Abstract

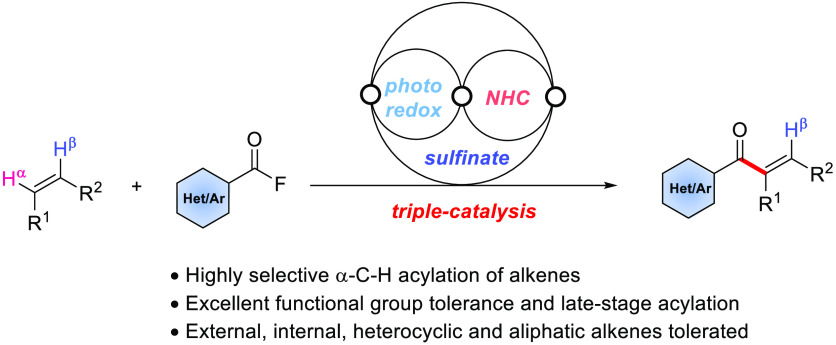

N-Heterocyclic carbene (NHC) catalysis has emerged as a versatile tool in modern synthetic chemistry. Further increasing the complexity, several processes have been introduced that proceed via dual catalysis, where the NHC organocatalyst operates in concert with a second catalytic moiety, significantly enlarging the reaction scope. In biological transformations, multiple catalysis is generally used to access complex natural products. Guided by that strategy, triple catalysis has been studied recently, where three different catalytic modes are merged in a single process. In this Communication, direct α-C–H acylation of various alkenes with aroyl fluorides using NHC, sulfinate, and photoredox cooperative triple catalysis is reported. The method allows the preparation of α-substituted vinyl ketones in moderate to high yields with excellent functional group tolerance. Mechanistic studies reveal that these cascades proceed through a sequential radical addition/coupling/elimination process. In contrast to known triple catalysis processes that operate via two sets of interwoven catalysis cycles, in the introduced process, all three cycles are interwoven.

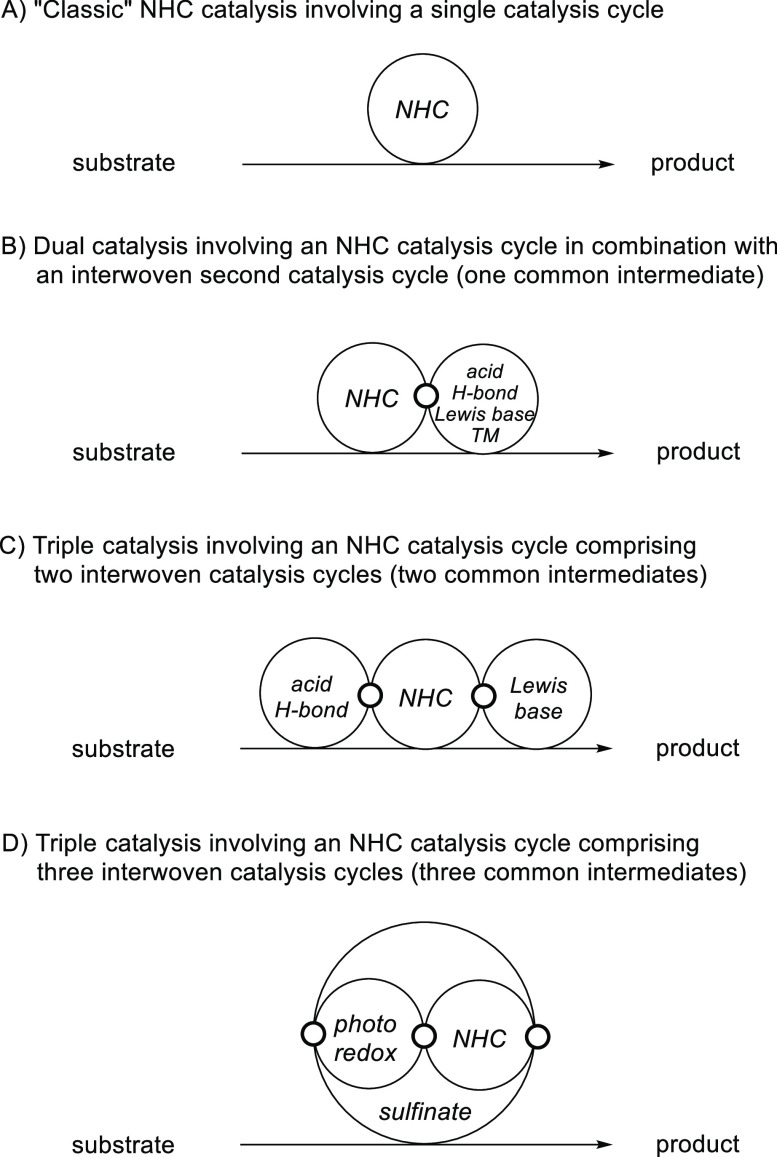

N-Heterocyclic carbene (NHC) catalysis has drawn considerable attention over the past decades.1−8 For example, umpolung of aldehydes via NHC catalysis to provide acyl anion equivalents has led to the development of important transformations,9−16 including the benzoin condensation17,18 and the Stetter reaction.19−22 Most of these reactions proceed via a single catalysis cycle (Figure 1A), and there are limitations associated with the use of single NHC catalysis.23−25 In recent years, NHC catalysis has witnessed an expansion by a move toward dual catalysis in which NHC catalysis is merged with acid catalysis,26−33 hydrogen-bond catalysis,34,35 transition-metal catalysis,36−43 or others44−49 (Figure 1B). In these processes, the NHC catalysis cycle is interwoven with a second catalysis cycle, where the two cycles have a common intermediate. The construction of complex natural products in biological systems generally proceeds via a multiple catalysis approach, and by following nature’s strategies, multiple catalysis on the basis of combining three or more distinct catalysts has emerged as an appealing opportunity for the development of novel reactions.50,51 However, triple catalysis involving an NHC catalysis cycle is still in its infancy. The challenges lie in the many compatibility issues between catalysts and intermediates if two additional catalysis cycles have to be considered along with the NHC cycle. The few examples reported operate via two sets of interwoven catalysis cycles with the first and second cycles coupled and the second and third cycles coupled.52−54 However, the first and third cycles are not interwoven in these systems, and overall, two common intermediates are observed (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

General representation of NHC-catalyzed transformations proceeding via single, double, and triple catalysis.

Herein we present an unprecedented mode of NHC triple catalysis in which NHC catalysis is merged with cooperative sulfinate and photoredox catalysis. In contrast to known triple catalysis processes that operate via two sets of interwoven catalysis cycles, all three cycles are interwoven, resulting in three common intermediates (Figure 1D).

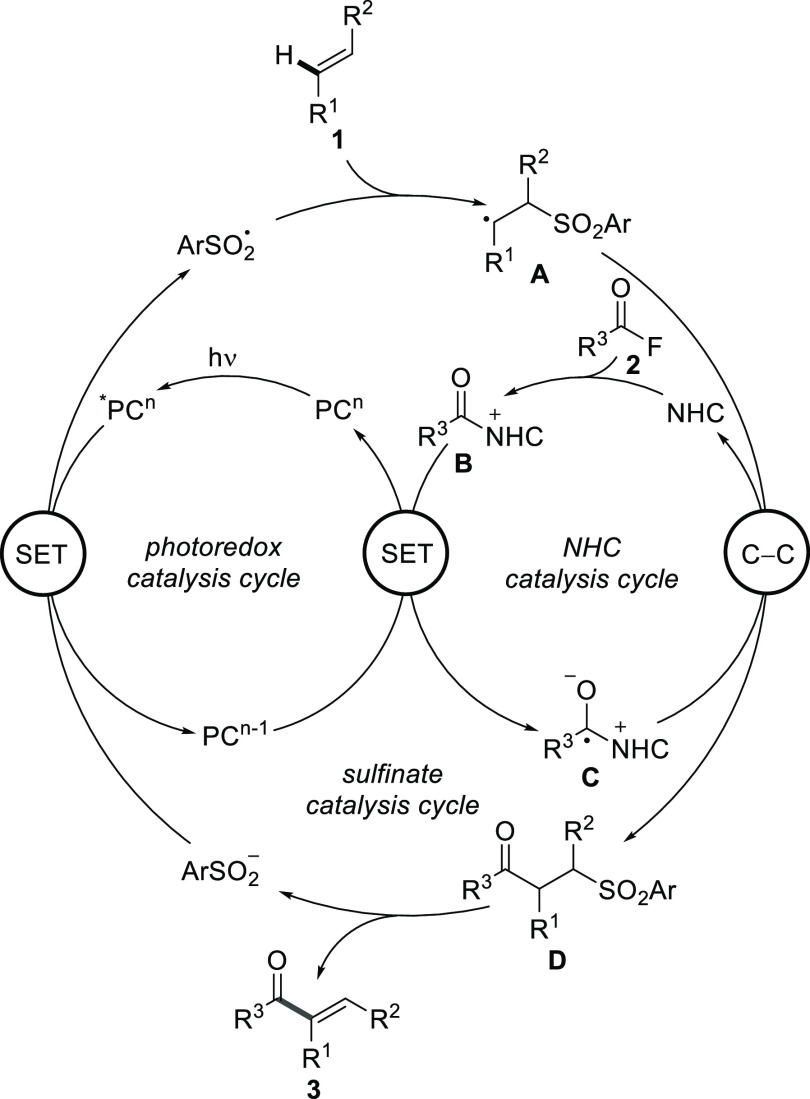

The conceptual novel triple catalysis could be realized in a direct α-C–H acylation of various alkenes with aroyl fluorides. The reaction design and mechanistic rationality are depicted in Scheme 1. The sulfinate catalysis cycle starts with single electron transfer (SET) oxidation of an aryl sulfinate by an excited photoredox catalyst *PCn to give an aryl sulfonyl radical along with a PCn–1 complex.55−60 Radical addition of the sulfonyl radical to substrate alkene 1 leads to adduct radical A. On the other hand, the reaction between aroyl fluoride 2 and the NHC catalyst gives acyl azolium ion B, which undergoes SET reduction with the reduced photoredox catalyst (PCn–1 complex) to generate ketyl-type radical C and the starting PCn complex, thereby closing the photoredox cycle.61−63 Radical/radical cross-coupling between C and C radical A followed by NHC fragmentation leads to intermediate D, closing the NHC catalysis cycle. Such radical/radical cross-couplings are steered by the persistent radical effect64,65 and have recently been successfully used by Ohmiya,66−68 Scheidt,69 other groups,70−75 and us63 in NHC-catalyzed radical processes. Base-mediated elimination of the aryl sulfinate eventually delivers α-acylated alkene 3, closing the sulfinate catalysis cycle.76 Notably, acylation of substituted alkenes with acyl electrophiles usually affords the corresponding β-acylation products.77−81

Scheme 1. Reaction Design and Proposed Mechanism.

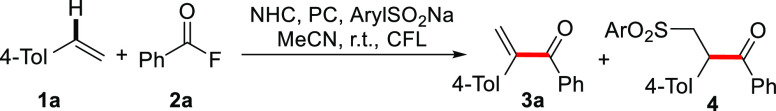

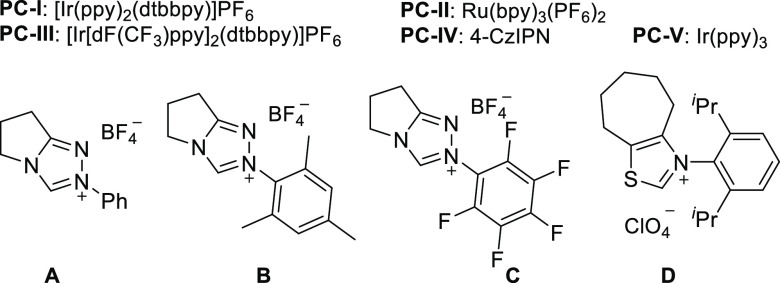

On the basis of our design, we began the investigations with 4-methylstyrene (1a) and benzoyl fluoride (2a) as the model substrates. PhSO2Na was chosen as the sulfinate catalyst (25 mol %) in combination with [Ir(ppy)2(dtbbpy)]PF6 (1.5 mol %) as the photoredox catalyst. Triazolium salt A was selected as the NHC precatalyst (15 mol %) for initial base screening. Experiments were conducted in acetonitrile at room temperature under irradiation with a compact fluorescent lamp (CFL). Disappointingly, with Cs2CO3, KOtBu, or DBU (2 equiv), the target 3a was not formed (Table 1, entries 1–3). A small amount of side product 4, corresponding to intermediate D (see Scheme 1), was identified in the presence of Cs2CO3. It is obvious that the base plays a crucial role.

Table 1. Reaction Optimizationa.

| entry | PC | NHCb | sulfinate | base (equiv) | yield of 3a (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PC-I | A | PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (2) | n.d. |

| 2 | PC-I | A | PhSO2Na | KOtBu (2) | n.d. |

| 3 | PC-I | A | PhSO2Na | DBU (2) | n.d. |

| 4 | PC-I | A | PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (1) + KOtBu (1) | trace |

| 5 | PC-I | A | PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (1) + DBU (1) | 8 |

| 6 | PC-I | A | PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (0.5) + MTBD (1.3) | 26 |

| 7 | PC-I | B | PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (0.5) + MTBD (1.3) | 39 |

| 8 | PC-I | C | PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (0.5) + MTBD (1.3) | 17 |

| 9 | PC-I | D | PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (0.5) + MTBD (1.3) | 22 |

| 10 | PC-II | B | PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (0.5) + MTBD (1.3) | 43 |

| 11 | PC-III | B | PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (0.5) + MTBD (1.3) | 28 |

| 12 | PC-IV | B | PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (0.5) + MTBD (1.3) | 35 |

| 13 | PC-V | B | PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (0.5) + MTBD (1.3) | n.d. |

| 14 | PC-II | B | 4-OMe-PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (0.5) + MTBD (1.3) | 10 |

| 15 | PC-II | B | 4-Cl-PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (0.5) + MTBD (1.3) | 56 |

| 16 | PC-II | B | 4-CN-PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (0.5) + MTBD (1.3) | 48 |

| 17 | PC-II | B | MeSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (0.5) + MTBD (1.3) | 4 |

| 18 | PC-II | B | 4-Cl-PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (0.5) + MTBD (1.3) | 81 (78)d |

| 19 | PC-II | B | 4-Cl-PhSO2Na | Cs2CO3 (0.5) + MTBD (1.3) | n.d.e |

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.15 mmol), 2a (0.3 mmol), NHC (15 mol %), photoredox catalyst (1.5 mol %), PhSO2Na (25 mol %), base (2.0 equiv), and MeCN (1.5 mL) under irradiation with a 23 W CFL for 24 h.

GC yields using biphenyl as an internal standard. The yield of the isolated product is given in parentheses.

20 mol % NHC, 30 mol % 4-Cl-PhSO2Na, and 2.5 equiv of 2a were applied.

Without photoredox catalyst, NHC, sulfinate, or irradiation.

We next explored mixed-base systems by combining Cs2CO3 with KOtBu or DBU, where the second base was expected to facilitate the elimination of the aryl sulfinate (Table 1, entries 4 and 5). Gratifyingly, the Cs2CO3/DBU couple provided ketone 3a in an encouraging 8% yield, whereas the Cs2CO3/KOtBu mixture was not efficient. The base system containing 0.5 equiv of Cs2CO3 and 1.3 equiv of 7-methyl-1,5,7-triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene (MTBD) led to an improved yield (26%; Table 1, entry 6). Without base, this cascade did not proceed (not shown). Optimization was continued by screening of different NHCs. The steric and electronic nature of the NHCs showed a measurable effect, and the use of B as the precatalyst provided an improved 39% yield, whereas the NHCs derived from C and D led to lower yields (Table 1, entries 7–9). Next, different photocatalysts were investigated, and Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 afforded an improved yield (Table 1, entry 10). [Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)]PF6 gave a worse result, and no product was identified with Ir(ppy)3 (Table 1, entries 11 and 13). Replacing the Ru photocatalyst with 4-CzIPN led to a slightly lower yield (Table 1, entry 12). Knowing that electron-poor aryl sulfinates show better leaving group ability in elimination reactions, we also varied the sulfinate. p-Methoxyphenyl sulfinate showed decreased efficiency compared with PhSO2Na (Table 1, entry 14). Pleasingly, a 56% yield of the target 3a was obtained with p-chlorophenyl sulfinate (Table 1, entry 15). The more electron-deficient p-cyanophenyl sulfinate gave a minor improvement (Table 1, entry 16). Of note, an aliphatic sulfinate was not an efficient cocatalyst (Table 1, entry 17). Some styrene remained unreacted in the best run (Table 1, entry 15), and we therefore increased the amount of NHC, sulfinate, and benzoyl fluoride. A significant improvement was achieved with 2.5 equiv of 2a, 20 mol % NHC, and 30 mol % sulfinate, which provided 3a in 78% yield (Table 1, entry 18). Control experiments revealed that the photoredox catalyst, NHC, sulfinate, and irradiation are all indispensable (Table 1, entry 19).

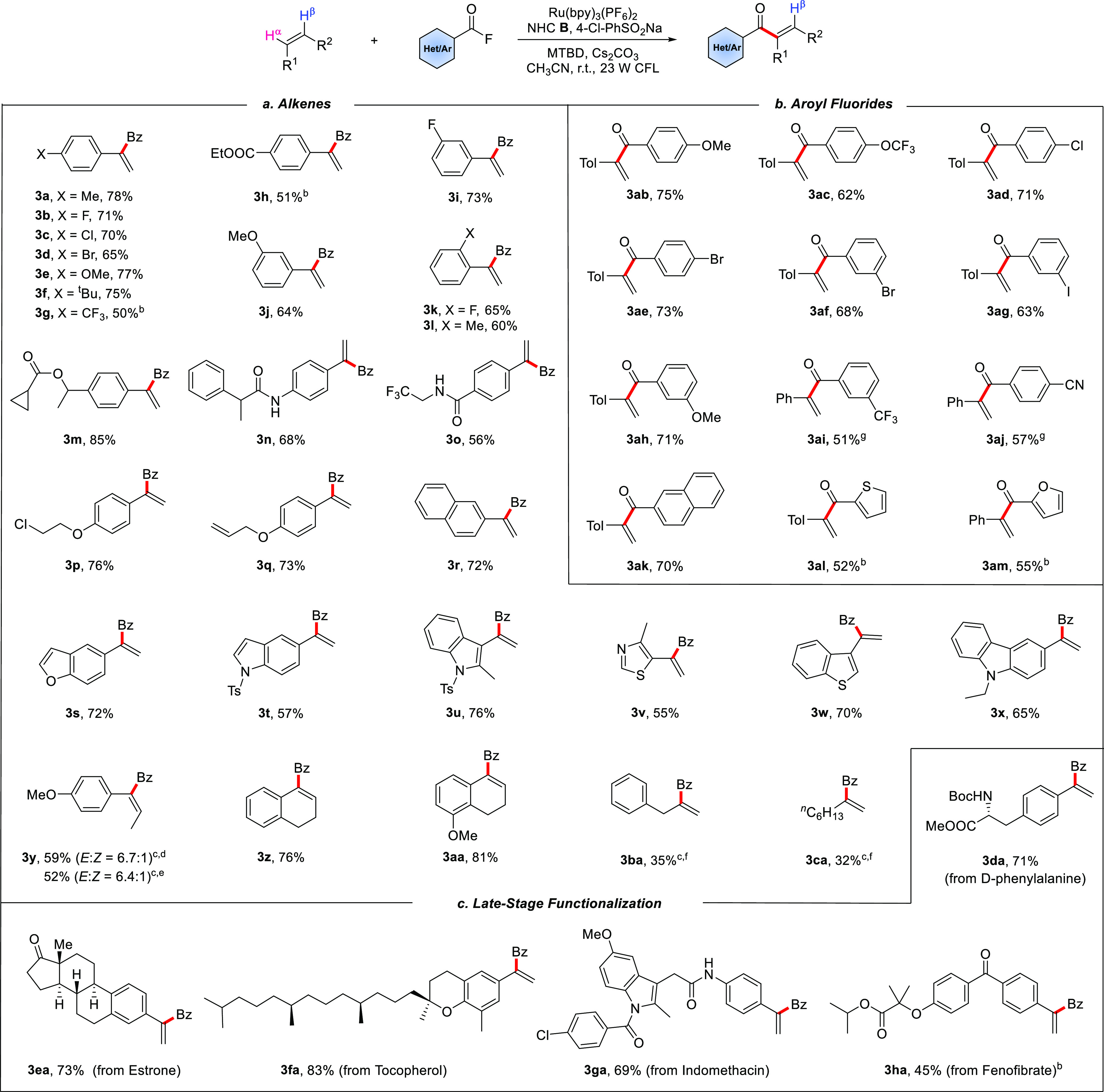

Under the optimized conditions, we explored the generality of the protocol by first varying the alkene component while keeping fluoride 2a as the acylation reagent (Scheme 2). The effect of substituents on the benzene ring in various styrenes was investigated. Acceptors bearing a halogen atom or electron-donating groups at the para position reacted smoothly to afford the products 3a–f in good yields (65–78%). Lower reaction efficiency was noted for the p-CF3- and p-EtO2C-substituted congeners (3g and 3h), where a significant amount of the alkene remained unreacted. The radical α-acylation also worked with ortho- and meta-substituted styrenes, and 3i–l were isolated in 60–73% yield. Ester and amide functionalities were tolerated, as documented by the preparation of 3m (85%) and 3n (68%). The fluoroalkylamine entity and a base-sensitive primary alkyl chloride were tolerated (3o and 3p). For substrates containing both an aryl alkene and a terminal aliphatic alkene moiety, the reaction occurred at the activated aryl alkene position (3q). Alkenes substituted with biologically important heteroarenes such as thiazole, benzothiophene, benzofuran, indole, and carbazole engaged in the α-benzoylation, and ketones 3r–x were obtained in 55–76% yield. Along with terminal alkenes, internal alkenes like 1,2-dihydronaphthalenes were α-acylated with complete regioselectivity (3z–aa, 76–81%). For the noncyclic system 3y, good E/Z selectivity (6.7:1) was obtained from trans-anethole when p-cyanophenyl sulfinate was used as the cocatalyst. A similar result was obtained with cis-anethole. With regard to aliphatic alkenes, only a trace amount of product was detected when the standard conditions were applied. We assumed that a more electron-deficient sulfinate catalyst might facilitate the radical addition and elimination steps. Indeed, when p-cyanophenyl sulfinate was used instead of p-chlorophenyl sulfinate, allylbenzene and 1-octene reacted to give the α-alkylated vinyl ketones (3ba and 3ca), albeit in lower yields. Next, the aroyl fluoride component was varied using 4-methylstyrene as the coupling partner. Electron-rich (3ab and 3ah) and electron-poor (3ac, 3ai, and 3aj) aroyl fluorides reacted well, and the product ketones were obtained in 51–75% yield. Halogen substituents were tolerated (3ad–ag), and aroyl fluorides bearing an extended π system or heteroarenes like thiophene and furan reacted to afford ketones 3ak–am in 52–70% yield. Of note, no product was identified with benzoyl chloride or benzoyl bromide instead of benzoyl fluoride. The potential of the process was further documented by late-stage functionalization of more complex activated alkenes. For example, alkenes derived from d-phenylalanine, hormone, natural product, and marketed drugs bearing an indole ring or functional groups such as ketone, amide, halide, and ester could all be aroylated at the α-position (3da–ha). Thus, our process offers a good platform to access more complex α-substituted vinyl ketones.

Scheme 2. Substrate Scope for the α-Acylation of Various Substituted Alkenes.

Reactions were conducted on a 0.15 mmol scale. Yields are of the isolated materials after purification, Bz = benzoyl.

4-CF3-PhSO2Na.

4-CN-PhSO2Na.

trans-Anethole.

cis-Anethole.

Half of 2a and MTBD were added at the beginning, and the rest was added after 12 h.

Cs2CO3 (0.8 equiv).

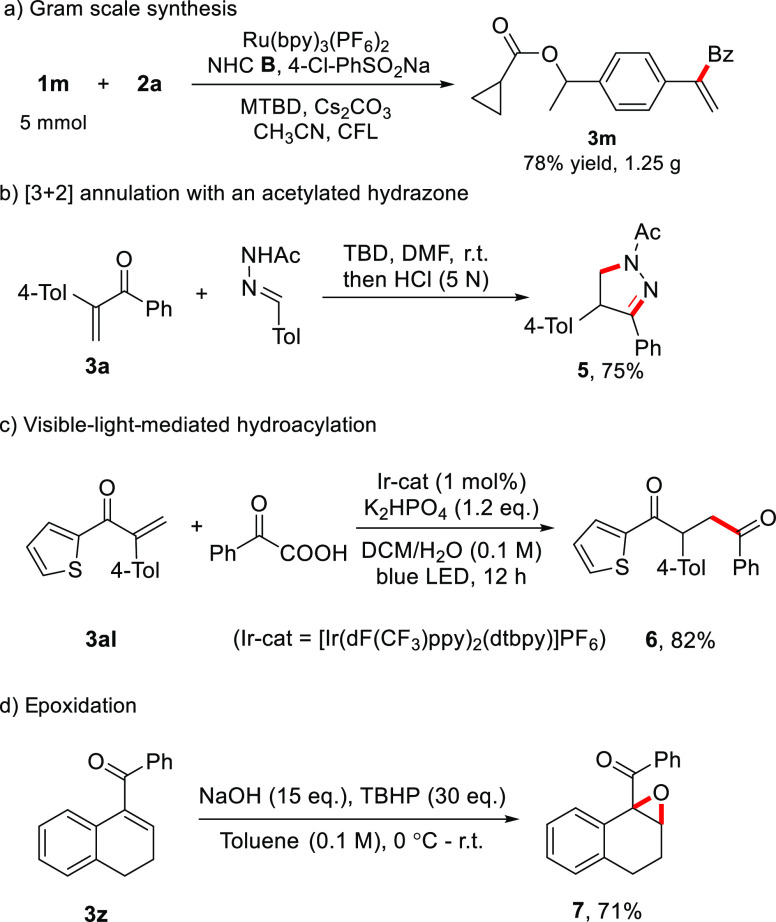

To illustrate the synthetic value of these α-substituted vinyl ketones, a gram-scale reaction of 1m was conducted with reduced amounts of the catalysts, and a comparable yield was obtained (Scheme 3a). Furthermore, [3 + 2] annulation82 of vinyl ketone 3a with an N-acylhydrazone provided dihydro-1H-pyrazole 5 in 75% yield (Scheme 3b). Photoredox-catalyzed hydroacylation of 3al with α-oxocarboxylic acid gave 1,4-diketone 6 (Scheme 3c),83 and epoxidation of enone 3z afforded oxirane 7 in 71% yield (Scheme 3d).

Scheme 3. Product Transformations.

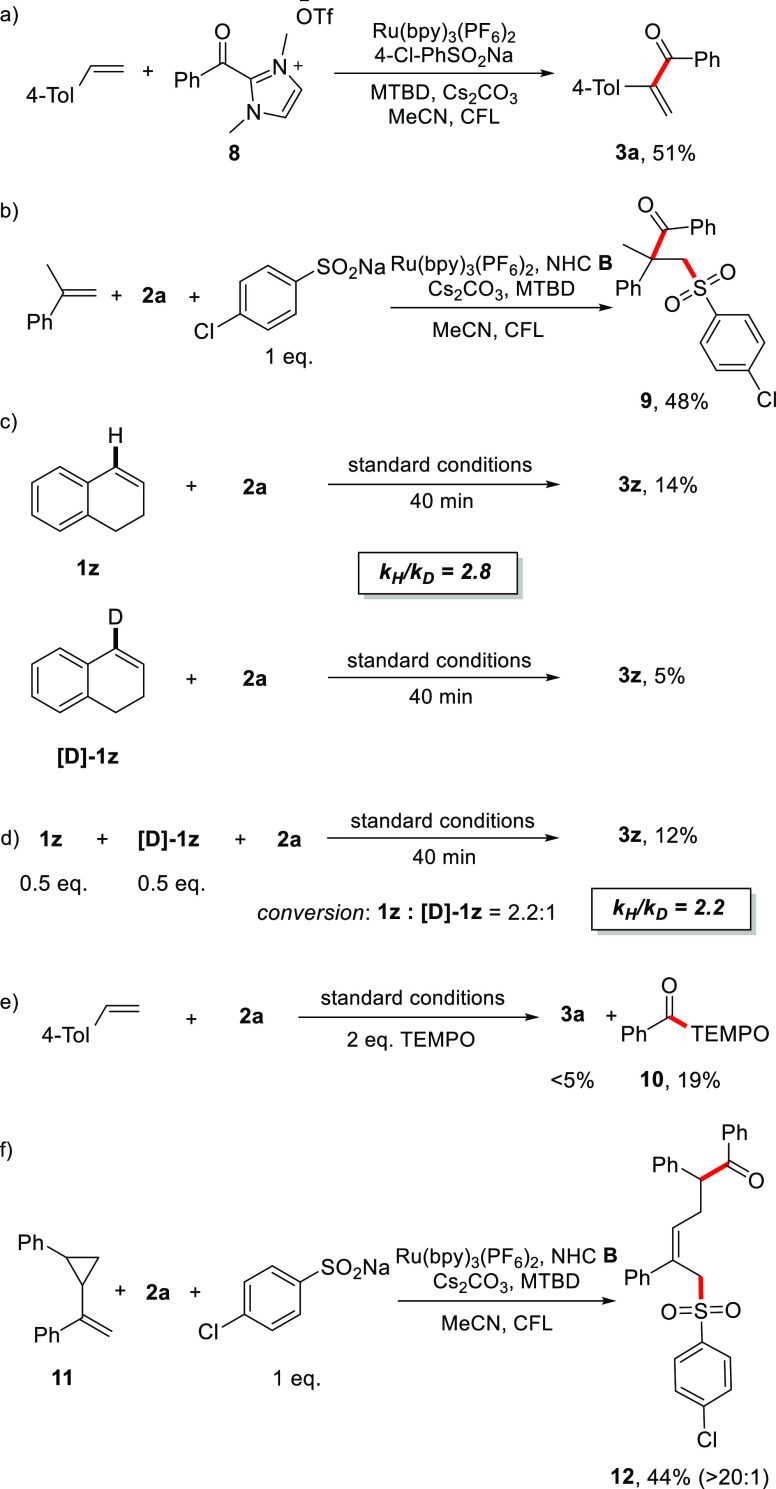

To support the mechanism suggested in Scheme 1, additional experiments were conducted. With acyl azolium ion 8 as the substrate in the absence of the NHC, 4-methylstyrene reacted in 51% yield to give vinyl ketone 3a, indicating that acyl azoliums B (see Scheme 1) are competent intermediates (Scheme 4a). The reaction between α-methylstyrene and benzoyl fluoride with 1 equiv of p-chlorophenyl sulfinate furnished the three-component coupling product 9 in 48% yield (Scheme 4b). The absence of an acidic proton at the position β to the sulfone moiety prevents the sulfinate elimination, showing that three-component products of type D are intermediates in these cascades.

Scheme 4. Mechanistic Studies.

Furthermore, to investigate the sulfinate elimination from D, a parallel kinetic isotope effect (KIE) experiment was carried out using 1z and [D]-1z as substrates (Scheme 4c). The two reactions were stopped after 40 min, and on the basis of the individual conversions, a KIE value of 2.8 was calculated. A competition KIE experiment using equal amounts of 1z and [D]-1z (0.5 equiv each) was stopped after 40 min, and analysis of the unreacted starting alkene revealed a KIE value of 2.2 (Scheme 4d). These results indicate that the deprotonation process might be involved in the rate-determining step. Moreover, when the model reaction was conducted in the presence of 2 equiv of 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl (TEMPO), the α-acylation was not observed. Instead, benzoyl-TEMPO adduct 10 was isolated in 19% yield, suggesting ketyl radical C as an intermediate (Scheme 4e). On the other hand, the formation of adduct radical A was supported by a radical probe experiment using styrene 11 as the acceptor to give ring-opening product 12 (44% yield; Scheme 4f). Finally, fluorescence quenching experiments revealed that only sodium sulfinates quench the excited state of Ru*(II) (see Figure S2 for details), supporting the reductive quenching pathway. Thus, all of these experiments are in line with our suggested mechanism.

In conclusion, we have developed the first example of triple catalysis involving a carbene catalyst in which all three catalysis cycles are interwoven. Along with the carbene, a photoredox catalyst and a sulfinate catalyst are used for α-acylation of alkenes with acyl fluorides to access α-substituted vinyl ketones. The cascade exhibits high functional group tolerance. Successful late-stage modification shows the potential of the method, and useful follow-up chemistry on the product ketones further documents the value of the process. Notably, existing methods for acylation of aryl alkenes usually afford the β-acylation products. Mechanistic studies indicate that the reaction proceeds through a radical addition/coupling/elimination cascade. We are confident that multiple catalysis proceeding through NHC-catalyzed radical transformations will enable the discovery of other novel transformations in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank the European Research Council (Advanced Grant Agreement 692640) for supporting this work.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.1c01022.

Experimental procedures, characterization data, and copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bugaut X.; Glorius F. Organocatalytic umpolung: N-heterocyclic carbenes and beyond. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3511–3522. 10.1039/c2cs15333e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Wang H.; Jin Z.; Chi Y. R. N-Heterocyclic Carbene Organocatalysis: Activation Modes and Typical Reactive Intermediates. Chin. J. Chem. 2020, 38, 1167–1202. 10.1002/cjoc.202000107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.-Y.; Gao Z.-H.; Ye S. Bifunctional N-Heterocyclic Carbenes Derived from L-Pyroglutamic Acid and Their Applications in Enantioselective Organocatalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 690–702. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sarkar S.; Biswas A.; Samanta R. C.; Studer A. Catalysis with N-Heterocyclic Carbenes under Oxidative Conditions. Chem. - Eur. J. 2013, 19, 4664–4678. 10.1002/chem.201203707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders D.; Niemeier O.; Henseler A. Organocatalysis by N-Heterocyclic Carbenes. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5606–5655. 10.1021/cr068372z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanigan D. M.; Romanov-Michailidis F.; White N. A.; Rovis T. Organocatalytic Reactions Enabled by N-Heterocyclic Carbenes. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9307–9387. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo J.; Hutson G. E.; Cohen D. T.; Scheidt K. A. A Continuum of Progress: Applications of N-Hetereocyclic Carbene Catalysis in Total Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11686–11698. 10.1002/anie.201203704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahatthananchai J.; Bode J. W. On the Mechanism of N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Catalyzed Reactions Involving Acyl Azoliums. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 696–707. 10.1021/ar400239v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bera S.; Daniliuc C. G.; Studer A. Oxidative N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalyzed Dearomatization of Indoles to Spirocyclic Indolenines with a Quaternary Carbon Stereocenter. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7402–7406. 10.1002/anie.201701485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow R. On the Mechanism of Thiamine Action. IV.1 Evidence from Studies on Model Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 3719–3726. 10.1021/ja01547a064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai L.; Ye S. Recent advances in N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed radical reactions. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2020, 10.1016/j.cclet.2020.08.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Sarkar S.; Grimme S.; Studer A. NHC Catalyzed Oxidations of Aldehydes to Esters: Chemoselective Acylation of Alcohols in Presence of Amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1190–1191. 10.1021/ja910540j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon R. S.; Biju A. T.; Nair V. Recent advances in employing homoenolates generated by N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) catalysis in carbon–carbon bond-forming reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 5040–5052. 10.1039/C5CS00162E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair V.; Vellalath S.; Babu B. P. Recent advances in carbon–carbon bond-forming reactions involving homoenolates generated by NHC catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 2691–2698. 10.1039/b719083m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn S. S.; Rosen E. L.; Bode J. W. N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Catalyzed Generation of Homoenolates: γ-Butyrolactones by Direct Annulations of Enals and Aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 14370–14371. 10.1021/ja044714b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Hooper J. F.; Lupton D. W. N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalysis via the α,β-Unsaturated Acyl Azolium. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 2583–2596. 10.1021/acscatal.6b03663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders D.; Niemeier O.; Balensiefer T. Asymmetric Intramolecular Crossed-Benzoin Reactions by N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 1463–1467. 10.1002/anie.200503885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon R. S.; Biju A. T.; Nair V. Recent advances in N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC)-catalysed benzoin reactions. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 444–461. 10.3762/bjoc.12.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders D.; Breuer K.; Runsink J.; Teles J. H. The First Asymmetric Intramolecular Stetter Reaction. Preliminary Communication. Helv. Chim. Acta 1996, 79, 1899–1902. 10.1002/hlca.19960790712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jousseaume T.; Wurz N. E.; Glorius F. Highly Enantioselective Synthesis of α-Amino Acid Derivatives by an NHC-Catalyzed Intermolecular Stetter Reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 1410–1414. 10.1002/anie.201006548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathrop S. P.; Rovis T. A photoisomerization-coupled asymmetric Stetter reaction: application to the total synthesis of three diastereomers of (−)-cephalimysin A. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 1668–1673. 10.1039/c3sc22292f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetter H. Catalyzed Addition of Aldehydes to Activated Double Bonds-A New Synthetic Approach. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1976, 15, 639–647. 10.1002/anie.197606391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann A.; Enders D. N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalyzed Domino Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 314–325. 10.1002/anie.201105415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Xing X.-N.; Huang J.-H.; Lu L.-Q.; Xiao W.-J. Light opens a new window for N-heterocyclic carbene catalysis. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 10605–10613. 10.1039/D0SC03595E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M. H.; Scheidt K. A. Cooperative Catalysis and Activation with N-Heterocyclic Carbenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 14912–14922. 10.1002/anie.201605319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y.; Xiang S.; Leow M. L.; Liu X.-W. Dual-function Pd/NHC catalysis: tandem allylation–isomerization–conjugate addition that allows access to pyrroles, thiophenes and furans. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 6168–6170. 10.1039/c4cc01750a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bera S.; Samanta R. C.; Daniliuc C. G.; Studer A. Asymmetric Synthesis of Highly Substituted β-Lactones through Oxidative Carbene Catalysis with LiCl as Cooperative Lewis Acid. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 9622–9626. 10.1002/anie.201405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal-David B.; Raup D. E. A.; Scheidt K. A. Cooperative N-Heterocyclic Carbene/Lewis Acid Catalysis for Highly Stereoselective Annulation Reactions with Homoenolates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 5345–5347. 10.1021/ja910666n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D.-F.; Rovis T. N-Heterocyclic Carbene and Chiral Brønsted Acid Cooperative Catalysis for a Highly Enantioselective [4 + 2] Annulation. Synthesis 2016, 49, 293–298. 10.1055/s-0036-1588349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo J.; Chen X.; Chi Y. R. Oxidative γ-Addition of Enals to Trifluoromethyl Ketones: Enantioselectivity Control via Lewis Acid/N-Heterocyclic Carbene Cooperative Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8810–8813. 10.1021/ja303618z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raup D. E. A.; Cardinal-David B.; Holte D.; Scheidt K. A. Cooperative catalysis by carbenes and Lewis acids in a highly stereoselective route to γ-lactams. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 766–771. 10.1038/nchem.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Chen X.; Wang M.; Zheng P.; Song B.-A.; Chi Y. R. Aminomethylation of Enals through Carbene and Acid Cooperative Catalysis: Concise Access to β2-Amino Acids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 5161–5165. 10.1002/anie.201412132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X.; DiRocco D. A.; Rovis T. N-Heterocyclic Carbene and Brønsted Acid Cooperative Catalysis: Asymmetric Synthesis of trans-γ-Lactams. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12466–12469. 10.1021/ja205714g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z.; Xu J.; Yang S.; Song B.-A.; Chi Y. R. Enantioselective Sulfonation of Enones with Sulfonyl Imines by Cooperative N-Heterocyclic-Carbene/Thiourea/Tertiary-Amine Multicatalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 12354–12358. 10.1002/anie.201305023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo S.; Zhu T.; Zhou L.; Mou C.; Chai H.; Lu Y.; Pan L.; Jin Z.; Chi Y. R. Access to All-Carbon Spirocycles through a Carbene and Thiourea Cocatalytic Desymmetrization Cascade Reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1784–1788. 10.1002/anie.201810638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C.; Fleige M.; Janssen-Müller D.; Daniliuc C. G.; Glorius F. Cooperative N-Heterocyclic Carbene/Palladium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Umpolung Annulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7840–7843. 10.1021/jacs.6b04364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y.-F.; Gao Z.-H.; Zhang C.-L.; Ye S. NHC/Copper-Cocatalyzed [4 + 3] Annulations of Salicylaldehydes with Aziridines for the Synthesis of 1,4-Benzoxazepinones. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 8396–8400. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c03026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K.; Hovey M. T.; Scheidt K. A. A cooperative N-heterocyclic carbene/palladium catalysis system. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 4026–4031. 10.1039/C4SC01536C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namitharan K.; Zhu T.; Cheng J.; Zheng P.; Li X.; Yang S.; Song B.-A.; Chi Y. R. Metal and carbene organocatalytic relay activation of alkynes for stereoselective reactions. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3982. 10.1038/ncomms4982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singha S.; Serrano E.; Mondal S.; Daniliuc C. G.; Glorius F. Diastereodivergent synthesis of enantioenriched α,β-disubstituted γ-butyrolactones via cooperative N-heterocyclic carbene and Ir catalysis. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 48–54. 10.1038/s41929-019-0387-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Chen J.; Huang Y. Aerobic Oxidation/Annulation Cascades through Synergistic Catalysis of RuCl3 and N-Heterocyclic Carbenes. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 12806–12810. 10.1002/chem.201803254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda S.; Ishii T.; Takemoto S.; Haruki H.; Ohmiya H. Synergistic N-Heterocyclic Carbene/Palladium-Catalyzed Reactions of Aldehyde Acyl Anions with either Diarylmethyl or Allylic Carbonates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 2938–2942. 10.1002/anie.201712811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L.; Wu X.; Yang X.; Mou C.; Song R.; Yu S.; Chai H.; Pan L.; Jin Z.; Chi Y. R. Gold and Carbene Relay Catalytic Enantioselective Cycloisomerization/Cyclization Reactions of Ynamides and Enals. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1557–1561. 10.1002/anie.201910922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai L.; Xia Z.-H.; Gao Y.-Y.; Gao Z.-H.; Ye S. Visible-Light-Driven N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalyzed γ- and ϵ-Alkylation with Alkyl Radicals. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 18124–18130. 10.1002/anie.201909017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai L.; Ye S. Photo/N-Heterocyclic Carbene Co-catalyzed Ring Opening and γ-Alkylation of Cyclopropane Enal. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 986–990. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiRocco D. A.; Rovis T. Catalytic Asymmetric α-Acylation of Tertiary Amines Mediated by a Dual Catalysis Mode: N-Heterocyclic Carbene and Photoredox Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8094–8097. 10.1021/ja3030164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.; Zhou L.; Maiti R.; Mou C.; Pan L.; Chi Y. R. Sulfinate and Carbene Co-catalyzed Rauhut–Currier Reaction for Enantioselective Access to Azepino[1,2-a]indoles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 477–481. 10.1002/anie.201810879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z.-H.; Dai L.; Gao Z.-H.; Ye S. N-Heterocyclic carbene/photo-cocatalyzed oxidative Smiles rearrangement: synthesis of aryl salicylates from O-aryl salicylaldehydes. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 1525–1528. 10.1039/C9CC09272B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W.; Hu W.; Dong X.; Li X.; Sun J. N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalyzed γ-Dihalomethylenation of Enals by Single-Electron Transfer. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 15783–15786. 10.1002/anie.201608371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosini L. M.; Lambert T. H. Multicatalysis: Advancing Synthetic Efficiency and Inspiring Discovery. ChemCatChem 2010, 2, 1373–1380. 10.1002/cctc.200900323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr T. L.; Marks T. J. Orthogonal tandem catalysis. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 477–482. 10.1038/nchem.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Yuan P.; Wang L.; Huang Y. Enantioselective β-Protonation of Enals via a Shuttling Strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7045–7051. 10.1021/jacs.7b02889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M. H.; Cohen D. T.; Schwamb C. B.; Mishra R. K.; Scheidt K. A. Enantioselective β-Protonation by a Cooperative Catalysis Strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5891–5894. 10.1021/jacs.5b02887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan P.; Chen J.; Zhao J.; Huang Y. Enantioselective Hydroamidation of Enals by Trapping of a Transient Acyl Species. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 8503–8507. 10.1002/anie.201803556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp B.; Kammer L. M.; Kücükdisli M.; Luque A.; Kühlborn J.; Pusch S.; Matulevičiu̅tė G.; Schollmeyer D.; Šačkus A.; Opatz T. Visible Light-Induced Sulfonylation/Arylation of Styrenes in a Double Radical Three-Component Photoredox Reaction. Chem. - Eur. J. 2019, 25, 8965–8969. 10.1002/chem.201901175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A. U.; Jäger S.; Prasad Hari D.; König B. Visible Light-Mediated Metal-Free Synthesis of Vinyl Sulfones from Aryl Sulfinates. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015, 357, 2050–2054. 10.1002/adsc.201500142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A. U.; Straková K.; Slanina T.; König B. Eosin Y (EY) Photoredox-Catalyzed Sulfonylation of Alkenes: Scope and Mechanism. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 8694–8699. 10.1002/chem.201601000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik M. M. D.; Yuan F.; Yan D.-M.; Xiao W.-J.; Chen J.-R. Visible-Light-Driven Radical Multicomponent Reaction of 2-Vinylanilines, Sulfonyl Chlorides, and Sulfur Ylides for Synthesis of Indolines. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 2639–2644. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c00602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G.; Zhang L.; Yi H.; Luo Y.; Qi X.; Tung C.-H.; Wu L.-Z.; Lei A. Visible-light induced oxidant-free oxidative cross-coupling for constructing allylic sulfones from olefins and sulfinic acids. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 10407–10410. 10.1039/C6CC04109D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.-S.; Cheng Y.; Chen J.; Yu X.-Y.; Xiao W.-J.; Chen J.-R. Copper-Catalyzed Radical Cross-Coupling of Oxime Esters and Sulfinates for Synthesis of Cyanoalkylated Sulfones. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 5300–5305. 10.1002/cctc.201901695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A. V.; Fitzpatrick K. P.; Betori R. C.; Scheidt K. A. Combined Photoredox and Carbene Catalysis for the Synthesis of Ketones from Carboxylic Acids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 9143–9148. 10.1002/anie.202001824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guin J.; De Sarkar S.; Grimme S.; Studer A. Biomimetic Carbene-Catalyzed Oxidations of Aldehydes Using TEMPO. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8727–8730. 10.1002/anie.200802735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Q.-Y.; Döben N.; Studer A. Cooperative NHC and Photoredox Catalysis for the Synthesis of β-Trifluoromethylated Alkyl Aryl Ketones. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 19956–19960. 10.1002/anie.202008040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H. The Persistent Radical Effect: A Principle for Selective Radical Reactions and Living Radical Polymerizations. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 3581–3610. 10.1021/cr990124y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leifert D.; Studer A. The Persistent Radical Effect in Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 74–108. 10.1002/anie.201903726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T.; Kakeno Y.; Nagao K.; Ohmiya H. N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Catalyzed Decarboxylative Alkylation of Aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 3854–3858. 10.1021/jacs.9b00880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T.; Ota K.; Nagao K.; Ohmiya H. N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Catalyzed Radical Relay Enabling Vicinal Alkylacylation of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 14073–14077. 10.1021/jacs.9b07194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota K.; Nagao K.; Ohmiya H. N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Catalyzed Radical Relay Enabling Synthesis of δ-Ketocarbonyls. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 3922–3925. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayly A. A.; McDonald B. R.; Mrksich M.; Scheidt K. A. High-throughput photocapture approach for reaction discovery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 13261–13266. 10.1073/pnas.2003347117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger A. L.; Donabauer K.; König B. Photocatalytic Barbier reaction - visible-light induced allylation and benzylation of aldehydes and ketones. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 7230–7235. 10.1039/C8SC02038H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-L.; Liu Y.-Q.; Zou W.-L.; Zeng R.; Zhang X.; Liu Y.; Han B.; He Y.; Leng H.-J.; Li Q.-Z. Radical Acylfluoroalkylation of Olefins through N-Heterocyclic Carbene Organocatalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1863–1870. 10.1002/anie.201912450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavroskoufis A.; Rajes K.; Golz P.; Agrawal A.; Ruß V.; Götze J. P.; Hopkinson M. N. N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalyzed Photoenolization/Diels-Alder Reaction of Acid Fluorides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 3190–3194. 10.1002/anie.201914456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song R.; Chi Y. R. N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalyzed Radical Coupling of Aldehydes with Redox-Active Esters. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 8628–8630. 10.1002/anie.201902792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.-B.; Wang Z.-H.; Li J.-M.; Wu C. Modular synthesis of α-aryl β-perfluoroalkyl ketones via N-heterocyclic carbene catalysis. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 3801–3804. 10.1039/D0CC00293C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Peng Q.; Guo D.; Wang J. NHC-Catalyzed Radical Trifluoromethylation Enabled by Togni Reagent. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 443–447. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b04203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S.; Qin J.; Wang F.; Li H.; Chu L. Photoredox-catalyzed branch-selective pyridylation of alkenes for the expedient synthesis of Triprolidine. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 749. 10.1038/s41467-019-08669-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A. K.; Morgan J. P.; Scholl M.; Grubbs R. H. Synthesis of Functionalized Olefins by Cross and Ring-Closing Metatheses. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 3783–3784. 10.1021/ja9939744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Z.; Banerjee A.; Kusevska E.; Rizzo E.; Liu P.; Ngai M.-Y. β-Selective Aroylation of Activated Alkenes by Photoredox Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 7318–7323. 10.1002/anie.201901874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Alvarado J. I.; Ertel A. B.; Stegner A.; Stache E. E.; Doyle A. G. Direct Use of Carboxylic Acids in the Photocatalytic Hydroacylation of Styrenes To Generate Dialkyl Ketones. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 9940–9944. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkiewicz A. A.; Kalek M. N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Catalyzed Olefination of Aldehydes with Vinyliodonium Salts To Generate α,β-Unsaturated Ketones. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1906–1909. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Liu C.; Yuan J.; Lei A. Copper-Catalyzed Oxidative Coupling of Alkenes with Aldehydes: Direct Access to α,β-Unsaturated Ketones. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2256–2259. 10.1002/anie.201208920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gembus V.; Bonnet J.-J.; Janin F.; Bohn P.; Levacher V.; Brière J.-F. Synthesis of pyrazolines by a site isolated resin-bound reagents methodology. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 3287–3293. 10.1039/c004704j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.-Z.; Shang R.; Cheng W.-M.; Fu Y. Decarboxylative 1,4-Addition of α-Oxocarboxylic Acids with Michael Acceptors Enabled by Photoredox Catalysis. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 4830–4833. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.