhythmia,16, 17 increased intima‐media thickness,18, 19 and stroke.20, 21 Based on the evidence that links OSA with hypertension and cardiovascular events and the fact that the syndrome is largely underdiagnosed, approximately 90% of affected individuals are unaware that they have the disease; physicians who treat hypertensive individuals need diagnostic tools that are easy to perform for OSA identification. Twenty‐four‐hour ambulatory blood pressure (BP) monitoring (ABPM) is frequently used in the management of hypertensive individuals and may be used to identify patients at risk for OSA. We hypothesized that in untreated hypertensive snorers, a high OSA prevalence could be expected and that it was likely to be >70%. In these patients, ABPM variables may be helpful in the identification of moderate to severe OSA with adequate sensitivity and specificity. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine which ABPM variables may be used either individually or in combination with other variables to identify OSA in untreated hypertensive snorers, resulting in their active treatment.

Methods

Study Design

An observational prospective study was performed to determine which ABPM variables could be used to identify OSA in untreated hypertensive snorers.

Sample Size

This study assumed that a sensitivity of at least 80% would be obtained and that a precision of 10% would be fixed. Therefore, to estimate the sensitivity of the model and the feasibility of using select ABPM variables as screening parameters and to predict their 95% confidence interval (CI), a minimum of 70 patients with OSA was needed. An OSA prevalence of 70% was expected among the untreated hypertensive snorers; therefore, a minimum of 100 patients was needed. In addition, 5% of the patients were expected to be lost to follow‐up or to have missing information; therefore, the minimum sample size was 105 patients. A sample of 21 untreated hypertensive snorers (nine of these individuals had an apnea‐hypopnea index [AHI] ≥15 events per hour) were recruited for external validation. The external validation indicated a minimum precision of 0.20 with the 95% CI estimation for the area under the curve of the model in an independent sample selected from the same population.

Study Patients

From April 2007 to October 2011, consecutive patients with newly diagnosed hypertension and snorers from four primary care centers in Lleida, Spain, were included in the study. Office hypertension was diagnosed according to standard criteria (>140/90 mm Hg).24 Snoring status was defined as a condition as described by the patient and/or partner when they were questioned. All of the patients were aged 18 to 70 years and had untreated newly diagnosed hypertension. We excluded patients who had been previously diagnosed with cardiac arrhythmia. The study protocol was approved by the investigation center's committee, and all of the patients provided written informed consent.

Protocol Design

In the primary care centers, the patients with newly diagnosed office hypertension who were snorers were referred to the Cardiovascular Risk Unit of Santa Maria Hospital of Lleida (Spain). Their clinical and anthropometric variables were recorded, including age, sex, BP, body mass index (BMI), and abdominal, waist, and neck circumferences. The degree of the patients’ self‐reported sleepiness/drowsiness was analyzed using the Spanish validated version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.23 After fasting overnight, venous blood samples and 24‐hour ABPM measurements were obtained from all of the participants. ABPM was performed in the week following the diagnosis of office hypertension in primary care to avoid the effects of white‐coat hypertension. Finally, all of the patients with ABPM‐confirmed hypertension underwent home polygraphy in the week after ABPM was performed.

Procedures

Blood Samples

Venous blood samples were obtained between 8 am and 10 am from all of the participants for the measurement of biological parameters, including their glycemic, creatinine, electrolytes, cholesterol, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides levels.

ABPM

The 24‐hour ABPM was performed using a Spacelabs ABPM monitor 90207 (Spacelabs Healthcare, Redmond, WA). The diagnosis of systemic hypertension using 24‐hour ABPM was made according to standard criteria.24 During ABPM, BP measurements were obtained every 20 minutes during the day and every 30 minutes during the night. ABPM recordings were considered optimal when the percentage of the measurements was >70%, with at least one measurement every hour. The times that the patients awakened and went to bed were considered to define the daytime and nighttime measurement periods. All of the patients were questioned about their sleep duration and quality. Hypertension was defined as a systolic BP ≥135 mm Hg, a diastolic BP ≥85 mm Hg, or both during the daytime, and a systolic BP ≥120 mm Hg, a diastolic BP ≥70 mm Hg, or both during the hours of sleep. The patients’ circadian patterns were classified according to standard criteria based on dipping ratio (nighttime/daytime BP ratio).24 Table 1 provides a list of the ABPM variables that were assessed.

Table 1.

Ambulatory BP Monitoring Variables

| Primary variables |

| Systolic, diastolic, mean, and pulse BP |

| Maximum and minimum systolic and diastolic daytime and nighttime BP |

| Daytime, nighttime, mean, systolic, diastolic, and pulse BP |

| Mean nighttime and daytime heart rate |

| Derived variables |

| Area under the curve for nighttime and daytime BP |

| Area under the curve for nighttime and daytime SBP, DBP, MBP, and pulse BP |

| Tertile classification of the area under the curve for the diverse nighttime BP |

| Tertile classification of the area under the curve for nighttime heart rate |

| Circadian variables |

| Dipping ratio (nighttime/daytime BP ratio) |

| Circadian pattern classification based on the DR: nondippers (0.9 < ratio ≤ 1), dippers (0.8 < ratio ≤ 0.9), extreme dippers (ratio<0.8), and risers (ratio>1.0) |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DR, dipping ratio (nighttime/daytime BP ratio); MBP, mean blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Sleep Studies

Home polygraphy25 (validated BREAS SC20 polygraphy device; Breas Medical AB, Mölnlyke, Sweden) was performed, which included continuous recording of nasal flow, pulse oximetry, and thoracic and abdominal respiratory movements. Apnea was defined as a cessation of nasal flow that lasted >10 seconds, and hypopnea as a 50% decrease in nasal flow that lasted 10 seconds or longer with a >4% decrease in oxygen saturation. In this sleep study, the apnea‐hypopnea index was calculated as the average number of apnea episodes plus the hypopnea episodes per hour of sleep.

Statistical Analysis

The numerical variables were summarized as mean±standard deviation. The nominal variables were described as the absolute and relative frequencies. A multivariate logistic regression model was constructed to identify the qualitative and quantitative variables that were associated with an AHI ≥15. We used the likelihood ratio test to determine which explanatory variables should be included in the analysis. The variables that were significantly associated with OSA were used to construct best‐fit models, and area under the curve (AUC) values were obtained. The ability of the ABPM variables to identify moderate to severe OSA was evaluated alone and in combination with the other variables. We performed an analysis using only the clinical (sociodemographic and anthropometric) and biological parameters, an analysis using only the ABPM variables and an analysis using all of the variables (clinical, biological, and ABPM). The Hosmer‐Lemeshow test and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve were used to assess the model's calibration and discrimination. The net reclassification index (NRI) and the integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) were also measured.

Based on the final optimized logistic regression model that identified the patients with an AHI ≥15, a scoring system was constructed. This system enables the clinical application of the logistic model using a simple sum of the values. The construction is based on the model's coefficients; therefore, the order that is established by the sum of scores corresponds exactly with the order of the probabilities that are estimated by the logistic regression model. Subsequently, we approximated the score values to the nearest integer value, thereby maintaining the order of the estimated probabilities without diminishing the AUC in the rounded scoring system.

The comparability between the validation and the study sample was assessed by a t test and a chi‐square test to compare the quantitative and qualitative patient characteristics, respectively. The calibration and discriminative value of the proposed scoring system were recalculated.

The R program, version 2.15.2, was used for the description and analysis of the data, with a statistical significance level of .05.

Results

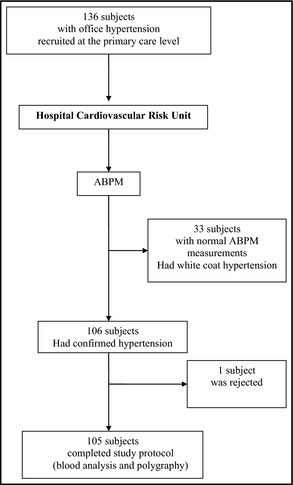

A total of 139 hypertensive snorers were recruited at primary care centers. After ABPM measurements were obtained, 33 patients were excluded from the study because they presented white‐coat hypertension. Of the remaining 106 patients, one patient was unable to continue the study protocol and was rejected. Finally, a total of 105 patients were included in the study (Figure 1). The results that were obtained from this first group of patients were validated in 21 patients who were specifically recruited for this purpose.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study.

The patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 2. The patients were predominantly middle‐aged men who were either overweight (BMI 25–29.9 in 40.95% of the patients) or obese (BMI ≥30 in 53.33% of the patients). According to Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) criteria,22 63.7% of the patients presented with abdominal obesity, and metabolic syndrome was diagnosed in 46.6% of the patients. Based on the criteria from a consensus of different scientific societies,26 metabolic syndrome was diagnosed in 57.14% of the patients. According to office BP levels, 85.71% of the patients had mild to moderate hypertension based on the European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology classification.24

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics in the Study and Validation Groups

| Characteristics | Study Group (n=105) | Validation Group (n=21) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean±SD, y | 49.8±10.13 | 49.14±6.15 | .691 |

| Male, No. (%) | 84 (80.0) | 16 (76.2) | .768 |

| BMI, mean±SD, kg/m2 | 31.16±4.5 | 30.57±4.7 | .608 |

| Abdominal fat,a No. (%) | 67 (63.7) | 16 (76.2) | .401 |

| Neck circumference >40 cm, No. (%) | 69 (65.7) | 12 (57.1) | .618 |

| ESS score, mean±SD | 8.56±4.36 | 9.33±4.96 | .513 |

| Smoking, No. (%) | 35 (33.3) | 5 (23.8) | .549 |

| Diabetes or impaired fasting glucose, No. (%) | 16 (15.2) | 2 (9.5) | .735 |

| Dyslipidemia,b No. (%) | 41 (39.0) | 8 (38.1) | 1 |

| COPD,c No. (%) | 2 (1.90) | 2 (9.52) | .129 |

| Ischemic heart disease, No. (%) | 1 (0.95) | 1 (4.76) | .307 |

| Stroke, No. (%) | 1 (0.95) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Heart failure,d No. (%) | 2 (1.90) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Clinical peripheral arteriopathy, No. (%) | 4 (3.81) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Office blood pressure | |||

| Grade I hypertension, No. (%) | 55 (52.4) | 9 (42.85) | .916 |

| Grade II hypertension, No. (%) | 35 (33.3) | 9 (42.85) | |

| Grade III hypertension, No. (%) | 15 (14.3) | 3 (14.3) | |

| ABPM circadian pattern | |||

| Dipper, No. (%) | 60 (57.1) | 11 (52.4) | .887 |

| Nondipper, No. (%) | 30 (28.6) | 7 (33.3) | |

| Extreme dipper, No. (%) | 13 (12.4) | 3 (14.3) | |

| Riser, No. (%) | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Cardiorespiratory polygraphy | |||

| AHI <5, No. (%) | 19 (18.1) | 8 (38.1) | .210 |

| AHI 5–14.9, No. (%) | 37 (35.2) | 4 (19.0) | |

| AHI 15–30, No. (%) | 20 (19.0) | 3 (14.3) | |

| AHI >30, No. (%) | 29 (27.6) | 6 (28.6) | |

Abbreviations: ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; AHI, apnea‐hypopnea index; BMI, body mass index; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale; SD, standard deviation. aAbdominal fat: abdominal circumference ≥102 cm in men and ≥88 cm in women. bDyslipidemia: hypercholesterolemia, mixed dyslipidemia, or hypertriglyceridemia pharmacologically treated or not. cChronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease degree I. dHeart failure: New York Heart Association class II.

Using the ABPM results, the analysis of the patients’ circadian patterns revealed that 69.5% of the patients were dippers. Most of them had a preserved circadian pattern; however, 86.6% had nocturnal hypertension.

According to the home polygraphy results, 46.6% of the patients had moderate to severe OSA (AHI ≥15).

Constructed Models

Using the study variables, three different stepwise models were constructed to identify OSA patients (AHI ≥15).

Model 1: Restricted to Clinical and Biological Variables

The model was developed using only the clinical and biological variables. The variables that were significantly associated with OSA were sex (male) and obesity, which was defined as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and abdominal obesity (abdominal circumference >88 cm in women and >102 cm in men). A multivariate logistic model was constructed to identify OSA patients using these variables. The resulting ROC of this first model had an AUC of 0.617 (Table IV).

Model 2: Restricted to 24‐Hour ABPM Variables

Using the same methodology as the first model, a second model was constructed to identify OSA patients using only the ABPM variables. This model included four determinant variables: (1) a mean daytime BP <109 mm Hg, (2) a minimal diastolic nighttime BP ≥63 mm Hg, (3) mean nocturnal heart rate, and (4) minimal/maximal nocturnal heart rate ratio >0.67. This model generated a ROC with an AUC of 0.736 (Table IV).

Model 3: Developed Using All of the Clinical, Biological, and ABPM Variables

When all of the clinical, biological, and ABPM variables were included in this model, the following five determining variables were identified: (1) male sex, (2) obesity (defined as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and abdominal obesity), (3) a mean daytime BP <109 mm Hg, (4) mean nocturnal heart rate, and (5) a minimal diastolic nighttime BP ≥63 mm Hg (Table 3). The combination of the ABPM, clinical, and biological variables achieved an ROC with an AUC of 0.804 (Figure 2). This model had adequate sensitivity and specificity for the identification of moderate to severe OSA (Table 4). According to the Hosmer‐Lemeshow test, a significant lack of calibration was not observed in the model (P=.57). The NRI and IDI showed a significant improvement with respect to the previous models.

Table 3.

Final Model Determinant Variables

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 8.02 | (2.16–35.90) | .003 |

| Mean daytime BP <109 mm Hg | 5.25 | (1.93–16.00) | .0019 |

| Obesity, general and abdominal | 4.90 | (1.89–13.82) | .0016 |

| Minimum diastolic nighttime BP ≥63 mm Hg | 3.42 | (1.33–9.53) | .013 |

| Mean nocturnal heart rate, ppm | 1.09 | (1.03–1.15) | .0029 |

Abbreviations, BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; ppm, pulsations per minute.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating curve of the model constructed to identify patients with an apnea‐hypopnea index ≥15 based on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, clinical, and biological variables.

Table 4.

Multivariate Logistic Models Constructed to Identify Patients With an Apnea‐Hypopnea Index ≥15

| Model and determinant variables | Area Under the Curve |

|---|---|

|

Model constructed with clinical (anthropometric and epidemiological) and biological variables Determinant variables |

0.617 |

| Sex | |

| Obesity | |

|

Body mass index ≥30 and abdominal obesity (abdominal circumference >88 cm in women and >102 cm in men) | |

|

Model restricted to ambulatory blood pressure monitoring variables Determinant variables |

0.736 |

| Mean daytime blood pressure <109 mm Hg | |

| Minimum diastolic nighttime blood pressure ≥63 mm Hg | |

| Mean nocturnal heart rate | |

| Minimal/maximal nocturnal heart rate ratio >0.67 | |

|

Model constructed with all of the variables Determinant variables |

0.804 |

| Sex | |

| Obesity | |

|

Body mass index ≥30 and abdominal obesity (abdominal circumference >88 cm in women and >102 cm in men) | |

| Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring variables | |

| Mean daytime blood pressure <109 mm Hg | |

| Minimum diastolic nighttime blood pressure ≥63 mm Hg | |

| Mean nocturnal heart rate |

Scoring System

Using the final model that was constructed with all of the variables, a scoring system was created to identify moderate to severe OSA (Table 5).

Table 5.

Scoring System for the Identification of Moderate to Severe OSA

| Condition | Score |

|---|---|

| Male | 25 |

| Mean daytime BP <109 mm Hg | 20 |

| Obesity | 19 |

| Minimum diastolic nighttime BP ≥63 mm Hg | 15 |

| Nocturnal heart rate, ppm |

Abbreviations: OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; ppm, pulsations per minute. Obesity was defined by the concurrence of a body mass index ≥30 and an abdominal circumference >102 cm in men and an abdominal circumference >102 cm in men and >88 cm in women.

Scoring System: On the left of the table, we list each of the variables according to its weight in the model. On the right, we assign each of the variables a score that is equivalent to its weight in the model. When the patient's results are consistent with each of the four conditions listed on the left, we assign each variable the corresponding scores on the right. If the patient's results are not consistent, we assign 0 points for the corresponding condition. For the fifth condition, we assign the absolute value of the nighttime pulsations per minute during ambulatory blood pressure (BP) monitoring. Finally, we add all of the points to obtain a total score. A final score that is >113 points may be used to identify patients with an apnea‐hypopnea index ≥15, with a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 64%.

Validation Dataset

The scoring system was externally validated in 21 of the patients. The patients in the validation sample had similar clinical characteristics as the study group. These patients were predominantly middle‐aged men, many of whom were obese or overweight with increased abdominal fat (Table 2). According to the APT III criteria, 57.14% of the patients had MetS22 and according to the criteria from a consensus of different scientific societies, 71.42% of the patients.26 Regarding the office BP levels 85.7% of the patients had mild to moderate hypertension. During ABPM, the patients had predominately dipper circadian patterns (66.7%). According to the home polygraphy results, 42.9% had moderate to severe OSA.

For the identification of the patients with an AHI ≥15, the scoring system had an ROC AUC of 0.92 (95% CI, 0.81–1.0) with a cutoff point of 113, yielding a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 66.7%. According to the Hosmer‐Lemeshow test, the scoring system was not associated with a significant lack of calibration when applied to the validation sample (P=.76).

Subanalysis in the Subgroup of Men

To improve the lack of precision (indicated by wide intervals) in the odds ratios and the high percentage of men (80%), a subanalysis restricted to men was performed by analyzing a more homogeneous group. Although the results (not shown) were similar (AUC of 0.815), the precision was worse.

Discussion

Main Study Contribution

The main contribution of this study is that it used easily obtainable clinical and ABPM variables to identify the patients at risk for moderate to severe OSA. Based on these variables, we created a scoring system that may serve as a useful tool for early OSA identification. This scoring system consists of variables such as sex, BMI, and abdominal circumference and the variables of ABPM, which is widely used in hypertension management. The system is feasible for physicians in most care areas.

Of the three models that were evaluated, model 3 was associated with the highest sensitivity and specificity for the identification of moderate to severe OSA. In this model, five variables were the most predictive of OSA, including two clinical variables (male sex and BMI), which are present in many other models,27, 28, 29, 30, 31 and the three ABPM variables (mean nocturnal heart rate, minimum diastolic nighttime BP, and mean daytime BP). The explanation for the predictive value of the two nighttime variables for OSA may be that increases in BP and heart rate occur during apnea episodes. Moreover, the lower mean daytime BP was related to a higher probability of OSA. To understand this result, two aspects must be considered. First, hypertension's circadian pattern is the result of the influence of a broad spectrum of neurohormonal mechanisms and not only a result of the influence of OSA. Second, the lower the daytime BP, the greater the probability that the nighttime BP variables are determinants of the final hypertension diagnostics using ABPM. These nighttime ABPM variables may be more influenced by OSA than daytime variables. To the best of our knowledge, no other models to date have included ABPM variables in OSA identification.

Relationship of the Findings to Other Relevant Studies

Previous studies have developed models to identify patients with a significant risk of sleep apnea. These models were constructed in special care areas, such as sleep apnea units28, 29, 30, 32 and anesthesiology departments,31, 33 with no comparable populations and with different objectives, such as to prioritize patients who are submitted to sleep studies or to identify a disease that is associated with a well‐established perioperative risk.34 Because of differences in the study populations, the results and contributions of these models are not applicable to our hypertensive primary care population. Considering these differences, the best ROC AUC value from these studies was 0.809.30

We found three studies of primary care and general populations that developed models for identifying patients who should be submitted to sleep units.35, 36, 37 The results and contributions are not comparable with those of our study because they included both hypertensive and nonhypertensive patients. However, in a manner analogous to our model, two of these studies36, 37 included abdominal circumference as a determinant variable in addition to previously established variables, such as sex and BMI.35, 36 Of these studies, Chai‐Coetzer and colleagues,37 by including variables such as abdominal circumference and age and two questions from the Berlin questionnaire, obtained a model to identify severe OSA (AHI >30) that was based on home polysomnography findings and that had an ROC AUC of 0.84. This model and the model presented in this study are both simple and feasible; however, our model has two additional advantages. Because it is based on objective ABPM variables, it is not susceptible to individual subjectivity, such as in qualitative questionnaires. In addition, introducing the scoring system that was derived from this model into the software analysis of the ABPM monitor, the diagnostic performance of ABPM may be improved. Therefore, an OSA screening could be performed without a medical interview.

To the best of our knowledge, few studies have proposed predictors or screening models that were restricted to hypertensive individuals.38, 39, 40 Only one of these studies was performed in a primary care setting.39 Gurubhangavatula and colleagues40 proposed various models for screening severe sleep apnea (AHI >30). Of these validated models, the ones that performed best achieved ROC AUC values that ranged from 0.718 to 0.816; however, to be applied, home polygraphy must be performed in some cases. The accessibility of this tool in primary care or hypertension units may restrict the clinical application for screening OSA.

The better performance of the model we developed compared with previous models may be the result of two factors. First, hypertension and snoring had important implications as inclusion criteria in this study. In the only primary care study restricted to hypertensive patients, Borström and colleagues39 found that snoring was an important predictor of OSA. Second, the inclusion of ABPM variables significantly improved the model.

Study Strengths and Limitations

The major strength of this study is that the simple model and scoring system can be applied in primary care centers to identify patients with moderate to severe OSA. In addition, hypertensive patients are the most likely candidates for continuous positive airway pressure treatment, which yields additional health benefits. Although the model application does not obviate performing a sleep study, the model may improve the selection of patients who should be submitted to a sleep unit for priority evaluations. Moreover, it might be expected to impact the role of ABPM in the management of individuals with hypertension related to the indications and time of application. Nevertheless, this study has its limitations. The sleep study used was a home polygraphy and not polysomnography, which is considered the gold standard for diagnosing sleep apnea. However, home polygraphy studies can accurately identify patients with moderate to severe OSA.41 Other limitations are related to the inclusion criteria and the need for an ABPM monitor. The imposition of snoring as an inclusion criterion limits the population suitable for model application. However, hypertension status and snoring are highly prevalent in the general population. In addition, in primary care, snoring is reported to be highly prevalent in hypertensive individuals.4, 39 Despite the fact that ABPM is not available in the primary care centers of some countries, the broad indications of this tool in the management of hypertension and its accepted cost/effectiveness may lead to its generalized use in the future. Although acceptable for clinical use, stronger specificity of the final model is preferable. The specificity might improve with a larger sample size or by including other variables with predictive value to identify snorers without OSA. Nevertheless, to date, there is no method to screen for OSA based on ABPM. Finally, the slow recruiting rate of the patients limited the sample size for the validation. However, when the scoring system was applied to the validation sample, it demonstrated good calibration and discrimination (AUC, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.81–1.00).

Conclusions

In newly diagnosed hypertensive snorers, the inclusion of ABPM variables improves the identification of OSA in patients with an AHI ≥15 rather than using clinical and biological parameters alone. In the absence of models that provide better specificity, using ABPM, clinical, and biological variables allows the creation of an optimal screening model for the identification of moderate to severe OSA. A simple and useful scoring system derived from this model allows the transfer of these findings to clinical practice in primary care centers and hypertension units.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by the Societat Catalana d′Hipertensió Arterial, Barcelona (Spain).

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Societat Catalana d′Hipertensió Arterial (SCHTA), Barcelona (Spain). The authors would like to thank the clinicians of the Sleep and Cardiovascular Risk Units of Santa Maria Hospital and the primary care clinics, Joan Barges, Francesc Armengol, and Marta Ortega, and the physicians of the hospital's cardiovascular risk units, Pedro Armario and Carmen Suarez.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2015:802–809. DOI: 10.1111/jch.12619. © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

References

- 1. Durán J, Esnaola S, Rubio R, Iztueta A. Obstructive sleep apnea‐hypopnea and related clinical features in a population based sample of subjects aged 30–70 yr. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(3 Pt 1):685–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peppard PE, Young TY, Barnet JH, et al. Increased prevalence of sleep‐disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Silverberg DS, Oksenberg A. Are sleep‐related breathing disorders important contribuiting factors to the production of essential hypertension? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2001;3:209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Durán‐Cantolla J, Aizpuru F, Montserrat JM, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure as treatment for systemic hypertension in people with obstructive sleep apnoea: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c5991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sánchez‐de‐la‐Torre M, Campos‐Rodriguez F, Barbé F. Obstructive sleep apnoea and cardiovascular disease. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1378–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nieto FK, Young TB, Lind BK, et al. Association of sleep‐disordered breathing, sleep apnea and hypertension in a large community based study. JAMA. 2000;283:1829–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, et al. Association of hypertension and sleep‐disordered breathing. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2289–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haas DC, Foster GL, Nieto J, et al. Age‐dependent associations between sleep‐disordered breathing and hypertension. Circulation. 2005;111:614–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Noda A, Okada T, Ysuma F, et al. Cardiac hypertrophy in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1995;107:1538–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hedner J, Ejnell H, Caidahl K. Left ventricular hypertrophy independent of hypertension in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Hypertens. 1990;8:941–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peker Y, Carlson J, Hedner J. Increased incidence of coronary artery disease in sleep apnoea: a long term follow‐up. Eur Respir J 2006;28:596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gottlieb DJ, Yenokyan G, Newman AB, et al. Prospective study of obstructive sleep apnea and incident coronary heart disease and heart failure (The Sleep Heart Health Study). Circulation 2010;122:352–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alchanatis M, Tourkohoriti G, Kosmas EN, et al. Evidence for left ventricular dysfunction in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:1239–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laaban JP, Pascal Sebaoun S, Bloch E, et al. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest 2002;122:1133–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mehra R, Benjamin EJ, Sharar E, et al. Association of nocturnal arrhythmias with sleep‐disordered breathing: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:910–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mehra R, Stone KL, Varosky PD, et al. Nocturnal arrhythmias across a spectrum of obstructive and central sleep‐disordered breathing in older men. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1147–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Suzuki T, Nakano H, Maekawa J, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and carotid‐artery intima‐media thickness. Sleep. 2004;27:129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Drager LF, Bortolotto LA, Kiegger EM, Lorenzi‐Filho G. Additive effects of obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension on early markers of carotid atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2009;53:69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2034–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Artz M, Young T, Finn L, et al. Association of sleep disordered breathing and occurrence of stroke. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1147–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome. An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chiner E, Arriero JM, Signes‐Costa J, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale in patients with a sleep apnea syndrome. Arch Bronconeumol. 1999;35:422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mancía G, De Backer G, Dominiczack A, et al. ESH‐ESC Task Force on management of arterial hypertension. 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens 2007;25:1751–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nuñez R, Rey de Castro J, Socarrás E, et al. Validation study of a polygraphic screening device (BREAS SC20) in the diagnosis of sleep apnea‐hypopnea syndrome. Arch Bronconeumol 2003;39:537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Viner S, Szalai JP, Hoffstein V. Are history and physical examination a good screening test for sleep apnea? Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:356–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bouloukaki I, Kapsimalis F, Mermigkis C, et al. Prediction of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in large Greek population. Sleep Breath. 2011;15:657–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rowley JA, Aboussouan LS, Badr MS. The use of clinical prediction formulas in evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2000;23:929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rodsutti J, Hensley M, Thakkinstian A, et al. A clinical decision rule to prioritize polisomnography in patients with suspected sleep apnea. Sleep 2004;27:694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire. A tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:812–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Crocker B, Olson LG, Saunders NA, et al. Estimation of the probability of disturbed breathing during sleep before a sleep study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1990;142:14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. Validation of the Berlin questionnaire and American Society of Anesthesiologist checklist as screening tools for obstructive sleep apnea in surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:822–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vasu TS, Grewal R, Doghramji K. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and perioperative complications: a systematic review of the literature. J Clin Sleep Med 2012;8:199–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Young T, Sharar E, Nieto J, et al. Predictors of sleep‐disordered breathing in community‐dwelling adults (The Sleep Heart Health Study). Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Caffo B, Diener‐West M, Punjabi N, Samet J. A novel approach to prediction of mild obstructive sleep disordered breathing in a populations‐based sample: the sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2010;33:1641–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chai‐Coetzer CL, Antic NA, Rowland LS, et al. A simplified model of screening questionnaire and home monitoring for obstructive sleep apnoea in primary care. Thorax. 2011;66:213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Drager LF, Genta PR, Pedrosa RP, et al. Characteristics and predictors of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:1135–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Borström A, Sunnegren O, Arestedt K, et al. Factors associated with undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnoea in hypertensive primary care patients. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2012;30:107–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gurubhangavatula I, Fields BG, Morales CR, et al. Screening for severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in hypertensive outpatients. J Clin Hypentens (Greenwich). 2013;15:279–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Masa JF, Corral J, de Sanchez Cos J, et al. Effectiveness of three sleep apnea management alternatives. Sleep. 2013;36:1799–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]