Abstract

Fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) is an RNA-binding protein that regulates the translation of numerous mRNAs in neurons. The precise mechanism of translational regulation by FMRP is unknown. Some studies have indicated that FMRP inhibits the initiation step of translation, whereas other studies have indicated that the elongation step of translation is inhibited by FMRP. To determine whether FMRP inhibits the initiation or the elongation step of protein synthesis, we investigated m7G-cap-dependent and IRES-driven, cap-independent translation of several reporter mRNAs in vitro. Our results show that FMRP inhibits both m7G-cap-dependent and cap-independent translation to similar degrees, indicating that the elongation step of translation is inhibited by FMRP. Additionally, we dissected the RNA-binding domains of hFMRP to determine the essential domains for inhibiting translation. We show that the RGG domain, together with the C-terminal domain (CTD), is sufficient to inhibit translation while the KH domains do not inhibit mRNA translation. However, the region between the RGG domain and the KH2 domain may contribute as NT-hFMRP shows more potent inhibition than the RGG-CTD tail alone. Interestingly, we see a correlation between ribosome binding and translation inhibition, suggesting the RGG-CTD tail of hFMRP may anchor FMRP to the ribosome during translation inhibition.

Introduction

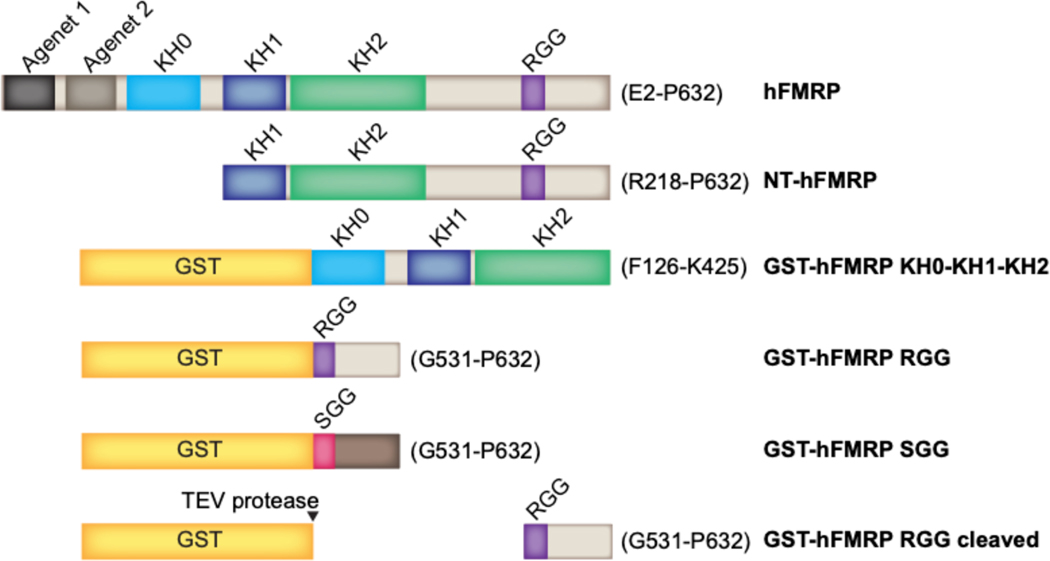

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is the most common form of inherited intellectual disability and is caused by the reduced expression of the fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) gene in neurons 1. The expression of the FMR1 gene is reduced because of the expansion of the CGG trinucleotide repeats in the 5’-untranslated region of the gene, which results in abnormal methylation of the gene and the repression of transcription 2–5. FMR1 encodes an RNA binding protein, fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), that is highly expressed in the brain 6–10. FMRP has four RNA-binding domains: one RGG domain that is rich in arginines and glycines and three hnRNP K-homology domains (KH0, KH1, and KH2) (Figure 1) 6,7,11. FMRP is thought to regulate the translation of about 4% of the human fetal brain mRNAs by directly binding to specific sequences or structures in the target mRNAs 12. Additionally, the majority of FMRP in the cell is associated with polyribosomes, consistent with its proposed role in regulating protein synthesis 13. Interestingly, missense mutations in the KH1 and KH2 domains (Gly266Glu and Ile304Asn, respectively, of human FMRP) abolishes the binding of FMRP to polyribosomes and cause FXS in humans 14,15. These results suggest that the RNA-binding activity of FMRP is critical for the healthy development and function of the brain.

Figure 1.

Human FMRP constructs. hFMRP is the full-length human FMRP isoform 1, spanning amino acids E2-P632, alongside the truncation constructs that were used. GST-hFMRP SGG is a fusion between the glutathione S-transferase and the RGG motif-containing sequence of hFMRP spanning amino acids G531-P632 where the 16 arginines spanning the RGG motif to the C-terminus were mutated to serines, illustrated using a different color for the C-terminus. Amino acids of hFMRP found within each construct are denoted to the right of the respective construct in parentheses.

Several studies have focused their efforts on trying to identify the mRNA targets of FMRP. Although thousands of mRNA targets have been identified over the years, there is minimal overlap among the mRNA targets from individual studies 12,13,16–19. These results suggest that it is difficult to discern the authentic mRNA targets of FMRP. Interestingly, in vitro selection experiments identified a G-quadruplex (GQ) structure and a pseudoknot structure as the potential RNA ligands for the RGG and KH2 domains, respectively 12,20–22. Based on these results, it was proposed that FMRP may bind to mRNAs that possess GQ or pseudoknot forming sequences to repress their translation 12,20,22,23. We previously showed that the KH domains of FMRP do not bind to simple four or five nucleotide RNA sequence motifs compared to the canonical KH domains found in other RNA-binding proteins 24–29. It is possible that the KH domains of FMRP bind to pseudoknot structures in the mRNAs; however, such structures are not common in mRNAs and do not agree with the fact that FMRP appears to interact with thousands of mRNAs. In contrast, the RGG domain of FMRP binds to GQ structures with high affinity, and potential GQ structures are prevalent in mRNAs 24,30–36. Interestingly, GQ structures are even present in the 28S and 18S rRNA expansion segments 37,38. Therefore, possibly the RGG domain of FMRP interacts with GQ structures in the mRNA target or in the rRNAs to regulate translation.

The mechanism(s) by which FMRP regulates translation, however, is still unknown. One theory is that FMRP hinders translation initiation by binding to the target mRNA and recruiting the cytoplasmic FMRP-interacting protein (CYFIP1), which then binds the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) at the mRNA 5’ 7-methylguanosine (m7G) cap. Binding of CYFIP1 to eIF4E, in turn, prevents binding of eukaryotic initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) to eIF4E, and the eukaryotic initiation factor 4F (eIF4F) complex is prevented from assembling at the m7G cap 39. However, most of the cytoplasmic FMRP has been found associated with stalled polyribosomes 13,40. Additionally, FMRP has been shown to interact with the ribosome even after translation initiation is blocked 41. These results suggest that FMRP inhibits translation by binding to the target mRNA and stalling the ribosome during the translational elongation step.

Consistent with the idea that FMRP inhibits the elongation step, a cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the Drosophila FMRP (dFMRP) bound to the Drosophila 80S ribosome showed that FMRP binds to a site within the ribosome that would prevent binding of tRNA and translation factors 42. Additionally, the FMRP-ribosome structure revealed that the KH1 and KH2 domains bind near the ribosome’s peptidyl site, and the RGG domain of FMRP residing near the aminoacyl site, presumably available for binding target mRNA motifs. Thus, FMRP may tether itself to the ribosome and the mRNA via its KH and RGG domains, respectively, to stall the ribosome during the elongation step of translation 12,13,20,21,42,43.

FMRP is also suggested to repress translation via RNA interference (RNAi). FMRP has been shown to associate with the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) proteins Dicer and Argonaute 2 (Ago2) as well as specific microRNAs (miRNAs) 44–46. In fact, FMRP has been reported to assemble the Ago2 and miRNA-125a inhibitory complex on the postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95) mRNA through phosphorylation of FMRP 47,48. The PSD-95 RNAi case may be just one of many RNAi translation repression pathways FMRP employs. It is possible that FMRP can recruit from a catalog of miRNA complexes to inhibit a variety of mRNAs via RNAi.

FMRP may use multiple mechanisms to specifically repress an extensive catalog of target mRNAs under different conditions within the cell. To study the mechanism of translational inhibition by FMRP, we analyzed the translation of 5’-m7G-capped mRNAs and uncapped mRNAs initiated using different IRES structures. Our studies show that FMRP reduces both m7G-cap-dependent and the cricket paralysis virus (CrPV) IRES-driven translation to a similar extent demonstrating that FMRP inhibits the elongation step of translation. Furthermore, we show that the RGG domain, together with the C-terminal domain (CTD), is sufficient to inhibit translation, whereas the KH domains do not inhibit mRNA translation. Interestingly, the RGG-CTD tail of FMRP binds to the ribosome suggesting that translation inhibition may depend on the interaction of FMRP with potential GQ structures in the rRNAs.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

The human FMR1 isoform 1 gene was assembled from E. coli codon-optimized gene blocks (IDT). The gene encoding the full-length isoform 1 human FMRP (hFMRP) spanning residues E2-P632 was subcloned into the LIC expression vector pMCSG7 (DNASU plasmid repository) with the 5’ TEV cleavage site deleted, conferring a N-terminal hexahistidine tag. The N-terminus truncated human FMRP (NT-hFMRP) spanning residues R218-P632 was subcloned into the LIC expression vector pMCSG7, conferring a N-terminal hexahistidine tag with the 5’ TEV cleavage site deleted. The human FMRP RGG domain (GST-hFMRP RGG) spanning residues G531-P632 was subcloned into the LIC expression vector pMCSG10 (DNASU) which confers a N-terminal hexahistidine-GST fusion tag that is cleavable using TEV protease. The mutant SGG domain (GST-hFMRP SGG) was assembled from an E. coli codon-optimized gene block where all 16 arginine residues of the RGG region were mutated to serines. The resulting SGG fragment was subcloned into the LIC expression vector pMCSG10. The human FMRP tandem KH0-KH1-KH2 domains (GST-hFMRP KH0-KH1-KH2) spanning residues F126-K425 was also subcloned into the LIC expression vector pMCSG10.

The NT-hFMRP, GST-hFMRP RGG, GST-hFMRP SGG, and GST-hFMRP KH0-KH1-KH2 expression plasmids were all transformed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells (Novagen). NT-hFMRP was purified using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (Qiagen). GST-hFMRP RGG, GST-hFMRP SGG, and GST-hFMRP KH0-KH1-KH2 were purified using glutathione affinity chromatography (GE Healthcare). All proteins were further purified using Superdex 75 16/60 or Superdex 200 16/60 (GE Healthcare) gel filtration chromatography and stored in their respective running buffers. Gel filtration buffer composition varied between FMRP constructs. NT-hFMRP gel filtration running buffer contained 25 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl and 1 mM DTT. GST-hFMRP RGG and GST-hFMRP SGG were purified in gel filtration running buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 and 1 mM DTT. GST-hFMRP KH0-KH1-KH2 was purified in gel filtration running buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT.

Preparation of reporter mRNAs

The gene encoding the Renilla luciferase (RLuc) protein was modified with an poly(A)25 insertion at the 3’ end of the gene within the pRL-null vector (Promega). The gene encoding the NanoLuc luciferase was transferred from the pNL1.1 vector (Promega) into the pRL-null vector using 5’ NheI and 3’ XbaI restriction enzymes, then a poly(A)25 was inserted at the 3’ end of the NanoLuc gene. This generated RLuc and NanoLuc mRNAs with uniform 3’ poly(A)25 tails to bypass the need for post-transcriptional 3’ polyadenylation. The PV IRES-, EMCV IRES-, HCV IRES-, and CrPV IRES-driven RLuc genes were subcloned into the EMCV-TurboGFP parental vector pT7CFE1 (ThermoFisher Scientific) in two steps. In the first step, the TurboGFP gene was replaced with the RLuc gene using 5’ NdeI and 3’ XhoI restriction enzymes to generate the EMCV-RLuc plasmid. In the second step, the EMCV IRES was replaced with either the PV, HCV, or CrPV IRES using 5’ ApaI and 3’ NdeI restriction enzymes to generate the PV-RLuc, HCV-RLuc, and CrPV-RLuc plasmids, respectively. The four IRES-driven RLuc genes contain a 3’ poly(A)30 sequence from the pT7CFE1 vector, which resulted in the synthesis of mRNAs with uniform 3’ poly(A)30 tails.

All 6 mRNAs were synthesized by run-off in vitro transcription using T7 RNA polymerase at 37°C for 4–6 hours. The RLuc template DNA was prepared by linearizing the vector using XbaI, while the NanoLuc and IRES-driven template DNAs were prepared by PCR amplification. The transcription reactions were treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega) at 37°C for 30 minutes to remove the DNA templates. Each transcription reaction was cleaned up in two steps, first by chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation followed by Monarch RNA cleanup kit (NEB).

The RLuc and NanoLuc mRNAs were post-transcriptionally 5’ capped with 7-methylguanosine (m7G) using a homemade Vaccinia capping enzyme 49. The mRNAs were first heated for 5 minutes at 65°C and then put on ice for 5 minutes. Capping was carried out for 2 hours at 37°C in 50 μL reactions with 1X capping buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT), 0.5 mM GTP, 0.1 mM SAM, and 4 μL homemade Vaccinia capping enzyme; the amount of mRNA substrate to be modified was limited to maintain a large stoichiometric excess of both GTP and SAM to ensure all mRNA molecules were capped. The 5’ m7G-capped mRNAs were then cleaned up using the Monarch RNA cleanup kit.

In vitro translation assays

The rabbit reticulocyte lysate was prepared following the method described by (1) Feng and Shao, and (2) Sharma et al 50,51. In vitro translation (IVT) reactions in rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL) were carried out in a final 20 μL volume at 30°C for 90 minutes. First, in a 10 μL binding reaction, 24 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM potassium acetate, 20 nM mRNA, and 500–2000 nM protein were combined and incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature; the control sample contained the protein storage buffer equivalent to the highest volume of protein used in the titration (maximum 2 μL). Then 10 μL RRL was added to make the final 20 μL IVT reaction. After 90 minutes at 30°C, the samples were brought to room temperature for 5–10 minutes while 2 μL of 30 μM coelenterazine (Promega), or 15 μL of 1-to-50 diluted NanoLuc substrate (Promega), was pipetted into a 384-well white flat bottom plate (Greiner). In the case of IVT reactions containing RLuc mRNAs, 18 μL of the 20 μL sample was mixed with 2 μL coelenterazine, and luminescence readings were taken immediately on a Tecan Spark plate reader. In the case of IVT reactions containing NanoLuc mRNAs, 15 μL of the 20 μL sample was mixed with 15 μL of 1-to-50 diluted NanoLuc substrate, and luminescence readings were taken immediately on a Tecan Spark plate reader. Luminescence readings of samples in each titration were normalized to the signal of their respective control sample. GraphPad Prism was used to perform two-way ANOVA analysis to obtain P values.

For the GST-hFMRP RGG cleavage reactions with TEV protease, GST-hFMRP RGG fusion protein was combined with either TEV protease or storage buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4 and 1 mM DTT) at a 4:1 ratio for a final 20 μM GST-hFMRP RGG. The cleavage reactions were carried out for 2 hours and 30 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation, after which the protein samples were serially diluted in storage buffer for the IVT assay.

Preparation of Human 80S Ribosomes

Ribosomes were purified from 20 liters of HeLa-S3 cells (National Cell Culture Center) and all work was done at 4 ºC or on ice. The cell pellet was gently washed once with 20 ml PBS and resuspended in 20 ml of hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF). The cells were homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer by 10 strokes of pestle B and centrifuged at 3900 rpm for 15 minutes in a JA17 rotor at 4 ºC to pellet the nucleus. The supernatant (25 ml) was transferred to a 50 ml falcon tube and the following reagents were added: 250 μl of 1 M MgCl2, 830 μl of 3 M KCl, 250 μl of 50 mM PMSF, 50 μl of 50 mM benzamidine, 2.5 mg heparin, and 1 complete protease inhibitor tablet (Roche). The supernatant was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 30 min in a JA17 rotor at 4 ºC, transferred to new centrifuge tubes and the centrifugation was repeated once more. The supernatant was transferred to a new 50 ml falcon tube and kept on ice. 20 ml of 30% sucrose solution in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.1 mM benzamidine, and 1 mg/ml heparin) was prepared and it was cooled to 4 ºC. Transferred 10 ml of the 30% sucrose solution to two 25 ml ultracentrifuge bottles (Beckman cat# 355618) and 12 ml of the supernatant was carefully layered on top of each sucrose cushion. The sucrose cushions were centrifuged at 35,000 rpm for 20 hours in a Ti-70 rotor at 4 ºC. Discarded the supernatant and gently rinsed the crude ribosome pellets with 1 ml buffer A. Resuspended each ribosome pellet in 1 ml buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 500 mM KCl, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.1 mM benzamidine, and 1 mg/ml heparin) on ice. Transferred the crude ribosome solution to two microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 ºC. Transferred the supernatant to new microcentrifuge tubes. Prepared a 2.5 mg/ml puromycin solution in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5. Added 1 mg of puromycin per 100 mg of ribosomes. Incubated the ribosome-puromycin solution on ice for 30 minutes and then at 37 ºC for 30 minutes. The solution was clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 ºC. 500 μl of the puromycin-treated ribosomes was layered on top of a 10% - 40% sucrose gradient (prepared in buffer C: 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 25 mM KCl, and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and stored at 4 ºC for at least 2 hours). A total of six sucrose gradients were used and the gradients were centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 16 hours in a SW-28 rotor at 4 ºC. The gradients were fractionated using a syringe pump (Brandel) and an inline A254 nm detector with a chart recorder (UA-6, Isco). The 80S ribosome peak fractions from each gradient were pooled together, diluted 2-fold with buffer D (10 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) and transferred to 25 ml ultracentrifuge bottles. The sample was centrifuged at 35,000 rpm for 17 hours in a Ti-70 rotor at 4 ºC. The supernatant was discarded, and the ribosome pellets were rinsed in 1 ml buffer D. The ribosome pellets were resuspended in 1 ml buffer D, and 10 μl aliquots were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 ºC. The concentration of the ribosomes was calculated from 1 A260 unit is 20 picomoles/ml.

Human 80S ribosome binding assay

In 20 μL binding reactions, 0.8 μM human 80S ribosomes (equivalent to 80 μg ribosomes) and 7.2 μM protein were combined with 50 mM Tris acetate pH 7.7, additional potassium acetate (final 50 mM K+), additional magnesium acetate (final 3.8 mM Mg2+), 10 mM DTT, and 30 μg/mL total tRNA from E. coli. The 20 μL reactions were incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature, placed on ice for 2 minutes, and then carefully pipetted onto a pre-cooled 200 μL 40% (w/w) sucrose cushions reconstituted in RBB (50 mM Tris acetate pH 7.7, 50 mM potassium acetate, 5 mM magnesium acetate, and 10 mM DTT). For samples treated with RNase A, the 80 μg ribosomes in buffer were first incubated with 0.2 μg RNase A for 30 minutes at room temperature, as previously described 52, before adding total tRNA and incubating with protein. The samples were centrifuged at 4°C for 1 hour and 50 minutes at 182,753 × g (38,000 rpm in a Beckman Coulter Type 42.2 Ti rotor).

The supernatants were carefully removed then 16 μL RBB was gently pipetted onto the ribosome pellets and incubated covered at 4°C for 30 minutes. The 16 μL samples were carefully mixed once by gentle pipetting in place and transferred to clean tubes containing 4 μL 5X SDS sample loading solution. 10 μL of each 20 μL gel sample was analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue.

Results

FMRP inhibits the translation of various mRNAs

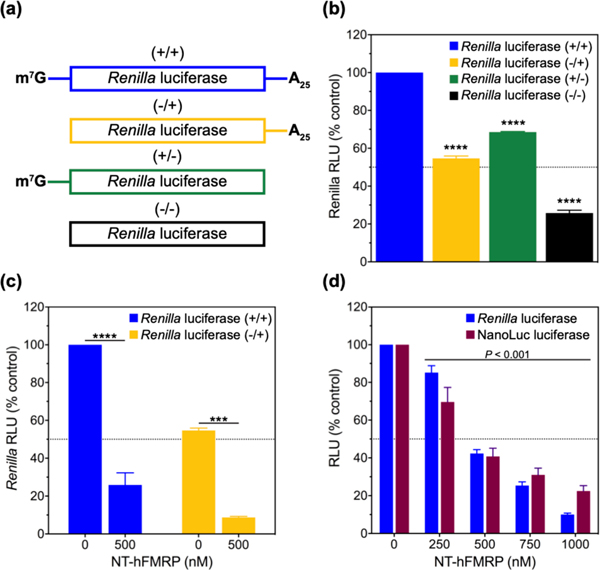

We sought to identify how the RNA-binding domains of human FMRP (hFMRP) contributed to the regulation of mRNA translation. We dissected hFMRP into two halves, the KH0-KH2 domains and the RGG domain with the C-terminal domain (CTD) (Figure 1, Figure S1). We used a nuclease-treated rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL) in vitro translation (IVT) system to test FMRP effects on the Renilla luciferase (RLuc) reporter mRNA translation. First, we measured the importance of two canonical post-transcriptional modifications, the 5’-m7G cap and 3’ polyA tail, in increasing translation efficiency in the RRL system (Figure 2). We observed that the individual modifications are not critical for efficient translation, but removing the 5’-m7G cap and 3’ polyA tail significantly decreases translation efficiency in RRL (Figure 2b). FMRP has been proposed to regulate the translation of some mRNAs during the initiation step through interactions involving the 5’ cap 39. Therefore, we tested how NT-hFMRP regulates the translation of a polyadenylated RLuc with and without the 5’ cap. We observed FMRP inhibits both mRNAs similarly, suggesting that the inhibition is independent of the 5’ cap machinery (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Human FMRP inhibits translation of different mRNAs in RRL. (a) Diagram of Renilla luciferase (RLuc) mRNAs containing: both 5’-m7G cap and 3’-polyA25 tail (+/+, blue), only 3’-polyA25 tail (−/+, yellow), only 5’-m7G cap (+/−, green), or neither 5’-m7G cap nor 3’-polyA25 tail (−/−, black). (b) Relative luminescence units (RLU) from 10 nM of the four aforementioned Renilla luciferase mRNAs all as a percentage of the (+/+) RLuc mRNA. (c) RLU from 10 nM RLuc mRNAs (+/+) in blue and (−/+) in yellow upon the addition of 500 nM NT-hFMRP, all as a percentage of the (+/+) RLuc mRNA. (d) RLU from 10 nM Renilla luciferase mRNA (blue) and 10 nM NanoLuc luciferase mRNA (maroon) upon the addition of 0–1000 nM NT-hFMRP in RRL as a percentage of the respective control mRNA sample containing no NT-hFMRP. The standard deviations from three experiments are shown. P < 0.0001 is denoted with four asterisks (*) and P < 0.001 is denoted with three asterisks (*).

However, it was unclear whether FMRP specifically inhibits translation of RLuc mRNA because it contains a feature that makes it a target mRNA, or if FMRP would have a similar effect on the translation of different mRNAs. Therefore, we compared the effect of NT-hFMRP on the translation of Renilla luciferase (RLuc) and NanoLuc luciferase (NLuc) reporter mRNAs. Surprisingly, we observed nearly identical effects on both mRNAs, suggesting FMRP inhibits translation through a common mechanism (Figure 2d).

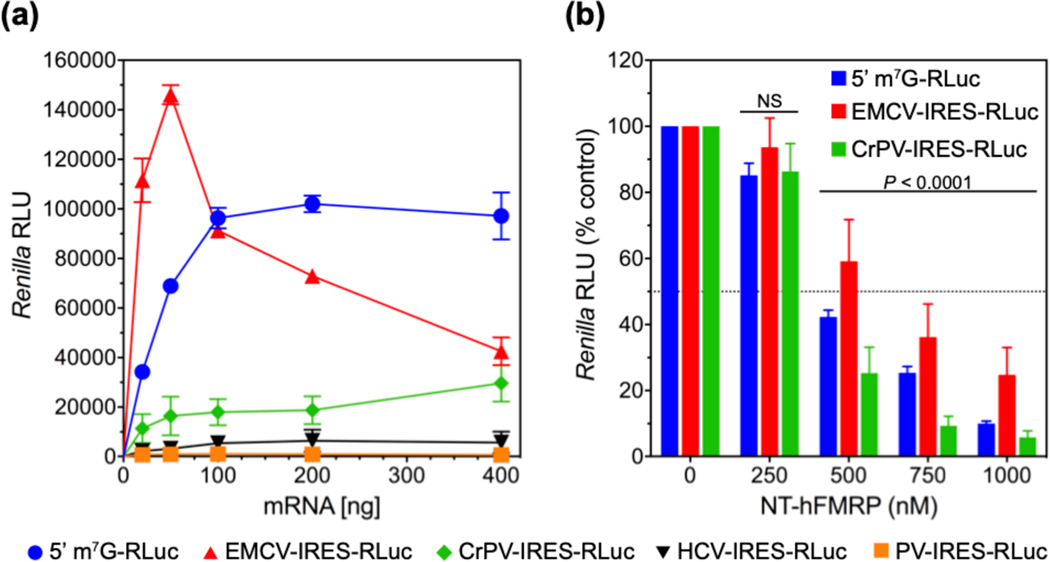

FMRP inhibits the elongation step of translation

We observed that hFMRP equally inhibited the translation of 5’-capped and uncapped RLuc mRNAs (Figure 2c). Therefore, we sought to test hFMRP inhibition of canonical capped-and-tailed RLuc mRNA against internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-driven mRNAs. We generated RLuc mRNAs driven by a representative IRES from the four different classes of IRESes: poliovirus (PV-RLuc), encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV-RLuc), hepatitis C virus (HCV-RLuc), and cricket paralysis virus (CrPV-RLuc) 53. Unfortunately, the PV-RLuc and HCV-RLuc mRNAs did not translate efficiently enough for IVT studies, so we proceeded with the EMCV-RLuc and CrPV-RLuc mRNAs at a fixed 10 nanomolar concentration for comparison against 10 nanomolar canonical RLuc (Figure 3a). While one may expect more protein synthesis from having more mRNAs in the IVT reaction, too much of the EMCV IRES-driven RLuc mRNA actually decreases translation efficiency 54. Consistent with our previous observation, we observed FMRP inhibit the translation of CrPV-RLuc as efficiently as the canonical RLuc, suggesting that FMRP indeed inhibits translation of RLuc exclusively at the elongation step because CrPV IRES mRNA does not require any of the initiation factors to bind to the ribosome and initiate protein synthesis 55–58. Inhibition of EMCV-RLuc was slightly milder compared to canonical RLuc and CrPV-RLuc (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

FMRP inhibits translation of canonical and IRES-driven Renilla luciferase mRNAs. (a) Relative luminescence units (RLU) from Renilla luciferase upon the addition of 0–400 ng of the indicated mRNAs in RRL. (b) RLU from canonical Renilla luciferase mRNA (blue), EMCV IRES-driven Renilla luciferase mRNA (red), and CrPV IRES-driven Renilla luciferase mRNA (green) upon the addition of 0–1000 nM NT-hFMRP in RRL as a percentage of the respective control mRNA sample containing no NT-hFMRP. The standard deviations from three experiments are shown. P value with no significant difference is denoted with NS.

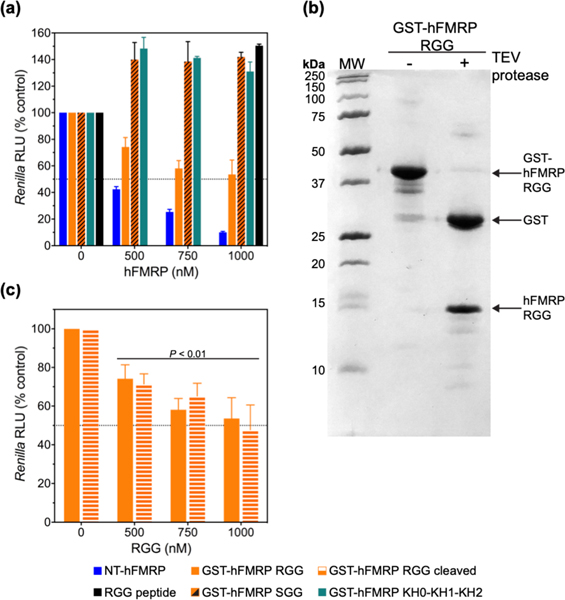

The RGG domain and CTD are sufficient to inhibit translation

To identify which regions and RNA-binding domains of hFMRP contribute to translation inhibition, we measured the effects of the GST-tagged KH0-KH1-KH2 region (GST-KH0-KH1-KH2), GST-tagged RGG-CTD region (GST-hFMRP RGG), and a GST-tagged mutant SGG-CTD region (GST-hFMRP SGG) on RLuc mRNA translation. We In contrast, GST-KH0-KH1-KH2 did not inhibit translation and had a similar effect as the mutant GST-hFMRP SGG in which the RNA G-quadruplex (GQ)-binding arginines spanning the RGG domain and CTD of FMRP were all mutated to serines (Figure 4a). Furthermore, we tested whether the RNA GQ-binding RGG domain was sufficient to inhibit translation. We used the 18 amino acid RGG peptide previously found to bind the sc1 GQ-forming RNA and observed it was insufficient to inhibit translation, suggesting the CTD of hFMRP plays an essential role in translation inhibition (Figure 4a) 23,59. Finally, the GST-hFMRP RGG is not as efficient at inhibiting RLuc translation compared to NT-hFMRP. This suggests there may indeed be a cooperative effect between the C-terminus of hFMRP, containing the RGG and CTD, the KH1 and KH2 domains, and the unstructured region between the KH2 and RGG domains. Altogether, it is possible the RGG and CTD are critical for the initial binding interaction as an anchor while the other regions of FMRP further stabilize that interaction.

Figure 4.

The RGG domain and CTD of FMRP are required for inhibition of translation. (a) Relative luminescence units (RLU) from Renilla luciferase upon the addition of 0–1000 nM NT-hFMRP (blue), GST-hFMRP RGG (orange), GST-hFMRP SGG (orange with black diagonal stripes), GST-hFMRP KH0-KH1-KH2 domains (teal), and RGG peptide (black) in RRL as a percentage of the respective control mRNA sample containing no hFMRP. (b) 12% SDS-PAGE of GST-hFMRP RGG before (- TEV protease) and after (+ TEV protease) cleaving with TEV protease. (c) RLU from Renilla luciferase upon the addition of 0–1000 nM GST-hFMRP RGG (orange) and GST-hFMRP RGG pre-cleaved using TEV protease (orange with white horizontal stripes) in RRL as a percentage of the respective control mRNA sample containing no GST-hFMRP RGG. The standard deviations from three experiments are shown.

To determine if the GST tag is involved in translation inhibition by the RGG-CTD region, we cleaved the GST-hFMRP RGG with TEV protease to separate the GST tag and RGG-CTD fragments before IVT (Figure 4b). We observed no significant difference in translation inhibition between the intact GST-hFMRP RGG fusion protein and the cleaved protein, showing that the GST protein is not involved in translation inhibition by the RGG-CTD fragment (Figure 4c).

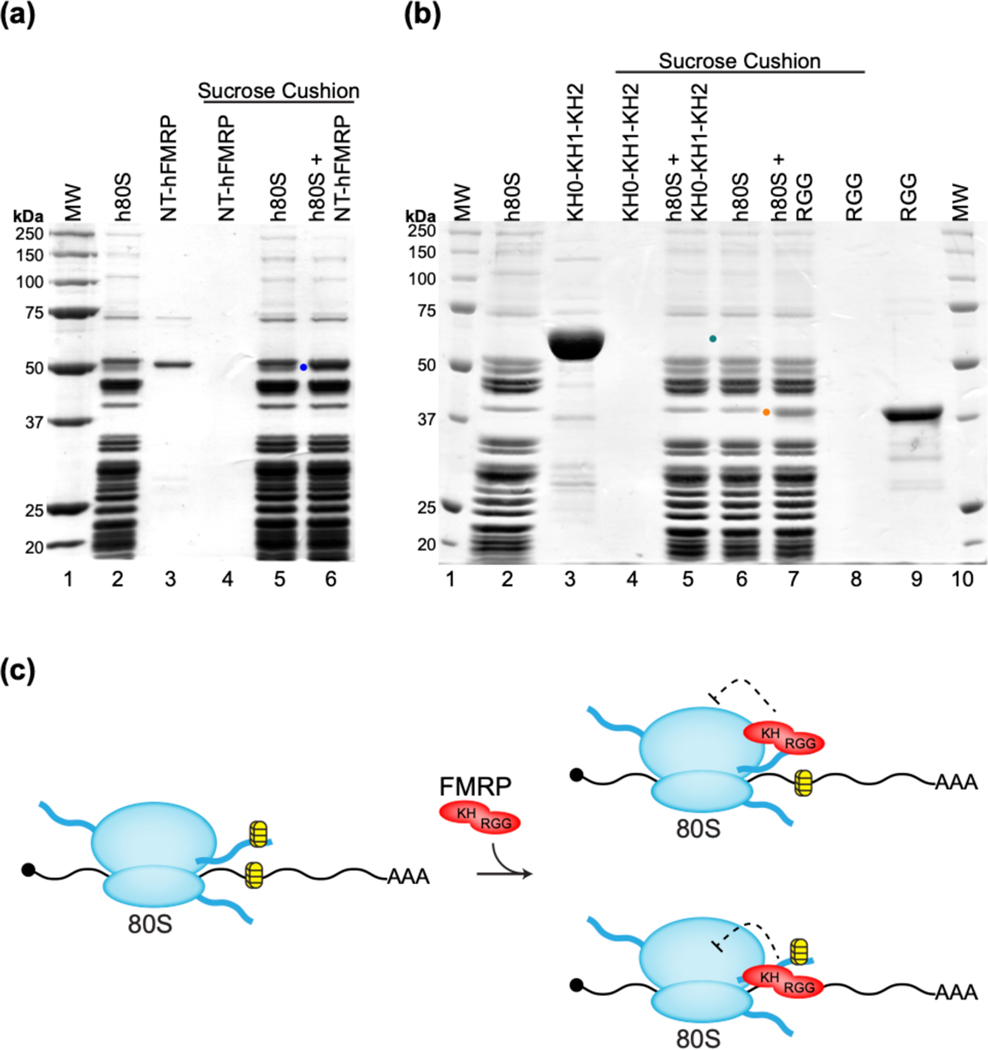

FMRP binding to the ribosome correlates with inhibition of translation

Based on past findings and our observations that FMRP inhibits translation at the elongation step and the RGG-CTD region is sufficient for inhibition, we hypothesized the RGG-CTD might be serving as the anchor during direct binding of FMRP to the ribosome. Two recent studies found specific rRNA expansion segments in the ribosomes of higher eukaryotes contain G-quadruplex structures 37,38. Together with our recent study showing the RGG domain of hFMRP can bind even a minimal G-quadruplex structure, we investigated whether the RGG-CTD region of hFMRP could be binding directly to a rRNA G-quadruplex on the ribosome to inhibit translation 24. To determine whether binding to the ribosome is correlated with translation inhibition, we tested the binding of the human 80S ribosome to NT-hFMRP, GST-hFMRP RGG, and GST-hFMRP KH0-KH1-KH2 by sucrose cushion co-sedimentation. We observed both NT-hFMRP and GST-hFMRP RGG bind directly to the ribosome, while GST-hFMRP KH0-KH1-KH2 does not bind (Figure 5). Our results suggest that the direct binding of FMRP to the ribosome is crucial for inhibition of translation. To test whether the RGG-CTD region binds to the ribosome via a rRNA or protein, we also tested the binding of GST-hFMRP RGG to human 80S ribosome pre-treated with RNase A. Treatment of the ribosome with RNAse A abolished the binding of hFMRP RGG-CTD to the human 80S ribosome suggesting that the interaction is indeed mediated by rRNA (Figure S2).

Figure 5.

NT-hFMRP and GST-hFMRP RGG bind directly to the human 80S ribosome. (a) A representative 10% SDS-PAGE of 40% sucrose co-sedimentation assay showing NT-hFMRP (blue dot) co-sediments with human 80S ribosomes (h80S). Samples in lanes 4 to 6 were sedimented through the sucrose cushion. Lanes: 1, molecular weight ladder; 2, input h80S; 3, input NT-hFMRP; 4, NT-hFMRP in pellet; 5, h80S in pellet; 6, h80S+NT-hFMRP complex in pellet. NT-hFMRP migrated close to a ribosomal protein; however, quantification showed that the band intensity of the NT-hFMRP and the ribosomal protein in lane 6 increased by ~30% compared to the same ribosomal protein band in lane 5. (b) A representative 10% SDS-PAGE of 40% sucrose co-sedimentation assay showing GST-hFMRP RGG (orange dot) co-sediments with human 80S ribosomes, but GST-hFMRP KH0-KH1-KH2 (teal dot) does not. Samples in lanes 4 to 8 were sedimented through the sucrose cushion. Lanes: 1, molecular weight ladder; 2, input h80S; 3, input KH0-KH1-KH2; 4, KH0-KH1-KH2 in pellet; 5, h80S+KH0-KH1-KH2 in pellet; 6, h80S in pellet; 7, h80S+GST-hFMRP RGG in pellet; 8, GST-hFMRP RGG in pellet; 9, input GST-hFMRP RGG; 10, molecular weight ladder. GST-hFMRP RGG migrated close to a ribosomal protein; however, quantification showed that the band intensity of the GST-hFMRP RGG and the ribosomal protein in lane 7 increased by ~40% compared to the same ribosomal protein band in lane 6. (c) Model for the inhibition of translation by FMRP. RNA GQ structures are present in both the rRNAs and in the mRNA (yellow and black structures). Top: The RGG-CTD tail of FMRP binds to a GQ structure in an rRNA expansion segment and the KH domains interact with a functional site on the ribosome to inhibit translation. Bottom: The RGG-CTD tail of FMRP binds to a GQ structure in the mRNA and the KH domains interact with a functional site on the ribosome to inhibit translation. Labels: FMRP (red), 80S ribosome (blue), rRNA expansion segments (wavy dark blue lines), GQ structures (yellow and black), and mRNA (black).

Discussion

FMRP has been proposed to regulate the translation of thousands of mRNA targets suggesting that it either has relaxed RNA-binding specificity or the RNA recognition element is present abundantly in mRNAs 12,13,16–19. Alternatively, FMRP may globally inhibit translation by repressing the function of a specific translation factor or the ribosome. Our IVT studies in RRL lead us to conclude that human FMRP inhibits mRNAs indiscriminately and to similar degrees when concentrations of two different mRNAs of different lengths are standardized. This suggests FMRP does not necessarily regulate the translation of only a subset of target mRNAs, but can also regulate mRNAs globally through a common upstream translation mechanism independent of sequence or structure features in the mRNA.

FMRP also potently inhibits the translation of RLuc mRNA independent of the 5’ cap, showing that potent inhibition can occur without FMRP interacting with the initiation machinery. To confirm our findings, we used CrPV IRES, which binds directly to the ribosomal P site to initiate translation without the need for any initiation factors 55–58. FMRP inhibits CrPV-RLuc just as potently as the canonical RLuc, supporting the hypothesis that FMRP inhibits at the elongation step regardless of the initiation rate and initiation machinery. We observe milder inhibition of EMCV-RLuc by FMRP, which may suggest FMRP’s ability to inhibit translation is linked to factors beyond translation elongation. A recent study looked into the differences between canonical and EMCV-driven translation and found EMCV IRESes are indistinguishable from canonical 5’ UTRs in terms of initiation and elongation rates. However, the EMCV IRES is less efficient at recruiting ribosomes than the 5’ cap machinery 60. Ribosome recruitment and availability, together with elongation, seem to be major factors for FMRP inhibition of translation.

Upon dissecting FMRP, we determined the arginine-rich RGG domain and CTD are the primary drivers of translation inhibition, while the region spanning the putative RNA-binding KH0 to KH2 domains alone cannot inhibit translation. Although the RGG-CTD region may be sufficient for mild translation inhibition, potent inhibition requires additional features found in NT-hFMRP, such as the unstructured region between the KH2 and RGG domains. Based on our ribosome-binding study, it is possible that the KH domains cannot inhibit translation alone because they cannot form a stable interaction with the ribosome. Perhaps the KH domains cooperate with the RGG-CTD to stabilize the initial interaction between the RGG-CTD and the ribosome to enhance translation inhibition.

Overall our studies suggest hFMRP can globally inhibit mRNA translation by binding directly to ribosomes through its RGG domain and CTD tail to (1) effectively decrease the population of active ribosomes available to translate mRNAs, and (2) stall actively translating ribosomes at the elongation step (Figure 5c). The G-quadruplex structures present in the rRNA expansion segments may anchor hFMRP on the ribosome during translational inhibition 37,38. It remains to be seen whether RREs, such as G-quadruplexes, within the mRNAs can alter translation regulation by FMRP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01GM114261 to S.J.]. Funding for open access charge: National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

ACCESSION CODES

UniProtKB: Q06787

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information Available: [Figures S1 and S2] This material is available free of charge via the Internet at https://urldefense.com/v3/__http://pubs.acs.org__;!!Mih3wA!UFGH2HG2Lq80kn1oH_WcAgItt0sgPHbQ66Fl0Sadtge0T4JK450-goqfSf1BxRo$

References

- (1).Santoro MR, Bray SM, and Warren ST (2012) Molecular Mechanisms of Fragile X Syndrome: A Twenty-Year Perspective. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 7, 219–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Coffee B, Zhang F, Warren ST, and Reines D. (1999) Acetylated histones are associated with FMR1 in normal but not fragile X-syndrome cells. Nat Genet 22, 98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Nelson DL, Orr HT, and Warren ST (2013) The unstable repeats--three evolving faces of neurological disease. Neuron 77, 825–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Sutcliffe JS, Nelson DL, Zhang F, Pieretti M, Caskey CT, Saxe D, and Warren ST (1992) DNA methylation represses FMR-1 transcription in fragile X syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 1, 397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Verkerk AJMH, Pieretti M, Sutcliffe JS, Fu Y-H, Kuhl DPA, Pizzuti A, Reiner O, Richards S, Victoria MF, Zhang F, Eussen BE, van Ommen G-JB, Blonden LAJ, Riggins GJ, Chastain JL, Kunst CB, Galjaard H, Thomas Caskey C, Nelson DL, Oostra BA, and Warren ST (1991) Identification of a gene (FMR-1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster region exhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell 65, 905–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Siomi H, Siomi MC, Nussbaum RL, and Dreyfuss G. (1993) The protein product of the fragile X gene, FMR1, has characteristics of an RNA-binding protein. Cell 74, 291–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ashley CT, Wilkinson KD, Reines D, and Warren ST (1993) FMR1 protein: conserved RNP family domains and selective RNA binding. Science 262, 563–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Devys D, Lutz Y, Rouyer N, Bellocq JP, and Mandel JL (1993) The FMR-1 protein is cytoplasmic, most abundant in neurons and appears normal in carriers of a fragile X premutation. Nat Genet 4, 335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Siomi H, Choi M, Siomi MC, Nussbaum RL, and Dreyfuss G. (1994) Essential role for KH domains in RNA binding: impaired RNA binding by a mutation in the KH domain of FMR1 that causes fragile X syndrome. Cell 77, 33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hinds HL, Ashley CT, Sutcliffe JS, Nelson DL, Warren ST, Housman DE, and Schalling M. (1993) Tissue specific expression of FMR-1 provides evidence for a functional role in fragile X syndrome. Nat Genet 3, 36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Myrick LK, Hashimoto H, Cheng X, and Warren ST (2015) Human FMRP contains an integral tandem Agenet (Tudor) and KH motif in the amino terminal domain. Hum Mol Genet 24, 1733–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Brown V, Jin P, Ceman S, Darnell JC, O’Donnell WT, Tenenbaum SA, Jin X, Feng Y, Wilkinson KD, Keene JD, Darnell RB, and Warren ST (2001) Microarray Identification of FMRP-Associated Brain mRNAs and Altered mRNA Translational Profiles in Fragile X Syndrome. Cell 107, 477–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Darnell JC, Van Driesche SJ, Zhang C, Hung KYS, Mele A, Fraser CE, Stone EF, Chen C, Fak JJ, Chi SW, Licatalosi DD, Richter JD, and Darnell RB (2011) FMRP Stalls Ribosomal Translocation on mRNAs Linked to Synaptic Function and Autism. Cell 146, 247–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Myrick LK, Nakamoto-Kinoshita M, Lindor NM, Kirmani S, Cheng X, and Warren ST (2014) Fragile X syndrome due to a missense mutation. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. EJHG 22, 1185–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).De Boulle K, Verkerk AJ, Reyniers E, Vits L, Hendrickx J, Van Roy B, Van den Bos F, de Graaff E, Oostra BA, and Willems PJ (1993) A point mutation in the FMR-1 gene associated with fragile X mental retardation. Nat Genet 3, 31–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ascano M, Mukherjee N, Bandaru P, Miller JB, Nusbaum JD, Corcoran DL, Langlois C, Munschauer M, Dewell S, Hafner M, Williams Z, Ohler U, and Tuschl T. (2012) FMRP targets distinct mRNA sequence elements to regulate protein expression. Nature 492, 382–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).McMahon AC, Rahman R, Jin H, Shen JL, Fieldsend A, Luo W, and Rosbash M. (2016) TRIBE: Hijacking an RNA-Editing Enzyme to Identify Cell-Specific Targets of RNA-Binding Proteins. Cell 165, 742–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ray D, Kazan H, Cook KB, Weirauch MT, Najafabadi HS, Li X, Gueroussov S, Albu M, Zheng H, Yang A, Na H, Irimia M, Matzat LH, Dale RK, Smith SA, Yarosh CA, Kelly SM, Nabet B, Mecenas D, Li W, Laishram RS, Qiao M, Lipshitz HD, Piano F, Corbett AH, Carstens RP, Frey BJ, Anderson RA, Lynch KW, Penalva LOF, Lei EP, Fraser AG, Blencowe BJ, Morris QD, and Hughes TR (2013) A compendium of RNA-binding motifs for decoding gene regulation. Nature 499, 172–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Suhl JA, Chopra P, Anderson BR, Bassell GJ, and Warren ST (2014) Analysis of FMRP mRNA target datasets reveals highly associated mRNAs mediated by G-quadruplex structures formed via clustered WGGA sequences. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 5479–5491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Darnell JC, Jensen KB, Jin P, Brown V, Warren ST, and Darnell RB (2001) Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein Targets G Quartet mRNAs Important for Neuronal Function. Cell 107, 489–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Schaeffer C, Bardoni B, Mandel JL, Ehresmann B, Ehresmann C, and Moine H. (2001) The fragile X mental retardation protein binds specifically to its mRNA via a purine quartet motif. EMBO J 20, 4803–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Darnell JC, Fraser CE, Mostovetsky O, Stefani G, Jones TA, Eddy SR, and Darnell RB (2005) Kissing complex RNAs mediate interaction between the Fragile-X mental retardation protein KH2 domain and brain polyribosomes. Genes Dev 19, 903–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Phan AT, Kuryavyi V, Darnell JC, Serganov A, Majumdar A, Ilin S, Raslin T, Polonskaia A, Chen C, Clain D, Darnell RB, and Patel DJ (2011) Structure-function studies of FMRP RGG peptide recognition of an RNA duplexquadruplex junction. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 796–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Athar YM, and Joseph S. (2020) RNA-Binding Specificity of the Human Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein. J. Mol. Biol. 432, 3851–3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Hollingworth D, Candel AM, Nicastro G, Martin SR, Briata P, Gherzi R, and Ramos A. (2012) KH domains with impaired nucleic acid binding as a tool for functional analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 40, 6873–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Nicastro G, Taylor IA, and Ramos A. (2015) KH–RNA interactions: back in the groove. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 30, 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Jensen KB, Musunuru K, Lewis HA, Burley SK, and Darnell RB (2000) The tetranucleotide UCAY directs the specific recognition of RNA by the Nova K-homology 3 domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 5740–5745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Lewis HA, Musunuru K, Jensen KB, Edo C, Chen H, Darnell RB, and Burley SK (2000) Sequence-specific RNA binding by a Nova KH domain: implications for paraneoplastic disease and the fragile X syndrome. Cell 100, 323–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Nicastro G, Candel AM, Uhl M, Oregioni A, Hollingworth D, Backofen R, Martin SR, and Ramos A. (2017) Mechanism of β-actin mRNA Recognition by ZBP1. Cell Rep. 18, 1187–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Blice-Baum AC, and Mihailescu MR (2014) Biophysical characterization of G-quadruplex forming FMR1 mRNA and of its interactions with different fragile X mental retardation protein isoforms. RNA 20, 103–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Menon L, and Mihailescu MR (2007) Interactions of the G quartet forming semaphorin 3F RNA with the RGG box domain of the fragile X protein family. Nucleic Acids Res 35, 5379–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Menon L, Mader SA, and Mihailescu MR (2008) Fragile X mental retardation protein interactions with the microtubule associated protein 1B RNA. RNA 14, 1644–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Stefanovic S, DeMarco BA, Underwood A, Williams KR, Bassell GJ, and Mihailescu MR (2015) Fragile X mental retardation protein interactions with a G quadruplex structure in the 3′-untranslated region of NR2B mRNA. Mol. Biosyst. 11, 3222–3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Zhang Y, Gaetano CM, Williams KR, Bassell GJ, and Mihailescu MR (2014) FMRP interacts with G-quadruplex structures in the 3’-UTR of its dendritic target Shank1 mRNA. RNA Biol. 11, 1364–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Zanotti KJ, Lackey PE, Evans GL, and Mihailescu MR (2006) Thermodynamics of the fragile X mental retardation protein RGG box interactions with G quartet forming RNA. Biochemistry 45, 8319–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Ozdilek BA, Thompson VF, Ahmed NS, White CI, Batey RT, and Schwartz JC (2017) Intrinsically disordered RGG/RG domains mediate degenerate specificity in RNA binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 7984–7996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Mestre-Fos S, Penev PI, Suttapitugsakul S, Hu M, Ito C, Petrov AS, Wartell RM, Wu R, and Williams LD (2019) G-Quadruplexes in Human Ribosomal RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 1940–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Mestre-Fos S, Penev PI, Richards JC, Dean WL, Gray RD, Chaires JB, and Williams LD (2019) Profusion of G-quadruplexes on both subunits of metazoan ribosomes. PloS One 14, e0226177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Napoli I, Mercaldo V, Boyl PP, Eleuteri B, Zalfa F, De Rubeis S, Di Marino D, Mohr E, Massimi M, Falconi M, Witke W, Costa-Mattioli M, Sonenberg N, Achsel T, and Bagni C. (2008) The Fragile X Syndrome Protein Represses Activity-Dependent Translation through CYFIP1, a New 4E-BP. Cell 134, 1042–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Stefani G. (2004) Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein Is Associated with Translating Polyribosomes in Neuronal Cells. J. Neurosci. 24, 7272–7276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Ceman S, O’Donnell WT, Reed M, Patton S, Pohl J, and Warren ST (2003) Phosphorylation influences the translation state of FMRP-associated polyribosomes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 3295–3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Chen E, Sharma MR, Shi X, Agrawal RK, and Joseph S. (2014) Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein Regulates Translation by Binding Directly to the Ribosome. Mol. Cell 54, 407–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Agrawal RK, Spahn CM, Penczek P, Grassucci RA, Nierhaus KH, and Frank J. (2000) Visualization of tRNA movements on the Escherichia coli 70S ribosome during the elongation cycle. J Cell Biol 150, 447–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Caudy AA, Myers M, Hannon GJ, and Hammond SM (2002) Fragile X-related protein and VIG associate with the RNA interference machinery. Genes Dev 16, 2491–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Ishizuka A, Siomi MC, and Siomi H. (2002) A Drosophila fragile X protein interacts with components of RNAi and ribosomal proteins. Genes Dev 16, 2497–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Plante I, Davidovic L, Ouellet DL, Gobeil LA, Tremblay S, Khandjian EW, and Provost P. (2006) Dicer-derived microRNAs are utilized by the fragile X mental retardation protein for assembly on target RNAs. J Biomed Biotechnol 2006, 64347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Edbauer D, Neilson JR, Foster KA, Wang CF, Seeburg DP, Batterton MN, Tada T, Dolan BM, Sharp PA, and Sheng M. (2010) Regulation of synaptic structure and function by FMRP-associated microRNAs miR-125b and miR-132. Neuron 65, 373–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Muddashetty RS, Nalavadi VC, Gross C, Yao X, Xing L, Laur O, Warren ST, and Bassell GJ (2011) Reversible inhibition of PSD-95 mRNA translation by miR-125a, FMRP phosphorylation, and mGluR signaling. Mol Cell 42, 673–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Fuchs A-L, Neu A, and Sprangers R. (2016) A general method for rapid and cost-efficient large-scale production of 5′ capped RNA. RNA 22, 1454–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Feng Q, and Shao S. (2018) In vitro reconstitution of translational arrest pathways. Methods San Diego Calif 137, 20–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Sharma A, Mariappan M, Appathurai S, and Hegde RS (2010) In vitro dissection of protein translocation into the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 619, 339–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Simsek D, Tiu GC, Flynn RA, Byeon GW, Leppek K, Xu AF, Chang HY, and Barna M. (2017) The Mammalian Ribo-interactome Reveals Ribosome Functional Diversity and Heterogeneity. Cell 169, 1051–1065.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Mailliot J, and Martin F. (2018) Viral internal ribosomal entry sites: four classes for one goal. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Zeenko VV, Wang C, Majumder M, Komar AA, Snider MD, Merrick WC, Kaufman RJ, and Hatzoglou M. (2008) An efficient in vitro translation system from mammalian cells lacking the translational inhibition caused by eIF2 phosphorylation. RNA 14, 593–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Jan E, and Sarnow P. (2002) Factorless ribosome assembly on the internal ribosome entry site of cricket paralysis virus. J Mol Biol 324, 889–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Pestova TV, Lomakin IB, and Hellen CU (2004) Position of the CrPV IRES on the 40S subunit and factor dependence of IRES/80S ribosome assembly. EMBO Rep 5, 906–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Spahn CM, Jan E, Mulder A, Grassucci RA, Sarnow P, and Frank J. (2004) Cryo-EM visualization of a viral internal ribosome entry site bound to human ribosomes: the IRES functions as an RNA-based translation factor. Cell 118, 465–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Pestova TV, and Hellen CU (2005) Reconstitution of eukaryotic translation elongation in vitro following initiation by internal ribosomal entry. Methods 36, 261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Vasilyev N, Polonskaia A, Darnell JC, Darnell RB, Patel DJ, and Serganov A. (2015) Crystal structure reveals specific recognition of a G-quadruplex RNA by a β-turn in the RGG motif of FMRP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, E5391–E5400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Koch A, Aguilera L, Morisaki T, Munsky B, and Stasevich TJ (2020) Quantifying the spatiotemporal dynamics of IRES versus Cap translation with single-molecule resolution in living cells. bioRxiv 2020.01.09.900829. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.