Abstract

Study Objectives:

Social relationships are an understudied factor affecting insomnia. In particular, these effects have not been evaluated in the context of sex differences. In this study, we investigated differences between sexes with regard to the association between insomnia symptoms and social relationships.

Methods:

We used data from 2681 middle-aged adults (aged 40–64 years; females, 68.8%) from the Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases Etiology Research Center project. Insomnia symptoms were defined as difficulty with sleep induction or maintenance ≥3 nights per week. We assessed social network size and bridging potentials as indicators of social relationships. Social network size is a quantitative measure of the size of social relationships, and bridging potential is a qualitative indicator of the diversity and independence of these relationships. Multivariate regression analysis controlling for confounding factors was performed to evaluate associations between social relationships and insomnia symptoms.

Results:

Smaller social network size was significantly associated with sleep induction (adjusted odds ratio = 0.866, P = .015) and sleep maintenance (adjusted odds ratio = 0.862, P = .015) difficulties, but only in men. Poor bridging potential was also associated with sleep induction (adjusted odds ratio = 0.321, P = .024) and maintenance (adjusted odds ratio = 0.305, P = .031) difficulties only in men. For women, social relationship variables were not significantly associated with insomnia symptoms.

Conclusions:

The association between insomnia symptoms and social relationships varied by sex, as noted by statistical analyses accounting for covariates affecting insomnia symptoms. These results suggest that qualitative assessments of social relationship variables should be considered in clinical practice, since these variables can be interpreted differently for men and women.

Citation:

Park K, Cho D, Lee E, et al. Sex differences in the association between social relationships and insomnia symptoms. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(11):1871–1881.

Keywords: insomnia, social relationship, social network size, bridging potential, sex difference

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Social relationships are one of the factors affecting insomnia, yet few studies have investigated the effects of these relationships on insomnia. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the effects of social relationships on insomnia symptoms in the context of differences between men and women.

Study Impact: We found that a larger social network size and higher bridging potential are beneficial for sleep only in men, not in women. These findings suggest that different approaches should be considered for men and women when assessing social relationship variables in people with insomnia symptoms.

INTRODUCTION

Insomnia can have major adverse health effects. In addition to worsening psychiatric conditions, including depression and suicidal ideation, and physical disorders, such as cardiovascular disease, insomnia may also increase overall mortality.1–3 Insomnia is an especially important issue in Korea. In 2019, the mean daily sleep time in Korea was reported to be 469 minutes, which was the shortest for all Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries.4 The prevalence of insomnia in Korea is increasing annually, with a 34.3% increase in the number of people seeking medical services for insomnia from 2012 to 2016.5 The cost of medical treatment for insomnia increased from 23.5 million dollars to 38.3 million dollars over the same 5-year period.6

Among the various factors affecting insomnia, social relationships have received recent research interest. Social relationships can be a “double-edged sword” for health outcomes: they can be a source of social support7,8 or a conduit for stress or unhealthy behaviors.9,10 A few studies have investigated the effects of social relationships on insomnia. These studies reported that perceived social support or satisfaction with social relationships had a beneficial effect on sleep and that perceived loneliness was associated with insomnia.11–14 Most of these studies were conducted in older adults,12–14 and they all had substantial drawbacks limiting the ability to make firm conclusions, including the use of simple social indicators, such as marital status, or the use of self-reported social support, lacking in objectivity. Previous studies regarding the association between social relationships and health outcomes showed that perceived social support alone cannot reflect the full range of aspects related to social relationships.15,16 Although no published study has directly compared the superiority of objective measurements of social relationships over self-reported measurements, it has been assumed that more objective measurement methods are necessary to assess social relationship variables as risk factors affecting health outcomes and thereby develop appropriate preventive or treatment interventions.

Social network analysis is a methodology reflecting the complex aspects of social relationships, which is used for measuring and analyzing the structural properties of social relationship, social networks.17,18 Social networks are defined as webs of social ties, which include the density of the network, as well as the number, homogeneity, and geographic proximity of the network members. Social network analysis measures the behavior of individuals at the “micro” level, patterns of relationships at the “macro” level, and interactions between individuals.19 It has advantages over perceived social support analysis for reflecting the structural context in which individuals relate with each other within a whole community.20 Social network analysis allows assessment of multidimensional aspects of social relationships, such as size, structure, diversity, density, and connections among subgroups, using more objective and quantifiable indicators.21 In this study, we performed social network analysis with social network size and bridging potential as subindicators to systematically investigate the effects of social relationships on insomnia symptoms. With social network size (one of the most widely used quantitative indicators for statistical analysis in the field of sociology22,23), we can assess the quantity of social relationships between individuals. Bridging potential is a social relationship measurement assessing diversity and independence of a person’s social network. We can assess the composition of network members and the positions each individual occupies within his or her social relationships by determining the bridging potential. Using these 2 measurements, we can evaluate the quantity and diversity of an individual’s social relationships.

Previous studies confirmed interaction effects of sex on associations between social relationships and general health outcomes.24,25 It is also known that female sex is a risk factor for insomnia.26 Women have fewer opportunities to sleep because of their numerous social roles, such as the need to care for their families in addition to their professional responsibilities.27 Stereotypes of women as enduring, serving, and pleasing others persist in Korea because of the country’s traditional culture.28 Mothers in South Korea are expected to be supportive for various members of their family: they are responsible for maintaining the harmony and integrity of the family, for supporting the occupational activities of their husband, and for assisting the achievement of academic success of their children.29 Indeed, research conducted in South Korea demonstrated that middle-aged women sleep the least amount of time of all age and sex groups, likely because of their role as social support providers of the family, resulting in less sleep than other family members.30 Taken together, these observations suggest the possibility of sex-specific differences in the relationships between insomnia symptoms and social network size. In this study, our aim was to use social network analysis to explore potential sex differences in the association between insomnia symptoms and social relationships.

METHODS

Study population and design

In this study, we used data from the Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases Etiology Research Center project, which is a prospective community-based, general-population cohort.31 Baseline measurements assessed various factors, including sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, health-related behaviors, psychological health, social network, and social support. For this study, we used data solely from middle-aged adults (aged 40–64 years) of the Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases Etiology Research Center cohort, collected at a Yonsei University Medical Center clinic from December 2013 to March 2017. Assessing a middle-aged cohort enables early identification and modification of risk factors.32 If social relationship factors, such as social network size, are beneficial for insomnia symptoms, modifying the factors early in the middle-aged adult population could be an effective preventive strategy. The protocol for this study was approved by the institutional review board of Severance Hospital, Yonsei University Health System, Seoul, Korea (4-2013-0661). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before collecting baseline measurements.

Assessments

Patient characteristics

The following data were collected from patient self-reported questionnaires: age, sex, obesity (body mass index ≥25 kg/m2),33 marital status (currently living with spouse or not), educational status (high school graduation or less), perceived economic status (above average or poor), current smoking status, current drinking alcohol status, depression (Beck Depression Inventory–II score ≥14),34 and past or current medical disorders. Currently living with spouse status was defined as married and nonmarried couples living together, whereas currently not living with spouse was defined as individuals who were single, divorced, widowed, or married but living apart from their partner. Past or current medical disorders included stroke, transient ischemic attack, myocardial infarction, angina, heart failure, chronic renal disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, thyroid disease, fatty liver, liver cirrhosis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, osteoporosis, arthritis, autoimmune disease, and cancer. In addition, high risk for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) status was determined using the Berlin questionnaire, which is a validated measure for identifying patients at risk for OSA.35

Social relationships

To assess social relationships, we performed face-to-face interviews using a questionnaire developed for the Korean Social Life, Health, and Aging Project.36 This questionnaire involved assessments of relationships with the spouse and other individuals with whom the respondents discussed important matters (ie, nonspousal social network members) (Questionnaire S1). The questionnaire queried patients about their social relationships during the preceding 12 months. It asked respondents to provide information about their relationship with each network member, each network member’s demographic characteristics (including sex, age, cohabitation status, and educational status), how often they talk to or meet with each network member, and the degree to which they feel emotionally close to each network member.

Social network size was defined as the number of spouses (0 or 1) plus the number of nonspousal network members (0 to 5); thus, the network size ranged from 0 to 6. Social network size was obtained from the name generator,37 a standardized survey module measuring social networks.38–40 The name generator questionnaire first asked for the total number of friends (with no upper limit) and then asked the study participant to provide their friends' names (up to 6); the size of the social network was defined as the total number of these names.37 We also recorded whether participants had social network members outside their family. The participants’ emotional reliance on their spouse was queried and designated as “yes” if the response was often or frequently.

In addition to social network size, we assessed the bridging potential of participants. Bridging potential is an indicator of the diversity in the network of individuals and the independence of the social network.41,42 We used 2 measures of bridging potential: (1) whether the participant serves as the only link between any 2 unconnected individuals, called the “bridging status,” and (2) whether at least 1 network member was not connected to any other network member, called an “isolated alter” (Figure 1). Both measures were used for assessing diversity and independence in the social network. Individuals with a higher bridging potential tend to have wider resources from different social domains, have more opportunities to control the flow of information, and are more independent than others because of the diverse composition of their network.41 The bridging potential was quantified as the number of pairs of alters in the participant’s network who were not directly connected to each other. “Yes” responses to the 2 abovementioned questions indicate that the participants have bridging potential socially.

Figure 1. Concepts of bridging status and isolated alter.

(A) Bridging status: A serves as the only link between otherwise unconnected individuals or groups. (B) Isolated alter: a network member (known as an “isolated alter” in B’s network) does not connect to any other member of the network. (C) No bridging status or isolated alter: C does not serve as the only link between 2 other individuals, and all network members connect to at least 1 other member in addition to C.

Sleep

A self-reported questionnaire was used to assess insomnia symptoms. This sleep questionnaire has been verified with regard to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) insomnia criteria in previous peer-reviewed publications using large-scale cohorts.43–45 The questionnaire (Questionnaire S2) included queries regarding total sleep time, difficulty with sleep induction, and difficulty with sleep maintenance. Difficulty with sleep induction and sleep maintenance was rated as follows: “no,” “sometimes (1–2 days per week),” “often (3–4 days per week),” and “almost every day (≥ 5 days per week).” We defined insomnia symptoms as difficulty with sleep induction or maintenance for 3 or more days per week, based on DSM-5 insomnia criteria A and C.45

Statistical analysis

We performed independent-sample t tests, χ2 tests, and multivariate regression analysis to evaluate sex differences in social relationships and their impact on insomnia symptoms. Independent-sample t tests and χ2 tests were used to compare differences between men and women for demographic factors, factors related to insomnia, and social relationship factors, including social network size and bridging potentials. Continuous data are shown as means ± SDs, whereas categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess the relationship between selected independent variables, including social relationship factors, and the probability of insomnia symptoms. We chose this type of analysis to confirm whether there was a statistically significant association between social relationship factors and insomnia symptoms, while assessing the impact of multiple variables in the same model.46 Models were adjusted for age, marital status, education, obesity, perceived economic status, smoking status, alcohol drinking status, medical disorders, depression, and higher risk for OSA. Age and social network size were continuous variables, and all other variables were binary categorical variables. Regression coefficients (B), adjusted odds ratios, statistical significance (P values), and 95% confidence intervals were reported for the regression analyses. Two-sided P values < .05 were considered statistically significant, and models were inspected for goodness of fit using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Additional regression analysis regarding social network size as a categorical variable was performed to determine whether there was a change in the correlation between insomnia symptoms and social network size, when classified into 3 categories: social network size 0–2, social network size 3–4, or social network size 5–6. Multicollinearity, a linear relationship between 2 or more explanatory variables being detected by the variance inflation factor,47 was evaluated to avoid unreliability of the estimates in the model parameters.48 A variance inflation factor more than 10 was considered to represent a serious multicollinearity problem, leading to a large standard error that could interfere with the model’s estimates.49 The highest variance inflation factor in our regression analysis models did not exceed 2.5, indicating that multicollinearity was not an appreciable concern in this study. All analyses were conducted with SPSS for Windows version 25.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 2681 study participants (aged 40–64 years) are shown in Table 1. Social network size was larger in women than in men. Women also had a shorter self-reported total sleep time, as well as higher rates of depression, difficulty with sleep induction, and difficulty with sleep maintenance. Men had higher rates of obesity, being at high risk for OSA, living with a spouse, graduating from high school, currently smoking, and currently drinking alcohol. Having bridging status (participant serving as the only link between any 2 unconnected pairs) was significantly higher in women, whereas the presence of isolated alter (2 other network members talking to each other less than 2 times per month) was not significantly different between men and women. Women reported having more friends outside the family than men. Men were more likely than women to be emotionally dependent on their spouse.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 2681) | Men (n = 836) | Women (n = 1845) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (40–64 years), years | 54.74 (6.13) | 55.09 (6.47) | 54.58 (5.97) | .051 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) | 895 (33.4) | 371 (44.4) | 524 (28.4) | <.001* |

| Not living with spouse | 325 (12.1) | 30 (3.6) | 295 (16.0) | <.001* |

| Less than high school education | 506 (18.9) | 98 (11.7) | 408 (22.1) | <.001* |

| Poor perceived economic status | 770 (28.7) | 224 (26.8) | 546 (29.6) | .138 |

| Currently smoking | 286 (10.7) | 245 (29.3) | 41 (2.2) | <.001* |

| Currently drinking alcohol | 1804 (67.3) | 693 (82.9) | 1111 (60.2) | <.001* |

| Past or current medical disorder | 1347 (50.2) | 406 (48.6) | 941 (51.0) | .242 |

| Depression (BDI ≥14) | 683 (25.5) | 165 (19.7) | 518 (28.1) | <.001* |

| High risk for OSAa | 524 (19.5) | 231 (27.6) | 293 (15.9) | <.001* |

| Social network size, (0–6) | 3.99 (1.61) | 3.80 (1.70) | 4.07 (1.55) | <.001* |

| Having bridging status | 177 (66.1) | 518 (62.0) | 1254 (68.0) | .003* |

| Presence of isolated alter | 1636 (601.0) | 489 (58.5) | 1147 (62.2) | .073 |

| Having nonfamily friends | 1826 (68.1) | 538 (64.4) | 1288 (69.8) | .006* |

| Emotionally dependent on spouse | 2084 (77.7) | 673 (80.5) | 1411 (76.5) | .001* |

| Self-reported daily total sleep time, minutes | 410.86 (73.2) | 416.38 (73.7) | 408.36 (72.8) | .009* |

| Difficulty with sleep induction ≥3 times/week | 420 (15.7) | 86 (10.3) | 334 (18.1) | <.001* |

| Difficulty with sleep maintenance ≥3 times/week | 361 (13.5) | 87 (10.4) | 274 (14.9) | .002* |

Values are expressed as means (SDs) for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables. *Statistically significant differences between men and women. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BMI = body mass index; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

People with a high risk for OSA according to the Berlin questionnaire.

Association between insomnia symptoms and social network size

Multivariate logistic regression analyses of factors associated with sleep induction difficulty and sleep maintenance difficulty are shown in Table 2 and Table 3. Beneficial effects of social network size on insomnia symptoms were found only in men. A smaller social network size was significantly associated with sleep induction difficulty (adjusted odds ratio = 0.866, P = .015) and sleep maintenance difficulty (adjusted odds ratio = 0.862, P = .015) in men but not in women (Figure 2). Additional analysis with social network size as a categorical variable showed that, in men, the group with the smallest social network (social network size 0–2) had an odds ratio of 1.875 (1.064–3.302) for sleep induction difficulty, compared with the group with the largest social network (social network size 5–6) (Table S1 and Table S2). Not living with spouse, depression, and high risk for OSA were factors related to insomnia symptoms in both sexes. Currently smoking and past or current medical disorder were associated with insomnia symptoms only in men, whereas age and poor perceived economic status were significantly associated with sleep maintenance difficulty in women, but not in men.

Table 2.

Association between difficulty with sleep induction and social network size in men and women.

| Variables | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | P | aOR (95% CI) | B | P | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Social network size | −0.144 | .015* | 0.866 (0.771–0.973) | 0.008 | .835 | 1.008 (0.936–1.085) |

| Age | 0.008 | .499 | 1.008 (0.985–1.031) | 0.008 | .281 | 1.008 (0.993–1.023) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) | −0.384 | .068 | 0.681 (0.451–1.029) | 0.044 | .737 | 1.045 (0.809–1.350) |

| Not living with spouse | 1.038 | <.001* | 2.823 (1.603–4.969) | 0.352 | .015* | 1.422 (1.071–1.889) |

| Less than high school education | 0.380 | .236 | 1.463 (0.780–2.743) | 0.103 | .493 | 1.109 (0.825–1.489) |

| Poor perceived economic status | −0.203 | .381 | 0.816 (0.519–1.285) | 0.237 | .056 | 1.268 (0.994–1.618) |

| Currently smoking | 0.541 | .010* | 1.718 (1.138–2.593) | 0.474 | .099 | 1.606 (0.914–2.821) |

| Currently drinking alcohol | 0.187 | .547 | 1.206 (0.656–2.217) | 0.004 | .974 | 1.004 (0.793–1.271) |

| Past or current medical disorder | 0.187 | .391 | 1.206 (0.786–1.849) | 0.081 | .530 | 1.085 (0.842–1.397) |

| Depression (BDI ≥14) | 0.845 | <.001* | 2.328 (1.502–3.605) | 0.812 | <.001* | 2.253 (1.781–2.851) |

| High risk for OSAa | 0.434 | .048* | 1.543 (1.004–2.372) | 0.481 | .001* | 1.618 (1.205–2.174) |

Social network size and age were continuous variables; all other variables were binary categorical variables. *Statistically significant. aOR = adjusted odds ratio; B = regression coefficient; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

People with a high risk for OSA according to the Berlin questionnaire.

Table 3.

Association between difficulty with sleep maintenance and social network size in men and women.

| Variables | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | P | aOR (95% CI) | B | P | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Social network size | −0.148 | .015* | 0.862 (0.765–0.972) | 0.027 | .511 | 1.028 (0.947–1.114) |

| Age | 0.005 | .712 | 1.005 (0.981–1.029) | 0.022 | .010* | 1.022 (1.005–1.040) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) | −0.01 | .963 | 0.990 (0.651–1.506) | −0.183 | .211 | 0.833 (0.625–1.109) |

| Not living with spouse | 0.446 | .196 | 1.562 (0.795–3.069) | 0.332 | .035* | 1.394 (1.023–1.899) |

| Less than high school education | 0.551 | .079 | 1.736 (0.938–3.212) | 0.100 | .533 | 1.105 (0.807–1.515) |

| Poor perceived economic status | −0.083 | .730 | 0.920 (0.575–1.474) | 0.374 | .005* | 1.453 (1.117–1.890) |

| Currently smoking | 0.021 | .928 | 1.021 (0.655–1.591) | 0.142 | .672 | 1.153 (0.597–2.225) |

| Currently drinking alcohol | 0.321 | .312 | 1.379 (0.739–2.573) | 0.062 | .640 | 1.063 (0.822–1.376) |

| Past or current medical disorder | 0.636 | .004* | 1.889 (1.218–2.929) | 0.131 | .349 | 1.14 (0.866–1.501) |

| Depression (BDI ≥14) | 0.648 | .006* | 1.912 (1.200–3.049) | 0.782 | <.001* | 2.187 (1.692–2.826) |

| High risk for OSAa | 0.265 | .244 | 1.303 (0.835–2.035) | 0.330 | .046* | 1.390 (1.005–1.923) |

Social network size and age were continuous variables; all other variables were binary categorical variables. *Statistically significant. aOR = adjusted odds ratio; B = regression coefficient; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

People with a high risk for OSA according to the Berlin questionnaire.

Figure 2. Adjusted odds ratios of social network size for insomnia symptoms in men and women.

Models were adjusted for age, marital status, education, obesity, perceived economic status, smoking status, alcohol drinking status, medical disorders, depression, and high risk for obstructive sleep apnea. *Statistically significant.

Association between insomnia symptoms and bridging potentials

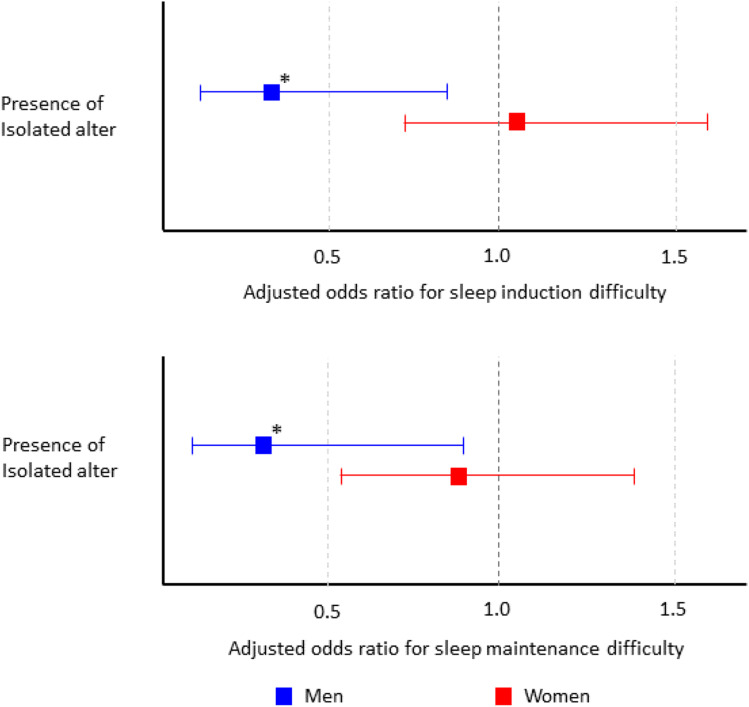

As shown in the results of the association between bridging potentials and difficulty with sleep induction (Table 4) and difficulty with sleep maintenance (Table 5), the presence of isolated alter was significantly associated with sleep induction and maintenance difficulty only in men, not in women (Figure 3). Depression was significantly associated with sleep induction difficulty in both sexes. Currently smoking was the only factor significantly associated with insomnia symptoms solely in men. Age, obesity, poor perceived economic status, and high risk for OSA were significantly associated with insomnia symptoms only in women.

Table 4.

Association between difficulty with sleep induction and bridging potentials in men and women.

| Variables | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | P | aOR (95% CI) | B | P | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Having bridging status | 0.583 | .244 | 1.792 (0.672–4.778) | −0.083 | .680 | 0.921 (0.622–1.363) |

| Presence of isolated alter | −1.136 | .024* | 0.321 (0.120–0.862) | 0.055 | .796 | 1.057 (0.694–1.611) |

| Having nonfamily friends | −0.017 | .947 | 0.983 (0.589–1.640) | 0.042 | .788 | 1.043 (0.766–1.422) |

| Emotionally dependent on spouse | −0.225 | .466 | 0.799 (0.437–1.461) | −0.127 | .419 | 0.881 (0.649–1.198) |

| Age | −0.001 | .948 | 0.999 (0.959–1.039) | 0.034 | .011* | 1.035 (1.008–1.062) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) | −0.345 | .182 | 0.709 (0.427–1.175) | 0.041 | .790 | 1.042 (0.769–1.413) |

| Not living with spouse | −19.142 | .999 | 0.001 (0.001–0.001) | 0.817 | .054 | 2.263 (0.985–5.200) |

| Less than high school education | 0.402 | .254 | 1.495 (0.749–2.984) | 0.077 | .653 | 1.080 (0.772–1.511) |

| Poor perceived economic status | −0.468 | .129 | 0.626 (0.342–1.145) | 0.372 | .013* | 1.451 (1.081–1.948) |

| Currently smoking | 0.916 | <.001* | 2.499 (1.497–4.170) | 0.182 | .771 | 1.199 (0.354–4.066) |

| Currently drinking alcohol | −0.049 | .885 | 0.952 (0.489–1.852) | −0.017 | .907 | 0.983 (0.744–1.300) |

| Past or current medical disorder | 0.035 | .890 | 1.035 (0.634–1.691) | 0.120 | .422 | 1.127 (0.841–1.511) |

| Depression (BDI ≥14) | 0.771 | .008* | 2.162 (1.225–3.814) | 0.740 | <.001* | 2.097 (1.573–2.795) |

| High risk for OSAa | 0.108 | .699 | 1.114 (0.644–1.928) | 0.475 | .007* | 1.608 (1.137–2.275) |

Age was a continuous variable; all other variables were binary categorical variables. *Statistically significant. aOR = adjusted odds ratio; B = regression coefficient; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

People with a high risk for OSA according to the Berlin questionnaire.

Table 5.

Association between difficulty with sleep maintenance and bridging potentials in men and women.

| Variables | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | P | aOR (95% CI) | B | P | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Having bridging status | 1.004 | .063 | 2.729 (0.946–7.876) | 0.134 | .559 | 1.143 (0.730–1.789) |

| Presence of isolated alter | −1.188 | .031* | 0.305 (0.104–0.896) | −0.144 | .554 | 0.866 (0.537–1.395) |

| Having nonfamily friends | −0.283 | .266 | 0.753 (0.457–1.241) | −0.206 | .211 | 0.814 (0.589–1.124) |

| Emotionally dependent on spouse | −0.399 | .190 | 0.671 (0.370–1.219) | −0.057 | .735 | 0.945 (0.679–1.315) |

| Age | −0.017 | .400 | 0.983 (0.946–1.023) | 0.038 | .010* | 1.038 (1.009–1.069) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) | −0.018 | .942 | 0.982 (0.604–1.599) | −0.350 | .049 | 0.704 (0.497–0.998) |

| Not living with spouse | −18.862 | .999 | 0.001 (0.001–0.001) | −0.213 | .704 | 0.808 (0.269–2.431) |

| Less than high school education | 0.521 | .127 | 1.685 (0.862–3.292) | 0.222 | .225 | 1.248 (0.872–1.787) |

| Poor perceived economic status | −0.22 | .457 | 0.803 (0.449–1.433) | 0.379 | .020* | 1.460 (1.061–2.009) |

| Currently smoking | −0.093 | .739 | 0.911 (0.526–1.576) | 0.109 | .871 | 1.115 (0.300–4.145) |

| Current drinking alcohol | 0.215 | .529 | 1.240 (0.635–2.425) | 0.04 | .798 | 1.041 (0.768–1.410) |

| Past or current medical disorder | 0.479 | .058 | 1.614 (0.985–2.646) | 0.184 | .257 | 1.202 (0.875–1.652) |

| Depression (BDI ≥14) | 0.527 | .070 | 1.694 (0.957–2.999) | 0.592 | <.001* | 1.807 (1.320–2.474) |

| High risk for OSAa | 0.047 | .863 | 1.048 (0.614–1.789) | 0.290 | .143 | 1.337 (0.907–1.971) |

Age was a continuous variable; all other variables were binary categorical variables. *Statistically significant. aOR = adjusted odds ratio; B = regression coefficient; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

People with a high risk for OSA according to the Berlin questionnaire.

Figure 3. Adjusted odds ratios of bridging potential for insomnia symptoms in men and women.

Models were adjusted for age, marital status, education, obesity, perceived economic status, smoking status, alcohol drinking status, medical disorders, depression, and high risk for obstructive sleep apnea. *Statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that the effects of social relationships on insomnia symptoms vary according to sex in middle-aged Koreans. Associations between social network size and difficulty with both sleep induction and sleep maintenance were found only in men, despite social networks being larger in women. Good bridging potential, reflecting diverse and independent social relationships, was also associated with less sleep induction difficulty, but only in men. These results were obtained after controlling for previously known risk factors for insomnia and suggest the need to manage the impact of social relationships on insomnia differently, depending on the individual’s sex.

Beneficial effects of social network size for insomnia symptoms in men may be associated with perceived social support or satisfaction with social relationships. It is known that the number of confidants in a social network predicts satisfaction with social support.50 Social support, including a sense of belonging, has beneficial effects on insomnia by improving self-reported sleep quality, reducing wake time after sleep onset, and lowering the rate of insomnia.11,13,14 The benefits of perceived social support can be explained by several mechanisms. First, social support could moderate anxiety and stress, which may be factors perpetuating chronic insomnia.51,52 Social support can reduce negative emotions, including loneliness, by providing a sense of belonging and inducing a positive mood.53 Second, negative physiologic effects of poor social support could lead to disturbed immune function, including elevated inflammatory markers, which are associated with insomnia.54,55 Last, social support might help maintain normal circadian rhythms, including appropriate sleep-wake cycles, by providing scheduled social events for a person to attend.56

It is notable that the beneficial effects of social relationships on insomnia symptoms were not present in women. Previous social network studies also reported that network size had positive effects on men's health and mortality, which were not found in women.24,25 In studies by Baek et al.,24 network density was associated with women's health care behavior. As we did not conduct a complete network analysis to evaluate network density, we were unable to confirm this effect. Instead, we investigated the association between insomnia symptoms and bridging potentials, which reflect the diversity of social relationships, and noted that these potentials were also associated with sleep only in men. Baek et al.24 also suggested that network size in men improves health-related behaviors, maintains psychological health, and promotes self-esteem via providing social support. Compared with women, men are more likely to focus on shared activities instead of relational support from close friendships.57 Greater social network size may have served as an opportunity for men to participate in more shared activities.

Although network size was larger in women, it seemed to have little relation to perceived social support in individuals of this sex. This result might reflect different social requirements of men and women. Shye et al.25 suggested that a larger social network size in women implies greater responsibility for providing informal care to others, as women are socially required to perform more caregiving roles than men.58 In South Korea, mothers are expected to provide support to various family members. They are responsible for maintaining harmony and integrity of the family by supporting their husband and children.29 This supportive role of women is also required outside the family,28 leading to greater responsibility when social network size increases. Women also tend to have more psychological distress from greater exposure and vulnerability to social network events, which is known as a high cost of caring.59 As explained by Kawachi and Berkman,60 women tend to mobilize and provide more social support during times of stress, which can lead to a “contagion of stress” wherein they develop distress in response to the stressful events of others. Similarly, bridging potentials likely represent not only diverse and independent social relationships in women but also positions providing more social support. Bridging position refers to the position within a social network in which 1 person serves as the link between 2 other people who are not connected to each other directly (ie, positive bridging status).61–63 Occupying this position might benefit the individual’s mental health by providing more opportunities for social contact and stability of the social network because of the heterogeneity of group. However, the bridging position may lead to greater psychological costs when the 2 parties not connected to each other have different (or even conflicting) social backgrounds.61 One study reported that, for men, being in the bridging position of a social network can be a mentally stimulating experience, as well as a source of social support.57 Conversely, another study noted that, for women, being in a bridging position could require more psychological resources, while providing less fulfilling social support.33,62 The difference between sexes with respect to the effects of bridging potential on perceived social support could also be explained by the differences in position that men and women have in social relationships. The above results thereby suggest that a large social network size or the presence of bridging potential should not be regarded as equivalent to greater social support in women.

Other factors related to insomnia symptoms were also found to differ between sexes. Factors associated with insomnia symptoms in both men and women were not living with their spouse, depression, and high risk for OSA. For women, age, obesity, and poor perceived economic status were also significantly associated with insomnia symptoms. For men, currently smoking was significantly correlated with sleep induction difficulty, whereas past or current medical disorder was significantly correlated with sleep maintenance difficulty. Most factors associated with insomnia symptoms in this study, including age, depression, smoking, medical disorders, obesity, and loneliness (reflected by marital status),64 are known risk factors for insomnia.11,65,66 Poor perceived economic status is another known risk factor for insomnia,67 yet it was only a significant factor for women in the current study. Previous studies regarding the relationship between poor socioeconomic status and insomnia have generally not reported differences between sexes.68,69 We cannot definitively state that poor perceived economic status is a sex-specific risk factor, yet this could be an interesting topic for further study.

We acknowledge several limitations in this study. First, the study design does not allow us to determine cause-and-effect relationships. Although social relationships may affect insomnia symptoms, it is quite possible that sleep difficulties may lead to alterations in social relationships. Second, insomnia symptoms were based on a self-reported questionnaire. The questionnaire used in this study has been peer-reviewed by psychiatrists and is in accordance with those used in previous large-scale cohort studies measuring insomnia with self-questionnaires.43,44,70 Still, the presence of insomnia symptoms identified in this study cannot be regarded as a confirmed diagnosis of insomnia. Nevertheless, our results are of value because the diagnosis of insomnia in clinical practice also usually relies on the self-reports of patients. Third, the specific characteristics of social relationships were not evaluated in this study. Some social relationships, including relationships with aging relatives or young children, could produce more caregiver dynamics, regardless of an individual’s sex, which may have influenced the results. Fourth, the assessment for menopause, which is well known to affect women’s insomnia symptoms,71 was not done in the cohort. It may have been possible to show in-depth interpretations of factors related to women’s insomnia and social relationship through the analysis of menopausal status. Last, the study examined one-way social networks of study participants. We did not conduct a complete social network analysis measuring the social relationships of both research participants and those engaging in social relationships and thereby did not generate complete information about the social relationships.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show differences between sexes with regard to the effects of social relationships on insomnia symptoms. A previous study reported that social support had beneficial effects on sleep, but no systematic study has investigated the nature of social relationships affecting sleep.72 The social network analysis used in this study provided a more objective and systematic approach for examining the importance of social relationships. This study is also meaningful because it examined a large number of risk factors for insomnia symptoms among middle-aged participants representing the general population. Determining risk factors for insomnia in middle-aged people could contribute to early identification of high-risk individuals and implementation of strategies to modify risk factors. Furthermore, the results of this study are especially important because social relationships are potentially modifiable, in contrast to some other factors, such as age or sex. These results also suggest that different approaches should be used to interpret social relationships in men and women with insomnia symptoms. Men and women should be treated differently with respect to social relationships when intervening to reduce risk factors for insomnia in middle-aged participants.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we found that the association between social relationships and insomnia symptoms differed between sexes. Both a larger social network and greater bridging potential are beneficial for insomnia symptoms only in men. Of note, these results were obtained by systematic assessment of social relationships and statistical analysis controlling for other covariates that can affect insomnia. Our findings suggest that qualitative assessment of social relationship variables should be considered in clinical practice, since these variables can be interpreted differently for each sex.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have seen and approved the final version of this manuscript. Work for this study was performed at the Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea. This study was funded by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF); the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning, Republic of Korea (grant number: 2017R1A2B3008214 to Eun Lee); the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI); the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI13C0715 to Hyeon Chang Kim); and the Intelligence Information Expansion Support System for Private Organizations supervised by the National IT Industry Promotion Agency (grant number: A0602-19-1020 to Eun Lee). The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ABBREVIATION

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

REFERENCES

- 1.Taylor DJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH. Insomnia as a health risk factor. Behav Sleep Med. 2003;1(4):227–247. 10.1207/S15402010BSM0104_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Itani O, Jike M, Watanabe N, Kaneita Y. Short sleep duration and health outcomes: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Sleep Med. 2017;32:246–256. 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luyster FS, Strollo PJ Jr, Zee PC, Walsh JK; Boards of Directors of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Sleep Research Society . Sleep: a health imperative. Sleep. 2012;35(6):727–734. 10.5665/sleep.1846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Library. Society at a glance 2009-OECD social indicators. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/society-at-a-glance-2009/the-french-spend-longer-periods-sleeping_soc_glance-2009-graph2_5-en. Accessed September 26, 2019.

- 5. Korean national health insurance service (KNHIS) Big data department. Sleepless night: insomniacs, steadily increasing the number of patients. https://www.nhis.or.kr/bbs7/boards/B0039/25795?boardKey=14&sort=sequence&order=desc&rows=10&messageCategoryKey=&pageNumber=1&viewType=generic&targetType=12&targetKey=14&status=&period=&startdt=&enddt=&queryField=T&query=%EB%B6%88%EB%A9%B4%EC%A6%9D. Accessed September 26, 2019.

- 6.Suh L, Sangmu L. Statistics of 100 diseases in daily living. https://www.hira.or.kr/ebooksc/ebook_472/ebook_472_201803281057049800.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2019.

- 7.Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109(2):186–204. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, McGuire L, Robles TF, Glaser R. Emotions, morbidity, and mortality: new perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53(1):83–107. 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross CE. Social Causes of Psychological Distress. Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):370–379. 10.1056/NEJMsa066082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Berntson GG, et al. Do lonely days invade the nights? Potential social modulation of sleep efficiency. Psychol Sci. 2002;13(4):384–387. 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2002.00469.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanson BS, Östergren P-O. Different social network and social support characteristics, nervous problems and insomnia: theoretical and methodological aspects on some results from the population study “men born in 1914”, Malmö, Sweden. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25(7):849–859. 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90043-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Troxel WM, Buysse DJ, Monk TH, Begley A, Hall M. Does social support differentially affect sleep in older adults with versus without insomnia? J Psychosom Res. 2010;69(5):459–466. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao K-W, Yu S, Cheng S-P, Chen I-J. Relationships between personal, depression and social network factors and sleep quality in community-dwelling older adults. J Nurs Res. 2008;16(2):131–139. 10.1097/01.JNR.0000387298.37419.ff [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Platt J, Keyes KM, Koenen KC. Size of the social network versus quality of social support: which is more protective against PTSD? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(8):1279–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bot SD, Mackenbach JD, Nijpels G, Lakerveld J. Association between social network characteristics and lifestyle behaviours in adults at risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0165041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott J. Social network analysis. Sociology. 1988;22:109–127. 10.1177/0038038588022001007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steketee M, Miyaoka A, Spiegelman M. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, NL: Elsevier; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smelser NJ, Baltes PB. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. 1st ed. Amsterdam, NL: Elselvier; 2001.

- 20.Ashida S, Heaney CA. Differential associations of social support and social connectedness with structural features of social networks and the health status of older adults. J. Aging Health. 2008;20(7):872–893. 10.1177/0898264308324626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jamali M, Abolhassani H. Different aspects of social network analysis. Presented at: 2006 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence (WI 2006 Main Conference Proceedings); December 18–22, 2006; Hong Kong, China. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heaney CA, Israel BA. Social networks and social support. Health Behav Health Educ 2008;4:189-210.

- 23.Hill RA, Dunbar RI. Social network size in humans. Hum Nat. 2003;14(1):53–72. 10.1007/s12110-003-1016-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baek J, Hur NW, Kim HC, Youm Y. Sex-specific effects of social networks on the prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension among older Korean adults. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2016;13(7):580–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shye D, Mullooly JP, Freeborn DK, Pope CR. Gender differences in the relationship between social network support and mortality: a longitudinal study of an elderly cohort. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(7):935–947. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00404-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6(2):97–111. 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KA, Kryger MH. Women and sleep. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(7):1189–1190. 10.1089/jwh.2007.0574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Renshaw JR. Korean Women Managers and Corporate Culture: Challenging Tradition, Choosing Empowerment, Creating Change. Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge; 2012. 10.4324/9780203814314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HO, Hoppe-Graff S. Mothers roles in traditional and modern Korean families: the consequences for parental practices and adolescent socialization. Asia Pac Educ Rev. 2001;2:85–93. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Korean Gallup Report. The living hours of the Korean life: wake up/go to bed/sleep time (2013). http://www.gallup.co.kr/gallupdb/reportContent.asp?seqNo=516. Accessed October 30, 2019.

- 31.Shim JS, Song BM, Lee JH, et al. Cohort profile: the Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases Etiology Research Center Cohort in Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2019;60(8):804–810. 10.3349/ymj.2019.60.8.804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vuoksimaa E, Rinne JO, Lindgren N, Heikkilä K, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J. Middle age self-report risk score predicts cognitive functioning and dementia in 20-40 years. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2016;4:118–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seo MH, Lee WY, Kim SS, et al.; Committee of Clinical Practice Guidelines, Korean Society for the Study of Obesity (KSSO) . 2018 Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Guideline for the Management of Obesity in Korea. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2019;28(1):40–45. 10.7570/jomes.2019.28.1.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smarr KL, Keefer AL. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(Suppl 11):S454–S466. 10.1002/acr.20556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(7):485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Youm Y, Laumann EO, Ferraro KF, et al. Social network properties and self-rated health in later life: comparisons from the Korean Social Life, Health, and Aging Project and the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14(1):102. 10.1186/1471-2318-14-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell KE, Lee BA. Name generators in surveys of personal networks. Soc Networks. 1991;13(3):203–221. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burt RS. Network items and the general social survey. Soc Networks. 1984;6:293–339. 10.1016/0378-8733(84)90007-8 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzman R. The National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project: an introduction. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(Suppl 1):i5–i11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim S, Kim J, Moon Y, Shin S. Korean General Social Survey Seoul, Korea: Sungkyunkwan University Press; 2012.

- 41.Burt RS. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cornwell B. Independence through social networks: bridging potential among older women and men. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66(6):782–794. 10.1093/geronb/gbr111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chien K-L, Chen P-C, Hsu H-C, et al. Habitual sleep duration and insomnia and the risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause death: report from a community-based cohort. Sleep. 2010;33(2):177–184. 10.1093/sleep/33.2.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hublin C, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J. Heritability and mortality risk of insomnia-related symptoms: a genetic epidemiologic study in a population-based twin cohort. Sleep. 2011;34(7):957–964. 10.5665/SLEEP.1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) . Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alexopoulos EC. Introduction to multivariate regression analysis. 2010;14:23. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Yoo W, Mayberry R, Bae S, Singh K, Peter He Q, Lillard JW Jr. A study of effects of multicollinearity in the multivariable analysis. Int J Appl Sci Technol. 2014;4(5):9–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alin A. Multicollinearity. WIREs Comp Stat. 2010;2:370–374. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mansfield ER, Helms BP. Detecting multicollinearity. Am Stat. 1982;36:158–160. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stokes JP. Predicting satisfaction with social support from social network structure. Am J Community Psychol. 1983;11(2):141–152. 10.1007/BF00894363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cobb S. Presidential Address–1976. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom Med. 1976;38(5):300–314. 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morin CM, Rodrigue S, Ivers H. Role of stress, arousal, and coping skills in primary insomnia. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(2):259–267. 10.1097/01.PSY.0000030391.09558.A3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Troxel WM, Robles TF, Hall M, Buysse DJ. Marital quality and the marital bed: examining the covariation between relationship quality and sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11(5):389–404. 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ibarra-Coronado EG, Pantaleón-Martínez AM, Velazquéz-Moctezuma J, et al. The bidirectional relationship between sleep and immunity against infections. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:678164. 10.1155/2015/678164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uchino BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med. 2006;29(4):377–387. 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mistlberger RE, Skene DJ. Social influences on mammalian circadian rhythms: animal and human studies. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2004;79(3):533–556. 10.1017/S1464793103006353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haines VA, Beggs JJ, Hurlbert JS. Contextualizing health outcomes: do effects of network structure differ for women and men? Sex Roles 2008;59:164–175. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kessler RC, McLeod JD, Wethington E. The Costs of Caring: A Perspective on the Relationship Between Sex and Psychological Distress. In: Social Support: Theory, Research and Applications. Sarason IG, Sarason BRBerlin, eds. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1985:491-506. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kessler RC, McLeod JD. Sex differences in vulnerability to undesirable life events. Am Sociol Rev. 1984;49(5):620–631. 10.2307/2095420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458–467. 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cornwell B. Network bridging potential in later life: life-course experiences and social network position. J Aging Health. 2009;21(1):129–154. 10.1177/0898264308328649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim H, Kwak S, Kim J, Youm Y, Chey J. Social network position moderates the relationship between late-life depressive symptoms and memory differently in men and women. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):6142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joo W, Lee CJ, Oh J, et al. The association between social network betweenness and coronary calcium: a baseline study of patients with a high risk of cardiovascular disease. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2018;25(2):131–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sundström G, Fransson E, Malmberg B, Davey A. Loneliness among older Europeans. Eur J Ageing. 2009;6(4):267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007(5, Suppl):S7–S10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hargens TA, Kaleth AS, Edwards ES, Butner KL. Association between sleep disorders, obesity, and exercise: a review. Nat Sci Sleep. 2013;5:27–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Talala KM, Martelin TP, Haukkala AH, Härkänen TT, Prättälä RS. Socio-economic differences in self-reported insomnia and stress in Finland from 1979 to 2002: a population-based repeated cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paine S-J, Gander PH, Harris R, Reid P. Who reports insomnia? Relationships with age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic deprivation. Sleep. 2004;27(6):1163–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen Y-Y, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Acevedo-Garcia D, Lee Y-J. Can social factors explain sex differences in insomnia? Findings from a national survey in Taiwan. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(6):488–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lao XQ, Liu X, Deng H-B, et al. Sleep quality, sleep duration, and the risk of coronary heart disease: a prospective cohort study with 60,586 adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(1):109–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baker FC, Willoughby AR, Sassoon SA, Colrain IM, de Zambotti M. Insomnia in women approaching menopause: beyond perception. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;60:96–104. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ohayon MM, Hong S-C. Prevalence of insomnia and associated factors in South Korea. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(1):593–600. 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00449-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]