Abstract

The effectiveness of interventions targeting children's eating and physical activity behaviors through childcare settings is inconsistent. To enhance public health impact, it is imperative to evaluate fidelity of implementing complex interventions in real-world settings. This study evaluated fidelity and contextual factors influencing implementation of Healthy Me, Healthy We (HMHW). HMHW was an 8-month social marketing campaign delivered through childcare to support children's healthy eating and physical activity. HMHW required two levels of implementation support (research team and childcare providers) and two levels of campaign delivery (childcare providers and parents). Process evaluation was conducted among childcare centers in the intervention group (n=48) of the cluster-randomized control trial. Measures included attendance logs, self-report surveys, observation checklists, field notes, and semi-structured interviews. A 35-item fidelity index was created to assess fidelity of implementation support and campaign delivery. The fidelity with which HMHW was implemented by childcare providers and parents was low (mean 17.4 out of 35) and decreased between childcare providers and parents. Childcare providers had high acceptability of the program and individual components (80 – 93%). Only half of parents felt intervention components were acceptable. Frequently cited barriers to implementation by childcare providers included time constraints, parent engagement, staff turnover, and restrictive policies. The lack of observable effect of HMHW on children's dietary or physical activity behaviors may be due to inadequate implementation at multiple levels. Different or additional strategies are necessary to support implementation of multilevel interventions, particularly when individuals are expected to deliver intervention components and support others in doing so.

Keywords: Early care and education, Program evaluation, Families, Health promotion

Implications.

Practice: Early care and education providers need training, technical assistance, and other novel strategies for supporting family engagement with health promotion efforts at the center and home.

Policy: Health promotion programs in early care and education settings need to include implementation strategies to support program delivery by and interactions among all stakeholders.

Research: Future research should engage all stakeholders in systematic identification and selection of strategies that address prioritized barriers of implementing health promotion programs in childcare and at home and that that support family engagement.

BACKGROUND

Dietary and physical activity behaviors are two of many early life exposures that have lasting influence on children's social, emotional, cognitive, and physical growth and development [1]. Preferences and behaviors established during early childhood track into adolescence and adulthood [2, 3] and affect future risk for chronic disease [4]. Many young children do not meet recommendations for a healthy diet or physical activity [5, 6], leading national and international organizations to prioritize policies to support healthy lifestyle behaviors in the settings in which children live, learn, and play [7, 8].

Almost one-third of children under the age of six in the United States regularly attend early care and education (ECE) centers, with the average child spending about 30 hr per week in care [9]. As such, the ECE setting is recognized for potential widespread public health impact [10]. Research regarding ECE policies, programs, and practices (i.e., innovations) to promote healthy eating and physical activity behaviors is rapidly growing [11]. Innovations often target multiple levels of influence—the child, caregivers, interactions between children and caregivers, ECE environments, and/or overarching policies or regulations—making them quite complex to implement and evaluate. Unfortunately, results for the efficacy or effectiveness of these innovations on children's eating or physical activity behaviors in ECE centers have been mixed [11], which may be the result of the varied consistency and sufficiency with which innovations are implemented in ECE centers [12–14]. Understanding effectiveness and how innovations are implemented is essential for differentiating between ineffective innovations and inadequate implementation [15].

It is increasingly important to distinguish intervention fidelity from implementation fidelity [16], particularly for multilevel, multicomponent innovations that have multiple targets for implementation. Intervention fidelity focuses on the extent and quality with which innovation components were delivered as planned [17]. Implementation fidelity focuses on the extent to which the implementation strategy supporting uptake and use of an innovation was delivered as planned [18, 19]. In short, these measures of fidelity can help distinguish inadequate implementation (Type III error) from an ineffective intervention [20, 21]. Process evaluation provides a rigorous approach to capture and evaluate intervention and implementation fidelity at multiple levels [22–24]. In turn, results can inform decisions and modifications to improve design for future iterations and/or better facilitate implementation of innovations in real-world settings [23].

Healthy Me, Healthy We (HMHW) is a social marketing campaign designed to increase healthy eating and physical activity for 3-4-year-old children attending ECE centers [25]. Campaign components targeted children, parents, classroom teachers, and center directors (i.e., ECE providers). A cluster randomized control trial evaluated the effectiveness of the 8-month campaign and gathered information about intervention and implementation fidelity at the center and home [26]. No significant changes were observed in children's diet quality or minutes of non-sedentary physical activity (primary outcomes) [27]. The focus of this paper is to examine the study's process evaluation data to determine the intervention and implementation fidelity of HMHW at each level (i.e., research team, ECE providers, and parents) and identify factors that may have influenced fidelity.

METHODS

HMHW campaign

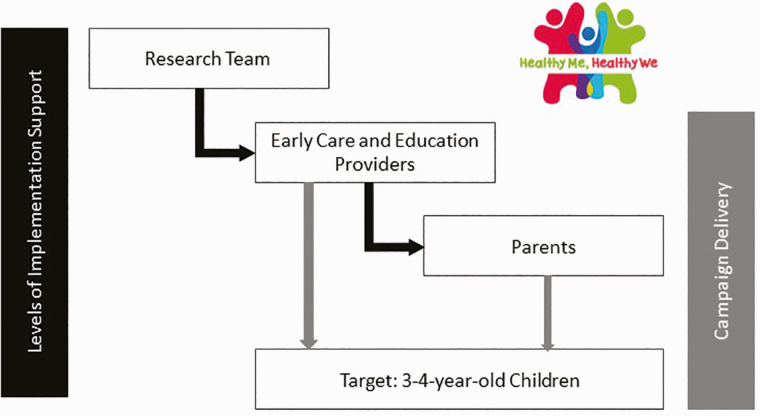

The HMHW campaign was designed to promote partnership between ECE providers and parents to positively influence children's dietary and physical activity behaviors (Fig. 1). Delivered through ECE centers over 8 months, HMHW included components for use in both the classroom (by teachers) and at home (by parents). Components were designed to address behavioral determinants (i.e., knowledge, skills, self-efficacy, barriers, and benefits of changing behaviors) of children's healthy eating and physical activity as well as teachers' and parents' support for these behaviors. The HMHW campaign and its development have been described at length previously [25, 28]. Briefly, ECE centers received a banner to display throughout the year to help introduce and market HMHW. ECE centers were expected to host two events—a kick-off at the beginning of the program and a celebration at the end—bringing together teachers, parents, and children. Centers were able to personalize events, but the goals of each included raising awareness and creating excitement about the program. As part of the kick-off event, classroom teachers were to hang the Healthy We Promise poster and have children and/or families sign it as a commitment to a “just try it” approach to healthy food and activity. The HMHW program included four, 6-week units of branded, educational materials and interactive activities. In the classroom, teachers were to hang the Unit Poster to reinforce unit goals, lead children in at least eight nutrition- or physical activity-themed activities each unit using the Activity Cue Cards, and track the number of activities completed on the Unit Poster. At home, parents were encouraged to support healthy eating and physical activity behaviors using guidance from the Family Guide magazine that introduced unit goals, presented the benefits of healthier behaviors, and provided suggestions for what to do at home to foster healthy habits. Parents were also encouraged to offer eight at-home activities that were built upon classroom activities and to track the number of activities completed on their Activity Tracker. Classroom and home components were repeated during each unit.

Fig 1.

Actors and targets of implementation support for and delivery of Healthy Me, Healthy. Black arrows indicate implementation support provided to early care and education (ECE) providers by the research team and parents by ECE providers. Grey arrows indicate who and where campaign components were delivered to children (i.e., ECE providers at the center and parents at home).

Delivery of the HMHW campaign components required implementation support at two levels (Fig. 1). The research team supported ECE providers (i.e., directors and teachers) in using the center and classroom components of HMHW and getting parents involved. In turn, ECE teachers supported parents in using the home components of HMHW. Specific strategies were selected to support implementation at each level (Table 1) [29, 30]. To support ECE providers, the research team conducted two interactive educational meetings (i.e., a 4-hr introductory training and a 2-hr midpoint training), developed and delivered educational materials (i.e., manual with instructions and resources for delivering center and classroom components), supplied resources boxes (i.e., materials needed to conduct activities described on Activity Cue Cards), and provided centralized technical assistance at three points throughout the intervention (i.e., before the kick-off event and near completion of units 1 and 3) [26]. The research team also reviewed process evaluation data at the end of each unit to identify and address deficits and barriers to implementation that ECE providers experienced. To support parents, ECE providers invited parents to participate in the kick-off and celebration events, delivered educational materials (i.e., distributing Family Guides and Activity Trackers at the start of each unit), and prompted participation at home (i.e., distributing Our Turn cards on days of HMHW classroom activities).

Table 1.

Discrete implementation strategies [30] to support adoption and implementation of Healthy Me, Healthy We (HMHW) among early care and education (ECE) providers and parents of 3–4-year-old children

| Implementation strategy [29] | Action | Target | Temporality and dose | Implementation outcome [21] | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategies for the research team (actors) to use with ECE providers (target) | |||||

| Conduct educational meetings | Study interventionist led in-person meetings to teach ECE providers about HMHW | Trainings conducted to address knowledge shortcomings in children's behaviors and ECE's role to shape healthy habits; review intervention components; build skills to implement HMHW | Baseline training, 3 hr Mid-point training, 2 hr |

Acceptability Adoption Appropriateness Feasibility |

Training improves knowledge, skill, confidence, and change in practices [31] |

| Make training dynamic | Research team incorporated hands-on activities, practice, and discussion in live training sessions | A variety of information delivery methods were used to cater to different learning styles | Baseline training, 3 hr Mid-point training, 2 hr |

Acceptability Adoption Appropriateness Feasibility |

A variety of methods to deliver and have individuals interact with content improves knowledge, skill, confidence, and change in practices [31] |

| Develop and distribute educational materials | Research team developed a resource binder and delivered materials in person | Binder included background information about children's habits, instructions for implementation, copies of activities, communication materials, and space for planning implementation | Before each unit Four units |

Adoption Fidelity to program activities |

Educational materials help individuals learn about and adhere to the delivery of innovations [32] |

| Change physical structure and equipment | Research team provided a resource box (e.g., bean bags, books) for classroom activities | Resources to minimize barriers for teachers to complete classroom activities | Before each unit Four units |

Fidelity | Resources facilitate teaching nutrition and physical activity lessons [33] |

| Centralize technical assistance | Study interventionist provided in-person support for implementation | Help finalize plans for the kick-off event, deliver materials, assess challenges and successes of implementation, answer questions, and offer advice | Prior to kick-off event and near end of Units 1 and 3 45–60 min each |

Appropriateness Feasibility Fidelity |

Commonly used strategy to support ECE providers in day-to-day functions or innovative programs [15, 31] |

| Capture and share local knowledge | Research team facilitated capturing and sharing of implementation success stories | Provide inspirational and informational examples of how ECE centers have worked to overcome barriers and successfully implement HMHW | Baseline and midpoint trainings Technical assistance visits near end of Units 1 and 3 |

Acceptability Appropriateness Feasibility |

Peer support can enhance understanding and implementation of new programs [34] |

| Purposely reexamine the implementation | Research team evaluated process evaluation data | Identify deficits in and barriers to implementation that ECE providers are experiencing and work to remedy | At the end of each unit Four units |

Fidelity | Ongoing process evaluation can identify potential and actual influences and issues with implementation efforts [35] |

| Strategies for ECE providers (actors) to use with parents of 3-4-year-old children (target) | |||||

| Involve parents or other family members | Directors and teachers invite parents to attend or otherwise support (e.g., sending food for tasting events) kick-off, celebration, or other classroom activities | Knowledge about the intervention, sharing child's excitement, and realizing effect of intervention will increase parents' understanding of their role and motivation to implement program at home | During the 8-month intervention period At least twice (for kick-off and celebration events) |

Adoption Fidelity to program activities |

Knowledge and skills for new practices or programs can support buy-in and participation [36] |

| Distribute educational materials | Teachers distribute and explain family guides to parents in person | Parents' knowledge about the program and targeted behaviors. Resources and opportunities for parents to practice targeted behaviors | At the start of each unit Four units |

Adoption Fidelity to program activities |

Family guides were key source of information to guide parents through program participation |

| Remind families | Teachers distribute Our Turn cards to parents in person | Prompt families to do program activities at home | Send home the same day a classroom activity is completed At least 32 times: eight or more times during each of the four units |

Fidelity to program activities | Prompts/cues and reminder systems have been shown to promote adherence and engagement [37] |

Study design

Data for this study were collected as part of the cluster randomized control trial evaluating HMHW compared to a delayed control (Clinical Trials ID: NCT02330354) [26]. A convenience sample of 92 ECE centers (n = 48 intervention group, n = 44 delayed control group) in central North Carolina, representing a mix of rural and suburban counties, were identified through a publicly available database of licensed ECE programs in the state and screened for interest and eligibility [26]. ECE centers were eligible for participation if they had: at least one classroom dedicated to 3–4-year-olds, a quality rating of 3–5 stars (out of 5 stars) or were exempt from quality rating, provided lunch, did not limit service to children with special needs, and had teachers and parents of 3–4-year-olds willing to participate in the evaluation of HMHW.

Study sample

The 48 ECE centers randomized to deliver HMHW represented a variety of programs including, prekindergarten, Head Start, faith-based, and military centers, and on average, enrolled anywhere between 28 and 218 children. Nearly all the ECE centers accepted childcare subsidies (91%) and most participated in the Child and Adult Care Food Program (79%). All adult participants (n = 189 ECE providers, n = 446 parents) signed informed consent for participation; parents consented on behalf of their child. Most adult participants identified as female (98% ECE providers, 85% parents) and either non-Hispanic black (45% ECE providers, 46% parents) or non-Hispanic white (39% ECE providers, 37% parents). About half of the directors (63%) and 39% of teachers reported having a bachelor's or graduate degree. On average directors had worked at the ECE center for 9 years and teachers had worked for 5 years. Parents represented a range of annual household income and educational status, and about half of parents indicated they were either married or had a domestic partnership.

Measures and data collection procedures

Data were collected between August 2015 and June 2017 (across two study waves). Process data were collected during and at the conclusion of the 8-month campaign from ECE centers randomized to the intervention arm. Implementation support provided by the research team and ECE providers, intervention delivery by ECE providers, and parents, as well as factors influencing implementation and intervention fidelity, were measured using self-report surveys, field notes, attendance logs, observation checklists, and semi-structured interviews. The Institutional Review Board approved all study protocols.

Fidelity

Fidelity can be conceptualized and measured in three areas – adherence, competence, and exposure. Adherence measures the extent to which innovation components were delivered as prescribed and competence measures the quality with which components were delivered [38]. Exposure identifies the dose delivered and dose received [39]. A fidelity index was created from process evaluation data to assess the adherence, competence, and exposure with which the research team provided implementation support to ECE providers (implementation fidelity of the research team); ECE providers delivered the HMHW center and classroom components (intervention fidelity of ECE providers); ECE providers provided implementation support to parents (implementation fidelity of ECE providers), and; parents used HMHW home components (intervention fidelity of parents).

In total, the fidelity index included 35 items (Table 2) that combined attendance logs, observation checklists completed by the research team throughout the campaign and surveys from parents at the end of the campaign. Each item was scored either “0” to indicate it did not meet fidelity criteria or “1” to indicate implementation as intended. A single center-level fidelity score was generated. When multiple data points were available for a center (e.g., observations on multiple classrooms, surveys from multiple parents) scores from these multiple data points were averaged to produce center-level fidelity scores (i.e., proportion of classrooms or parents within a center meeting fidelity criteria). Scores for all 35 items were summed to create the fidelity index score, with a maximum score of 35.

Table 2.

Components of fidelity index to measure intervention and implementation fidelity of Healthy Me, Healthy We

| Component | Itema | Data source | Characteristic of fidelity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation fidelity of research team: implementation support provided to early care and education (ECE) providers by research team | |||

| Trainings | Director attended both training sessions | Attendance logs | Exposure |

| Classrooms for which teachers attended both training sessions | Attendance logs | Exposure | |

| Topics missed due to time constraints, ECE providers' engagement in trainingsb | Introductory training field notes |

Adherence | |

| Quality of introductory trainingb | Introductory training surveys | Competence | |

| Topics missed due to time constraints, ECE providers' engagement in trainingsb | Midpoint training field notes |

Adherence | |

| Quality of midpoint trainingb | Midpoint training surveys |

Competence | |

| Educational materials (binder materials, resources boxes, and unit materials) | Unit 1 materials deliveredb | Introductory training checklist | Adherence |

| Unit 2 materials deliveredb | Unit 1 technical assistance checklist | Adherence | |

| Unit 3 materials deliveredb | Midpoint training checklist | Adherence | |

| Unit 4 materials deliveredb | Unit 3 technical assistance checklist | Adherence | |

| Technical assistance | Plans for kick-off eventb | Post-introductory training technical assistance field notes |

Adherence, Competence |

| Challenges and successes ECE providers facedb | Unit 1 technical assistance field notes | Adherence, Competence | |

| Challenges and successes ECE providers facedb | Unit 3 technical assistance field notes | Adherence, Competence | |

| Intervention fidelity of ECE providers: delivery of center and classroom components | |||

| Center banner | Present during first half of the program | Unit 1 observation | Adherence |

| Moderately, very, or extremely visible during first half of the program | Unit 1 observation | Competence | |

| Present during second half of the program | Unit 3 observation | Adherence | |

| Moderately, very, or extremely visible during second half of the program | Unit 3 observation | Competence | |

| Promise poster | Present during first half of program | Unit 1 observation | Adherence |

| Signed during first half of program | Unit 1 observation | Competence | |

| Present during second half of program | Unit 3 observation | Adherence | |

| Signed during second half of program | Unit 3 observation | Competence | |

| Unit postersc | Unit 1 poster present | Unit 1 observation | Adherence |

| Unit 1 poster used to track completed activities | Unit 1 observation | Competence | |

| Unit 3 poster present | Unit 3 observation | Adherence | |

| Unit 3 poster used to track completed activities | Unit 3 observation | Competence | |

| Classroom activitiesc | Completed at least 6 activities for Unit 1d | Unit 1 observation | Adherence |

| Completed at least 6 activities for Unit 3d | Unit 3 observation | Adherence | |

| Implementation fidelity of ECE providers: implementation support provided to parents by ECE providers | |||

| Invitation for parents to participate | Parents aware a kick-off event occurred | Parent survey | Competence |

| Parents aware a celebration event occurred | Parent survey | Competence | |

| Delivery of materials | Parents received Unit 1 Family Guide | Parent survey | Exposure |

| Parents received Unit 2 Family Guide | Parent survey | Exposure | |

| Parents received Unit 3 Family Guide | Parent survey | Exposure | |

| Parents received Unit 4 Family Guide | Parent survey | Exposure | |

| Parents received Unit 1 Activity Tracker | Parent survey | Exposure | |

| Parents received Unit 2 Activity Tracker | Parent survey | Exposure | |

| Parents received Unit 3 Activity Tracker | Parent survey | Exposure | |

| Parents received Unit 4 Activity Tracker | Parent survey | Exposure | |

| Prompts for participation at home | Parents received any Our Turn cards | Parent survey | Adherence |

| Parents received at least 25 Our Turn cards | Parent survey | Exposure | |

| Intervention fidelity of parents: participating in center/classroom or using home components | |||

| Parent participation | Parents attended kick-off event | Parent survey | Adherence |

| Parents attended celebration event | Parent survey | Adherence | |

| Parents understood the program adequately, well, or very well | Parent survey | Competence | |

| Parents understood their role in the program adequately, well, or very well | Parent survey | Competence | |

| Parents read at least half of Family Guidese | Parent survey | Exposure | |

| Parents tried at least 25 activities at homef | Parent survey | Adherence | |

| Parents tried the Just Try It suggestions | Parent survey | Adherence |

a Each item was scored either “0” to indicate it did not meet fidelity criteria or “1” to indicate implementation as intended. Multiple classrooms and parents participated in HMHW at each center, so a single score was created for each item by averaging all responses (i.e., proportion of classrooms or parents within a center meeting fidelity criteria).

b Item not included in the index, and instead summarized, because it could not be linked to a specific center (training surveys), was delivered with 100% fidelity to all centers (delivery of educational materials, resources boxes, and unit materials), or were unable to be consistently converted from qualitative to quantitative indicators of fidelity (field notes).

c No onsite visits were conducted during units 2 and 4.

d Observation visits occurred before the end of a unit, so achieving fidelity for teaching classroom activities was defined as having taught at least six activities (as opposed to the intended eight per unit).

e This was how the survey question was asked. Parents may have interpreted as at least two of four guides or half of each guide.

f The campaign intended to have parents complete activities at home at least 75% of the time classroom activities occurred.

Implementation fidelity of the research team

Several measures were used to document implementation support the research team provided for ECE providers. Attendance logs were used at the introductory and midpoint trainings to track ECE providers' exposure to training. After the introductory and midpoint trainings, ECE providers completed a 13-item survey about the quality of the training (e.g., Adequate time was provided for questions and discussion) and the trainer (e.g., The presenter met all learning objectives) using a 5-point Likert scale (i.e., strongly disagree to strongly agree) to rate agreement with statements. The research team documented delivery of educational materials, resource boxes, and campaign materials for each of the four units. A member of the research team documented field notes after each training and technical assistance visit about training topics missed due to time constraints, ECE providers' engagement in trainings, and common themes expressed by ECE providers about their delivery of HMHW or implementation support to parents. ECE providers' exposure to training was included in the fidelity index. Other measures were not included in the index, and instead summarized, because they could not be linked to a specific center (training surveys), were delivered with 100% fidelity to all centers, and would not have contributed to understanding (delivery of educational materials, resources boxes, and unit materials), or were unable to be consistently converted from qualitative to quantitative indicators of fidelity (field notes).

Intervention fidelity of ECE providers

Items evaluating ECE providers' fidelity to delivering center and classroom components of HMHW (14 items) focused on visibility and use of center and classroom materials and teaching HMHW activities. A single member of the research team (the interventionist) completed observation checklists during two technical assistance visits, near the completion of units 1 and 3, to document visibility and use of intervention materials. Since observations were conducted before the end of a unit, fidelity for teaching classroom activities was defined as having taught at least six, not eight, activities.

Implementation fidelity of ECE providers

Items evaluating the fidelity of implementation support parents received from ECE providers included invitations for involvement with HMHW at the center, exposure to campaign material, and prompts to participate at home. Parents completed a 12-item survey at the end of the intervention regarding receipt of campaign materials.

Intervention fidelity of parents

Parents' fidelity of engaging with HMHW intervention components was evaluated by interaction with events at the center and use of campaign materials at home. Parents completed a 7-item survey at the end of the intervention to report their participation in activities.

Factors influencing fidelity

At the end of the campaign, ECE providers and parents completed surveys about the acceptability of HMHW. Acceptability refers to satisfaction with the content, complexity, or delivery of specific intervention components and can be an important indicator of fidelity [21]. The director survey included 16 items, the teacher survey included 19 items, and the parent survey included 4 items (Table A1). ECE providers rated the acceptability of classroom and home components (e.g., Rate the unit guide posters) using a 3-point scale (i.e., works well as is to need lots of improvement). Parents used a 5-point scale (i.e. strongly disagree to strongly agree) to rate acceptability of home components (e.g., The home activities were easy to do). ECE providers also rated the program (e.g., The Healthy Me, Healthy We program provided useful resources that helped teachers promote healthy eating) using a 5-point scale (i.e., strongly disagree to strongly agree).

Barriers and facilitators of program implementation were formally captured through semi-structured interviews with ECE providers at the end of the campaign. Interviews were conducted by trained research team members to assess overall experiences with HMHW and probe on experiences integrating HMHW into normal classroom activities, challenges with HMHW, and impact of HMHW on communication with parents. Interviews lasted approximately 30 min and were audio-recorded for future transcription and analysis.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, means, and standard deviations, were calculated to evaluate implementation support provided by the research team and report fidelity and acceptability of HMHW. Due to a lack of variation, responses for acceptability outcomes were collapsed to represent general disagreement (strongly disagree or disagree), neutrality (neither agree nor disagree), and agreement (agree or strongly agree) and reported as frequencies. All analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (Cary, North Carolina).

Rapid qualitative analysis methods were used to convert qualitative data from interviews to a quantitative measure [40, 41]. Prior to data transfer from audio file to transcript, a template was created to streamline documentation of interview content. Interview questions guided the development of the coding template to focus on elements related to evaluating barriers and facilitators of implementation. After all, interviews had been transferred to the coding template, data were reduced to an excel document that allowed for analysis about the absence or presence of items of interest across all participants.

RESULTS

Implementation fidelity of the research team

The research team mostly provided implementation support to ECE providers as intended. Each center received the two prescribed trainings from the study interventionist. Trainings were offered in a variety of formats to meet the needs of ECE providers, including Saturday multi-center sessions, evening multi- and individual center sessions, naptime sessions with individual centers, and makeup sessions with one or two individual ECE providers (e.g., in response to staff turnover). ECE providers consistently agreed or strongly agreed that the presenter met all learning objectives at each training (100%), questions were answered accurately and clearly (100%), the information was useful (99%), they understood how HMHW was designed to work (98%), and that they felt confident to implement specific practices and elements of HMHW (97%–99%). The interventionist noted that the prescribed content and activities of trainings were generally delivered, and participants had high levels of engagement with content and activities. However, group dynamics sometimes caused some content or activities to run longer, which in turn resulted in having to either skip or condense certain activities (e.g., planning for the events [9%], practice pitching the program to parents [9%], rehearsing classroom activities [10%], planning the next unit of activities [14%]). All binder materials, resource boxes, and unit materials for use at the center and home were delivered. All centers received the three planned technical assistance visits.

Fidelity of ECE providers and parents

The fidelity with which the HMHW program was implemented by ECE providers and parents was low (Table 3). The mean total score, 17.4 on a scale of 35, represents fidelity at ~50% of what was intended, and only one center had a score that represented fidelity of 80%. Although overall fidelity was low, upon further inspection of the sub-scales contributing to the total score, it was evident fidelity decreased when implementation support transitioned from the research team to ECE provider, which in turn impacted intervention delivery by parents. Sub-scale scores were closest to the maximum (8.9 out of 14) for ECE providers delivering center and classroom components. Most ECE providers met targets for teaching activities, but teachers were less consistent in displaying and/or tracking activities on posters (mean 2.4 out of 4). However, subscale scores were lowest for ECE providers providing implementation support to parents (4 out of 12). Scores indicate many parents did not recall whether the center had kick-off or celebration events (mean 0.5 out of 2). Also, many parents did not recall receiving the Family Guides or Activity Trackers (mean 3.1 out of 8) or Our Turn Card prompts to do activities at home (mean 0.4 out of 2). Finally, sub-scale scores for parents' delivery of HMHW home components clearly showed that parents largely did not implement the home component of the program (mean 2.7 out of 7).

Table 3.

Fidelity to implementation of Healthy Me, Healthy We by early care and education providers and parents (n = 48 ECE centers)

| Component | Mean ± SD | Median | Range | Maximum possible |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation fidelity of research team: implementation support provided to early care and education (ECE) providers by research team | ||||

| Training | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 2.0 | 0.5–2 | 2 |

| Intervention fidelity of ECE providers: delivery of center and classroom components | ||||

| Center banner | 2.3 ± 1.8 | 2.5 | 0–4 | 4 |

| Promise poster | 2.6 ± 1.3 | 3.0 | 0–4 | 4 |

| Unit posters | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 2.8 | 0–4 | 4 |

| Classroom activities | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 2.0 | 0.3–2 | 2 |

| Total sub-score | 8.9 ± 3.3 | 9.2 | 1–14 | 14 |

| Implementation fidelity of ECE providers: implementation support provided to parents by ECE providers | ||||

| Invitation for parent participation | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 0.5 | 0–1.8 | 2 |

| Delivery of materials | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 3.1 | 0.3–7.5 | 8 |

| Prompts for participation | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 0.3 | 0–1.1 | 2 |

| Total sub-score | 4.0 ± 2.0 | 4.1 | 0.7–10.4 | 12 |

| Intervention fidelity of parents: participating in center/classroom or using home components | ||||

| Parent participation | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 2.7 | 1.8 – 4.8 | 7 |

| Total fidelity score | 17.4 ± 4.5 | 17.1 | 8.4–29.6 | 35 |

Factors influencing implementation

At the end of the intervention, ECE providers generally reported a positive experience (88%) with implementing HMHW at their center but only 50% of ECE providers indicated a positive experience in communicating with parents about the program. Despite competing priorities for class time, teachers felt the HMHW program helped them find time to promote healthy eating (83%) and active play (81%). ECE providers thought events and materials for use in the classroom were suitable for use as designed (86%–93%). However, ECE providers and parents disagreed on the usefulness of materials designed for use at home. ECE providers reported that they were suitable as designed (80%–93%); however, only half of the parents (53%) felt the information in the Family Guides was useful or that activities were easy to do. Many ECE providers (71%) thought the Our Turn cards, the intended prompt for parents to participate at home, worked well as designed, whereas only 30% of parents felt the Our Turn cards helped them remember to do activities at home.

The most frequently cited barriers to implementing HMHW by ECE providers included lack of time due to demands of ECE curriculum (30%), lack of parent engagement (29%), staffing issues like turnover or rotating staff unfamiliar with the program (11%), and center policies negatively influencing implementation (10%) (e.g., restrictions on the use of outside food limited tasting activities, computer access, or wall hangings). Facilitators of implementing HMHW by ECE providers were less frequently identified. Although more frequently viewed as barriers, 8% of ECE providers thought ECE curriculum supported implementation of HMHW because activities integrated with existing requirements, and 4% of ECE providers felt center policies supported implementation (e.g., home visits part of Head Start and communication through apps).

DISCUSSION

A comprehensive assessment of process evaluation data suggests the lack of effect on children's diet quality or minutes of non-sedentary physical activity in the cluster-randomized trial of HMHW may be a result of inadequate implementation at multiple levels of the program. The research team adhered to the prescribed implementation strategies. However, fidelity decreased with each subsequent level of implementation support and intervention delivery. ECE providers and parents expressed differing views regarding acceptability of HMHW. ECE providers had tremendously positive comments about the program, particularly components used in the classroom, but they were less positive about their experiences communicating with parents about the program. Only half of the parents felt components for the home were useful. Frequently cited barriers to implementation by ECE providers included time constraints related to curriculum, parent engagement, staff turnover, and restrictive center-level policies.

Achieving effectiveness in ECE center-based interventions is complicated by difficulties ECE providers have implementing interventions with high fidelity in these real-world settings [12]. Training and technical assistance are commonly employed implementation strategies to support ECE providers in day-to-day functions or innovative programs [15, 31]. While it is possible training and technical assistance for HMHW was adequate for a new program that integrates well with classroom structure and builds content (e.g., nutrition) upon existing skills (e.g., teaching) and learning standards, it is possible training did not adequately prepare ECE providers to engage parents around health promotion. Other studies have similarly identified concerns or barriers for communication with parents about health promotion topics [42, 43]. Of additional consideration, measures of fidelity of implementation support focused on adherence (i.e., was it done) and exposure (i.e., dose) and less on competence (i.e., how well was it done). Potentially undocumented differences in how training and technical assistance were conducted could have impacted the quality with which the content was delivered or received. Tailored approaches of technical assistance, and rigorous evaluation of such efforts, may help identify and specify processes through which context-specific barriers and facilitators are addressed [44, 45].

The low levels of fidelity observed among ECE providers providing implementation support and parents delivering home components suggest greater emphasis needs to be placed on selection and adaptation of implementation strategies for each level of multilevel interventions [46, 47]. This includes selecting and clearly describing implementation strategies that address barriers and facilitators of all stakeholders at each level of implementation [30, 48]. The intervention design process of HMHW, like many other health behavior programs in ECE [49], applied a systematic, multi-step method that incorporated stakeholder perspectives and theoretical and empirical evidence to build a program and implementation plan [25]. There is a need for similar systematic methods to plan and evaluate implementations strategies that support use of interventions in real-world settings [45, 50, 51]. Future efforts should consider differing packages of implementation strategies for each level and phase of program implementation (e.g., adoption, implementation, sustainability) [52, 53]. Incorporating ongoing assessment of fidelity at all levels of intervention and implementation support could enable monitoring and feedback about implementation efforts that capture adaptations and proactively identify ways to improve implementation of the program [54, 55]. Real-time monitoring in conjunction with ongoing exploration to how ECE providers and parents successfully integrate innovations with existing routines, practices, and/or organizational structures is necessary to achieve or sustain shared promotion and reinforcement of the intervention across multiple levels [52].

Similar to other studies [56], notable barriers to program implementation included curriculum/time demands, staffing issues, and policies. To increase the likelihood of sustained use of HMHW or similar programs, readiness, and capacity for implementation need to be evaluated and addressed; efforts to develop and adopt such measures are underway [57, 58]. Involving parents in health promotion efforts in ECE settings is an effective strategy for supporting improvements in dietary and physical activity behaviors [59]. However, ECE providers in this study, and others, frequently comment that parent engagement is a barrier [56, 60–62]. Interestingly, parent perception of implementation support from ECE providers instead suggests either ECE providers did not offer prescribed support as frequently as intended and/or the selected implementation strategies were not adequate or appropriate for supporting parents to get involved with HMHW. For example, the Our Turn card was intended to serve as the primary prompt for parents to complete activities at home. A majority of ECE providers thought the cards functioned well but many parents did not recall receiving them or did not think the card served as an adequate reminder to participate, thus highlighting a missed opportunity that needs modifying to support parents in adopting or implementing future iterations of HMHW. More research is needed that includes input from both ECE providers and parents to better understand this disconnect, and different strategies will be needed to facilitate interactions between ECE providers and parents around healthy eating and physical activity.

A key strength of this study was our evaluation of the implementation process during this early phase of research. The examination of the implementation process and context helped clarify results from the effectiveness trial and has provided an opportunity for others to learn from this experience of implementing a complex, multi-component program in a real-world setting [22, 23]. Another strength was the measure of fidelity at multiple levels of implementation [63]. Evaluations of other multilevel health promotion innovations in ECE often focus less on implementation support at subsequent levels of intervention [64, 65]. This critical evaluation of fidelity of both intervention components and implementation support by ECE providers highlights the importance of evaluating fidelity at all levels of intervention.

However, this study is not without limitations. Implementation is complex and should be evaluated as such. Fidelity was measured at the level of the center, but implementation was initiated within classrooms. Teachers and families within classrooms may have had different experiences within the same center, but process evaluation data were not able to be linked in this manner. While this study included a lot of process measures, having more objective measures of the implementation support delivered by the research team (i.e., during training and technical assistance) as well as more systematic documentation of adaptations in the program's delivery could have provided detailed insight to how ECE providers and parents approached participation in the program. In addition, it could have been particularly insightful to have had interviews with parents at completion of the program to ask similar questions about their experience with the program.

CONCLUSIONS

To elevate public health impact of health promotion in ECE settings, it is imperative to evaluate whether or to what degree an innovation was implemented as intended and the surrounding context within which change did or did not occur. Results suggest that inadequate implementation at multiple levels of the program contributed to nonsignificant change in children's diet quality or minutes of non-sedentary physical activity. The overall low fidelity of implementation and decreasing fidelity at subsequent levels of intervention observed in this study could have greater implications for understanding the lack of effect often seen for other health promotion innovations in ECE and similar community-based settings. Findings demonstrate a need for different or additional strategies that support implementation of multilevel interventions, particularly within the context of the ECE setting. This includes responsive selection of strategies that not only address prioritized barriers but that also correspond with existing routines and structures. This has important implications for future selection and design of appropriate implementation strategies, and more emphasis should be placed on ensuring ECE providers are not only adequately prepared to deliver a new innovation in the center but to also provide implementation support to families so that they can be active participants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the childcare centers and families who participated in the Healthy Me, Healthy We study and the project staff who supported participant recruitment, data collection, and data management.

Funding Sources

This study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [R01HL120969]. Support was also received from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention [U48DP005017].

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

Authors CTL, AEV, RB, HHK, DH, and DSW declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human Rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (13–2379).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Welfare of Animals

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Transparency statements

Study registration. The study was pre-registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02330354)

Analytic plan pre-registration. The analysis plan was not formally pre-registered.

Data availability. De-identified data from this study are not available in a public archive. De-identified data from this study will be made available (as allowable according to institutional IRB standards) by emailing the corresponding author.

Analytic code availability. Analytic code used to conduct the analyses presented in this study are not available in a public archive. It may be made available by emailing the corresponding author.

Materials availability. Materials used to conduct the study are not publicly available. They may be made available by emailing the corresponding author.

References

- 1. National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Connecting the brain to the rest of the body: Early childhood development and lifelong health are deeply intertwined: Working paper No. 15. www.developingchild.harvard.edu. 2020.

- 2. Birch LL, Fisher JO. Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3 Pt 2):539–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Telama R. Tracking of physical activity from childhood to adulthood: A review. Obes Facts. 2009;2(3):187–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weihrauch-Blüher S, Schwarz P, Klusmann JH. Childhood obesity: Increased risk for cardiometabolic disease and cancer in adulthood. Metabolism. 2019;92:147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beets MW, Bornstein D, Dowda M, Pate RR. Compliance with national guidelines for physical activity in U.S. preschoolers: Measurement and interpretation. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):658–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fox MK, Gearan E, Cannon J, Briefel R, Deming DM, Eldridge AL, Reidy KC. Usual food intakes of 2- and 3-year old U.S. children are not consistent with dietary guidelines. BMC Nutrition. 2016;2(1):67. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Institute of Medicine (IOM). Early Childhood Obesity Prevention Policies. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization (WHO). Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Document Production Services; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Corcoran L, Steinley K, Grady S. Early childhood program participation, results from the National Household Education Surveys Program of 2016. 2016https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2017/2017101REV.pdf

- 10. Larson N, Ward DS, Neelon SB, Story M. (2011). What role can child-care settings play in obesity prevention? A review of the evidence and call for research efforts. J Am Diet Ass. 111(9):1343–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sisson SB, Krampe M, Anundson K, Castle S. Obesity prevention and obesogenic behavior interventions in child care: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2016;87:57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Finch M, Jones J, Yoong S, Wiggers J, Wolfenden L. Effectiveness of centre-based childcare interventions in increasing child physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis for policymakers and practitioners. Obes Rev. 2016;17(5):412–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nanney MS, LaRowe TL, Davey C, Frost N, Arcan C, O'Meara J. Obesity prevention in early child care settings. Health Educ Behav. 2017;44(1):23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu ST, Graffagino CL, Leser KA, Trombetta AL, Pirie PL. Obesity prevention practices and policies in child care settings enrolled and not enrolled in the child and adult care food program. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(9):1933–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wolfenden L, Barnes C, Jones J, et al. Strategies to improve the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes within childcare services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;2:CD011779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. ; StaRI Group . Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement. BMJ. 2017;356:i6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Linnan L, Steckler A.. Process Evaluation and Public Health Interventions and Research: An Overview. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci. 2007;2:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pérez D, Van der Stuyft P, Zabala MC, Castro M, Lefèvre P. A modified theoretical framework to assess implementation fidelity of adaptive public health interventions. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dobson D, Cook TJ. Avoiding type III error in program evaluation: Results from a field experiment. Evaluation and Program Planning, 1980;3(4):269–276. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peters DH, Adam T, Alonge O, Agyepong IA, Tran N. Implementation research: What it is and how to do it. BMJ. 2013;347:f6753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klesges LM, Estabrooks PA, Dzewaltowski DA, Bull SS, Glasgow RE. Beginning with the application in mind: Designing and planning health behavior change interventions to enhance dissemination. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29 Suppl:66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vaughn AE, Bartlett R, Luecking CT, Hennink-Kaminski H, Ward DS. Using a social marketing approach to develop Healthy Me, Healthy We: A nutrition and physical activity intervention in early care and education. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(4):669–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hennink-Kaminski H, Vaughn AE, Hales D, Moore RH, Luecking CT, Ward DS. Parent and child care provider partnerships: Protocol for the Healthy Me, Healthy We (HMHW) cluster randomized control trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;64:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vaughn AE, Hennink-Kaminski H, Moore RH, et al. Evaluating a child care-based social marketing approach for improving children's diet and physical activity: Results from the Healthy Me, Healthy We cluster-randomized controlled trial. Trans Behav Med. 2021;11(3):775–784. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibaa113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hennink-Kaminski H, Ihekweazu C, Vaughn AE, Ward DS. Using formative research to develop the Healthy Me, Healthy We campaign. Soc Marketing Q. 2018;24(3):194–215. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: Recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. DeCorby-Watson K, Mensah G, Bergeron K, Abdi S, Rempel B, Manson H. Effectiveness of capacity building interventions relevant to public health practice: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cross WF, West JC. Examining implementer fidelity: Conceptualizing and measuring adherence and competence. J Child Serv. 2011;6(1):18–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hesketh KR, Lakshman R, van Sluijs EMF. Barriers and facilitators to young children's physical activity and sedentary behaviour: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative literature. Obes Rev. 2017;18(9):987–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gingiss PL. Peer coaching: Building collegial support for using innovative health programs. J Sch Health. 1993;63(2):79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stetler CB, Legro MW, Wallace CM, et al. The role of formative evaluation in implementation research and the QUERI experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 2):S1–S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gadsden VL, Ford M, Breiner H,eds. Parenting Matters. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Srbely V, Janjua I, Buchholz A, Newton G, Newton G. Interventions aimed at increasing dairy and/or calcium consumption of preschool-aged children: A systematic literature review. Nutrients. 2019;11(4):714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Breitenstein SM, Gross D, Garvey CA, Hill C, Fogg L, Resnick B. Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(2):164–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dane AV, Schneider BH. Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: Are implementation effects out of control? Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18(1):23–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Watkins DC. 2017. Rapid and rigorous qualitative data analysis: The “RADaR” technique for applied research. Int J Qual Methods. 16(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Taylor B, Henshall C, Kenyon S, Litchfield I, Greenfield S. Can rapid approaches to qualitative analysis deliver timely, valid findings to clinical leaders? A mixed methods study comparing rapid and thematic analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e019993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dev DA, Byrd-Williams C, Ramsay S, et al. Engaging parents to promote children's nutrition and health. Am J Health Promot. 2017;31(2):153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Johnson SL, Ramsay S, Shultz JA, Branen LJ, Fletcher JW. Creating potential for common ground and communication between early childhood program staff and parents about young children's eating. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(6):558–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chiappone A, Smith TM, Estabrooks PA, Rasmussen CG, Blaser C, Yaroch AL. Technical assistance and changes in nutrition and physical activity practices in the National Early Care and Education Learning Collaboratives Project, 2015–2016. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2018;15(4):170239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, et al. Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2017;44(2):177–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Weiner BJ, Lewis MA, Clauser SB, Stitzenberg KB. In search of synergy: Strategies for combining interventions at multiple levels. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012(44):34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(1):4–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Leeman J, Birken SA, Powell BJ, Rohweder C, Shea CM. Beyond “implementation strategies”: Classifying the full range of strategies used in implementation science and practice. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Luecking CT, Hennink-Kaminski H, Ihekweazu C, Vaughn A, Mazzucca S, Ward DS. Social marketing approaches to nutrition and physical activity interventions in early care and education centres: A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2017;18(12):1425–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernández ME, Abadie B, Damschroder LJ. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: Diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fernandez ME, Ten Hoor GA, van Lieshout S, et al. Implementation mapping: Using intervention mapping to develop implementation strategies. Front Public Health. 2019;7(JUN):158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gittelsohn J, Novotny R, Trude A, Butel J, Mikkelsen B. Challenges and lessons learned from multi-level multi-component interventions to prevent and reduce childhood obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;16(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Huynh AK, Hamilton AB, Farmer MM, et al. A pragmatic approach to guide implementation evaluation research: Strategy mapping for complex interventions. Front Public Health. 2018;6:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Butel J, Braun KL, Novotny R, et al. Assessing intervention fidelity in a multi-level, multi-component, multi-site program: The Children's Healthy Living (CHL) program. Transl Behav Med. 2015;5(4):460–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Martinez-Beck I. Where is the new frontier of implementation science in early care and education? In: Halle T, Metz A, Martinez-Beck I, eds. Applying Implementation Science in Early Childhood Programs and Systems. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ward S, Chow AF, Humbert ML, et al. Promoting physical activity, healthy eating and gross motor skills development among preschoolers attending childcare centers: Process evaluation of the Healthy Start-Départ Santé intervention using the RE-AIM framework. Eval Program Plann. 2018;68:90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Halle T, Partika A, Nagle K.. Measuring readiness for change in early care and education. OPRE Report #201963, Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vaughn AE, Studts CR, Powell BJ, et al. The impact of basic vs. enhanced Go NAPSACC on child care centers' healthy eating and physical activity practices: Protocol for a type 3 hybrid effectiveness-implementation cluster-randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ward DS, Welker E, Choate A, et al. Strength of obesity prevention interventions in early care and education settings: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2017;95(Suppl):S37–S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chow AF, Humbert L. Physical activity and nutrition in early years care centres: Barriers and facilitators. J Child Stud. 2011;36(1):26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lyn R, Evers S, Davis J, Maalouf J, Griffin M. Barriers and supports to implementing a nutrition and physical activity intervention in child care: Directors' perspectives. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(3):171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Needham L, Dwyer JJ, Randall-Simpson J, Heeney ES. Supporting healthy eating among preschoolers: Challenges for child care staff. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2007;68(2):107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Stevens J, Pratt C, Boyington J, et al. Multilevel interventions targeting obesity: Research recommendations for vulnerable populations. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(1):115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wolfenden L, Jones J, Williams CM, et al. Strategies to improve the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes within childcare services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD011779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Paulsell D, Austin AMB, Lokteff M.. Measuring Implementation of Early Childhood Interventions at Multiple System Levels (OPRE Research Brief OPRE 2013–16). Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.